Nellie Norton: or, Southern Slavery

and the Bible.

A Scriptural Refutation of

the Principal Arguments upon which the Abolitionists Rely.

A Vindication of

Southern Slavery from the Old and New Testaments:

Electronic Edition.

Warren, E. W. (Ebenezer W.), b. 1820

Funding from the Institute of Museum and Library

Services

supported the electronic publication of this

title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Jason Befort

Images scanned by

Jason Befort

Text encoded by

Christie Mawhinney and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2000

ca. 600K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) Nellie Norton: Or, Southern Slavery and the Bible. A

Scriptural

Refutation of the Principal Arguments upon which the Abolitionists Rely.

A Vindication of

Southern Slavery from the Old and New Testaments.

(spine) Nellie Norton

Rev. E. W. Warren.

208 p.

Macon, Ga.

Burke, Boykin & Company

1864

Call number 3113 Conf. (Rare Book Collection, University of North

Carolina

at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the

American South.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as

--

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and

Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- French

- Greek

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- Slavery -- United States.

- Slavery -- Justification.

- Slavery and the church.

- Slavery in the Bible.

Revision History:

- 2000-10-13,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-05-22,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-05-18,

Christie Mawhinney

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-04-29,

Jason Befort

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

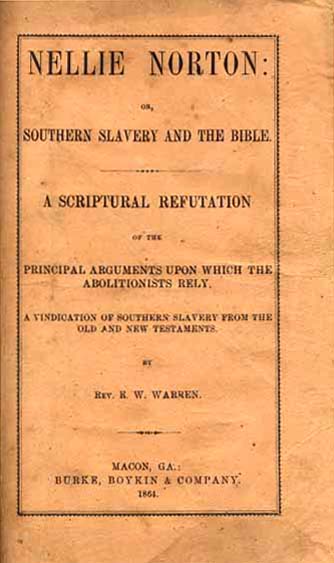

NELLIE NORTON:

OR,

SOUTHERN SLAVERY AND THE BIBLE.

A SCRIPTURAL REFUTATION

OF THE

PRINCIPAL ARGUMENTS UPON WHICH THE

ABOLITIONISTS RELY.

A VINDICATION OF SOUTHERN SLAVERY FROM THE

OLD AND NEW TESTAMENTS.

BY

REV. E. W. WARREN.

MACON, GA.:

BURKE, BOYKIN & COMPANY.

1864.

Page 2

PREFACE.

MANY books have been written in favor of slavery; but few of them have been generally read. This little volume claims no superiority over any of them. It was thought that a reply to abolition objections, based upon the Divine argument, might satisfy many minds who had not the time to devote to a thorough investigation of the subject, and, perhaps, set the question, as to its moral aspect, forever at rest.

It is presented in popular form, because that was thought to be the surest way to place the argument before the public mind. The author is deeply impressed with the fact that slavery is of God, and, desiring others to embrace the same truth, has here presented the scriptural arguments by means of which his own conclusions have been formed.

The author asks the indulgence of the critic into whose hands this little volume may fall. In the daily press of pastoral engagements, which were of paramount importance, he has given his weary evenings, when not otherwise occupied, to the composition of this book; and, therefore, he feels that it has many imperfections.

An humble volume, whose aim is the vindication of the Divine economy, and the establishment of Bible truth in the popular mind, and with the earnest prayer that the Author of all good, may bestow upon it[.] His blessing to the accomplishment of these ends, the work is sent forth with feelings of diffidence by

THE AUTHOR.

MACON, GA., MAY 4, 1864.COPYRIGHT SECURED.

Page 3

CHAPTER I.

Anxiety to see a Slave--The Welcome--Kindly Greetings--Family

Prayer--The Higher Law--Discussion.

"Mother do show me a slave as soon as the steamer gets near enough."

This request was made by a beautiful young lady, as she stood on the deck of a large steamer that was nearing the port of Savannah. It was her first trip South. The fulfillment of a promise of long standing, made to a dear uncle, that when her education was completed she would pay him a visit. He had left New England when quite young, and having married a Southern lady, seldom returned except on business, or to spend a few weeks with his aged parents.

In contemplating this visit there was but one thing that marred the anticipated pleasure of the mother and daughter, that was the idea of seeing the poor slave in chains, of listening to his groans of anguish, while they were powerless to free him from his bondage.

They had been led to regard as real, all the tales of woe, all the horrible tragedies, of which they had so often read in speeches, sermons, books or newspapers. They were sincere in believing slavery to be the "sum of all villanies;" and they had mutually agreed to give their influence to the cause of "human liberty, and equal rights," in other words, to abolitionism.

Fully expecting to see the negroes chained together and bearing heavy iron weights, the curiosity of Miss Nellie Norton was fully awake to catch the first glimpse of a slave.

The steamer having reached the wharf, the passengers came thronging to the shore, some after long absence eager to receive the affectionate greeting of their friends, some in search of pleasure, while others, with pallid cheeks and wasted forms, have come to seek new life and strength from the balmy breezes of a more Southern clime.

"And sure enough you've come, sister; welcome to our Southern soil and home. I am so happy to see you." Mrs. Norton threw her arms around the neck of her brother, and for a moment both shed tears of joy at meeting again after so long an absence. "And Nellie, dear Nellie, is this you! Surely this is not my little Nellie

Page 4

whom I last saw eight years ago in New England! Why how you have grown! No, this is my niece, Miss Norton. Come let me seat you in my carriage, then I will see to your baggage."

As Mr. Thompson led the way to the carriage, Nellie, still on the qui vive to see a slave, could not longer restrain her curiosity.

"Uncle, do show me a slave if there is one here."

"Jack, come here," cried Mr. T. The carriage driver promptly obeyed his master's call, advancing with hat in hand. Jack was a fine looking mulatto, neatly dressed in a suit of broad cloth, his hat being tidily bound with crape. "Here is a slave, Nellie," said Mr. T.

"Oh no, uncle, you jest, do you not? That cannot be a slave. I thought you Southerners kept your slaves chained lest they should run away from you."

"Pshaw, Nellie, you have certainly been to Brooklyn and heard that villainous hypocrite Henry Ward Beecher. But here we are at the carriage. Jack remain here until I go and have the baggage put in the wagon."

"Yes, sir," said Jack with a quick and emphatic voice.

The ladies being seated, concluded that while they were waiting they would begin to acquaint themselves with slavery by obtaining information from one of the sufferers. Nellie, who felt her superiority as an educated young lady, over the ignorant people of the South, as she imagined them to be, began the conversation with Jack, the negro carriage driver.

Hesitating for a moment as to whether she should address him as Mr. or Sir, as a free man or as a servant, she finally began without either. "Are you in my Uncle's service?"

"Yes'm, I b'longs to mas' George."

"How do you like him?"

"I likes him fust rate; "he's mighty good to us, feeds us well, gives us plenty of close and is good all de time."

"But, would you not rather be free, as we are, so that you could go where you please, and when you please?"

"Don't know, Missus, color'd folks han't got white folk's ways, no how; we wouldn't know how to 'have ourselves; we too ignunt."

"Suppose I were to buy you and carry you home with me, and set you free, so that you could work for yourself and have everything you made, would you like that?"

"Ef you'd carry mas' George and miss Penny and the child'ens wid you, and let me stay with dem, not 'thout."

Page 5

"Why would you rather live with Uncle and be a slave than to go with me and be free?"

"I couldn't quit mas' George, no how; he's mighty good man, and den Miss Penny she's monstrous kind, and when we get sick she 'tends to us and nusses us so good, and gives us such nice fixin's to eat, and has us 'tended to mighty kind."

"What a stupid dolt," said Nellie, softly to her mother. "Poor fellow he loves his chains."

Mr. Thompson having arranged the baggage, came and took his seat in the carriage with his sister and niece. Jack was ordered to drive forward, and while they were going to Mr. T's residence they conversed on family matters, Southern scenery, society, &c.

