Memoir and Memorials:

Elisha Franklin

Paxton,

Brigadier-General, C.S.A.;

Composed of his

Letters from Camp and Field While an Officer

in the

Confederate

Army, with an Introductory and

Connecting Narrative Collected

and Arranged by his

Son, John

Gallatin Paxton:

Electronic Edition.

Paxton, Elisha Franklin, 1828-1863

Funding from the Library of

Congress/Ameritech National Digital

Library Competition

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Jennifer Stowe

Images scanned by

Jennifer Stowe

Text encoded by

Carlene Hempel and

Natalia Smith

First edition, 1998

ca. 350K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1998.

Call number 973.78 P34 1907 (Davis Library, UNC-CH)

The electronic edition

is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

Library of Congress Subject Headings,

21st edition, 1998

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks

and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as '

and ' respectively.

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using

Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

LC Subject Headings:

- Paxton, Elisha Franklin, 1828-1863 -- Correspondence.

- Generals -- Confederate States of America -- Correspondence.

- Confederate States of America. Army. Stonewall Brigade.

- Confederate States of America. Army -- Officers -- Correspondence.

- Virginia -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives.

- Confederate States of America. Army -- Military life.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Personal narratives, Confederate.

- 1999-01-08,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1998-12-31,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1998-12-18,

Carlene Hempel

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1998-12-13,

Jennifer Stowe

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

Memoir and Memorials

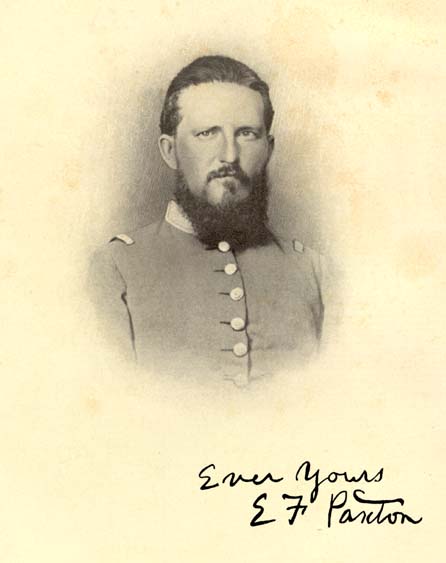

ELISHA FRANKLIN PAXTON

BRIGADIER-GENERAL, C. S. A.

COMPOSED OF HIS LETTERS FROM CAMP AND FIELD WHILE AN OFFICER IN THE CONFEDERATE ARMY, WITH AN INTRODUCTORY AND CONNECTING NARRATIVE COLLECTED AND ARRANGED BY HIS SON, JOHN GALLATIN PAXTON

"But

these our brothers fought for her,

At life's dear peril wrought for her,

So loved her that they died for her."

James Russell Lowell

"...

knows that the young man who composedly periled his

life and lost it

has

done exceedingly well for himself

without doubt."

Walt Whitman

PRINTED, NOT PUBLISHED

1905

PUBLISHER'S NOTE.

Mr. John G. Paxton, General Paxton's son, had this volume printed to preserve as a memorial the letters which his father had written from the scene of war. It was not intended that it should ever be offered for sale. The story which these letters tell is so full of heroism and pathos, so truly do they lay bare the noble soul of the writer and show the spirit which animated him and his comrades, that there has been a considerable demand for its publication. This house has therefore obtained Mr. Paxton's permission to take up the publication of the book, and offers the volume as originally published for private distribution without change of any kind, other than this announcement. It is a part of our arrangement with Mr. Paxton that we do not change even the title-page.

THE NEALE PUBLISHING CO.

NEW YORK,

August 5, 1907.

PUBLISHED AND SOLD BY

THE NEALE PUBLISHING COMPANY

FLATIRON BUILDING

NEW YORK

431 ELEVENTH STREET

WASHINGTON

Page v

FOREWORD

In this preliminary note are set forth the nature and purpose of this volume. Although printed, it is not published, and is intended only for distribution among General Paxton's family, friends, and comrades.

It is entitled "Memoir and Memorials." The Memoir is a sketch of General Paxton's life contained in the first chapter and in the subsequent narrative connecting the letters. The Memorials are the letters themselves. The book consists mainly of these letters, and it is to perpetuate them and thereby set forth the character of the writer that this book is printed.

General Paxton's career as a soldier, honorable though it was, would not justify its publication. His letters, written without reserve to the loved wife at home, not only show what manner of man he was and how he thought and felt while an actor in these trying times, but also are representative of his comrades, of whom he was one of the highest types. These letters thus originating are a true mirror of the writer, revealing his real qualities and characteristics with photographic accuracy. Showing as they do rare qualities of both mind and soul, they explain why he and his comrades were able so long to defend themselves against great odds. They also show how firmly was fixed in the mind of this man, a scholar and a lawyer, partly educated in the North, the belief that his State was

Page vi

sovereign and his first duty was to her. These letters are the material of which history is made. To the descendants of General Paxton they should be a stimulus to honorable lives and brave deeds. To his comrades in arms they recall, with sadness perhaps, the scenes through which they so honorably passed. To his son, the writer of these lines, he is not even a memory -- a tale that is told, that is all. At the knee of his widowed mother, he first learned to revere the name and virtues of his sire, and these letters, coming into his hands after manhood, brought to him a keener appreciation of those virtues. Ancestral pride is only good so far as it perpetuates the ancestral virtues. May these letters serve to do this and teach the descendants of this young soldier, who so freely gave his life for his fatherland, that they spring from another Bayard, a chevalier sans peur et sans reproche.

J.G.P.

INDEPENDENCE, MISSOURI,

September, 1905.

Page 1

CHAPTER I

MEMOIR

ELISHA FRANKLIN PAXTON was born March 4, 1828, in Rockbridge County, Virginia, the son of Elisha Paxton and Margaret McNutt. His grandfather, William Paxton, came to Rockbridge in its earliest settlement about the year 1745. He was a man of character and substance and commanded a company at the battle of Yorktown. Margaret McNutt was the daughter of Alexander McNutt and Rachel Grigsby. She was one of a family of eight sisters and four brothers, many of whom possessed marked intelligence and great force of character. Alexander Gallatin McNutt, Governor of Mississippi, was one of the brothers. Margaret McNutt Paxton possessed the family characteristics to a high degree. She was a granddaughter of John Grigsby, whose sobriquet was "Soldier John," going back to his service under Admiral Vernon in his expedition against Cartagena in 1741. He also commanded a company in the Revolutionary War. His soldierly qualities were stamped on his descendants, four of whom were brigadier-generals in the Confederate army, and many others were officers of lower rank who followed the stars and bars.

The Paxtons are descended from a soldier under Cromwell who emigrated with his Presbyterian comrades to the north of Ireland. As members of a hostile and an alien race their life there was one of conflict. Later they bitterly resented the action of the crown in compelling them to pay tithes for the support of the English Church, and

Page 2

largely on this account emigrated to America. Men, like plants, take on certain characteristics from the soil in which they live, the air they breathe and other physical surroundings. These militant churchmen found an appropriate home for the development of their sterling virtues in the beautiful valleys lying between the Blue Ridge and the Alleghanies -- the Paxtons in the rough but fertile lands of Rockbridge.

