Correspondence Between Governor Brown and the Secretary of War,

Upon the Right of the Georgia Volunteers, in Confederate Service,

to Elect Their Own Officers:

Electronic Edition.

Georgia. Governor (1857-1865 : Brown)

Funding from the Institute of Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Jason Befort

Images scanned by

Jason Befort

Text encoded by

Elizabeth S. Wright and Jill Kuhn

First edition, 2000

ca. 50K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

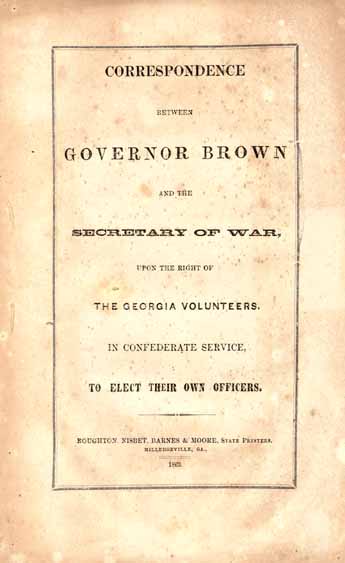

(title page) Correspondence Between Governor Brown and the Secretary of War, Upon the Right of The Georgia Volunteers, In Confederate Service, To Elect Their Own Officers.

16 p.

Milledgeville, GA.

Boughton, Nisbet, Barnes & Moore, State Printers.

1863.

Call number 1564 Conf. (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

This electronic edition has been created by Optical

Character Recognition (OCR). OCR-ed text has been compared against the

original document and corrected. The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings,

21st edition, 1998Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Confederate States of America. Army -- Officers.

- Confederate States of America. Army -- Officers -- Selection and appointment.

- Confederate States of America. War Dept.

- Georgia -- Militia.

- Confederate States of America. Army. Georgia Infantry Regiment, 51st.

- Georgia -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865.

Revision History:

- 2000-07-19,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-07-12,

Jill Kuhn

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-07-11,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-07-04,

Jason Befort

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

CORRESPONDENCE

BETWEEN

GOVERNOR BROWN

AND THE

SECRETARY OF WAR,

UPON THE RIGHT OF

THE GEORGIA VOLUNTEERS,

IN CONFEDERATE SERVICE,

TO ELECT THEIR OWN OFFICERS.

BOUGHTON, NISBET, BARNES & MOORE, STATE PRINTERS.

MILLEDGEVILLE, GA.,

1863.

Page 3

CORRESPONDENCE.

EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT,

Milledgeville, Georgia, May 30th, 1863.

Hon. James A. Seddon, Secretary of War:

DEAR SIR:--Complaint is made to me that the gallant 51st Regiment of Georgia volunteers, which covered itself with so much glory in the late battle of Chancellorville, and whose gallant Colonel fell mortally wounded and died of his wounds next day, has been denied the right to elect a Colonel to fill the vacancy of the lamented Col. Slaughter, and that the General in command has appointed a Colonel by promotion.

This is one of the Regiments sent into service by me, under the requisition made upon me in February, 1862, for twelve Regiments, and I am at a loss to know why the General in command should have refused to allow the Regiment to exercise its plain constitutional right of election. I have understood this question to be settled in favor of the right of all State Regiments, organized as the 51st was, to elect their own officers to fill all vacancies which have or may occur. Indeed, the right of election is too plain to be questioned. I am daily commissioning the officers elected by other Georgia Regiments in like cases, to fill vacancies, and I am at a loss to understand why the right should be withheld from the 51st, which is allowed to others, and to which all are unquestionably entitled.

I have advised the Regiment that it is their right to elect, and have directed them to hold an election and send the returns to the Adjunct & Inspector General of this State, when I will order a commission to issue to the person elected. I have stated to them, that this right is allowed to others, and that they are entitled to it, and that I doubt not, you will recognize the person elected as the Colonel of the Regiment.

I trust you will at once instruct the General commanding to permit the Regiment to exercise its right of election, and recognize their officers when elected and commissioned by the proper authority in this State.

I will be greatly obliged by an early reply.

I am, very respectfully,

Your ob't servant,

JOSEPH E. BROWN.

Page 4

CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA,

War Department,

Richmond, Va., June 26th, 1863.

