Fagots from the

Campfire:

Electronic Edition.

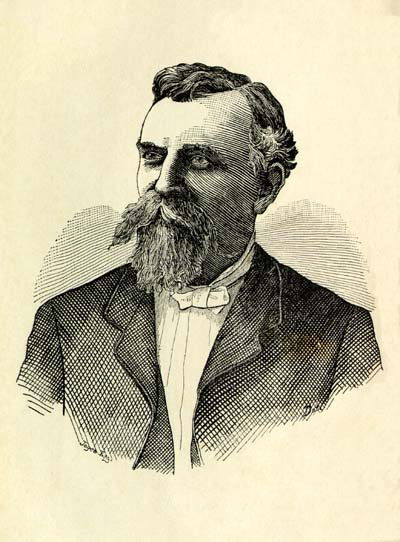

Dupré, Louis J.

Funding from the Library of

Congress/Ameritech National Digital Library Competition

supported the

electronic publication of this

title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Heather Bumbalough

Images scanned by

Heather Bumbalough

Text encoded by

Jill Kuhn and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1998.

ca. 600K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1998.

Call number E605 .D94 (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition

is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

Library of Congress Subject Headings,

19th edition, 1996

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been removed,

and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks

and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded

as ' and ' respectively.

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text

using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

LC Subject Headings:

- Dupre, Louis J.

- Soldiers -- Confederate States of America -- Biography.

- Confederate States of America. Army -- Military life.

- Scouts and scouting -- Confederate States of America -- Biography.

- Military deserters -- Confederate States of America.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Military life.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Women.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Scouts and scouting.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Desertions.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives, Confederate.

-

1998-11-09,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1998-10-14,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

- 1998-08-28,

Heather Bumbalough

finished scanning images.-

1998-10-07,

Jill Kuhn

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1998-08-26,

Heather Bumbalough

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

FAGOTS

FROM THE

CAMP FIRE.

BY

"THE NEWSPAPER MAN."

WASHINGTON, D. C.:

EMILY THORNTON CHARLES & CO., PUBLISHERS.

1881.

Entered according to act of Congress, in the year 1881,

BY L. J. DuPRE,

In the office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Page 5

INTRODUCTION.

BY

EMILY THORNTON CHARLES.

(Emily Hawthorne.)

In presenting a new book to the public, it is not necessary that the reasons therefor should be set forth in a long introduction or a tedious explanation. It is appropriate, however, that as the publisher of this unique volume, I point out its strangely original features, which impelled me to take an interest in its success and commend it to the rank and file of our army of brave defenders, as well as to those who wore the gray. Many books have been written since the war, illustrative of battles, teeming with glowing descriptions, and claiming glorious victories won by mighty generals, as in the history of the campaigns written of or given by Grant, Sherman, Johnston, and others. Most of these volumes have been biographical, rather than historical. Of those last emanating from the South, that of Hon. Alex. H. Stephens is, perhaps, the most just and unprejudiced. It gives expression to the views of a statesman, thinker, and scholar. It is therefore on a high plane, and may not, as it should, be thoroughly understood by the masses.

"Fagots from the Camp Fire" is exceptional in its style and scope. Its graphic delineation of the coarsest phases of every-day life; its portrayal of most thrilling incidents within the experience of soldiers and people of the South; how they loved and hated, starved and died; and the tender pathos which marks many pages, although told in the rude language of the uneducated, yet bear that "wondrous touch of nature which makes the whole world kin."

While leaders of opposing armies may not acquiesce in all theories propounded in "Fagots from the Camp Fire," the common people, and especially soldiers who participated in these campaigns, will agree that these extraordinary narratives are as nearly literally true as it is possible to make them, after the lapse of fifteen years.

That "truth is stranger than fiction," is often illustrated in these pages. The chief of scouts, who figures so conspicuously, holds a paper signed by General J. B. Hill, Provost Marshal-General of the Confederate

Page 6

Army, and endorsed "Approved" by General Joseph E. Johnston, now a Member of Congress from Virginia, which states that Captain *** * ******, of Company B, 7th Texas Regiment, Granberry's Brigade, served as a scout in the campaign of Georgia, and that he acquitted himself with great skill, courage, and adroitness. Thus the absolute accuracy of the "Captain's" statements is attested. The distinctive features, therefore, of this publication, are that it gives an insight into modes of life in the Gulf States and in Tennessee, which have never before been portrayed; that the wild adventures and desperate deeds of Southern scouts are authentic incidents and true to the life; and that it is the only book published which, while reciting such adventures, and depicting such scenes, is written from a Union standpoint. If the author at times advances theories which may not be approved, it must be remembered that these are one man's opinions in relation to subjects about which so few think alike. It must not be forgotten that a truthful and just picture of the country, people, and times could not have been given if the rudest, most ludicrous stories told had been omitted.

Having, as the editor of the World and Soldier, at Washington, been the recipient of thousands of letters within the past few months, from veteran soldiers of the Union; knowing how eagerly the "boys in blue" read every scrap of war history, and having received, also, many tributes from Confederate ex-soldiers in praise of the soldier's paper, although it advocates the interests and tells of the deeds of their former foes, I earnestly believe that the time has come when dissension should be buried in the grave of oblivion, and that those who wore the blue should clasp hands with those who wore the gray -

For both have suffered and both have lost,

And victory won was at fearful cost.

Therefore, commending this book to the public, we shall follow it, in a few weeks, with "The Soldier's Scrap-Book," a volume of campaign stories for the rank and file, in which many of the war incidents related by common soldiers will appear, with a collection of battle, decoration, and memorial poems. No one can conscientiously conduct a newspaper in the interest of soldiers without a desire to benefit and immortalize those who so bravely endured danger and privation, suffering and death. Such, at least, has been my experience; and -

My thought keeps guard with funeral tread,

O'er silent bivouacs of the dead;

O'er fields where friends and foes have bled;

O'er hospital and prison bed;

O'er plains where death his phalanx led;

My mind is as a lettered tome,

In which is writ, they ne'er came home.

Page 7

PREFACE.

I do not tell of great battles, or Generals, or Presidents, or Kings, and therefore, do not write history. I only define the woes, triumphs, modes of thinking, living, fighting, and dying of scouts and common soldiers. I tell of wild adventures, hideous deaths, and marvelous escapes. I recite terrible incidents, others ludicrous, and others most pitiful; and if a narrative be rude in expression, significance, or morals, it is because, if more tasteful, it would not be truthful.

Mankind recks more of Thermopylæ, with its handful of heroes, than of all the fields of filthy carnage on which Persians fell and Greeks triumphed. The Alamo, with its one hundred and sixty-five immortal defenders, leaving no survivors, will be the subject of song and story when Arbela, Cannæ, and Austerlitz are forgotten.

I cannot help thinking, therefore, that with such themes, and when I tell, too, of the woes of women, and of vices that sprang from war, and then of the negro and his relations to victors and vanquished, that this book will excite interest. This will hardly be lessened when, because of my apprehension of his virtues and character, I have chosen, without his consent, to dedicate this modest volume to Colonel W. W. Dudley, the maimed veteran whose devotion to the interests and fame of Union soldiers is only equaled by his generous estimate of the virtues of those who starved and fought for the hapless Confederacy.

THE AUTHOR.

Page 9

CONTENTS.

- CHAPTER I.

Scenes of Adventures. - Unionism in East Tennessee. - How Lincoln

was Esteemed. - The First Blood Spilled. - Heroism of

Women. . . . .13

- CHAPTER II.

Our First Expedition. - The March. - Bushwackers. -

Very like Assassination. - Too Much Corn Whiskey. - A Love

Scene. - Increasing Danger. - Involuntary Hospitality. -

Spratling's Ire, and Baptism Extraordinary. - Bushwhackers Foiled. -

The Fury of a Woman. . . . .17

- CHAPTER III.

A Narrow Escape. - A Very Cold Bath. - Gorgeous Scenery. -

Colder Still. - A Newspaper Man Spins a Yarn. - A Little

Retrospection. . . . .27

- CHAPTER IV.

The Newspaper Man Tells of His Escape from Burnside. - Compulsory

Sermonizing. - "Tristram Shandy." - A Solemn and Terrible Indictment. -

The Good that Came of It. - Descent of the Mountain. - Hunger and Roast

Hog. - Plans for the Future. . . . .31

- CHAPTER V.

