Facts and Suggestions on the Subjects of Currency and Direct Trade,

Addressed to the Chamber of Commerce of Macon, Ga.:

Electronic Edition.

Green, Duff, 1791-1875.

Funding from the Institute of Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Andrew Smith

Images scanned by

Andrew Smith

Text encoded by

Ellen Decker and Joshua G. McKim

First edition, 2001

ca. 125K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) Facts and suggestions on the subjects of currency and direct trade, addressed to the Chamber of Commerce of Macon, Ga.

By Gen. Duff Green

28 p., [1] leaf of plates

Macon

Printed for the Chamber of Commerce

1861

Call number 2762conf (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

This electronic edition has been created by Optical

Character Recognition (OCR). OCR-ed text has been compared against the

original document and corrected. The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- Confederate States of America -- Commerce.

- Confederate States of America -- Commercial policy.

- Confederate States of America -- Economic conditions.

- Currency question -- Confederate States of America.

- Finance, Public -- Confederate States of America.

- Foreign trade regulation -- Confederate States of America.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Finance.

Revision History:

- 2001-04-11,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-02-01,

Joshua G. McKim

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-11-29,

Ellen Decker

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-11-15,

Andrew Smith

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

FACTS AND SUGGESTIONS

ON THE SUBJECTS OF

Currency and Direct Trade,

ADDRESSED TO THE

CHAMBER OF COMMERCE

OF

MACON, Ga.

BY

GEN. DUFF GREEN.

MACON:

PRINTED FOR THE CHAMBER OF COMMERCE:

1861.

Page 3

LETTER.

TO WM. B. JOHNSTON,

President of the Chamber of Commerce, Macon, Ga.

SIR:

It is with pleasure I acknowledge the receipt of your invitation to attend the Convention, proposed to be held in Macon, on the 14th of October, for the purpose of considering how far it is practicable to achieve the financial independence of the Confederate States; and having given to the subject many years of anxious consideration, I venture to submit a proposition for the organization of an agency, which I believe will be an efficient means of relieving us from the grievous burdens heretofore the consequence of our system of Commerce and Finance.

The report of the Secretary of the Treasury of the United States of March 26, 1860, gives a statement of the condition of the Banks of the United States, from which I have prepared the following tables, showing their capital, loans and discounts, specie, circulation and deposits. That we may the better realize their relative strength, I have given the population of each State, and have separated the slaveholding from the non-slave holding States:

| Slaveholding STATES. | No. of Banks and Branches. | Capital. | Loans and Discounts. | Specie. | Circulation. | Deposits. | Population. |

| Alabama | 8 | $4,901.000 | $13,570,027 | $2,747,174 | $7.477,976 | $4,851,153 | 995,917 |

| Delaware | 12 | 1,640,775 | 3,150.215 | 208,924 | 1.135,772 | 976,226 | 112,353 |

| Florida | 2 | 300,000 | 464,630 | 32,876 | 183,640 | 129,518 | 145,694 |

| Georgia | 29 | 16,689,560 | 16,776,282 | 3,211,974 | 8,798,100 | 4,738,289 | 1,082,797 |

| Kentucky | 45 | 12,835,670 | 25,284,869 | 4,502,250 | 13,520,207 | 5,662,892 | 1,159,609 |

| Louisiana | 13 | 24,496,866 | 35,401,609 | 12,115,431 | 11,579,313 | 19,777,812 | 666,431 |

| Maryland | 31 | 12,568,962 | 20,898,762 | 2,779,418 | 4,106,869 | 8,874,180 | 806,796 |

| Missouri | 38 | 9,082,951 | 15,461,192 | 4,160,912 | 7,884,885 | 3,357,176 | 1,201,209 |

| North Carolina | 30 | 6,626,478 | 12,213,272 | 1,617,687 | 5,594,047 | 1,487,273 | 1,008,342 |

| South Carolina | 20 | 14,962,062 | 27,801,912 | 2,324,121 | 11,475,634 | 4,165,615 | 715,371 |

| Tennessee | 34 | 8,067,037 | 11,751,019 | 2,267,710 | 5,538,378 | 4,324,799 | 1,146,640 |

| Virginia | 65 | 16,205,156 | 24,975,792 | 2,943,652 | 9,812,197 | 7,720,652 | 1,593,199 |

| Texas | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 600,955 |

| Arkansas | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 440,775 |

| Mississippi | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 887,158 |

| New Mexico and Indian Terr'y | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 120,000 |

| Total | 327 | $128,176,517 | $207,749,681 | $38,912,129 | $87,107,108 | $66,074,585 | 12,683,246 |

Page 4

| Non-slaveholding States. | No. of Banks and Branches. | Capital. | Loans and Discounts. | Specie. | Circulation. | Deposits. | Population. |

| Connecticut | 74 | $21,502,176 | $27,856,785 | $989,920 | $7,561,519 | $5,574,900 | 460,670 |

| Illinois | 74 | 5,251,225 | 387,229 | 223,812 | 8,981,723 | 697,037 | 1,687,404 |

| Indiana | 37 | 4,343,210 | 7,676,861 | 1,583,140 | 5,390,246 | 1,700,479 | 1,370,802 |

| Iowa | 12 | 460,450 | 724,228 | 255,545 | 563,806 | 527,378 | 682,002 |

| Kansas | 1 | 52,000 | 48,256 | 8,268 | 8,395 | 2,695 | 143,642 |

| Maine | 68 | 7,506,890 | 12,654,794 | 670,979 | 4,149,718 | 2,411,022 | 619,958 |

| Massachusetts | 174 | 64,519,200 | 107,417,323 | 7,532,647 | 22,087,920 | 27,804,699 | 1,231,494 |

| Michigan | 4 | 755,465 | 892,949 | 24,175 | 222,197 | 375,397 | 754,291 |

| N. Hampshire | 52 | 5,016,000 | 8,591,638 | 255,278 | 3,271,183 | 1,187,991 | 326,072 |

| New Jersey | 49 | 7,884,412 | 14,909,174 | 940,700 | 4,811,832 | 5,741,465 | 676,684 |

| New York | 303 | 111,441.320 | 200,351,332 | 20,921,545 | 29,959,506 | 104,070,273 | 3,851,563 |

| Ohio | 52 | 6,890,838 | 11,100,462 | 1,828,640 | 7,983,889 | 4,039,614 | 2,377,917 |

| Pennsylvania | 90 | 25,565,582 | 50,327,157 | 8,378,474 | 13,132,892 | 26,167,843 | 2,924,501 |

| Rhode Island | 91 | 20,865,569 | 26,719,877 | 450,929 | 3,558,295 | 3,553,104 | 174,621 |

| Vermont | 46 | 4,029,210 | 6,946,523 | 198,409 | 3,882,983 | 778,834 | 315,827 |

| Wisconsin | 108 | 7,620,000 | 7,592,361 | 419,947 | 4,429,855 | 3,085,813 | 768,485 |

| California | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 384,770 |

| Minnesota | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 172,793 |

| Oregon | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 52,566 |

| Utah Territory | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 50,000 |

| Washington do. | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 11,624 |

| Nebraska do. | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | . . . . . | 28,893 |

| Nonslavehold'g | 1224 | $293,713,547 | $484,195,949 | $44,662,408 | $119,997,469 | [$]187,718,544 | 19,033,113 |

| Slaveholding | 327 | 128,176,517 | 207.749,681 | 38,912,129 | 87,107,018 | 66,074,585 | 12,683,246 |

