RECOLLECTIONS AND

REFLECTIONS:

An Auto of Half a Century and More

Electronic Edition.

Green, Wharton Jackson, 1831-1910

Funding from the Library of

Congress/Ameritech National Digital

Library Competition

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Heather Bumbalough

Images scanned by

Heather Bumbalough

Text encoded by

Carlene Hempel and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1998

ca. 800K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1998.

Call number CB G79g 1906 (North Carolina Collection, UNC-CH)

The electronic edition

is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project,

Documenting the American South, or,

The Southern Experience in

19th-century America.

Library of Congress Subject Headings,

19th edition, 1996

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined

to the preceding line.

All quotation marks

and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded

as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as '

and ' respectively.

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text

using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word

spell check programs.

-

LC Subject Headings:

- Green, Wharton J. (Wharton Jackson), 1831-1910.

- North Carolina -- Biography.

- Soldiers -- North Carolina -- Biography.

- Confederate States of America. Army. North Carolina Infantry Battalion, 2nd.

- North Carolina -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives.

- Prisoners of war -- United States -- Biography.

- Johnson Island Prison.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Prisoners and prisons.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives, Confederate.

- West U.S. -- Description and travel.

- 1998-10-23,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1998-10-19,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1998-10-14,

Carlene Hempel,

finished TEI/SGML encoding.

- 1998-09-28,

Heather Bumbalough,

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

RECOLLECTIONS

AND

REFLECTIONS

AN AUTO OF HALF A CENTURY AND MORE

BY

WHARTON J. GREEN

PRESSES OF

EDWARDS AND BROUGHTON PRINTING COMPANY

1906

Page 5

DEDICATION.

To God's noblest handiwork and true men's highest conception of ideal perfection, a good, well-balanced woman, true in all the relationships of home and domestic life, and as little deficient in social intercourse with the outside world beyond, pious without pretension, erudite without pedantry, charitable without parade, soft of speech but duly assertive, stickler for the social proprieties but void of prudery, ever genial but never frivolous; - such is an imperfect pen- portraiture of a few of the amiable and lovable traits of one seen in my mind's eye and the one best known in actual life. It is my blessed privilege to have undisputed ownership to such a priceless treasure. Yes! to thee, Adeline, wife of my bosom and solace of declining age, at this the terminal period of "the fitful dream," I pledge renewed troth, and say, as Ferdinand said to Prospero's daughter in the incipiency of new-born love, -

* * * * for several virtues

Have I liked several women; never any

With so full soul, but some defect in her

Did quarrel with the noblest grace she owed,

And put it to the foil: But you, O you,

So perfect, and so peerless, are created

Of every creature's best.

To thee, dear wife, is dedicated this, my initial and, most probably, ultimate book.

Page 7

PREFACE.

On this, the initial day of a new-born century, I begin a work long held in contemplation, namely, the compilation of the Memoirs of a somewhat eventful life of a commonplace sort, covering the greater part of the century just ended; historically speaking, the most eventful of all the centuries. Probably, no epoch of like duration is more replete with books of a reminiscent character.

To avoid the suspicion of presumption in venturing to launch a new book of a similar sort upon an already over-booked era, be it known from the start, that the self-imposed task is not essayed for futurity, finance, or ephemeral fame. Hence, neither maelstrom, nor iceberg, nor hidden shoal holds out terrors for my puny venture. True, it is intended for posterity, but posterity in a very restricted sense - my own and that of kindred, and of a few tried friends, who have urged the undertaking. If some of these may, perchance, find a kernel of profit out of the mass of chaff attendant, my idle half-hours in the postmeridian of life will not have been entirely misspent.

Apropos of books of a reminiscent character, it is a crude opinion of mine that only two classes are entitled to write them, namely, those who have made history themselves, or those who have been brought in close contact and acquaintance with the class who have. Of right to write by rule prescribed, I make no claim, and abjure all pretension on basis number one. On that of number two, I think I may, without incurring the suspicion of vanity or arrogance, jot down some few of many reminiscences connected with illustrious personages, for it was my proud privilege to be brought in close touch with many of them.

Page 8

Conspicuous amongst these, in boyhood and maturer age, was a quartet, or rather quintet, of world-recognized gentlemen and historical heroes. I knew and honored and loved them, each and all, and thank the Master that it was my blessed prerogative to have been born of their tribe and racial line of thought. By name, they are known as John C. Calhoun, Andrew Jackson, Jefferson Davis, Albert Sidney Johnston, and Wade Hampton. Others there were, fitting compeers of even such as these; but, as I am essaying memoir only, - not history, - they are not mentioned by nomenclature. The Muse of History will, doubtless, align with the others Robert E. Lee, Thomas J. Jackson, and Nathan B. Forrest, only the first-named of whom was known to me personally, and but slightly; the last so casually as not to justify the claim of acquaintance on my part, and the second, not at all. Hence this reticence. Booked they all are for highest niches in "Walhalla."

In discussing this batch of "preux-chevaliers," and others of kindred soul but less resplendent lustre, as well as others still, who can set up no claim to kinship with such immaculates as these, it is proposed to do so fairly and dispassionately, but with no mawkish observance of the classic adage - "De mortuis nil, nisi bonum." If allusion is made to such as Nero, Caligula, Commodus, or Domitian, in an earlier age; or to Alva, Jeffreys, or the Guises, in more recent times, chance position of the culprit will not restrain anathema, or rather, harsh criticism. Silence is sometimes culpable. "The rank is but the guinea's stamp; a spade's a spade, for all that." Some have deemed me aforetime too plain of speech, in not calling that useful implement by a more euphemistic synonym. To such, the reply is that having used unvarnished old English up to the allotted span of man, it is now too late to acquire a modulated and more euphonic dialect in dealing with knaves, shams, and pretenders.

Page 9

If there is any merit in my desultory writings, having been a scribbler off and on through life, it consists in thorough conviction and pointedness of expression. Those who object to that style might as well close the little volume. Rosewater and diluted catnip is repugnant to taste, and unsuited to my genius. The field is already overcrowded with that sort, men who shun a positive, unequivocal expression of opinion on men, measures, and policies, as they would a bolt from a catapult.

January 1, 1900.

Page 11

TABLE OF CONTENTS.

- CHAPTER I.

Birth, Genealogy, and Earliest Childhood Days - Loss of Mother When

Four Years Old - Transference to Home of My Uncle Joseph P.

Wharton, near Lebanon, Tenn. - Early Terrors: Pedagogues,

Pinafores, and Apparitions . . . . . 1

- CHAPTER II.

Proclivity for Field Sports - How I Came Into Possession of My Cousin

Bob's Hounds Later On - Measles and the Tender Passion: First

Attack of Each - Meeting with My Father, After a Ten Years

Separation . . . . . 21

- CHAPTER III.

Visit to the Sage of the Hermitage: His Impressibility - Subsequent

Visit to the Same Spot with His Adopted Niece, Mrs. Mary

Donelson Wilcox . . . . . 24

- CHAPTER IV.

Sketch of My Father, Thomas J. Greene, from the N. C. University

Magazine, 1892 - His Early Political Bias and Predilection - His

Subsequent Romantic History - Author of the Bill in the Texan

Congress, Making the Rio Grande the Boundary Line Between Texas

and Mexico, which Resulted in the War with Mexico and the

Acquisition of Texas and Boundless Territory Further West - Journey

from Nashville to Washington - Remarriage of My Father - Dr.

Branch T. Archer, Father of the Texan Revolution, a Remarkable

Man . . . . . 30

- CHAPTER V.

In Louisville - Division of the Methodist Church and Sectional

Divergence - In Washington, the Straggling Village - Visit to

Paternal Grandmother - Return to Washington - Dr. Branch T.

Arthur, the Instigator of the Texan Revolt Against Mexican

Tyranny - John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis . . . . . 45

- CHAPTER VI.

In Georgetown College - Contempt of Academic Laurels - How to

Succeed: Crawl, Creep, Cringe . . . . . 54

Page 12

- CHAPTER VII.

My Father's Second Wife - The Little Girl who Became Wife:

Her Training and Disposition; Her Love and Loyalty; her

Death . . . . . 59

- CHAPTER VIII.

In Lovejoy's School - Transferred to Boston - An Inspiring Teacher

- Admitted to West Point; Class of 1850; Distinguished Classmates -

War Reminiscences - West Point Instructors - Colonel Lee a

Peacemaker - Social Life . . . . . 63

- CHAPTER IX.

