A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States;

With Remarks on Their Economy:

Electronic Edition.

Olmsted, Frederick Law, 1822-1903

Funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Tampathia Evans

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Melissa G. Meeks and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2001

ca. 1.4 MB

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States; With Remarks on Their Economy

(spine) Slave States.

(half-title page) Our Slave States.

Frederick Law Olmsted

xvi, 1-723, [1] p., ill.

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, SON, & CO., 47, LUDGATE HILL.

NEW YORK:

DIX AND EDWARDS.

1856.

Call number C917 O51j (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 24th edition, 2001

Languages Used:

- English

- French

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- Southern States -- Social life and customs.

- Slavery -- Southern States.

- Slaves -- Southern States -- Social conditions.

- Southern States -- Description and travel.

- North Carolina -- Description and travel.

- North Carolina -- Economic conditions.

- Southern States -- Economic conditions.

- Plantation life -- Southern States.

Revision History:

- 2002-08-28,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-11-29,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-11-16,

Melissa Meeks

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-09-20,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Spine]

[Title Page]

Our Slave States.

A

JOURNEY

IN THE

SEABOARD SLAVE STATES;

WITH REMARKS ON THEIR ECONOMY.

BY

FREDERICK LAW OLMSTED,

AUTHOR OF "WALKS AND TALKS OF AN AMERICAN FARMER IN ENGLAND."

LONDON:

SAMPSON LOW, SON, & CO., 47, LUDGATE HILL.

NEW YORK:

--DIX AND EDWARDS.

1856.

Page vii

ADVERTISEMENT.

IN the year 1853, the author of this work made a journey through the Seaboard Slave States, and gave an account of his observations in the "New York Daily Times," under the signature of "Yeoman." Those letters excited some attention, and their publication in a book was announced; but, before preparing them for the press, the author had occasion to make a second and longer visit to the South. In the light of the experience then gathered, the letters have been revised, and, with much additional matter, are now presented to the public.

The author's observations on Cotton Plantations, and in the frontier and hill-country of the South, may form the subject of a subsequent volume.

Page ix

PREFACE.

THE chief design of the author in writing this book has been, to describe what was most interesting, amusing, and instructive to himself, during the first three of fourteen months' traveling in our Slave States; using the later experience to correct the erroneous impressions of the earlier.

He is aware that it has one fault--it is too fault-finding. He is sorry for it, but it cannot now be helped; so at the outset, let the reader understand that he is invited to travel in company with an honest growler.

But growling is sometimes a duty; and the traveler might well be suspected of being a "dead head," or a sneak, who did not find frequent occasion for its performance, among the notoriously careless, make-shift, impersistent people of the South.

For the rest, the author had, at the outset of his

Page x

journey, a determination to see things for himself, as far as possible, and to see them carefully and fairly, but cheerfully and kindly. It was his disposition, also, to search for the causes and extenuating circumstances, past and present, of those phenomena which are commonly reported to the prejudice of the slaveholding community; and especially of those features which are manifestly most to be regretted in the actual condition of the older Slave States.

He protests that he has been influenced by no partisan bias; none, at least, in the smallest degree unfriendly to fair investigation, and honest reporting. At the same time, he avows himself a democrat; not in the technical and partisan, but in the primary and essential sense of that term. As a democrat he went to study the South--its institutions, and its people; more than ever a democrat, he has returned from this labor, and written the pages which follow.

SOUTH-SIDE STATEN ISLAND, Jan. 9, 1856.

Page xi

CONTENTS.

- The Institution for Travelers, 1;

- Servants, 3;

- A Maryland Farm, 5;

- Slave Labor, 10;

- Market Day, 11;

- Anecdote of a Washington Market-Woman, 12;

- Land and Labor, 13;

- Free Negroes, 14;

- Dangerous Men, 15.

CHAPTER I.

WASHINGTON.

