The Negro Church. Report of a Social Study Made under the Direction

of Atlanta University; Together with the Proceedings of the Eighth Conference

for the Study of the Negro Problems, held at Atlanta University, May 26th, 1903:

Electronic Edition.

Dubois, W. E. B. (William Edward Burghardt), 1868-1963, Ed.

Funding from the Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library Competition supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Meredith Evans

Text encoded by

Meredith Evans and Jill Kuhn Sexton

First edition, 2001

ca. 830K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) The Negro Church: Report of a Social Study made under the Direction of Atlanta University; together with the Proceedings of the Eighth Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems, held at Atlanta University, May 26, 1903

Edited by W. E. Burghardt Du Bois

viii, 212 p.

Atlanta, Ga.

The Atlanta University Press

1903

Call number 277.3 D852n (Queens College, Charlotte, N. C.)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- African American churches.

- African Americans -- History.

- African Americans -- Religion.

- Slavery and the church -- United States -- History.

- United States -- Church history.

Revision History:

- 2001-07-27,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-02-26,

Jill Kuhn Sexton, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-01-28,

Meredith Evans

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-01-20,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcription.

NO student of the race problem, no person who would either think or speak upon it intelligently, can afford to be ignorant of the facts brought out in the Atlanta series of sociological studies of the conditions and the progress of the Negro.

The OUTLOOK, March 7, 1903.

THE NEGRO CHURCH

Report of a Social Study made under the direction of Atlanta

University;together with the Proceedings of the Eighth

Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems,

held at Atlanta University, May 26th, 1903

EDITED BY

W. E. BURGHARDT DUBOIS

CORRESPONDING SECRETARY OF THE CONFERENCE

The Atlanta University Press

Atlanta, Ga.

1903

Page ii

THE Negro Church is the only social institution of the Negroes which started in the African forest and survived slavery; under the leadership of priest or medicine man, afterward of the Christian pastor, the Church preserved in itself the remnants of African tribal life and became after emancipation the center of Negro social life. So that today the Negro population of the United States is virtually divided into church congregations which are the real units of race life.

Report of the Third Atlanta Conference, 1898.

Page iii

CONTENTS

- PREFACE . . . . . v

- BIBLIOGRAPHY . . . . . vi

- 1. Primitive Negro Religion . . . . . 1

- 2. Effect of Transplanting . . . . . 2

- 3. The Obeah Sorcery . . . . . 5

- 4. Slavery and Christianity . . . . . 6

- 5. Early Restrictions . . . . . 10

- 6. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel . . . . . 12

- 7. The Moravians, Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians . . . . . 15

- 8. The Sects and Slavery . . . . . 20

- 9. Toussaint L'Ouverture and Nat Turner . . . . . 22

- 10. Third Period of Missionary Enterprise . . . . . 26

- 11. The Earlier Churches and Preachers. (By Mr. John W. Cromwell) . . . . .30

- 12. Some Other Ante-Bellum Preachers . . . . . 35

- 13. The Negro Church in 1890 . . . . . 37

- 14. Local Studies, 1902-3 . . . . . 49

- 15. A Black Belt County, Georgia. (By the Rev. W. H. Holloway) . . . . . 57

- 16. A Town in Florida. (By Annie Marion MacLean, Ph. D.) . . . . . 64

- 17. A Southern City . . . . . 69

- 18. Virginia . . . . . 80

- 19. The Middle West, Illinois. (By Monroe N. Work, A. M., and the Editor) . . . . . 83

- 20. The Middle West, Ohio. (By R. R. Wright, Jr.) . . . . . 92

- 21. An Eastern City . . . . . 108

- 22. Present Condition of Churches--The Baptists . . . . . 111

- 23. The African Methodists . . . . . 123

- 25. The Zion Methodists . . . . . 131

- 26. The Colored Methodists . . . . . 133

- 27. The Methodists . . . . . 134

- 28. The Episcopalians . . . . . 138

- 29. The Presbyterians . . . . . 142

Page iv

- 30. The Congregationalists . . . . . 147

- 31. Summary of Negro Churches, 1900-1903 . . . . . 153

- 32. Negro Laymen and the Church . . . . . 154

- 33. Southern Whites and the Negro Church . . . . . 164

- 34. The Moral Status of Negroes . . . . . 176

- 35. Children and the Church . . . . . 185

- 36. The Training of Ministers . . . . . 190

- 37. Some Notable Preachers . . . . . 202

- 38. The Eighth Atlanta Conference . . . . . 202

- 39. Remarks of Dr. Washington Gladden . . . . . 204

- 40. Resolutions . . . . . 207

- Index . . . . . 209

Page v

PREFACE

A study of human life to-day involves a consideration of conditions of physical life, a study of various social organizations, beginning with the home, and investigations into occupations, education, religion and morality, crime and political activity. The Atlanta Cycle of studies into the Negro problem aims at exhaustive and periodic studies of all these subjects so far as they relate to the American Negro. Thus far, in the first eight years of the ten-year cycle, we have studied physical conditions of life (Reports No. 1 and No. 2), social organization (Reports No. 2 and No. 3), economic activity (Reports No. 4 and No. 7), and Education (Reports No. 5 and No. 6). This year we take up the important subject of the NEGRO CHURCH, studying the religion of Negroes and its influence on their moral habits.

Such a study could not be made exhaustive for lack of funds and organization. On the other hand, the United States government and the churches themselves have published a great deal of material and it is possible from this and limited investigations in various typical localities to make a study of some value.

This investigation bases its results on the following data:

- United States Census of 1890.

- Minutes of Conferences.

- Reports of Conventions, Societies, etc.

- Catalogues of Theological Schools.

- Two hundred and fifty special reports from pastors and officials.

- One hundred and seventy-five special reports from colored laymen.

- One hundred and seventeen special reports from heads of schools and prominent men, white and colored.

- Fifty-four special reports from Southern white persons.

- Thirteen special reports from Colored Theological Schools.

- One hundred and nine special reports from Northern Theological Schools.

- Answers from 1,300 school children.

- Local studies in--

- Richmond, Virginia. . . . . . Atlanta, Georgia.

- Chicago, Illinois. . . . . . Greene County, Ohio.

- Thomas County, Georgia. . . . . . Deland, Florida.

- General and periodical literature.

In the preparation of this report the editor begs to acknowledge his indebtedness to the several hundred persons who have so kindly answered his inquiries; to students in Atlanta University and Virginia Union University, who have made special investigations; and particularly to Professor B. F. Williams, Mr. M. N. Work, Mr. R. R. Wright, Jr.,

Page vi

and Mr. W. H. Holloway, all of whom have given valuable time and services to this work. The Rev. F. J. Grimke has kindly allowed the use of his unpublished report, made to the Hampton Conference in 1901; Mr. J. W. Cromwell has loaned us the results of his historical researches, and Dr. A. M. MacLean has given us the results of a valuable local study. The proof-reading was largely done by Mr. A. G. Dill.

Atlanta University has been conducting studies similar to this for the past seven years. The results, distributed at a nominal sum, have been widely used.

Notwithstanding this success the further prosecution of these important studies is greatly hampered by the lack of funds. With meagre appropriations for expenses, lack of clerical help and necessary apparatus, the Conference cannot cope properly with the vast field of work before it.

We appeal therefore to those who think it worth while to study this, the greatest group of social problems that has ever faced the Nation, for substantial aid and encouragement in the further prosecution of the work of the Atlanta Conference.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY OF NEGRO CHURCHES

A brief statement of the rise and progress of the testimony of the religious society of Friends against slavery and the slave-trade. Philadelphia: Joseph and William Kite. 1843.

Ernest H. Abbott. Religious life in America. A record of personal observation. New York: The Outlook, 1902 XII, 730 pp. 80.

Nehemiah Adams. A South side view of slavery. 80. Boston, 1854.