Resignation from the Academy - Sheridan and Schofield - At the

White Sulphur Springs - Duelling Pistols and the Duello - A

Trip to Kentucky and a Bit of Romance - At the University of

Virginia - Some Professors - Literary Society Experiences - The

Fateful Numeral One . . . . . 92

- CHAPTER X.

Admitted to Practice Law Before the Supreme Court of the United

States - From Washington to Texas - Rattlesnakes, "Northers,"

and Hospitality - San Antonio - Desperadoes - Distinguished

Soldiers . . . . . 109

- CHAPTER XI.

Albert Sydney Johnston, an Excerpt from the Biography by His

Son, Col. William Preston Johnston . . . . . 124

- CHAPTER XII.

"Bigfoot Wallace" - Anecdote of Bedford Forrest - A Hunting

Excursion . . . . . 129

- CHAPTER XIII.

Marriage and Bridal Tour - In the Land of the Pharoahs - European

Travel - Home Again - War - Military Experiences - My Body-servant

Guilford . . . . . 140

- CHAPTER XIV.

The Fortunes of War - The Epoch of Self-sacrifice - Wounded - With

the Invading Army - Wounded and a Prisoner of War - Life on

Johnson's Island . . . . . 164

Page 13

- CHAPTER XV.

Exchanged - The South is Vanquished - In Politics - Elected to

Congress - Some Reminiscences . . . . . 194

- CHAPTER XVI.

A Trip to the Pacific Coast - Home Again - Closing Reflections . . . . . 204

- APPENDIX.

Letter from Jefferson Davis - Letters to the Boston Herald, Written at

Venice, Naples, Rome, and Thebes - The Second N. C. Battalion -

Address on General Robert Ransom - West Point Then

and West Point Now - A Paper on Jefferson Davis - Address Before the

J. E. B. Stuart Chapter, U. D. C. - Gettysburg - Memorial Address in

Honor of Mrs. Davis - Speech in the House of Representatives on the

Adulteration of Food and Drugs . . . . . 223

Page 14

Birth, Genealogy, and Earliest Childhood Days - Loss of Mother When Four Years Old - Transference to Home of My Uncle Joseph P. Wharton, near Lebanon, Tenn. - Early Terrors: Pedagogues, Pinafores, and Apparitions . . . . . 1

Proclivity for Field Sports - How I Came Into Possession of My Cousin Bob's Hounds Later On - Measles and the Tender Passion: First Attack of Each - Meeting with My Father, After a Ten Years Separation . . . . . 21

Visit to the Sage of the Hermitage: His Impressibility - Subsequent Visit to the Same Spot with His Adopted Niece, Mrs. Mary Donelson Wilcox . . . . . 24

Sketch of My Father, Thomas J. Greene, from the N. C. University Magazine, 1892 - His Early Political Bias and Predilection - His Subsequent Romantic History - Author of the Bill in the Texan Congress, Making the Rio Grande the Boundary Line Between Texas and Mexico, which Resulted in the War with Mexico and the Acquisition of Texas and Boundless Territory Further West - Journey from Nashville to Washington - Remarriage of My Father - Dr. Branch T. Archer, Father of the Texan Revolution, a Remarkable Man . . . . . 30

In Louisville - Division of the Methodist Church and Sectional Divergence - In Washington, the Straggling Village - Visit to Paternal Grandmother - Return to Washington - Dr. Branch T. Arthur, the Instigator of the Texan Revolt Against Mexican Tyranny - John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis . . . . . 45

In Georgetown College - Contempt of Academic Laurels - How to Succeed: Crawl, Creep, Cringe . . . . . 54

Page 12

My Father's Second Wife - The Little Girl who Became Wife: Her Training and Disposition; Her Love and Loyalty; her Death . . . . . 59

In Lovejoy's School - Transferred to Boston - An Inspiring Teacher - Admitted to West Point; Class of 1850; Distinguished Classmates - War Reminiscences - West Point Instructors - Colonel Lee a Peacemaker - Social Life . . . . . 63

Resignation from the Academy - Sheridan and Schofield - At the White Sulphur Springs - Duelling Pistols and the Duello - A Trip to Kentucky and a Bit of Romance - At the University of Virginia - Some Professors - Literary Society Experiences - The Fateful Numeral One . . . . . 92

Admitted to Practice Law Before the Supreme Court of the United States - From Washington to Texas - Rattlesnakes, "Northers," and Hospitality - San Antonio - Desperadoes - Distinguished Soldiers . . . . . 109

Albert Sydney Johnston, an Excerpt from the Biography by His Son, Col. William Preston Johnston . . . . . 124

"Bigfoot Wallace" - Anecdote of Bedford Forrest - A Hunting Excursion . . . . . 129

Marriage and Bridal Tour - In the Land of the Pharoahs - European Travel - Home Again - War - Military Experiences - My Body-servant Guilford . . . . . 140

The Fortunes of War - The Epoch of Self-sacrifice - Wounded - With the Invading Army - Wounded and a Prisoner of War - Life on Johnson's Island . . . . . 164

Page 13

Exchanged - The South is Vanquished - In Politics - Elected to Congress - Some Reminiscences . . . . . 194

A Trip to the Pacific Coast - Home Again - Closing Reflections . . . . . 204

Letter from Jefferson Davis - Letters to the Boston Herald, Written at Venice, Naples, Rome, and Thebes - The Second N. C. Battalion - Address on General Robert Ransom - West Point Then and West Point Now - A Paper on Jefferson Davis - Address Before the J. E. B. Stuart Chapter, U. D. C. - Gettysburg - Memorial Address in Honor of Mrs. Davis - Speech in the House of Representatives on the Adulteration of Food and Drugs . . . . . 223

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

- W. J. GREEN . . . . . Frontispiece

- "SUGAR TREE GROVE" . . . . . 16

- GENERAL THOS. J. GREEN . . . . . 30

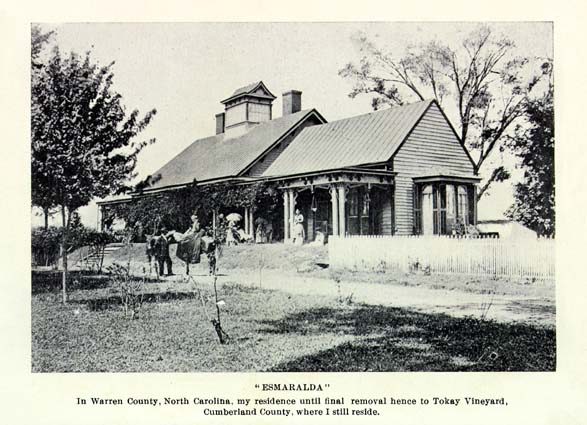

- "ESMARALDA" . . . . . 42

- "JAMACIA PLAINS" . . . . . 58

- GENERAL ALBERT SYDNEY JOHNSTON . . . . . 124

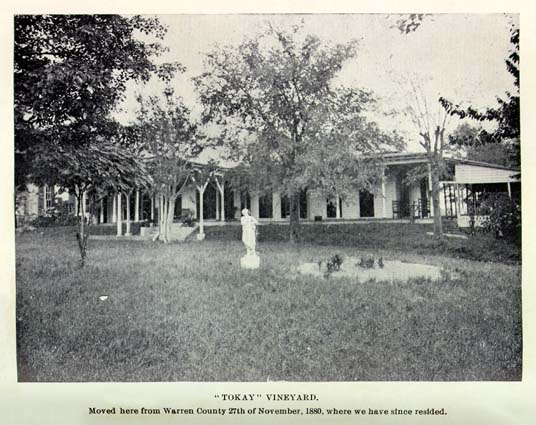

- "TOKAY" VINEYARD . . . . . 196

- GENERAL WADE HAMPTON . . . . . 200

- JEFFERSON DAVIS . . . . . 224

Page 15

CHAPTER I.

BIRTH, GENEALOGY, AND EARLY CHILDHOOD.

While making no claim to merit on the line genealogic, still I am not debarred, by excessive modesty, from saying that my forbears are of good, honorable, and unblemished record, running back more than a century in this country and embracing six or eight generations of "traceable grandfathers," both on the paternal and maternal side of the house. Many of them were of marked name, trait, and characteristic, and none ever false to himself, his blood, or his manhood, as far as my researches go. The fountain source of migration was, in every instance, "English, pure and undefiled," for which Heaven be praised. There was not a Tory in the stock in the Revolutionary War, nor a traitor or renegade to the South in the "War between the States"; very few of these last since then. All branches flowed from Virginia and North Carolina into Tennessee, where concentration set in, towards the close of the eighteenth century. As a rule, they were ever planters and tillers of the soil, although some few sided off into professional and mechanical pursuits. Such is a simple and succinct statement of family history. It is one of which no scion of any house in this broad land could be ashamed. Let him, who can match it, say "Laus Deo!" in all fervor.