- Rail-road Glimpses, 16;

- Richmond, 19;

- The "Public Guard," and what it means, 20;

- Pretense and Parsimony, 21;

- The Model American--Houdon's Statue, 22;

- Public Grounds, Arboriculture, 23;

- A Slave Funeral, 24;

- The Slaves on Sunday, 27;

- Dandies, White and Black, 28;

- Slaves as Merchandise, 30;

- A James River Farm, 40;

- Slave Labor, the Owner hard worked, 44;

- Overseers, 45;

- A Coal Mine--Negro and English Miners, 47;

- Valuable Servants, 49;

- Dress and Style of People, 50;

- The Great Southern Route, and its Fast Train, 52;

- One of the Law-Givers, 54;

- Freight Taken--the Slave Trade, 55;

- Taking Care of Negroes, 58;

- Rural Scenery, and Life in Virginia, 59;

- Pretty Jane, 62;

- A Sovereign--A School House, 64;

- "Old-Fields"--Wild Beasts, 65;

- Explicit Direction, 67;

- The "Straight Road," 69;

- A Farm House, 71;

- The Grocery, 73;

- The Court House, 74;

- The Inn, 75;

- The New Man, and the Old House, 77;

- Domestic Life, 80;

- White Laborers, 82;

- A Calamity, 83;

- Bed-time, 85;

- Settling, 86;

- The Wilderness--The Meeting-House, 87;

- An Old Tobacco Plantation, 88;

- Thinking and Working--Irish and Negro Labor, 91;

- A Free Labor Farm, 94;

- Freed Slaves, 95;

- Uncle Tom, 97;

- White Hands, 99;

- Runaways, 100;

- Recreation and Luxury among the Slaves, 101;

- A Bar-Room Session--Ingenuity of the Negro, 103;

- Qualities as a Laborer, 104;

- Improvement--Educational Privileges, 106;

- A Distinguished Divine, 107;

- How they are fed in Virginia, 108;

- Lodgings, 111;

- Clothing 112;

Page xii - Religious Condition, 113;

- Falsehood, 116;

- Stealing, 117;

- A Sermon for Slaves, 118;

- Another for Masters, 122;

- A Firm Faith, 123;

- Free Negroes, their Condition in Virginia, and elsewhere, 125;

- Petersburg to Norfolk, 133;

- James River--Norfolk, 135;

- Neglected Opportunities, 137;

- Legitimate Trade--Mopus, 141;

- Education of Laborers, and of Merchants--Influence of Slavery, 146;

- Labor for the Navy, 148;

- The Dismal Swamps, and the Lumber Trade, 149;

- Slave Lumbermen Life in the Swamp--Slaves Quasi Freemen, 153;

- The Effect of Wages to Slaves, 155;

- Agricultural Value of Swamp Land, 156;

- The Truck Business of Norfolk, 158;

- Runaways in the Swamp, 159;

- Dismal Negro Hunting, 160.

CHAPTER II.

VIRGINIA.

- Statistics of the Elements of Wealth, and of the Actual Results of Labor, 164;

- Of Intellectual Labor, 172;

- What is not the Cause of the comparative Poverty, 173;

- Property of the Inquiry, 177;

- Explanations suggested, 180;

- Their Insufficiency, 181;

- Cost and Value of Labor in Virginia, and in the Wealthier States, compared, 185;

- Loss to the Employer from Illness, etc., 186;

- Curious Complaints of Slaves, 191;

- House Servants, Free and Slave, compared, 195,

- Value of Good Will in Work, 198;

- The Alleged Slavery effected by Competition, 200;

- The Comparative Amount of Work accomplished by Slave Labor and Competitive Labor, 203;

- Driving, 205;

- Conclusion, 207;

- Why Free Labor, if cheaper, does not drive out Slavery, 208;

- Results where Free Labor has been concentrated, 213;

- The Great Experiment of the United States, 214.

CHAPTER III.

THE ECONOMY OF VIRGINIA.