Richard Allen, first bishop of the A. M. E. Church. The life, experience and gospel labors of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen. Written by himself. Philadelphia, 1833.

Richard Allen and Jacob Tapisco. The doctrine and discipline of the A. M. E. Church. Philadelphia, 1819.

Matthew Anderson. Presbyterianism and its relation to the Negro. Philadelphia, 1897.

A statistical inquiry into the condition of the people of color of the city and districts of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, 1849, 1856 and 1859.

Samuel J. Baird. A collection of the acts, deliverances and testimonies of the Supreme Judiciary of the Presbyterian Church, from its origin in America to the present time, with notes and documents explanatory and historical, constituting a complete illustration of her polity, faith and history. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publications.

J. C. Ballagh. A history of slavery in Virginia. John Hopkins University Studies. Extra vol., No. 24. Baltimore, 1902.

Page vii

Albert Barnes. Inquiry into the scriptural views of slavery. Philadelphia, 1857.

John S. Bassett. History of slavery in North Carolina. Johns Hopkins University studies. Baltimore, 1899.

Slavery and servitude in the colony of North Carolina. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, April and May, 1896.

David Benedict. A general history of the Baptist denomination in America and other parts of the world. Boston, 1813.

Edward W. Blyden. Christianity, Islam and the Negro race. With an introduction by the Hon. Samuel Lewis. 2d edition. London: W. B. Whittingham & Co. 432 pp. 80.

George Bourne. Man-stealing and Slavery denounced by the Presbyterian and Methodist Churches. Boston: Garrison and Knapp.

Jeffrey R. Brackett. Notes on the progress of the colored people of Maryland since the war. A supplement to the Negro in Maryland, a study of the institution of slavery. Baltimore: J. Hopkins Univ., 1890. 96 pp. 80.

The Negro in Maryland. A study of the institution of slavery. Baltimore: N. Murray. (6) 268 pp. 80. (Johns Hopkins University studies in historical and political science.) Extra vol. 6.

William Burling. An address to the elders of the church upon the occasion of some Friends compelling certain persons and their posterity to serve them continually and arbitrarily, without regard to equity or right, not heeding whether they give them anything near so much as their labor deserveth. 1718. In Lay, All Slave Keepers Apostates. pp. 6-10.

Rev. Dr. R. F. Campbell. The race problem in the South. Pamphlet, 1899.

W. E. Burghardt DuBois. 1900. The religion of the American Negro. New World, vol. 9 (Dec. 1900) 614-625.

The Philadelphia Negro. A Social Study. Philadelphia, 1899: Ginn & Co.

The Negroes of Farmville, Va. 38 pp. Bulletin U.S. Department of Labor, Jan. 1898.

Some efforts of American Negroes for their own social betterment. Report of an investigation under the direction of Atlanta University, together with the proceedings of the third Conference for the study of the Negro problems, held at Atlanta University, May 25-26, 1898. Atlanta, Ga. (Atlanta University, 1898. 66 pp.)

The Souls of Black Folk. Chicago, 1903.

William Douglass. Sermons preached in the African Protestant Episcopal Church of St. Thomas. Philadelphia, 1854.

Annals of St. Thomas's Church. Philadelphia, 1862.

Bryan Edwards. History, civil and commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies. London, 1807.

Friends. A brief testimony of the progress of the Friends against slavery and the slave-trade. 1671-1787. Philadelphia, 1843.

William Goodell. The American slave code in theory and practice. Judiciary decisions and illustrative facts. New York, 1452.

H. Gregoire. Enquiry concerning the intellectual and moral faculties, etc., of Negroes. Brooklyn, 1810.

L. M. Hagood. The Colored Man in the Methodist Episcopal Church. Cincinnati.

Bishop J. W. Hood. One Hundred Years of the A. M. E. Zion Church.

Edward Ingle. The Negro in the District of Columbia. Johns Hopkins University studies. Vol. XI. Baltimore, 1893.

Samuel M. Janney. History of the religious society of Friends. Philadelphia, 1859-1867.

Chas. C. Jones. The religious instruction of the Negroes in the United States. Savannah, 1842.

Absalom Jones. A Thanksgiving sermon on account of the abolition of the African slave-trade. Philadelphia, 1808.

Page viii

Robert Jones. Fifty years in the Lombard Street Central Presbyterian Church. Philadelphia, 1894. 170 pp.

Fanny Kemble. A journal of a residence on a Georgia plantation. New York, 1863.

Walter Laidlow, editor. The Federation of Churches and Christian Workers in New York City. New York, 1896-1897.

Lucius C. Matlack. The history of American slavery and Methodism from 1789-1849. New York, 1849.

Holland McTyeire. A history of Methodism, comprising a view of the rise of this revival of spiritual religion in the first half of the eighteenth century. Nashville, Tenn.: Southern Methodist Publishing House, 1887.

Minutes, Annual Conferences, A. M. E. Church.

Minutes, Annual Conferences, C. M. E. Church.

Minutes, Annual Conferences, M. E. Church.

Minutes, Annual Conferences, A. M. E. Z. Church.

Minutes, General Conferences, A. M. E. Church.

Minutes, General Conferences, C. M. E. Church.

Minutes, General Conferences, M. E. Church.

Minutes, General Conferences, A. M. E. Z. Church.

Minutes, National Baptist Convention.

Edward Needles. Ten years' progress or a comparison of the state and condition of the colored people in the city and county of Philadelphia from 1837-1847. Philadelphia, 1849.

Daniel A. Payne. History of the A. M. E. Church. Nashville, 1891.

I. Garland Penn and J. W. E. Bowen. The United Negro; his problems and his progress. Containing the addresses and proceedings of the Negro Young People's Christian and Educational Congress, held August 6-11, 1902. Atlanta, Ga.: D. E. Luther Publishing Co., 1902, XXX, 600 pp. Plates, portraits. 12o.

Reports, Freedmen's Aid Society, Presbyterian Church.

Robert R. Semple. History of the rise and progress of Baptists in Virginia. Richmond, 1810.

William J. Simmons. Men of Mark, Eminent, Progressive and Rising. Cleveland, Ohio.

Slavery as it is; the testimony of a thousand witnesses. Publication of Anti-Slavery Society. New York, 1839.

George Smith. History of Wesleyan Methodism. London, 1862.

David Spencer. Early Baptists of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, 1877.

William B. Sprague. Annals of the American Pulpit. New York, 1858.

Benjamin T. Tanner. An outline of history and government for A. M. E. Churchman. Philadelphia, 1884.

An apology for African Methodism. Baltimore, 1867.

H. M. Turner. Methodist Polity. Philadelphia.

United States Census, 1890. Churches.

A. W. Wayman. My Recollections of A. M. E. Ministers. Philadelphia, 1883.

S. D. Weld. American Slavery as it is: testimony of thousands of witnesses. New York, 1839.

Stephen B. Weeks. Anti-slavery sentiment in the South. Washington, D. C., 1898. Southern Quakers and Slavery. Baltimore, 1896.

George W. Williams. History of the Negro race in America. New York, 1883.

White. The African Preacher.

Page 1

THE NEGRO CHURCH

1. Primitive Negro Religion.

The prominent characteristic of primitive Negro religion is Nature worship with the accompanying strong belief in sorcery. There is a theistic tendency: "Almost all tribes believe in some supreme god without always worshiping him, generally a heaven and rain god; sometimes, as among the Cameroons and in Dahomey, a sun-god. But the most widely-spread worship among Negroes and Negroids, from west to northeast and south to Loango, is that of the moon, combined with a great veneration of the cow."*

* Professor C. P. Thiele, in Encyclopedia Britannica, 9th ed., XX, p. 362.

