History of

Corporal

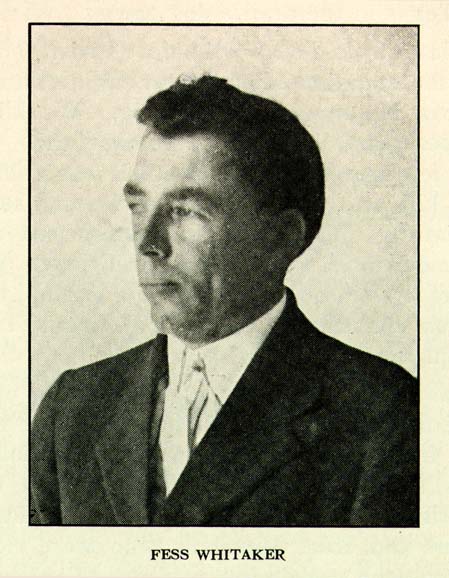

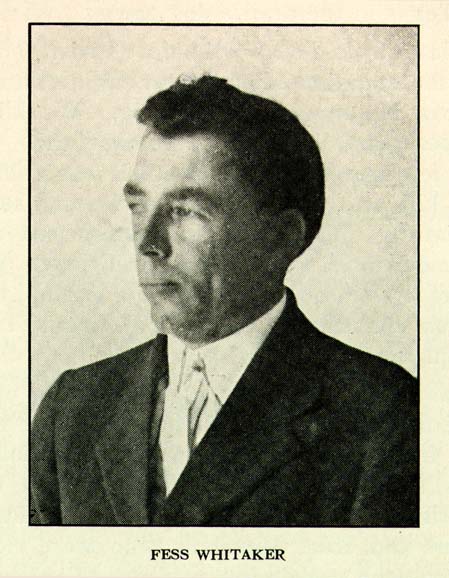

Fess Whitaker

COPYRIGHT 1918

FESS WHITAKERTHE STANDARD PRINTING CO.

INCORPORATED

LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY

Page 5

AUTHOR'S PREFACE

AMONG the people of Letcher County no other

man has so remarkable history as Fess Whitaker;

none other is so well worthy of being carefully

studied by all who find pleasure in the past history and

particularly by Letcher's own people. In the winning of

friends he stands first; in the upbuilding of the county

his influence has been strongly exerted; as a soldier on

the battlefield he stands firm. While the moonshiners

and ku-klux were provoking the country in my early

boyhood as though led by an inscrutable hand were

finding their way over the mountains and preparing to

establish themselves as the outguard of civilization that

they might become the possessors of all the sons of

Letcher County, the good mountain mothers, almost

unaided, not only stood like a wall of fire to forbid such

conduct of the men, but made good their footing, which

soon afterward made their loving Christian homes a

pleasure.

The strong characteristics of the men and women

who, with unexampled courage, endurance and patriotic

devotion achieved so much with so little means and

in the face of obstacles so great, could but impress

themselves upon the people of Letcher County. From

Page 6the first mothers they have escaped that sign of Athenian

decadence, the restless desire to be ever hearing and

telling some new thing to show what good people

Letcher County has.

This book claims to be but an epitome of the History

of Fess Whitaker; but it will be found to contain a

general account, to which interest he has taken by an

uneducated man, special and particular incidents, etc.

The adult or educated mind will read far more between

the lines than is found in the book. The author trusts that

he has imparted to the short stories something of that

spirit which should be impressed upon the people whose

minds and character are still in the formative state - an

admiration of their own country and a pride in its past,

the surest guarantees that in the future her fair fame will

be enhanced, her honor maintained and her progress in all

right lines be steadily and nobly promoted.

Page 7

HISTORY OF CORPORAL

FESS WHITAKER

FESS WHITAKER was born

June 17, 1880, in

Knott County, Kentucky. Knott County is located in the

mountains of Kentucky between the Big Sandy River

and the north fork of the Kentucky River. There are no

railroads in Knott County but there is lots of fine coal

(what is known as the Amburgey seam), and lots of fine

timber. Hindman is the county seat. Knott County has

fine churches and schools and good roads, and, no

doubt, the best farming county in the mountains.

When I was only six years old my father swapped

farms with Tood Stamper and put the Whitakers together

in Letcher County and the Stampers together in Knott

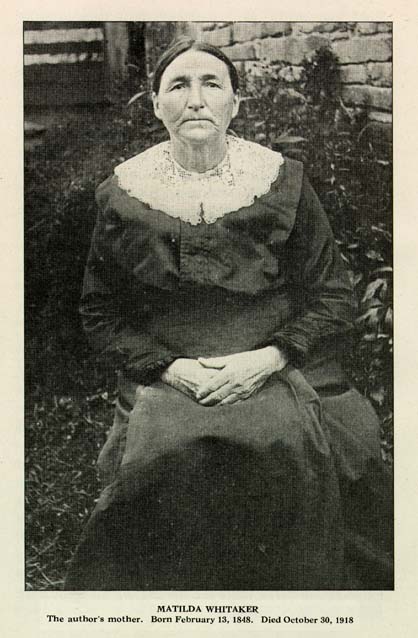

County. My mother was old Kelly Hogg's daughter, and

in time of slavery my Grandfather Hogg swapped a

foolish negro to Mr. Mullins of Knott County, for a good

farm worth $10,000 today, known as the Black Sam

Francis farm now. Mr. Mullins thought lots of his little

negro and called him his Shade, meaning that he could

rest and the negro could work. But when the greatest man

that ever has been elected President of the United States

of America, Abraham Lincoln said slavery was not right and

Page 8released the shackles from four million

slaves, Mr.

Mullins lost his farm and his little negro "Sam Hogg

Mullins," too.

When I was six years old my parents went back to

Rockhouse, a tributary to the north fork of the Kentucky

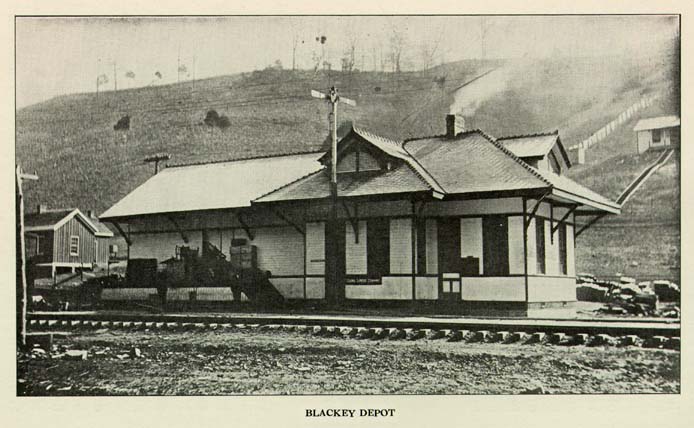

River, now one mile from the little town of Blackey, or the old

Indian Bottom Church. The same year that my parents moved

to Rockhouse my father, who was the late I. D. Whitaker, Jr.,

died. He was the son of S. A. Whitaker, known so well in

Kentucky and Missouri. After the death of my father

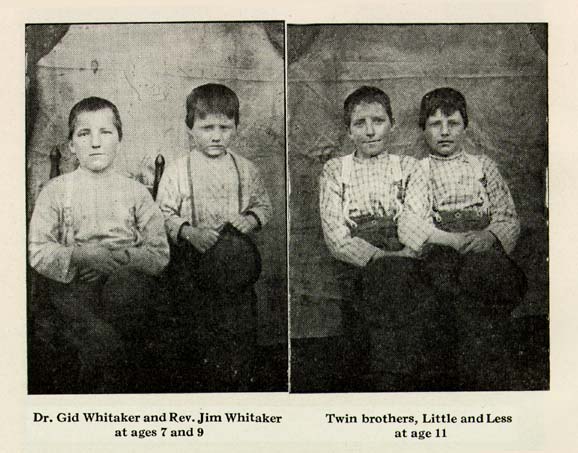

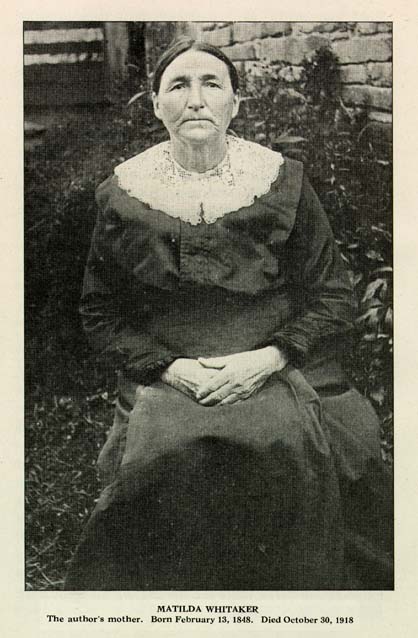

Page 9my mother was left with eight poor little orphan children to

raise, six boys and two girls. The boys' names are very funny;

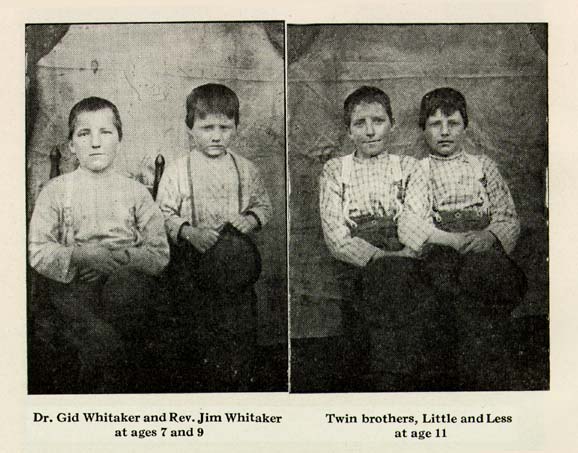

they are, according to name and age: Fred and Fess, Little and

Less, Gid and Jim, and all the rest. And all the rest were the two

girls, Julia and Susan.

My mother was left with a very good farm of about 125 acres,

and the Rockhouse Creek ran right through the center of it.

During those days every spring we had what was known as big

tides. The late Bill Wright was the greatest logger and splash-dam

man in the mountains of Kentucky. The next year after my

father died Mr. Wright had five big splash-dams in the head of

Rockhouse and Mill Creek and had between ten thousand and

fifteen thousand big poplar saw logs in the dams, and when he

turned those five dams loose there was no land or fence left

below. So that same spring he cleaned our farm on both sides

of Rockhouse and in about ten days here he came with twenty-

eight big, strong mountain men, bedding all the logs that lodged.

I will never forget what happened. They were all eatin' dinner at

mother's; and one man, by the name of Sol Potter, was eatin'

big onion blades and he got choked and got his breath all that

evenin' through the onion blade, but by good luck Mr. Potter is

a real rich man in coal land below Hemphill leased to Parson

Brothers and Big Jim Montgomery, and in that bunch of log-

bedders was Henry Potter, of Kona, another rich man of the

mountains, and a brother to Sol Potter and also a brother-in-law

of ex-Jailer Hall. Mr. Wright, the owner of the logs and dams,

was murdered by Noah Reynolds just above his home, now

Seco. Reynolds

Page 10was sent to the penitentiary for life and served seven years

and was paroled by Governor Beckham. Reynold's is now a

Baptist preacher and lives in Knott County. The Southeast Coal

Company is now operating on Mr. Wright's land at Seco, Ky.

