Africa and the American Negro: Addresses and Proceedings of the Congress on Africa:

Held under the Auspices of the Stewart Missionary Foundation for Africa

of Gammon Theological Seminary in Connection with the

Cotton States and International Exposition December 13-15, 1895.

Electronic Edition.

Bowen, J. W. E. (John Wesley Edward), 1855-1933, Ed.

Funding from the Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library Competition supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Meredith Evans

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Elizabeth S. Wright and Jill Kuhn Sexton

First edition, 2001

ca. 750K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) Africa and the American Negro...Addresses and Proceedings of the Congress on Africa Held Under the Auspices of the Stewart Missionary Foundation for Africa of Gammon Theological Seminary in Connection with the Cotton States and International Exposition December 13-15, 1895.

Edited by Prof. J. W. E. Bowen, Ph.D., D.D., Secretary of the Congress.

242 p., ill.

Atlanta

Gammon Theological Seminary

1896

Call Number: 916.03 c749a (Methodist Center, Drew University, Madison, NJ)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original. The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Footnotes have been inserted at the place of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- Zulu

- Undetermined

- French

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- Africa.

- African American Methodists -- Missions -- Africa.

- African Americans -- Congresses.

- Blacks -- Missions -- Africa.

- Methodist Church -- Missions -- Africa.

- Methodist Episcopal Church -- Missions -- Africa.

- Missions -- Africa.

- Missions -- Congresses.

Revision History:

- 2001-06-28,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-04-23,

Jill Kuhn Sexton, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-03-15,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-01-01,

Apex Data services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

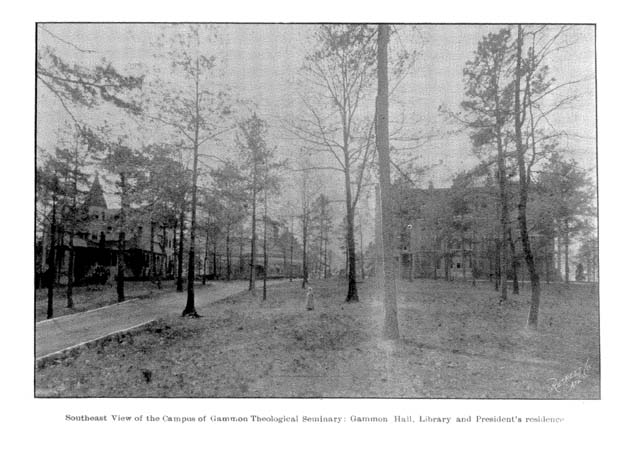

Southeast View of the Campus of Gammon Theological Seminary: Gammon Hall, Library and President's residence

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

AFRICA and the

AMERICAN NEGRO . . .

ADDRESSES AND PROCEEDINGS

OF THE

CONGRESS ON AFRICA

HELD UNDER THE AUSPICES OF THE

Stewart Missionary Foundation for Africa

OF

Gammon Theological Seminary

IN CONNECTION WITH

THE COTTON STATES AND INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION

DECEMBER 13-15, 1895

Edited by Prof. J. W. E. Bowen, Ph.D., D.D., Secretary of the Congress

ATLANTA

GAMMON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY

1896

Page verso

PRESS OF

THE FRANKLIN PRINTING AND PUBLISHING CO.,

ATLANTA, GA.

Page 2

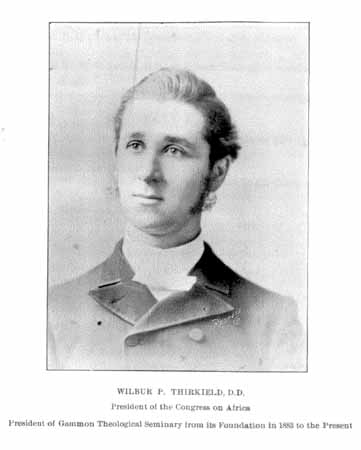

WILBUR P. THIRKIELD, D.D.

President of the Congress on Africa

President of Gammon Theological Seminary from its Foundation in 1883 to the Present

Page 3

Contents

- INTRODUCTION . . . . . 7

The Rev. Bishop I. W. Joyce, LL.D., Chattanooga, Tenn. - THE STEWART MISSIONARY FOUNDATION FOR AFRICA AND THE PURPOSE OF THE CONGRESS . . . . . 9

Prof. E. L. Parks, D.D., Gammon Theological Seminary - OPENING REMARKS . . . . . 13

President W. P. Thirkield, D.D., Gammon Theological Seminary - ADDRESS OF WELCOME . . . . . 15

His Excellency, The Hon. W. Y. Atkinson, Governor of Georgia

- LETTER OF GREETING AND COMMENDATION . . . . . 16

The Hon. E. W. Blyden, LL.D., Liberian Minister to the Court of St. James - LETTER ON THE IMPORTANCE OF KNOWLEDGE OF AFRICA . . . . . 17

Cyrus C. Adams, Editor New York Sun - A BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF AFRICAN TRIBES AND LANGUAGES . . . . . 19

Heli Chatelain, African Traveler and Philologist - RELIGIOUS BELIEFS OF THE YORUBA PEOPLE, WEST AFRICA . . . . . 31

Orishetukeh Faduma, B. D., West Africa - SOME RESULTS OF THE AFRICAN MOVEMENT . . . . . 37

Cyrus C. Adams, Editor New York Sun - THE DIVISION OF THE DARK CONTINENT . . . . . 47

J. C. Hartzell, D.D., Corresponding Secretary Freedmen's Aid and Southern Education Society - OUTLOOK FOR AFRICAN MISSIONS IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY . . . . . 61

Frederic Perry Noble, Secretary World's Congress on Africa at the Columbian Exposition - THE AFRICAN IN AFRICA, AND THE AFRICAN IN AMERICA . . . . . 69

The Hon, John H. Smyth, LL.D., ex-Minister to Liberia - THE POLICY OF THE AMERICAN COLONIZATION SOCIETY . . . . . 85

Thomas G. Addison, D.D., Delegate of the Colonization Society - HEALTH CONDITIONS AND HYGIENE IN CENTRAL AFRICA . . . . . 87

R. W. Felkin, M.D., F.R.S.E., F.R.G.S., ex-Missionary to Uganda

Page 4 - PRACTICAL ISSUES OF AN AFRICAN EXPERIENCE . . . . . 95

Mrs. M. French-Sheldon, F.R.G.S., African Explorer - AFRICAN SLAVERY: ITS STATUS; THE ANTI-SLAVERY MOVEMENT IN EUROPE . . . . . 103

Heli Chatelain, African Traveler and Philologist - MY LIFE IN AFRICA . . . . . 113

Etna Holderness, Bassa Tribe, Africa - MISSIONARY EXPERIENCES AMONG THE ZULUS . . . . . 117

Josiah Tyler, D.D., Forty years Missionary in Africa - CIVILIZATION A COLLATERAL AGENCY IN PLANTING THE CHURCH IN AFRICA . . . . . 119

Alexander Crummell, D.D., Twenty years Missionary in Africa - SUCCESS AND DRAWBACKS TO MISSIONARY WORK IN AFRICA . . . . . 125

Orishetukeh Faduma, B.D., West Africa - THE ABSOLUTE NEED OF AN INDIGENOUS MISSIONARY AGENCY IN AFRICA . . . . . 137

Alexander Crummell, D.D., Twenty years Missionary in Africa - THE METHODIST EPISCOPAL CHURCH AND THE EVANGELIZATION OF AFRICA . . . . . 143

M. C. B. Mason, D.D., Assistant Corresponding Secretary Freedmen's Aid and Southern Education Society - SELF-SUPPORTING MISSIONS IN AFRICA . . . . . 149

William Taylor, Bishop of Africa of the Methodist Episcopal church

PART I

AFRICA: THE CONTINENT; ITS PEOPLES, THEIR CIVILIZATION

AND EVANGELIZATION

- THE AMERICAN NEGRO IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY . . . . . 161

H.K. Carroll, LL.D., Editor The Independent - COMPARATIVE STATUS OF THE NEGRO AT THE CLOSE OF THE WAR AND TO-DAY . . . . . 163

Prof. J. W. E. Bowen, Ph.D., D.D., Gammon Theological Seminary - OCCULT AFRICA . . . . . 175

J. W. Hamilton, D.D., Corresponding Secretary Freedmen's Aid and Southern Education Society - THE STUDY OF FOLK-LORE . . . . . 187