The slave trade so mingled and demoralized the west coast of Africa for four hundred years that it is difficult to-day to find there definite remains of any great religious system. Ellis tells us of the spirit belief of the Ewne people; they believe that men and all Nature have the indwelling "Kra," which is immortal. That the man himself after death may exist as a ghost, which is often conceived of as departed from the "Kra," a shadowy continuing of the man. So Bryce, speaking of the Kaffirs of South Africa, a branch of the great Bantu tribe, says:

"To the Kaffirs, as to the most savage races, the world was full of spirits--spirits of the rivers, the mountains, and the woods. Most important were the ghosts of the dead, who had power to injure or help the living, and who were, therefore, propitiated by offerings at stated periods, as well as on occasions when their aid was especially desired. This kind of worship, the worship once most generally diffused throughout the world, and which held its ground among the Greeks and Italians in the most flourishing period of ancient civilization, as it does in China and Japan to-day, was, and is, virtually the religion of the Kaffirs."

The supreme being of the Bantus is the dimly conceived Molimo, the Unseen, who typifies vaguely the unknown powers of nature or of the sky. Among some tribes the worship of such higher spirits has banished fetichism and belief in witchcraft, but among most of the African tribes the sudden and violent changes in government and social organization have tended to overthrow the larger religious conceptions and leave fetichism and witchcraft supreme. This is particularly true on the west coast among the spawn of the slave traders.

There can be no reasonable doubt, however, but that the scattered remains of religious systems in Africa to-day among the Negro tribes

Page 2

are survivals of the religious ideas upon which the Egyptian religion was based, and that the basis of the religion of Egypt was "of a purely Negritian character."*

* Encyclopedia Britannica, 9th ed., XX, p. 362.

The early Christian church had an Exarchate of fifty-two dioceses in Northern Africa, but it probably seldom came in contact with purely Negro tribes on account of the Sahara. The hundred dioceses of the patriarchate of Alexandria, on the other hand, embraced Libya, Pentapolis, Egypt, and Abyssinia, and had a large number of Negroid members. In Western Africa, after the voyage of Da Gama, there were several kingdoms of Negroes nominally Catholic, and the church claimed several hundred thousand communicants. These were on the slave coast and on the eastern coast.

Mohammedanism entered Africa in the seventh and eighth centuries and has since that time conquered nearly all Northern Africa, the Soudan, and made inroads into the populations of the west coast. "The introduction of Islam into Central and West Africa has been the most important if not the sole preservation against the desolations of the slave-trade,"*

* Blyden, Meth. Quar. Review,Jan. 1871. See also his Christianity, Islam and the Negro Race.

and especially is it preserving the natives against the desolations of Christian rum.

2. Effect of Transplanting.

It ought not to be forgotten that each Negro slave brought to America during the four centuries of the African slave trade was taken from definite and long-formed habits of social, political, and religious life. These ideas were not the highest, measured by modern standards, but they were far from the lowest, measured by the standards of primitive man. The unit of African tribal organization was the clan or family of families ruled by the patriarch or his strongest successor; these clans were united into tribes ruled by hereditary or elected chiefs, and some tribes were more or less loosely federated into kingdoms. The families were polygamous, communistic groups, with one father and as many mothers as his wealth and station permitted; the family lived together in a cluster of homes, or sometimes a whole clan or village in a long, low apartment house. In such clans the idea of private property was but imperfectly developed, and never included land. The main mass of visible wealth belonged to the family and clan rather than to the individual; only in the matter of weapons and ornaments was exclusive private ownership generally recognized.

The government, vested in fathers and chiefs, varied in different tribes from absolute despotisms to limited monarchies, almost republican. Viewing the Basuto National Assembly in South Africa, Mr. Bryce recently wrote:

Page 3

"The resemblance to the primary assemblies of the early peoples of Europe is close enough to add another to the arguments which discredit the theory that there is any such thing as an 'Aryan Type' of institutions."*

* Impressions of S. Africa, 3rd ed., p. 352.

In administering justice and protecting women these governments were as effective as most primitive organizations.

The power of religion was represented by the priest or medicine man. Aided by an unfaltering faith, natural sharpness and some rude knowledge of medicine, and supported by the vague sanctions of a half-seen world peopled by spirits, good and evil, the African priest wielded a power second only to that of the chief, and often superior to it. In some tribes the African priesthood was organized and something like systematic religious institutions emerged. But the central fact of African life, political, social and religious, is its failure to integrate--to unite and systematize itself in some conquering whole which should dominate the wayward parts. This is the central problem of civilization, and while there have arisen from time to time in Africa conquering kingdoms, and some consolidation of power in religion, it has been continually overthrown before it was strong enough to maintain itself independently. What have been the causes of this? They have been threefold: the physical peculiarities of Africa, the character of external conquest, and the slave-trade--the "heart disease of Africa." The physical peculiarities of the land shut out largely the influence of foreign civilization and religion and made human organization a difficult fight for survival against heat and disease; foreign conquest took the form of sudden incursions, causing vast migrations and uprooting of institutions and beliefs, or of colonizations of strong, hostile and alien races, and finally for four centuries the slave-trade fed on Africa, and peaceful evolution in political organization or religious belief was impossible.

Especially did the slave-trade ruin religious evolution on the west coast; the ancient kingdoms were overthrown and changed, tribes and nations mixed and demoralized, and a perfect chaos of ideas left. Here it was that animal worship, fetichism and belief in sorcery and witchcraft strengthened their sway and gained wider currency than ever.

The first social innovation that followed the transplanting of the Negro was the substitution of the West Indian plantation for the tribal and clan life of Africa. The real significance of this change will not appear at first glance. The despotic political power of the chief was now vested in the white master; the clan had lost its ties of blood relationship and became simply the aggregation of individuals on a plot of ground, with common rules and customs, common dwellings, and a certain communism in property. The two greatest changes, however, were, first, the enforcement of severe and unremitted toil, and, second,

Page 4

the establishment of a new polygamy--a new family life. These social innovations were introduced with much difficulty and met determined resistance on the part of the slaves, especially when there was community of blood and language. Gradually, however, superior force and organized methods prevailed, and the plantation became the unit of a new development. The enforcement of continual toil was not the most revolutionary change which the plantation introduced. Where this enforced labor did not descend to barbarism and slow murder, it was not bad discipline; the African had the natural indolence of a tropical nature which had never felt the necessity of work; his first great awakening came with hard labor, and a pity it was, not that he worked, but that voluntary labor on his part was not from the first encouraged and rewarded. The vast and overshadowing change that the plantation system introduced was the change in the status of women--the new polygamy. This new polygamy had all the evils and not one of the safeguards of the African prototype. The African system was a complete protection for girls, and a strong protection for wives against everything but the tyranny of the husband; the plantation polygamy left the chastity of Negro women absolutely unprotected in law, and practically little guarded in custom. The number of wives of a native African was limited and limited very effectually by the number of cattle he could command or his prowess in war. The number of wives of a West India slave was limited chiefly by his lust and cunning. The black females, were they wives or growing girls, were the legitimate prey of the men, and on this system there was one, and only one, safeguard, the character of the master of the plantation. Where the master was himself lewd and avaricious the degradation of the women was complete. Where, on the other hand, the plantation system reached its best development, as in Virginia, there was a fair approximation of a monogamic marriage system among the slaves; and yet even here, on the best conducted plantations, the protection of Negro women was but imperfect; the seduction of girls was frequent, and seldom did an illegitimate child bring shame, or an adulterous wife punishment to the Negro quarters.

And this was inevitable, because on the plantation the private home, as a self-protective, independent unit, did not exist. That powerful institution, the polygamous African home, was almost completely destroyed and in its place in America arose sexual promiscuity, a weak community life, with common dwelling, meals and child-nurseries. The internal slave trade tended to further weaken natural ties. A small number of favored house servants and artisans were raised above this--had their private homes, came in contact with the culture of the master class, and assimilated much of American civilization. Nevertheless, broadly speaking, the greatest social effect of American slavery was to substitute for the polygamous Negro home a new polygamy less guarded, less effective, and less civilized.