After the big tide and all the rails gone and big saw-logs laying

out in the bottoms in the corn in April, we had no money, so us

boys finished making the crop and minded the stock out of our

corn with the dogs until fall. There was no such a thing those

days as wire fences, and in the fall we went to the mountains and

cut and hauled in rail timber and made rails back out of big white

oak trees or black oaks worth $25 per tree now. We would cut

and saw the cuts to make the rails out of about eight feet, would

split and burst them open with two good wood gluts and iron

wedges and a good old seasoned hickory mall, weighing about

thirty pounds. After we got our corn and fodder laid up for

winter the people would go many miles to an old horse mill to

get cornmeal ground. Everyone would take their turn grinding.

They would put their horse into the mill, put their corn in the

hopper and then get a switch and start the old horse around.

And in about one hour he would have about one bushel of good

meal. There were only three mills within fifty miles square. Old

Levi Eldridge had one on Rockhouse, and old Pud Breeding

had one on Breeding's Creek, and old Fighting George Ison

one on Line Fork.

When I was eight years old my mother started me to an

old water mill with two bushels of corn to get meal and put

me on an old mule named "John," put a spur on my right heel

to make the old mule go if

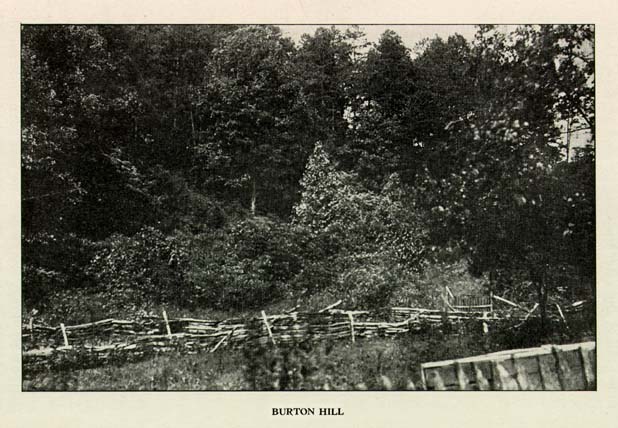

Page 11he took the studs. So I was just going across Burton Hill and,

like a boy, I wanted my mule to trot, so I applied my spur and

he started and I began to bounce around on the saddle, and the

tighter I clinched my legs the faster the old mule got, so he ran

through big ivy and laurel patch and threw me off. By luck I only got

skinned up a little bit, so I finally caught old "John" and took off

my spur and got back on the old mule. It was a very cool, frosty

morning, so I went up about two miles to where the late 'Esquire

Whitaker lived and I got down to warm. I hitched my old mule to

the gate and fixed my corn on better and went into the house.

After I got warm I went back out and got on my old mule and

went on to the mill at Ben Back's. I got down to take my corn

off and there was no corn, so I took back down the road huntin'

for my sack of corn. I went back to where I warmed and there I

found my sack torn all to pieces. While I was warming the old

cows pulled it off of my saddle and the hogs drug it over a cliff of

rocks and eat it all up. So I went home and mother sure did fix

my back, and then we shelled another sack of corn and mother

took it, because it was noon and no bread and a houseful of

children and no bread to eat.

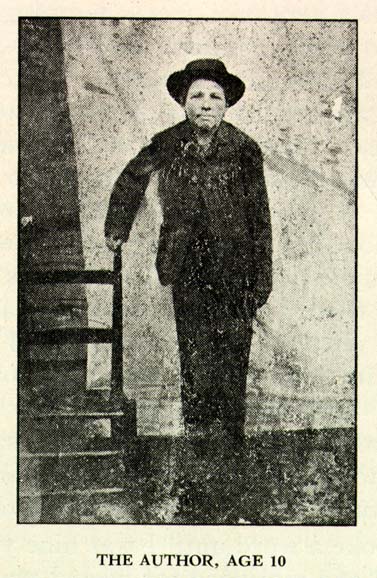

I never spoke a word until I was nine years old. I only

clucked and motioned for what I wanted. Lots of people

thought I was an idiot because I could not talk. I may have

looked like one, for I was a little old country boy that never cut

my hair in those days only about twice a year, and I wore a big

checked cotton shirt and old jeans pants made by my mother

and old yarn socks, and 70-cent stogie shoes with brass toes.

This was my winter suit and my summer suit was only a big

yellow factory shirt and no hat or shoes.

Page 12

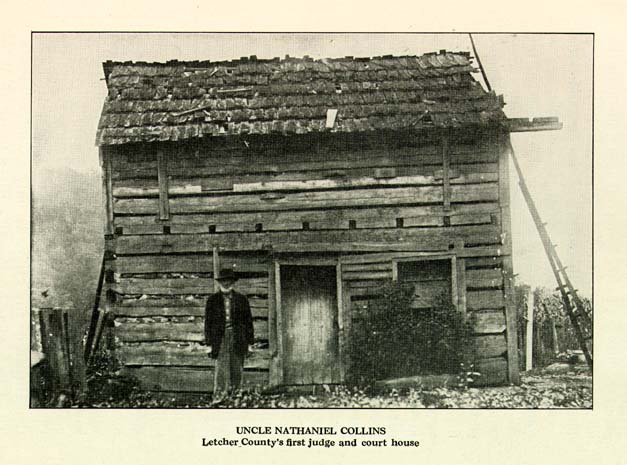

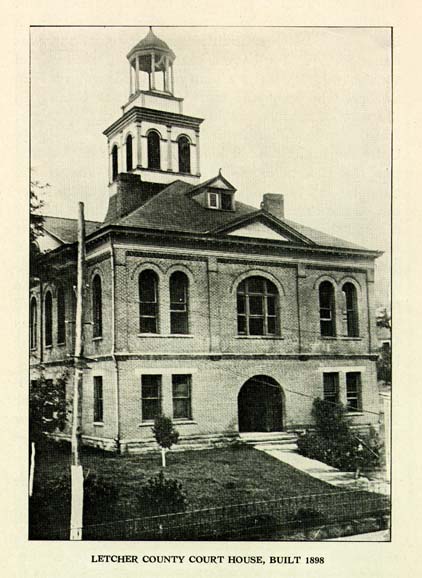

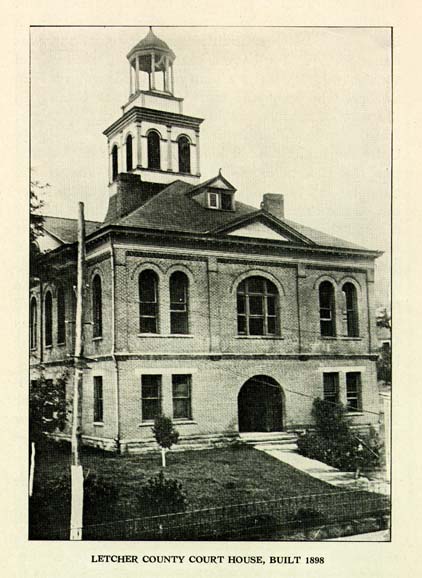

At the age of ten I was taken by my mother and uncle, Gid

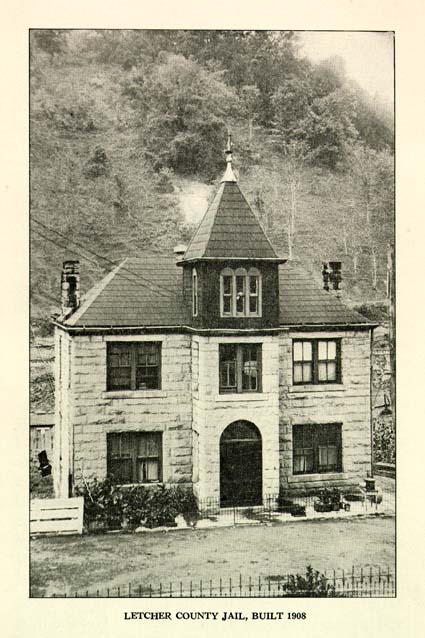

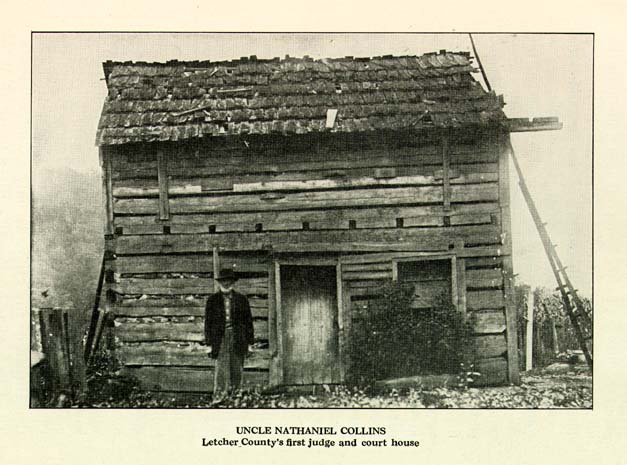

Hogg, to Whitesburg, Ky., the county seat of Letcher County, a

distance of about eighteen miles. We rode an old mare named

"Kate," without any saddle, and when I was taken off I could

not walk I was so stiff, and that made everybody think I was an

idiot sure enough. So when Judge H. C. Lilley opened court on

Monday, February 12, they taken me before the judge. The

judge ordered old Black Shade Combs, then the sheriff, to

summons twelve jurors and two doctors. One doctor thought I

had been born an idiot, and Dr. S. S. Swaingo, of Jackson,

held out that I was all right of mind, and so the case was put

off until 10 a. m. Tuesday. Then Dr. Swaingo got old Dr.

McCray and gave me a thorough examination. The doctors

found by examining my neck,

Page 13where the small tits in one's neck are, that the tit in my neck had

grown together. After the doctors cut the tit loose in my neck I

began to talk and to have a good joke. The doctors took me to

a one-horse barber shop and had my hair cut and fixed me up

and presented me on Tuesday morning to Judge Lilley, and he

was surprised beyond reason that I was Fess. So that was

Fess's first miracle. Later on they have all been worked out to

the present.

When my mother took me back home everybody was

surprised and people came miles and miles to see the boy that

was so much talked about and to see the boy that had been

made to speak after ten years of worthless tongue.

I was put in school at the age of ten years and was known

as the funny schoolboy. The children would all laugh at me

because I could not talk plain, but it did not take me very long

to learn how to stand ahead in my classes. I was very fast to

learn in all the books they had those days except arithmetic.

The first school I ever went to was in an old log house dobbed

with mud, with an old-fashioned chimney made out of mud

and sticks of wood. The late W. T. Haney, who was murdered

on the head of Little Carr, of Knott County, for $30.00, was

the teacher. He was known one day as being the best-

read man and no doubt the best educated man in Eastern

Kentucky those days. He was the father of John Haney,

of Chicago, the expert railroad man, and the stepfather

of George M. Hogg, one of the leading men in Eastern

Kentucky. Mr. Haney, after hearing all of the children's

lessons in the afternoon, would lay down in an old country

wash trough for a nap of sleep. The

Page 14

trough was made out of a fine large yellow poplar, eight feet

long, and hauled out of the mountains with a yoke of steers. The

log was hewed square on one side with a sixteen-inch broadax,

then eight inches left at each end and the remainder was hulled

out to a big trough, then two holes were bored in the bottom of

each end of the trough and four wooden legs, made by hand,

were driven into the trough and set up. In the inside of the trough

at one end at the bottom was a hole bored and a pin made to fit

so that it could let the water out. The water was "hit"and put in

the tub and when the "wimen" began to wash they would have

what was known as battling sticks and they would apply the

water and soap on the clothes and lay them on the eight-inch

end of the trough and begin to battle. The old troughs have about

all played out of fashion, as the galvanized tubs were brought in

and have taken the day; still there is many a one used up to the

present day. The soap they used those days was the best of

soap. The men folks would cut and haul in out of the mountains

so many white oak and hickory trees. They would cut and saw

them up and pile them up in a big pile and burn them to get the

ashes. After the ashes were cooled off they took them and

poured them into a gum called those days that was sitting on

some boards that the gum was made to lean on. After staying

nine days, on the old moon, water was poured in the gum on the

ashes and the red lye began to drop and run out of the bottom

into another trough, made like the washin' trough but smaller.

