The Negro Population of North Carolina: Social and Economic:

Electronic Edition.

Larkins, John R. (John Rodman)

Funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Matthew Kern

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Matthew Kern and Melissa Meeks

First edition, 2003

ca. 155K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2003.

Source Description:

(series) Special Bulletin [North Carolina State Board of Charities and Public Welfare] no. 23

(title) The Negro Population of North Carolina: Social and Economic

Larkins, John R. (John Rodman)

79 p.

Raleigh, N.C.

North Carolina State Board of Charities and Public Welfare

[1944]

Call number Cp 326 L32n c. 3 (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- African Americans -- North Carolina -- Social conditions.

- North Carolina -- Population -- Statistics.

- African Americans -- North Carolina -- Economic conditions.

- African Americans -- North Carolina -- Statistics.

Revision History:

- 2003-04-09,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2003-02-06,

Melissa Meeks

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2002-03-14,

Matthew Kern

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2002-01-31,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Page Image]

[Title Page Image]

THE NEGRO POPULATION

OF NORTH CAROLINA

Social and Economic

BY

JOHN R. LARKINS

CONSULTANT ON NEGRO WORK

SPECIAL BULLETIN NUMBER 23

MRS. W. T. BOST

COMMISSIONER

NORTH CAROLINA STATE BOARD OF CHARITIES AND PUBLIC WELFARE

RALEIGH, N. C.

Page iii

FOREWORD

Although North Carolina long has officially worked for the improvement of conditions among its Negro citizens there still remain depressing situations calling for attention. Some of these conditions are even now in the process of correction and betterment.

Through the State's appreciation of its responsibility to all citizens, together with the spirit of interracial cooperation and good will that prevails, much has already been accomplished.

Especially noticeable is the current trend and effort toward wiping out the differential in salaries paid Negro and white teachers in the State's educational system. Again the current study leading to the betterment of health conditions and providing a modern system of medical care for all citizens of the State will include the needs of the Negroes of North Carolina. Provision of facilities for the feeble-minded Negroes is being looked into, and without doubt some action in this respect will be taken in the near future. The State has authorized the establishment of an institution for delinquent Negro girls, the need for which has long been recognized.

Attainment of these nearby goals will place North Carolina in the forefront and a little closer to the time when facilities will be provided to meet the needs of all groups of the State's population.

MRS. W. T. BOST,

Commissioner of Public Welfare.

Page v

AUTHOR'S ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In preparing this study the author has received cooperation and assistance from many individuals, organizations, and various departments of the State. To all of these he is grateful. He is indebted to Dr. Ira De A. Reid of Atlanta University for assistance in formulating the outline for the study. To Dr. Ellen Winston of Meredith College, the writer is obligated for counsel, suggestions, and advice and her painstaking reading of the entire manuscript. The author wishes to thank Dr. James E. Shepard, President of North Carolina College for Negroes, for his encouragement and faith in this subject.

The author makes acknowledgment of appreciation to Dean Foster P. Payne of Shaw University for reading manuscript. Dr. N. C. Newbold of the Division of Negro Education, State Department of Public Instruction read the manuscript and gave invaluable advice in the analysis and interpretation of the material of the study. To Miss Marie McIver and Mr. Albert E. Manley of the Division of Negro Education, the author is indebted for helpful suggestions.

Due acknowledgment has been made in the appendix of the departments, organizations and persons who contributed data for the study.

Without the assistance, advice, and encouragement of the members of the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare this study could not have been made. To Mrs. W. T. Bost, Commissioner, the author is indebted and grateful for permission to undertake this study, and for cooperation and guidance, without which this study could not have been completed. Mr. R. Eugene Brown read the manuscript and gave valuable suggestions. Miss Margaret Woodson read the manuscript and rendered inestimable assistance in compiling the facts, making charts, analyzing the material of the study, and in checking the manuscript. To Mrs. N. B. Inborden, his secretary, the writer expresses his appreciation for careful and efficient preparation of the manuscript.

JOHN RODMAN LARKINS

April, 1944

Page vii

CONTENTS

- Introduction 9

- I. Historical Background 11

- II. Characteristics of the Population 14

- III. Earning a Living 18

- IV. Homes and Families 24

- V. Health 29

- VI. Education 35

- VII. Religion 41

- VIII. Recreation 45

- IX. Delinquency and Crime 49

- X. The Disabled 52

- XI. Citizenship 57

- XII. Meeting the Problem 61

- Sources for the Facts 69

Page viii

LIST OF CHARTS

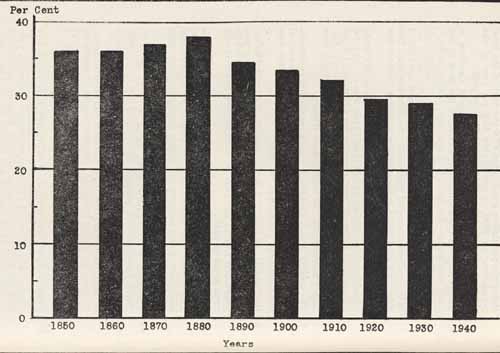

- I. Negro Population in North Carolina 1850-1940, Rate per 100 Whites 16

- II. Percentage of Negro and White Working Population Engaged in Specified Types of Occupations, 1940 21

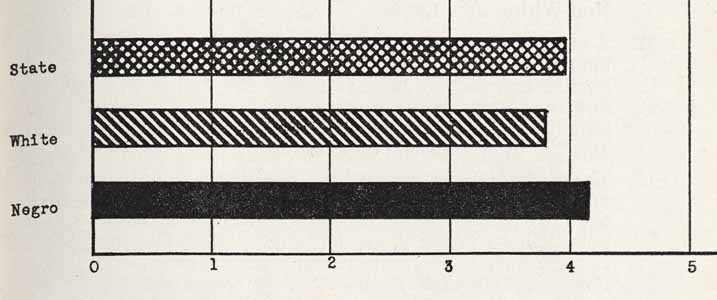

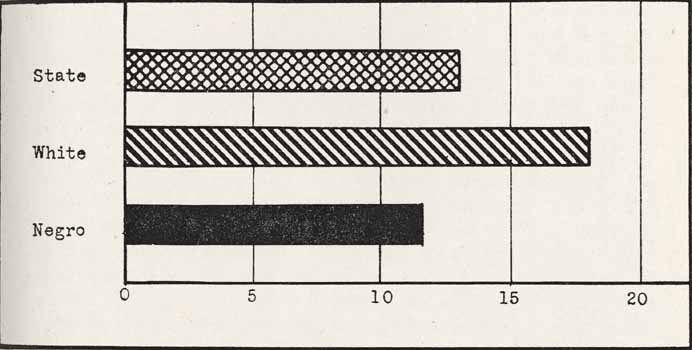

- III. Median Size of Families, By Race, 1940 27

- IV. Median Monthly Rental, By Race, 1940 27

- V. Percentage of All Deaths Among Females, Due to Tuberculosis, By Age and Race, 1940 31

- VI. Percentage of All Deaths Among Males, Due to Tuberculosis, By Age and Race, 1940 33

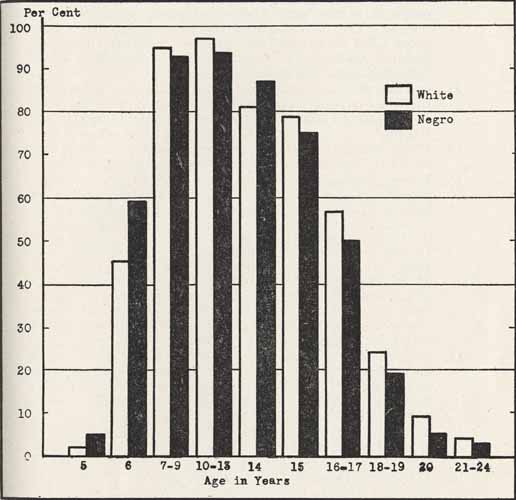

- VII. Percentage of Children Attending School, By Age and Race, 1940 37

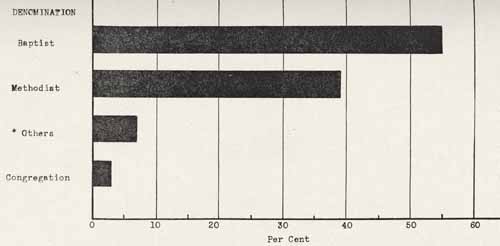

- VIII. Negro Church Membership, By Denomination, 1936 43

Page 9

INTRODUCTION

For some time it has been felt that there is need for a manual or study of North Carolina's Negro population to acquaint the general public with the existing social and economic conditions within the race, and to give a general picture of the historical background of the Negro in North Carolina. There is also a need to study the facilities and resources that exist to meet the needs of the group and those conditions that are unmet so that future plans to improve these facilities and resources may be organized around some of these unmet needs. There are large numbers of people who are unaware of the facilities and resources that are available and who do not know the objectives and functions of the various agencies which deal with the problems of the Negro. Many people are also unaware of the problems that often exist for the Negro group in securing even the necessities of life.

