Clarimonde: A Tale of New Orleans Life, and of the Present War.

By a Member of the N. O. Washington Artillery:

Electronic Edition.

Bartlett, Napier, 1836-1877

Funding from the Institute of Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Ellen Decker

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Lee Ann Morawski, and Jill Kuhn Sexton

First edition, 2000

ca. 175K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

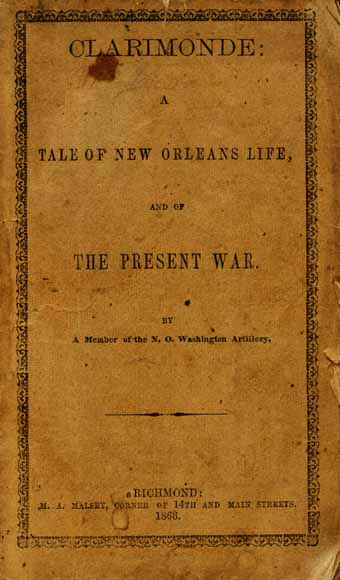

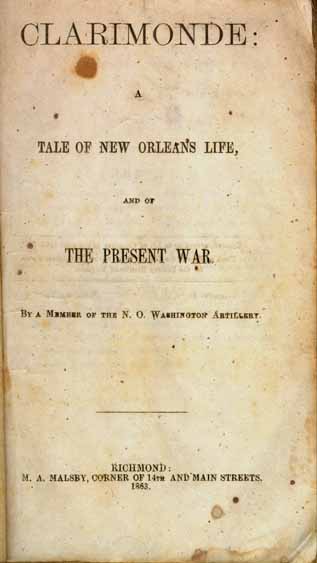

(title page) Clarimonde: A Tale of New Orleans Life, and of the Present War. By a Member of the N. O. Washington Artillery.

Napier Bartlett, 1836-1877

84 p.

Richmond

M. A. Malsby, Corner of 14th and Main Streets

1863

Call number Conf. Pam. # 424 (Rare Books, Manuscripts, and Special Collections Library, Duke University Libraries)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

This electronic edition has been created by Optical

Character Recognition (OCR). OCR-ed text has been compared against the

original document and corrected. The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

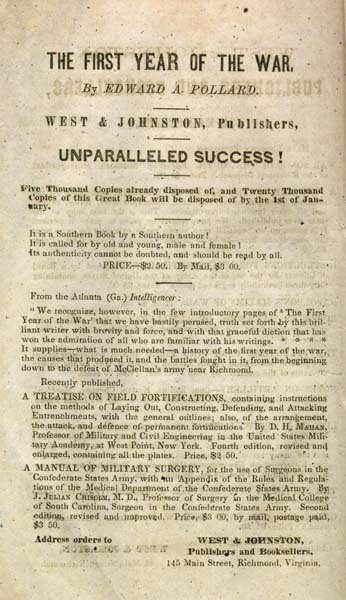

The publisher's advertisements on pp. 81-84 have been scanned as images.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- French

LC Subject Headings:

- New Orleans (La.) -- Fiction.

- New Orleans (La.) -- Social life and customs -- Fiction.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Fiction.

Revision History:

- 2001-03-13,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-12-07,

Jill Kuhn Sexton

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-12-04,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-11-27,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcription and TEI/SGML encoding.

CLARIMONDE:

A

TALE OF NEW ORLEANS LIFE,

AND OF

THE PRESENT WAR.

BY

A MEMBER OF THE N. O. WASHINGTON ARTILLERY.

RICHMOND:

M. A. MALSBY, CORNER OF 14TH AND MAIN STREETS.

1863.

Page verso

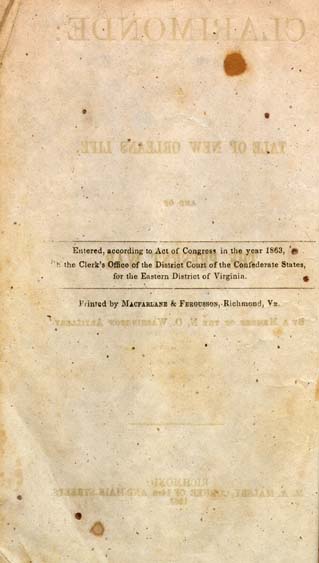

Entered, according to Act of Congress in the year 1863,

in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Confederate States,

for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Printed by MACFARLANE & FERGUSSON, Richmond, Va.

Page 3

PREFACE.

With some hesitation, the author submits a work composed amid the vicissitudes of camp life, and which, in the number of accidents by flood and field, which it has met with from its commencement until its formal delivery into the publisher's hands, has exceeded those of the heroine whose name it bears. It was written to amuse a few friends, and to while away the dull hours not employed in fighting, forced marching, eating and drinking. At the instance of these partial critics he has placed his MS. in the hands of a publisher; and trusting that the good nature which has hitherto been shown to soldiers will be extended to him whose only fault, after all, will be that he has attempted to please, he submits the following work to the reader's indulgence.

Army of the Potomac, Feb. 14th, 1863.

Page 5

INTRODUCTORY CHAPTER.

I had been put on guard, along with two or three of my comrades, over the provision or commissary tent of our brigade--a post much sighed for and coveted by sentinels who prefer spending their midnight vigils around a blazing fire to promenading on a lonely post during a stormy night.

With a pot of coffee, a canteen of liquor, cigars, and perhaps a deck of cards, the night passes more like a pleasant dissipation than ordinary guard duty. Thus whiling away the dull hours, comrades who have been little intimate grow social, old friends more friendly, and secrets are told, and confidence reposed which would never be communicated in any other situation. At any rate such was the case with us.

It so happened that towards midnight our game of euchre grew wearisome, the last fight had been discussed, and the prospect of another debated; it began to be evident that we must turn to some more exciting theme for our night's amusement.

Another hour was spent in recounting tales and adventures we had read or heard of, by which time we had grown personal and confidential, and the various trials with which fortune had favored us each, were in turn related.

Depend upon it, reader, that each of your numerous friends and acquaintances has a story worth the hearing, if he only knows how to tell it. The romance of life is not all confined to works of fiction, and the materials are around you to compose a book as humorous, sentimental and satirical, as the adventures of Gil Blas himself.

There happened to be on guard with us a sentinel who associated but little with any one in the regiment, and of whom almost nothing was known except that his name was Oscar St. Arment. In his appearance and character, so far as we could understand it, there was absolutely nothing that would attract your attention. His face was neither handsome nor repellant, his figure neither gracefu nor ungainly. In gait, bearing, and general expression of countenance, you could discover nothing in the man which would have distinguished

Page 6

him from twenty others whom you might have seen in the same day. Nobody that met him ever asked, "Who is that man?" And if the question had been asked, none of his companions would have been able to answer it. His face was, indeed, a practical repetition of the knife-grinder's answer, "No story to tell, sir." At least in this light we viewed him for some months after we were thrown together; and long after the mutual foibles and failings of the rest of us had become too familiar to talk of and laugh over, Oscar remained as unknown, as unthought of, and as little seen, as on the day he first became a soldier.

This, which was in itself a peculiarity, at length provoked comment, and close observers began to discover in his face lines and features that were by no means common-place, and to suspect that he must have seen more of life and had more of a history than his listless indifference as to everything around him would have seemed to indicate; so that it had thus happened that there was a common desire to know more of him who at first had least attracted our notice.

Thus, as each of us recounted the incidents and buffetings of fortune we had thus far met in life, there was a general disposition manifested to drag St. Arment in the conversation, which he could not well resist. Besides, the liquor, singular as it may seem to any one who has tested the whiskey we obtained in the army, was excellent. We were in constant expectation of a great battle, and for once, the first and last time, our taciturn comrade brightened into animation, and gave us one true glimpse of his inner self. His manner, half humorous, half satirical, and always melancholy, I can hardly hope to imitate or describe, but I give below, in his own language, to the best of my recollection, the substance of his narrative.