After the lye leaked out good and got all the strength out of the

ashes, the lye was put in an old country fashion pot and the hogs'

guts that had been washed and dried and strung on a pole in the

corner of the old

Page 15

chimney was taken down and put in the pot with the lye. The lye

was so strong it soon ate up the hogs' guts and boiled to a jelly-

like substance and taken off and put in old big round gourd

raised on the farm. The gum that held the ashes was a hollow

tree cut down and burnt out inside and sawed into about

four-foot lengths for gums.

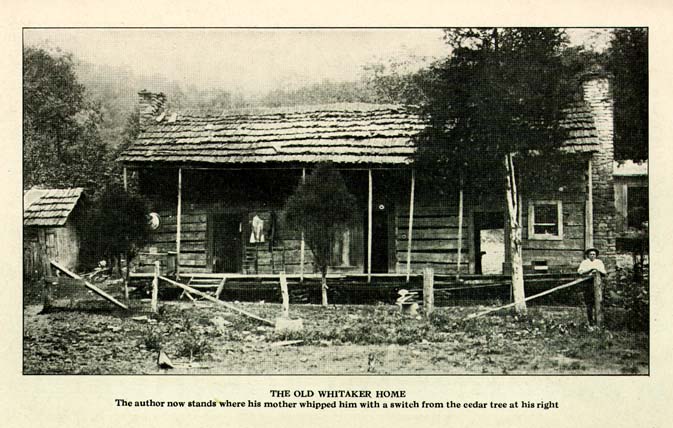

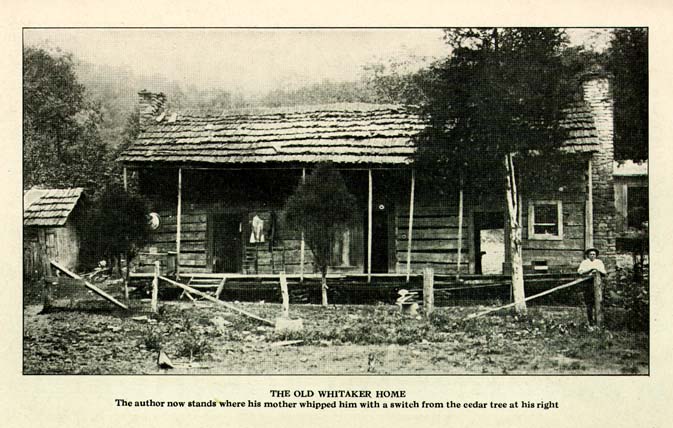

The second school that I went to was taught by little Sammie

Banks, of Big Cowen. Sammie boarded with my mother, and

after the five months' term of school was out Preacher Jim Caudill

made up a subscription school at the mouth of Rockhouse at

$1.00 each and mother signed for five, and she had no money,

but had a good nerve. The first week I went mother took me up

in her lap and tried me in arithmetic where the teacher had me,

and I knew nothing about it. The teacher was pushing me too

fast. Mother told me that she would try me one more week and if

I could not do anything in the arithmetic by the next Friday that

she would give me a good whipping. So the next Friday came

and I had not learned anything, so I played off sick about 11

o'clock that morning at school and went out of the schoolhouse

and began to play off crazy, and my sister Julia, now Mrs. J. D.

Stamper, of Big Springs, Tex., ran after mother. There being no

medical doctor within forty miles, they brought a charm doctor,

Andy C--, rubbed me and charged mother five dollars for it

and claimed I had been poisoned very bad, so by Monday I was

ready for school. And mother told me what would happen Friday

if I could not do anything with my arithmetic. So I tried, and

Friday evening mother tried me and I was in long division, but I

could not do anything. She got me up in her lap and tried her

Page 16

best to show me, but all in vain. So she put me down and laid

the book upon the table and took me by the hand and led me

to a large cedar tree and broke her a good switch and began

whipping me. She whipped me until she gave out, and sat down

on a large rockpile to rest and stood me up and talked to me

while she was resting. After she got through resting she raised

and gave me the same dose again; then she took me back

in the house and got me up in her lap and began to show me

about my lesson, and it jumped in my head like a falling star,

and from that time until the present date I challenge the State

of Kentucky in the arithmetic. That was my second miracle.

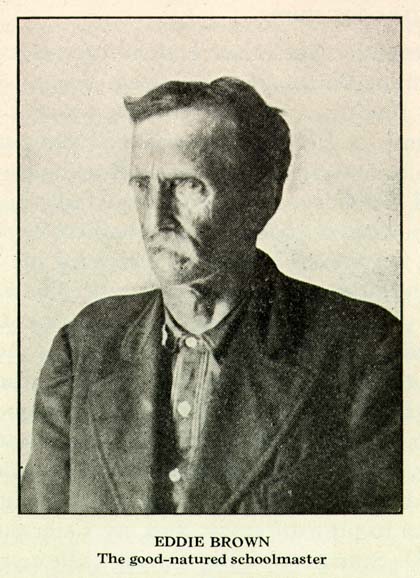

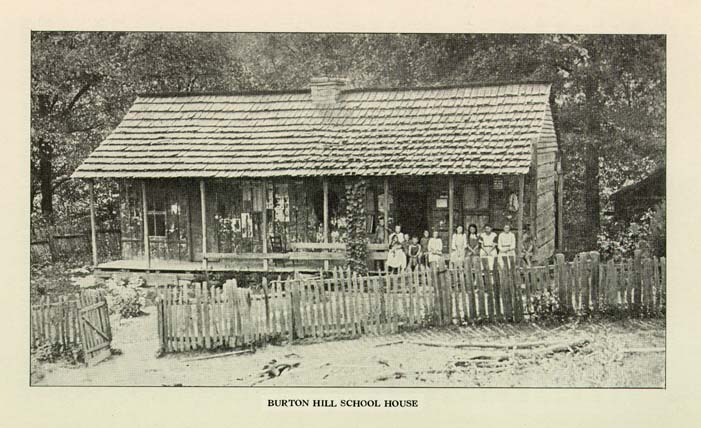

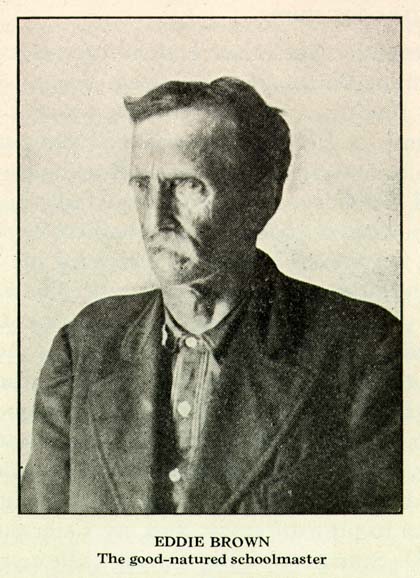

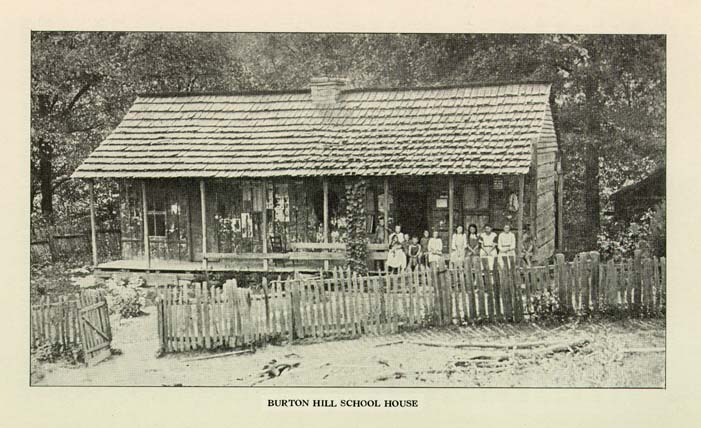

The third school I went to was taught by Eddie Brown, on

Burton Hill, in a new log house, with no

Page 17

chimney and no floor in the house and a big fire in the middle of

the house. I always had the rest of the children beat by this time.

I was twelve years old and past and had begun to get to be a

pretty mean boy on account-of so many people picking at me.

Eddie Brown, the teacher, told us children if we were not good

children that the "Old Bugger Man" would come and get us. So

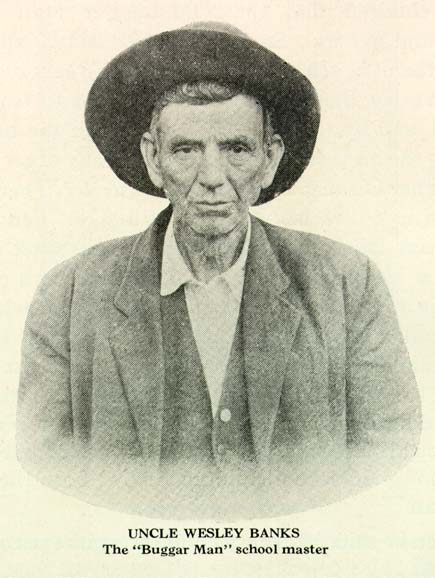

the"Bugger Man" sure did come the next school. I was thirteen

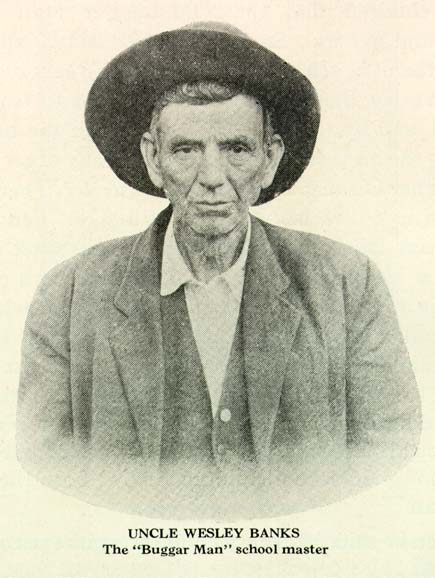

years old then, and Wesley Banks had been employed to teach

the school, and by this time the school had the name of having

the meanest lot of boys in it of any other school in Letcher County.

I was called the leader. There were four of us called bad - Mason

Whitaker, Ben McIntar, Print Ison and myself. Mr. Banks took

charge of the school on July 5, and all the children's parents

came in to see the new teacher. So the teacher got up to talk and

open his school. He was a very homely mountain man, and the

first thing he said was:"This school has an awfully bad name

and I understand that Mr. Eddie Brown teached this school

last year and told you all that the "Bugger Man" would come

if you were not good school children. Now, I am the 'Bugger

Man.'"

When he said that every child threw its eyes on him.

"Next one I call their name please come around to where I

now stand," said the teacher.

The first name called was Fess, then Print, Mase and Ben.

So we all went around to where the teacher was and he said:

"Boys, I have bin told that you four boys have bin very bad

boys in school, so I am going to turn a new leaf."

Page 18

My heart was in my neck, for I knew that Mr. Banks had

already brought in twelve long green oak switches before

opening school.

"Fess," said he, "it's reported to me that you are the

meanest," and he took me by the hand and sure did like to

beat me to death and when he got through with me he told

me to take my seat. Then he took Print next and gave him

the same, then Mase, and while he was whipping Mase a

large splinter flew off the switch and across a twenty-foot

house and stuck in under the shoulder blade of the back of

Less, a brother of Fess. Then he had to take a pair of old

home-made tooth pullers that had been made in a

Page 19

blacksmith shop by big Jim Back, of Caudill's Branch, and

pull out the splinter. After all that he gave Ben the same dose

as he did us. He then said that the school had opened, and

gave us our lessons. He only had to apply his new rule once.

