The Rivals:

A Chickahominy Story:

Electronic Edition.

Haw, M. J. (Mary Jane)

Funding from the Institute of Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Melissa Graham

Text encoded by

Lee Ann Morawski and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2001

ca. 226K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) The Rivals: A Chickahominy Story

Miss M. J. H.

61 p., ill.

Richmond

Ayres & Wade

1864

Call number Conf #236 (Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library, Duke University Libraries)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

This electronic edition has been created by Optical

Character Recognition (OCR). OCR-ed text has been compared against the

original document and corrected. The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Chickahominy River (Va.) -- Fiction.

- Confederate States of America -- Fiction.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Campaigns -- Fiction.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Fiction.

- Virginia -- Social life and customs -- Fiction.

Revision History:

- 2001-04-11,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-01-17,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-12-07,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-11-27,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

THE RIVALS:

A CHICKAHOMINY STORY.

BY

MISS M. J. H.,

OF VIRGINIA.

ILLUSTRATED.

RICHMOND:

AYRES & WADE.

1864.

Page 3

THE RIVALS.

CHAPTER I.

Near the close of a bright June afternoon, two boys were slowly sauntering along a narrow, grass-grown road conducting through a dense oak wood to and from the old Washington Henry Academy, a very venerable, if not a very renowned seat of learning, in the county of Hanover, Virginia. The arm of each was thrown over the neck of the other in the familiar and affectionate manner so common to boys who are very particular friends; and between them they held an open letter, a passage in which one was pointing out to the other. The one to whom the letter evidently belonged was a remarkably handsome youth, with a delicate, graceful figure, regular and aristocratic features, a pale olive complexion, and jetty hair and eyes. But although in the formation of his face nature had strictly adhered to the laws of beauty, yet from within, the soul, in its outbeaming, had imprinted upon this otherwise fair index, some things less agreeable than the perfect lines and curves of the beautifully chiseled features. There was about the large, dark eye and the high, pale brow, an expression of reserve and caution almost sinister; the poise of the small classic head, and the curve of the thin, pale nostril, betokened a hauteur almost offensive in its excess, and the line of the thin, red lips, though graceful and artistic, bespoke a mingled cynicism and egotism rather unpleasant than otherwise to contemplate, Still, the shadowy, mystical pencilings of the soul upon the countenance were as yet but faint--the youth was but seventeen--not strong enough to mar greatly the general harmony of color and proportion indelibly stamped there; and the general, yea, the universal verdict was that Walter Maynard was a very handsome youth.

The artist, upon coolly inspecting the more athletic, but less perfectly symmetrical figure, and the less regular, though more manly features of his friend and companion, Charley Foster, would have pronounced them less beautiful than those we have described; this would, perhaps, also be the verdict of the superficial observer who might not be an artist; but the physiognomist, who looked beyond the inferior material, qualities of form and color, to the mental graces, or deformities which are capable of shedding such a magically beautiful light, or such a repulsive cloud over the 'human face divine,' would have pronounced differently. The pure light of intellect which illuminated the faces of both was about equal in degree, and nearly so in kind but those mental qualities which go to form the moral nature of man, had been distributed between them by Providence with a view to producing variety rather than unity. The broad brow, and clear, dark gray eye of Charley Foster shone and beamed with candor and sincerity; about his rather large, though well-shapen mouth there was an expression of mingled firmness and tenderness quite captivating to behold; in his free, easy carriage there was just enough of dignified self-respect to inspire respect in others; and his frank, cordial manners courted the friendship and confidence which the gravity and reticence of Walter seemed to repel. By their school mates, the one was admired; the other, both admired and beloved.

Page 4

When they had proceeded a short distance, they paused under a huge oak tree, which stood immediately on the roadside, and Charley threw himself on the grass at its foot, and resting the elbow which supported his head on its mossy root, exclaimed--

'And so, Walter, you are going to be a soldier?'

'Yes,' replied Walter, seating himself beside him, 'so it seems; my aunt Emeline writes, you see, that my great uncle, Horace Maynard, who has charitably undertaken my education, that I might not disgrace the family by my ignorance, has procured me an appointment to the West Point Military Academy.'

'Well,' pursued Charley, without noticing the slightly ironical tone in which a part of his friend's reply was delivered, 'I should not have thought of your being a soldier. You are brave and ambitious enough, to be sure, but I do not think you have the reckless daring and love of adventure one naturally associates with the members of the military profession. In my mind, I had decided upon the law for both of us, and I think, Walter, that you have some qualities which peculiarly fit you for the legal calling; I though, too, that the law was your choice.'

'Beggars should not and certainly cannot be choosers,' replied Walter, bitterly. 'You forget, Charley, that I am an orphan, and poor; that my father and grandfather spent their lives in squandering the princely estate their ancestors had accumulated, leaving me an old name and an empty purse; that I am dependent upon my aunts, who have reared me, and upon my great-uncle, who, purely from family pride, has charged himself with my education, and am compelled to submit to their direction. This military scheme has enabled uncle Horace, with his usual address, "to kill two birds with one stone." I will go to the academy as a kind of pensioner, to be snubbed and jeered at by the wealthy cadets, and therefore my expenses will be to him inconsiderable, while I will be obtaining a good education and an honorable profession; and if I contrive to get through with credit, I will doubtless get a lieutenantcy in the army, which will pay about as well as a third-rate clerkship in some mercantile establishment and keep me cooped up in a marine fortress, or banished to the wild frontier during the whole of my natural life, like some unfortunate state prisoner or political exile.'

'You paint a gloomy picture of it,' said Charley. 'If you object to the scheme, Walter, oppose it at once. If you are young, you have a right to be heard in a matter of such importance to yourself. If you prefer some other calling, my father will, I know, lend you any amount of money necessary to pursue it for my sake.'

'Oh, no,' replied Walter, quickly; 'I could not think of such a thing. It is too humiliating to be in debt. I find it bitter enough to be under obligations to those from whom I have a right to expect favors, ever to consent to accept them from those upon whom I have no claim. Besides, the plan you propose is rather too uncertain. It would take a large sum to enable me to graduate in law or medicine, and then I might not succeed. Or if I should ultimately succeed, either profession would not be immediately self-supporting, while that which uncle Horace has chosen for me will be. And if the military profession is not lucrative, it is certainly very honorable, and in my case very sure. You know the army is almost universally chosen for the younger son of the British nobility, and is patronized by the first families in Virginia.'

'Very true,' was the response, 'I dare say that with your pride, the glory will quite outweigh the hardships of a soldier's life. You know that all the big men of history were soldiers. Who knows, Walter, but that you may be another Cæsar, or Napoleon, leading powerful armies, and dazzling the world with your skillfully planned campaigns and brilliant victories.'

'Nonsense!' said Walter, laughing. 'Promotion is rather slow in our army; and even if I possessed the talents of a Cæsar, or a Napoleon, I would scarcely have an opportunity to display them. Don't you know that Mr. Reed told us, only this afternoon in our history class, that so far as human foresight could penetrate, America seemed doomed to years, perhaps centuries, of unbroken peace; that the Monroe doctrine, which had become the established policy of our government, would secure us forever against entanglements

Page 5

with foreign nations, while the extent, the wealth and power of our country would enable us to control our feebler neighbors on this continent.'

'Yes,' observed Charley; 'but have you forgotten what we were pleased to term the idiosyncracy of Mr. Reed's French friend, Monsieur Bossieux who visited him last year? He declared, you know, that the American people were treading on a volcano; that the vast extent of our territory, and the wide diversity of opinion and interest between the people of its different sections, would inevitably lead to disruption and revolution; and he boldly predicted that the sectional animosities, so apparent to a foreigner, would show their bitter fruits in intestine war before the present generation should be gathered to their fathers.'

