". . . one of the most powerful stimulants in arousing State pride and proper appreciation of our own great men, is to be found not merely in recording their great deeds, but also in preserving their forms and features in marble and in bronze."

— J. Bryan Grimes, 1910

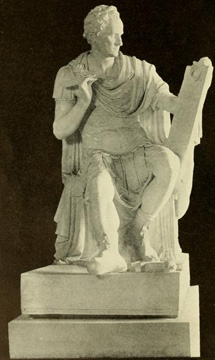

Canova's statue of Washington.Canova's Statue of Washington, (Raleigh, NC: North Carolina Historical Commission, 1910).

In a flurry of patriotism after the War of 1812, North Carolina embarked on public artistic works of commemoration, and from the beginning, officials commissioned major works from nationally renowned artists. To assert the patriotic vision of the state's place in the nation, these initial projects honored George Washington. Whatever the political divisions of the era, the hero of the American Revolution and first president of the United States attracted universal veneration.

In 1816 the state ordered two heroic paintings of Washington from internationally acclaimed artist Thomas Sully. One of these arrived in 1818 and was unveiled to great admiration, but when it was learned that the other was too big for the intended space, Sully sold it to another purchaser. Likewise in 1816, at the urging of Thomas Jefferson, the state commissioned from the celebrated Italian sculptor Antonio Canova a marble figure of Washington, to be depicted as a seated Roman general in a classical toga.

With the marble Washington underway in Italy, in 1819 state officials turned to architect William Nichols to help them decide what type of setting they should build for the famous statue. Nichols reeled off options, explaining that an equestrian figure might appropriately stand alone, a standing figure required an open temple, but a seated figure demanded an "enclosed building . . . with a dome & portico." Rather than erecting a separate structure for the purpose, he proposed to accomplish two goals at once by expanding the plain, aging State House into an "elegant" classical edifice with dome and porticoes, which would be suitable to the anticipated work of art and convenient for the legislators. The legislature agreed, and despite construction expenses many times higher than Nichols's estimate, the resulting edifice attracted universal praise. The dome lit a central rotunda, designed specifically for the seated Washington, the pride of the state as a major work of art and patriotism. In 1831, the remodeled State House went up in flames. The treasured Sully portrait was rescued — and graces the present Capitol — but despite strenuous efforts to save it, the fire ruined Canova's Washington. When work began on the State Capitol in 1833 — built in stone this time and as fireproof as possible — its cruciform layout repeated the top-lit, domed rotunda intended for the statue which many still hoped to be restored.

Edenton Tea Party, North Carolina County Photographic Collection #P0001, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

For more than half a century after 1840, the State Capitol remained bare of commemorative monuments. In 1885, when Democratic political leader Alfred Moore Waddell spoke on Confederate Memorial Day in support of creating suitable memorials to distinguished North Carolinians, he cited other states' recognition of their heroes and called not only for statues on the grounds but also busts of distinguished men inside the capitol. Finally, after 1900, the reinstated Democratic leadership began the memorial projects that fulfilled Waddell's early vision. Within the first decades of the century, busts and plaques redefined the lower rotunda of the capitol, the space some called the "Westminster Abbey of Our State." Some of the first were depictions of individuals: as J. Bryan Grimes put it at the unveiling of the first marble bust in 1910, "one of the most powerful stimulants in arousing State pride and proper appreciation of our own great men, is to be found not merely in recording their great deeds, but also in preserving their forms and features in marble and in bronze." As was true for the monuments erected on Union Square, and in line with the earlier portrayals of George Washington, most of these memorials embodied the overarching theme of North Carolina's place in the nation. While most of the early monuments on the capitol grounds commemorated the Civil War and events that followed, those placed inside the building conveyed other stories from the Colonial and Revolutionary era onward. For the first generation of memorializing, the works inside the capitol presented, as did the monuments outside, the values of the reinstated white Democratic elite leadership and their view of the state's history twentieth century.

The first memorial to be unveiled was sponsored by the Daughters of the Revolution, a national hereditary organization. In 1908, they and a host of political leaders dedicated the first memorial in the rotunda, a bronze plaque honoring "Fifty-one Ladies of Edenton," who on October 25, 1774, had signed a resolution in support of the patriot cause. Popularly named the "Edenton Tea Party" to link it with the Boston Tea Party, the resolution was described as the first such action of women in the American colonies — an important "first" for North Carolinians. The only plaque in the rotunda that takes a pictorial form, the eye-catching bronze relief shows a teapot with the image of a small house where the women were supposed to have gathered, and below it a feminine hand gracefully emptying a box of tea. In this project as in many others, elite white women took a leading role in the process of memorializing, working with male political figures to accomplish shared goals and express common values.