I find in a newspaper an article, credited to the N.Y. News, so appropriate that I quote it at large:

"There is so much misapprehension in relation to our foreign trade, and it is so important at the present juncture to have a correct understanding upon the subject, that at the risk of repetition we shall recur to it again. For this purpose we shall take from the official returns of 1861, the amount of exports, distinguishing the exclusively Northern from the exclusively Southern origin of the articles:

| NORTHERN ORIGIN. | |

| Products of the sea . . . . . | $ 4,156,180 |

| Forest . . . . . | 9,368,917 |

| Provisions . . . . . | 20,215,226 |

| Breadstuffs . . . . . | 19,022,901 |

| Manufactures . . . . . | 25,599,547 |

| Total Northern Origin . . . . . | $77,363,070 |

| SOUTHERN ORIGIN. | |

| Forest . . . . . | $ 6,085,931 |

| Breadstuffs . . . . . | 9,567,397 |

| Cotton . . . . . | 191,806,555 |

| Tobacco . . . . . | 19,278,621 |

| Hemp, &c. . . . . . | 746,370 |

| Manufactures . . . . . | 10,934,795 |

| Total Southern Origin . . . . . | $238,419,680 |

| Total exports . . . . . | $335,782,740 |

| Imports consumed . . . . . | 336,380,172 |

These are the figures of the Treasury table, and their careful consideration may dispel some strange illusions that possess the public mind. Among the items, it will be observed under the head of products of the forest, Georgia pine and lumber, naval stores, &c., bear a high figure. All those who have been patiently awaiting the South to be "starved out" will observe with some surprise, that it supplies one-third of all the breadstuffs exported from the Union. Hence, if they cannot "eat Cotton" they will not starve. The manufactures which originate in the South form also a small sum total for which many are not prepared.

The result is that the North furnishes one-fourth of the merchandize exported and the South three-fourths. It will now be understood that three-fourths of the national exports are embargoed by blockade. It is very important thoroughly to understand that fact, because on it hangs all the finance of the war. Breadstuffs and provisions, it will be observed,

Page 5

form one half of the Northern exports, and the harvest in England being good, those articles, if sold at all, must be sold very low.

If we turn to the importations into the country we find the following results:

| Specie. | Goods. | Total. | |

| North, | $4,780,598 | $316,842,381 | $321,592,970 |

| South, | 3,770,546 | 36,802,738 | 40,573,284 |

| Total, | $8,551,135 | $353,645,119 | $362,166,254 |

The specie imports at the South are mostly silver from Mexico, and of the merchandize, coffee counts $9,731,617; sugar for $3,500,000; for Western account, iron, queens ware, &c., for the balance. Now, if we bring the aggregates together, they will show as follows:

| Total Im. | Total Ex. | Excess Im. | Excess Ex. | |

| North, | $316,812,381 | $77,367,070 | $239,449,311 | -- |

| South, | 36,802,738 | 238,419,670 | -- | 201,616,932 |

We have here the conclusive fact that the three-fourths of the whole foreign trade of the country is Southern. The exports are produced there, and the goods they get payment for come to them through New York, to the great profit of its merchants. The South also sent North for Northern consumption, last year as follows:

| Cotton, 1,000,000 bales, | $55,000,000 |

| Tobacco, | 10,000,000 |

| Sugar, | 18,000,000 |

| Rice, | 1,000,000 |

| Wheat and corn, | 5,000,000 |

| Naval Stores, | 1,000,000 |

| Total, | $90,000,000 |

For this and more, domestic manufactures and Western produce, mingled with imported goods, went South in payment. The whole of this is blockaded. The Morrill tariff was intended to increase the proportion of domestic manufacture and diminish the proportion of imported goods sent South in payment[.]

It will now be remembered what we recently stated, that even if the North can sell as much breadstuffs this year as in the year of short harvests, she has in round numbers but $80,000,000 with which to pay for the tea, coffee, sugar, and all those articles that made up this aggregate of $336,280,172 of goods imported, besides $22,000,000 of interest money to be paid abroad. To import the same amount will involve the payment of $256,000,000 of specie in a single year, or every dollar in the country, North and South. If one-third only of the usual imports were made, the pressure for specie will be such as to make loans impossible and taxes unavailable. An importation of $125,000,000 only, would give hardly more revenue, even under the Morrill tariff, than would pay the interest on the public debt, while it would convulse the country by draining it of specie.

The fact must continually be borne in mind that the Middle and New England States can, of themselves, have little or no trade with England and Western Europe, because they are producers of the same articles. New England competes with Old England in the purchase of raw materials and food, and the sales of manufactured articles. There are no trading interests between them. They both want Western food, and both want Southern materials. Of the importations that are brought in into New York, a large portion goes to the South, which raised the produce with which tney were purchased through New York commercial houses.

In this connection, we call attention to the following, from the London Economist, in relation to the British trade for the first three months of this year:

"Our commerce with the South and with the North is now for the first time divided in the official tables. It appears that all our direct exports are to the North. The figures are:

| Exports to Northern States, | £3,922,133 |

| Exports to Southern States, | 174,563 |

Page 6

Showing a startling contrast in the amount we actually sell to the two belligerents. The contrast is nearly as remarkable in what we buy, only it is reversed!

| Imports into Great Britain from Northern ports, | £4,697,868 |

| Imports into Great Britain from Southern ports, | 6,136,186 |

"We see in these simple figures the record of the causes of much that has occurred in Lombard street.

"It is therefore difficult to say with which of the combatants in this miserable struggle we are the most connected. One party supplies us with the materials of our industry, the other party purchases the fruits of that industry from us."

This is a very singular error for so high a commercial authority as the London Economist to fall into. What England receives is Southern produce, direct from the South; but what she sends to the North, that is to say, to New York, is on its way to the South. If the separation was unfortunately to take place, England would not continue to sell largely to the North, but the goods would go direct to the ports from whence the raw material is derived. In such an unfortunate state of affairs the West would be bound over hand and foot to the Eastern States. She would have to buy their manufactures dear and sell them food cheap. The interests of the South and the West are identical, both being agricultural, and both of them sources of supply for Europe in opposition to the Eastern States. The great Western valley of the Mississippi, with its undeveloped natural manufacturing advantages, has the vast Southern market open to its future enterprise, when capital shall have accumulated from agricultural industry and fertile land. This war is retarding her progress fifty years at least, and perhaps ruining it forever.

If we analyse the condition of the banks, we find that they had--

| Loans and discounts[,] | $691,945,580 |

| Circulation, | 207,102,477 |

| Deposits, | 257,802,127 |

| Making a mass of credits of, | $1,152,850,184 |

| Whilst the specie in all the banks was only, | 83,594,537 |

It will be seen that with a population of 3,851,563, New York had--

| Capital, | $111,441,320 |

| Deposites, | 104,070,273 |

| Loan and discounts, | 200,351,332 |

| Specie, | 20,921,545 |

| Circulation, | 29,959,506 |

The slaveholding States, with a population of 12,683,246, had--

| Capital, | $128,176,517 |

| Deposites, | 66,074,585 |

| Loans and discounts, | 207,749,681 |

| Specie, | 38[,]912,129 |

| Circulation, | 87,107,108 |

Why is this? We have seen that the South furnish $238,419,680 of the exports, whilst the entire North furnish but $77,368,070; and as these exports are the basis of our foreign trade, there must be some efficient cause which has produced such a striking difference between the financial organization of the North and of the South. What is that cause? Is it not

Page 7

that the South is agricultural and the North is commercial and manufacturing? Is it not because the financial system of the United States was organized in reference to the business of the North, and that the organization is not suited to the business of the South? The dealings of the merchant and manufacturer are from day to day. The dealings of the planter are from year to year. The banking system of the United States was organized in reference to the business of Northern men, and is therefore adapted to the business of merchants and manufacturers, whose daily receipts enable them to make frequent payments, but it is not adapted to the business of planters, whose receipts being from year to year, require an entirely different financial arrangement. Is the condition of the financial world such that we can organize a financial system suited to the industry and wants of the South, which will enable the planters of the South to make a safe and profitable use of credit? I believe it is, and propose to create, as the basis of such a system, an agency, to consist of an incorporated company with sufficient capital, to be invested in good public and private securities, with branches and agencies in the several Confederate States and in Europe.

