The History and Debates of the Convention of the People of Alabama,

Begun and held in the City of Montgomery, on the Seventh Day of January, 1861

in which is Preserved the Speeches of the Secret Sessions,

and Many Valuable State Papers:

Electronic Edition.

Smith, William Russell, 1815-1896.

Funding from the Institute of Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Bryan Sinche

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services and Jill Kuhn Sexton

First edition, 2000

ca. 1.25MB

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) The History and the Debates of the Convention of the People of Alabama, Begun and Held in the City of Montgomery, on the Seventh Day of January, 1861; In Which is Preserved the Speeches of the Secret Sessions, and Many Valuable State Papers.

William R. Smith

v, [1], xii, 9-464 p.

Montgomery; Tuscaloosa; Atlanta

White Pfister & Co.; D. Woodruff; Wood, Hanleiter, Rice & Co.

1861.

Call number 2845 Conf. (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Convention of the people of the state of Alabama (1861 : Montgomery)

- Secession -- Alabama.

- Secession -- Southern States.

- Alabama -- Politics and government -- 1861-1865.

- Alabama -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865.

Revision History:

- 2001-02-19,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-10-18,

Jill Kuhn Sexton

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-09-15,

Bryan Sinche and Joby Topper

finished scanning images.

- 2000-07-24,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing and TEI/SGML encoding.

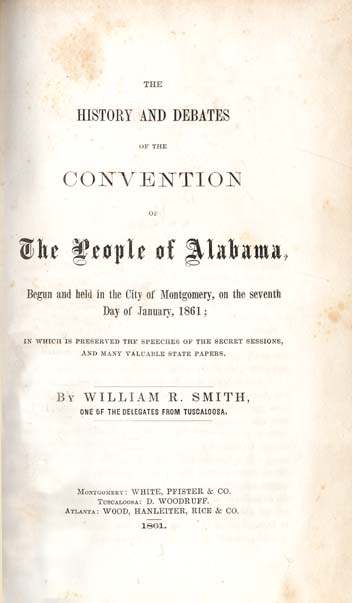

THE

HISTORY AND DEBATES

OF THE

CONVENTION

OF

The People of Alabama,

Begun and held in the City of Montgomery, on the seventh

Day of January, 1861

IN WHICH IS Preserved the Speeches of the Secret Sessions,

AND MANY VALUABLE STATE PAPERS.

BY

WILLIAM R. SMITH,

ONE OF THE DELEGATES FROM TUSCALOOSA.

MONTGOMERY: WHITE, PFISTER & CO.

TUSCALOOSA: D. WOODRUFF.

ATLANTA: WOOD, HANLEITER, RICE & CO.

1861.

Page verso

Printed for the Author, by

WOOD, HANLEITER, RICE & CO.,

ATLANTA, GA.

Page iii

PREFACE.

I deem myself happy in having attempted to collect the materials for this book. Of the Conventions of the people that have recently been held in the seceding States on the great question of dissolving the Union, there does not seem to have been any serious effort made, in any except Alabama, to preserve the Debates. It is, therefore, my agreeable fortune, not only to be able to set an example of diligence to the sister States, but to combine, in an authentic record for future ages, both the acts of the PATRIOTS of Alabama, and the fervent words by which they were mutually animated in the discharge of their great duties.

The stirring times through which we have just passed, and the startling events which have distinguished the day, were all calculated to excite the intellectual energies to the most vigorous exertion; and whatever of eloquence or wisdom was in the possession of any citizen, may be fairly supposed to have been called into exercise. The destinies of a great Nation and the Liberties of the people were involved in the issues; and while the Past was to be measured by the statesman's Philosophy, it was as well the duty of Wisdom to lift the veil of the uncertain Future. Here was a field for the most sublime labor; and while I will not run the hazard of raising the expectation of the reader, by allowing him to

Page iv

look into this book for those magnificient outbursts of eloquence that dazzle, bewilder and persuade, yet I may safely promise a forensic treat, in a vast variety of speeches which breathe the genuine spirit of wisdom, animated by the liveliest touches of indignant patriotism.

The reader may rely upon the perfect authenticity of the historical parts of the book, and upon the accuracy of the speeches as to the sentiments uttered and the positions assumed by the speakers on the points arising in debate; for almost every speech in the volume, of any considerable length or importance, has been submitted to the inspection or revision of the speaker; and where this has been impracticable, and the notes confused or uncertain, the speeches have been omitted entirely, as, I have been unwilling to assume the responsibility of publishing a sentiment in the name of another, on a great question, where the smallest doubt existed as to its accuracy.

In the speeches reported from my own notes, I have endeavored to adhere as nearly as possible to the language of the speaker; but to preserve the idea and sense has been my paramount design. I have attempted but little ornament either in language or metaphor; so that I have no fears that every debater will recognize his own speech as genuine, both in sentiment and language, although condensed and abridged.

Some portions of this volume will appear almost romantic. The scenes of the Eleventh of January, when the Convention was deliberating on the final passage of the Ordinance of Secession, were extremely touching. The MINORITY rose to the heights of moral sublimity as they surrendered their long cherished opinions for the sake of unity at home. The surrender was graceful and unrestrained: without humiliation on the one hand, or dominant hauteur on the other. The speeches on this occasion were uttered in husky tones, and

Page v

in the midst of emotions that could not be suppressed, and which, indeed, there was no effort to disguise. These and other scenes which appear in the Journal and Debates, will show the impartial enquirer, that every member of the Convention was deeply impressed with his responsibility. Solemnity prevailed in every phase of the proceedings. In the debates of six weeks, on the most exciting topics, but few unkind words were uttered. Forensic invective, so characteristic of legislative assemblies, was lost in devotion to the public good, and scarcely a jar of personal bitterness disturbed the harmony of the deliberations.

While I claim nothing for myself, but due credit for the diligence and labor which I have employed in collecting and combining these materials, yet I feel proud in submitting this Book to the Public, for I am conscious of thus supplying a link in the History of Ages, and a chapter in the LIFE OF LIBERTY.

Page vi

EXPLANATION.

It must be noticed that this book does not pretend to give the entire debates of the Convention. This could hardly be expected in a volume of this size, since a single day's debate, if given in full, would fill fifty--perhaps an hundred pages. My object has been to preserve the political features of the debates; and hence I have not attempted, as a general rule, to give the discussions on the ordinary subjects of legislation. Many of the ablest sppeches delivered in the Convention were upon the changes in the Constitution of the State, not touching the political necessities of the new condition of things. These speeches must be lost, however much they were worthy of preservation.

The Appendix contains the REPORTS of the Commissioners appointed by Governor Moore to the slave-holding States. These Reports are able documents, and will explain themselves. Whatever the object of the appointment of these Commissioners may have been, the documents themselves become historical, and must live in the annals of the Revolution.

Page I

INDEX

- BAKER, of Barbour:

- Returns thanks to the ladies for Flag 120

- BAKER, of Russell:

- BARRY, Hon. Wm. S., President Mississippi Convention:

- Dispatch from 75

- BEARD, Hon. A. C.:

- BECK, Hon. F. K.:

- BRAGG, Hon. Jno.:

- Resolutions in reference to Collector of Mobile 128

- Report on same subject 133

- Speech against excluding members of the Convention from election to Congress 154

Page II - BREWER, S. D., Temporary Secretary 19

- BROOKS, Hon. Wm. M.:

- BULGER, Hon. M. J.:

- BUFORD, Hon. Jeff.:

- Speech on the Legitimate powers of the Convention 281

- BULLOCH, Hon E. C:

- CALHOUN, Hon. J. M.:

- CALHOUN, Hon. A. P.:

- CADETS of University:

- CHILTON, Hon. Wm. P:

- Elected Deputy to Congress 161

- CLARKE, Hon. W. E., of Marengo:

- CLARK, Hon. James S., of Lawrence:

- Speech on Applause in the Galleries 45

- Speech Against Secession 81, 183

- Speech on Ratification of the Constitution 326

Page III - CLOPTON, Hon. David:

- CLEMENS, Hon. Jere:

