Whether historic homes, forts, or graveyards, commemorative landscapes are important tourist attractions in North Carolina and allow Tar Heels to mark, preserve, and interpret their past. Heritage tourism is a growing segment of the state’s tourist economy and communities large and small have tried to transform their histories into tourist attractions. These places offer a chance to view how people decide an event, a person, or a place is worthy of commemoration, as well as how the past becomes a commodity sold in the tourist marketplace. Eudora Welty once noted that a sense of place is essential to individual and collective identity. “It is by knowing where you stand,” she wrote, “that you grow able to judge where you are.” Creating commemorative landscapes is about creating a sense of place - physical, cultural, and historical - that one can touch, feel, and experience. Tourism based on this commemorative landscape is about selling that sense of place.

North Carolina’s tourism industry is a vibrant and vital component of the state’s economy. According to the United States Travel Association, visitors spent $17.6 billion in North Carolina in 2010. From casinos to amusement parks, the Old North State offers visitors a wide range of leisure attractions, but the landscape is the cornerstone of Tar Heel tourism. The state boasts the natural environment so valued by American travelers: majestic mountains, pristine beaches, and the mild climate to enjoy both. More specifically, the commemorative landscape – that place which emerges when the land is interpreted in light of its historical or cultural meaning – is an integral component of the state’s tourism economy. Federal, state, and private historic sites, museums, outdoor dramas, and even whole communities have used their commemorative roles to contribute to the state’s economy and shape how both natives and visitors view North Carolina’s past.

Playland at Carolina Beach, Near Wilmington, N.C. , North Carolina Postcard Collection (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

With a rich and varied history, North Carolina is well suited to market commemorative landscapes to tourist audiences. The state boasts a rich and diverse historical experience and a strong historical consciousness. A vibrant historical preservation movement has also helped maintain the built environment so crucial to tourist-oriented commemorative landscapes. Developing a commemorative landscape into a tourist destination rests on more than a tie to a famous person or historical event. It requires interpretation, preservation, and, sometimes, the re-creation of history at the place where it happened. No two sites are the same. Indeed, uniqueness is a prized attribute in the highly competitive tourism marketplace. The pressure created by this competition, as well as politics, interpretative approaches, and the agendas of public and private historical agencies, sometimes shape the ways such sites commemorate the past. Despite such factors, commemorative sites are important components of the state’s tourism economy and remain powerful forces shaping the state’s sense of its own past.

History and tourism have gone hand in hand for a long time. Since at least the 1930s, state officials have marketed North Carolina’s history to visitors. Unveiled in 1937, the famous and long-running “Variety Vacationland” marketing campaign touted the state’s rich history to potential visitors. Two years before, the newly formed North Carolina Historical Highway Marker Program began to identify important people and events in the North Carolina history, offering travelers brief roadside lessons on the Old North State. More recently, such efforts have moved beyond merely marking historic places to highlight historic themes designed to attract interested tourists. The North Carolina Civil War Trails project provides visitors with suggested itineraries designed to highlight the state’s Civil War experience. Similar projects offer visitors trips focused on the blues, literature, and crafts, simultaneously commemorating the state’s history and culture and marketing it to a tourist audience.

No commemorative landscapes fire tourists’ imagination like battlefields and North Carolina battlefields are leading commemorative attractions. The state’s Civil War experience is particularly popular, a reflection of the war’s popularity among heritage tourists and the fact that white Southerners make up a majority of Old North State tourists. The Bentonville Battlefield State Historic Site, the site of the last major battle of the Civil War, attracts thousands of visitors each year. Likewise, Fort Fisher near Kure Beach an mportant Confederate fort, commemorates the Federal blockade and the last days of the Confederacy. Federal Revolutionary War battlefield parks like Guilford Courthouse and Moore’s Creek Bridge interpret turning points in that war’s southern campaign as well as divisions between Patriots and Loyalists. To a greater or lesser degree, each of these battlefields commemorates both the loss of human life and war as a force in shaping North Carolina’s past. Like other historic sites, they also remind visitors of the important links between place and history.

