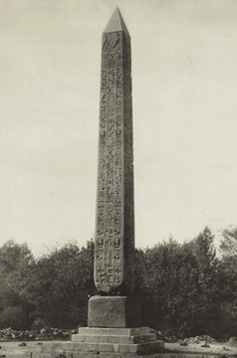

Edward Bierstadt. The New York Obelisk (Cleopatra’s Needle), 1881, New York Public Library, PC NEW YC-Cen-18

During the decades of the 1880s and 1890s, Americans caught obelisk fever.

We do not often think of fads or trends in monumental architecture as these structures are meant to endure for generations, and are thus impervious to ephemerality. Yet the ebb and flow of monument design speaks to a specific cultural moment, in which style, suitability, and popularity collide in form. The simple obelisk is such a fad that took nineteenth-century America by storm during a surge of commemorative efforts following the centennial celebration of the United States as an independent nation. As interest in the American Revolution grew after 1876, Revolutionary War memorial committees sought to merge the fight for political sovereignty with a war-torn America yearning for national unity by monument building. While Revolutionary War monument design varied from triumphal columns and equestrian statues, it was the obelisk that made its appearance as an ideal form in which to condense and represent the significance of American Independence. Simultaneously, as North Carolina sought to claim and promote its own role in the American Revolution, the state appropriated the nationally popular obelisk as the preferred monument design.

On January 22, 1881, with great fanfare and equal criticism, Cleopatra's Needle arrived from Egypt to its new location in Central Park, New York City. A gift from the khedive of Egypt, the obelisk spurred a turbulence of publicity throughout newspapers and the pictorial press. And like most fads, consumer culture took hold of the obelisk from adverting campaigns to cartoons about ladies' fashion. Yet despite the deluge of obelisk-related ephemera, a number of contemporary editorials indicate that Americans were uncomfortable with the gift. Charles Chaillé-Long argued to "Send the monument back!" and another wrote that "one rotten old obelisk is of no use to us."2 For these critics, the obelisk represented the ruins of an autocratic power, a pagan kingship that had no place on American soil.3

Frontispiece. The dedication of the Washington national monument... February 21, 1885. Published by order of Congress. Washington : Govt. print. off, 1885.

A few years later, after a long construction process begun in 1848, the Washington Monument was completed. Originally conceived as an equestrian monument and later as an Egyptian Revival mausoleum, the committee altered the plans, preferring a design that would "harmoniously blend durability, simplicity, and grandeur," in other words, an obelisk4. Stripped of the architect's ornate embellishments, the obelisk became an affordable and compact option in the nation's quest to erect a monument to Washington. But the design compromise was not universally pleasing and met with skepticism about the appropriateness of the obelisk selection. One editorial letter to Mr. W. W. Corcoran complained of the design as an uninspired derivative chimney. How could something like the obelisk invoke the character of Washington and celebrate a nation's independence?5 The sentiments echo architect Henry van Brunt's oft-quoted statement about New York's obelisk as a "dumb, colossal chimney."6

Cleopatra's Needle and the Washington Monument ushered in a wave of obelisk mania. But why did the obelisk, a debated architectural type and a symbol of Old World Empire, flourish as a monumental style for commemorating America's fight for political sovereignty in the late nineteenth century? Decades earlier, in a burst of Egyptomania, the obelisk was utilized to commemorate the battle of Bunker Hill, yet the design remained largely an anomaly in Revolutionary War monuments until the publicity hype of the latter half of the nineteenth century. And as a case study, North Carolina's commemorative landscape to the American Revolution reveals not only a desire to participate in a larger movement of national remembrance, but also an attempt to reshape the state's image as a pivotal player in the struggle for independence.

Monument Erected to the Signers of the First American Declaration of Independence, Charlotte, Mecklenburg Co. N.C., May 20th 1775", in Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

As a result of financial setbacks, construction difficulties, and design contests, the majority of North Carolina's Revolutionary War obelisks were erected ten to twenty years following the initial craze. Each of the three major Revolutionary War battles in North Carolina: Moores Creek (1776), Kings Mountain (1780), and Guilford Court House (1781), as well as the contested Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence (1775), has an obelisk that commemorates North Carolina’s patriotic efforts. The Independence Monument in Charlotte (1898), the US Monument at Kings Mountain (1909), the Cavalry Monument at Guilford (1910), and the Moore Monument at Moores Creek (1913) are a mere selection of the obelisks erected in North Carolina during a burst of monument building.

Any monument built of an imperishable material stands as a testament to time, and the obelisk, a structure dating back to the Egyptians, exemplified the desire for permanence. Originally, Egyptian obelisks were monoliths; that is, constructed from single block of stone. The mystery of how the Egyptians raised such structures became a modern marvel, but for the American obelisk, such monolithic tributes to power were replaced with a more democratic mode of construction using several stone blocks. Robert C. Winthrop spoke on how the many sections of the Washington Monument conveyed "the idea of our cherished National motto, E PLURIBUS UNUM."7 Built by the hands of many to create a unified structure, the obelisk monumentalized American democracy.