- Some Data and Phenomena of the Virginia Experiments in Political Economy--how Initiated, 216;

- Convict Christian Slaves, 223;

- Christian Bond Servants, 227;

- Heathen, or Infidel Slaves, 231;

- Quality and Education of the Colonial Laborers, 234;

- The Proprietors, 234;

- Early Tobacco Culture, 236;

- What might have been, 240;

- Style of Living, 241;

- Wealth and Extravagance of the Colonial Aristocracy, 243;

- Industrial Condition of Virginia in the Halcyon Past, 248;

- The Revolution of 1776--Excitement and Reaction, 255;

- Religious Liberty, 257;

- Primogeniture and Entail, 259;

- Education and Emancipation of the Slave People, 261;

- Of the White Poor, 267;

- Social Results of the Revolution, 269;

- Industrial Results, 271;

- Downfall of the Aristocracy, 273;

- Effect of Democracy, 275;

- Industrial Progress, 277;

- Rise of the Internal Slave Trade, 278;

- Its Industrial Consequences, 280;

- Influence on Condition of the Slave, 281;

Page xiii- Effect of the Abolition Agitation, 284;

- Present the Political Tendencies in Virginia, 288;

- Education, 291;

- The Future Prospect, 302.

CHAPTER IV.

THE POLITICAL EXPERIENCE OF VIRGINIA.

- Mine Ease in mine Hotel, 305;

- Petersburg to Weldon, 307;

- Stage Coaching, 309;

- Lazy Niggers, 313;

- Negroes on Public Conveyances, 315;

- The Idee of Potassum a First-Rater, 317;

- Night Trains, 317;

- Raleigh, 318;

- Evergreens, 319;

- A Stage Coach Campaign, 320;

- Bawley, Rock, and Bob, 323;

- The Piny Wood, 325;

- A Horse-Killer, 329;

- A Praying Blacksmith, 331;

- Talent Applied to Inn-Keeping, 332;

- Fire! Turn Out! 337;

- Turpentine, and Naval Stores--An Account of the Method of Collection, and of Manufacture, 337;

- Distillation, 343;

- Rosin, 345;

- Tar, 347;

- Slaves in the Turpentine Country, and White Vagabonds, 388;

- The North Carolina Fisheries, and Slave Fishermen, 351;

- Titanic Dentistry, 354;

- Slaves Eager to work when stimulated by Wages, 355;

- Scotch Highlanders--Immigration to North Carolina, 355;

- A Cotton Mill, 356;

- Wagoners, 357;

- Boatmen, 359;

- Tobacco-Rollers, 360;

- Improved Means of Transport, 361;

- Gross Intermeddling of Northerners, 363;

- Wagon Competition with Rail-roads, 364;

- Plank Roads, 365;

- North Carolina Character, 366;

- Slavery in North Carolina, 367;

- Cape Fear River, 368;

- Wooding Up, 369;

- Labor in the Glue Trade, 371;

- Wilmington, 374;

- Property Interests, 375.

CHAPTER V.

NORTH CAROLINA.

- Rail-road Gang, 377;

- Northern Hay, 378;

- Profit of Slave-Labor, 379;

- Rough Riding, 380;

- "Very Nice Country," 382;

- Natural Scenery, 382;

- The People, 384;

- Their Habitations, 385;

- Cotton Plantations, 386;

- Field Hands, 387;

- An Overseer, 388;

- A Free Nigger, 389;

- North Carolina and South Carolina Niggers, 391;

- A Pleasant Farm House, 393;

- Negro Jodling--the Carolina Yell, 394;

- Camp Fires, 395;

- Slaves at Work, 397;

- Conversation with a Peasant, 398;

- His Geographical Knowledge--Education of the Children of the Higher Class, 402;

- Manners and Morals in South Carolina, 403;

- Charleston, 404;

- Savannah, 405;

- Slave Funerals, 405;

- A Slave Grave-Yard--Tombstones, 406;

- The Rice Coast, 409;

- Northern Invalids and Other Travelers, and the Accommodations for them, 409;

- "Show Plantations," 412;