Here, on a beautiful spot in the foot-hills of the Blue Ridge, Frank Paxton first saw the light. There in his childhood he imbibed that love of freedom and devotion to duty which had marked his ancestors. As a boy he manifested unusual vigor of intellect. He attended the classical school of his cousin James H. Paxton, and at the age of fifteen entered the junior class at Washington College, where he received his degree of A. B. in two years. He then went to Yale, where he graduated in two years, and afterward took the law course at the University of Virginia. He was five feet ten inches high, heavily built and of great bodily strength. As an indication both of his physical and soldierly qualities he was known both at school and in the army as "Bull" Paxton. Dr. John B. Minor wrote the following of his course at the University of Virginia:

"Gen. E. F. Paxton, who fell at the battle of Chancellorsville, in May, 1863, was a student of law here, and a graduate in the Law Department of the University in 1849. As a student, none of his contemporaries acquitted themselves more satisfactorily, and in point of conduct, he was entirely exemplary. I think he could then have been not more than twenty-one years of age, but I have retained a lively recollection of him during the intervening period of forty-three years, so that whilst, after so great a lapse of time, I cannot recall particulars, he left on my mind an impression of unusual merit and a conviction that if he lived, he was destined not only to achieve

Page 3

eminence, but what in my estimation is far better, to attain to distinguished usefulness."

Upon his admission to the bar, he spent several years in the prosecution of land claims in the State of Ohio and resided there. He was successful in this enterprise and made some money. In 1854 he opened a law office in Lexington, Va., and married Miss Elizabeth White, the daughter of Matthew White of Lexington. This union was a most happy one and there were born of it four children, three of whom survived him -- Matthew W. Paxton of Lexington, Va., the writer, and Frank Paxton of San Saba County, Texas. Frank Paxton at once took a high rank in his profession and engaged in important business enterprises, among others becoming the President of the first bank in Rockbridge. His strength of character was shown by the fact that at this time, when the drinking of whiskey was a universal custom, he abstained altogether from its use, and continued to do so until his death. In 1860 failing eyesight compelled him to abandon his profession and he purchased a beautiful estate near Lexington, known as Thorn Hill.

In this beautiful home with wife and babes, the drum tap of '61 found him. It is needless to say that he had been taking an active part in the political events leading up to this. He was a man of intense feeling, when aroused, and had early adopted the view of the Constitution of the United States, which came to him from his fathers. To him the right of secession was as clear as the right of trial by jury. The State was sovereign and in the hot blood of his youth he believed the time had come to secede. So the war in which he entered was for the defense of his home and fireside and against an invading foe. It was as righteous to him as that waged by the Greeks at Thermopylæ and his life, if needs be, must be cheerfully surrendered in such a cause. In the contest in Rockbridge County over the election of delegates to the

Page 4

secession convention he took an active part in favor of the secession candidates. His great moral courage was conspicuous at the meeting held in Lexington, where he again and again attempted to overcome the large majority opposed to him. He was unsuccessful in this, and Rockbridge sent Union delegates to Richmond.

He had no special military training and entered the service as first lieutenant of the Rockbridge Rifles, and afterwards a part of the 27th Virginia Regiment, Stonewall Brigade. With this company, at the first call for troops in April, 1861, he marched to the front.

The pomp and circumstances of glorious war were present when on that bright spring morning his company and several others, with colors flying and martial music, took up the line of march from Lexington to Harper's Ferry. His young wife, with sad forebodings, wept until her handkerchief was wet with tears. In their last fond embrace he took this from her hand and as a reminder of her love carried it on many a bloody battle-field.

He wrote to his wife weekly and these letters, which well show the man and the times, make up substantially the subsequent chapters of this volume. They are edited only by omitting parts too personal to be of general interest.

Page 5

CHAPTER II

MEMORIALS

New Market, April 21, 1861.

I REACHED here this morning in good health and in spirits as good as could be expected, considering the bloody prospect ahead and the sad hearts left at home. It is bad enough. I have no time to think of my business at home. My duties now for my State require every energy of mind and body which I can devote to them. Do just as you please. If you think proper stay in town and leave all matters and keys on the farm in charge of John Fitzgerald.

Harper's Ferry, April 25,1861.

We reached this place on Tuesday morning. Instead of being fatigued, I was rather improved by the trip. Here we have all the comforts which we could expect, good food and comfortable quarters, better than generally falls to a soldier's lot. I have enough to occupy every moment of my time in preparing the company for the service which we may expect to see before long. They have much to learn before they can be relied on for efficiency. I regret that my eyes are no better as it is necessary for me to read much for my own preparation. Try, Love, to make yourself contented and happy. I would not like to think that I was forgotten by dear wife and little ones at home, but it would give me a lighter

Page 6

heart to think that they appreciated the necessity of my absence, and the high importance of a faithful discharge of my present duties. My eyes will not enable me to write more without risk of injury to them.

Harper's Ferry, April 29, 1861.

I received your letter by Mr. Campbell and was very happy to hear from you. Nothing could be half so interesting as a line from dear wife and little ones at home. Be cheerful and act upon the motive which made me leave you to risk my life in relieving my State from the peril which menaces her. I hope I may see you again, but if never, my last wish is that you will make our little boys honest, truthful, and useful men. Last Thursday night, I experienced for the first time the feeling of coming in contact with the bullets, bayonets, and sabres of our enemies. We were called up suddenly upon the expectation of an engagement which proved a false alarm. Now I know what the feeling is, and know I shall enter the struggle, when it comes, without fear. Next to the honor and safety of my State in her present trial, the happiness of wife and little ones lies nearest my heart. My health was never better. I have spent two nights on duty in the open air without suffering, and feel assured now that my health will not suffer by such exposure.

Kiss the little ones for me and never let them forget "papa gone," perhaps forever. Accept for yourself every wish which a fond husband could bestow upon a devoted wife.

Harper's Ferry, May 4, 1861.

Write very often. Nothing can be so interesting to me as your letters. Some of the other wives, you think, get more letters than you do, and you women measure your husband's love by the number and length of their letters. I will write to you, Love, about once a week and half a

Page 7

page at a time. I cannot with justice to my eyes write longer letters. This will be handed to you by Maj. Preston, who will tell you everything you want to know. Kiss the children for me, and for yourself take my best love.

Harper's Ferry, May 18, 1861.

My wife, I have no sweeter word than this to call the dear little woman at home, with whom my happiest reminiscences of the past and fondest hopes of the future have ever been associated. (You speak of dreams; I had one of you, that we were married again, and thought we had a very nice time of it.) We have moved from our station in the mountain back to town. Here we have very pleasant quarters, in which I think it likely we will remain until we have a battle. When this will be, it is impossible to say, but is not expected immediately. I received the green flannel shirt and put it on for the first time to-day. It is very comfortable and valued the more because made by the hands of my dear wife. Present my kind regards to John (the gardener) and hand him the enclosed order on Wm. White. Present my kindest regards to Jack, Jane, and Phebe (slaves). Kiss the children for me, and for yourself take a husband's best love.

Martinsburg, May 24, 1861.

After mentioning it in your letter, you add in a postscript, "Don't forget to tell me where your books are." I told you in my last letter, but wish I had not. Really, Love, I do not wish you to be annoyed with my business. I wish you to be very happy, and this I know you cannot be if you undertake to harass yourself with my business. Go out home occasionally and see how matters are going on, but do not trouble yourself any further. So, Love, if any one calls on you about my matters, tell them my instructions to you were to have nothing to do with them. Write no

Page 8

more about business, but about my dear wife and little ones, if you wish to make your letters interesting. We have been kept moving since we came here. We have a hard time, but have gotten used to it. The men were discontented and unmanageable at first, but are now very well satisfied. This section now is in most complete condition for defense, abundantly able, I think, to resist any force which can be made against it. Troops have been lately arriving in large numbers. I have no idea when the battle will be fought. Many of us will fall in it, but I have no doubt of our success. And now, my darling, good-bye until I write again.

Harper's Ferry, June 5, 1861.