After a ride of several hours, they approached the elegant home of their relative. The house stood on a slight elevation, surrounded by exquisite shrubbery, tastefully arranged and trimmed, while at the distance of a few hundred yards could be seen two rows of neatly painted negro cabins.

Mrs. Thompson, meeting them at the gate with the true grace and cordial affection of a cultivated Southern lady, extended to them a most hearty welcome. The children, too, of whom there were five, were all eager to see cousin Nellie and aunt Julia, of whose coming they had heard so much. They were each embraced in turn, and seemed delighted to see their Northern relatives.

They entered the richly furnished dwelling just as the sun sank to his evening repose, charming the visitors with his gorgeous coloring of the Western sky. After arranging their toilet, the ladies were invited in to tea. Having spent some time in social conversation around the table, all were assembled for family prayer. At the sound of a bell the house servants came in and seated themselves near the door. One of them handed Mr. Thompson a Testament from which he read a chapter, occasionally stopping to make explanations. When the chapter was finished, they all knelt and he prayed, while an occasional response in the way of an audible groan proceeded from some of his colored auditors. This was an unusual scene to the new comers, who were totally ignorant of Southern life and negro character, no remarks, however, were made, for they feared to speak, lest they might wound the feelings of their deluded relatives, who ignorantly imagined it was right to hold human beings in slavery.

"Well, Nellie, you have now seen several of my slaves, what do

Page 6

you think of them and slavery?" said Mr. Thompson, after they were all seated in the parlor.

"Do you ask me for the truth, uncle?"

"Certainly I do, my dear, I would not have you speak an untruth."

"I think well of your slaves, as you are pleased to term them, but I abominate the laws and public sentiment which doom them to a life of servitude."

"Then, my dear niece, you abominate the law of God, and the sentiments inculcated by his holy prophets and apostles. I do not feel reproached by your remark, but I would kindly suggest the propriety of an investigation from the Bible, of the origin and perpetuity of slavery, at some convenient time while you are here."

"Uncle, slavery shocks humanity how could it then be taught by the Divine Being? I cannot believe it, and if I did, I do not think I could confide in the justice and goodness of such a Being."

"Why, Nellie, you shock me, if God is not such a one as you would have Him to be, you will not worship Him. If he does not come up to your standard of what he ought to be; if He dares to teach what does not accord with your views, then you reject Him. Consider, my dear niece, of what presumption you are guilty."

"But, uncle, there is a law of the human mind higher than all other laws, having its own intuitive perceptions of what is right and wrong: this law of the mind is above all other laws, and is at liberty to accept or reject any proposition, as it may accord with or differ from this intuitive moral consciousness. Slavery comes in direct antagonism with this law of my mind, and hence I reject either the interpretation or the authority of any and every standard which favors slavery."

"These 'laws of the human mind,' these 'intuitive perceptions,' this 'moral consciousness,' were given you by your gracious Creator. Then they are creatures of His. Now shall the Creator become subordinate to the creature? 'Shall the thing formed, say to Him who formed it, Why hast thou made me thus?' But from what did you learn your ethics, or metaphysics, or rather infidelity, I ought to call it, for it is really worse than the system either of Paine, or Hume? I am more and more astonished at you. I was not aware that abolitionism had resorted to such desperate ends to sustain itself. I knew that Theodore Parker had rejected the Bible because it was a pro-slavery book, but I did not knew that the sentiment had taken possession of the pulpit, the press and the schools, so thoroughly that a girl just from her alma mater should be so well

Page 7

versed in the whole argument. But I did know that this would be the last and only successful point from which abolitionism could be defended. The North must give up the Bible and religion, or adopt our views of slavery."

"Not so fast, uncle, I have not admitted that the Bible is a pro-slavery book, nor do I believe it. Upon the contrary, I have been taught to believe in its Divine origin, to reverence its holy truths, and to obey its heavenly precepts. I only said what would be the case in the event it did teach slavery."

"I am glad, dear Nellie, you have been so piously taught; I only regret that this religious education has taken such slight hold upon your reverence; for with your firm belief in the Divine origin of the Bible, you reverence the higher law more than you do its heavenly instructions. You will believe the Bible is from God, a holy book, worthy of the heart obedience of all, unless it teaches slavery, in which event it is 'sans Dieu.' Well, I see you are afraid of the Bible, the only revelation from heaven, the only sure unerring source of information. So you must be left to 'the law in your members which wars against the law of your mind, and brings you into captivity to the law of sin.'"

"No, uncle, I am not afraid of the Bible, nor do I fear to investigate the subject of slavery as revealed in it, I am only surprised that you should have been so deluded as to believe the institution can find any favor with a holy God. I am willing at any time to begin the investigation with you."

"Very well, then, the arrangement is understood. When you have had sufficient time to rest, and look a little at slavery a little in its practical workings, say one week from the present time, our investigation shall begin."

The remainder of the evening was spent most pleasantly in conversation upon other matters, and at a late hour all retired.

The succeeding week passed most agreeably to all the members of the household.

The flowers and shrubbery, of which there was a great variety, covered a large and beautiful plat of ground in front of the house. Thither Nellie resorted some portion of every day, with her young cousins, and delighted them no little with her analysis of many of the flowers. Several times during the week she strolled down to the negro cabins, with one of her little cousins. She desired to look into the treatment of her uncle's slaves, and read, if possible, in their faces, and hear from their half concealed expressions, which

Page 8

she supposed would almost involuntarily escape from their lips, the evidence of their misery occasioned by the bondage. At every visit her surprise was increased, to find them so entirely free from all care, and manifesting so contented, cheerful and happy a spirit.

THE DISCUSSION.

Agreeably to the understanding of the week before, the family assembled in the parlor after tea, with a view to the anticipated discussion. The two elder ladies being seated on the sofa, Mr. T. invited his niece to draw near the centre table, upon which lay a large Bible. Taking in his hand a concordance, for more convenient reference to any text bearing upon the subject, he seated himself opposite to her. Both of them felt confident of being able to maintain the positions which they were about to assume. Nellie was but little versed in the teaching of the Bible, but she had selected from her uncle's library "Wayland's Moral Science," and that was as good authority as she wanted. Dr. Wayland was a wise and learned man; too much so, in her opinion, to make a mistake, and too good to misrepresent the doctrines of the Bible. She was familiar with his opinions on this subject, for they had been taught her with great care.

Mr. Thompson had come South with the usual prejudices against slavery which Northern birth and education instil. He had not consented to become the owner of slaves from mercenary motives. At first his conscience forbade the idea of holding a fellow being in servitude, and he did not do so until as a conscientious seeker after truth, he had carefully investigated the subject from the Scriptures. He was therefore familiar with the subject in all its bearings.

"'The Bible is the sufficient rule of faith and practice,' was a dogma taught by the great reformer, Martin Luther, and one to which all protestants have given their most hearty assent," said Mr. Thompson, as he took the Bible into his hands and opened it without reference to book or chapter. As he did so he kept his eyes on Nellie all the time, to catch, if possible, her expression of assent to this truth. But she had carefully guarded herself against any admission which might be afterwards used to her disadvantage in the argument. She felt herself to be the representative of abolitionism, and she was determined it should not suffer on account of the unwariness of its advocate--the ground must be maintained, the point carried at all hazards. So she was silent.

"Hear, O Heavens, give ear, O Earth, for it is the Lord that

Page 9

speaketh." This quotation was made by Mr. T. with solemn emphasis, then turning to Genesis ix: 25, he read, "Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren, and he said Blessed be the Lord God of Shem, and Canaan shall be his servant. God shall enlarge Japhet and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem: and Canaan shall be his servant." Here, Nellie, is the origin of slavery, it comes directly from God through His servant, Noah."

"Excuse me uncle, for the comparison, I intend no personal disrespect to you, but you really remind me of Rip Van Winkle searching for the flag of George the III, after the Independence of the American Colonies was gained, and acknowledged by Great Britain. To go back to the flood, an old man just aroused from the stupor of drunkenness, in order to justify American, or I should say, Southern slavery. Let the odium rest upon those who foster the wicked institution. Really, uncle, you must be hard pressed for a scriptural argument."

