United States Colored Troops Monument.. Hertford, N.C. Image courtesy of North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. Photograph by Chris Meekins.

The Civil War monuments so conspicuous throughout the American South present an unreliable record of the history they purport to preserve. Even so, they are invaluable guides to the postwar South. They trace the shifts in gender norms after Confederate surrender, the rise of towns and industry in the region, and the phases of the extended campaign to restore white supremacy. The memorial landscape of North Carolina provides many examples historical unreliability. Few of the more than one hundred Civil War monuments in the state, for example, explicitly address the ideological stakes of the contest. The occasional explanations on some monuments are at best half-truths, like the assertion on the Edgecomb County monument (1894) that Confederate soldiers were “DEFENDERS OF STATE SOVEREIGNTY.” The monuments also offer a limited perspective on the military struggle. The squat obelisk installed on the grounds of First Baptist Church in Hertford around 1912 “IN MEMORY OF THE COLORED UNION SOLDIERS WHO FOUGHT IN THE WAR OF 1861-1865" is the sole acknowledgment that over five thousand African Americans in North Carolina took up arms to overthrow slavery.

The Confederate monuments dedicated during the quarter-century after Appomattox reflected white Southern women’s eagerness to expand on innovative wartime opportunities for organized enterprise. Soldiers’ Relief Societies became Ladies Memorial Associations, devoted to collective reburial of Confederate soldiers and community observance of Memorial Day. Fayetteville women pieced and raffled a quilt to raise $300 with which to gather thirty bodies for reinterment at Cross Creek Cemetery under an obelisk surmounted with a cross and dedicated "IN MEMORY OF THE CONFEDERATE DEAD” in December 1868. Cemetery monuments in Goldsboro (1883), New Bern (1885), Greensboro (1888), and several other sites further helped to establish “the Confederate dead” as an idealization of political unity among white Southerners. These initiatives were counterparts to the postwar construction of the national military cemetery system, which was not open to rebels. The federal installations at New Bern and Salisbury, like those at Gettysburg and Arlington, deepened the military dimension of American citizenship by inserting the government into the intimate realm of human burial.

The most widely publicized of North Carolina women’s early thrusts in commemorative politics was the memorial at Oakdale Cemetery in Wilmington. There the Ladies Memorial Association placed more than four hundred bodies under a single mound. “Let not those sacred graves be desecrated by the erection over them of marble from the Northern land,” declared a local newspaper. “Better, far better and more appropriate would it be to place there the roughest hewn post of Carolina wood.” The women instead commissioned young Confederate veteran William Rudolf O’Donovan, a self-taught sculptor trying to start an artistic career in New York, to fashion a bronze statue. Dedicated in an elaborate Memorial Day ceremony on May 10, 1872, O’Donovan’s work was the first Southern example of the single-figure soldier monument that was already on its way to becoming the standard form of Civil War remembrance in the North. The oration by former Confederate officer and future Wilmington congressman C. W. McClammy left no doubt that the Ladies Memorial Association had built a dramatic platform for expressing opposition to Reconstruction. McClammy sighed that the Confederate soldiers were fortunate not to have seen the rise of biracial Republican government. “Their virtues and fidelity will silence the voice of calumny and reinstate that sense of honor and love of liberty which the mad carnival of passion dethroned,” McClammy promised.

Confederate commemoration shifted to new terrain in the late 1880s. Local camps of the United Confederate Veterans (chartered in 1889) and chapters of the United Daughters of the Confederacy (1894) popularized ideals of aggressive masculinity and the college-educated “new woman.” These allies sometimes bickered, as when a military and social organization of young men in Goldsboro raised a monument at Bentonville battlefield (1895) in response to women’s leadership in Southern remembrance. But men and women of the Lost Cause both turned to Confederate monuments to rally Democratic opposition to Republican and Populist challenges. They also united in placing new Confederate monuments in public spaces other than cemeteries. About 85% of the approximately eighty memorials unveiled in North Carolina from 1890 to 1930 were erected outside the cemeteries. As sponsors increasingly honored soldiers who had marched to war from a particular community, rather than the soldiers buried at a particular site, the county courthouse became the most typical setting for new monuments. This trend drew energy from the proliferation of small towns in the South at the turn of the twentieth century and the heightened concentration of cultural as well as political and economic activity. A variation on the pattern was the spread of Confederate monuments on the grounds of the state capitol, including portrait statues of wartime governor Zebulon Vance (1900) and early combat casualty Henry Lawson Wyatt (1912), as well as monuments to Confederate soldiers (1895) and Confederate women (1910).

