The Confederate First Reader:

Containing Selections in Prose and Poetry, as Reading Exercises

for the Younger Children in the Schools and Families of the Confederate States.:

Electronic Edition.

Smith, R. M. (Richard McAllister), 1819-1870.

Funding from the Institute of Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Christie Mawhinney

Images scanned by

Christie Mawhinney and Katherine Anderson

Text encoded by

Katherine Anderson and Jill Kuhn

First edition, 2000

ca. 250K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) The Confederate First Reader: Containing Selections in Prose and Poetry as Reading Exercises for the Younger Children in the Schools and Families of the Confederate States.

120 p.

Richmond, VA.

Publishshed by G. L. Bidgood, No. 121 Main Street.

1864.

Call number 4083 Conf. (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

This electronic edition has been created by Optical

Character Recognition (OCR). OCR-ed text has been compared against the

original document and corrected. The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Pages 65-72 are missing in the original document; references in the Table of Contents to missing pages are not linked to those pages.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Readers (Primary)

- Textbooks -- Confederate States of America.

- Education -- Confederate States of America.

- Confederate States of America -- Juvenile literature.

- Southern States -- Juvenile literature.

Revision History:

- 2000-09-14,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-08-28,

Jill Kuhn

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-08-17,

Katherine Anderson

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-08-07,

Christie Mawhinney

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

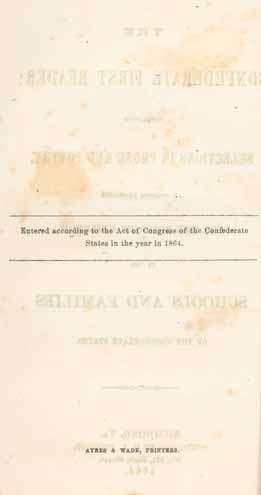

THE

CONFEDERATE FIRST READER:

CONTAINING

SELECTIONS IN PROSE AND POETRY.

AS READING EXERCISES

FOR THE YOUNGER CHILDREN

IN THE

SCHOOLS AND FAMILIES

OF THE CONFEDERATE STATES.

RICHMOND, VA.

PUBLISHED BY G. L. BIDGOOD,

No. 121, Main Street.

1864.

Page 2

Entered according to the Act of Congress of the Confederate

States in the year in 1864.

AYRES & WADE, PRINTERS.

Page 3

PREFACE.

This book has been compiled and prepared for the use of children who may have mastered the reading lessons of the spelling-book. It is more particularly designed as an immediate successor, in this respect, to the "Confederate Spelling Book," which has been so extensively adopted in the schools of the Confederate States.

The pieces have been selected with a view to interest and instruct the pupils, and at the same time to elevate their ideas, form correct tastes, and instil proper sentiments. Whatever seems most desirable for these purposes, among the literary materials that have become public property, has been freely appropriated; suitable articles neither being rejected because familiar to adults, nor novelty sought for its own sake. At the same time, the selections have, by no means, been confined to the hackneyed list. It is believed that the exercises thus chosen, are well adapted to the capacity of those for whom they are designed, and will afford them much more real pleasure, as well as improvement, than the frivolous sentences which some suppose to be the best entertainment for juveniles.

Page 4

TO TEACHERS.

This book is not designed to supersede the spelling-book, or suspend its use. Its leading purpose is to furnish suitable reading lessons for young pupils. It is not believed to be expedient to divide the learner's attention with other exercises, which are better pursued separately and in other books. "One thing at a time" is sound wisdom in study as in other employments.

The first thing to be carefully insisted on, in the young reader, is a clear, distinct articulation. This is indispensable to good reading. The habit of indistinct pronunciation is usually contracted in the early lessons of the pupil, and is ever afterwards difficult to overcome. It results from ignorance of words, or from a drawling, indolent tone, or from a haste which mutilates the words or runs them into each other.

A monotonous style of reading is another errror into which the young reader is very liable to fall, unless closely watched. To avoid this, the lesson must be so carefully prepared that each word can be readily called at sight. There can be no good reading, and no improvement, where the learner must spell his way. Besides being familiar with the words of the lesson, the pupil must also understand its import, and catch its spirit. These will go far to ensure an easy utterance and natural tone, and the proper inflection and emphasis.

It should be borne in mind that a school-reader is not a mere story-book, to be hurried through, as such, and then flung aside for another. But the lessons are to be re-read and dwelt upon until familiarity and practice, aided by the instructions of the teacher, shall enable the young learner to give them a correct rendering.

It is recommended that the lesson be of such length as will permit each pupil to read the whole of it, or at least a large part of it, when the class is called to recite. This repetition will create a wholesome emulation among the pupils, and cause all to profit by the instructions given to each. The teacher should begin the recitation by reading the lesson to the pupils, calling their attention to particular points when necessary.

Page 5

CONTENTS.

- The Bad and Good Readers,. . . . . 9

- The Honest Indian, . . . . . 11

- The Young Mouse--A Fable, . . . . . 12

- The Eagle and the Crow--A Fable, . . . . . 13

- The Sparrow and the Hare--A Fable, . . . . . 14

- Creation of the World--Bible. . . . . 15

- On Behavior, . . . . . 16

- Cruelty Punished, . . . . . 17

- Anecdotes of Parrots, . . . . . 18

- Learn to Swim, . . . . . 20

- The Eagle and the Cat--A Fable, . . . . . 21

- The Birth of Jesus--Bible. . . . . 22

- Filial Love Rewarded, . . . . . 23

- Musical Mice, . . . . . 25

- Monkeys and their Tricks, . . . . . 26

- The Lion and the Mouse - A Fable, . . . . . 28

- The Faithful Dog, . . . . . 29

- The Indian and His Dog, . . . . . 30

- The Good-Natured Dog, . . . . . 32

- The Lark and her Young Ones--A Fable, . . . . . 32

- The Ferocious Dog, . . . . . 35

- Show and Use--The Two Colts--Evenings at Home, . . . . . 36

- How to tell Bad News--A Dialog, . . . . . 38

- The Earth and Its Inhabitants, . . . . .39

- Heaven--Mrs. Barbauld, . . . . . 41

- The Seasons--Mrs. Barbauld, . . . . . 42

- The Creator Greater than His Works--Mrs. Barbauld, . . . . . 43

- The Ten Commandments--Bible, . . . . . 45

PIECES IN PROSE.

Page 6

- All for the Best, . . . . .46

- The Good Boy, . . . . . 48

- The Good Girl, . . . . . 50

- Description of Heaven--Bible, . . . . . 52

- The Good Samaritan--Bible, . . . . . 54

- Crucifixion of Christ--Bible, . . . . . 55

- The Wise Bird and the Foolish Ones--A Fable, . . . . .57

- The Boasting Girl and the Conceited Pigeon, . . . . . 57

- The Echo, . . . . .59

- Against Persecution--Franklin, . . . . .62

- The Prodigal Son--Bible, . . . . . 63

- How to Make the Best of It--Evenings at Home, . . . . .64

- The Discontented Mole--A Fable, . . . . . 66

- The French Youth, . . . . .68

- The Day of Judgement--Bible, . . . . 71

- The Whistle--Franklin, . . . . .73

- Industry Rewarded--Berguin, . . . . . 75

- Mungo Park's Travels in Africa, . . . . . 78

- The Wonderful Chip, . . . . .81

- A Pleasant Surprise--From the German, . . . . .82

- The Lion, . . . . .85

- The Chinese Prisoner--Percival, . . . . .88

- The Heroism of a Peasant, . . . . . 89

- The Resurrection and Ascension of Christ--Bible, . . . . . 91

- Abraham's Plea in behalf or Sodom--Bible, . . . . . 95

- Judah's Supplication to Joseph for the Liberation of Benjamin--Bible, . . . . .98

