The Southern Spy.

Letters

on

the Policy and Inauguration of the Lincoln War.

Written

Anonymously in Washington and Elsewhere:

Electronic Edition.

Edward Alfred Pollard, 1831-1872

Funding from the Institute of

Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this

title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Elizabeth Wright

Images scanned by

Elizabeth Wright

Text encoded by

Joshua McKim and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 150 K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Call number 2824 Conf. (Rare Book Collection, UNC-CH)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project,

Documenting the American South.

All footnotes are

inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as --

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using

Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

LC Subject Headings:

- United States -- Politics and government -- 1861-1865.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Causes.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Public opinion.

- Secession.

- 2000-05-03,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-08-31,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-08-22,

Joshua McKim

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-08-15,

Elizabeth Wright

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

Page 1

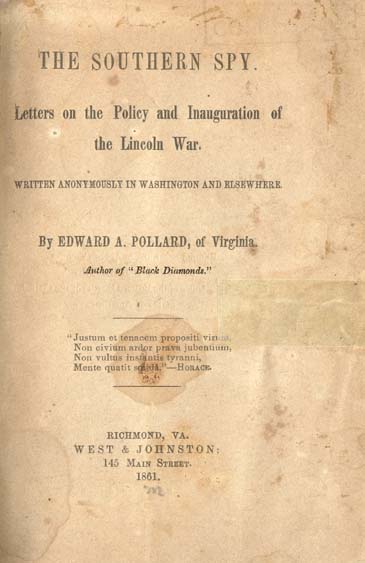

THE SOUTHERN SPY.

Letters on the Policy and Inauguration of

the Lincoln War.

WRITTEN ANONYMOUSLY IN WASHINGTON AND ELSEWHERE.

By

EDWARD A. POLLARD, of Virginia.

Author of "Black Diamonds."

"Justum et tenacem

propositi virum,

Non civium ardor prava

jubentium,

Non vultus instantis

tyranni,

Mente quatit

solida."--HORACE.

RICHMOND, VA.

WEST & JOHNSTON:

145 MAIN STREET.

1861.

Verso

Entered according to Act of Congress,

BY WEST & JOHNSTON,

In the Clerk's Office of the Eastern District of the Confederate

States of America.

MACFARLANE & FERGUSSON, PRINTERS.

Page 3

PREFATORY.

The author of these letters, once a Union man, as long as there was a prospect of acquiring and maintaining the constitutional rights of the South in the Union, and of realizing a hope of Christian peace and charity therein; once averse, on politic grounds, to the early movements of secession, as offering a violent resource for what he then hoped might be moderately remedied, sees that Union now affected to be maintained by a despotism, and the former issue of secession now converted into one where the right of self-government is on one side, and a war of despotism, usurped powers, compulsory purposes and wanton atrocities is on the other.

In the essential alteration of the issue, he can only be for the independence of the South, when it is no longer to be treated by its opponents on moral and constitutional grounds, but to be contested by a despot's war; and against that war and that despot, who has murdered the peace of his country, he acknowledges all the feeling of opposition that a true and patriotic and justly indignant spirit may offer for the vindication of the right.

To vindicate the now rightful spirit of the South, and to strip despotism to its nakedness, he has written the following letters, which he hopes to continue for good. If there are harsh expressions to be found in them, it is sufficient to say that he has regretted the necessity of speaking harsh words of harsh things; and that he will be satisfied to repent the use of censure and sarcasm as untruthful, unchristian and unmanly, only when they are proved to have been undeserved.

NEAR WASHINGTON CITY, July, 1861.

Page 5

SECOND EDITION.

A portion of the first edition of this volume, published in Maryland without the name of the author or printer, was sold in that State and in the District of Columbia--as many as one hundred having been sold in one day, by a single dealer, in the city of Baltimore. The largest portion of the edition was, however, suppressed and destroyed by the author himself, under personal constraints of necessity.

In offering a renewed edition of these letters to the people of the Confederate States, the author claims for them, aside from any personal interest, with respect to the parties to whom they are addressed, some value as related to the historical literature of the war, particularly in exposing the circumstances of its inauguration, and the policy which has conducted it from its beginning to the full and precise declaration of its objects. The volume of letters, from the fall of Sumter to the date of the meeting of the last Congress at Washington, completes, in fact, what is the most important, because the initiatory part, of the history of the war.

RICHMOND, VA.,

November, 1861.

Page 7

INDEX.

- I. Letter to President Lincoln, written at Washington,. . . . .9

- II. Letter to President Lincoln, written at Washington,. . . . .17

- III. Letter to President Lincoln, written at Washington,. . . . .26

- IV. Letter to President Lincoln, written near the Government,. . . . .33

- V. Letter to the Editor of . . . . . . . , written in Maryland,. . . . .44

- VI. Letter to Secretary Seward, written in Maryland,. . . . .52

- VII. Letter to President Lincoln, written in Maryland,. . . . .63

- VIII. Letter to Doctor Tyng, written in Baltimore,. . . . .75

- IX. Letter to General Scott, written in Maryland,. . . . .85

- X. Letter to Mr. Everett, written in Maryland,. . . . .89

Page 9

LETTERS OF THE SOUTHERN SPY.

I.

LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT.

WASHINGTON CITY, D. C., APRIL 13, 1861.

To the President of the United States:

SIR: Permit me to address you respectfully, but none the less earnestly; for neither the magnitude of the events which happened this day, nor the thoughts of a freeman's patriotism at any time, can be satisfied with expressions concealed or softened, except to that point of respect due to magisterial office.

I can testify to you, sir, my poignant regrets, as a lover of my country, and even as a Christian lover of peace, at the collision at Sumter. But these feelings are not without a reference of my judgment to where the responsibility for the actual commencement of hostilities may lie; though it may be that recriminations cannot lessen the force

Page 10

of patriotic regrets, or control the consequences of what is already accomplished. I am aware, sir, that the belligerent supporters of your Administration counterfeit a sense of satisfaction in the plea of the government acting on "the defensive" --a plea which you yourself have again affirmed to-day in your reply to the Virginia commissioners. Unfortunately for you, sir, the plea is weakened by the force of the circumstance that the Government, in the first instance, might have avoided a conflict, and that the real responsibility reaches back to the threshold of the controversy. The policy of war has been determined, necessarily determined, not by the bombardment of Fort Sumter, but by earlier events, that plainly and voluntarily led to this result and furnished its provocation.

I should suppose, sir, that when a party does what he knows to be a sure act of provocation, it is quite equivalent to the first blow, on the principle, which is familiar to small lawyers, if not to statesmen, that a man intends the natural (and still more strongly, if anticipated) consequences of his acts.

The country will explore the source, and therefore

Page 11

the real seat of the responsibility. It will look back to the primary cause of war, without resting on those secondary events which have no responsible character in themselves, because determined, procured, and looked for in the very outset of the policy of which they are the fruits.

It cannot be doubted, sir, that you procured the battle of Sumter; you had no desire or hope to retain the fort; you neglected to fight, until every chance of doing so with success had passed away; and when at last you did draw your sword against the sovereignty of South Carolina, the circumstances of the battle, the non-participation of your fleet in it, show that it was not a contest for victory, but only a shallow trick to entitle you to the advantages to be derived from an action for assault and battery. It was, sir, a trick--a trick to transfer easily, and under false pretences, the matters in dispute between the two sections from the arbitrament of reason to that of arms. How is it that you hope to make yourself not responsible for this unnatural and shocking appeal to war? Was not your formal intimation to the Montgomery Government that you were about to resort to force, a challenge to arms? Could the

Page 12

South have been expected to disregard such a challenge? Or, if, sir, you were only amusing yourself with idle menace, are you any the less culpable because you excited a quarrel by bullying instead of bravery? Your responsibility for the commencement of hostilities, sir, is already a historical fact, and completes the character of your policy as one of blunders, perfidy and bloodguiltiness.