This study is an effort to point out the social and economic conditions existing among the Negroes of the State because they affect the individual's attempt to make a satisfactory adjustment to his total environment. It does not attempt to make an analysis of these conditions but to lay a foundation for subsequent studies of the race. It is also designed to stimulate thought concerning Negro problems and to provide a basis for a thorough consideration of these problems, looking to a determination of their causes, effects, and solutions.

The study is made from a social worker's point of view and with the hope that those who read it may understand the Negro's opportunities and limitations. Whenever the established institutions of society break down or there is a need for supplementing or modifying these institutions at points at which they have proved to be inadequately adapted to the needs of the individual and community, social work is called upon to assist. Social work may have for its objective the relief of individuals or the improvement of conditions. It may be carried on by the government, by an incorporated society, or by an informed group or individual. In order to understand the social problems of any group, all the factors involved must be considered. To comprehend the situation of the Negro, racial, psychological, religious, economic and social factors should be weighed and analyzed in their relationship to other factors.

Page 11

CHAPTER I

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

"How black men, coming to America in the Sixteenth, Seventeenth, and Eighteenth Centuries became a central thread in the history of the United States, is at once a challenge to its democracy and always an important part of its economic history and social development." Thus wrote Dr. W. E. B. DuBois, in his BLACK RECONSTRUCTION. As this was true of the Negro in the history of the United States, it may be applied to the Negro's entry into North Carolina.

With the beginning of her earliest life does North Carolina's Negro history start. In 1715, slavery was legalized in North Carolina, and it is believed by many historians that it was one of the earliest provincial culture traits borrowed from its southern and northern neighbors, South Carolina and Virginia. The early proprietors encouraged the institution of slavery and offered 50 acres of land for each slave above 14 years of age brought into the colony. Slavery was a little different in North Carolina from what it was in the other southern states, and grew very slowly at first due to the preponderance of small farmers who furnished their own labor.

It was not until the middle of the 18th Century that slavery increased rapidly and gained in any appreciable manner. In 1712, there were 800 slaves in North Carolina, by 1730, this number had increased to 6,000, and in 1790, there were 100,572 slaves in the State. By 1767, the Negroes outnumbered the whites in some of the eastern counties where the plantation system prevailed. In 1830, North Carolina's slave population had increased to almost one-third of the total population, but the slave period closed without any appreciable increase in the proportion of slave to white.

Slaveholding in North Carolina was concentrated in the Coastal Plains and Piedmont Regions. The greatest number of slaves to the square mile was in the counties along the Virginia border. In 1860, only five counties, Edgecombe, Granville, Halifax, Warren, and Wake contained more than 10,000 slaves. During this period thirty-six of the eighty-five counties in the State contained 71 per cent of the total Negro population and 58 per cent of the improved land under cultivation.

Although from the first it was committed to the slave regime, North Carolina was never one of the chief slaveholding states.

Page 12

In 1860 when the slave population was at its peak, North Carolina had only 331,059 slaves compared to Virginia's 490,865; South Carolina's 402,406, and Georgia's 462,198. Of the ten states threatening to secede in 1850, North Carolina ranked eighth in the ratio of slaves to whites. There were 52 slaves in North Carolina to every 100 whites, 53 in Virginia, 91 in Georgia, 105 in Mississippi and 140 in South Carolina.

As early as 1715, there were signs of antislavery movements in the State. The poor "Negro" had aroused the sympathy of a few free thinkers, and many slaves were liberated in this period by kindhearted masters. The philosophy of the American Revolution which held that all men have certain natural and inalienable rights undoubtedly increased the number of sympathetic supporters of the antislavery movement. The heritage: religious, cultural, economic, social, and love for freedom of the North Carolina population revolted against and frowned on slave-holding. In 1830, newspaper editors, professional men and political leaders occasionally went on record as opposing slavery.

As a result of the antislavery movements and the efforts of sympathetic friends quite a few slaves gained their freedom. This brought about another problem, the status of the free Negro. As in other southern states there was no place for free Negroes in North Carolina because they made slave discipline a problem and created a social and economic problem. The predominant attitudes toward free Negroes were those of suspicion and distrust. In 1860, North Carolina's free Negro population was 30,643, a number exceeded in only one southern state, Virginia, and four northern states, New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Ohio.

The free Negro population increased from 1790 until 1830, when restrictive measures of the Legislature made manumission almost impossible and actually drove some free Negroes out of the State. However, with all of its restrictions, North Carolina was a haven for the free Negro from neighboring states because the laws, attitudes and mores were conductive to their settling here.

A large number of industrious slaves bought their freedom, while others gained theirs through manumission. The first law of North Carolina concerning emancipation of slaves, which seems to have been enacted in 1715, directed a master to free a slave only as a reward for faithful service. This law directed the slave to leave the province within six months or to be forced into slavery for another five years.

Page 13

In studying the history of the Negro in North Carolina, one may ascertain that the State did not officially lend support to any colonization effort. However, the Quakers and American Colonization Society played important roles in the antislavery movement.

The free Negro was protected by the courts from hereditary enslavement and heavy penalties were invoked for violating the freedom of Negroes. In one case a sentence of death was given to a white man for selling a free Negro. The 19th Century opened with three important laws in force restricting the freedom of the free Negro. These curtailed his relationships with the dominant race, his mobility, and his association with slaves.

Until 1835, free Negroes of North Carolina enjoyed the privileges of voting if they could qualify as voters under the Constitution of 1776. The Constitution prior to 1835, had permitted anyone to vote who had a freehold of 50 acres, they could cast their votes for senators or upon the payment of common taxes vote for commoners or members of the House of Representatives. The State Constitution of 1776 gave the voter status of a freeman, a term simple enough to admit a free Negro to the voting privilege if he were qualified in other respects. The Constitutional Convention of 1835 was so strong against free Negroes voting that it was among the earliest bills considered. There had been two previous attempts to prohibit free Negroes from voting. As early as 1804, a bill arose in the Senate to prevent free Negroes from voting, and in 1809 a bill arose in the House, which if passed, would have denied the privilege of voting to slaves thereafter liberated. The crisis was reached and the issue settled in 1835, when the resolution to deprive the free Negro of suffrage carried by a vote of 65 to 62. Many controversies and heated battles of words were waged because of this issue.

Although the predominant attitude of the time was hostile to the Negro, and attempted to keep him in a subjugated status in the social, political, and economic life, there were flashes of liberalism manifested throughout the period in the State. In North Carolina it is believed that the free Negroes and slaves at large enjoyed more privileges than in most of the other southern states.

Page 14

CHAPTER II

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE POPULATION

The Sixteenth Census of the United States (1940) gave North Carolina a total population of 3,571,623 individuals. Of this number 981,298 were classified as Negroes. Although this is an increase numerically over the previous census reports, the Negro population has been steadily declining in its relation to the total population. A constant decrease in the percentage of the Negro population over decades stirs and challenges the imagination. It raises some pertinent questions. What are the forces back of the decrease in Negro population? What is happening to the North Carolina Negro? Where is he going and most important--why?