- Speech on Whatley's Resistance Resolutions 28

- On sending Troops to Florida 50

- Minority Report on Secession 77

- Speech on Secession 116

- Speech against excluding members of the Convention from being elected to Congress 158

- Speech on sending Commissioners to Washington 166

- Speech on Withdrawing Troops from Florida 211-220

- COLEMAN, Hon. A. A.:

- COCHRAN, Hon. John:

- CONVENTION:

- CONFISCATION 174

- COUNTIES:

- Size of, Proposed to be Changed 169

- COOPER, Hon. Wm.:

- CRUMPLER, Hon. Albert:

- Speech on the Ordinance of Secession 103

- CROOK, Hon. Jno. M.:

Page IV - COMAN, Hon. J. P.:

- Speech on Ratification of Constitution 354

- CURRY, Hon. J. L. M.:

- DARGAN, Hon. E. S.:

- DAVIS, Hon. Nich.:

- DEPUTIES elected:

- DOWDELL, Hon. J. F.:

- EARNEST, Hon. Wm. S.:

- EDWARDS, Hon. Wm. M.:

- Speech on Secession 104

Page V - ELMORE, Hon. John A.:

- FOWLER, Wm. A.:

- FLAG of Alabama, presented by Ladies 119

- Sonnet to same 122

- FEARN, Hon. Thos:

- FLORIDA:

- GILMER, Hon. F. M.:

- Commissioner to Virginia 35

- GARRETT, Hon. J. J.:

- Commissioner to North Carolina 35

- GIBBONS, Hon. Lyman:

- GREEN, Hon. Jno.:

- Speech on Secession 98

- GOVERNMENT:

- HALE, Hon. S. F.:

- HENDERSON, of Macon:

- Resolutions to send Commissioners to Arizonia 124

- Ordinance for a Council of State 129

- Speech on Divorce 368

Page VI - HERNDON, Hon. T. H.:

- HORN, A. G.:

- HOPKINS, Hon. A. F.:

- Commissioner to Virginia 35

- HUBBARD, Hon. David:

- HUMPHRIES, Hon. H. G.:

- INZER, Hon. Jno. W.:

- Speech on Secession 97

- INTRODUCTION, Historical 9

- JEMISON, Hon. R., Jr.:

- Voted for, for President of Convention 23

- Resolution to Close Doors 13

- Speech on Coercion Resolution 63

- Speech on Secession 93

- Motion in regard to the Formation of a Permanent Government 136

- Resolution to Submit same to a Convention of the People 147

- Speech on Election of Deputies to Congress 150

- On Commissioners to Washington 172

- On Withdrawing Troops from Florida 218, 220

- On the Power of Taxation 298

- Resolution to Refer the Permanent Constitution for Ratification to a Convention 32

- Speech on Ratification of the Constitution 323

- JEWETT, Hon. O. S.:

Page VII - JONES, Hon. H. C., of Lauderdale:

- JOHNSON, Hon. N. D.:

- JUDGE, Hon. T. J.:

- Commissioner to Washington--His Report 152

- KIMBALL, Hon. A.:

- LEWIS, Hon. D. P.:

- MANLY, Rev. Basil: His Prayer 20

- MATTHEWS, Ex-Governor:

- M'CLANAHAN, Hon. Jno. M.:

- Speech on Reducing Size of Counties 272

- M'REA, Gen. Colin:

- Elected Deputy to Southern Congress 161

- MISSISSIPPI River: Navigation of 174

- MORGAN, Hon. Jno. T.:

- Resolution Restraining Applause 23

Page VIII - MORGAN, Hon. Jno. T.:

- Speech on Secret Sessions and Applause 45

- Speech on Coercion Resolution 61

- Speech on excluding Members of the Convention from the Southern Congress 153

- Speech on the African Slave-Trade 195

- Speech on Withdrawing Troops from Florida 215

- Speech on Changing the Size of Counties 277

- Speech on the Power of Taxation 309

- Speech on the Ratification of the Constitution 324

- MOORE, Hon. A. B., Governor:

- PETTUS, Hon. E. W.:

- POSEY, Hon. S. C.:

- POTTER, HON. JOHN:

- PRESIDENT DAVIS:

- PUBLIC LANDS:

- Debate on 311

- PUGH, Hon. J. L.:

- Communication to Convention 125

Page IX - RALLS, Hon. John P.:

- REPORTS:

- SANFORD, Hon. J. W. A.:

- SECESSION:

- SHEFFIELD, Hon. James L.:

- SMITH, Hon. Wm. R., of Tuscaloosa:

- Speech on Resistance Resolution 25

- Speech on Sending Troops to Florida 53

- Speech on Coercion Resolution 66

- Speech on Secession 97

- Speech on Reception of Flag 120

- Sonnet to Flag 121

- Speech on Sending Commissioners to Washington, 167

- Speech on Confiscation 179

- Speech on Navigation of the Mississippi 186-187

- Speech on African Slave Trade 200

- Speech on Watts' Amendment--same subject 259

- Speech on Citizenship 227

- Speech on Ratification of Constitution 341

- SMITH, Hon. R. H.:

- SMITH, Frank L.:

- Elected Assistant Secretary 23

Page X - SHORTER, Hon. John Gill:

- SHORTRIDGE, Hon. Geo. D.:

- STEELE, Hon. John A.:

- Speech on Secession 103

- STONE, Hon. Lewis M.:

- TIMBERLAKE, Hon. John P.:

- WYNN, R. H.:

- Elected Door-Keeper 23

- WATTS, Hon. T. H.:

- Speech on Sending Troops to Florida 52

- Speech on Resolution Against Coercion 68

- Reads Dispatches 124

- Speech on Commissioners to Washington 166-168

- Ordinance to Confiscate Property 175

- Speech on Withdrawing Florida Troops 213-220

- Speech on Citizenship 226

- Speech on African Slave-Trade 258-264

- Speech on Power of Taxation 293-300

- Speech on Public Lands 324

- WATKINS, Hon. R. S.:

- Speech on Secession 101

- WEBB, Hon. James D.:

- Speech on Commissioners to Washington 168

Page XI - WEBB, Hon. James D.:

- WALKER, Hon. R. W.:

- Elected Deputy to Congress 161

- WHATLEY, Hon. G. C.:

- WINSTON, Hon. Wm. O.:

- Speech on Secession 109

- WINSTON, Hon. Jno. A.:

- Commissioner to Louisiana 35

- His Report 413

- Commissioner to Louisiana 35

- WILLIAMSON, Hon. James:

- YANCEY, Hon. Wm. L.:

- Resolution Providing for Opening the Convention by Prayer, 20

- Speech on Resistance Resolution 27

- Resolution Sending Troops to Florida 50

- Speech on Resolution Against Coercion 68

- Report of Ordinance of Secession 76

- Speech on Timberlake's Amendment 91

- Speech on Secession 101

- Deputed by the Ladies to Present a Flag to the Convention. 120

- Report for Provisional and Permanent Government 130

- Speech on the same subject 139

- Speech Against Excluding Members of the Convention from Election as Deputies to Congress 157

- Speech on Resistance Resolution 27

Page XII - Resolution Providing for Opening the Convention by Prayer, 20

- YANCEY, Hon. Wm. L.:

- YEAS AND NAYS:

- On Resolution to submit Ordinance of Secession to the People 55

- On Clemens' Minority Report 80-81

- On Timberlake's Amendment 92

- On the Ordinance of Secession 118

- On Bulger's Motion to Submit to the People the Election of Representatives to Congress 149

- On Jemison's Amendment to Submit the Constitution to a New Convention 363

- On the Ratification of the Constitution 364

- On Clemens' Minority Report 80-81

- On Resolution to submit Ordinance of Secession to the People 55

- YELVERTON, Hon. G. T.:

Page 9

INTRODUCTION--HISTORICAL.