I received your sweet letter of the 1st inst. on yesterday, and the return of Mr. McClure gives me the opportunity of sending you a line in return for it. When McClure came here to see his son, a member of our company, I offered him my hand, which he took, and thus I have made friends with the only man on earth with whom I was not on speaking terms. I bade a cordial good-bye to Wilson when I left home, which I think he returned in the same spirit of good-will. I now may say that there is no one on earth for whom I entertain anything but feelings of kindness, and I think I have the ill will of no one. In view of the danger before me, it is indeed gratifying to feel that I have the good-will of those I leave behind, and that I leave no one who has received a wrong from me which I have not regretted and which is not forgiven. If Mr. McClure calls on you, for my sake treat him with the utmost kindness. Send me the miniature. Good-bye, dearest.

Winchester, June 15, 1861.

On Tuesday last we marched on foot from Harper's Ferry to Shepherdstown, thence seven miles farther up

Page 9

the Potomac. There we remained a day and a half, when we were ordered to this place, on foot again, and reached here, forty miles, in a day and a half. How long we remain here, or when we move again, I have not an idea. I hardly thought I would have been able to stand forty miles' walk so well. Last night I felt very tired, but this evening entirely recovered. The last three nights I have slept in the open air on the ground, and never enjoyed sleep more. I saw Capt. Jim White to-day, and his college boys. Lexington has been well drained of its youth and manhood. I heartily wish, Love, that I was with you again, I hardly know what I would not give for one day with wife and little ones. But I must not think of it. I would soon make myself very unhappy if I suffered my mind to wander in that direction. I ought to be grateful to Omnipotence for such a love as that which you give me. Blood and kindred never made a stronger tie. We have just received orders to hitch up again -- for what destination I do not know. Harper's Ferry has been abandoned by our forces, and hereafter direct your letters to the address below. Kiss the dear little baby boys for their absent papa, and for yourself accept the best love of a fond husband.

Camp Stephens, near Martinsburg, June 30, 1867.

I wrote to you last Monday, and immediately was ordered off on another expedition, in which I have been engaged the greater part of the past week. I was in charge of a small force engaged in destroying a bridge some ten miles from our camp on the railroad. It was a rather dangerous expedition, but I have become so much accustomed to the prospect of danger that it excites no alarm. I thought when we left Winchester that we certainly would have had a battle in a very few days; but two weeks have elapsed, and there is, I think, less reason to expect one now than there has been heretofore. The enemy is encamped

Page 10

on the opposite side of the Potomac some ten miles from here, but, I am satisfied, in less force than we have in this vicinity. Under such circumstances, if we get a fight we shall have to cross the river and make the attack. Our picket-guards occasionally come in contact, and the other day one of the Augusta Cavalry was severely wounded. I hope you are having good success as a farmer; so, if I should be left behind when the war is over, you may be able to take care of yourself. You think, Love, I write very indifferently about it. As to the danger to myself, I am free to confess that I feel perhaps too indifferent. Not so as to the separation from loved wife and little ones at home. I never knew what you were worth to me until this war began and the terrible feeling came upon me that I had pressed you to my bosom, perhaps, for the last time. I always keep upon my person the handkerchief which I took from your hand when we separated. It was bathed in tears which that sad moment brought to the eyes of my darling. I will continue to wear it. It may yet serve as a bandage to staunch a wound with. I keep one of your letters, which may serve to indicate who I am, where may be found the fond wife who mourns my death. May neither be ever needed to serve such a purpose! Enclosed I send a letter from James Edmonson to his grandmother. Say to Mrs. Chapin that she may rely upon my acting the part of comrade and friend to George. Kiss the children for me, and for yourself accept all that a fond lover and husband can offer.

Near Winchester, July 8, 1861.

The last week has been one of patient waiting for a fight. On Monday, the 1st inst., I was ordered by Col. Jackson to go to Martinsburg and burn some engines, at which I was engaged until Tuesday morning, when I received an order to join my company, accompanied with the information that the enemy was approaching and our force had

Page 11

gone out to give him battle. I obtained a conveyance as speedily as I could, and the first intelligence of the fight I received from my regiment, which I found retreating. My company, I was pleased to learn, had fought bravely. On Wednesday morning we took our stand ten miles this side of Martinsburg, and there awaited the approach of the enemy until Sunday morning, when we retired to this place, three miles from Winchester. This we expect to be our battle-field. When it will take place it is impossible to say. It may be to-morrow, or perhaps not for a month, depending upon the movements of the enemy. I look forward to it without any feeling of alarm. I cannot tell why, but it is so. My fate may be that of Cousin Bob McChesney, of whose death I have but heard. If so, let it be. I die in the discharge of my duty, from which it is neither my wish nor my privilege to shrink. The horsetrade was entirely satisfactory. Act in the same way in all matters connected with the farm. Just consider yourself a widow, and, in military parlance, insist upon being "obeyed and respected accordingly." Pay your board at Annie's out of the first money you get. She may not be disposed to accept it, but I insist upon it. I do not wish to pay such bills merely with gratitude. Newman is still in the army, but I have not seen him for a month. I called to see him the other day, but he was not at his quarters.

It is now nearly three months since I left home, and I hardly know how the time has passed. All I know is that if I do my duty, I have but little leisure. I am used to the hardships of the service, and feel that I have the health and strength to bear any fatigue or exposure. Sometimes, as I lie upon the ground, my face to the sky, I think of Matthew's little verse, "Twinkle, twinkle, little star," and my mind wanders back to the wife and little ones at home. Bless you! If I never return, the wish which lies nearest to my heart is for your happiness. And now, my darling, again good-bye. Kiss little Matthew and Galla

Page 12

for me, and tell them Papa sends it. Give my love to Pa and Rachel, and for yourself accept all that a fond husband can give.

Manassas, July 23, 1861.

My Darling: We spent Sunday last in the sacred work of achieving our nationality and independence. The work was nobly done, and it was the happiest day of my life, our wedding-day not excepted. I think the fight is over forever. I received a ball through my shirt-sleeves, slightly bruising my arm, and others, whistling "Yankee Doodle" round my head, made fourteen holes through the flag which I carried in the hottest of the fight. It is a miracle that I escaped with my life, so many falling dead around me. Buried two of our comrades on the field. God bless my country, my wife, and my little ones!

The following is taken from the Lexington "Gazette," dated

August 8, 1861:

"It is due to our worthy fellow-citizen, Mr. E. F. Paxton, or rather it is due to the county of Rockbridge, to claim credit for Mr. Paxton's conduct, which he has been too modest to claim for himself. A correspondent of one of the Richmond papers a short time since spoke of a Virginian who had been lost from his company during the fight, and fell in with the Georgia Regiment just as their standard-bearer fell. The lost Virginian asked leave to bear the colors. It was granted to him. He bore them bravely. The flag was shot through three times, and the flag-staff was shot off whilst in his hands. But he placed the flag on the Sherman Battery, and our brave men stood up to their colors and took the battery. That lost Virginian was E. F. Paxton, of Rockbridge."

Page 13

LETTER TO THE EDITOR OF THE LEXINGTON

"GAZETTE."

Camp Harmon, August 24, 1861.

I do not merit the compliment paid me in a paragraph contained in a recent number of your paper, which gives me the position of leading a portion of the 4th Va. and 7th Geo. in the charge upon the enemy's batteries. The 4th Va. was led by its gallant officers, Preston, Moore and Kent, and it was by order of Col. Preston, who was the first to reach the battery, that I placed the flag upon it. The 7th Geo. was led by one whom history will place among the noblest of the brave men whose blood stained the field of Manassas -- the lamented Bartow; when he fell, then by its immediate commander, Col. Gartrell, until he was carried, wounded, from the field; and then, until the close of the day, by Major Dunwoodie, the next in command.