"You speak lightly of the 'preacher of righteousness,' as Noah is called in the sacred word. He alone was found worthy of deliverance from the deluge, and to become the second father of the human family, from whom descended the Son of God, the world's Redeemer. It is written, 'Honor thy father.' But to the argument. I thought you were too well versed in logic to object to tracing effects back to their causes; and that you were too fond of looking through a subject, to be desirous of commencing short of the beginning, or to stop short of the ending. My purpose is, according to the agreement, to investigate the subject as taught in the Bible. I am beginning at the fountain, and shall trace the stream through all its meanderings, showing its origin, regulation and perpetuity."

"Do not be on the opposite extreme of Rip Van Winkle, and run too fast to read, nor despise things because they are old."

"Truth loses none of its value by age, nor is error entitled to respect on account of its later origin. If you will not accept the Bible as authority, why the discussion is at an end!"

"Oh! no uncle, proceed. I only objected to your going back so far to vindicate slavery in its present revolting aspect."

"And I only went back to show that this revolting institution, as you are pleased to call it, was ordained by God, and was therefore right, for God can do no wrong."

"I remember," said Nellie, "to have heard one of our preachers giving an account of slavery, and I think it was from the Scripture

Page 10

you have just read. He said the poor Israelite who became hopelessly indebted, was sold, that the debt might be paid; but at the end of seven yaars he was by law released. So I don't think you will prove perpetual servitude from this law."

"Your preacher thought this poor Israelite descended from Canaan, did he? It might be well for him to study genealogy. There is a law regulating the slavery of the poor Hebrews, found in Exodus xxi: 2-6, 'If thou buy an Hebrew servant, six years he shall serve, and in the seventh he shall go out free for nothing. If he came in by himself he shall go out by himself: if he were married then his wife shall go out with him. If his master have given him a wife, and she have borne him sons or daughters; the wife and her children shall be her masters', and he shall go out by himself. And if the servant plainly say, 'I love my master, my wife and my children, I will not go out free, then his master shall bring him unto the door, or unto the door post: and his master shall bore his ear through with an awl, and he shall serve him forever.' This law is also repeated in Deut. xv: 16, 17. The law here enacted was a necessity growing out of the nature of things. I mean, the organization of human society, and the dependences of the poor classes upon the rich. This form of slavery exists to a greater or less extent in all countries, where African slavery does not. At the North, you make slaves of the poor people, instead of supporting them voluntarily, as we do. You enslave your unfortunate kindred who become dependent upon you for support. The truth is, the world never has, and never can exist without slavery in some form. T. R. R. Cobb, an able writer on this subject says: 'In every organized community there must be a laboring class to execute the plans devised by wiser heads; to till the ground, and to perform the menial offices necessarily connected with social life.' It therefore follows, as a consequence, that where negro slavery does not exist, the rich will enslave the poor of their own race.

"The curse pronounced by God, through Noah, upon Ham and his descendants, is subject to no such restrictions and limitations as governed enslaved Hebrews. It was to extend from generation to generation, to be perpetual. Hence you see Abraham 'the father of the faithful, the friend of God,' was the owner of a large number of slaves. Some were 'born in his house,' and some were 'bought with his money.' So it is evident that slavery was common in those days; and the domestic slave trade, so much abhorred by the abolitionists, and which affords themes of such bitter denunciations against the South, was also practised, even by the very best men.

Page 11

"Abraham trafficked in human flesh, when he bought servants with his money."

"My dear uncle, you shock me, you horrify me, when you say that Abraham, 'in whom all the families of the earth were to be blest,' bought human beings for the purpose of enslaving them. Surely this cannot be true; but, if it is, I apprehend, the reason is to be found in the fact, that in the dark age in which Abraham lived, the people were not civilized and enlightened as they are now. They saw through a glass darkly, that was but the misty twilight of our day."

"But Nelly, it was so ordained of God, and He was not less wise and good then than now. The advancement of the world has not enlightened the mind, nor refined the sensibilities of deity. I think your sensibilities are morbid, when they revolt at that which God has done. Your sympathy for the slave is, I fear, quite above your reverence for Deity. Be careful, lest in avoiding Scylla you are wrecked in Charybdis."

"As much as I love you, my dearest uncle, and much as I confide in your honesty and intelligence, you must excuse me for not taking your ipse dixit as to the perpetuity of slavery. That Abraham bought and held them is certainly true, and that Canaan was to be a 'servant of servants,' and was to serve his brethren, is also true; but it does not therefore follow that the institution was to be perpetual. I cannot believe it. I do not wish to believe it."

Nellie's cheek flushed, and she grew animated as she emphasized the closing sentence: "Your proofs are insufficient; they want point and force. Your quotation is irrelevant; the phrase 'servant of servants,' does not mean perpetual servitude," she replied.

"Then," continued her uncle, "they shall be strong enough for you, if you will take divine testimony. Will you be kind enough to open the Bible and read Leviticus xxv: 44-46?"

Nellie took the Bible and opening to the chapter and verses, reluctantly read:

"Both thy bondmen and thy bondmaids which thou shalt have, shalt be of the heathen that are round about you; of them shall ye buy bondmen and bondmaids. Moreover, of the children of the strangers that do sojourn among you, of them shall ye buy, and of their families that are with you, which they begat in your land, and they shall be your possession. And ye shall take them as an inheritance for your children after you, to inherit them after you; they shall be your bondmen forever. But over your brethren, the

Page 12

children of Israel, ye shall not rule one over another with rigor." Nellie closed the book and sat silently, while a shade of discontent rested upon her usually bright face. She felt no disposition to speak, for she knew not what to say, and yet silence was painful, for her uncle might construe it into acquiescence. Her suspense was short, however, for the mother and aunt, at the other side of the room, had found it most difficult to interest themselves, so as to forget what was going on, and had therefore by tacit consent, suspended their conversation in order to hear Nellie read what the Lord had said by Moses, on the perpetuity of slavery; and seeing her embarrassment her aunt broke the silence. "I think your discussion had better be suspended for the present; we will grant, if you ask it, that you are both erudite and intellectual; can you not give us some proof of your superior social powers? Don't you think you can afford to play the agreeable for the balance of the evening?"

"Then in one minute we will join you," said Mr. T., and turning to Nellie, he said, "As we will not have another opportunity for several evenings, to converse on this subject again, I wish to mention a few of the points contained in the quotation you have just read, that you may consider them at your leisure.

1st. It establishes the domestic slave trade: 'ye shall buy bondmen and bondmaids.' 2d. They were permitted to buy children from their parents: 'Of the children of the strangers that do sojourn among you, of them shall ye buy.' 3d. They were the property, or chattel, of the owner: 'And they shall be your possession.' 4th. There was no limit to their servitude, it was to be made perpetual: 'An inheritance for your children, your bondman forever.' Here you have divine proof that a holy and just God did perpetuate slavery.

"To-morrow evening my young friend and neighbor, Mr. Mortimer, is to pay you a visit; on the next, Saturday evening, Jacob and Phebe are to be married, and on Sabbath afternoon it is our custom to attend the religious services of the colored people. In the mean time you may be able to give a few leisure hours to considering the subject of this evening's conversation and see what the 'law and the testimony' say."

Nellie's mind was not at rest. The Bible certainly did teach that slavery was a perpetual institution. Its chains were forged in heaven, by God himself, and so fastened, that no power could sunder them but His. Here were the words, she had read them herself, she could not be mistaken; and yet she had repeatedly heard the

Page 13

contrary asserted, by ministers in whom she had the utmost confidence. Her Sabbath School teachers had taught her that slavery was inhuman, iniquitous, the sum of all villainies, that there was no authority whatever for it in the word of God, that Southern cupidity had forged its chains, and Northern philanthropy must break them; that it was the peculiar mission of the more enlighted and christianized people of the North to 'break every yoke' and set every bondman free, and with these sentiments even the great Dr. Wayland certainly agreed. "How can it be? certainly the Bible is not a pro-slavery book. Surely! God is not a pro-slavery God. Impossible!! but here is His word. If it should be true, (and how am I to doubt it? have I not been taught to believe, to reverence, to obey it?) what am I to do? Give into the idea of slavery? Never, never. But can I give up my God and my Bible? Never, no NEVER--perish the thought. O God help me, for I know not what to do. O God, I cleave to thee! 'Let God be true, but every man a liar.'"