Had you, sir, acknowledged the independence of the seceded States--acknowledged it for purposes of pacification--you might have accomplished what war cannot only never obtain for you, but of what it will surely rob you. You might have kept the support of the intelligent and commanding portion of your party. You would certainly have secured the sympathies of the border States, You would have erected a standard under which the masses of Union men in the South, who never could be expected to rally under a standard of war, could have served to a man. You would have reduced the excitement that threatened the Government to channels leading to the happy and naturally aided restoration of peace.

Page 13

Now, "all is lost, save honor"--not honor as the knightly King who wrote the phrase intended it, but "the honor" of having "acted under the forms of the Constitution" in a fratricidal war! The government that, in the broad and liberal enlightenment of modern times, seeks to administer constitutional and public law on a policy of punctilios, is none the less behind the age, whether in Central Europe or on the shores of the Atlantic. The advisers of such courses of statesmanship have not read the lessons of history aright--not even the latest. You yourself, sir, must have forgotten the lessons even of the Italian war. You forgot that the kingdom of Italy has been ushered so lately into existence through the very teeth of the treaties of Vienna. You forget that Austria has reaped the fruits of the policy recommended to you, and found them, to her cost, in insisting on the punctilios of those treaties--the most boasted part of the "public law of Europe"--to maintain a "war footing" in her Italian possessions, and in losing them by the very effort to make her authority more secure.

Look to our own war of independence. Those who have despised and declaimed against the

Page 14

policy of an acknowledgment, or even a quasi acknowledgment (no matter what the guise or the purpose) on the part of your Government of the independence of the seceded States, forget the history and traditions of those times. The policy referred to does not present the specious question, as they would have you, at least, if not the country, believe, of governmental honor or dishonour-- certainly no more than the acknowledgment of the independence of the American colonies, advocated by a portion of the Whig party, presented the alternative of honor or dishonor to the British Crown. Do you suppose, sir, that Pitt and his noble coadjutors were any the less Englishmen, or patriots, or statesmen, for having attempted to resist the unnatural and unprofitable war which the British government was preparing to make upon the seceded colonies? Or can it be said in this day (although it possibly might have been said formerly by tory papers) that when Lord Effingham and the eldest son of the Earl of Chatham threw up their commissions in the army rather than serve in a war against their colonial brethren; and when General Oglethrope refused the splendid bribe of the office of

Page 15

commander-in-chief of the British forces against America, that they acted in a traitorous or ignoble spirt, or bore the taint of cowardice upon their names. For myself, I believe that these examples of generosity, of far-seeing patriotism, patient under insults and clamor and misrepresentation, may give the most proper lessons to the captious and belligerent "patriotism" of our own day. Had Great Britain rightly observed them, she would have saved herself the blood and treasure of a seven years' war. Would that she had listened to the appeals of the colonies, when they declared, through the Continental Congress of 1775, that""they had not raised armies with the ambitions design of separating from Great Britain; and that they should lay their arms down when hostilities should cease on the part of the aggressors, and all danger of their renewal should be removed!" She did not listen, and she drove them into independence. Be assured, sir, that your Government has yet to have the lesson enforced upon it, that the spirit of independence, misconceived or not, is but developed by war, with the unavoidable circumstance of insisting, at each stage of its progress, on new and

Page 16

further demands, when the first movements might have well been held in check by the simple energy of patience.

Respectfully,

THE SOUTHERN SPY.

Page 17

II.

LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT.

WASHINGTON CITY, D. C., APRIL 16, 1861.

To the President of the United States:

SIR: Your proclamation of war is before the country; and the spirit that dictated it is already caught up in the revengeful exultations of Black Republican presses over the prospect of blood. I say blood, sir; for however you may gainsay it, or jest about it, it is the curse of fratricidal blood that you have pronounced, distinctly and irrevocably. I say jest, sir; for surely you did but jest, when you said in your inaugural that you would take the forts and arsenals (like Shylock's pound of flesh) without a drop of bloodshed; and you did but jest, when, with the cannon peals of Sumter on the air, you protested to the Virginia commissioners that you would modify your inaugural, only so far as to "perhaps cause the United States mails to be withdrawn" from the seceded States; and you do now but jest when mustering

Page 18

to fields of civil war a land force of seventy-five thousand men, you yet proclaim that the places of the government only are to be repossessed, and that "the utmost care" is to be taken to "avoid any devastation, any destruction of or interference with, property, or any disturbance of peaceful citizens in any part of the country!" Alas, sir, have you nothing better to offer to an agonized country than the same flimsy and harlequin disguises of the trifler, with which you tricked yourself out for the entertainment of the crowds of idlers that watched your progress to the capital? Nothing very terrible to happen-- no devastation--no disturbances, and yet an army of seventy-five thousand men called to your command for service on land, and the most monstrous proportions of civil war already erected in staring ghastliness over the whole country! Sir, this is not ingenuous--it is not appropriate--it is, I tell you, sir, the trifling of the jester in the Chamber of Death!

So far as the legal aspects of your proclamation are concerned, you have violated the laws in the very appeal you make to them. You have usurped the power of Congress to declare war.

Page 19

You have called out the militia, not as the act of 1795 (which the law adviser of your government has vainly sought to distort for your purposes) indicates, in aid of the civil authorities, but to supersede them, and to inaugurate war in its most deformed nakedness. You have attempted, too, to make the militia of this district subject not only to the rules and articles of war in point of discipline, which is the legal limit of your authority, but to denude them of the character of citizen soldiery, to swear them by oaths to your person, and to constitute them into prætorian bands. This may be military genius, and decision; but to a plain man it seems like military despotism. A war begun and invoked in the name of law, and yet disregarding the law even in the ceremonies of its inauguration, promises nothing but shame and disaster.

But suppose, sir, that the most unbounded success should attend your arms; suppose you should heap up the most immense treasures of victory and blood, where, after all, would be your gains? You cannot reclaim sovereign States, except as conquests; and as conquests, they would be to you worse than useless.

Page 20

Why, then, sir--and the question is very simple-- make that an occasion of war, where war would be unnatural, and in the end, wholly unprofitable? Even when a government is an empire, instead of a confederation, there may be occasions where the acknowledgment of the independence of a seceded province, even, resolved on independence, may be policy, and statesmanship, and patriotism. Is it any the less so now than when Great Britain was besought by her best patriots to restrain herself from war upon her American colonies, and to concede their demands. You, sir, and your party, profess to believe the South a spotted and degraded section, doing dishonor to the name and position before the world of what was once our common country. Why, then, seek to reclaim these people to your intercourse? Why pursue them in their retreat? Pharoah attempted to reclaim the hated Israelites, that they might not go out of the land of Egypt. But, mark you, he sought to reclaim them as slaves!

Is, sir, your own heart surely hardened like that of the Egyptian king? Let me remind you, sir, if not, perhaps, a student of your Bible, of the outlines of that awful drama by the Red sea. It

Page 21

was there, on the boundary of battle, that Moses spoke to his countrymen, who cried in their fear to return to the land of bondage, and, in the clear heroic terms of his own towering faith and courage, gave the command: "Fear ye not, stand still; for the Egyptians whom ye have seen to day, ye shall shall see them no more forever!"

You have appealed to the issues of war! Let those issues, then, decide! When the reason and the better feelings of a man, or even a "President," are stifled, it will be useless to preach to him even the lessons of the Bible.

