Our Danger and Our Duty:

Electronic Edition.

Thornwell, James Henley, 1812-1862

Funding from the Institute of

Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this

title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Gretchen Fricke

Image scanned by

Gretchen Fricke

Text encoded by

Fiona Mills and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 50K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Call number 2859 Conf. (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American

South.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and '

respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as --

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

- LC Subject Headings:

- Duty.

- War -- Religious aspects -- Christianity.

- Confederate States of America -- Religion.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- Religious aspects.

- 2000-04-05,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-09-29,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-09-29,

Fiona Mills

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-09-17,

Gretchen Fricke

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

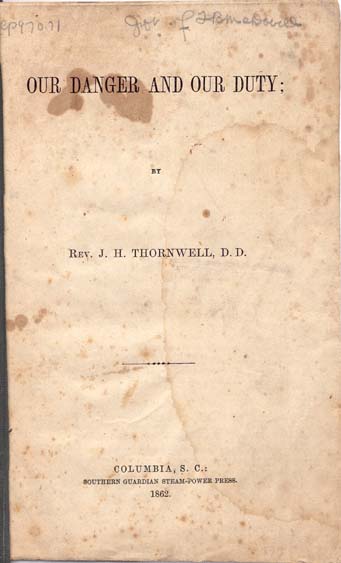

OUR DANGER AND OUR DUTY;

BY

REV. J. H. THORNWELL, D. D.

COLUMBIA, S. C.:

SOUTHERN GUARDIAN STEAM-POWER PRESS.

1862.

Page 3

OUR DANGER AND OUR DUTY.

The ravages of Louis XIV. in the beautiful valleys of the Rhine, about the close of the seventeenth century, may be taken as a specimen of the appalling desolation which is likely to overspread Confederate States, if the Northern army should succeed in its schemes of subjugation and of plunder. Europe was then outraged by atrocities inflicted by Christians upon Christians, more fierce and cruel than even Mahometans could have had the heart to perpetrate. Private dwellings were razed to the ground, fields laid waste, cities burnt, churches demolished, and the fruits of industry wantonly and ruthlessly destroyed. But three days of grace were allowed to the wretched inhabitants to flee their country, and in a short time, the historian tells us, "the roads and fields, which then lay deep in snow were blackened by innumerable multitudes of men, women, and children, flying from their homes. Many died of cold and hunger; but enough survived to fill the streets of all the cities of Europe with lean and squalid beggars, who had once been thriving farmers shopkeepers." And what have we to expect if our enemies prevail? Our homes, too, are to be pillaged, our cities our property confiscated, our true men hanged, and those who escape the gibbet, to be driven as vagabonds and wanderers in foreign climes. This beautiful country is to pass out of our hands. The boundaries which mark our States are, in some instances, to be effaced, and the States that remain are to be converted into subject provinces, governed by Northern rulers and by Northern laws. Our property is to be ruthlessly seized and turned over to mercenary strangers, in order to pay the enormous debt which our subjugation has cost. 0ur wives and daughters are to become the prey of brutal lust. The slave, too, will slowly pass away, as the red man did before him, under the protection of Northern philanthropy; and the whole country, now

Page 4

like the garden of Eden in beauty and fertility, will first be a blackened and smoking desert, and then the minister of Northern cupidity and avarice. Our history will be worse than that of Poland and Hungary. There is not a single redeeming feature in the picture of ruin which stares us in the face, if we permit ourselves to be conquered. It is a night of thick darkness that will settle upon us. Even sympathy, the last solace of the afflicted, will be denied to us. The civilized world will look coldly upon us, or even jeer us with the taunt that we have deservedly lost our own freedom in seeking to perpetuate the slavery of others. We shall perish under a cloud of reproach and of unjust suspicions, sedulously propagated by our enemies, which will be harder to bear than the loss of home and of goods. Such a fate never overtook any people before.