- Joseph makes Himself known to his Brethren--Bible, . . . . .99

- The Tutor and his Pupils, or Use Your Eyes--Aikin, . . . . . 101

- Little John and his Bowl of Milk, . . . . . 107

- The Little Violet--A Fable, . . . . . 110

- A Friend in Need--Evenings at Home, . . . . . 114

- Christian and Hopeful conducted into Heaven by the Angels--, Pilgrims Progress, . . . . .118

Page 7

- The Little Fish--A Fable, . . . . . 10

- God Sees Me, . . . . . 11

- The Robin, . . . . . 13

- The Squirrel, . . . . . 14

- The Bible, . . . . . 17

- Uses of Arithmetic, . . . . . 18

- Similes--Unknown, . . . . 19

- Trust in Providence, . . . . . 21

- The Way to be Happy - Jane Taylor, . . . . . 22

- Early Piety--Watts, . . . . . 24

- Employment, . . . . .26

- To the Lady-Bird--Mrs. Southey, . . . . . 28

- Old Cato, . . . . . 30

- Kind Words, . . . . . 31

- The Ant Hill, . . . . . 34

- God Seen in All Things--Moore, . . . . . 36

- Contented John--Jane Taylor, . . . . . 39

- Gratitude, . . . . . 40

- The Christian Race--Doddridge,. . . . .42

- The Old Horse, . . . . . 44

- Heavenly Rest--Anonymous, . . . . . 46

- The Rose--Cowper, . . . . . 48

- Elegy on Madam Blaize--Cowper, . . . . . 51

- The Dangers of Life--Mrs. Barbauld, . . . . . 53

- The Ant and the Glow-Worm--A Fable--Anonymous, . . . . . 55

- The Hare and the Tortoise--A Fable, . . . . .58

- The Little Lord and the Farmer's Boy, . . . . . 60

- The Better Land--Mrs. Hemans, . . . . . 64

- The Eyes and the Nose--Cowper, . . . . . 67

- The Battle of Blenheim--Southey, . . . . . 69

- The Doomed Man--Dr. Alexander, . . . . . 72

- My Life is like the Summer Rose--Wilde, . . . . . 75

- The Fall of the Leaf, . . . . . 77

- The Spider and the Fly--A Fable--Mary Howitt, . . . . . 83

- The Cuckoo--Logan, . . . . . 87

- Signs of Rain--Jenner, . . . . . 89

- The Meeting of the Waters--Moore, . . . . . 90

PIECES IN POETRY.

Page 8

- Not ashamed of Jesus--Grigg, . . . . . 93

- Destruction of Sennacherib--Byron, . . . . . 94

- Turn the Carpet--Hannah More, . . . . . 96

- The Sluggard--Watts, . . . . . 101

- What is that Mother?--Doane, . . . . . 106

- Casabianca--Mrs. Hemans, . . . . . 109

- All Nature attests the Creator, . . . . . 113

- The Blind Boy and his Sister, . . . . . 116

- The Dying Christian to his Soul--Pope, . . . . . 120

Page 9

THE

CONFEDERATE FIRST READER.

The Bad and Good Readers.

King Frederick was one day sitting in his palace, when a petition was placed in his hands. The King's eyes being dim, he called upon one of his pages to read it to him.

The boy was the son of a nobleman, but he was a poor reader. He pronounced his words badly, and hurried rapidly over them, in a dismal, sing-song tone. "Stop," said the King; "I cannot understand what you are reading. Send me some one else."

Another page now came forward; but be coughed, and hemmed, and cleared his throat, and uttered his words with a great swelling sound, and drawled them out so slowly, that the King took the paper from him, and told him to go out of the room.

A little girl, whom the King saw helping her father to weed the flower-beds, was next called for, to see if she could read the petition. She first glanced her eyes over it, and then read it aloud.

It was from a poor widow, whose husband had been killed in battle, and whose only son was now sent for, to serve in the army. As the son's health was very delicate, she begged the King to let him stay at home, and follow his business as a portrait painter.

The little girl read the petition with such distinct pronunciation, and such natural tones, and with so much grace and feeling, that tears were standing in the King's eyes when she concluded. "Oh, now I know what it is about!" said he;

Page 10

"but I never would have known, if the young men had read it to me."

The King then sent the little girl to tell the mother that her request was granted. He also employed the young man to paint his own portrait. The King likewise made the little girl's father, his chief-gardener; and as for her, he caused her to be well educated at his own expense. The two pages he dismissed from his service for a year, and told them to employ the time in learning to read.

Let all the children who may read the lessons in this book, study them well, and try to read like the little girl, and not like the two pages.

The Little Fish.--A Fable.

"Dear mother," said a little fish,

"Pray, is not that a fly?

I'm very hungry, and I wish,

You'd let me go and try."

"Sweet innocent," the mother cried,

And started from her nook,

"That seeming fly is made to hide

The sharpness of the hook."

Now, I have heard this little trout

Was young and foolish too;

And so he thought he'd venture out,

To see if it were true.

And round about the bait he played,

With many a longing look;

And, "dear me," to himself he said,

"I'm sure that's not a hook."

"I can but give one little bite,"

Said he, "and so I will."

So on he went, when lo! it quite

Stuck through his little gill.

And as he faint, and fainter, grew,

With hollow voice he cried,

"Dear mother, had I minded you,

I should not now have died."

Page 11

The Honest Indian.

An Indian once met one of his white friends, who lived in a village not far from the Indian's wigwam, and asked him for a little tobacco to smoke in his pipe. The white man took a handful of loose tobacco out of his pocket, and gave it to him.

The next day the Indian came to the village, and enquired for the gentleman who had given him the tobacco. He said he had found a piece of money in the tobacco, and he wished to restore it to the owner.

The person to whom he addressed himself, told him the money was his, for it had been given to him; and that he ought to keep it, and not say any thing about it. But this advice did not please the honest Indian.

He pointed to his breast and said: "I got a good man, and a bad man in here. The good man say, 'This money is not yours; you must return it to the owner.' The bad man say, 'It is yours; for he gave it to you.' The good man say, 'That is not right; he gave you the tobacco, but not the money.' The bad man say, 'Never mind, you got it; go buy some dram.' The good man say, 'No, no, you must not do so.'"

"So I don't know what to do, and I try to go to sleep; but the good man and the bad man kept talking all night, and trouble me; and now I bring the money back I feel good."

God Sees Me.

God can see me every day;

When I work and when I play,

When I read and when I talk,

When I run and when I walk,

When I eat and when I drink,

When I sit and when I think,

When I laugh and when I cry,

God is ever watching nigh.

When I'm quiet, when I'm rude,

When I'm naughty, when I'm good,

When I'm happy, when I'm sad,

When I'm sorry, when I'm glad,

Page 12

When I pluck the scented rose,

That in the pretty garden grows,

When I crush the little fly,

God is watching from the sky.

When the sun gives heat and light,

When the stars are twinkling bright,

When the moon shines on my bed,

God still watches o'er my head.

Night or day, a church or fair,

God is ever, ever near,

Marking all I do or say,

Ready for the judgement day.

The Young Mouse.--A Fable.

A young mouse once lived in a house-keeper's pantry, and had a nice time there. Every day she dined on biscuit, or cold ham, or sugar; and often she got a taste of the sweet meats, Sometimes she would peep into the dining-room; but when the cat was there, she would hasten back to her hole, dreadfully frightened.

One day, the young mouse came running to her mother in great joy. "Mother," said she "the good people of the family have built me a house to live in, and they have placed it in the pantry. I am sure it is for me, for it is just big enough. The bottom is of wood, and it is covered all over with wires. I suppose they put the wires there to screen me from that ugly cat.

"And, mother, there is a little door, just, big enough for me to go in. And they have put some nice cheese inside, just for me; and it smells so nice, that I could scarcely keep from going in, and taking possession. But, mother, I thought I would run and tell you, so that we might go in together, and stay there to-night; for it is big enough to hold us both."

"My dear child," said the mouse, "it is happy for you that you did not enter. This house, as you call it, its a trap, put there to catch you; and if you had entered it, you would never have come out again, except to be fed to the cat, or killed in some other way. Let this teach you never to trust to appearances, and always to ask the advice of older persons."

