John Chavis. Antebellum Negro Preacher and Teacher:

Electronic Edition.

Weeks, Stephen Beauregard, 1865-1918.

Funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Matthew Kern

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Matthew Kern, and Jill Kuhn Sexton

First edition, 2002

ca. 20K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2002.

(caption title) John Chavis. Antebellum Negro Preacher and Teacher

Stephen B. Weeks

p. 101-108

Hampton, Virginia

Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute

1914

Call number Cp326.92 C51w (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

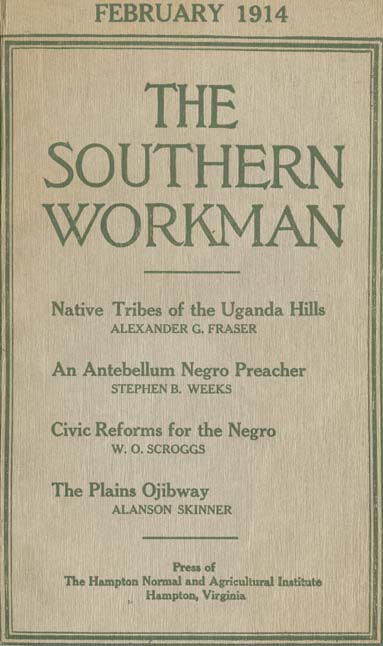

Appears in The Southern Workman (February 1914).

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Chavis, John, 1763-1838.

- African American teachers -- North Carolina -- Biography.

- African American missionaries -- North Carolina -- Biography.

- African American clergy -- North Carolina -- Biography.

- African American Presbyterians -- Clergy -- North Carolina -- Biography.

- Presbyterian Church -- United States -- Clergy -- Biography.

Revision History:

- 2002-1-16,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2002-04-15,

Jill Kuhn Sexton

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2002-02-25,

Matthew Kern

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2002-01-25,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

Page 101

JOHN CHAVIS

ANTEBELLUM NEGRO PREACHER AND TEACHER

BY STEPHEN B. WEEKS

WHEN an individual who is born in the lower ranks of life, by energy, ambition, and industry wins recognition and respect from his superiors, he is worthy of becoming a model and guide for others to follow. When therefore a black man, born in the midst of an aristocratic slaveholding oligarchy, develops such intellectual power and force of character as to command, despite race and social position, not a grudging, but a cheerful recognition from the exclusive aristocracy among whom he lives, he can well be pointed to as a source of inspiration and help to all future generations of his people ; for his career should convince them that personal excellence will win its way even though faced by the heaviest odds.

Such was the career of John Chavis, a full-blooded North Carolina Negro of the last century, who served the white race, as well as his own, as a minister and teacher for many years. Of his early life we really know nothing. In 1832 he said of himself, "If I am black, I am a free-born American and a Revolutionary soldier." With this exception we have no authentic information until we turn to the Acts and Proceedings of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in the United States, where, under the year 1801, we find the following resolution: "That . . Mr. John Chavis, a black man of prudence and piety, who has been educated and licensed to preach by the Presbytery of Lexington in Virginia, be employed as a missionary among people of his color, until the meeting of the next General Assembly ; and that for his better direction in the discharge of duties which are attended with many circumstances of delicacy and difficulty, some prudential instructions be issued to him by the Assembly, governing himself by which, the knowledge of religion among that people may be made more and more to strengthen the order of society."

The next year it is stated in the Acts and Proceedings "That the journal of Mr. John Chavis, a black man licensed by the Presbytery of Lexington, in Virginia, was read in the Assembly. He appears to have executed his mission with great diligence, fidelity, and prudence. He served as a missionary nine

Page 102

months." It was again resolved "That Mr. John Chavis be appointed a missionary for as much of his time as may be convenient." In 1803 ( not before ) Chavis is officially reported as a licentiate of the Presbytery of Lexington, Virginia, and it was again resolved that he be employed as a missionary "for the times and on the routes specified in the report." The missionaries so employed were to be "left at discretion as to the time of the year in which to perform their services, provided their terms be completed so as to enable them to report agreeably to the instructions of the committee of missions."