The state’s historic built environment draws visitors enamored by old structures and their stories. Historic churches, plantation houses, and the birthplaces of famous people dot the North Carolina landscape. The Art Deco building in downtown Asheville offer visitors a glimpse at the 1920s cityscape. The Old State Capital provides tourists an example of the public architecture of the early republic, and its grounds offer insight into what people in an earlier time deemed worthy of historic commemoration. Other buildings are important not simply because they survived the ravages of time, but for what happened within them. On February1, 1960, four African American students entered the lunch counter at the Woolworth’s department store in Greensboro, challenging segregation, fueling the civil rights movement, and popularizing the sit-in as a form of protest. On February 1, 2010, the International Civil Rights Museum opened in the former Woolworth’s building, preserving the site of this momentous event and promising to educate visitors about the legacy of Greensboro and issues of inequality.

Old Salem, North Carolina Postcard Collection (P052), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Sometimes whole communities commemorate their past through preservation and reenactment. Old Salem is just one example. In 1753, Moravians, Protestant religious dissenters from central Europe, arrived in the North Carolina piedmont to create a series of religious communities in a nearly 100,000-acre tract called Wachovia. Salem, established in 1766, became the center of the community. In 1950, a group of historic preservationists and local boosters established Old Salem with the mission to preserve and interpret the Moravian experience. Designed as a living eighteenth-century Moravian village, Old Salem encourages visitor to stroll the streets, explore the buildings, interact with costumed docents, and even partake of sugar cake and other treats at Winkler Bakery. The interpretations presented at Old Salem rest on an impressive body of historical and archeological research and include a variety of topics ranging from foodways to gender roles to race relations, but visitors come for the experience of viewing what life was like for a unique group of people during a nearly forgotten time.

In Cherokee, members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians seek to engage visitors by reminding them of the special links between the tribe and their mountain home, forging a story shaped by history, myth, and the marketplace. Until the recent advent of casino gambling, the Cherokees relied on heritage tourism and the allure of the Great Smoky Mountains to draw visitors. After World War II, the tribe capitalized on American fascination with Native Americans to create a series of attractions that linked history and place. An outdoor drama about the brutal 1838 removal of the tribe to Oklahoma titled “Unto These Hills” opened in 1950. Two years later, the Oconoluftee Indian Village recreated life in an eighteenth-century Cherokee village, complete with crafters making arrowheads, weaving baskets, and making canoes. The Museum of the Cherokee Indian, also begun in 1952, offered a comprehensive interpretation of the Cherokee story, emphasizing the importance of place in shaping Cherokee society. Some critics challenge the interpretations offered at the sites and point to “chiefs” in Plains Indian dress posing for tourist photographs as evidence of the tribe’s willingness to sacrifice accuracy for profit. But for the Cherokee, commemorating, interpreting, and marketing their own past is an expression of sovereignty. In creating a multi-site commemorative landscape, the Cherokee reaffirmed their historical distinctiveness and helped to both preserve their own history and build their local economy.

