About the Parkway

by Anne Mitchell Whisnant

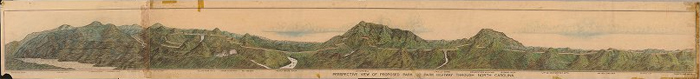

Scenic View of Mountains and Parkway, Asheville, 1946

Courtesy National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway

The Blue Ridge Parkway is a 469-mile scenic road winding through twenty-nine counties in the beautiful southern Appalachian mountains of Virginia and North Carolina. A carefully designed landscape set within a narrow corridor of protected land (about 88,000 acres in all), it is – as its name suggests – a “way through a park.” Unlike many other national parks whose boundaries surround the entire landscapes they are designed to protect and present, the Parkway is a narrow ribbon that “borrows” many of its signature scenic views from the nearby countryside.

The Parkway is owned and managed for the American public by the National Park Service as part of the national park system. It is a key part of a larger southern Appalachian park complex. With its northern terminus joining Shenandoah National Park’s Skyline Drive near Waynesboro, Virginia, the Parkway snakes southward to the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, on the North Carolina-Tennessee border. Both Shenandoah and the Great Smokies were authorized in the 1920s and opened in the 1930s as part of an effort to bring national parks nearer to population centers of the eastern United States. Work began in 1935 to connect the new Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks, and the Parkway was finally finished in 1987 with the completion of the final section, the “missing link” around Grandfather Mountain, North Carolina.

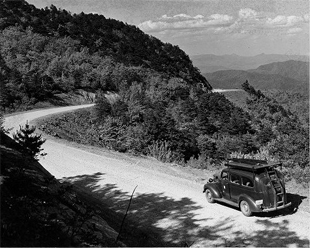

Since 1946, the Blue Ridge Parkway has been the most visited site in the entire national park system. In recent years, more than eighteen million visitors have traveled parts of the Parkway every year. They drive to places where they can pull off the road to see a distant view, enjoy spring wildflowers or colorful fall leaves, get out for a short hike, listen to music in several established venues, or set up a tent at a campground.

The Parkway was a product of the Great Depression of the 1930s and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal programs to stimulate the economy and put people to work. Initially funded under the federal Public Works Administration and later drawing monies and labor from other New Deal agencies, including the Resettlement Administration, the Works Progress Administration, and the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Parkway was one of the New Deal’s signature park development projects.

Old buildings in Section 2Q to be destroyed for Parkway construction, 1939

National Park Service, Blue Ridge Parkway

By the time construction halted in 1943 for the duration of World War II, work was under way on about 330 miles of the road. Only about 170 miles, however, were by then paved and fully open to travel. A large portion of the funding for the road’s completion came from another large federal park-enhancement program, MISSION 66, which poured $1 billion into the national parks from 1956 to 1966. When this program ended, all but the 7.5-mile Grandfather Mountain section was complete.

Building the Parkway was a cooperative effort of many hands, agencies, and individuals at the federal, state, and local levels. The states of North Carolina and Virginia acquired most of the land and deeded it to the federal government, while other lands were turned over to the Park Service by the U.S. Forest Service. Parkway engineers and designers, especially North Carolina State Highway Commission location engineer R. Getty Browning, National Park Service landscape architect Stanley W. Abbott and his design team, and engineers from the federal Bureau of Public Roads, laid out a route and crafted a carefully planned landscape that highlighted glorious mountain vistas, invited travelers to discover secluded coves and dramatic waterfalls, and opened “great picture windows” into an idealized rural pioneer America. Private road-building contractors did heavy construction, and men in four Civilian Conservation Corps and Civilian Public Service camps shaped and groomed the landscape and built visitor facilities.

Crafting a scenic parkway required that the road be built according to rules different from those that governed regular highways in the 1930s. To preserve the scenic experience, the Parkway was planned to be a non-commercial, limited-access road, bounded by an exceptionally wide right-of-way (eight hundred to one thousand feet). Although these rules produced a beautiful parkway for travelers, they sparked significant conflict with some landowners through whose lands the road was threaded. This conflict arose because -- unlike western parks carved from the public lands -- the Parkway was built through a long-populated area that included small farms, two major cities (Roanoke and Asheville), and numerous smaller towns. In many places, industrial scale timbering had previously ravaged the land, while in other locations tourism thrived.

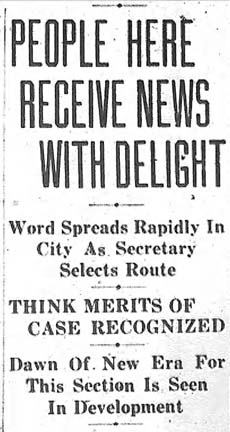

People Here Receive News With Delight (detail), Asheville, NC, 1934

North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Handling the bulk of land acquisition through the 1960s, Virginia and North Carolina used their power of eminent domain to buy more than 40,000 acres from thousands of owners for the Parkway. Some of it was land that farm families had long lived on and loved. Most of them had no choice about whether to sell. Sometimes they weren’t paid much, and sometimes they did not see how a restricted scenic Parkway would benefit them. Some resented how it disrupted their lives, and wondered why some other owners got paid more for their lands.

Others eagerly awaited the Parkway’s promised benefits. Many of the project’s most vigorous supporters were leaders in the North Carolina tourism-oriented business community, especially in Asheville. A booming tourist center from the late nineteenth century into the 1920s, Asheville had by the early 1930s fallen on hard times. The tourists were gone and the city nearly bankrupt after an ill-considered 1920s spending spree and the collapse of a major local bank. Asheville’s civic leaders saw the Parkway–which would link the city to the new Great Smoky Mountains National Park–as the city’s great hope for reviving tourism through a federal public works program.

Creating and maintaining a scenic parkway in this environment has sparked a series of conflicts with landowners and business and civic interests who have craved influence over the project or sought to mitigate (or enhance) its effects on their own properties. As each conflict has been resolved, its resolution has been written onto the land.

Like any other large public works project, the Blue Ridge Parkway generated complicated questions concerning how, and whether, a “public good” can be identified and implemented fairly. Its history of conflict and strife presaged the challenges it continues to face: severe funding and staffing shortages, environmental threats, changing park usage, encroaching development, and the perennial necessity of negotiating the roadway’s relationships with its region.

At the same time, the Parkway is a living and developing record of the power of public vision, public will, and public resources to create and sustain magnificent public works for the common good. The history of this scenic road teaches important lessons about the politics of park management, conservation, and tourism, and the stories embedded in all of our built environments. If the history of conflict is written permanently upon the Parkway at some points, at other points one sees the results of dreaming nobly, operating beyond the limits of self-interest, and bequeathing the best of ourselves and our ideas to generations yet to come.