Two Boys in the Civil War

and

After:

Electronic Edition

Houghton, W. R. (William Robert), 1842-1906

Houghton, M. B. (Mitchell Bennett), 1845?-

Funding from the Library of Congress/Ameritech National Digital

Library Competition

supported the electronic publication

of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Teresa Church

Images scanned by

Kathleen Feeney

Text encoded by

Kathleen Feeney and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1998

ca. 400K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1998.

Call number 973.78 H838t 1912 (Davis Library, UNC-CH)

Source Description:

Two Boys in the Civil War and After

W. R. Houghton

M. B. Houghton

Montgomery, AL

The Paragon Press

1912

The electronic edition

is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization database, Documenting the American South.

Any hyphens occurring in

line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the

preceding line.

All quotation marks and

ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left

quotation marks are encoded as "

and "

respectively.

All single right and left

quotation marks are encoded as '

and ' respectively.

Indentation in lines has

not been preserved.

Running titles have not

been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using

Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

- LC Subject Headings:

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives, Confederate.

- Confederate States of America. Army -- Military life.

- Houghton, M. B. (Mitchell Bennett), 1845?-

- Houghton, W. R. (William Robert), 1842-1906.

- Reconstruction (U.S. history, 1865-1877).

- Soldiers -- Alabama -- Biography.

- Soldiers -- Georgia -- Biography.

-

1998-03-02,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1998-02-20,

Kathleen Feeney

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1998-01-01,

Teresa Church

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

[Cover Image]

[Spine Image]

[Half-Title Page Image]

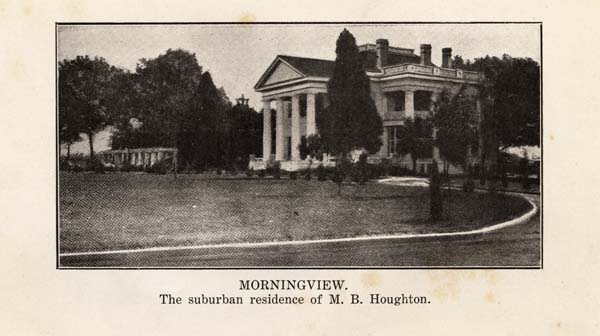

MORNINGVIEW.

The suburban residence of M. B. Houghton.

[Frontispiece Image]

[Title Page Image]

Two Boys in the Civil War

and After

W. R. HOUGHTON

M. B. HOUGHTON

Montgomery, Ala.:

THE PARAGON PRESS

1912

WE DEDICATE THIS LITTLE VOLUME

TO THE MEMORY

OF THE

CONFEDERATE DEAD

THOUSANDS OF WHOM SLEEP IN UNMARKED GRAVES

AND TO THOSE OF THEIR POSTERITY WHO ADMIRE

AND VENERATE IN THEIR FOREFATHERS,

HEROISM, COURAGE, BRAVERY, SACRIFICE, ENDURANCE,

LOYALTY.

Page 6

W. R. HOUGHTON.

Page 7

W. R. Houghton as a Confederate Soldier

and After

William Robert Houghton, whose thrilling and interesting

narrations of his service and sacrifices in

the Great Civil War of 1861 to 1865 are published

hereinafter, was an intense Confederate and believed

with all his ardent and enthusiastic nature in the

righteousness of the Southern cause. He was among

the last of the immortal thin gray line to yield up

his long cherished hopes of the final triumph of

Confederate arms on the fateful field of Appomatox.

Buoyant and bright of disposition, alert in mental and physical perception, brave and gallant in action, he was the ideal soldier with no selfish ambition for place and power, but was consumed with an earnest desire to achieve the independence of his native South.

To him duty was but a way station on the rugged highway of remorseless war, and he far transcended her demands in his enthusiasm to drive the Northern invaders from the soil of his beloved South.

It was such soldiers as William R. Houghton, and their name was legion in all the armies of the South, that caused our greatest general to modestly disclaim credit for so many splendid victories, but freely accorded them to the unrivaled valor and bravery of his men in the ranks.

An Athenian statesman is said to have boasted that there was not a citizen in his state who was not capable of conducting wisely and successfully the destinies of Greece, so, in the ranks of the Confederates

Page 8

there were many who would have led their comrades with equal or greater success. In more than one important engagement of the great Civil War, it has been freely conceded that the victory over the enemy was won by the gallantry and invincible bravery, of the Confederate privates in the face of incompetent and unwise leadership on the part of commanding officers.

The opening of the civil war found W. R. Houghton eighteen years of age, engaged in teaching school in a neighborhood of wealthy and aristocratic planters near Smiths' Station, Russell county, Alabama, about eight miles North of Columbus, Georgia. This neighborhood together with other contiguous parts of counties have subsequently been formed into the county of Lee. Columbus, Georgia, at that time was a prosperous and influential city and dominated the social and commercial interests of east Alabama. One of the crack military companies of the city was the Columbus Guards, in whose ranks were found the young men of the best talent and blood of this thriving town. It was an old organization with high standards, the pride of West Georgia and Eastern Alabama.

With this organization W. R. Houghton volunteered for one year and at the termination of this period for the war.

How well he acted his part is freely attested by the love and admiration of his surviving comrades and officers. The highest officers in command trusted him implicitly and allowed him to go voluntarily on many delicate and dangerous scouting expeditions into the lines of the enemy.

The narrative of his personal experiences and observations, penned by himself, will interest thousands

Page 9

yet unborn, who in reading the history of this Titanic struggle, wish to catch the view point of a private soldier of quick apprehension and remarkable memory.

At the close of the war he returned to the old neighborhood where he had formerly taught, almost a physical wreck. Penniless, and threadbare of clothing, he was taken in hand by his cousins, the Misses Whitten who were veritable angels of mercy and sympathy and who devotedly nursed him back to health and strength.

He again resumed his school under the changed conditions among his former patrons or such of them as had survived the struggle. He begun reading law during his school term and after its close he studied under his father at Newton, where he was admitted to the bar.

He located in Hayneville where he practiced many years and where he married Annie Streety only daughter of John P. Streety one of the large planters and merchants of that town. His wife died a few years after their marriage leaving one son, Harry S. Houghton who is also an attorney and resides at Morningview near Montgomery.

He removed to Birmingham in the year 1886 and practiced his profession in partnership with Col Collier, Colonel Tallifero, and Captain W. C. Ward with whom he was practicing at the time of his death.

He had among his clients some of the best and most prominent citizens of Lowndes, Montgomery, and Jefferson counties.

He was noted for his ability as a lawyer, his high sense of honor, sterling integrity and honesty, his

Page 10

unfailing affability, charity, patriotism and love of his fellow men.

What is somewhat rare in the legal profession, joined with fine legal ability, he possessed business acumen and had slowly accumulated a handsome competence.

His life was full of good deeds, kindliness and helpfulness but he asked for no inscription to be chiseled on his monument commemorating any of his virtues but requested this only

W. R. HOUGHTON

A CONFEDERATE SOLDIER

In Oakwood Cemetery in Montgomery, the Capital of the State he so fondly loved stands a lofty white marble shaft above his grave with the above simple but heroic inscription.

The following tribute to his memory is copied from an editorial in the Birmingham Age-Herald of July 31st, 1906, the morning after his death:

"Judge William R. Houghton died last night at the Hillman hospital as the result of a stroke of paralysis suffered last Tuesday morning. Since stricken he had been in a critical condition and there had been little hope of his recovery.

"On Tuesday Judge Houghton was paralyzed while walking on Eighteenth street and in a few hours lapsed into unconsciousness. He was conveyed to the hospital where he had received the best medical attention. He remained in a deep stupor most of the time with only occasional returns to consciousness. His vocal organs were affected by the stroke and he had never been able to speak a word, but by slight movements of the head he was able to

Page 11

indicate that he understood remarks addressed to him.