ON the 24th day of February, 1860, the Alabama Legislature adopted the following Joint Resolutions, with great unanimity--there being but two dissenting voices:

WHEREAS, anti-slavery agitation persistently continued in the non-slaveholding States of this Union, for more than a third of a century, marked at every stage of its progress by contempt for the obligations of law and the sanctity of compacts, evincing a deadly hostility to the rights and institutions of the Southern people, and a settled purpose to effect their overthrow even by the subversion of the Constitution, and at the hazard of violence and bloodshed; and whereas, a sectional party calling itself Republican, committed alike by its own acts and antecedents, and the public avowals and secret machinations of its leaders to the execution of these atrocious designs, has acquired the ascendency in nearly every Northern State, and hopes by success in the approaching Presidential election to seize the Government itself; and whereas, to permit such seizure by those whose unmistakable aim is to pervert its whole machinery to the destruction of a portion of its members would be an act of suicidal folly and madness, almost without a parallel in history; and whereas, the General Assembly of Alabama, representing a people loyally devoted to the Union of the Constitution, but scorning the Union which fanaticism would erect upon its ruins, deem it their solemn duty to provide in advance the means by which they may escape such peril and dishonor, and devise new securities for perpetuating the blessings of liberty to themselves and their posterity; therefore,

- Be it resolved, That upon the happening of the contingency contemplated in the foregoing Preamble, namely, the election of

Page 10a President advocating the principles and action of the party in the Northern States calling itself the Republican Party, it shall be the duty of the Governor, and he is hereby required, forthwith to issue his Proclamation, calling upon the qualified voters of this State to assemble on Monday not more than forty days after the date of said Proclamation, at the several places of voting in their respective counties, to elect delegates to a Convention of the State, to consider, determine and do whatever in the opinion of said Convention, the rights, interests, and honor of the State of Alabama requires to be done for their protection.

- Be it further resolved, That said Convention shall assemble at the State Capitol on the second Monday following said election.

- Be it further resolved, That it shall be the duty of the Governor as soon as possible to issue writs of election to the Sheriffs of the several counties, commanding them to hold an election on the said Monday so designated by the Governor, as provided for in these Joint Resolutions, for the choosing of as many delegates from each county to said Convention as the several counties shall be entitled to members in the House of Representatives of the General Assembly; and said election shall be held at the usual places of voting in the respective counties, and the polls shall be opened under the rules and regulations now governing the election of members to the General Assembly of this State, and said election shall be governed in all respects by the laws then in existence, regulating the election of members to the House of Representatives of the General Assembly, and the persons elected thereat as delegates, shall be returned in like manner, and the pay, both mileage and per diem, of the delegates to said Convention, and the several officers thereof, shall be the same as that fixed by law for the members and officers of said House of Representatives.

- Be it further resolved, That copies of the foregoing Preamble and Resolutions be forwarded by the Governor as soon as possible to our Senators and Representatives in Congress, and to each of the Governors of our sister States of the South.

The following Resolutions, adopted at the same session, will serve still further to show the spirit that animated the Legislature of Alabama:

Joint Resolutions of the General Assembly of Alabama in response to the Resolutions of South Carolina.

1st, Be it resolved, That the State of Alabama, fully concuring with the State of South Carolina, in affirming the right of any State

Page 11

to secede from the confederacy, whenever in her own judgment such a step is demanded by the honor, interests and safety of her people, is not unmindful of the fact that the assaults upon the institution of slavery, and upon the rights and equality of the Southern States, unceasingly continued with increasing violence and in new, and more alarming forms, may constrain her to a reluctant but early exercise of that invaluable right.

2d, Be it further resolved, That in the absence of any preparation for a systematic co-operation of the Southern States, in resisting the aggressions of their enemies, Alabama, acting for herself, has solemnly declared that under no circumstances will she submit to the foul domination of a sectional Northern party, has provided for the call of a Convention in the event of the triumph of such a faction in the approaching Presidential election, and to maintain the position thus deliberately assumed, has appropriated the sum of $200,000 for the military contingencies which such a course may involve.

3d, Be it further resolved, That the State of Alabama having endeavored to prepare for the exigencies of the future, has not deemed it necessary to propose a meeting of Deputies from the slave-holding States, but anxiously desiring their coöperation in a struggle which perils all they hold most dear, hereby pledges herself to a cordial participation in any and every effort, which in her judgment will protect the common safety, advance the common interest, and serve the common cause.

4th, Be it further resolved, That should a Convention of Deputies from the slave-holding States assemble at any time before the meeting of the next General Assembly, for the purposes and under the authority indicated by the resolutions of the State of South Carolina, the Governor of this State be, and he is hereby authorized, to appoint one deputy from each Congressional District, and two from the State at large, to represent the State of Alabama in such Convention.

Upon the election of Mr. Lincoln to the Presidency, the Governor, in pursuance of the foregoing Resolutions, called a Convention of the People of Alabama, to meet in the city of Montgomery, on the 7th day of January, 1861. The following CORRESPONDENCE is worthy of preservation as a part of the history of the times:

Page 12

LETTER FROM GOV. MOORE.

Montgomery, Nov. 12, 1860.

To his Excellency A. B. Moore:

Sir--At a meeting of citizens of several counties of the State, held at this place on Saturday, the 10th inst., the undersigned were appointed a Committee to confer with your Excellency, and ascertain the construction put by you on the Joint Resolutions of our last Legislature, for the call of a Convention of the people of the State. What is desired from you are, your views as to the time when you are authorized to issue your Proclamation for the call of that Convention, whether upon the election of Electors by the people of the several States, or when those Electors cast their vote for President; and also, if it be consistent with your ideas of public duty, that you would inform us when that Proclamation will be issued, and upon what day you will order the election of Delegates to that Convention.

These are questions of deep interest to the people of the State, and it is deemed of great moment that your views on those questions should be known, if you have come to a determination about them. Your answer, we hope, will be given at an early day, with permission for its publication.

Very respectfully,

J. A. ELMORE, Montgomery county.

J. D. PHELAN, Montgomery county.

E. W. PETTUS, Dallas county.

N. H. R. DAWSON, Dallas county.

J. B. CLARK, Greene county.

W. E. CLARKE, Marengo county.

D. W. BAINE, Lowndes county.

J. F. CLEMENTS, Lowndes county.

J. G. GILCHRIST, Lowndes county.

C. ROBINSON, Lowndes county.

E. D. KING, Perry county.

R. FRAZIER, Jackson county.

W. L. YANCEY, Montgomery county.

J. H. CLAYTON, Montgomery county.

G. B. DUVAL, Montgomery county.

T. J. JUDGE, Montgomery county.

G. GOLDTHWAITE, Montgomery county.

T. H. WATTS, Montgomery county.

S. F. RICE, Montgomery county.

T. LOMAX, Montgomery county.

M. A. BALDWIN, Montgomery county.

Page 13

Executive Department,

Montgomery, Nov. 14, 1860.

GENTLEMEN: I have received your letter of the 12th inst., asking for my construction of "the Joint Resolutions of our last Legislature, for the call of the Convention of the people of the State." You particularly desire to know when I consider myself authorized to issue my Proclamation for the call of a Convention--"whether upon the election of Electors by the people of the several States, or when said Electors cast their votes for President." You also ask me to inform you, if consistent with my ideas of public duty, "when that Proclamation will be issued, and upon what day you [I] will order the election for the delegates to the Convention."

I fully agree with you, that "these are questions of deep interest to the people of the State," and having, after mature deliberation, determined upon my course in regard to them, and not considering it inconsistent with my public duty to communicate that determination to you, with leave to publish it, I unhesitatingly do so.--The intense interest and feeling which pervade the public mind, make it not only proper, but my duty.

After stating a long list of aggressions in the preamble to the Joint Resolutions referred to, the first resolution provides "that upon the happening of the contingency contemplated in the foregoing preamble, viz: the election of a President advocating the principles and action of the party in the Northern States, calling itself the Republican party, it shall be the duty of the Governor, and he is hereby required forthwith to issue his proclamation," &c.

The Constitution of the United States points out the mode of electing a President, and directs that "each State shall appoint, in such manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a number of electors, equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in Congress." See Art. 2, §1.

Art. 12, §1, of Amendments to the Constitution, provides that the Electors shall meet in their respective States, and vote by ballot for President and Vice President." Under these provisions of the Constitution, the people of the several States vote for electors and these electors vote for President. It is clear to my mind that a candidate for the Presidency cannot constitutionally be elected until a majority of the electors have cast their votes for him.