In May 1804, the General Assembly again employed him as a missionary for three months and he was to travel in the southern part of Virginia and in North Carolina. The next year the Synod of Virginia reported "That Mr. Chavis, a missionary to the blacks, itinerated in several counties in the south part of the state ; but owing to some peculiar circumstances, stated in his journal, his mission to them was not attended with any considerable success." Notwithstanding this seeming lack of success he was again employed ( for 1805 ) for six months, "to pursue nearly the same route as last year, and employ himself chiefly among the blacks and people of color." In 1806 he was employed for two months and directed to spend his time "among the blacks and people of color in Maryland if practicable ; otherwise at his discretion," and in 1807 it was ordered that he be employed three months among the blacks in North Carolina and Virginia and that his route be left to his discretion.

After 1807, Chavis disappears from the Acts and Proceedings of the General Assembly. It is said that he returned to North Carolina about 1805 and the records of the Hanover Presbytery show that he was dismissed by it in 1805 to join the Orange Presbytery in North Carolina. In 1809 he was received by the latter as a licentiate and for the next twenty years seems to have preached pretty regularly in Granville, Wake, and Orange Counties. It is perhaps impossible at this late date to say whether he held regular pastorates of white churches. It is certain that he continued more or less regularly the work which he had already been doing for the General Assembly, performing missionary service among the Negroes and preaching from time to time to white congregations.

As a result of the Nat Turner insurrection in Southampton County, Virginia, in August 1831, the North Carolina legislature in 1832 passed an act silencing all colored preachers. With reference to this act, as applied to Chavis, we find an entry in the Proceedings of the Orange Presbytery, under date of April 21, 1832, as follows:

"A letter was received from Mr. John Chavis, a free man of

Page 103

color, and a licentiate under the care of the Presbytery, stating his difficulties and embarrassments in consequence of an act passed at the last session of the legislature of this state, forbidding free people of color to preach : whereupon, Resolved, That the Presbytery, in view of all the circumstances of the case, recommend to their licentiate to acquiesce in the decision of the legislature referred to until God in His providence shall open to him the path of duty in regard to the exercise of his ministry."

It does not appear that Chavis preached after this date. Of his abilities as a minister we have the testimony of the late George Wortham, a lawyer of Granville County, who wrote in 1883 : "I have heard him read and explain the scriptures to my father's family and slaves repeatedly. His English was remarkably pure, contained no negroisms ; his manner was impressive, his explanations clear and concise, and his views, as I then thought and still think, entirely orthodox. He was said to have been an acceptable preacher, his sermons abounding in strong, commonsense views and happy illustrations without any effort at oratory or any sensational appeal to the passions of his hearers. He had certainly read God's Word much and meditated deeply upon it. He had a small but select library of theological works, in which were to be found the works of Flavel, Buxton, Boston, and others. I have now two volumes of Dwight's Theology which were formerly in his possession. He was said by his old pupils to have been a good Latin and a fair Greek scholar. He was a man of intelligence on general subjects and conversed well. I do not know that he ever had charge of a church, but I learned from my father that he preached frequently many years ago at Shiloh, Nutbush, and Island Creek churches to the whites."

He even aspired to religious authorship and published in 1837 a pamphlet entitled "Chavis' letter upon the Doctrine of the Atonement of Christ," in which, although a Presbyterian, he argues strongly against the popular conception of Calvinism and insists that the atonement "was commensurate to the spiritual wants of the whole human family." This pamphlet is said to have been widely circulated but no copy has come under the eye of the present writer.

It was not, however, as a minister but as a teacher of white boys ( and apparently of white girls also ) that this free-born, full-blooded Negro was of most service to the State of North Carolina. For the greater part of the time after he was silenced as a preacher in 1832, and most probably for a large part of the time from his return to North Carolina until his death in 1838, he conducted a private school in Wake County and perhaps in Chatham, Orange, and Granville Counties. The school was a peripatetic one and changed its location from time to time according to

Page 104

the encouragement offered. He numbered among his pupils some who became distinguished in the next generation. Among those who are known to have attended his school were Priestly H. Mangum, brother of Senator Mangum and himself a lawyer of distinction; Charles Manly, Governor of North Carolina; Abram Rencher, minister to Portugal and Governor of New Mexico; Mr. James H. Horner, founder of the Horner School; as well as others of less distinction. His school served as a high school and academy for the section in which it was located. One of the extracts already quoted gives us some idea of his scholarship and it seems that he prepared some of his pupils for the University of North Carolina.