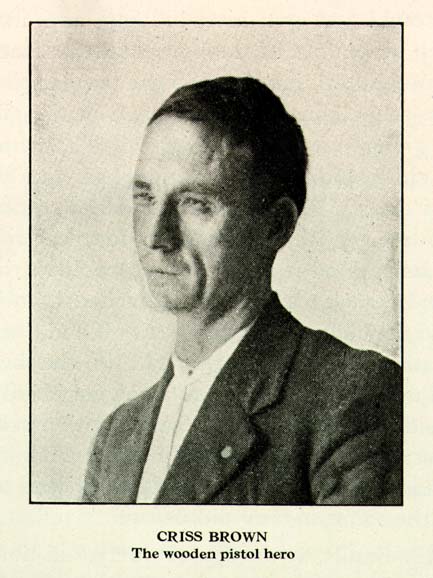

After the free school was out the same old Baptist preacher,

Jim Caudill, got up a subscription school again that winter.

My mother had rented part of her farm to Joe Brown, of

Cumberland River, and he had eight boys, and one, by the

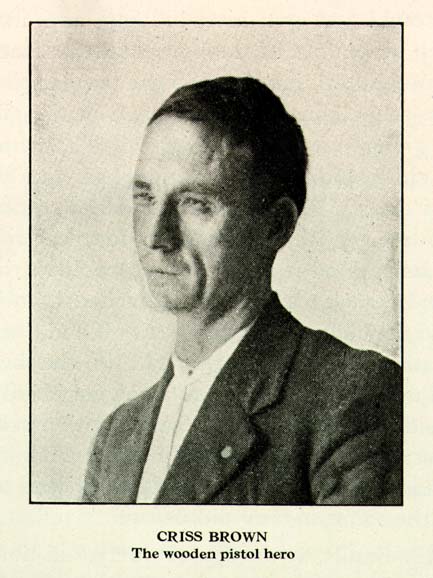

name of Criss, was very bad. Along during the second week

Criss done something and the teacher went to whip him and

he bucked on the teacher, so the good old teacher, about sixty

years old, put the whipping off until he could see the father of

Criss. So that

Page 20

night Criss made him a wooden pistol and wired a big forty-four

cartridge hull on the end of it and made a fuse hole in the end

of it and filled it with black powder and drove a stick in on the

powder and took it with him to school. The teacher had seen the

boy's father and told him about the trouble and the father said

to be sure and whip him, so he called for Criss to come around

and get his whipping, and instead of going up he ran out of

the house and the teacher followed him, but all in vain. So the

teacher came back into the schoolhouse and sat down in the

chair and started giving out a spelling lesson. The schoolhouse

was on old-fashioned log house dobbed with mud, and some of

the mud had fallen out of the cracks of the schoolhouse. With

his big forty-four cartridge hull loaded he sighted it right at the

teacher's old bald head and struck a match and touched it to

the fuse hole and the old wooden gun went off and the wooden

bullet struck the old man right in the head. He jumped up and

dismissed the school, very badly scared and bleeding, and never

did teach another school. So the next year they got the "Bugger

Man" teacher again and everybody came out to see him open

his school the same as they did before.

Wesley Banks, at the age of thirty, did not know a letter in

the book and began going to school, and at the age of thirty-three

received a third class certificate and began teaching and

now has taught forty-six schools in Letcher County thirty-seven

years in succession without missing, and very near whipped

every boy in Letcher County. He was at one time called the best

teacher in Letcher County.

Page 21

At the age of fourteen I became head of the family, as my

older brother, Fred, became grown at the age of sixteen and,

there being no father to make him mind, he ran around the

country one year, doing no good. At the age of eighteen R. B.

Bentley, with both legs off, then County Court Clerk of Letcher

County, took him into his home and finished his education for

him. He is now a well-to-do-farmer and stockman of

Richmond, Ky.

After I became head of the family mother went off one Sunday

and myself and the four younger boys run a year-old colt in the

stable and we had just killed some hogs, so we got the hogs'

bladders off of the hogs' guts and blew them up and filled them

up with white beans and they sure would rattle. So I tied three

bladders to the colt's tail and opened the door and turned the

colt out. There was a large apple orchard all around the barn, it

being about four acres square. So the colt started, its tail in the

air, then under its belly, then between its legs, scared to death,

and just simply burning the wind. " 'Pon my honor," when it got to

the other end of the orchard it turned to come back and its tail hit

an apple tree, causing one of the bladders to burst. Talk about

jumping! The colt went up in the air about ten feet, and when it

hit the ground it made an awful funny noise and started for the

barn. Us boys got out of the way and when it got within ten feet

of the barn it made a long jump for the door. and just as it went

to go through the door it struck its hip against the side of the

door and knocked one of its hips out of place.

Page 22

Just as soon as mother came home the other boys

told on me, so I sure did get some more of that oak tea

just like Wesley Banks gave me, and my mother sure

was mad.

My mother was a Hogg before her marriage, and sure

could whip and whip with a good constitution. I am now

fifteen years old and in school and the best attendant in

Letcher County. There were about twenty young men

and thirty young girls in my class. The school was

mostly composed of Bankes, Isons, Fraziers, Caudills,

Backs, Hoggs and Whitakers. Burton Hill is located

about two and one-half miles from the mouth of

Rockhouse. It is a beautiful place and about twenty acres

square and all level, covered with large black pines,

cedars, ivy and laurel and lots of mountain tea grows

there. It lies in the bend of Rockhouse Creek, and the

creek runs very near all around it. It is now owned by

Less, brother of Fess, of Amarillo, Tex. That is where

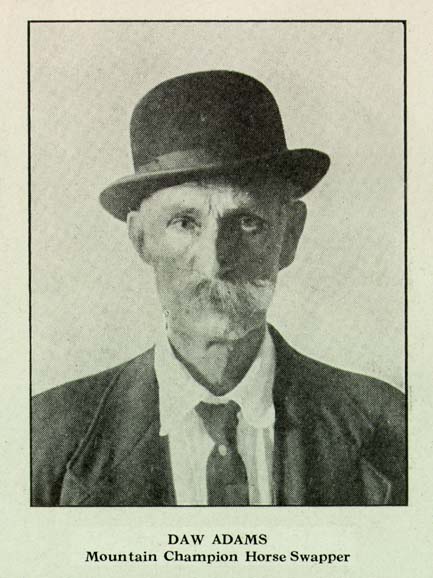

the late Wesley Collins and Daw Adams built the first

church in the lower end of the county. And the first

preacher I ever saw was then.

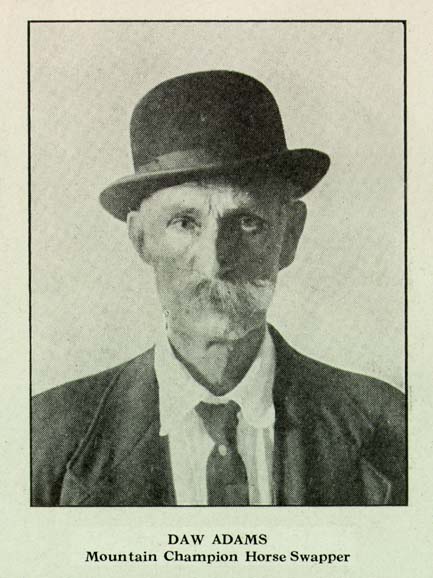

Mother had washed us all up and put a clean shirt on us

boys and taken us up to church. Mr. Collins opened up

the church like the old Regular Baptists do nowadays.

After church was opened Mr. Adams was the first

preacher. He was then about forty years old and had been

married seven times and stood about six feet and four

inches on the ground, and holds the world's champion

horse-swapping medal. He had two big long cowboy

spurs, one on each foot. and his boots had the pictures of

the moon and stars on top of them. So Mr. Adams

opened the song book and

Page 23

Page 24

gave out an old-fashioned song and asked everybody to help

sing, and after the song he took his text. Don't remember just

what it was, but according to his faith Adams was carried off in

a trance and he was squatting and yelling and said "Brothers and

sistern, if this doctrine is from the Lord it's all right, and if it's

from Daw A. it's no good," and about that time he drove those two

big cowboy spurs into his thighs and he gave a great yell and

everybody had to laugh. So Mr. Adams never got up to preach

any more from that day until this, but he is a good old Baptist

Christian and professed a hope a few years ago and was

baptized at Mayking, Ky., where he was born and reared up.

Mr. Adams belongs to one of the largest generations

Page 25

in the country and is well liked and thought of by everybody.

His great-grandfather came over here the same time that Daniel

Boone did, and Boone settled at Kona and Adams at Mayking.

Those days times were rough in Letcher County; a moonshine

still was in very near every hollow and a blind tiger everywhere.

And Adams was a big-hearted fellow and fell on the church that

day to get to skin some good old man out of his horse or mule.

Mr. Collins, the other preacher, died some years ago in the

asylum at Lexington. He died in good faith and died a regular

Baptist, and belonged to a large generation of people and good

parents. One of his sisters sailed from New York on February

23, 1918, as head of the Salvation Army in France. You will

always find the Collins' trying to live in the faith and always doing

something good for their neighbors. Those were the first

preachers I had ever seen. I had never been taught anything

about churches or Sunday-schools, but since that day I have

seen all kinds of churches.

Just before the end of school the late Elijah Banks, who

lived on the head of Montgomery Creek on the north fork of the

Kentucky River that empties into the river in Perry County, in

the great coal fields of Eastern Kentucky, had four grown boys

in school, so they set in begging my mother to let me go home

with them on Friday evening, and at last my mother consented

to let me go. So after school was out Friday evening we all

started for Montgomery Creek, about eight miles through the

mountains.

We went down to the mouth of Caudill Branch at the

three big cliffs of rock, up Caudill Branch to the

Page 26

mouth of Whitaker Branch, and up Whitaker Branch and across

a big mountain well covered with white oak, chestnut oak, red

oak and chestnuts and three big coal veins under same; No. 3

veins four feet thick, No. 4 veins six feet thick, and No. 7 veins

seven feet and eight inches thick. Over in head of right-hand fork

of Elk Creek down we go, and down that fork to the mouth at

Uncle Dave Back's and then up a steep hill to the top, and there

we found a nice level country, 2,097 feet above sea level, and

one of my father's sisters lived there, Aunt Peggie Dixon. All of

them came out to see me, and after we left there we went around

through the flat woods, and as we went through the flat woods

the Banks boys told me that Thomas Gent, a big, rough nineteen-

year-old boy, had knocked out Press Hensley's black cow's eye

and they wanted me to whip him and they would give me twenty-

five cents for it. I told them I would do it. I had the twenty-five

cents on my mind, and it was my first piece of money to get,

should I win. I made up my mind to win. So now we were

around in the flat woods to where Press Hensley lived. The

Banks boys. called out Hensley and asked about his old black

cow getting her eye knocked out. He went on and told all about

it, and it sure did go in on my brain, so we had to go down a little

steep place through a big chestnut orchard to where the G. boy

lived. I went in and asked where the boys were and the old folks

said that they were around in the Rich Gap field. That pleased the

Banks boys, so just as we got in sight of the field I met Thomas,

a very big man, weighing about 140 or 150 pounds. I asked him

about knocking the cow's eye out, and, like a mountain man, he

said he did. Just as he said it I struck him in the stomach with my

left

Page 27

hand and on the chin with my right hand and he struck the

ground, and onto him I went and into his face. I skinned it in a

thousand places and I got up and asked for my price of twenty-

five cents, which was gladly paid. We all went on rejoicing over

the hill to where the boys' father lived.