Page 5

At first sight it would seem that slavery completely destroyed every vestige of spontaneous social movement among the Negroes; the home had deteriorated; political authority and economic initiative was in the hands of the masters, property, as a social institution, did not exist on the plantation, and, indeed, it is usually assumed by historians and sociologists that every vestige of internal development disappeared, leaving the slaves no means of expression for their common life, thought, and striving. This is not strictly true; the vast power of the priest in the African state has already been noted; his realm alone--the province of religion and medicine--remained largely unaffected by the plantation system in many important particulars. The Negro priest, therefore, early became an important figure on the plantation and found his function as the interpreter of the supernatural, the comforter of the sorrowing, and as the one who expressed, rudely, but picturesquely, the longing and disappointment and resentment of a stolen people. From such beginnings arose and spread with marvellous rapidity the Negro Church, the first distinctively Negro American social institution. It was not at first by any means a Christian Church, but a mere adaptation of those heathen rites which we roughly designate by the term Obe Worship, or "Voodoism." Association and missionary effort soon gave these rites a veneer of Christianity, and gradually, after two centuries, the Church became Christian, with a simple Calvinistic creed, but with many of the old customs still clinging to the services. It is this historic fact that the Negro Church of to-day bases itself upon the sole surviving social institution of the African fatherland, that accounts for its extraordinary growth and vitality. We easily forget that in the United States to-day there is a Church organization for every sixty Negro families. This institution, therefore, naturally assumed many functions which the other harshly suppressed social organs had to surrender; the Church became the center of amusements, of what little spontaneous economic activity remained, of education, and of all social intercourse.

3. The Obeah Sorcery.

Let us now trace this development historically. The slaves arrived with a strong tendency to Nature worship and a belief in witchcraft common to all. Beside this some had more or less vague ideas of a supreme being and higher religious ideas, while a few were Mohammedans, and fewer Christians. Some actual priests were transported and others assumed the functions of priests, and soon a degraded form of African religion and witchcraft appeared in the West Indies, which was known as Obi,*

* Obi (Obeah, Obiah or Obia), is the adjective: Obe or Obi, the noun. It is of African origin, probably connected with Egyptian Ob, Aub, or Obron, meaning serpent. Moses forbids Israelites ever to consult the demon Ob, i. e., "Charmer, Wizard." The Witch of Endor is called Oub or Ob. Onbaous is the name of the Baselisk or Royal Serpent, emblem of the Sun, and, according to Horus Appollo, "ancient oracular Deity of Africa."--Edwards, West Indies, II, pp. 106-119.

or sorcery. The French Creoles

Page 6

called it "Waldensian" (Vaudois), because of the witchcraft charged against the wretched followers of Peter Waldo, whence comes the dialect name of Voodoo or Hoodoo, used in the United States. Edwards gives as sensible an account of this often exaggerated form of witchcraft and medicine as one can get:

"As far as we are able to decide from our own experience and information when we lived in the island, and from the current testimony of all the Negroes we have ever conversed with on the subject, the professors of Obi are, and always were, natives of Africa, and none other; and they have brought the science with them from thence to Jamaica, where it is so universally practiced, that we believe there are few of the large estates possessing native Africans, which have not one or more of them. The oldest and most crafty are those who usually attract the greatest devotion and confidence; those whose hoary heads, and a somewhat peculiarly harsh and forbidding aspect, together with some skill in plants of the medical and poisonous species, have qualified them for successful imposition upon the weak and credulous. The Negroes in general, whether Africans or Creoles, revere, consult, and fear them. To these oracles they resort, and with the most implicit faith, upon all occasions, whether for the cure of disorders, the obtaining revenge for injuries or insults, the conciliating of favor, the discovery and punishment of the thief or adulterer, and the prediction of future events. The trade which these imposters carry on is extremely lucrative; they manufacture and sell their Obeis adapted to the different cases and at different prices. A veil of mystery is studiously thrown over their incantations, to which the midnight hours are allotted, and every precaution is taken to conceal them from the knowledge and discovery of the White people."*

* Edwards: West Indies, II, 108-109.

At first the system was undoubtedly African and part of some more or less general religious system. It finally degenerated into mere imposture. There would seem to have been some traces of blood sacrifice and worship of the Moon, but unfortunately those who have written on the subject have not been serious students of a curious human phenomenon, but rather persons apparently unable to understand why a transplanted slave should cling to heathen rites.

4. Slavery and Christianity.

The most obvious reason for the spread of witchcraft and persistence of heathen rites among Negro slaves was the fact that at first no effort was made by masters to offer them anything better. The reason for this was the widespread idea that it was contrary to law to hold Christians as slaves. One can realize the weight of this if we remember that the Diet of Worms and Sir John Hawkins' voyages were but a generation apart. From the time of the Crusades to the Lutheran revolt the feeling of Christian brotherhood had been growing, and it was pretty well established by the end of the sixteenth century that it was illegal and irreligious for Christians to hold each other as slaves for life. This did not mean any widespread abhorrence of forced labor from serfs or apprentices and it was particularly

Page 7

linked with the idea that the enslavement of the heathen was meritorious, since it punished their blasphemy on the one hand and gave them a chance for conversion on the other.

When, therefore, the slave-trade from Africa began it met only feeble opposition here and there. That opposition was in nearly all cases stilled when it was continually stated that the slave-trade was simply a method of converting the heathen to Christianity. The corrollary that the conscience of Europe immediately drew was that after conversion the Negro slave was to become in all essential respects like other servants and laborers, that is bound to toil, perhaps, under general regulations, but personally free with recognized rights and duties.

Most colonists believed that this was not only actually right, but according to English law. And while they early began to combat the idea they continually doubted the legality of their action in English courts. In 1635 we find the authorities of Providence islands condemning Mr. Reshworth's behavior concerning the Negroes who ran away, as indiscreet, "arising, as it seems, from a groundless opinion that Christians may not lawfully keep such persons in a state of servitude during their strangeness from Christianity," and injurious to themselves.*

*Sainsbury: Calendar of State Papers, 1574-1660, ¶ 262.

The colonies early began cautiously to declare that certain distinctions lay between "Christian" inhabitants and slaves, whether they were Christians or not. Maryland, for instance, proposed a law, in 1638, which failed of passage. It was:

"For the liberties of the people" and declared "all Christian inhabitants (slaves only excepted) to have and enjoy all such rights, liberties, immunities, privileges and free customs, within this province, as any natural born subject of England hath or ought to have or enjoy in the realm of England, saving in such cases as the same are or may be altered or changed by the laws and ordinances of this province."*

*Williams' History of the Negro Race, I, 239.

The question arose in different form in Massachusetts when it was enacted that only church members could vote. If Negroes joined the church, would they become free voters of the commonwealth? It seemed hardly possible.*

*IbidI, 190.

Nevertheless, up to 1660 or thereabouts it seemed accepted in most colonies and in the English West Indies that baptism into a Christian church would free a Negro slave. Massachusetts first apparently attacked this idea by enacting in 1641 that slavery should be confined to captives in just wars "and such strangers as willingly sell themselves or are sold to us," meaning by "strangers" apparently heathen, but saying nothing as to the effect of conversion. Connecticut adopted similar legislation in 1650 and Virginia declared

Page 8

in 1661 that Negroes "are incapable of making satisfaction" for time lost in running away by lengthening their time of service, thus implying that they were slaves for life, and Maryland declared flatly in 1663 that Negro slaves should serve "durante vita." In Barbadoes the Council presented, in 1663, an act to the Assembly recommending the christening of Negro children and the instruction of all adult Negroes to the several ministers of the place.