Patrolling the "Neutral Ground." - "Mountain Dew." - Ghastly

Spectacle.The - Tree of Death. - Bushwhackers and Great Fright. - Successful Expedition. - Cowardice Punished. - Mamie Hughes. - Day

Dreams. - Southern Men and Women as affected by the War. - Negro

Slaves and Southern Women. - Southern Planters. - Mamie's Home

and Negro Slavery. . . . .36

Page 10

- CHAPTER VI.

The Fascinating Deserter and Gay Widow. - An Accommodating Negro. - The

Capture. - Unearthing a Deserter. - "Ef this 'ere Umbaril would

shoot" - A Corruptible Juvenile. - A Woman who loved Whiskey, and

how it mollified Her. . . . .44

- CHAPTER VII.

Soldierly Courage. - Another Deserter. - A Mountain Beauty. - A

Dying Soldier. - "He took up his Bed and Walked." - Spratling falls

in Love. - Ash-Cakes. - Ellison Escapes. . . . .49

- CHAPTER VIII.

The Underground Railway. - A Desperate Adventure. - Secession in Kentucky

and Tennessee. - In a Bushwhackers' Den. - An Heroic Woman. - The

Catastrophe. - A Graveyard Scene. - The Ghost. - A "Notiss." - A

Woman's Eloquence and Matchless Patriotism. - A Monument to her

Fame. . . . .55

- CHAPTER IX.

Conservatism. - Bell and Douglas. - Andrew Johnson. - "Rebels" and

"Bushwhackers." - Mamie Hughes and the Bushwhacker. . . . . 64

- CHAPTER X.

A Fat and Enthusiastic Widow. - General Sherman makes an Heroic Speech

and buys a Turkey. - The Pedagogue moralizes. - Terrible Condition of

East Tennessee. - Effects of the War on the South. - Demagogues. -

Landon C. Haines' Father. . . . .67

- CHAPTER XI.

Within the Federal Lines. - Friendly Negroes. - Pursued by Federal

Cavalry. - An Unequal Race for Life. - Fighting, Freezing, and

Feasting. - Cold Water Baptism. - Exhaustion. - An Imposing

Spectacle. - A Friendly Proposition. - In Search of Comfort. - Baked

"'Possum and Taters." - Welcome Repose. - Poor Whtes. - Elisha

Short's Opinions. - The Sun Rises. - Arduous Tasks. - General

Joseph E. Johnston and the Scouts. - A Scout's Mode of Life. -

The General listens to a Love Story. . . . .71

- CHAPTER XII.

The Pedagogue Talks of Mamie Hughes. - Physical Wonders of East

Tennessee. - Sequatchie Valley. - An Ancient Ocean. - Mamie

Philosophizes. - The Negro as a Soldier. . . . .81

- CHAPTER XIII.

Spratling and Bessie Starnes. - The Pedagogue corrects a Chapter in the

History of the War. - Who killed General John H. Morgan? - How he was

Esteemed. - The Camp Fire. - The Newspaper Man and the Pedagogue. - A

Political Discussion. - Absurdties of Revolution. - The Two Nations

and the Confederate War-Song. . . . .86

Page 11

- CHAPTER XIV.

Bessie Starnes. - Spratling's Story. - His Enormous Strength saves

his Life. - Two Prisoners. - Two Dead Scouts. - Spratling's

Confession. . . . .95

- CHAPTER XV.

Around the Camp Fire. - The Newspaper Man Again. - "Put me down among

The Dead." - The Newspaper Man as a Resurrectionist. - Bottled up. -

Every Man his own Ghost. . . . .100

- CHAPTER XVI.

The Newspaper Man spins another Yarn. - A Porcine Steed. - Sim Sneed

in the Role of John Gilpin. - He disperses a Battery. - A Dead

Dog. - "The Divel Sure." - Denouement. . . . .105

- CHAPTER XVII.

Spratling makes a Descent upon the Bushwhackers. - An Extraordinay

Meeting. - Spratling suddenly loses his Appetite. - At Headquarters. -

Camp Life. - Woman in War and Politics. - Why this Book was written. -

Camp Fire Morals. - An Illustration. - A Ludicrous and Pitiful

Story. - An Old Woman Eloquent. - "The Foremostest Sin that God

Almighty will go about Forgiving." . . . .109

- CHAPTER XVIII.

Death of Major General Van Dorn. - A True Story and Sad Enough. - The

Northern Version. . . . .118

- CHAPTER. XIX.

The Song that destroyed the Confederacy and dissolved its Armies. - Most

Remarkable Military Expedition of which Human History Tells or Genius ever

Conceived or Executed. - The Memorable Campaign of Moral Effects. - Its Painful and Pitiful Results. - An Apparition. - The Great Explosion in

Knoxville. - Death of Bill Carter. . . . .123

- CHAPTER. XX.

The Newspaper Man Tells of Recent Designations of the Route of De

Soto. - His Apothecary's Scales and Nest of Horseshoes. - The Monk's

Rosary. - Governor Gilmer's Castilian Dagger Handle. - Outline of

De Soto's Route Defined. - His Burial Place. . . . .133

- CHAPTER XXI.

Physical and Climatic Charms of East Tennessee. - The Captain and

Spratling Pursued by Cavalry. - A Bloody Day's Work. - Spratling

Visits Bessie Starnes. - Wounded. - The Conflagration and

Flight. . . . .142

- CHAPTER XXII.

The Captain Pursued as a Horse-Thief. - How he Escaped very

Narrowly. - A Brave Boy. - Deposition of General Joseph E.

Johnston. - How he Bade us Adieu. - Woes of Richmond. - The Famed

Cemetery of Virginia's Capital. - The Poor Child. - Its Burial

Place. . . . .152

Page 12

- CHAPTER XXIII.

Woes of the People. - How Endured. - An Ancient Georgia Village. -

Curious Story about Governor Gilmer and William H. Crawford. - Slave

Life Fifty Years Ago. - Joseph Henry Lumpkin. - How African Slavery

became African Servitude. - Providential Preparation for

Freedom. . . . .162

- CHAPTER XXIV.

The Negro as an Inseparable Adjunct of Southern Industry. - "Missis, de

Yanks is acomin'." - The Schoolmaster on the Character and Conduct of

the Negro. - "Yaller-Gal Angels." . . . .167

- CHAPTER XXV.

Newspaper Life. - Journalism under Difficulties. - A Journalistic

Repast. - Jamaica Rum. . . . .172

- CHAPTER XXVI.

Lieutenant Hughes Recites his Adventures in Southern Missouri. - Wonders

of the Lowlands. - Reckless Freaks of Dame Fortune. - A Rebel Negro

and Narrow Escape. - Two Unnamed Confederate Heroes. . . . .175

- CHAPTER XXVII.

General Grant Talks Somewhat. - Sam McCown. - The Frightful Demon of

the "Inland Sea." - Bickerstaff's Memorable Ride. - Patlanders of

Pinch. . . . .183

- CHAPTER XXVIII.

An Extraordinary Escape. - We Take Water. - A Voice in the

Wilderness. - Was it a Spirit? - A True Man and Heroic Wife. . . . .188

- CHAPTER XXIX.

The Hughes Farmhouse assailed by Federal Soldiers. - Heroism of Bessie

Starnes. - Conclusion. . . . .193

Page 13

Scenes of Adventures. - Unionism in East Tennessee. - How Lincoln was Esteemed. - The First Blood Spilled. - Heroism of Women. . . . .13

Our First Expedition. - The March. - Bushwackers. - Very like Assassination. - Too Much Corn Whiskey. - A Love Scene. - Increasing Danger. - Involuntary Hospitality. - Spratling's Ire, and Baptism Extraordinary. - Bushwhackers Foiled. - The Fury of a Woman. . . . .17

A Narrow Escape. - A Very Cold Bath. - Gorgeous Scenery. - Colder Still. - A Newspaper Man Spins a Yarn. - A Little Retrospection. . . . .27

The Newspaper Man Tells of His Escape from Burnside. - Compulsory Sermonizing. - "Tristram Shandy." - A Solemn and Terrible Indictment. - The Good that Came of It. - Descent of the Mountain. - Hunger and Roast Hog. - Plans for the Future. . . . .31

Patrolling the "Neutral Ground." - "Mountain Dew." - Ghastly Spectacle.The - Tree of Death. - Bushwhackers and Great Fright. - Successful Expedition. - Cowardice Punished. - Mamie Hughes. - Day Dreams. - Southern Men and Women as affected by the War. - Negro Slaves and Southern Women. - Southern Planters. - Mamie's Home and Negro Slavery. . . . .36

