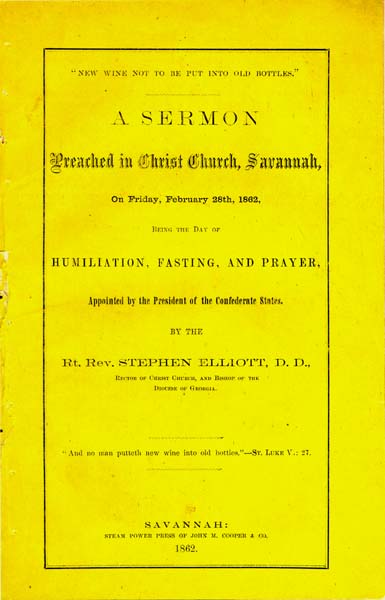

New Wine Not to be Put into Old Bottles:

A Sermon Preached in Christ Church, Savannah, on Friday, February 28th, 1862,

Being the Day of Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer,

Appointed by the President of the Confederate States:

Electronic Edition.

Elliott, Stephen, 1806-1866

Funding from the Institute of Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Yin Tang

Images scanned by

Yin Tang

Text encoded by

Jason Befort and Jill Kuhn

First edition, 2000

ca. 45K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Source Description:

(title page) "New Wine Not to be Put into Old Bottles." A Sermon Preached in Christ Church, Savannah, on Friday, February 28th, 1862, Being the Day of Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer, Appointed by the President of the Confederate States

Rt. Rev. Stephen Elliott, D.D.

18 p.

Savannah

Steam Power Press of John M. Cooper & Co.

1862.

Call number 4149 Conf. (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Languages Used:

- English

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- Fast-day sermons -- Georgia -- Savannah.

- Sermons, American -- Georgia -- Savannah.

- Episcopal Church -- Sermons.

- Confederate States of America -- Religion.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Sermons.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Religious aspects.

Revision History:

- 2000-05-01,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-01-14,

Jill Kuhn

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-01-06

Jason Befort

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-11-24,

Yin Tang

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

"NEW WINE NOT TO BE PUT INTO OLD BOTTLES."

A SERMON

PREACHED IN CHRIST CHURCH, SAVANNAH,

On Friday, February 28th, 1862,

BEING THE DAY OF

HUMILIATION, FASTING, AND PRAYER,

Appointed by the President of the Confederate States.

BY THE

Rt. Rev. STEPHEN ELLIOTT, D. D.,

RECTOR OF CHRIST CHURCH, AND BISHOP OF THE

DIOCESE OF GEORGIA.

"And no man putteth new wine into old bottles."--ST. LUKE V.: 27.

SAVANNAH:

STEAM POWER PRESS OF JOHN M. COOPER & CO.

1862.

Page 3

To the Clergy of the Diocese of Georgia.

The President of the Confederate States having issued his Proclamation appointing Friday, the 28th of February, instant, as a day of solemn humiliation before God, in view of His manifold mercies towards us as a nation and of our great unworthiness of them--

Now therefore, I, STEPHEN ELLIOTT, Bishop of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of Georgia, do direct the Clergy of the said Diocese to invite their congregations to assemble together in their respective places of worship, and to keep the Fast before the Lord in all humility of mind and spirit, and while deprecating the wrath of God for our past sins, to invoke His blessing upon the new Government which has been so successfully inaugurated.

Upon the occasion of this Fast, the Clergy will use the subjoined service:

- Morning Prayer as usual to the Psalter.

- Psalms for the day--the 13th, 56th and 94th.

- 1st Lesson--II Kings ch. 18, from v. 17, and ch. 19 to v. 8.

- 2d Lesson--I Peter, ch. 2 vv. 11--18.

Use the whole Litany, and immediately before the General Thanksgiving, introduced the Prayers following:

PRAYER.