The presence of any minority group for a continued period of time, living within, and at the same time apart from the other groups of the community will create many problems. Especially is this true if this group becomes biologically and economically assimilated at a slower rate than any of the other groups. The group's attempts at adjustment raise special problems that are not common to the other groups. When two groups live side by side in the same community but at different cultural or economic levels social problems occur which are reflected through every phase of their lives.

The mere presence of a race of different biological characteristics creates an acute social problem because these individuals have the same hopes and ambitions to adjust themselves to the existing social structure as the other members of the community. However, they may be denied access to the existing advantages or necessities of life because of their biological differences. In many instances they begin to migrate in search of the opportunities to live as others or as the majority group whose culture and standards they have accepted.

FACTS ABOUT THE POPULATION

1. According to Federal Census of 1940, 275 out of every 1,000 individuals in North Carolina were classified as Negroes.

2. Although the Negro population has been steadily increasing, its percentage in the total population is decreasing.

3. Between 1850 and 1940 the total Negro population trebled itself. The greatest increase occurred from 1890-1940.

4. The percentage of white population in relation to the total population has increased throughout the years. In 1850,

Page 15

the white population constituted 63.6 per cent of the total population; in 1890, it constituted 65.2 per cent of the total population; and in 1940, it was 71.9 per cent.

5. In 1940, there were nine counties in North Carolina in which Negroes constituted more than 50 per cent of the total population--Scotland, 50.2 per cent; Granville, 51.0; Edgecombe, 54.2; Halifax, 56.7; Bertie, 56.8; Hoke, 57.9; Hertford, 59.1; Northampton, 62.0; and Warren, 65.3. All of these counties excepting Hoke and Scotland are located in the eastern or coastal region near the Virginia line. The other two are located in the extreme middle south near the South Carolina border.

6. There are 24 counties in the western section of the State with Negro populations of less than 10 per cent of the total population. Some of these counties are Cherokee, 1.0 per cent; Madison, 1.0; Yancey, 0.9; Mitchell, 0.4; Avery, 1.9; Macon, 2.9; Jackson, 2.9. Graham County had only one Negro according to the 1940 Census Report.

7. The bulk of North Carolina's Negro population is concentrated in approximately 47 counties located in the central and eastern sections, while one-fourth of the State contains less than one-fifth of the race.

8. Historically the Negro of North Carolina is a rural dweller. In 1920, about 80 per cent of Negroes lived in rural areas, while in 1940, 70 per cent lived in rural areas. The white population had 74 per cent of its members living in the rural areas in 1940.

9. Females exceeded males for the State in both races. The Census showed there were 98.6 males to every 100 females. There were 99.7 white males for every 100 females and 95.7 Negro males to every 100 Negro females. These data are important because the ratio of males to females influences the birth rate of the group.

10. According to the 1940 Census, there were 25 cities in North Carolina with populations from 10,000 to 100,000, and one with more than 100,000. These 26 cities had a total Negro population of 243,037.

11. In 1940, there were 974,175 individuals classified as urban dwellers in North Carolina. Of this number 299,363 or 30.7 per cent were classified as Negroes and 69.2 per cent as whites; in 1930, Negroes constituted 30.4 per cent of the urban population and the whites 68.3 per cent.

12. Negroes have decreased in farm population from 1910 to 1940, and whites have increased. In 1940, Negroes constituted 29 per cent of the farm population compared with 69.8 per cent for the white; in 1930, Negroes constituted 31.1 per cent of this group and the whites 67.9 per cent; but in 1910, the Negro was 31.2 per cent of the farm population and the white group 68.1 per cent.

Page 16

Fig 1.--NEGRO POPULATION IN NORTH CAROLINA 1850-1940, RATE PER 100 WHITES

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census.

Page 17

13. In 1940, children under 5 years of age amounted to 10.1 per cent of the white population, and 11.5 per cent of the Negro population.

14. According to the 1940 Census, the percentage of Negroes in every age group under 25 was higher than the whites and lower than the whites in every age group 25 years and over.

15. The enumeration of 1940 Census also pointed out that 11.0 per cent of the Negroes in the urban area were in the age group from 25 to 29 years of age; while there were 8.9 per cent of the group in the 30 to 34 age group; in the age group 35 to 39 was found 8.4 per cent of this area; the 40 to 44 age group contained 6.3 per cent of the Negro inhabitants classified as urban.

Seven and one-tenth per cent of the farm population was in the 25-29 year age group; 4.6 per cent in the 35-39 age group; 3.9 per cent in the 40-44 age group.

16. There is an excess of females relative to males in all age groups under 50 years. The excess of the females in the age range 15-30 was the greatest. These are the years of early maturity. The white population follows the same trend as the Negro in proportion of males to females.

17. North Carolina's Negro population is younger than the white population, but does not live as long.

18. The Negro population of North Carolina is largely native-born American, and only affected slightly by foreign Negro immigration; therefore its composition is a natural one determined largely by its birth and death rate.

Page 18

CHAPTER III

EARNING A LIVING

No one can deny the fact that the job or sources of incomes for maintenance is all important to any group. To an economically poor group the job is the Alpha and Omega of its existence. Just to survive demands that this group seek the surest means of providing some kind of a livelihood. It may be conservatively stated that the type of job an individual is able to secure plays an important role in the other aspects of his life. In many instances, the type of job determines the individual's income and the income profoundly affects the standard of living he maintains or determines whether the individual is able to secure the necessities of life.

The Negro occupies an unfavorable position in the economic system of the country at large. In the employment field, he is circumscribed, segregated, and discriminated against to a greater extent than other members of the general population. There is a marked division of labor when it pertains to the group; it has not received its share of skilled, supervisory, managerial, public and governmental positions in its attempts to earn a living. The generally accepted and traditional patterns have had the tendency to concentrate the bulk of the group in the most unremunerative and insecure occupations of semiskilled or unskilled labor. The Negro has to find employment out of sheer necessity to exist. Sometime he does not find it at all; however, at the same time he stands in the greatest need of employment that will give him the best remunerative returns. Yet he is often forced to accept the type of employment which gives the least returns and with a minimum of opportunities for promotions and improvement of his conditions.

The Negro professional group represents the upper social and economic level of the race's population. This group is usually the mouthpiece or voice of the masses and is invariably called upon by the dominant group to represent the total Negro population. This group sets the standards and pace of the so-called social life for the race. Those who are not fortunate enough to be in this group usually attempt to pattern after them as much as possible. The professional group occupies a position of leadership and prestige. As Dr. Ira De A. Reid has often pointed out, the white collar and professional group are the "best people" who send their children to college and professional schools. Usually they

Page 19

are fairly well educated and most of their education is directed toward white collar occupations.

When the employment opportunities and conditions of North Carolina's Negro population are considered, how do they compare with those of other segments of the population? What types of jobs are allotted to Negroes? What are their chances for promotion and improvement? What are the effects on their personalities? These questions may be argued pro and con but the fact still remains the job is vitally important to an economically poor group.

FACTS ABOUT EARNING A LIVING

1. In 1940, there were 2,491,830 individuals 14 years and over in North Carolina. Of this number 1,333,773 were in the labor force.

2. There were 658,489 Negroes in the labor force, or 572 Negroes out of every 1,000 Negroes.

3. The Census report showed that 332,359 Negroes were gainfully employed excepting public emergency work; 13,172 were employed in public emergency work which included WPA and NYA; 31,729 were seeking work.

A--AGRICULTURE

4. North Carolina is largely a rural State, and the bulk of its Negro population earns a living from the soil. Of every 1,000 gainfully employed Negroes 14 years of age and over in 1940, 412 were engaged in some form of agriculture. Of every 1,000 whites in the same age category, 303 were engaged in agricultural pursuits.

5. Of every 1,000 white females 14 years of age and over gainfully employed 43 were in some form of agriculture, while 168 out of 1,000 colored females in the same age group were engaged in this occupation.

6. The 1940 statistics for agriculture pointed out that there were 57,428 Negro farm operators in the State. This included owners and tenants of all types. In 1930, there were 74,636 colored farm operators and in 1920, the number was 74,849. These figures indicate that there has been a decrease in the number of Negro farm operators in the past two decades while the white operators have increased over the same period.