At the same time in the ready-made Duke of York's laws sent over to the new colony of New York in 1664 the old idea seems to prevail:

"No Christian shall be kept in bondslavery, villenage, or captivity, except such who shall be judged thereunto by authority, or such as willingly have sold or shall sell themselves, in which case a record of such servitude shall be entered in the Court of Sessions held for that jurisdiction where such masters shall inhabit, provided that nothing in the law contained shall be to the prejudice of master or dame who have or shall by any indenture or covenant take apprentices for term of years, or other servants for term of years or life."*

It was not until 1667 that Virginia finally plucked up courage to attack the issue squarely and declared by law:

"Baptisme doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom, in order that diverse masters freed from this doubt may more carefully endeavor the propagation of Christianity."*

Following this Virginia took three further decisive steps in 1670, 1682, and 1705. First she declared that only slaves imported from Christian lands should be free. Next she excepted Negroes and mulattoes from even this restriction unless they were born of Christians and were Christians when taken in slavery. Finally only personal Christianity in Africa or actual freedom in a Christian country excepted a Virginia Negro slave from life-long slavery.*

This changing attitude of Christians toward Negroes was reflected in Locke's Fundamental Constitutions for Carolina in 1670, one article of which said:

"Since charity obliges us to wish well to the souls of all men, and religion ought to alter nothing in any man's civil estate or right, it shall be lawful for slaves as well as others to enter themselves and to be of what church or profession any of them shall think best, and thereof be as fully members as any freeman. But yet no slave shall hereby be exempted from that civil dominion his master hath over him, but be in all things in the same state and condition he was in before."*

* Bassett: Slavery in Colony of N. C., p. 41.

So much did this please the Carolinians that it was one of the few articles re-enacted in the Constitution of 1698. In 1671 Maryland was moved to pass "An Act for the Encouraging of the Importation of Negroes and Slaves." This law declared that conversion or the holy

Page 9

sacrament of baptism should not be taken to give manumission in any way to slaves or their issue who had become Christians or had been or should be baptized either before or after their importation to Maryland, "any opinion to the contrary notwithstanding."

It was explained that this law was passed because "several of the good people of this province have been discouraged from importing or purchasing therein any Negroes or other slaves; and such as have imported or purchased any there have neglected--to the great displeasure of Almighty God and the prejudice of the souls of those poor people--to instruct them in the Christian faith, and to permit them to receive the holy sacrament of baptism for the remission of their sin, under the mistaken and ungrounded apprehension that their slaves by becoming Christians would thereby be freed."*

* Brackett, p. 29.

This law was re-enacted in 1692 and 1715.

It is clear from these citations that in the seventeenth century not only was there little missionary effort to convert Negro slaves, but that there was on the contrary positive refusal to let slaves be converted, and that this refusal was one incentive to explicit statements of the doctrine of perpetual slavery for Negroes. The French Code Noir of 1685 made baptism and religious instruction of Negroes obligatory. We find no such legislation in English colonies. On the contrary, the principal Secretary of State is informed in 1670 that in Jamaica the number of tippling houses has greatly increased, and many planters are ruined by drink. "So interests decrease, Negroes and slaves increase. There is much cruelty, oppression, rape, whoredoms, and adulteries."*

* Sainsbury's Calendars, 1669-74, ¶ 138.

In Massachusetts John Eliot and Cotton Mather both are much concerned that "so little care was taken of their (the Negroes') precious and immortal souls," which were left to "a destroying ignorance merely for fear of thereby losing the benefit of their vassalage."

So throughout the colonies it is reported in 1678 that masters, "out of covetousness," are refusing to allow their slaves to be baptized; and in 1700 there is an earnest plea in Massachusetts for religious instruction of Negroes since it is "notorious" that masters discourage the "poor creatures" from baptism. In 1709 a Carolina clergyman writes to the secretary of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in England that only a few of 200 or more Negroes in his community were taught Christianity, but were not allowed to be baptized. Another minister writes, a little later, that he prevailed upon a master after much importuning to allow three Negroes to be baptized. In North Carolina in 1709 a clergyman of the Established Church complains that masters will not allow their slaves to be baptized for fear that a Christian slave is by law free. A few were instructed in religion, but not baptized. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel combated

Page 10

this notion vigorously. Later, in 1732, Bishop Berkeley reports that few Negroes have been received into the church.*

* Brackett, p. 31. Bassett: Slavery in Colony of N. C., p. 46.

This state of affairs led to further laws, and the instructions to some of the royal Governors contain a clause ordering them to "find out the best means to facilitate and encourage the conversion of Negroes and Indians to the Christian religion."*

* Instructions of Lord Cornbury of Va., 702. Williams I, 140.

New York hastened to join the States which sought to reassure masters, declaring in 1706:

"Whereas, Divers of her Majesty's good subjects, inhabitants of this colony, now are, and have been willing that such Negroes, Indian and Mulatto slaves, who belong to them, and desire the same, should be baptized, but are deterred and hindered therefrom by reason of a groundless opinion that hath spread itself in this colony, that by the baptizing of such Negro, Indian or Mulatto slaves, they would become free, and ought to be set at liberty. In order, therefore, to put an end to all such doubts and scruples as have, or hereafter any time may arise about the same:

"Be it enacted, etc., That the baptizing of a Negro, Indian, or Mullatto slave shall not be any cause or reason for the setting them, or any of them, at liberty. "And be it, etc., That all and every Negro, Indian, Mullatto and Mestee bastard child and children, who is, are, and shall be born of any Negro, Indian, or Mestee, shall follow the state and condition of the mother and be esteemed, reputed, taken and adjudged a slave and slaves to all intents and purposes whatsoever."*

In 1729 an appeal from several colonies was made to England on the subject in order to increase the conversion of blacks. The Crown Attorney and Solicitor General replied that baptism in no way changed the slave's status.§

5. Early Restrictions.

"In the year 1624, a few years after the arrival of the first slave ship at Jamestown, Va., a Negro child was baptized and called William, and from that time on in almost all, if not all, the oldest churches in the South, the names of Negroes baptized into the church of God can be found upon the registers."¶

¶ Archdeacon J. H. M. Pollard.

It was easy to make such cases an argument for more slaves. James Habersham, the Georgia companion of the Methodist Whitefield, said about 1730:

"I once thought it was unlawful to keep Negro slaves, but I am now induced to think God may have a higher end in permitting them to be brought to this Christian country, than merely to support their masters. Many of the poor slaves in America have already been made freemen of the heavenly Jerusalem and possibly a time may come when many thousands may embrace the gospel, and thereby be brought into the glorious liberty of the children of God. These, and other considerations, appear to plead strongly for a limited use of Negroes; for, while we can buy provisions in Carolina cheaper than we can here, no one will be induced to plant much."

Page 11

In other cases there were curious attempts to blend religion and expediency, as for instance, in 1710, when a Massachusetts clergyman evolved a marriage ceremony for Negroes in which the bride solemnly promised to cleave to her husband "so long as God in his Providence" and the slave-trade let them live together!

The gradual increase of these Negro Christians, however, brought peculiar problems. Clergymen, despite the law, were reproached for taking Negroes into the church and still allowing them to be held as slaves. On the other hand it was not easy to know how to deal with the black church member after he was admitted. He must either be made a subordinate member of a white church or a member of a Negro church under the general supervision of whites. As the efforts of missionaries, like Dr. Bray, slowly increased the number of converts, both these systems were adopted. But the black congregations here and there soon aroused the suspicion and fear of the masters, and as early as 1715 North Carolina passed an act which declared:

"That if any master or owner of Negroes or slaves, or any other person or persons whatsoever in the government, shall permit or suffer any Negro or Negroes to build on their, or either of their, lands, or any part thereof, any house under pretense of a meeting-house upon account of worship, or upon any pretense whatsoever, and shall not suppress and hinder them, he, she, or they so offending, shall, for every default, forfeit and pay fifty pounds, one-half toward defraying the contingent charges of the government, the other to him or them that shall sue for the same."*

* Lapsed in 1741. See Laws of 1715, Ch. 46, Sec. 18; Bassett: Colony, p. 50.