Alice M. Bacon, Secretary Hampton Folk-Lore Society - THE AMERICAN NEGRO AND HIS FATHERLAND . . . . . 195

The Rev. Bishop H. M. Turner, D.D., African Methodist Episcopal Church - THE NATIONALIZATION OF AFRICA . . . . . 199

T. Thomas Fortune, Editor New York Age

Page 5 - AFRICA IN ITS RELATION TO CHRISTIAN CIVILIZATION . . . . . 205

E. W. S. Hammond, D.D., Editor South Western Christian Advocate - THE NEEDS OF AFRICANS AS MEN . . . . . 211

R. S. Rust, D.D., Honorary Secretary Freedmen's Aid and Southern Education Society - THE NEGRO IN HIS RELATIONS TO THE CHURCH . . . . . 215

H. K. Carroll, LL.D., Editor The Independent - AFRICA AND AMERICA . . . . . 219

Joseph E. Roy, D.D., President World's Fair Congress on Africa - MINUTES OF THE DAILY SESSIONS . . . . . 227

- SPECIMEN HYMNS SUNG AT THE CONGRESS . . . . . 236

- APPENDIX A--TABLE OF BIBLE TRANSLATIONS (The Whole or Portions) . . . . . 239

Robert Needham Cust, LL.D., author of Modern Languages of Africa - APPENDIX B--ALPHABETICAL LIST OF MISSIONS . . . . . 240

Robert Needham Cust, LL.D., Author of Modern Languages of Africa

PART II

THE AMERICAN NEGRO: HIS RELATION TO THE CIVILIZATION

AND REDEMPTION OF AFRICA

Page 6

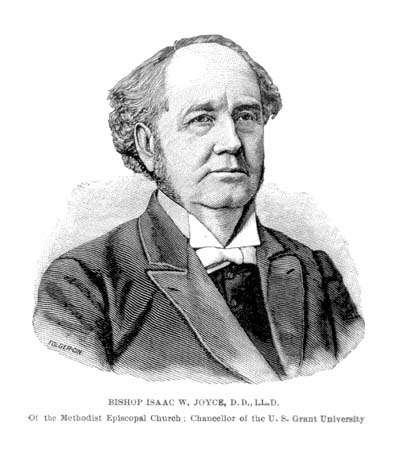

BISHOP ISAAC W. JOYCE, D.D., LL.D.

Of the Methodist Episcopal Church; Chancellor of the U.S. Grant University

Page 7

INTRODUCTION

A congress on Africa! Why not?

What land is more entitled to our best thought, or more deserving the most helpful service we can render? Where the country with a history of more romantic interest, or one whose peoples have had a more varied experience or presented more serious problems for the study of mankind? Men, whose names are among the greatest in history, have been its explorers, and the students of its languages and of its dialects. It is so rich in soils and in minerals as to excite the greed of the world, and the nations of the earth have contended with each other for a division of its treasures. In the interests of commerce the steamers of the merchant princes navigate its waters, and the markets of the world are open to its products. A literature on Africa, rich in every way, has been created by scholarly men, who have made the most heroic sacrifices that they might acquaint the world with the present greatness and future possibilities of "The Dark Continent." These men, and others such as they, will continue to enrich with the best equipments those who wish to wisely study the many phases of the growing questions in relation to Africa. This Congress was surely in the order of Divine Providence. God uses men in the development of His plans. In this instance it was His servant, the Rev. W. F. Stewart, through the agency of whose consecrated wealth this "Missionary Foundation" was established, and the holding of this congress was made possible. Men of scholarship, and imbued with the spirit of Christ, deeply interested in the evangelization of Africa, came together from various parts of the United States and other countries, and presented well prepared papers on the subjects which had been assigned them. The discussions which followed revealed mental grasps of the subjects and the hearty interest of the speakers in the principles underlying the whole question. From the beginning of the congress to its close the audiences were large and the interest very great.

The utmost harmony prevailed in all the deliberations, and this volume, which is the result of the congress, is an evidence of the oneness of spirit that was at all times manifest, and also of the fervent conviction that pervaded all hearts that the Church of the Lord Jesus Christ ought to arise and go forth and evangelize Africa, thus obeying the command of the Lord to "Go into all the world."

That she is able to do this there can be no question; that it is her duty to do this, all will agree; but will she do this great work? Our faith answers: Yes. The establishment of this Missionary Foundation is a strong testimony that the Holy Spirit is drawing the thoughts and hearts of the servants of God to the ever-crying needs of "The Dark Continent," and a careful reading of the pages of this book will make impressions which will strengthen the testimony

Page 8

in favor of this truth. It would be well, from time to time in the coming years, for those in charge of this great interest to hold other congresses of like character and purpose with this one, and thus widen and intensify the influence of "The Stewart Missionary Foundation for Africa," in its association with Gammon Theological Seminary. Thus in all the years to come the names of Stewart and of Gammon would be blended in the thoughts and love of all good men, and the wealth they consecrated to the enlargement of the Kingdom of Christ among men would be multiplied many times in power for good and increased in influence for righteousness through all time, even unto the end of the world.

ISAAC W. JOYCE

Chattanooga, Tenn.

REV. WM. F. STEWART, A. M.

Establisher of the Stewart Missionary Foundation for Africa in Gammon Theological Seminary; For Fifty-Two Years member of the Ohio, then of the Rock River, Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church; For many years one of the Trustees of the Northwestern University of Chicago.

Page 9

The Stewart Missionary Foundation for Africa

and the Purpose of the Congress

BY

PROF. E. L. PARKS, D.D.

GAMMON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY

This Foundation is in the interest, especially among American Negroes, of missionary work for Africa. It has been established by Rev. W. F. Stewart, A. M., of the Rock River Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. It is the outgrowth of many years of thought in the consecration of a large portion of his property. In a letter in the early part of the correspondence leading to the establishment of the Foundation, Mr. Stewart thus comprehensively states the purpose of the Foundation:

"My hope is that it may become a center for the diffusion of missionary intelligence, the development of missionary enthusiasm, the increase of missionary offerings and through sanctified and trained missionaries hasten obedience to the great commission to 'preach the gospel to every creature.' In addition to the direct work of the recitation room, I have contemplated other educating means that would reach our schools and missions and the whole membership of the church."

Mr. Stewart has set aside for the endowment of the Foundation a group of farms in Central Illinois, comprising in all some six hundred acres. The whole tract is tile-drained in a systematic and thorough manner, so as to make every acre of it first-class tillable land.

In placing this Foundation in connection with Gammon Theological Seminary, Mr. Stewart unites it with a largely endowed institution, which is central and at the head, in theological education, of one of the greatest systems of schools for the Negro in America. The Foundation fills an important place in the very purpose for which the Seminary was established. All the forces of the Seminary are used to reduplicate the influence of the Foundation. There is not only a remarkable parallel in the work of Mr. Gammon and Mr. Stewart, but the fundamental thought which was back of their work is also in perfect accord. This clearly appears in the following, which shows also that Elijah H. Gammon was our prophet, as well as the founder of the Seminary. As early as August, 1887, he wrote:

"I believe it most thoroughly, as Ethiopia stretches out her hands to God, help must come through your school. Who but you can furnish the thousands of missionaries for Africa? You may as well attempt to understand and comprehend the astronomy of the heavens as the possibilities of your school."

The work of the Foundation has been inaugurated by offering prizes for

Page 10

essays and orations on Africa as a missionary field, the obligation of the American Negro to missionary work in Africa and kindred themes, and for missionary hymns. The object of offering these prizes is to encourage thought and investigation, spread intelligence and stimulate personal and property consecration among the American Negroes for missionary work in Africa. These prizes are offered, among the colored people, to the students of all the schools of the Freedmen's Aid and Southern Education Society, and to all the local churches of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Correspondence, to secure the prompt coöperation of all interested, is invited.