"Last evening about 6:30 o'clock there was a sinking spell and relatives were hurriedly summoned. The end came at 7:30 o'clock. At his bedside at the time were his son, Harry S. Houghton of Montgomery and the deceased's brother, M. B. Houghton. He leaves also a sister who resides in Austin, Tex.

"Judge Houghton's body will be carried to Montgomery this morning at 8:30 o'clock. The funeral will take place there this afternoon.

SKETCH OF HIS LIFE.

"William R. Houghton was born in Heard County, Georgia, on May 22, 1842. When he was but a small boy his family moved to Alabama and settled near Opelika, where he was reared and educated. At the beginning of the civil war he was teaching school near Mt. Zion, Ala., but at the first call for troops he enlisted in the Columbus, (Ga.) Guards. He served throughout the war and participated with marked gallantry in many important battles, being wounded several times. At the close of the war he took up the study of law and practiced at Rutledge and later at Hayneville.

Moving to Birmingham about fifteen years ago he formed a partnership with E. T. Talliferro, and later on practiced with W. A. Collier. In 1896 he became the partner of Capt. W. C. Ward in the law firm of Ward & Houghton and had been associated with him to the present time.

WAR ANNALS.

"Judge Houghton was deeply interested in literature

Page 12

and especially war annals. He made valuable contributions to Confederate history. His narrative papers on the great battles are regarded as having high historical value. The deceased was often urged to put these narratives into book form, and was engaged on this work when the end came.

"Devoted to the stirring memories of the sixties and ever bound to his old comrades of the war, Judge Houghton accepted the results of the surrender and lived and worked for the upbuilding of the south. Proverbially unassuming, the deceased was known far and wide for his bravery and his heroic spirit, and he was known, too, for his kindness of heart and his unostentatious deeds of charity. His death will be profoundly lamented in Alabama and to Camp Hardee, United Confederate Veterans, his passing away will come as a real grief."

[Illustration]

Page 13

WAR RECORD OF W. R. HOUGHTON WHILE SERVING IN CONFEDERATE STATES ARMY.

Name - W. R. Houghton.

Where born - Franklin, Heard County, Georgia.

Rank when entering service - Private.

Rank at close of service - Orderly Sergeant, detached as scout for General Longstreet.

Age at time of enlistment - 18 years.

Occupation at time of enlistment - School teacher.

Occupation after the war - Lawyer.

Condition of health - Never robust.

Residence at time of enlistment - Smith's Station, Ala.

Where mustered into service - Tybee Island.

How long - One year, afterward for the war.

Name of company - Columbus Guards, Co. G., Captains Roswell C. Ellis and Thomas Chaffin, Jr

Regiment served in - Second Georgia.

Brigade - Benning's, afterward Toombs'.

Division - Jones', afterwards Hood's.

Corps - Longstreet's.

Army - Northern Virginia.

How often on furlough - Twice for wounds, once for gallantry at Chickamauga and once on one day's leave.

In service how long - Three years, eleven months three weeks.

How many times wounded and where - Seven times, once at Malvern Hill, once at Second Manassas, other wounds slight, at Chickamauga, Petersburg and below Richmond.

How often a prisoner of war and where captured -

Page 14

In the evening of ninth of April, 1865, after General Lee had surrendered at Appomattox.

Discharged from service - April 12th, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Va., paroled as a prisoner of war.

Engaged in battles and skirmishes - Yorktown, Seven Pines, Malvern Hill, Second Manassas, Thoroughfare Gap, Fredericksburg, Suffolk, Gettysburg, Falling Waters, Maryland, Chickamauga, Wills' Valley, Knoxville, Fort Sanders, Spottsylvania, Cold Harbor, Trenches at Petersburg, one month, under incessant fire, North lames River, Fusell Mills, Fort Harrison, Darbytown Road (three separate engagements), Petersburg again April 1st, 1865, Farmville April 8th, 1865, Appomattox April 9th, 1865. Numerous skirmishes outside the lines.

WAR RECORD OF MITCHELL B. HOUGHTON

WHILE SERVING IN THE CONFEDERATE

STATES ARMY.

Name - M. B. Houghton.

Where born - Franklin, Heard County, Georgia.

Rank - Private.

Age at time of enlistment - 16 years.

Occupation at time of enlistment - Newspaper work.

Health - Fairly good.

Where mustered into service - Fort Mitchell Alabama.

For how long - One year, afterwards for the war.

Residence at time of enlistment - Newton, Alabama.

Page 15

Name of company - Glennville Guards, Company H.

Regiment served in - Fifteenth Alabama.

Brigade - Law's, afterwards Trimble's.

Division - Hood's.

Corps - Ewell's, afterwards Stonewall Jackson's.

Army - Northern Virginia.

Captain - William Richardson.

How often on furlough - None except when wounded.

In service how long - Three years, eight months.

How many times wounded and where - Twice, in head Second Manassas, in hand at Chickamauga. Latter light, former serious.

How often a prisoner of war and where captured - On foot hills of Lookout Mountain, in night attack a few days after the battle of Chickamauga. My Captain and thirteen others captured at same time.

Where confined and how long - Camp Morton, Indiana, 16 months.

Discharged from service, at Richmond, Paroled when liberated, and war practically over.

Battles engaed in - Siege of Suffolk, Second Manassas, Cedar Run, Port Republic, Gettysburg, Chickamauga, and in all the engagements of Stonewall Jackson's valley campaign wherein three separate forces of the enemy each equal in numbers to our own were defeated and vast wagon trains and stores captured.

Page 16

M. B. Houghton as a Confederate Soldier

in the Great Civil War and After

In the year 1861 I was living with my father at Newton, Dale County, Alabama, our family having moved in 1859 from Russell, now Lee County, a county formed subsequent to the war by partitioning parts of Russell and other contiguous counties. The family at that time consisted of my father, Colonel William H. Houghton, my mother, who was a daughter of Rev. Rev. Mitchell Bennett, two sisters, Julia and Beatrice, and myself. My only brother, W. R. Houghton, was teaching school in a neighborhood of wealthy river planters near Smith's Station in the then county of Russell. My oldest sister, Elizabeth Ann, had married Caleb R. Olive and they were living at Union Springs. Mr. Olive volunteered in the Fourth Alabama Regiment and was mortally wounded in the battle of Gettysburg, and we do not know the place of his burial.

My father was 53 years of age and was practicing law in Newton in partnership with J. R. Breare, an Englishman, and enjoyed a lucrative practice as things then went. My father was known as Colonel Houghton, having commanded a troop in 1837 or 1838, at Wetumpka, Alabama, where he and his brother, Col. R. B. Houghton, latterly of Florida, were then living. The object of the troop was to protect the town of Wetumpka and settlers in surrounding country from the depredations of Indians and desperados.

The town of Newton at outbreak of the war, was

Page 16a

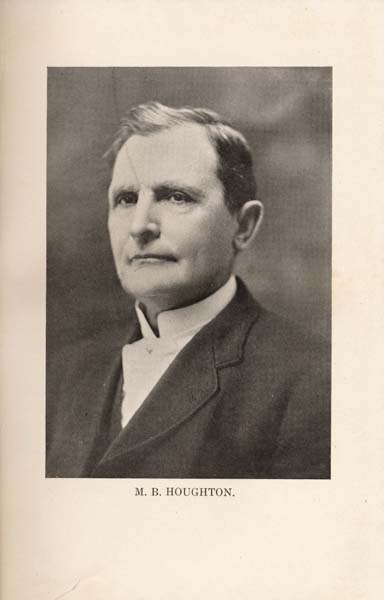

M. B. HOUGHTON.

Page 17

a flourishing village, the county site, with court house, churches, schools, some talented lawyers, physicians, and other citizens.

I was employed for some time in the office of clerk of the circuit court and afterward became a compositor, assistant pressman, assistant editor of the only newspaper published in the town, The Newton Standard. I have preserved two or three copies of the paper, one with an editorial written by my father, and one written of me by the owner, editor and manager, Mr. A. W. Weir, after I had volunteered to serve in the Confederate war.