To Gov. J. E. Brown, Milledgeville, Ga.:

SIR:--Your communication of the 30th May last has been received, and the consideration given to it required as well by the serious consequences of the claim of a right to fill the vacancy occasioned by the death of the lamented Col. Slaughter, of the 51st Ga. Reg't, by election, as of the earnestness and confidence with which the claim is presented.

It appears from the muster rolls filed in the office of the Adjutant & Inspector General, that the 51st Ga. Reg't was mustered directly into the Confederate service on the 4th of March, 1862, for three years or the war.

The Regiment was raised under the act of January 23d, 1862, which authorized the President to call upon the several States for troops to serve for three years or the war, and a circular on the subject from the War Department of Feb. 2d, 1862, was addressed to the several Governors.

By the 10th section of the act of April 16th, 1862, commonly known as the conscription act, it is provided that all vacancies shall be filled by the President from the company, battalion, squadron, or regiment in which such vacancy shall occur, by promotion according to seniority, &c., &c. This provision was supposed to apply only to the troops referred to in that act.

But, as if intending to put the question at rest on this point, Congress, five days after, to-wit: on the 21st April, 1862, passed a general act, providing that all vacancies shall be filled by the President, &c., &c., by promotion according to seniority, &c. It seems to me, therefore, that in accordance with the last act, all vacancies in volunteer organizations are to be filled by promotion according to seniority, &c., and that the vacancy referred to in the 51st Ga. Reg't should be so filled, and not by election.

The laws and regulations provide for a stringent investigation as to the fitness of an officer for the promotion to which he would be entitled by seniority, if worthy; and, as you state, that such promotion has been made of the officer entitled by seniority, it is presumed that he is worthy to fill the place.

The act of the General announcing the promotion is in accordance with the laws of Congress, with the regulations and uniform usage of the service, and is approved by the Department.

It is to be regretted that this difference of opinion should have existed, and that the expression of your views should have been given such direction as may possibly excite some dissatisfaction among the officers of that gallant Regiment[.]

Page 5

It is hoped that upon a reconsideration, you will concur with the views herein expressed.

With esteem, respectfully yours,

JAMES A. SEDDON,

Secretary of War.

MARIETTA, GA., July 10th, 1863.

Hon. James A. Seddon, Secretary of War:

DEAR SIR:--I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of 26th June last, in reply to my letter claiming for the gallant 51st Georgia Regiment the right to elect an officer to fill the vacancy of the late Colonel Slaughter, who was killed in battle, and whose vacancy has been filled by the General in command, by promotion, denying to the regiment the right of election. This action I consider in palpable violation of the plain constitutional rights of the Regiment, and while I thank you for the courtesy of your reply, I must express both my surprise and mortification at your denial of the right of election to this Regiment and others which entered these service as it did; and your announcement that the conduct of the General in refusing to permit the Regiment to exercise this right, and assigning to it a commander by promotion, without regard to the wishes of the troops, "is approved by the Department."

You predicate this decision upon the act of Congress known as the Conscription Act and a subsequent act which provides that "all vacancies shall be filled by the President." I predicate my objection to the decision upon the Constitution of the Confederate States, which is of higher authority than any act of Congress, and hold that the acts referred to by you, so far as they deny to the State of Georgia the right to fill this and all similar vacancies, are in conflict with the Constitution, and therefore void and of no binding force.

The 16th paragraph of the 8th section of the 1st article of the Constitution of the Confederate States declares, that Congress shall have power "to provide for organizing, arming and disciplining the militia, and for governing such part of them as may be employed in the service of the Confederate States, RESERVING TO THE STATES RESPECTIVELY THE APPOINTMENT OF OFFICERS, and the authority of training the militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress."

By this paragraph of the Constitution, the State of Georgia, in plain language, reserved to herself the appointment of the officers to command any part of her militia, when employed in the service of the Confederate States. And by her own Constitution and laws, she has provided that such

Page 6

appointment shall be made by election of those to be commanded by these officers, and commission from the Governor, and that vacancies shall be filled in the same manner.

By the militia, I understand the Constitution to mean the whole arms-bearing population of the State, who are not enlisted in the regular armies of the Confederacy. I am aware that writers upon English law define the militia to be an organized body of troops, &c.

