Recently a new form of commemoration has appeared on the commemorative landscape of North Carolina. Communities are electing to transform or "repurpose" historically significant buildings and sites rather than raze them. Examples of such repurposed sites range from defunct textile mills and gas stations to former school buildings and lighthouses. These repurposed buildings illustrate the evolution of historic preservation from a focus on architecturally distinguished buildings to a much more expansive notion of sites worthy of preservation. Yet the question remains as to why certain spaces in North Carolina, including sites associated with seemingly mundane activities or uses, are repurposed and preserved? The simple answer is because of the importance of the memories associated with those spaces. The American Tobacco Campus in Durham and the former Woolworth's store in Greensboro are two striking examples of the preservation and reuse of buildings that, when built, were never intended to be sites of historical memory.

The American Tobacco Company cigarette plant, Durham, North Carolina. Durwood Barbour Collection of North Carolina Postcards (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, Wilson Library, UNC-Chapel Hill.

A tall water tower and a smokestack, both emblazoned with the Lucky Strike cigarette logo, tower over the American Tobacco Campus. These and other traces of its past as a major cigarette factory are conspicuous. So too is evidence of the renovation and modernization of the site, such as a picturesque river that cascades through the middle of the campus and such modern amenities as a multi-story parking deck, benches and recycling facilities. Where tobacco employees once hustled through their workdays, employees of the YMCA, WUNC (a public radio station), restaurants, and various commercial services now work.

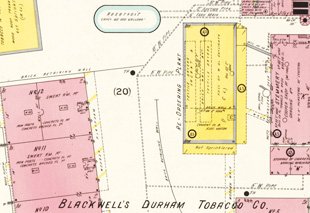

The origins of the campus can be traced to 1874, when local tobacco planter and entrepreneur Washington Duke began his career in the cigarette industry. Through a combination of savvy marketing, early adoption of technology, and monopolistic business practices, Duke built the American Tobacco Company, which by the end of the nineteenth century came to dominate the American tobacco industry.1 As cigarette manufacturing took off, the Durham facilities spread out over 16 acres and included 11 different buildings used in different phases of the cigarette making, such as curing tobacco and rolling it into cigarettes. (See Sanborn Fire Insurance company maps of Durham, N.C., 1913, Map 33) Among the cigarettes manufactured at the site was Lucky Strike, one of the most widely advertised and successful brands during the twentieth century.2

Sanborn Fire Insurance company maps of Durham, N.C., 1913. Map 33. North Carolina Maps. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (accessed May 3, 2013).

Even before cigarette manufacturing ceased at the site in 1987, plans to preserve the site were already under way. In 1977, the campus was registered as a National Historic Landmark. Two decades later Central Broadcasting Corporation purchased the site and, along with several other investors, including the county and city of Durham, began its renovation. The goal of the renovation was to eliminate the eyesore of the huge abandoned buildings and to revitalize downtown Durham, which had been in decline for decades. Because the landmark status of the site prevented the razing the buildings, the investors instead proposed to renovate them so that they would serve as a reminder of Durham's former importance as a center of the tobacco industry while simultaneously luring new businesses and consumers to what had become a derelict part of the city. First to be renovated were the Fowler, Crowe, Strickland, Reed, and Washington Buildings. In addition to two new parking garages, a river and waterfall feature, designed by Smallwood, Reynolds, Stewart, Stewart of Atlanta, Georgia, and constructed by W.P. Law Inc. based in Lexington, South Carolina, were built. Six years later, in 2004, the renovated campus attracted GlaxoSmithKline, its first major corporate client.3 By then the project had already begun to inspire new confidence in the downtown area, where vacancy rates began to fall markedly. The success of the campus led to an unprecedented demand for residential housing in downtown Durham, an area of the city that previously had been losing residential population.