Page 7

CHAPTER II.

My first impressions are of a black nurse, with a turban wrapped around her head, like the tiara of Cybele, who dandled me in her arms when I was fretful, who soothed me to sleep in negro French, and who dropped me down the steps or over the banister when she was herself asleep, which latter was more than half the time her normal condition.

My existence was otherwise embittered by being plunged daily into a tub of cold water, and I began to regard her as my worst enemy, when she carried me to school, (where only English, of which language I knew nothing, was spoken,) dressed as a girl. Here I was forced to sit between two bouncing country girls, who, between constant pinching and kissing, well nigh filled my cup of misery to the brim.

I remember myself as I grew older, a little white-headed, round-bottomed shaver, early harnessed to the car of learning, and who drew it, balked and floundered with it, from a-b ab, and b-a ba, to baker, and shady, for what seemed to him a cycle of ages. Noah Webster's spelling book was a dreadful load; I would commence and re-commence it with every new teacher, without making any sensible progress that I can now recall; nor, indeed, can I recall much else, excepting that I was systematically flogged by each and all of them.

In course of time I had learned that six small boys could sit on one long bench, a fact which, had I not seen it so distinctly stated in print, I should have been inclined to doubt, for the reason that I was continually tumbling off the longest bench in school, whereon sat five other scholars. I would sit dreamily making triangles and parallelograms on the sanded floor, with my bare feet, endeavoring to account for this contradiction between printed statement and daily experience. I finally concluded that we were an exception to the rule, because, as I found in examining the matter, there were really only five boys, the sixth being a girl, whom I now remember as little Clara, and who, with myself, constituted the right and left file closers of this over-crowded bench. I could only conjecture how the

Page 8

small boys behaved in the spelling book, but practically I found that they were always pushing and pressing towards one end or the other, and that either Clara or I was crowded off, and suffered punishment as the guilty parties.

As the summer days passed by we read together the stories of the speculative castle-building milk-maid; of the dog, (nobody's enemy but his own,) whose character was damned by an unfortunate selection of friends; and of the industry of the little busy bee.

Whatever other changes were going on in my education, I found that the floggings and trouncings which I received from my kind preceptors remained ever the same.

To the last Clara and I were always blundering, always unfortunate, and ever being made victims when luckier culprits made their escape; so that similarity of trials and punishment, as much as of character, made us in the end the best of friends.

When one of us was in trouble the other would testify his or her sympathy with what mute signs and telegraphic signals were in our power. For instance, on one occasion, some mischievous neighbor had poured a bottle of syrup on a dress which Clara wore for the first time; the sight of my little ally tearfully defending herself from the flies, had disturbed the order of the school; and as a happy way of ending the confusion, she had been sentenced to stand in a conspicuous part of the room, before her mocking playmates. I saw that she looked at me for some signs of condolence, and hoping that I was concealed by the door from the observation of our teacher, I ventured to write on the wall, bending on my seat with my knees, in characters large enough for her to read--I love you, Clara.

But from this absorbing occupation I was rudely aroused. A shower of blows was fast descending on my quivering shoulders; I was jerked up by the collar, and made to dance first on one leg and then on the other; and in the end I found that I had need of as much sympathy as I had given.

Well do I remember the last day we played together as children. The term had closed, and it had been announced that we were to have a little party. The auspicious occasion arrived; ink spots had

Page 9

been scoured away, spider webs had given place to evergreen festoons, clean shirts and pants had superseded ragged trowsers and unwashed linen, while our faces glowed with expectation and an extraordinary rubbing with soap.

With the appointed hour the guests made their appearance; but as I have since found to be the case in more fashionable assemblies, after all our trouble, there still seemed to be, even when the last guest had arrived, something wanting; a painful ignorance as to what to do, now that we had come together. None of us were old enough to be very strong in a conversational point of view, and for a long time dancing was forbidden. The boys and girls being both extremely diffident about forming acquaintances, confined themselves principally to the opposite sides of the room, and hallooed forth their observations, as if it were important that no one should be excluded from their beneficial effect. Occasionally some modest youth, with a plentiful allowance of shirt collar, would be forced into receiving an introduction by way of encouraging the rest, and as if fate had marked me out for a martyr, I was among the early sufferers. Two youths, who were large enough to wear coats with tails, caught me each by an arm, and informed me that they would do me the honor of introducing me to the finest lady in the room.

I would have fallen on my knees and begged for mercy, had they not held my arms so tightly as to render it impossible. On they dragged me, vainly struggling and resisting, pursued by a shout from the crowd I was leaving, and welcomed with suppressed laughter by the one towards which I was advancing. Reaching the belle of the evening, some words were muttered, the import of which I did not understand, my legs were tripped from under me, I was thrust in a seat by the side of this lady, and with a farewell glance and a threatening jesture, which hinted that I had better stay where I was if I knew what was good for me, my tormentors left me to my fate.

I had at first a wild idea of jumping out of a two story window, which was just behind me; but my newly made acquaintance showed so much composure in her manner, that I began to feel reassured; besides, she struck me as being the most beautiful young lady in

Page 10

the world, and her dress, though simple enough, I thought, might have been that of a princess. There were some flowers in her bosom; I wondered if these grew there but did not feel bold enough to ask. She contrived to draw me into conversation, and listened with great good nature to what little account I had to give of myself, but I still continued to regard her with a superstitious feeling of awe. To complete my happiness, when one of my introducers returned, and alluded to my presentation as a capital joke, she thanked him coldly for having brought her such good company, and continued her conversation with me.

Finding at length that the boys were becoming more and more noisy, as that the party, about which we had so long dreamed, was a drag, Old Slapper, for thus was our teacher called, at length allowed us to wind up the day's festivities, with a reel, and presently we heard him tuning the harsh strings of his old violin. With my new protectress for my partner, my happiness was at its climax. It is true I felt a slight tinge of remorse that I was not with Clara, but I was somewhat consoled to observe that she was dancing very gaily without me.

I should perhaps have mentioned before that the boys of our academy were to appear at the party in white pants, but that, owing to somedelay, mine had not been finished at the required time. Indeed, not much more had been done towards making them than putting in what I believe is known as basting stitches. This did not, however, deter me from going and wearing them, and, indeed, I had forgotten all about their frail texture half an hour after putting them on.

Meanwhile the dance was progressing, and Clara, wild and imprudent as ever, who had taken the prize at the dancing school, and who I fear must have taken a glass of champagne that evening, was dancing as if mad. Be that as it may, when her turn came, as she started at the upper end of the reel, cried out that she would show us how she could imitate an engine, put on steam, sachezed right and left through the smaller dancers, upsetting them at every turn.

All of the evening her elderly chaperone had been eyeing her movements with an impatience which increased every moment, and

Page 11

now this lady indignantly ordered Clara to follow her to the carriage. Upon this, Clara, putting on still more steam, executed that rapid backward pas, which terminated the danseuse' performance in a theatre just as the curtain is about to fall, and with a magnificent bow, bade adieu to the festivities of the evening.

"Poor Clara, won't she get it, though," I murmured to myself; but undeterred by her fate, and anxious to take a sort of Terpsichorean revenge on the crowd who had witnessed her disgrace, I started down the reel with my partner; and I fear had soon forgotten her to execute some pas seuls of my own. It was not long before I had, in accomplishing these, turned around so often, and had drifted and danced so far away from her, that it was only by the most herculean efforts and extravagant figures, that I was subsequently enabled to regain my place, in doing which, I had inadvertently trod upon the miniature feet of the Cinderillas, and ground my boot heel upon the "light fantastic toes" of the whole line of dancers.

What I might not have further done I am unable to say, as I now began to be conscious that all was not right, and that my appearance had become the subject of general mirth. Vainly did I endeavor to divine the cause, faster and faster did I dance, when suddenly hearing the snapping of a thread, I glanced downwards.