My Proclamation will not, therefore, be issued until that vote is cast on the fifth day of December next. I regret that this delay must occur, as the circumstances which surround us make prompt and decided action necessary. There can be no doubt that a large

Page 14

majority of the electorial vote will be given to Mr. Lincoln, and in view of the certainty of his election, I have determined to issue my Proclamation immediately after that vote is cast. I shall appoint Monday, the 24th day of December next, for the election of delegates to the Convention. The Convention will meet on Monday, the 7th day of January next.

The day for the election of delegates has been designated in advance of the issuance of the Proclamation in order that the minds of the people may at once be directed to the subject, and that the several counties may have ample time to select candidates to represent them. Each voter of the State should immediately consider the importance of the vote he is to cast. Constitutional rights, personal security, and the honor of the State are all involved. He must decide, on the 24th December, the great and vital question of submission to an Abolition Administration, or of secession from the Union. This will be a grave and momentous issue for the decision of the people. To decide it correctly, they should understand all the facts and circumstances of the case before them. It may not be improper or unprofitable for me to recite a few of them.

Who is Mr. Lincoln, whose election is now beyond question? He is the head of a great sectional party calling itself Republican: a party whose leading object is the destruction of the institution of slavery as it exists in the slaveholding States. Their most distinguished leaders, in and out of Congress, have publicly and boldly proclaimed this to be their intention and unalterable determination. Their newspapers are filled with similar declarations. Are they in earnest? Let their past acts speak for them.

Nearly every one of the non-slaveholding States have been for years under the control of the Black Republicans. A large majority of these States have nullified the fugitive slave law, and have successfully resisted its execution. They have enacted penal statutes, punishing, by fine and imprisonment in the penitentiary, persons who may pursue and arrest fugitive slaves in said State. They have by law, under heavy penalties, prohibited any person from aiding the owner to arrest his fugitive slave, and have denied us the use of their prisons to secure our slaves until they can be removed from the State. They have robbed the South of slaves worth millions of dollars, and have rendered utterly ineffectual the only law passed by Congress to protect this species of property. They have invaded the State of Virginia, armed her slaves with deadly weapons, murdered her citizens, and seized the United States Armory at Harper's Ferry. They have sent emissaries into the State of Texas, who burned many towns,

Page 15

and furnished the slaves with deadly poison for the purpose of destroying their owners.

All these things have been effected, either by the unconstitutional legislation of free States, or by combinations of individuals. These facts prove that they are not only in earnest and intent upon accomplishing their wicked purposes, but have done all that local legislation and individual efforts could effect.

Knowing that their efforts could only be partially successful without the aid of the Federal Government, they for years have struggled to get control of the Legislative and Executive Departments thereof. They have now succeeded, by large majorities, in all the non-slaveholding States except New Jersey, and perhaps California and Oregon, in electing Mr. Lincoln, who is pledged to carry out the principles of the party that elected him. The course of events show clearly that this party will, in a short time have a majority in both branches of Congress. It will then be in their power to change the complexion of the Supreme Court so as to make it harmonize with Congress and the President. When that party get possession of all the Departments of Government, with the purse and the sword, he must be blind indeed who does not see that slavery will be abolished in the District of Columbia, in the dock-yards and arsenals, and wherever the Federal Government has jurisdiction.

It will be excluded from the Territories, and other free States will in hot haste be admitted into the Union, until they have a majority to alter the Constitution. Then slavery will be abolished by law in the States, and the "irrepressible conflict" will end; for we are notified that it shall never cease, until "the foot of the slave shall cease to tread the soil of the United States." The state of society that must exist in the Southern States, with four millions of free negroes and their increase, turned loose upon them, I will not discuss--it is too horrible to contemplate.

I have only noticed such of the acts of the Republican party as I deem necessary to show that they are in earnest, and determined to carry out their publicly avowed intentions--and to show that their success has been such as should not fail to create the deepest concern for the honor and safety of the Southern States.--Now, in view of the past and our prospects for the future, what ought we to do? What do wisdom and prudence dictate?--What do honor and safety require at our hands?

I know that the answer that I shall give to these questions may subject me to severe criticism by those who do not view these matters as I do; but feeling conscious of the corrrectness of my conclusions, and the purity of my motives, I will not shrink from

Page 16

responsibilities in the emergency which presents itself. It would be criminal "in those entrusted with State sovereignty" not to speak out and warn the people of the encroachments that have been made, and are about to be made upon them, with the consequences that must follow.

In full view, and, I trust, a just appreciation of all my obligations and responsibilities, officially and personally, to my God, my State, and the Federal Government, I solemnly declare it to be my opinion, that the only hope of future security, for Alabama and the other slaveholding States, is secession from the Union.--I deplore the necessity for coming to such a conclusion. It has been forced upon me, and those who agree with me, by a wicked and perverse party, fatally bent upon the destruction of an institution vital to the Southern States--a party whose constitutional rights we have never disturbed, and who should be our friends; yet they hate us without a cause.

Should Alabama secede from the Union, as I think she ought, the responsibility, in the eyes of all just men, will not rest upon her, but upon those who have driven her in self-defence, to assume that position.

Has Alabama the right peacefully to withdraw from the Union, without subjecting herself to any rightful authority of the Federal Government to coerce her into the Union? Of her right to do so, I have no doubt. She is a Sovereign State, and retains every right and power not delegated to the Federal Government in the written Constitution. That Government has no powers, except such as are delegated in the Constitution, or such as are necessary to carry these powers into execution. The Federal Government was established for the protection, and not for destruction or injury of Constitutional rights. A Sovereign State has a right to judge of the wrongs or injuries that may be done her, and to determine upon the mode and measures of redress. The Black Republican party has for years continued to make aggressions upon the slaveholding States, under the forms of law, and in every manner that fanaticism could devise, and have now gained strength and position, which threaten, not only the destruction of the institution of slavery, but must degrade and ruin the slaveholding States, if not resisted. May not these States turn aside from the impending danger, without criminality? If they have not this right, then we are the slaves of our worst enemies. "The wise man foreseeth the evil and turneth aside." A wise State should not do less.

If Alabama should withdraw from the Union, she would not be guilty of treason, even if a Sovereign State could commit treason.

Page 17

The Constitution says: "Treason against the United States shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort." The Federal Government has the right to use its military power "to execute the laws of the Union, surpress insurrections, and repel invasions." If a State withdraws from the Union, the Federal Government has no power, under the Constitution, to use the military force against her, for there is no law to enforce the submission of a sovereign State, nor would such a withdrawal be either an insurrection or an invasion. We should remember that Alabama must act and decide the great question of resistance or submission, for herself. No other State has the right or power to decide for her. She may, and should, consult with the other slaveholding States to secure concert of action, but still, she must decide the question for herself, and coöperate afterwards.

The contemplated Convention will not be the place for the timid or the rash. It should be composed of men of wisdom and experience--men who have the capacity to determine what the honor of the State and the security of her people demand; and patriotism and moral courage sufficient to carry out the dictates of their honest judgments.

What will the intelligent and patriotic people of Alabama do in the impending crisis? Judging of the future by the past, I believe they will prove themselves equal to the present, or any future emergency, and never will consent to affiliate with, or submit to be governed by a party who entertains the most deadly hostility towards them and their institution of slavery. They are loyal and true to the Union, but never will consent to remain degraded members of it.

Very respectfully, your obd't serv't,

A. B. MOORE.

The following is a copy of the Proclamation issued by the Governor:

PROCLAMATION.

EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT,

Montgomery, Ala., Dec. 6, 1861.

WHEREAS, the following Joint Resolutions were passed at the last session of the General Assembly of the State of Alabama, to-wit:

[Reciting the Resolutions on page 9.]