Page 10

The Fascinating Deserter and Gay Widow. - An Accommodating Negro. - The Capture. - Unearthing a Deserter. - "Ef this 'ere Umbaril would shoot" - A Corruptible Juvenile. - A Woman who loved Whiskey, and how it mollified Her. . . . .44

Soldierly Courage. - Another Deserter. - A Mountain Beauty. - A Dying Soldier. - "He took up his Bed and Walked." - Spratling falls in Love. - Ash-Cakes. - Ellison Escapes. . . . .49

The Underground Railway. - A Desperate Adventure. - Secession in Kentucky and Tennessee. - In a Bushwhackers' Den. - An Heroic Woman. - The Catastrophe. - A Graveyard Scene. - The Ghost. - A "Notiss." - A Woman's Eloquence and Matchless Patriotism. - A Monument to her Fame. . . . .55

Conservatism. - Bell and Douglas. - Andrew Johnson. - "Rebels" and "Bushwhackers." - Mamie Hughes and the Bushwhacker. . . . . 64

A Fat and Enthusiastic Widow. - General Sherman makes an Heroic Speech and buys a Turkey. - The Pedagogue moralizes. - Terrible Condition of East Tennessee. - Effects of the War on the South. - Demagogues. - Landon C. Haines' Father. . . . .67

Within the Federal Lines. - Friendly Negroes. - Pursued by Federal Cavalry. - An Unequal Race for Life. - Fighting, Freezing, and Feasting. - Cold Water Baptism. - Exhaustion. - An Imposing Spectacle. - A Friendly Proposition. - In Search of Comfort. - Baked "'Possum and Taters." - Welcome Repose. - Poor Whtes. - Elisha Short's Opinions. - The Sun Rises. - Arduous Tasks. - General Joseph E. Johnston and the Scouts. - A Scout's Mode of Life. - The General listens to a Love Story. . . . .71

The Pedagogue Talks of Mamie Hughes. - Physical Wonders of East Tennessee. - Sequatchie Valley. - An Ancient Ocean. - Mamie Philosophizes. - The Negro as a Soldier. . . . .81

Spratling and Bessie Starnes. - The Pedagogue corrects a Chapter in the History of the War. - Who killed General John H. Morgan? - How he was Esteemed. - The Camp Fire. - The Newspaper Man and the Pedagogue. - A Political Discussion. - Absurdties of Revolution. - The Two Nations and the Confederate War-Song. . . . .86

Page 11

Bessie Starnes. - Spratling's Story. - His Enormous Strength saves his Life. - Two Prisoners. - Two Dead Scouts. - Spratling's Confession. . . . .95

Around the Camp Fire. - The Newspaper Man Again. - "Put me down among The Dead." - The Newspaper Man as a Resurrectionist. - Bottled up. - Every Man his own Ghost. . . . .100

The Newspaper Man spins another Yarn. - A Porcine Steed. - Sim Sneed in the Role of John Gilpin. - He disperses a Battery. - A Dead Dog. - "The Divel Sure." - Denouement. . . . .105

Spratling makes a Descent upon the Bushwhackers. - An Extraordinay Meeting. - Spratling suddenly loses his Appetite. - At Headquarters. - Camp Life. - Woman in War and Politics. - Why this Book was written. - Camp Fire Morals. - An Illustration. - A Ludicrous and Pitiful Story. - An Old Woman Eloquent. - "The Foremostest Sin that God Almighty will go about Forgiving." . . . .109

Death of Major General Van Dorn. - A True Story and Sad Enough. - The Northern Version. . . . .118

The Song that destroyed the Confederacy and dissolved its Armies. - Most Remarkable Military Expedition of which Human History Tells or Genius ever Conceived or Executed. - The Memorable Campaign of Moral Effects. - Its Painful and Pitiful Results. - An Apparition. - The Great Explosion in Knoxville. - Death of Bill Carter. . . . .123

The Newspaper Man Tells of Recent Designations of the Route of De Soto. - His Apothecary's Scales and Nest of Horseshoes. - The Monk's Rosary. - Governor Gilmer's Castilian Dagger Handle. - Outline of De Soto's Route Defined. - His Burial Place. . . . .133

Physical and Climatic Charms of East Tennessee. - The Captain and Spratling Pursued by Cavalry. - A Bloody Day's Work. - Spratling Visits Bessie Starnes. - Wounded. - The Conflagration and Flight. . . . .142

The Captain Pursued as a Horse-Thief. - How he Escaped very Narrowly. - A Brave Boy. - Deposition of General Joseph E. Johnston. - How he Bade us Adieu. - Woes of Richmond. - The Famed Cemetery of Virginia's Capital. - The Poor Child. - Its Burial Place. . . . .152

Page 12

Woes of the People. - How Endured. - An Ancient Georgia Village. - Curious Story about Governor Gilmer and William H. Crawford. - Slave Life Fifty Years Ago. - Joseph Henry Lumpkin. - How African Slavery became African Servitude. - Providential Preparation for Freedom. . . . .162

The Negro as an Inseparable Adjunct of Southern Industry. - "Missis, de Yanks is acomin'." - The Schoolmaster on the Character and Conduct of the Negro. - "Yaller-Gal Angels." . . . .167

Newspaper Life. - Journalism under Difficulties. - A Journalistic Repast. - Jamaica Rum. . . . .172

Lieutenant Hughes Recites his Adventures in Southern Missouri. - Wonders of the Lowlands. - Reckless Freaks of Dame Fortune. - A Rebel Negro and Narrow Escape. - Two Unnamed Confederate Heroes. . . . .175

General Grant Talks Somewhat. - Sam McCown. - The Frightful Demon of the "Inland Sea." - Bickerstaff's Memorable Ride. - Patlanders of Pinch. . . . .183

An Extraordinary Escape. - We Take Water. - A Voice in the Wilderness. - Was it a Spirit? - A True Man and Heroic Wife. . . . .188

The Hughes Farmhouse assailed by Federal Soldiers. - Heroism of Bessie Starnes. - Conclusion. . . . .193

CHAPTER I.

Scenes of Adventures. - Unionism in East Tennessee. - How Lincoln was Esteemed. - The First Blood Spilled. - Heroism of Women.

After Grant's victory and Bragg's defeat, at Missionary Ridge, in November, 1863, and after the repulse of Hooker's Corps at Ringgold Gap by Cleburne's Division, Federal and Confederate armies went into winter quarters - the former at Chattanooga; the latter, at Dalton, Georgia. Detachments of Federal forces occupied positions, at short intervals, from Knoxville to Chattanooga, and thence to Bridgeport on the Tennessee River. Small bodies of Union soldiers held each railway station between Bridgeport and Nashville. Over this road supplies and re-enforcements for Sherman's army of invasion were drawn, and an army was required for its protection. General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding the Confederate forces, had his headquarters at Dalton, thirty-eight miles from Chattanooga, drawing supplies over the railway from Atlanta. General Pat Cleburne's Division was encamped along the brow of Tunnel Hill, eight or ten miles north of Dalton. In February, this cantonment was transferred to a point east of Dalton on the Spring Place Road. Our cavalry held the line from Kinton's Farm, nine miles, to Varnell's station, on the railway from Dalton to Cleveland, and thence along the hills to the Stone Church, just south of Ringgold Gap, thence to Villanow and to the boundary line of Alabama. The railway distance from Dalton to Chattanooga is thirty-eight miles. Between these points occurred many of the strange and extraordinary incidents and adventures of which subsequent pages will tell.

The area of country between the two armies within which scouts operated, having the average width of fifteen miles, extended from Knoxville, in East Tennessee, about one hundred and eighty miles, to Huntsville, Alabama. Generals Sherman and Johnston both employed large numbers of scouts, but collisions between these were

Page 14

neither as frequent nor dangerous as between Southern scouts and citizens of the country, the greater number of whom were devoted to the cause for which Sherman fought. The domestic enemies of the South were the more dangerous, not only because more blood-thirsty and murderous than soldiers, but because it was quite impossible to distinguish these bushwhackers, as they were termed in the partisan jargon of the period, from unoffending country clodhoppers.

We contemplated the most innocent-looking and rudely clad country bumpkins with keen suspicion. They recognized us at a glance, and hied away, as soon as our backs were turned, to tell our enemies of the course we had taken and of our probable resting place for the night. After asking directions from such persons, which we never followed, we were accustomed to listen for the firing of signal guns, of which we comprehended the import as well as they to whose ears they were addressed. With the armed bushwhacker we knew how to deal, but were helpless in the presence of those who seemed wholly intent upon the perfection of crops and cultivation of fields and gardens. We soon learned that most innocent-looking farmers underwent sudden and violent transformations of conduct and character. Rustiest, most illiterate and rudely clad plowmen became even demoniacal in blood-thirstiness, and in this were wholly unlike our Northern public enemies. From hollow trees, or from beneath ledges of stones on mountain-sides hard-by the farm-house, concealed breech-loaders were drawn, and assassins' bullets sent many Confederate soldiers to untimely graves.