The impetus for eternal remembrance is also reflected in the obelisk's potential for dramatic height. For the citizens of Mecklenburg County, the height of the Independence Monument reached "toward the vault of heaven" and would maintain a "perpetual notice of posterity."8 And the Mecklenburg Monumental Association declared that an obelisk: [R]ising towards Heaven, amid temples dedicated to God, may produce in all minds, a pious feeling of dependence and gratitude. Let it arise until it meet the sun in his coming, let the earliest light of the morning gild it, and parting day linger and play on its summit.9

Kings Mountain Monument, Kings Mountain, N.C., in Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

The obelisk's origins in the Egyptians worship of the sun are transformed in the Independence Monument as a tower to heaven, reaching its pinnacle towards God in a revised Tower of Babel. Stripped of its pagan beliefs, the obelisk becomes a triumphal structure of America's divine right to freedom and independence. And the taller the obelisk, the closer to the immortal city in the sky and the greater the power of democratic might. The Kings Mountain Memorial Association took such a sentiment to heart when they hired the New York architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White to build an 83-foot high obelisk on Battleground Ridge. The obelisk was funded not only by Congress, but financed by North Carolina and South Carolina. A postcard published by the Asheville Post Card Company depicts the U.S. Monument as being located in North Carolina rather than South Carolina, a result of continued border disputes as to where the battle took place in 1780. Through partially financing the obelisk and declaring the monument as within state lines, North Carolina reclaimed the memory of the heroic accomplishments of their statesmen. As the tallest and the largest obelisk associated with North Carolina, the U.S. Monument embodied both the national desire to commemorate the beginnings of an American identity and the state’s own mark of memory.

Americans debated the merits of monuments given their imperial associations, arguing that this nation was free from the need to commemorate in stone.10 Puck Illustrator Bernhard Gillam's "No More of those Hideous Monuments" mocked the phase of monument building in the late nineteenth century. The scathing text that accompanied the illustration read: "It is this pork-packing self-confidence that has pock-marked this country with hideous statues and monuments and memorials, set up for the eternal laughter of the gods and generations to come."11 Behind the sea of bronze figural sculptures of prominent American men are two obelisks: the Bunker Hill Monument and the as-yet unfinished Washington Monument. Their unadorned surfaces and abstracted shape brought simplicity and grandeur to an overcrowded commemorative landscape. The obelisk became a universal monument type, one that reflected an abstracted ideal or individual whose form could transcend the mortal ties to representation. Moreover, the obelisk could symbolize the abstract idea of America. The nation could not be effectively condensed into a narrative or figural monument, but the obelisk's versatility and restraint brought form to an incomprehensible concept.

Of course, the simplicity of the obelisk also had a pragmatic purpose: cost. An obelisk was an affordable option as it is easy to produce with minimal construction costs and engineering considerations. Although The Reporter, a journal devoted to the marble and granite trade, complained of the abused proportions of obelisks and even included an illustration depicting "the perfect obelisk."12 Once the proportions between height, length, and width, were ideal, the obelisk could be modified for several sizes ranging from commemorative monuments to funerary art. T.H. Bartlett writing on early settler memorials felt that the obelisk's simple form "is the easiest and cheapest for grave-yard purposes, a convenient excuse for want of thought and an accepted apology for ignorance."13 Yet these quibbles from architects did not stop the flood of obelisks from being erected as the desire to commemorate outweighed ingenuity.

Eventually, as with all fads, the rapid adaption of the obelisk for public monuments also led to their decline in the twentieth century. Battlefields and patriots of the American Revolution had been honored and new historical moments needed to be commemorated that required a different form. North Carolina’s Revolutionary War obelisks engaged in a resurgent nationality resulting from the centennial and the aftermath of the Civil War. Yet they also affirmed the state's history as one of "the authentic precursors of American Independence."14 And the nineteenth-century American obelisk in all its monumentality was a design that conveyed the needs of a particular moment in time.

1. "Where’s your obelisk now?" Puck, (December 21, 1877): 3.

2. Charles Chaillé-Long, "Send Back the Obelisk!" The North American Review, (October 1886): 410; “The Egyptian Monument,” Puck, (July 28, 1880): 7.

3. For an extended discussion about the symbolism of the obelisk see Brian A. Curran, et al., Obelisk: A History, The Brundy Library: Cambridge, 2009.

4. John Daniel and Robert Winthrop, The Dedication of the Washington Monument…, Washington: Government Print Off., 1885, 16.

5. "Mr. Story on the Washington Monument," The American Architect and Building News, (January 11, 1879): 13.

6. Henry van Brunt, "The Washington Monument," American Art Review 1:1 (November 1879): 9.

7. John Daniel and Robert Winthrop, 52-53; Also cited in Curran, Obelisk, 271.

8. "Liberty to be Glorified," Fayetteville News and Observer (Fayetteville, NC), May 27, 1897, 1-2.

9. "Mecklenburg Monument," The Magnolia; or, Southern Appalachian 2:3 (March 1843): 206.

10. "Anti-Monumental," New York Times June 22, 1855; Also see Curran, Obelisk, 270.

11. "Cartoons and Comments," Puck, 17: 441 (August 19, 1885): 386.

12. "Obelisk," The Reporter 34 (April 1901): 41.

13. T.H. Bartlett, “Early Settler Memorials,” The American Architect and Building News Vol. 20 (December 4, 1886): 268.

14. “The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence,” Southern Historical Society 20 (Jan-Dec 1892): 335.