'Pshaw!' exclaimed young Maynard contemptuously, 'what does a Frenchman know about American politics? However, we can pardon his error if his opinion of government is founded on French history, and his views of human nature are derived from the contemplation of the French character. But we Americans are made of firmer material, It would be ridiculous to compare the glorious republic established by our worthy revolutionary forefathers to the monstrous abortion brought forth amid the fearful throes of the horrible and fruitless revolution of France, and it is no less ridiculous to compare their sons, who are charged with the maintenance and honor of our government, to the ignorant and frenzied rabble who attempted the same experiment in M. Bossieux's country, and failed. He saw with a Frenchman's eye, and judged with a Frenchman's judgment--superficially. The Presidential election was going on and he was misled by the violence of party excitement; the election is now over, and see how profoundly quiet the country is.'

'Yes,' said Charley, 'and very probably if he is in America now he has already changed his mind. What is that beautiful figure, Walter, of the famous Druid's stone which is so perfectly poised that it may be rocked to its very centre by the touch of an infant's finger, yet the combined strength of an army of strong men cannot overthrow its equilibrium--how appropriate it is to our government!'

Thus discoursed these sage philosophers and profound politicians of seventeen and when they had done discussing the affairs of the nation, they returned again to their own, and took up the subject of Walter's future prospects in his newly chosen profession. Naturally enough, their favorite heroes among the military characters of history were brought up, their campaigns and battles gone over, and their relative merits diicussed until the two youths grew quite enthusiastic in praise of a military career. Charley declared that the martial spirit was fully aroused in him, and that he felt quite as belligerent as old Dick Jones, who said that after going to Pole Green to muster and drinking a quart or so of mean whiskey, he was fighting the battle of Yorktown over for four days. In the ardor of the moment he determined to accompany his friend to West Point, if his father would give his consent to it, and be a soldier too.

Just at this juncture, their attention was attracted by the tramping of hoofs behind them, and looking in that direction they saw a beautiful apparition emerging from the deep shade of the dark green foliage. It was that of a dainty, fairy-like, girlish figure sitting gracefully upon a small white pony. By her side, on a larger horse of dark color, rode a large, homely and awkward boy, to whose linen roundabout, a pretty timid-looking little fellow, who was riding behind him, clung nervously as he urged the horse to a brisk gallop to keep up with the rapid pace of the little lady's white palfrey. A negro groom, much encumbered with satchels and carpet-bags, brought up the rear of the cavalcade.

'It is Nellie and Bernard Gardiner going home, and Bob Harrison is going with them,' said Charley.

The two boys had arisen on the approach of the party, but absorbed in watching Nellie's splendid horsemanship, and looking at her pretty face and figure they had forgotten to move aside, and stood in a position to slightly obstruct the road.

'Get out of the way, fellows,' cried Robert Harrison rudely and imperiously, bearing down upon them.

Page 6

They stepped aside instantly, and politely touched their hats to the young lady, while an angry flush mantled Walter's dark cheek, and a smile, half amused and half contemptuously, parted Charley's flexile lips.

Nellie gracefully returned their salutation, and said reproachfully as they swept by, 'O, Cousin Robert, what makes you so rude?'

When they had passed, Charley, who stood looking after the girl with his whole heart in his eyes, observed to his friend, 'Nellie is a pretty little thing.'

'Yes,' replied Walter, regarding her retreating figure with a look half admiring, half speculative, 'very pretty. But she will be still prettier when she gets older; and she will be quite a belle, I expect; for they say she is worth fifty thousand dollars independently of her mother, who is wealthy.'

'How unlike she and Bob Harrison are for cousins,' remarked Charley.

'Very unlike,' was the response. 'Bob Harrison is, undoubtedly, the most conceited, pompous and purse-proud fool that ever lived. I intend to let him see that I am not to be treated with contempt by him, if he does happen to be rich while I am poor. When next he finds occasion to accost me it must be in terms more respectful than those he used just now.'

'Fiddlesticks!' said Charley, 'who cares for what Bob Harrison does? He is beneath the contempt of a sensible body. His airs of superiority, taken in conjunction with his real and apparent inferiority make him appear so ridiculous that I am more inclined to laugh at than he angry with him.'

'O, you can afford to be philosophical,' replied his friend, 'you are his equal in wealth.'

'But not in birth,' said Charley, smiling, 'at least, according to his standard. The honorable Mr. Harrison thinks me as much, or more his inferior than he esteems you to be. Have you forgotten the ineffable and unutterable contempt with which he called out, on one occasion when I had received at the hands of our school-mates some petty honor which he considered due to his super-eminent station and abilities, 'Charles Foster, the son of a Carpenter!' '

'Well,' remarked Walter, 'if your father is a carpenter he has made a large fortune honestly at the trade, and he has won an enviable position in the community by his energy, strong sense and strict integrity. No man in the county possesses the respect and confidence of his fellow-citizens to a higher degree. You have nothing to be ashamed of in him.'

'To be ashamed of,' repeated Charley, warmly; 'I reckon not. It would take a great deal to make me ashamed of my own father. I hope he may never have any more cause to be ashamed of me than I have to be ashamed of him.'

'Halloa! there boys we've been looking for you for an hour,' cried some of their school-mates approaching from the academy. 'You've missed all the fun. The girls got around Mr. and Mrs. Reed after school, and teased them out of their consent to have the 4th of July ball we'd all been talking about. They've agreed to give up to us, after the examination, the school-rooms and parlor and dining-room, and let us arrange everything as we wish. We're to have fire-works and dancing; and Mr. Reed has promised to show us the Magic Lantern, and all sorts of curious and pretty chemical experiments.'

'Quite a medley,' said Walter, smiling sarcastically, at what he thought the childish enthusiasm of the speaker

'Indeed,' said Charley, manifesting a cordial interest in the subject, 'tell me all about it. I am sorry I was not there.'

'O, there is not much to tell, besides what I have already told,' replied the boy. 'There will be a meeting Monday morning before school, to arrange the programme of the entertainment; and if you intend to take part in it, Foster, you had better get your cash ready; for we will have to fork up to the young ladies then, and after the collections are made they will determine, with Mrs. Reed's assistance, what part of the funds must go for the fire-works and what part for refreshments.'

Page 7

'Let me see what money I have,' said Charley. 'I have been rather extravagant this quarter, and fear I haven't much, and I would not like to go to my father for more, as his allowance is so liberal.' Then taking out his purse he counted the coin out upon his left palm in quite a business-like manner.

He counted ten dollars and a few cents. 'That will do,' said one of the boys; 'I heard Bob Harrison say he meant to give ten dollars.'

'Do, pray, Charley,' said a little boy of the party, 'if Bob Harrison is going to give ten dollars, you try to give twenty just to fret him and make him ashamed; he thinks himself so much richer than anybody else.'

'If I had as much, and it was necessary, Jim, I would willingly give it to contribute to the amusement of the scholars,' replied Charley, 'but not for the purpose of fretting Bob Harrison; he finds enough to fret at without my assistance; and if I should attempt any experiment upon his disposition it would be to make it more amiable.'

After this little dialogue, the boys separated, the new comers to go in search of whortleberries, and Charley and Walter to return to the academy.

When they were alone, Charley remarked to his friend, 'I am glad Mr. and Mrs. Reed have consented that we may have the ball. I expect to enjoy it finely; don't you?'

'I care very little for such things, and do not expect to remain to it,' was the reply.

'Fie!' said Charley, 'you should not be so unsociable. I am afraid that you will end by becoming a misanthrope.'

'It is not that I am unsociable,' replied Walter, 'but between me and every social pleasure my cursed poverty is constantly coming in. Often when you wish me to make a visit with you, I am compelled to decline because my every day-clothes are not good enough to wear, and I dare not wear my single Sunday suit so often, for fear of wearing it out. And now when you and Robert Harrison and others are giving ten dollars apiece to this ball, behold the munificent donation I am prepared to make. So saying, he put his hand deep down in his pocket and drew out a solitary ten cent piece, which he laid in bitter mockery on his open palm. 'When Monday morning comes, I shall be absent from the conference, and so shall witness none of Bob Harrison's impertinence when my name is called, and see nothing of the pity or contempt which the various countenances will express when it becomes apparent that I am not able to contribute to the general pleasure. Charley, do you wonder that I am unsociable?'