I never had a better time in my life than I did on that trip, and

I also won a title in the fighting ring. The boys' father had thirty-

six big, fat bee gums and he got an old rag and tied it on a stick

and set it on fire that made a smoke and then took it and robbed

a bee gum and taken out a dishpanfull of fine linn honey. Aunt

Bettie Ann, now dead, had plenty of good homemade sugar all

molded out in teacups and she gave me plenty of it. The boys'

father told me all kinds of big war tales and country tales. He

sure was a great hand to tell tales, and good company.

We all went wild-hog hunting on Saturday and caught two big

wild hogs, then that evening us boys all went down Montgomery

Creek about three miles to Wash Combs' to a big country

dance. There were about twenty girls and boys and a good

banjo and fiddle. They sure could dance some of that old

country dancing. Along about 11 o'clock they all got to courtin'.

They laid across the beds and hugged each other those days.

That was the style. After all the beds were full and no more

room on the beds to court they would sit in each others' laps

and hug each other. I went to sleep and they put me on a pallet

on the floor in the corner of the house. At 4 o'clock in the

morning the boys woke me up and we all went back up to the

boys' father's.

Page 28

Page 29

So Sunday evening we all went back over the mountain to

our school. That was one great trip that will never be forgotten,

and my first trip away from home. I learned on that trip to

have a nerve and to have faith in myself.

After the free school was out my mother took me up to old

Shade Combs', sixteen miles up on Rockhouse, to a winter

school. Shade Combs was a first cousin to my mother, and he

remembered the time when he was the sheriff and they had

brought me to Whitesburg to try and get me on the county and

we had some good jokes about it. Mother stayed all night and

next morning she put me in school. Professor C. C. Crawford

was the teacher, and I made myself at home and liked school

fine and done well in school.

I am now sixteen years old and out of school, grubbing and

fencing and clearing land, trying to keep my brothers in school,

which I did by hard work. I was known those days as the father

of my brothers. During that year my sister, Julia Stamper, now

of Big Springs, Tex., was plowing an old yoke of oxen named

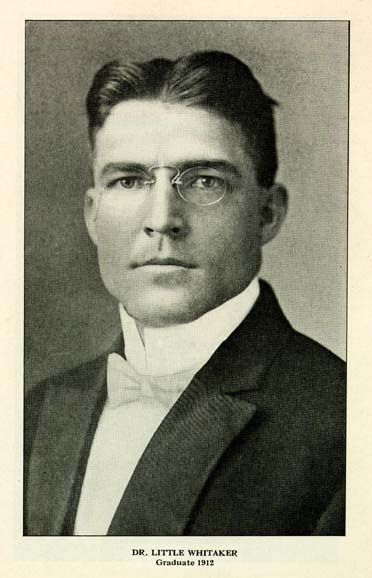

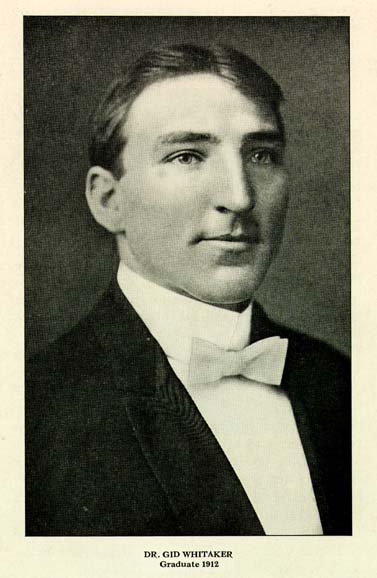

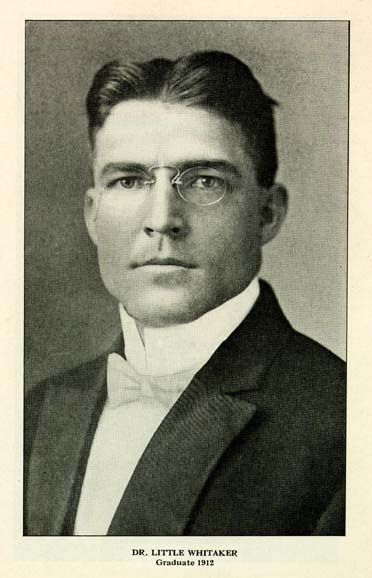

Dick and Mon, and Little, now Dr. Whitaker, of Blackey, Ky.,

was driving the old oxen, and I hid behind a big rockpile,

wrapped up in a big white sheet, and when they came around

the rockpile I jumped at the old oxen and it simply scared them

to death. Their tails went in the air and they went across that

field just a-flying, and old Dick got the bottom plow stuck in his

side and died from the effects of it. Julia and Little ran to the

house and told mother what had happened, not realizing it was

me that had scared the poor old steers. So I owned it up, and I

do believe

Page 30

that was the hardest whipping that my mother ever gave me. It

was funny, but I guess I sure did need it.

The same year during mulberry time on Saturday we all came

in about 11 o'clock in the morning for dinner. We had a large

mulberry tree down next to the gate and it was awfully full and

just getting ripe. So we all made a dive for the tree, five of us

boys. We all got right in the top of it and began to eat. After getting

what we wanted I began to shake the tree with the boys and they

all got scared and fell out. Less got two ribs broken, Little threw

his left arm out of place, Gid broke his left leg, and Jim got his

tailbone broke, and poor old Fess fell out at the same time and

got my left thigh broke. That was an awful sight to see five

brothers broke up like we were. Those days there was not a

doctor in forty miles of my

Page 31

mother's. She put splits on our limbs and put them in boxes to

keep them straight. The boxes were made out of six-inch

lumber. It did not take over thirty-three days until we were all

out to work again. We were all hurt that time, so mother could

not whip or quarrel at me.

In the same year, but in the fall, mother went to catch "Old

John," the old mule I went to mill on. Just as she went to put the

bridle bits in the old mule's mouth he turned the other end and

mother jumped back to keep the old mule from kicking her. Just

as she jumped she stepped on a slantin' rock and fell and broke

her right leg square in two. We had our mother carried home and

her leg dressed like she did us boys, and she could not use that

leg for seventy-four days. The old main stake was sick this time

and we got in the hole very bad and in debt, so I had to lay up

my education upon the mantle (made out of an old oak board),

and on November 1 I took me a piece of raw middling meat, a

piece of corn bread and two big onion heads and pulled out to

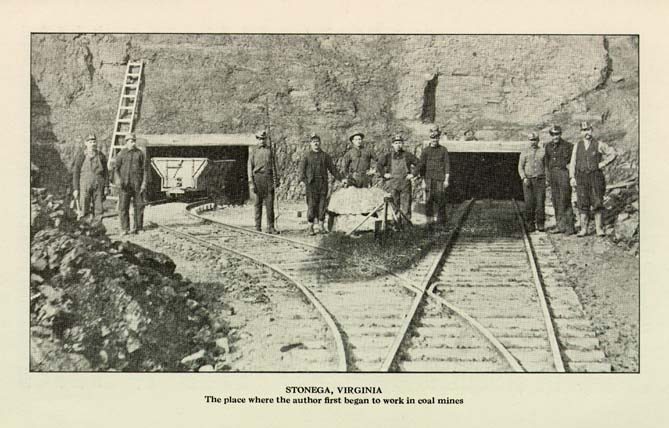

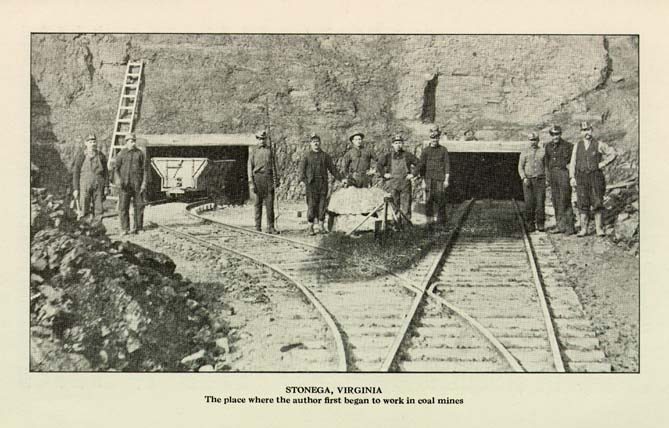

look for me a job. I pulled for Stonega, as that was the nearest

railroad, and no job there for a boy like me, so I went on down

Callahan Creek to Mudlick and tried, and there I got me a job -

the first job - and it was seventy-five cents per day, and board

fifty cents per day. This job was wheeling dust from a band

sawmill. After working one day and a half I white-eyed on

account of the dust and they could not pay me until payday, so I

took script for my pay. I then paid my board and bought canned

beef and crackers with the rest. That night I caught a boxcar of

coke and the train left Appalachia, Va., at 8:40 p.m. for Corbin

Ky., and I began then my first

Page 32

hoboing. I was on my first train, and on the third day I was set

off at Knoxville, Tenn., so I began hollering and some stranger

broke the seal, as I heard them call it then, and got me out of the

car and took me to a machine shop and told me to wash myself,

and I did. I was just as dirty as a black man not to be black.

After the whistle blew for dinner I walked up to the upper end of

the yard watching and trying to find out how to catch a train that

would take me back to Stonega, Va., for I was sure tired of

hoboing. So late that evening I met a colored man walking up

through the yard and I asked him where he was going and he

told me he was going to try and catch a through drag of empty

coke cars for Stonega, and that pleased me to death, and I

asked him how far we were from Stonega and he replied about

350 miles. So he said for me to go with him, and I did, and when

we got to the upper end of the yard we met another white man

headed for Cumberland Gap on our road. So when night came

we all went up a little ways out of the yard and made us a bed

down by a pile of railroad ties and made a fire and were going

to catch the first freight that went up the hill that night. So my two

partners asked me to go out to some of the houses and beg us

something to eat. I went and knocked on the first door I came to

and a nicely dressed lady came to the door and asked me what

I wanted and I told her a nice story that I had learned from my

partners. The good lady went and brought me a little wooden

tray full and some nice biscuits baked out of baking powder, which

are fine while they are hot, and after they get cold they are not

like sour milk bread, they are hard. So the good lady said to me:

"Young boy, I am not giving you these biscuits for your sake. I

am giving them to you for Christ's sake."

Page 33

I thanked her and looked her right in the eye and said, "For

God's sake put a little butter on those biscuits for me."

The good lady laughed at me and took my name, which I

gave her, and she gave me some very good advice, and it is still

in my heart today. I bade her good-bye and went back to my

partners. They were very well pleased, and after we had supper

we talked awhile and they taught me how to hobo, or catch a

freight train, and told many hobo stories around the firelight.