Page 13

The Robin.

Away, pretty robin, fly home to your nest;

To make you my captive, I still should like best,

And feed you with worms and with bread.

Your eyes are so sparkling, your feathers soft,

Your little wings flutter so pretty aloft,

And your breast is all colored with red.

But then 'twould be cruel to keep you, I know

So stretch out your wings, little robin, and go;

Fly home to your young ones again.

Go listen again to the notes of your mate,

And enjoy the green shade in your lonely retreat,

Secure from the wind and the rain.

But when the leaves fall, and the winter winds blow,

And the green fields are covered all over with snow,

And the clouds in white feathers descend;

When the springs are all ice, and the rivulets freeze,

And the long, shining icicles drop from the trees,

Then, robin, remember your friend!

When with cold and with hunger, quite perished and weak,

Come tap at my window again with your beak,

And gladly I'll let you come in.

You shall fly to my bosom or perch on my thumbs,

Or hop round the table and pick up the crumbs,

And never be hungry again.

The Eagle and the Crow.--A Fable.

A hungry eagle gazed down upon a flock of sheep, and selecting a nice lamb, swooped upon him, and bore him away, bleating, to the forest, before the shepherd could do any thing to prevent it.

A crow that was sitting in a tree, near by, saw what had passed, and was filled with admiration at the action of the eagle. He resolved that he would be a grand bird, too, and pounce down upon the flock, as the eagle had done.

The crow accordingly selected the old bell-wether of the

Page 14

flock, and darted upon him, fastened his claws in his wool, and attempted to fly away with him. He might as well have tried to fly away with the State House.

The shepherd was much amused at the silly crow, for he knew he could do no harm. He now went and caught him as he was entangled in the wool of the sheep; and he clipped his wings, and gave him to his children for their amusement.

This fable teaches us not to attempt what is beyond our capacity.

The Sparrow and the Hare.--A Fable.

A hare, on being seized by an eagle, raised the most piteous cries; for he knew that the eagle would soon tear him to pieces, and devour him.

A sparrow that was sitting upon a tree close by, and saw what had happened, began to make sport of the poor hare, and to laugh at his distress. "Why," said she, "do you sit there and be killed, my fine fellow? Up and away, I tell you! I am sure if you would try, so swift a creature as you are, could easily escape from an eagle."

As the sparrow was proceeding with this cruel raillery, there came a hawk and pounced down upon her, and commenced immediately to pick her feathers off, so that he might eat her.

The sparrow, too, now began to cry for mercy; but the hawk paid no attention to her; and the hare, which was just expiring, called to the sparrow and said, "Just now, you insulted me in my misfortune, and thought yourself very secure. Please show us how well you can bear the like, now that calamity has overtaken you also."

This fable teaches us to sympathize with the unfortunate, and never to make sport of their distresses.

The Squirrel.

The squirrel is happy, the squirrel is gay, Little,

Little Henry exclaimed to his brother.

He has nothing to do, or to think of, but play,

And to jump from one bough to another.

Page 15

But William was older and wiser, and knew

That all play, and no work, would not answer;

So he asked what the squirrel, in winter, would do,

If he spent all the summer a dancer.

The squirrel, dear Henry, is merry and wise,

For true wisdom and mirth go together.

He lays up, in summer, his winter supplies,

And then he don't mind the cold weather.

Creation of the World.

In the beginning, God created the heaven and the earth.

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep: and the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters.

And God said, Let there be light: and there was light.

And God saw the light that it was good: and God divided the light from the darkness.

And God called the light day, and the darkness he called night.

And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night. He made the stars also.

And God created great whales, and every living creature that moveth, which the waters brought forth abundantly after their kind, and every winged fowl after his kind.

And God made the beasts of the earth after his kind, and cattle after their kind, and every thing that creepeth upon the earth, after his kind.

And the Lord God formed man out of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul.

And the Lord God planted a garden eastward in Eden; and there he put the man whom he had formed.

And out of the ground, made the Lord God to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight, and good for food; the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of knowledge of good and evil.

Page 16

And out of the ground, the Lord God formed every beast of the field, and every fowl of the air.

And Adam gave names to all cattle, and to the fowl of the air, and to every beast of the field.

And the Lord God caused a deep sleep to fall upon Adam, and he slept; and he took one of his ribs, and closed up the flesh instead thereof.

And the rib, which the Lord God had taken from man, made he a woman, and brought her unto the man[.]

And Adam said, This is now bone of my bones, and flesh of my flesh. She shall be called woman, because she was taken out of man.

On Behavior.

Do not stare at any one; for to do so, is a mark of rudeness and impudence.

Do not be forward to speak, when strangers or older persons are present.

Do not interrupt a person while he is speaking; but listen with attention and politeness, until he has finished.

Never whisper in company while others are conversing; for it is very rude and impolite to do so.

Be always respectful and obedient, to your parents and teachers, and to all who have the care of you.

Be affectionate to your friends, and kind and obliging to every body.

Never lose your temper with your playmates, or use rough words to them.

Do not rudely contradict any one, or use such angry expressions as I will, or I won't, or you shan't.

Always be very respectful to aged people, and to ladies; and render them attentions whenever there is opportunity.

Do not make sport of the lame, or the afflicted; but rather feel sorry for them, and show them kindness.

Do not be harsh, without cause, to servants, or those over whom you have authority. It is wrong to impose upon the helpless.

Remember that to be a gentleman, a person must have a kind heart, and be of gentle behavior, and polite manners.

Page 17

The Bible.

Holy Bible, book divine,

Precious treasure, thou art mine!

Mine to tell me whence I came,

Mine to teach me what I am;

Mine to chide me when I rove,

Mine to show a Saviour's love;

Mine art thou to guide my youth,

In the paths of love and truth;

Mine to comfort in distress,

If the Holy Spirit bless;

Mine to show by living faith,

Man can triumph over death.

Cruelty Punished.

A chimney-sweep was sitting on the steps of a house in London, eating a loaf of bread, which somebody had given him. A little dog stood near him, looking very wishfully at the bread, and begging for a piece, by all the signs which nature has taught dogs to make.

The boy took a delight in teasing the dog. He would hold out a piece of bread to him, and. just as the animal was about to take hold of it, he would jerk it back.

At last the dog was too quick for the boy, and seized the bread before he could withdraw it. The cruel boy, thereupon, gave the dog a kick under the mouth, that sent him away yelping with pain.

A gentleman on the other side of the street had witnessed the conduct of the boy, and thought he would give him a lesson that would make him reflect upon his cruelty, and teach him to do better in future. So be held out a piece of money, and beckoned to the boy to come over and get it.

The boy ran across the street, and eagerly held out his hand to take hold of the money. But the gentleman, instead of letting him take it, gave him a severe rap over the knuckles with his cane, which made him roar with pain.

Page 18

"What did you do that for?" cried the boy. "Did you not offer me the money?"

"What did you hurt the dog for?" replied the gentleman.

"Did you not offer him the bread? I have done this is to show you how badly you treated the poor dog, and to put you in mind, never to act in such a manner again, For you must remember that dumb animals can feel as well as boys."

Uses of Arithmetic

John wants to know, what three times three,

Added to five times two, may be.

Long has he puzzled o'er the sum,

Nor finds to what amount they come:

Yet he is old enough to know

Much more, and I must tell him so.

Let us ask Charles, for he can count,

And soon will tell us the amount.

Well, three times three are nine, he says;

And five times two, are ten, always.

When ten and nine are thus combined,

Nineteen's the number we shall find.

We ought to add up quick and well,

That what we spend, our books may tell,

And make us saving, to this end,

That we may give, as well as spend.

Anecdotes of Parrots.

Parrots may be taught to utter a great many words and sentences; and they often use them so appropriately, that they almost seem to be gifted with reason.