Women and children were as false to the South and as true to the Union as fathers, brothers, and sons, and woe to the Confederate soldier, recognized as such, who followed paths into which he was guided by these loyalists. Many an unnamed grave tells where unknown and forgotten scouts heedlessly confided in statements made by matronly dames or blushing maidens. Often were brave men lured into modest cottages by proffered food temptingly spread before the weary and hungry. The feast was one of death. While hunger and thirst were appeased, and repose cunningly invited, an unseen member of the household sped away to mountain fastnesses to carry tidings of the scout's folly to the bushwhackers' strong-hold. The messenger returned with enough resolute men to render escape impossible. Matron, maid, or boy hastened from every mountaineer's home to tell bushwhackers the route of every body of Confederate scouts that traversed the so-called neutral ground between the two great armies of the North and South. Such was the condition of affairs and such the conduct of the masses of the people, especially in Eastern Tennessee. The people were poor. They read the Bible and Brownlow's Whig. They listened to Andrew Johnson, if Democrats; to Brownlow and Nelson, if Whigs; and thus, as political thinkers, were led, almost en masse, into thorough Unionism. The strongest passion of these illiterate descendants of heroes of King's Mountain and Cowpens impelled them to kill. "Death to enemies of the Union!" was the legend inscribed

Page 15

upon their hearts and memories. The bushwhackers' definition of war was written accurately in tears and blood, and flame and famine by General Sherman. It was simple destructiveness. It meant to kill.

At this period President Lincoln had won little popular sympathy or affection among Southern loyalists. His potency came later and was greatest after his death. Then Eastern Tennessee and Northern Georgia celebrated his apotheosis, awarding to his name and memory profounder respect and more honest reverence than was conceded by those who were near enough the veritable demi-god to discover human frailties.

These facts are defined that Northern people may confess some Inadequate appreciation of the sturdy, honest devotion of those men and women whose sacrifices in behalf of the Union were a thousand-fold greater than of men who bought substitutes, paid taxes, speculated in shoddy and bonds, and celebrated the Fourth of July and Black Friday.

East Tennessee loyalists believed that the enemies of the Union Deserved death, and death it was, and this internecine war, waged by one against another household, or by members of the same family, arrayed against one another, was the most relentless, bloody, and ruinous that ever desolated hearths and homes.

Rarely, very rarely, was it a "rebel's" good fortune to encounter in this region devotees at the shrine of "Confederatism." Now and then, as these pages will show, this "Switzerland of America" produced a secessionist, as earnest, devout, and active as were Union men like Crutchfield and Brownlow. It may not be improper to suggest that the first blood spilled in the great conflict was not, as is commonly supposed, at Alexandria, Virginia, when the zouave fell, but in Chattanooga, when "Bill" Crutchfield, afterwards, when Reconstruction progressed, a Member of Congress, was stricken down in his own hotel in Chattanooga. Mr. Jefferson Davis, having resigned his seat in the United States Senate, was on his way to Jackson, Mississippi. His first speech in behalf of the "new nation" was made at Bristol; his second, at Chattanooga, and in the bar-room of the old hotel, of which "Bill" Crutchfield was proprietor. Davis was defining numberless wrongs inflicted upon the South, and woes that had befallen the country in the election of Lincoln, when Crutchfield, intolerant as Davis, pronounced Davis' statements false. One John W. Vaughn, sheriff of Monroe County, afterwards made a brigadier by Davis, instantly, in defence of Davis' wounded honor, broke a black bottle, snatched from the shelf of the bar-room, over Crutchfield's head. The bleeding, stunned Crutchfield was borne helpless and senseless from the scene of conflict, shedding the first blood spilled in the war. It trickled out of East Tennessee into the mighty torrent that soon afterward flowed, steadily and sluggishly, along the course of Sherman's march to the sea.

The neutral ground contained few inhabitants entertaining the

Page 16

feelings or convictions of Vaughn, and Northern, encountered no such dangers as Southern, scouts surmounted or evaded at every step in Eastern Tennessee and Northern Georgia. Now and then a woman was loyal to the cause of the South, and the bravest and truest of our race, whether adhering to the Union or to the Confederacy, were fearless women of the mountains and valleys between the two armies. When England and Scotland were at war, the Border produced no more illustrious examples of splendid heroism or of nobility of character, or of fidelity to a cause espoused, than this mountainous, rugged district in which incidents occurred of which these pages tell. Some Walter Scott will yet make posterity remember, when traversing Northern Alabama, Northern Georgia, Western North Carolina, and Eastern Tennessee, that a sort of sanctity overshadows this region, and that it is holy ground, baptized in the blood of a border war more deadly than that waged with the rude weapons of a rude age in glens and mountain fastnesses of Scotland. For such a story-teller this modest volume contains facts on which fiction might build a pantheon peopled with gods of heroism and patriotism.

Page 17

CHAPTER II.

Our First Expedition. - The March. - Bushwhackers. - Very like Assassination. - Too Much Corn Whiskey. - A Love Scene. - Increasing Danger. - Involuntary Hospitality. - Spratling's Ire, and Baptism Extraordinary. - Bushwhackers Foiled. - The Fury of a Woman.

What follows in this narrative is nothing more than a plain recital of facts drawn from memoranda made at the time. Written with a pencil eighteen years ago these are not always perfectly legible, but enough can be deciphered to recall vividly the minutest details of incidents strongly impressed upon the memory of one only eighteen years of age when he became a chief of scouts in the army of Joseph E. Johnston.

On the day abvoe mentioned Major-General Pat Cleburne, of the most skillful and bravest of General Johnston's subordinates, selected six men, of whom I was given charge, instructing us to make the circuit of Sherman's army. We were to fix the location of each command, define the force at each point and the strength of each fortified position. We were to go first to Charleston on the Hiwassee River and learn what progress was making in rebuilding the railway bridge burned there by the retreating Confederates.

After a toilsome march of thirty miles, avoiding public highways, we rested for the night at Red Clay, a little village on the boundary line of Tennessee. We dared not make a fire. Armed with Henry rifles and Colt's repeaters and having forty rounds of ammunition and rations for five days, our journeying had been toilsome and fatiguing. Our conversations were conducted in an undertone. We moved even cautiously in the thicket in which we were concealed, fearing that the slightest unusual noise would attract the attention of some drowsy Federal sentinel.

Surely one who has never occupied such a position or confronted such dangers can never comprehend the emotions excited by our

Page 18

suddenly changed condition. For months and years we had constituted inseparable parts of a great mass of armed men. We were never conscious of personal danger. The possibility of capture or death, save in battle, never occurred to us. We had never a thought for ourselves. Parts of a vast machine, we lived and moved as such until personal identity was almost unrecognized. But here were six men - a seventh, a newspaper man, joined us at Charleston - giving only voluntary obedience to one of their number. We were not only removed from the mass of which we had become an inseparable part, but thrown, in the midst of extraordinary dangers, wholly upon our own resources as men and as individuals. We could not sleep. We were in the enemy's lines, and when fatigue wooed repose and fitfully closed our eyes, we dreamed of spies dangling at ropes' ends beneath shadows of great oaks that stretched mighty arms above our resting-place.

Wherever we slept one or two men always stood as sentinels until we resumed our march. We will never forget the feeling of unutterable solitariness and hopeless helplessness that possessed nerves and soul, and almost paralyzed us when we lay down on the frozen hillside to rest on the night of December 14, 1863. We could hear the dull roar of innumerable human voices and footsteps about the camp fires of Sherman's countless legions.

We stood guard in turn, each serving four hours. After daylight we dared to have fire enough to prepare strong coffee, most grateful to men who had passed a bitterly cold December night upon the bare earth, each covered by a single blanket.

At daylight we resumed our march, moving in indian file along the verge of the mountain range's summit. At noon we approached the Big Blue Spring. One of our number ascended a tree with a field glass, whence he scanned hills and valleys on every hand. We made coffee, rested an hour, and marched towards Cleveland where, at nightfall, we bivouacked.

We could hear the drum-beat of the Federal garrison and ourselves next morning were aroused by reveille. We loitered two days gathering information from the people of the place in reference to the strength of the garrison and examining for ourselves the earthworks, and marched to the Hiwassee River just below the village of Charleston. Here, as details hereafter given will show, our small force of men was recruited by the accession of a seventh, a newspaper man, who had escaped from Knoxville when the place was captured by General Burnside.