7. The farm land utilized by the colored farmers in 1920 totaled about 3,370,191 acres; in 1930 it totaled 3,296,445 acres; however, in 1940, the acreage had decreased to 2,728,997 acres.

8. The valuation of all colored-owned farm property and buildings in 1920 was estimated at $233,666,166. In 1940, the farm property and buildings were valued at about

Page 20

$106,293,392, a decrease of over a million dollars in the two decades. The valuation of the farm lands and buildings of the white population increased over the same period of time.

9. Between 1940-43 the Farm Security Administration increased its Negro professional personnel from two to eight persons, four male assistant agricultural supervisors and four female assistant home management supervisors. These persons were located in Person, Caswell, Halifax and Robeson Counties.

10. Between 1920 and 1943, the Cooperative Extension Service of the State increased the number of Negro Farm agents from 12 to 38. The Home Demonstration agents increased from 6 in 1925 to 25 in 1943. The Farm and Home Demonstration agents are located in 38 counties.

11. In 1943, there were 89 colored vocational agricultural teachers located in high schools in 54 counties, to teach and stimulate an interest in agriculture in high school students and adult farmers in their respective patronage areas. There were approximately 3,000 colored youth enrolled in the New Farmers of America.

B--SOME OTHER ASPECTS OF EMPLOYMENT

12. North Carolina's colored population is a working population. In 1940, they constituted 27.5 per cent of the total population. Of the total population gainfully employed 33.9 per cent were Negroes.

13. Of every 1,000 Negroes 14 years of age and over 572 worked for a living, while for the total population of the same age group 535 of every 1,000 worked.

14. In the total population, 277 out of every 1,000 women 14 years of age and over worked but 359 in every 1,000 Negro women of this age worked.

15. The gainfully employed colored workers were distributed as follows in 1940: 136,854 or 41.2 per cent in agriculture; 82,746 or 24.9 per cent personal and domestic services; 46,525 or 14.1 per cent in manufacturing. Approximately 80.1 per cent of all the gainfully employed colored workers were in the aforementioned occupations, while about 66.1 per cent of the white gainfully employed were engaged in these occupations.

16. Eight and four-tenths per cent of the total colored persons in the labor forces were unemployed or seeking work in 1940; and about 4.2 per cent of the whites were in the same category. In proportion to their total numbers in the labor forces there were about twice as many colored males and females seeking employment as whites.

17. Out of every 1,000 Negroes 14 years of age and over in labor forces, 34 were employed in emergency work while 42 whites were in the same category.

Page 21

FIG. 2--PERCENTAGE OF NEGRO AND WHITE WORKING POPULATION ENGAGED IN SPECIFIED TYPES OF OCCUPATIONS, 1940

Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census

18. The growing and manufacturing of tobacco is one of North Carolina's principal sources of employment and revenue. According to the 1940 Census, there were 21,489 individuals engaged in the manufacture of tobacco products. Negroes constituted 54.9 per cent of the total number employed in this industry.

19. Forty hours per week was the maximum number of hours recommended by the experts in the labor field. Yet the Census records showed that during the week of March 24-30, 1940, 52.6 per cent of the Negroes who were working

Page 22

at that time worked over 40 hours per week; and 34.2 per cent worked over 48 hours per week.

20. The 1940 Census shows that in 1939, 50.8 per cent of the salary or wage earning colored persons of the State worked 12 months; 18.8 per cent worked 9 to 11 months; 16.6 per cent worked 6 to 8 months; 8.2 per cent worked 3 to 5 months; 2.6 per cent worked less than 3 months; and 3.1 per cent were out of work for this year.

21. The greatest difference in the employment of the races is in the types of occupation. The majority of colored persons were employed in agriculture, domestic service, unskilled or semiskilled jobs. The whites were employed as clerks, officials, managers, proprietors, and skilled workers, They received salaries for their employment more adequate to maintain a decent standard of living. Negroes engaged in the unskilled jobs receive the lowest remuneration; therefore, they were unable to maintain the generally accepted standard of living.

C--THE PROFESSIONAL GROUP

22. Both colored and white professional classes constituted a small percentage of the total employed population in 1940. In the Negro population 4.6 per cent of the gainfully employed persons were rendering some type of professional service; in the white population the professional group covers 5.6 per cent of the gainfully employed.

23. Negro school teachers constituted 2.1 per cent of the gainfully employed and ministers 0.3 per cent; while the whites had 2.3 per cent of its professional group in the teaching profession and 0.3 per cent in the ministry.

24. In 1940, there were 26 Negro lawyers practicing, and 49 individuals employed in some form of social work.

25. North Carolina is the home of the world's largest Negro business, the North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance Company. The company employs personnel numbering about 802 persons, of whom the majority are in the white collar class. The Winston Mutual Life Insurance Company and Southern Fidelity Mutual Insurance Company are located in the State also. The Mechanics and Farmers Bank, the only Negro banking institution of the State, located in Raleigh and Durham, reported total assets $2,329,354.21 and total liabilities the same at the close of the business year June 30, 1943.

26. About 6.6 per cent of the gainfully employed colored females were in the white collar jobs or professional positions.

27. Out of a total 63,769 proprietors, managers, and officials there were 2,316 Negroes employed in these occupations. Negro eating and drinking enterprises numbered 453.

Page 23

There were 53 mail carriers, the majority of them employed in Wilmington, Raleigh, Goldsboro and Fayetteville.

28. Negro business providing services largely to the colored population, such as barbers, beauticians, manicurists employed 1,310 individuals or 0.4 per cent of the gainfully employed.

29. The bulk of the business enterprises operated by Negroes were the retail trade and service areas of barber shops, pool parlors, beauty shops, small grocery stores, pressing clubs, shoe repair shops, and undertakers. These are the only fields or areas of business which the race has been able to operate with any degree of success. Due to the lack of adequate capital Negroes have been unable to compete with the chain stores and the business enterprises operated by white competitors usually found in Negro districts. Usually these business enterprises are operated by Jews and Greeks or whites of recent foreign extraction who have come to the country and settled in Negro areas.

Page 24

CHAPTER IV

HOMES AND FAMILIES

The home-life of the Negro is filled with many complicated social, economic, and cultural problems. The majority of the homes occupied by Negroes are dreary dwellings, in neglected streets and rundown neighborhoods, without pavement and adequate lighting facilities and located in the most undesirable section of the city, or the poorest land in the rural areas. From New York to Los Angeles, Atlanta to Detroit, New Orleans to Chicago, Raleigh to St. Louis, Negroes live in the most deplorable conditions in the most undesirable locations and substandard homes. These conditions are not confined solely to the urban areas but those homes occupied by Negroes in the rural areas present as formidable a picture as the ones in urban areas.

It is a generally accepted theory that the family is the oldest and most universal institution known. The family and home have been the basic social agencies for human survival and continuation; they also assist in the molding of the individual's character and play a profound role in the lives of most persons more so than any other institution of our present society. The family and the home are inseparable and each must be considered as important because of the influence it wields on the individual.

The democratic and American way of life are predicated upon the rights of the individuals and family life. The question may be raised, what view of the sanctity of the home and family life could Negroes be expected to entertain when almost every external and internal force has been against them developing and enjoying wholesome family and home life? When the things which are necessary to make up good home and family life are considered the question answers itself.

Practically everyone will agree that the Negro neighborhoods or areas of the cities are blighted areas with higher rates of juvenile delinquency and crime than other sections of the cities. When it comes to the paying of rent, the group is charged higher rates in relation to the type of housing they occupy and their ability to pay.

If the Negro desires to move, he is usually unable to do so because of his low economic status, shortage of available housing or neighborhoods in which he is admitted; also legal restraints, mores and traditions keep him relegated to circumscribed areas.

Page 25

Whenever there is an influx of Negroes into a white community the whites move out, the rents go up, and the neighborhood generally deteriorates.