O most mighty Lord God, who reignest over all the kingdoms of men; who hast power in Thy hand to cast down and to raise up, to save Thy servants and to rebuke their enemies, let Thine ears be now open unto our prayers and Thy merciful eyes upon our trouble and our danger. O Lord, do Thou judge our cause in righteousness and mercy, and wherein soever we have offended against Thee, or injured our neighbor, make us truly sensible of it and deeply penitent for it. We humbly confess that we are unworthy of the manifold goodness vouchsafed us in this struggle for our rights, yet we are bold, because of Thy long suffering, to pray for the continuance of it and to supplicate Thy blessing upon us and our arms. Cover the heads of our soldiers in the day of battle, and send Thy fear before them, that our enemies may flee at their presence. Establish us in the rights Thou has given us, in our Government and in our Laws, in our Religion, and in all our holy Ministries. The race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, but our trust is in the name of the Lord our God. Hear us, O Lord, for the glory of Thy name and for Thy truth's sake, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Page 4

PRAYER.

Almighty God, who rulest over all the nations of the earth and disposest of them according to Thy good pleasure, we yield Thee unfeigned thanks that Thou hast been pleased to bring these Confederate States in safety to the close of the first year of their political existence, and that Thou hast preserved Thy servant, the President of this Confederacy, in health of body and vigor of mind to the commencement of his administration as the Chief Magistrate of our now settled government. Let Thy wisdom be his guide, and let Thine arm strengthen him; let justice, truth and holiness, and all those virtues that adorn the Christian profession flourish in his days; direct all his counsels and endeavors to Thy glory and the welfare of these States; and give us grace to obey his government cheerfully and willingly for conscience sake, that neither our sinful passions nor our private interests may disappoint his cares for the public good; let his administration be prosperous and honorable, and crown him with immortality in the world to come through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Page 5

A Sermon.

ST. LUKE, CH. V., vv. 37-39.

"And no man putteth new wine into old bottles, else the new wine will burst the bottles and be spilled, and the bottles shall perish.

"But new wine must be put into new bottles, and both are preserved.

"No man also having drunk old wine straightway desireth new: for he saith, the old is better."

The meeting of Congress and the inauguration of a President under our permanent Constitution, have ushered us upon a new era in our national history, and in the wise judgment of our Chief Magistrate, afford a fitting opportunity for once more humbling ourselves before the mercy-seat, and invoking the blessing of the Christian's God upon our new Government and upon the conduct of our civil and military affairs. We are learning the sublime truth of our daily dependence upon God, and we are learning it, where only it can be learned, in the school of adversity and affliction. Happy nation! which frequently and hopefully bows itself in prayer and supplication at the throne of Grace, for it is at least an outward and visible sign that we hear the rod and who has appointed it!

At such a moment it is well for us to pause in the wild career of action and consider profoundly the great principles which must lie at the foundation of our national structure, ere we may feel assured that it is builded upon a rock. It is indeed, as Jeremy Taylor expresses it, meditating upon the outskirts of a camp, but that is better than not to meditate at all. Our whole future will depend upon the first years of our political existence, and we must weigh our position now, even amid the tumult and confusion of war, or let it depend upon chance or fortune. All nations which come into existence

Page 6

at this late period of the world must be born amid the storm of revolution, and must win their way to a place in history through the baptism of blood. And this, because no people would ever throw off a beneficent government, and an oppressive one will always strive to perpetuate its tyranny by arms and violence. If we wait, therefore, for peace, ere we ask counsel of God and wisdom from His throne, we shall permit the moulding process of our future to have been finished ere we examine the form and shape which it is likely to put on. Our new wine will have found its way into old bottles ere we shall have duly considered the folly of such a course, and our labor and suffering may have been in vain and for nought.