Now, I, A. B. MOORE, Governor of the State of Alabama, by virtue of the power vested in me by the foregoing resolutions, and

Page 18

in obedience thereto, do hereby proclaim and make known to the people of Alabama, that the contingency contemplated in said Preamble and Resolutions has happened in the election of Abraham Lincoln to the Presidency of the United States. The qualified voters of the several counties of the State are, therefore, hereby called upon to assemble at the several places of voting in their respective counties, on Monday, the 24th December, 1860, to elect delegates to a Convention of the State of Alabama, to be held at the capitol in the city of Montgomery, on Monday, the 7th day of January next, to "consider determine and do whatever, in the opinion of said Convention, the rights, interests and honor of the State of Alabama require to be done for their protection."

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused [L. S.] the Great Seal of the State to be affixed in the city of Montgomery, this 6th day of December, A. D. 1860.

By the Governor,

A. B. MOORE.

J. H. WEAVER, Secretary of State.

Page 19

HISTORY AND DEBATES OF THE CONVENTION.

FIRST DAY.

ON the 7th January, 1861, the Convention assembled in the city of Montgomery, in the Hall of the House of Representatives of the State Capitol. It is a remarkable fact, that, of the one hundred Delegates of which the Convention was constituted, not one was absent. This was owing, doubtless, to the great anxiety, on the part of the Delegates, to participate in the earliest proceedings; and also, I apprehend, to the doubt that existed, previous to the organization, as to whether the straight-Secession party or the Coöperation party was in the majority. On the Sunday night before the Convention met, each party seriously claimed the ascendancy; but before the hour for organizing the Convention, it was conceded that the Secession party was the stronger.

Great precaution had been taken in advance, to secure an harmonious organization; and for this purpose it had been agreed, at first, that one member of each party, to be designated before the meeting, should approach the desk, call the Convention to order and nominate a temporary President; but the Coöperation party, convinced, by having accurately measured their strength, that they were in a minority, deemed it proper to yield the organization of the Convention to the majority; of which fact the latter were duly advised.

On motion of the Hon. H. G. Humphries, the Hon. William S. Phillips, of Dallas, was called to the Chair, as temporary President; and A. G. Horn, of Mobile, and S. D. Brewer, of Montgomery, were appointed temporary Secretaries.

Page 20

MR. YANCEY offered the following Resolutions, which were unanimously adopted:

Resolved, 1st. That the proceeding of the Convention be opened with prayer, and that the Rev. Dr. Manly be invited to perform this service to-day.

Resolved, 2d. That the President of the Convention be requested to invite some Clergyman to open the Convention with prayer each successive day of the session.

The Convention was then opened with prayer by Rev. Basil Manly, formerly President of the University of Alabama.

PRAYER.

Almighty Father, Maker of Heaven and Earth; King eternal, immortal, invisible; the only wise God! We adore Thee, for Thou art God, and besides Thee there is none else; our Fathers' God, and our God! We thank Thee that Thou hast made us men, endowed with reason, conscience and speech--capable of knowing, loving and serving Thee! We thank Thee for Thy Son, the Lord Jesus Christ, our only Mediator and Redeemer! We thank Thee for Thy word of truth, our guide to eternal life. We thank Thee for civil government, ruling in Thy fear; and we especially thank Thee that Thou didst reserve this fair portion of the earth so long undiscovered, unpolluted with the wars and the crimes of the old world--that Thou mightest here establish a free government and a pure religion. We thank Thee that Thou hast allotted us our heritage here, and hast brought us upon it at such a time as this. We thank Thee for all the hallowed memories connected with the establishment of the independence of the Colonies, and their sovereignty as States, and with the formation and maintenance of our government, which we had devoutly hoped might last, unperverted and incorruptible, as long as the sun and moon endure.

Oh, our Father! we have striven as an integral part of this great Republic, faithfully to keep our solemn covenants in the Constitution of our country; and our conscience doth not accuse us of having failed to sustain our part in the civil compact. Lord of all the families of the earth! we appeal to THEE to protect us in the land Thou hast given us, the Institutions Thou hast established, the rights Thou hast bestowed! And now, in our troubles, besetting us like great waters round about, WE, Thy dependent children, humbly entreat Thy fatherly notice and care. Grant to Thy servants now assembled, as the direct representatives of the people of this State, all needful grace and wisdom for their peculiar and great responsibilities at this momentous crisis! Give

Page 21

them a clear perception of their duties, as the embodiment of the people; impart to them an enlightened, mature and sanctified judgment in forming every conclusion; a steady, Heaven-directed purpose and will in attaining every right end! Save them from the disturbing influences of error, of passion, prejudice and timidity--from divided and conflicting counsels; give them one mind and one way, and let that be the mind of Christ! If Thou seest them ready to go wrong, interpose Thy heavenly guidance and restraint; if slow and reluctant to execute what duty and safety require, quicken and urge them forward! Let patient enquiry and candor pervade every discussion; let calm, comprehensive and sober wisdom shape every measure, and direct every vote; let all things be done in Thy fear, and with a just regard to their whole duty toward God and toward man! Preserve them all in health, in purity, in peace; and cause that their session may promote the maintenance of equal rights, of civil freedom and good government; may promote the welfare of man, and the glory of Thy name! We ask all through Jesus Christ, our Lord: Amen!

The Convention consisted of one hundred Delegates, each of whom being present, approached the Clerk's desk, as his county was called, and enrolled his name.

NAMES OF THE DELEGATES AS ENROLLED.

From the county of

Autauga--George Rives.

Barbour--John Cochran, Alpheus Baker, J. S. M. Daniel.

Baldwin--Jos. Silver.

Bibb--James W. Crawford.

Blount--John S. Brasher, W. M. Edwards.

Butler--Samuel J. Bolling, John McPherson.

Calhoun--Daniel T. Ryan, John M. Crook, G. C. Whatley.

Chambers--J. F. Dowdell, Wm. H. Barnes.

Cherokee--Henry C. Sanford, Wm. L. Whitlock, John Potter, John P. Ralls.

Choctaw--S. E. Catterlin, A. J. Curtis.

Clark--O. S. Jewett.

Coffee--G. T. Yelverton.

Conechu--John Green.

Coosa--George Taylor, John B. Leonard, Albert Crumpler.

Covington--Dewitt C. Davis.

Dallas--John T. Morgan, Wm. S. Phillips.

Dale--D. B. Creech, James McKinnie.

DeKalb--Wm. O. Winston, John Franklin.

Page 22

Fayette--B. W. Wilson, E. P. Jones.

Franklin--John A. Steele, R. S. Watkins.

Greene--James D. Webb, Thos. H. Herndon.

Henry--Hastings E. Owens, Thomas T. Smith.

Jackson--John R. Coffey, Wm. A. Hood, John P. Timberlake.

Jefferson--Wm. S. Earnest.

Lauderdale--S. C. Posey, H. C. Jones.

Laurence--D. P. Lewis, James S. Clarke.

Limestone--J. P. Coman, Thos. J. McClellan.

Loundes--James S. Williamson, Jas. G. Gilchrist.

Macon--Samuel Henderson, O. R. Blue, J. M. Foster.

Madison--Nich. Davis, Jere. Clemens.

Marshall--A. C. Beard, James L. Sheffield.

Marengo--W. E. Clarke.

Marion--Lang. C. Allen, W. Steadham.

Mobile--John Bragg, George A. Ketchum, E. S. Dargan, H. G. Humphries.

Monroe--Lyman Gibbons.

Montgomery--Wm. L. Yancey, Thos. H. Watts.

Morgan--Jonathan Ford.

Perry--Wm. M. Brooks, J. F. Baily.

Pickens--Lewis M. Stone, W. H. Davis.

Pike--Eli W. Starke, Jeremiah A. Henderson, A. P. Love.

Randolph--H. M. Gay, George Forrester, R. J. Wood.

Russell--R. O. Howard, B. H. Baker.

Shelby--Geo. D. Shortridge, J. M. McClanahan.

St. Clair--John W. Inzer.

Sumpter--A. A. Coleman.

Talladega--N. D. Johnson, A. R. Barclay, M. G. Slaughter.

Tallapoosa--A. Kimball, M. J. Bulger, T. J. Russell.

Tuscaloosa--R. Jemison, Jr., W. R. Smith.

Walker--Robert Guttery.

Washington--James G. Hawkins.