The following is the editorial written of me by Mr. Weir:

(From the Newton Standard, July 5th, 1861.)

"Among the Dale volunteers that will start to Virginia today, may be found our worthy associate and warm friend, Mr. M. B. Houghton. We part with him with sincere and unfeigned regret. In all of our experience in the printing and publishing life we have never found a more efficient, industrious, steady and trustworthy operator, a truer friend and a more high minded, honorable gentleman; but we are consoled by one reflection that our loss will be our country's gain. No truer soldier, no more ardent patriot, no more worthier man can be found in the ranks of any army. The prayers and unceasing solicitude of his friends in Newton will accompany him wherever he goes, and if they avail he will distinguish himself and will return in due time to the embraces of his fond parents and the greetings of his numerous friends. His speech at the parting meeting last night was some evidence of his intrinsic worth and the faithful manner with which he will discharge his duties as a soldier."

Page 18

As the foregoing was said of me by another I am not open to the Biblical admonition, "Let not him that putteth on his armor boast as he that taketh it off."

I entered the Confederate Army as a private in a company recruited from Barbour, Henry, Dale and Russell Counties in Alabama.

John A. Truitlen of Glennville, Barbour County, came to Newton in July, 1861, and enrolled some sixteen volunteers, myself among the number. I was sixteen years old and fairly well developed for a boy of that age.

A meeting was called to assemble in the Court House, patriotic speeches were made, military ardor was intensified by the beating of drums and the shrill notes of the fife, while the women and girls sang patriotic songs amid shouts and waving of flags. A banquet was given at night and those of us who had enlisted felt that we were great heroes and were going forth to participate in a kind of holiday excursion, soon to return crowned with victorious laurels. The oratory of the occasion was very fervid and the people were wild with excitement. I had but a limited education and knew very little of the ways of the world, but felt my importance as a prospective soldier of the Confederacy.

There was a small but talented theatrical troupe playing in Newton, the two principal actors were Virginians about thirty years of age. They dissolved their company and enlisted with us. They were handsome, educated men and made faithful and brave soldiers. Their names were W. L. Wilson and Frank Boothby.

We went in wagons to Eufaula and thence to Glennville in Barbour County, where the company

Page 19

was recruited to its full strength of one hundred men and named the Glennville Guards. John R. Truitlen was elected Captain, who, on the formation of the Fifteenth Alabama Regiment at Fort Mitchell was appointed Lieutenant Colonel and William Richardson was elected in his place.

Our regimental formation was made at Fort Mitchell, a railroad and river station about nine miles below Columbus, Georgia, on the Alabama side. The regiment known as the Fifteenth Alabama, was made up here and James Cantey, who had seen service in the Mexican war, was appointed Colonel.

The Glennville Guards was numbered Company H. by which designation it was ever afterward called.

Col. Cantey made a rigid disciplinarian, so we thought, for the experience of military life was novel and somewhat humiliating. We were uniformed in Confederate gray, and had new tents and necessary equipments. The regiment was a fine looking and soldierly body of a thousand strong. It was numbered fifteen and was afterward celebrated as the glorious old 15th Alabama Regiment. Among the officers was Major Daniels of Barbour County, and Captain Vernoy, our commissary from Columbus, Georgia. We afterwards found that the commissary office was a very important one, and an energetic forager for his men, highly to be praised, although the soldiers mercilessly jibed and ridiculed him whenever the rations were short or not on time and he was seen to beat a hasty retreat to the rear when the enemy was encountered.

I do not remember any incidents of importance

Page 20

while we were at Fort Mitchell except several men were drowned in the river while bathing and the daily visits of the ladies to our camp and the constant drill and daily dress parade.

We were all anxious to get to the seat of war and were delighted when orders came to break camp and beard the cars for Virginia.

We bivouaced at Manassas, arriving just one month after the first great battle was fought. Obtaining permission the men would often explore the battlefield and eagerly seize any relics they could find, mostly for the purpose of sending back to relatives and friends.

We camped at Centerville six miles from Manassas about six months and it was the most trying period of the war. I say this because it was a period of enforced idleness with little to break the monotony of camp life but drills and parades. This was the time that the frying pan and the raw flour and fresh beef got in their deadly work. The men fresh from their homes with no experience in cooking did not know how to prepare the food furnished and the flap jack and half cooked roast produced dysentery and the men died by scores.

The first few months of our camp life in Virginia developed a hardihood and robustness in those who survived that stood them well in hand for the arduous marches, the great privations, the scanty rations and the threadbare clothing and equipment that resulted as the war progressed. Our camps were about thirty miles of Washington and our picket lines were often in sight of the dome of the great Capitol of what was once our country. It was strange, but we did not envy our Northern

Page 21

enemies their capital nor did we want to lay waste their land and country, but felt that we had divided our possessions, giving them their full share, and only desired to be let alone and left to make the best of our destiny.

There were almost daily rumors of the advance of the enemy and most of our forces being untried and raw we were kept in a high state of expectancy. We wanted to fight and wanted to do so right off, but the enemy would not gratify us, but patiently worked to perfect his plans, drill his troops and make a serious business of the war.

I have often done picket duty between Fairfax Court House and Washington, guarding some lonely trail in the blackness of night, feeling sure that I was the most important safeguard of the splendid army in my rear, as with strained eyes I peered into the woods and imagined every rustling leaf an enemy.

Our currency was good for a few months of our camp life and we could purchase fine Norfolk oysters at fifty cents a quart and the vegetables and fruits with which Virginia abounded, at reasonable prices. There were a great many hucksters and the soldiers were liberal customers. With the increase of Confederate money the peddlers and their wares gradually disappeared, but be it said of the noble men and women of Virginia, they never turned away a hungry Confederate soldier if, of their scanty store, they could supply his necessities.

We had fine beef in abundance when we first went in camp, but we did not know how to prepare it and were not accustomed to its constant use. Bacon would have suited us much better and if our authorities

Page 22

had found it out sooner many valuable lives would have been saved. We had to learn how to feed an army by degrees and the lesson was learned at a fearful cost of life. I have seen many excellent quarters of Virginia clover-fed beef lying in our camp on the snow, the men at liberty to help themselves, but untouched for the very sight got to be nauseating. The men divided into messes of three, four or even six taking turns at cooking, but the best cook usually had most of it to do, the others building fires, cutting wood or bringing water. I did not like large messes and never had more than three to divide duties with, and believe I got along better for it. We had skillets, a kind of oven with a handle and lid and would cut up our beef, put in the oven, fill with water, put coals of fire on top and bottom and let it stew all night, occasionally getting up to replenish the fire and water. This made an excellent and savory stew and was highly relished. We could do this very well while in regular camp, but afterward on forced marches we had no time or utensils, but used sticks or our ramrods to scorch the meat and baked our bread on the coals if we were so fortunate as to have anything to cook.

When McClellan moved the seat of war to the Peninsular and tried to capture Richmond from the East we marched to Ashland, and afterwards to Gordonsville so as to be in readiness to repel an attack from the North or East.

One night after Pope had succeeded McClellan as commander of the Federal forces, we were on a range of hills or bluffs on the South side of the Rappahannock river and the enemy occupied the

Page 23

opposite side. A furious cannonade was kept up even into the night, while we could only lay down and submit to the consequences. A large shell struck the earth about three feet below where four of us were reclining on the brow of a bluff and nearly covered us with dirt, but fortunately failed to explode. The air was full of whizzing balls and bursting shells, but the destruction of life in consequence was not very great.

Early in the night we started on a forced march up the river which we waded to the opposite side about midnight and with the Bull Run Mountains Between us and the enemy we pushed on toward Manassas Junction. Tired, wet, wornout, all night long we pressed forward, wading streams, climbing hills, across farms, through forests and along country roads until the morning found our army well on the way to the rear of the Federal army. We marched through a gap of the mountains and followed the railroad between Washington and Richmond. At Bristow Station the advance guard and cavalry had a fight with a force of the enemy and we came up in time to see the finish. While we were marching by the station a small detachment of Federal cavalry made a dash at our line. They were brave fellows, but we emptied every saddle before they could reach us with their sabres.