We look very superficially at the revolution through which we are passing, when we consider merely the immediate causes which have produced it, and go no further back in our analysis. To say that the movement which has brought into existence the new Government, whose inauguration we have just commemorated, was made necessary by the avarice and fanaticism of an ever increasing sectional majority, is to speak the truth; but that measure of it only which lies upon the surface. Sterner questions lie behind that. How happened it that among a Christian people, of Anglo-Saxon lineage, trained in all the great principles of English liberty, with every appliance of knowledge and experience--experience, moreover, worked out by their own ancestors--such vices should so early have gained such supremacy? How did it come to pass that constitutional law should so completely have lost its power, that the moral sense of the nation should have been so drugged, that its Christianity should have exerted no vital influence over its actions? Seventy years to terminate a nation's existence! Why Rome existed eight hundred years before she reached the culminating point of her greatness. It is now a thousand years since England commenced her career of power and of fame. Russia is only "mewing her mighty youth," although she has already outlived our age by centuries. By what fatality is it that we have become effete at so early a period; that we were corrupt to the core ere we were well out of the bud; that, like a young spendthrift, we

Page 7

have wasted health, vigor, virtue, in our earliest manhood, and are already decrepid and breaking up under the diseases which belong only to old age? Alas! that we should have to answer such appalling questions; to answer them, too, in the midst of the tumultuous and terrible results which they have naturally brought about. But they must be answered, or else we shall gain nothing from the revolution through which we are passing; shall reap no fruits from the seed which we are fructifying with the rich blood of our children.

It will not do to say that we were only the offshoot of a long existing nation, and that we came into being with its infirmities cleaving to us, and not with the vigor of a fresh and buoyant life. 'Tis true, husbandmen say that a graft from a tree, however young and living it may be, will droop and wither when its parent stem shall perish; but alas for us, our Fatherland is still mighty in its power, is still overshadowing the world with its wings of protection and of glory. We have not decayed because England has decayed. We have not fallen to pieces like a house builded upon the sand, because the winds and the waves have swept her into oblivion. She is stronger to-day in her law, in her religion, in her arms, in her arts, than when we tore ourselves away from her motherhood. She yet rejoices in all the freedom which has been her birthright for centuries, and evinces no token that her eye is dim or her natural force abated. If we would excuse our early decrepitude, we must find some other reason than one drawn from our having sprung from a people which had reached the spring tide of its glory. If the graft has withered, we must rather look for its blight from the stock upon which it has been grafted, for the parent stem, the oak of old England, still spreads its arms in ever increasing grandeur, defiant of the storms which rage incessant around its incorrupt heart.

Nor can we truly affirm that our early decay has sprung from the rapid influx upon our shores of foreign elements, which have overborne the native influence and subjected it to its control. The tides of avarice and of fanaticism which have swept over our fair heritage and changed it into a desolation,

Page 8

have flowed in upon us from the most ancient and best civilized of our States, and have ever found their increasing momentum from those peculiarly native fountains. The Europeans who have settled the western States, and who have filled our cities, have been finally made their tools, but only after they had been deceived and made to believe that their own liberties were in danger from the slavery of the South. They have given power to the destructive flood which has borne away all the barriers of constitutional law, but only as a lake whose waters have been turned by human art into the channels of the natural stream. What knew they, the simple-minded peasants of Germany and Scandinavia, of our political questions, until they were indoctrinated by the pestilent demagogues who undertook to introduce them to the tree of knowledge? What cared they, the laughing, careless emigrants from the green fields of the Emerald Isle, about such points as have wrecked our Union, until wily politicians sat, like the toad at the ear of Eve, and whispered sin and mischief to their untutored souls? The disgrace of this early and incomparable corruption is our own, born of the soil, springing rank from the principles which were laid at the basis of our political nationality. We cannot get rid of it. We cannot shuffle it off upon those who are as innocent of it as a deceived and cheated accessory is innocent of a crime into which he has been unwittingly drawn. We must bear it ourselves in the face of the world and evince our shame by clearing our skirts of it, and our penitence, by putting our new wine into new bottles.