The fact, sir--the fact which, at once, reveals the infamous desire of the war you have inaugurated and the immensity of the prize in issue for the South--is that that unhappy section has been used to contribute the bulk of the revenues of the government, to build up the North, and to enrich her enemies by every form of tribute. The Northern plutocratic power would have it continued so. It would still derive its forty to fifty millions of annual revenue from the South, through the operations of the tariff; it would, still, batten on the Southern trade in its markets, a recent aggregate of which is stated at four

Page 22

hundred millions of dollars a year; it would still, from unequal taxations, and different sources of tribute in the intercourse between the sections, reap its immense harvest of gain, which a Northern writer has calculated at over two hundred millions of dollars per year, and which, sir, represents the annual aggregate tax or cost of the "glorious Union" to the South.

It is this prize, wrapped in the pretences of Stars and Stripes, for which you will contend; and believe me, sir, it is, for this also that the South will press its war, and out of which it can afford to pay the extremest expenses of that war.

You, sir, now, after the elaborate illustration of your traits of statesmanship, will have the advantage of showing other resources of your extraordinary character, and of exhibiting, what you are said to possess, the splendid stores of your military genius. You have commenced well, sir. You are a stern master--a most excellent military ruler. You are already a Nero in your own capital.

I congratulate you upon your almost perfect establishment of military terrorism over a parasitical

Page 23

city. You have filled your capital with troops. You have set up a political inquisition in Washington, by the process of military TEST OATHS, wringing from men's consciences all that is precious to men's freedom. You have opened markets on the green in front of the War Department to buy of starving men in your capital, for soldier's pay and rations, their bodies, and principles, and consciences. You have surrounded yourself with every element to inspire terror around you. Your minions and your parasites are this day hunting through the streets of Washington, to do violence, by threats, at least, to every man who dares to oppose your Administration. And, for the first time, and, as I firmly believe, for the last time, in the history of our country, a Government, still holding on to the old name and the old traditions of our national independence, is striving to cow under the very shadow of the capital--the ancient mansion of American liberty--the ancient freedom of sentiment and of utterance.

But, sir, beware! The terrorism is not yet complete in your capital. It is true that many of those, who, when danger was distant, were

Page 24

loudest and bravest in the censure of you and your party, are satisfied now to sneak around the streets of Washington, anxious to play the part of "hen hussies" for the women and children, speaking with "bated breath," or pleading new scruples for submission, with the slime of their cowardice tracking them through the crowd. But let me assure you, sir, that there are in the midst of your federal city men of a different character and purpose--men who know their rights--and men who rejoice with more than Roman pride, that whether they stand on a foreign soil, or beneath the folds of their seven-starred banner, they stand as free citizens, under the protection of their own free republic. You will not subdue them. You cannot coerce them. You will be sorry to touch a hair of their heads.

Take care, too, that the terrorism you have established in Washington does not react upon yourself. Do not tremble for your person, sir! I do not mean that. But I do warn you that the reign of terror, already inaugurated in Washington, stands, this day, as a despotic example before the country; that revolt may soon stand you, face to face, in your capital; and that the time

Page 25

may come when Washington, oppressed and crushed down by tyranny, and beleaguered by armies, fresh from fields of victory, will have nothing to oppose to them but the wretched bodies and vagabond uniforms of starving janizaries. Then, sir, tremble--tremble!

The splendid and chivalrous Roman Tribune, that founded the latter Rome, consented to escape from the throne of the Cæsars in the disguise of a baker; but it was only when the walls of his Capitol were falling around him, and the sounds of its ruins was already in his ears. Will you, sir, wait until then?--or will you, with nerves already shattered by your midnight escapade to the shallow refuges of Washington, choose to escape now?

I am, &c.,

THE SOUTHERN SPY.

Page 26

III.

LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT.

WASHINGTON CITY, D. C., APRIL 20,1861.

To the President of the United States:

SIR: In one sense, I must congratulate you: in another, permit me to express my pity for you.

The masked author of "Junius" tells us that the counsels and expedients of party, rather than higher principles of policy, determined for England the war upon her colonies; and that the procurers of this war, while intending only the ruin of an opposition in parliament, "in effect divided one-half of the empire from the other."

A victory, sir, culminating in such grand historical results, you, yourself, have just illustrated. The time has come when it is clearly seen that you have done your strictest duty to your party. A simple man, possessed only of that degree of intelligence that may be expected to be acquired in the contracted and vulgar life of a Western village, you have conceived no vain ideas of

Page 27

statesmanship above the integrity of "the Chicago platform," and have disdained all counsellors beyond your associations with "the thorough" Republicans of your party. In the spirit of fidelity to party, you have determined the issue of war for your country. You know very well that the Union is peace; that you cannot establish it by arms. You know very well that glory is to be wrested only from a foreign enemy; and that it is never to be purchased from the victories of a civil war. You have made war, sir, neither for the reparations of evils, nor for the glory of arms. You have made it at the command of a political party resolved "to rule or to ruin."

Enjoy, sir, the felicities of your situation. You have obeyed the behests of your party: hasten to prepare yourself for their servile congratulations. The men who have hurried you to the exploit of war, will not spare their praises. The vile priest of the Abaddon, who prays his god for "war redder than blood," will set you up as an idol among the demon glories of his religion. The mobs will cry "Hosannah." Even the ken-marked and hobbling wretch, who edits the great organ of Abolition for your party in the North, will exhaust

Page 28

himself to spew over you his clotted praises, as if in some sort of beastly adoration of your person!

But, sir, let this be the limit of your rejoicing. The Union is lost forever. The jewelled States of the South are lost to you, and gained for Independence forever. A war confronts you to proclaim that independence in your ears, and to drive you, with denuded crown, from the soil that it is about to consecrate to the eternal liberties of the South.

"His majesty," said the great commoner, prophesying the liberty of the American Colonies on the floor of parliament--"his majesty may wear his crown, but, without the American jewel in it, it will not be worth wearing."

It is said that you are even already alarmed for the safety of your person, on account of circumstances daily surrounding you to make you a prisoner, in spite of Northern succors, in your own capital. I pity you, sir. I might have told you, months ago, that the South had no fear of any war you might make, and that the effort of your proclamation to frighten her people, and even your twenty days' grace to "the combinations"

Page 29

would not strike the sudden terror or submission in their hearts that you anticipated. You may satisfy yourself with a short-lived tyranny, with desultory atrocities, with a display of arms; but, plainly, sir, you are not the man to sustain a war in the nineteenth century, in the interest of an usurped government, and in opposition to a people, resolved to take their own destinies into their own hands.

I am glad for the sake of my country, sir, to be satisfied on reflection that the war you will wage will be contracted in its powers beyond what you anticipated. It is said that you have abundant offers of Northern succor; that twenty thousand men in the coalpits of Pennsylvania, alone, have offered you their services; and that you even boast of your opportunity to introduce a religious element to exasperate the war, by hiring German Protestants, "to a man," and animating them against the true and steadfast Catholic patriots of the country. But, sir, all these are but the boasts of a weak cause--the rhodomontade of the streets of Washington. Be pacified, sir. Your Dutch troops will find employment enough in guarding the passes of the Long Bridge, and in poking

Page 30

bayonets at half-breeched newsboys about the Departments, without entering upon the task of a massacre of the Irish.

Look, sir, to the South. Are we to believe that your proclamation, received in Montgomery with derisive laughter, scorned by North Carolina and Kentucky, with all the speed with which the lightning of the telegraph could bring their messages of defiance to you, thrown back in your face by Virginia, with the treatening stamp of her foot already on the banks of the Potomac-- can even you, sir, believe that this mighty proclamation has subdued one throb of Southern courage, or subtracted one man from the lists of her cause of independence! No, sir, it has multiplied them. Your effort to alarm the South has only alarmed yourself. Your collection of Northern troops, numerous it may be, but unanimated to fight by any of those sentiments, which give victory in battle, has but given new accessions and new ardors to a people fighting for their liberties, and possessing all that confidence, and all those great moral principles of victory inspired by a war of independence.