My father, Thomas J. Green, of Warren County, North

Carolina, afterwards General Green of Texan Revolutionary

fame, married my mother, Sarah A. Wharton, of Nashville,

Tennessee, on January 8, 1830. She was the daughter of

Honorable Jesse Wharton, at one time United States Senator in

Congress. They moved to his plantation, near St. Mark's,

Florida, where I was born on February 28, 1831. By death I

sustained the irretrievable loss of this last dear parent on

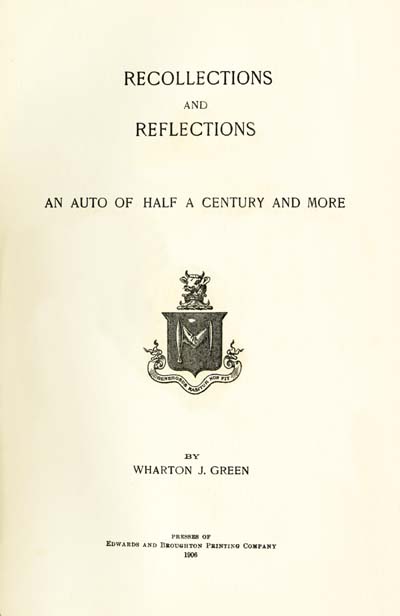

"SUGAR TREE GROVE"

The residence of my great grandfather, Joseph Phillips, six miles form Nashville, Tenn., which he settled and built in

1791. He and his wife having traveled from Edgecombe County, North Carolina, the seat of their respective families by

wagon and located this spot which is still owned by one of their granddaughters, Mrs. Margaret Polk. Their progeny

to-day by close computation numbering between four and five hundred.

Page 16

March 11, 1835, being thus deprived of her ministering care at the early age of four years. She had met with the same great affliction when barely one year old. She was only twenty-three, and her mother twenty-six, at the time of death. The thought that oft recurred - would I not have been a better man had her life been spared a few years longer? Not that I have any right or cause to complain of the dear hands that received me. On the contrary, never did motherless waif pass into gentler and more considerate keeping. A few lines descriptive of this peculiarly interesting couple (my uncle, Joe Wharton, and his wife, Caroline) will not be out of place. They had married about the time that my parents did, and had the incipiency of a young family, which later on increased to large proportions. Two of their sons, and a son-in-law, died fighting for liberty, and the regret of both was that they could not duplicate their tender to the Cause. They took me into their house as if I had been one of their little fold, and for the nine or ten years succeeding accorded precisely the same. May their souls rest in peace, and their reward be commensurate to their unpretentious good works. Fortunately, they were well to do. A thousand broad acres of as inviting land as Middle Tennessee contains was their abiding-place, with forty or fifty sleek, overfed, contented negroes to cultivate them. The recollection of that home and the blessed spirit pervading it is a veritable dream of Arcadia.

Every thing used on the place was raised or made on the place, except sugar, coffee, powder and lead, and a few woman's fixings. The men-folk dressed in homespun, and were well content to get it. With no attempt at ostentation or display, they were nevertheless the most bountiful livers for their means, and in their simple way, that I have ever known. Hospitality was a synonym for home, the latchstring being ever on the outside of the door. In those blessed days, there were but few things to cause pain or occasion

Page 17

trouble. Primarily of these were, by alliteration, pedagogues, pinafores, and apparitions. Especially was the pedagogue my pet abomination, being almost ever of the genus ignoramic, tyrannic, or pompostic, individually, or in combination. Being a tyrant hater by nature as well as by inheritance, one of my grandfathers having been of that honorable Commission of Forty (afterwards known as "Regicides") that cut off the head of one Charles Stuart, about the last of that crown-wearing tribe of tyrants in England. God be praised both the sceptre-bearing and rod-wielding specimens of the vile tribe are fast becoming extinct. Tyranny has had its day!

Dionysius, the historic tyrant, is dead; and so is his pedagogic successor, Dionysius, the terror of schoolboys. I write feelingly in behalf of the boy to be, having been a boy myself, under that merciless regime. They all seemed to have a special hate against me, and, to be candid, there was little love lost between us, as certified by old smarts and long-dormant grudge for having received them for nothing. Unfortunately, the other fellow had 'whip hand,' and 'hinc lachrymae.' But there was one day when the boys would get the upper hand of the dominie, and that was "turning-out" day of blessed memory. (See Judge Longstreet's description in "Georgia Scenes.")

My father left a young negro woman, Lucinda by name, to wait on me in my juvenile years. She had been my nurse, and was devoted to me, but, unfortunately, her head was full of African 'folk-lore' and superstitions, in which the horrible predominated, all of which naturally passed into my own cranium. Being of a credulous and impressive temperament, they made a most baleful and baneful impress on the imagination until nine or ten years of age, especially when having to sleep in a room by myself. Many a night in mid-summer have I slept with head under blankets to shut out a

Page 18

devil's 'high carnival' in dread apprehension. It is easy to look back and smile at these fancies and conjurations of juvenile years, but at the time it was no laughing matter, but veritable purgatorial torture. I sincerely trust that few boys or girls have ever suffered a tithe as much in those tender years. To make the hallucination utterly inexplicable in my case, it was notorious that I could "lick" any boy in school though my superior by long odds in pounds, inches, and age. This, perhaps, was at times needlessly done to convince myself that I was not a coward for standing in such mortal terror of the devil and his imps, and rawhides and bloody bones. More singular still, I didn't believe in that absurd phantasmagoria any more then than to-day. This is the honest experience of a lad who was, and admits he was, afraid of ghosts and goblins, and yet did not believe in their existence. What a strange anomaly the mind is any way.

Now for the third, and last, misery of my boyhood life at that early stage, - 'pinafores.' At the time of beginning life in this rustic paradise, there was left an elaborate supply of juvenile toggery, appropriate to a picnic or a Sunday-school, but entirely out of place in a day-school for country children. This I realized very early, and importuned raiment befitting surroundings. My aunt, however, being of a frugal mind, thought it expedient that they should be worn before outgrown. As they invariably exhibited a soiled and battered show-up after school was out, she concluded to add checked aprons to the 'get-up,' as a sort of armor-protector. An extra fight or two for days succeeding, for the twit of being 'a gal,' led to the conclusion, on my part, that this addendum in raiment was not suited to my 'style of beauty.' And so they disappeared, to be substituted by a 'dressing' of another sort on reaching home. My aunt, though later on a 'rebel,' so-called, herself, was not prone to tolerate rebellion to established authority in her little domain. And so the contest continued

Page 19

between us, day after day, until the supply of the obnoxious things was exhausted, or else the dear good soul's patience and powers of endurance. It seems to me, after these long years, that she tacitly called a truce. Certes, there was no 'Appomattox' for me in that momentous struggle for the 'Rights of Man.'

It was a miniature prelude to another struggle soon to follow on a far more extended scale. I know that my aunt thought she was right in this needless assertion of prerogative, for she never did a thing in her blessed life that wouldn't stand that primary test. Perhaps, too, Bill Seward and his puppets thought the same in their sublime assertion of prerogative. And yet, is it not barely possible that each might have been slightly out of reckoning? I could not help thinking then, and still maintain, that it is a desecration to try to turn a boy into a girl or a dude. Not that girls are not an essential factor in the world's economy and make-up; but still, no true boy wants to be one, much less that nondescript other thing. Let it be said, that those are the only whippings this my second mother ever gave me, with the exception of an occasional one for a Sunday fishing escapade. Uncle Joe never struck me a lick in his life, that comes to recollection, probably thinking I got my full complement at school. Be it said, that whilst pedagogic brutality was sometimes met by puny and impotent resistance, I always took my Aunt Caroline's corrections like a little man.