'Walter,' said Charley, deeply moved, 'you bear your misfortune too hard; and you are too proud. Why will you not let me help you? I have a plenty for us both; and it would give me more pleasure to share what I have with you than to spend it entirely on myself.'

'Come, Charley Foster,' was the reply, 'you know that you have already loaded me with presents which were offered with so much delicacy and tact that I did not know how to refuse them. I have quite a respectable little library bearing on the fly leaf of each handsomely bound volume, "To Walter Maynard from his attached friend C. F[.]"; also a valuable gun, and many little things of less value. You have never insulted me yet by offering me money, and I hope you never will; but you have cunningly contrived on many occasions to cover my apparent parsimony and real poverty over with your generosity and liberal expenditure. If you have forgotten these things I have not, nor will I ever. If my voice should ever be raised to denounce you I pray that speech may fail me forever; and if my hand should ever be lifted against you, I trust that it may be stricken from my shoulder.'

Such warmth, and I might add generous emotion; was very unusual with young Maynard, and their exhibition surprised and moved Charley strongly. 'All this is nothing, Walter,' he said, grasping his friend's hand. 'I value your friendship far above such trivial things as money and property, and would delight in rendering more substantial service if you would let me.'

Page 8

CHAPTER II.

Monday morning found the whole school, composed of about a dozen boarders and twice as many day scholars, assembled in the girls' school-room to discuss the subject of the contemplated fete, and arrange the programme of the evening.

Bob Harrison, whose native impudence stood him in need of many a better quality usually considered essential to success among men, had contrived to make himself chairman of the meeting; and seated in a large arm-chair upon the estrade, with an air of dignity and self-importance very disproportionate to the occasion, one pen thrust in the mass of whitish-yellow hair behind his ear, and another awkwardly suspended between his thumb and fore-finger, cut a most ridiculous figure. Charley Foster, at no great distance, with a dry smile of quiet amusement on his counteuance, was slyly making a sketch of him in his Latin exercise book, for the benefit of Walter Maynard, who was the only one of Mr. Reed's pupils absent on this interesting occasion.

After having brought the meeting to order, the chairman proposed that the roll should be called, and that each one in answering to his name should mention the sum he or she desired to contribute to the proposed ball, said name and sum to be immediately recorded by the secretary. To this proposition no objection was made and he proceeded with the measure. When Charley's name was called, he answered promptly, and named five dollars as the amount of his contribution. At this announcement, the august chairman elevated his heavy eye-brows, and glancing significantly around the room, with a supercilious smile, said something in an audible whisper to the secretary about 'not expecting blood out of a turnip.'

Charley's fine face flushed, and his merry eyes emitted an angry flash, but it was but momentary; the scene struck him as so ludicrous that involuntarily he burst into a laugh of derision, in which the whole school, except Nellie Gardiner, joined. She was too ashamed and indignant at her cousin's conduct to feel like merriment; and fixing her beautiful eyes earnestly on his countenance, said in her soft, sweet voice:

'Cousin Robert, how can you be so rude?'

Totally unabashed by this demonstration, and maintaining unmoved his imposing dignity, the chairman called the meeting to order, and went on calling the roll. Everything now went on quietly until Walter Maynard's name was called, when some officious body called out, 'Absent.'

'Aha!' exclaimed Mr. Harrison, with a knowing look, 'we all understand the gentleman.'

Thoroughly aroused at this indignity offered to his friend, Charley sprang to his feet, and said hastily: 'Walter is preparing his Greek for recitation; it was inconvenient for him to be present, and he commissioned me to act for him. Write five dollars opposite his name; I will hand it in with mine, to the secretary, at the close of the meeting.'

After this, nothing occurred to mar the general harmony, and Mrs. Reed coming in soon after to assist in their deliberations, everything was satisfactorily adjusted.

The fourth of July arrived in due season, though, to Mr. Reed's impatient pupils, old Time seemed to halt on this stage of his journey. The school exercises for that term were completed, the trying examinations were over, and the delightful bustle of preparation for the fete, which had afforded so many charming episodes to the young ladies and gentlemen of the academy, was ended.

Page 9

The grounds were brilliantly lighted by colored lanterns, ingeniously constructed of wooden frames, covered with tissue paper, hung among the boughs of the trees. The school-room, newly white-washed and scoured for the occasion, and ornamented with garlands of flowers and evergreens, was set out with long tables, bearing, in the most tasteful arrangement imaginable, a sumptuous repast. And the parlor and dining-room of the academy building, tastefully adorned with vases and garlands of flowers, and appropriate mottoes formed of evergreens, were prepared for dancing, a couple of negro fiddlers occupying a litle platform in the hall between the doors opening into each room.

The young gentlemen of the academy, and many of their friends who had arrived early, in all the glory of their best broad-cloth coats, white pants and vests, and kid gloves, were standing about the doors, or in the hall and parlors, awaiting the descent of the charming nymphs, who, in an animated buz of conversation and laughter, and a delightful rustle and flutter of drapery, were arranging themselves for the ball in the dressing-rooms up stairs.

What charming things are youth and beauty--or even the youth without the beauty! For what does one care for beauty when the rich young blood, unparched by fever, and unchilled by age, is dancing through the veins to the rapid measures of unheard, but not unfelt soul-music, whose inspiriting strains vibrate with intoxicating rapture upon every joyous nerve; when the fresh young brain, untaxed by thought or care, teems with quick intuitions and joyous fancies; and when the buoyant young heart, which has never felt the dull, heavy aching of anxiety, or the paralyzing grasp of fear, bounds in a joyous harmony with the thrilling pulses through days of unclouded sunshine and nights of soft slumber and heavenly dreams! How intensely do the young enjoy the pleasures suitable to their years! yea, how intensely do they enjoy everything which is in the least enjoyable! And how refreshing is the contemplation of their happiness to their elders, whose weary heads and tried hearts, robbed by time of the capacity of originating joy, are forced to receive it at second hand, by reflection, as it were.

Some such remark as this Mr. Reed addressed to Mr. Foster, senior, who was standing beside him in one of the parlors, watching his son and several other youths arranging for a dance and urging the musicians to strike up as the surest method of hastening the advent of the young ladies. They were indeed an animated and merry party. Charley was radiant with happiness, and even Walter, who had been prevailed on by his friend to be present, showed in his air and manner an unrestrained gayety and satisfaction as new to him as it was becoming. He was indeed looking extremely handsome and good-natured. For happiness is a great beautifier, as well as a great moral power. Who ever thought a happy countenance homely? or what happy man ever committed a crime?

Presently, to the great delight of the impatient young gentlemen in attendance, there was a flutter of drapery on the stairs, which announced that the girls were about to descend to the parlors; and in a few moments they hove in sight, preceded by certain benign-looking mammas and aunts who had come to the hall professedly to give character and propriety to the entertainment, but who were really almost as much interested in the contemplated amusement as their young relatives themselves. And when the procession of blushing, smiling Hebes at length entered the beautifully decorated rooms, what a lovely picture they made, with their bright eyes and coral lips, round arms and snowy necks. How beautiful was their shining hair, wreathed with garlands of leaves and buds. And how captivating their supple, delicately-rounded figures looked draped in fleecy muslin, whose snowy whiteness was only relieved by girdles, or sashes of pink or blue ribbon.

Page 10

The foremost in this galaxy of youth and beauty, undoubtedly, was Nellie Gardiner. So Charley decided at once, and he whispered as much to Walter as arm-in-arm they started to join her on the other side of the room. She was leaning on the arm of her mother, a delicate, elegant-looking woman, whose bearing was very aristocratic, and whose manners, otherwise affable and ladylike, were tinged with haughtiness, and was pointing out to her the decorations.