- The Crackers, 413;

- Negro Quarters, 416;

- A Delightful Mansion, Wonderful Live Oak Avenue, 417;

- Visit to a Rice Plantation, 418;

- The Rice Coast Malaria, 418;

- House Servants and Field Hands, 421;

- Negro Quarters, 422;

- The Slave Nursery, 423;

- Teufelsdrockh's Secret of Happiness, 425;

- The Watchman--an intelligent and trusty Slave, 426;

- How he became so--Effect of Education, 429;

Page xiv- What is the Economy of Slavery, 429;

- Field Hands, 430;

- Food, 431;

- More Field Hands, their Dress and Appearance, 432;

- "Water Toters," 433;

- Grades of Field Hands, 433;

- A Native African--Task Work, 434;

- Drivers, 436;

- Punishment, 438;

- Slaves taking care of themselves, 439;

- Nefarious Traders and Grog-Shops, 441;

- Laws of Trade on the Plantation, 442;

- A Scheme of Emancipation suggested, 443;

- Special Depravity of the Negro, 446;

- Slave Marriages and Funerals, 448;

- Slave Chapels and Worship, 449;

- Slave Clergy, 450;

- A Religious Service among the Crackers, 451.

CHAPTER VI.

SOUTH CAROLINA AND GEORGIA.

- Rice, and its Culture--Extent, and how Limited, 462;

- The Atlantic Rice District, 465;

- Slave Labor, as applied on Rice Plantations, 478;

- Treatment of Slaves on Rice Plantations, 484;

- Overseers, 486.

CHAPTER VII.

RICE, AND ITS CULTURE.

- The Democratic Social Theory, 489;

- The South Carolina Social Theory, 491;

- Origin and Early Character of South Carolina, 492;

- Origin of "Americanism," 495;

- The Early Black Code, 496;

- Progress, 497;

- Results, 500;

- Good Society, 501;

- The Free Laboring Class at the Revolution, 502;

- Its Present Condition, 504;

- The Sand-Hillers, 506;

- Immigration, 510;

- Present Industrial Condition, 515;

- The Predicament, 522;

- The Origin of the Georgia Community, 523;

- Early Resistance to Slavery, 527;

- The Law against Slavery abrogated, 528;

- Influence of the Early Democracy, 529;

- Consequences of Slavery, 531;

- Note on Ship-Building, 540;

- On Manufactures, and other Industry, 542.

CHAPTER VIII.

EXPERIMENTAL POLITICAL ECONOMY OF SOUTH CAROLINA

AND GEORGIA.

- Georgia Rail-roads, 546;

- Columbus--Manufacturing Workmen, 547;

- Montgomery, 549;

- The Alabama River, 549;

- Loading Cotton, 550;

- Value of Slaves secures Care of them, 550;

- Negro Singers, 551;

- Capacity of the Negro, 552;

- Slave High Life, 554;

- A Negro Lover, 554;

- A Negro Overseeing a White Laborer, 555;

- Natural Affection of Slaves, 555;

- Their Loyalty to their Masters, 556;

- Conversation with a Good Subject, 557;

- The Citizens, 559;

- Characteristics, 560;

- A Droll Texan, 560;

- How he talked, 561;

- Not a Betting, but a Cotton Man, 562;

Page xv - Deck Hands, Negro Jollity, and Wastefulness, 564;

- Mobile, 565;

- Passage to New Orleans--Texan Immigrants, 568;

- Bad Speculation with a Negro, 570;

- a Peasant--Conversation about Slavery and Abolition, 572.

CHAPTER IX.

ALABAMA.

- Origin, 574;

- Emigration, 576;

- Present Condition and Prospects, 576.

CHAPTER X.

ECONOMICAL EXPERIENCE OF ALABAMA.