I thank God, sir, that my own native State,

Page 31

Virginia, is, this day, not listening to the time-server. What her Convention may determine I know not; but I know that her lineal people will, ultimately determine nothing to the dishonor of their glorious State--nothing in the shallow spirit of cowardice, or of mean compliance with present power. Virginia will not listen to counsels conceived in such a spirit. She will listen, let me assure you, sir, to higher sources of inspiration than your own--to the voices of her history--to the commands of her mission--to the thunder-toned messages that, commenced at Sumter, will soon peal around the peninsula of the Atlantic. Break the unity of the South! She never will. Fold her arms with wailing cries of "peace!" She never will. Take argued repose from you! She never will. Stand still when the battle is on the air, and the ground is sown with the blood of her brethren! She never--never will.

Sir, you cannot terrify the South. In vain will her people explore your own character, for evidences of the conqueror. You may be a sanguinary man. You exhibit no traits of being a warlike one. Guarded by prætorian bands in your capital; encompassed with ten armed attendants

Page 32

it is said, in your sleeping room; with liberty to practice still all the levities of your character, even in the darkest hours of your country's agony and suffering; not even intermitting your drawing-room entertainment on the evening of the day of the commencement of the civil war at Sumter, you do, indeed, resemble Nero, the blood-thirsty trifler, not Cæsar, the conqueror.

Sir, I am sorry to disappoint your vanity, or to abate your courage. But the truth, the fact-- the exclamation of pity for you, and the prophecy of victory in the war of liberty--is, that the South does not fear you!

I am, &c.,

THE SOUTHERN SPY.

Page 33

IV.

LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT.

NEAR THE GOVERNMENT, APRIL 27, 1861.

The President of the United States:

SIR: You are said to flatter yourself that you have now succeeded in expelling from Washington all who have dared to utter a word in opposition to your Administration. It is true that you have driven many of them out by armed mobs invested with the gilded livery of your service. Stationed on the highways and the by-ways, they have sought to kidnap men or to buy their souls for your service; divided into innumerable press-gangs they have daily explored the groggeries for victims; detailed as spies, they have constantly furnished to you, or your minions, lists for proscription; or straggling about the streets as liveried bullies, they have sought to entrap men into private quarrels, or to force them to self-defence, that the mob in waiting might overpower and murder them. Such, sir, is the condition

Page 34

of subjection to your imperial will to which you flatter yourself that you have reduced the city of Washington. The country will remember its history. It will remember that it has been accomplished while your partisans, including even the ruffian knight of Kansas, who guards with a hundred men your convivial night hours, have been holding meetings in the sacred precincts of the churches of Washington, to insist upon and to exclaim upon, with the old puritanical ribaldry of righteousness, free speech for "the Lord's people," but for none besides.

But, sir, you flatter yourself with one mistake. Many of the enemies whom you think to have expelled by your military mobs, have left Washington on other accounts. They hope to see you again. The mission of the National Volunteers was fulfilled in your capital before they left it, or before the minor organ of your Administration essayed to procure their arrest. Be careful, moreover, sir, how you give yourself up so entirely to the belief that all your enemies in Washington are expelled or subdued to fear--"Your lists are not yet full enough," cried the weary and trembling Robespierre to his secretaries, after months

Page 35

had been vainly spent in assuring, by the extent of his proscriptions, the Reign of Terror in the Capital of France. They were not full enough. A few days passed, and the gaunt and cowardly tyrant of Paris was in the hands of the avengers, and borne along the streets with the shout of the "guillotine" in his ears.

However entertaining it may be to some minds to observe the terrors of a tyrant, or to witness their realization, permit me, sir, to pass to notice some other lessons which you have given to the country in the condition of things you have maintained at your capital. In the small district where your authority is, for the moment, supreme, you have naturally given the truest examples of your theory and designs of government for the whole country. They are examples in which the wantonness of a Republican majority, the terrors of the cowardice of its leaders, exhibitions of military terrorism, oaths of feudal allegiance, and the subordinations of patriotism to the servile sentiments of vassalage contend for preëminence in the display. They are, in short, the most proper examples of the despotism which you desire

Page 36

to establish over the whole country, and in which you essay to maintain its union.

When will the country learn that your idea of maintaining the old Union of the States is simply despotic--conceived in no historical enthusiasm for restoring past glories--animated by no patriotic desires contemplating the good of the whole country--but coldly and sternly calculated in the narrow spirit of the despot. I do not accuse you, sir, without a record. Your own speeches-- and those speeches intended, too, as special explanations of your purposes--condemn you. When you were visited by a committee of the clergy of Baltimore, with messages and implorations for peace, you answered them in a style too vulgar and trifling to show the least real regard either for the Union or the peace of the country. In the accounts of such a conference, it was to be hoped that at least one historical sentiment might have dropped from your lips, or some words of grave, or, at least, decent concern for the destinies of the country. But the country was disappointed even in the small expectation of decency in your manners. You are said to have expressed

Page 37

no concern, but that for the safety of your person; to have given no other explanation of the war you were waging than a desire to secure the revenues of the South still to the coffers of your treasury; and to have had the effrontery, at last, to declare in the same breath in which you proclaimed your fears and cowardice, that you were determined to maintain your reputation for "spunk" in the prosecution of hostilities. Alas, sir, consider the spectacle: A committee before you, dignified by the holy offices of religion, and yet more dignified by their special mission of charity, entreating, in the last emergency, the restraint of the war you had declared, and you answering them with the explanations of that war in the needs of the treasury and your panic fears of being hanged, and with the wretched phrases and anecdotes of vulgar wit! I will not dwell on such a spectacle.

The accounts, sir, of your interview with the Baltimore committee are only paralleled, as they may be, in a measure, explained by the well known habits of your life in the retreats of the executive mansion. It is, indeed, a curious fact of history, that the worst tyrants have been

Page 38

remarkable for their levities of behavior, and have rather increased in the most terrible distresses of their country the frivolities and enjoyments of their palaces. You, sir, are said to illustrate this imperial peculiarity in the occupations of jest and conviviality in the White House, at the very time you are contemplating the proscriptions and massacres of your countrymen. You are no more willing to give up the trifles and privileged buffooneries of your position than to yield the substantial symbols of your power. You are not willing to return to your old resources in the taverns of Springfield. You wish to remain the trifler and tyrant of the White House; consoled by "experienced nurses" (whom Miss Dix has promised you); compelling "the old soldier," who protects you, to low familiarities with your person; and comforting yourself with the vulgar gloatings of the bully over the terrors of those who are afraid only because they are more cowardly than himself.

Indeed, such are the trivialities of your disposition, sir, that I can testify that you have not even yet restrained the pleasant liberty of the lady of the White House to prosecute her purchases

Page 39

in the "dollar stores" on the avenue. Twice this week I have had the pleasure of observing her there in the feminine elation of cheap "bargains."

But to return, sir, to a very brief analysis of your disclosures to your Baltimore visitors. We are left to understand by them that your motives for war are double: to save your revenue in the South, and to assure the protection of your person. If, in the compass of possibilities, you should attain the first--conquer the South to that point whereat you might be able to collect, by force, a revenue in her borders--consider that it could only be at the price of massacres which could never be repaid, and with the loss of all the great interests which may be enumerated in the peace and liberty of a country. If you should accomplish the second motive--the individual safety of Abraham Lincoln--it would be, sir, still more questionable in what respect your country would be a gainer.