This made Negro members of white churches a necessity in this colony, and there was the same tendency in other colonies. "Maryland passed a law in 1723 to suppress tumultuous meetings of slaves on Sabbath and other holy days," a measure primarily for good order, but also tending to curb independent religious meetings among Negroes. In 1800 complaints of Negro meetings were heard. Georgia in 1770 forbade slaves "to assemble on pretense of feasting," etc., and "any constable," on direction of a justice, is commanded to disperse any assembly or meeting of slaves "which may disturb the peace or endanger the safety of his Majesty's subjects; and every slave which may be found at such meeting, as aforesaid, shall and may, by order of such justice, immediately be corrected, without trial, by receiving on the bare back twenty-five stripes, with a whip, switch, or cowskin," etc.*

* Prince's Digest, 447.

In 1792 in a Georgia act "to protect religious societies in the exercise of their religious duties," punishment was provided for persons disturbing white congregations, but "no congregation or company of Negroes shall upon pretense of divine worship assemble themselves" contrary to the act of 1770. Whether or not such acts tended to curb the really religious meetings of the slaves or not it is not easy to know. Probably they did, although at the same time there was probably much disorder and

Page 12

turmoil among slaves, which sought to cloak itself under the name of the church. This was natural, for such assemblies were the only surviving African organizations, and they epitomized all there was in slave life outside of forced toil.

It gradually became true, as Brackett says, that "any privileges of church-going which slaves might enjoy depended much, as with children, on the disposition of the masters."*

* Brackett, pp. 108-110.

In some colonies, like North Carolina, masters continued indifferent throughout the larger part of the eighteenth century. In New Hanover county of that state out of a thousand whites and two thousand slaves, 307 masters were baptized in 1742, but only nine slaves. The English are told of continued indifference in Massachusetts, the Connectient General Assembly is asked in 1738 if masters ought not to promise to train slaves as Christians, and instructions are repeatedly given to Governors on the matter, with but small results.*

* Bassett: Colony, p. 49: Williams I, p. 188.

6. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.*

* This section is taken largely from Charles Colcock Jones' "The Religious Instruction of the Negroes," Savannah, 1842.

"The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts" was incorporated under William III, on the 16th day of June, 1701, and the first meeting of the society under its charter was the 27th of June of the same year. Thomas Laud, Bishop of Canterbury, Primate and Metropolitan of all England, was appointed by his majesty the first president.

This society was formed with the view, primarily, of supplying the destitution of religious institutions and privileges among the inhabitants of the North American colonies, members of the established church of England; and, secondarily, of extending the gospel to the Indians and Negroes. The society entered upon its duties with zeal, being patronized by the king and all the dignitaries of the Church of England.

They instituted inquiries into the religious condition of all the colonies, responded to "by the governors and persons of the best note," (with special reference to Episcopacy), and they perceived that their work "consisted of three great branches: the care and instruction of our people settled in the colonies; the conversion of the Indian savages, and the conversion of the Negroes." Before appointing missionaries they sent out a traveling preacher, the Rev. George Keith (an itinerant missionary), who associated with himself the Rev. John Talbot. Mr. Keith preached between North Carolina and Piscataqua river in New England, a tract above eight hundred miles in length, and completed his mission in two years, and returned and reported his labors to the society.

The annual meetings of this society were regularly held from 1702 to 1819 and 118 sermons preached before it by bishops of the Church of

Page 13

England, a large number of them distinguished for piety, learning, and zeal.

In June, 1702, the Rev. Samuel Thomas, the first missionary, was sent to the colony of South Carolina. The society designed he should attempt the conversion of the Yammosee Indians; but the governor, Sir Nathaniel Johnson, appointed him to the care of the people settled on the three branches of Cooper river, making Goose creek his residence. He reported his labors to the society and said "that he had taken much pains also in instructing the Negroes, and learned twenty of them to read." He died in October, 1706. He was succeeded by a number of missionaries.

"In 1709 Mr. Huddlestone was appointed school-master in New York city. He taught forty poor children out of the society funds, and publicly catechised in the steeple of Trinity Church every Sunday in the afternoon, 'not only his own scholars, but also the children, servants and slaves of the inhabitants, and above one hundred usually attended him.'

"The society established also a catechising school in New York city in 1704, in which there were computed to be about 1,500 Negro and Indian slaves. The society hoped their example would be generally followed in the colonies. Mr. Elias Neau, a French Protestant, was appointed catechist, who was very zealous in his duty, and many Negroes were instructed and baptized.

"In 1712 the Negroes in New York conspired to destroy all the English, which greatly discouraged the work of their instruction. The conspiracy was defeated, and many Negroes taken and executed. Mr. Neau's school was blamed as the main occasion of the barbarous plot; two of Mr. Neau's students were charged with the plot; one was cleared and the other was proved to have been in the conspiracy, but guiltless of his master's murder. 'Upon full trial the guilty Negroes were found to be such as never came to Mr. Neau's school; and, what is very observable, the persons whose Negroes were found most guilty were such as were the declared opposers of making them Christians.' In a short time the cry against the instruction of the Negroes subsided: the governor visited and recommended the school. Mr. Neau died in 1722, much regretted by all who knew his labors." He was succeeded by Rev. Mr. Wetmore, who afterwards was appointed missionary to Rye in New York. After his removal "the rector, church wardens, and vestry of Trinity Church in New York city" requested another catechist, "there being about 1,400 Negro and Indian slaves, a considerable number of whom had been instructed in the principles of Christianity by the late Mr. Neau, and had received baptism and were communicants in their church. The society complied with this request and sent over Rev. Mr. Colgan in 1726, who conducted the school with success."*

* Cf. Atlanta University Publications, No. 6.

Page 14

The society looked upon the instruction and conversion of the Negroes as a principal branch of its care, esteeming it a great reproach to the Christian name that so many thousands of persons should continue in the same state of pagan darkness under a Christian government and living in Christian families as they lay under formerly in their own heathen countries. The society immediately from its first institution strove to promote their conversion, and inasmuch as its income would not enable it to send numbers of catechists sufficient to instruct the Negroes, yet it resolved to do its utmost, and at least to give this work the mark of its highest approbation. Its officers wrote, therefore, to all their missionaries that they should use their best endeavors at proper times to instruct the Negroes, and should especially take occasion to recommend zealously to the masters to order their slaves, at convenient times, to come to them that they might be instructed.

The history of the society goes on to say: "It is a matter of commendation to the clergy that they have done thus much in so great and difficult a work. But, alas! what is the instruction of a few hundreds in several years with respect to the many thousands uninstructed, unconverted, living, dying, utter pagans. It must be confessed what hath been done is as nothing with regard to what a true Christian would hope to see effected." After stating several difficulties in respect to the religious instruction of the Negroes, it is said: "But the greatest obstruction is the masters themselves do not consider enough the obligation which lies upon them to have their slaves instructed." And in another place, "the society have always been sensible the most effectual way to convert the Negroes was by engaging their masters to countenance and promote their conversion." The bishop of St. Asaph, Dr. Fleetwood, preached a sermon before the society in the year 1711, setting forth the duty of instructing the Negroes in the Christian religion. The society thought this so useful a discourse that they printed and dispersed abroad in the plantations great numbers of that sermon in the same year; and in the year 1725 reprinted the same and dispersed again great numbers. The bishop of London, Dr. Gibson, (to whom the care of plantations abroad, as to religious affairs, was committed,) became a second advocate for the conversion of Negroes, and wrote two letters on the subject. The first in 1727, "addressed to masters and mistresses of families in the English plantations abroad, exhorting them to encourage and promote the instruction of their Negroes in the Christian faith. The second in the same year, addressed to the missionaries there, directing them to distribute the said letter, and exhorting them to give their assistance towards the instruction of the Negroes within their several parishes."