We all laid down about 9 o'clock that night on the ground by

a good fire. It was getting cool, that being in the early part of

November. When I woke up my two partners were gone and I

ran just as fast as I could up the hill after a passenger train. After

I came to myself I could hardly believe I had done what I had,

so I went back down the track to where our camp fire was

burning, and there I found the colored man's old cap and my hat

gone, so of course I put the old cap on. I did not know what to

do, so I decided to make a start back towards Knoxville. I was

then about three miles out of the city, and right in the upper end

of the yard I met two men. They tried to raise a talk with me and

went out to one side and talked and then came back to me and

asked me some more questions and finally they took me with

them and stopped behind an old dark house about two hundred

yards from where they met me and began to whisper, and I

believe as I am living today they meant to kill me. And in less

than a second it turned as bright as the brightest day you ever

saw all around me about three feet square. And those two men

just

Page 34

simply flew, and just that minute it turned dark again and I flew

the other way and in about two hours daylight broke and I

walked down in the yard to where a large train was made up,

as they are called. I crawled into one of the big hoppers and in

about ten minutes they coupled a large engine to it and I heard

the engine blow two long whistles and about that time a man

stuck a big pistol right in my face and told me to get out of there

and to get out d--n quick. I bounced the ground in a hurry and

begging and rolling on the ground playing that I had sprained

my ankle. The man tried to make me walk, but I still played off

cripple. He told me to sit down and he asked me what I was

doing there and I simply told him the truth and he got sorry for

me and told me that he would turn me loose this time, but

watch out for the second time. I asked him to get me a walking

cane, which he did, and I started hopping along up through the

yard. Just as soon as I got out of sight I threw my cane away

and sat down and took a good, long, hearty laugh and then got

up and walked seven miles to the nearest railroad station, and

while there I met an old soldier making his way for Stonega and

when the train stopped it happened to be a water tank station,

and while they were taking water my soldier partner broke the

seal and it was a carload of hay for Stonega. We both jumped

in and the next morning we were setting in front of the Big Red

Stable at Stonega. I got me a place to board and the second

day got a job in the mines trapping at 90 cents per day. Later on

I got a job driving a hard-tail, or a mule, in the mines at $1.30

per day. On the 20th day of February I went home on a visit

and took mother and the four boys in the lower room and

poured out

Page 35

Page 36

on the bed $23.00, all in one-dollar bills. They were all

scattered out on the bed. Everybody thought that was some

sight. That much money those days and money was scarce. I

told mother that it was for them all and for her to keep the boys

in school and I would go back to my job and make some more.

On the seventh day of May the mine foreman put me to

running an old-fashioned Jeffries motor. I worked one month on

that job and went home again. It was thirty-three miles across

the big Black Mountains and across the Cumberland River and

then across the Pine Mountains to old Uncle Oby Fields' on the

head of Big Cowan Creek, then across a small hill onto the head

of Kingdom Come (the creek which John Fox, Jr., wrote his

two books on), and down Kingdom Come to the mouth of it

and then down the river seven miles to my mother's at the mouth

of Rockhouse. That was a pretty good walk for a boy only

seventeen years old.

I gave my mother on this trip $45.00 and she was awfully

pleased with me and said: "Fess, we need the money bad

enough, but you air gittin' 'long bad in yer education, and I can't

hardly stand ter see yer do that."

"After I get the other boys where they can take care of

theirselves I'll finish my education," I replied, "I am now going

to jine the army."

During the Spanish-American War, February 12,1898, I

enlisted for two years or long as the war lasted. I was signed to

Company L, Fourth Kentucky Volunteers, and was stationed at

Lexington. After I had been signed to my company there was a

big fellow come around and asked something smart,

Page 37

thinking he was one of those smart fellows, and before he could

think I had knocked him down with a big garbage bucket and I

had him whipped before he found it out. That built my reputation

during my service in Company L.

My Captain was Ben B. Golden, of Barbourville Ky., and

before time to discharge us volunteers after peace was made

the Captain resigned and H. J. Cockron was signed as Captain

of Company L. And when the First Sergeant, James Day, of

Whitesburg, Ky. made out all the discharges for the Captain to

sign the Captain came in the office at Anniston, Ala., where we

were discharged, to sign the discharges and he took up with the

Sergeant alphabetically and asked about each man whom he

did not know personally When he came to my name he asked

the Sergeant if that was the man that laughed so much and the

Sergeant told him it was, so he had me put down excellent

character. Then Captain Cockron signed the discharges.

During the time we were in camp at Lexington some of the

boys in my company got body lice all over them and I got

scared and took my dog tent and stretched it up under some

hedge trees next to the railroad track, and the first night the train

went by at 11 o'clock and she whistled some awfully large yells

and scared me and I jumped up in my sleep and tore my dog

tent all to pieces. I thought the train was running over me. So the

next day I fixed my tent up and got me some wheat straw and

made me a bed and ditched the water around my tent and it

sure did do some raining that spring and my bed rotted.

Sleeping in so damp a place I took the fever and

Page 38

was taken to a hospital. After three days I was taken out of that

hospital and put in a division hospital, where I just did live. After

three months in the hospital some of the boys told me if I could

make my temperature register 98 degrees three times in

succession I could get out, and the same fellow told me how to

do. He said when the thermometer was put in my mouth and I

caught the doctor looking off to draw my breath hard so as to

cool the thermometer, which I did, and on the fourth day the

doctor ordered the nurse to bring in my uniform and to let me set

up some. So when they brought that dear old uniform it was rolled

up in a dear old American flag that I had offered to sacrifice my

life for. The doctors had given me up to die and had ordered the

nurse to wrap my clothes up in the flag so it would be placed with

me. It was over one-half of the time that I did not know anything,

but when I did come to myself mother was the first I thought about.

She had been notified, but on account of being so poor, no

money and so many miles away from the railroad she could not

come, but waited in great patience to hear from me. The first letter

I received after I could tell the nurse who my mother was and her

address I got a letter in return in a few days and it is still written

upon my heart in large American tears like the dear old mothers

are shedding for their loved ones who are in France today in those

cold trenches and dugouts and mud and water up to their waists

and the top of the earth covered with snow and ice nine feet thick,

fighting for the freedom of America, which we are sure to win if God

lets this world stand, and I believe we will win this war during 1918.

Page 39

After I got my uniform and put it on with many wrinkles in it

after being rolled up for about four months, I sure did look

funny. I was so thin the sun shined through me. After about

twelve days I got able to go and I was put in an ambulance and

taken to the Southern Depot at Lexington and transported to

Anniston, Ala., where I was signed back to my old company.

When I walked up through my company street there was the

worst surprised set of young men I ever saw. They all thought I

was dead and had forgotten me, but when they realized it was

sure Fess they all sure did rejoice.

As soon as I got strong enough to do guard duty I was put on

guard over at Division Headquarters. I was put on the third relief

and I dreaded to see night come. But about 11:30 that night the

corporal of the guard woke me up and said: "Get up, third

relief."

I got up, straightened myself up and got my belt and gun.

"Outside, third relief," he said, and lined us up and started

around with us. I was put on first post. My beat was from the

guardhouse to the end of No. 2 post, where there was a large

tent stretched up On the inside were two big dry goods boxes

and a dead man stretched on each box covered with a white

sheet. The corporal and the man I relieved told me that I was not

to let any dogs or cats eat on those men, and every round I was

to go in and look at them. That made the cold chills run all over

me and my hair stood straight up.

It was in the latter part of May and the wind was blowing and

it was cloudy. The clouds were running like they do lots of times

when the moon is shining.

Page 40

My post was up on a ridge and the railroad yard was down

on one side and the engine was running up and down

through the yards and the old bells ringing and on the

other side was an old coralle and every once in awhile

you could hear an old mule blowing his whistle sounding

just like "How are you, Fess?" On my second round when

I got up in about ten feet of the tent and the flaps were

flapping awfully and scared me very bad, but I went in and

looked at the dead men. When I started back, walking

very fast, an old cat about twenty feet of me went

"meow." I am sure I could have heard it one-half mile and

it just simply scared me to death, and when I got to the

guardhouse I loaded my gun and got my back up against

the tent and there I stood until I saw the first relief

coming to relieve me. Nobody knows how good I felt

when I saw the light coming down the ridge to relieve me.

I came off post duty at 10 o'clock and I was asked to

stay and assist the doctors in operating upon those two

dead men, which I did. I had to light their cigars and put

them in their mouths while they were cutting them up.

They took their insides out and put them in a dishpan, cut

their heads open and took their brains out separately and

took their backbones out and cut into twenty-four pieces.

The soldiers were dying from a disease called spinal

meningitis and they were trying to stop it. After the

operation their bodies were put back together and well

dressed and put in caskets and shipped home. After I got

my rest on guard I was picked out of the company and put

in the kitchen to help John Gibson cook, which job I held

until discharged in 1899. After I was discharged in

Page 41

1899 I returned to my old Kentucky home back in the

mountains, forty miles from the railroad, which I had to

walk.

After I spent thirteen days with my mother I slipped

off and walked to Jackson, Ky., a distance of sixty-five

miles, and enlisted for two years and was sent to Cuba

and was signed to Col. Teddy Roosevelt's brigade. That

was where Teddy and I first met. He soon took a liking to

me, and after the Battle of Santiago Teddy, without a

wound and I with a bullet wound in my left arm, took me

by the hand and said: "Fess, we have gained a great battle

for our country. You or I will be the next President of the

United States, and if you get the nomination I am for you,

and if I get the nomination I want you to be for me, for you

have a great influence in the United States."

We shook hands and parted. So Teddy was from the

North and had more votes than the South and beat me to

the nomination. But I was for him and am still for him.

After eighteen months in Cuba I was discharged and

returned to my same old Kentucky home. When Teddy

raised the standing army from twenty-five thousand to

sixty-five thousand I became a soldier again. I was then

twenty-one years old, that being August 23, 1901. For

three years I served. I was

Page 42

signed to the Fort Slocum (New York) Recruiting Station, and

thirty days later I was signed to the "114th Company, Coast

Artillery," Fort Totten, N. Y., under Capt. John W. Ruckman,

Lieut. Balentine and Kesling. After I had been in that company for

a few months the Top Sergeant made me chief cook, which job I

held for six months. Then I asked the Top Sergeant to take me

out of the kitchen, which he did. Then I had to go doing guard

duty again. I soon began to be an expert orderly bucker, which

I was hard to beat on. One time I know two of us boys were

picked to do orderly, so we took our bayonets and cut the guard

manual. McGlofin cut "C" and I cut "T" and I was beat and was

given No. 2 post. The next day about 8 o'clock in the morning

Capt. Landers walked up on me and said, "Why don't you arrest

those two men?"

I presented arms to him and came to port arms and

asked, "What two men, sir?"

"What two?"

"Yes, sir," I replied.

"Those two men going yonder," he said.

"What for, sir?" I again asked.

"For being drunk," he replied.

"They are not drunk," I said.

"I am going to prefer charges against you," he

told me.

"Very well, sir," I replied, presenting arms again

to him.

He went on down to the guardhouse to prefer charges against

me, and sure enough he met two drunken men that No. 1 had let

in. Old Toomy was walking No. 1 post, so the captain had his

belt pulled

Page 43

and put him in the guardhouse and I saw the corporal of the

guard coming with one man and I knew that my time was

coming next.

So the corporal came up and said to me, "Turn over your

orders," which I did. "Give me your gun and belt." I also did

that. "Forward march and down to the guardhouse."

I went, and at noon on Sunday everybody in my company

was very much surprised to see me in the guardhouse after I had

been beat for orderly. So in the afternoon the Sergeant of the

Guardhouse sent me and Toomy to our quarters under heavy

guards to get our old fatigue suits and to put our good clothes

away. Monday morning I was taken out with the rest of the

prisoners and lined up and counted and then signed to do certain

work. I was put on the slop cart and a guard over us. We had to

go to all the quarters and mess halls and get the slop and haul

it off. I and Toomy were to be tried at 10 o'clock and it was

raining something awful. My old campaign hat had leaked

and my face was all striped with dirt, so when we got over to

headquarters they put Toomy on trial first and the court placed

Toomy's fine at $10 and ten days in the guardhouse. They called

me in before the court and the judge read the charges to me and

asked me what I had to say.

"Not guilty, sir," was my reply.

The judge asked me if I wanted any witnesses, and I told

him I did, so he took the names of the witnesses and the

commanding officer's orderly was called in and the judge told

him what to do. So we started in on my case. The men that tried

me were commissioned officers and I was only an enlisted man,

but

Page 44

we were all working for Uncle Sam, so we started in on

the case and I stood in with them. After taking the proof I

asked the judge to give me ten minutes to argue my case.