Poor Nellie, there was an invisible struggle going on, of which none dreamed but herself. All her efforts to dispel her troubles and engage pleasantly in the conversation were fruitless. She finally arose, and bidding them good night retired to her room, not however to sleep, but to wrestle in agony as to whether she should cling to the prejudices of her early education and still advocate abolitionism, and in that event to reject the Bible as a revelation from God; or in humble confidence in the justice and immutable righteousness of its great author, accept the Bible with all its teachings. Finally she caught the idea, that Southern slavery could not be defended from the sacred volume, and laying the flattering unction to her heart, quieted her nerves and fell asleep.

Page 14

CHAPTER II.

Visit of Mr. Mortimer--Negro Wedding--Sabbath School--Prayer

Meeting.

Nellie did not awake the next morning till the sun had ascended high up into the heavens, and covered the earth with his golden light.

Amy, the chamber maid, had the room well warmed, and had been long waiting impatiently for the young sleeper to awake.

"Missus, time to git up, breafus' ready, been waiten long time for you."

Nellie opened her eyes upon the Ethiopian maid, and beholding her bright countenance, her smiling face and ivory teeth, was reminded of the fact that she was in the land of slavery. When she stepped upon the thick warm carpet and advanced to the fire, and gazed around upon the many comforts that met her view, and became cognizant of the dusky Amy's attentions, having, for their object, her comfort, her convictions of Southern life and manners were materially modified. She had not yet discovered that blight she expected to behold imprinted by slavery upon everything, animate and inanimate, on manners, customs and habits. She had expected to see a cold remorseless tyranny, a grinding aristocracy; and a dumb, despairing, revengeful slave population. She had expected proud hauteur, overbearing and heartless despotism on the one hand, and cringing servility, composed of hopeless fear and smothered wrath, on the other. She had expected to see moss-grown decay, and evidences of an effeminate civilization, instead of warm, genial comfort, general satisfaction and happiness, and universal signs of confidence, love and prosperity.

Nellie had been accustomed to wait entirely on herself at home. Here she finds a chair placed by the fire for her, polite hands warm her shoes and stockings and hand them to her. Her garments are likewise warmed and handed to her. Nimble fingers aid in adjusting her attire, the water is poured into the bowl for her, and a towel is extended to her, and when the last touch of arrangement has been given to her hair, skilful hands slip her morning dress over her head, and with a few expert manipulations, complete her attire, and leave her ready to descend to the breakfast table.

"You looks, mighty nice dis mornin' Miss, I bound Mas' George 'praise you, and think you mighty sweet when he sees you. Dis dress mighty purty, I 'specks you gib it to me when you go home.

Page 15

Gwine to have big weddin' to-morrow night ma'am, Misses been busy 'bout it all de mornin'. Jacob and Phebe gwine to marry, and uncle Jesse gwine to 'form de sarimony, and me and Elsey gwine to be de tendunts wid Sam and Guss," &c. Thus the jubilant girl ran on in a strain of intelligence to the surprise and pleasure of Nellie, till she descended to the dining room.

"Her world was ever joyous--

She thought of grief and pain

As giants in the olden time,

That ne'er would come again."

After breakfast, Nellie and her young cousin, Alice Thompson, walked to the front porch. The day was one of those rich, hazy autumnal days, all flooded with glorious sunshine, and mellowed by a soft Southern breeze so common to our Southern climate. They then walked to the back door, and gazed for a while on the magnificent live oaks, and majestic magnolias, that shaded the back yard.

On all sides, elegance, comfort and plenty were visible, accompanied with contentment, peace and happiness. Nellie's eye, with a delight bordering on rapture, took in the glories of the whole scene: its fields, its fences, its trees, its shrubs, its houses, its gardens, its evidences of solid prosperity and comfort; and she mentally contrasted it with her own prim, precise, economical home. She contrasted the cold calculating manners of the North, with the open, warm, genial habits of the South. She arrayed the hired indifferent services of "white helps," with their frequent "warnings," with the confiding filial obedience of Southern slaves, jumping with a smile to perform a behest. She could not help comparing the cold, selfish relations existing between mistress and servant in New England, and the open, warm, friendly, confiding feeling manifested between the slaves and their owners. Here was a master and mistress engaged in preparations at considerable trouble and expense, to furnish a sumptuous supper and appropriate dressing to gratify two slaves who were going to be married. Nellie was surprised, but could not be blind to these things.

She and Alice took a walk among the negro cabins, and the ebony damsels crowded around and followed them with the greatest glee imaginable, now and then one venturing a remark at which all the rest would giggle immoderately; and when Nellie thought proper to engage in some slight badinage, the universal merriment seemed to reach its utmost hight. Nellie had never seen such merry servants.

Page 16

Not one seemed borne down with that mighty incubus of care and oppression she had expected; but decked out in bright colors, and new shoes, and flaming "head handkerchers," they followed her as entirely free from care and liberty-longing as school children upon any academy lawn.

"You Jim! aint you comin' along wid dem chips?" Thus resounded from the vicinage of her huge pot, the voice of "Aunt Fanny." It was "Aunt Fanny's" business to cook for the "chilern," and take care of them, the latter she did most effectually by ruling them with a rod of birch. Her large pot is filled with meat, greens and "dumplings," and the "taters" are wrapped in the ashes. When at twelve o'clock, all are ready, she deals out to all according to her "resarved rights," that is to say, she has a half dozen or more large trays and basins, filled with the contents of the pot, around which gather from three to five of the little Africans, and seating themselves, eat till they are all satisfied.

"You, Jim," says Aunt Fanny, as she saw Nellie approaching, "aint you comin' long wid dem chips? I see you foolin' long dar, sir, never mind, I whip you for dat sho's you born; you see if I don't now." While "Aunt Fanny" is very good naturedly explaining to Nellie how she cooks for and takes care of "de chilern," and was very proud of being so honored by the attention of "young miss," Jim approaches the pot with his basket of chips, wholly unobserved by "Aunt Fanny," whose kind heart has already forgotten the threat, and getting on his knees, throws the chips somewhere near about the fire, while he gazes all the time, with open mouth, into the face of Nellie.

Twenty or thirty little darkies gather around her, all fat and saucy, jolly and lively, and not in the least disconcerted, they gaze into her face, and laugh and stare, with the whites of their eyes upturned and their mouths spread from--side to side.

"Do they get enough to eat, aunty?"

"God bless your soul, chile, plenty; I stuffs 'em, see how fat dey is."

"Where do you get the food?"

"I gits it from de smoke-house every mornin'. Boss weighs it out, and I biles de middlin', and greens and dumplins for 'em in de pot, an cooks de taters in de ashes. Plenty, dey gets nuff, sho."

Thus pleasantly and swiftly the time glided away with Nellie. Late in the afternoon Mr. Mortimer came over to take tea and make the acquaintance of Mrs. Norton and her daughter. He was

Page 17

the friend and neighbor, and intimate associate of Mr. Thompson, and was always a welcome guest in his family. He was of medium height, and very graceful, with an intellectual cast of features. He was intelligent and agreeable, commanding fine conversational powers, and a high-toned gentleman of unexceptional moral character. The elegance, courteousness and affability displayed by Mr. M. during the evening, made time pass in the family circle with unwonted celerity, and all seemed disappointed when the hour of eleven arrived and their young friend took his leave.

After his departure no remarks were made as to the young visitor. Mr. and Mrs. T. waited for their relatives to say how they were pleased, and Mrs. Norton waited for Nellie; she from choice, or design, was silent. To tell the whole truth, she was very favorably impressed, but would not commit herself till a better and more thorough acquaintance with his true character. "Make haste to be slow in forming your opinion of young men," was her father's favorite proverb, and she believed it was correct and acted upon it.