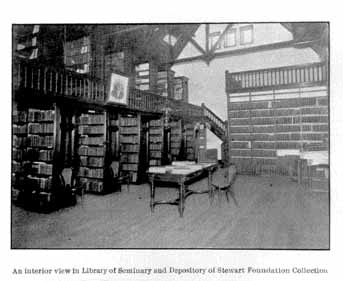

The Foundation is also gathering a special library on Africa. The nucleus already has been pronounced, by expert judges, one of the best in the country in the general field of African exploration and missionary work. The Foundation is also collecting an African museum. This collection already includes a large number of specimens of African handiwork in wood, iron, brass, cloth, grass, etc., which reveal very clearly the native genius and artistic skill of the untutored African. In addition to the above, out of a list of five hundred or more stereopticon slides, there have been selected about two hundred superior views for use in the stereopticon of the Seminary. These native fabrics and curios, as well as the stereopticon slides, will be used in the schools and churches to illustrate the products, industries and scenery of Africa, and the conditions and life of its peoples. These are only the beginnings of the collections of books and illustrative material on Africa and its peoples, which it is hoped will be made among the greatest of their kind in this country. They are deposited in the practically fire-proof library building of the Seminary. Donations are invited.

As a very important means in carrying out the purpose of Mr. Stewart in establishing the Foundation, as stated in the foregoing, the President of the Seminary, with the coöperation of the Faculty, suggested to Mr. Stewart the feasibility of a congress on Africa. Mr. Stewart heartily approved the plan. Through Mr. I. Garland Penn, Chief Commissioner of the Negro Exhibit, it was made one of the auxiliary congresses of the Cotton States and International Exposition at Atlanta.

In all the plans of the congress the Faculty of the Seminary kept in view the general purpose of the Foundation, the promotion of the interests, especially among American Negroes, of missionary work for Africa. The industrial, intellectual, moral and spiritual progress of the colored people in America is a prophecy, both of what they will become and will do for the redemption of their fatherland, and also of what the native African is capable of becoming. For this reason, it was thought wise to include in the program addresses and papers on the American Negro, by the side of those on African exploration, native peoples, languages and religion, and the opportunity, means for the promotion, and progress of civilization and of missions in Africa.

Page 12

PART I

AFRICA: THE CONTINENT; ITS PEOPLES, THEIR

CIVILIZATION AND EVANGELIZATION

Page 13

Opening Remarks

BY

PREST. W. P. THIRKIELD, D.D.

GAMMON THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY

It is a most grateful task that falls to me, as President of this Congress, to welcome you, as delegates and friends, to the first Congress on Africa ever held in the South. This great audience at the opening session emphasizes the interest of the people in the program prepared for this occasion.

This Christian Congress indicates that God is stretching forth his hands to Ethiopia--to that "Dark Continent" which, through long and dolorous ages, has been vainly stretching forth its hands unto God.

While light is breaking in upon its darkness, the hand that blights and curses is not yet lifted. In other centuries the curse was the stealing of Africans from Africa. Now, it is the game among European nations of "shut your eyes and grab" in their efforts to steal Africa from the Africans. But God is yet in that world. Not in vain has its two hundred millions stretched forth their hands to Him. He causeth the wrath of man to praise Him. Even through the greed and wars of nations, in their selfish partition of Africa, He shall yet "save many people alive."

This Congress comes to take its place in the ever-widening plans of God for Africa. It should now be said that the original intention of the projectors of the congress was to hold it, as announced, during April, 1896. On account of the Cotton States and International Exposition, it was decided, as late as September, that the date should be changed, so as to reach and influence a larger number of people from all parts of the nation and of the world. This has necessitated some change in our plans. We congratulate ourselves, however, that we are able to present a program of such value and importance, and that the speakers, representing three continents, are now present, with two exceptions. Dr. Blyden is detained in London by serious illness. These places on the program are to be well filled, respectively, by a venerable and honored missionary with forty years experience in Zululand behind him, and by a special delegate from the American Colonization Society.

This Congress will have a large, practical tendency. It has definite aims in view. Problems of the most serious interest are before us. This nation is, in a peculiar sense, under bonds to Africa. It must come to see its duty. It must be stirred by an outlook upon its immense opportunity. We aim, therefore, to give the public clearer views of Africa and of the African movement. From a survey of the knowledge and experience gained in the last twenty-five years we should be able to deduce general principles and definite plans that may influence future work in the line of commercial, industrial, civilizing, and redeeming effort.

Page 14

One of the vital and urgent problems before us is the relation of the American Negro to the civilization and redemption of his Fatherland. God's hand must be recognized in his presence in America. This is now the home and heritage of these American born of the colored race. Here he will stay. But the forefinger of that same Hand that brought him hither points the way to Africa for the tens, the hundreds, and, in future years, to the thousands who shall be agents of God in the redemption of the Dark Continent. It will appear that the call is not for the weak, the poor, the ignorant of the race. Such may only relapse into barbarism. But Africa now needs the best brain, and the best heart, the finest moral fiber, and the most skilled genius and power that the American Negro can furnish for her civilization and redemption.

To give light on these problems is the definite aim of this Congress. You shall have presented to you the latest and most accurate information on Africa; you shall have set forth clearly by word, by maps, and by illustrative slides, the land and people as they are; the life, character, customs of the natives; their tribal relations, and languages; the progress of discovery and occupation; the latest work of geographers; the march of civilization; the partition of Africa; the achievements of missions; the difficulties and drawbacks of missionary effort, and the outlook of missions for the nineteenth century.

We may congratulate ourselves that on our program there are speakers representing three continents; that we are to hear venerable and heroic missionaries who have labored from one to two score years in Africa; travelers who have penetrated the dark regions of Africa; Africanists of world-wide fame; scholars who have made original discoveries in the languages and in the religious beliefs of the people; natives of that last and most interesting of the continents, who bring the knowledge of personal life and experience, and whose presence and words furnish the strongest appeal for the civilization and redemption of their people.

I take pleasure in turning over the chairmanship of this session to Bishop I. W. Joyce, of Chattanooga, who will present to you His Excellency Governor Atkinson, of Georgia, from whom we shall have the address of welcome for this Empire Commonwealth.

Page 15

Address of Welcome

BY

HIS EXCELLENCY, THE HON. W. Y. ATKINSON

GOVERNOR OF GEORGIA

[The following is a condensed report of the Governor's address, giving his most memorable sentences, as they were taken down at the time.]

Fellow citizens:

It is entirely proper that Georgia should take a leading part in a work of this character. Her first settlers were from the oppressed. They were actuated by a spirit of philanthropy which would lead their settlement to be a blessing to mankind, including Africa. Though pressed with many official duties, I am here to attest my interest, as the Governor of the State and as an individual, in this work.

A mysterious Providence has been over us. Slavery cannot be justified. But may not God have intended that you, who are the descendants of those whom slavery brought to this country, should pray and work for the redemption of your fatherland?

There is no higher duty resting upon the Governor of the State of Georgia than to advance the education of the people of the State without regard to color. If any doubt that the colored man can be educated existed, it has all been dispelled by my attending the commencements of the colleges of the State for the colored people. It is natural, proper, noble to look beyond yourselves and your country to save the people of your fatherland. No government, no society, can settle whether you should return to reside in Africa. You are free, independent citizens, and you must decide for yourselves, on the principles of your duty and your interest, whether you will reside in Georgia or in Africa. But in saving men and women from sin, degradation and hell, it is sometimes necessary to forego and forget interests. The great are not alone those who shine in high places. There are great souls careless of reputation among men and who are seeking only the approval of God.

So long as the colored man remains in Georgia, so far as is in my power, I shall see to it that he is fairly and justly treated--that he receives his rights. The Anglo-Saxon cannot defend the honor and reputation of his race by injustice to his fellow-man.

Do your duty, and for results trust in God.

Page 16

Letter of Greeting and Commendation

BY

THE HON. E. W. BLYDEN, LL.D.

LIBERIAN MINISTER TO THE COURT OF ST. JAMES

28 Nov., 1895

, 3 Coleman Street, London, E. C.

Dear Dr. Thirkield:

You will regret to learn that I have been very ill since I left America, having taken a severe cold on the steamer coming over, where there was no heating apparatus in operation, and I could only keep warm in my berth by wearing my overcoat.

The "Congress on Africa" at this time is most opportune, when all the world is looking to that continent as a field for political, commercial and philanthropic effort. I hope that the results of the congress upon the Negro population of your country will be such as to lead them to take greater practical interest in the land of their fathers.

There will be, within the next few years, mighty developments on that continent. The British government are taking most active interest in the exploitation and building up of regions which have been for generations scenes of warfare and carnage. Such is the enthusiasm here for opening Africa, that when it was learned, only a few days ago, that the so-called King of Ashantee was placing obstacles in the way of England's efforts to bring that country within the pale of civilization, a magnificent expedition was organized at once, consisting of the flower of the British army, and dispatched to the scene. Two of the British princes have joined the expedition, which is intended not so much to fight as to convince the refractory chief of Coomassie, and all others like him, how utterly useless it is to attempt to cling to the hoary and pernicious superstitions of the past, and oppose efforts for the amelioration of the condition of their people.