Confederate Monument, Salisbury, Rowan County, N.C., North Carolina County Photographic Collection #P0001, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This much larger second wave radiated from centers of manufacturing and associated real estate speculation and commercial development. Confederate remembrance was an expression of Southern boosterism. Winston-Salem illustrated the self-conscious modernity of the impulse when a benefit event for the local Confederate monument dedicated in 1905 featured the first showing of a motion picture to be held in town. Salisbury raised a substantial fund in a campaign headed by popular novelist Frances Tiernan and then commissioned leading sculptor Frederic Wellington Ruckstuhl to copy the flamboyant bronze statue he had recently made for a Confederate monument in Baltimore. Durham industrialist Julian Carr, whose leadership in veterans’ affairs caused him to be known as General Carr although he had served as a private in the Confederate army, summarized the primary theme of early twentieth-century white Southern commemoration when he rhetorically asked the crowd at the 1917 dedication of the Rocky Mount monument, “Is it not the Confederate Soldier, who, poor and worn with wounds, has been the guiding sire of the grand New South?”

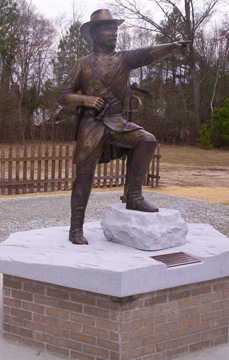

General Joseph Johnston Statue, Johnston County, N.C.. General Johnston’s statue is located on private property along Harper House Road one quarter mile east of the Bentonville Battlefield Visitor Center. Image courtesy of North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. Photograph by Richard Phillips.

The multiplication of monuments slowed markedly during the 1920s. Commemorative attention shifted to the World War. The public monument declined in vitality as a cultural form. The generation of Confederate veterans disappeared. White Southern women found new outlets for volunteerism, although the United Daughters of the Confederacy remained much more vigorous than the Sons of Confederate Veterans through the mid-twentieth century. Cemetery ornamentation reclaimed priority, most prominently at the House of Memory at Oakwood Cemetery in Raleigh (1936). Several notable non-cemetery monuments resulted from gifts of individuals rather than community fundraising, including the memorial to Confederate women and “faithful black mammies” unveiled at Wadesboro in 1934. Over the next two decades, almost no new Civil War monuments were erected in the state, but the acceleration of the civil rights movement in the 1950s prompted some segregationists to promote Confederate commemoration as a vehicle for rallying white Southern resistance. The Taylorsville monument donated to Alexander County by a local attorney in 1958 featured the strident assertion that “From 1861-1865 the heroic sons and daughters of / The Old South, under the greatest generals of all times, / Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson, Fought /Not for the preservation of slavery, but for our / Greatest Heritage–States rights.” The tactic was not entirely ineffective, but it was considerably weaker than earlier invocations of Confederate memory to overthrow Reconstruction or thwart Populism.

Monument construction waned after a brief flurry between 1956 and 1960 until several years after acclaim for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D. C., (1982) awakened interest in military monuments. The steles in Etowah (1985) and Hendersonville (2008) dedicated to Union soldiers from Henderson and Transylvania Counties were striking departures from North Carolina precedent. Confederate initiatives remained more common. Monuments in Guilford County (1986), Stokes County (1990), Rockingham County (1998), Surry County (2000), Hyde County (2001), and Yancey County (2009) honored local soldiers who had fought for the Confederacy. In these and other initiatives, the Sons of Confederate Veterans firmly supplanted the United Daughters of the Confederacy as the dominant organizational force in white Southern Civil War commemoration. The most ambitious SCV undertaking was a bronze statue of General Joseph Johnston dedicated in 2010 at the site of the battle of Bentonville. The sponsors installed the monument on private property, not on the portion of the battlefield owned and administered by the state. The separation from an official historical park mirrored the marginalization of Confederate veneration since the heyday of the Lost Cause. The resort to private property also highlighted fundamental questions about the definition of “the public” in the commemorative practices of a fragmented society. Long celebrated as a communal ideal, the Confederate monument had become emblematic of the tendency toward disunion in American memory.