If the regards fo your personal safety are really uppermost in your mind, why not, sir, effect them by the obvious means already at your command? Why not declare for peace? It

Page 40

might instantly restore the safety of your person. Why not resign, making your resignation on such conditions, or with such understandings with your constitutional successors as to call for a new election to the chief executive office? It, under present circumstances, would be the master-stroke of your life. It would be but giving to the people, impressively and directly, a question too grave for any one man to decide. It would leave you without the reproaches of weakness, and with the undying honors of having submitted a civil war to the last resort of arbitrament. It would imitate the conservative and virtuous feature of the British Government (which, in many respects, was the model for our own,) in the capacity it has, by a change of ministry, which is virtually the governing power, to adapt itself to changes of circumstances, and to conform itself, at all times, to public sentiment. It would--if this consideration can plead to you above all--save your person with decency and with certainty. But no, sir--you will not adopt these obvious and honorable modes of escape. The truth is, you are anxious to save your person, but you are anxious to save it as that of an enthroned despot.

Page 41

Do I not, sir, rightly interpret your feelings, or do I err in verbal accuracy in calling such a war of "safety" a war of despotism. Look back, sir, only to the date of your proclamation, and you will see that you have already fulfilled all the conditions of a war of bad faith and aggression, and already confirmed, beyond the possibility of a doubt, the character of your hostilities as those of a tyrant.

When you made your proclamation, you then indicated that the forces you summoned therein, were to be used to repossess the forts on the Southern coasts. You have already falsified this declaration of purpose. Under new pretences of protecting Washington, you have completely turned attention from the Southern forts, to invest Virginia and Maryland with your forces. Washington is but the strategical point of the campaign. It will enable you to seize Alexandria, to command the important heights of the Potomac, and to occupy the Northern portions of Virginia with subsidiary forces. On the other hand, the possession of the equally important point of Fortress Monroe is calculated to give you command of the low countries of Virginia.

Page 42

You are already in possession of the two important passages into Virginia. You have secured a safe and uninterrupted transit through Maryland, not willing, as yet, to risk the Thermopylæ of Baltimore. You have not only violated the sovereignty of Maryland in the usurpation of an absolute right of way, but that right, which you insisted upon for yourself, you have been prompt to deny to the people of the State itself! Your forces are to have free transit through the territories of Maryland, but the people of Maryland are not to enjoy the same right in their own territories. They are already cut off from Washington, and from Annapolis, while your own troops pass uninterruptedly between these points.

These movements, sir, betray the designs of an aggressive war waged by a desperate tyrant. You are said to boast already that, with the command of the Chesapeake, and of the larger portion of the Potomac boundary, to have effectually cut off the connection between Maryland and Virginia, and with Washington and Fortress Monroe in your possession, to "hold the wolf by the ears." We shall soon test the justice of your boast:

Page 43

we already know and appreciate the spirit of despotic subjugation in which it is uttered.

Virginia, sir, may have been betrayed into some degree of inertness by the false implications of your proclamation; and there may have been traitors in her own borders to help her to the false conclusion of maintaining what is called a "defensive" position. But the brave and enthusiastic spirit of her people will soon override the formularies of delay and of that caution in which treachery often finds at once its own concealment, and the means of seducing others. It will, it must soon confront you on the banks of the Potomac; it will, it must, at the last, brave you in your capital; it will, it must, as sure as the prophecies of necessity, lay your proud city in such ruins, as will leave nothing hereafter to be fought for. Carthago delenda est. Remember the end; it approaches; it involves your own destiny-- perhaps the life you have nursed with guards and bolts, and fattened with convivial joys, only for a sacrifice for the sword of the avenger.

I am, &c.,

THE SOUTHERN SPY.

Page 44

V.

LETTER TO THE EDITOR OF . . . . . .

MARYLAND, MAY 1, 1861.

To the Editor of . . . . . .

SIR: It is related of an ancient wagoner that having got his vehicle into a difficult pass, he implored Jupiter to extricate him. After long importunities in prayer to the god, to show him out of his difficulties, he, at last, received the simple answer, "put your shoulder to the wheel."

The bemired State of Maryland is imploring to be delivered from the difficulties, and terrors of her position. Let me say, the only way to do it, is to "put the shoulder to the wheel;" and while men delay to do this, it is plain she will only sink deeper in the mire and mold of her position.

It is strange indeed, that men of Maryland, who were going about a few days ago with the decantatum of "secession" on their lips, are now struck with a sudden stupor. They say that they can do nothing, that they are powerless, that the

Page 45

reversion of public sentiment, under the influence of the fears of the people, is now irresistible.

The fact is, sir, that there is a reversion, and a reversion which is one of the most naked and shameless tergiversations of the times. While too many are satisfied to rest the cause of liberty on mere protestations of feeling, or on idle invocations for help, a constant appeal is being made by others to the fears of the State, to drive her back into, the refuges of the Union: all manly sentiment, all generous sympathies, and that spirit of devotion which is the spirit of independence, are choked by spectral fears, or crushed in the selfish and narrow considerations of the present.

Maryland is advised to try no "crucial experiments," but to betake herself to the safe position of a temporising policy, in which she may give the advantages of her neutral position to the Lincoln Government, and yield the privileges of her soil for the present, to its troops, and, possibly, hereafter join the Southern Confederacy, but only in the event of the successful establishment, or the acknowledgment of its independence. This dishonorable, cheating, double position--this precious, safe game of ambidextrous neutrality--is

Page 46

now the constant theme of recommendation that assails the ear. Even one of the hitherto most excellent and patriotic journals of Baltimore is now prompt to recommend the duplicity and advantages of such a position. The copy of this journal which lies before me at the date of this writing, advises a pledge of good faith, made on the honor of the State and without reservation, not to take up arms against the Federal Administration, so long as the city of Washington is held and occupied by them; nor to offer any hostility or opposition to the Administration, or the army assembled for its support upon the soil of Maryland. It adds in cold, confident, shameless terms the following explanation of its choice:

"The result of this position would secure to "the Administration the enjoyment of all the advantages "to be derived from the territory of a "neutral, with the assurance of absolute safety "within that territory; and with the possible "maintenance of peaceful relations until the "Union was restored, if that be practicable, or "until the independence of the Southern Confederacy "is recognized."

Such wretched ambiloquy as this--such a miserable

Page 47

cheat as this is sought to be imposed upon the honor of Maryland, and the honor of that cause, which she proposes to pollute by mercenary and chaffering embraces. God forbid that this should be the choice of Maryland! God forbid that she should sell her destinies and honor to any of the infamous bids to pollute her--to the cheats of the press; or to the suggestions of terrorism; or to Gov. Hicks' plain-spoken proposition to debauch her; or to the gold of "the commercial centres" of the North, already busy in corrupting her honest choice; or to the cunning toils of the wizen-faced King of Plug-Uglyism, who seeks to purchase by Maryland's infamy the seat in Congress that he has already assoiled by his own treachery!

Sir, I cannot write with patience of these attempts to betray a State, whose heart and honor are alike noble. Excuse me for my warmth. And pray understand, also, my own position on this question, not as that of recommending instant and reckless secession to Maryland, but of advising only active, willing, laborious, thorough, and spirited preparations for what in the end must be, and should be her position. Her sister

Page 48

States of the South appreciate the present, helpless situation of Maryland, and do not ask, as they cannot expect, her immediate separation from the Union; but they do expect that she will not be idle or submissive, or indifferent, but that she will prepare herself; that she will arm herself; and that in undiminished spirit she will await the time, when she may declare herself, purely and bravely, and, above all, without mean reference to what side victory inclines to, a member of the Southern Confederacy of States.