If the paragraph means, not leading, but foremost, the compliment is equally unmerited. In the midst of the terrible shower of ball and shell to which we were subjected, and whilst our men, dead and wounded, fell thick and fast around us, my associates in the command of our company, Letcher, Edmondson and Lewis, were by my side; the dead bodies of my comrades, Fred Davidson and Asbury McClure, attest their gallantry; and the severe wounds which Bowyer, Moodie, Northern, Neff and P. Davidson carried home show where they were. I witnessed, on the part of many of our company around me, heroism equal to that of those I have named; but as others whom, in the excitement of the occasion, I do not remember to have seen, did quite as well, I may do injustice to name whom I saw. Compared with the terrible danger to which we were exposed at this time, that seems trifling when, at a later hour and in another part of the field, the flag was placed on some of the guns of the Rhode Island battery, which the enemy were then leaving in rapid retreat, the

Page 14

day being already won, and the glories of Manassas achieved.

Again, I did not get the flag when Bartow fell, but sometime after, from the color-sergeant of the regiment, who, wounded, was no longer able to bear it.

The work done by Jackson's Brigade and the 7th Geo., and the credit to which they are entitled, is stated in the following extract from the official report of Gen. McDowell: "The hottest part of the contest was for the possession of this hill with a house on it." Here Jackson and his gallant men fought. Here the work of that memorable Sabbath was finished.

Manassas, July 26, 1861.

I wrote a short note to you on Tuesday, advising you of my escape from the battle of Sunday in safety. Matters are now quiet, and no prospect, I think, of another engagement very soon. When I think of the past, and the peril through which it has been my fortune to pass in safety, I am free to admit that I have no desire to participate in another such scene until the cause of my country requires it. Then the danger must be met, cost what it may. How I wish, Love, that I could see you and our little ones again! But for the present I must not think of it. Just as soon as the public service will permit I will be with you. The result of the battle has cast a shade of gloom over many who mourn husband, brother and child left dead on the field. Of those of our company who went into the thickest of the fight, at least one-half were killed or wounded. Some others escaped danger by sneaking away like cowards. The other companies from our county suffered as severely as ours. It seems, Love, an age since I have heard from you. You must write oftener. Why is it that you have not sent the daguerreotype of yourself and the children? Send me, by the first opportunity, another shirt just like that which you last sent me.

Page 15

I will lay that by -- as it has a hole through it made by a ball in the battle -- as a memento of the glorious day. Do not send me any more clothing until I write for it, as I do not wish more than absolute necessity requires, having no means of carrying it with me.

I wish you would call upon Mrs. J. D. Davidson for me, and say to her she has reason to be proud of her brave boy. It was by the heroic services of men like him who have sacrificed their lives that the battle was won. He fell just as he and his comrades were taking possession of a splendid battery of the enemy's cannon, and those who defended it were flying from the field. And now, Love, good-bye. I think you need have no apprehension about my safety for some weeks at least. It is not probable that we shall have another battle very soon; and if we do, as our brigade was in the thickest of the fight before, we will not be so much exposed again. Give my love to Pa, Rachel, Annie, and all my friends. Kiss our dear little ones for their absent papa, and for yourself accept a husband's best love.

Manassas, August 3, 1861.

I reached here last night after spending a day in Staunton. When I reached there I found the militia of Rockbridge, and some of the officers insisted upon my remaining a day to aid them in raising the necessary number of volunteers (270) to have the others disbanded and sent home. I was very glad, indeed, that it was accomplished and the others permitted to return home and attend to their farms. I found, upon reaching Manassas, that our encampment had been removed eight miles from there, in the direction of Alexandria; and after a walk of some three hours I reached here about nine o'clock at night, somewhat fatigued. I do not know what our future operations are to be; but think it probable that we shall remain here for some time in idleness. I am free to confess

Page 16

that I don't like the prospect; without any employment or amusement, the time will pass with me very unpleasantly, and such soldiering, if long continued, I fear, will make most of us very worthless and lazy; perhaps send us home at last idle loafers instead of useful and industrious citizens. Such a result I should regard as more disastrous than a dozen battles. In passing along the road from Manassas, the whole country seemed filled with our troops, and I understand that our encampment extends as far as eight miles this side of Alexandria. I think we have troops enough to defend the country against any force which may be brought against us.

Since this much of my letter was written, Lewis has handed me your note of 25th ult. You say you are almost tempted, from my short and far between letters, to think that I do not love you as well as I ought. You are a mean sinner to think so. Just think how hard I fought at Manassas to make you the widow of a dead man or the wife of a live one, and this is all the return my darling wife makes for it. If I was near enough I would hug you to death for such meanness. In truth, Love, I may say that I never closed one of my short notes until my eyes began to smart. Sometimes I did not wish to write. When we were for some time on the eve of a battle I did not wish to write lest you might be alarmed for my safety. Until the last month, when danger seemed so threatening, I think I have written once a week. But, Love, when you doubt my affection, you must look to the past, and if the doubt is not dispelled, I can't satisfy you, and you must continue in the delusion that the truest and steadiest feeling my heart has ever known -- my love for you - has passed away.

I know, Love, you think I exposed myself too much in the battle. But for such conduct on the part of thousands, the day would have been lost, and our State would now have been in the possession of our enemies. When I think of the result, and the terrible doom from which we are

Page 17

saved, I feel that I could have cheerfully yielded up my life, and have left my wife and little ones draped in mourning to have achieved it. Our future course must be the same, if we expect a like result.

Centreville, August 7, 1861.

I have received from Gen. Jackson the appointment to act as his aid, and wish you to send my uniform coat and pants by Rollin, Kahle or some one of our men, whichever comes first. Switzer is just leaving, and I have not time to write more.

Camp Harmon, Manassas, August 18, 1861.

I promised in my letter of last Sunday to write to you every Sunday, and I will to-day, but I ought not, as you have not answered my last. I find abundance of employment in my new position, but I like it all the better on this account. The last week has been almost one continuous dreary rain, making soldier life more comfortless than usual. I think I shall quit the use of tobacco altogether as I am inclined to believe that it injures me. I am very glad that my duties require of me very little writing, for what little I do satisfies me that my eyes have not improved, and that it is not safe to use them much. They pained after the writing which I did last Sunday to Wm. White and yourself. I think we have the prospect of an idle life here for some time to come. I am free to say I don't like it. I would prefer to move into Maryland for an assault upon Washington and a speedy close of the war. But I suppose those in command know best what should be done.

Camp Harmon, August -- , 1861.

I had a chance to show my gallantry last week. I was directed one night to pass a Mr. Pendleton and his party

Page 18

through our line of sentinels. I reached the party about ten o'clock, and found the party consisting of an old gentleman driving the carriage, and in it the wife of his son with three or four children. She told me they were going to stay a mile beyond, with a lady to whom she had a letter, and were on their way to Virginia from Washington. Knowing the difficulty they would have in passing the sentinels of the other camps, I volunteered to accompany them. But when they reached the house where they expected to stay all night I delivered their letter and was told they could not be taken in, as the house was full of sick people, and that there was no other house in the village where there was any prospect of getting them in. The only chance then was to take the road and run the chance of getting into a farm-house or travel all night. I went with them, and succeeded in getting them lodging at a farm-house three miles further on. She was profuse in her expressions of gratitude, and I took leave of them and walked back four miles to our camp, which I reached about one o'clock, well paid for my trouble in feeling conscious that I had done a good deed.

Camp Harmon, September 1, 1861.