A gentleman once had a parrot that, every morning, would say to the servant, "Sally, Poll wants her breakfast;" and in the evening would say, "Sally, Poll wants her tea;" without ever making a mistake. Whenever she saw her master coming, she would say, "How do you do, Mr. Anderson?"

This parrot would whistle up the dogs, and drop bread out

Page 19

of her cage to them; but when the dogs rushed up to get it, she would scream at them "Get out, dogs!" and make them run away. She would then laugh at them, and seem to be highly delighted at the trick she had played them.

There is a story told of a parrot that belonged to king. One day a hawk caught her, and was bearing her away, when the parrot cried out, "Poll is a-riding!" This frightened the hawk, and he dropped the parrot. Unfortunately they were just over a river, so that the parrot fell into the water and was in danger of drowning.

As soon as the parrot found herself in the river, she cried out, "Twenty pounds for a boat!" A boatman, who was near by, rescued her and, carrying her to the king, demanded the promised reward. The king told him he asked too much; but as the boatman insisted that the parrot had offered it, the king said he would leave it to the parrot to say how much he should pay him. As soon as he had said this, the parrot spoke up and said, "Give the knave a groat!"

Similes.

As proud as a peacock--as round as a pea;

As blithe as a lark--as brisk as a bee.

As light as a feather--as sure as a gun;

As green as the grass--as brown as a bun.

As rich as a Jew--as warm as a toast;

As cross as two sticks--as deaf as a post.

As sharp as a needle--as strong as an ox;

As grave as a judge--as sly as a fox.

As old as the hills--as straight as a dart;

As still as the grave--as swift as a hart.

As solid as marble--as firm as a rock;

As soft as a plum--as dull as a block.

As pale as a lily--as blind as a bat;

As white as a sheet--as black as my hat.

As yellow as gold--as red as a cherry;

As wet as water--as brown as a berry.

Page 20

As plain as a pikestaff--as big as a house;

As flat as a table--as sleek as a mouse.

As tall as a steeple--as round as a cheese;

As broad as 'tis long--as long as you please.

Learn to Swim.

Every body should learn to Swim. It is not only a delightful exercise, but, by being able to swim, a person may sometimes save his own life, or that of another.

An amusing story is told of a man, who had become so learned that he was called a philosopher; but who had not paid proper attention to other things. He was crossing a river in a ferry-boat, at a place where the passage was not safe; but he was thinking only of his books, and of the pleasure which they gave him.

On the way across the river, the philosopher asked the ferryman, if he understood arithmetic. The man answered, that he had never heard of such a thing before. The philosopher told him he was very sorry, for he had lost a quarter of his life by his ignorance.

The philosopher then asked him, if he had learned mathematics. The boatman smiled, and said he knew nothing about it. The philosopher told him another quarter of his life had been lost.

The philosopher then put a third question to the boatman, and asked him if he understood astronomy. The boatman told him no; that he had never head of it before. The philosopher replied, that another quarter of his life had been lost.

Just at this moment the boat ran on a snag, and began to sink. The ferryman threw off his coat, and got ready to save himself by swimming. He then turned to the philosopher and asked him if he had learned to swim. The philosopher told him he knew nothing about it. "Then" said the boatman, "the whole of your life is lost, for the boat is going to the bottom."

And so, indeed, the philosopher's life would have been lost, if the boatman had not saved him; and the philosopher saw that a knowledge of swimming was of more value at that time, than all his arithmetic, and mathematics, and astronomy.

Page 21

We must remember from this, that while we should learn all we can, and become as wise as possible, we must not neglect common things.

Trust in Providence.

My times of sorrow, and of joy,

Great God, are in thy hand!

My choicest comforts come from Thee,

And go at thy command.

Though thou shouldst take them all away,

Yet would I not repine.

Before they were possessed by me,

They were entirely thine.

The world, with all its glittering stores,

Is but a bitter sweet;

When I attempt to pluck a rose,

A prickling thorn I meet.

No perfect bliss can here be found;

The honey is mixed with gall.

'Midst changing scenes, and dying friends,

Be Thou, my all in all!

The Eagle and the Cat.--A Fable.

One day, an eagle, that was flying along, high in the air, saw what he supposed to be a fine, plump hare, sleeping on a bank in the sunshine.

"Aha! my fine fellow," said the eagle, "you are the very thing I am looking for. I will spoil your nap for you very quickly, and you shall make me a nice dinner."

So he immediately pounced down, swift as an arrow, on the sleeping animal, stuck his sharp claws in his back, and rose again in the air, and started to fly away with him to a hill top, where he intended to eat him.

But it was a very little time before the eagle found out

Page 22

that he had made a great mistake. Instead of a hare, that could do nothing but cry for mercy, he had caught a cat, with sharp teeth, and with claws as keen as his own.

The cat was very much surprised, when it first woke up, to find itself pinched so in the back, and flying through the air and over the tree tops so very rapidly. But it soon found out what was the matter, and so it laid hold of the eagle with might and main.

The eagle was now the one to be surprised; and he begged the cat's pardon, and said if the cat would let him go, he would let the cat go. But the cat would not agree to that; for he was not willing to fall from a such a height. So he made the eagle fly back, and put him down safely on the same bank where he had found him; and the eagle was glad enough to get rid of the cat on these terms.

Sometimes, persons who attempt to injure others, find themselves as much mistaken as the eagle was, when he flew upon the cat.

The Way to be Happy.

How pleasant it is, at the end of the day,

No follies to have to repent;

But reflect on the past, and be able to say,

That my time has been properly spent.

When I've done all my business with patience and care,

And been good, and obliging, and kind,

I lie on my pillow, and sleep away there,

With a happy and peaceable mind.

But instead of all this, if it must be confessed,

That I, careless and idle, have been;

I lie down as usual, and go to my rest,

But feel discontented within.

Then, as I don't like all the trouble I've had,

In future, I'll try to prevent it;

For I never am naughty without being sad,

Or good without being contented.

Page 23

The Birth of Jesus.

And there were in the same country, shepherds abiding in the field, keeping watch over their flock by night.

And, lo, the angel of the Lord came upon them, and the glory of the Lord shone round about them; and they were sore afraid.

And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people.

For unto you is born this day, in the city of David, a Saviour, which is Christ the Lord.

And this shall be a sign unto you: Ye shall find the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes, lying in a manger.

And suddenly there was with the angel, a multitude of the heavenly host, praising God, and saying,

Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will towards men.

And it came to pass, as the angels were gone away from them into heaven, the shepherds said one to another, Let us now go even unto Bethlehem, and see this thing which is come to pass, which the Lord hath made known unto us.

And they came with haste, and found Mary and Joseph, and the babe lying in a manger.

And when they had seen it, they made known abroad the saying which was told them concerning this child.

Filial Love Rewarded.

Frederick the Great, King of Prussia, rung his bell one day, but nobody answered. He looked into the room where the youth whom he had for a page, was usually in waiting, and found him fast asleep on a sofa.

The King was going to awake him, when he perceived the end of a letter projecting from his pocket. Being curious to know its contents, he took the letter and read it. It was a letter from his mother, thanking him for sending her so large a part of his wages, to assist her in her distress; and it concluded by praying God to bless him, for his filial attention to her wants.

The King was much pleased with the letter, and was glad

Page 24

to find that his page was so affectionate and dutiful a son. He returned softly to his room and got a purse of money, and then came back, and slipped both the purse and the letter, into the page's pocket. He then returned to his own room again, and rang the bell so violently that the page awoke, and came to him.

"You have slept well!" said the King. The page was very much confused, and made an apology; but, in his embarrassment, he happened to put his hand into his pocket, and thus discovered the purse of money. He drew it out, turned pale, and, looking at the King, he burst into tears, without being able to speak a word.

"What is the matter?" asked the King. "What ails you?" "Ah sire," said the a youth, throwing himself at his feet, "somebody wishes to ruin me! I do not know how this money came into my pocket."