Have we the means of creating such an agency? The cotton crop may be estimated at $200,000,000 per annum. Part of the proceeds invested in the Treasury notes or bonds of the Confederate States, and paid in as the capital of the "Agency," would create at once a basis of credit, which would enable the Agency to borrow money in Europe on their hypothecation at a low rate of interest for a term of 20 or 30 years, and to advance funds to Railroad companies and to planters and others upon such terms as may be suited to their means of payment.

But though such an agency would in this way do much towards the financial independence of the South, it would do much more by furnishing ample means for a direct trade to Europe and elsewhere. Our merchants have heretofore dealt chiefly in New York and New England, and it will be difficult for them to obtain credit in Europe, because they are not personally known there. Such an agency as I propose could, through its branches and agencies in the Confederate States, ascertain the character and standing of merchants wishing to

Page 8

purchase goods in Europe, and, by letters to their branches in London, Paris and elsewhere on the continent, enable any merchant in the Confederate States to purchase goods upon as favorable terms as any merchant of New York could do under any system of credit whatever.

Can such an agency be organized? I believe it can, and rely upon an appropriation of part of the proceeds of the cotton crop and of such part of the funds invested in our Railroads as will give the strength and resources requisite to the end proposed. Such an agency should be so organized as to realize the strongest possible credit, and this can be done if we can sufficiently unite the planting and Railroad interest of the Confederate States. Union and concert of action between them would be for their mutual advantage, and would command the co-operation of a large mass of capital already invested in Railway shares and bonds now held in Europe, and bring to our aid a body of so much wealth, intelligence and influence as to secure certain and permanent success. But as the proposition embraces the Railroad as well as the planting interest, I have prepared the following Tables from data given in the Railroad Journal and the published returns of the late Census, showing the miles of Railroad in operation in each State and their cost with equipments, the area of territory and the population of each State--separating the slaveholding from the non-slaveholding States:

| SLAVEHOLDING STATES. | Miles of Railroad in operation. | Cost, with equipment. | Area, in sq. miles. | Population. |

| Alabama | 798.6 | $20,975.639 | 50,772 | 995,977 |

| Arkansas | 38.5 | 1,130,110 | 52,198 | 440,775 |

| Delaware | 47.9 | 2,345,825 | 2,120 | 112,353 |

| Florida | 289.8 | 6,368,699 | 59,268 | 145,694 |

| Georgia | 1,241.7 | 25,687,220 | 58,000 | 1,082,797 |

| Kentucky | 458.5 | 13,852,062 | 37,680 | 1.159,609 |

| Louisiana | 419.0 | 16,073,270 | 41,346 | 666,431 |

| Maryland and District of Columbia | 833.3 | 41,526,424 | 11,070 | 806,796 |

| Mississippi | 365.4 | 9,024,444 | 47.151 | 887,158 |

| Missouri | 723.2 | 31,771,116 | 65,037 | 1,201,209 |

| North Carolina | 770.2 | 13,698,469 | 45,500 | 1,008,342 |

| South Carolina | 807.3 | 19,083,343 | 34.000 | 715,371 |

| Tennessee | 1,062.3 | 27,348,141 | 44,000 | 1,146,640 |

| Texas | 284.5 | 7,578,943 | 274,356 | 600,955 |

| Virginia | 1,525.7 | 43,069,360 | 61,352 | 1,593,199 |

| New Mexico and Indian Territory | . . . . . | . . . . . | 400,000 | 120,000 |

| Totals | 9665.0 | 279,533,065 | 1,283,850 | 12,683,246 |

Page 9

| NON-SLAVEHOLDING STATES. | Miles of Railroad in operation. | Cost, with equipment. | Area, in sq. miles. | Population. |

| California | 22.5 | $2,477,110 | 160,000 | 384,770 |

| Connecticut | 665.6 | 25,198,199 | 4,750 | 460,670 |

| Illinois | 2,757.7 | 107,720,937 | 55,409 | 1,687,404 |

| Indiana | 1,327.9 | 31,656,371 | 33,809 | 1,370,802 |

| Iowa | 395.3 | 13,347,475 | 50,914 | 682,002 |

| Maine | 544.6 | 20,431,701 | 35,000 | 619,958 |

| Massachusetts | 1,428.3 | 65,319,921 | 7,800 | 1,231,494 |

| Michigan | 1,132.8 | 44,072,226 | 56,243 | 754,291 |

| Minnesota | . . . . . | 1,000,000 | 81,259 | 172,793 |

| New Hampshire | 565.2 | 17,785,111 | 9,280 | 326,072 |

| New Jersey | 556.4 | 26,463,455 | 6,851 | 676,084 |

| New York | 2,756.4 | 137,077,621 | 46,000 | 3,851,563 |

| Ohio | 3,008.2 | 127,949,123 | 39,964 | 2,377,917 |

| Oregon | . . . . . | . . . . . | 185,030 | 52,566 |

| Pennsylvania | 3,081.1 | 149,509,261 | 47,000 | 2,924,501 |

| Rhode Island | 63.6 | 2,747,568 | 1,200 | 174,621 |

| Vermont | 537.9 | 21,785,752 | 8,000 | 315,827 |

| Wisconsin | 826.0 | 44,576,044 | 53,924 | 768,485 |

| Utah Territory | . . . . . | . . . . . | 187,923 | 50,000 |

| Washington Territory | . . . . . | . . . . . | 123,002 | 11,624 |

| Kansas Territory | . . . . . | . . . . . | 114,798 | 143,642 |

| Nebraska Territory | . . . . . | . . . . . | 335,866 | 28,893 |

| Totals | 19,834.5 | 842,118,135 | 1,644,044 | 19,033,112 |

There are some striking and instructive facts exhibited in these Tables--the first of which is, the huge sums invested in railroads, and the character of the investments. Much of the sum so invested in the Confederate States is advanced by planters, more on the account of the reduction of the cost of transportation of their Cotton, than of the dividends on the shares. With them, it is a means of placing their crops in market, rather than an investment of capital. The appropriation of the sums so invested, as part of the capital of an "agency," to be substituted for the northern and foreign agents, whose credit has been heretofore so important a part of the machinery, by which Southern produce was placed in the foreign market, would seem to be natural and easy; and especially when we take into account the fact that the railroads now in use are but the commencement of a system requiring an expenditure many times greater than has been made, and that the proposed agency would enable Southern Railroad Companies to obtain funds for the further extension of the system, upon terms much more favorable than could otherwise be done.