I wish very much this war was over, and I could be with you again at our home. There you remember, Love, you used to read, last December, to me of the stirring events in South Carolina; but we never dreamed that such a struggle would result as that in which we are now engaged, that the husbands and fathers among our people would be called upon to leave wives and children at home to mourn their absence whilst mingling in such a scene of blood and carnage as that through which we passed on the 21st of July. But so it is. How little we know of the future and our destiny! Dark as the present is, I indulge the hope it may soon change, and I may be with you again,

Page 19

not for a short visit, but to stay. Whilst such is the fond hope, when I look within my heart I find an immovable purpose to remain until the struggle ends in the establishment of our independence. Can the fond love which I cherish for you and our dear little children be reconciled with such a purpose? If I know myself, such is the fact. But, Love, my eye hurts me. It is sad to think of it, and that it disables me for life. It deprives me of the pleasure of reading for information and pleasure, unfits me for most kinds of business, and deprives me of the means of earning an independent support, which I feel I could do if I had my sight. The present is dark enough, but the future seems darker still, when I think of my return home, possibly made a bankrupt by the confiscation of my Ohio land, and then without means of earning a support or paying for my farm. I must not think of it now; it will be bad enough when it comes. I ought not to press my weak eye any farther. Kiss our dear little ones for me. Speak of me often to them. Never let them forget their "papa gone," who loves them so well.

Camp Harmon, September 8, 1861.

I will devote to a letter to my loving little wife at home part of this quiet Sunday evening. Sinner as I am, I like to see something to mark the difference between Sunday and week-day. We have no drills on Sunday, and generally two or three sermons in different parts of the camp, which was not so some time since, when everything went on as on every other day. This morning we had a sermon from Bishop Johns, who dined with us, and this afternoon he preaches again. We expect this evening a distinguished visitor, Mrs. Jackson, so we shall have mistress as well as master in the camp. The General went for her to Manassas yesterday evening, but returned without her, finding she had gone to Fairfax, where he

Page 20

immediately started in search of her. When she arrives his headquarters, I doubt not, will present much more the appearance of civilization. But before she is here long she will probably be startled with an alarm, false or real, of a fight, which will make her wish she was at home again.

Fairfax C. H., September 16, 1861.

I did not write my regular Sunday letter to you on yesterday. As usual, after breakfast I left the camp on duty, and did not return until dinner, when, very tired, I slept a couple of hours. Very soon I got orders to leave again for a ride of thirteen miles, and did not get back until bedtime. This morning we all left for our new encampment, where all are comfortably quartered.

I received your letter of 9th inst. a few days since. Indeed, Love, the perusal of your letters gives me more pleasure than I ever received from any other source. Should I not be happy to know there is some one in the world who loves me so well and looks with such deep interest to my fate? To be with you again is the wish which lies nearest my heart. But the duty to which my life is now devoted must be met without shrinking. Before the war is done many, I fear, must fall, and I may be one of the number. If so, I am resigned to my fate, and I bequeath to you our dear little boys in the full assurance that you will give to my country in them true and useful citizens. I wish, Love, the prospect were brighter, but indeed I see no hope of a speedy end of this bloody contest.

Camp near Fairfax C. H., September 22, 1861.

I am indebted to you for much pleasure afforded by your sweet letter of 16th inst. I know, Love, my presence is sadly missed at home, but not more than in my lonely tent I miss my dear wife and her fond caress. I am sure,

Page 21

too, you are not more eager in your wish for my return, than I am to be with you. But I feel sure you would not have me abandon my post and desert our flag when it needs every arm now in its service for its defence. To return home, all I have to do is to resign my office, a privilege which a man in the ranks does not enjoy. Then your wish and mine is easily fulfilled, but in thus accomplishing it I would go to you dishonored by an exhibition of the want of those qualities which alike grace the citizen and the soldier. An imputation of such deficiency of manly virtues I should in times past have resented as an insult. Would you have me merit it now? I think not. My love for you, if no other tie bound me to life, is such that I would not wantonly throw my life away. But my duty must be met, whatever the expense, and I must cling to our cause until the struggle ends in our success or ruin, if my life lasts so long. I trust I have that obstinacy of resolution which will make my future conform to such sentiments of my duty. Mrs. Jackson took leave of us some days since, as the General was not able to get quarters for her in a house near our present encampment. I rode, between sunset and breakfast next morning, some thirty miles to secure the services of a gentleman to meet her at Manassas and escort her home. In return for this hard night's ride she sent me by the General her thanks in the message that she "hoped I might soon see my wife." You hope so too, don't you, Monkey? I was well paid for my trouble in the consciousness of having merited her gratitude.

I stopped at Mr. Newman's camp the other day to see him, but learned from Deacon that he was at home and that little Mary was dead. I sympathized deeply with them in the sad bereavement. I learned from the Rev. Dr. Brown, who reached here from Richmond this morning, that he saw Matthew at Gordonsville, on his way here. I suppose he will come to see me when he arrives.

Yesterday I was down the road some ten miles, and,

Page 22

from a hill in the possession of our troops, had a good view of the dome of the Capitol, some five or six miles distant. The city was not visible in consequence of the intervening woods. We were very near, but it will cost us many gallant lives to open the way that short distance. I have no means of knowing, but do not think it probable the effort will be made very soon, if at all. I saw the sentinel of the enemy in the field below me, and about half a mile off, and not far on this side our own sentinels. They occasionally fire at each other. Mrs. Stuart, wife of the Colonel who has charge of our outpost, stays here with him. Whilst there looking at the Capitol I saw two of his little children playing as carelessly as if they were at home. A dangerous place, you will think, for women and children. Remember me to Fitzgerald and his wife, and say that I am very grateful for what they have done for me. And now, Love, I will bid you good-bye again. Kiss little Matthew and Galla for me.

Camp near Fairfax C. H., September 28, 1861.

I will close a delightful Sunday evening in answering your last letter, received a few days since. I heartily sympathize with you, Love, and our dear little Matthew in your wish for my return. My absence does not press more heavily upon your heart than upon my own. But we must not suffer ourselves to grieve over the necessity which compels our separation. We must bear it in patience, in the hope that when I return we shall love each other all the better for it. I have had the offer from Gov. Letcher of a Commission as Major. I was much flattered by the compliment, but declined it, as I would be assigned to duty at Norfolk. Feeling that I was more pleasantly situated and could render more efficient service here, I preferred to remain. I was very much tempted to accept it, from the consideration that it would probably afford

Page 23

me an opportunity of passing by home on my way; but I thought this should not make me deviate from what my Judgment approved as my proper course. I replied that I would accept the appointment if assigned to duty in this brigade, but would not leave it for the sake of promotion.

The weather begins to feel like frost, and hereafter we shall, I fear, find a soldier's life rather uncomfortable. Sleeping in the open air or thin tents was comfortable a few weeks since; but when the frost begins to fall freely, and the night air becomes more chilly, lying upon the ground and looking at the stars will not be so pleasant. Then we shall think in earnest of home, warm fires, and soft beds. I think I shall get used to it. I have seen many ups and downs and begin to fancy that I can bear almost anything. In November I suppose we shall find comfortable winter quarters somewhere, or shall build log cabins and stay here. I went down to see Mat some days since, but did not find him.

Jim Holly came this evening and tells me he has the pair of pants which you sent me, and that Waltz will bring some more things for me. You need not get the overcoat; my coat for the present answers a very good purpose, and if I find hereafter that I need an overcoat, I will send to Richmond for it.

And now, Love, as I have taxed my eye about enough, I will bid you good-bye. I trust that you will make yourself contented. I shall be all the happier knowing that you are so. Give a kiss to our dear little boys for me; for yourself accept a fond husband's best love.

Camp near Fairfax C. H., October 6, 1861.