Wilcox--F. R. Beck.

Winston--C. C. Sheets.

As the Delegates from the county of Montgomery, Hon. Wm. L. Yancey and Hon. T. H. Watts, approached the desk to enroll their names, there were some demonstrations of applause in the gallery; whereupon Mr. Morgan offered the following Resolution:

That the members of this Convention will abstain from applause on all occasions; and that all demonstrations of applause in the galleries or lobby shall be strictly prohibited.

Page 23

MR. MORGAN said:

Mr. President--I sympathise fully with the sentiment that impels the Delegates on this floor, and the people in the galleries, to indulge in demonstrations of applause, but I deprecate the effect of this excitement upon our deliberations. I have respect for the occasion, and I feel assured that the best way to evince my feeling is by a dignified and respectful course of discussion and deliberation. I have respect for the Convention and desire to see it respected by others. If every speaker on this floor is to be openly and loudly applauded or condemned, as his opinions may meet with popular favor or rebuke, we shall have much to regret before we close our labors here.

I take this early opportunity to offer a resolution on this subject and to strike at the evil when it first begins to display itself in a compliment to our most distinguished friends, who have just enrolled their names.

The Convention then proceeded to the election of a permanent President. Mr. Beck nominated Wm. M. Brooks, of Perry;-- Mr. Davis, of Madison, nominated Robert Jemison, Jr., of Tuscaloosa.

In casting up the vote, it appeared that Mr. Brooks had received 53 votes; Mr. Jemison, 45. This was the entire vote, and was a test of the relative strength of parties--there being, including Mr. Brooks, fifty-four who favored immediate secession, and forty-six, including Mr. Jemison, who were in favor of consulting and cooperating with the other slave-holding States.

Mr. Brooks was declared duly elected; and Messrs. Bragg Winston and Humphries were appointed to wait upon him, by whom he was conducted to the Chair. He delivered an appropriate address, and assumed the duties of his office.

Wm. H. Fowler, of Tuscaloosa, was elected Secretary; Frank. L. Smith, of Montgomery, was elected assistant Secretary; and Robert H. Wynn was elected Door-keeper.

The President laid before the Convention the credentials* of

* Credentials of the Commissioner from South Carolina. THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA: WHEREAS, Andrew P. Calhoun has been duly elected by a vote of the Convention of the people of the State of South Carolina, to act as a Commissioner to the Convention of the people of the State of Alabama, and the said people of the State of South Carolina, has ordered the Governor of said State to commission the said Andrew P. Calhoun. Now, therefore, I do hereby commission you, the said Andrew P. Calhoun, to act as a Commissioner from the State of South Carolina, in Convention assembled, to the State of Alabama, in Convention assembled, to confer upon the subjects entrusted to your charge. Wittness, His Excellency, Francis W. Pickens, Governor and Commander-in-Chief of said State, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord, One Thousand Eight Hundred and Sixty-one, and the Eighty-fifth year of the Sovereignty and Independence of the State of South Carolina. [Seal of State.] JAMES A. DUFFAS, By the Governor.

Deputy Secretary State

Page 24

the Hon. Andrew P. Calhoun, as a Commissioner from the State of South Carolina. On motion of Mr. Yancey, it was

Resolved, That a Committee of three be appointed to wait upon the Hon. Andrew P. Calhoun, Commissioner from the State of South Carolina, and request him to address the Convention at such time as he may designate, and that he be invited to take a seat within the bar of the Convention.

Messrs. Yancey, Webb and Davis, of Madison, were appointed.

On motion by MR. COCHRAN, it was

Resolved, That the Governor of the State be requested to communicate to this Convention any information he may have respecting the condition of the country.

RESOLUTION OF RESISTANCE.

The first debate in the Convention arose upon the following Resolutions, offered by MR. WHATLEY:

WHEREAS, the only bond of union between the several States is the Constitution of the United States; and WHEREAS, that Constitution has been violated, both by the Government of the United States, and by a majority of the Northern States, in their separate legislative action, denying to the people of the Southern States their Constitutional rights;

And WHEREAS, a sectional party, known as the Black Republican Party, has, in the recent election, elected Abraham Lincoln to the office of President, and Hannibal Hamlin to the office of Vice-President of these United States, upon the avowed principle that the Constitution of the United States does not recognise properly

Page 25

in slaves and that the Government should prevent its extension into the common Territories of the United States, and that the power of the Government should be so exercised that slavery, in time, should be exterminated:

Therefore, be it Resolved, by the people of Alabama, in solemn Convention assembled, That these acts and designs constitute such a violation of the compact, between the several States, as absolves the people of Alabama from all obligation to continue to support a Government of the United States, to be administered upon such principles, and that the people of Alabama will not submit to be parties to the inauguration and administration of Abraham Lincoln as President, and Hannibal. Hamlin as Vice President of the United States of America.

On submitting the Resolutions, MR. WHATLEY said:

Mr. President--I offer these Resolutions for the purpose, in the outset, to ascertain the sense of this body upon the question of submission or resistance to Lincoln's Administration. It is known that there are different opinions entertained by members of this Convention; many have been elected as straight-out secessionists, others as coöperationists, and among the coöperationists there is a diversity of opinion. Some are for coöperating with the entire South, others for a coöperation with the Cotton States, and likely some are willing to cöoperate with a majority of the Cotton States. It is said, there are some in this body who are for absolute submission; I trust though, these suspicions are not true, and that we shall present an undivided front, in antagonism to the Black Republican administration. In the language of the Joint Resolutions, of the last session of our Legislature, let us assert that, "Alabama, acting for herself, has solemnly declared that, under no circumstances will she submit to the foul domination of a sectional Northern party." I desire, therefore, to ascertain, definitely, the sense of this body upon the question of submission or resistance. If we shall determine for resistance, as no doubt we will, then the next step will be, what kind of resistance shall we offer?

MR. SMITH, of Tuscaloosa:

Mr. President--I do not object, so much to the resolutions themselves, as to the reasons assigned by the gentleman, [Mr. Whatley,] for their introduction. It is proclaimed that this is intended as a test; the test as to submission! The intimation is ungenerous. It is inconsistent with the desires of harmony and conciliation

Page 26

that have been openly expressed here by all parties. It is an injudicious beginning of our deliberations. It is true, that it has been ascertained by the elections which have just been had here, that we are a minority. I am of that minority; but I do not associate with submissionists! There is not one in our company. We scorn the prospective Black Republican rule as much as the gentleman from Calhoun, [Mr. Whatley,] or any of his friends.

There is, in the gentleman's speech, besides the undisguised expression of suspicion, the appearance of a desire to stir up enemies, instead of a desire to harmonize friends. If this is the harmony you preach and practice, you will have nothing in this Convention but the most unpleasant scenes of stubborn, sullen, and unyielding antagonism. All good men should deprecate that.

The leading sentiments of the resolutions I endorse. I am perfectly willing to express a determination to resist a Black Republican Administration; but I may not choose to vote for this long string of resolutions. Present a naked question of resistance to Black Republican rule, and you will doubtless receive a unanimous vote in favor of it. But do not so interlard it with generalities and political abstractions that we shall be forced to reject the good on account of its too close association with the evil. I object particularly to make an intimation that I would oppose by force the inauguration of Lincoln. I would not have anything to do with that in any way. I deprecate the idea of intimating to the people, even remotely, that the laws ought not to be respected.

If gentlemen are earnest in their wishes to procure here, and at this time, an emphatic expression of resistance, I have no doubt that the resolutions can be so amended as to meet the cordial support of all of us.

I am not willing to say, as does this resolution, that the separate action of any State has absolved Alabama from all obligation to continue to support the Government of the United States. A State may violate the Constitution and still the General Government may not be at fault.

Let the resolutions be amended--stripped of their verbiage, so as to present the single question of resistance, placed in its true position, and I will support them.