And so the period of first boyhood passed by, and the tenth year beginning, say, the secondary period came on. By that time I was a strong, robust, double-jointed specimen of juvenile humanity. Am glad to say my constitution, by that time grounded, was strengthened by the next four or five years of active outdoor exercise, riding, hunting, fishing, etc. My health has always been exceptionally good, up to the near

Page 20

approach of the Biblical limit of the years of man's pilgrimage. At least, it was so until this vile imported foreign disease, called 'La Grippe,' put in an appearance a year or so ago. That has not only impaired physical stamina, but worse by far, changed a disposition naturally gentle, forbearing, and amiable, into the morose and melancholic order. Never thought it would please me. The orthography is too Frenchy for the ear of an Englishman.

Page 21

CHAPTER II.

The second stage of these puerilities naturally calls for a new chapter.

My Uncle Joe was an inborn sportsman, one of the finest shots, both with the rifle and shotgun, that I have ever known. In due time these were permitted me to use, glorious privilege that it was. He was the owner likewise of one of the finest packs of hounds in Tennessee, and one of the highest delights in life was to follow them in his company. Those dogs in after years became my sole and exclusive property by deed of gift from his son Bob, who was not averse to becoming the son-in- law of one of the largest sheep raisers in the country, who naturally had a repugnance to the whole canine family, both of high and low degree. Alas! poor Bob, after sacrificing his pets to propitiate the father, failed to win the consent of the daughter, thus losing "Tray, Blanche, Sweetheart, and all." Cousin Robert had my heartfelt sympathy, especially for the loss of 'Sweetheart,' but when he asked for a cancellation of the aforesaid deed, I couldn't see it. Poor Bob, it is too mean to spring the story on you at this late day, but it was too good to keep all to myself. Still, in this sad, sad tale may be seen confirmation of the old saw - "Patient waiters are no losers." Though Robert never fed his father's flocks on the Grampian Hills, he, nevertheless, married one of the finest and finest- looking women in all those parts, and can count a round baker's dozen of boys and girls around him, whom he and his good wife can call their own.

Up to that date I had escaped juvenile ailments, including the tender passion and the measles. Exemption from the first was probably due to native bashfulness and dread of 'strange creatures.' Next to a lean, lanky, bonified ghost, nothing was so terrible as a fat, laughing, romping, rosy-cheeked

Page 22

girl. They seemed to know, by instinct, that they had me 'hacked,' and it was their delight to play on my fears. And yet, it was only a vague, ill-defined apprehension at the bottom. The thought never occurred that they would bite me any more than that demons would rend me, but they scared all the same. The incipient sisterhood ought to know better than to make sweet faces and frighten poor innocent lads.

But the measles! The whole school had it and could stay at home, but it was not for me to take it.

When the tender passion did awake, each attack was of a virulent type, the first love-spell especially. It came on in the fourteenth or fifteenth year. By the way, the incertitude as to precise dates of important events here shown is a fact that is going to give trouble in the furtherance of this self-imposed task, never having kept a connected diary as every boy and girl, and man and woman, should. But to return to my first love. "Inamorata" had the advantage by about a dozen years. It was a case of unrequited affection. She treated me meanly. Of course, such ill-mated ardor had to find utterance by the mouth of the ink-bottle. Yes, let it be confessed, I wrote her, aye, in burning words, telling of never having loved another, and of unalterable devotion to her. Either through the direct agency of that superannuated young female, or by surreptitious means, to me unknown, that billet-doux passed into the hands of all others most objectionable, those of my paternal ancestor. Perhaps, he didn't make himself merry, and me miserable, by reference to and quotation from that injudicious and ill-starred epistolary effusion. These were usually of the merry twinkle of the eye sort of order, but none the less galling. It cured me of love letters for a long time to follow. Moral: "Boys, do not write them; girls, do not answer them; and thus the evil will be cured."

Page 23

A mile from the house was the millpond, replete with fine perch, and it afforded endless enjoyment, for I have ever been a devotee of the rod - of the fishing-rod, be it understood.

And so the world sped on for nine or ten years after entering this ideal home of boyhood. One day, on returning from the creek, soiled, wet, barefoot, coatless, a stranger met me on entering. He was one of the most superb specimens of manly good looks that I had ever seen up to that time, or have ever seen since, and most faultlessly attired. He looked the soldier in every lineament, movement and gesture, and as one born to command. He was my father, and embraced me warmly. Kiss me, he did not, and never did, but taught me to despise that mode of salutation between men as effeminate and savoring too much of the Latin races, none of which stood high in his estimation.

A separate chapter will be devoted to General Green later on.

Page 24

CHAPTER III.

The next day saw me in the hands of the village tailor.

After emerging, I hardly knew myself, or was recognizable to others, such a complete transmogrification having been wrought in the outer man. The day after, I made my entry into the wide, wide world beyond.

After mutual lamentations between my aunt, the children and myself, my uncle having walked off a piece, we started to Nashville, thirty-three miles off, by hired conveyance. Eighteen miles from Lebanon stands "The Hermitage," the home of one of the grandest and most remarkable men of this country and century, or those of any others. General Green had been a favored young friend of the grand old man in his earlier years, and had spent some time as his guest. His admiration for him was so great that he bestowed the name of the old hero on me, his only child. Note. This I continued to bear until the Nullification and Force Proclamation induced us both to reflect that it would be as well to substitute for the old gentleman's first name (Andrew) my mother's maiden name Wharton, which has clung to me ever since. That political blunder of his was the only act that we deplored.

Of course, there was no passing such a spot without stopping. On being told that the General was still in bed, my father told the servant not to disturb him, but to give his card on arousing. As we were starting back to the vehicle, the servant rushed back exclaiming: "Master says don't go, but come right in." Be it said that for this deviation from the rule against seeing visitors, the great question of Texan Annexation was then just in the bloom, President Polk having been installed in office only a month before. His great predecessor was so deeply absorbed in this momentous issue that,

Page 25

although only six weeks from the grave, he had himself helped up and arrayed in his morning gown, seated in easy chair with pipe lit, and talked by the hour on this matter nearest his heart with one fresh from the Lone-Star Republic, and presumably posted on the drift of opinion in that quarter. Here was illustration of the old saying - "The ruling passion strong in death." One remark impressed me: - "Let me live to see that consummated, and I can depart in peace." Other things he said that still remain on memory's tablets.

After a while, as illustrating his proverbial politeness and consideration for others, evidently thinking the conversation was dull to a boy, he sent for one of his young kinsmen of about my age (if not at fault his grandson and namesake), and told him to take me in the garden and show me the flowers. He showed more, namely Aunt Rachel's and Uncle Andrew's graves, side by side, and covered by a little summer-house-like structure. "But the General isn't dead," I put in. "All the same," was the reply, "but he wanted to have it this way, and you know he has always had his own way." To this I assented with the after-thought of after-years - "except when Aunt Rachel put in her mild veto, supplemented with tears." God bless them both! for the "give-in," on such occasions, of that iron, and otherwise inflexible, will.

On taking leave, he placed his hands upon my head, and gave me his blessing. Later on in life, two others of the world's celebrities did the same, barring the manipulation, thus wise.

As we were returning from a country-drive one afternoon in Rome, we met the head of a pontifical cortege in carriages, returning from some church festival or other religious duty. Being in Rome, etc., I naturally conformed to the customs of Rome, alighted, and stood uncovered until the carriage of Pio Nono had passed. To our surprise, it stopped abreast, and

Page 26

the venerable Pontifex Maximus, for whom I have ever since felt the highest respect, had his driver stop, and, leaning out of the window, bestowed the "benedicite" (if correct in Church nomenclature), and moved on. Whether that good old man's good wish has kept me immune from the ills of life, I am not prepared to say, but appreciate the force of the great Hildebrand's reproof to the stiff-necked and stiff-kneed young Englishman, who refused to kneel at High-Mass in St. Peter's: - "My son, the blessing of an old man will do thee no hurt."

The third instance apposite was at "Beauvoir," Mississippi, of which more, perhaps, anon.

It would seem that I ought to have turned out to be a much better specimen than I have, after so much benediction from sources most highly appreciated, each world-mover, as he was. If the blessing of three such good old men as these availeth not to keep a poor wayward child out of the burning, then tell me not of a conjoint one of the whole College of Cardinals, with the eleven thousand virgins of Cologne thrown in for good measure.

On leaving that historic home of the most pronounced, not to say remarkable, character in American history, I could but remark on the judicious judgment in selection and the good taste in its development. Everything evinced the eye and touch of the natural artist in all of its concomitants and surroundings. The "Hermitage neighborhood" had long been a synonym for refinement, high tone, and hospitality, up to the outbreak of the war, as I can aver from frequent visits thereabouts later on in early manhood. The fertility of the soil and adaptability to agriculture were in keeping with those exalted traits of the owners. In the heart of that lovely region it was that the hero of the most wonderful battle, and one of the most unique and phenomenal careers on record, built his house and reared his beautiful and peaceful home in

Page 27

the latter part of one of the stormiest and yet withal one of the most uniformly successful lives, on a grand historic scale, that any man can point to.