Saturday, the wedding day, dawned upon the world in cloudless glory. It was a jubilant holiday for all the servants on the plantation of Mr. Thompson.

The bride-groom expectant was Jacob, now foreman of the plantation. He had been promoted to the important post of "driver" for his fidelity and honesty. He was about twenty-five, of a yellow complexion, and as dashing and good humored a fellow as you find in a day's drive. He devotedly loved his master and mistress, and would have died for Miss Alice. Phebe was about twenty-six, and was Mrs. T.'s house-maid, a quiet, respectful woman, who knew her duty and always did it well. Her complexion was dark.

They were about to consummate a long cherished attachment, and both the master and mistress thought fit to grace the occasion with their presence, and invited their guests also to enjoy this, to them, novel scene.

Mr. Mortimer, having come over by special invitation, joined the party, who proceeded to the neat double cabin whose larger room had been cleanly swept and neatly arranged, and on whose wide hearth a bright fire was blazing.

Negro weddings are more stately and solemn than one would naturally suppose. Negroes are impressible creatures, and are easily affected by aught of the august.

The whites stopped in front of the door, rather than crowd through

Page 18

the anxious mass of lookers-on, but they enjoyed a tolerable view, and heard all that was said.

The door of the little room was thrown open, and one couple elegantly dressed, entered, ranging themselves on the right; then another couple, ranging themselves towards the left; these were followed by Jacob and Phebe. Each female attendant wore a white muslin dress, with white flowers in their hair, all tidily arranged by Mrs. Thompson, Alice and Nellie. Each male was dressed in broadcloth, with shining boots, ruffled shirts, standing collars and white gloves, with their pocket handkerchiefs but half concealed in their breast pockets. Phebe was tastefully dressed in white, with slippers and a long white veil; altogether she presented an elegant appearance. Jacob was done up in a new suit of broad cloth, a present, for the occasion from his master; he wore a white vest, gloves and cravat, and with a fair personal appearance, was the ne plus ultra of negro elegance.

Not a sound was heard, all were silent and still as the grave. "Uncle Jesse" advanced, with book in hand; there was a solemnity of appearance about his face and demeanor highly instructive and impressive. After a moment's pause, to collect his thoughts and appear dignified, he began:

"God made Adam fust, be staid long time in the garden 'thout a wife, but he wan't satisfied and happy, though he have every other thing he want. Then God say, it no good for the man that he be alone, I make a help meet for him, to comfort him in sickness and nus him in trouble, and to talk to him when he lonesome. So God make Eve outen Adam's rib, and say, she bone of your bone and flesh of your flesh, and for this cause a man shall quit he father and mother, and stay with his wife. Any body present got any objections to this lady and gentleman bein' married into holy matrimony, so they now make it known or hold their peace forevermore. Once, twice, thrice--no objection.

"Jacob, take Phebe by the hand. Do you brother Jacob take Phebe to be your lovin' and true wife? Will you love her like Abraham loved Sarah, treat her kind like Isaac did Rebecca, be faithful to her like Zacharias was to Elizabeth, and not cleave to no other woman but her, till she die--do you?" A graceful bow and a scrape of the foot, was the affirmative response.

"Do you, sister Phebe, take brother Jacob to be your lone husband. To honor him as Sarah did Abraham, and obey him as Rebecca did Isaac, and nus him, and comfort him as Elizabeth did

Page 19

Zacharias, and always cleave to no other man till be dead--do you?" A quick courtesy was the response. "Then I pronounce you husband and wife, with the blessing of God to live together forever. Amen."

Great confusion followed as each one pressed forward to wish the newly married couple "much joy." Many efforts at wit were made, and a general scene of hilarity ensued, which was kept up till supper was announced. The repast was not less sumptuous than elegant. The "bride's cake" was exquisitely beautiful.

"Uncle Jssse" asked a blessing at the table, at the conclusion of which each bowed his head and scraped his foot. It was interesting to see the young "gen'men," waiting on the "ladies," as they handed round the table first one dish and then another.

But the scene after supper, far surpassed anything which had preceded it. The "playing songs," and kissing, the joyous peels of laughter, the continuous gleeful mirth, the "uproarious" outbursts of merriment, beggar all description, I therefore lay down my pen, and leave the reader to imagine, what must have been the impressions on the mind of Miss Nellie Norton, just from New England.

If you have never witnessed one of these scenes, be assured, kind reader, it is good for dyspepsia, a certain cure for the "blues," and will make a preacher laugh.

But we leave the negroes to play and sing what they please, and as long as they please, to fiddle, "pat Juba," and dance and have a merry time generally, if they like. The hour is late and we must prepare for the Sabbath, when we are again to meet some of these happy Ethiopians, but under different circumstances.

On arriving at the house, Mr. Thompson opened his mail, which pressing engagements since its arrival at sun down, had prevented.

"A letter for Nellie," he exclaimed. She came bounding to his side, and opened and read with great eagerness, the following note:

PULASKI HOUSE, Sav., Nov. 23d, 18--.

Miss Nellie Norton: Dear Young Friend--You will doubtless be surprised to receive this from me, bearing date at this place. My health suddenly failed, my symptoms became alarming, and my physicians recommended a trip South, to which my parishioners generously consented.

It would afford me pleasure to come out and spend a few days with you and your good mother, which I contemplate doing at my earliest convenience.

What a beautiful land is this, how sweet its breezes, how balmy its

Page 20

air. What a paradise it would be but for the curse of slavery[.] But O the groaning of the oppressed! May the time be hastened when every yoke shall be broken.

In haste, Your affectionate Pastor,

DANIEL B. PRATT.

"O Mother, it's from Mr. Pratt, and be is in Savannah, come because his health failed, and wants to come out and see us. Uncle, can't you send for him in the morning, and let him come out to-morrow?"

"Shall I send for him on Sabbath, Nellie?"

"O yes, uncle, it's no harm under the circumstances to send for a poor sick preacher to get out and enjoy a little fresh country air, is it?"

"Well, just as you say. I don't think you would survive till Monday, so I will have the carriage off early. Write him a note, that we will expect him early to dinner; a cold dinner, enjoyed by warm hearted friends." Nellie tripped away to pen the note, while Mr. Thompson went to inform Jack that he must go up to the city early in the morning, with the carriage, to bring out a gentleman who was at the Pulaski House.

At one o'clock, on Sabbath, Dr[.] Pratt arrived. He was met at the carriage by Nellie, and her mother, and Mr. Thompson. Mr. T. extended to him a cordial welcome, and invited him to make his house his home while at the South. In this invitation, Mrs. T., after being introduced to the Doctor, cordially united. Dr. Pratt was surprised at the open hearted frankness and generosity of his new friend. It was his first trip South, and he was not prepared to believe there was anywhere to be found such whole souled generosity, much less among the slaveocracy.

If the reader desires a description of Daniel B. Pratt, D. D., they can just imagine a short, stout man, with large blue eyes, a bald head, a fair skin, and a large roman nose, with a polite and easy address, and a real "down Easter's" brogue, compressed lips, erect head, rather inclined to throw it back, with a large natural protuberance on the top of the head. He was phronologically a man of self-will, self-esteem, and great firmness, amounting to stubbornness.

At three o'clock Mr. Thompson asked Dr. Pratt if he would accompany him and Nellie to the negro church to witness a negro Sunday School and Prayer meeting. He readily consented. A walk of near a half mile brought them to a neat little painted house with glass windows, and a bell. On entering they found about

Page 21

thirty negro children, all in clean clothes, some with hats and some with bonnets, and some bare headed, seated on the front benches.

A white lady was sitting near. She was a worthy young lady, and I must honor my readers with an introduction to her.