- New Orleans, 578;

- French Aspect, 580;

- The Cathedral, 582;

- Gradations of Color among the People, 583,

- Fine Negro Stock, 584;

- The Slave Trade, Economically, 585;

- Could Europeans displace Negroes in the Climate, 586;

- Mechanics and Laborers, 587;

- Competition of Free and Slave, 589;

- Commerce and Slavery, 591;

- The Lorettes, 594;

- Licentiousness and Extravagance--Democratic Education, 598;

- Red River Emigrant Craft, 603;

- Uncle Tom and the Vindication of Slavery--a Rebuff, 606;

- Negro Boat Songs--Stowing Away, 611;

- Slave Emigrants, 613;

- A Race, 614;

- Sharp Shooters, 615;

- Uncle Tom discussed, 617;

- Another Sort, 620;

- A Carlylist, 631;

- Elements of Progress, North and South, 621;

- Rigolet de Bon Dieu--Use of Claret--The Temperance Problem, 625;

- Planting and Grazing, 628;

- Negro Cabins, 629;

- Positive Morality, A Secret Agent of Satan, 630;

- Buying the Spanish Vote, 632;

- Free Colored Slave-Owners, 632;

- Conversation with a Free Negro, 634;

- Louisiana Lawyers, 637;

- Egyptians, 638;

- White Slaves, 640;

- Opelousas, 642;

- Germans, 642;

- Pleasant Retirement, 643;

- "Fights," 644;

- Theology and Morality, 645;

- A Creole Ball, 646;

- Court, 646;

- The Nigger Trade, 647;

- The Creoles, 648;

- Condition of their Slaves, 650;

- Planters of Louisiana and Farmers of New York compared, 652;

- Habits of the Planters, 652;

- Cuba, 655;

- Visit to a Sugar Plantation, 656;

- Relation of Slaves and Owner, 658;

- Treatment of Slaves, 659;

- Plantation Economy, 660;

- Sugar Cane, 663;

- Economy of Louisiana, 664;

- Cane Culture, 665;

- The Grinding Season, 667;

- Hard Work liked, 668;

- Manufacture of Sugar, 670;

- Acadiens, 673;

- Chicken Thieves, 674;

- Conversation on Slavery, 675;

- Conversation with a Slave about Abolitionism, 677;

- Expenses of Plantations, 686;

- Condition of Free and Slave Laborers compared, 688;

- Slavery no Security against Famine, 707;

- Conclusion, 711;

- Influence of Slavery on our own Labor, 712;

- Appendix, 717;

- Appendix A, 724.

CHAPTER XI.

LOUISIANA.

Page xvi

"Men are never so likely to settle a question rightly as when they discuss it freely."--Macaulay.

"You have among you many a purchased slave,

Which, like your asses, and your dogs, and mules,

You use in abject and in slavish parts,

Because you bought them:

"So do I answer you.

The pound of flesh which I demand of him,

Is dearly bought; 'tis mine, and I will have it.

If you deny me, fie upon your law!"

--Shylock.

"The one idea which History exhibits as evermore developing itself into greater distinctness, is the idea of humanity, the noble endeavor to throw down all barriers erected between men by prejudice and one-sided views, and by setting aside the distinctions of religion, country, and color, to treat the whole human race as one Brotherhood, having one great object--the pure development of our spiritual nature."--Humboldt's Cosmos.

Page 1

OUR SLAVE STATES.

CHAPTER I.

INNS AND OUTS OF WASHINGTON.

GADSBY'S HOTEL, Dec. 10.

To accomplish the purposes which brought me to Washington, it was necessary, on arriving here, to make arrangements to secure food and shelter while I remained. There are two thousand of us visitors in Washington under a similar necessity. There are a dozen or more persons who, for a consideration, undertake to provide what we want. Mr. Dexter is reported to be the best of them, and really seems a very obliging and honestly-disposed person. To Mr. Dexter, therefore, I commit myself.