Housing is intricately interwoven with the economic status, personality, and health of any group in the American system. Such problems as illegitimacy, desertion, health, crime and other aberrations from the socially accepted pattern are high in the Negro group. Sometimes this is due to a large percentage of the group being unable to secure profitable employment and this fact deters them from securing decent houses in the better neighborhoods. The mere presence of poverty is often reflected in a disorganization of the individual which affects the entire family. Sexual promiscuity is often found among the low income groups in congested areas and substandard houses because of the lack of privacy of members of the family. In the average Negro home rural or urban there is an absence of many of the fundamental necessities for a minimum standard of economic and cultural decency.

With all of the restrictions and conditions brought to play upon it, the Negro family and home life in North Carolina, has made progress and improved its conditions. However, there is a real need for more active participation of the group in community life as a whole. It has been pointed out by some alarmists that Negro family life has deteriorated, because of the increasing number of divorces and the high rate of illegitimacy of its members. In proportion to their number, the divorces obtained by members of Negro families may be considered a healthy sign. It shows the recognition of the custom of marriage which was not done to any great extent in the past decades, the main method of securing a divorce was not by legal procedure but the poor man's--desertion. The future of the Negro family in North Carolina depends upon the economic status, the availability of housing and the conditions of the neighborhoods surrounding this housing.

FACTS ABOUT HOMES AND FAMILIES

1. According to the 1940 Census, there were 794,860 families in North Carolina. There were 205,240 classified as Negro heads of families and 581,600 heads listed as native whites; while the remaining 8,020 were foreign born whites and other races.

2. Out of every 1,000 persons 15 years of age and above there were:

Page 26

| Single | Married | Widowed | Separated or Divorced | |

| Negro Men | 386 | 565 | 44 | 5 |

| White Men | 330 | 635 | 29 | 6 |

| Negro Women | 309 | 549 | 134 | 8 |

| White Women | 271 | 623 | 97 | 9 |

3. White youths marry younger than Negro youths. Of every 1,000 white youths between the ages of 15-19 years old in 1940, 28 were married; of every 1,000 Negro youths in the same age group 24 were married. Within the same age group 159 out of every 1,000 white girls were married and 138 out of every 1,000 Negro girls were married.

4. The value of real property owned by North Carolina's Negro population in 1940 was $39,069,126, with an average value of $826 per person, compared with $523,675,650 for the white population and an average value of $2,071 per person.

5. The bulk of owner-occupied dwellings for non-whites, of which Negroes constitute about 95 per cent, was valued at less than $300.00 each. About 24.6 per cent of all owner occupied dwelling for non-whites compared with 10.1 per cent for whites were in the less than $300 value range. Non-whites did not own any property exceeding $10,000 to $14,999.

6. The median gross rent rate for the State in 1940, was $14.49 for the urban and non-rural farm areas. The median gross rent for the whites for these areas was $16.37 compared with $12.05 for the non-white living in the same areas. (Farm homes excluded.)

7. Out of every 100 private Negro households 24.2 kept lodgers, while 11.9 of the white households kept lodgers.

8. Three-fourths of the Negroes of North Carolina were tenants in 1940, and one-fourth were owners or part owners of property.

9. Of the 204,401 dwellings occupied by non-whites in 1940, 192,203 units reported need of repairs. Of the 192,203, 101,588 (52.9 per cent) reported did not need any major repairs; and 90,615 (47.1 per cent) needed major repairs.

10. The occupied units by size of household in 1940, revealed that the median number of persons for the State was 3.99 for each dwelling. The non-white owner occupied units (4.20) was larger than that of the whites (3.97). For the units occupied by tenants the median number of persons was 3.98; as in the owner occupied units the non-white 4.18 was the median number of persons to each unit, while for the whites in the same category it was 3.19.

11. In the report on refrigeration equipment the whites exceeded the non-whites in both owner and tenant groups.

Page 27

FIG. 3--MEDIAN SIZE OF FAMILIES, BY RACE, 1940

Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census.

FIG. 4--MEDIAN MONTHLY RENTAL,*

* Exclusive of farm homes.

BY RACE, 1940

Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census.

Page 28

| Total | Mechanical | Ice | Other | None | |

| White | 1,000 | 306 | 227 | 37 | 430 |

| Non-White | 1,000 | 22 | 230 | 61 | 687 |

12. A most revealing discovery was the small number of Negro homes having modern conveniences. Out of every 1,000 homes occupied by Negro owners 357 had electricity for lighting and 628 used kerosene or gasoline. For the tenant occupied units 264 out of every 1,000 had electricity and 720 used kerosene or gasoline.

13. The Federal Housing Authority with the county and city have constructed permanent low rent housing facilities for about 1872 Negro families in seven cities in North Carolina. These projects are located in the following cities: High Point, New Bern, Wilmington, Kinston, Charlotte, Fayetteville, and Raleigh.

Page 29

CHAPTER V

HEALTH

Health is one of the most serious problems of North Carolina's Negro population because it has a profound effect on the education, efficiency, and economic status of the group. The North Carolina Negro has a higher birth rate, sickness rate, and death rate than found among the white population. One may ask, why are morbidity and mortality rates higher among Negroes than whites? Are there biological or racial differences which are responsible for these conditions? The answer to this is no, and only the naive would accept such a solution to the problem of ill health. Whenever the Negro is studied in his composite setting and his standard of living and earning capacity are considered in relation to the total situation, this represents a different picture because these two vitally important items are below those of the white population and profoundly affect the group's health status. These existing conditions are conducive to the Negro being ill-fed, ill-clad, and ill-housed. It has been stated that "Often people are sick because they are poor and poor because they are sick." This statement may be applied to any group but it is of special significance to the Negro and his condition.

The existing health and medical facilities, and services, their distribution and location, also the standards maintained in the field of health, are reflected in the vital statistics of the total population; especially is this true of the Negro. The majority of the counties in North Carolina have some type of free health and medical services provided for those who are unable to pay for them. However, the access to health and medical facilities varies greatly according to the races and to the location. So despite the fact that both whites and colored are living under similar natural conditions, there are differences in the health and medical facilities available for treatment, ability to pay for these services which may be available, and access to these facilities.

FACTS ABOUT HEALTH

1. In order to appraise correctly health conditions and the need for health programs the starting point should be in the field of vital statistics. The 1940 report of the Bureau of Vital Statistics showed that there were 81,487 resident births in North Carolina (exclusive of stillbirths). Of this number 55,340 were white and 25,312 were colored.

Page 30

The birth rate for the white population was 21.4 per 1,000 compared with 26.3 per 1,000 for the colored.

2. The resident births exceeded the resident deaths in 1940. There were 81,487 births compared with 31,364 deaths or about 2½ times more births than deaths.

3. In proportion to their numbers in the total population Negroes exceeded whites both in the number of births and deaths. The death rate for the State in 1940, (exclusive of stillbirths) was 8.8 per 1,000; for the whites it was 7.6 per 1,000 compared with 11.6 per 1,000 for the Negroes.

4. The sickness and death rates of Negroes from tuberculosis, malarial fevers, syphilis, nephritis, and pneumonia are high when compared with the white population's.

5. In 1940, the chief cause of death among both races was heart disease. For diseases of the heart, the death rate among white persons exceeded that of colored persons. Heart disease was the cause for 15.5 per cent of all of the deaths for white persons compared with 13.1 per cent for colored persons.

6. The death rate from cancer and other malignant growths, intra-cranial lesions of vascular origin, congenital malformations and debility, premature birth, and diseases peculiar to the first year of life in 1940, was twice as high among whites as colored.

7. Deaths from tuberculosis, syphilis, and malaria were about 1½ times as frequent among Negroes as whites; while the deaths from homicide were twice as high among Negroes as whites.

8. Deaths for both white males and females exceeded those of colored in the age range under 1 year to 14 years of age. Between the ages of 15-54, Negro males and females exceeded those of the white.

9. Negro deaths from influenza constituted 2.2 per cent of the total deaths for the group while for whites it was 1.9 per cent. Pneumonia accounted for 7.0 per cent of the total deaths of colored persons compared to 4.6 per cent for white persons. In proportion to their numbers in the total population, these ratios were high for the colored.