Nothing is clearer to my mind than that it is the duty of a superior civilization to assist--not to exterminate--in the elevation of the inferior or backward populations of the earth, and your congress, I trust, will be one of the Providential agencies in the promotion of the magnificent work of Africa's regeneration.

Believe me, dear Dr. Thirkield, yours faithfully,

EDWARD WILMOT BLYDEN

Page 17

Letter on the Importance of Knowledge of

Africa

BY

CYRUS C. ADAMS

EDITOR New York Sun

The colossal work of twenty-five years has proved that the African native, in his own home, must be the foremost agent in reclaiming his continent. This century, having established the broad lines upon which the work must proceed, bequeaths to coming generations the privilege of helping the African to attain his full stature and development.

The most powerful motives, philanthropic and selfish, incite and will sustain this work; for the world needs Africa, and knows, to-day, that mankind will never profit by a tithe of her resources until the strength of Africa's millions, intellectual, moral and physical, are added to productive energy; and further, that the African's capacity for the development so essential for his own good and the world's, is being, year by year, most conclusively demonstrated.

All friends of Africa should scrutinize every phase of the work, as it goes on, so that the sentiment of civilized nations may be voiced in powerful and effective protest if intelligence, patience, humanity and justice do not shape all policies relating to Africa and her peoples.

CYRUS C. ADAMS

Page 18

HELI CHATELAIN

African Philologist; Organizer of the Philafrican Liberator's League; Editor of African Terms and Names in the Standard Dictionary, and in the Century Dictionary of Names; Author of "Folk-Tales of Angola," Grammar of Kimbundu; "Comparative Grammar and Vocabularies; "Bantu Notes;" and late African Traveler, Missionary and United States Commercial Agent at St. Paul DeLoanda

Page 19

A Bird's-Eye View of African Tribes and

Languages

BY

HELI CHATELAIN,

AFRICAN TRAVELER AND PHILOLOGIST; AUTHOR OF "FOLK-TALES OF ANGOLA"

Our knowledge of African tribes and languages is still very imperfect. Every specialist who undertakes to study any single tribe or language is soon impressed with the fact that the little information he can get hold of, either in print and manuscript, or by correspondence and conversation, is far from being scientifically accurate or worthy of implicit confidence.

The outline of African ethnography and philology given in this paper is simply a resume of a critical study of the available material, and therefore no more infallible than this.

If we first consider the races represented in Africa, we find conflicting classifications and contradictory descriptions among scientific men, while in books of travel and periodical literature the wildest confusion of names is indulged in.

Some scientists hold that all native Africans belong to one racial stock with numerous ramifications.

This view is founded on the strong resemblances and common features which are observed in all populations of the Dark Continent. It brings out certain truths which it is well to retain, but the theory is far from proved.

Others insist on a certain number of races with clean cut characteristics and demarcations. They make us realize more the differences than the resemblances between the great sections of African population.

In English literature, taken generally, Dr. Cust's linguistic map of Africa made on Friedrich Muller's plan, has been taken, or mistaken, for an ethnologic map; and his linguistic divisions, which are useful if rightly understood, have been used by hasty readers and writers as a kind of standard classification of African races.

For practical purposes, it seems best to divide African tribes, according to the prevalent tinge of their skin, into white, black and brown races. In the Sudan, the brown, with all the intermediary shades between white and black, seems due to a mixture of white and black. The geographical position of these brown tribes between the white and black, the mixed nature of their languages, as well as historical data, renders this double origin almost more than probable.

While the confusion of linguistic and ethnologic names is sadly misleading, it must be confessed that the linguistic work is exceedingly valuable for

Page 20

ethnographic identification. There remains the great fact, that apart from political influences, great classes or families of languages correspond to great races, and that there is a parallel affinity between linguistic and ethnologic divisions.

THE WHITE RACE

Beginning with representatives of the white race, we first notice the Arabs, whose language and features are Semitic. They entered Africa from Arabia in four or five migrations, all in historical times. The most important branch invaded North Africa through the isthmus of Suez and conquered all Northern Africa, implanting everywhere Moslem culture and the Arabic language. That wave of Mohammedan conquest, passing over North Africa, wiped out the Christian religion, but failed to tread out the Hamitic languages, or to efface the ethnologic features, of the subjected tribes. The present states of Morocco, Tunis, Tripoli and Egypt are the remains of that conquest of Islam. The Egyptians, who were Hamitic Christians, gradually lost their language, and to a large extent, their Christian religion, but retained the racial features of the Hamites.

A second branch of Arabic Semites crossed the Red Sea and settled in the mountains of Abyssinia. The old Ethiopic and the modern Amhara and Tigre, languages of Semitic type, were wedged into Hamitic languages, but failed to supersede them. As to the racial features of the Semitic invaders, they were largely lost by inter-marriage.

In the Egyptian Sudan is found a third branch of Semites, leading a nomadic life. They also crossed the Red Sea.

From Muscat and the South-East corner of Arabia came a fourth branch, which founded settlements all along the East-Coast of Africa. In recent times they have gone from Zanzibar to the Great Lakes, and far into the Kongo Basin.

Although Moslem religion and culture are superior to African heathenism, it must be admitted that the Arabs have been a curse to Africa. We can be justly thankful that their political power is on the wane, and its final destruction inevitable. The Mohammedan religion, which has been introduced and upheld largely by the sword and the rifle of the Arabs, must necessarily suffer from the overthrow of Arab supremacy; and the final enforcement of European rule will be the signal for a wholesale desertion of a religion which has affected the externals more than the hearts and consciences of its African adepts.

The pure Arabs have never been numerically strong in Africa. They form only a fraction of the Mohammedan population speaking or understanding Arabic. Therefore, even if the Arabs and their religion finally disappear from the continent, their beautiful language is likely to remain in Egypt and all Northern Africa.

The Hamites are also considered as belonging to the white race. But in reality the white type with fair hair and blue eyes is only met with among a few tribes of Berbers. These blue-eyed Berbers were sometimes believed to be descendants of the German Vandals or more ancient immigrants from Europe, but the present tendency is rather to view them as of pure Hamitic

Page 21

stock. The bulk of the Africans speaking the Hamitic languages are more or less colored, and many Galla and Somal come nearer the negro than the white type.

Most writers believe that the Hamites, like the Semites, passed into Africa from Asia, but in prehistoric times. The ancient Egyptians were Hamites, and are supposed to have closed the march of Hamitic migration into Africa.

Moses says that "the sons of Ham were Cush, and Mizraim, and Phut, and Canaan," and the present scientific division of the Hamites still rests on the genealogic table of Moses.

Mizraim was Egypt, the present Lower Egypt. There, was developed the first great civilization. From Egypt came the Libyans, who spread over North Africa, the oases of the great desert, and even to the Canary Islands. The Christian descendants of the ancient Egyptians are the Kopts. The descendants of the Libyans are the Berbers.

The ancient Carthaginians, though speaking a Semitic language, were also originally Hamites of the Punic branch.

Cush represents the inhabitants of Abyssinia and Upper Egypt,.known to the Greeks and Romans as Ethiopians. This term Ethiopian comprehended also the Negroes; but the Egyptians, who were in immediate contact with both, had a special name for the Negroes, calling them nahasi.

The Phut of Moses and the Puna of the Egyptians were probably the red-brown people of both coasts of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean, about the gulf of Aden. Vestiges of Hamitic tribes have recently been found in Southern Arabia. Probably the modern Somal and Galla are the descendants of the ancient Puna, from whom the Egyptians obtained incense, gold, ivory and Negro slaves.

The Berbers, though whites by race, and cousins of the Egyptians and Carthaginians, have never united into a powerful nation nor developed a culture decidedly superior to that of the Negroes south of the Sahara. Some inhabit the oases Siwa and Djala and parts of Tripoli and Tunis. Those of Algeria and Morocco are descended of the Roman Numidians and are frequently called Moors. In Algeria they number about two millions, of whom seven hundred and fifty thousand speak only Berber dialects, while the other one and a quarter million speak either Arabic, in addition to Berber, or Arabic alone. The Zouaves of the French army are a tribe of Berbers, inhabiting the sea-board between Algiers and Constantine. In Morocco the famous Rif pirates are Berber by race and language, and the Berber dialects Mazirgh and Shluh are still spoken from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic coast, opposite the Canary Islands.