'There is the flag you made, mamma,' she said, pointing to the mantel, which was ornamented by the bust of Washington draped in the American flag. The august brow of the Father of his Country was crowned with laurel, and on the wall behind, at a little distance above, was written in living green, 'The American Union,' while a rich garland of English ivy, running cedar, and tissue-paper roses, enclosed both the motto and the bust. Around the room were festoons of flowers, and similarly formed mottoes equally patriotic and appropriate.

Mrs. Gardiner was admiringly inspecting and approving, when our young friends approached. Charley, who was a neighbor and a particular friend of Bernard's, knew her well, but Walter had to be introduced.

She received her son's friend very graciously, and holding out her hand to Walter, said:

'I am happy to make your acquaintance, as I know many of your family. Your Uncle Horace is a particular friend of mine; and I also know your aunts, though I have not met with them recently. Are they here to-night?'

'My Aunt Emeline is present,' said Walter, glancing around the room, 'and will be pleased to meet you. There she is, now, entering the room with Mrs. Reed; shall I bring her to you?'

'We will go to her,' said Mrs. Gardiner, with a smile, and leading the way.

Miss Emeline Maynard belonged to that interesting class of society denominated 'old maids,' and was, moreover, one of the most exaggerated specimens of her class. What was her age it is impossible to say, since that interesting fact, if it was ever recorded, must have been registered among the Apocryphal books of the family bible, it was so very 'uncertain.' The landmarks which time had set upon her face and figure, were utterly ignored and stoutly contradicted by the manners and costume of the lady herself. In her youth, allowing that to have passed, she must have possessed a certain kind of beauty, such as is constituted by plumpness and fairness and vividness of coloring; but the wear and tear of life had greatly impaired, if they had not wholly destroyed it. There was in her countenance none of that higher order of beauty begotten of a cultivated and elevated mind and a heart warmed by the noblest and gentlest affections of humanity; for Miss Emeline's thoughts and desires were all 'of the earth, earthy.' To disguise from others the poverty which was painfully and constantly perceptible to herself, and to secure a husband, had been, from her early years, the chief end and aim of her existence; and although so far unsuccessful, yet, with a diligence and perseverance which, if exerted in a better cause, would doubtless have immortalized her, she was still pursuing the same ends. An occasion offering such opportunities as the present, did not often present itself to her, and she was making the most of it. When Mrs. Gardiner approached her, she was standing between Mr. Tomlin, a spry widower, whose two daughters were among the academy pupils, and Mr. Sloan, Mr. Reed's assistant twisting her yellow neck and shaking her shadowy, lustreless ringlets with as many coquettish airs and graces as a girl of sixteen. Accustomed though she was to such exhibitions, Walter could not fail to be disgusted, and a shadow passed over his countenance as he approached her. She was flattered by the notice of a lady so wealthy and aristocratic as Mrs. Gardiner, and for a moment loosened her hold on the

Page 11

patience and politeness of the gentleman, who took advantage of the opportunity to escape to the vicinity of some of the oldest and fairest of Mr. Reed's pupils.

The fire-works were to be exhibited early in the evening, as the moon would rise later and its beams would greatly mar their effect. So, as soon as the guests were assembled, the signal was given, when they all repaired to the porches and grounds to witness their exhibition When Walter had offered his arm to Mrs. Gardiner to conduct her to his aunt, Charley had very gallantly offered his to Nellie for a promenade; and, therefore, he had the pleasure of conducting her to a rustic seat in the grove, and remaining there with her for an hour during the pyrotechnic exhibition. Walter, who entertained no particular fondness for the fair sex, and whose fastidious taste found something to object to in every one of his young lady acquaintances, except Nellie, was a little chagrined at this; but he had made up his mind, very heroically, to do his duty by escorting his Aunt Emeline, when Charley's father relieved him of the unpleasant necessity by offering his arm to Miss Maynard.

Foster fils, who is pretty well known to the reader, was simply a revised and improved edition of Foster pere, who is just being introduced. There was a striking resemblance between them in face, figure and carriage, and also in language and manners, except that the superior advantages of education and society which Charley had enjoyed, told in his favor. But though the early years of the elder gentleman had been passed in decent poverty and moderate toil, yet about him there was no coarseness or rudeness to offend the most tastidious. His code of etiquette, suggested by a good mind and a good heart, was sufficiently refined to please in any society, and his language, simple and terse, was generally correct. His simple, innate dignity, straightforward frankness, and unpretending naturalness, afforded a most striking contrast to Miss Emeline's silliness and affectation.

Finding himself thus pleasantly relieved of the care of his aunt, Walter set off to seek Charlie and Nellie, and soon joined them in the grove.

When the pyrotechnic exhibition was ended, the dancing commenced, and was continued several hours after which supper was served; and then Mr. Reed exhibited the Magic Lantern, Drummond Light, &c. Altogether, it was a charming evening, and destined to be remembered as among the happiest in the lives of several of the personages in our story.

During the evening, Charley had extracted a promise from Miss Emeline that Walter should return home with him from the academy and spend several weeks with him. And that lady, pleased with his manners and bearing, and with his father's attentions, without which she must have made an awkward appearance, had also invited him to make Walter a visit during the holidays.

The farm on which Mr. Foster had resided ever since his retirement from business in Richmond, was situated about five miles from that city, near the Mechanicsville turnpike, in an angle formed by the Chickahominy River, on 'Swamp,' as it is called in that vicinity, and the Beaver Dam Creek, a tributary of the Chickahominy. Mrs. Gardiner's estate was located several miles lower down on the 'Swamp,' and beyond the Beaver Dam; and as Charley had no brother and Bernard was an only son, they, being schoolmates, were often together, and greatly attached to each other, though the latter was some four years younger than the former. During Walter's visit to his friend's, they were almost constantly at Mr. Gardiner's, when Bernard was not with them; and a glorious time they had of it, hunting along the banks of the Chickahominy and Beaver Dam, or fishing in those streams or in the pond at Ellyson's Mill, where many nice chub and silver perch were caught. Of course they saw a great deal of Nellie during this time She frequently made one of the fishing party, and they rode together on horseback almost daily. It would be superfluous to say how much her presence enhanced their pleasure on such occasions; and useless to state how deep were the impressions made upon their young hearts by such delightful and unrestrained intercourse, out in the still, deep forest, beside the rippling waters, and under the bright, warm summer

Page 12

skies. Three of them, at least, never forgot those charming rides along the smooth country roads, edged with green turf and brilliant wild flowers, and bordered by strips of noble forest, or by straggling rail fences covered over with the magnificent trumpet vine and the luxuriant branches of wild grape and sloe vines. Nor could they fail to remember those delightful rambles along the Chickahominy, when they amused each other by tracing resemblances to Indian warriors and wigwams, in the high, fantastic roots, and gnarled, knotty trunks of the venerable trees around them, which had once shaded the Red Men of the forest, and exercised their memories by narrating such legends and local traditions as had been handed down to them, or their imaginations by weaving little fictions of their own; while Nellie twined garlands of ferns and wild vines, and the boys rippled the dark bosom of the murky, sluggish stream by casting into it little muscle shells gathered along its banks. And in after years, above the richest strains of music, or the deafening roar of cannon and the ceaseless rattle of musketry, each of them could recall the drowsy hum of the mill-wheel, borne to their ears on the the soft summer air as they sat on the shady hill-side, with their corks floating idly on the dark waters edging the woods, while the setting sun lit up the broad bosom of the pond with gorgeous rainbow tints, and the soft, sweet sounds of the closing summer day, rising up from the water and the woods, blended in one deep, rich vesper hymn of praise to the God of Nature.

When, after four weeks spent with his friend, Walter was returning home, Charley determined to accept Miss Emeline's invitation and accompany him. His father, who had happened once accidentally to dine at Poplar Lodge, the residences of the Misses Maynard, did not give a very favorable account of the commissariat of the establishment, and Walter had hinted that his aunts were very economical housekeepers; but this did not deter Charley, who laughingly replied to his father's warning by saying that after feasting as he had done all vacation, he could afford to live one week, like a bear is winter, by sucking his paws.