His previous homes, from the one-room cabin in Western North Carolina, in which his grand old Irish mother had blessed the world at large, but more especially her newly adopted country, with a hero, a sage, a statesman, and, above all, a MAN. His homes, I say, and surroundings, had not been of the highest aesthetic type, but he was at home where-ever he was, from the aforesaid cabin to the Presidential mansion. He was a marked figure in every sphere and station of life. This power of adaptability to change of conditions and circumstances has been adduced by a great thinker as one of the most infallible proofs of inborn gentility, if not of highest order of genius. He was right, and here was an exemplar of the combination. Of him it may be said, if of any, - "And thus he bore, without reproach, the grand old name of gentleman"; the best definition of which rare character, as given by Thackeray, is - "It is to be gentle and generous, brave and wise, and having these qualifications, to exercise them in the most graceful manner." This he exemplified always, as Bayard might have done at times, Chesterfield never.

Of him was said by a newly arrived French ambassador: - "This, Mr. Secretary of State, is the surprise of my life. I went in with you expecting to find a boor in your Chief Magistrate, and I tell you now, in all soberness, that I know not his counterpart for refinement in the court of my own country." High praise that from a Frenchman.

In that lovely section of country, he drew around him on neighboring plantations many of his wife's kindred, having none of his own. These, and other congenial homes in the surrounding country, made it one of the most famous residential quarters in the entire country. Such was the fitting

Page 28

retreat of the old hero in the closing years of his most remarkable career. Here it was rounded off some six or eight weeks after the visit referred to, in peace and good will with all mankind, as he declared to his beloved pastor, Dr. Edgar, some time before the end came. No man ever had such hosts of warm, devoted friends, and few, such virulent and implacable foes. The first he owed to his undeviating sincerity, utter fearlessness, and devotion to duty, both public and private. The last were due, in great measure, to his self-assertiveness whenever his conscience told him he was in the right. Assertive he usually was when so convinced; needlessly aggressive, most rarely. Most marked instance of this last was his quarrel with a brother-giant, Mr. Calhoun, whose nature was cast in a kindred mould.

He ever met the puppy impertinence of "unworthies," whether on his own social plane or not, with silent and sovereign contempt, until it called for the cane, the cowhide, or the pistol. It must be confessed, too, that in his earlier manhood he fought cocks, raised and ran race-horses, and deported himself generally like an untamed young war-horse of the young country in which his lot was cast. But there was no duplicity or sniveling or hypocrisy in his make-up. He wore his badge upon his sleeve, and it bore the impress - "truth, courage, honor, country, charity," and his escutcheon was never belied. True, perhaps, at that stage he was not a model specimen of approved orthodox "high society," a "400" sort of artificial thing; but he was what that pack of popinjays could not evolve in a million years - a MAN, - such as the poet called for -

"Give me a man that's all a man,

Who stands up straight and strong;

Who loves the plain and simple truth,

And scorns to do a wrong."

There he was!

Page 29

The last time I visited this tomb of a hero was just three years ago, on the occasion of the Confederate Veterans' Reunion in Nashville, in 1897, in company of my wife, youngest daughter, and Mrs. Mary Donelson Wilcox of Washington, daughter of President Jackson's Private Secretary, Andrew J. Donelson, and the first child ever born in the White House. It was a privilege to have this accomplished woman for a cicerone midst the scenes of her girlhood days, replete with incident and childhood memories of Uncle Andrew. It was one of the mysterious charms that he possessed, that all children loved him after their brief acquaintance. He seemed to crave the company of the little ones, probably because he and Rachel had none of their own, and he, not a known relation in the world. The great man was lonesome.

Page 30

CHAPTER IV.

Perhaps, it may be said by some that the preceding chapter is a little too effusive in laudation of this extraordinary man. To such be it said, that the estimate given is the mature conviction of life-long reading and reflection in maturer years. In boyhood days, he was far from being one of my ideal heroes, for that period had been passed in the strongest Whig county, I believe, in the United States, where party passion ran to the highest pitch, and my juvenile mind had been unconsciously tinctured with antipathies against our neighbor, just over the Wilson border, closely akin to what had until lately been felt for the devil. And yet, here was a philosophic Warwick, who made Presidents and shaped policies, in his voluntary retiracy. Tell me not, ye partisan bigots, that this man was not a giant among giants. He stands on the historic scroll so inscribed, and all the puny malignity of partisan and sectional hate cannot wipe it out. In all reverence, be it said; God be praised, he was a North Carolinian.

I come now to speak of another character of kindred type, if not the same effulgent shine - my father.

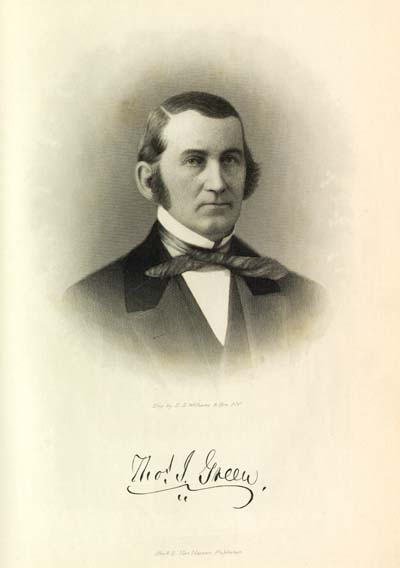

General Thomas Jefferson Green; a sketch from the North Carolina University Magazine, 1892, No. 5, by his son, W. J. Green.

Despite the possible imputation that praise of a near kinsman is only a sort of reflected self-laudation, I venture to give the outline of the life-story of my nearest male progenitor, premising that if space permitted a fuller recital, the lives of few would furnish more varied and startling incident.

To briefly summarize. In the fifteen years of his active

public life he had been a representative in one or the other

branch of no less than four different State legislatures, a

GENERAL THOS. J. GREEN

Page 31

brigadier-general in command during the Texan revolution, had laid the foundation of three cities now in train of full-fledged development, had by legislative enactment established the boundary line between Texas and Mexico, which led to the war between the United States and Mexico and the resulting acquisition by us of New Mexico, Arizona, California and Nevada; and was the first active advocate of a railroad to the Pacific, giving as reason imperative public necessity, gauged simply from a military standpoint, and without reference to the great East Indian trade, which has been the making (omitting unmaking) of every State claiming its monopoly. There is a record, and a sustainable record, of which no man need be ashamed.

Born amidst the throes of political revolution, of which Jefferson and Hamilton were the incarnate embodiment of antagonizing ideas, he received the name and espoused the teachings of the first, and clung to them with unwavering tenacity until his final dissolution amdist the mighty clash of arms resulting some three-score years later on. He ever held that his namesake was the wisest political thinker of all times, and that Mr. Calhoun was his worthy disciple. No public act of his did he ever deplore or deprecate, save his ungenerous persecution of a kindred intellect and on the same line of thought. Speaking of this last, self-poised and self-reliant, shipwrecked by emotional clamor and the force of circumstances, he has been heard to declare that "the best-directed bullet that ever left the mouth of a pistol was when Colonel Burr pulled trigger on the heights of Weehawken."

He once took that unfortunate gentleman as text to inculcate a lesson to me. "Whilst Colonel Burr pushed his contempt of invidious public opinion to a fatal extreme, I would nevertheless have you, my son, imitate him to the extent of not attaching undue weight to the fulsome praise of overzealous friends or the covert dispraise of inimical mouthers.

Page 32

He, whose life motto is 'mens sibi conscia recti,' will not be unduly elated or depressed by either."

He was partly educated at Chapel Hill, and partly at the United States Military Academy. Returning home, he was elected to the General Assembly shortly after attaining his majority. Shortly thereafter he married the daughter of Hon. Jesse Wharton, of Nashville, Tennessee, who had figured in both houses of Congress from that State. Thereupon he removed to Florida, then a territory, and engaged in planting until the death of his young wife five years later, having represented his county in the Legislature during that time. He thereupon repaired to Texas, which had lately declared her independence of Mexico, and tendered his services to the young republic, just then emerging into statehood. It is safe to assert that no corresponding population of any age or country ever possessed such a galaxy of adventurous, daring spirits, and brilliant, brainy, cultured men. They poured in from all sections and many countries, but notably from the Southern States. A common impulse actuated all, namely, to throw off the Mexican yoke and to erect a new republic identical with that on the other side of the Sabine.