10. Tuberculosis is a major cause of death in the Negro population of North Carolina. For 1940, the death rate from all types of tuberculosis for colored exceeded that for the white by 6.6 per cent. Tuberculosis was responsible for 8.8 per cent of the colored deaths and 2.2 per cent of the white deaths or 4 times higher among Negroes than whites.

11. The occurrence of death as a result of syphilis is exceedingly high among Negroes. The 1940 statistics indicate 2.8 per cent of the total deaths among colored persons in North Carolina were due to syphilis compared with 0.4 per cent

Page 31

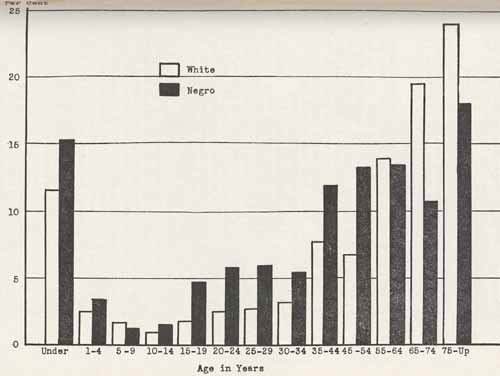

FIG. 5--PERCENTAGE OF ALL DEATHS AMONG FEMALES, DUE TO TUBERCULOSIS, BY AGE AND RACE, 1940

Source: N. C. State Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

Page 32

for the corresponding reason among white persons. Although the disease is imperfectly reported, the data indicate that the death rate for Negroes was about five times that among the whites.

12. Death as a result of suicide is much lower among Negroes than whites. In 1940, the vital statistics show that there were 266 deaths among white persons as a result of suicide compared with 25 deaths among colored individuals for the same reason, or the white deaths were approximately 10½ times as high as the Negro deaths.

13. Of the total deaths, the highest number occurring among the white males was in the age group 65-74. Here was found 19.6 per cent of the deaths in 1940. For the age group under 1 year, was found the largest number of deaths for colored persons. Deaths in the age group of less than 1 year are lower among both Negro and white females than males in the corresponding group. In the 15-19 age group, Negro female deaths exceeded the white females, while the white male deaths were higher than Negro male deaths in the corresponding group.

14. There is a lack of adequate hospitals for both white and colored persons. In 1940, there was one white physician to every 1,127 white persons compared with one Negro physician for every 6,499 persons. There was one white dentist to every 2,965 white persons, and one Negro dentist to every 13,629 colored persons. However, this does not mean that Negroes must go without the services of competent and efficient physicians because in many areas of the State, white physicians have a large percentage of Negro patients; this is also true of the dentists.

According to the statistics of the North Carolina State Board of Health on the employment of public health nurses, there were 312 white nurses and 33 colored nurses. This includes white nurses employed by the Farm Security Administration, Community Chest and Tuberculosis Association, and Negro nurses employed by the Farm Security Administration and Community Chest. The ratio of white public health nurses to the white population was one for every 7,974 inhabitants compared with one for every 32,302 Negroes in the population.

There were 166 optometrists, 162 chiropractors and 138 veternarians among the whites. There were not any Negro optometrists, chiropractors or veterinarians listed.

15. The North Carolina Tuberculosis Association's statistics showed that there were 846 beds available for Negro patients and 1,303 for white patients in 1943. If these figures were based upon the proportion of each group to

Page 33

FIG. 6--PERCENTAGE OF ALL DEATHS AMONG MALES, DUE TO TUBERCULOSIS, BY AGE AND RACE, 1940

Source: N. C. State Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

Page 34

the total population, the Negroes had a high percentage of available beds for treatment. However, if these facilities were based upon the mortality rates for the race, the facilities for Negroes were found to be woefully inadequate.

Page 35

CHAPTER VI

EDUCATION

According to the 1940 Census, there were approximately 107,588 persons in North Carolina 10 years and over, who had not completed one year of schooling or who may be classified as illiterate. Of this number about one-half were non-white of which 95 per cent were classified as Negro. These data indicate that illiteracy among Negroes and whites was about equal in numbers; however, in proportion to their numbers in the total population the rate of illiteracy was higher among colored persons than whites.

Although North Carolina's public education program is predicated upon separate schools for its three races, whites, Indians and Negroes, it has earned a reputation of having one of the most progressive public school programs and systems in the South. Especially, is this true of Negro education. The State's reputation for its school program for the colored population has received nationwide recognition. The problem of public education in North Carolina is not one of race alone but of inadequacy of funds. The report of the National Resources Planning Board "Regional Planning--The Southeast" points out that North Carolina ranks among the lowest in states according to ability to finance public schools.

In North Carolina there are more institutions for the higher learning of Negroes than in any other State in the United States. There are twelve institutions of higher learning for the race. Five of this number are State supported and are as follows: North Carolina College for Negroes, Durham; Agricultural and Technical College, Greensboro; Winston-Salem Teachers College, Fayetteville State Teachers College, and Elizabeth City State Teachers College.

In many instances, the training and education of the individual determine the employment opportunities that are available to him, and the type of job he will be able to secure, determines his income, which profoundly affects the standard of living and health status, he is able to maintain. Then it is easy to see that the pursuit of education and training and the general welfare of the Negro are intricately interwoven. From the following statistics may be ascertained some index or indication of how the Negro compares with other members of the population in his pursuit of training and education, how he utilizes the available

Page 36

resources, some of the things that have been done by the State for him in this field, and the future trends in education for the group.

FACTS ABOUT EDUCATION

1. The average value of the property in the United States in 1940-41, per student enrolled was $300.00; the average value of property in North Carolina per pupil enrolled was $136.51; the average value of property per white pupil enrolled was $171.30, for Negroes it was $57.42.

2. In the matter of appraised value in school property per pupil enrolled, North Carolina does not rank so high. This is due in a large measure to the low value of school property used by Negroes.

3. The average training of Negro teachers in 1941-42, compares favorably with that of the white teachers. The white teachers had a rating of 792.8 per cent and the colored teachers 776.4 per cent. In this index of training 700 means four years of accredited high school and three years of a standard college. Graduation from a standard college with required professional training would be indicated by the index of 800.

4. There is a relatively small number of teachers with less than two years of college training in either race in North Carolina. The State ranks highest in seven Southern States which include Alabama, South Carolina, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee in educational background of teachers. In this same group, North Carolina ranked lowest in the per cent of teachers with less than two years of training. In the training which exceeded five years, the white teachers had a higher score than the colored teachers with 17.5 per cent of those in this group compared with 1.3 per cent for the Negroes. With those who had less than two years of training the white teachers had a lower per cent than the Negroes, they had only 0.9 per cent while the Negroes had 5.2 per cent of this group. All indications are that North Carolina has a competent and well prepared corps of teachers in both races for the instruction of her children.

5. The average teacher pupil load in North Carolina's elementary schools in 1940 was 32.5 for each white and Negro teacher. In the high schools the Negroes exceeded the whites with an average teacher load of 27.0 for each teacher compared with 24.2 for the whites.

6. In the percentage of average daily membership in average daily attendance, the white pupils attendance for elementary schools was 93.8 per cent while the average daily attendance for Negroes was 90.3 per cent; for high schools the white pupils average daily membership in daily attendance was 95.2 per cent and Negroes 93.7 per cent.

Page 37

FIG. 7--PERCENTAGE OF CHILDREN ATTENDING SCHOOL, BY AGE AND RACE, 1940

Source: U. S. Bureau of the Census.

7. The high school attendance for Negroes in North Carolina has increased during the past two decades. In 1923-24 the Negro high schools had an enrollment of 4,715 pupils; in 1930-31, the enrollment had increased to 16,817. The 1940-41 enumeration indicates the enrollment had almost trebled itself with 42,789 in attendance.

8. In 1943, the Legislature authorized a school term of 180 days or 9 months for all children of all races in North Carolina.

9. The course of study and requirements of accreditment in elementary and high schools are the same for all of the

Page 38

schools of the State. The program for training and certification of teachers of all groups is the same.