With the feelings of a sailor who finds that his vessel is rapidly going to pieces, I discovered that my pants were fluttering wildly in the breeze, and dangled about my legs, as if merely attached by a spell. I had no time to finish my dance, or stand upon the order of my going, but sideling and shuffling, in double-quick time towards the door, I seized the first cap I could lay my hands upon, and ran home as fast as my feet would carry me.

All of this time I had been living in an old plantation house for the benefit, as my mother said, to be derived from the pure country air; but much more, as I have since learned, from her indifference, not to say dislike of children. But as I was now to return to New Orleans, in which was my family abode, it becomes necessary that I should give you some account of my parents before I proceed farther with my own immediate history.

Page 12

CHAPTER III.

When Louisiana was under the French government, my father held a title, and boasted a polysyllabic name. His rank, upon its cession to the United States, he renounced to become an American citizen, and his name, perhaps as another evidence of his republican principles, he eliminated of most of its long sounding syllables. A courtly old gentleman, with large black eyebrows and grey hair, was my father. His business in life was to do nothing, gracefully, and to spend the income of an immense estate, and finally the estate itself, in prodigal profusion. He would, for instance, give away a magnificent residence to some passing prima donna, in cases where, as my mother thought, a bouquet would have sufficiently evinced his admiration; and the loss of a mile of street lots was sometimes the result of a single night's amusements. The same magnificent profusion was preserved throughout the establishment, or I should rather use the plural form, as his residence in the country only gave a larger field for the exercise of his princely extravagance.

He was not of a nature to grow old, and had his years numbered the patriarchal time, he would have received the burden under protest, and still have made some youthful show against wrinkles and old age.

But thus long, or indeed the ordinary span, he was not destined to live. The tastes that I have mentioned, cost him his fortune. There was another, which resulted in his death.

While dancing gaily through life, shrugging his aristocratic shoulders at its many ills, and distilling pleasure from every source, without much troubling his digestion as to its effect upon those who might come after him, the pitiless fates who apportion to each of us the number of our days and hours, had summoned him to the realm of shades.

For, at the time of which I write, dueling was much in vogue, and nothing was thought more proper than to shoot your man before breakfast. In this, among other accomplishments, my father greatly excelled--was familiar with the temper of swords, expert in

Page 13

the use of hair triggers; and, in short, understood his business so well, that for him to engage in an affair of honor and kill his antagonist was thought to be a matter of course.

But it is time I should speak of my respected mother. If my father had to have his little pleasures, it was none the less necessary that she should have hers. She had been a reigning beauty in her day, and as numerous a train of admirers she still possessed, (she regarded them in the light of property,) as many rivals, with half her age and twice her remaining attractions. But the preservation of this power, which every day became more difficult, required her consummate skill and address, particularly in the art of the toilet; and, then, too, as innocence will be traduced, in spite of the utmost finesse in silencing envious tongues, she had, as a last resort, the correct sword and pistol practice of my father.

Thus strongly fortified, my poor mother found the world at her feet, and save an occasional timid whisper, no sign of mutiny among her overawed subjects. Not to know her, argued yourself unknown, and in spite of many ugly rumors, and suspected breaches on her part, of the conventional code, she could go where she pleased, and receive the flattery of her admirers in the most fashionable saloons. No debutante could hope for a success without her encouraging smile. Reputations crumbled beneath the weight of her sarcasm, and her delicate railery could banish as effectually as an imperial ukase. She was, indeed, recognized and regarded as a power.

But of her, as of other despotic rulers, the world at length grew weary, and her power first questioned, was, in the end, resisted. Only an opportunity was wanting for her influence to pass away forever.

Matters were in this state when the visit of some live prince became the event of the season. Of course there was to be a ball in his honor, and of course everybody wished to go. To obtain a ticket was a question of fashionable standing, and to fail in receiving one was regarded by many as a blow little less than the loss of fortune. So thought, at least, my mother, who began to see the difficulties of her position, and accordingly all of her seductive arts which had

Page 14

never hitherto failed, were brought to bear upon the ticket-dispensing committee.

The important night at length arrived, the costly tournure which the over-confident lady was to wear had long since been brought in, and still no card of invitation. But no one ever dispairs of an event upon which our happiness depends; and hour by hour glided by without her resigning, in anywise, her intention of dancing with the Prince. It was not until the notes of the band, borne faintly to her ear above the noise and confusion of the city, announced that the assembly was about to be opened, did my mother admit to herself that she had failed.

Yes, the festivities of the ball, which she had fondly hoped the Prince would open with herself and for the dance, were now commencing, and she not even present! Oh, horror! oh, misery! She saw before her the inevitable loss of her power, and it was not until my father gave orders for his dueling pistols to be cleaned; that she could be kept from fainting in his arms.

A name was now selected by lot from the number of those who composed the committee, a challenge sent, and at daylight the next morning there was a hostile meeting between the party whose name was drawn and my father. But this time, as if the gods had refused all succor to my mother's sinking cause, it was my father, and not as everybody had expected, his antagonist, who was brought home on the fatal litter. He had only time to declare the manner in which his body should be laid out, and intimate a preference for a rosewood coffin, before he breathed his last.

Though this blow was all that was wanting to affect the complete loss of her position in society, my poor mother did not cease to struggle. But I shall only stop here to mention her last appearance in public, and hasten on to what concerns my own life.

It was a night during the season that the yellow fever was daily numbering its victims by hundreds. Death was abroad everywhere, but the evening was so soft as to tempt her and a party of congenial spirits to a ride over the shell road--that famous avenue, bordered with groves, and which terminated a few miles from New Orleans, at Lake Ponchartrain. Only the midnight vigil lamps shone through

Page 15

the streets, and along the road, and nought disturbed the silence of the hour, save the slow rumbling of the hearse's wheels, an occasional shriek from some departing soul in the last agonies of death, or the forced merriment of the revellers themselves.

One might have supposed that they were bent on some such mission as that of the Memphians, who, carried at midnight the bodies of their dead across the lake that bordered their city. On the contrary, it was only the ordinary search after pleasure, and an attempt to leave behind the gloomy atmosphere of death.

Arrived at the lake, a supper of wines and costly dishes was ordered, which it was thought would add to the hilarity of the party; but it did not. Then followed bachinal songs and others in which an attempt was made to set death at defiance, but which were more inexpressibly melancholy than any funeral dirge. But the gaiety of the party was too obviously assumed; and at length, wearied with what produced only sickening disgust, my mother, who was the ruling spirit, and who now realized, for the first time, that she was growing old, reluctantly gave her consent to return home.

It was none too soon--the seeds of disease began to betray themselves before the party separated; and ere the close of the succeeding day, my poor mother was borne a corpse, yellow and spotted, by the black horses, to her final resting place.

Page 16

CHAPTER IV.

Thus sadly terminated the lives of my parents; and I, who was of so tender and thoughtless an age, that I was playing "hide and seek" the very day of the funeral, was left orphaned and friendless, and for aught that I or any one around me knew, without any near relation. Indeed, the city was so deserted by its inhabitants, that for many days there could be found no curator or administrator, to take charge of the household or myself; and each domestic or dependant did what seemed right in his own eyes.

From this melancholy situation I was at length rescued by the kindness of Pére Grivot, my mother's confessor; for the good lady, in spite of her worldliness, never altogether lost sight of what she was pleased to term her religion; and unburthened herself of her sins, with the utmost regularity. To the house, then, of Father Grivot, I was now taken, and installed as enfant de choir, or chorister of his church, until some one should step forth as my proper guardian. My duties were to ring the bell at early dawn for matins, to light the wax tapers on the altar, to attend at mass, and assist at funerals. Indeed, this last duty was the most important of my services, occupied most of my time, and brought in sufficient revenue to maintain me--it being the custom for the church to charge for funerals, according to the number of priests and choristers present--and the fund thus raised, after deducting the expenses of the vicarage, to divide among those officiating.