The judge was surprised, but according to the army rules

he had to grant me that privilege, and if I ever did put up

an argument that was one time I did, and I soon won my

case, and right there I started building myself in the army.

Just after I got out of the guardhouse my old-time partner

Teddy Roosevelt, the President of the United States and

always doing something good for someone, had an

order issued from the War Department stating that all

non-commissioned officers must be first-class gunners. All

of the companies were lined up and asked by the Captains

how many wanted to go up for the examination. I stepped

out and all of the rest of the company laughed at me. I

was put in school at Fort Totten for a while and soon was

taken out of school at Fort Totten and sent to Fortress

Monroe, Va., to a fine army school, and from there I was

sent to Governor's Island, N. Y., and from there to Fort

McKinley, Maine. So after the officers thought that they

had me alright I was examined under orderly No. 52-189

and was qualified as a first-class gunner. I was examined

on a 14-inch gun at Fort McKinley, Maine. My target was

pulled by a tugboat making sixteen knots per hour and the

distance was twenty-two miles out in the ocean and I hit

the target four shots out of five. The target was only 12

feet square at the bottom and 6 inches at the top, canvas

stretched all around it and a 6-inch black stripe ; painted

around the target. One of my shots struck the small target.

The bullet which I used weighed 2,250 pounds and the

powder charge weighed 640

Page 45

pounds. I had to load and fire that gun every sixteen

seconds. Fort McKinley is located on the banks of the

Casco harbor, main channel to the Atlantic ocean, what

is known to the War Department as the "She Big Bar."

I was examined at Fort Totten, N. Y., on the rest of the

examination, which are lots. On Long Island Sound there

is one of the best army instructing schools in the army

today. After I had qualified as a first-class gunner then I

was promoted to a non-commissioned officer and signed

back to my same old "114th Company," then I was

appointed by my Captain as an instructor. I was picked

out of the New York harbor of 19,000 men and put on

the recruiting service on a salary of $65.00, board and

railroad fare and traveling expenses and going over the

country getting men for the army, which job I held until I

was discharged.

I was discharged out of the army August 22, 1904.

I now hold two discharges of excellent character, first-

class gunner and non-commissioned officer's warrant.

Soon as I was discharged I bought me a ticket for Norton,

Va., from Norton to my old mining and railroad station,

Stonega, Va., and then I pulled across the Big Black

Mountain through the same old way as I had traveled

when a boy to my mother's home.

Soon as I got home all of the girls began to come in to

see me and I sure could court some. All the girls were

struck on me because I was a soldier, and after a man has

been a soldier for four or five years and gets back home

and there being so many pretty girls he wants to marry.

So I got struck on four real pretty girls, Susan Cornett,

Tina Breeding, Mary Amburgey and the one that made

the winning, Mantie Ison. When I made up my mind

which one I loved best I sure set in to courtin'.

Page 46

I first got struck on my wife it was down on Caudill's Branch

to "old Stiller Bill" Caudill's funeral. He had made so much

moonshine that he bore the name of "Stiller Bill." He had been

dead ten years and had 12 grown children, 187 grandchildren

and 91 great-grandchildren to mourn his death. His funeral was

preached by the old regular Baptist and Ira Combs was up

preaching. It was then that I looked under a big beech tree and I

saw a big, fine looking country girl. She weighed about 160

pounds, had blue eyes, black hair and big, fine, red, rosy cheeks

that God had given her and she had a nose as large as a banana.

Something went down in my heart and it really smothered me

so I kept my eyes on her, and the more that I looked at her the

prettier she got. Finally she got up and went out to an old

country spring to get a drink, so I got up and went out to follow

her. I went right to her and said, "Mantie, I am struck on you."

"Now you are just trying to make fun of me," she said.

"No, I mean what I say," said I, and so we began to talk and

she and I went back down to where they were preaching.

After the meeting was over I asked her what she was riding

and where her horse was. She told me she was riding "old

George." The horse had built a good reputation by being a good

horse to tram logs. So I rode by her side home and after we got

home we began sparking and after months courtin' we one

Sunday were sittin' in an old-fashioned country rocking chair out

in the back porch. I had her talked down and all she could do

was just rock and nod her

Page 47

head to what I said. She had never seen a railroad or a train of

any kind and she had never been to Whitesburg, the county seat

of Letcher. She had been kept out of school to help her father

run his farm She could not talk up with me, so I got her head to

nodding to everything I said, and I asked her what she thought

about us getting married. She nodded right into it and I went

home that evening tickled to death, I was so well pleased I

couldn't sleep a wink that night.

The next morning about 4 o'clock I got up and got my horse

and pulled for Whitesburg to the County Clerk's office. It was a

distance of about eighteen miles and was on December 13, and

the worst old sloppy, muddy time ever was, but I didn't care,

for I was goin' to git married.

After I got my license I pulled back down the river and got to

her home just before daybreak and went in. They all slept in one

room, had five big feather beds and my sweetheart was laying in

one of them. I told her to get up, that I had them.

"Got what?" she said.

"The license," I told her.

She just laughed at me, and don't you know I had to set in

and court her about ten more days before she would agree to

marry me.

After she agreed the second time we set the day. About

seventy-five or a hundred people came in to help eat the

wedding dinner, and the biggest part of them stayed for the

dance. When we all started around on Elk Creek to get married

I turned my horse over to my wife to ride and her father brought

out an old mule for me to ride. She had the name of

Page 48

being the meanest mule in Letcher County. Her name

was "Dinah." So I put the saddle on and she only humped

up a little, but when I put my foot in the stirrup and threw

my leg across the saddle the old mule started right

around the hill with me bucking and jumping. And mother

began shouting and my wife liked to fainted and had to

be taken off my horse After we all got straightened out

we all went down on Elk Creek and the late Jim Dixon,

founder of the old Regular Baptist Church of Indian

Bottom, told us to stand up and to look him straight in

the eye and said don't neither one of you laugh or cry.

And the good old man went on and married us. Soon

after our marriage we moved out to keep house in an

old schoolhouse on Burton Hill.

Mother gave me six hens and one rooster, one old

sow and one pig, one cow and calf, one big feather bed

and two pillows and my wife got the same from her

folks.

We started out living very nice and happy, but my

mind was on rambling, as I had been traveling. On

January 7 my wife became sick and I had to go after Dr.

Roark on Montgomery Creek, about eighteen miles. All

my father-in-law's mules were gone to Stonega after a

load of goods except old "Dinah," and I was compelled

to ride her. So I saddled her up about 4 o'clock in the

afternoon and a man held her until I got on, then I struck

out down the river and up Elk Creek across a big mountain

and on to the head of Bull Creek, up Bull Creek apiece

and across another hill on to the head of Montgomery and

down Montgomery to the mouth of Dr. Roark's Branch,

up the branch to Dr. Roark's house. I got there about

Page 49

Page 50

10:45 that night. Dr. Roark could not come and fixed me some

medicine and I started back and went out to the fence to where I

had hitched old Dinah and when I went to get on her she started

down the branch kicking and bucking. I finally stopped her and

got her started out O. K. down the branch, and as I went

back across the mountain at the head of Montgomery it was very

dark and my old friend "Dinah" got out of the road and we

got lost in the top of the mountain. I got off of my old mule, took

the bridle in my hand and started for the bottom of the hill and I

came to a little log house dobbed with mud and a board loft,

nowadays called the ceiling. I yelled and yelled and finally a man

came to the door and said, "What do you want?" I asked him

who lived there and he told me John Hall. I got down and went

into the house and he took one of the boards out of his house loft

and split it up and made a torchlight and told me how to go and

went out to the fence with me. I got on old Dinah and the man

handed me up the torch, made out of boards, and when I started

the sparks from the torch began to fall on the old mule and she

began to run and kick. After a little distance I had to throw the

torch down and I was in the dark again and in the mountain. I

had to let the old mule be the boss, as she could see and I could

not. Finally she got in the road again and didn't stay no time until

she got in under some pines where it was awfully dark and got

lost again. Along about 2 o'clock in the morning I rode up to

another log hut. After yelling several times someone came to

the door and I asked him who lived there, and he said John Hall.

There we were back to the same place again. I asked Mr. Hall

if there was not another road I could take that would

Page 51

get me out of there. He told me how to go through the hill to

Preacher Jim Caudill's, my old school teacher. And I started off,

and after about one hour I got on top of the hill and got lost

again. It was so dark and I could not find my way out, as there

were no moon and stars shining. So I got down and took my

bridle in hand and made for the bottom and just before daylight I

came to another house and hollowed and a woman came to the

door and asked me what I wanted. I inquired who lived there

and she told me John Hall. Now, I thought I had come to a new

house on account of the woman, but when she told me John Hall

lived there I thought I would fall off of that old mule I was so

surprised and I simply got down and went into the house and

waited until it began to break day.

After it got light I started and finally got out of the head of

Bull Creek and got back home just as they were eating

breakfast. My wife very much improved.

My father-in-law, Jeff Ison, had been elected Justice of the

Peace, and J. P. Lewis had been elected Judge, and as yet no

Constable had been elected, so my lather-in-law began to beg

me to let him have me sworn in as his Deputy Constable. My

wife cried and made fun of me, but Jeff and I got on our mules

and rode to Whitesburg to court, and Judge Lewis, now

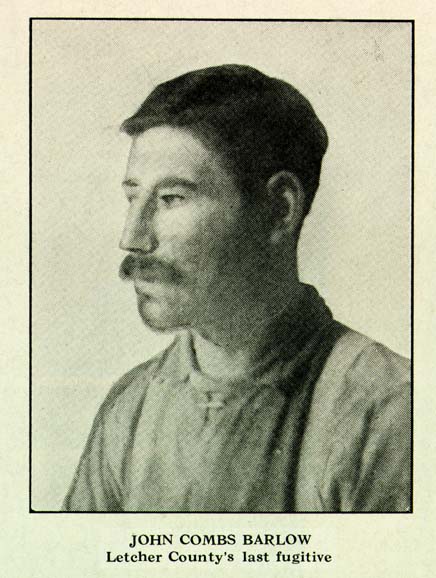

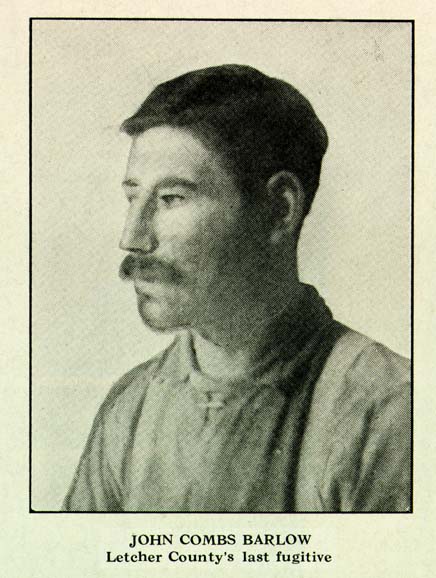

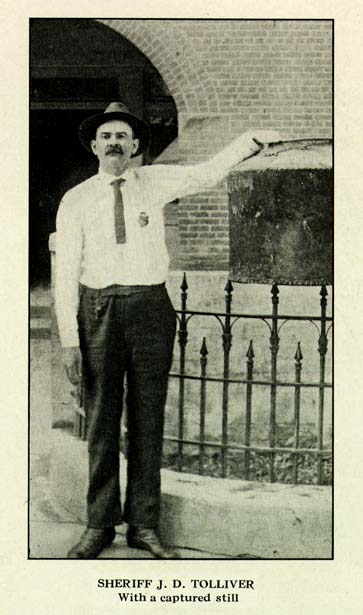

Secretary of State, swore me in for the office. The first raid I

got in was the arrest of twenty-two men and women, known as

Barlows and Engles After I got the warrants I did not summons

anybody to help me. I played Johnnie Wise and got all the dope

I could on them. There were three bunches of them. I got one

man to help me one night and I had to cross

Page 52

a very big mountain, and about 11 o'clock in the night I was right

in the head of Island Branch and I slipped up to a little old board

or log house that stood on the side of the hill. It had board doors

and no windows and one old big chimney and puncheon floor

made out of chestnut wood. I had a mall in my hand and two

good guns on me. The first thing I did was to hit the old board

door with the old hickory mall with all my strength, and when I

hit the door flew open just like lightning had struck it. I was in

the house before you could tell how I got in, and I summoned

everybody under arrest. Four men and three women came out

of those old shuck beds just like wild hogs and come right at me.