His abilities as preacher and teacher and his high character brought him an acquaintance with the leading citizens of that section of the state, by whom he was treated with every mark of respect. We have a very pleasing account of this from Mr. Paul C. Cameron, who wrote in 1883:

"In my boyhood life at my father's [Judge Cameron's] home I often saw John Chavis, a venerable old Negro man, recognized as a free man and as a preacher or clergyman of the Presbyterian Church. As such he was received by my father and treated with kindness and consideration, and respected as a man of education, good sense, and most estimable character. He seemed familiar with the proprieties of social life, yet modest and unassuming, and sober in his language and opinions. He was polite, yes, courtly, but it was from his heart and not affectation. I remember him as a man without guile. His conversation indicated that he lived free from all evil or suspicion, seeking the good opinion of the public by the simplicity of his life and the integrity of his conduct. If he had any vanity, he most successfully concealed it. He conversed with ease on the topics that interested him, seeking to make no sort of display, simple and natural, free from what is so common to his race in coloring and diction. . . . I write of him as I remember him and as he was appreciated by my superiors, whose respect he enjoyed."

His relations with Judge Mangum were very intimate. I might say they were affectionate, even fatherly. He was an occasional visitor at the house of the Judge and was treated with all deference and courtesy, so much so that it caused astonishment and questioning on the part of the younger children, which was met in turn by, "Hush, child, he is your father's friend." The letters of Chavis to Judge Mangum which have come down to us indicate no social inequality. They are written in the frank friendship which has bridged all social distinctions, and when read between the lines give us glimpses of the power of intellect and character to overcome the mere conventionalities of society. They give us also an insight into the political views of the writer. We learn something of the history of private schools in the state, something of his ideas of pedagogy, and above all they serve as an inspiring example to others. They extend from 1823 to 1836 and

Page 105

cover all sorts of subjects, but in particular politics and teaching. I have room for only a few extracts.

In his first letter he says: "I am very anxious respecting the presidency. I am very fearful that Mr. Crawford will not be elected. . . . There is much rumor abroad that you will not be elected again because you support the election of Mr. Crawford." In May 1826: "I am teaching school where I did last year and should you be traveling this road I shall thank you to call on me." He was opposed to agitating the question of Federal amendments, "because once a beginning is made to amend the Constitution away goes the best of human compacts." He did not hesitate to oppose the wishes of Judge Mangum. In 1827 he writes: "You know that I have ever opposed every stage of your political life, preferring your continuance at the bar until you have acquired a competent fortune."

In March 1828, he writes: "I am much more helpless than when you saw me. You cannot conceive what it costs me to attend to my school. My number at present is 16 and it may probably amount to 20." In September 1831: "I must plainly and honestly tell you that I have ever been grieved that you were the professed political friend of G[eneral] Jackson. Please to give my best respects to Mrs. Mangum and tell her that I am the same old two and sixpence towards her and her children, and that she need not think it strange that I should say that her children will never be taught the Theory of the English Language unless I teach them. I say so still. I learnt my Theory from Lindley Murray's Spelling book which no other Teacher in this part of the country Teaches but myself and I think it preferable to the English Grammar."

In March 1832, he returns to the same subject: "It is four weeks today since I left your house at which time Mrs. Mangum and myself wrote to you respecting my teaching school for you. . . . So anxious am I to Teach your children the Theory of the English Language that I am truly sorry that I had not told Mrs. Mangum to write to you . . . that if nothing else could be done that I would come and teach Sally [Judge Mangum's oldest child, then eight years old] for the same you would have to give for her board in Hillsborough, provided you would board me and let me have a horse occasionally to go and see my family." Then he falls into politics: "Oh, my son, what will you do with the overwhelming eloquence and masterly disquisitions of Mr. Clay?"

In July 1832, he writes that if Mrs. Mangum "will condescend to board out Sally and send her to a man of my stamp I can have her boarded at an excellent house. . . I desire to teach her the Theory of the English Language which she never will be

Page 106

taught unless I teach her, because no other person in this part of the country teaches it but myself, and my manner I deem far preferable to the English Grammar. I wish you to make this statement to Colonel Horner and tell him that I want his daughter Juliana for the same purpose."

I have space for but one more quotation on politics and for his definition of character: "You appear to think that I have become unsound in politics. If to be a genuine Federalist is to be unsound in politics I am guilty. But pray how has it been with yourself? How often have [you] changed your Federal coat for a Democratic or Republican one? . . . I have ever been opposed to the election of G. J. [General Jackson] from the beginning to this day. . . . For honesty, integrity, and dignity is my motto for character."

Return to Menu Page for John Chavis. Antebellum Negro Preacher and Teacher by Stephen Beauregard Weeks

Return to The North Carolina Experience Home Page

Return to The Church in the Southern Black Community Home Page

Return to Documenting the American South Home Page