'Well, my son, you must not let the ladies see you at it,' said the old gentleman, 'for whatever is lacking in bread and meat is made up in etiquette and style. None but the best manners will be tolerated there. Have you never noticed how very punctilious young Maynard is?'

Poplar Lodge was situated on the south side of the Chickahominy, in Henrico county, bear a point now known as Fair Oak Station, on the York River railroad. It was a nest, snug little place, but very unprofitable to the owners, owing to imperfect cultivation, from the want of sufficient labor, for the Misses Maynard owned no servant except an elderly man and his wife, a half grown boy, and some younger children; and they were not able to hire. Still, with rigid economy, they were able to make quite a genteel appearance. The little square yard which surrounded the house was bordered, inside of the white palings enclosing it, by a formal row of Lombardy Poplars, and laid off in narrow gravel walks edged with flowers, which were Miss Emeline's especial care; while the grass plats they enclosed were kept scrupulously clear of weeds and rubbish by the old man servant, who had been gardener for Walter's grandfather in the palmiest days of the family, and who delighted in keeping up, as far as their reduced circumstances would permit, all the style and formula which had then been observed. This same old negro--Uncle Tom he would have been called anywhere else in Virginia, but the Misses Maynard called him Uncle Thomas--was quite a character, and reminded Charley, whom his idiosyncracies greatly amused, of the ingenious and attached butler of the Master of Ravenswood. On the first day of his arrival Charley saw him hard at work in a little corn patch near the house all the morning; but when the dinner hour arrived and he and Walter repaired to their chamber to prepare for the meal, Uncle Thomas brought them water and towels, and insisted on helping them to make their toilettes. He was proceeding to brush the suit Charley had rode in, preparatory to hanging it in the wardrobe, when the latter objected, saying, 'Don't trouble yourself to wait on us, Uncle Thomas; I can wait on myself. I have been doing nothing all

Page 14

"Now, Mars Walter," replied Thomas, reprovingly.

Page 15

day, and am better able to brush that coat than you, who must be tired with working in the sun.'

'Indeed,' said uncle Thomas, with dignity, straightening up his bent figure, 'I'm never too tired to wait on my young master's visitors. I don't hurt myself with work; I ain't obliged to work; nobody ever says work to Thomas. But things here ain't on as grand a scale as I was always used to, and there being so many fewer colored folks than I was raised with, and not so much company with the white folks as used to be, I gets sorter lonesome, and jest works for company like, and to set the youngsters a good example and teach 'em industrious habits. We don't keep many of our people at home now, though. The family was unfortunate some years ago, and we had to sell our large estate on the river, and we ain't got room on this little place for all our men, so we hire 'em out in Richmond.'

'I wish you would bring one or two of them home at Christmas, Uncle Thomas,' said Walter, significantly.

'Now what for, Mars Walter?' replied Uncle Thomas evasively. 'Don't I wait on you well enough--what you want with 'em here?'

'Well, then, just allow me the handling of some of the money they hire for,' said his young master, mischievously. 'I think it is very selfish in you to spend it all on yourself, Uncle Thomas.'

'Now, Mars Walter,' replied Thomas, reprovingly, 'is this the gentlemanly manners me and your aunts has been trying to teach you ever since you was left an orphan to our care, to be misdoubting the word of a colored person, here before strangers.' Then telling the young gentlemen to ring if they wanted anything more, Thomas bowed himself out of the room.

When the boys descended to the dining room, they found him arrayed in a long white apron, with white gloves on and a waiter under his arm, standing gravely behind the head seat of the table, which was set out with a threadbare cloth and napkins of the finest damask, an antique set of rich china, and various pieces of oddly matched, but handsome plate, all of which were heir looms in the family and relics of its former grandeur.

The dishes were very small, and there were but few of them; but there was so much form, such a flourishing of napkins and changing of plates, Uncle Thomas was so imposing, Miss Judith so dignified, and Miss Emeline so affable, that, somehow, Charley, who had felt very hungry after his ride, fortunately lost his appetite completely.

At dinner he had an opportunity to scrutinize Miss Judith, whom he had not met before. She was older than Miss Emeline, and had given up beaux and taken to caps and spectacles. The latter looked up to her, and was evidently regarded by her sister as quite a young person. Family pride was the ruling trait in her character, and the Maynard family her hobby. Charley had not been twenty-four hours in the house before he had had a minute history of every branch of her family for several generations. Walter, who had been educated to think with her on this subject, was much interested in the topic, and delighted with having his ancient pedigree and high connections paraded before his friend, as an offset to the superior wealth of the Fosters.

Charley, whose ideas about such matters were derived from his father, who considered such pride ridiculous, remembered an observation of the latter to the effect that we could all trace our family back to Eve, and she stole an apple, and he came near laughing, inadvertantly, in Miss Maynard's face.

Nor did Miss Emeline's views on this subject entirely accord with those entertained by her sister. She still remembered with regret one or two eligible offers which she had rejected at her sister's instigation; because the applicants for her hand were, to express it in Miss Judith's language, "of plain origin;" and she had mentally resolved that this consideration should never weigh with her again in similar circumstances. Unfortunately, however, we fear that her decision was arrived at too late.

After a week spent at Poplar Lodge, during which he had taken many private notes

Page 16

on the ladies and Uncle Thomas, for the volume on human nature which he was mentally compiling, Charley returned home, The visit, by making him acquainted with Walter's home and relatives, had given him an insight into the character and conduct of his friend which he had never had before. He saw that the cold, hard atmosphere of the false life at the Lodge was not favorable to the growth of those amiable social virtues which, in spite of his partiality, he had mentally acknowledged young Maynard to be deficient in; and he pittied more than he blamed him for the want of them, and resolved, by redoubled affection and kindness, to atone, as far as lay in his power, for the sternness of Miss Judith and the indifference of Miss Emeline.

While the young gentlemen had been amusing themselves as we have described, their families had been preparing for their departure to West Point; for Mr. Foster had yielded to his son's entreaties and consented that he might complete his education there.

The time had nearly arrived for them to leave, and after a few farewell visits made in company, including a very pathetic leave-taking of their former teachers and their favorite haunts about the old academy, they set off on their journey, and were joined in Richmond by Bob Harrison, who was going to the same institution. Neither Charley nor Walter was particularly pleased to have his company; but he was somewhat subdued by the recent parting with his family, and a little cowed at the idea of going among strangers, and so was more endurable than they expected him to be. Still the boys contemplated, with much pleasure, the taking-down that awaited him at West Point.

CHAPTER III.

Four years after the period treated of in the last chapter, on a warm summer afternoon, a hack, or hired carriage, from Richmond, might have been seen proceeding leisurely along the Mechanicsville Turnpike, through a cloud of dust which followed in its track. The two large traveling trunks strapped on behind, a couple of portmanteaus upon the boot, and the same number of well filled carpet bags on the front seat of the coach, indicated that the two handsome young gentleman, in cadet's uniform, occupying the back seat, had traveled some distance. And, indeed, they had come a good way, having left the highlands of the Hudson only a few days before; for, in spite of their military dress, their broad chests manly voices and heavy moustaches, we recognize in the travelers our old friends, Walter Maynard and Charley Foster. Their military training had developed their boyish forms into models of manly strength and vigor, and though Charley was still taller and stouter than Walter, yet there was in the lithe figure of the latter a supple grace very pleasing. His face, too, was strikingly handsome, though still less pleasing than Charley's; but his countenance had greatly improved in agreeableness of expression since we last saw him. Those four years at West Point had been happy ones for him, affording, as they did, an opportunity for his ambition to feed upon the applause and distinction which his superior diligence and abilities won for him among his fellow students; and he looked and felt in a better humor with the world than he had ever done before. The two had graduated with honor, but as yet were indecisive in the matter of retaining their commissions in the army. The friendship between them had greatly strengthened during these past four years; and they were dubbed by their mutual friends at West Point, "Jonathan and David." They were, indeed, more like brothers than friends; and the well-filled purse with which Mr. Foster kept his son supplied, ministered alike to the wants of both; for although Walter would not accept money, yet Charley never made a purchase for himself that he did not make a similar one for his friend; and all their furloughs for little excursions to New York, Albany, &c., were always gotten together, when Charley proposed all the amusements and quietly footed

Page 17

the bills. They were now on their way to Beaver Dam, Charley's home, to spend the summer months.