Your letter of October 1st was received on yesterday, and I am very much gratified at the cheerful feeling which it manifests. It shows, too, that you are giving a very

Page 24

commendable attention to the business under your charge, and give promise, if the war lasts, of your being a first-rate business woman. You have your mind set in the right direction, for it seems as if the war would be interminable, and the sooner you learn how to take care of yourself the better it will be. Times are very dull with us here. Our troops are but a mile or so distant from the enemy, -- so near that our pickets, it is said, occasionally meet and converse with theirs, swap newspapers, tobacco, whisky, etc. Judging from the newspapers, one would think we were on the eve of a battle every day, but here there seems little apprehension of it. We may have a battle, but then again we may not. On the whole, the soldiers would just as lief fight as not. We are going to have a sermon this evening, and I will bid you good-bye to listen to it. Kiss our dear little boys for me, and remind them of me. I should regard their forgetting me as the saddest loss sustained by my absence from home. Think of me often, Love. My fondest hope, the dearest wish of my heart, is to be with you again. Remember me to the servants, and to Fitz and his wife, to Annie, Rachel and my friends.

Camp near Fairfax C. H., October 13, 1861.

I have received your last letter, and will devote an hour of this quiet Sabbath to giving you one in return for it. I am very sorry to hear that, having spared your team so long, they have called for it at last. I had hope they would let it alone in consideration of my absence from home in the service of the State, and consequently my inability to provide means of supplying its place, as others who have remained in the county can. It is nearly equivalent to a loss of our wheat crop, besides the great injury the horses must sustain in such a trip. For them I feel a sort of attachment, as for everything else at home, and should hate very much to see them injured.

Page 25

We are having a very quiet and dull time. The fault I have with my present position is that I have too little to do. Jackson has been promoted again, and is now Major-General. It is, indeed, very gratifying to see him appreciated so highly and promoted so rapidly. It is all well merited. We have, I think, no better man or better officer in the army. I do not know to what position he will be assigned. But this brigade will part with him with very much regret. I shall be very reluctant to leave my place on his staff for any other position.

I am sorry to inform you on the money question that I am dead broke, and gratified to say that I do not expect it to continue many days. I have about $300 pay due me from the government, and sent by a friend who went to Richmond a few days since to draw the money, but he has not returned. Say to Mrs. Fuller I see Sam frequently and he is very well. Kiss the children for me, and think of me often.

Centreville, Va., October 20, 1861.

Letters prompted by an affectionate anxiety for my fate, bringing intelligence that wife and children are happy in the enjoyment of every necessary comfort at home furnish in their perusal the happiest moments of the strange life I am leading. Such interchanges of letters are a poor substitute for the happiness which we have found in each other in times past; but it is all we can have now. Our separation must continue until this sad war runs its course and terminates, as it must some day, in peace. Then I trust we may pass what remains of life together, loving each other all the better from a recollection of the sadness we have felt from the separation. I am sometimes reminded of you, and the strong tie which binds me to you, by odd circumstances. The other day I saw an officer, who, like myself, has left wife and children at home, riding by the camp, with another woman on horse-back,

Page 26

from a pleasure excursion up the road; and I could not help feeling that in seeking pleasure in such a source he was proving himself false to the holiest feeling and the highest obligation which is known on earth. I thought if I had acted thus faithless to you and our marriage vow, I should feel through life a sense of baseness and degradation from which no repentance or reparation could bring relief. If I know myself, I would not exchange the sweet communion with my absent wife, enjoyed through the recollections of the past and the hopes of the future, for any temporary pleasure which another might offer. I would rather live over again in memory the scenes of seven long years, when we talked of our love and our future, our ride to Staunton on our wedding-day, and our association since then, chequered here and there with events of sadness and sorrow, than accept any enjoyment which ill-timed passion might prompt me to seek from another. I trust, Love, this feeling may grow with every day which passes, and that I may always have the satisfaction of knowing my devotion and fidelity merit the affection which your warm heart lavishes upon me.

I have received a commission as Major in the 27th Regiment, and expect to change my quarters to-morrow. I leave my present position with much reluctance.

Centreville, Va., November 3, 1861.

The Frenchman and the wheat crop give you a peck of trouble, but you have the gratification of knowing you are not alone in your misery. We have occasionally some little of it here. Night before last and yesterday, for instance, we had a storm of wind and rain which blew over many of the tents, turning their inmates out in the weather, and rendering it almost impossible to cook anything to eat. We thought it bad enough here, but I doubt not those regiments which were on picket without tents

Page 27

fared even worse than we did here. If you who have brick houses and dry quarters to live in have your troubles, those of us here fare worse. This is poor consolation, it is true. I thought when I came here that I was settled for a while at least as Major of the regiment, but last week I got an order from Gen. Smith to take charge of the roads used by the army and have them put in repair. The appointment implied an opinion that I possess the energy and industry to have the work done, and I am gratified so far as the compliment; but it is a post which involves much hard work and affords no opportunity for winning laurels. It is, however, a post of much importance, and I shall spare no effort to justify the favorable opinion which induced my appointment.

The wind blows cold, Love, and as I write in my tent without fire, I will draw my letter to a close. Say to your father that the cloth is just suited to the purpose for which I need the coat this winter -- out-of-door life in all sorts of weather. I have another message which I have thought for some time of sending him. It is this: the principal part of my estate consists of land in Ohio, the loss of which -- and I have but little hope of anything else -- breaks me. My other property, under the depreciation which the war is likely to produce, will not pay my debts. I think proper to communicate this, so that if he thinks proper to change his will, he can do so and make such provision for you as he deems best. The future is dark enough, I am sure; but I shall go on here in a faithful discharge of my duties, trusting that it may some day be brighter.

Winchester, November 10, 1861.

I owe you a letter to-night, and will pay the debt with a very short one. We got here about sunset from Strasburg, after a tiresome day's march, and have been occupied up to this time, nine o'clock, in pitching our tents and

Page 28

getting some supper. The latter we were so fortunate as to get from a box which some kind friends sent to Col. Echols. What shall be our next destination I have no idea, but think it probable we shall winter somewhere in this quarter. I am tired and sleepy, Love, and I will bid you good-night. Kiss the children for me, and for yourself accept the best love a fond husband can offer.

Camp near Winchester, November 17, 1861.

Soldiering for the past week has been a hard business. For two or three days we had cold rains, and the balance of the time very severe winds. The wind is perhaps more severe than the rain, as it makes our outdoor fires very uncomfortable, it being doubtful whether it is best to stand the cold or the smoke. The weather feels now as if the campaign was over and we must soon go into winter quarters. If we get houses, I presume it will be shanties, such as the men can build for themselves out of logs and clapboards. This they could do in a very short time. But cotton tents will be bad quarters for snowy, freezing weather; and if we do not have better, I fear we shall lose much from disease this winter. My health at present is very good, and I think I stand the service as well as any one else in it. Last night I slept very comfortably with the assistance of two sheepskins and five blankets.

Since our arrival here, there has been a very general congregation of officers' wives at the farm-houses in the neighborhood, and I think it likely to continue until women and children are as common in the camp as blackberries in August. So I have little hope of seeing you here, but think the Yankees will go into winter quarters before long. They will discover that a winter campaign in this part of the sunny South, with the snow a foot deep and ice everywhere, is uncomfortable, and will give us a few months' rest. I hope then to be able to get a short furlough to see my dear little wife and babies at home.

Page 29

And now, Love, I will take leave of you. I sympathize deeply with you in your approaching illness, and hope for your safe and speedy recovery. Remember me kindly to your father, and say that I am very grateful for the assistance which he has given you in my absence.

Winchester, November 24, 1861.