It is now well understood and admitted that money, properly and economically expended on well located railroads, adds from five to ten times the sum so expended to the value of the property connected with such improvements; and that much of the boasted wealth of the North was derived from the use of their credit, and in the expenditure of the large sums invested

Page 10

in their railroads. The sums thus expended in the North were chiefly borrowed, and the credit which enabled them to borrow was created, chiefly, by the exports which were derived, as we have seen, from the South. But there is another striking feature of the past, which is, that the credit of the Northern Railroad Companies was worth more, and funds could be obtained by them in Europe on better terms than they could be obtained by the Railroad Companies of the South. The northern roads cost an average of $42,354 per mile, while the cost of the southern roads was but $28,929. The value of the exports of the South was more than three times that of the North, and being chiefly in cotton, rice, tobacco, lumber and naval stores, all bulky and heavy articles, and comparatively cheap commodities, furnishing nearly, if not quite, eight times the transportation, gave greater and more certain employment to the southern roads, and consequently a surer and better basis of credit. Why, then, was the credit of the Northern Railroad Companies better than the credit of the Southern? Why could Massachusetts borrow money in Europe at less than 5 per cent., when some of our best Southern Railroad Companies could not get it at 10 per cent.? Is not the answer to be found in the fact that the North has been the financial agent of the South? That whilst the excess of Southern products exported was $201,616,932, the excess of Northern imports was $239,449,311? Does not this solve the problem? Does it not explain why Northern credit has been worth more than Southern credit?

Have we no remedy? How did the North obtain the control of so large a part of our exports? Was it not by their association of capital that they were enabled to control the machinery of commerce? The credit of an association of fifty persons, each worth ten thousand dollars, is much stronger than the credit of either or all of them separately. It is in the association of capital, and concert of action, that the financial power of the North consists. If we would relieve ourselves from the tax, which they have levied on the profits of labor, we, too, must have associations of capital and concert of financial action; and our association and our action should be adapted to the nature and wants of our industry. The products of northern labor are made available as I have said, from day to day, at short periods; therefore the bank discounts at sixty or ninety days supply their wants and maintain their system of credits. The

Page 11

products of southern industry are made available from year to year, and therefore the planters require a different financial system, to enable them to make a profitable use of credit. Hence the northern banks, in concert with the European consumers, have organized a system of credits for the movement of the cotton crop, which assumes to be a prompt payment to the planter, but which in truth, gives to the purchaser a credit of nearly twelve months, taxing the planter with several commissions and sundry charges, which he is required to pay as an indispensable part of the machinery, by which more than $200,000,000 are paid for northern imports out of the proceeds of the sales of southern products, to be charged with a large additional commercial profit by the northern merchant, before the southern planter is permitted to use the merchandize imported and paid for with the products of his industry.

I am aware that the planter should not be a merchant, and that merchants, ships and banks are indispensable parts of the machinery of foreign commerce. I do not propose to make the planter a merchant, or to dispense with a single southern bank or a single southern merchant. What I propose is, to substitute an association of persons interested in the production and transportation of southern staples in lieu of the northern and foreign agents, who, by the use of the credit predicated on their control of southern labor, have levied many millions of dollars in the shape of commissions and commercial profits, upon the sale of the products of southern industry. The process heretofore has been that the merchants, factors and banks of the South delivered the products of southern labor to northern or European agents, in exchange for their credit in the shape of bills, which were paid out of the proceeds of sales made in the North and in Europe. I propose to substitute a southern agency, composed chiefly of southern planters, who by depositing with the agency in payment for shares, Confederate bonds and notes, or other good securities, will create a bona fide capital, which would have, here and in Europe, greater resources and a better credit than the northern or European agents to be superseded by them, and who being directly interested in protecting the value of their own labor, will use their credit and capital thus created to prevent its depreciation in the foreign markets. It will require no less southern banks and no less southern merchants to carry on the trade of the South than heretofore. So far from

Page 12

reducing the number or the profits of the southern banks or southern merchant, it is apparent that if, as I believe, the agency will aid in giving a direct trade with Europe, and by dispensing with northern agents and northern merchants, increase the value of southern exports, it will increase in like proportion the amount of southern imports, increasing in that proportion the consumption of foreign goods, which being free from the northern taxes heretofore levied in the shape of custom duties and commercial profits, will not only increase the number, but will proportionally increase the profits of southern merchants. The banks are the appropriate agents of the merchants, and a system which increases the number and profits of the merchants, will benefit the banks.

But I return to the objection that the planter should be a planter. He now employs a factor, through whom he transfers his crop to the northern or European agent, by whom it is sold in the North or in Europe. What I propose is, that the planters shall, by association, create an agency to supercede the northern or foreign agents. I admit that the value and efficiency of that agency will depend upon the persons chosen to manage it, and that these persons will be chosen by the planters. But if the planter is competent to select factors qualified to select the northern and foreign agents, heretofore part of the machinery of southern trade, surely they will be competent to select proper persons for the management of the agency to be organized by them as a substitute for the northern and foreign agents selected by their factors. The question then is reduced to this: Are the planters of the South competent to select proper persons to manage such an agency, and can such persons be selected in the South? That the planters can afford to pay salaries sufficient to command the best talents, of tried and unimpeached integrity, cannot be questioned; and that such persons can be had for sufficient compensation, is apparent in the skill and enterprise which characterize the people of the South, whether tested by the management of our banks, our railways, our literary institutions, or in the cabinet, the forum, the plantation or the field of battle. That we have among us persons competent to execute the trust, and that the association be fully competent to select them, we require no further proof than a comparison of the management of our banks and our railroads with the management of the banks and

Page 13

railroads in the North. What northern railroad can compare favorably with the railroads of Georgia, or what President or Superintendent of a northern railroad can compare favorably with the Presidents and Superintendents of our railroad companies?

But these considerations address themselves to the pecuniary interests of the South. I would present higher and stronger motives for the proposed association, which belong to the political relations of the Confederate States with the other peoples of the earth.

The entire population of the world is estimated as follows:

| Africa, (an estimate) from 60,000,000 to | 200,000,000 |

| America | 67,896,041 |

| Asia, including islands | 775,000,000 |

| Australia, and islands | 1,445.000 |

| Europe, | 275,806,741 |

| Polynesia, (an estimate) | 1,500,000 |

| Making estimated population to be | 1,301,647,782 |

As the population of Asia is so much greater than that of Europe, and the trade of India has, in the progress of European civilization, been more or less a monopoly, it has, in turn, enriched the nations by whom it was enjoyed, from the days of Solomon until now. A close monopoly of this trade was held by the British East India Company for more than two hundred years. They levied a tribute so great and imposed burdens so onerous, that, having exhausted the accumulated wealth of the former governments of India, they were compelled to rely, for payment of their demands, chiefly upon the cheap manufactures of India. But the invention of the cotton-gin, the power loom and the spinning jenny, had reduced the cost of textile fabrics in England so much below the cost of production in India that the East India Company could no longer make a profit on such goods imported from India. It was also found that the other European nations, profiting by the example of England, had established for themselves a system of manufactures, and instead of being, as they had been, consumers of British goods, had become competitors in the markets of the world. These European nations had few or no tropical colonies, and it was seen that, exercising a control over the trade with India, England, by exchanging her manufactures for the tropical products of India suited to the wants and consumption of her European competitors, could still levy a tribute, in the

Page 14

shape of commercial profits, on the tropical products of India, which she might receive in exchange for her manufactures, and sell for consumption to the other nations of Europe. But it was foreseen by Warren Hastings, the conqueror of India, and he wrote a pamphlet to prove, that African labor in America could produce at less cost than the labor of India could produce in India, and that therefore the abrogation of the African slave trade was indispensable to a profitable trade with India. It was seen that the abrogation of the African slave trade necessarily involved the abrogation of the monopoly of the East India Company and the repeal of the discriminating duties favoring the West India planters; and the merchants of Liverpool interested in the slave trade, the owners of West India estates and the East India Company united their influence and prevented the contemplated measures until 1833, when the British Parliament emancipated the slaves in the West Indies, repealed the discriminating duties favoring West India produce, abrogated the East India monopoly and opened the trade of India to British enterprise. The late wars with Russia, India and China, were but parts of the same system of measures for the maintenance and promotion of British commerce, and illustrate the extent and the manner in which the power and resources of England will be exerted for that object. Let us pause and examine the bearing of these facts upon the future of the Confederate States, and especially upon their relation to the interests and prosperity of the planters of these States.