God forbid that any should be so unjust, or so athirst of blood as to condemn the present enforced suspension of her action. But I condemn, sir, the designs of her enemies to take advantage of the present necessary spell to place her in a position of irretrievable and certain submission to the misgovernment of the North. I condemn the cheat of imposing upon her the farce of a one-sided neutrality, unable to protect itself, and the next necessary step of which will be union with the North. And I alike condemn that pretence of neutrality, which is to enable her to adopt, in the course of events, whichever side is proved to be the stronger, and which, while professing desire

Page 49

for the connection of Maryland with the Southern States, makes itself safe by reserving the alternative of siding with the Lincoln Government, in the event of their discouragement.

It is unnecessary to expose here the positions of Gov. Hicks' message. Sir, it is not worth the prick of a pen to disturb it. Whatever the Legislature of Maryland may do, it is some satisfaction to know that it will be entirely without reference to his recommendations; and whatever scheme may be determined by it to advise or provide for the suspension of the State's action, it will, at least, be unlike the clotted lump of nonsense, which he has recommended as "neutrality."

Very truly, yours,

THE SOUTHERN SPY.

Maryland, May 16, 1861. * * * * * * * * * Since the above letter was written, Maryland has fallen further within the grasp of the despot. About thirty thousand foreign troops are on her soil to-day; the Legislature has been wholly inane, and has assented to the attitude of submission indefinitely; the city of Baltimore has been subjected to military occupation and to the insults,

Page 50

for a time at least, of the dawdling and inebriate proclamations of an obese, epauletted Yankee; and while efforts have been plainly in progress to disarm the State, and to violate her military organization, her shuffling Governor has sought safe occasion to ape the tyranny he obeys, and to make a call for four regiments of volunteers to answer the requisition of the now old and spent war proclamation, made a month ago by the cousin of humanity perched in the Executive Chair at Washington. The soldiers, the apes, the time-servers, and the mummies, are the curse of Maryland. And what of the patriotic, liberty-loving men of the unhappy State!--Said a hero in the trials of the Revolution of 76: "too many flatter themselves that their pusillanimity is true prudence; but in perilous times like these, I cannot conceive of prudence without fortitude!"--that is not active bravery and prowess, which are sometimes untimely, but "fortitude:" the patient, confident, heroic spirit, which, while it waits for opportunity, makes both it and the preparations to use it. Let Maryland act on this hint--let her make, as best she can, both the opportunity and the preparation to strike home with the avenging

Page 51

arm--let her preserve and exercise her fortitude-- let her do this; or let her assume at once a repose of irretrievable infamy! Nullum est tertium.

S. S.

Page 52

VI.

LETTER TO SECRETARY SEWARD.

MARYLAND, MAY 10, 1861.

To Mr. Secretary Seward:

SIR: You have been for many years an object of public curiosity. Excelling in the concealments and disguises of empty declamation, remarkable for the glosses of your style of expression, and exhibiting that command of language which makes it perform the office of concealing rather than expressing thoughts, and which was so happily illustrated in your well-known composition of the Inaugural of the Illinois President, your sentiments and your character have been very differently estimated in the opinion of the public. You have been regarded as a statesman it the parts of the North, where people, judging from their own stand-points of character, have esteemed statesmanship to consist in low cunning and artful non-committals of evil designs; and to them your very New England visage of narrow

Page 53

and skulking selfishness has been taken as an index of Yankee wisdom and ability. By others, sir, who profess to have pierced the disguises of your character, you are condemned as a demagogue, a character baneful in the days of peace, but in the great peril of a country, then the most heartless mercenary and dangerous of wretches.

I am truly sorry, sir, to see this latter estimation of your character confirmed by your recent exhibitions of the narrow and demagogical statesmanship that you have so long sought to conceal. An acute man may long find resources of concealment in ambiguous and artful words; but the word and spirit of his expressions, especially should he be over-fond of talking and writing, will eventually betray his sentiments and designs to the mind of the people.

In the last Senate, you made a glowing appeal for the Union; you confessed it to be in danger; you besought sacrifices, even of party, to sustain it. You must have been only amusing the people with these declarations; for in your late official letter of instructions to the recently appointed minister to France, you urge him to assure that government of the fact that the idea of a permanent

Page 54

disruption has never entered into the mind of "any candid statesman in this country," and of the certainty, too, of the continuance of "the constitutional Union," and that, too, as an object of "affection!"

How, sir, do you explain this inconsistency? Is the Union in less danger now, when war is proclaimed, than when, in the season of conventions, you delivered your glossed and jesuitical speech in the Senate for its preservation? Is it the fact that no statesman in this country conceives the possibility of its rupture? Pardon me, sir, are you truthful in this? I acknowledge, sir, that there is a magnanimous part in these declations, and I congratulate you for it. You are willing to confess that you were no statesman in once contemplating the danger of the Union. You are willing to make yourself out as formerly, a fool. But, sir, will the country be satisfied to take even this magnanimous confession: for, remember, sir, there is yet a more scornful name than that of fool, and for calling which, inconsistency sometimes affords equal grounds.

You have abandoned your exclamatory statesmanship for the Union to adopt in its stead the

Page 55

wisdom of your master, and to substitute for your former anxieties his vulgar apothegms of "all right," "nobody hurt," and "nothing going wrong." You are, indeed, a supple tool. Now when the Union is imminently threatened, you exchange the fears you had for it, when it was only moderately threatened, for Abraham Lincoln's vulgar and insolent confidence, on which you improve by the art which is peculiarly your own. You misrepresent. You misrepresent a great government, inaugurated under the solemn and imposing forms of State authority; already sustained by nearly eight millions of people; exercising among them all the ordinary functions of government, and receiving their willing obedience, and standing before the world for rightful recognition--you misrepresent it as a disorganized insurrection, from which nothing is to be feared, and you rank it with the passing and incidental "changes" in the history of the Union.

This, sir, is in consistency, at least, with the war proclamation of Abraham Lincoln, of which I can now well believe the report that you were the scrivener. In that proclamation, which had to be bungled into conformity to a tortured law

Page 56

and to a perverse misrepresentation of facts, it was necessary to style States acting under the solemnities of organic bodies, as "unlawful combinations;" and to support, still further, the affectation of a mere raid, we had to be refreshed with another Lincolniana, in warning four or five millions of people, standing on their own soil, to return within twenty days to their homes! What an example of seriousness, of truthfulness, of justice, of patriotic courage and patriotic rhetoric, I leave the world to admire.

I am willing to admit, sir, that the misrepresentations you couched in this famous proclamation, and that you have attempted now to renew to the Governments of Europe, would be most richly, as they are most impotently, ridiculous, if they were not so foul with falsehood, as to excite disgust as well as derision. Why conceal the fact of the existence of a Government in the South, recognised within its own jurisdiction, and exercising all the powers for revenue, civil order, legislation, the administration of justice, peace and war? Why atttempt to degrade a great revolutionary fact by misrepresenting it as an insurrection or raid? You, sir, are best able to answer

Page 57

these questions. You know best your own purposes

for degrading the Southern movement to

the proportions of an incidental insurrection.

You know best the extreme necessity for balking

the European recognition of the Southern Confederacy.

But, sir, you attempt a vain and

shameless task, when you seek to encounter a

question so serious and critical by attempted concealments

and falsifications of facts op

The Governments of Europe, you may rest assured, will not take the facts regarding the condition of affairs in the South on the representations of inimical statements at Washington. They will ascertain and estimate them for themselves. Indeed, the very expedients employed in the conduct of hostilities on the part of your Government, as well at on the side of the South--blockades, letters of marque, &c.,-- will constrain the European powers, so far from recognising your dwarfed representations of insurrection, sedition, &c., to govern their action on the basis of the actual existence of war, and to recognise the South as a belligerent. This, sir, you may see, opens the

Page 58

door at once to the recognition of a de facto Government.