We pressed on to Manassas, where we found train loads of army supplies and sutler stores. The boys helped themselves and I got some coffee, canned fruit and other good things. We were in the rear of Pope's army and he was hastening to overwhelm us, consequently we had to burn and destroy what we so sadly needed. We marched about Centreville

Page 24

and Bull Run for two or three days, taking many positions and obscuring our movements in woods and behind elevations evidently with the object of deceiving the enemy as to our numbers for he was coming back at us to capture or destroy our force before help could arrive. One evening about dark, our lines and a brigade of the enemy came together and we had a hot fight. The firing of small arms was terrific and the fiery blaze from the thousands of guns made a fire works display that was worth seeing. We were engaged at very close quarters and the cry was raised "don't fire, you are killing our men." It seemed to have proceeded from both sides. Many ceased firing and both lines soon withdrew in the darkness and we never knew whether we were shooting at friends or enemies My part of the line was in the edge of a little thicket and from the sizzing balls and cut twigs it seemed that if I had held up an iron hat I could have caught it full of bullets in a short time

The hottest hand-to-hand fight I ever witnessed was the next day after the incident just related. It seemed General Jackson tried to avoid an engagement as long as possible in order to give time for Longstreet's Corps to come to our aid for Pope had turned his whole army, or it so seemed to us in the endeavor to crush our small force. The brigade to which I belonged was stationed behind an old railroad right of way and the road bed had been partly graded. The 15th Alabama had an embankment in front except on the extreme right where there was an open space of some fifty yards not filled in. To the right, still further, was a cut through a rise or hill about six to eight feet deep. Two lines of battle

Page 25

charged our front and a part forced through the opening, but we slayed nearly every man who got up to our line. They pushed our men back from the opening, but we on the left poured an enfilading fire into them that left few to tell the story. Three lines of battle, one after another in beautiful order with banners flying, hurled themselves against our men in the cut. The front line was nearly annihilated, but the second one came to the rescue and nearly met the same fate, but some of the men and the color bearers got to the edge of the cut and waved their flags over our men. We had mostly muzzle loading guns and there was no time to load. Then such a contest with rocks and butt ends of muskets I have never seen or read of before or since. It was in full view of all of our regiment next to our right, and we poured an enfilading fire which somewhat staggered the third line, but most of them got to the edge of the cut and were about to annihilate our men with overwhelming numbers, when with shouts and yells, our reinforcements came up and a volley or two put the enemy to flight. The maddened men, the flying stones, the clubbed muskets, the shouts, yells, smoke, dust, din, and rattle of that scene passes description. I caught a glimpse of the banners of Longstreet's men as they came rushing to our rescue some half mile distant and our men shouted in unison with them, inspiring us with a joy unspeakable and made every man redouble his efforts, if that were possible.

Our company fought behind the old dirt bank, as said before, and in front of us was a small woodland which gave the enemy a little advantage as to

Page 26

cover and they would fire at us whenever we showed ourselves on the bank. We had to walk up, take a little time to get an aim, which gave the enemy a fair shot and we lost a number of good and brave men in this way. William Baily, who lived near Newton, Alabama, and myself were firing alternately. I had gone up and fired and stepped back to load when Baily went up and was immediately shot through the lower part of the neck. He fell over me and I assisted him a little way to the rear. He afterwards died at home from the effects of this wound.

The Federals rapidly retreated after their bloody repulse and the arrival of reinforcements under Longstreet. Our regiment was moved to another part of the field in the direction of the retreating enemy, but I was ordered to remain at our last stand to succor the wounded and guard the regiment's baggage and some supplies. The field was literally strewn with the dead and wounded. It was a grewsome task, alone and in the moonshine, to guard this field of death and destruction. The piteous groans and wild despairing shrieks of the scores of helpless wounded would have appalled any but a hardened, half starved and wornout soldier. I rendered what aid I could to those around and made a fire upon which I broiled some bacon and boiled a large tin cup full of captured coffee. Near me were at least one hundred dead men and six within twenty feet of my camp fire. I took part in the battles of Gettysburg and Chickamauga two of the greatest and most sanguinary contests of the war, but I saw more dead and wounded on this field than in either of the two named. And the dead were

Page 27

principally the enemy for our loss was comparatively small, considering the sanguinary nature of the combat.

The enemy retreated towards the Potomac and the next day I joined the regiment in pursuit, although there were other troops in our front. While following the enemy two days after the battle the rear guard of the Federals planted some cannon on an eminence a mile or more in our front and shelled us with great vigor. One of the shells burst above our line which was in marching order and a fragment struck me on the side of the head above the right ear. A hole that you could put your thumb through was torn in my old tough wool hat and I was stunned and dazed. I felt the blood trickling down my face but was hardly conscious of my condition. I do not remember how I made my way but do remember stopping in an old house where there were many wounded being operated on by a surgeon. Some one felt of my head and told me I was badly hurt. Several pieces of the outer scull bone came out and I began to suffer great pain. The doctor's time was all taken up with cutting off broken legs and arms and would not look at others who had no shattered limbs. I do not know how I did it but I filled my canteen with water, punched a hole at the bottom and hung it up on a nail in the wall. I then laid down on the floor and let the water slowly drip on the wound. I kept this up all night and the next morning felt somewhat relieved but was in a semi-dazed condition. I did not get any medical attention and did not ask for any for I did not realize the necessity and the serious nature of my wound. Pieces of shattered bone continued

Page 28

to work out of the fracture at times for ten years after the war. For some time after the wound I have no recollection as to what happened to me, but remember to have been in a hospital and to have finally recovered sufficiently to rejoin the regiment. After some forty years I often feel some pain from this hurt and there is now a cut in the bone of my head about a quater of an inch deep and an inch long.

We were made a part of General Stonewall Jackson's celebrated foot cavalry and took part in his historic campaign in the Valley of Virginia, which I think in many respects, the most wonderful of the many great achievements of the war. The men were equal or superior to horses on the march, wading streams and rivers, climbing mountains and often engaged in skirmishes and brisk little fights with the enemy. We waded the Shenandoah river, the water coming up to our necks and quite cold but it did not strike us then as anything out of the ordinary. We crossed and recrossed the Blue Ridge Mountains at a great elevation and one night camped near the summit. As the regiments filed into their positions in the wooded coves the bands played "The Girl I Left Behind Me," and other familiar airs which resounded among the mountain heights and greatly delighted the weary soldiers. I thought I had never heard anything so beautiful and inspiring and in fact I have not since.

We captured an immense wagon train with supplies and were retreating up the Valley towards Staunton on the west side of the Shenandoah river pursued by Fremont and an army equal to our own in numbers. On the opposite side an equal force under

Page 29

Shields was trying to head us off. At Port Republic was a bridge, our only means of crossing an unfordable river. As we came up on the hills in view of the bridge and the valley beyond the enemy was in sight on the other side. Fremont also attacked our rear, and our regiment with others had to right about and fight his forces. We made short work of it charging right up to their batteries, not giving them time to work them effectively. While crossing a rail fence I saw a Yankee take a deliberate aim at me as I straddled the top rail. The bullet buried itself in the rail but did me no harm.

After forcing back Fremont's forces we hurried toward the bridge arriving in time to witness a brisk fight going on across the river. The position we occupied was much higher and we had a fine view of the contest which was raging in the valley beyond. We saw one line of our men charge the enemy but were received with such a galling fire they faltered and lay down on the grass. Another brigade double quicked up and with the "Rebel" yell rushed over them and put the enemy to flight. Our Calvary pursued them with relentless vigor and they returned no more to trouble us.