We wanted other edibles in substitution for hard-tack and bacon. It was agreed that Spratling, a fearless, gigantic young soldier, and I should apply at a farm-house fifteen miles away, said to have a well-stocked larder, to buy such provisions as were required. We had learned that the farmer we proposed to visit was a peaceful Union man, but were advised to be watchful. "He might betray us." We reached his pretty cottage late in the afternoon, and ate at his table,

Page 19

paying for the privilege. We were not his invited guests, and as such, owed him nothing. Spratling said that this reflection, ever afterward, gave him great satisfaction. The farmer and his wife agreed at table that they would send a well-freighted market wagon next morning to our camp. The wife was especially demonstrative, suggesting that we might have a fire and occupy a small house a few rods away in a corner of the yard. We expressed a proper sense of gratitude and soon sought this resting place. We built a fire, talked cheerily half an hour to our kindly host, spread blankets before the blazing faggots, smoked our pipes, and then, bidding him good night, with repeated assertions of gratitude, rested on the floor.

But neither Spratling nor I slept. As soon as the sound of Mr. McMath's footsteps was inaudible, Spratling whispered:

"I mean to watch that old coon. I think he is playing falsely, and if he seek to betray us, he won't find Spratling stupidly sleeping."

I concurred in this, and we covered the blazing faggots in the fireplace with ashes. When the flames were extinct, Spratling and I, lying on our faces, crept out of the hut. One stood as sentinel while the other slept just outside the enclosure about the buildings. An hour had hardly passed when Spratling, then on watch, saw McMath issue from his doorway with his wife. She even followed him to the stable, urging him to ride "hard and fast" to the bushwhackers' camp, not more, as we learned afterward, than five miles away.

We now knew what was coming. We discussed the propriety of leaving; but Spratling insisted that he must await the issue.

"I would never forgive myself," he said, "if I fled without punishing that old scoundrel's treason to pretended friendship and hospitalty. If he return alone, we will capture and send him south. If he come with five or a dozen bushwhackers, we will stampede or seize their horses, kill as many of the enemy as possible, and take refuge in the creek bottom which we examined this afternoon."

Spratling and I had slept two hours each, when we heard the clatter of coming hoofs. We counted the bushwhackers as they entered the gate, near which they left their horses. The mistress of the cottage met them at the door. She had been keeping watch, and would have discovered our "change of base" if we had not crawled noiselessly, lying on our faces, out of the cabin.

It was nearly five o'clock in the morning when we could see that some one of the eight persons in the house always watched the cabin door. McMath's wife was now actively engaged going in and out of the kitchen, and soon breakfast was spread. It is needless to suggest that Spratling and I were not asked to share this early matutinal meal. We saw the good, fat dame convey a significant brown jug, soon eloquent, as through all the ages of the world's history, of devilish deeds, into the hallway occupied by the six bushwhackers. They drank. It was the last draught of alcohol that ever went hissing down the throats of more than one of those terrible men, who thus nerved themselves for bloody, murderous deeds.

Page 20

Spratling and I had gone to the rear of the house, nearer the woods, and were at a point whence we could see distinctly every person in the hallway. In this, as stated, the breakfast-table was spread. We were now protected by the palings, shrubbery, and peavines in the garden between us and the house. The sun had hardly lighted up with earliest rays the tree-tops on the highest hills when the bushwhackers, McMath watching the door of the cabin we had vacated, sat about the breakfast-table. Their guns were ranged, leaning against the wall, on either side of the broad, open hall.

Our opportunity had come. We were about to avenge, in advance, our own contemplated deaths.

Three bushwhackers sat on either side of the table. We crawled along the palings till we reached a point from which only two of the enemy and Mrs. McMath, who sat at the head of the table with her back towards us, were visible. Three men in the line of each of our shots, we leveled our rifles. I gave the word "fire," in a hoarse whisper. I abhorred the necessity. A cold tremor ran along my nerves. I shuddered.

We would have repeated the shots, but feared that we might kill the woman. Such were her screams when her guests fell dead or wounded, that her more timid, treacherous husband was wholly helpless. While he was wringing his hands and running from one fallen friend to another and then to the relief of his suffering wife, we crossed the enclosure, and selecting two of the best horses and leading two each, rode away towards our encampment.

We were not apprehensive of pursuit. McMath had asked and we had spoken falsely as to the distance and direction of our camp and knew that some hours must elapse before he could summon a force that would dare to follow us. He supposed we had straggled from a command only seven or eight miles distant, not less than five hundred strong. While we apprehended little danger at the hands of the bushwhackers, the facts would be noised abroad and we could not remain in safety about Charleston. We congratulated ourselves on the acquisition of just horses enough, fresh and strong, to mount my footsore and weary men.

We had ridden three or four miles before we began to talk of what had happened and of what we had done. It was the first killing that either Spratling or I had had ever perpetrated, except in an open field and fair fight, and both confessed qualms of conscience.

"How could we help it?" asked Spratling. "If we had not killed them, they came armed to kill us. If we had fought them openly, we would have fallen, and certainly by suicidal hands. To fight is to kill, and this is our business, and there was no escaping the necessity for methods we adopted. If our numbers had equalled theirs, we should have resorted, and properly, to the same stratagems. General Sherman is right. War means murder, desolation, destruction, and death. We are warriors," said Spratling. "We are murderers and horse-thieves, I greatly fear," was my earnest answer.

Page 21

Spratling confessed that he did not like it, that his conscience was troubled, and that he was almost sorry, though we had six horses, that he had not assented when I proposed to leave the bushwhacker's place before his coadjutors came. Hurrying events and impending dangers made us forget everything but the fact that our speedy departure from Charleston was a matter of urgent necessity.

We had already spent two days at Charleston on the Hiwassee watching the process of rebuilding the railway bridge. Thence we rode to Pikeville, in the valley between Walden's Ridge and the Cumberland Mountains. Late in the afternoon we came to the Tennessee River five miles below the little village, Decatur. A skiff, or dug-out was soon discovered. But while a comrade and I had been searching for such a means of crossing, others discovered a whiskey distillery. They and their canteens, in the absence of the proprietor of the gum-tree pipe through which the alcohol flowed, were soon well filled. We crossed the river, concealed the dug-out in a thicket for possible future use, and a mile farther west, near a country road and the river shore, rested in a dense wood. Our sentinel stood near the highway. Unhappily, his canteen was bursting with raw, corn whiskey. He drank too deeply, and when a wagon with a dozen country girls and boys occupying it came rattling over the stony roadway, echoing songs and laughter burdening the cold night wind with the delicious music of women's voices, our sentinel could not restrain himself. He knew that the party of revellers came from a farm-house we had passed during the day, and were celebrating a country wedding. Brandishing his musket, he confronted the roysterers, demanding instant surrender. The women were frightened beyond measure. Their screams drew us to the spot. Our sentinel was holding the rein of one of the horses attached to the vehicle, and insisting that its occupants must come down and surrender. He brandished his repeater, and when we appeared, the young men, seeing that resistance would be worse than idle, descended from the wagon. They were assured that no harm was intended, and that this intoxicated sentinel and others like him need only be appeased.

What a vision of beauty I beheld in the perfect face and form of one of those mountain lassies! The luminous splendor of her great, lustrous black eyes lighted up her pale, beautiful features, as I first beheld her beneath the clear moonlight gilding hills and valleys, with matchless radiance that fascinated me. Why, I could not tell, but frightened as she was, - perhaps because I was only a year or two her senior, - she ran to my side and seized the hand that clasped my rifle. I looked into her pale, beautiful face, amazed and startled by her charms. I had never imagined that a woman's figure, eyes, pleading face, limitless confidence, and silent appeal for protection could be so eloquent. The hot blood, when I pressed her hand, rushed to my face. I said to her, "You shall not be harmed," and then added, with much hesitation, "Won't you tell me your name, and where do you live?"

Page 22

"O, yes," she answered, "my name is Mamie Hughes. I am here visiting relatives. My home is on the other side of the Union army in Georgia, and I can't get there now."

Here Mamie was suddenly silent. She suspected, I thought, that I was a "rebel," but was doubtful I was conscious that I could trust her. Her wonderful face and eloquent eyes had won my confidence, if not my heart, and I said to her, in a whisper, "I am a Southerner. Say nothing. If you utter a word, we seven will be hanged as spies."