The extensive, but arid region between Algeria and the northern bend of the Niger is inhabited by the Berber tribe of the Imoshagh, whom the Arabs call the Tuárek. Their Hamitic language is the Tamashek. Although favored with an original system of writing, in which many inscriptions have been preserved, the Imoshagh have failed to produce a national literature.

In the Nile Valley, between the Red Sea and the river, from lower Egypt to Abyssinia, the Bedja or Bisharin have upheld to this day Hamitic speech and type. The four principal tribes, the Ababde, Hadendoa, Beni-Amir and

Page 22

Hallenga, speak each a dialect of its own. Commonly they are known as Nubians, but this name is more properly applied to their neighbors on the banks of the Nile, who are of Negro extraction and who speak a language of nigritic structure. The Bisharin are pastoral and nomadic. They have all adopted Islam, and followed the Mahdi in his revolt.

The Danakil or Dankali, between Massawa and Obokh, are Hamitic and Pagan, but claim to be Arabs and Mohammedans. Their principal dialects are Saho and Afar.

Between the gulf of Aden and the equator, the eastern Horn of Africa is in the possession of the numerous tribes of Somals who are Hamitic by language and by descent, and Mohammedan by faith. In the North they are mixed with Arab blood, and with Negro blood in the South. Owing to this they vary much in color and form. Naturally jovial and sociable, they are fiercely opposed to foreign intrusion, and cordially hate their neighbors and kinsmen, the heathen Oroma or Galla. They tend their herds of camels, horses, oxen and sheep, while their limited agriculture is left to domestic slaves.

The Galla, whose number is estimated at 3,000,000, and who dwell between the Juba river and Albert Nyanza, are so called by their enemies, the Somal. They call themselves Oroma or Ilmorna, that is, "men." In race mixed Hamitic and Negro, in language and customs purely Hamitic, in religion partly Christian, partly Mohammedan, but mostly heathen, they are brave, intelligent, and industrious. Their government is largely republican, and they keep no slaves. The royal families of Uganda and Karagwe were originally Gallas of the Huma tribe.

Both Galla and Somal have preserved their languages remarkably pure from foreign loan-words; so much so that more archaic and primitive forms are found in them than even in hieroglyphic Egyptian.

The Egyptian, Berber and Cushitic languages which we have just considered are all so homogeneous in structure and word-store that they evidently form one family, derived from one mother-tongue.

In religion the Hamites are mostly Mohammedan. About one-quarter of a million Kopts in Egypt and several tribes in Abyssinia are Christians, 50,000 Falasha are Jews, and a portion of the Galla as also several tribes in or about Abyssinia are heathen.

Everywhere, except in lower Egypt, the Hamites are rather nomadic and pastoral, broken up in petty tribes, and jealous of their tribal independence.

No race, perhaps, is at the present time so little evangelized by Protestant missions.

BROWN RACES

Brown races are found in the Sudan, in southwest Africa and in Madagascar. They have nothing in common except the color. Nor is their brown color of the same tinge, some being light brown, others dark brown.

The brown people of the Sudan are probably a mixture of Hamites and Negroes; the Hottentots, Bushmen and Pygmies differ from the other brown peoples of Africa in structure, stature and physiognomy; and the brown Malagassy of the eastern and central portion of the great Island of Madagascar are Malays who have likely immigrated from Sumatra; at least linguistic affinity seems to indicate this.

Page 23

It is in the ethnographic and linguistic classification of the Sudan tribes that we meet the greatest difficulties. Owing to the mixed character of racial and linguistic features different authors class the same tribe with the Hamites or with the Negroes, with the Berbers or with the Somal, or constitute it with other tribes into new groups, sub-divisions or families.

The Fulbe or Fulahs are scattered through the Sudan from Senegal to Wadai, and south to Adamawa. They are reddish brown, with straight nose and curly hair. Some differ but little from the Berbers while others look almost like negroes. Their language is remarkable for its peculiar initial formations. It can boast of a considerable literature written in Arabic character. By faith the Fulbe are Mohommedan, but not fanatical. Pastoral, like most Hamites, they are warlike, intelligent and industrious, ruling over negro tribes in Futa-Jallon, Kaarta, Segu, Massina, Gando, Sokoto, Adamawa. Around Lake Tshad, in Bornu, Baghirmi and Wadai, they are too weak in numbers to assume command. It was in the beginning of this century that they revolutionized the Sudan, founding under Otman dan Fodio their great kingdoms, which are not yet on the wane. They, and many of their negro subjects, are by no means savages or barbarians. Their populous cities are well built and evince an advanced stage of Moslem culture. Recently their territory has been included in the French, British and German spheres of influence. According to A. W. Schleicher they are a branch of the Somal; and would thus have traversed the whole continent in its greatest width.

The gap between the eastern Fulah around Lake Tshad and their cousins, the Galla and Somal, is largely filled by the Nyam-Nyam and Mombuttu, the Masai and the Kuafi, whose physique and languages show also an intermediate position between Hamites and Negroes.

Fried. Müller has joined to the language of the Nyam-Nyam or Azande those of five neighboring tribes: the Kredj, the Golo, the Amadi, the Mangbatu and the Abarambo, and constituted them into an Equatorial Family. Their territory is practically the only one in Africa which is not yet assigned to one or more European powers. It has also remained perfectly virgin of any misionary enterprise on the part of Christians. But it will not remain so long, since the discoveries of Van Gèle and others have made it accessible through the Kongo and its mighty northern affluent, the Mobanghi.

The Nyam-Nyam or Azande are said to number about two millions. They come very near the negro type in color and hair, but many peculiarities show a mixed origin. They are clever workers, hunters and musicians, but indulge in cannibalism.

The great and progressive nation of the Fang between the Gaboon and the Nyam-Nyam speak a very corrupt form of Bantu speech, and have many points of contact with the Azande.

The Masai and Kuafi, between Lake Victoria and the snow-capped peaks of Kenia and Kilimanjaro, have wedged themselves in among Bantu tribes as far south as the latitude of Zanzibar and the mouth of the Kongo. The fact that trustworthy witnesses class them physically with the Hamites and with the negroes, and that linguists are equally at variance concerning their language is strong evidence in favor of the theory that they are of mixed Hamitic and

Page 24

Bantu-Negro origin. They have a peculiar social organization. The young and able-bodied men lead a military life in camps, keeping the women in common, while the old men, women and children inhabit the villages and tend the cattle. The language is connected with that of the negro Bari.

The Nubahs of the Nile Valley, between Dongola and Assuan, were probably once pure negroes like their cousins, the Hill-Nubahs; but long intercourse with neighboring Hamites has so far altered their type that they are often confounded with these. The language, however, has preserved more distinct traces of their origin.

The Hottentots, or Khoi-Khoi, occupying the arid southwestern portion of Africa, are a brown people with very peculiar characteristics. They have all the distinctive features of the Negro, even exaggerated, but their color is much lighter, their stature inferior, while their straight and large forehead dwarfed nose, tapering chin and plentiful wrinkles give them a physiognomy atonce distinguishable from that of the negro. Their language reminds one by the formation of genders of the Hamitic family, while the classification of nouns savors of Bantu affinity and the numerous musical tones added to monosyllibic tendency are like an echo of Chinese parentage. What is most striking to a stranger is the clicks which are produced with tongue, palate and lips. Are the Hottentots bastards of the Bantu-Negroes with prehistoric Punas of Hamitic stock who worked the gold mines of Mashona-land and left the ruins of Zimbabie? Or are they descended from miscegenation with south-eastern Asiatics of the Chinese type who preceded the Malays of Madagascar in their far westward voyage, or were these three elements blended with Bushman blood?

The next twenty or thirty years will no doubt furnish material that will help decide this question with a probability not far removed from certainty.

The Hottentots are pastoral, and fairly intelligent. They have adopted Cape Dutch in the Cape Colony, while the Nama of German Southwest-Africa, have largely retained their own language. It is estimated that 350,000 Namas between the Orange and Kunene rivers, and 30,000 Hill-Damaras of Negro race, still speak Khoikhoi. A large proportion of the Hottentots is Christianized.