I commit myself by inscribing my name in a Register. Five minutes after I have done so, Clerk No. 4, whose attention I have been unable to obtain any sooner, suddenly catches the Register by the corner, swings it round with a jerk, and throws a hieroglyphic scrawl at it, which strikes near my name. Henceforth, I figure as Boarder No. 201, (or whatever it may be). Clerk No. 4 whistles ("Boarders, away!"), and throws key, No. 201 upon the table. Turnkey No. 3 takes

Page 2

it, and me, and my traveling bag, up several flights of stairs, along corridors and galleries, and finally consigns me to this little square cell.

I have faith that there is a tight roof above the very much cracked ceiling; that the bed is clean; and that I shall, by-and-by, be summoned, along with hundreds of other persons, to partake, in grandly silent sobriety, of a very sumptuous dinner.

Food and Shelter. Therewith should a man be content. It will enable me to accomplish my purpose in coming to Washington. But my perverse nature will not be content: will be wishing things were otherwise. They say this uneasiness--this passion for change--is a peculiarity of our diseased Northern nature. The Southern man finds Providence in all that is: Satan in all that might be. That is good; and, as I am going South, when I have accomplished my purposes at Washington, I will not here restrain the escape of my present discontent.

I have such a shockingly depraved nature that I wish the dinner was not going to be so grand. My idea is that, if it were not, Mr. Dexter would save moneys, which I would like to have him expend in other ways. I wish he had more clerks, so that they would have time to be as polite to an unknown man as I see they are to John P. Hale; and, at least, answer civil questions, when his guests ask them. I don't like such a fearful rush of business as there is down stairs. I wish there were men enough to do the work quietly.

I don't like these cracked and variegated walls; and, though the roof may be tight, I don't like this threatening aspect of the ceiling. It should be kept for people of Damoclesian ambition: I am humble.

Page 3

I am humble, and I am short, and soon curried; but I am not satisfied with a quarter of a yard of toweling, having an irregular vacancy in its centre, where I am liable to insert my head. I am not proud; but I had rather have something else, or nothing, than these three yards of ragged and faded quarter-ply carpeting. I also would like a curtain to the window, and I wish the glass were not so dusty, and that the sashes did not rattle so in their casements; though, as there is no other ventilation, I suppose I ought not to complain. Of course not; but it is confoundedly cold, as well as noisy. I don't like that broken latch; I don't like this broken chair; I would prefer that this table were not so greasy in its appearance; I would rather the ashes and cinders, and the tobacco juice around the grate, had been removed before I was consigned to the cell.

I wish that less of my two dollars and a half a day went to pay for game for the dinner, and the interest of the cost of the mirrors and mahogany for the public parlors, and of marble for the halls, and more of it for providing me with a private room, which should be more than a barely habitable cell, which should also be a little bit tasteful, home-like, and comfortable.

SERVANTS.

I wish more of it was expended in servants' wages.

Six times I rang the bell; three several times came three different Irish lads; entered, received my demand for a fire, and retired. I was writing, shiveringly, a full hour before the fire-man came. Now he has entered, bearing on his head a hod of coal and kindling wood, without knocking. An aged negro, more familiar and more indifferent to forms of subserviency that

Page 4

the Irish lads, very much bent, seemingly with infirmity, an expression of impotent anger in his face, and a look of weakness, like a drunkard's. He does not look at me, but mutters unintelligibly.

"What's that you say?"

"Tink I can make a hundred fires at once?"

"I dont want to sit an hour waiting for a fire, after I have ordered one, and you must not let me again."

"Nebber let de old nigger have no ress--hundred gemmen tink I kin mak dair fires all de same minute; all get mad at an ole nigger; I ain't a goin to stan it--nebber get no ress--up all night--haint got nautin to eat nor drink dis blessed mornin--hundred gemmen --"

"That's not my business; Mr. Dexter should have more servants."

"So he ort ter, master, dat he had, one ole man ain't enough for all dis house, is it master? hundred gemmen --"

"Stop--here's a quarter for you; now I want you to look out that I have a good fire, and keep the hearth clean in my room as long as I stay here. And when I send for you I want you to come immediately. Do you understand?"