The King kindly told him to give himself no uneasiness, but to send the money to his mother. He also said, "Tell her I am glad the has so dutiful a son; and assure her, in my name, that I will take care both of her and you."

Early Piety.

Happy the child, whose tender years,

Receive instruction well;

Who hates the sinner's path and fears,

The road that leads to hell.

When we devote our youth to God,

'Tis pleasing in His eyes;

A flower, when offered in the bud,

Is no vain sacrifice.

'Tis easier work, if we begin

To fear the Lord betimes;

While sinners, that grow old in sin,

Are hardened in their crimes.

'Twill save us from a thousand snares,

To mind religion young;

Grace will improve our following years,

And make our virtue strong.

Page 25

To Thee, Almighty God, to Thee,

Our childhood we resign!

'Twill please us to look back and see,

That our whole lives were thine!

Let the sweet work if prayer and praise,

Employ my youthful breath;

Thus I'm prepared for length of days,

Or fit for early death.

Musical Mice

Mice are sometimes very fond of music, and it has a wonderful effect upon them. It takes away all their fear of people, and sometimes makes them play very curious antics.

A gentleman of Norfolk City, in Virginia, was once sitting alone in his chamber, playing his flute. In a few minutes, he saw a little mouse creep out of his hole, and advance towards the chair in which he was sitting. Whenever the gentleman stopped playing, the mouse would run into his hole; but it would come back, when he heard the flute again.

The actions of the mouse, while listening to the music, were very amusing. It would shut in eyes, crouch on the floor, and seem to be in an ecstasy of delight. At last it went away, and the gentleman never saw it again.

There was once a mouse of this sort, on board an English ship. One of the officers was playing a plaintive air on the violin, when the mouse ran out into the middle of the floor, and began to cut the most violent capers. It leaped about as if it were frantic with joy; and it became more and more violent every moment, until it finally fell down, and died from the excitement.

A gentleman, of Virginia, was one day amusing himself by playing some airs upon the piano, when a little mouse came out to listen. It was so much pleased, that it approached nearer; and finally it climbed up on the gentleman's shoulder, and then out on his arm, where it sat still, and allowed him to take it in his hand, and put it in his pocket.

There are many other animals that are much affected by music. Snakes have been charmed by it; and a negro man once kept a pack of wolves from eating him up, by playing the fiddle to them.

Page 26

Employment.

Who'll come and play with me under the tree?

My sisters have left me alone;

My sweet little sparrow, come hither to me,

And play with me while they are gone.

O no, little Anna, I can't come indeed,

I've no time to idle away.

I've got all my dear children to feed,

And my nest to new cover with hay.

Pretty bee, do not buzz about over the flower,

But come here and play with me now;

The sparrow won't come and stay with me an hour,

But say, pretty bee--wilt not thou?

O no, little Anna, for dost thou not see,

Those must work who would prosper and thrive?

If I play, they will call me a sad idle bee,

And perhaps turn me out of the hive.

Stop! Stop! little ant, do not run off so fast,

Wait with me a little, and play:

I hope I shall find a companion at last;

Thou art not so busy as they.

O no, little Anna, I can't stay with thee;

We're not made to play, but to labor.

There is always something or other for me

To do for myself, or a neighbor.

What, then, have they all some employment but me,

Who lay lounging here like a dunce?

O then, like the ant, and the sparrow, and bee,

I'll go to my lesson at once.

Monkeys and their Tricks.

Monkeys are very cunning and mischievous little animals that are found in warm countries. They have a face some

Page 27

thing like a man's, and they can use their fore-feet for hands. They have long tails, with which they swing to trees, and they are remarkably active.

Monkeys are great rogues. The wild monkeys frequently plunder the gardens of persons, who live near the forests which they infest. When they go on these stealing expeditions, they place some of their number to act as sentinels, so that it is very hard creep upon them.

Monkeys are easily tamed, and afford a great deal of amusement by their cunning tricks; but they have to be watched very closely for they are always in some mischief. They will catch the cat and use her claws to pull chestnuts out of the fire. They will snatch things out of the pot if the cook turns her back, and they are constantly trying to imitate every thing they see others do.

There was once on board a ship, an African monkey named Jack, that gave great amusement to the passengers and sailors. The first thing he would do in the morning, was to upset the parrot's cage, and make the lump of sugar roll out, when he would instantly catch it up and eat it.

He would snatch the caps off the sailor's heads, and if they were not very quick, would throw them overboard. When the cook was preparing breakfast, he would sit near the grate, and watch his chance to steal something. He sometimes burnt his fingers by these rogueries, but it did not cure him of them.

The captain would sometimes turn the ship's pigs on deck, that they might run about for exercise. This was always a grand time for Jack. He would spring upon the pigs' backs, and ride them all over the ship. The pigs would be very much frightened, and run with all their might. Sometimes they would upset Jack, and then the sailors would laugh at him, which he did not like.

There was a little black monkey on board the same ship. Jack caught him one day, and painted him. He held him by the back of the neck with one hand, and with the other, he took the painter's brush, and covered him all over with white paint. Jack was so afraid that the captain would whip him for this, that he scampered up to the maintop, and staid there three days before he would come down. A lady, however, who was on board, persuaded the captain to pardon him; and so Jack escaped the punishment which he knew he deserved.

Page 28

The Lion and the Mouse.--A Fable.

A lion lay sleeping in the forest one day, when some mice began to amuse themselves by running over him. He suddenly roused, and catching at a mouse that did not got away as quickly as the others, he seized him in his paw, and was about to kill him.

The poor mouse was terribly alarmed, and begged hard for his life. The lion looked at the little trembler, and like a noble animal, thought it would be a discreditable thing for one so big as he, to hurt one so small as the mouse. So he generously forgave the mouse for his mischief, and told him to go free. The mouse lost no time, but scampered away as fast as he could.

It happened a few days afterwards, that the lion was hunting in the same woods. While he was not watching his steps very closely, he got entangled in a net, which a cunning hunter had set for him. He was now as much frightened as the little mouse had been, and he roared with terror.

The mouse heard him, and knew by his voice, that it was the same lion which had given him his life. He immediately hurried to the lion's assistance, as fast as his little legs could carry him. When he saw what was the matter, he told the lion not to be uneasy, for he would soon set him free.

So the mouse went to work with his sharp little teeth, and soon gnawed the cords in two, in so many places, that the lion got out without any difficulty. The lion was very much surprised and pleased, when he found that the helpless little mouse had been able to render him such great service.

This fable teaches us to be kind to the weak and helpless; and to remember that there is no person so much below us, that he may not be able to render a good service in time of need.

To the Lady-Bird.

Lady-Bird, Lady-Bird, fly away home!

The field-mouse has gone to her nest;

The daisies have shut up their sleepy red eyes,

And the bees and the birds are at rest,

Page 29

Lady-Bird, Lady-Bird, fly away home!

The glowworm is lighting her lamp;

The dew is falling fast, and your fine speckled wings

Will flag with the cumbering damp.

Lady-Bird, Lady-Bird, fly away home!

Good luck if you reach it at last;

The owl is abroad, and the bat's on the roam,

Sharp set from their tedious fast.

Lady-Bird, Lady Bird, fly away home!

And if not gobbled up on the way,

You should reach your snug nest in the old willow-tree,

You are lucky,--and I have no more to say.

The Faithful Dog.

A gentleman, accompanied by his dog, was travelling in the West of England, when night overtook him. Not being acquainted with the road, he soon lost his way, and fell into a coal-pit thirty feet deep.

All night, the dog ran round and round the mouth of the pit, barking and howling, as if he was trying to call somebody there to extricate his master. But nobody came.

The next morning, he went back to the house where his master had last staid. When he got there, he did every thing he could, to attract the attention of the servants. He would look at them and whine, and would throw himself on his back before them, as if he was begging them to do something.

The servants offered him food, but be would not eat it. He did nothing but howl, and run backwards and forwards about the door, and give other signs of being in great distress about something. But the servants could not understand him.