The Bushmen, or San, of South Africa, belong to the same race as the Pygmies or dwarfs of the Central African and equatorial forests. Their stature varies between four and five feet. Their physical appearance and their language show affinity with the Hottentots, but the relationship is very remote. The San language is poorer in morphology than the Khoikhoi, but richer in clicks. The Bushmen, like the Pygmies, are exceedingly timid, and hover, as Helots, on the skirts of Bantu settlements, which they supply with game. The Hottentots, on the contrary, are pastoral, independent, and even aggressive. They are the terror of less audacious and less advanced Bantu tribes. Perhaps no savage people on earth excell the Bushmen as hunters; and their rock-paintings show decided artistic aptitude.

Both Hottentots and Bushmen are not numerous enough to resist, independently, the absorbing influence of their Bantu and European neighbors.

The Pygmies of Central and Equatorial Africa form, most probably, one

Page 25

ethnic class with the Bushmen of South Africa. Their language, however, is not yet sufficiently known to warrant the expression of an opinion as to kinship with San. They are hunters and fishermen, living in temporary grass huts of bee-hive shape, and keep no domestic animals save chickens. Though culturally on the lowest scale, they are said to possess many virtues; and may, under the regenerating influence of the Gospel, develop some sterling qualities and attain pre-eminence in certain specialties.

Ba-rwa, Ba-twa, Ba-kwa, Ba-chwa is the common name of the Bushmen and Pygmies from one end of the Bantu field to the other, and should, in the form Ba-twa, be applied to the whole race or class. They have been noticed north of the Zambesi, at the head of Lake Nyassa, in the Nguru mountains near Zanzibar, on the Lulua, on the Sankuru and in the horse-shoe bend of the Kongo, in the Kuango valley, in French Kongo, on the Aruwimi, on the Blue Nile, and in Abyssinia.

THE NEGRO RACE

The field that is left to our consideration after we have disposed of the white Hamites of North Africa, the mixed brown peoples of the Sudan, the Malays of Madagascar, the Hottentots of South Africa, the Bushmen and the Pygmies, is all occupied by the Negro race, which forms the bulk of the African population, and fully deserves to be called the African race par excellence. The Hamites and semi-Hamites are mostly scattered in loose bands through the arid stretches of North Africa. Their unproductive soil, their nomadic habits, and their Mohammedan fanaticism preclude any rapid development of their countries and any phenomenal rise in civilization.

Nearly all the land occupied by the Negro race is rich in minerals and in fertile soil; it is watered by abundant rains and numerous rivers. The tropical sun matures in the same field two or three yearly crops of fruits, vegetables, and cereals, which in the temperate zone yield only once a year. The Negro is agricultural, commercial and industrial, of a peaceful and teachable disposition. In the Pagan state he has no religious creed to oppose to Christianity. If this religion and civilization had been presented to him free from man-stealing, commercial cheating, rum-poisoning, and blood-shedding exploration, from voracious land-grabbing and wholesale village-burning, the end of this century might have witnessed a rush of thousands into the bosom of the Christian church, a colossal demand for civilized manufactures, and torrents of tropical produce flowing northward to Europe and westward to America. But it is useless to expect ideal perfection from man, or to worry over what cannot be altered. Let us be thankful for the progress in knowledge, in politics, in religion, and, chief of all, in methods, as compared with similar movements in the past.

When I speak of the Negro race in Africa I include the so-called Bantu, who are probably, in race as well as in language, the purest stock of the black-skinned and woolly-haired variety of mankind. The distinction of Bantu and Negro races is a myth. The Negroes of Upper Guinea and the Sudan form one compact and homogeneous race with the Bantu of the Kongo Basin; their physical, mental and moral characteristics, their religious views, their folk-lore, and their social order is one and the same. The Negroes south of the

Page 26

equator, the so-called Bantu, speak languages ruled by a common grammar and possessing a common word-store, thus forming one great family of languages; while the Negroes north of the equator, that is in the Sudan and Upper Guinea, speak languages which have retained more or less grammatical forms of Bantu grammar and word roots of Bantu origin, but these ruins are overgrown by a rank and wild vegetation which it will take philology a long time to penetrate. It is, however, easy in some of the better known languages spoken by Sudan Negroes to discover traces of distinctly Hamitic influence.

The physical characteristics of the black or Negro race are: A large and strong skeleton, long and thick skull, projecting jaws, skin from dark brown to black, woolly hair, thick lips, flat nose and wide nostrils. The typical color of the race is not coal black but the dark brown of a horse chestnut. Observation shows that the darkest specimens are found on the borders, where Negroes have been in contact with lighter races, while in the population of the Kongo Basin, which has been almost completely free from mixture, the dark-brown type prevails.

If we begin our survey of Negro tribes in the North, we first notice the Teda or Tibbu, who hold a large tract of the Sahara desert, north of Lake Tshad, in the very heart of the Hamitic field. No wonder that owing to this position, both the race and the language have paid rich tribute to the Hamitic surroundings.

From Senegambia to Lake Tshad, we have seen that the Negroes are mostly ruled by Fulah conquerors, who have founded great sultanates, which have swallowed up the native Negro kingdoms and their names.

In Wadai, east of Lake Tshad, the government is still in the hands of Negroes, who have maintained their independence against Arabs and Fulahs, thanks to their Mohammedan fanaticism. Wadai even exercises a sort of sovereignty over the neighboring kingdom of Baghirmi, where the bulk of the population is also Negro.

In Bornu, the government is Fulah, and the Negro population strongly mixed with Imoshagh and Arabs, all professing the Mohammedan religion. In Sokoto, the population is Hausa, who are Negroes, but slightly mixed with Hamites. They are the most promising nation of the Sudan, and their language will probably manage to compete with Arabic and English over the vast area between Lake Tshad and the Niger. It is among the one hundred millions of Sudanese that Islam is still making important progress; and there at least it seems to raise the heathen to a higher plane of life.

The peoples of Upper Guinea are mostly heathen, but widely honeycombed by Christian missions.

The Wolofs of French Senegambia, near St. Louis, are very black, well built, less prognathic than Negroes generally, and their language differs considerably from that of their neighbors.

Around Sierra Leone we find the Susu, Temne, and Mende tribes. Their languages have so much of Bantu structure that they deserve to be called semi-Bantu. In Liberia, we notice the Vei, made famous by the original syllabic character invented by one of their tribesmen; and also the athletic and hard-working Kru-men, one of the most promising nations of the west coast.

Page 27

On the pestilential Gold and Slave coasts, the Ephe, the Ga, and the Tshi speaking people, including the once important kingdoms of Asante and Dahome, are being thoroughly evangelized by the heroic workers of the Basel and Wesleyan missions.

In the Lower Niger basin, the Yariba, the Nupe, the Ibo and the Efik, all speaking languages with crippled remains of Bantu grammar, are rapidly emerging out of the cruel rites of heathenism, and rising into prosperous Christian communities.

At Kamerun we strike the great field of the Bantu languages, which is considerably larger than Europe. It is the field which the explorations of Livingstone, Stanley, De Brazza. Wissmann and Holub have brought so prominently before the public, and which the powers of Christendom have taken under a partly national and partly international protectorate.

The Bantu, or Negroes south of the equator, are in some respects the most remarkable section of mankind. Separated from the rest of the world by wide oceans, virgin forests and the Sahara Desert, they have been less than any other race subject to foreign influences. No strange blood has altered their physical constitution; no foreign languages have permanently mangled the structure and the word-store of their principal forms of speech; no outside religion has seriously affected their conceptions of God, the spiritual, the animal and the natural worlds. Now they are receiving Christianity and the highest civilization the world has ever known, by methods which, however crude, inconsiderate and unjust they may appear fifty years hence, are yet far superior to all that our most sanguine forefathers could have anticipated.

In the supplement to his "Languages of Africa" Dr. Cust counts 450 African languages, with over 150 dialects. The Sudan languages number 212, and their dialects 56. The Bantu languages are estimated at 180, their dialects at 60.

With regard to the Sudan languages I will not express an opinion, as they are not in my special line; but concerning the Bantu languages, which are my special field, I am glad to be able to make the comforting statement that if we reverse the statement, and say that there are 60 languages and 180 dialects, we are much nearer the truth.

As a boy, in my native land, I studied a big book giving specimens of about 70 dialects. Now, 60 of these 70 dialects covered only a small part of three language fields, German, French and Italian. Of the African dialects, we are far from knowing all, even by name; but of the languages, we know by name a great many more than really exist.