Walter was leaning back in his corner of the carriage, with his aristocratic little feet crossed on the seat before him, and one hand lightly and gracefully supporting a cigar at which he was slowly puffing away with the practised air of an adept, while with the other he held a daily paper which he was intently perusing. Charley was bending out of the carriage, with the stump of a half extinguished cigar between the thumb and forefinger of his right hand, and amusing himself by whistling to a stray cur which was following them, and talking to the driver.

'Do you hear that, Walter?' he said, turning suddenly and addressing himself to his friend. 'This uncle says that his wife lives at Mrs. Gardiner's, and that there is to be a large party there to-morrow night, given in honor of Miss Nellie's birthday. Our arrival is just in time.'

'Just out of time, you had better say,' replied Walter. They will not hear of it in time to send us invitations.'

'O, I will see that they are duly apprised of that circumstance,' said Charley, laughing. 'I had intended calling on Bernard to-morrow morning, and I shan't let these tidings deter me, I assure you.'

'How strange and how delightful,' he went on, it is to be back in old Hanover again, with the privilege of staying as long as one pleases. I say, old fellow, you and I ought to be pretty well versed in military doings; we've been kept close enough at it during the last four years--few and far between our furloughs have been. I dare say the girls about here have quite outgrown my knowledge of them. There is Nellie Gardiner that I haven't seen but once in four years, and that was only for a short time during my first furlough. Whenever I have been home since, she was away at school. I wonder how she looks--whether she is as pretty as ever?'

'Look out and see,' said Walter, who had been gazing dreamily down the road, while Charley was talking. 'Yonder comes a little grey pony wondrously like the one Nellie used to ride, and a little lady on it wondrously like Nellie herself, while riding with her is a boy I could swear to be Bernard.'

Just as they reached the Chickahominy, the carriage and the equestrian party met; and there being a good ford below the bridge, the coachman drove into the stream to water his horses at the very moment that Nellie and Bernard chose the same route. They met, therefore, vis-a-vis in that classic stream.

Bernard was the first to recognize them, and cried delightedly, 'Good evening! Sister, here are Charley and Walter come home just in time for your party, as you were wishing only the other day.'

Nellie, at this, looked up with a pleased smile on the same beautiful face they remembered so well, and approaching the carriage with her brother, held out to them the identical little hand, scarcely an atom larger than they had known it, whose gentle clasp sent the same delightful thrill to their hearts as in the olden time, when they were boys and girl together.

A few moments of delightful conversation they had there, with the cool waters rippling softly around the carriage wheels and the horses' feet, the setting sun gilding the tree tops, and a little cool evening breeze which had come up from the Swamp, dallying coquettishly with Nellie's floating veil and glossy hair, when the coachman reminded our travelers that he had to get back to town that night, as his carriage was engaged for an early hour the next morning. Upon this announcement they were preparing to take leave, when Bernard informed them that he had reached the limit proposed by Nellie before starting for their ride, and that as they would be together at Mr. Foster's gate there was no use in saying good-bye yet.

Before they had proceeded far, it occurred to Charley that Bernard was occupying a very enviable position; and his manners being of the freest and easiest, he proposed an exchange of seats. This was readily acceded to, and he was soon cantering along by

Page 18

Nellie's side, as proud and happy as a king is generally supposed to be. The equestrian party soon discovered that the dust from the carriage was unendurable, and rode ahead to avoid it. As Walter gazed down the road after them, looking so handsome and so happy, the first bitter feeling that he had ever felt toward his friend sprang up in his breast. He felt jealous and indignant, and thought that Charley had acted ungenerously. Perhaps he had; but who was ever generous in such a matter?

A beautiful woman never looks so enchanting, so ravishingly beautiful, as on horseback, especially if she rides well; and no woman ever rode more gracefully than Nellie Gardiner. The lingering tenderness for her which had been smouldering in Charley's heart ever since those old days at the academy, was, during that ride, fanned into a flame of love which was destined to burn on the holiest altar in the temple of his heart while life should be granted him in which to cherish human passion. And the glimpses that Walter had that evening of her face and figure, the few tones of her voice which met his ear, and the few glances which fell on him from her melting eyes, kindled, from the ashes of a certain boyish fancy, which had long lain dormant in his bosom, a passion which gave the color to his whole life.

After Mr. and Mrs. Foster had retired for the night, the two friends sat for hours in silence on the porch at Beaver Dam, smoking their cigars, gazing out upon the moonlight, and thinking of Miss Gardiner.

Since they parted with her at the gate, they had not spoken to each other about her, except that Charley had asked--

'Do you think Nellie is much changed, Walter?'

'Only for the better,' was the reply.

'Yes, that is it,' replied Charley, 'only for the better. And what a lovely creature she is--what heavenly eyes, and what bewitching manners! I never saw such graceful ease blended with such charming modesty, or such a beautiful combination of gentleness, dignity, frankness and vivacity in the manners of any woman before; did you?'

'Remember,' replied Walter, curtly, 'that I have not had the same opportunity of observing and analyzing Miss Gardiner's manners that you have, and so am not prepared to pronounce upon them.'

What were their dreams that night, and their waking thoughts the next day up to the time when they set off to the party, to which they had received the most pressing invitations, we will leave the ingenious reader to imagine.

Mrs. Gardiner's residence, as we have said, was but a few miles from Beaver Dam, and situated on the Chickahominy. It was a large wooden building, furnished inside with richness and elegance, and surrounded on the outside by extensive grounds laid off and ornamented with great taste. To-night, the whole house and a large part of the grounds were ablaze with light; and the numerous carriages and horsemen dashing down the avenues and sweeping around the circular carriage drive before the house, the groups of men on the porches, and the glimpses of ladies caught through the partly drawn curtains of the brilliantly lighted dressing-rooms, formed a most animated scene as our two embryo lieutenants approached it.

Before repairing to the dressing-room to adjust their locks and remove from their shining broad-cloth any dust which might have accumulated there during their ride, they stopped on the portico to salute some old school friends. After a short time thus spent in friendly converse, they entered the parlors, which they found quite full.

The matrons and maidens of the Old Dominion were nobly represented by the fairer portion of Mrs. Gardiner's guests. Every style of female beauty was to be seen there, from the calm, fully matured woman, whose manners and mind had been formed by years of intercourse with the world, to the blushing maiden just budding into womanhood--from the dark brunette, with raven hair and eyes of night, to the fairest blonde, whose golden ringlets shaded sapphire eyes and brow of alabaster. Among this shining galaxy, our young heroes thought now, as they had done four years ago, at the Fourth of July ball, that none could compare with Nellie Gardiner. Nor were they alone in

Page 19

this opinion; for many of the most elegant men in the room were paying their homage at the same shrine; and even the most envious of her own sex could not fail to perceive and were compelled to acknowledge her charms.

She was indeed looking peerlessly beautiful to-night, with her fairy-like figure, draped in a cloud-like robe of embroidered white crape, a berthe of valenciennes lace looped up on her bosom with a pearl breast-clusters of blush roses in her dark brown hair, and pearl bracelets and necklace melting into the whiteness of her beautiful neck and arms. Her large dark eyes, of a deep violet color, and shaded by long curling lashes of the same hue and shade as her hair, were at once so soft and bright, that every glance thrilled the observer with a strange pleasure, and to-night they were fairly aglow with joyous excitement, while her small mouth and exquisitely moulded chin were wreathed and dimpled with happy smiles. Young, wealthy, beautiful, admired and beloved, just entering upon a life which promised so much joy, why should she not be happy?