There were, I need not say, other choristers of my own age, and these, with myself, were left to our own resources, after the performance of the before specified duties. We lived well and were clothed well, and had an opportunity of making some progress in learning--those of us, at least; who showed sufficient inclination for study to invite encouragement. But the time of my youthful associates I soon found to be otherwise employed. Whether through a natural tendency to vice, or because we were so constantly going through the forms of religion, that it came at length to be forgotten that they had any meaning; yet, so it was, that the solemnities which

Page 17

inspired me only with a sentiment of awe, seemed to be regarded by them as a monotonous and wearisome business. They practiced their jokes while preceding the dead to the cemetary. They would cause the tapers to expire on the altar during the performance of services, or would place the principal singer, whose snuff-box had been previously filled with red pepper, in the embarrassing situation of being compelled to chaunt a requiem, while tormented with a constant desire to sneeze. But not satisfied with thus disregarding religion themselves, they had learned to profit by the devotion of others, and the money obtained from devout elderly ladies, they lost or won from each other in games of chance.

I was sufficiently old and thoughtful to understand that in the life I was commencing there was no future before me, and that my prospects had undergone a disastrous eclipse. With a natural temperament inclining to melancholy, and saddened by the tragic scenes to which I have briefly alluded, I could take but little interest in the livelier amusement of my companions. My time passed as in a sad dream, in listening to the heavy tones of the organ, in gazing at the frescoes and paintings on the walls, or in wondering at the ever varying crowds who were constantly entering and departing. Sometimes I would brood in a childish sort of way over the solemn scene that were transpiring around me--at the happiness of the bridal party, quickly to be succeeded by the desolations of the funeral cortege--the indifference of the young to religion, and the tardy devotion of those who had grown too old to sin. But the soulless mirth of my companions jarred harshly on such reveries, and doubtless created somewhat the same feeling in me. And if you sometimes find that I am callous to what should be held most sacred, remember the associations of my early youth, and thank your kinder stars that you were reared under better auspices.

One day, while pursuing some study under the direction of one of the younger priests, who resided at the house of Pére Grivot, there was ushered into the room in which we were sitting, a stranger, who inquired for the Pére. I had before remarked his presence at the church on gala days and at high mass, and had heard from the conversation of those around me, that he belonged to that

Page 18

pleasure-seeking class, who came with some less pious motive than to contribute to the support of the ministers of the church.

His dress, figure and general features, were unmistakably those of a Creole; and I knew before I heard him speak that he would commence the conversation in French. (Indeed, the latter language was then, and to a considerable extent still is, the ordinary language of the city and State, and the only one with which I was then, in spite of my experience at the country school, much familiar.) Otherwise, he appeared to be a man of the world, past the maturity of life, selfish, sensual and cynical.

He had just returned from Paris, I soon heard him say, in the course of a conversation with Father Grivot; and what brought him to pay the present visit, was the purchase of a lot in the cemetery, connected with the church. This business required little time to adjust.

"But whom have you here--some novice that you have picked up out of the gutter?" said he, alluding to me. "Come here, ma bonne ange. Too handsome by half, Father, unless you wish him to prove the ruin instead of the salvation of the feebler sex."

"You might well think him an angel, did you hear him sing. Heaven forbid that he should ever become a snare to any of the weak daughters of the earth. But Oscar is a good boy, and comes of a good family, too. Poor souls, his father and mother, are not only dead, but died bankrupt in position, wealth, and all that makes life dear. There was but little left them in this world when they quitted it."

"Possible? No friends, connection, or means of support left Ma foi, a very proper time to die. Yes, a fortune is very seldom sufficient for our own wants, much less for those who come after."

"And so," continued the good Pére, "as there was none left to care for him, and as his mother, in spite of her many transgressions, died in the bosom of the church, he naturally fell under our care. May Heaven and the pious instructions he will here receive, enable him to avoid the errors of those who have gone before him."

Page 19

"Your account interests me much," said the stranger, with a slight yawn, as he prepared to go. "But you have not yet told me the name of your protegé. I had almost fancied, from a similarity of feature, (were it not for the absurdity of the thing,) that he was in some way related to my family."

"His name," replied the priest, is St. Arment. Oscar St. Arment. May it prove more fortunate for him than for its last possessors."

His questioner, who had hitherto glanced casually at me with an air of languid hauteur, now regarded me with unfeigned interest.

"O, impossible! That was the name of the husband of my only sister. Poor Alceste! and yet he bears her features! It must be so. If what you say is true, this boy must be my nephew. Ha, Oscar, you may fling away your prayer book, now. You will go to live with me, and have something better to do than count beads. Would you take me for your uncle, boy?"

"You do not look like an uncle," said I, naively; for his cynical look had not impressed me in his favor.

"You will change your mind," said he, frowning, "as you grow older, and find that you have no other than me to depend upon."

He then went into further details with the Pére in reference to my history and that of my family, and then departed, with the understanding that I would be sent for the next day.

Page 20

CHAPTER V.

He was as good as his word. At the appointed time a sedate quadroon servant announced that a carriage was waiting. Then I bade adieu to the few friends I had formed; the door of the carriage was slammed with a great noise, which filled me with infinite terror; and with the feeling of a prisoner who is hurried off to his doom, I found myself on my way to my uncle's residence.

Arriving at my future home, the carriage passed through an arched vaulted entrance that ran under the building, and stopped in the court-yard or square. My attendant having ascertained that my uncle had not yet finished dressing, gave me permission to wander through the rooms and gardens until I should be summoned.

Who ever forgets the early impression of childhood? Though many years have passed over me since the morning I entered my uncle's, residence, the recollection of it is as vivid as ever. The grounds had apparently at one time been carefully laid out--being cultivated in squares and parterres, and planted with rare exotics. Otherwise, it was adorned with statues of the mythological goddesses. But the statues had now grown mouldly, the traces of cultivation were obliterated, and the utter negligence with which the vines and tropical plants had been allowed to grow, gave it the appearance of an Indian jungle.

The interior of the house through which I was permitted to pass, evinced but little more care in its preservation. The furniture was rich, little used, and neglected, evidently of a date and pattern long since become obsolete.

In short, about the whole establishment everything indicated the absence of woman's presence, and the little estimation in which the house was held by the owner.

At length I was carried into my uncle's presence. He was carefully dressed, and held in his hand a handkerchief scented with patchouly. After examining me attentively for a moment, it appeared that my costume did not please him. He flew into a tremendous

Page 21

passion with François, my attendant, for having brought me to his house without first carrying me to a tailor's, and swore it would be as much as his life was worth should he catch me in such guise again. He then charged François to be in permanent attendance upon me, and to see that I gave him (my uncle) no trouble.

Whether this meant that I was to obey François, or he me, did not exactly appear, but from the latter's manner, I should have inferred the former. Henceforth, from his interference and dictation, I was to have no peace. He prescribed, I soon found the manner in which I should eat; as well as the dishes themselves, and in this he was governed by considerations of fashion, rather than health. I was not even allowed to go to bed at night, or get up in the morning, until at such an hour as had received the sanction of the monde. However, I anticipate.

My uncle, after having roughly ordered me out of his presence, and at length concluded to let me stay, led the way to the breakfast room. But no sign of breakfast did I see, except, a cup of coffee. This he drank, allowing me to do the same, and then having qualified his with a petite verre of cogniac, led the way to his restaurant. I subsequently discovered that no kitchen was tolerated about the house, owing to the odor it diffused. My uncle's aristocratic nose could not bear that.

"The infernal smell," he complained, "kept your thoughts occupied with eating, when they should soar higher." However, I was never able to see that his ascended any more above eating, or the dull earth, by the banishment of his cook. Indeed, my uncle (I may as well speak of him at once as I afterwards found him) occupied himself with the subject of "Eating considered as one of the fine arts," to the exclusion of almost everything else. No bigot or blind enthusiast ever followed his creed with less regard to the consequences; and no friendship by him was for a moment thought of with one who differed from him in a matter of so much importance.