10. The most belated item in the entire North Carolina school program is the large number of small units of Negro schools. The 1943 statistics pointed out that there were about 1,600 of the small outdated, outmoded, and in several hundred cases, very dilapidated, uncomfortable, poorly furnished, one, two, and three teacher schools.

11. In 1943, there were 586 accredited elementary schools for the white population and 26 for the Negro; there were also 728 accredited high schools for the whites and 185 for the Negroes.

12. North Carolina has a compulsory school attendance law for all children between the ages of 7 and 14 years of age.

13. North Carolina's Negro population sends to school a larger percentage of its total population of children and youth between the ages of 7-14 than the whites in this age group. According to the 1940 Census there were 178,966 Negroes in the age group 7 to 14 years of age. Of this number 161,773 or 90.4 per cent of the total population of this age group attended school compared with a total population of 438,050 whites of which 386,438 or 88.2 per cent of this group were attending school. In the age range of 7 to 21 years, 63.5 per cent of total Negro population in this age group attended school compared with 64.3 per cent of the white population in the same group.

14. In the field of vocational or technical education, North Carolina does not present such a favorable picture for either race. In 1943, there were approximately 90 instructors or teachers of trades in North Carolina, of this number 33 were Negroes.

15. In 1943 there were ten Negro schools with programs of diversified occupations, directed by coordinators which attempted to train students in industrial education.

16. The North Carolina General Assembly of 1939 provided graduate training for Negroes in two ways:

- (a) Within the State and leading to the master's degree, in liberal arts and the professions at North Carolina College for Negroes, Durham; in agriculture and technology, at Agricultural and Technical College, Greensboro.

- (b) For more advanced graduate work in some subjects which could not be immediately offered in the two above named institutions, fellowship aid was provided for those who desired to study in institutions outside of the State.

17. The 1943 Legislature appropriated a total sum for Negro public schools for the biennium 33⅓ per cent above the appropriations for the same schools for the Biennium 1941-42.

Page 39

- (a) In 1939-40, the appropriation was $6,516,116.

- (b) In 1940-41, the appropriation was $7,263,362.

- (c) In 1942-43, all data not compiled but estimated by chief statistician of the State Department of Public Instruction $8,500,000.

18. North Carolina is making a conscientious effort to reduce the differential in salaries between white and Negro teachers. Beginning in 1939, $118,000 was allotted to increase the salaries of Negro teachers. Each year since that time a quarter of a million dollars have been provided for the same purpose. Provisions were made by the 1943 General Assembly for a similar amount for each of the next two years, 1943-45. By 1945, it is expected that the salaries of all teachers will be the same.

19. In 1930-31, there were 1,370 schools reporting public and private libraries for white and colored elementary and high schools in North Carolina. Of these 1,304 were for white schools and 66 were for colored schools.

20. These libraries reported a total of 554,977 books, with an approximate circulation of books in the schools of 1,970,734. The circulation among the white school population was 1,913,371 compared with 57,363 for the colored population.

21. The number of books per pupil for the State was 2.8 per cent in 1930-31. The ownership per pupil for the colored was 1.9 per cent and for the white 2.9 per cent. Each white pupil owned an average of 1 more book than each colored pupil.

22. The school library statistical report of 1930-31 reported 264 teachers with library training. Of this number 245 were white and 19 colored.

23. There has been a rapid increase in the library facilities of North Carolina for both races since 1930-31. The 1941-42 statistics pointed out that 2,241 or almost twice as many schools reported libraries. In 1930-31 only 66 Negro schools reported libraries but in 1941-42 there were 414 or about six times as many.

24. The schools for both races reported 2,212,560 volumes for 1941-42, which is an increase of 1,657,583 volumes since 1930-31.

25. There were 9,107,479 books circulated through the school libraries in 1941-42, compared to 1,970,734 in 1930-31. There were 460,732 books circulated among the colored while the whites had a circulation of 5,296,458 books. The average circulation of books per pupil for the State in 1941-42 was 12.68 per cent; for the white pupils it was 13.93 per cent compared to 7.04 per cent for the colored pupils.

Page 40

26. The 1941-42 statistics pointed out that there were 111 schools with full-time librarians. Of this number 90 were in the white schools and 21 in the colored schools. There were also 579 schools with part-time librarians with some library training. Of this group 407 were in the white schools and 172 in the colored schools. Of the 433 schools with teacher librarians without training 319 were white and 114 colored.

27. According to WPA report on Adult Elementary Education, there were 236,261 illiterate persons of all races in North Carolina in 1930. Between November 1933 and August 1939, 85,666 or 36 per cent of this number were taught reading and writing on WPA projects. Of this number, taught to read and write, approximately 37,506 or 45 per cent were Negroes. In 65 counties approximately 260 Negro WPA teachers were engaged in this program.

28. In 1941-42, the State Aided Adult Education program employed 125 teachers. Of this number, there were 18 colored and 107 white teachers. Approximately 30 were full-time, 5 colored and 25 white, and 95 part-time, 82 white and 13 colored were classified in the latter category.

29. The National Youth Administration attempted to render service and assistance to all youth in need of employment. "It was administered on a fair and liberal basis" was the interpretation of a high ranking Negro employee of the NYA. The program consisted of two parts: the student work program which provided part-time employment paying wages to needy students to enable them to continue their education; and out of school work which gave part-time jobs to youths between the ages 18-24, who had been unable to find work. With the development of the program the age limit was reduced under certain conditions to 16 years. Approximately 22.5 per cent of the total youth enrolled for training during the program's existence in North Carolina were Negroes.

30. In 1937, the Civilian Conservation Corps provided for general education and vocational training in its program. Approximately 20,000 Negro youth received training under this program which assisted them in securing employment after leaving the Corps.

Page 41

CHAPTER VII

RELIGION

The church and religion have wielded a great influence in the induction of the Negro into the American social order and culture, also in the assisting of the race in making an adjustment to them. The church is one of the race's most important and financially strongest institutions. The Negro's church has served for more than just a place of worship but has been the center of most of his social, economic, and cultural life. In attempting to make an adjustment to the existing social and economic system the church and religion have been a haven of refuge from a hostile world to a mass of frustrated people, and served as an outlet for their emotionalism. Without the church and religion, the Negro's early life in America would have been almost unbearable.

A comprehensive study of North Carolina's Negro population would not present a very complete picture unless the church is included. One is compelled to study the church and the influence it wields on the Negroes because their lives are so deeply rooted in this important institution. Most of the early Negroes, especially the slaves, learned to read and write at Sunday school if at all. The churches began an early fight for the abolition of slavery and were the first places of free assemblage for the Negroes in the State.

Today the role of the churches in North Carolina, has not been subject to such drastic changes as in other sections of the country, especially the northern and western areas. Many believe that it is due to the fact that North Carolina is largely a rural state, and the bulk of its Negro population is to be found in small towns and rural areas. The social activities of the church are few and most of them do not have any program of social improvement for their members and the community. Their ministers and membership do not engage in politics or militant movements as in other sections of the country.

Their religion has more of the old time fervor, reverence, and obedience with the emphasis on the after life rather than social changes or improvement for the present life. However, more freedom of expression is permitted in the church and from the preacher than is usual in other places where large numbers of the race may assemble.

Today there is an acute need for the Negro's church to consider and inspect more minutely its program and place more emphasis

Page 42

on the mundane lives of its membership, so that programs may be developed to assist the individuals in making the best adjustment to a highly mechanized social order. These programs should be aimed at the alleviation and correction of the daily social and economic problems of living confronted by the race. Social workers, lawyers, doctors, teachers and other representatives of the various social agencies of the community should be called in to explain their programs.

Higher education in North Carolina for Negroes has been greatly influenced by the church. Before the State assumed the responsibility of defraying the expense for Negro education, the church institutions were operating. Today there are 12 institutions of higher learning for Negroes in North Carolina; seven of them are church schools. They are Shaw University, Baptist; St. Augustine's College, Episcopal; Livingstone College, African Methodist Episcopal Zion; Johnson C. Smith University and Barber-Scotia College, Presbyterian; Bennett College for Women, Methodist; and Immanuel Lutheran College, Lutheran. Most of these institutions were established to educate Negroes for the ministry and stressed the religious aspect or Christian living in their early development.