At this moment our boisterous, half-drunken sentinel was insisting that the fiddler should organize cotillions and that we should dance by moonlight. Thinking to humor the fancy of my intoxicated men and let the merry-makers go in good humor, I said:

"Yes; we will dance by moonlight, and these gentlemen here shall drink with us and we will part friends, regretting that we frightened these beautiful young ladies."

This apology exasperated the drunken sentinel, who drawled out, "Friends! did you say, Captain? These people are d--d Yanks."

"The rest of them are, but I am not," whispered Mamie, pressing closely to my side.

It was needless to attempt further concealment of our character or purposes. I stated to the oldest of the East Tennesseeans that we were Kentuckians on our way to join the Southern army and were going out by way of Cleveland. I said further that our comrade was only impelled by too much whiskey when he arrested them and that I regretted the fact as did my associates.

There was no response. The young men were sullen and silent and Only the pretty Mamie beside me pressed my hand very gently. Another girl, more fearless than the rest, said, laughing:

"Oh! it makes no difference. Let us make a night of it and dance with these soldiers. What a jolly story it will be to tell. We are prisoners of war and can't help ourselves. Let us dance."

"Surely," I answered, "no harm is intended, and I would gladly have those gentlemen there join us. Such opportunities do not often present themselves, and we soldiers must take advantage of them."

I whispered to Spratling, when the young East Tennesseeans made no reply to my proposition, to see that neither of them left while we danced. He stalked out, a very giant, into the roadway and stood like a massive statue of granite, his presence a significant menace.

The fiddler, half-drunken, began his task. I led in the dance with Mamie Hughes. She soon entered into the spirit animating us and forgot that we were strangers. I was lapped in the joys of Elysium. I forgot the lapse and value of time. I told in whispered, earnest words the story of my love, and surely the pretty, blushing, silent girl was not displeased.

Spratling came at last, while I was looking into Mamie's fathomless eyes and dreaming I knew not what, and said to me:

"Captain, it is time we were off. This place won't be safe for us

Page 23

after daylight. These prisoners of mine are furious and most impatient. They have been plotting our destruction. One of them there, I am sure, loves madly that pretty black-eyed girl you have been dancing with. He would murder you now if he dared. Our presence here will be reported to Yankee scouts within an hour and we must be off. Escape even now is hardly possible."

While the rest of Mamie's friends were clambering into the wagon she told me where her parents lived. I said to her:

"You must not forget me, Mamie. I will surely see you again. You will not forget me will you?"

"Come and see me," she answered. "I will tell them at home how good, and brave, and true you are."

She was in the act of clambering over the wagon wheel into the body, where her friends were already seated, when I caught her arm and whispered, as I raised her into the vehicle, a reassertion of my deathless love. I detected a tremor passing over Mamie's frame. She turned to look, as I lifted my cap, into my sunburnt face. The wagon moved rapidly away.

Kissing her hand she tossed the breath that passed her rosy lips, as if it had been a sparkling gem dissolved in morning mists, towards the spot where I stood entranced, motionless, and oblivious of everything except the wondrous charms of the departing divinity.

I don't know how long I might have stared in the direction Mamie had gone if Spratling, the bravest and truest of men and scouts, had not said:

"Captain, it is time, if you don't propose to follow that pretty girl, that we were getting out of this country. Within two hours a squad of cavalry will be here looking for us."

Within ten minutes we resumed our march, but not in the direction of the towns I mentioned to Mamie's friends. On the contrary, we moved westwardly towards Walden's Ridge. We had not proceeded five miles when we heard signal guns in many directions and the sound of horns used for like purposes by the native Unionists or bushwackers. We ascended the ridge to its summit. Day was dawning when we looked down into the long, deep valley below. Signal fires still blazed at different points, and a rocket, making lights of different colors, climbed through the air far above the ridge and exploding fifteen or twenty miles away, recited the story told at headquarters of the Union army by Mamie's friends. It stated, "There are seven spies within our lines." In any event this was the translation we gave to this sign in the heavens, as significant of capture and death as was that of victory and empire which appeared to Constantine.

Throughout the weary day, when we peered forth from our hiding place, we could discover bodies of horsemen moving in the valley below, in all directions, in search of the Confederates known to be within the Federal lines. Using a powerful field glass we defined during the day the route we were to pursue during the night that we might cross the valley in safety between Walden's Ridge and Cumberland Mountains.

Page 24

We descended, with darkness, into the valley and moved rapidly across it. We reached the mountain's summit before day dawned. After this toilsome march, occupying the whole night, we were without food, fatigued beyond measure, hungry as famished wolves, and in the midst of relentless enemies. We had neither food, tobacco, nor coffee.

Our condition was becoming desperate. At two o'clock in the afternoon we found in this sparsely populated district a modest little log farm-house. Stationing my men about it to prevent the escape of its inmates, I applied for food. The mistress of the cabin refused to sell anything. There was no help for it. We entered the cabin, and telling the good dame that we were starving and desperate and that she must give us bread or her home would be destroyed, she sullenly prepared dinner of the coarsest food. Two men, that we might not be poisoned, watched the process of cooking it, and we ate ravenously. The timid nominal head of the household begged his wife to give us all we demanded, and soon intimated privately that he was a devout "rebel." We knew he was lying, but accepted his assertions as if we deemed them true. We stated that we were of Morgan's cavalry, and en route to Kentucky to bring out recruits. We made minute inquiries about roads leading north to McMinaville. He answered truthfully, as we happened to know.

Late in the afternoon, when about to depart, we almost made a Rebel of his red-haired, hideously ugly wife by presenting her five dollars in United States currency. She grinned so gleefully when Spratling gave her the money, and drew so near to express her amazed gratitude, that Spratling, dreading a kiss from the ignorant, vulgar, frightful creature, leaped from the doorway. He told me he was never "scared before in all his life." She was very thin and her back was bowed, as Spratling described her, like that of a "razor-back hog." Her frowzy, red hair, unkempt for twenty years, was powdered with ashes. She wore two garments. The outer, made of four yards of dingy gray calico, was tucked up at the waist, exposing her red, rusty, sinewy limbs almost to the knees.

She was offended by Spratling's sudden terror and retreat, and we knew that this Medusa of the mountains, if possible, would avenge the indignity. She began to denounce us. Her eloquence was absolutely wonderful. Daniel O'Connell's traditional fish woman could never have been more voluble or coarse than this frightful hungry-looking, red-faced, red-headed, and red-mouthed angular creature. She leaped violently around the great barrel-churn in the yard and kicked at each of a dozen lazy, cowardly, yelping hounds that lay about the great receptacle of sour milk. She made and sold butter to Federal soldiers encamped in the valley, and in neighboring villages.

Spratling was noted for his tremendous strength. Like most Physically powerful men, he was exceedingly good natured. But it was wholly impossible to withstand shocks to one's temper

Page 25

administered by this voluble termagant. Spratling was first amazed, and when she finally stood facing him, her arms akimbo and legs extended as far apart as the contracted calico would admit, and poured forth a volley of disgusting epithets, Spratling could no longer contain himself.

He suddenly seized the scrawny, bony creature, and inverting her, high in the air, as suddenly thrust her, head foremost into the barrel-churn half full of milk. The woman's stockingless legs were twirled about piteously above the top of the churn. I was paralyzed for a moment. The scene was painfully ludicrous. But the woman was drowning. Convulsive movements of her red legs showed that she was in a death struggle. Even the dozen dogs stood up and looked on in mute astonishment. To spare the woman's life I suddenly tipped the churn over. Her clothing was rudely displaced and as the milk spread over the lower side of the little enclosure, and her head and shoulders were uncovered, she crawled out backwards.

Evidently those dogs had never witnessed such an exhibition. As the good dame backed out of the barrel on all fours, the dogs stood transfixed with astonishment, staring a moment at the unusual spectacle, and then, howling piteously, each turned and fled in abject terror. Convulsed with laughter, I ordered my men to fall into line and march. Spratling was holding his sides and rolling over and over on the ground. The mountain groaned beneath roars of laughter.

It was horrible and cruel, but no incident half so ludicrous was ever witnessed by a squad of veterans. The good dame's senses were hardly restored when we began at last to move rapidly away. She finally rubbed the grease out of her eyes and began to comprehend the ridiculous aspect she had presented. She gathered up her consciousness, and pulled down her petticoat and began to gesticulate wildly, and pour forth an interminable vocabulary of coarse epithets. She pursued us to curse poor Spratling who ran down the declivity roaring like the bull of Bashan.