Nor can we shield ourselves from the scorn of the world by affirming that this revolution has arisen out of political causes alone, and not out of moral causes; for they have eyes and can see, ears and can hear, minds and can understand. I affirm that this revolution was as much a moral as a political necessity; that corruption had become deep-seated in philosophy, in letters, in ethics, in religion as well as in politics; that it had found its way into commerce and trade, and finance and social life; that cunning and trickery were becoming the normal conditions of intercourse, and that morals

Page 9

were fast losing their hold upon the public mind. There is no instance upon record of such a rapid moral deterioration of a nation as has taken place in ours in the last forty years. Growing in all the elements of political and economical greatness at a pace unexampled among nations, their increase was not faster than the corruption which they engendered. So soon as the stern, honest, uncompromising men of the Revolution--men who had been trained under other principles-- passed away, the new order of things began to manifest itself in political circles, and from them extended to the press, to the legislative chambers, to the primary assemblies of the people, and, finally, to the last bulwarks of every nation, the judiciary and the pulpit. It became almost impossible to resist the torrent of evil, and men at last began to call good evil and evil good, sweet bitter, and bitter sweet, against their own better sense and wiser consciences. What was expedient was right; what was popular was just; what was low and cunning was smiled upon, if only it chanced to be successful. No government could endure under such a condition of things. No people could work out any destiny, but discord and anarchy, with such principles festering at its heart. What has happened was inevitable. The irrepressible conflict between the slave and the hireling brought it to a point, but if that had never existed, some other discord would have arisen, which would have rent asunder a people, that, even in its yet early manhood, had exhibited and gloried in the vices of a nation tottering to its fall.

The question then recurs: "In what are we to find the causes of this rapid corruption and this early moral obliquity? What has made it necessary, ere a century has elapsed, to remould our institutions, and to look with dismay upon our late fellow-citizens, as they yield up to passion all their constitutional guarantees and bow, without a struggle, before the decrees of a maddened people?" And my answer is: "We can find them in the principles upon which we planted our Government; principles which have reacted upon our whole social life; upon our politics, upon our literature, upon our morals, upon our religion, upon our homes. They were false

Page 10

and unscriptural, and have worked out very soon the inevitable law, 'That whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.'"

The principle upon which we rested our Revolution, that "taxation without representation is tyranny," was clearly true, and our forefathers were right in resisting its exercise and in meeting its encroachments at the very earliest moment. The time had come, likewise, when it was well for us to manage our own affairs, and to be independent of other nations. But there was no necessity to cast to the winds all conservatism and to lay down principles, as the foundation of our Government, which were contrary to Revelation, and, therefore, to Truth. Carried away by our opposition to monarchy and an established Church, we declared war against all authority and against all form. The reason of man was exalted to an impious degree, and in the face not only of experience, but of the revealed word of God, all men were declared to be created equal, and man was pronounced capable of self-government.*

*As this expression may be susceptible of misconception, inasmuch as any Government which may be framed by a people, however well checked and balanced, is to a certain extent self-government, I would state that my argument is directed against that doctrine which blasphemously affirms the "vox populi"

to be the " vox Dei," and which would maintain that the will of a majority must always be right and should always rule--a doctrine from which we have been just forced to escape.

Two greater falsehoods could not have been announced--falsehoods, because the one struck at the whole constitution of civil society as it had ever existed, and because the other virtually denied the fall and corruption of man. If man is capable of self-government, what need of any government at all? If man is wise enough and virtuous enough to manage not only his own affairs, but to conduct with brotherly love--loving his neighbor as himself--all his relations with his fellow man, why such an apparatus of machinery as is every where required for the administration of justice? Man is not capable of self-government because be is a fallen creature, and interest, passion, ambition, lust, sway him far more than reason or honor. As for equality among men, whether by creation or birth,