We had defeated two armies equal to our own in numbers, saved an immense wagon train and leisurely marched toward Richmond. Some time afterward the enemy rallied their forces and resolved to try us once more. They attacked us while we held a position on the base of a huge hill we called Cedar Mountain. They gave us a hard fight which was highly scenic and picturesque as we were far above the plains below and both sides occupied at times commanding positions in full view of each other

Page 30

The charges and counter charges, the play of many batteries of artillery, and the incessant rattle of musketry away up on these eminences made a picture of real war that we could see and realize. We finally repulsed them with heavy loss but it was not a rout for they greatly outnumbered us.

I have seen some daringly foolhardy deeds but where so many unflinchingly acted heroic parts it is hard to discriminate. We often thought if the enemy would only fight us two to one or double our number we would ask no easier job than to whip them, but we hardly ever had less than twice our force to contend with and often three times our number. There was no disputing the fact that our men were the best fighters for we had our hearts in the work and our homes at stake, while the enemy fought more like machines and their souls were not in it.

It was at the siege of Suffolk I witnessed a foolish act of bravery on the part of an aid, a Lieutenant Cousins from Mobile. We had earthworks about five feet high and the enemy's sharpshooters were in a bushy swamp in our front. This Lieutenant would get on top of the fort, take out his glasses and peer at the enemy's position and to show his contempt for their markmanship he would occasionally stoop down and with his pocket knife dig in the dirt for the balls. He had long curly hair and was over six feet tall, his appearance altogether impressing us that he led a charmed life. He was not hurt at this time nor afterwards that I ever heard of.

When our forces were near Orange Court House, I was detailed to guard a private house some two miles from camp. I do not know the reason a guard

Page 31

was necessary unless it was to keep away foragers as we called the men who were constantly seeking from the hospitable Virginia people something better to eat than our army rations. M. M. Pannell was the name of the man whose house I protected and I shall never forget the kindness of the lady of the house. She was a true Virginia gentle woman, full of grace and sweetness and made me feel more like an honored guest than a soldier under orders. I had the satisfaction of halting many intruders but I can testify to the credit of the Confederate soldiers in our army not one of whom persisted in trying to enter contrary to my warnings. I remained on guard about the premises for more than a week and then our command was ordered to another part of Virginia. It was stange but months after I had guarded this home, and after the campaign in Pennsylvania and the battle of Gettysburg, while we were leisurely retreating toward Richmond I was detailed to guard the same premises, where I again remained several days. One thing impressed me less at the time than afterwards, was a remark of Mr. Pannell that our cause was lost after the battle of Gettysburg, but I was young and enthusiastic and refused to believe it. Mrs. Pannell gave me a red Morocco bound little New Testament which I carried in my side pocket during the remainder of the war including the great battles of Gettysburg and Chickamauga and fourteen months in Camp Morton prison. I lost this highly prized relic forty years after the war in a fire on Court Street in Montgomery.

The grandest military display I ever witnessed was on the banks of the Potomac river when General

Page 32

Lee's army crossed over for the invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania. I was one of the Provost guard whose duties were sometimes in the front and at others in the rear or on the flank, but why we were on this particular occasion in the front I do not know.

We were stationed near the river bank on a beautiful bright morning when the Calvary in columns of fours marched by. The horses were in good trim and the men in high spirits. The procession seemed endless. Then came Battery after battery of artillery and the gray hosts of infantry. These men were all tried veterans inspired with a spirit of invincible determination and had the bearing of heroes.

The change of tactics or plans from the defensive to the aggressive made a wonderful change in the bearing and spirit of our men. They marched in close order with a steadiness and vigor and an air of conscious power and superiority that was majestic. The men appeared to be over the average in size and weight, fairly well equipped and uniformed and had unbounded confidence in their great Commander.

I had seen many bodies of fine soldiers but this army of invasion impressed me at the time as being the most superb fighting machine the world ever saw. After many years I have no reason to change the opinion then formed. With proper leadership they would have routed the federal forces at Gettysburg but it was impossible to scale rocky heights and dislodge a foe superior in numbers at the same time. It was a fatal mistake to join battle with the enemy in his chosen position where the natural obstacles were almost insurmountable.

Page 33

Our brigade appeared to occupy the extreme right at the battle of Gettysburg. At one time the enemy occupied a hill in our front that was very steep and rocky. We were on a hill also, within rifle range but between us was a deep ravine. We could see they were in some confusion and their teams and army wagons ready for flight. The men in ranks spoke of such a favorable opportunity to flank them on the left as that part seemed wholly unprotected. It seemed to us that a brigade or even a regiment could have turned their left and started a panic that might have caused a different result to have happened. Some of the officers afterward believed it could have been done but no one in authority saw it at the time.

GETTYSBURG.

One of the saddest sights I ever witnessed was

on the field of Gettysburg. We had captured some

fifteen hundred prisoners and I was one of the guard

marching them to the rear. Passing along where

there were hundreds dead, wounded and mutilated

I saw a soldier with a North Carolina regiment mark

in his cap leaning against a fly tent. A fragment of

a shell had struck him above the breast bone and

tore the whole stomach lining away leaving exposed

his heart and other organs which were in motion

and he seemed alive and conscious. I lingered a

moment for I had never seen any thing so shocking

before nor have I seen the countenance of a dying

man so peculiar and unearthly. The artillery fire

at the battle of Gettysburg was something terrific.

The battle field abounded in mounds and hills which

Page 34

were advantageous for planting and operating the cannon and the batteries on both sides were the pride of either army. I do not know the number operated at the same time but it was said to be five hundred; but I do know the roar was awful and the heavens surcharged with hissing, roaring balls screeching, screaming, bursting shells enveloped in sulphorous smoke that clouded the July sun. When the heavens are rolled together as a scroll in the last days I doubt whether it will present a more awe-inspiring spectacle than that historic field presented on that fatal day.

EXCITING ADVENTURE. A few days before the battle of Gettysburg while we were encamped near the base of the South Mountains in Pennsylvania, three of us obtained permission to go out foraging or in other words to buy something better to eat than our army rations and incidentally to have an adventure of some kind.

We saw a farm house dimly in the distance and bore down on it fully expecting to share some frugal Dutchman's ample supply of good things but on a near approach the sight of a half dozen birds of the same feather as ourselves blighted our hopes, but did not dismay us. We saw a clearing on the foothills of the mountain far in the distance and rapidly made our way toward it. We found an uncultivated field and an abondoned house, but beyond a trail or path that had been recently traveled. Following the trail we came into a thicket so dense and dark that one of my companions proposed that we go back as we might get into trouble, but we overruled him and

Page 35

pressed on. Suddenly the front man came to a halt, brought his gun to a ready and we followed his example very quickly. He had discovered a horse fastened by a line to a sapling about fifty yards ahead, but on investigation could find no claimant. I had separated from my companions a few paces when I discovered an entrance to a cave and called to them to examine it. Below was an immense ledge of rock and an opening in which some dirt had collected and I saw human tracks. We called to the supposed inmates to come out that we would not harm them, but could get no response. Finally against the protest of my companions I entered, and advanced slowly following the dim passage. I had gone some distance, when a short turn revealed a sight that made my hair stand on end. Reclining on a rock was apparently a pretty girl and near by was a man with a gun in his hand. Their den was dimly lighted through crevices in the top in which were fallen trees and limbs resting on the ledges of rock.

As I was in a position where I could not be seen, I watched carefully for other occupants until I was convinced they were alone. They commenced a conversation in a low tone and slipping into a crevice of the rock I determined to test their nerve. "Hello' there," I called? and the effect was magical. He bounded up striking his head against the logs and she screamed a succession of very healthy and voluminous screams. Her companion cried "mine Got! we be kilt already, mine Got!" and kept time with her for several minutes. Finally, during a lull I called to him to stuff his hat in his mouth and stop that noise, for I would not hurt him and if they continued they would scare all the wolves and bears off the

Page 36

mountain and run the rebels back over the Potomac. My jocular tone somewhat assured them but they trembled perceptibly, visible even in a dim light.