The case is as desperate with our enemies as with ourselves. They must succeed or perish. They must conquer us or be destroyed themselves. If they fail, national bankruptcy stares them in the face; divisions in their own ranks are inevitable, and their Government will fall to pieces under the weight of its own corruption. They know that they are a doomed people if they are defeated. Hence their madness. They must have our property to save them from insolvency. They must show that the Union cannot be dissolved, to save them from future secessions. The parties, therefore, in this conflict can make no compromises. It is a matter of life and death with both--a struggle in which their all is involved.

But the consequences of success on our part will be very different from the consequences of success on the part of the North. If they prevail, the whole character of the Government will be changed, and instead of a federal republic, the common agent of sovereign and independent States, we shall have a central despotism, with the notion of States forever abolished, deriving its powers from the will, and shaping its policy according to the wishes, of a numerical majority of the people; we shall have, in other words, a supreme, irresponsible democracy. The will of the North will stand for law. The Government does not now recognize itself as an ordinance of God, and when all the checks and balances of the Constitution are gone, we may easily figure to ourselves the career and the destiny of this godless monster of democratic absolutism. The progress of regulated liberty on this continent will be arrested, anarchy will soon succeed, and the end will be a military despotism, which preserves order by the sacrifice of

Page 5

the last vestige of liberty. We are fully persuaded that the triumph of the North in the present conflict will be as disastrous to the hopes of mankind as to our own fortunes. They are now fighting the battle of despotism. They have put their Constitution under their feet; they have annulled its most sacred provisions; and in defiance of its solemn guaranties they are now engaged, in the halls of Congress, in discussing and maturing bills which make Northern notions of necessity the paramount laws of the land. The avowed end of the present war is, to make the Government a government of force. It is to settle the principle, that whatever may be its corruptions and abuses, however unjust and tyrannical its legislation, there is no redress, except in vain petition or empty remonstrance. It was as a protest against this principle, which sweeps away the last security for liberty, that Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Missouri seceded, and if the Government should be reëstablished, it must be reëstablished with this feature of remorseless despotism firmly and indelibly fixed. The future fortunes of our children, and of this continent, would then be determined by a tyranny which has no parallel in history.

On the other hand, we are struggling for constitutional freedom. We are upholding the great principles which our fathers bequeathed us, and if we should succeed, and become, as we shall, the dominant nation of this continent, we shall perpetuate and diffuse the very liberty for which Washington bled, and which the heroes of the Revolution achieved. We are not revolutionists-- we are resisting revolution. We are upholding the true doctrines of the Federal Constitution. We are conservative. Our success is the triumph of all that has been considered established in the past. We can never become aggressive; we may absorb, but we can never invade for conquest, any neighboring State. The peace of the world is secured if our arms prevail. We shall have a Government that acknowledges God, that reverences right, and that makes law supreme. We are, therefore, fighting not for ourselves alone, but, when the struggle is rightly understood, for the salvation of this whole continent. It is a noble cause in which we are engaged. There is everything in it to rouse the heart and to nerve the arm of the freeman and the patriot; and though it may now seem to be under a cloud, it is too big with the future of our race to be suffered to fail. It cannot fail; it must not fail. Our people must not brook the infamy of betraying their sublime trust. This beautiful land we must never suffer to pass into the hands of strangers.

Page 6

Our fields, our homes, our firesides and sepulchres, our cities and temples, our wives and daughters, we must protect at every hazard. The glorious inheritance which our fathers left us we must never betray. The hopes with which they died, and which buoyed their spirits in the last conflict, of making their country a blessing to the world, we must not permit to be unrealized. We must seize the torch from their hands, and transmit it with increasing brightness to distant generations. The word failure must not be pronounced among us. It is not a thing to be dreamed of. We must settle it that we must succeed. We must not sit down to count chances. There is too much at stake to think of discussing probabilities--we must make success a certainty, and that, by the blessing of God, we can do. If we are prepared to do our duty, and our whole duty, we have nothing to fear. But what is our duty? This is a question which we must gravely consider. We shall briefly attempt to answer it.