When it is taken into account that the incipient State covered an area about seven times greater than North Carolina, and was occupied by a meager population, barely exceeding that of Wake County to-day, and that these had deliberately resolved to measure blades and try conclusions with an adjacent nation nearly two hundred to a unit in excess of numbers, the purpose ranks either as the superlative of madness or the sublimity of heroism. They dared to do it, and they did it.

Odds considered, it eclipses all the revolutions of antecedent time. Of course minimum in numbers had to be compensated by maximum in men, and so it was. There were no dwarfs or cowards there, but "men, high-minded

Page 33

men," and mostly of good old English stock. By any others the attempt would have been the acme of lunacy. Consider but a few of them, for small as their number was, it was too extended for a muster-roll. There was Branch T. Archer, "the old Roman," the father of the revolution; Albert Sidney Johnston, by a later war catalogued with the recognized few greatest captains of all time; John Wharton, "the keenest blade that flashed on the field of San Jacinto," and William, his well- mated brother; Mirabeau Lamar, statesman, soldier, poet, philanthropist, with inherent intellect permeating every drop of his blood. There was Felix Huston, of fame punctilious, and grand old Ruske, and Henderson, Hamilton, Houston, Burleson, Burnet, Hunt, Milam Travis, Crockett, Bee, Hays, McCulloch, Moore, Fisher, Sherman, Wilson, Anson Jones, Lubock, Smith, and a legion of others too numerous to mention - heroes, one and all.

"Souls made of fire, and children of the sun," were they, imbued with hatred of oppression and love of adventure. General (and afterwards Governor and Senator) Foote places the subject of this memoir in the forefront rank of those gallant spirits for services rendered his adopted country. (Vide "Texas and Texans.") We challenge any historic State, numbers considered, to mate at juncture that matchless chivalry in all the lofty attributes of true manhood. Let the slur of witlings be admitted that some there were in that heterogenous population "who had quit their country for their country's good." I, for one, will maintain, if need be, before a college of cardinals, that self- sacrifice that prompted the following of such as these condoned much previous offending.

Charity is first in the eye of the Most High. Where can higher illustration be found than in heroism which prompts self- immolation for principle and for posterity? Who knows that when the golden gates are being besieged by clamorous

Page 34

claim for admittance, "Goliad" and "The Alamo" will not constitute better passport to the sympathetic old janitor, who upon a generous impulse could chop off an ear, than will psalmody, unsupported by regard for the rights of others? I can but believe that Peter will strain a point when Crockett and Travis and Fannin knock.

Arriving in Texas in 1836, he was commissioned brigadier- general and directed to return to "the States" and raise a brigade. This he promptly did, absorbing his entire fortune in the effort. Whilst so engaged in New Orleans a ludicrous incident is reported to have occurred in one of the Episcopal churches of that city. There was a striking likeness between his kinsman, the Rev. Leonidas Polk, and himself. One Sunday some of his recruits chanced to stray into a church where the later-on fighting bishop was officiating. One of them, mistaking him for his senior officer, who was not over-clerically inclined, remarked, loud enough to be heard by most of the congregation: "Well, boys, who'd a thought it? Uncle Jeff a-preaching, and in his shirt-tail at that." It is needless to add that an unorthodox smile spread over the worshippers.

In the meanwhile the decisive battle of San Jacinto had been won against overwhelming odds, and the Mexican Generalissimo was a puling prisoner. Fate so ordained that General Green should arrive at Velasco on the identical day that Santa Anna was released and placed on a war vessel to be carried to Vera Cruz. General Green, believing this to be an unauthorized exercise of power on the part of some one, protested against its being carried out. Together with Generals Hunt and Henderson, under authority of President Burnet, he went on board and brought him ashore. This action was fully sustained by the government, and the tyrant was consigned to his custody for safe keeping. During the time, he was my father's guest and bed-fellow. When their relations

Page 35

were subsequently reversed, General Green was made to feel acutely his long pent-up venom. The Mexican assassin ordered him heavily ironed and made to work the roads. This last he emphatically refused to do, though threatened with death as the alternative. (See his Journal.)

For a while the young republic enjoyed comparative immunity after her big neighbor had been taught on the San Jacinto the sort of material she was made of. But later on Mexico relying on numbers and resources, and her President having partially recovered from his panic, incident to the San Jacinto 'grip' and consequent confinement, began his incursions again, and carried them on in a most merciless and demoniac spirit, scarcely equalled in barbaric atrocity by any civilized people since the devastation of the Palatinate.

Then it was, as if by common consent of the sturdy settlers; a counter-invasion was resolved upon. A force of two or three thousand was assembled, and all clamorous for retaliation. But, through executive, sharp practice and chicane, President Houston being opposed to the movement, the bulk of them was induced to disband and return to their homes. Some seven hundred, however, resolved to remain, and, under command of General Somerville, an appointee of President Sam Houston, crossed into Mexico. Their commander, however, imitating the King of France, marched over, and then marched back again. Then, under implied executive authority, he started homewards with something like one-half of his command.

Three hundred and four gallant fellows, however, refused to go, and determined to recross the Rio Grande and try conclusions on the enemy's ground. The battle of Mier was the consequence, in which two hundred and sixty-one (261) Texans, after inflicting a loss of over three times their number upon a force of two thousand three hundred and forty

Page 36

(2,340) under General Ampudia, were cajoled into a surrender by false claim and falser promise. It is well-established fact that General Green, the second in command, protested most loudly against such promise, and called for a hundred volunteers to cut their way through the enemy's lines. These not being forthcoming, he was surrendered with the rest, after firing with effect the two last shots and breaking his arms.

They were then started on foot for the Castle of Perote for safe keeping, that being the strongest fortress in Mexico; Colonel Fisher, General Green, and Captain Henrie as interpreter, being kept in advance as hostages for the good behavior of the others. When considerably advanced in the country, he found means to communicate with the command, and enjoined upon them to make a break if opportunity occurred, without regard to himself and the other two. This they did at Salado, overpowering and disarming a guard of more than twice their number, and started back for Texas. Subsequently they were recaptured in the mountains, in a starving condition and perishing of thirst. Then ensued one of the crowning infamies of Mexico's President - the tyrant, Santa Anna. By his bloodthirsty order, every tenth man of that little band of heroes was, by lot, taken out and assassinated. Upon receipt of news of it, a halt was called and the hostages told to dismount in order to carry out his orders to shoot them.

All preliminaries to the command "Fire!" being arranged, the captain, who was a devout son of the Established Church, bethought himself of one oversight. "Gentlemen," he said, through the interpreter, "would you not like priestly consolation before we part company?" "Tell him no," was my father's rejoinder; "that we belong to a race that knows but one Father confessor, and He seems to be unknown in this God-forsaken country."

Page 37

Being then asked if he would like to make a dying speech, the reply was: "Tell him yes, Dan, I have a dying speech to make; that I had begun to think we were in charge of a gentleman and a soldier, but now discover the mistake; that, like most of his mongrel race, he is only a d--d cowardly assassin and hireling butcher."

Poor Dan, who taught me Spanish a little later on, and who was by act of the United States Congress a little later recognized hero of "Encarnacion," was of incalculable service to General Taylor on the eve of Buena Vista, by information conveyed by him by means of one of the most reckless escapes ever made after that surrender. The incident deserves more than passing notice. Captain Henrie (Dan) was an ex-midshipman in the United States navy, and laughed at danger as he did at most other things. He was amongst the first to volunteer in the Mexican war, giving as a reason that he intended "to get even with the green-backed mulattoes over the Grande." When Colonel Clay's command, on advanced service, was surrounded and captured at Encarnacion, Dan was of the number. General Ampudia, recognizing him, remarked: "And so, Captain Henrie, we are to have the pleasure of your company back to Perote!" "Excuse me General," was the saucy reply; "when I travel I generally select my own company." The Colonel, who was riding a high-mettled thoroughbred by courtesy of the captor, rode up to Dan shortly after the march was begun, and told him in undertone that it was all-important that General Taylor should be advised that the enemy were concentrating in overwhelming force in that quarter. "Get me in your stirrups Colonel, and I'll take it to him, or die," was the prompt reply. This was effected on the plea that he, the Colonel, would like for one of his men to tone down his charger. Dan, of course, was the man selected. As soon as he was in the saddle he began to make the noble animal restive by a sly application

Page 38

of the spur, and then suddenly driving them both in to the rowels, he rode through and over half a dozen mustangs and their riders, and, though a thousand "escopitas" were emptied at him, he and his horse escaped without a scratch. Waving his hat, he yelled back: "Adios, Ampudia; tell old Peg-Leg (Santa Anna) we'll give him hell." In briefest time possible the news was conveyed to "Old Zack." In recognition of the feat, Congress voted the hero six thousand dollars ($6,000) and two thousand (2,000) acres of land (if I am correct as to quantity), and Dan lived upon it like a fighting cock for three whole months, and a little later on died in the Charity Hospital, St. Louis, true to the last to man's noblest instincts and to all of his host of friends, except himself.