His hour of breakfast was 11 o'clock, but he would appear in his accustomed place at the restaurant at 10¼. The intervening time was spent in questioning the cook as to the purchases that had that

Page 22

day been made in the market. Sometimes he would even go himself into the kitchen with handkerchief to his nose, to inspect some rare delicacy. While thus engaged he would seem to gain a new dignity, and would give his orders with the air of a ruler dictating dispatches. The restaurateurs and waiters, high and low, held him in great awe, and would no more question his decisions in regard to food and wines, than would an eastern slave have disobeyed his despot's commands. He knew his power, and exercised it, too, and woe to the unhappy garçon who was unfortunate enough to offer him a dish which he considered low. His scowl was withering, and nothing would save the poor fellow from instant dismissal, but abject submission and an humble avowal that he did not know to whom he spoke.

If he was particular as to what he ate, he was none the less so as to the manner in which it was put upon the table. The table must be in a room large, airy and richly furnished. The crockery and glass must be varied with each dish or brand of wine, and before each plate there was always to be a beautiful bouquet of flowers. One servant only was allowed to attend in white gloves and pumps. When a friend dined with him--and this was an honor granted to few--he was expected for the time to resign all will of his own--all preferences for viands or wines. Criticism of a dish would have endangered his life. It was sufficient that the article appeared before him. He always served his friends, as well as ordered the meals, and for one of them to have presumed to do such a thing, would have been looked upon in the light of a revolt, and punished accordingly.

I have been thus particular in describing my uncle's table peculiarities, as therein lay his glory--his philosophy, and whatever beliefs he had formed through life. Otherwise, his time, and as I went with him, I may say my time, was consumed, dully, and unprofitably enough, in following the crowd and visiting the various public places of the city. He had for instance a box at the Opera; but the music was evidently a bore to him; and what he meant by going to the Opera, was to talk with his friends, or engage in a game of dominoes in the cafe. He would generally content himself with

Page 23

glancing through his glass at the other pleasure seekers, and if tempted to stay longer, would sleep through the rest of the performance. So that, between him and François, it was only when long after midnight, that I was permitted, at length, thoroughly exhausted, to retire to rest.

For some weeks after his finding me, my presence seemed to be an unfailing source of satisfaction; more, I have since been led to believe, from discovering an heir to his estate after his death, to the exclusion of certain distant relatives whom he detested, than from any genuine natural affection. After that period, his interest lessened, and as it was but too evident that I was in his way, I joyfully took advantage of his apparent desire to be relieved of my presence.

In my rambles over the house I had early found the way to the library; a large room well stocked with books, which seemed covered with the dust of ages. Here I soon learned to while away many dull hours--first, in looking at the pictures, and subsequently in reading the contents of those dust-covered tomes. With what delight did I at that age read the works with which the shelves were laden; which even at that day had almost become obsolete! I began to imagine myself a Scottish Chief--that I was surrounded by the New Forrest--that I inhabited Udolpho's mysterious chateau; and I am quite certain that I was as melancholy and unfortunate as the noble Thaddeus of Warsaw himself.

At one time I fell in love with the "Bleeding Nun," but soon abandoned her to pursue my amours as a gay, blue-cloaked cavalier in the streets of Madrid. I adopted the career of a bandit, with an occasional relaxation to make a piratical excursion over the blue waves; I jumped unharmed from precipices many hundreds of feet high, and eloped with a female Vampyre--was buried alive in damp vaults, and cut my way through rock-ribbed prisons.

I was at length resurrected from this life in a summary manner. Unfortunately, or perhaps I should say, fortunately, for me, my digestive organs were not made after the same pattern as my uncle's, I was impolitic enough one day to say, on being asked why I did not eat of a certain dish to which he had helped me, that it made me

Page 24

sick. He instantly flew into a violent rage, and almost so far forgot himself as to strike me before the friend who chanced to be dining with us, when that friend averted the storm which was about to burst over my head, by inquiring if it were not time that I was sent to school. I can see the expression of my uncle's altered countenance even now, as this bright idea entered his mind.

The columns of a newspaper were immediately referred to, and the advertisement of M. and Mme. Baudoin appearing to be the most promising, François received immediate orders to have me transferred to his care. It did not take me long to make my few preparations; and secretly pleased to escape from a life which had no charms for me, I entered the Pensionaire de Baudoin the next day.

Page 25

CHAPTER VI.

M. Baudoin, I soon found, was a little, bald-headed gentleman, with protruding eyes, who had come to this country as a gardener. Matters not prospering with him in this capacity, he had contracted a marriage with a certain milliner, and tradition represented that the institution which he now had under his control, had been given him as a bonus, upon the completion of a marriage with some one who had previously been the cher ami of the lady in question. The world had looked coldly upon the institution of Baudoin for some time after its commencement; but in process of time it came to be discovered that his grounds--for he was a good gardener--looked as blooming as the garden of the Hesperides; and that the female pupils of Madame dressed with more taste and fashion than the young Misses of any similar institution in the city.

Neither of the heads of the school interfered actively in our studies; these being confided to subordinate teachers, who deserved the credit of what progress we made, if we made any, in our studies. Madame we never saw excepting on the streets, riding or promenading, and very gaily dressed; while Monsieur, her husband, jogged through life contentedly enough, snipping and clipping away at his shrubbery, and making bouquets for his patrons and favorite female pupils. Engaged in this occupation, we were allowed to admire him at a distance, but in no wise to approach or disturb; and any attempt to trouble his intellect with questions connected with our studies, would be visited heavily, not only upon our own heads, but those of our unfortunate teachers.

This was the institution in which I grew up, and in which my tastes, habits and thinking, and in short, my whole character, was formed for all after life. Our studies, as at that time was general in the city, and still is, in many parts of it, were conducted one half of the day in French, and during the remainder in English; and as is not the case in any other city, the two languages are so equally used, they were spoken by us with as much ease as if they had been

Page 26

both, which they really were, our mother tongues; but beyond this our education was sadly deficient. So that, at the end of my four years' course, I could quote the first five lines of the Greek poem devoted to Achilles' wrath; I knew that Æneas had carried on a classical flirtation, and terminated it with something like modern rascality; and that the sum of the angles A. B. C. plus D. E. F. were, for some forgotten reason, equal to another description of angles. But beyond this my education was a failure. The rest of my ideas were mostly derived from Dumas, Sue, Balzac, and other of the yellow colored novels, French and English, still less fitted to give us practical ideas of life.

Thus having to go through the forms and drudgery of school life, without ever making any progress, I chafed incessantly, and sighed for the moment of freedom. I often attempted to pursuade my uncle to relieve me from a life which was worse than useless. But, perhaps from imagining my education to be in good hands, because the tuition was extremely high, or from some more selfish motive, upon this point he remained inexorable. The pleasure of my company for a few days was a severe trial to a man of his tastes and habits, and the mere mention of my coming home for good would be sufficient to fill him with fury.

"Do anything you please except coming home to bore me; I won't hear of it, I tell you."

And these choleric exclamations of the moment betrayed his whole line of conduct regarding me. I was never denied money in profusion; my accounts were paid without examination; and, in general, I was allowed to do as I chose; but as to troubling his ease for a single moment with giving me sympathy, counsel, or example, for my improvement, the meanest scholar, that had any relations at all, was more fortunate than I. Not that my uncle was a very bad man, or well knew for how much subsequent unhappiness in my life he might be accountable. He was merely a doubting, distrustful cynic, who believed little in earthly good, and was not quite sure whether the success or failure of a young man's life was a matter of much consequence. But to return. Having nothing to do at school, and living in a large city, with plenty of pocket money, we

Page 27

at length--that is, myself and companions--begin to acquire dissolute habits, almost from necessity. I ceased sleeping at the college altogether; became a frequent visitor at the kino rooms, and religiously visited the Dutch beer gardens every Sunday afternoon. Luckily for me, this kind of life could not always continue. The time at length arrived at which even M. Baudoin felt a delicacy in charging me for lessons which I never attended, and having received a diploma in Latin, which I could not read, I now had the courage to present myself, with my trunks, before my uncle.