In the first place, we must shake off all apathy, and become fully alive to the magnitude of the crisis. We must look the danger in the face, and comprehend the real grandeur of the issue. We shall not exert ourselves until we are sensible of the need of effort. As long as we cherish a vague hope that help may come from abroad, or that there is something in our past history, or the genius of our institutions, to protect us from overthrow, we are hugging a fatal delusion to our bosoms. This apathy was the ruin of Greece at the time of the Macedonian invasion. This was the spell which Demosthenes labored so earnestly to break. The Athenian was as devoted as ever to his native city and the free institutions he inherited from his fathers; but somehow or other he could not believe that his country could be conquered. He read its safety in its ancient glory. He felt that it had a prescriptive right to live. The great orator saw and lamented the error; he poured forth his eloquence to dissolve the charm; but the fatal hour had come, and the spirit of Greece could not be roused. There was no more real patriotism at the time of the second Persian invasion than in the age of Philip; but then there was no apathy, every man appreciated the danger; he saw the crash that was coming, and prepared himself to resist the blow. He knew that there was no safety except in courage and in desperate effort. Every man, too, felt identified with the State; a part of its weight rested on his shoulders. It was this sense of personal interest and personal responsibility--the profound conviction that every one had something to do,

Page 7

and that Greece expected him to do it--this was the public spirit which turned back the countless hordes of Xerxes, and saved Greece to liberty and man. This is the spirit which we must have, if we, too, would succeed. We must be brought to see that all, under God, depends on ourselves; and, looking away from all foreign alliances, we must make up our minds to fight desperately and fight long, if we would save the country from ruin, and ourselves from bondage. Every man should feel that he has an interest in the State, and that the State in a measure leans upon him; and he should rouse himself to efforts as bold and heroic as if all depended on his single right arm. Our courage should rise higher than the danger, and whatever may be the odds against us, we must solemnly resolve, by God's blessing, that we will not be conquered. When, with a full knowledge of the danger, we are brought to this point, we are in the way of deliverance, but until this point is reached, it is idle to count on success.

It is implied in the spirit which the times demand, that all private interests are sacrificed to the public good. The State becomes everything, and the individual nothing. It is no time to be casting about for expedients to enrich ourselves. The man who is now intent upon money, who turns public necessity and danger into means of speculation, would, if very shame did not rebuke him, and he were allowed to follow the natural bent of his heart, go upon the field of battle after an engagement and strip the lifeless bodies of his brave countrymen of the few spoils they carried into the fight. Such men, unfit for anything generous or noble themselves, like the hyena, can only suck the blood of the lion. It ought to be a reproach to any man, that he is growing rich while his country is bleeding at every pore. If we had a Themistocles among us, he would not scruple to charge the miser and extortioner with stealing the Gorgon's head; he would search their stuff, and if he could not find that, he would find what would answer his country's needs much more effectually. This spirit must be rebuked; every man must forget himself, and think only of the public good.

The spirit of faction is even more to be dreaded than the spirit of avarice and plunder. It is equally selfish, and is, besides, distracting and divisive. The man who now labors to weaken the hands of the Government, that he may seize the reins of authority, or cavils at public measures and policy, that he may rise to distinction and office, has all the selfishness of a miser, and all the baseness of a traitor. Our

Page 8

rulers are not infallible: but their errors are to be reviewed with candor, and their authority sustained with unanimity. Whatever has a tendency to destroy public confidence in their prudence, their wisdom, their energy, and their patriotism, undermines the security of our cause. We must not be divided and distracted among ourselves. Our rulers have great responsibilities; they need the support of the whole country; and nothing short of a patriotism which buries all private differences, which is ready for compromises and concessions, which can make charitable allowances for differences of opinion, and even for errors of judgment, can save us from the consequences of party and faction. We must be united. If our views are not carried out, let us sacrifice private opinion to public safety. In the great conflict with Persia, Athens yielded to Sparta, and acquiesced in plans she could not approve, for the sake of the public good. Nothing could be more dangerous now than scrambles for office and power, and collisions among the different departments of the Government. We must present a united front.