That the framers of the Constitution did not intend to use the term in this sense, is evident from the fact, that they speak of the militia as in existence at the time they are making the Constitution, and give Congress the power, not to make a new militia, nor to organize that already in in existence, but to provide for organizing the militia. In other words, to provide for forming into military organizations the arms-bearing people of the respective States. Had the Constitution given Congress the power to organize the militia without the qualifying words, it would have had the power to appoint the officers to command them, or to authorize the President to appoint them, as they cannot be organized without officers. The language is, however, very guarded. Power is given to Congress to provide for organizing that which was then in existence, without effective organization, the militia or arms-bearing people of the States. When Congress has provided for the organization, and the States have organized the militia, Congress may authorize the President to employ them, or a part of them in the service of the Confederate States, but in that case the States expressly reserve to themselves the right to appoint the officers to command them, and Congress cannot, without usurpation, exercise that power, or confer it upon the President.

But suppose I adopt the definition of the term militia insisted upon by those who differ from me. The result is the same. In our correspondence upon the constitutionality of the Conscript Act the President says, "the term militia is a collective term, meaning a body of men organized." In February, 1862, the President made requisition upon me, under the act of Congress of the 23d of January, 1862, for twelve regiments of troops, to be employed in the service of the Confederate States. I proceeded under the laws in existence at the time to organize the regiments called for. The 51st Regiment was tendered as one of the twelve, and, with the other eleven and several additional regiments which offered their services all volunteers, was accepted by the President, as organized and officered by the State. This Regiment, when tendered, was therefore an organized body of men, taken indiscriminately from the arms-bearing people of the State, who tendered their services and were accepted by the President as a body of men organized by the State, or as militia, according to his own definition. The

Page 7

of the State to appoint the officers, which she does upon the election of those to be commanded, was distinctly recognized in the organization of the Regiment. If the State possessed this right then, how has she lost it since? If it is her right to appoint the officers when the Regiment organized, how does she lose the right when a vacancy is to be filled?

But the case does not rest here, undoubted as were the States' rights under the Constitution. Before this Regiment and others called for at the same time were formed, I wrote Mr. Benjamin, the Secretary of War, upon the question, that the reserved rights of the State and other troops might be distinctly recognized, to avoid my misunderstanding in future.

In his reply of 16th February, 1862, after the requisition had been made, and before the regiments were organized, Mr. Benjamin said, "I will add, that the officers of the regiments called for from the State under the recent act of Congress, are, in my opinion, to be commissioned by the Governor of Georgia, as they are State troops tendered to the Confederate Government."

This opinion of the Secretary of War was communicated to the troops, and they were assured by me, that they had the right to elect all the field and company officers by whom they were to be commanded, while employed in the service of the Confederate States. With this assurance from the Secretary of War and the Governor of this State, they volunteered and entered the service with the officers elected by them.

Aside from their constitutional right, here was a fair contract between them and the Government, under which they entered its service, and have nobly performed their part; and I deny that Congress possesses the power, by any subsequent act, to wrest from them this constitutional right, or that the Government, without a most unjustifiable breach of its plighted faith, can now deny to them the exercise of this right. I beg to be excused for the use of strong language which may appear to show too much zeal on my part in this cause.

By the act of the Secretary of War, I was made a party to this contract with the troops, and my action under it was ratified by the President when he accepted the troops organized under it with officers elected by them, and I feel in honor bound to exert all the energy and power I possess to prevent the injustice which is being done to these gallant, self-sacrificing men. If the right is still denied, it will be my duty to communicate the facts to the General Assembly of this State, when again convened, and to ask them to take such action in the premises as will secure justice to their injured fellow-citizens and constituents, and protect their plain constitutional rights.

Page 8

You say you regret that "the expression of my views should have been given such a direction as may probably excite some dissatisfaction among the officers of that gallant Regiment." Much as I may regret to excite the dissatisfaction of the officers who may be unwilling to submit their claims to preferment to a fair vote of those whom they aspire to command, I cannot be silent when the rights of the Regiment in the selection of its officers are no longer respected. But I cannot suppose that the dissatisfaction of any meritorious officer who treats his men humanely and has shown himself worthy to lead them in battle, will be excited, as such an officer has no reason to fear the decision of the gallant troops with whom he has been long associated, and who are well acquainted with his character and his capacity to command them, and protect their lives in battle. It can only be those officers whose chief claim to preferment rests upon their rank and the date of commissions acquired by them, when less known to the troops, whose dissatisfaction can be excited when the troops are informed that the Executive of their State claims that they shall be permitted to exercise what they believe to be their constitutional right of election, and what they and their officers know was guaranteed to them when they entered the service.