Miss Kate Nelson was the governess in the family of Mr. Thompson. She was "to the manor born," a true Georgian lady. She was thoroughly educated, graceful, dignified and intelligent, modest and retiring, but not bashful. She knew her duty, and as a conscientious christian, was always found laboring to discharge it. It was her custom, at Mr. T.'s request, to teach his young negroes, orally, every Sabbath afternoon, and learn them to sing. In catechising them, she asked the question and then answered it, and made all the pupils repeat it after her two or three times till they could remember it. They displayed an accurate knowledge of the creation, flood, calling of Abraham, the ten commandments, &c. In learning them to sing, it was her custom to read the first line of the verse, then have them all repeat it, then read the other in like manner, then repeat both together, and so through the song, singing each verse as soon as they could repeat it. I observed that Miss Nelson seemed partial to those songs which had a chorous, and the school seemed to sing them with greater zeal.

The little ones all sang with open mouths and extended voices. It was really refreshing to see and hear them. They were always delighted with the exercises, and engaged in them with their whole soul and mind. They felt complimented when honored with the presence of "Mas' George," which was not unfrequent.

The New England clergyman was surprised, but was evidently reluctant to believe that any "good thing could come out of Nazareth." He expressed no approbation, for the sin of slavery could not be atoned for, in his estimation, by anything which the master could do. Nellie was delighted, "enthused," carried away with the scene. She was extravagant in her praise, and her generous young heart the impulses she so eloquently expressed.

Before the exercises closed, the house was moderately filled with adult people, who had come in to attend the prayer meeting.

As soon as the Sabbath School exercises were concluded, the children were dismissed, to go home or remain as they pleased. Many of them moved to seats a little in the rear, and soon all was still and quiet.

Dick, the chorister, lined out and led in singing--

"When I can read my title clear."

Page 22

All joined in swelling the strain, and many made "melody in their hearts unto the Lord." Negroes love to sing, and never drawl out their words into discordant sounds. There is no dragging in their voice, never a nasal sound. The lips apart, the head thrown back, the chest expanded, the eyes generally closed, and a full, round, sonorous voice is uttered forth by each; the commingling of which charms and thrills the heart of the listener.

At the conclusion of the song, one of the colored brethren, at the request of "uncle Jesse," led in prayer. Brother Jesse arose and addressed Dr. Pratt, as the "visiting brother," and invited him to conduct the meeting, but the Doctor declined, rendering as an excuse, ill health, and fatigue, but promised to do so at some future day, if he could.

"Uncle Jesse" then read the 14th Chapter of John, one so interesting to every christian heart. He paused and gave a short comment on the first of the chapter, reminding them of the blessed mansions in their Father's house; and the coming of the Savior for them, when all was completed for their comfort; concluding his address with many earnest words of exhortation, and then closing by prayer. He asked as was his custom, if any other brother had anything to say. Brother Gabriel, a tall black, middle aged man arose and said:

"My bredren, I's happy on dis nospicious occasion to 'zort you on in de pilgrimage. Abraham, he set one foot fore de tudder in gwine to Canaan, but he met de lion in de den, and be squash him to de ground, and vociferate him to death. Dat was a solemngizin' sight, 'twixt Abraham an' de lion. He growl and turn he hair de wrong way, and grin and show he long sharp teeth, and Abraham, he no staggulated in de least, but only de more violenter; he put forth he hand and wench him into nothin'. Den Joshua, he start to de promised land, and he meet de blazin sarpent, but he no go back. No, he say, Ef you no git out'n my way, I bruise you head. And good as he word, he smash he head wid he rod o' blossoms, what he walk wid; and de sarpent he dead quicker. Now bredren, what you do ef you be dar, I feard you run, you go back, you no go ober de lion an' de blazin' sarpent. But ef you see Abraham standin' on Nebo lookin' over into de promised land, and see him die a shoutin', case he so happy, den you want to smash de lion too. And ef you see Joshua standin' on Mount Zion, talkin' wid de Lord face to face, for forty days, and see he face shine bright as de moon, clear as de sun and terrible as an army wid banters, den you be willin' to meet the 'noxious warment, and distribute he head from he body.

Page 23

"My bredren, we hab de lion ob dis world, and de sarpent ob de debil to meet ebry day. De one got he den ebry where, de udder kindle her fire under you' feet. Watch all de day long, and pray de night tru' my bredren and sisters. Watch all de year, and all de life long. Don't be onconsiderate, but 'joice all de way, and let de anxiety ab de heart be above, and run de way wid laquity an' light. Ef you fight de lion, like Abraham, an' 'molish de sarpent like Joshua, den when you comes down to de dark waters of Jubilee, you will mount de milk white hos', and fly away to Gallilee. Amen"

During this short, pathetic address, many "Amen's," "dat's so." "bless God", and "I feels 'em," were uttered by the colored auditory.

In conclusion they sang on "Jordan's stormy banks I stand," with the chorus, "I am bound for the promised land." Beginning with the last speaker, all moved round, indiscriminately shaking hands, swaying to and fro, keeping time with the music. When they reached the little circle of whites the scene became affecting in the highest degree. "God bless you master," "God bless you, mistis." "We'll meet in heaven," "O sweet Jesus," and similar expressions were uttered by most of them, while the big tears that rolled down their faces and the powerful grasp of the hand, manifested the sincerity of the ardent impulses which were so apparent.

Nellie wept great tears of joyous sympathy, and so did Mr. T., Alice and Miss Nelson. Dr. Pratt alone remained unmoved, untouched by the happy scene before him. He seemed as emotionless as a statue of marble.

With the exception of Gabriel's speech, everything connected with the meeting was solemn and deeply affecting, well calculated to leave the heart with better feelings and desires. But Dr. Pratt was greatly disgusted with slavery when he heard the ignorance of Gabriel. He did not remember that some white ministers had displayed as great a want of divine knowledge, only they had clothed their ignorance in better language. For instance: one white minister pronounced Leper Leaper, and said, "The Leaprosy made persons leap like a frog." Another said "there was sixteen other young men rared up in and around and about me, but now where is um? They is scattered to and here and fro and there, and I is left a loneful watcher upon the hill-tops of Zion." Another said, "the Savior put fur skins in the water to turn it to wine." Another examined to see if Jonas, Simon Peter's father, "was the same who swallowed the whale."

Page 24

But I must leave my readers to their own conclusions. It is for me to state facts, and for you to draw whatever deductions you may please. It may be well to premise, however, that we should be guarded never to identify an institution with its abuses. Every blessing of heaven is abused, more or less, in the hands of sinful men.

Nor should we judge of a people by a single man of the race, who is not a representative character. It would be unjust to judge the American people by such a baboon as Abraham Lincoln, or the South by such a traitorous blackguard as Brownlow. Nor should negro intelligence be adjudged by the standard of Gabriel.

As they walked back to the house, Mr. Thompson turned aside to a negro cabin to see a sick servant, while the doctor and Nellie walked on.

With eyes yet red with weeping, Nellie turned to the doctor and said: "That was a melting sight; the simple-hearted, sincere piety of these poor negroes, is perfectly fascinating to me. The perfect freedom from all ostentation and formalism, the unrestrained and unaffected fervor of impulse, the big tears, the hearty grasp of the hand, the honest, heartfelt "God bless you," is really refreshing to me. This must be primitive christianity, unadulterated by the spirit of the world. I thank God their masters feel so pious an interest in their souls, and that their efforts at evangelizing them have met with such signal success. They are the happiest people I ever saw."

Without raising his head, the doctor replied morosely: "They are the most miserable wretches unhung. To play the hypocrite as they did to-day, just to please and obey a tyrant whom they call 'master.' There was no religion in it. The whole form and pretensions were enacted in obedience to your uncle's behests. It is the deepest and most fearful form of hypocrisy, thus to tamper with the solemnities of religion. Your tears surprised me, I would as soon think of weeping in a bedlam."

They had arrived at the house, and the conversation ceased. Poor Nellie felt mortified and disappointed in the severe censoriousness and mistaken views of her pastor. She knew he was mistaken, but could only wish and pray that future developments might remove his false impressions.

Page 25

CHAPTER III.

Nellie Retires from the Discussion--Dr. Pratt takes her Place--Perpetuity of Slavery--An ancient Slave's Opinion--Slavery in the Decalogue.