"Cherokee Indians, Cherokee Indian Reservation, North Carolina", North Carolina Postcard Collection (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Death has transformed some North Carolina places into commemorative landscapes and tourist attractions. “The Graveyard of the Atlantic,” the old nickname for North Carolina’s treacherous coastline, has been used by historic sites and museums to draw visitors fascinated with the more grisly aspect of seafaring. The state’s cemeteries and grave sites draw visitors for more personal reasons. For tourists, cemeteries sometimes emerge as intriguing stops on the state’s commemorative landscape. Visitors often visit the graves of famous historical or cultural figures in order to build a tangible connection with someone they hold in high esteem. Riverside Cemetery in Asheville is a good example. Riverside is the final resting place of local elites like governor and senator Zebulon Vance, Confederate general and politician Thomas Clingman, and Japanese landscape photographer George Masa. Other graves have been transformed into touchstones for visitors. The grave of author William Sydney Porter, who penned classic short stories under the pen name O. Henry, draws visitors who revere his literary work. Some even leave $1.87 on his headstone, the pittance Della had saved to buy her husband a Christmas present in the story “The Gift of the Magi,” a commemorative act to honor an author whose worked touched them deeply. The most popular tourist draw at Riverside is the grave of Thomas Wolfe. Most famous for his debut coming-of-age novel Look, Homeward, Angel, Wolfe’s grave attracts literary pilgrims from around the world. Most do not leave an offering, although some leave a bottle of wine or whiskey on his birthday. Some search Riverside in vain for Wolfe’s angel, the Italian marble statue sold by Wolfe’s father that helped inspire his first novel. It is actually in Oakdale Cemetery in Hendersonville, surrounded by an iron fence to protect it from the visitors who seek to touch the muse of their favorite author.

Riverside Cemetery in Asheville, in the Frank Clodfelter Photographic Collection #P0032, North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

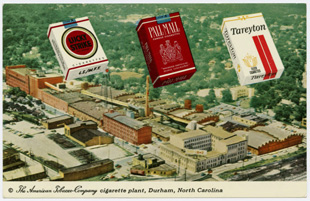

A few Tar Heel landscapes have been reinvented for a tourist audience, retaining historical and cultural ties to earlier eras while transforming the land for new purposes. The American Tobacco Historic District is an example of these reinvented commemorative landscapes, a place deeply rooted in the history of Durham and its first family, the Dukes. After the Civil War, James Buchanan “Buck” Duke and his brother Benjamin built their father’s Durham tobacco concern into an international tobacco empire. Buck Duke formed the American Tobacco Company to consolidate his control eventually monopolized cigarette manufacturing in the United States Broken up through anti-trust action in 1911, American Tobacco still commanded a respectable market share, but by the 1980s, the company had all but abandoned its old buildings in Durham. In 2004, Raleigh-based Capital Broadcasting created the American Tobacco Historic District where the former plants and warehouses of the Dukes’ industrial empire have been transformed into shops, restaurants, arts spaces, and other businesses. In an era when tobacco evokes many negative images in the public mind, the District has embraced its heritage and hopes to lure Triangle residents and tourists to the city that tobacco built.

The American Tobacco Company cigarette plant, Durham, North Carolina, North Carolina Postcard Collection (P077), North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

The founders of Princeville, North Carolina, never imagined tourists coming to their town on the banks of the Tar River in Edgecombe County. In the wake of the Civil War, a group of former slaves formed a community of their own called Freedom Hill on this ground in 1865. Twenty years later, the community became the first town in the United States incorporated by African Africans and took a new name honoring one of the community’s earliest landowners, a carpenter named Turner Prince. For generations, the people of Princeville lived according to the rhythm of the land, working in the brightleaf tobacco fields and carving out lives defined by hardship, segregation, and hope. With a population of under a thousand, Princeville endured. On September 16, 1999, nature seemed poised to destroy what isolation, racism, and poverty could not. When Hurricane Floyd came ashore in eastern North Carolina, it brought over twenty inches of rain. The Tar River covered much of the town in over twenty feet of water, destroying homes and businesses and unearthing coffins from the local cemetery. When the waters receded, state and federal officials deemed Princeville a total loss and tried to convince the townspeople to relocate elsewhere. Although some did leave, many residents could not fathom the idea of abandoning their community. Simply refusing to leave a place that had meant so much did not solve the problem of providing viable social and economic opportunities for those who remained. In their plan for the town’s future, local leaders decided to commemorate Princeville’s distinctive history and to market that history to tourists. As part of the rebuilding efforts, the town established a local history museum and welcome center and initiated a small but heartfelt marketing campaign to encourage people to come and learn about Princeville. The people of Princeville hoped that by commemorating and celebrating their community’s unique past, tourists and their dollars would help ensure that what began in the tumultuous aftermath of slavery would survive in the new century.