Page 11

or in any other way, it is a miserable ignis fatuus, not worthy to be followed, even for the purpose of exposure. Upon principles as false and as foolish as these was our late Government founded, and although wise men attempted to place conservative barriers around their exercise, and did preserve them, during their life time, against the working of the principles which were perpetually undermining them, when they passed away, the process of demolition fairly commenced, and it required but a man's life time--and that not a long one--to place every thing that was valuable in home and in society at the mercy of the demagogues, who sounded these false doctrines in the ears of an irresponsible multitude. Like the spawn of error in Spenser's allegory, the moment they were born, they began to gnaw upon the vitals of their mother. If all men are created equal, (thus consequentially did they carry out the principle), then should there be no classification of society, no master and no slave, no capitalist and no workman, no rich and no poor, no learned and no ignorant. If all men are created equal, then is the Governor no better, no wiser, no more to be honored than the governed; then is the Judge to be no more learned, no more experienced, no more reverenced, than the parties at the bar; then is the Priest to be no more holy, no more educated in sacred things, no more consecrated to his divine office, than the people; then is the father to be as the child, and the grey hair and the reverend form to be upon a level with the presumptuous youth. If man is capable of self-government, then is the whole framework of civil society to be arranged by the will of a majority; then are no guarantees necessary for life or for property; then are rulers from the highest to the lowest to be placed or displaced by caprice or faction; then is the sacred ermine of justice to be dragged through the mire of party, and to be soiled by all the miserable influences of selfishness. Such are the legitimate fruits of these principles, and they have been produced to the destruction of our country. Like the apples of Sodom, they were fair to the eye and looked bright and healthful, but they have turned to ashes in the mouth. To our cost have we found

Page 12

that they would be utterly destructive not only to our interests, but to the peace of our whole social life, and we have withdrawn from those, who were prepared to carry them out to their full desolation, and to make us the first victims of their triumphant exercise.

This picture has not been overdrawn. It is the stern truth, and is witnessed to by the condition of society wherever they have had full sway. Among us they have been partially checked in their operation by our adherence to the doctrine of State Sovereignty and by the institution of slavery, which has forced upon us a certain measure of conservatism. The falseness of these principles was too glaring to us to permit us to be entirely carried away by them. But even we have felt their influence in those arrangements of society which were not immediately connected with our local interests or local institutions. Where is there, even among us, guarded and protected as we have been, any reverence for age, or authority, or experience? What boy is there who does not think himself capable of self-government, fit for any position; who is not quite ready to sneer at the past and to consider the wisdom of the old as the dotage of infirmity? What man is there who does not deem himself qualified to fill any office, or to discuss and criticise any matter, even though he may never have applied an hour's study or a moment's thought upon it? What politician will dare to stand up and tell the people that they are wrong, or fill the breach when they rush to the assault upon any of the institutions of the land? What power has philosophy or morals, or even religion, against the popular will? Have not all the conservative influences of our General and State Governments been progressively overturned, and new doctrines, all based upon these principles, been worked into the public opinion of the people? It is fearful to perceive what a low tone of ethics pervades our literature and our press; how morality has been dissevered from religion; how all form, which at last is the embodiment of spirit, is ridiculed and scorned. And when we read our Bibles, and note the catalogue of vices which St. Paul said should characterize the perilous times of the last days, we shudder at the number

Page 13

of them which have been the legitimate fruits of our national principles. "This know also," writes he,"that in the last days perilous times shall come, for men shall be lovers of their own selves, covetous, boasters, proud, blasphemers, disobedient to parents, unthankful, unholy, false accusers, incontinent, fierce, despisers of those that are good, heady, highminded, lovers of pleasure more than lovers of God; having the form of godliness, but denying the power thereof." Of his whole catalogue I have omitted but three classes, which may yet be developed, ere our struggle is at an end: "Without natural affection, truce breakers and traitors." Is not this enough to make us tremble? Does it not bear out every thing which I have written and spoken this day? Well for us that we have burst the bonds which bound us to such principles! Better for us, if we shall be able, by the grace of God and the virtue which is left in us, to put our "new wine into new bottles."

It is useless, upon these days of humiliation, in which we come before God to repent of our national sins, to spend our confession and our penitence upon the mere excrescences which show themselves upon the surface. It is a mockery of God, who looks far beneath that surface, and who sees and knows that a corrupt tree can never bring forth good fruit. He expects us to pierce to the core, to dig down and stir up to the very roots whence spring these wretched consequences. Unless we do this, He will not help us. "Be not deceived; God is not mocked." He sees where the difficulty is, at what door the sin lies, and He sees, moreover, that we know it, and have not the courage to avow it. But unless we do confess it and humble ourselves before Him, and ask Him to remove away from us these idols of "human reason," and "man's natural virtue," all our present struggles shall be in vain; our valor, our sacrifices, our own blood and the blood of our children, shall all have been spent for nought. The new wine will burst the old bottles and be spilled, and the old bottles shall perish, the example and scorn of the world. Let those whom we have left go on, if they please--but God forbid, for their sakes, that they should--upon such infidel principles; but let us, now that we have the opportunity, retrace

Page 14

our steps, and take once more to our arms the word of God and the wisdom of God.