Mrs. Norton and Nellie were delighted to see their pastor. It was really refreshing to see a Northern face in their temporary Southern home, and to meet one congenial spirit, who could enter into all their feelings, and with whom they could converse freely on the subject of slavery. Mr. and Mrs. Thompson, too, were glad to receive and entertain the pastor of their relatives, and finding him an educated gentleman of extensive and varied information, he was a most welcome guest.

He frequently rode with Mr. T. over his farm and saw his negroes at their work. He saw their toil and sweat, and heard their cheerful songs and merry laughter. He asked a great number of questions as to their dispositions, contentment, subordination, morals, &c.

Turning to Mr. Thompson, one day, as they rode along, he said, "I am surprised to find a man of Northern birth and education holding men, women and children in involuntary servitude." "Why?" said Mr. T. "Because Solomon said, 'train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it,' and I know you were trained differently from your present practice?" "True," said Mr. T., "but Solomon did not say, train up a child in the way he should not go, and when he is old he will not depart from it. If he is trained rightly he will not depart from it, but if wrongly, he may be led by a kind Providence to discover his error and abandon it. My early education on the subject of slavery was all wrong. I have by the goodness of an all-wise Providence been led to discover and abandon the error."

"You do not pretend to defend slavery as right, do you?"

"If I did not, I should abandon it before another day."

"Well, I suppose I need not be surprised, for there is no telling what an influence prejudice, or cupidity, may exert in forming the conclusions of the human mind."

"Nor early education and fanaticism,"said Mr. T. They had both arrived at the gate, and alighting from their horses, the conversation ceased.

After a moment's absence in his room, Mr. Pratt took his seat in

Page 26

the parlor. Nellie was just finishing a very difficult piece of music on the piano, and was soon seated near her pastor.

"You have had a pleasant ride this morning, I hope," she said as she drew near him.

"The ride was pleasant, but I have brought all my sympathy for the poor suffering negro with me, and find it is going to be a 'thorn in the flesh,' a 'body of death,' clining to me. It will greatly mar, if not entirely destroy, the pleasure of my visit South."

"Do you think the negroes here are as unhappy as you expected to find them, before you came?" said Nellie.

"They do not seem to be so, but it may be they are too well trained to show their discontent before strangers. They seem as cheerful as laborers in wheat harvest. They talk, and laugh, and sing, and pat, and dance, and appear not to feel their bondage, but this cannot be possible. The bare idea that they are slaves fills me with horror."

"But do you think them capable of doing as well for themselves, if they were free, as they are now doing in a state of slavery? To test the matter, how do they compare, in prosperity and happiness, with the free negroes in New England?"

"Very favorably, I must confess. No doubt but they are better fed and clothed, and are less liable to temptation and vicious habits. But they are slaves and have no rights. The system of bondage has taken away from them the heritage bequeathed to them by their Creator. All men are born free and equal, and no one should dare infringe upon the universal rights of man."

"But", said Nellie, "as yow seem to think the infringement of these rights 'feeds and clothes' them better than freedom does, and that 'they are less liable to temptation and vicious habits'--in a word, makes their condition better than it otherwise could be, is it not a mercy, rather than an injustice, to hold them in such servitude?"

"What do you mean, Nellie?" Has your short stay already poisoned your mind with abominable pro-slavery sentiments? You talk like a Southern slaveholder."

"O, no," said Nellie, "these were impressions made upon my mind by observing uncle's servants, and I wanted an answer to the argument. I have observed them in their domestic duties, in their festivals, in their sports and past times, and in their religious devotions, and I am sure I never saw a laboring class at the North so happy, so uniformly cheerful, or more 'fervent in spirit, serving

Page 27

the Lord,' and the suggestion has occurred to me, that after all, bondage may be the condition assigned them by Providence."

"You astonish me, Nellie! God is a holy, just and merciful being, and could never, either by His word or providence, sanction so unholy a thing as slavery. The Bible teaches no such thing, and if it did--well I think I should have to appeal to the higher law of conscience."

Nellie looked thoughtfully at him for a moment, and then asked with much seriousness, "Mr. Pratt, is the authority of conscience superior to the authority of the Bible?"

"That is a theologico-metaphysical question, the discussion of which we will defer to another time," was Mr. P.'s reply.

Nellie manifested no further surprise at this ignoring of the word of God as supreme authority on all moral subjects. She had heard it often before, and had been pretty well educated in the same views; but the struggles she had recently experienced had made too deep an impression on her mind to be soon forgotten. She thought it best to give a slight turn to the conversation, and so remarked, "Uncle and I have agreed to investigate the subject of slavery from the Bible; we have had one evening's conversation, and I must confess some surprise at the plausibility of his arguments. The truth is, I am unable to meet the question upon scriptural grounds, though I am certainly not so well versed in the Bible as I ought to be. As you are to spend several days with us, by your permission, I will turn over my part of the discussion to you. I am sure you are a whole hearted abolitionist, and certainly will be an overmatch for my pro-slavery uncle. Will you thus relieve me, and permit me to sit by as an interested listener?"

"Certainly, if your uncle has no objection. And who knows but I may be sent here by Providence to convince a christian slave holder of his error; and that he, by liberating his slaves may rebuke this "sum of villainies," and set his neighbors a worthy example. If he is not lost to all reason, I shall be able to convince him, I am sure. Argument, sarcasm and ridicule, have great power. Then he can not stand before such men as Wayland, and against the moral rebuke of the civilized world. I am ready at once, to enter upon the discussion."

Mr. Thompson entered just as the clergyman ceased speaking.

Nellie lost no time in introducing the subject. "Well, uncle, I have engaged Mr. Pratt as my representative in our Bible discussions on slavery. He has consented to take my place, if you have

Page 28

objection, and as you are so confident of your ability to justify very from the Bible, I feel sure you will consent to the arrangement. Your Southern chivalry will naturally desire a foeman worthy of your steel."

"Thank you, Nellie. I am pleased with the arrangement. I shall have a double advantage in Mr. Pratt. A scholar fully able to understand the meaning of the Divine word, and a christian with moral honesty enough always to concede a point when fairly established from the infallible source of truth. I can only express surprise that a student of the Bible should not already have so far satisfied himself on the subject as to admit without further investigation, that slavery is a divine institution, that it is of God."

"So far from this, sir," said Mr. Pratt, "I believe it is the institution of Satan, and only permitted to exist for a short time, like other sins which are forbidden, as a scourge to our race, as a trial to us, to prove man, and see what are the depths of depravity which exist in his heart. I am only surprised to see a man of your intelligence and professed piety, holding slaves. To see you guilty of such injustice to your fellow beings as to hold them in bondage, forging chains and riveting them upon them, and crushing out their manhood with the "weight of servitude."

"Do you believe," said Mr. T., "that the negro is less a man in his southern bondage, than he is in his African idolatry and superstition? Do you believe his contact with the social and religious elements of southern society, though restricted by slavery, has degraded him beneath the Bushman, the Hottentot, the Cannibal, or even below the somewhat more elevated Central Africans, who bow down daily to their household gods, and who in their superstition, lay on the funeral pile, the surviving widow to be consumed with the body of her deceased husband? Do you think the enlightened and christian slave, is less happy, less contented, less elevated in the scale of moral existence, than his ancestors were in the dark land of Ham? Your familiarity with ethmology, has long since taught you that southern slaves are the happiest of all their race, and approximate more nearly the great object for which God has created man. This being undeniably true, then where is the injustice of which you speak? Is it doing a man injustice to enlighten his ignorance, to teach him how to enjoy the social relations of life, to deliver him out of barbarism and introduce him into civilized life, to break the fetters of idolatry and superstition, and teach him the knowledge of the true God, to take his being and fill

Page 29

it with all those holier purposes, desires and aspirations, which have been so long exiled by the reigning demon of darkness? If this be injustice, then sir, do we plead guilty to the charge, not otherwise."

"Injustice is done a man," said Mr. Pratt, "when his natural or acquired rights are taken from him, no matter what these rights are, or whether he uses them or abuses them; if he should misuse them, the wrong is to himself."