Let me illustrate this by a few authentic examples. On the testimony of travelers and grammarians, Dr. Cust gives within the boundaries of the one Kimbundu, or Angola language, seven distinct languages. Now, these seven languages are simply dialects, and not all at that, of the language in which I am founding a Christian literature. The same process of reduction is repeated wherever sufficient material is obtained to compare the different dialects, which, until compared, seemed to deserve a separate place as languages.

Thus, in the region between Tanganyika, Bangweolo and the confluence of the Lulua and Kassai, were placed peoples with different names, the Moluas,

Page 28

the Barua, the Baluba, and the Bashilange, besides a number of others. My friend Dr. Summers labored two years at one end of this field, among the Bashilange, and gathered valuable linguistic material which he bequeathed to me. At the other end of the field, in Garenganze, another friend, the missionary Swan, also learned the language and published a vocabulary with a few chapters of a gospel. By comparing these materials collected at a distance of about 600 miles, I was surprised to find that it was the same language, and that the natives gave it the same name. At the same time I had opportunities to consult a Belgian explorer who had traversed the region comprised between those two extreme points, and also native Angolans who had accompanied him on his expedition. Their testimony confirmed my discovery. Further comparative study revealed the fact that other dialects are comprehended within the boundaries of this great Luba language, and that Luganda, at the north end of Lake Victoria, has practically the same grammatical structure.*

* See Heli Chatelain, "Bantu Notes and Vocabularies," Nos. I. and II.

During my second stay at Loanda I collected a vocabulary of U-iaka, the language of the Ma-iaka, or Ma-iakala. On my return to America I discovered, by comparison, that U-iaka was practically the same as Ki-teke, in which Dr. Sims of Stanley Pool had published a gospel and a vocabulary. Further research disclosed the fact that several other tribes, the Northern Mbamba, the Buma, the Mbete and the Tsaia speak dialects of the same language. Still further investigation into the physical appearance and the customs of these tribes showed them to be identic in all points in which they differ from their neighbors speaking other languages. These facts combined proved that between the equator and the 8° South latitude there is a cluster of tribes speaking the same language and having the same customs; forming, therefore, one great nation.*

* See "Bantu Notes," No. III.

This nation the powers assembled at Berlin in 1885 have, without knowing it, and without the nation's knowledge, divided between France, the Kongo State and Portugal, France getting the lion's share.

The discovery of this Ba-teke nation also enabled me to solve two or three historical riddles which had puzzled Africanists and still puzzle those who have not read my article on the Ma-iaka. The other Bantu nations and languages of some importance all deserve to be dwelt on at some length, but the time limit is inexorable, and I must dispose of them with a few words.

In the German Kamerun, the Dualla language is being officially taught in excellent government schools and in the stations of the Basel missions.

In French Kongo, or Gabun, the Mpongwe tribe is dying out, being superseded by the aggressive Fang. These speak a Bantu or rather semi-Bantu language. The Benga, on the sea-coast, rejoice in a considerable Christian literature, published by American Presbyterians.

The Kongo nation, with its sub-tribes, the Luangu, Buende, Sundi, Solongo, Ndembu, Hungu and Pangu, is evangelized by seven or eight Protestant missionary societies, in addition to the thrice centenarian work of the Catholic church.

Page 29

In the semi-civilized portion of Angola the natives are joining hands and blending with the Portuguese colonists, thus preparing the creation of a powerful nationality.

In the highland of Angola the Ovi-mbundu of Bailundu and Bihe bring the produce from the head streams of the mighty Kongo to the seaport of Benguella, where they barter it for cloth and rum, and also for fire-arms and powder, which enable the Ma-kioko to continue their audacious slave raids. These Ma-kioko, one of the finest looking tribes of interior Africa, with long plaited beards, have made an end of the once powerful empire of Lunda, reducing into slavery subjects of their former suzerain, the great Muatyamvo. If published vocabularies are correct, the Kioko tribe speaks practically the same language as the Ambuella, around the western headwaters of the Zambesi river, and so we would have here again one great nation and language instead of a number of unconnected tribes and dialects.

The cattle herding Ova-herero, in German South Africa, so long the victims of the periodic raids of the Hottentots, begin to breathe and raise their heads since the German troops have finally put down the Nama chieftain Witboy.

In the Upper Zambesi valley the Barotse under Lewanika seem to respond at last to the appeals of their apostles, Missionary Coillard and his colleagues.

The Zulus, the Kaffirs, the Bechuana, the Batonga, the Matebele, the Mashona and the Ba-nyai, all south of the Zambesi, are important Bantu nations, who are coming more and more into public view as their territories are invaded by the gold hunters, land-grabbers, and by the messengers of the evangel of peace and holiness.

In Portuguese Mozambique, between the Rovuma and Zambesi rivers, the great nation of the Ma-kua, including the Lomve, Metu, Ibo and Angoche sub-tribes, sees its territory gradually invaded by the whites who secure concessions from the Portuguese.

The Wa-yao, the Ma-konde, and the Manganga, around Lake Nyassa, enjoy the protection of British and German authorities against the Maviti and the Arab raiders. Scottish, English, and German-Moravian missionaries teach thousands of their young people, while the Africa Lakes Company and an Industrial Mission employ thousands of strong hands in their commercial and agricultural undertakings.

The tribes of German East Africa, among whom the Wa-Zaramo, Wa Zeguha, Wa-Sagara, Wa-Gogo, Wa Hehe, and Wa-Nyamwezi are the principal, speak all languages so closely related to that of Zanzibar, the Ki-Suahili, that the latter may finally become the literary language of all that vast region.

All readers of the daily papers and of missionary journals have become familiar with the story of U-ganda. The wonderful changes which have there taken place since 1872, when the first missionary party entered the country, and which have transformed that semi-Pagan and semi-Mohamedan country and people into a semi-Protestant and semi-Catholic Christian nation more progressive and more promising than some sections of the Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese nations, those changes, I say, are prophetic of what is about to happen among all the great Bantu nations we have passed in review.

If my opinion about the future were asked, I should not hesitate to declare

Page 30

my conviction that within one hundred years all Bantu-land will contain more than 500,000,000 inhabitants, will equal Europe in civilization, will be united in a great United States of Central Africa under a new and improved edition of our American Constitution, will both speak and write a common language, the mother-tongue of all Bantu dialects, as revived by scholars and enriched with the best developments of its daughters, and will produce master-pieces of literature, science, and art, vying with all the best that Europe and America will then be able to bring forth.

ORISHETUKEH FADUMA, B. D.

Native of the Yoruba Tribe, West Africa; Educated in Sierra Leone, London, and in Yale University

Page 31

Religious Beliefs of the Yoruba People in West

Africa

BY

ORISHATUKEH FADUMA, B. D.

West Africa

We are now at a period in the world's history when the religions of Pagan nations are studied with a view to find out whether there is any point of contact between them and the more developed forms of religion; what are their beginnings; who were the prime leaders of their religious thought; and what changes have taken place since their existence. There are observances in the ritual of Israel found in the rituals of Egypt and Chaldea, nations by far older than the Hebrews. There is something, therefore, in common with Judaism and the ethnic religions which preceded it, and by which it was surrounded. Christianity is an evolution of Judaism, yet so evolved that it becomes a new religion. Mahommedanism is a corruption of Judaism, a mingling of monotheism with Arab heathenism. Max Müller, Rawlinson, Sayce, and others have contributed not a little to the study of heathen beliefs. The observations of anthropologists and ethnologists are helping us to get at facts, and draw conclusions which otherwise would be impossible. For the present we shall be satisfied with the presentation of facts, as they are not large enough to warrant us in making large deductions.

To some of the beliefs of the Yoruba people I wish to call your attention. These people are known under four names: Yoruba, Yariba, Aku, and Oku. They live in West Central Africa, having Lagos as their seaport town. Of all West African tribes the Yoruba people are preeminently agricultural and commercial. As a commercial people, their lives are not spent in seclusion, but they come in contact with many native and foreign people. They have a native civilization which combines both the native and the Mohammedan elements. The ubiquitous Arab has somewhat modified his civil as well as religious life, but has not stamped it out of existence. They are by no means a savage, but are a semi-civilized people.