Captain Henrie, I say, used laughingly to remark that whilst the General's "dying speech was rendered in my best and most expressive Castilian," I took the liberty of adding on my own hook: "Captain, them's not my sentiments; I know you to be muy valiente." Dan further added that the effect produced by the "dying speech" was electric, and just the reverse of that anticipated. "Tell him," exclaimed the Mexican officer, "he is not mistaken. If General Santa Anna requires paid butchers, he will have to find a substitute for me. Mount, gentlemen, and let's push on."

Close shaving, that! Finally, the whole party were locked up in Perote's dungeon keep. Before they had well gotten their new quarters warm, objecting to the cold comfort they afforded, sixteen of the most resolute determined to vacate them and re-immigrate to Texas. To do this they had to cut through an eight-foot wall composed of a volcanic rock harder than granite, and with most crude and indifferent utensils to work with. It was a conception sufficient to have appalled even Baron Trenck, whom all the State prisons of Prussia could not restrain. It required weeks and months of unremitting work to do it, but finally it was done; and on the night

Page 39

of July 2, 1843, they crawled through the narrow aperture, which six months of starvation made easier for them, let themselves down by means of a small rope to the bottom of the moat, some twenty or thirty feet below, scaled the opposite side and a "chevaux de frise" beyond, and stood up free once more, but carrying their lives in hand. Here they separated, by preconcert, into parties of two; General Green and our old friend, Captain Dan Henrie, going together and striking out for Vera Cruz. Eight of them, after incalculable sufferings, hardships and hairbreadth escapes, including the two last named, got back to Texas. The other eight were recaptured.

All of the special details, incidents and anecdotes connected with these splendid achievements were graphically told by General Green in "The Texan Expedition Against Mier," an octavo volume of some five hundred pages, published by the Harpers in 1845, a work extensively sold, which many of your older readers will doubtless recall, now out of print.

Shortly after his arrival at home, he was returned to the Congress of Texas, where he was unremitting in his efforts to effect the release of his unfortunate comrades whom he left in Mexican dungeons. This was finally effected, some twelve months later on, after some of their original number had paid the extreme penalty that cowardly tyranny can extort from freedom's champions when the opportunity offers. This imperfect tribute to their valor and endurance is being penned on the forty-ninth Christmas anniversary of that wonderful fight.

During his legislative service he introduced the bill making the Rio Grande the boundary line between the two contending countries, which became a law, the "Neuces" being the extreme limit that Mexico would either directly or indirectly recognize. It was upon the basis of claim then set up that President Polk, after annexation, ordered troops under General Taylor to the mouth of the first-named river, which

Page 40

resulted in the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca and the war ensuing. That the acquisition of the vast and indispensable territory by the treaty of peace was worth hundreds of times more to the United States than the cost of the war amounted to, is now generally conceded.

On the eve of annexation he returned to the United States, and shortly after married the widow of John S. Ellery, of Boston, a lady of rare worth and manifold attractions.

Four years later (1849) we find him journeying alone through Mexico, from Vera Cruz to Acapulco, on his way to California, which was just then looming into consequence by reason of large gold discoveries. After working in the mines for a while, he was elected to the first Senate of that State and served out one term, being a prominent candidate for the United States Senate in the ensuing year.

While in that State he projected and laid out the towns of Oro and Vallejo, the last for a while the recognized capital, and both now places of considerable repute. During his citizenship in Texas he, in connection with Dr. Archer and the Whartons, had purchased and laid out Velasco at the mouth of the Brazos, now of recognized importance, owing to recent deepening of water on the bars.

During his sojourn in California he was made major-general of her militia and sent with an adequate force to suppress Indian disturbances in the interior, which was done. But a greater work was the defeat of what was known as the "Divorce Bill" in that first Legislature, which authorized absolute separation upon mutual request of man and wife. Unless mistaken, this infamous measure, making marriage a practical nullity, had passed the House and was about to be brought up in the Senate, with every indication of an almost unanimous vote, if taken on that day. At the time, there being few women in the State, the far-reaching and pernicious effects were not duly weighed and considered. Senators

Page 41

Green and McDougall (afterwards Governor and United States Senator) were amongst the very few in opposition to the measure; but they were earnest, and, after exhausting all the devices of parliamentary strategy possible, succeeded in postponing a vote, thereby defeating the measure.

During the same session he introduced and had passed a bill for the establishment of a State University, which has grown to be one of the most flourishing and best endowed schools on the continent. That world-renowned scholar, Professor Daniel C. Gilman, was called from its presidency to fill the same position in the Johns Hopkins University, which he has done in a way to elicit the admiration and astonishment of the scholastic world.

The reader will, I trust, pardon a personal reminiscence in this connection of the narrative. Shortly after Mr. Polk's inauguration as President, General Green returned to the United States, and taking me, then a small boy, with him, repaired to the Hermitage and passed the greater part of the day with his old and honored friend, ex-President Jackson. It was a visit ever to be remembered. Although but six short weeks intervened between that day and the one that saw him borne to the corner of his garden for interment, his old-time vigor of expression and enthusiasm seemed in nowise abated. The old hero had himself lifted out of bed, and whilst sitting upright in an easy chair, entered warmly into conversation with his visitor upon the current topics of the day, upon men and upon horses. Upon the question of Texan annexation he said: "Let me live to see it, and I can truly say 'Let Thy servant depart in peace.'" As we were leaving, he arose with an effort, and placing his hand upon my head gave me his blessing.

Some four and forty years thereafter, almost to the day antedating dissolution, it was my singular good fortune to have been present at the death-bed, as it were, of another

Page 42

patriot hero, sage, and statesman. Some six weeks before his death, and by his invitation, I passed three or four days with ex-President Davis in his quiet and lovely retreat of "Beauvoir." It was indeed a personal privilege to have seen and heard those two immortal men at the same stage of their sunset. In grand heroic qualities they were of kindred type, and cast in kindred mould. Self-reliant conviction, and devotion to conviction pedestaled on high principles, was the ruling trait of each. It was the ruling trait of Cæsar, and, in lesser degree, of Cromwell, of Frederic, and of Napoleon. Coupled with high genius, and the hero is the inevitable outcome.

In those two old men I see, and methinks posterity will see, the two most pronounced and Titanic figures of this country during the century. But a truce to digression, and return to our subject. That he was the friend of such, and of Calhoun and Albert Sidney Johnston, is a no mean letter of credit of itself.

During the pending annexation negotiations he was tendered by Mr. Polk's administration the post of confidential agent in that matter, but declined on the ground that he was then a citizen of the other contracting power. Later on, he was indirectly offered by President Pierce another important diplomatic appointment, but again requested that his name might not be sent to the Senate.

In his declining years he returned to his native county and

settled on a plantation on Shocco Creek, known as

"Esmeralda," and passed his remaining days in the cultivation of

corn and tobacco, old friendships and old-fashioned

hospitality. He had long foreseen and foretold as inevitable the

great political crisis which resulted in the clash of arms

between the sections in 1861. Whilst devoutly attached to "the

Union of the Constitution," nevertheless, when he saw the

trend of events and could deduce therefrom but the one

alternative of sectional domination or sectional assertion, he did

"ESMARALDA"

In Warren County, North Carolina, my residence until final removal hence to Tokay Vineyard,

Cumberland County, where I still reside.

Page 43

not hesitate which to espouse. In fact, he may be said to have been what few now are willing to confess themselves to have been - an "original secessionist," a secessionist per se. He reasoned that the solution of the dread question "by wager of battle" was unavoidable, and each recurring census told him that the longer it was deferred, the worse it would be for the assertive and weaker side. The unceasing regret of his latter days, and hastening cause of his death, was that when the mighty crisis came he was debarred by chronic disease (the gout) from taking part.