You say further, that "the act of the General in announcing the promotion, is in accordance with the laws of Congress, with the regulations and uniform usage of the service." I trust I have shown that the act of Congress, so far as it confers the right of appointment in this case upon the President, is a nulity, on account of its conflict with the Constitution, and it follows as a necessary consequence that any regulation of your Department carrying into execution that which is void, is also unauthoritative. In reference to the uniform usage of the service, I can only remark, that you labor under a very great mistake. I think it safe to say that a majority of the whole number of vacancies which have occurred in regiments in Confederate service from this State, which entered the service as did the 51st, under requisition from the President, have been filled by election and commission from the State. There has been therefore, no uniform usage in favor of your construction, but rather the contrary.

I am informed that soon after the passage of the conscription act, this question was raised in Colonel Benning's Regiment, General Toomb's Brigade, and was carried up regularly to the War Department for decision, and was decided in favor of the right of the State to appoint the officers to fill these vacancies, and against the right of the President to fill them by promotion. I am also informed, that a case involving this very principle, has been submitted to the Attorney General for his opinion, and that his opinion

Page 9

sustained the right of aypointment by the States, in regiments tendered and accepted under the requisition of the President upon the State for troops, under the act of Congress aforesaid. If I am mistaken in either of these points, I will thank you to inform me of the error, and what has been the decision of your predecessor, and of the Attorney General in cases similar to that now under discussion. Certain it is, within my own knowledge, that since the report of the decision above referred to, most of the Georgia regiments, organized as this was, have exercised the right of election, and I have commissioned the persons elected, and they now have command under their State commissions, and are recognized by the superior officers as entitled to their rank and command.

In conclusion, I must express my profound regret that you have felt it your duty to make a decision in this case, which, in my opinion, denies the State the exercise of a right expressly reserved by her in the constitution, and which does great injustice to the troops, not only because it deprives them of a legal right, which they consider of great importance to them, but because it violates the express guaranty of this right, under which they entered the service.

Amidst the weight of cares and responsibilities by which you are surrounded, I am induced to hope that your decision was predicated upon the act of Congress, without having given that mature reflection to the Constitutional question involved in the case, which its importance demands, and that you were not aware of the understanding between me and the Secretary of War, which I have mentioned above, and upon which the troops acted when they entered the service. I therefore most respectfully ask a reconsideration of this case, and trust I may soon have the pleasure to inform the gallant 51st regiment, and all others organized as it was, that their right of election, which I consider so clear, and they regard so valuable, is recognized and respected, by the Confederate Government.

I am, with great respect,

your obedient servant,

JOSEPH E. BROWN.

CONFEDERATE STATES OF AMERICA,

War Department,

Richmond, Va., July 25th, 1863.

His Excellency Jos. E. Brown,

Governor of Georgia:

Your letter of the 10th inst., has been received. The difference between yourself and this Department upon the subject of the right of the 51st Georgia Regiment, to elect

Page 10

their officers depends upon the fact whether this regiment composes a part of the militia of the State of Georgia. If the regiment be a portion of the militia "employed in the service of the Confederate States," the appointment of the officers is reserved to the State, otherwise, not. The company muster rolls of this regiment on file in the office of the Adjutant and Inspector General, are entitled "muster Roll of Capt.----Company in the 51st Regt. of Georgia vols., commanded by Col. Wm. M. Slaughter, called into the service of the Confederate States in the Provisional army, under the provisions of the act of Congress by Gov. Jos. E. Brown, from the 4th March, 1862, (date of the muster) for the term of three years, unless sooner discharged," and the muster corresponds with this title. This shows that this Regt. was composed of volunteers who were enlisted as a part of the Provisional army of the Confederacy, under the supervision of the Governor of Georgia.