My man I had summoned to help me had got scared and run off

and left me. I began shooting at them, not to kill, but to scare

them. I knocked down two of the men and while I was putting

handcuffs on them one man by the name of Nathan Engle went

up the chimney and got away.

So I brought my two men and three women over to George

Whitaker's, at the head of Tolson Creek, and got breakfast. I

then took them down to Jeff Ison's and fastened them up in one

of his rooms. I then set out to catch Nathan Engle, the one that

had got away from me. So I waylaid a small road on the top of

Campbell's ridge and just as he passed I nailed him and took

him and put him in the same room with the rest of them.

The next morning I went down to Lower Caudill's Branch and

got all of them except Mary Engle. She had taken refuge in a

large cave just opposite Jeff Ison's on top of a high ridge. Her

mother was a very poor woman and she came up and told Jeff if

he would

Page 53

give her ten pounds of side meat she would tell where Mary

was. So they traded and Mr. Ison told me. I summoned Gid

Hogg to help me make the arrest. I placed Hogg in the county

road at the foot of the hill and as I was going up Elk Creek I got

in behind her and was in twenty feet of her before she knew it.

She made for the cave and I fired at her. Before I got to the

cave I saw two bright objects back in the cave about sixty feet. I

ordered her out three times and the last time began firing in the

cave. I saw her start. The mouth of the cave was full of smoke

and she ran by me and took right down the mountain. I took

right out after her. She ran over rocks, brush, and a straight line

to where I had Hogg placed. When she saw him she whirled on

me and made for her bosom. About that time I nailed her and

told Mr. Hogg to search her and he took a .38 bulldog pistol out

from under her arm beneath her dress waist. She was so mad

her teeth just rattled. She had a red calico dress on, which cost

about five cents per yard, and a twenty-five-cent boy straw hat

on which was painted red out of poke berries and three chicken

feathers dyed blue in the right side of her hat. She was

barefooted and her feet were all scratched up where she had

been hiding and running around in the woods so long. So I took

her in and the next day we tried them and they all were

convicted and found guilty. I took them all to Whitesburg, a

distance of eighteen miles, one day walking and had them all

locked up in jail.

Two years ago the same Nathan Engle betrayed his father-in-

law, Billie Combs, and told him that he would go with him down

in Perry County and help get his wife back, who was known as

the famous horse

Page 54

thief of Kentucky for a woman. So poor old Billie got

him a piece of meat and bread and went with him. Nathan

put him under a cliff and told him to stay and he would go

around to one of the Sloans', who had taken Billie's wife,

and get her to come and talk with Billie. The old man fell

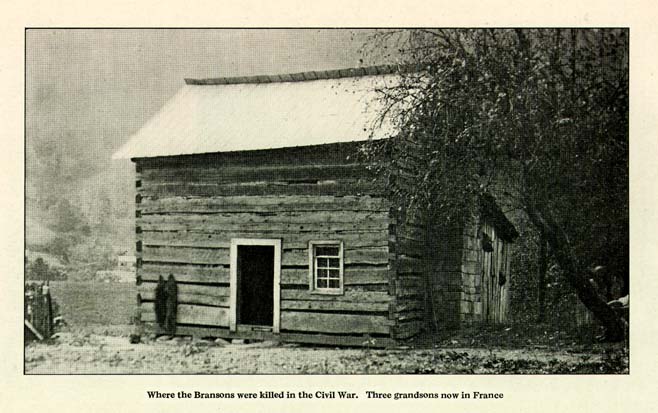

asleep and Nathan slipped back and shot out the old man's

brains and come through that night to his mother's. The

old man was found dead on the third day by an old man

cow hunting. He was brought back home that day for

burial, and Nathan met the train to help take care of his

dead father-in-law, whom he had killed. When the train

stopped at Blackey the Sheriff stepped off and captured

Nathan and he was taken to Hazard and put in jail and

tried and sent to the pen for life.

In April, 1905, I was plowing a yoke of steers in the

old bent field on Burton Hill and there was nothing but

saw briers. My wife was helping me; she was driving.

About 10 o'clock the old steers took a notion to go to

the river. They raised their heads and started. My wife

had a rope on one of them and tried to hold them and got

her foot hung under a bunch of those saw briers and fell

down. She cried awhile and then I helped her up and we

quit work. The birds and the toad frogs were singing and

my mind became rambling and I pulled for Texas, the old

Lone Star State, and stopped in Big Springs, Texas. I

soon got a job with the carpenters working some three

months there. I was employed by the Connell Lumber

Company, which job I held until the panic of 1907. After

I was out of a job and no money, and having a wife and

one child, I began to realize what I had to do. So the T. &

P. Railroad shop was there and Mr. Potten was master

mechanic of the shops. I laid

Page 55

away for him one evening and hit him for a job. I had

been told by Fred Leper when I shook hands with Mr.

Potten to hold tight to his hand and tell him about Teddy

and myself in Cuba and I would be granted a job. So I did

what Fred told me to, and it worked just like a clock. A

job there was sure worth something. A man had to work

in the shop those days when the times was good about

eighteen months before he could get out on the road or

ever be able to fire the engine for old Uncle Johnnie. I

began on Monday; one week and ten days I had worked

out of the pits to a bell cleaner and I was cleaning a bell

one day on one of those big Western Blair engines and

George Tamset, the roundhouse foreman, come to me

and told me to go out there and fire the switch engine for

Uncle Johnnie. There had been a wreck up at Midland

and the fireman had been taken off of the switch engine

and sent to help bring in the wrecked train. So I got on

the switch engine one day and Mr. Davis got mad at me

because Mr. Tamset had run me around all of the

roundhouse men and I was not to blame. I done the

work and done it right and looked after all of the

company stuff. So Mr. Davis began to say dirty things

about me and finally Homer Scragins told me that Davis

was carrying a gun for me and had threatened my life

and would not speak to me.

I went home and got me a good .44 pistol and put it

under my overalls while I worked and at dinner I would

beat the other boys back to our room. Three of us boys

were using the same box to keep our dirty clothes in and

put our soap and towels in. When the boys would open

the box there was the .44 there.

Page 56

When they got their soap and towels and go on washing I would

slip the .44 back in my pocket for protection. One day I passed

where Davis was working on the engine and I heard him say,

"There goes that d-- r--." I had my gun on me and as I went back

to where I was working he struck at me with a monkey wrench.

Then the shooting began. I put everyone out of the roundhouse.

Billie Lee, assistant foreman, jumped in the turntable pit, and

Davis ran through into the blacksmith shop and ran over the

blacksmith foreman and got away and never has been heard of

since. Of course, I lost my job for fighting on duty and got tried

for shooting Davis.

Davis failed to appear against me and the judge dismissed

the case. I got tried for the pistol, was prosecuted by County

Attorney Brooks, now in France, and defended by Marson &

Marson, and I beat the case. They never could prove when I put

the pistol on me. They proved I had it in the box and I proved I

had the right because my body had been threatened. I lost my

job and beat my cases. I couldn't get another job and so I had

enough of money to buy my wife a ticket, so I bought a ticket

for her home in Kentucky by the way of Louisville and Stonega

and thirty-five miles on a mule home.

I then started on another hobo trip looking for a job. I went

to the yardmaster in the Big Springs yard, whose railroad name

was Bawley and told him I wanted to go to Aboline,

Texas, on

a freight, so he put me away in the old yard shanty and told me I

would get out about 11 o'clock that night. But I failed to get out

until 4 in the morning. He put me in the third car from the

engine, and when I got in

Page 57

the car there were two more hoboes in the car, and by the time

we got to Sweetwater, Texas, there were eleven of us all in the

same car, all hoboes. So we pulled into Aboline about 3 o'clock

the next day. I soon found out that there would be a madeup

passenger train out of there over the Wichita Valley Railroad to

the Fort Worth & Denver Railroad, so I went to the baggage

man and showed him that I belonged to the I. O. O. F. and

W. O. W. and was dead broke and got him to agree to carry me,

and he told me to go up to the water tank and hide in a bunch of

mesquite bushes on the right, and when the engineer or Hog

Head, known among railroad men nickname for engineers,

would look back for the flagman's highball and run and get

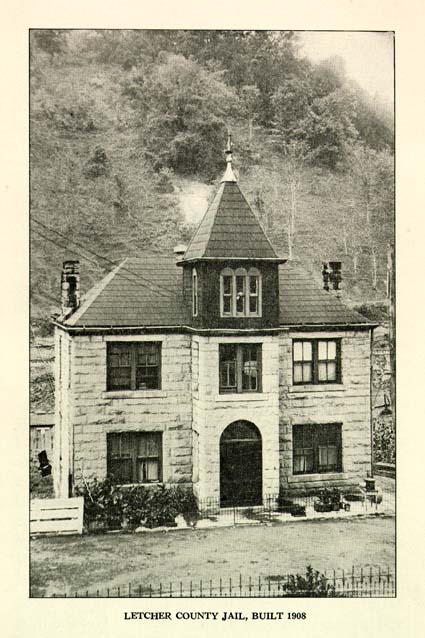

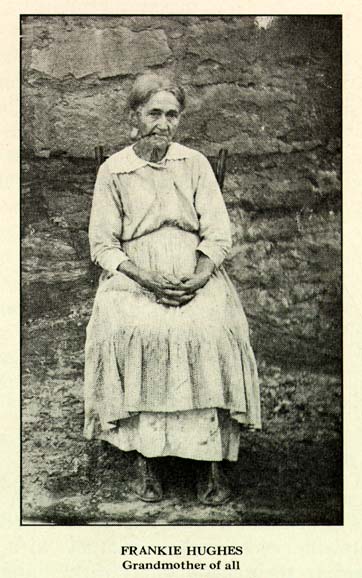

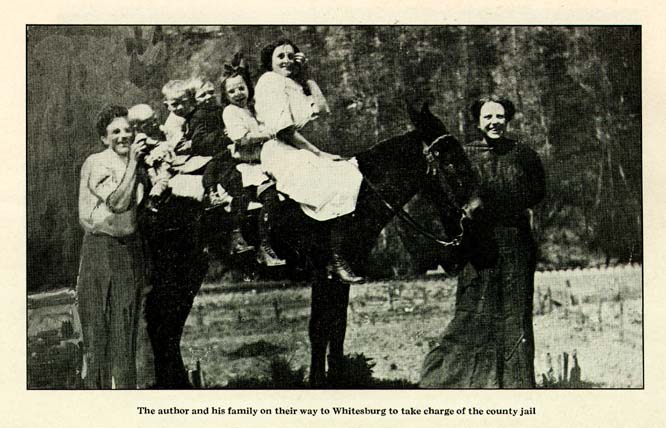

between the water tank and baggage car and after he got a