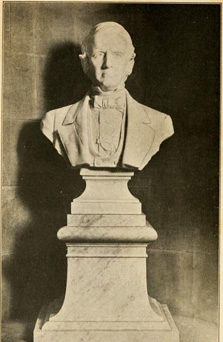

Bust of William A. Graham. Addresses at the unveiling of the bust of William A. Graham..., (Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Print, Co., 1910).

By the time the "Ladies of Edenton" plaque was unveiled, plans were afoot for marble busts of statesmen to occupy the niches in the rotunda as part of the newly organized North Carolina Historical Commission's efforts to "preserve the history of the state." J. Bryan Grimes, secretary of state and president of the Historical Commission, explained at the unveiling of the first bust, that of former governor William A. Graham in 1909, that the rotunda of the capitol contained "eight niches, designed to hold the busts and statues of eight of the eminent sons of the State." But for three-quarters of a century, "these niches remained empty . . . silently protesting against the failure of the State to perform one of her highest and most important duties, the preservation of the memories of the founders and builders of the Commonwealth." Believing that the state was "unconsciously doing herself a serious injustice by her negligence," on October 23, 1907, the Historical Commission had adopted a resolution to fund the first of an intended series of busts, a depiction of Graham for the sum of $1,000, to be made by a "reputable sculptor." The commission contracted with New York artist Frederick W. Ruckstuhl, who delivered it in December 1909. The handsomely executed bust of creamy white marble depicted Graham realistically and within the classical tradition as a man of dignity and character, with a classical drapery rather than a contemporary collar above the base. At the well-attended unveiling in 1910, after many speeches lauding Graham's virtues and accomplishments as governor, secretary of the Navy, and Confederate congressman, Grimes wound up the occasion by expressing his hope this bust would be "but a beginning and that the people of North Carolina will soon show enough appreciation of her other great sons to fill the other seven niches in this rotunda."

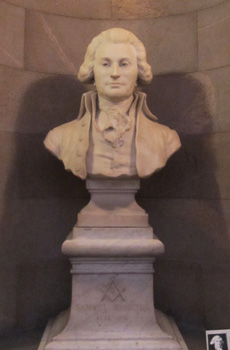

Three more "great sons" soon gained their places of honor, as additional marble busts of similar character reinforced the story of continuity of illustrious leadership from the Revolution to the present: Matt Whitaker Ransom, a Confederate general, statesman, and longtime United States Senator; Samuel Johnston, a governor and a heroic figure of the Revolutionary era; and John Motley Morehead, the first governor inaugurated in the 1840 Capitol, who, as the prime exponent of antebellum progress, provided inspiration for new leaders to advance the state in the twentieth century.

Bust of Samuel Johnston, State Capitol, Raleigh, NC. Photo courtesy of Natasha Smith.

The speakers at the unveilings praised their subjects' sterling characters and their contributions to North Carolina. In each case, too, they stressed these men's role on the national stage and their vision that extended beyond the state. They not only linked Graham, Ransom, and Morehead with antebellum accomplishments but noted that all three had been Unionists opposed to secession until the very last. Graham and Ransom had served the Confederacy nobly, as the speakers recalled, and during the "dark days" of Reconstruction, both had worked to reclaim North Carolina's place in the nation, opposing the constitutional amendments to enfranchise blacks and protect their rights, and strongly supporting the "redemption" of the state. Ransom was especially praised for his opposition as United States senator to the Force Act of 1870 authorizing federal enforcement of freedmen's rights under the amendments.

With four niches filled, the state stopped short of Grimes's hope for eight busts or figures, leaving the tall niches of the second story of the rotunda permanently empty. At the unveiling of the Ransom memorial in 1911, Grimes had reported that the Historical Commission had been "assured of the presentation to the State in the near future of busts of Governor Samuel Johnston, Chief Justice Thomas Ruffin, Calvin H. Wiley, and another which we are yet unauthorized to announce [perhaps the Morehead bust]." In the event, no memorial for educator and historian Wiley came about in Raleigh (one had been dedicated in Winston in 1904), and the memorial to Ruffin was realized in 1915 as a standing bronze figure at the entrance to the newly completed Supreme Court building across the street from the capitol (see Judge Thomas Ruffin, Presiding Over a Vanished Era).

Plaques proliferated in the rotunda after 1910. In contrast to the previous memorials, however, none of these employed an image to represent an event or individual; they were simply tablets inscribed with texts. Like the Ladies of Edenton memorial, most took as their subject North Carolinians' distinguished role in the American Revolution and formation of the early nation. Although at one level these plaques simply honor the heroes and statesmen of the eighteenth century, in the early years of memorializing there was a deeper significance in the vindicating continuity that extended from the American Revolution through the Confederacy to the recent Democratic victory and the memorializing generation.

Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence Marker, State Capitol, Raleigh, NC. Photo courtesy of P. Conway.

In 1912, the Daughters of the American Revolution (a group separate from the Daughters of the Revolution) dedicated a large marble tablet commemorating the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence and its 27 signers. This one carried many layers of meaning. For one thing, its position in the State Capitol gave official sanction to the authenticity of the supposed declaration, which patriots in Mecklenburg County reportedly signed on May 20, 1775, the first document in the colonies to assert independence from England. While some citizens and historians supported its validity, others questioned its date and content and continue to do so. Many North Carolinians cited the 1775 declaration in their vindications of secession in 1861 by claiming the mantel of the tradition begun by the men of Mecklenburg. North Carolina chose May 20, 1861, as the day for secession from the Union, and the state flag and state seal included (and still include) the May 20, 1775 date. Leaders of the 1898 and 1900 white supremacy crusades constantly invoked the spirit of their Revolutionary ancestors, and in his inaugural speech in January 1901, Governor Charles B. Aycock compared the recent "combat" with that of the Revolutionary generation, including those who "wrote the first Declaration of Independence in Mecklenburg."

After a twenty-year hiatus in memorial installations in the rotunda, patriotic groups renewed their efforts to present additional aspects of North Carolina's history within the canon established earlier in the twentieth century. In 1933, the Daughters of the American Revolution sponsored a plaque commemorating the men of the Lower Cape Fear, who had resisted the Stamp Act and fought in the Revolution, and who were often cited in the rhetoric of 1898 and 1900. In 1940, the Daughters of the American Colonies installed a plaque commemorating Virginia Dare, who had long held a special place in North Carolina history as the first Anglo-Saxon child born in America — the state's counterpoint to Virginia's Pocahontas and a reminder that the Lost Colony, in which she was born in 1587, long predated Virginia's celebrated Jamestown Colony.

The impulse to celebrate North Carolina's heroes of the Revolution and the state's role in the formation of the nation continued unabated. Even after completion of the Legislative Building a block to the north, the symbolic importance of the Capitol persisted as did the role of the rotunda as a locus of commemoration. while the spirit of the Bicentennial encouraged amplification of familiar themes in plaques to Revolutionary Governors (1976); North Carolina signers of the Constitution (1979); and the Continental Line (1983).

In 2000, with the rotunda considered full, in a counterpoint to the Mecklenburg Declaration plaque, the Historic Halifax Restoration Association dedicated a tablet in the east hallway bearing the text of the Halifax Resolves, a resolution passed on April 12, 1776, by the provincial congress meeting in Halifax, which made North Carolina the first colony to authorize its representatives at the Second Continental Congress to join in a resolution for independence. That date, along with May 20, 1775, appears on the state flag.

George Washington, State Capitol, Raleigh, NC. Photo courtesy of Natasha Smith.

For many who venerated the capitol, despite the memorials in place by the 1960s, one obvious gap remained: the empty center of the rotunda, always intended for that first and most famous memorial figure: Canova's Washington. For a time, a plaster cast had occupied the space. Finally, after long fundraising and careful research, the state commissioned the long-awaited replacement — a true replica to be carved in Italy from Canova's original model, from marble from the same quarry as the original. In 1970, George Washington again sat in Roman garb at the center of the rotunda designed for him.

In the 21st century, North Carolinians called attention to other important gaps in the State Capitol's indoor memorial landscape. Concurrent with the efforts to make the representation of history more inclusive in monuments on Union Square (see "North Carolina's Union Square"), a state commission appointed in 2009 studied the question of how best to tell a fuller story within the halls of the capitol. After pondering many concepts, the commission recommended, and the state funded and installed, bronze plaques for the purpose.

Three bronze plaques installed in the hallway west of the rotunda present texts from amendments to the United States Constitution that expanded the rights of black Americans — the 13th, 14th and 15th — and of women — the 17th. Thus far, however, the halls of the capitol possess no marble busts or bronze images of "the forms and features" of those who carried the principles of these amendments into reality. We have there no depiction of the racially mixed Constitutional Convention of 1868 that enfranchised all men, regardless of race, or of the black legislators elected thereafter. No bust or figure portrays the determined suffragettes who fought for the 17th amendment or the women who took office before and after they could vote at last. The four upper niches remain bare of figures despite Bryan Grimes's original hopes. How North Carolina will continue to tell her history in these "sacred halls" only the future will tell.