MR. POSEY said:

He opposed the resolutions, because the first recital in the preamble places resistance to Mr. Lincoln's Administration upon the aggressions of the Federal Government, as well as those of

Page 27

the Northern States. The last charge is true; the first is not true. There have been no aggressions on the part of the Federal Government; there has been an omission, it may be, in some instances, to execute the Fugitive Slave law, which we well know proceeded from the hatred of Northern Abolitionists to that law. The aggressions of which we have just cause to complain, have been made by the people in some of the Northern States, and by the Personal Liberty Bills of thirteen of these States. They have violated the Constitution of the United States, in these unconstitutional enactments.

Mr. Posey admitted the South could not submit to the princi ples presented in the Chicago Platform. Resistance to the issues made up in that Platform was forced upon the people of this State. They had no other alternative placed before them in the Chicago Creed, but exclusion from the Territories of the United States, with the ultimate extinction of slavery as the consequence of such exclusion and injustice, or resistance to any administration of the Government upon such principles.

These resolutions indicate, clearly, one mode of resistance only. This is not expressed, but the fair construction is, that separate State secession is the kind of resistance pledged by these resolutions; when it is well known that the coöperationists in this Convention have declared their opposition to the principles of the Black Republican party, and their determination to resist a Government administered upon their policy; but their plan of resistance is not by separate State action. We intend to resist. It is not our purpose to submit to the doctrines asserted at Chicago; but our resistance is based upon consultation, and in unity of action, with the other slave States.

If we vote for these resolutions, in their present shape, we shall have committed ourselves to separate State action, to which the cooperationists in this body stand opposed, for the reason, we greatly prefer another mode of resistance, considered by us to be safer for the country, and not less effectual in asserting and maintaining all our just rights.

MR. YANCEY said:

Mr. President--I favor the passage of these resolutions. That they are a test--ascertaining whether there are any submissionists or not in this body, is no objection to them in my mind. It is said they are offensive because it is a test. They ought not to be offensive, in my opinion, to any Delegate who is not in favor of submitting to Lincoln's Administration. That there are such

Page 28

here, I am unwilling to believe, and I desire that the world shall know there are none such, if such is the fact; while at the same time, if there are any, I desire to know it, and the Convention should know it.

It has been said that this resolution will create discord amongst us--and is not conciliatory. It can only justly be so considered by those opposed to all resistance to the Black Republican power. I, for one, have no desire to conciliate persons occupying such position. I wish here, and elsewhere, to antagonise them.

The resolutions are designed, in my apprehension, to lay a basis for our future action. If we are, as I hope we shall be, united in favor of these resolutions, there can be but little difficulty in our taking some action, which will be agreeable to us all. If, however, there shall be any here opposed to these resolutions, we cannot have united action.

It will be observed, that the resolutions are carefully worded and framed. They do not designate the mode of resistance.--They offend no man's opinion upon the question of secession or revolution. They do not discriminate in favor of separate, or of coöperative State action. They simply discriminate between those who are willing to continue the Union upon the principles of the Black Republican party, and those who are willing to resist them, and to dissolve the Union rather than see the Government administered upon those principles.

With all who can vote for these resolutions, I can confer, and hope to come to a common conclusion. With those who shall vote against them, I have neither feeling or principle in common.

MR. CLEMENS said:

Mr. President--I object to this resolution, not so much on account of its terms, as on account of the avowed motives which prompted its introduction. The gentleman from Calhoun tells us that he desired to ascertain whether there is any one here who is willing to submit to a Black Republican Administration, and he proposes this resolution as a test. Now, sir, the proposition to make a test on such a subject, necessarily implies suspicion, and suspicion is always more or less offensive. If, therefore, the gentleman is a correct exponent of the wishes and feelings of the majority--if that is the temper in which we of the minority are to be met, I give them warning that our session is likely to be a stormy one. We may be persuaded to go a long ways. We cannot be driven an inch in any direction, and the attempt to do it will not only result in failure, but must produce a state of things whose consequences I will not picture.

Page 29

I came here, Mr. President, rightly appreciating, as I think, the difficulties before us, and prepared to do all that ought to be done to promote harmony among our own people. I see very plainly that a time is coming when our very existence as an independent people will materially depend upon a cordial union among ourselves. I am no believer in peaceable secession. I know it to be impossible. No liquid but blood has ever filled the baptismal fount of nations. The rule is without an exception, and he has read the book of human nature to little purpose who expects to see a nation born except in convulsions, or christened at any alter but that of the God of battles. So thinking, and so believing, I have felt that it was the duty of a patriot to conciliate--not to influence; to keep constantly before his eyes the one great duty of reconciling conficting opinions, and smoothing away existing asperities. Such, I am sure, is the general feeling of my party friends. But we are men, with all the frailties of men, and the avowal of insulting suspicions--the introduction of test resolutions, and similar aggravating annoyances, will be certain to end in scenes alike discreditable to this body, and injurious to the best interests of the State.

I do not acknowledge that the gentleman from Calhoun is prepared to go any farther than I am, in resistance to Black Republican domination. There is no danger to be incurred in such a cause, so great that I will shrink from sharing it with him. There is no extremity of resistance he can propose, in which I will not join him, provided it promises to be effectual; but I do not concede his right, or the right of any man, to make a test for me.--No man shall make it; and if his purpose be to ascertain the real sense of this Convention, upon the subject-matter of his resolution, I tell him that he has adopted the wrong course, and his effort will end in failure. For one, I shall take the responsibility of voting NO. My belief is, that there are forty-five others who will do the same thing, and what then becomes of his test? He would be very unwilling, I imagine, to let the impression go abroad that there are forty-six members of this Convention in favor of submitting to the rule of a Black Republican President, elected upon a Black Republican platform; and yet, sir, I see nothing more that he is likely to accomplish.

I shall make no proposition to amend. I shall not seek to evade a direct vote by any parliamentary expedient. I am ready to record my name upon the resolution as it stands. I shall vote NO, and leave the consequences to take care of themselves.

MR. WILLIAMSON said:

The resolutions under consideration are eliciting more discussion

Page 30

than I expected, since all, so far as I am informed, are agreed that Alabama cannot, and will not, submit to the Administration of Lincoln and Hamlin. The resolutions affirm nothing more. If there are any here who think otherwise, let them come out like men and say so. This would make an issue, and relieve them from the disagreeable task of resorting to parliamentary subterfuges, for the purpose of escaping discussion, and avoiding a direct vote on the main question. When I first heard the resolutions read from the Secretary's desk, I flattered myself they would be unanimously adopted without debate. I still flatter myself that the objections are to the verbiage and not to the question involved. If so, I hope gentlemen will at once point out the word or words. If opposed to the resolutions, let them state the grounds of their objections, and offer amendments indicating the desired change. I deem it important to adopt the resolutions forthwith; consequently am prepared to accommodate gentlemen by voting for any amendment not incompatible with the meaning and spirit of the resolutions, as they now stand.

MR. WHATLEY said:

Mr. President--Gentlemen of this body have misapprehended my object in offering the resolutions at this early day of our session. The resolutions are not offered to throw a fire-brand into the deliberations of this body. I imagine, gentlemen representing the sovereign people of Alabama, are ready, even now, to take position upon this subject. We are misrepresented at home and abroad. We are represented North as submissionists. Even in this city, different public prints represent us in different ways, and particularly in the Northern portion of our own State are our positions misrepresented. I desire, sir, that these misrepresentations may be speedily corrected, and that even during this day the telegraphic wires may transmit the glad intelligence abroad, that Alabama will never submit to a Black Republican Administration.

This discussion was continued, with much animation, a considerable time, and the resolution was so amended as to satisfy all parties, and was passed unanimously, in the following shape:

Resolved, By the people of Alabama, in Convention assembled' That the State of Alabama cannot, and will not, submit to the Administration of Lincoln and Hamlin as President and Vice President of the United States, upon the principles referred to in the preamble.

Page 31

SECOND DAY.

January 8th.--Mr. YANCEY, from the Committee to wait on the Hon. Andrew P. Calhoun, Commissioner from South Carolina, reported that the Committee had performed that duty, and that Mr. Calhoun was ready to address the Convention at such time as it should desire.

On motion by Mr. Jones, of Lauderdale, it was

Resolved, That the Hon. A. P. Calhoun, Commissioner from South Carolina to the State of Alabama, be requested to address the Convention at this time, and make such communications as he may desire.