"He can't have the heart to drive me into any more establishments of learning, with such a pretty piece of sheepskin as this," I uneasily soliloquized, and the result showed that I was right.

Arriving in his presence, I found him engaged with a notary in some business; so earnestly, indeed, that he merely raised his eyes momentarily as I entered. I had leisure to observe him. His eye was less bright, his cheek thinner than when I had formerly parted with him, but his suspicious, sceptical look, remained the same.

For some moments after the man of business had departed, he still seemed absorbed in reflection; but at length raising his head, he glanced at me an enquiry which seemed to demand why I had come.

"My education at M. Badouin's college has been completed, uncle. There is nothing further for me to accomplish there. I have, therefore, returned to await your further pleasure."

"Have you learned anything?"

"A difficult question for me to answer. However, in the classics we have read"--

"Never mind the classics. You know nothing about them, of course--none of your name ever did. Not that I think it necessary; but have you acquired the usual accomplishments of young men who have, or suppose they will have, more money than need for the exercise of their brains?"

"I hope you will find that I have not altogether lost my time. In riding, music and dancing, I flatter myself I am somewhat au fait. My fencing master tells me I have a tolerable wrist; otherwise

Page 28

I can ring the bell an average number of times in the pistol gallery."

"Umph!" Dancing and fighting--to shine in a lady's bower, and kill your rival--I believe this is all we ever learn. You have to commence life with the advantages of those who have gone before. You certainly cannot complain of your education. So accomplished a paragon deserves to shine. To show you I am interested in your success, you may have my ticket to the -- ball, of which I am a subscriber. Stay; to-day is Mardi-gras--it will take place to-night. There is nothing else to be said, I presume."

"If you would," I ventured to say, although I clearly saw that he wished to finish the interview, "give me a little sympathy uncle, and a little affection, it would make me much happier. Will you not allow me to be to you a son, and interest myself in ministering to your comforts?"

"Par dieu, I am not so old as you would have me believe; and supposing I was, François can do that better than you. Be satisfied, I will die in good time, and you will be master then. Now go; it is time for me to dress for dinner."

And so, having nothing else to do, I sallied into the streets, and with the happy temperament of youth, had soon forgotten that I had not one single friend to advise me as to the temptations by which I was surrounded.

Page 29

CHAPTER VII.

The day known in New Orleans as Mardi gras, to which my uncle had alluded, whatever may be its religious use or meaning, was at that time well calculated to dispel any momentary depression of spirits. Singular figures of both sexes, in every variety of costume, on horseback and on foot, were passing to and fro, and perpetrating harmless jokes on the many passengers. But even in this city, with its substratum of French and Spanish population and traditions, masquerading, in broad daylight, accords ill with the genius of our people, and is mostly confined to the wilder and ruder spirits of both sexes.

It is only when the garish light of day has fled from the heavens, that the true spirit of the carnival begins to be felt and seen. Long processions, representing knights of the olden time, troubadours, gipsies mingled with characters of more modern origin, once more revisit the earth. The denisens of Olympus, and the mythic characters of the golden age are slowly bourne along in their antique cars, and pleasingly intermingle the past with the present. Later in the evening they disappear at the entrance of the theatres, opera houses, and saloons, which have been fitted up for dancing; and would you enter fully into the spirit of the hour, it is thither you must follow them.

In spite of all that is said about the commonplace and trivial character of balls, and, indeed, of what you yourself know them in after life to be, what youth, of either sex, in the full possession of health and happiness, can enter within their limits for the first time, without a sensation of delirium and intoxication similar to that he imagines of the blest in Heaven. The numerous lights, the reflecting mirrors, the voluptuous sensations produced by the music, and lastly the gay and animated throng which are everywhere in motion--all excite that exhilaration and lightness of heart which is born in the soul, but once or twice in a life time.

This I now found to be my first sensation on entering; my second was that of infinite sadness, produced by feeling myself a stranger in a

Page 30

self-occupied crowd of seeing amazons, peasants, princesses, vivandiers, and beauties in every variety of costly dress, all hurrying and pressing in the mad delirium of the dance, without for one moment being affected by my happiness or misery. I had retired in this mood to one of the boxes, too bashful and little accustomed to scenes of this sort to be ready in securing partners, and was looking with an envious eye upon those who were more fortunate. A light touch upon the shoulder at this moment caused me to turn, and in doing this, I now became aware of the presence of a zephyr-like figure standing hitherto unheeded at my side. It was that of a beautiful fairy, in half mask, clad in a gossamer dress, which shaded rather than concealed her form and rounded limbs. Upon her shoulders she bore golden butterfly wings. So irresistibly did her attitude and air impress me as she stood softly leaning forward to whisper in my ear, that for a moment I thought her some supernatural exhalation.

"Shall I call you my good Genius, or are you only a very pretty mortal?" I said to her.

"I am Psyche, or the Soul, unlettered swain; do you not see my wings? I am weary with the world below, and have flown to the heaven of this dress circle. But why do you not dance?"

"It was a presentiment that you were coming soon to be my partner; for you are going to dance with me, are you not?"

"Hum! Goddesses do not dance with every rash youth presumptuous enough to seek their hand. Are you quite sure you dance well?"

"You shall see--it will not be very difficult with a goddess for a partner."

"And are your gloves quite clean? I do not choose to have imprinted upon the back of my dress the cognizance of a hand in addition to my other ornaments."

"See--I put on a fresh pair in honor of your divinity."

"Let us commence, then; but be careful of my wings."

Here she placed her cheek against my shoulder, the band struck up a lively waltz, and we were soon jostling and forcing four way

Page 31

through the immense crowd, in sweet unison with the music, and as happy as though I really held a goddess in my arms.

"You do not dance so bad! Only you must not hold me too close."

"I was fearful that the crowd would tear you from me; and you dance so light I was apprehensive that my Psyche might fly away."

"There! your compliment has caused you to lose the step. You shall not talk until the music has ceased. And you must always let me go forward, or I shall tread upon the skirt of my dress and fall."

"As you will; I shall improve under your instruction; but are you not Terpsichore, and not Psyche, or, indeed, some maitresse de danse?"

"Naughty boy! You shall not dance with me any more! However, the music has ceased already. Give me your arm, and carry me where there is purer air. Now tell me who you are."

"A marvelously proper question! Must I tell my name to every one who chooses to challenge it? If you are really a goddess you know already."

"And so, perhaps, I do; and you would not now have the honor of having me leaning upon your arm, did not I, as well as my duenna, who you see yonder watching us, know full well who you are."

"You have not yet shown any remarkable knowledge of my history. Give me some proofs of your power."

"Well, Mr. Oscar, you were not so gay a cavalier when first I knew you. Then you were only a little melancholy priest; but even before this, when you ran off from a party and deserted your partner, I knew you."

"Well, is that all?"

"Then you used to wait for your little lady-love at the door of her school, and dance together wherever you happened to find an itinerant hand organ. One time you were dancing to the dead-march of some funeral procession; but that, you know, was bad for lovers, and so you have never seen her since."

"True, only in part; for I see her now. In telling mine, you have also recounted your own history. You are the little Clara that

Page 32

brought me some bon-bons; and it was you who, coming on the eve of some holy day to the church with a basket of flowers, fell from a step into Oscar's arms. But what was your last name? Did you ever have any other besides Clara?"

"None--at least, you must know me by none other."