The productive industry of a people is the true source of their wealth. England and Wales, with a population of less than 20,000,000, are estimated to have, in their machinery, a creative power equal to the labor of 600,000,000 of men. It is the profits derived from this employment of her capital that enables her pay $411,000,000 of taxes, the sum required to pay the interest on her national debt and the current expenses of her government. With her, then, the maintenance and continuance of her system of industry and commerce, is an indispensable necessity. She has 5,000,000 of people employed, and more than $500,000,000 of capital invested in the purchase and manufacture of cotton, and is dependent upon the Confederate States for three-fourths of the supply of the raw material. The question which most interests the more civilized and wealthy nations of the earth, who use machinery, is, how they can

Page 15

most advantageously dispose of the products of their industry to the less civilized, who do not use machinery; and hence, France and England, burying the traditional hatred of ages, united in opposing the progress of Russia and in the war with China, and made it a condition of the peace with China that they should be permitted to introduce their manufactures into China, and to take Chinese coolies, as laborers, to Australia and Algeria--the purpose being to use them as slaves, in the culture of cotton. I refer to these facts to show the relation which the growth and manufacture of cotton have to the progress and civilization of the age in which we live, and to enforce the necessity and propriety of an association of those interested in its production, for the maintenance and advancement of their common interests. We have a climate, soil and labor, which enable us to defy all competition; and we may assume that the progress of events and of public opinion will vindicate the character of our industry, and place the Confederate States among the first and greatest of civilized nations; and yet there are several features in the crisis in which we are now placed, which deserve to be considered.

The population of the United States in 1790 was 3,929,872, of whom 697,897 were slaves. In 1860 it was 31,676,217, of whom more than 12,000,000 were in the slaveholding States and more than 4,000,000 were slaves. The same relative increase would, in the next seventy years, give within the limits of the late United States, a population of 255,000,000, and to the slaveholding States, including New Mexico and the Indian Territory west of Arkansas, nearly 100,000,000, of whom 24,000,000 will be slaves, enabling the South to furnish more than 24,000,000 bales of cotton.

Europe, excluding Russia and Turkey, has a population of 195,434,660, on a territory of 1,455,025 square miles, divided into fifty separate governments, as follows:

| States of Europe. | Governments. | Sq. miles. | Population. |

| Andorra (Pyrenees) | Republic, | 190 | 7,000 |

| Anhalt-Bernburg, | Duchy, | 339 | 56,031 |

| Anhalt-Dessau-Cotten, | Duchy, | 678 | 119,515 |

| Austria, | Empire, | 248,551 | 35,040,810 |

| Baden, | Grand Duchy, | 5,712 | 1,335,952 |

| Bavaria, | Kingdom, | 28,435 | 4,615,748 |

| Belgium, | Kingdom, | 11,313 | 4,671,183 |

| Bremen, | Free City, | 112 | 88,856 |

| Brunswick | Duchy, | 1,525 | 274,069 |

| Church, States of the | Popedom, | 12,082 | 2,110,086 |

Page 16

| States of Europe. | Government. | Sq. miles. | Population. |

| Denmark. | Kingdom, | 21,856 | 2,468,713 |

| France, | Empire, | 212,341 | 36,746,432 |

| Frankfort, | Free City, | 39 | 79,278 |

| Great Britain, | Kingdom, | 110,846 | 28,888,597 |

| Greece, | Kingdom, | 18,244 | 1,067,216 |

| Hamburg, | Free City, | 135 | 222,379 |

| Hanover, | Kingdom, | 14,600 | 1,843,976 |

| Hesse-Cassel, | Electorate, | 4,430 | 726,686 |

| Hesse-Darmstadt, | Grand Duchy, | 3,761 | 845,571 |

| Hesse-Homburg, | Landgravate, | 106 | 25,746 |

| Holland with Luxembourg, | Kingdom, | 13,890 | 3,494,161 |

| Ionian Islands, | Republic, | 1,006 | 246,483 |

| Lichtenstein, | Principality, | 61 | 7,150 |

| Lippe, | Principality, | 445 | 106,086 |

| Lippe Schaumburg, | Principality, | 170 | 30,144 |

| Lubec, | Free City, | 142 | 55,423 |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin, | Grand Duchy, | 4,701 | 541,395 |

| Mecklenburg-Strelitz, | Grand Duchy, | 997 | 99,628 |

| Monaco, | Principality, | 12 | 7,627 |

| Nassau, | Duchy, | 1,736 | 443,648 |

| Oldenburg, | Grand Duchy, | 2,470 | 294,359 |

| Portugal, | Kingdom, | 34,500 | 3,568,895 |

| Prussia, | Kingdom, | 107,300 | 17,739,913 |

| Reuss, Principalities of | Principality, | 588 | 121,203 |

| San Marino, | Republic, | 21 | 8,000 |

| Sardinia, | Kingdom, | 48,026 | 11,029,219 |

| Saxony, | Kingdom, | 5,705 | 2,122,148 |

| Saxe-Altenburg, | Duchy, | 491 | 135,574 |

| Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, | Duchy, | 790 | 153,879 |

| Saxe-Mein.-Hilburgh., | Duchy, | 968 | 168,816 |

| Saxe-Weim.-Eisenach, | Duchy, | 1,403 | 267,112 |

| Schwartzburg-Rudolstadt, | Principality, | 405 | 70,030 |

| Schwartzburg-Sondershausen. | Principality, | 358 | 62,974 |

| Sicilies, The Two | Kingdom, | 41,521 | 8,703,130 |

| Spain, | Kingdom, | 176,480 | 15,454,514 |

| Sweden, | Kingdom, | 170,715 | 3,639,332 |

| Norway, | Kingdom, | 121,725 | 1,490,047 |

| Switzerland, | Republic, | 15,261 | 2,391,478 |

| Waldeck, | Principality, | 455 | 57,550 |

| Wirtemburg, | Kingdom, | 7,568 | 1,690,898 |

| Totals | 1,455,205 | 195,434,660 |

Now when we take into consideration the fact that England waged a war of more than 20 years against France to prevent the conquest of any of these governments, for the avowed purpose of maintaining the balance of power as it existed in Europe, and that she has since united with France to arrest the progress of Russia and to compel China to purchase her manufactures and furnish Coolies as slaves, it is not to be presumed that she will permit the United States to annex her American colonies, or that she will unite in the subjugation of the South. For as if the Union had been preserved and the same ratio of

Page 17

increase were maintained, it would give to the United States at the end of the next seventy years more than 255,000,000 of people, it surely requires no argument to satisfy intelligent minds that England will greatly prefer to foster and strengthen the Confederate States, not only because she prefers the creation of an independent government as a check upon the otherwise preponderating power of the United States, but because the failure of all their efforts to obtain a supply of cotton elsewhere must convince the manufacturers of England that our soil, climate and labor are best suited to its production, and if they do not purchase the raw material from us, we will become their most successful competitors in its manufacture. For the slaveholding States, including those to be formed west of Arkansas, will have a territory of more than 1,200,000 square miles, capable of sustaining a population greater than all the population of Europe, and as England and the other manufacturing States of Europe will be dependent on us for the supply of the raw material, so essential to their industry, it is to be hoped that the late success of our arms will induce the leading powers of Europe to unite in urging the acknowledgment of our independence, and that their interference will give us peace. If the war and the blockade continue, then, if the Confederate Government purchases the cotton crop and pays for it in Treasury notes without interest, that purchase and the expenditures of the war will give us an abundant and cheap currency to be employed in building up mauufactures; and availing ourselves of improved machinery, we can convert our cotton into yarns and cloths, and should the war continue for three years, we can then supply the increasing demand in Africa, India and China with greater profit than it can be supplied by Great Britain herself.