I ordered the man to put his gun aside, which he did, and I advanced into their chamber. My captives I found to be a fair Dutch girl and her companion her brother, an overgrown boy. They had been over the mountain on a visit when our cacalry cut them off from home and their minds were so filled with fear of the horrid rebels they had sought this retreat the whereabouts they had learned in hunting. We led them to their horse and down the mountain to the place where they had left their jersey wagon, hitched it up and sent them on their way rejoicing and heaping blessings on the heads of "repols" generally.

During the campaign in the Valley of Virginia while we were on the march, General Stonewall Jackson, our commander, several times rode to the front from the rear of his army. At such times we knew he was coming by the shouts of the men behind who quickly opened rank two and two on either side of the roadway. He came in a gallop on his chestnut brown horse, sitting not gracefully but easily, with the visor of his cap well down over his brow and a pleased expression on his countenance. While not an imposing military figure he appeared soldierly and striking. The men were wild with enthusiasm whenever he appeared, giving vent to their admiration by continual shouts and waving of hats We had unbounded confidence in his leadership and would have rushed into the jaws of death had he so ordered. It is said that he rode down near the bridge over the Shenandoah river, when pressed in

Page 37

the rear by Fremont and saw that Shield's forces had planted a battery on the other side commanding the bridge, our only means of crossing over. He shouted to the enemy to move that battery lower down, that the rebels were crossing below, which order they quickly obeyed. He then rushed a brigade across and met the Federals before they found out that they had been duped. The truth was that some of our cavalry did cross the river, but far below the bridge we so badly wanted at the time.

We were all proud of our connection with Jackson's army and whenever asked to what command we belonged we replied "to Jackson's Foot Cavalry."

Jackson was merciless in marching his men, preferring to strike terror to the foe by a surprise and flank or rear attack and at an unexpected time rather than have his men meet superior forces on their chosen battle ground.

One of the bravest men I ever saw in battle, and I have seen many brave ones, was John G. Archibald from west Alabama, I believe from Greensboro. He was not spectacular in his ways, making himself a target without reason, but always exchanged places, if in the rear rank, with the front man when a fight was imminent giving as his reason that he did not want to be shot with a dirty ball. He was never seen to show a tremor under the most galling fire nor to dodge a hissing shell, but always stood squarely to the front, cool and determined. He was about 45 years of age, rather under medium size, jocular and good humored. I saw him shot through the face the ball entering just below the left cheek bone and coming out on the right of his neck, making a horrible wound. We all thought he was mortally

Page 38

hurt but such was his vitality, he returned to ranks within six weeks, as valiant and true as ever.

The rations given us were often insufficient to appease hunger, and consequently there was more or less foraging to supplement the deficiency. One evening two of our men went to a farmer's house but found nothing they wanted but some stands of bees. Waiting until dark a little distance off they returned but found the place guarded by a fierce dog. By some means they made friends of him and soon made way with two stands fairly well filled with honey. Next day the farmer complained to the commanding officer of the theft, and stated that he had left his dog to guard the premises. The officer inquired why the dog had not done his duty, "The scoundrels stole the dog too" said the farmer at which we all laughed him into a good humor.

Longstreet's corps was transferred to Georgia to aid General Bragg and in a short time after we plunged into the battle of Chicamauga one of the great battles of the war, and one among a number of the most destructive recorded in history.

Our regiment, the 15th Alabama did not get into the hottest part of the great fight, but we lost many men. We were engaged mostly in the woods and with a retreating foe. We mixed up with the Federals several times and shot at each other at close range. I was slightly wounded by a minnie ball cutting open the top of my left fore finger but otherwise escaped unhurt. After the battle, while on picket duty near Chattanooga, I often exchanged newspapers and tobacco with the Yankee pickets. The Western men we found braver and more stubborn than those of the Army of the Potomac.

Page 39

Our rations about this time, were irregular and very poor. Our bread was made from corn and pea meal mixed and unsifted, with a very small piece of rusty bacon. The constant downpour of rain made the bread an unsavory mush. It was not strengthening and the men became greatly weakened.

About two weeks after the battle of Chickamauga we were ordered upon Lookout Mountain. It was a night march and altogether through woods and undergrowth. We halted several times, formed line of battle and threw up breatworks of logs and rocks only to leave them and go forward. Finally we reached the crest of a range west of Lookout. We halted, formed line of battle and made slight breastworks as before. We could hear the rumbling of the wagons and the sound of horses' feet far below in the valley. We constantly expected the enemy to attack us in front but we could not see, for the woods were dense and the hills steep, somewhat precipitous. It was an ominous hour for the thin gray line, away up on the mountain top in the midst of the scraggy woods. We could hear the roar of the moving hosts of the enemy with fresh re-enforcements prepared to cut off our retreat and strike us in the rear. About 12 o'clock at night we heard volley after volley of musketry far to our left, but the firing was intermittent and followed by ominous silence. The enemy's pickets were in front of us and we fired several volleys into the dark woods whenever we heard the rustling of leaves and bushes, but they did not answer. No doubt it was a mistake to have fired when we did as it only served to reveal our position. Suddenly one of the enemy's

Page 40

pickets came blustering up to our line immediately in front of my position, beseeching us not to shoot, that they were friends, and talking like a crazy man. Five or six muskets were pointed at his breast, but no one fired. Without faltering, he came right into our line but did not hold his gun at ready, talking and gesticulating like an actor. One of our men took his gun and gathering him by the collar made him lay down, threatening to use the butt of his gun on his head if he did not keep quiet. The tension of expectancy was now intense and I was so occupied with the front that I do not know what became of him.

A few minutes after two companies of our regiment on the extreme left broke and fell back, nearly doubling on us. The officers finally succeeded in rallying most of them and they returned to their positions. It was but a very short time after this that all of the left of the regiment fell back in confusion and stampeded to the rear. Not a shot had been fired and we could see no enemy. Most of us got up and followed but more leisurely. With several others I made an effort to rally the men. I remember one fellow ran by me so excitedly that he struck a large size sapling, straddling it and going over the top down the hillside. I called to my companions "Let's go back, I do not see anything to run from." Twelve or fifteen of us did return to our former places and in the confusion, being at night and in the woods, we thought the regiment was reforming. It never occurred to me that the enemy had flanked us, and we kept a sharp watch out front.

A short time after we had resumed our positions

Page 41

the rustling of leaves and tramp of men in my rear attracted my attention and I turned to see what it was. In the dim moonshine I saw a line of men that appeared better uniformed than our men and seemed larger, and had brighter guns. Still I would not believe that our men had all gone and decided they were re-enforcements. The line advanced within fifteen or twenty steps and I raised up and asked what regiment that was. The answer came "the 74th Ohio," and I knew I was in a bad fix, for I heard another officer command to shoot the first man who showed himself in front. When the line was nearly on me I gave up, and I found later they had my Captain Richardson and fifteen other men.

PRISON EXPERIENCE It was a novel experience to find one's self a boy prisoner in the hands of an enemy we did not highly respect. The blue coats were every where; there seemed to be myriads of them and they seemed to be handsomely uniformed, well fed and thoroughly equipped with superior guns, accoutrements, wagons and tents, presenting a striking contrast to my brave Confederate countrymen whose manly hearts were beating true under tattered and time-worn gray remnants of former uniforms. We were sent up in a boat to Chattanooga and guarded two days and then forwarded in freight cars to Nashville. At the latter place we were confined in the capitol and the yards surrounding it. Here we were drawn up in line and reviewed by Andrew Johnson, the military governor, and afterwards president of the United States.

Page 42

Those who consented to take the oath of allegiance to the North were released but few did so, and then Gov. Johnson appeared disappointed and mad at what he considered the stubbornness of the helpless prisoners. As fast as transportation could be provided we were forwarded via Louisville to Camp Morton prison, near Indianapolis, Indiana. On the way from Chattanooga to Nashville I believe some of us could have escaped, as the cars were loosely guarded, but most of us after the trying experiences of the Chickamauga battle, the heavy rains and poor rations, were nearly prostrated. After the excitement of battle and subsequent capture we had physically collapsed and did not possess vitality enough for a desperate undertaking.