Mr. Calhoun was then introduced, and addressed the Convention, in substance, as follows:

MR. PRESIDENT AND GENTLEMEN OF THE CONVENTION:

It is one of the most agreeable incidents of my life that the Convention of the people of South Carolina--my native State--should have elected me a Commissioner to the State of Alabama, for many years my adopted one. South Corolina could doubtless have sent an abler son to represent her, but she could not have sent one whose heart was filled with more kindness and attachment, or one who would extend the hand of fellowship with greater sincerity or regard. It was during the many years I sojourned among you, I learnt how to appreciate the intelligence and energy of your citizens, and how properly to estimate the vast and varied resources of your State: a State second to but one as a cotton producer; to none in mineral wealth, especially in coal and iron; so potent to the world, either in the mission of peace or war: a State that instructed her Governor to call a Convention in the event of the election of a Black Republican for the presumed purpose of meeting the great issue: To such a State, South Carolina would willingly have assigned the position of leadership in the great drama of events that are pressing to a rapid solution. But by a combination of accidental causes, the initiation of the contest devolved upon South Carolina. The Governor of South Carolina called an extra session of the Legislature to elect Electors to cast the Presidential vote of that State. Continuing in session for a few days, the election of a Black Republican or sectional candidate, was declared; and feeling that submission would be both degredation and annihilation, she called a Convention forthwith of the people to assemble on the 17th of December. At once the State

Page 32

up. It was an up-heaving of the people. No leader or leaders could have resisted it, or stemmed its impetuosity. The wave of public opinion swept over the lower, the middle, and leaped into the recess of the mountain districts. The result was, the Convention assembled with unprecedented unanimity. Some time was lost in consequence of a loathsome epidemic raging in Columbia, that forced the Convention to adjourn to Charleston. On the 19th a cheering voice from Alabama was heard. Your esteemed Commissioner,*

*Hon. John A. Elmore, of Montgomery, Commissioner from Alabama to South Carolina.

who so ably represented your State, and was so acceptable to the one to which he was accredited, presented a telegram from your patriotic and popular Governor, that carried an electric thrill through every heart--"tell the Convention to listen to no proposition of compromise or delay." The next day, the 20th, came the Ordinance annulling the compact which South Carolina had entered into in 1788 with twelve other sovereign States, and resuming all delegated power, she became a free, sovereign, and independent commonwealth. At this point, the accumulated aggressions of the third of a century fell like shackles at her feet, and free, disinthralled, regenerated, she stood before her devoted people like the genius of Liberty, beckoning them on to the performance of their duty.

The argument closes here so far as Federal aggressions in South Carolina are concerned. But may we not pause in reverence and admiration before the vast monument built up by Southern genius and eloquence, in defending and warning a pursecuted section of the measured approach of despotism, and that, too, in the face of the frowns and blandishments of power; and there were some who, braving the imprecations of the enemy, and the importunities of friends, persisted in performing their sacred duty to their section at all and every sacrifice.

In obedience to instructions, I now present a certified copy of "An Ordinance" to dissolve the Union between the State of South Carolina and other States, united with her under the compact entitled the "Constitution of the United Statss of America." I am also instructed to invite your coöperation with South Carolina in the formation of a Southern Confederacy, and to submit the Federal Constituion as the basis of a provisional government.--That instrument, with the Southern construction given to it, would be safe until it, or one, could be deliberately amended and perfected. The exigency requires for the present, prompt and efficient action, and for this purpose I am instructed to invite your State to meet her in Convention at the earliest practicable day.

Page 33

Mr. C. proceeded to say that, before he left Charleston, the Commissioners to the several States, in a meeting, had determined to suggest the first Monday in February, the 3d. He said he had heard Montgomery suggested, but was not authorized to say anything on that point himself. Mr. C. here presented the Report and Resolutions from the Committee on "Relations with slaveholding States, providing for Commissioners to such States," and read the Resolutions appended to the report, which he then submitted to the Convention. He also submitted "The address of the people of South Carolina, assembled in Convention, to the people of the slaveholding States," and then proceeded: That no better illustration of the insidious approach and consummation of despotism can be found in history, than the progress of the Government of the United States to consolidation and the usurpation of every vestige of State sovereignty. Even the mask that covered its aggressions is now dropped, and it is making war and striking at independent States that warmed it into life. Be it so. The day of endurance is past. The government of the United States will stand out in history a mock and reproach to every friend of freedom or free institutions. We are in the midst of events, and enacting them, that will effect the condition, not only of ourselves but the world, for weal or woe. In South Carolina, we feel the justice of our cause: we will defend our State to the last extremity, be the consequences what they may. A common cause unites Alabama and South Carolina and the other cotton States. An Union at the earliest day between them will guarantee success.--We cannot be conquered; but united, we will hurl defiance at our assailants. The flag of Independence and resistance is unfurled in my State from the mountains to the sea-board. Old and young rally to its standard with the determination, if the attempt is made to coerce us, that we will "die freemen rather than live slaves."

Mr. Calhoun then laid before the Convention sundry documents, connected with his mission, which will be found in another part of this volume.

This HISTORY would not be complete if it were to conceal the great excitement that prevailed in the Convention, and the deep interest that every member felt in passing events. Telegraphic dispatches were frequently received and read, and served the purpose of keeping up the animation.

Page 34

On this day Mr. Watts placed the following dispatches before the Convention:

BY TELEGRAPH FROM WASHINGTON, JANUARY 7, 1861.

"The Republicans in the House, to-day, refused to consider the border State compromise--complimented Maj. Anderson, and pledged to sustain the President."

MOORE & CLOPTON.

TELEGRAPH FROM RICHMOND TO GOV. MOORE.

Legislature passed, by one hundred and twelve (112) to five (5), to resist any attempt to coerce a seceding State, by all the means in her power. What has your Convention done? Go out promptly and all will be right."

A. F. HOPKINS,

F. M. GILMER.

The Governor sent up the following Message, in answer to the resolution of yesterday:

Executive Department,

Montgomery, Ala., Jan. 8, 1861.

GENTLEMEN OF THE CONVENTION:

In obedience to the resolution adopted by the Convention yesterday, requiring me to communicate any information I may have respecting the condition of the country, I herewith transmit such information as is in my possession, touching the public interests, and a brief statement of my acts in regard thereto, and the reasons therefor. All of which are respectfully submitted to the consideration of the Convention.

Very respectfully,

A. B. MOORE.

The General Assembly at its last session passed unanimously, with two exceptions, resolutions requiring the Governor, in the event of the election of a Black Republican, to order elections to be held for delegates to a Convention of the State. The contingency contemplated having occurred, making it necessary for me to call a Convention, writs of election were issued immediately after the votes of the electorial college were cast. It was my opinion that, under the peculiur phraseology of the resolutions, I was not authorized to order elections upon the casting of the popular vote. I, therefore, determined not to do so.

As the slaveholding States have a common interest in the institution

Page 35

of slavery, and must be common sufferers in its overthrow, I deemed it proper, and it appeared to be the general sentiment of the people, that Alabama should consult and advise with the other slaveholding States, so far as practicable, as to what is best to be done to protect their interest and honor in the impending crisis. And seeing that the Conventions of South Carolina and Florida would probably act before the Convention of Alabama assembled, and that the Legislatures of some of the States would meet, and might adjourn without calling Conventions, prior to the meeting of our Convention, and thus the opportunity of conferring with them upon the great and vital questions on which you are called to act--I determined to appoint Commissioners to all the slaveholding States. After appointing them to those States whose Conventions and Legislatures were to meet in advance of the Alabama Convention, it was suggested by wise counselors, that if I did not make similar appointments to the other Southern States, it would seem to be making an invidious distinction, which was not intended. Being convinced that it might be so considered, I then determined to appoint Commissioners to all the slaveholding States, and made the following appointments:

A. F. Hopkins and F. M. Gilmer, Commissioners to Virginia. John A. Elmore, Commissioner to South Carolina.

I. W. Garrott and Robert H. Smith, Commissioners to North Carolina.

J. L. M. Curry, Commissioner to Maryland.