The estimate is that she has invested

| In spinning and weaving, | $326,250,000 |

| In dyeing and bleaching, | 150,000,000 |

| In transportation and purchase of cotton, | 47,500,000 |

| Making the entire sum which she has invested in the manufacture but, | $523,750,000 |

The war of 1812 caused large sums to be invested in manufactures in the Northern States, and if the war continues and we are prevented from exchanging our cotton for British manufactures, it will divert large sums into manufactures in the

Page 18

South. We will in that case be enabled to produce cheaper and undersell all competitors. We can raise our own food and thus we will have cheap bread. We can raise our own cotton and thus save the cost of transportation. We will be more than half way on the route from Europe to China, which is to become the chief market, and if England and France do not unite with us in coercing a peace, the shipping interests of the East and the manufacturing and agricultural interests of the Northwest will soon unite and give us a peace. If they do this and the Northwest be wise and becomes a separate government, as is more than probable, then if that section establishes proper commercial relations with us, it will become the seat of the richest manufacturing industry in the world, and receiving their supplies of the raw material and tropical products from the South, these two people will be bound together by interests stronger even than the late constitutional Union. In either case we should have our "Agency" to foster, promote and sustain our financial independence.

Do you not see in the manifestation of God's providence in the progress of the slaveholding States, that He has committed to them, as a chosen people, an important and peculiar trust, connected with the spread of His gospel? Did He not send the Huguenots to South Carolina, the Chivalry to Virginia and North Carolina, the Puritans to New England, the Quakers and Scotch Irish to Pennsylvania, and the Catholics to Maryland under circumstances which necessarily gave birth to the revolution, which created the United States? Did He not by the slave trade bring into the United States some 400,000 African slaves, who by their natural increase now number more than 4,000,000? Has He not permitted a false philanthropy and a false religion to bring the descendants of these Africans within the Southern States, where the climate, soil and productions give the best reward for their industry? Has He not fostered and developed the resources of these States, so increased their numbers, and so trained and educated our people that they have the strength, the will, the resources and the knowledge, aided as they manifestly are by His superintending providence, to assert and maintain their independence as a nation? Do you not see that the tendency, if not the inevitable consequence, of

Page 19

the pending war will be to give a unity of interest and of opinion and a consequent permanence to the government of the Confederate States, which, as their territory is sufficient to sustain a population of more than 200,000,000, must in a few years give them a numerical strength greater than any other of the civilized nations of the earth? For it is obvious that instead of having such a bond of union as our institution of African slavery gives to us, the rivalries and conflict of interests between the Eastern and Western States of the Federal Union will cause them to divide, like the governments of Europe, into many nationalities? Do you not see that the active and angry discussions of the questions of slavery and the tariff, which have so much absorbed the public mind for the last thirty years, were providentially interposed to unite us and prepare us, as a people, for becoming a separate and independent nation? Have you not seen that our President and Congress acknowledge that the strong hand of the Almighty has upheld our armies and given them the victories won on the field of battle? Do you not realize that the great heart of our people, of men, women and children, unite in one common sentiment of faith, gratitude and praise to God for these manifestations of His preference and protection?

Why is it that we, as a people, are thus made the special objects of God's providence? What is the trust committed to us and what its purpose? What is our peculiar characteristic as a nation? Is it not that we are the owners of African slaves and produce by their labor the greater part of the cotton, which forms the basis of that commerce which is so efficient an agency for the spread of the gospel? If I am correct in these views, (and who can doubt it?) then the Confederate States are to be the first and greatest of civilized nations, a people chosen in the providence of God, to whom He has committed in an especial manner an important part of that commerce which is, as it were, the wings upon which He sends His gospel to heathen nations? If this be so, and credit be as we have seen, so important and indispensable for the development of our industry and the extension of commerce, then such an organization and consolidation of capital as the proposed agency will create, is not only a financial necessity, but an indispensable christian duty. For if the war continues, it will give a safe and profitable investment

Page 20

of the notes and bonds of the Confederate States, and if we have peace, it will aid the direct trade to Europe, and so far as it may prevent an undue export of specie will sustain the credit of our banks and give stability to our currency, which will promote the employment and greater distribution of labor, which will secure our permanent prosperity.

The remarks on the proposed issue of Treasury notes submitted to the late Convention of cotton planters, and by them ordered to be printed, were intended to show that an issue of Treasury notes is the best form in which the loan to the Confederate States can be made. The statistics given demonstrate that, inasmuch as the Treasury notes are to be convertable into 8 per cent. bonds, the amount, which may not be so converted, will be of equal value with the bonds, and that as the bonds will be equal in value to gold and the notes may be converted at the pleasure of the holder, all beyond the sum required as currency will be so converted, and therefore the sum so required will not depreciate much, if any, below the value of gold and silver.

Those remarks were hastily thrown together, at the request of gentlemen of wealth, experienced in the cotton trade in New Orleans, and submitted to the Convention, imperfect as I knew them to be, because I believed their chief value to consist in the facts and statistics they gave, rather than in any suggestions or arguments of mine. I am sensible that finance and currency, involving as they do the progress and prosperity of civilized society, have been elaborately discussed by men of such ability and position that their opinions have assumed the weight of authority. Yet I do not hesitate to assert that there is scarce any subjects, affecting their interests, less understood by the great mass of the people. If the laborer or man of business can use a bank note as gold, he does not stop to ask what is its real value, but receives it as money because others will so receive it of him. This confidence in the value of bank notes is the result of habit, and rests chiefly on a fallacy, to-wit: a belief that the bank note is the actual bona fide representative of specie, and may at all times be converted into gold or silver coin. To prove that this belief is a fallacy, I refer to the Report of the Secretary of the Treasury, dated 26 March, 1860, which shows that the circulation of the banks of the United States, as exhibited

Page 21

by the returns to the Treasury Department, nearest to the

| 1 Jan., 1860, was, | $207,102,477 |

| Whilst their specie was but, | $83,534,597 |

It is obvious that the 83 millions of specie could not redeem the 207 millions of bank notes, and yet these bank notes were equal in value to gold and silver. Why so? The same report shows that the loans and discounts were $691,945,580. It is apparent therefore that what gave value to the $207,102,477 of bank notes, was not the $83,534,597 of specie, but the $691,945,580 of loans and discounts. It was not the specie held in their vaults, but the bills receivable held in their drawers that gave value to the bank circulation. Does not this show that the value of the bank note depends much more on the ability of those who are indebted to the banks to pay in bank notes what they owe, than it does on the specie in the banks? Say that there had been a run upon all the banks, and that the whole sum of $83,535,597 of specie had been taken by returning that sum in bank notes, it would have left in circulation $123,567,880 without any specie to redeem them. But to meet this circulation of $123,567,880 the banks would have held a demand against the public for loans and discounts of $691,945,580. Do you not see that if the public could pay the banks this balance of $123,567,880 in bank notes, there would still be a balance in favor of the banks of $568,376,700, less their deposits; and that if required to pay up their entire deposits, there would still be a balance in favor of the banks of $314,586,577 to be paid in specie, for they held--

| Loans and discounts, | $691,945,580 | |

| Specie, | $83,534,597 | |

| $775,480,177 | ||

| Their circulation was but, | $207,102,471 | |

| Their deposits, | 253,802,129 | |

| $460,904,600 | ||

| Leaving balance due to the banks, after paying bills and deposits, | $314,586,577 |