I have read over again this morning your two last letters, and whilst they inspire a feeling of happiness that there is a dear wife at home whose love I prize and cherish more than anything else on earth, yet they make me feel sad that she is unhappy. I think, Love, I take a very calm and just view of my duty and of the future. I think I should remain in the war so long as my services may be needed, although it be at the sacrifice of personal comfort and pecuniary interest, and compels a separation from the loved wife with whom the happiest recollections of the past and the fondest hopes of the future are inseparably connected. It will cost me all this, and perhaps my life. If so, I will but share the fate of thousands who must fall in the contest, doing that which their own judgment and the common sentiment of the country decide to be their duty. If I survive the end of the war, I shall then quit the service, I trust, with the good opinion of my comrades and with my own approval of the fidelity and efficiency with which my duty has been discharged. Poverty and want may then mark my path through life, but I do not expect it, and I do not fear it. I have a strong faith in my capacity to earn a livelihood anywhere, -- industry meets its reward, -- and to secure every comfort which may be necessary for the happiness of the wife and little ones who bless my home with their presence. Here I'll change the subject to say that while writing our postman has arrived with your letter of 20th inst. I really think, Love, you are doing finely, and your providence in procuring salt in

Page 30

advance of the rise in the market exhibits qualities to fill the place of a soldier's wife which need only a little necessity for developing them. I am glad, too, to hear you say you are too busy to be lonesome; that is a step in the right direction. That is the reason why I was sorry to give up the place of road overseer at Manassas. It gave me abundant employment for mind and body, made me sleep well and eat well. Now I have a job as member of a court martial which requires me to go to Winchester every day, where the court is in session from 9 A.M. to 3 P.M.

Winchester, December 1, 1861.

I have received your last letter, and am sorry that you write so despondently of the future. It would be sad, indeed, for me to think that day would ever come when the dear wife and little ones whose happiness and comfort have been the chief aim of my life, should be dependent. You would not be more grieved, I am sure, than I would be at such a prospect, and its reality could not distress you more than it would me, if I should be alive to witness it. But, Love, it does not become either of us to harass ourselves with trouble which the future has in store for us. Mine at present is not blessed with as many comforts as I have seen in times past; but it is the case with many thousands who feel impelled with a sense of patriotism and duty to bear it in patience, and I shall try to follow their example. When I sent the message to your father I knew that what he would have to give you out of his estate would be abundant to furnish a comfortable support for you and your children, whatever misfortune may befall my life or my property, and I desired, if it had not been done, that it might be secured to you as your own. The widow and orphan of many a gallant man destined to fall before this struggle ends, though deserving, have not, I apprehend, such a prospect of a comfortable provision as

Page 31

you have. So, Love, the best consolation I can offer you is that there are others whose future is as dark as yours, and that yours is not so bad but that it might be worse. It grieves me, I am sure, as much as it does you, and we must both make up our minds, as the surest guaranty of happiness, to bear the present in patience and cheerfulness, and cherish a hope of another time, when we shall be together again, loving and happy as we used to be. If I survive this war, I have no fear of being unable to earn, by my own industry and energy, a comfortable support for my household. If fate determines that I must perish in the contest, then I trust that He whose supreme wisdom and goodness tempers the wind to the shorn lamb will shield from want the widow and orphans left dependent upon His providence. This is the first day of winter, and as yet we have had no snow. It has for some time been quite cold, and the water often frozen over. I have not as yet suffered much from exposure, and think I shall stand the winter well. With the assistance of four or five blankets, and bed made of some hay and leaves laid on split timber raised off the ground, I sleep quite warm. I hear nothing said of winter quarters, and so far there seems to be no determination to provide them. I think it would be as well to go into winter quarters, for the weather and the roads will soon be such as to make active operations utterly impracticable.

Will Lewis and Annie left here Wednesday, I think, and, I suppose, have reached home before this time. I sent by her my likeness and some candy for the children. When he returns send me your likeness -- that which was taken before we were married. I suppose you know where it is put away, for I don't remember.

And now, Love, as I have written you quite a long letter compared with what I generally write, I will bid you good-bye till my next. You have my heartfelt sympathy in your approaching illness, and my sincere hope of your speedy and safe recovery. Kiss dear little Matthew and Galla

Page 32

for me, and tell them to be good boys. And now, dearest, again good-bye.

Martinsburg, December 9, 1861.

I did not write my accustomed Sunday letter to you on yesterday. I was otherwise busy until 9.30 o'clock last night, when I reached here. Then I was so sleepy and tired, I could hardly stand upon my feet, having been awake all the night before, and hard at work most of it. Yesterday I spent on the bank of the Potomac, not as decent people generally spend the Sabbath, in peace and rest, but listening to the music of cannon and musket, and witnessing their work of destruction. There was much firing, but little damage on either side, as the river intervened, and the men of the enemy, as well as our own, were well sheltered from fire. Our loss, I learn, is one mortally wounded and two very seriously; one of the latter is the son of Shanklin McClure of our county, and a member of the Rockbridge Artillery. The purpose of the expedition was to destroy a dam across the Potomac which feeds the canal now used by the enemy in shipping coal. I was appointed to superintend and direct the execution of the work, with some men detailed to do it. We reached the ground about sunset on Saturday evening, when a few shots from our artillery drove off the force of the enemy stationed on the opposite side. I then took down my force and put it to work and continued until about eleven o'clock, when we were surprised by a fire from the enemy on the opposite side again, which made it impossible to proceed until they could be driven away. At daybreak Sunday morning our cannon opened fire upon them again, but they were so sheltered in the canal -- from which in the meantime they had drawn off the water -- that it was found impossible to dislodge them. As my workmen could not be protected against the enemy's fire, I found it necessary to abandon the enterprise. So you see, Love,

Page 33

entrusted with an important work, I have made a failure. If I had succeeded, the Yankees would have suffered much in Washington for want of coal. But they must get it as usual, for which they may thank their riflemen, who drove my party from the work of destruction upon which they were engaged.

I begin to think, Love, there is no amount of fatigue, exposure and starvation which I cannot stand. I got notice on Thursday about three o'clock that I was wanted at Jackson's headquarters; there I got my directions, and rode here in a hard trot of about six miles to the hour. The next afternoon I rode up and took a view of the work which I had in contemplation and returned here. On Saturday morning we left here with our forces to accomplish it. On Sunday at twelve o'clock I could not help but remark that I felt fresh, although I had not slept the night before, and had nothing to eat since Saturday morning at breakfast, with the exception of a small piece of bread and had been upon my feet, or my horse, nearly the whole time. I think this war will give me a stock of good health which will last a good while. And now, Love, whilst I have been in the perils of minié-balls, I expect, when I get to Winchester, to receive a letter from somebody saying that you have been in worse perils, and that we have an addition to our small stock of children. The only special message I have is that its name may be yours or mine, just as you like. Whilst, Love, I have just been expressing my gratification at my good health, and my capacity for fatigue and exposure, I cannot help feeling this war is an uncertain life, and there is no telling that you and I may never see much of each other again. I shall try and get a leave of absence to go home this winter; but I suppose it will not be possible until after Christmas, as I think Col. Echols has the promise of a leave at that time, and it would not be proper for us both to be away at the same time.

How much I wish that I was with you, that I could stay

Page 34

at home! But to turn my back upon our cause, to leave the fatigue, patriotism and risk of life which it requires to be borne by others, when duty and patriotism require that I should share it, I cannot do.

Unger's Store, December 10, 1861.

I made application yesterday for leave of absence, but was informed that I could not get it until Col. Echols returned, who has leave for twenty-five days and starts home this morning. It is to me a sad disappointment, but I must bear it as cheerfully as I can. You must do the same. You must make up your mind, too, Love, to stay at home. In the present state of our finances we must save all we can, and this, I feel sure, will be best done by your staying on the farm. I think, too, you will be as happy there as you could be elsewhere.

Winchester, December 12, 1861.