"I suppose then," said Mr. Thompson, "if a man purchase a gun to shoot himself, and I knowing that fact, take it away, I do him an act of injustice, by taking away from him the power to commit suicide. If a man threatens the life of another, the officer who arrests and imprisons him, thereby preventing murder, does injustice by stopping the abuse of physical liberty; or if a woman, in a violent passion is about to beat her child to death, and I seize hold of her, and by constraint dispossess her of the freedom to kill her child, I do her injustice. Or to put a very plain case, when a man becomes so depraved that he is not restrained from the violation of law, and a court imprisons him as a felon, it does him injustice. Or if an individual refuses to pay his just debts, and his creditors by due process of law, imprison him, they do him an act of legal injustice. Sir, is this your sense of justice? You cannot deny that these are legitimate deductions from your premises."

"O, that is not what he meant, uncle," said Nellie, rather impatiently, as she saw her representative had committed himself too far, and that her uncle was making him appear the advocate of a most licentious and wicked freedom, and taking from society all lawful means of self-protection.

"I mean, sir, that God has made 'all men free and equal,' and any infringement of this freedom and equality, except for the maintenance of law and order, is an act of injustice, and one at which a pious man should shudder."

"You take for granted the very point in issue, and quote from the Declaration of Independence instead of the Bible. God did not make all men free and equal. He has enslaved some by placing them in bondage to others. Ham manifested the wicked traits which afterwards developed themselves in his descendants, and on this account Heaven forged the chains of slavery and placed them upon him, using his father, Noah, as His agent. Hear Him: 'Cursed be Canaan, a servant of servants shall he be to his brethren. And he said, blessed be the Lord God of Shem, and Canaan shall be

Page 30

his servant. God shall enlarge Japhet and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem, and Canaan shall be his servant' Thus when there was but one family on earth, a portion of it was doomed to servitude. A 'servant of servants,' the menial, the slave of servants. Now, was this slavery? If so, was it of Satan or of God? If of God, has he made all men free and equal? Were Ham and Japhet made equal, when one was placed over the other? Were both made free when one was put under slavery to the other? There is a great deal of prating nonsense in the world claiming very high and respectable paternity."

"But let us take a step further, and see how the Divine institution of slavery was afterwards regulated under 'father Abraham,' who owned perhaps a thousand slaves. When the covenant of circumcision was instituted, God told him 'He that is born in thy house, and he that is bought with thy money, must needs be circumcised.' Here was a recognition and a ceremonial regulation of the institution. One of the servants of this 'father of the faithful,' afterwards recognized slavery as the ordination of God, although himself being in bondage under the divine decree. He said, 'And the Lord hath blessed my master greatly, he is become great; and He hath given him flocks and herds, and silver and gold, and man servants and maid servants.' They were not hired servants, for they were born in his house and bought with his money, just as Southerners hold slaves. This honored slave of Abraham did not look upon the institution which held him in bondage as an evil, but a blessing, 'the Lord hath blessed my Master greatly.' But again look at the light in which the law recognized it. In Exodus it is said, 'If a man smite his servant or his maid with a rod, and he die under his hand, he shall be surely punished; notwithstanding if he continue a day or two, he shall not be punished, for he is his money.' Now if such a law as this were found upon a Southern statute book, the world would be filled with holy horror, at its inhumanity; yet such is the enactment of Him who doeth all things well. Here too is a recognition by the divine law, of the property of one man in another, one man is the money, the chattel of another. Again the sickly sensibilities of erring man, are shocked at the revealed will of the King of all the earth. Uzza feared to trust the tottering ark to the Lord, and put forth his hand to save it, but his presumption was punished by instant death. Let us take timely warning. What God gives we will receive, what he commands, we will obey, what he withholds we will not covet. We are always safe under the guidance of unerring wisdom. 'It is the Lord, let him do what seemeth good unto him.'"

Page 31

At this stage of the argument, the parties were interrupted by a summons to dinner. Nellie and the parson both felt relieved at the prospect of having time for reflection before being compelled to reply to the proofs presented by Mr. T.

Dinner being over, the parties retired to their several apartments, and, at five o'clock, all re-assembled in the parlor, feeling the more cheerful for having enjoyed a refreshing nap.

"Mr. Thompson," said Mr. Pratt, "I discover you are a strict constructionist. I do not adhere so much to the letter, as to the spirit of the Bible. The letter killeth, but the spirit maketh alive. I do not attach so much importance to detached portions of revelation, as I do to the character and attributes of its Great Author. He is too holy to authorise sin; too merciful to place one man in the power of another; too just to discriminate so widely between the privileges he confers upon his intelligent creatures. He will never give to one people the right to place the galling yoke of slavery upon the necks of another. He will never place one tribe or nation under the feet of another to be trod upon. He will never appoint an institution, which crushes out the manhood, and effaces the human feelings of any race, reducing them to the level of beasts. This is not in accordance with the Divine character. I honor and reverence the Divine name too much to admit any such thing. 'Justice and judgment are the habitation of his throne,' but there is neither justice nor mercy in slavery."

"You decide what the Bible ought to teach," said Mr. T., "by your knowledge of the character of Deity, and not by what He has really said. Pray, from what source do you derive your knowledge of Him, if not from the Bible, and how do you know anything of his character from this source, only as you believe what it says? Then you admit, that the Bible as a whole is true; and if so, its detached portions are also true. You must either admit that the quotations made are interpolations, or they are the words of God. If the former, then the 'onus probandi' rests upon you, and I am ready to hear your proof. If they be the words of God, you must admit that slavery is taught in the Bible, and instituted in Heaven. In your sermons at home, you urge upon your congregation the necessity of repentance, and to prove its importance you quote detached portions of the word of God, and so of every other truth, however important, which is taught in the Bible. I have heard ministers say, (and you may have done the same,) that to ascertain with certainty the meaning of any given text in the Scriptures, it is best

Page 32

to consult all the parallel passages. This fact attests the truth well known and acknowledged by all Bible students, that the Scriptures do not exhaust any subject in any one given verse, chapter or book. It is one of the evidences of the inspiration of the Bible, that a most beautiful and striking harmony is maintained by the writers of the various books of the Bible, when treating of the same subject. But with this fact, you are more familiar than I, as you are professionally a theologian. Your proposition to judge what God will teach by his character, and not by his word, reminds me of a little private discussion to which I once listened. It was between a minister and an infidel. The former was affectionately urging upon the latter the importance of personal religion, as necessary to his happiness here and hereafter, and quoted the Scripture, 'Godliness is profitable unto all things, having promise of the life that now is, and of that which is to come,' and then added, 'He that hath the Son hath life, but he that hath not the Son of God, hath not life.' The infidel replied: 'I do not wish to hear anything from the Bible. God has given me reason, and my reason tells me that God is too great and good a Being to doom a soul to perdition just because he refuses to believe on his Son.'"

"Your premises lead to the infidel's conclusion, and I must confess profound astonishment at its enunciation by a religious teacher. If the Book of God is taken at all, it must all be taken; for 'all Scripture is given by inspiration of God, and is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction, for instructions in righteousness.' Permit me to suggest, that the passages referred to, may have been given for the 'correction' of the errors of abolitionists, and for their 'instruction in righteousness,' since their tendency to depart from truth certainly needs a counteracting influence.

"Peter, speaking of the olden time, seems to have apprehended a disbelief in those, or some other portions of the old Scripture, and, therefore, under the direction of inspiration, says: 'For the prophecy came not in old time by the will of man: but holy men of God spake as they were moved by the Holy Ghost.' You will have, my dear sir, to admit slavery, or reject the Bible--which horn of the dilemma will you take?"

"Neither, sir," said the minister, "I will reject slavery and take the Bible. I will, however, admit, for the sake of argument, that in those dark ages, God permitted it on account of the hardness of the people's hearts, as he did divorces and other wrongs, which were to be of temporary duration, and which were to give way before the

Page 33

progressive civilization of the world, as the darkness is dispersed before the sun, and heathenism before the gospel of Christ."