The legislation of the Confederate States will very clearly exhibit that troops of this description have not been regarded as belonging to the militia. By the act of Feb. 28th, 1861, to raise Provisional forces for the Confederate States of America, the Congress enacted "that to enable the government of the Confederate States to maintain its jurisdiction over all questions of peace and war, and to provide for the public defence, the President be, and he is hereby authorized and directed to assume control of all military operations in every State having reference to, or connection with questions between said States, or any of them and powers foreign to them." The third section of the act is "that the President be authorized to receive into the service of the government such forces now in the service of said States as may be tendered, or who may volunteer by consent of their State in such numbers as he may require, &c., &c., &c.

The 4th section is, that such forces may be received with their officers by companies or regiments, and when so received shall form a part of the Provisional army of the Confederate States, according to the terms of their enlistment; and the President shall appoint, by and with the consent of Congress, such general officer or officers for said forces as may be necessary for the service. The 5th section provides "that said forces when received into the service of this government, shall have the same pay and allowances as may be provided by law for volunteers entering the service, or for the army (regular) of the Confederate States, and shall be subject to the same rules and government.

Your Excellency must perceive that the 51st Georgia regiment stands upon exactly the same footing as the troops tendered by the States, or volunteering under this act, and that this act contains not the slightest intimation that the troops received under it were received as State militia.

Page 11

There is a direct provision that a portion of the officers shall be appointed by the President.

The act of Congress of the 6th March, 1861, authorizes the President to employ the militia, military and naval forces of the Confederate States, and to ask for and accept the services of any number of volunteers, not to exceed 100,000, &c., &c. The 5th section of that act permit the President to accept the services of volunteers in companies, squadrons, Battalions and regiments, whose officers shall be appointed in the manner prescribed by law in the several States, to which they shall respectively belong. But when inspected, mustered, and received into the service of the Confederate States, said troops shall be regarded in all respects as a part of the army of the said Confederate States, according to their respective enlistments.

The President was authorized to organize the companies into superior organizations at his discretion, and to appoint Brigade and Division officers. It was supposed that these volunteers would be raised through the different States, for by the act of 11th May 1861, he was authorized to receive volunteers directly without the formality and delay of a call upon the States. In this act there is a broad discrimination made between the volunteers and militia, and the terms of the act forbid the conclusion that the volunteers obtained through the instrumentalities of the States, were to be regarded as militia "employed in the service of the Confederate States." The act of the 23d January, 1862, under which the 51st Georgia Regt. was called into the service, has immediate relation to the act of March 6th, 1861. The object of the act was to obtain from the States the complement of the troops authorized by the act of March 1861, by the apportionment among them and requisition upon their public authorities. The conditions upon which the troops were to enter the service were prescribed in that act. These were that "the said troops shall be regarded in all respects as a part of the army of the Confederate States, according to the terms of their respective enlistments," and as before shown, they were mustered into service conformably to these conditions. Forming as they did, a part of the army of the Confederate States, they became subject to the authority of Congress, who were authorized by the Constitution "to make rules for the government and regulations of the land and naval forces." Among the rules and regulations proper on the subject, are these relating to the selection and promotion of officers.

The act of Congress of March 6th, 1861, provided for the organization of the volunteer troops then called for by adopting the State regulations. The acts of the 4th session of the Provisional Congress (acts of 11th Dec., 22d Jan. and 27th January, 1862,) provided a rule of promotion in regard to a portion of those troops who were about to

Page 12

reinlist. The acts of the 16th April 1862 and 21st April 1862, made a rule applicable to the entire Provisional army. and this rule was repeated in the act of 13th Oct. 1862.

The Conscription acts of April and October have been the source from which the army has been recruited for more than fifteen months. It is probable that one half of those who now compose the 51st Ga. Regt. have come into it through the agency of these acts. This regiment and others accepted under the same conditions are regarded by this Department, since their acceptance by the Confederate States as a part of the Provisional army, and therefore to be recruited by the agency of the Confederate States. The rule of promotion prescribed by Congress, is one uniform in its operation, was adopted after the experience and observation of a year, and clearly embodies the judgment of Congress as the mode best calculated to insure the selection of competent officers.