Patrons of the present-day campus are reminded of the site's original purpose and history by a model of its original layout and historical photos. The campus now, as it was when workers laboriously processed tobacco and oversaw the rolling of hundreds of millions of cigarettes there each year, is an important center of economic activity in Durham. But whereas it was once an important manufacturing site for one of the first mass produced consumer goods, it is now a site of consumption, where couples hold wedding ceremonies and visitors patronize restaurants or linger in the patio before attending cultural events at the nearby performing arts center or baseball games at the adjacent stadium.

F.W. Woolworth Co. building in Greensboro, North Carolina, circa 1980. Civil Rights Greensboro, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

One of the few remaining relics of Art Deco architecture in downtown Greensboro is the preserved storefront of the F. W. Woolworth building.4 Built in 1929, the one-time store is now the International Civil Rights Center and Museum (ICRCM), a museum devoted to commemorating the history of modern civil rights activism in Greensboro and across the globe. Upon entering the building, visitors experience the contrast of the modern interior with the historical façade; but when they enter into the exhibit containing a portion of the preserved Woolworth's lunch counter where anti-segregation sit-ins occurred in 1960, they may feel as though they are stepping into a time capsule.

The display is just one indication that the building now serves a purpose profoundly different from its original function. Prior to the sit-ins in 1960, the Woolworth's building was, a five-and-dime store of the sort that were commonplace in cities across the nation. Beginning in 1878, the F.W. Woolworth Co. had pioneered such modern marketing techniques as selling discounted general merchandise at fixed prices and allowing consumers to handle and select items without the assistance of sales clerks. By 1960, Woolworth's had evolved into a multi-national corporation with hundreds of stores like the one in Greensboro across the United States, Canada, and Great Britain.

February One, Greensboro, N.C. Courtesy of Prof. Upton

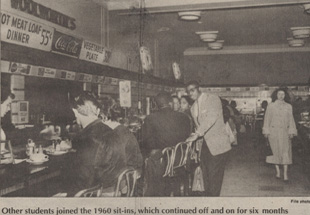

Had the events of February 1, 1960, not transpired in the Greensboro store, it almost certainly would never have been preserved and repurposed. On that date, four African American students from the North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University sat down at the lunch counter inside the Woolworth's store. Subsequently known as the "A&T Four," Joseph McNeil5 , Franklin McCain6 , Ezell Blair, Jr. (later known as Jibreel Khazan)7 , and David Richmond8 ordered coffee. In accordance with local segregation policies, the lunch counter staff refused to serve the African American men at the "whites only" counter, and the store's manager asked them to leave. The protesters, however, remained at the lunch counter until the store closed. The next day, more than twenty African American students who had been recruited from other campus groups joined the sit-in and endured the taunts of white customers. Meanwhile, the lunch counter staff continued to refuse service. By the third day, more than 60 protesters participated in the lunch counter sit-ins, which began to garner national attention. Within a week of the beginning of the Greensboro sit-in, students elsewhere in North Carolina, including Winston-Salem, Durham, Raleigh, and Charlotte, launched sit-ins. Two months later, student activists met in Raleigh at Shaw University and founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an organization that would promote the widespread application of the protest methods adopted by the sit-in participants.

Following the sit-ins, the Woolworth's instantly became redefined as the de facto original site of non-violent direct action protest and as a result henceforth was always understood to have particular historical significance. (In fact, the Greensboro sit-in was by no means the first instance of direct action protest against segregation.) In the years after the sit-ins, the events of February 1st, 1960, were periodically commemorated at the site. Numerous books were devoted to the sit-ins there, including Lunch at the 5 & 10, by Miles Wolff (1970), and Civilities and Civil Rights, by William H. Chafe (1980). Local media routinely reminded residents of the significance of the sit-ins that had occurred in Greensboro. So significant was the site that the Greensboro News & Record devoted extensive coverage to the drawn-out closing of the store, beginning with the closing of the lunch counter on October 24, 1993, to the store's final day of business on January 22, 1994. The even more drawn-out campaign to repurpose the Woolworth's and transform it into a civil rights museum also attracted expansive media attention and mobilized prominent civil rights activists, including NC A&T alumnus Jesse Jackson.9 Jackson advocated preserving the site because "It represents a fundamental spot where an American revolution was born — a revolution for social dignity."10