The society were persuaded this was the true method to remove the great obstruction to their conversion, and hoping so particular an application to the masters and mistresses from the See of London would have

Page 15

the strongest influence, they printed ten thousand copies of the letter to the masters and mistresses, which were sent to all the colonies on the continent and to all the British islands in the West Indies, to be distributed among the masters of families, and all other inhabitants. The society received accounts that these letters influenced many masters of families to have their servants instructed. The bishop of London soon after wrote "an address to serious Christians among ourselves, to assist the Society for Propagating the Gospel in carrying on this work."

In the year 1783, and the following, soon after the separation of our colonies from the mother country, the society's operations ceased, leaving in all the colonies forty-three missionaries, two of whom were in the Southern States--one in North and one in South Carolina. The affectionate valediction of the society to them was issued in 1785. "Thus terminated the connection of this noble society with our country, which, from the foregoing notices of its efforts, must have accomplished a great deal for the religious instruction of the Negro population."

7. The Moravians, Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians.*

* This section is largely based on Jones. See §6.

The Moravians or United Brethren were the first who formally attempted the establishment of missions exclusively to the Negroes.

A succinct account of their several efforts, down to the year 1790, is given in the report of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel among the Heathen, at Salem, N. C., October 5th, 1837, by Rev. J. Renatus Schmidt, and is as follows:

"A hundred years have now elapsed since the Renewed Church of the Brethren first attempted to communicate the gospel to the many thousand Negroes of our land. In 1737 Count Zinzendorf paid a visit to London and formed an acquaintance with General Oglethorpe and the trustees of Georgia, with whom he conferred on the subject of the mission to the Indians, which the brethren had already established in that colony (in 1735). Some of these gentlemen were associates under the will of Dr. Bray, who had left funds to be devoted to the conversion of the Negro slaves in South Carolina; and they solicited the Count to procure them some missionaries for this purpose. On his objecting that the Church of England might hesitate to recognize the ordination of the Brethren's missionaries, they referred the question to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr. Potter, who gave it as his opinion 'that the Brethren being members of an Episcopal Church, whose doctrines contained nothing repugnant to the Thirty-nine Articles, ought not to be denied free access to the heathen.' This declaration not only removed all hesitation from the minds of the trustees as to the present application, but opened the way for the labors of the Brethren amongst the slave population of the West Indies, a great and blessed work, which has, by the gracious help of God, gone on increasing even to the present day.

"Various proprietors, however, avowing their determination not to suffer strangers to instruct their Negroes, as they had their own ministers, whom they paid

Page 16

for that purpose, our brethren ceased from their efforts. It appears from the letters of Brother Spangenburg, who spent the greater part of the year 1749 at Philadelphia and preached the gospel to the Negroes in that city, that the labors of the Brethren amongst them were not entirely fruitless. Thus he writes in 1751: 'On my arrival in Philadelphia, I saw numbers of Negroes still buried in all their native ignorance and darkness, and my soul was grieved for them. Soon after some of them came to me, requesting instruction, at the same time acknowledging their ignorance in the most affecting manner. They begged that a weekly sermon might be delivered expressly for their benefit. I complied with their request and confined myself to the most essential truths of scripture. Upwards of seventy Negroes attended on these occasions, several of whom were powerfully awakened, applied for further instruction, and expressed a desire to be united to Christ and his church by the sacrament of baptism, which was accordingly administered to them.' "

At the request of Mr. Knox, the English Secretary of State, an attempt was made to evangelize the Negroes of Georgia. "In 1774 the Brethren, Lewis Muller, of the Academy at Niesky, and George Wagner, were called to North America and in the year following having been joined by Brother Andrew Broesing, of North Carolina, they took up their abode at Knoxborough, a plantation so called from its proprietor, the gentleman above mentioned. They were, however, almost constant sufferers from the fevers which prevailed in those parts, and Muller finished his course in October of the same year. He had preached the gospel with acceptance to both whites and blacks, yet without any abiding results. The two remaining Brethren being called upon to bear arms on the breaking out of the war of independence, Broesing repaired to Wachovia, in North Carolina, and Wagner set out in 1779 for England."

In the great Northampton revival, under the preaching of Dr. Edwards in 1735-6, when for the space of five or six weeks together the conversions averaged at least "four a day," Dr. Edwards remarks: "There are several Negroes who, from what was seen in them then and what is discernible in them since, appear to have been truly born again in the late remarkable season."

Direct efforts for the religious instruction of Negroes, continued through a series of years, were made by Presbyterians in Virginia. They commenced with the Rev. Samuel Davies, afterwards president of Nassau Hall, and the Rev. John Todd, of Hanover Presbytery.

In a letter addressed to a friend and member of the "Society in London for promoting Christian knowledge among the poor" in the year 1755, he thus expresses himself: "The poor neglected Negroes, who are so far from having money to purchase books, that they themselves are the property of others, who were originally African savages, and never heard of the name of Jesus or his gospel until they arrived at the land of their slavery in America, whom their masters generally neglect, and whose souls none care for, as though immortality were not a privilege common to them, as with their masters;

Page 17

these poor, unhappy Africans are objects of my compassion, and I think the most proper objects of the society's charity. The inhabitants of Virginia are computed to be about 300,000 men, the one-half of which number are supposed to be Negroes. The number of those who attend my ministry at particular times is uncertain, but generally about 300, who give a stated attendance; and never have I been so struck with the appearance of an assembly as when I have glanced my eye to that part of the meeting-house where they usually sit, adorned (for so it has appeared to me) with so many black countenances, eagerly attentive to every word they hear and frequently bathed in tears. A considerable number of them (about a hundred) have been baptized, after a proper time for instruction, having given credible evidence, not only of their acquaintance with the important doctrines of the Christian religion, but also a deep sense of them in their minds, attested by a life of strict piety and holiness. As they are not sufficiently polished to dissemble with a good grace, they express the sentiments of their souls so much in the language of simple nature and with such genuine indications of sincerity, that it is impossible to suspect their professions, especially when attended with a truly Christian life and exemplary conduct. There are multitudes of them in different places, who are willingly and eagerly desirous to be instructed and embrace every opportunity of acquainting themselves with the doctrines of the gospel; and though they have generally very little help to learn to read, yet to my agreeable surprise, many of them by dint of application in their leisure hours, have made such progress that they can intelligibly read a plain author, and especially their Bibles; and pity it is that any of them should be without them.

"The Negroes, above all the human species that I ever knew, have an ear for music and a kind of ecstatic delight in psalmody, and there are no books they learn so soon or take so much pleasure in as those used in that heavenly part of divine worship."

The year 1747 was marked, in the colony of Georgia, by the authorized introduction of slaves. Twenty-three representatives from the different districts met in Savannah, and after appointing Major Horton president, they entered into sundry resolutions, the substance of which was "that the owners of slaves should educate the young and use every possible means of making religious impressions upon the minds of the aged, and that all acts of inhumanity should be punished by the civil authority."

Methodism was introduced in New York in 1766, and the first missionaries were sent out by Mr. Wesley from New York in 1769. One of these says: "The number of blacks that attend the preaching affects me much." The first regular conference was held in Philadelphia, 1773. From this year to 1776 there was a great revival of religion in Virginia under the preaching of the Methodists in connection with Rev. Mr. Jarratt of the Episcopal Church, which spread through

Page 18

fourteen counties in Virginia and two in North Carolina. One letter states "the chapel was full of white and black;" another, "hundreds of Negroes were among them, with tears streaming down their faces." At Roanoke another remarks: "In general the white people were within the chapel and the black people without."

At the eighth conference in Baltimore in 1780 the following question appeared in the minutes: "Question 25. Ought not the assistant to meet the colored people himself and appoint helpers in his absence, proper white persons, and not suffer them to stay late and meet by themselves? Answer. Yes." Under the preaching of Mr. Garretson in Maryland "hundreds, both white and black, expressed their love for Jesus."