At last, the lady of the house, thinking that something must be the matter, told one of the servants to follow him wherever he might go. The dog was now delighted, and rapidly led the way to the pit into which his master had fallen. The gentleman had given himself up for lost, and expected nothing but to starve to death; but the servant went back for help, and soon returned and rescued him from his terrible situation.

Page 30

Old Cato.

Do you think our poor dog, to the stable we'll send,

Because he's grown feeble and old?

No, no, every night, quite secure from alarm,

Old Cato must sleep in the kitchen so warm;

He shan't be turn'd out in the cold.

I remember the time when so frisky and gay,

He would bark at each one that he met;

And watch round the house while asleep we all lay,

If a base lurking robber came prowling that way:

These things I can never forget.

And when Tom, the shepherd, would drive out the sheep,

He'd watch by the side of the fold;

No, no, my poor Cato, secure from all harm,

Shall eat and shall drink in the kitchen so warm;

He shan't be turn'd out in the cold.

The Indian and His Dog.

A family by the name of Lefevre, lived near the Blue Ridge mountains, many years ago. An Indian, named Tewenissa, frequently called to spend the night, when his journeyings led him past the house of Lefevre. He was always cordially welcomed, and kindly entertained.

One day, when Tewenissa, laden with furs, stopped at the house of his friend, he found no one at home, but an old Negro woman. "Where is my brother?" asked the Indian. "Ah sir," said the woman, "his little boy Derick, only four years old, the same that you loved to take upon your knee, wandered away into the forest on yesterday, and is lost; and all the neighbors are helping the distressed parents to look for him."

Tewenissa was grieved when he learned of the sorrow of his friend's family, and the misfortune to his favorite. He sounded the horn, and called in the hunting party; and Then he told Mr. Lefevre that he would find his little boy.

Tewenissa then asked for the shoes and stockings that little

Page 31

Derick had last worn. He next called his faithful dog Oniah, and made him smell them. Taking the house for a centre, he then commenced drawing a circle around it with his stick, making Oniah smell the earth as he went

The circle was not completed before the sagacious dog began to bark. He had discovered the scent, and he commenced to follow the little boy's track, barking as he went. The Indian followed as fast as he could, and so did little Derick's parents, and the rest of the party; but the dog ran so fast that he was soon out of sight.

Half an hour afterwards, they heard Oniah bark again, and soon they saw him returning. He was frisky with joy; so that the Indian knew at once, that he had found the little boy, but whether he was dead or alive could not yet be known. The dog now led the way with Tewenissa following close at his heels, until they came to little Derick lying at the foot of a large tree.

The little boy was alive, but extremely weak and exhausted, so that he could not have lived much longer. Tewenissa took him up in his arms, and carried him to his parents, who were almost overcome with joy. By proper treatment, little Derick was soon as well as ever.

The gratitude of the parents, to the Indian and to his dog, was so great that for a long time they could do nothing but weep, and Tewenissa was almost as much pleased as they were. And the neighbors, when they separated, went to their homes highly delighted with the good Indian, and his wonderful dog.

Kind Words.

A little word in kindness spoken,

A motion or a tear,

Has often healed the heart that's broken,

And made a friend sincere.

A word, a look, has crushed to earth,

Full many a budding flower,

Which, had a smile but owned its birth,

Would bless life's darkest hour.

Page 32

Then deem it not an idle thing,

A pleasant word to speak;

The face you wear, the thoughts you bring,

A heart may heal or break.

The Good-Natured Dog.

Some dogs are very fond of playing with little boys, and will take as much pleasure in the game, as any of them. They will run after a ball and bring it back to the one who threw it, and do many other amusing things.

There was a large dog, named Bernard, that belonged to the teacher of a large school of boys in Virginia. Bernard seemed to know as well as any one, when the time approached for play; and when the boys came running out into the yard, he would meet them, ready to take his share in their amusements.

His favorite sport was to take a stick in his mouth and walk towards them, nodding his head at them, as if he was challenging them to catch him and take the stick away. A troop of boys would immediately pursue him, and the game would begin. Bernard would run just fast enough to keep them from catching him. The boys would sometimes surround him, and think they were sure of him; but just as they would grab at him, he would jump between two of them, or dart between their legs, and away he would go. Sometimes they would get near enough to catch at his bushy tail; but he would make a sudden leap and elude them again.

At last, after the chase had been kept up till they were all tired, Bernard would let them have the pleasure of catching him, and taking his stick away; and then they would jump on his back, or do any thing with him that they wished, and he would never hurt them or get angry. Indeed, the boys all considered him one of the best playmates they had.

The Lark and her Young Ones.--A Fable.

A lark having made her nest in a wheat-field, the wheat became ripe before the young larks were able to fly. Being

Page 33

afraid that the farmer would cut down his wheat before she had provided another place for her little ones, she directed them, while she was gone to get food for them, to listen to what they might hear the farmer say about beginning his harvest.

The old lark then went out; but; but when she came home again, the little birds ran to her and said, "Oh, mother, take us away from here just as soon as you can; for while you were gone we heard the farmer tell his sons that the wheat was ripe, and that they must go and ask some of his neighbors to come early to-morrow morning and help him to cut it down."

"If that is what he said, you need not be afraid, my children," said the old lark. "If the farmer depends upon his neighbors to do his work for him, he will find himself mistaken, and we shall be very safe where we are. So lie down in your nest, and give yourselves no uneasiness."

The next day, when the old lark was going out, she gave her young ones the same directions. In the evening, when she returned, the little larks told her the neighbors had not come to cut down the wheat; but they begged her to move them immediately; for they said that the farmer had told his sons to go and request his friends and relations to come early the next morning, and assist him.

"We are in no danger yet, my children," said the old lark; "for as long as he looks to his friends and relations, to do for him what he ought to do for himself, his wheat will go unharvested. So we will make ourselves quiet, and stay in our nest, for we have no cause for anxiety at present."

The next day the mother-lark again told her young ones to listen to what the farmer might say, and tell her when she came back. In the evenings, when she came home, the little larks told her that the farmer had been there with his sons, but that his friends and relations did not come to assist him. The farmer then told his sons to grind their scythes, and get ready, and that early to-morrow morning, they would begin and harvest the wheat themselves.

"We must now prepare to leave immediately," said the old lark; "for when a man resolves to do his work himself, and to depend upon nobody else, the work is pretty sure to be done; but as long as he depends on friends or neighbors, he is almost sure to effect nothing." So the old lark moved the little birds

Page 34

that same evening, into another field; and sure enough, the next morning the farmer and his sons came, and cut down the wheat.

This fable teaches us to do our work ourselves, and not rely on others to do it for us[.] If we trust to others, they will often disappoint us; and it will also produce habits of laziness and dependence, which will prevent us from ever being prosperous or useful.

The Ant Hill.

Take care, little Richard! don't hurry so fast

Look well to your footsteps, my boy--

If on that ant hill you carelessly tread,

You will many hours' labor destroy.

For these poor little ants have been working all day

To build up that minikin pile;

One grain at a time they have lifted it out,

And been patient as lambs all the while.

They have scoop'd out a little snug hole in the earth,

Their winter's provisions to hold;

And to serve for a bedroom, when summer in past,

Secure from the rain and the cold.

How cruel 'twould be to kick over a house

Which has cost so much toil to prepare!

Step aside, little Richard, and learn to be wise,

From the busy ant's provident care.

If with diligence now, you will study your book,

And be careful each moment to save;

Should you live, my dear child, to the winter of age,

What a fine stock of knowledge you'll have!

But let this one truth sink deep in your heart,

And keep it forever in mind;

That your learning will be to no purpose, unless

You are humble, and modest, and kind.

Page 35

For learning alone will not make you belov'd,

If you're cruel or selfish, or vain;

But a sweet, lowly temper will win every heart,

And the blessing of Heaven obtain.

The Ferocious Dog.

