After the Civil War, Southern states participated in “monumania” – a wave of public monument building that peaked in the early twentieth century. Sculptors across the country received commissions to beautify urban spaces with memorials of symbolic importance. In North Carolina, as elsewhere, the bulk of these sculptures represent white male military, political, and civic leaders, and the rank-and-file soldiers who lost their lives in combat. Women have played a paradoxical role in this monumental landscape: women’s groups were important agents in the funding and creation of many Southern memorials, yet women of achievement, even today, have rarely been represented in public sculpture. When women have been depicted in stone and bronze, they have often been cast in generic or narrowly defined roles. Why is this?

Confederate Monument: Dedication, 2 June 1913., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Image Collection Collection #P0004, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Southern white women began, of necessity, reinventing their roles during and after the Civil War. They had not been permitted to go to war or to assist in governance, but they had met enormous challenges maintaining the home front during the conflict. At war’s end, women’s volunteer groups took charge of burying the dead, decorating cemeteries, and inventing mourning rituals. When the emphasis shifted near the end of the nineteenth century to decorating public squares and celebrating the positive values of the Civil War effort – such as the formation of common bonds of experience – women persevered via changing organizational structures. Ladies’ memorial societies formed in the 1860s and ’70s gave way in the 1890s to chapters of the region-wide United Daughters of the Confederacy. Through these groups, female members supported – and sometimes competed with – the goals of aging veterans and their sons for preserving memories of the war. These activist women proved time and again their ability to organize, raise funds, and complete projects, building monuments, protecting historic sites, and supporting the teaching of the “true history” of the South. In North Carolina, ladies’ organizations led drives to erect monuments in many communities, including Fayetteville, Orangeburg, and Shelby, and lobbied for state funds for the Confederate monument in Raleigh. In the process, women took on a more public role than in the past, outside the private domestic sphere that had been seen as their realm of action. As women entered business, government, and industry in the twentieth century, women’s groups continued to support memory projects honoring the casualties of the world wars and ensuing conflicts.

Edenton Tea Party, North Carolina County Photographic Collection #P0001, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Despite their leading role in the production of monuments, women are nearly invisible in the monumental landscape. Fewer than ten monuments in North Carolina commemorate individual women for their accomplishment, while others honor women as a category, such as mothers and “Women of the Confederacy.” This is because monument building was a selective process, not a representative or impartial one. Patterns of absence emerge in any inventory of public memorials – in addition to women, African Americans and Native Americans are rarely represented. The role of a public memorial is to put into high relief the accomplishments of one group or person, chosen from among all others -- a subject that may be seen to represent a model for behavior, to legitimate a value system, or to naturalize deeds that funders believe should become part of the collective memory. Often monument commissions are provoked by perceived assaults on values held dear by certain groups. Monuments are not bearers of fact, but carriers of arguments or campaigns of persuasion. Usually, if a monument is erected in a public space, such as the state Capitol grounds or courthouse square, governmental permission is required to use the space, suggesting an authoritative, collective memory.

The accomplishments of women, although often discussed by veterans groups and civic groups, were usually set aside in favor of other subjects, deemed to be more pressing, for memorialization. For many Civil War monuments, private subscriptions and donations in amounts as small as $1, were raised via dinners and concerts held over many years, with a municipal or state contribution to fill out the funding. With such limited resources, only certain people or groups could be honored. If disputes arose about subject or composition, an idea might never come to fruition. A monument, depending upon its complexity, could also take many years to prepare. Through the process of collecting money, negotiating a site, commissioning a sculptor, and choosing a design, many ideas fell by the wayside; only those with the strongest, most tenacious backing survived. Women’s groups themselves, citing other priorities, did not lobby for monuments to women. They sometimes argued instead for the limited dollars available to be spent on other efforts, such as educational programs or veterans homes.

Once it was determined that a monument should be built, questions remained about what design would strike the right note. Size, material, style, prominence of site, and the choice of sculptor all needed to be considered, and monument committees often faltered, unable to reach a consensus over these matters of emphasis. These points were debated in the late nineteenth century when a number of Southern states began the process of raising monuments to the “Women of the Sixties” or “Women of the Confederacy.” The time seemed fitting for such memorials: the veterans’ generation was waning, and attitudes about family, sexuality, and women’s roles were changing. The monuments demonstrate nostalgia for an older set of values and for women’s place in a more chivalric antebellum society. They thus partook in a debate about the proper role of women in the past and at the brink of the twentieth century.

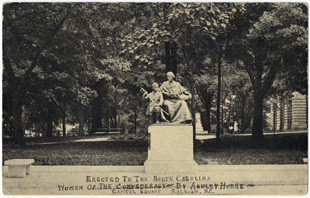

North Carolina Women of the Confederacy, "Erected to the North Carolina Women of the Confederacy by Ashley Horne Capitol Square, Raleigh, N.C." in Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

In North Carolina, a monument to Confederate women was finally built on the Capitol grounds with a $10,000 contribution offered by a single veteran, Col. Ashley Horne, who feared that no consensus to raise funds for the project would otherwise be reached. The state accepted his proposal and dedicated the site. A committee appointed by Horne chose a conception by Augustus Lukeman, a Virginia-born, Paris-trained sculptor who created historical memorials for both North and South in a clear, narrative style. The group shows a Confederate woman, touched by grief and age, holding a large book in her lap and, according to one contemporary account, “reading to her grandson the heroic story of the tragic four years” of war. The young boy, holding his dead father’s sword, gazes into the distance, perhaps thinking of the glory of war as the woman thinks of its cost. On the base of the monument, a bronze relief shows a Southern woman, one arm raised, sending soldiers on foot and horseback off to war. Another relief shows her tenderly kissing a survivor and receiving the body of a casualty.

At the unveiling of the Raleigh monument, Daniel Harvey Hill spelled out the virtues of refined feminine dignity and self-control that veterans believed they were enshrining in such a memorial. “The woman of the Confederacy was a womanly woman,” he declared, who “craved no queenhood except the sovereignty of her own home. . . . She never thought of doubting that her sphere of action was the home, and she centered her efforts on making that home a place of refinement and comfort.” In this memorial, as in a number of others, women were depicted as anonymous mothers, sisters, and wives in passive, supporting roles within that domestic sphere. The woman’s role was shown as activating others. But monuments are often reinterpreted over time within an ever-changing context.

Horne’s monument was not dedicated until 1914, six months after the old soldier’s death and on the eve of World War I, when Civil War memorial events would begin to cross with fervor for a new conflict and women would be called upon to make new efforts in the public sphere. Today’s viewers may find differing meanings in such a memorial. For some, it may provoke nostalgia for ancestors’ past valor and certain ideas about Southern identity. Others may see it as representing a mythologized story of what some North Carolinians once believed, in a lost historical era. The monument could also be a touchstone for rethinking women’s evolving role, as many people engage in different acts of remembering triggered by such memorials in our presence.