It is unnecessary in this inquiry to undertake a definition of what the meaning of the word militia is. Neither the acts of Congress of the U. S., prior to the separation of the Confederate States, nor the acts of Congress of the Confederate States, have regarded as militia, volunteers who have come into the service of the Federal Union, or the Confederate service, to form a portion of the army upon which they rely for the common defence, and it would be difficult, in the opinion of this Department, to assign a meaning to the term that would properly embrace such troops.

The postscript to the letter of Mr. Benjamin of the 16th July, 1861, quoted by you, seems to refer to the original organization of the troops prior to their muster, and before their acceptance into the Confederate service, and the practice since their acceptance, if inconsistent with the opinion expressed in this letter, was probably a transient or casual toleration of an existing opinion, without a full consideration of the import of the legislation of the Congress of the Confederate States. After a careful consideration of that legislation I do not feel that I have any authority to dispense with its conditions, however, agreeable it might be to conform to the wishes of those who have maintained this opinion. Notwithstanding my deference to the views of your Excellency, I must confine my official actions to what I conceive the clear mandate of the laws.

With high esteem,

very respectfully, &c.,

(Signed.) JAMES A. SEDDON,

Sec'y of War.

Page 13

MARIETTA, August 21st, 1863.

Hon. James A. Seddon, Secretary of War:

DEAR SIR:--I have to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of 25th July, and to express my regret that I have been disappointed in what I considered a reasonable expectation, that upon a review of the question, you would permit the Georgia troops, to whom our correspondence refers, to exercise the right of electing their officers.

It does not seem to me that the constitutional objection which I make to the acts of Congress, which deny to the troops the right of election, and give to the president the power to appoint the officers to command them, is successfully met, by additional quotations from the acts of Congress, to show the intention. I have not called its intention into question, as I think it quite clear that it intended to confer the appointing power upon the President, but I have called in question its right, under the Constitution to do so. With all due deference, I cannot see, how the power of Congress to pass a Statute, can be established by quotations from a Statute, showing what Congress did enact, but not what its powers were.

I cannot admit that the distinction which you attempt to draw between volunteers and Militia, has any substantial foundation in law or fact, or that the length of time for which they are called into service, affects the question. It is very clear from the letter of the Constitution, that the militia of a State, may "be employed in the service of the Confederate States," in which case, Congress has power to provide for governing them, but even this power is made subject to the right of the State, to appoint the officers to command them. It matters not what Congress may choose to call the arms bearing people of the State, who are in fact her militia. When Congress asks the State, to permit the President to employ them in the service of the Confederate States, and he makes requisition for them, and the State organizes and tenders them, they may be called the armies of the Confederacy, or the provisional or regular army, or by any other name which Congress may adopt, but neither their existence, their identity nor their character is changed by the name. The arms bearing people of a State, are her militia, and when the President, under the authority of the act of Congress, makes requisition upon the Governor of a State for them, to repel an invasion, and they are tendered as organized and officered by the State, and accepted with their State officers and State organization, they are without regard to the term used by Congress to designate them, the militia of the State, "employed in the service of the Confederate States." Nor does the fact, that the State tenders them as drafted men, or as volunteers, or for a longer or shorter time, affect their character or their identity.

Page 14

Suppose a State is invaded, or there is a sudden insurrection, and the President, by virtue of an act of Congress, requires the Governor to call out the whole militia of a State for ten days, to repel the invasion, or suppress the insurrection, and every man in the State volunteers, does the fact that they are not drafted, but volunteer, destroy their character of militia, and convert the whole militia of the State, into an army of the Confederacy, and thereby give the President the power to appoint all the officers, and take from the State this right which she has carefully reserved in the Constitution? If not, how is the principle changed, in case the call is for one month, one year, or three years, instead of ten days? When thus tendered by the State, for what length of time must they "be employed in the service of the Confederate States," before they lose their character of militia of the State? and how long must they serve before the President may, without usurpation, deny to the State, her reserved right to appoint the officers, and assume to do it himself? Must it be for one month, one year, two years, three years, or what other period?

Under the act of Congress, the President called on me, as Governor of this State, for troops to serve for twelve months. They were furnished, and the States' right to appoint the officers to fill all vacancies was never questioned.