But you may ask: "To what does all this tend? Shall we go back to monarchy, to aristocracy, to an established Church?" Better, far better that, than to run into anarchy, pass through the fierce fires of infidelity and licentiousness, and then end in a stern military despotism. But neither is necessary. The form of a Government is not the important point; it is the principles. Republicanism has not saved us from tyranny and oppression, and monarchy has not deprived England of freedom. The cruelty of any king is tender mercies to the cruelty of an unbridled multitude. It is not the shape which the Government has taken that is our danger; nay, that arrangement of wheel within wheel, of a State Government exercising sovereign powers within a General Government, has been our preservation, the very ark of our safety. It is the principles which lie at the foundation of a Government and which will flow out from that Government and pervade every department of civil and social life, that is our peril. Poland was a monarchy, but the principle of equality among the nobles produced precisely the like consequences as those which have sprung from the principle of equality here. The remedy is not in any change of Government, but in the modification of principles, which, having the prestige of authority, have influenced the whole spirit of the people, and have rendered irreverence, insubordination, presumption, recklessness, of the very essence of the national character. Like Laocoon and his children, we have been enfolded and crushed by the serpents which have issued from our own altars.

We must go back to the principles of the Bible, if we would find our permanent remedy, and reject as infidel any faith in man's virtuous self-government, any idea that society or government can exist without due classification. Subordination reigns supreme in Heaven, and it must reign supreme on earth. Subordination, not inferiority; they are very different things. The one is the obedience and the reverence of duty; the other of degradation. The one finds honor and glory in

Page 15

being true and faithful to its position; the other has no merit, because it fills but its own proper place. The one has sublime examples in the subordination of the Church to Christ, in the subordination of the Son of God to his Almighty Father; the other has its illustrations only in the natural gradation of created things. Without this discrimination between subordination and inferiority, there can be no highly civilized society. It is the support of all authority, the true moral principle of all order in social life. When the Spartan youths all rose upon the entrance of an old man into their assembly, they exhibited the true meaning of subordination, and honored themselves while they displayed the high principles of their civilization, Pagans though they were.

In this country there is nothing to keep man in check except the principles which he himself may lay at the foundation of his government, and which may extend their influence through all the phases of social life. Military power is the arm of despotism for preserving order. We know, except in war, no such instrument. We are dependent upon the people themselves for the preservation of order, and unless they shall be trained to be the guardians of law, there can be no law. When the very principles upon which a Government and its civilization rest lead inevitably to disorder and to irreverence, how can you look for the virtues which are the only support of any Government? You may as well expect grapes from thorns or figs from thistles. The remedy for all this lies not in any change in the form of our Government, but in persuading ourselves, who are the people, to surround ourselves once more with Constitutional arrangements, which shall be a bulwark against our own capricious or passionate impulses, and which shall give the lie to any demagogue who shall attempt to persuade us that we are capable at all times of governing ourselves, and that every one of us is the equal of his fellow. We should at once endeavor to put it out of our own power to corrupt ourselves, by laying down fundamental propositions of the most conservative character, and adhering to them through good report and through evil report. If in this moment

Page 16

of our soberness and of our sadness, we could break up our old bottles, and put our wine into new bottles, framed out of stuff which has stood the experience of ages, we should have cause to bless this revolution all the days of our history.