It is further important that every man should be ready to work. It is no time to play the gentleman; no time for dignified leisure. All cannot serve in the field; but all can do something to help forward the common cause. The young and the active, the stout and vigorous, should be prepared at a moment's warning for the ranks. The disposition should be one of eagerness to be employed; there should be no holding back, no counting the cost. The man who stands back from the ranks in these perilous times, because he is unwilling to serve his country as a private soldier, who loves his ease more than liberty, his luxuries more than his honor, that man is a dead fly in our precious ointment. In seasons of great calamity the ancient pagans were accustomed to appease the anger of their gods by human sacrifices; and if they had gone upon the principle of selecting those whose moral insignificance rendered them alike offensive to heaven and useless to earth, they would always have selected these drones, and loafers, and exquisites. A Christian nation cannot offer them in sacrifice, but public contempt should whip them from their lurking holes, and compel them to share the common danger. The community that will cherish such men without rebuke, brings down wrath upon it. They must be forced to be useful, to avert the judgments of God from the patrons of cowardice and meanness.

Page 9

Public spirit will not have reached the height which the exigency demands, until we shall have relinquished all fastidious notions of military etiquette, and have come to the point of expelling the enemy by any and every means that God has put in our power. We are not fighting for military glory; we are fighting for a home, and for a national existence. We are not aiming to display our skill in tactics and generalship; we are aiming to show ourselves a free people, worthy to possess and able to defend the institutions of our fathers. What signifies it to us how the foe is vanquished, provided it is done? Because we have not weapons of the most approved workmanship, are we to sit still and see our soil overrun, and our wives and children driven from their homes, while we have in our hands other weapons that can equally do the work of death? Are we to perish if we cannot conquer by the technical rules of scientific warfare? Are we to sacrifice our country to military punctilio? The thought is monstrous. We must be prepared to extemporize expedients. We must cease to be chary, either about our weapons or the means of using them. The end is to drive back our foes. If we cannot procure the best rifles, let us put up with the common guns of the country; if they cannot be had, with pikes, and axes, and tomahawks; anything that will do the work of death is an effective instrument in a brave man's hand. We should be ready for the regular battle or the partisan skirmish. If we are too weak to stand an engagement in the open field, we can waylay the foe, and harass and annoy him. We must prepare ourselves for a guerrilla war. The enemy must be conquered; and any method by which we can honorably do it must be resorted to. This is the kind of spirit which we want to see aroused among our people. With this spirit, they will never be subdued. If driven from the plains, they will retreat to the mountains; if beaten in the field, they will hide in swamps and marshes, and when their enemies are least expecting it, they will pounce down upon them in the dashing exploits of a Sumter, a Marion, and a Davie. It is only when we have reached this point that public spirit is commensurate with the danger.

In the second place, we must guard sacredly against cherishing a temper of presumptuous confidence. The cause is not ours, but God's; and if we measure its importance only by its accidental relation to ourselves, we may be suffered to perish for our pride. No nation ever yet achieved anything great that did not regard itself as the instrument

Page 10

of Providence. The only lasting inspiration of lofty patriotism and exalted courage is the inspiration of religion. The Greeks and Romans never ventured upon any important enterprise without consulting their gods. They felt that they were safe only as they were persuaded that they were in alliance with heaven. Man, though limited in space, limited in time, and limited in knowledge, is truly great, when he is linked to the Infinite as the means of accomplishing lasting ends. To be God's servant, that is his highest destiny, his sublimest calling. Nations are under the pupilage of Providence; they are in training themselves, that they may be the instruments of furthering the progress of the human race.