Other calls were made for troops to serve for three years. These were promptly responded to, and among others, the 51st Regiment was tendered and accepted, and the right of the State to appoint the officers, expressly admitted upon the record, with no qualification and no denial of her right to fill vacancies. Again, the President, has lately, through you, made requisitions upon me for 8,000 troops for six months, for home defence, to be used in case of emergency, and in repelling raids, &c. These men are expected to be, most of their time, at home, attending to their ordinary business of producing supplies, &c. But the act of Congress says, where they volunteer and are accepted, they shall form part of the provisional armies of the Confederate States. It will take nearly all the men remaining in the State, between 18 and 45, to fill this last requisition. Part of them will be volunteers, and part drafted men.

Now, if these six months men, twelve months men, and three years men, have been converted into armies of the Confederate States, in the sense in which the constitution uses the term, (I do not mean the sense in which Congress uses it,) and no part of them are militia, "employed in the service of the Confederate States," what has become of the militia of Georgia? Nearly the whole arms-bearing people of the State, between 18 and 45, are in the service of the Confederate States, the larger number of them organized by the State and tendered to, and accepted by the

Page 15

Confederate Government, with their officers appointed by the State, and you now deny that any part of the militia of Georgia are "employed in the service of the Confederate States," or that the State has the right to appoint a single officer to command them.

Again, I ask, how did Georgia get rid of her militia, and where are they? They are, in fact, all employed in the service of the Confederate States. She has expressly and carefully reserved the right, when they are thus employed, to appoint all the officers to command them. You do now, so employ them, but you deny her right to appoint even one of the lowest officers who is to command them, and you justify this by quoting from the acts of Congress to show, not the power to take from the State this plain constitutional right, but, that it was its intention to do it. I have never denied the intention, but I can never admit the power. I look upon it as a clear usurpation, which finds no jurisdiction, either in the Constitution, or in the plea of necessity, which is usually resorted to in such cases.

In my last letter, I referred to the opinions of your predecessors in office, and of the Attorney General, which are all reported to concur in the view I take of this question, and requested you to correct the error, if I had fallen into one, and to inform me what had been their ruling upon this point. As your reply passes this part of my letter in silence, I understand the fact to be admitted, that I am fully sustained in the view I take of the rights of the State, by the opinion of the Attorney General and the opinions and practice of the different distinguished gentlemen, who have successively filled the position you now occupy. I deeply regret that you have felt it your duty to overrule the opinions of such able and distinguished statesmen, as those just mentioned, upon a question involving a principle so vital to the rights and sovereignty of the States, when the denial of the rights of the States can only increase the power and patronage of the President, but cannot for the reasons given in my former letter, result in practical benefit to the public service. If your process of reasoning be correct, that the right of the States to appoint the officers no longer exists, when it can be shown by reference to the acts of Congress, that it intended to confer this power upon the President, then the Constitution is of no binding force, and Congress has power, by the use of a term, or the change of a name, to abrogate the most sacred rights of the States, and confer them all upon the President.

In reply to that part of your letter in which you state that the 51st Georgia Regiment, has been recruited under the conscript act, and that probably, one half of its present number, have been in that way added to it, I need only remark, that if it is the right of the State to appoint the officers

Page 16

to fill vacancies in the regiment, by commissioning those elected by the troops, the President, can certainly have no legal power to deprive the State of this right, or the men who originally formed the regiment, of the right of election, by adding conscripts to the regiment. If he chooses to put them in a regiment of volunteers, which has the right of election, he should not interfere with this right, but should permit all to vote.

But I need not trouble you with further remarks, as I perceive your decision is made up, doubtless after confering with the President, and it is determined that you shall enforce your construction. The President has the power in his own hands, and I am obliged for the present, reluctantly to acquiesce what I consider a great wrong, to thousands of gallant Georgia troops and a palpable infringment of the rights and the sovereignty of the State.

I will only add, that this letter is intended more as a protest against your decision, than as an effort to protract a discussion, which it seems, can be productive of no practical results.

I am, dear sir,

Very respectfully,

Your ob't servant,

JOSEPH E. BROWN.

Return to Menu Page for Correspondence... by Georgia. Governor (1857-1865: Brown)

Return to The Southern Homefront, 1861-1865 Home Page

Return to Documenting the American South Home Page