Some dogs are so vicious that it is not safe to let them run at large. They are kept chained in the day time, and only turned loose at night for the purpose of guarding their owners' houses and other property, from thieves and robbers. Sometimes they get loose during the day, and do much mischief.

A drayman's horse once escaped from him in a certain city, and commenced to gallop up the street. The drayman man started after him, and called to the people whom he saw, to stop the horse, and help him to catch him again.

A number of persons ran out into the street to head the horse, and with them there went a bull-dog, which is one of the fiercest kinds of dogs. The bull-dog instantly sprang at the horse, and seized him by the upper lip.

This frightened the horse so much, and gave him so much pain, that he became frantic. So he ran along several streets with all his might, the bull-dog hanging to his lip all the time. At length a crowd got in front of the horse, and stopped him; but he was so wild with pain and fear, that he ran through a hardware store, and into a parlor where the family were at tea.

The family were not expecting such a visitor as that. They had not invited a horse to take supper with them, with a bulldog hanging to his lip. But they had not much time to ask questions; for the horse upset their table, and broke their china, and spoiled their supper, before they knew what was the matter.

A number of men now seized the horse, and held him, while others tried to beat off the savage dog. But all their efforts were in vain; for the bull-dog hung on to the horse's lip, with merciless and unyeilding grip. At last one of the company had to take a knife and cut the dog's throat, in order to relieve the horse. It might perhaps have been done by taking a stick, and prizing open the dog's mouth.

Page 36

If ever you see a horse frantic with fright, you must be very watchful, or he may run over you; for horses in that state, will dash into a house or against a tree, or butt their brains out against a wall, without seeming to know or care what they are doing.

God Seen in All Things.

Thou art, O God! the life and light,

Of all this wondrous world we see;

Its glow by day, its smile by night,

Are but reflections caught from thee.

Where'er we turn, thy glories shine,

And all things fair and bright are thine.

When day, with farewell beam, delays,

Among the golden clouds of even,

And we can almost think we gaze,

Through opening vistas, into heaven;

Those hues, that make the sun's decline

So soft, so radiant, Lord! are thine.

When night, with wings of stormy gloom,

O'ershadows all the earth and skies,

Like some dark beauteous bird, whose plume

Is sparkling with unnumbered dyes;

That sacred gloom, those fires divine,

So grand, so countless, Lord! are thine.

When youthful Spring around us breathes,

Thy spirit warms her fragrant sigh;

And every flower that Summer wreathes,

Is born beneath thy kindling eye.

Where'er we turn, thy glories shine,

And all things fair and bright, are thine.

Show and Use-- The Two Colts.

A nobleman once had a beautiful blooded colt, and also a mule-colt. He gave the young horse to his neighbor, Mr.

Page 37

Scamper, while the little mule went to a very poor man, who made his living by cutting wood.

Mr. Scamper was greatly delighted with his fine colt; and Indeed, as he grew up, he became still handsomer. His color was bright bay, with a white star in his forehead, and his hair was fine and smooth, and as glossy as silk.

Mr. Scamper was to train him up for a race-horse; For he was too fine a horse to be put to any useful purpose. So he was kept in a warm stable, and fed with the best of corn and hay, and was duly curried and rubbed, and regularly exercised. Indeed, Mr. Scamper treated him with as much care and tenderness, as he did his own children.

When this fine horse was three years old, Mr. Scamper sent him away to be trained for the race-course. The expense of this, was greater than Mr. Scamper could afford; so he had to take his children from the good school to which they were going, and send them to an inferior because it was cheaper.

The next year the young racer was placed upon the turf. He was beaten the first race; but he came out second. In the next race, he was successful; and Mr. Scamper was almost crazy with joy. Mr. Scamper now gave his whole attention to racing; and at last he became so excited, that he made up a race in which he bet all he was worth on his horse. The race was lost, and Mr. Scamper was broken up and ruined[.]

The little mule, meanwhile, had grown up also, but through a great deal of hardship. He had to live on what he could find in the lanes and among the bushes; and in winter, he had no stable to shelter in. As soon as he was big enough to ride, two or three of the children would mount him at a time, and beat him along with sticks. But he grew up healthy and strong.

His owner then set him to hauling wood to market, and in this way the mule was very profitable to him. He soon made enough money, to buy a plenty of food for his mule, which thus became fat and greatly improved. After awhile, he was able, out of the earnings of his mule, to buy a horse and cow; and he soon became quite a farmer, and grew rich. So that while Mr. Scamper's present ruined him, because his horse was thought too fine for service, the mule made the wood-cutter's fortune, because he put him to a good use.

Page 38

How to Tell Bad News.

Mr. H.--Ha! Steward, how are you, my old boy? How do things go on at home?

Steward--Bad enough, your honor. The magpie's dead.

Mr. H.--Poor Mag! so he's gone. How came he to die?

Stew.--Over-ate himself, sir.

Mr. H.--Did he, indeed? a greedy villain! Why, what did he get that he liked so well?

Stew.--Horse-flesh, sir; he died of eating horse-flesh.

Mr. H.--How came he to get so much horse-flesh?

Stew.--your father's horses, sir.

Mr. H.--What! are they dead, too?

Stew.--Ay, sir; they died of over-work.

Mr. H.--And why were they over-worked, pray?

Stew.--To carry water, sir.

Mr. H.--To carry water! and what were they carrying water for?

Stew.--Sure, sir, to put out the fire.

Mr. H.--Fire! what fire?

Stew.--O, sir, your father's house is burned down to the ground.

Mr. H.--My father's house burned down! and how came it set on fire?

Stew.--I think, sir, it must have been the torches.

Mr. H.--Torches! what torches?

Stew.--At your mother's funeral.

Mr. H.--Alas! has my mother died?

Stew.--Ah, poor Lady, she never looked up after it.

Mr. H.--After what?

Stew.--The loss of your father.

Mr. H.--My father gone, too?

Stew.--Yes, poor gentleman, he took to his bed as soon as he heard of it.

Mr. H.--Heard of what?

Stew.--The bad news, sir, and please your honor.

Mr. H.--What! more miseries? more bad news? No! you can add nothing more!

Stew.--Yes, sir; your bank has failed, and your credit is lost, and you are not worth a shilling in the world. I made bold, sir, to come to wait on you about it, for I thought you would like to hear the news.

Page 39

Contented John.

There was honest John Tompkins, a hedger and ditcher,

Although he was poor, he did not sigh to be richer;

For all such vain wishes, to him were prevented,

By a fortunate habit of being contented.

If cold was the weather, or dear was the food,

John never was found in a murmuring mood;

For this, he was constantly heard to declare,--

What he could not prevent, he could cheerfully bear.

For why should I grumble and murmur, he said;

If I cannot get meat, I can surely get bread,

And though fretting may make my calamities deeper,

It can never cause bread and cheese to be cheaper.

If John was afflicted with sickness or pain,

He wished himself better, but did not complain,

Never lie down to fret, in despondence and sorrow,

But said--that he hoped he would be better to-morrow.

If any one wronged him, or treated him ill,

Why, John was good-natured and sociable still;

For he said, that revenging the injury done,

Would be making two bad men, where there need be but one.

And thus honest John, though his station was humble,

Passed through this sad world, without even a grumble;

And I wish that some folks, who art greater and richer,

Would copy John Tompkins, the hedger and ditcher.

The Earth and Its Inhabitants.

It was four thousand and four years before the coming of Christ, or nearly six thousand years ago, when this earth was first inhabited by men.

There are now five varieties or races of men found on the earth. They are distinguished from each other partly by their different colors. There are the White race, the Yellow race, the Red race, the Brown race, and the Black race.

Page 40

The White people live chiefly in Europe, and they came thence to America. The Yellow and the Brown people, live chiefly in Asia, and the great Islands near Asia. The Black people live in Africa, or came from there. The Red people, called Indians, live in America.

America was not known to White people, until nearly four hundred years ago. A brave man, named Christopher Columbus, was the first to discover it. After sailing, for many months and days, across the dark waters of the ocean, where nobody had ventured before, he came in sight of America on the 11th October, in the year 1492.