It was in the latter part of September 1863, we arrived at Camp Morton named for Governor Morton of Indiana. The Prison had been the State fair grounds enclosed with a stockade about twelve feet high, made of one by twelve inch plank nailed upright on the outside of which was a sentry walk or platform about three feet from the top. About eight or ten acres were enclosed, and the old cattle and animal sheds were our barracks. These houses were made of plank placed up and down with the cracks or joints not broken or stripped and had dirt floors. The barracks had three rows of board bunks on each side of an eight foot passage way. Three men were assigned each bunk and no bedding furnished. Three to four thousand men were confined in this Camp under very strict surveillance. It was a motley crowd, dressed or partly dressed in all kinds of clothes except good and clean ones. Most of the men when captured, were worn out and famished and their faces had a haggard and weary appearance.

Page 43

Our bread was cooked in a bakery out side the walls and was good and wholesome but only a half pound loaf was allowed daily. The daily allowance was devoured in a few minutes. Our meats were cooked in big cauldrons inside the camp and was usually beef. No coffee or tea was given us but we had some beans and soup occasionally. The general ration was cut down to less than half the army allowance and many men slowly starved to death.

Some of the officers commanding were cruel and tyrannical and inflicted all sorts of punishment on many of the men who committed thoughtless acts or were in any way refractory. Often men were reported by spies and traitors among us to the commander for the expression of any sentiment of hope for victory for our side or criticism of the Federal conduct of the war or the management of the prison. Tieing up by the hands, bucking and gagging were common. Whenever a prisoner escaped they seemed to take revenge on many of the men by more than usual severity of treatment. It was not uncommon for a guard to shoot a prisoner for very slight infraction of the rules, and one little officer said to have been from Missouri delighted to show his authority by abusing the men in every conceivable manner.

The mortality among the prisoners was frightful. Insufficient food, and clothing, no bedding, little medical attention and the dull hopeless existence of prison life in a severe climate sapped the remaining vitality of the men and they died by the score.

Slow starvation among a lot of idle men gradually robs them of every noble instinct and transforms them into weak but ravenous beasts. It was curious

Page 44

but tragic to hear the prisoners recount the story daily and hourly of former feasts and revive the memory of every ample dinner they had enjoyed in the past. With glowing eyes and animated faces they delighted to tell of the good things provided by their wives and mothers in the halcyon days in Dixie. The subject became a passion - a frenzy, and men only existed to remember what had been.

I remember the case of a once handsome man who after the war achieved prominence at the bar in Georgia. He talked bread, bread, bread all kinds of bread, and what a great lover of bread he was until we thought he had gone daft. The boys nicknamed him "Bread."

There was a large ditch or canal across the grounds through which flowed a small sluggish stream that was always more or less filthy. Thousands of cray fish or craw fish as we wont to call them bred in this stream and the men would gather them for the purpose of making soup. Every dog, cat and rat also had to run for his life for the hungry men were omnivorous.

With two other men I had the top bunk at the North end on the East side of one of the barracks. The passage way between the two houses was covered but had a ground floor. The gabled end was not entirely closed up and the cold northwest wind was very severe. We had an old rubber blanket to spread on our rough plank bed and two other thin hair blankets for cover. We took turns as to sleeping in the middle for that was the warmest position. The winter was a very cold one, snow covering the ground more than forty days in succession, with two or more blizzards intervening. On one of these

Page 45

cold nights we laid down to try to sleep. One of my companions named Searcy, from Eufaula, Alabama, occupied the middle while I was on the outside most exposed. Searcy was over medium sized, well proportioned and seemed strong and vigorous. During the latter part of the night he talked of his adventures in battle, describing how he had shot three men in a certain fight, declaring that he knew he had killed them, and detailing all the circumstances. He expressed regret that he had not slain more, and bitterly upbraided the enemy for the treatment he was receiving, denouncing them in the strongest and most vigorous terms of which he was capable. He talked on while we his two bedfellows, were partially benumbed with cold and semi-conscious from drowsiness. He finally became quiet and when the morning came we found him dead.

It was astonishing to see the ingenuity the men developed. With their pocket knives they carved all sorts of trinkets, cups, plates and puzzles out of wood and other material. Time was no object and with infinite patience they wrought many artistic articles that they never could or would duplicate outside of a prison.

The guards and inspectors and such visitors as were allowed to see us rebels would buy many of these articles, paying a mere pittance for them, and many were taken by hook or crook and never paid for. By reason of this traffic more or less currency of the "shinplaster" kind was in circulation, besides some of the prisoners had money concealed on their persons when captured or had friends on the outside who managed to give them some.

As in life in the outside world among these to three

Page 46

to four thousand men many were thrifty, many barely held their own, and others exhibited the extremes of want and despair. By their skill, energy and tact a considerable number managed to live fairly well and made a little money.

A sutler store was one of the institutions of the camp and we could spend our little change for tobacco, cakes, bread, can goods and other goods not contrabrand. If the commander found that the men were buying too much for their comfort he forbade the sale for a while, but the love of gain would prevail and the sutler would slyly lay in stock some more of the forbidden goods. The commandant of the prison wanted the men deprived of everything that would mitigate their misery. The finger ring industry was the most important in the prison. Along with this trade was the making of watch charms, bracelets, breastpins and other jewelry

The sutler was allowed to sell us large guttapercha coat buttons at five cents each. These we would boil in tin cups until they resumed their original shape. With great patience the worker would cut the centre out and fashion it into a ring. Old gold pens, pieces of silver, brass buttons, and any other bright metal was used in making sets representing clasped hands, hearts and shields and other designs which were nicely engraved and highly polished The sets were riveted in with pins or strips of metal so perfectly that the fastenings could not be dectected. We used sand paper and a greasy cloth to polish. With my two bunk companions for partners I started a ring factory. These men were Johnathan Smith, farmer and blacksmith and R. M. Espy a farmer, both from Henry county, Alabama. Smith

Page 47

was somewhat of a genius at tinkering, Espy had no skill in any particular line and I was an untrained boy with a bent toward barter and some tact as a salesman.

Our first investment was for two rubber buttons costing ten cents which amount we raised by selling a part of our rations which we sorely needed. I cut a brass button from my old coat which we hammered out on an old piece of iron. By some means we bought or borrowed a ten cent file. Smith made two rings, Espy and I assisting in cutting and polishing. The sets were clasped hands with hearts on either side. The rings were well shaped and the metal shone like polished gold. I willingly acted as salesman and found a purchaser in the sergeant of the guard at ten cents each. With the money we purchased more buttons and made more rings.

Smith constructed a little machine that cut a small ring out of the centre of the button thus giving us two to the button. The small ones were suitable for children and were made as carefully as the larger ones. Double rings for men were made by riveting two buttons together so deftly that the joint could not be readily detected. All of the metal was nicely engraved, highly polished and were artistic and beautiful.

Smith invented boring and riveting machines and we gradually acquired the facilities for doing the work with more ease. Now and then a particularly mean official would come along and destroy all the little helps that a factory contained. He would delight in smashing everything in sight and we learned to conceal and scatter our treasures when one came in sight.

Page 48

There were so many rings and trinkets made and so few buyers that I had to seek a market. The prison authorities ran wood wagons to haul our fuel and would detail men to go outside of the camp to load the wagons and unload on return. I have often volunteered to work all day lifting very heavy sticks of green beach wood for the chance to sell my stock to the guards. The trip was about a mile and the grounds was covered with snow and my clothes were very thin but I braved it all and some days was not rewarded with a sale, but usually sold two or three.

Our trade in rings graudally increased and a short time, before we were released, and in one day I disposed of twenty dollars worth, but it was the banner sale of the season and a riddance of accumulated stock.