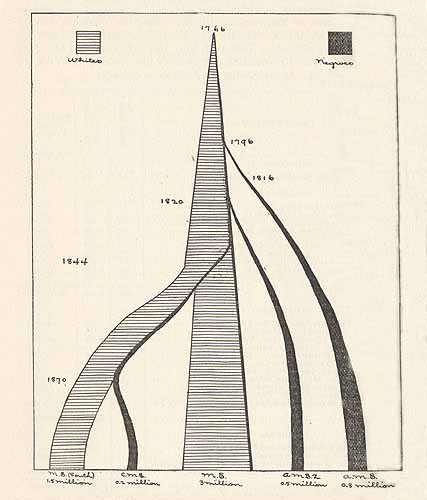

The first return of colored members distinct from white occurs in the minutes of 1786: White 18,791, colored 1,890. "It will be perceived from the above," says Dr. Bangs in his history of the Methodist Episcopal Church, "that a considerable number of colored persons had been received into the church, and were so returned in the minutes of the conference. Hence it appears that at an early period of the Methodist ministry in this country it had turned its attention to this part of the population."

In 1790 it was again asked: "What can be done to instruct poor children, white and black, to read? Answer. Let us labor as the heart and soul of one man to establish Sunday-schools in or near the place of public worship. Let persons be appointed by the bishops, elders, deacons, or preachers, to teach gratis all that will attend and have a capacity to learn, from 6 o'clock in the morning till 10 and from 2 p. m. till 6, where it does not interfere with public worship. The council shall compile a proper school-book to teach them learning and piety." The experiment was made, but it proved unsuccessful and was discontinued. The number of colored members this year was 11,682.

The first Baptist church in this country was founded in Providence, R. I., by Roger Williams in 1639. Nearly one hundred years after the settlement of America "only seventeen Baptist churches had arisen in it." The Baptist church in Charleston, S. C., was founded in 1690. The denomination advanced slowly through the middle and Southern States, and in 1790 it had churches in them all. Revivals of religion were enjoyed, particularly one in Virginia, which commenced in 1785 and continued until 1791 or 1792. "Thousands were converted and baptized, besides many who joined the Methodists and Presbyterians. A large number of Negroes were admitted to the Baptist Churches during the seasons of revival, as well as on ordinary occasions. They were, however, not gathered into churches distinct from the whites south of Pennsylvania except in Georgia."

"In general the Negroes were followers of the Baptists in Virginia, and after a while, as they permitted many colored men to preach, the great majority of them went to hear preachers of their own color, which was attended with many evils."

Page 19

"Towards the close of 1792 the first colored Baptist Church in the city of Savannah began to build a place of worship. The corporation of the city gave them a lot for the purpose. The origin of this church--the parent of several others--is briefly as follows:

George Leile or Lisle, sometimes called George Sharp, was born in Virginia about 1750. His master sometime before the American war removed and settled in Burke county, Georgia. Mr. Sharp was a Baptist and a deacon in a Baptist church, of which Rev. Matthew Moore was pastor. George was converted and baptized under Mr. Moore's ministry. The church gave him liberty to preach."*

About nine months after George Leile left Georgia, Andrew, surnamed Bryan, a man of good sense, great zeal, and some natural elocution, began to exhort his black brethren and friends. He and his followers were reprimanded and forbidden to engage further in religious exercises. He would, however, pray, sing, and encourage his fellow-worshippers to seek the Lord. Their persecution was carried to an inhuman extent. Their evening assemblies were broken up and those found present were punished with stripes! Andrew Bryan and Sampson, his brother, converted about a year after him, were twice imprisoned, and they with about fifty others were whipped. When publicly whipped, and bleeding under his wounds, Andrew declared that he rejoiced not only to be whipped, but would freely suffer death for the cause of Jesus Christ, and that while he had life and opportunity he would continue to preach Christ. He was faithful to his vow and, by patient continuance in well-doing, he put to silence and shamed his adversaries, and influential advocates and patrons were raised up for him. Liberty was given Andrew by the civil authority to continue his religious meetings under certain regulations. His master gave him the use of his barn at Brampton, three miles from Savannah, where he preached for two years with little interruption.

The African church in Augusta, Ga., was gathered by the labors of Jesse Peter, and was constituted in 1793 by Rev. Abraham Marshall and David Tinsley. Jesse Peter was also called Jesse Golfin on account of his master's name--living twelve miles below Augusta.

The number of Baptists in the United States this year was 73,471, allowing one-fourth to be Negroes the denomination would embrace between 18,000 and 19,000.

The returns of colored members in the Methodist denomination from 1791 to 1795, inclusive, were 12,884, 13,871, 16,227, 13,814, 12,179.

The Methodists reported in 1796, 11,280 colored members. The recapitulation of the numbers for 1797 is given by states:

Page 20

| Massachusetts | 8 | Maryland | 5,106 |

| Rhode Island | 2 | Virginia | 2,490 |

| Connecticut | 15 | North Carolina | 2,071 |

| New York | 238 | South Carolina | 890 |

| New Jersey | 127 | Georgia | 348 |

| Pennsylvania | 198 | Tennessee | 42 |

| Delaware | 823 | Kentucky | 57 |

Making a total of 12,215 Negroes; nearly one-fourth of the whole number of members were colored. There were three only in Canada.

The year 1799 is memorable for the commencement of that extraordinary awakening which, taking its rise in Kentucky and spreading in various directions and with different degrees of intensity, was denominated "the great Kentucky revival." It continued for about four years, and its influence was felt over a large portion of the Southern States. Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists participated in this work. In this revival originated camp-meetings, which gave a new impulse to Methodism. From the best estimates the number of Negroes received into the different communions during this season must have been between four and five thousand.

In 1800 there were in connection with the Methodists 13,452 Negroes. The bishops of the Methodist Episcopal Church were authorized to ordain African preachers in places where there were houses of worship for their use, who might be chosen by a majority of the male members of the society to which they belonged and could procure a recommendation from the preacher in charge and his colleagues on the circuit to the office of local deacons. Richard Allen, of Philadelphia, was the first colored man who received orders under this rule.

"The fact, however, is worthy of remembrance that, while the Indians--some of whom received us as guests and sold us their land at almost no compensation at all, and others were driven back to make us room, and with whom we had frequent and bloody wars, and we became, from time to time, mutual scourges--received some eminent missionaries from the colonists, and had no inconsiderable interest awakened for their conversion; the Africans who were brought over and bought by us for servants, and who wore out their lives as such, enriching thousands from Massachusetts to Georgia, and were members of our households, never received from the colonists themselves a solitary missionary exclusively devoted to their good, nor was there ever a single society established within the colonies, that we know of, with the express design of promoting their religious instruction!"

8. The Sects and Slavery.

The approach of the Revolution brought heart-searching on many subjects, and not the least on slavery. The agitation was noticeable in the legislation of the time, putting an end to slavery in the North and to the slave-trade in all states. Religious

Page 21

bodies particularly were moved. In 1657 George Fox, founder of the Quakers, had impressed upon his followers in America the duty of converting the slaves, and he himself preached to them in the West Indies. The Mennonite Quakers protested against slavery in 1688, and from that time until the Revolution the body slowly but steadily advanced, step by step, to higher ground until they refused all fellowship to slaveholders. Radical Quakers, like Hepburn and Lay, attacked religious sects and Lay called preachers "a sort of devils that preach more to hell than they do to heaven, and so they will do forever as long as they are suffered to reign in the worst and mother of all sins, slave-keeping."

In Virginia and North Carolina this caused much difficulty owing to laws against manumission early in the nineteenth century, and the result was wholesale migration of the Quakers.*

* Cf. Week's Southern Quakers and Slavery; Thomas: Attitude, etc.