Foremost among Nellie's admirers to-night, was her cousin, and our former acquaintance, Bob Harrison, or Mr. Robert Harrison, as he would doubtless desire to be called. Time, which effects so many changes had not failed to leave its impress on Bob Harrison; though outwardly he was somewhat improved, there was no change for the better. At West Point he had associated with the most immoral and dissipated set of cadets connected with the institution, and had committed many rude and disgraceful acts, which, if ventilated, would certainly have procured his expulsion from the academy.--Indeed, he had barely escaped being expelled more than once. He got through at the examination, however, taking a very low figure, and escaping disgrace by the very skip of his teeth--yet he passed, as did also, at a previous date, Pope, Burnside, Hooker, and several others of similar mental calibre, who have lately occupied conspicuous positions in the eyes of the world. He expected to make arms his profession, and as his family was wealthy and influential, there was no doubt about his getting a convenient position in the service, though he was a most unprincipled and worthless vagabond. Nellie had never admired him, but as the oldest son of her mother's only brother, she could not help feeling an interest in him and some regard for him. Still, she was not inclined to submit to his monopolizing her society entirely, as he seemed inclined to do, and she contrived to dispense her favors quite equally among her numerous admirers.

Lieutenant Foster, who went into any matter that engaged his attention with his whole soul, contrived to obtain quite a liberal share of her smiles; and Maynard, who was equally energetic, though less enthusiastic, succeeded in securing her hand several times during the dance, and had quite a delightful tete-a-tete during the evening. They were both perfectly satisfied with the progress they had made, and, intoxicated with bliss, returned to Beaver Dam just before dawn to dream of Elysium.

The party at Mrs. Gardiner's was followed, within the next few weeks, by half a dozen others, including one at Mr. Harrison's residence, on the Pamunkey river, and one at Mr. Foster's. Several of Nellie's school-mates were visiting her, and Mrs. Gardiner's house was constantly thronged with company, among whom might be found, almost daily, Walter and Charley. True, they found time occasionally, in the intervals between dinners and tea-parties, the pic-nic excursions, and rides and walks upon which they were constantly attending Miss Gardiner and her friends, to ride over to Poplar Lodge and pay their respects to the ladies, and cultivate the acquaintance and good will of Uncle Thomas.

Walter, whose penetrating eye had long been accustomed to read every feeling and thought of Charley's transparent soul, had seen a rival in him from the beginning, and in view of his fine pecuniary prospects, handsome person, and fascinating manners, considered him quite a formidable one. But Charley, blinded by the intensity of his own passion, failed to penetrate the cold, calm exterior of his undemonstrative friend. Accustomed for years to confide to Walter every opinion and emotion, Charley would have confessed his love for Nellie and sought his sympathy, had he not considered it a matter too sacred to be discussed with a third party.

Page 20

As for Nellie, herself, it was impossible to discover, from her manners and conduct, which one of her numerous admirers, if any, had received her heart's election, for though too pure and dignified to condescend to coquetry, yet the kindness of her nature, and the politeness of her manners, led to such an equal distribution of her favors, that each one was left in doubt whether he was not the favored one.

This being the condition of affairs, when Mrs. Gardiner, Nellie and Bernard, Bob Harrison, and some others among their intimate friends, proposed, several weeks after the party, to visit the Virginia Springs, Charley determined to accompany them; and with his usual generosity, invited Walter to go with him. Knowing that his friend's whole soul was enlisted in his suit with Miss Gardiner, and determined to supplant him, if possible, Walter accepted the invitation and submitted to have his expenses paid by his rival that he might bask in the smiles of his mistress.

At the springs new triumphs awaited the Hanover belle, as Nellie was termed. Scores of lovers were added to her train, and so closely was she besieged by their attentions, that it was only by the utmost assiduity that her old friends could sometimes secure her hand for a dance, or her company for a promenade. Yet, the rarity of this pleasure so enhanced its delight, that the party found the time pass rapidly and pleasantly, till the chilly air of September made a longer stay among the mountains undesirable, and hastened their departure for their homes.

In the whirl and excitement of the public life at the watering places, but little opportunity had offered for private love-making, and the relations sustained between our young friends had therefore remained in statu quo. But a few days after their return, Walter, who was then at Poplar Lodge, received a communication from the War Department, summoning him to repair immediately to Washington to receive his commission and he assigned to duty. As his absence would doubtless be a long one, and his location probably very distant, he resolved to see Miss Gardiner before setting out on his journey, and confess his love and tender her the offer of his hand. With this view, he arrayed himself in his most befitting costume, and mounting his horse, set off for Fairfield, Nellie's home.

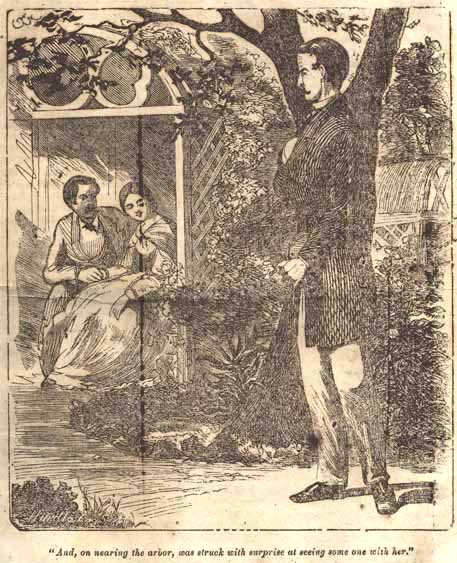

When he arrived, the servant who met him at the door, replied to his inquiry whether his young mistress was in, by saying that she was at home, but not in the house. She had been walking in the garden, and was now sitting in the honey-suckle arbor. Thinking that this was a most suitable place for the purpose he had in view, Walter declined entering the house, and resolved to join her there. The location of the honey-suckle arbor was well known to him, as he had often sat there with the ladies, it being a favorite resort of the Gardiners and their guests. So, walking leisurely, with his usual noiseless tread, he threaded the labyrinth of walks leading through a wilderness of shrubbery to his lady's bower.

In the trepidation of his spirits, he had forgotten to inquire whether she was alone, and on nearing the arbor, was struck with surprise at seeing some one with her. But it was not simply disappointment at finding the opportunity he had desired for his declaration postponed that rooted him breathless to the spot. Nellie's companion was his most dreaded rival, Charley Foster: and he saw, at a glance, that the tones which were trembling on his lips were then being breathed into her willing ear by a voice whose witchery he had reason to dread. And the hand which he would have given worlds to call his own, was at that moment trembling in the warm clasp of his rival, who bending forward, with his eloquent eyes fixed on the maiden's face, was saying, in a deep voice, tremulous with emotion:

'I know that it is great presumption on my part. I am not and can never be worthy of you, but all that I am, and all that I have, the whole homage of my heart, the devotion and service of my life, I lay at your feet; Nellie, will you accept them?'

The girl's red lips, slightly parted, were quivering nervously, and the long silken lashes of her downcast eyes swept her cheeks, crimson with blushes; but calming her trepidation,

Page 21

"And, on nearing the arbor, was struck with surprise at seeing some one with her."

Page 23

she raised her large eyes, melting with tenderness, to her lover's face, and said in a soft tone, scarcely audible: 'It is the most precious boon that earth could offer me; I accept it with pride and pleasure.'

An expression of ecstasy lighted up Charley's face.

'My own!' he exclaimed, in his deep, tender voice, pressing the hand he held passionately to his lips; 'my own!'

'Yes, forever,' murmured Nellie.

Young, and fair, and graceful as they both were, they made a beautiful tableau in that attitude, with the golden autumn light playing over them, and the flowering branches of the honey-suckle twining around them.