Last Monday night I returned to our camp here, where I had the pleasure of reading the letters of Mary and Helen informing me that your troubles were all over, that we had another little boy in the crib, and that his mamma, as Mary happily expressed it, "Was doing as well as could be expected." I would have written them to express my gratification at the good news from home, but I had orders to leave again upon another expedition to the Potomac which afforded no time for writing a letter. I reached Charlestown the next morning about daylight and spent most of the day on my horse. The morning started with the forces at one o'clock, passing by Shepherdstown to Dam No. 4 on the Potomac, where we captured eight Federal soldiers whom we found on this side of the river, in which we lost one man wounded -- I suppose fatally. We remained there until late in the evening, when we started for Martinsburg, where we arrived about nine

Page 35

o'clock, having made a march of about twenty-six miles. I left Martinsburg the next afternoon and returned to Winchester, where, having been some time engaged in a conference with Jackson, I found a bed and went to sleep, tired enough, I am sure. This morning I returned to camp. So, Love, I have given you together my operations for the last few days, which furnish the reason for my not writing sooner.

To-day I received Mary's letter of the 9th inst., from which I learn that you are improving, that the baby is doing well, which I am delighted to hear. I really sympathize with you, Love, in your lonely situation. You must be uncomfortable, lying all day and night in bed, though not suffering much with pain. In ten days more, I suppose, you will be able to sit up, and then in a week or so get about, attending to matters at home, as usual. I assure you that I reciprocate your wish for my return home, and heartily wish that I could consistently with my duty remain with you. If I can get a leave for only a few days, I will go before long to give a kiss and a greeting to the little fellow who has such strong claims upon my love and care. Active operations must soon cease, when there will be no reason why a short furlough should not be granted. The weather is already cold enough to make it uncomfortable in tents and such conveniences as we are able to provide. It would be intolerable if we were put upon the march with insufficient means which the men would have of making themselves comfortable.

I suppose by this time the hands have been making considerable progress in getting up the corn crop, and hope they may be able to finish it before Christmas. For the hired hands clothing must be furnished before Christmas. Can you get Annie or your ma to call upon Wm. White and get the goods and have them made up? Give my love to Helen and Mary and say to them I am much indebted to them for their letters and wish them to continue to write until you are able. And now, Love, good-bye again.

Page 36

Give my love to your father, ma and Annie. A kiss to Matthew, Galla and the baby, and for yourself, dearest, my hearty wish for your speedy recovery.

Winchester, December 15, 1861.

Life in camp is generally dull with me, and I feel especially dull to-day. I have sometimes had a job, such as road-making at Centreville or my late excursion to the Potomac, which kept me busy enough; but these only happen now and then, and but for them my life would be idle enough, I am sure. When here in camp it really seems that I have no way of employing myself. I sometimes think I would prefer a more active campaign, winter as it is. With my stock of bed-clothes I think I could sleep quite comfortably even at this season in a fence corner, but it would not be so comfortable to the soldiers, who are not so well provided with such means of a comfortable night's rest. If the weather continues open and the cold not too severe, I think it possible we may have some activity in our operations this winter. But of this no one can speak with any certainty but Jackson, and even he with but little, as his operations depend upon contingencies over which he has no control.

I sometimes look to the future with much despondency. I think most of our volunteers will quit the service when their year expires, and the news I get from Rockbridge gives me but little reason to hope that many more will volunteer to fill the places thus made vacant in our army. If they come at all, I fear it will be by compulsion. I fear there are more who are disposed to speculate off our present troubles, and turn them to pecuniary profit, than there are to sacrifice personal comfort and pecuniary interest and risk life itself for the promotion of our cause. My judgment dictates to me to pursue the path which I believe to be right, and to trust that the good deed may meet with its just reward. Nothing else could induce me

Page 37

to bear this sad separation from my darling wife and dear little children. This distresses me. I care nothing for the exposure and hardships of the service. But, Love, I should be more cheerful, and if sometimes oppressed with a feeling of sadness, should try to suppress it from you; for I should try and detract nothing from your happiness, which I fear I do in writing in so sad a strain.

And now, Love, good-bye. I shall be glad indeed to hear that you are out of your bed, and happier still to know, by a letter in your familiar hand, that you are nearly well and out of danger. When the winter sets in so cold that there can be no possible use for my services here, I shall try and get leave to spend a week with you at home. I don't think that snow can keep off much longer.

Winchester, December 22, 1861.

We left here, on an expedition to the Potomac, on last Monday morning at seven o'clock, and returned again this evening. We lost one man, Joshua Parks, killed by the enemy; and his body, I suppose, has by this time reached his friends in Lexington to whom it was sent for burial. Present my kind regard to Mrs. Parks, and say to her that I heartily sympathize in the sad bereavement which has fallen upon her. He was a brave and good man, universally esteemed and beloved by his comrades, and his loss is much deplored.

Whilst gone we slept without our tents four nights. I had plenty of blankets, and slept as sound as if I had been in quarters. I really could not have thought I could stand so much exposure with so little inconvenience. I think, if my health continues to improve under such outdoor life, I will soon be able to stand anything but ball and shell. I received Helen's letter, for which give her my thanks. I was delighted to hear that our baby is well and growing, and that you are improving rapidly. I am much gratified, too, at your pressing invitation to come

Page 38

home. I believe, Love, you must want to see me. It has been my purpose to ask for a furlough as soon as winter had fairly set in so as to render active operations impracticable. To-day was very cold, -- so cold that we all had to get off our horses and make the greater part of the march on foot. To-night we have sleet and snow, which, I think, will pass for winter, especially as it now wants only three days of Christmas. So, Love, I shall ask for a furlough some time this week, and, if I can get it, will be off for home. And if you hear a loud rap at the door some night before long, you need not think robbers are breaking in, but that your own dear husband is coming home to see wife and little ones, dearer to him than everything else on earth. But, Love, you must not calculate with too much certainty on seeing me. If I can get the leave I will, but that is not a certainty.

I hope you all may have a happy Christmas, and wish I had the means of sending some nuts and candy for Matthew and Galla. Many who spent last Christmas with wife and children at home will be missing this time -- perhaps to join the happy group in merry Christmas never again. But let us be hopeful -- at least share the effort to merit fulfilment and fruition of the hopes we cherish so fondly. Now, dearest, good-bye till I see you again, or write. A kiss to the children as my Christmas gift.

Winchester, December 26, 1861.

I applied to-day for a furlough, but was much disappointed to find that an order has been made that none shall be granted. I was promising myself much happiness in spending a few days with you at New Year's, and am much grieved that it has to be deferred -- I hope, however, not very long. I will come as soon as I can get permission. Fair weather cannot last much longer, and winter must soon set in, which will stop active operations, and then I suppose I can get leave to go home for a while. I

Page 39

will make this note short so as to try and get it in to-day's mail. Your box just came to hand as I left the camp this morning, for which accept many thanks. Good-bye, dearest.

Winchester, December 29, 1861.

The weather opened this morning cloudy and showing signs of snow, but, much to my disappointment, the clouds have passed off leaving a clear sky and pleasant day. It is not often I wish for bad weather, but when it opens a way for me of getting home for a little while I bid it a hearty welcome. It troubled me less when there was no prospect of getting a leave of absence and no use of asking it; but as I have been so anxiously indulging the hope of late, it troubles me much to have it deferred. If the bright sunshine of to-day is destined to last, you need not expect me, for Jackson is not disposed to lie idle when there is an opportunity to win laurels for himself and render service to our cause. The arrival of our forces from the West under Loring has given him a very fine army, which I think he is disposed to turn to a very profitable use as soon as an occasion may offer itself. I have much reason to be gratified at the proofs of his good opinion and confidence which I am continually receiving from him. I can rely upon his influence and efforts for my promotion, but my ambition does not run in that direction. The sympathies of my heart and my aspirations for the future are all absorbed in the wife and little ones left at home, and my highest ambition is to spend my life there in peace and quiet. The hope of winning military titles and distinction could not tempt me to leave home, if I were left to consult my wishes and feelings alone. But the sense of public duty which prompts us, and the strong public sentiment which forces us, to leave our homes and families for the public service, now with equal force compels us to remain. If we left the army now, it would be at the sacrifice

Page 40