We traveled rapidly perhaps five miles along the road we had been directed to take leading to McMinaville. The moon had not risen and total darkness enveloped us. Leaving the highway we entered the woods going directly back towards the scene of buttermilk baptism. We moved as silently as possible and had not reversed our course half an hour till we heard the red-headed woman's sharp, clear voice ringing out on the cold night air. She was urging a dozen bushwhackers to keep pace with her in pursuit of "infernal pimps of hell and Jeff Davis." Her wild fury and shocking imprecations made us, rude soldiers as we were, shudder. The winds stood still that they might not bear on their weary wings the insufferable burden of her horrible oaths. We were even sickened by the woman's mad depravity and infernal fury. When the echoes of her harsh, sharp voice were no longer audible, I said to Spratling: "Hell hath no fury like a woman - baptised in buttermilk." Spratling's suppressed laughter shook the tree against which he rested his sturdy body, and we

Page 26

resumed our toilsome journey over shapeless stones and through mountain thickets, never resting through that livelong, weary night.

We marched by night and rested during daytime until we reached Stevenson near the Tennnessee River on the Nashville, Chattanooga and Memphis roads.

Page 27

CHAPTER III.

A Narrow Escape. - A Very Cold Bath. - Gorgeous Scenery. - Colder Still. - A Newspaper Man Spins a Yarn. - A Little Retrospection.

A devoted rebel family at Stevenson furnished supplies while we were encamped in a secluded spot near the village. We mixed occasionally with passengers on railway trains, from Memphis and from Nashville, meeting at this place. Spratling was a capital farmer, and I, a plow-boy. We wore the rude "butternut" or homespun goods of the country and only a pistol and knife, never visible. We received northern newspapers from every quarter and carefully filed away every paragraph that might be of value to Generals Bragg and Johnston. Wounded and sick soldiers, in endless trains, now and then moved northwardly, and interminable supply trains, day and night, went south. We noted everything. From sick-leave officers awaiting transportation, and from quartermasters' and commissaries' agents we learned how many they fed or transported in many divisions and corps. We made contracts to supply an Ohio brigade with eggs and potatoes which were never executed, perhaps because "bread and butter" brigades, and divisions, and corps, alone, came then, as now, out of Ohio.

Early on the morning of December 30, 1863, the good dame who had furnished our simple meals came to our resting place to say that a little child of a bushwhacking neighbor had said that the rebel camp on the mountain-side would be attacked that night and its occupants shot or hanged. I proffered the woman fifty dollars in greenbacks. She refused to accept it; but when I said, "You are poor, and I am paid by the government and given this money that I may give it to such as you," she said, "I did not know how I could live when you went away, yet I came to urge your immediate departure. With this fifty dollars and what I have saved I can feed and clothe myself and children almost a year." She kissed my hard, sunburnt hand, and

Page 28

with tearful eyes turned away. I never saw her afterward, but no braver or truer woman lives than Mrs. M--y, of Stevenson.

How bitterly cold were the last days of December, 1863, and the First of January, 1864, surviving soldiers serving under Rosecranz, and Sherman, and Johnston, and Bragg will never forget. Early in the morning of the 30th of December we strapped our blankets on our backs and with three days' rations traversed the distance between Stevenson and Bridgeport. We reached the river just after nightfall. Fiercely cold as were winds and waves there was no help for it. We must cross. There was no security save in placing the river between ourselves and the relentless bushwhackers. We could find no boat, and the swollen river, divided in its midst by a long, narrow island, was then, perhaps, two miles wide. It seemed, when we looked out, wistfully and anxiously enough, that bitterly cold night, upon its moaning, starlit waters, certainly ten miles in width.

Of a wrecked boat on the shore we constructed a raft capable of conveying our blankets, clothing and weapons. We swam beside it down the river to the island. Almost frozen when we reached the sandy bank, we lifted the raft out of the water, bore it across the island, launched it again, and again drifting down and across the river, landed safely, but paralyzed by cold, on the southern bank. Icicles clung to my hair and beard. My teeth chattered and I felt that numbness and drowsiness slowly overcoming me which immediately precedes death. We rubbed, one another violently with blankets and when thoroughly dry and re-clad in woollen I never enjoyed so keenly the sense of perfect youthful vigor and vitality. I was aglow with ecstatic physical blessedness. We soon ascended and followed the ridge that connects Bridgeport with Lookout Mountain. We stood upon the summit of the precipice that overhangs the railway and the Tennessee. The railway track rests upon the verge of the stream and enormous, rugged stones superimposed on one another like those of some mediæval ruin rise precipitously hundreds of feet, and are projected beyond the railway and overhang the water's edge. At day-dawn we looked down from this dizzy height. A railway train going to Chattanooga came roaring and shrieking from Bridgeport. It seemed as we contemplated it, moving with tremendous velocity Constantly accelerated into the river. We shuddered involuntarily when it went down out of sight under the cliff, and seemingly headlong into the broad, boisterous bosom of the Tennessee. Then ensued the silence of death. Great, projecting stones cut off sounds and vision, and the sudden stillness that pervaded mountains, valleys, and river was painful to the last degree.

With a wild shriek of seemingly ineffable delight the locomotive, its great, black pennon of smoke curved backward, rushed from cavernous depths below to greet from the hill-top it ascended, the splendors of the sun just rising on the brightest and coldest morning that ever dawned upon the South.

In re-writing these memoranda I omitted a page to which I now

Page 29

recur. While we were at the railway bridge which Federal soldiers were rebuilding across the Hiwassee River at Charleston we encountered a gentleman who had been now and then in the Confederate States' service as a staff officer, but for several preceding months editing a paper at Knoxville. He was well known to us and and at his own suggestion became, temporarily, one of our number. He withstood hardships uncomplainingly and whiled away tedious hours of compulsory idleness with stories he had gathered while war raged. His purpose was to reach Atlanta, whither his newspaper, when Burnside, with snowy locks, and side whiskers, and smooth towering occiput came down upon Knoxville, had been removed. On the night of December 31, 1863, colder if possible than the preceding night, we climbed the summit of Lookout Mountain. If the one hundred and fifty thousand soldiers then within fifty miles of Chattanooga were reading at the same instant, the above sentence, they would each whistle and shudder, and perhaps one hundred thousand would exclaim, una voce, clapping their sinewy hands, "It was --- cold!" It's a pity, but old soldiers will use frightful exclamations. But none have forgotten the terrors of the night which witnessed the death of 1863 and the birth of 1864. Seven of us, with a blanket each, not daring to build a fire and hungry as famished wolves, spent that fearful night on the topmost summit of Lookout Mountain whereon some ancient fable tells that Hooker fought a battle even among the clouds.

In the starlight, while looking for a place protected against Northern blasts, a shallow cavern was discovered. We gathered dry leaves and made a resting place within. And yet such was the insufferable cold that we could not sleep. We smoked our pipes and "spun yarns" through the tedious hours of the weary night.

"Gentlemen," said Bowles, one of our number, "I have seen and shared in several battles, and a big battle is only a rapidly alternating succession of d----d big scares; but I never witnessed such an infernally big scare as the red-headed milk-maid of the mountains inflicted on them d----d dogs."

Then followed such shouts of laughter that I absolutely feared the echoing peals would be borne by cold blustering winds down into Federal headquarters just below in Chattanooga.

"If the dogs have got back," said Spratling, "and I'm going there to see about it, I'll bet ten to one that every time she stoops, 'she stoops to conquer' and them d----d dogs go flying and howling down the deep jungles of Sequatchie Valley."

"I can never forget the scene," interposed Blake. "When she stood on her head in the churn, her little, starveling legs dancing an inverted hornpipe, the picture was sublime in its very uniqueness. But when the captain here overturned the churn and the dogs all stood up and looked on with growing interest, licking their chops and crying over much spilled milk, and then, when their attention was gradually arrested by the old woman backing out of that churn wholly uncovered and on all fours, it was entirely too much for the

Page 30

dogs. It was more than I could stand. I turned away only to see and hear the dogs frightened, shrieking, and flying in all directions."

"Do you know," continued Blake, "that the woman's husband was delighted? He sneaked off. I saw him behind the chicken house, throwing himself back and forth like a cross-cut saw, and holding his sides with both hands, his cheeks swollen and his eyes bursting from their sockets. It was keen enjoyment of fun struggling against the terror in which he held his red-headed, dreadful wife. We made a good rebel of him. Don't you remember that we heard not a word from him when the wife led our pursuers so noisily and vengefully on our track. We have won him, and if ever I go on another expedition in that direction I would not hesitate to trust that man. His gratitude to us is boundless, and his devotion will be admirable."

Page 31

CHAPTER IV.