FACTS ABOUT THE CHURCH

1. As in the other states and cities of the United States, the Negro's church in North Carolina has been and still is one of the most important racial organizations profoundly influencing his social and economic life.

2. North Carolina ranks fourth among the States with its Negro membership in churches, being exceeded by Georgia, Alabama, and Texas.

3. In 1936, North Carolina's Negro population had a total membership of 434,951 or an average of 170 members per church. The average number of Negro members per church for the United States is 280. Whites had a total membership of 839,571. It is exceedingly conservative to state that nearly five out of every ten Negroes in North Carolina are members of a church, compared to about three out of every ten whites. The average membership for all churches white and Negro in 1936 was 159; however, Negroes had an average membership of 170.

4. It has been usually assumed that the Negroes in the rural areas constitute the largest proportion of church membership per church. According to the 1936 enumeration of Religious Bodies, there were 234 members per church in the urban areas compared to 145 in the rural.

Page 43

FIG. 8--NEGRO CHURCH MEMBERSHIP, BY DENOMINATION, 1936

* Others: Lutheran, Holiness, Adventist, Presbyterian, Catholic, Episcopal, and Disciples of Christ

Page 44

5. There was a larger number of females claiming church membership than males. Male membership was 162,253 and female 268,712. In membership, the sexes maintain a ratio of approximately two females to every male.

6. There were 2,562 churches used by Negroes in North Carolina, 716 in the urban areas and 1,846 in the rural areas. The urban churches had a total membership of 167,515, and the rural 267,436 or nearly twice as many members.

7. The Negro's church is the race's largest property owner. According to the 1936 study of Religious Bodies Negroes in North Carolina owned church property totaling $11,204,158 with an average of $4,680.00 per church and an average yearly expenditure of $750.00.

8. In 1936, the Negro Baptists of North Carolina reported a total membership exceeding 219,893; the Methodist bodies reported a membership of 166,033; the Congregational and Christian Churches reported a membership of 11,344; the United Holiness faith reported 4,547 members; Disciples of Christ reported 6,213 members; the Church of God reported 3,557 members; all others which included Catholic, Episcopal, Adventists, and Lutherans reported 3,417 members.

9. Approximately one out of every three or 34.9 per cent of the urban Negro churches in North Carolina reported debt.

10. North Carolina's Negro population of church membership is relatively young. Of the 434,951 church members, 113,737 were under 13 years of age. Negro Baptists reported a membership of 19,520 under 13 years of age, representing 9.3 per cent of their total church membership.

Page 45

CHAPTER VIII

RECREATION

If an attempt were made to define recreation, it would probably be, "The art of re-creating or the state of being re-created; re-freshment of the strength and spirits after toil." Recreation is a universal phenomenon and not confined to any group or race. People have always had some form of recreation. However, the type of recreation has been profoundly influenced by the times and cultural status of the group. When the effect of recreation on the individual is studied from the social worker's point of view the paramount interest is the influence it wields on the adjustment to his total environment. A well-balanced or well-rounded personality does not develop in a vacuum but is developed as the individual comes into contact with his surroundings and other people.

A great deal of concern has been expressed over the housing, employment, health and other problems of the Negro in North Carolina, but very little over the recreation of the group. There is a belief that the inadequacy of the recreational facilities available to the group is to a large extent responsible for the high rate of crime and juvenile delinquency attributed to the race. These theories and beliefs may not be considered groundless when large numbers of Negro children, women, and men are found loitering on the streets at all hours of the day and night without any place to go for spontaneous expression. However, the inadequacy of recreational facilities is not solely a matter of race because this phase of the community life is woefully neglected in most communities of the State. In some communities, it has been considered a problem but not worthy of much attention or important enough to demand an answer. Recreation has been unable to hit a responsive chord in the general symphony of the attitudes of the general public. A depression with federally sponsored recreation programs by WPA and NYA helped to make North Carolina recreation conscious.

What is the purpose of recreation? What does it attempt to do? How does it attempt to do it? Why is it so important? The answers are evident whenever some idea of the contribution of recreation to the individual is stated. Recreation's contribution to the development of wholesome and well-balanced personality has been pointed out in the first paragraph. Wholesome and supervised recreation assists the individual to enjoy life and

Page 46

achieve happiness and contributes to the harmonious living together of individuals and groups.

The recreational activities of an individual or group are intricately interwoven with the economic status of the individual and crime rate of the group. When these theories or facts are applied to North Carolina's Negro population, it presents an unfavorable picture. The majority of the group depends entirely upon some form of commercialized, unsupervised or undesirable form of recreation for their leisure time. Usually these activities are centered in the home, church, school, or anywhere the individual is able to find them and most of the time when the Negro finds recreation it is undesirable. The movies, beer parlor, poolroom, and juke joint are usually the sources of commercial recreation for the group. If the average Negro home in North Carolina were considered as a center for recreation, it would present a formidable picture because it does not furnish an appropriate setting for the development of good character and wholesome or well-balanced personality because of its impoverished and low economic status.

Since North Carolina is largely a rural state and the bulk of the Negroes are located in the rural areas, the problem of recreation for the group is more difficult than in other more highly industrialized states. The Young Men and Young Women Christian Associations, Boy and Girl Scouts, and 4-H Clubs have been gaining in membership among Negroes in North Carolina in the larger cities and urban areas. However, there is much work to be done in all of these organizations before the masses are touched.

If recreation, leisure time activities, and character building agencies build character; if preventive work prevents; if all of these activities and agencies are good curative measures, then the almost complete dearth of these programs and activities for Negroes in North Carolina helps to explain some of the conditions of crime and delinquency existing among the race. It is not necessary to fall back upon speculation and wonder why the crime and juvenile delinquency rates are so high or the Negro is frustrated and maladjusted when it is evident that there is such a lack of outlets for recreation and spontaneous expression for the group.

There must be in North Carolina more constructive leisure time programs or outlets for both races, especially for Negroes, if the group is expected to live up to the accepted standards of the

Page 47

existing socio-economic order, develop wholesome personalities and good characters.

FACTS CONCERNING RECREATION

1. Ending June 1942, there were 22 public libraries for Negroes located in 20 counties in North Carolina. These counties had a population of approximately 433,519 Negroes or about one-half of the Negroes in the State. The remaining counties were without public library facilities designated for the race.

2. Negroes are permitted to use the North Carolina State Library; a reading room has been provided for them.

3. In 1935 there were only two Negroes employed in a full-time capacity to supervise recreation in North Carolina. They were employed in Asheville and Greensboro.

4. Until 1935, recreation was not given much attention in North Carolina. During the ERA period of 1935, a few areas were explored. Recreation made its greatest gains during the WPA era; under this program recreation was placed on a State-wide basis with a Negro assistant supervisor. NYA also sponsored recreation program at its resident centers.

5. In December 1936, there were 135 Negro recreation leaders in 41 counties on WPA projects. These counties reported a monthly activity attendance of 87,143 for this period.

6. The Young Men's and Young Women's Christian Associations provide leisure time facilities and activities for Negroes in the urban areas. Negro branches of the YMCA and YWCA were located in four cities.

7. Boy Scout troops headquarters were found in 12 cities and reported 197 troops throughout the State. In 20 cities and towns the Girl Scouts had 66 Negro troops. In 1942, there were 37 counties with Negro division of 4-H Clubs with a total membership of 27,360 boys and girls.

8. In 1943, there were five communities which provided recreation facilities in the form of swimming pools and parks for Negroes. They were High Point, Raleigh, Durham, Greensboro, and Winston-Salem.

9. For recreation in the home: Of every 1,000 owner occupied dwellings 706 owned some type of radio; for the whites 760 out of every 1,000 owned a radio in this group compared with 421 colored. The tenant occupied dwellings showed 522 out of every 1,000 with this item; 678 of the white tenants and 293 of the colored tenants out of every 1,000 possessed a radio.

10. On the optimistic side is the fact that most of the recreational activities or programs were taken over by the communities after the termination of WPA in May 1943.

Page 48