A scene so exquisite as the one we have attempted to describe, would, if acted on the boards of any theatre in christendom, have elicited down thunders of applause from the most intelligent and discriminating audience ever assembled; but no sound escaped the single spectator, who stood transfixed. With emotions, such as Satan is supposed to have felt, when lost and undone he gazed upon the beauties and the bliss of Eden, Walter looked upon the tableau before him, then noiselessly retracing his steps, left the garden, with a heart as heavy as the one Adam bore with him from Paradise.

Arriving at the house, he entered the parlor, and taking up a book, pretended to read, while he awaited Charley's and Nellie's return.

In about half an hour they came in, looking very bright and happy, and quite pleased and surprised to see him there.

He met them with his usual calmness and self-possession, and seemed quite as cordial as ever. The keenest eye could not have discovered in his serene exterior any trace of the volcanic fire of passions surging and flaming in his breast. Wildly as he loved Nellie Gardiner, he felt towards her the keenest resentment, that she should have preferred another to him; and oh, how he hated Charley Foster. Yet, he disguised it all, and sat with them nearly an hour, discussing the most ordinary topics in the most commonplace manner. When he arose to take his leave, he said to Nellie:

'I have been summoned to report in Washington to be assigned to duty, Miss Gardiner, and expecting to leave very shortly, I called this afternoon to bid you adieu. I shall probably not have an opportunity of visiting Virginia again very soon, and so shall not have the pleasure of meeting you again in a long time; but permit me to offer you my best wishes for your happiness in saying farewell.'

'And you, too, Charley, will accept the same,' he added turning to Charley, without heeding the expressions of surprise and regret they were both uttering.

'Oh, no, not yet,' said Charley; 'return home with me and spend the night at Beaver Dam, and stay with me until you leave for Washington.'

'I shall leave to-morrow, before dawn,' replied Walter, 'and so cannot accept your invitation, though I thank you for it.'

Charley followed him out upon the porch, and clinging to his hand, said:

'I can not give you up,' old fellow; 'I really do not know how to get along without you. But for one thing, I would pack up and be off with you, Write soon and often, for I shall miss you sadly.'

'Oh, you will forget me in a little while,' said Walter, laughing lightly, as he sprang down the steps.

CHAPTER IV.

About two weeks after his arrival in Washington, while he was busily engaged in preparing for service, Walter was surprised to receive the following letter from Charley:

MY DEAR OLD CHUM:--I have concluded not to give up my commission, and write to request that you see Col. B. and endeavor to secure for me, through his influence, an

Page 24

agreeable position in the army. I prefer active service and immediate duty. If such a thing is possible, I would like also to be in the same company, or at least in the same regiment with you. Do, please try and get it so arranged. I would spare you all this trouble by going to Washington myself, if it were not that I sprained my ankle yesterday, while fox hunting.

'And now, knowing that you must be surprised at this sudden decision, and curious to know the cause of it, I will explain it all. You, from whom I never kept a secret before, will be astonished to learn that ever since our return from West Point--yea, as I have lately discovered, ever since I have known her--I have loved Nellie Gardiner, and that on the very evening of your farewell visit to Fairfield, I told her of my love. My confession was very flatteringly received, and she consented to yield me her hand in marriage, if I could gain her mother's consent to our union. In due season I waited on Mrs. Gardiner, and respectfully requested her consent to my forming an alliance with her daughter. My petition was coldly and haughtily received, and peremtorily refused. I respectfully requested to be made acquainted with the grounds of her opposition, when she candidly admitted that to myself, personally, she had no objection, but that the disparity in our rank was too great to make such a connection desirable--she would never consent to have her daughter, in whose veins mingled the blood of four Governors and one President, marry the son of a carpenter.

'You may imagine, Walter, if you can, what my feelings were. However, I maintained my composure; I did not tell her that 'her sex protected her,' but I thought it. I merely reminded her very politely, that the man who maintained toward our Saviour, the relation of an earthly father, was a carpenter. To this she vouchsafed no reply.

'At my request, she consented that Nellie and I should have a parting interview, but she assured me very positively that it must be the last.

Nellie was much grieved at the reception her mother had given my suit, and indignant that I should have been insulted by being treated as an inferior. Her mother, she said, was by her father's will, her legal as well as natural guardian, and that during her minority she would not offend her by marrying against her wish, but that in three years she would be twenty-one years of age, and mistress both of herself and fortune, when she would bestow them on your unworthy friend and humble servant. Of course. I thanked the dear girl with all my heart for her unmerited generosity. We agreed then to wait until she should have attained her majority; and, having the utmost faith in each other, we have no doubt of the final consummation of our wishes.

'This being the condition of affairs, you know that it would not be very convenient or proper for me to remain in this vicinity; hence my sudden decision to enter the army. Of course all that I have told you is in the strictest confidence, for the compact between Nellie and myself is a profound secret, though the affair of my addressing Miss Gardiner, and being rejected by her mother, has been for a week under discussion by the Grundys, through the agency of Bob Harrison, I believe. Nellie informed me at our last interview that he was a lover of her's, and that his suit was greatly favored by her mother and his father.

'Be sure to attend promptly to my request, and let me know the result as soon as possible.

Very truly, yours,

C. FOSTER.'

To this communication Charley received, at an early day, the following reply:

'DEAR CHARLEY:--Immediately on the receipt of your letter, I called upon the gentleman you mentioned, and communicated your request to him. There was no difficulty in getting you an agreeable position, and in a few days you will be ordered to report for duty. You will not be able, however, as you seemed to desire, to enter upon active service in the field, for it has been determined to place in the corps now organizing for the expedition to Utah only such officers, and, as far as practicable, men who have seen service in the field. In order to do this, it is necessary to withdraw the garrison

Page 25

from several of our forts, and substitute raw troops in their place, and among these latter you and I are assigned to duty. Captain Williams, whom you already know slightly, has been appointed commandant at Fort Alexander, in the Northwest; and before I received your letter I had been promoted and appointed First Lieutenant under him. The other lieutenantcies are still unfilled, and Bob Harrison, who has just arrived in Washington, designed applying for the place of Second Lieutenant, but Colonel B. had been before him and obtained it for you, so Bob had to be contented with the junior rank. So, little as we like him, it seems that we are to be associated with him again, Really, there seems to be some strange fatality at work in the matter.

'As for the second part of your letter. I was not so much surprised as you seemed to expect. I must have been blind not to have discovered the state of your affections some, months since. But I must confess that Mrs. Gardiner's conduct did astonish me no little, in view of her apparent partiality for you, and the pleasure she seemed to take in your society. I have heard her refer Bernard to you frequently as a worthy model, and so, I am sure, has Miss Gardiner.' However, I suspect she is influenced in this matter, as she is said to be in many others, by her brother, Mr. Robert Harrison, senior.--He doubtless thinks that it would be a fine thing for the hopeful Bob to step into such a dowry as Miss Gardiner's, with a reversionary right to one half of her mother's splendid fortune. But if he expects to make a useful and worthy member of society of this same hapless scapegrace, he will, in my opinion, be vastly mistaken. Bob himself. I am persuaded, has no idea of such a thing; he seems, judging from his West Point career and his secret exploits in Washington, to be bent only on 'sowing his wild oats;' and I will predict that he 'seeds a large crop' of them, to speak in the agricultural parlance of Old Virginia.

'I hear that he is not much pleased since you and I rank him, and spoke of throwing up his commission, but his friends here told him frankly that nothing better could be obtained for him in consequence of his poor standing at West Point, and persuaded him, if he wished to make arms his profession, to remain where he was. Now, we know very well, that in the choice of his profession, Bob is not at all influenced by bravery or a love of glory, for he is quite innocent in both. He would greatly prefer remaining at home, with nothing to do except spend money; but his father, who has a good many children to provide for, and is said to be heavily in debt is determined to quarter him on 'Uncle Sam.'

'To-morrow I expect to set off for Fort Alexander. Hoping to be joined by you there soon, I remain, as ever,

Your friend,

W. MAYNARD.'