"But as no man having drunk old wine straightway desireth new, for he saith the old is better," the question comes up by what means may these old principles be done away with and new ones be introduced? And I rejoice to say that already have our Governments, both State and Confederate, made some movements in the direction of Faith and of conservatism. The recognition of God in our Constitution--would it had been a clear, plain recognition of Christ--is in itself a step almost equivalent to that which France made in her reaction from atheism to Christianity. We have scarcely realized, my Christian hearers, what was the position of the old Government in its relation to God. It was as atheistic as France in her worst days of wild revolution. The Goddess of Reason, 'tis true, was not paraded through our streets and personified in the high seats of legislation under the form of an harlot, but God was as completely ignored and the perfectibility of man placed in his stead. No such thing is on record any where in the world, whether among barbarian or civilized people, that a nation had no recognized God! We deem it the height of superstition, when we read of the Pantheon at Rome, in which were gathered all the Gods of all the nations, that honor might be done to all. But what was our country, as it stood under the old Constitution, but a Pantheon, in which every man worshipped his own idol and demanded the protection of the Government in his folly? Thank God, we have washed out that stain, and if we have not yet distinctly proclaimed ourselves a Christian nation, we are at least a nation of Theists--men who recognize the presence of God in the affairs of the world. That is a point gained; a step out of darkness into light; and for that He may bless us and give us more light. We need it sadly upon our path, for we have to tread our way back, through peril and blood, to the great principles of faith and honesty, which underlie all well established Governments. Already have our people willingly laid

Page 17

down upon the altar of their country some of the false principles which they had been tempted to try, and have evinced a willingness to distrust themselves. May the good work go on until our children shall regain what we have lost; until authority shall be reverenced, because it is ordained of God; until justice shall be made independent of either money or faction; until religion shall throw aside its mere spiritualism, and shall become the conservator of morals as well as a guide to Heaven.

It may be that the bloody war in which we are engaged is necessary for our purification. War is a fearful scourge, as God's word plainly tells us; but it may sanctify as well as chasten, it may purge out our old dross, even though it be through the fires of affliction. It may be our moral as well as our political safety. The infidel principles which I have been discussing have, even in a century, struck deep root into the minds and hearts of our countrymen, and it requires an equally deep cautery to burn them out. Had our separation been a peaceful one, we should have gone on as before, trusting in what are called the principles of American independence, expecting to find permanent prosperity under the old popular doctrines of the land. Our people had great faith in the form which freedom had assumed in this land, because they attributed to it the unexampled physical prosperity which encompassed them. Its evil principles had not yet been worked out to their perception, although discerning minds have long foreseen the coming catastrophe. This cruel war, together with the rapid crushing out at the North of all freedom of thought and of action, will enable them to understand clearly the effects of principles which would leave no checks and balances in a Government, and which make the multitude believe that their will should override all law and all constitutions. It will be easier then, perhaps, to persuade them to drink the new wine, when they shall have seen the deleterious effects of the old. Besides this, war will necessarily, when it presses upon us with severity, as it is likely now to do, quell faction, break up party spirit, bring out patriotism, valor, self-denial, heroism, which, although they be worldly virtues, are far better than

Page 18

selfishness and a narrow-minded avarice. It will stir up all the energies of the people, which were stagnating under the effects of indolence and isolation. It will drive the islander from his sea-girt home, in which the winds and the waves were soothing him to sleep with their wild lullaby; it will bring the mountaineer from his lonely valley, where his mind was circumscribed by its crags and precipices, and it will mingle them with the great mass of the people, and out of the crucible will come a nation, with larger views, with nobler feelings, with energies high strung for all the purposes of national life. And this people, thrown upon its own resources, will develope them by their own industry, and mingling through commerce with the world, will learn the value of virtues which they have hitherto permitted to slumber, will open their minds to perceive that other nations may teach them lessons not only of literature and science, but of freedom and government. And thus will they learn the true value of Liberty. To use the rich language of Macauley: "At times she takes the form of a hateful reptile--she grovels, she hisses, she stings--but woe to those who in disgust shall venture to crush her. And happy are those who, having dared to receive her in her degraded and frightful shape, shall at length be rewarded by her in the time of her beauty and her glory."

Return to Menu Page for New Wine Not to be Put in Old Bottles... by Stephen Elliott

Return to The Southern Homefront, 1861-1865 Home Page

Return to Documenting the American South Home Page