Polybius, the historian, traces the secret of Roman greatness to the profound sense of religion which constituted a striking feature of the national character. He calls it, expressly, the firmest pillar of the Roman State; and he does not hesitate to denounce, as enemies to public order and prosperity, those of his own contemporaries who sought to undermine the sacredness of these convictions. Even Napoleon sustained his vaulting ambition by a mysterious connection with the invisible world. He was a man of destiny. It is the relation to God, and His providential training of the race, that imparts true dignity to our struggle; and we must recognize ourselves as God's servants, working out His glorious ends, or we shall infallibly be left to stumble upon the dark mountains of error. Our trust in Him must be the real spring of our heroic resolution to conquer or to die. A sentiment of honor, a momentary enthusiasm, may prompt and sustain spasmodic exertions of an extraordinary character; but a steady valor, a self-denying patriotism, protracted patience, a readiness to do, and dare, and suffer, through a generation or an age, this comes only from a sublime faith in God. The worst symptom that any people can manifest, is that of pride. With nations, as with individuals, it goes before a fall. Let us guard against it. Let us rise to the true grandeur of our calling, and go forth as servants of the Most High, to execute His purposes. In this spirit we are safe. By this spirit our principles are ennobled, and our cause translated from earth to heaven. An overweening confidence in the righteousness of our cause, as if that alone were sufficient to insure our success, betrays gross inattention to the Divine dealings with communities and States. In the issue betwixt ourselves and our enemies, we may be free from blame; but there may be other respects in which we have provoked

Page 11

the judgments of Heaven, and there may be other grounds on which God has a controversy with us, and the swords of our enemies may be His chosen instruments to execute His wrath. He may first use them as a rod, and then punish them in other forms for their own iniquities. Hence, it behooves us not only to have a righteous cause, but to be a righteous people. We must abandon all our sins, and put ourselves heartily and in earnest on the side of Providence.

Hence, this dependence upon Providence carries with it the necessity of removing from the midst of us whatever is offensive to a holy God. If the Government is His ordinance, and the people His instruments, they must see to it that they serve Him with no unwashed or defiled hands. We must cultivate a high standard of public virtue. We must renounce all personal and selfish aims, and we must rebuke every custom or institution that tends to deprave the public morals. Virtue is power, and vice is weakness. The same Polybius, to whom we have already referred, traces the influence of the religious sentiment at Rome in producing faithful and incorruptible magistrates, who were strangers alike to bribery and favor in executing the laws and dispensing the trusts of the State, and that high tone of public faith which made an oath an absolute security for faithfulness. This stern simplicity of manners we must cherish, if we hope to succeed. Bribery, corruption, favoritism, electioneering, flattery, and every species of double-dealing; drunkenness, profaneness, debauchery, selfishness, avarice, and extortion; all base material ends must be banished by a stern integrity, if we would become the fit instruments of a holy Providence in a holy cause. Sin is a reproach to any people. It is weakness; it is sure, though it may be slow, decay. Faith in God-- that is the watchword of martyrs, whether in the cause of truth or of liberty. That alone ennobles and sanctifies.

"All other nations," except the French, as Burke has significantly remarked, in relation to the memorable revolution which was doomed to failure in consequence of this capital omission, "have begun the fabric of a new Government, or the reformation of an old, by establishing originally, or by enforcing with greater exactness, some rites or other of religion. All other people have laid the foundations of civil freedom in severer manners, and a system of a more austere and masculine morality." To absolve the State, which is the society of rights, from a strict responsibility to the Author and Source of justice and of law, is to destroy the firmest security of public order, to convert

Page 12

liberty into license, and to impregnate the very being of the commonwealth with the seeds of dissolution and decay. France failed, because France forgot God; and if we tread in the footsteps of that infatuated people, and treat with equal contempt the holiest instincts of our nature, we, too, may be abandoned to our folly, and become the hissing and the scorn of all the nations of the earth. "Be wise, now, therefore, O ye kings! be instructed, ye Judges of the earth. Kiss the Son, lest He be angry, and ye perish from the way, when His wrath is kindled but a little. Blessed are all they that put their trust in Him."