But we have seen, on the authority of Mr. Colwell, that in 1857, the banks of New York, with $12,000,000 in specie and but 8,000,000 in circulation, had 95,000,000 of deposits, showing that a very large part of the deposits were credits given by the banks to their customers, and that instead of representing debts due by the banks to the public, the deposits represented to a great extent credits given by the banks to facilitate the movement of commodities, which credits were adjusted daily

Page 22

by exchanging them at the clearing house, and therefore were not, as many supposed, a specie demand against the banks.

Does any one ask why, if such be the condition of the banks, their notes depreciate, and why they are compelled to suspend specie payment? I reply that the banks suspend, not because of any depreciation of their notes, but because they are unable to redeem them in specie, and that they are unable to pay specie to the public, because the public are unable to pay bank notes to them. The Bank note is used as a substitute rather than as the representative of specie, and the banks suspend paying specie, because the demand for bank notes, resulting from some political or financial derangement of the monetary system, is such that they cannot be otherwise supplied in requisite quantities. The purpose of the suspension therefore is to enable the banks to supply the public with an increased quantity of bank notes, which they could not do, if they continued to pay specie. Thus the Bank of England suspended payment in 1797, because she could not otherwise supply the bank notes requisite to carry on the war with France, and the banks of the United States suspended in 1812, because they could not otherwise supply the bank notes requisite to maintain the war with England, and having partially resumed, they again suspended, because the Bank of the United States, chartered for the avowed purpose of aiding the process of resumption, became the agency through which the merchants of England absorbed and remitted to England the specie of this country preparaty to the resumption, in 1825, of specie payments by the Bank of England. They again suspended in 1837, because Parliament, having emancipated the West India slaves and abolished the monopoly of the East India Company, placed in the Bank of England $100,000,000 to pay the West India claimants, and some $25,000,000 of the commercial assetts of the East India Company, which being loaned by the Bank to the money dealers of England, inflated the currency at least 50 per cent. and caused the wildest speculations in Mexican and South American loans and mines and other visionary projects. When required to pay the large sums due to the West India claimants, the demand for specie was increased by an extraordinary demand for foreign breadstuffs and by the transfer of the public deposits from Mr. Van Buren's pet banks to the State Treasuries and the consequent specie circular, intended to sustain the pet banks, which had become

Page 23

largely indebted by speculations in the public lands. As the banking system of the United States was a part, and the weaker part, of the British system, their banks were compelled to suspend, because the export of specie to London under the pressure of the Bank of England, was such that they could not otherwise supply the requisite quantity of bank notes to the people of the United States. Again in 1857, the demand for silver to pay the expenses of the war in India was such that the Bank of England, by a turn of the bank screw, caused such an export of specie from New York, that the banks of the United States were compelled to suspend, not because their notes were depreciated, but because they could not otherwise supply the people of the United States with the requisite quantity of bank notes. And again, the banks in the Confederate States have suspended, not because their notes have depreciated, but because they could not otherwise aid the Confederate States with the funds requisite for the maintenance of the present war. Is it not proved that the idea that a bank note should be at all times convertable into specie is a fallacy? Is it not proved that the test of the value of a bank note is its use in the purchase of commodities and the payment of debts? Does it not represent credit rather than specie, and if the credit represented by bank notes may be made available as a currency, equal to specie, may we not give to the Treasury notes equal value as currency?

I admit that the value of specie may appreciate; but I deny that the notes of well conducted banks depreciate, and more especially in time of panic; for then, to use the words of an intelligent director of the Bank of England before a committee of Parliament, "it is not specie, but more bank notes, that is wanted." This is proved by the fact that the bank notes are then more difficult to obtain, and will purchase more of other commodities than in times of financial prosperity. A general suspension of the banks is the consequence and not the cause of a financial crisis. This is proved by the fact that scarce any property will sell for as much now, payable in the notes of the suspended banks, as the same could have been sold for before the suspension, payable in the notes of the same banks.

There is another circumstance which gives increased value to bank notes. The demand of the public against the banks, (to wit, their circulation and deposits) is payable at uncertain and distant periods, whilst the demands of the banks against the

Page 24

public, (to wit, for loans and discounts,) is certain and at short dates. The public, therefore, is required, in payment of their dues to the banks, to deliver either bank notes or specie; and as the sum of bank notes in circulation is so much less than the sums due the banks, the continuous and repeated demand for bank notes to pay dues to the banks, maintains their value, without reference to their redemption in specie. This feature of the banking system is important in considering the effect which a large issue of Treasury notes, to be used as currency, will have on the interests of the banks. It is known that the profits of banking are greatest when money is most abundant, and if Treasury notes should be substituted for bank notes as currency, the effect must be that the debtors to the banks will pay them in Treasury notes instead of bank bills. In such case, the banks will have the Treasury notes, with which to redeem their own notes, or to be loaned to their customers as money, and their profits will be no less than if the payments had been made in gold and silver; for in that case, the only use they could make of specie would be to redeem their circulation or to lend it to their customers, and if the banks can use the Treasury notes as specie, the value will be the same as specie. We accordingly see that the banks unite in advising an issue of Treasury notes for $100,000,000, in addition to the issue already authorized; the smaller denominations to be without interest.

I argue that as the notes are convertible into Bonds, the question to be considered is not so much what sum may be issued without interest, as what sum may be advantageously used as currency. The estimate must be conjectural; because we have seen that with a circulation of $8,000,000 only, the daily bank settlement at the Clearing House in New York were $30,000,000; and that whilst the average amount of money (bank notes and specie) used in the operations of trade in England and Wales from 1846 to 1856 had diminished nearly eight millions of dollars, the annual average increase of bills of exchange amounted to $90,000,000, and that there was at one time in circulation $900,000,000 of such bills!!! The sum of Treasury notes, which may be substituted for bank notes, specie, bills of exchange, and other modes of credit, can only be ascertained by the test of experience. But we may refer to the fact that the circulation of the banks of the United States, as given above, was $207,102,477, and that this sum was required when

Page 25

--as we have seen--the whole movement of the cotton crop, equal to $200,000,000, was made by the use of foreign credit, to show that the sum required as currency in the Confederate States may be much greater than the issue of bank notes, when they were part of the United States. How far Treasury notes or Confederate bonds may be substituted for the foreign credit used in the movement of our exports, is a question worthy of the deepest consideration.