He died, as some have said, from a broken heart, sequent upon a succession of disasters in 1863, including Gettysburg, Vicksburg, Port Hudson, and operations incident to these last.

He died on the 12th of December, 1863, and was buried in his garden whilst the writer was a prisoner of war on Johnson's Island.

In manner he was suave, gentle and polite, although strangers might have thought him a little brusque. In form and feature, one of the finest specimens of physical manhood ever seen. Simple and straightforward in his bearing and intercourse with all, he loathed duplicity and hypocrisy in others. Especially did he hold in unutterable abhorrence vulgar upstart pretension and pretenders, whether of the purse-proud, official, or any other variety, mattered naught. Had he made accumulation and money-making the primary object of life, he had died wealthy, for few ever had such opportunities.

This poor notice of a pronounced and historic character and gallant gentleman cannot be more fittingly closed than by an excerpt from an address of a gifted young friend, Mr. Tasker Polk, of Warrenton, North Carolina:

"Among all her illustrious sons of the past, there is not one at the shrine of whose memory Warren County looks with greater love and reverence than at that of General Thomas J. Green. He was generous to a fault, noble and grand, fiery

Page 44

and impulsive; heard the Texan cry for freedom, left a home of luxury, sought the field where blood like water flowed, and unsheathed his sword in defense of a stranger land, nor sheathed it till that land was freed. The cry of the oppressed reached his ear, and was answered by his unselfish heart - that heart which gave the first beat of life 'neath Warren's sky.

"Bravely and gallantly he fought. His blood stained the plains and broad prairies of Texas, the cause for which he fought triumphed, the "Lone Star State" was saved from Mexican persecution, and his chivalric nature was satisfied. Years passed, but the memory of old Warren still remained fresh in his mind.

"He returned to spend the remainder of his illustrious life among his people, and many yet there are who remember with pleasure how 'Esmeralda's' door, whether touched by hand of rich or poor, ever swung on the hinges of hospitality."

Page 45

CHAPTER V.

To return from this digression. We reached Nashville two hours later, and, after a week's delay, continued on north by steamboat, stopping over in Louisville a few days. At that time and place was being held a religious council, conference, convocation, or whatever the appropriate designation may be, which was pregnant with most momentous consequences a little later on.

It was beyond my ken to grasp its import at the time. My father did, and remarked to me, when the decision was announced dividing the great Methodist Church into two bodies on sectional lines:

"That, my son, is the entering wedge which is destined to split this Union asunder and to deluge the country in blood. Yankee bigotry, impudence, and numerical count with each recurring census, have long held the hellish purpose in contemplation, and only bides the odds that cowardice demands to set about its execution. Whilst it will prove (whatever the issue) the greatest calamity that ever befell a free people, nevertheless, if they will have it, let it come, and the sooner for us the better, owing to the aforesaid census-taker of succeeding decades."

Was he a prophet?

The question at issue on that grave occasion, as it recurs after a lapse of intervening years, involved the right of a bishop of that persuasion holding slaves, whether hereditary bondsmen or otherwise. The verdict rendered on that occasion by that oracular body was reproof, reprimand, insult, not only to that high dignitary, but to every subordinate canonical who might aspire to that high pinnacle. Nay, more; the vile insult reached out by implication and included every member of the laity who was or might be possessor of

Page 46

a "chattel in black," either by ancestral devise or by purchase from New England "negro-traders," ab initio, or later on. Every other church, except two, I believe, soon followed the pernicious example set.

Thus, these in alliance with a cackling flock of fussy old maids, some in petticoats and some in breeches, with a lot of old Congressional emasculates thrown in for seasoning, was set a-boiling this hell broth of brotherly hate, which required sulphur and saltpetre, and most plethoric supplies of the combination, to tone it down. Moral: Let the church or churches attend to legitimate duties, and let extraneous ones severely alone; let the class of nondescript sex just named forswear political meetings as above their reach and comprehension; let them stay at home and rock the cradle, not of home-production contents, which nature, with wise forethought, has denied that unfortunate class, but let them borrow of their more fortunate neighbors. The advice is well meant, and if adopted will keep that whole tribe out of political pow-wows and caterwaulings, and check their insatiate and insane craving for notoriety. Let us give gratitude that our section is not favorable to such noxious, hermaphroditic, fungus growth.

In due time - that is, about four times what it now takes - the Federal Capital was reached. Barring the public buildings, which were even then creditable to a new country, despite later-on comparisons, when they stand, as to-day, the finest in the world, the city of Washington gave little promise of its subsequent marvellous development. Muddy and unpaved streets, dwellings and stores of common structure and two or three stories in height, vacant lots almost reaching out to the dignity of corn-fields, sloshy crossings between streets! A sluggish, murky creek ran, or rather crept, through the town, euphemistically or derisively called "The Tiber." Garbage heaps and cesspools there were on all hands. Such was a most uninviting village, as seen by me and the snob Dickens

Page 47

much about the same time. It was about midway between this day and the one on which President Washington and his French protege, L'Enfant, first began work on the metropolis that was to be, half a century intervening.

What a contrast between the straggling village and the city of to-day! What a contrast between then and now! Except in numbers, rivaling the proudest capitals in the world to-day in grandeur and magnificence, and suggesting those of ancient fame on the banks of the Tiber and Tigris. What it is destined to be at the middle of the dawning century baffles the imagination and "must give us pause." For the past last half its growth and artistic development have kept pace with the material progress of the country, which, until lately, was bounded by oceans on every cardinal side save one, until in an evil hour, lust for more land and imperial sway made oceans far too contracted for our boundary lines. The "mad sons" of Macedon and Corsica were actuated by the same boundless outreach of desire. May not republics profit by the outlined warnings of tyrants and would-be all-ruling and out-reaching despots, wearers of purple and crowns though they be? Our tribe are mighty good imitators on that line, as is now being developed.

It has been said that only three men in recorded history have essayed the task of building a big city by systematic plan and method, who succeeded in the undertaking. These, I believe, are Alexander, Constantine, and Peter of Russia, each of whom left a monument behind adding to the immortality of its builder, whose name it bore. Here stands catalogued a fourth! Each was built by the pride of men, by subsidies and largess out of the public coffers.

While I was in Washington I was introduced by my father to President Polk and most of his cabinet, as well as to numerous prominent gentlemen in both houses of Congress, amongst them being Hon. Robert J. Walker, Secretary of the Treasury,

Page 48

who, by common consent of most competent judges, is held to be the ablest financier who has ever held that high position. Ten years later he did me the honor to take me in his law office as junior associate with himself and Mr. Louis Janin in the capital city, having just been admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of the United States.

From Washington the journey was continued to Ridgeway, North Carolina, to make the acquaintance of my paternal grandmother, then eighty years of age. This venerable lady impressed one from the start as one born to command, and such was the reputation that tradition gave her, after raising a dozen full-grown boys and girls. Her right to command was recognized of all, and most of all by the old campaigner who had just returned after a ten-years runaway. I am persuaded that in the even tenor of her way she instilled a wholesome respect for petticoat government on all of her immediate offspring, omitting not a progenitor of the masculine gender, who enjoyed the singular felicity of being my grandfather. And yet she was a very little woman.

Here I remained for the next few months, studying Spanish under my father's old prison-mate, Captain Dan Henrie, and indulging my fondness for miscellaneous reading, besides getting acquainted with my paternal kindred, none of whom were previously known. As a rule, they turned out to be, like those on the maternal side of the house, a very creditable connection. Then returned to Washington and passed the winter at the old "United States Hotel," at the time one of the best caravansaries in the city, but in the march of subsequent progress now difficult to find. It stood on Pennsylvania avenue, near Four-and-a-half street.

During that time I had for room-mate one of the most remarkable men of his age, Dr. Branch T. Archer, to whom allusion has already been made. He was the admitted first instigator to revolt against Mexican tyranny in the newly

Page 49

fledged commonwealth (Texas), and that in a town garrisoned by a thousand Mexican soldiery. He had sent out circulars to every American settler, within a radius of thirty miles, to be on hand at appointed time with rifle and bowie knife. Some three or four dozen of the sturdy fellows were there to meet him. In burning words he told of the wrongs and outrages to which the young colony had been subjected by irresponsible satraps and their minions, and appealed to their Anglo-Saxon manhood to rise on the spot and put an end to the crying shame of white men longer submitting to the sway of mongrels and mulattoes.