The Newspaper Man Tells of His Escape from Burnside. - Compulsory Sermonizing. - "Tristram Shandy." - A Solemn and Terrible Indictment. - The Good that Came of It. - Descent of the Mountain. - Hunger and Roast Hog. - Plans for the Future.

There was silence and an unavailing purpose to sleep when the newspaper man said that he had told us how he escaped from Knoxville, going out on one side of the then little city when General Burnside entered on the other.

"It was impossible to go directly south. The railway leading to Chattanooga was held at every bridge and station by Federal pickets. Therefore I went towards Nashville. I spent a day at Kingston, an ancient town of twenty-five hundred inhabitants on Clinch River at the base of the Cumberland Mountains. Thence I journeyed slowly southeast, pretending to be a Kentuckian on my way to Chattanooga where my brother was dying in the hospital.

"I had, as a Whig and Unionist, traversed this district, and now from the home of one friend I was directed to another. I traveled at night, and was accompanied, on horseback or in a farm wagon, by the political and partisan friend with whom I had spent the preceding night. I was educated, before I entered the university and afterward the law-school, at a theological college, and learned how to prepare very acceptable sermons, perhaps for the reason that I could memorize readily and recite ore rotundo what I had written. When I first encountered you, and when Blake recognized me, I had been forced, most unwillingly, to enact the role of chaplain and missionary sent down from Cincinnati by the Young Men's Christian Association. Of course I sought the acquaintance of the best people of the place, and was at last forced to deliver, much against my will, two sermons while traversing the country from Kingston to the Hiwassee at Charleston. The last was pronounced, the day before we met, with infinite zeal

Page 32

and fervor. In my audience were many grim, but devout, Union soldiers. On this occasion I delivered the sermon which you read in Tristram Shandy. Of course I had amended, modernized, and localized it. Those most familiar with Sterne would hardly have recognized the pretty homily. I used this charming discourse because I had mastered it perfectly and was sure I would go through with the day's work never incurring a suspicion or exciting a doubt as to genuineness of the character I assumed. If I had not played Beecher, on the most awkwardly. But I was no spy. I only sought to escape into the Gulf States and was overjoyed when I recognized my learned friend Blake here in the rude garb of an East Tennessee clodhopper at Charleston.

"So much by way of prelude to a recital of incidents of the previous Sunday. There was a Methodist conference in session in the village of Kingston. I had just reached the place, and, Sunday morning as it was, found idlers about the tavern eyeing me suspiciously. When any two persons saw me approaching they parted at once and each went his way. The somewhat aged landlord was studiously polite and reserved. Seeing many people coming into the village I learned that the Methodist conference of the district was to sit and resolved, rather than be captured by these bushwhackers and shot or sent a prisoner of war beyond the Ohio, to become a Northern missionary. I took a conspicuous seat in the church soon filled to overflowing.

"Near me sat a bright-eyed, slender, sallow little preacher. He wore a threadbare broadcloth coat of the Methodist regulation pattern. There were constant nervous twitchings of the corners of his mouth and laughing devils in his merry eyes. His name, as I learned afterward, was Weaver, a famous practical joker as well as eloquent evangelist. A song was sung. The venerable Bishop of the district occupied a raised seat in front of the pulpit and bending in the presence of God uttered a fervent prayer for peace and for the 'restoration of harmony and good government.' Though there was nothing in the prayer pronounced by the devout old man to offend a 'rebel,' he was evidently loyal to the 'Stars and Stripes' as were nine-tenths of his hearers.

"Silence, when the Bishop resumed his seat, pervaded the assembly. At length a youthful, graceful preacher addressed as 'Brother Williams,' evidently much excited, and pale and tremulous, rose in the midst of the congregation, and, hesitating and stammering, said:

" 'Brethren, Brother Jones and I came to town early this morning with Brother Weaver.'

"I turned and looked at Weaver. There were a thousand merry devils lurking in his bright, mischievous eyes. The corners of his mouth were drawn down and lips suddenly compressed. Seeing that the eyes of the assembly were turned upon him, he modestly bowed his head and sat in moody silence and perfect stillness gazing at his feet.

"Brother Williams proceeded:

Page 33

" 'While we were crossing the main street of the town awhile ago, brother Weaver, looking up at the windows of the hotel, remarked, in very sad, solemn tones, to Brother Jones and myself, that the last time that he slept in that hotel the landlord's wife occupied his apartment. Of course I was startled, not to say shocked. Brother Jones, too, was much excited, and both of us listened intently to Brother Weaver's reply when I asked him if it were possible that I heard aright. He answered, "Yes, my brethren, it is my duty to tell the truth and whatever you may think, and whatever the consequences, I must repeat that what I have stated is true. The last time I occupied an apartment in that hotel the landlord's youthful wife was my companion."

" 'Brother Weaver's face, while this speech was uttered by him, was expressive of profoundest melancholy.'

" 'And I am persuaded,' continued Brother Williams, 'that he was moved to make this painful confession because the face of the Lord was never more patent in His goodness and heavenly benefactions than when it shone upon us this morning in the gorgeous sunlight that suddenly flooded plains, hills, and mountains. It rolled and fell like a brilliant Niagara of jewels and gold from the summit of the mountains yonder into this deep, beautiful valley. Clinch River, my brethren, shone lustrously as burnished silver, and the very splendors of the morning and pearly brightness and purity of skies overhanging this matchless land of beauty and blessedness were eloquent of God's goodness and suggestive of man's penitence. Brother Weaver, I am sure, could not withstand the force of nature's persuasive eloquence; and coming, as he was, to God's temple, he was moved to make this painful confession of his heinous crime.

" 'I appeal to Brother Jones, who accompanied us, to attest the truthfulness of my statements.'

"Williams sat down and Jones, an illiterate circuit-rider, rising, slowly and timorously said:

" 'Brethren, all that you have hearn is only too true,' and his eyes filling with tears, he used his handkerchief, and hesitating, stammering and weeping, was at last enabled to drawl out in broken accents, 'I hope, my brethering you will deal leaniently with Brother Weaver. The flesh you know is weak and Brother Weaver has repented. I know he has because he has confessed.'

"A torrent of tears swept down Jones' rugged features and with an audible groan he dropped, like a dead man, on his seat, utterly crushed by the weight of this unspeakable sorrow.

"Profoundest silence reigned, broken by sobs and groans of miserable and sympathetic Brother Jones. No assembly, christian or heathen, was ever more profoundly shocked. Women of the congregation, nervously excited, grew pale and haggard. The face of the Bishop's venerated wife was of ashen hue. Weaver was the flower of the flock of young preachers.

"At last the Bishop rose and said:

Page 34

" 'Brethren, you have heard, with horror and dismay, statements made by our two young brethren. I see Brother Weaver there, his head bowed beneath the weight of shame and penitence. Will he not speak? Has he nothing to say?'

"The Bishop resumed his chair.

"Slowly, most deliberately, and with an irrepressible twinkle in his clear, bright eyes, Brother Weaver, drawing himself up by the back of the seat before him, rose to confront the eager gaze of the excited assembly. He stood some moments looking sorrowfully over the throng gazing intently into his attractive, but saddened, solemn face.

" 'Brethren,' he said at last, 'I did make the confession which my friends heard and have accurately repeated; but it so happens that when I occupied the room mentioned, with the landlord's wife, as stated, I was the landlord, and the woman was my wife.'

"The true state of the case was slowly comprehended by the duped and stupefied multitude. The Bishop and his wife were first to discover the immaculate innocence of the two circuit-riders, Williams and Jones, and a broad smile spread over the kindly face of the godly man. His fat wife began to laugh immoderately. The infection spread, and when it had grown into a great roar the lantern-jawed, solemn, weeping Jones sprang up in evident disgust and exclaimed:

" 'Sold! awfully sold! Weren't we, Brother Williams?'

"This outburst of the mortified Jones, who had wasted bitter tears and sweetest sympathy upon Weaver, perfected the sudden revulsion from profound sadness and solemnity to an apprehension of the absurdity of the facts and their utter incompatibility with the seriousness of the place, day, and occasion. The Bishop's fat wife crammed her handkerchief into her mouth and the Bishop himself, contemplating the vacant look of empty astonishment that overspread Jones' heavy face, who seemed to ask himself, 'How could I have been such an arrant fool?' was wholly overcome. He caught a glance from the tearful eyes of his agonized wife and could contain himself no longer. He threw his head backward, clapped his hands to his sides, and roared with laughter. I never saw a religious assembly, on the Lord's day, in such a deplorable, unseemly condition.