It has been suggested that the Bank of England should remit their post notes, payable twelve months after date, for the purpose of purchasing the entire cotton crop; and this proposition has been favorably received in influential quarters. The whole capital of the Bank is but $72,675,000, of which $70,000,000 is invested in 3 per cent. consols. As the Bank is forbidden to issue its notes for more than the sum of the bullion in its vaults in addition to the capital thus invested, the sum which it is authorized to issue depends on the bullion it may have, and is therefore uncertain and would be seldom, if ever, equal to the value of the crop. Those who make this proposition must be ignorant of this provision, or must contemplate an amendment of its charter for that purpose. But one single fact is, of itself, a conclusive answer to this suggestion. The Bank of England derives its profits from, and is the chief agent of, British commerce, which rests upon British manufactures. It is not to be presumed that the planters of the South will place the control of their cotton with an Institution so much identified with the British manufacturer; for it will be manifestly the interest of the Bank to reduce the price in the British market, which will necessarily regulate the price in this.

Again, I do not suppose the proposition contemplates that the Bank of England shall, itself, become the purchaser of the cotton, but that the post notes shall be loaned to individuals, who may become the purchasers. The objection is no less valid--for as none could purchase without a credit in the Bank of England, the effect would be to place the control of the cotton in that Bank, which is interested in maintaining the commerce, credit, and prosperity of England, and controlled by persons who have formed associations for the avowed purpose of promoting the growth of cotton elsewhere, in preference to its production by us.

Again; If this were not so, we have seen that whilst the

Page 26

government of England has placed more than $4,000,000,000 at 3 per cent., and the Savings Banks hold more than $170,000,000 of deposits at less than 3 per cent., the interest charged by the Bank of England fluctuates from 2 to 10 per cent. I trust it will require no argument to satisfy the planters of the South that it will be most unwise to place the control of the price of their cotton with any foreign agency whatever, and especially such an agency as the Bank of England is. That Bank is the financial agent of the government, as well as of the merchants and manufacturers, of England, and having its capital invested in consols, it may be said that its resources depend entirely on its credit. With a capital of $72,675,000, seventy millions of which is invested in a debt never to be paid, and the real value of which is the annual interest (or $2,100,000 per annum), aided by the regulation which gives them a control over the credit of the government, and brings the commerce and manufactures of England under its supervision, the Bank of England may be said to be charged with the duty of so regulating the commerce and the currency of England as to make the commerce of the rest of the world subservient to the welfare and the progress of England. The wisdom of the measures and policy of the Bank have been the subject of much controversy in Parliament and in the press; and many able essays have been written to prove that the theory that the bills of the Bank are and should be the actual bona fide representatives of specie, is a fallacy. The system of finance and of credit has been progressive; and the concessions to the Bank, resulting from the fallacy that gold and silver are the only safe and legitimate representatives of bank credit, have given to the Bank of England the power which it exerts over the credit and currency of England, and of all other countries holding extensive commercial relations with England. The process by which the Bank exerts its power is illustrated by two Diagrams, prepared from a manuscript memorandum and a published exhibit taken from more than four thousand returns of the Bank of England, given to me in 1857 by Mr. Edward Hazleword, a London banker, which will be found on the opposite page.

Seventy millions of dollars of the capital of the Bank is invested in consols, and it is authorized to issue this sum in bank notes. It is also authorized to issue bank notes, in addition to this seventy millions, equal to the sum of bullion in its vaults;

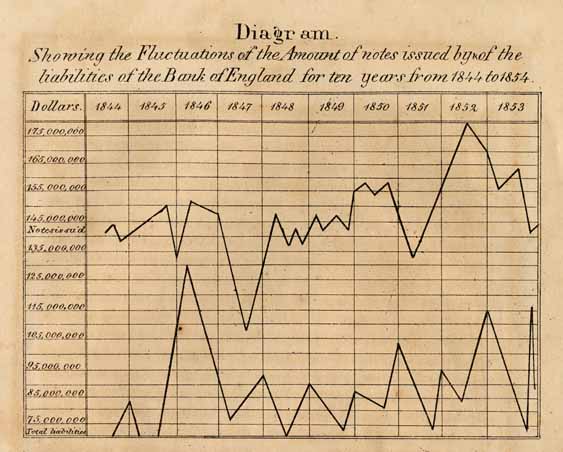

Diagram.

Showing the Fluctuations of the Amount of notes issued by & of the liabilities of the Bank of England for ten years from 1844 to 1854.

Diagram

Showing the Fluctuations in the rate of interest charged by the Bank of England as regulated by the Amount of bullion in its vaults the figures in the margin representing the bullion in millions of dollars (from $35,000,000 to $100,000,000) and the irregular lines indicating the rates of interest.

Page 27

thus, by reference to the first diagram, it will be seen that the perpendicular lines represent the years from 1844 to 1853, inclusive, and that the notes issued in 1852 amounted to $178,000,000--that is, $70,000,000 on account of the capital invested in consols, and $108,000,000 on account of the bullion in its vaults; by turning to the second diagram, it will be seen that figures on the margin represent the sum of bullion in the Bank in millions of dollars, and that as in 1852 the bullion was $108,000,000 the issue was $178,000,000, and the rate of interest was but two per cent., whereas in December, 1857, the bullion in the Bank was but $35,000,000, and the rate of interest was ten per cent.

Does any one ask how this fluctuation in the rate of interest charged by the Bank of England, can affect us or our banks? I answer that our banking system is but a part, and the weakest part, of the British system, and rests upon the same fallacy, to wit, the idea that gold and silver is the only safe basis of credit and currency. This I have proved by the analyses of our banks and their assets; and all who have studied the effect of the contractions and expansions of credit and currency by the Bank of England, know that the effect of a low rate of interest in England is to inflate the currency and increase the values of property, and that the effect of a high rate of interest is to render money scarce and depress the values of property; and that this contraction and expansion by the Bank of England acts on us, through our banks, because the purpose of the Bank of England is to throw upon the commerce of England the onus of bringing back to its vaults the requisite quantity of specie, and that therefore our merchants, who may buy British goods under the expectation that a fund may be created, by the sale of our cotton in Liverpool, which will enable them to buy a bill upon London to pay this debt, may find that the cotton cannot be sold; or, if sold, it has been at such a depreciation that they will be compelled to obtain the specie from our banks to be remitted to London in payment of this debt. The effect of taking the specie from our banks, is to make bank notes as well as specie scarce and dear with us, and we are thus made the victims of the contractions and expansions of the Bank of England, which regulates, at pleasure, the condition of our banks, and will continue to do so as long as our banking system rests on

Page 28

the same fallacy of paying specie, and remains the weakest part of the British system.

The only remedy--the only protection, which we can have or hope for, is in a large issue of Treasury notes by the Confederate government, convertible into Confederate Bonds bearing such a rate of interest that, whenever the issue of notes may exceed the sum required for currency, the excess will be converted into Bonds. Thus the demand will regulate the quantity of notes used as currency; such a currency will not be convertible into specie, and therefore will not be used to take the specie out of our banks to be sent to the Bank of England, but it will be equal to specie for our domestic use; for the provision that the notes may be converted into Bonds and that the Bonds may be converted into notes, will so regulate the quantity of our currency as to prevent any depreciation of the values of our property and enable the planters, the values of whose annual exports will soon be more than three hundred millions of dollars, to create an agency by investing a part of the proceeds, which can place their crops in the foreign markets, and protect their value against the depreciation which must be the frequent recurring consequence of a dependence upon the banking system of England, or of the Confederate States, so long as that system pretends to rest on a specie basis, and is subject to be regulated--as it must and will be--by the Bank of England.

Yours truly,

DUFF GREEN.

Return to Menu Page for Facts and Suggestions on the Subjects of Currency... by Duff Green

Return to The Southern Homefront, 1861-1865 Home Page

Return to Documenting the American South Home Page