"But you certainly will give me some clue? You will allow me to come to see you, will you not?"

"Impossible. We must say good bye when we part to night; besides, I am just escaped from a convent's walls, and am now on my way home, and so we could not meet any more if we would. But yonder my friends are beckoning to me. I must leave you now. When you see me again it will be in a different disguise--plain white domino and black mask. Do you think you will know me?"

"Impossible to be mistaken--that is, if you are bent on leaving."

"Then au revoir." And she disappeared among the crowd.

The rooms now had but little charms for me. I could only promenade from one part to the other, and curse the delay that separated us. At length, after having vainly sought for twenty times the form I missed in every quarter, I saw a mask issue from the dressing room, which answered to the given description.

"I have grown dreadfully impatient at not seeing you."

"But you do not know me," was the reply from a disguised voice.

"Do not torment me, thus; I have suffered enough already from waiting. You cannot expect me to be deceived in so short a time as to your figure, gait, color of your eyes; and lastly--disguise it as you will--your voice."

"Well, then, since you have penetrated my disguise so easily, be it as you say. But you have separated me from my party, who have gone into the supper room without me. What shall I do?"

"Do! why you will go in with me, of course. We will quietly sup together, and you will soon forget your loss in a glass of rose champagne. (Here waiter, your best supper.) Now you will have to remove your mask," I said, as we entered the room and sat down to the table.

"No, it has springs, I can eat very well as I am."

Page 33

I felt so disappointed that I did not have the heart to say any more until the supper was ended.

As I paid the waiter, and rose with my inconnue to leave, she suddenly discovered her party.

"Mad'moiselle, one word more; I fear I shall not have another opportunity to speak."

"That is very possible, as my friends are only waiting me to depart."

"This fact emboldens me. Will you not give me your name and address?"

"No! decidedly no!"

"Then, for pity! one glance at the lovely face which lies hidden under your mask. If you knew what happiness it would give me, you would not deny me so slight a boon."

"True, it costs little, and you have invited me to a fine supper; would it make you very happy," she said, with something of a malicious air.

"Undoubtedly," I replied, with ill-suppressed eagerness.

"Be happy, then." Here she removed her mask.

If the sight that met Imogene's eyes had now confronted mine, it would not have been seen with more horror. Instead of gratified pleasure, I startled back with an exclamation of bitter rage and disappointment. However, the face I now saw before me was merely that of an elderly lady, whose visage was puckered with wrinkles, and of the color of scorched parchment. To complete my chagrin, I now saw the lady whom I had so eagerly sought, still costumed as Psyche, descending the stairs, and evidently greatly enjoying my discomfiture. But the stairs were blocked up with ladies getting ready to depart, and before I could extricate myself, I had the additional mortification of seeing her enter a carriage, wave me a coquettish salute, and drive rapidly away.

Page 34

CHAPTER VIII.

My pursuits for some months succeeding this adventure, though nominally that of reading law, were as frivolous as one could well imagine. The state of mind to which I had arrived, viz: that of a young man who is struck with a pretty face, for some unaccountable reason to every one except himself, is of all others the most absurdly miserable, if for no other reason than that it unfits him for any serious occupation. Had I been an employee, I should have quarreled with my employer, and lost my situation. Had I known how, I would have sought relief in writing poetry. As it was, I became a constant attendant at soireés and assemblies, in the hopes of again meeting my inconnue. My manner of conducting myself there was to lounge around the doors, scowl at every one who passed, and to fancy myself generally miserable. I frequented churches, rode constantly in every city omnibus, visited the various places of amusement, and promenaded Canal at the hour when the crowd was the greatest. These resources failing, I took to wearing startling colors and dressing in the ruffianly style, to the intense horror of my uncle, who would fly into a tremendous passion as often as he saw me, and indignantly order me to take the obnoxious garments off. In short, my many gaucheries wearied and disgusted him, and he sighed for an opportunity of getting rid of me.

One day I was dining with him and his friends,--an august coterie, of whom I stood not a little in dread and from whom I was wont to escape as quickly as possible.

Soup being brought on the table, I had well nigh finished eating mine before the rest of the party had peppered, salted and seasoned theirs to the conventional pitch.

"Do you find the soup to your taste?" inquired one of the party, as he emptied the contents of a cruet into his basin.

"Very good--very good, indeed," I replied, well pleased to have an opportunity of accounting in some manner for my haste.

Page 35

"Ah! delighted to hear you say so; our cook is not generally so fortunate in his soups."

My uncle having now, with much preparation, arranged the seasoning of his dish according to his rules, conveyed a spoonful of the liquid in question to his lips. Uttering a fierce oath, the spoon fell from his nerveless hand, and this movement was followed by similar gestures of condemnation on the part of his friends. The waiter was summoned and abused as proxy for the cook, and the conversation passed to another theme.

"This business of eating, at best, is a disgusting affair," said one of the party sententiously.

"Low, doubtless, but also dangerous," said my uncle; "that which constitutes its only noble quality. There are other risks to run in life besides those incurred by charging batteries. If Damocles had a sword suspended over his table, it was placed there by his cook. Do you remember L'Harp? His wife would never have left him if his friends could have persuaded him to abandon his diet of hard boiled eggs. And Duvall! No wonder a man that eats fried steaks and bacon should die on the gallows."

How many more instances my uncle might not have quoted upon the subject of his favorite theme there is no telling, had I not at this moment upset the sauce-boat in his lap. He sprang up from his seat with a wrathful shout.

"Grand Dieu! You will yet be the death of me! I have ate at a thousand dinner tables without such an accident ever before happening. The world is wide enough for both of us--decidedly we must part. Never again put your legs under the same mahogany with mine!"

I made an angry protest against thus being spoken to as a child, and left the table. That day I formed my resolution. I would call upon my uncle once more upon business, and then renounce city dissipations, of which I was now heartily weary.

"I have arrived at some resolutions," said I, as I called upon him the following morning, "with which it would, perhaps, be best that I should acquaint you at once. I have now attained my majority,

Page 36

and been admitted to the bar. I wish to go in person and administer the estate left by my father. My time otherwise I will occupy with my profession."

"Be it as you wish, young man. You have only to communicate with my lawyer." And so our last interview terminated.

It did not take me many days to make these arrangements, and with no regrets, except for the precious time I had wasted, I shook off the dust of my feet against my native city, and braced myself for another début into life.

Page 37

CHAPTER IX.

My road led through interminable pine forests, through which the winds were dismally sighing, or through long lanes, which ran between zig-zag fences. This dreary prospect did not fill me with any flattering anticipations, but I was utterly unprepared for the dreariness and desolation of the miserable collection of houses, which I had determined was henceforth to be my home. As I drove through its streets, up to its principal, and indeed only hotel, I found, that I might have as soon expected to see, any of the ordinary signs of animation, or of life in the Haunted House, as described by Hood, as in this dreadful place.

By amusement was understood drinking in a bar-room, whose "properties" were, a decanter, a half dozen broken tumblers, and as many spoons. The more serious business of the inhabitants was fighting, and playing at the game of Brag, while reclining upon the grass in the public square; and so fascinating was it, that its participants never thought to look up from their occupation, excepting to inquire "who was killed?" in the various fights which were meanwhile transpiring. At night they would sit in one of the few stores of the village, around a fire of inflammable pine, and recite and listen to old stories of blood and murder, which had occurred in the place, and as the knots, with which the flames were fed, would burn with every degree of heat, in the space of a few minutes, our circle would widen and contract, from immediately around the fire place, to the remotest parts of the room. One might have thought to have seen us constantly moving our chairs as we listened to these recitals of all thehorrid events which had occurred in the neighborhood for the past twenty years, that we were going through some kind of incantation, or performing with our seats some complicated crescent dance.