Jim Schlosser. Daring act by four teenagers tumbles racial barriers. From Clarence Lee Harris Papers, University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

That these historic events unfolded at the lunch counter of a mundane five-and-ten-store in Greensboro underscores both the goals of the civil rights activists and the reason why the site has been preserved and transformed into a museum. The sit-ins were a testament to the resolve of African Americans to participate in American society in the same manner as whites, however mundane such participation may have seemed. Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to relinquish her bus seat, and bomb threats were sent in to the Greensboro Woolworth's in response to black students requesting service at the store's lunch counter. Therefore, it makes sense that, following the closing of the Woolworth's, civil rights groups would campaign to transform the site into a museum. Although the notion of a five-and-dime store becoming a museum may at first glance seem incongruous, what better site could there be to convey to future generations that the routine activities that took place at the Woolworth's lunch counter had been denied to African Americans. The ordinary nature of the site, in short, is an important reason why it was repurposed.

The present-day ICRCM is the result of a protracted, $23 million renovation project. The impetus to preserve the site began with a petition drive, promoted by Greensboro radio station 102 JAMZ, that garnered more than 18,000 signatures. Rev. Jesse Jackson, Jr., a NC A&T alumnus and a participant in the sit-ins in 1960, visited the location, endorsed the effort, and joined the live broadcast. After three days, the F.W. Woolworth company agreed to maintain the site until preservationists could arrange financing to buy it. County Commissioner Melvin "Skip" Alston and City Councilman Earl Jones proposed buying the site and turning it into a museum. They founded Sit-in Movement, Inc., a nonprofit organization, that purchased the store and eventually secured sufficient funding to renovate the site.

Finally, on February 1st, 2010 — the 50th anniversary of the original sit-in — the restored building and museum opened to the public.11 Through a deliberate use of photographs, film, and other visual images associated with the civil rights struggle, the ICRCM exhibits evoke a visceral, emotional response in museum visitors. Through this approach, the Woolworth's has been repurposed from a mundane chain business location into a historical site focused on commemorating the struggle for racial equality that continues to the present day.

1. "History," American Tobacco, Downtown Durham's Entertainment District, http://www.americantobaccohistoricdistrict.com/history/page/10845184/ (accessed December 16, 2012)

2. "American Tobacco Historic District," National Trust for Historic Preservation, http://www.preservationnation.org/resources/case-studies/ntcic/american-tobacco-historic-district.html (accessed December 16, 2012)

3. "American Tobacco Campus," Capitol Broadcasting Company, http://www.cbc-raleigh.com/division/at.asp (accessed December 16, 2012)

4. Schlosser, Jim. "Historic Block Up For Sale?" News & Record (Greensboro, NC), 21 October 1993, B1.

5. Oral History Interview with Joseph McNeil by William Chafe, 1978. Civil Rights Greensboro, Duke University.

6. Oral history interview with Jibreel Khazan and Franklin McCain by Eugene Pfaff, October 20, 1979. Civil Rights Greensboro, University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

7. Oral History Interview with Jibreel Khazan by William Chafe, November 27, 1974. Civil Rights Greensboro, Duke University.

8. Oral History Interview with David Richmond by Clay Carson, April 10, 1972. Civil Rights Greensboro, Duke University.

9. Khoury, Peter. "Jackson Appeals For Woolworth's," News & Record (Greensboro, NC), 23 October, 1993, B1.

10. Ibid.

11. McLaughlin, Nancy. "Five Decades Later; Museum's Grand Opening Held at Site of historic 1960 Lunch Counter Protest," News & Record (Greensboro, NC), 2 February 2010, A1.