The Yoruba people, like the Athenians of old, are given to much reverence. Reverence to traditions, reverence to ancestors, reverence to the gods and spirits, is interwoven with their beliefs. If it were connected with a belief which questions before it is practiced, the Yorubas would be a highly religious people. But when reverence is merely the result of custom, then men worship they know not what, and that which ought to be sacred in religion becomes painfully supertitious. When I speak of the Yorubas as very religious, I mean that they are very superstitious. Notwithstanding this, it is important to study their system of belief, or construct one if it has not been done. The study of religion in all its forms ought to be important to the student of

Page 32

comparative religion. The genesis and development of religious belief, the stagnant condition of some religions and the apparent or real growth of others, the underlying principles which run through all and manifest themselves in what are termed the phenomena of religion, are subjects demanding a careful study. To make such a study profitable requires a sympathetic as well as an educated mind.

In studying the pagan system of the Yorubas, we shall find the three stages observed in the evolution of religion. They are Fetichism, Nature worship, and Prophecy or Divination.

1. Fetichism, the lowest, is practical, though not exclusively so. A fetich may be any object in which the god or gods convey their powers either to protect or defend the possessor. It is worn around the neck and waist, on the arms and wrists, on the ankles, or inserted into the hair. It is often concealed by an outer covering made of cloth or leather sewed tightly together. Human hair, finger nails, refuse of animals and men, precious stones, roots of trees, relics of the dead, in fact almost anything may be used. To the traveler it is a convenient vade mecum, for it is portable. It therefore takes the place of the idol and may be worn around the neck of the holder. It is a kind of a god in times of emergency. It brings good luck to the individual who wears it, and protects him from injury. It guards him against the attack of witches and the malevolence of personal and private foes. The hunter ties it near the muzzle or nipple of his gun, and it is thought to make him aim straight at his victim. What, in ordinary civilized life, would be considered a trained and skilled marksman, would be attributed to the charm or fetich. In all such cases it is some spirit whose power is felt through the charm, which is its medium. The favor or disfavor of heaven is communicated through the material medium called fetich.

2. In Nature worship, we have the image of a god made out of stone or wood. The god has the form and features of a person. It is generally an ill-shapen image, but this is probably due to the primitive state in which art is. It belongs to a high stage of civilization to produce the work of a Phidias, a Praxiteles, or a Polycletus. Yet Greek art had quite as humble beginning. Side by side with this nature worship is fetichism, so that one is at a loss to say whether the former is really an evolution from the latter. The worshipper of images has also a fetich which may be about his person even when he is in the act of worshipping his image.

3. Along with fetichism and idolatry is developed a system of priestcraft which may be at one time esoteric, and at another time exoteric. A man may make his own fetich, but when difficulties of a peculiar kind arise, the trained hand is sought. It is the man whose chief employment is to make fetiches, who knows the nature of diseases, foretells the future, and is in closer touch with the god or gods. Such a man has a powerful influence in the community; he is a physician of rare ability, a herbalist of repute, and a magician. He is sought by the high and low, consulted in family disappointments, and at the King's Court. His advice is taken, and he is dreaded by all.

The Yoruba gods are many. There is a god of war, like the Roman Mars or the Ares of the Greeks, who leads armies to victory and to whom human

Page 33

victims are offered. There is Shango, the god of thunder, whose priests are white-robed. He is like the Jupiter Tonans of the Romans. When he thunders and sends forth his lightning upon the dwellings of men, his priests are sought after to appease his wrath. There is a god who, like Ceres, controls agriculture, to whom the first fruits of the field are offered. Over the sea presides the water-god, who, like Neptune, calms the stormy seas and puts to flight the storm clouds. There are gods of the mountains, valleys and hills; gods of the market and pathways, household gods the peculiar treasures of individual families, and gods of the nation. There are several names by which the gods are known, but above them all is Olodumare, the supreme king both of gods and men, who assigns a sphere of influence to each of the local gods. He holds precisely the same relations to the gods as Jupiter held in the Roman pantheon, or Zeus in the Greek. The existence of these gods seems to be an arrangement by which the supreme God is helped to rule the country. Since the native worshipper cannot see the supreme god who is hid somewhere in the clouds, his nature demands the presence of one to whom he can appeal in cases of need, some one who can be seen by the naked eye. The necessity therefore arises for the fabrication of an object which would be a symbol of the Supreme God. It is a remarkable, though crude, expression of the people's need of an agent who shall come between them and their God, an agent who is not clothed with spirituality, but who can be seen and touched. To this visible obiect his needs are made known. Through all ethnic religions such an agent is found. In Christianity we have a solution of this need, and the truest expression in the living, the personal, visible, and tangible Christ, who is God clothed in flesh, and the mediator between God and man. Through the ages men have been groping in the dark, seeking, if haply, they may find such a Christ.

The Yoruba worships the objects of nature above him. The moon is one of them. Constant reflection on its movements sharpens his intellect. He is a good calculator. He tells his age by the number of moons he has seen. To him the moon is a harbinger of joy or sorrow; he supplicates it when it appears in its new crescent robe to avert all evils of the new month. Throughout the system of image worship, what appears first as a symbol of the God, is now confounded with, and worshipped as God. The distinction between them is lost, so that if there is a monotheism in the system, is lost in polytheism. God, as spirit, is lost and absorbed in God as matter.

Of the origin of the human race, the Yorubas have a very faint conception. The first pair sprang from that section of Yoruba country known as Iffe (Iffeh).

Of the future life they have some conception. The doctrine of the transmigration of souls is prevalent. The spirit of a good man is changed at death to some good being or animal, while that of a bad man is transformed to a ferocious animal or an evil spirit. Ancestors may be born again in the world. The children, called Abiku, that is, children who die prematurely, are said to return to life at the next birth of its mother, if at this birth the child also dies prematurely. At the death of one, messages are sent in tears and songs to dead relatives and friends. Feasts are observed and sacrifices offered to the dead. On the third day after burial, an early morning sacrifice of meal

Page 34

and oil is made at the grave of the deceased, and his spirit is supposed to eat a portion of it. On the seventh day after burial there is a feast preceded by a morning sacrifice, in which the spirit of the deceased and the spirits of ancestors partake. After this feast and sacrifice, the spirit of the deceased is supposed to leave the old home and take interest in the welfare of surviving friends.

The whole system of Yoruba worship is steeped in spirit worship. Spirits are found everywhere. They are the controllers of diseases. When a child suffers from convulsions it is because he sees a spirit which frightens him. The medicine man, therefore, washes his eyes with a solution prepared from the bark of a medicinal plant. There are spirits which exert evil influence in the world. These may be seen, and are called egbere (aygbayray). They are of diminutive stature; they leave their graves at midnight and return to them before daybreak. Sheep-riding is their delight. They are the cause of the destruction of sheep by disease. The medicine man is often called to drive them away by shooting at them, or supplying individuals who are spirit-frightened with a charm or fetich as a protection. There are also good spirits. These exert good influence in the world, and protect men from danger, and appear to them in dreams. If there is sorrow at the grave of the departed it is relieved after the seventh day, when a feast of rejoicing follows, and by the knowledge of the fact that the spirit of the deceased has gone to join those of his ancestors. There is a kind of spirit telegraphy by which the present and the future are connected.

The sacrificial system of the Yorubas has nothing peculiar. It has the same characteristics found in other systems of pagan religions. The one who offers sacrifice may be the father of the family in ordinary cases. In peculiar and trying circumstances a trained hand is sought. The medicine man is qualified by years of training for the post. The offices of doctor and sacrificer are invariably combined under the same individual. Sacrifice has a raison d'etre. It is, first of all, prophylactic. Men feel the pain of diseases, they know that evil spirits surround them and are seeking their destruction, they are aware of personal foes who are bent on their destruction; they are, therefore, compelled to sacrifice to a God and ask for his protection. The idea of communing with the gods is not a prominent one, though it is found in the system. What stands in bold relief is the feeling of deliverance and salvation from outward, not inward, evils. No one ever thinks of praying to the gods for strength to overcome personal feelings and to resist temptations. When one is surrounded by evil, or has escaped some calamity, the god is approached and his protection sought, or he is thanked for averting a calamity. Sacrifice is a prophylactic, as well as a thank-offering.

The religion of the people is one of fear and suspicion. The worshipper does not love his god, but fears him. The same mental act which is produced when the worshipper approaches his god, is also produced in children and wives when they approach their fathers and husbands. The same is produced in subjects when they approach those who are in authority. The father of a family, as well as the king or chief of the tribe, holds the same relation to his children or subjects as the god holds to the nation. It may be said that children fear rather than love their fathers, and wives submit with dread to

Page 35