When America was discovered, it was grown up in forests. There were no cities, or towns, or houses, such as we have now; and no farms and meadows, and no ships and steamboats on the rivers. The woods were filled with all sorts of wild animals, and the Indians lived chiefly by hunting them with their bows and arrows.

When the White men first came here, the Indians thought that they and their ships, had dropped down from the sky. The supposed that they were superior beings, and were very much afraid of them, and treated them generally with great kindness.

It was not long, however, before the White people began to oppress them; and then there arose war and fighting, in which the Indians behaved very cruelly, but were always vanquished, and a great many of them were destroyed; so that there are very few Indians now, compared with the number that were here when Columbus discovered America.

Gratitude.

Whene'er I take my walks abroad,

How many poor I see!

What shall I render to my God,

For all his gifts to me?

Not more than others I deserve,

Yet God has given me more;

For I have food while others starve,

Or beg from door to door.

Page 41

How many children, on the street,

Half naked I behold;

While I am clothed from head to feet,

And sheltered from the cold.

While some poor creatures scarce can tell,

Where they may lay their head,

I have a home wherein to dwell,

And rest upon my bed.

While others early learn to swear,

And curse, and lie, and steal,

Lord! I am taught thy name to fear,

And do thy holy will.

Are these thy favors, day by day,

To me above the rest?

Then let me love thee more than they,

And try to serve thee best!

Heaven.

The rose is sweet, but it is surrounded with thorns; the spring is pleasant, but it is soon past; the rainbow is glorious, but it vanisheth away; life is good, but it is quickly swallowed up in death.

There is a place of rest for the righteous; in that land there is light without any cloud, and flowers that never fade. Myriads of happy souls are there, singing praises to God.

That country is Heaven: it is the country of those that are good; and nothing that is wicked must inhabit there. This earth is pleasant, for it is God's earth, and it is filled with delightful things.

But that country is better: there we shall not grieve any more, nor be sick any more, nor do wrong any more. In that country there are no quarrels; all love one another with dear love.

When our friends die, and are laid in the cold ground, we see them here no more; but there we shall embrace them, and never be parted from them again. There we shall see all the good men whom we read of.

Page 42

There we shall see Jesus, who is gone before us to that happy Place; there we shall behold the glory of the high God.

The Christian Race.

Awake, my soul! stretch every nerve,

And press with vigor on!

A heavenly race demands thy zeal,

And an immortal crown.

A cloud of witnesses around,

Hold thee in full survey.

Forget the steps already trod,

And onward urge thy way.

'Tis God's all-animating voice,

That calls thee from on high,

'Tis his own hand presents the prize,

To thine aspiring eye:

My soul! with sacred ardour fired,

The glorious prize pursue;

And meet with joy, the high command,

To bid the earth adieu.

The Seasons.

Who is this beautiful maiden that approaches, clothed in a robe of green light? She has a garland of flowers on her head, and flowers spring up wherever she sets her foot. The snow which covered the fields, and the ice which was on the rivers, melt away when she breathes upon them.

The young lambs frisk about her, and the birds warble to welcome her coming. When they see her, they begin to choose their mates, and to build their nests. Youths and maidens, have ye seen this beautiful virgin? If ye have, tell me who she is, and what is her name.

Who is this that cometh from the south, thinly clad in a light, transparent garment? Her breath is hot and sultry. She seeks the clear streams, the crystal brooks, to bathe her

Page 43

languid limbs. The brooks and rivulets fly from her, and are dried up at her approach. She cools her parched lips with berries, and the grateful acids of fruits. The tanned haymakers welcome her coming; and the sheep-shearer, who clips the fleeces off his flock with his sounding shears.

When she cometh, let me lie under the thick shade of a spreading beech-tree,--let me walk with her in the early morning, when the dew is yet upon the grass,--let me wander with her in the soft twilight, when the shepherd shuts his fold, and the star of the evening appears. Who is she that cometh from the south? Youth and maidens, tell me, if ye know, who she is, and what is her name.

Who is he that cometh with sober pace, stealing upon us unawares? His garments are red with the blood of the grape, and his temples are bound with a sheaf of ripe wheat. His hair is thin, and begins to fall, and the auburn is mixed with mourning gray. He shakes the brown nuts from the tree. He winds the horn, and calls the hunters to their sport. The gun sounds. The trembling partridge and the beautiful pheasant flutter bleeding in the air, and fall dead at the sportsman's feet. Youth and maidens, tell me, if ye know, who he is, and what is his name.

Who is he that cometh from the north, in furs and warm wool? He wraps his cloak close about him. His head is bald; his beard is made of sharp icicles. He loves the blazing fire high piled upon the hearth, and the wine sparkling in the glass. He binds skates to his feet, and skims over the frozen lakes. His breath is piercing and cold, and no little flower dares to peep above the surface of the ground when he is by. whatever he touches, turns to ice. Youth and maidens, do you see him? He is coming upon us, and soon will be here. tell me, if ye know, who he is, and what is his name.

The Creator Greater than His Works.

Come, and I will show you what is beautiful. It is a rose fully blown. See how she sits upon her mossy stem, like the queen of all the flowers! Her leaves glow like fire; the air is filled with her sweet odor; she is the delight of every eye.

She is beautiful, but there is a fairer than she. He that

Page 44

made the rose, is more beautiful than the rose: He is all lovely: He is the delight of every heart.

I will show you what is strong. The lion is strong. When he raiseth himself from his lair, when he shaketh his mane, when the voice of hiss roaring is heard, the cattle of the field fly, and the wild beasts of the desert hide themselves, for he is very terrible.

The lion is strong, but He that made the lion is stronger than he. His anger is terrible: He could make us die in a moment, and no one could save us from His hand.

I will show you what is glorious. The sun is glorious. When he shineth in the clear sky, and is seen all over the earth, he is the most glorious object the eye can behold.

The sun is glorious, but He that made the sun is more glorious than he. The eye beholdeth Him not, for His brightness is more dazzling than we could bear. He seeth in all dark places, by night as well as by day, and the light of His countenance is over all His works.

Who is this great name, and what is he called, that my lips may praise him?

This great name is God. He made all things, but He is himself more excellent than they. They are beautiful, but He is beauty; they are strong, but He is strength, they are perfect, but He is perfection.

The Old Horse.

No, children, he shall not be sold;

Go lead him home, and dry your tears.

'Tis true, he's blind, and lame, and old,

But he has served us twenty years.

Well, has he served us,--gentle, strong,

And willing, through life's varied stage;

And having toiled for us so long,

We will protect him in his age.

Our debt of gratitude to pay,

His faithful merits to requite,

His play-ground be the field by day,

A shed shall shelter him at night.

Page 45

A life of labor was his lot;

He always tried to do his best.

Poor fellow, now we'll grudge thee not,

A little liberty and rest.

Go, then, old friend; thy future fate,

To range the fields from harness free;

And just below the cottage gate,

I'll go and build a shed for thee.

The Ten Commandments.

And God spake all these words, saying:

I. Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

II. Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or the likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the waters under the earth:

Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them: for I the Lord thy God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children, unto the third and fourth generations of them that hate me;

And showing mercy unto thousands of them that love me and keep my commandments.

III. Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain; for the Lord will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain.

IV. Remember the Sabbath-day to keep it holy.

Six days shalt thou labor and do all thy work:

But the seventh is the Sabbath of the Lord thy God: in it thou shalt not do any work, thou nor thy son nor thy daughter, thy manservant, nor thy maid-servant, nor thy cattle, nor the stranger that is within thy gates.

For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested the seventh day: wherefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath-day and hallowed it.

V. Honor thy father and mother; that thy days may be long upon the had which the Lord thy God giveth thee.

VI. Thou shalt not kill.

VII. Thou shalt not commit adultery.

VIII. Thou shalt not steal[]

IX. Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.

Page 46