Sometime the sergeant of the guard would ask me to allow him to carry the rings outside to show to his friends or to the people of the city. No doubt they were in demand as curiosities or relics or were purchased by kind hearted civilians who did not object to aiding in this way the suffering prisoners. He did not always account for all put in his possession and at times paid over ridiculously low prices for those he said he had sold. With the money or shinplasters obtained by our handicraft we bought some extra rations and some few articles for our comfort.

I concealed on my person a dozen or more choice rings when we were released and brought them safely to Alabama. They were objects of curiosity and interest to my friends and relatives and were highly prized. Unfortunately, a few years after nearly

Page 49

all of them were stolen, presumably by a servant. A small one is yet in my possession. I also carved a wooden mug with a relief scroll bearing the inscription "Camp Morton Prison 1864," which I left with relatives in Lee county Alabama. It was much admired and was really a pretty keepsake but unfortunately was destroyed when their house was burned soon after the close of the war. I also brought home a large tin cup, more than a quart size that I had used during my campaign experiences as a general utility cooking vessel. As occasion demanded it was a soup pot, coffee pot, meat pot or for any purpose almost that a small cook stove could supply. The coffee was of burned bread crusts, parched corn or wheat, bran or swept potatoes. This highly prized old friend was also destroyed in a fire more than thirty years after the war had closed.

Tunneling was a favorite method of attempting to escape from the prison. The black soil of the prison enclosure was about three feet deep and underneath was a thick stratum of white sand. The men would commence under their bunks and dig with knives, sticks or any tool they could improvise down to the sand and then scrape out a tunnel toward the guard wall. The dirt was carried away in their pockets or they would tie a string around the bottom of the legs of their pants and partially fill the space around their limbs with the sand, then walk out and slowly scatter it about on the grounds so as not to attract attention. They often patiently worked for weeks until they estimated they had run their shaft outside the guard wall, usually about fifty yards, and await a dark night to open out on the outside. A number of men escaped in this way

Page 50

but spies and traitors made it dangerous and nearly every effort made during the last six months of our confinement was defeated by some scoundrel who would betray the workers.

In one or more instances the guards would allow the prisoner to open the outside end of the tunnel and shoot him down as he emerged. A preconcerted movement was projected for a general escape. It was one of those unaccountable uprisings that take possession of men without a head or immediate cause. No one appeared to direct but it was whispered from man to man and caused great suppressed excitement. For some reason it was reported that most of the guard for the prison had been withdrawn leaving barely sufficient men to mount the guard on the walls. It was believed that the Confederates were threatening some nearby point and all their men were needed to repel them. On a certain night armed with rocks and sticks, we were, about eight o'clock to scale the east wall, rush the guard and escape to the country. Hundreds of us drifted in the direction indicated. We were desperate and did not take into count the risk. I had several stones of convenient size to knock a guard down if he offered resistance. The few sentinels could not kill all of the mob and we could get over before others could come to the rescue. Then the sentinels on the walk high up on the walls would not be able to shoot often or accurately with hundreds of stones being hurled at them. We were in striking distance when we heard the bugle calls on the outside, the double quick of infantry, the unlimbering of artillery and the tramp of cavalry. We had been betrayed and sullenly returned to our quarters.

Page 51

Thirteen of our men escaped one day, but a few of them were afterwards retaken. A detail was sent out with some wagons for wood about two miles from camp. This detail of thirteen was guarded by six men. By some means a signal was agreed on and at a favorable opportunity they seized the guard, took their arms and made off. Afterwards the guard was doubled and no more escapes were made in this way.

During the latter part of the year 1864, sometime in November, we had orders to move. It was not made known to us that we were to be exchanged but to be sent back South on terms never fully understood by us. Joyfully we boarded the freight cars at Indianapolis and set out for the long, slow journey toward Washington. We were sent down the Potomac and passed Fortress Monroe, Newport News and thence up the James river to our lines just below Richmond.

It was a ragged, emaciated lot of men, spiritless and weak from long confinement and ill treatment that once more entered Dixie. Our heroic fellow soldiers guarding the lines, looked on us with tender compassion for they were in dire straits themselves and the coming collapse of Confederate hopes cast a baleful shadow over the remnant of Lee's once invincible army. They appeared to us as men who realized that their fate was fixed but who were determined to meet the consequences without an exhibition of fear.

We went into camp for a time but whether for want of equipment or in compliance with terms of release we were dissmissed subject to call. The order for again entering ranks never came, for communications

Page 52

were cut off in all directions and the end of all things hoped for by the Confederates was at hand.

My only brother, W. R. Houghton who was a gallant soldier of the Second Georgia regiment Longstreet's corps, attempted to send me money at two different times to Camp Morton and had the letters safely mailed within the enemy's lines but it is needless to say I never received the robbed letters.

Dr. John A. Wythe an eminent physician now of New York, who was a prisoner also in Camp Morton, who seems to have had some influential friends outside the prison, wrote a series of articles on prison life in Camp Morton which were published in the Century Magazine. The story of the abuse, cruelty, graft, neglect, starvation and mortality connected with the conduct and management of that prison makes the history of Andersonville mild in comparison when the resources of the two governments are considered.

These articles can be found in the public library of Montgomery and should be read by every Southerner when the story of Andersonville prison is quoted as a reflection on the Confederacy.

COMMENTS ON OFFICERS I never saw General Beuregard but once during the war and that was shortly after the first battle of Manassas or Bull Run as the Federals call the first great fight of the war. He was a small dark nervous, soldierly looking man whose appearance indicated French extraction. He was regarded as one of the coming great commanders of the war but subsequent events did not add to his first reputation.

Page 53

I frequently saw General Joseph E. Johnston who achieved fame at the battle of Manassas. He had a clear cut, military air, rotund and of medium size. He gave out the impression that he was a man of quick perception and thoroughly self possessed. He wore a military goatee with side whiskers which contributed largely to his soldierly appearance. His subsequent career proved his ability as a tactician and strategist but fate denied him the glory of achieving any great victory.

General J. E. B. Stuart was a handsome, dashing, spectacular officer. He wore a broad brimmed, heavily plumed hat with a cockade and dressed in a fine suit of Confederate gray. His sword and belt, his boots and other equipments were bright and clean. He had long reddish brown beard and mounted a splendid charger. Altogether he was a picturesque commander but his showy appearance made him the target of the enemy. He was a brave and gallant officer and his reputation as a capable commander increased until his untimely death.

General Trimble, at one time our brigade commander was a sturdy but slow officer with great tenacity and purpose. He handled his brigade usually with skill and effect. He was not personally very striking but inspired confidence by his calmness and exhibition of utter fearlessness.

General E. M. Law at one time also our brigade commander was from Tuskegee, Alabama, and was small of statue but brave and alert. He usually kept close to his men in battle and was considered a reliable officer.

General Longstreet, our corps commander, was a large heavy set, determined looking man who was regarded as slow but sure and possessed the confidence

Page 54

of his men and the army generally. He was not showy or dashing nor was he very aggressive but held on to any advantages with great tenacity.

Colonel W. C. Oates who commanded the 15th Alabama regiment for some time was a handsome and brave leader. He was regarded by many as too aggressive and ambitious but he usually was well to the front and did not require his men to charge where he was unwilling to share the common danger.

RECONSTRUCTION The Southern States were in a deplorable condition just after the close of the war. The widows, orphans and the aged seemed to constitute the body of the population of hopeless whites. There was little left in a material way except the land. The negroes or freedmen as they were then called did not know what to do with their newly conferred boon of enfranchisement. Their former masters were dead or too poor to provide for them. Work stock were scarce and old broken down army horses were in great demand for plow purposes. Hundreds of negroes drifted about aimlessly, indisposed to work because they wished to enjoy freedom for a while without restraint. The southern people knew little else than farming except in the old way and they went to work to get a living from the soil as best they could. With an idle, shiftless horde of negroes turned loose it was natural that larceny and other crimes increased with amazing rapidity. Pigs fowls, cattle and farm produce had to be vigilantly guarded. Military government did little for the protection of the public and the scum of both armies preyed on the helpless and scattered inhabitants.

Page 55