You, sir, not only have committed yourself to a bad and superrogatory task in seeking to impose upon foreign governments your misstatements of facts in the South, but you have also traveled out of the way to communicate through the letter to Mr. Dayton, the mere opinions and sentiments of the Government at Washington to oppose the recognition of the Southern Confederacy. Such blunders and ignorance in diplomacy were scarcely to be expected from you. It was to be supposed that you were at least acquainted with the simple rules, to govern a matter of ordinary diplomatic routine. You have proved yourself another example that the greatly learned are sometimes not above the blunders and ignorances of common men. You are another Gundling--another great light in "the Tobacco Parliament," to settle public affairs. But it was to be supposed that you were, at least, not more ignorant and thrasonical than Gundlings generally are. It was to be supposed that you were, at least, aware that the question of the recognition of a de facto Government was to be determined by facts, and not by

Page 59

the opinions and views of that Government which it had succeeded. It was to be supposed that you had the small amount of knowledge to apprehend that the question of the recognition of the Southern Confederacy by Foreign Powers, was, for them, a question lying with the Southern people, and having nothing to do with the Federal Government, that is ipso facto foreign to those people.

The doctrine that must determine the recognition abroad of the Southern Confederacy, is so simple and severe, that it is, indeed, astonishing, sir, how you could have so mistaken it as to interpose the question with the views and, opinions of the Lincoln Government, as to the reality of the Southern Confederacy. The question has nothing to do with these. It is one of fact, and that fact simply the determination whether the new Government sustains itself, and is recognized and obeyed within the limits of the jurisdiction it claims. It matters not whether it is a revolutionary Government; it matters not whether it is contested by a former regime; it is sufficient that it is recognized and obeyed by its own people, and performs steadily among them the regular functions of a Government.

Page 60

To recommend a new Government for recognition abroad, it should assuredly fulfil these conditions-- that is, be found in steady exercise of governmental functions, and be acknowledged and obeyed within the limits of its local jurisdiction. Beyond those limits the inquiry ceases. It is the obedience of its own people that essentially makes the Government. It is not necessary, sir, to refer for these plain doctrines of recognition to the precedents of general history, or to the recent illumination of the whole subject in Europe by the Italian question. Our Declaration of Independence finds for us the just powers of Government in "the consent of the governed."

But without looking back now to the distinguished examples of history as to the recognition of de facto Governments, you might at least, sir, refresh your mind by teachings so recent as those of the real statesman who was but one remove your predecessor in the high office which you now encumber with your pompous ignorance. I refer to the doctrines declared by Mr. Marcy on the Nicaraguan question, as establishing for our own Government the most recent and strictly defined precedent for the recognition of powers de facto,

Page 61

and doing so by putting the whole question on the simple doctrine of the reality and of the acknowledgment of the new Government by the consent of the people composing it.

Such, sir, are at once the guides and the assurances for the recognition of the Southern republic I will not be led now into the discussion of their truth or probability. I have not written for the purpose of a general discussion of the doctrine of recognition, but only to show you, sir, how the plainest outlines of that doctrine have been violated by your false, intermeddling advices to the Governments of Europe. Be, at least, sir, truthful and decent in your zeal for Mr. Lincoln's Government. Be serious, sir: restore yourself to the society of third-rate politicians: do not disgrace them by having your falsehoods and cheats too plainly detected! Cease your busy misrepresentations to Foreign Governments--cease your boastful assurances of Abraham Lincoln's "one Government and one Nation"--cease your dissemination of the views of a Government, which no longer has any jurisdiction of a case that is given to the judgment of the world: and be satisfied for justice and decency alike to leave the

Page 62

question of the recognition of the new Government in the South, where it belongs by history, by precedent, and by right--to the impartial ascertainment of the state of facts existing within the limits it has appointed for its own jurisdiction.

I am, sir, &c.,

THE SOUTHERN SPY.

Page 63

VII.

LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT.

MARYLAND, MAY 30, 1861.

To the President of the United States:

SIR: The course of despotism is that of rapid and aggravated progression. Commencing with doubtful claims of power, it hurries to plain usurpations of it, and, at last, seizes the sceptre of absolute authority. In little more than a month, your course, sir, has illustrated the rapid steps of despotism from its first unlawful act to the last extremity of the usurpation of power. The catena is complete. You commenced with a proclamation of war against the South. What have you done since? You have more than quintupled the army in disregard of the provinces of Congress. You have strangled the liberties of the people. You have caused the military arrest of citizens in jurisdictions where the Federal Courts have been in uninterrupted operation.

Page 64

You have caused their house to be searched, and blank warrants to be distributed for inquisitions. You have suspended the writ of habeas corpus. You have administered to the army and civil officers of the Government a new and altered oath of allegiance. You have broken the sanctity of private correspondence, seizing the despatches preserved for years in the telegraph offices. You have violated the right of the people to keep and bear arms, robbed even the public authorities of arms in their possession, and of their purchase, and denied the right of a State, still remaining in the Union, to continue the privileges, which the Constitution has named and provided as "necessary to a free State." A State remaining in the Union is no longer free. A citizen remaining in the Union is no longer free: he is subject to arrest, by military process; to search, at pleasure; to espoinage, even in his private correspondence; to imprisonment, without recourse to the courts; to tests, whenever you choose to exact them ; and to deprivation of arms, whenever your power may be thought to slacken, or your cowardice may happen to be shaken by alarms.

Such, sir, is but a hasty grouping of the acts

Page 65

by which you have violated both the wisdom and the law of the Constitution, and erected a throne of despotism in your frightened capital. But the character of a despot is not completed by mere violations of law. There are violations of honor, morality and truth, more infamous than excesses of authority. It is of these, sir, that I would tell you as gloriously crowning you with a complete despotism--of these that I would remind the country, as staining you, beneath the gauds of the robe, with the very dregs of infamy.

The present stage of the war developes two facts which happening close together, at once expose and complete its policy. We see, first, the false tokens of your Government to the world: next, its betrayed pretences to its own citizens.

While, sir, your Government was attempting to amuse Europe with misrepresentations of the present war as a local mutiny, it was giving the lie to itself, and repeating it at every step in its own line of policy at home. You had assumed to establish, as against the South, a blockade, a severely belligerent and punitive right, at the same time that you protested against the recognition of the South as a belligerent. You insisted

Page 66

upon the denial to the South of a right that your own belligerent position towards her had called out. Not only this, you insisted upon the excision of the right of privateering from the South that your own Government had, in 1856, expressly reserved for the very occasion in which the South assumed to exercise it, namely, to supply the deficiency of a naval power.

You were caught, sir, in your own inconsistencies. It was not to be supposed that the very right your Government had laid the foundation for in its own position of belligerent, and that it had preserved, as a careful tradition of its own policy, was to be denied to the South by the world, only for the interest and benefit of your own Government. That, sir, would have been a degree of stultification and of subservience to your purposes, that you had no right to expect from the world. Your supreme commands at home, and the absolute fawning obedience of a lickspittle and hungry constituency have encouraged you to rather too high a dictation. Do not fret yourself, sir, with false expectations. Do not imagine that the world will surrender its conscience to you because Yankeedom has done it; that

Page 67

it will accept your falsehood and despotism, because "the Northern unit" thinks it truth and valor and honesty; and that it will listen unquestioningly to your maxims of public law, because "the great North" thinks and licks them over as sweet morsels of wisdom, and anoints them with the slime of its own grovelling passions.