In the third place, let us endeavor rightly to interpret the reverses which have recently attended our arms. It is idle to make light of them. They are serious--they are disastrous. The whole end of Providence in any dispensation it were presumptuous for any one, independently of a special revelation, to venture to decipher. But there are tendencies which lie upon the surface, and these obvious tendencies are designed for our guidance and instruction. In the present case, we may humbly believe that one purpose aimed at has been to rebuke our confidence and our pride. We had begun to despise our enemy, and to prophecy safety without much hazard. We had laughed at his cowardice, and boasted of our superior prowess and skill. Is it strange that, while indulging such a temper, we ourselves should be made to turn our backs, and to become a jest to those whom we had jeered? We had grown licentious, intemperate, and profane; is it strange that, in the midst of our security, God should teach us that sin is a reproach to any people? Is it strange that He should remind us of the moral conditions upon which alone we are authorized to hope for success? The first lesson, therefore, is one of rebuke and repentance. It is a call to break off our sins by righteousness, and to turn our eyes to the real secret of national security and strength.

The second end may be one of trial. God has placed us in circumstances in which, if we show that we are equal to the emergency, all will acknowledge our right to the freedom which we have so signally vindicated. We have now the opportunity for great exploits. We can now demonstrate to the world what manner of spirit we are of. If our courage and faith rise superior to the danger, we shall not only succeed, but we shall succeed with a moral influence and character that shall render our success doubly valuable. Providence

Page 13

seems to be against us--disaster upon disaster has attended our arms--the enemy is in possession of three States, and beleaguers us in all our coasts. His resources and armaments are immense, and his energy and resolution desperate. His numbers are so much superior, that we are like a flock of kids before him. We have nothing to stand on but the eternal principles of truth and right, and the protection and alliance of a just God. Can we look the danger unflinchingly in the face, and calmly resolve to meet it and subdue it? Can we say, in reliance upon Providence, that, were his numbers and resources a thousand fold greater, the interests at stake are so momentous, that we will not be conquered? Do we feel the moral power of courage, of resolution, of heroic will, rising and swelling within us, until it towers above all the smoke and dust of the invasion? Then we are in a condition to do great deeds. We are in the condition of Greece when Xerxes hung upon the borders of Attica with an army of five millions that had never been conquered, and to which State after State of Northern Greece had yielded in its progress. Little Athens was the object of his vengeance. Leonidas had fallen--four days more would bring the destroyer to the walls of the devoted city. There the people were, a mere handful. Their first step had been to consult the gods, and the astounding reply which they received from Delphi would have driven any other people to despair. "Wretched men!" said the oracle, which they believed to be infallible, "why sit ye there? Quit your land and city, and flee afar! Head, body, feet, and hands are alike rotten; fire and sword, in the train of the Syrian chariot, shall overwhelm you; nor only your city, but other cities also as well as many even of the temples of the gods, which are now sweating and trembling with fear, and foreshadow, by drops of blood on their roofs, the hard calamities impending. Get ye away from the sanctuary, with your souls steeped in sorrow." We have had reverses, but no such oracle as this. It was afterwards modified so as to give a ray of hope, in an ambiguous allusion to wooden walls. But the soul of the Greek rose with the danger, and we have a succession of events, from the desertion of Athens to the final expulsion of the invader, which make that little spot of earth immortal. Let us imitate, in Christian faith, this sublime example. Let our spirit be loftier than that of the pagan Greek, and we can succeed in making every pass a Thermopylæ, every strait a Salamis, and every plain a Marathon. We can conquer, and we must. We must not suffer any other thought to

Page 14

enter our minds. If we are overrun, we can at least die; and if our enemies get possession of our land, we can leave it a howling desert. But, under God, we shall not fail. If we are true to Him, and true to ourselves, a glorious future is before us. We occupy a sublime position. The eyes of the world are upon us; we are a spectacle to God, to angels, and to men. Can our hearts grow faint, or our hands feeble, in a cause like this? The spirits of our fathers call to us from their graves. The heroes of other ages and other countries are beckoning us on to glory. Let us seize the opportunity, and make to ourselves an immortal name, while we redeem a land from bondage, and a continent from ruin.