I was standing in a knot of villagers, a few days after my arrival, when I was beckoned apart from the crowd, by a man who had been pointed out to me as the ruling spirit of the place. My first idea was, that my professional services were needed; my second, that

Page 38

I would be expected to fight. His pants were adorned with a sort of military stripe, his blue neckerchief was tied in a loose sailor's knot, and a jockey cap covered a bushy head of hair. Large rings, a flashy breastpin and chain, and a devil-may-care air generally, made up what was otherwise lacking.

"Have you brought your faro-bank tools along," he commenced, regarding at the same time a plush velvet vest, in which I was then arrayed, very attentively. "You hav'nt?" (in answer to a negative nod,) "then it does'nt signify; I want you about something else just now. You have your fiddle with you, at any rate."

I explained to him what my profession was, and was about to interpose some plea in reference to my musical attainments, when he interrupted me.

"Oh, d--n it, you need'nt tell me, you know; I've seen your fiddle case myself, and old Sprawles, your tavern-keeper, says he has heard you play. But squire, the point is this; we are trying to get up some fun and devilment out in the country, and I want to take you along. I think you'll do. So if you say so, I'll harness up my team, and we'll take an early start. And by the way," he added, without waiting for my assent--"if you happen to have another vest in that style, I would like to run it myself."

I found both propositions reasonable, and we were soon on our way, behind what Hawkins, my new friend, called a "slappin' team of cattle."

On our arrival at the place for which we had started, we found most of the guests outside of the house, or lounging around the doors. The building itself was of rude construction, the ground floor being of logs; it having been used in earlier times as a place of protection against the Indians. Within was a quilting frame, around which were seated, and busily plying their needles, the girls of the surrounding country. There had been as yet, little or no conversation, or any sign that this was a festive gathering; and the parties might have been engaged upon the cerements of the dead, for aught that appeared in their manner.

A few of the bolder spirits displayed their gallantry by snuffing the candles, and as often by oversetting them, or putting them out,

Page 39

and altogether it was evident that the time for the expected fun had not yet arrived.

But the appearance of Hawkins seemed to be regarded as the looked for signal. The men took immense drinks behind the house, while the quilt was raised to the ceiling by the fairer portion of the guests. Sam and myself entered arm in arm; the crowd followed at our heels, and the festivities were now fairly begun. First there were the well-known country games, which have held their place from time immemorial, and which were pleasantly enlivened by the squeezing of hands, and the kissing of pretty partners; then others of a musical character, in which gentlemen and ladies would form in double file, and march from one end of the house to the other--Sam leading the way, in an immense shirt collar, and roaring out songs, in which the rest joined--such as Barbara Allen, the Blacksmith's daughter, etc., etc. One of them was descriptive of the farmer's cares, and run in this wise:

"'Tis thus the farmer sows his ground,

He folds his arms and looks around;

He wheels around and views the sight,

And stamps the ground with much delight."

The folding of the farmer's arms, stamping of the ground, and other gestures described in the song were gone through in pantomine by the party with great spirit.

When all of these resources were exhausted, there having been many drinks taken in the meanwhile, Hawkins delighted the assembled guests by informing them that the young squire, meaning myself, was no bad hand with the fiddle, and that if such was their wish, they could now have plenty of dancing.

The suggestion was readily responded to by a quick scuffle for partners. I was to kiss the prettiest girl present for my share of the amusement; and my scruples and embarrassment having been in this way overruled, a commanding position was assigned me, on the top of a table. And so matters having been arranged to every body's satisfaction, the old house resounded for the rest of the evening

Page 40

with the heavy tramp of the dancers, and the unrestrained mirth of every one.

I said the satisfaction of every one, but there was one exception. A sallow, black-haired youth, had seen fit to conceive an unjust jealousy of me from the preference I had given to his sweet-heart, and occupied himself with haughtily regarding me from conspicuous places in the apartment. I did not pay any attention to the circumstance at the time, but I afterwards had cause to remember it.

The time at length arrived, when those who were sober enough, thought it prudent to break up, and the ladies had retired for bonnets and shawls. At this point Hawkins whispered to me, "we had better be gittin', too, squire;" but the advice came a moment too late. A cry was raised for a parting stag-dance; the door was fastened, and I was soon playing, nolens volens, "Natchez under the Hill," as fast as my fingers and bow would let me.

But my friend's presentiment, that the crowd, always quarrelsome and ready for a fight, had imbibed too freely to be left alone without some restraining influence, now proved true. Faster and faster moved the dancers as the excitement of the hour grew upon them; each one jostled rudely against his neighbor; and catch-words and compliments began to be bandied about, of anything but a complimentary nature, or pacifying tendency. At this moment the lights were accidently or designedly put out; my table, upon which I had been sitting as a throne, knocked over, and with such cries from many voices as "I'm the bull of the woods," the fray commenced in good earnest. Pistols were drawn, knives freely used, and articles of furniture in general circulation.

From this scene, in which I began to regard myself de trop, I was anxious to escape, and after some effort, succeeded in gaining an open window. But I was not to be let off so easily. Just as I was in the act of making my exit, a hand was laid upon my throat, and I could hear the quick cocking of a pistol. There was a fierce struggle for a moment, and out we both went, my unknown assailant and myself, through the window. As we fell heavily to the ground, I heard the discharge of the pistol, which my adversary must have

Page 41

held in his hand; but for some moments I was so stunned with my fall I could not tell which of us was wounded.

"No time to lose, partner," I at length heard Hawkins whispering above me, who, it seemed, had followed pretty closely on our heels. "You have killed your man, and you will soon have all of his friends and relations upon you."

"He was not killed by my act--it was his own fault, if any body's."

"Yours or his own, you excited his rage about his sweet-heart, and he's as dead as a mackerel now. But come, you must git up, and git from this section until the thing blows over."

I thought my companion's advice too good to hesitate about accepting it. I bethought me that I had engaged with the legal gentleman, with whom I had read law, to obtain in writing, in the requisite form, the depositions of a certain aged witness, who was then living in a portion of Louisiana, known as "Up the Coast." I therefore concluded that the most favorable time I would have of attending to this business would be the present.

Page 42

CHAPTER X.

The next morning found me jolting along my way, in an old travel-stained coach, walking by its side when the roads were rough, and for which I did not much care; but not unfrequently having to carry a rail on my shoulders, to pry it out when bogged in the mud. Besides these little drawbacks, it was pouring down rain during the whole journey; the wind would sigh dismally through the forests, and everything seemed to impress me with a conviction that my journey boded me no good. When we stopped for refreshments, we encountered nothing but the most God-forsaken wayside taverns, where I was uniformly addressed as "stranger," by the landlords, and where, when forced to remain at night, the shutters would keep beating against my window-panes, dismal accompaniments to the raging storm, or vague warnings not to go farther.

The ennui of traveling was at length relieved, by the presence of a companion, though not much at least, for a day or so. His chief occupation for that period of time, was to project his head out of the coach window, and examine the sky; and as if, too much for his spirits to bear up under without some support, he would follow up these examinations, by taking a pull at a black flask, and inviting me to do likewise. But finding that this course did not affect any change, he gradually became more communicative, and freely imparted to me his circumstances.

First, his name was D'Armas, or De Armas, as he would sometimes pronounce it, to make sure of the prefix. He was of Spanish and French descent, (his ancestors having come over with Ponce de Leon, or De Soto, at least so he told me,) and from his accent, I imagined that he spoke the latter language much better than English. He had at one time held a commission in the United States service, but had resigned, and was now but recently returned from Paris. Indeed, I soon found that he affected the Parisian or cosmopolitan style, and never alluded to that city without a sigh.

"We can't get things here as we ought to have them. There is

Page 43

every variety of flesh, fish and fruit in the country, and no one that knows how to cook. But a good cook requires a very rare order of genius. I have a growing presentiment that I shall die of starvation."

"But it seemed to me when we stopped last to change horses, and fried rashers of bacon upon skewers, that you eat your share with as good a stomach as the rest of us."