Do not be illogical, sir. Do not mistake the sentiments of Illinois for the opinion of Europe. You have disgraced yourself and the great North enough already by the dancing and shuffling policy of your Premier towards the Governments of Europe.

Your blockade of the Southern coasts is already despised; it cannot be maintained. England and France are determined to have their cotton, tobacco and naval supplies from the seaports of the South. A line of such extent, with the numerous inlets on the coast from the James River to the Savannah, could, in the nature of things, by no application of the naval force at your command, be blockaded. Equally vain with the attempt to maintain a blockade, on such a line, constantly and vigilantly assailed by the whole commerce of Europe, will be your attempt, sir, to

Page 68

resist the public acknowledgment and exercise of the right of privateering on the part of the South-- a right which was conceded to Greece in her revolt, and to the South American republics in their struggle for independence, and which, I repeat, was retained by your Government in express and permanent terms. The precedents of the Government at Washington will be turned against itself. "The militia of the seas" will destroy the commercial and navigating interests of the North; they will scour the South Pacific as well as other oceans of the world; they will penetrate into every sea, and will find as tempting prizes in the silk ships of China as in the gold-freighted steamers of California. The reversion upon your Government, sir, of its own maxims of public law is only needed to complete the ruin of the North, not only in her commercial interests, but in the immediate issues of the present war. The negation of the right of search will estop you from discovering contraband goods under the neutral flag of England or of France. It will leave the trade in contraband as free as any other. A moment's reflection will show you, sir, that the fixed precedents and cherished traditions of your

Page 69

own Government have only to be completely turned against itself by the world, to reduce it to the most miserable imbecibility, and its people to their knees, and the deploring there of their own self-purchased destruction. The question alone remains, whether this complete reversion will be made;--and this question I am satisfied to leave to the justice and to the interest of the European Powers, when both these motives are conjoined and harmonized, to determine their action.

Heartily, sir, do I give thanks that the ambitious falsehood you sought to introduce into your foreign policy, on the subject of the present war, has not only been disappointed of its end, but has introduced a new element of controlling importance into this war. This element, which you have, unluckily for yourself, introduced, I believe to be almost vital and decisive. It will subordinate a controversy, which you hoped to keep in your own hands, and within the narrow restrictions of Mr. Seward's Yankee statesmanship, to the public law and the public opinion of the world. These are enduring, far-reaching, and ultimately decisive powers. Falseness and aggression,

Page 70

sir, in the war you are waging, can only be fatal to yourself. As abroad, the same policy has brought you into difficulties, so, at home, it will surround and destroy you. As the falsehood by which you sought to entrap the conscience and judgment of Europe has come back with retributive justice, so the falsehood of your policy at home will recoil and strike back upon yourself. The exposure of your policy to the world is sufficiently found in your intermeddling in Europe: it is seen at home, now, and in the light of day, in your invasion of Virginia.

This act, sir, has completed the infamy of your character. You have perpetrated it against all promises and pledges; you have multiplied by it falsehood on falsehood; you have put imagination on the rack to perceive what limit there can be fixed to your unscrupulousness, or what bounds set to a mendacious Government. Pretext has been exchanged for pretext, until the country, sir, has actually been bewildered at your enormous resources of falsehood. If, from all the slough of your proclamations, the mess of words you called an Inaugural, and the confused nonsense of your speeches, official and unofficial, one distinct

Page 71

proposition was drawn by the country, it was that you would not make an aggressive war upon the South. You defined for yourself the meaning of such a war, when, in your wayside speech at Indianapolis, you essayed a distinction between repossessing the forts, &c., in the South, and invading its territory, the latter of which only you esteemed to be war in its aggressive sense. Have you forgotten that distinction, sir? The country has only to look back upon it to discover your flagrant falsehood. Can you not cure it, sir, by some new distinction--some new pretext, so as to bring this invasion of Virginia under the terms of the Indianapolis speech, and the proclamations and manifestoes of a later date? Can't the adept Premier help you to a new logic, or a new falsehood?--or was he too plainly discovered in his ingenious ways by Judge Campbell, when the Judge, the equal of Mr. Seward in political position, twice charged him with "overreaching and equivocation," and he, the great representative man of the great North, twice slunk into silence under the charge?

Those, sir, who are committed to support you in all things, and to all extremities, are easily

Page 72

satisfied with explanations for every inconsistency or outrage you may choose to enact. Address yourself to these creatures, sir. You can, perhaps, explain to them that you have seized Alexandria to reclaim her as part of the District of Columbia; you can, perhaps, parade to them a pretext that you have been called into Virginia, "to protect Union men;" you may, perhaps, convince them that Alexandria is one of "the places" of the Government within the purview of the war proclamation; you may possibly even persuade the hang-mouthed listeners on your wisdom and bravery, that there is some old, strange claim of the Government to be revived to the odd-named Newsport-Newspoint at the mouth of the James River. As there are sometimes no limits to the mendacious utterances of a man, so, sometimes, there appear to be none to the servile acquiescence of fanatics and flatterers.

Virginia, and the honest world that regard her, sir, need not another word from you. Both understand you. You would repeat upon her your easy conquest of Maryland, seize her railroads, step by step, plant her with your troops, and then lay your strangling grasp upon her

Page 73

liberties. The falseness of policy, sir, superanimates the energy to oppose it. Your treachery has inspired all the vital forces of Virginia to compass your ruin, and directed all the scorn of the world to accomplish your infamy.

Filthy with falsehood, covered with treachery as with a garment, you will be, at once, expelled from Virginia, as by a sword of fire, and be driven from the honest conversations of the world, as a leprous despot, shunned and yet marked, hated and yet despised. The world, sir, has not yet outgrown the feelings which the inspired accounts of the first invader of man's kingdom of peace were intended to inspire. It is not likely to forget them--not likely to be unreminded of the old story of the Serpent, in the false words, subtle, gliding invasions, and anfractuous policy of Abraham Lincoln.

Without a word of premonition, against all promises and all expectations, in the night time, while the stars of the approaching morning alone watched in the sky, you glided into Virginia, silently and beautifully as a serpent in his slime and glittering scales. Let it be so! Let the serpent coil himself strongly! "The wisest of

Page 74

beasts," he is yet not the strongest. There are talons to fight him, to strip him, and to tear his writhing folds between heaven and earth, as his golden scales fall one by one in the sunshine, up which the eagle flies with his prey.

I am, &c.,

THE SOUTHERN SPY.

Page 75

VIII.

LETTER TO THE REV. DR. TYNG OF NEW YORK.

BALTIMORE, 1861.

Dr. S. A. Tyng:

SIR: Your office admonishes me to address you respectfully. Be pleased, sir, however, to distinguish between the respect which I readily give to your office, and that which I must be studious to withhold from your person.

Sir, you are a minister of the gospel. May our Almighty Father in Heaven pardon me, if I say, in any other than the deepest humility and distrust, that I, too, am a member of His Church on earth, and a suppliant at the throne of His mercy.

Religion may have its military ideas, sir; they are ideas of necessity, not of wrath. It may be proper, it may be dutiful, though unwelcome, in a Christian man, sometimes to speak harshly, to chastise falsehood, and to let loose his wrath upon evil men. In connections with the secular press,

Page 76

I may have spoken with severity. I claim the right to use it against bad men in high places, murdering my country or betraying it. But, sir, even the language of just denunciation, I would restrain against you, a priest of the church;-- but, understand, sir, not that I esteem you less false or murderous than the politicians whom you serve, but because you are clothed in an office, holy and venerable in itself, however wretched and abandoned the man it may cover. The apostle was sorry to have denounced the whited Pharisee, who would have stopped his words with blows, because he "wot not that he was the high priest."