"I'le try, master--you jus look roun and fine me when you want yer fire; I'll be roun somewhere. You got a newspaper, Sir, I ken take for a minit; I won't hurt it."

I gave him one; and wondered what use he could put it to, that would not hurt it. He opened it to a folio, and spread it before the grate, so the draft held it in place, and it acted as a blower. I asked if there were no blowers? "No." "But haven't you got any brush or shovel?" I inquired, seeing him get down upon his knees again and sweep the cinders and ashes

Page 5

he had thrown upon the floor with the sleeve of his coat, and then take them up with his hands;--no, he said, his master did not give him such things. "Are you a slave?"

"Yes, sir."

"Do you belong to Mr. Dexter?"

"No, sir, he hires me of de man dat owns me. Don't you tink I'se too ole a man for to be knock roun at dis kind of work, massa?--hundred gemmen all want dair fires made de same minute, and caus de old nigger cant do it all de same minute, ebbery one tinks dey's boun to scold him all de time; nebber no rest for him, no time."

I know the old fellow lied somewhat, for I saw another fireman in Mr. B.'s room. Was that quarter a good investment, or should I have complained at the office? No, they are too busy to listen to me, too busy, certainly, to make better arrangements.

It is time for me to call on Mr. S.; the fire has gone out, leaving a fine bituminous fragrance in the cell. I will "look round" for the fireman, as I travel the long road to the office, and, if I do not find him, leave an order, in writing, for a fire to be made before two o'clock.

A MARYLAND FARM.

WASHINGTON, Dec. 14th. Called on Mr. C., whose fine farm, from its vicinity to Washington, and its excellent management, as well as from the hospitable habits of its owner, has a national reputation. It is some two thousand acres in extent, and situated just without the District, in Maryland.

The residence is in the midst of the farm, a quarter of a mile from the high road--the private approach being judiciously carried through large pastures which are divided only by slight, but close

Page 6

and well-secured, wire fences. The mansion is of brick, and, as seen through the surrounding trees, has somewhat the look of an old French chateau. The kept grounds are very limited, and in simple but quiet taste; being surrounded only by wires, they merge, in effect, into the pastures. There is a fountain, an ornamental dove-cote, and ice-house, and the approach road, nicely graveled and rolled, comes up to the door with a fine sweep.

I had dismounted and was standing before the door, when I heard myself loudly hailed from a distance.

"Ef yer wants to see Master, sah, he's down thar--to the new stable."

I could see no one; and when I was tired of holding my horse, I mounted, and rode on in search of the new stable. I found it without difficulty; and in it Mr. and Mrs. C. With them were a number of servants, one of whom now took my horse with alacrity. I was taken at once to look at a very fine herd of cows, and afterwards led upon a tramp over the farm, and did not get back to the house till dinner time.

The new stable is most admirably contrived for convenience, labor-saving, and economy of space. (Full and accurate descriptions of it, with illustrations, have been given in several agricultural journals.) The cows are mainly thorough-bred Shorthorns, with a few imported Ayrshires and Alderneys, and some small black "natives." I have seldom seen a better lot of milkers; they are kept in good condition, are brisk and healthy, docile and kind, soft and pliant of skin, and give milk up to the very eve of calving; milking being never interrupted for a day. Near the time of calving the milk is given to the calves and pigs. The object is to obtain milk only, which is never converted into butter or cheese, but sent immediately to town, and for this the

Page 7

Shorthorns are found to be the most profitable breed. Mr. C. believes that, for butter, the little Alderneys, from the peculiar richness of their milk, would be the most valuable. He is, probably, mistaken, though I remember that in Ireland the little black Kerry cow was found fully equal to the Ayrshire for butter, though giving much less milk.

There are extensive bottom lands on the farm, subject to be flooded in freshets, on which the cows are mainly pastured in summer. Indian corn is largely sown for fodder, and, during the driest season, the cows are regularly soiled with it. These bottom lands were entirely covered with heavy wood, until, a few years since, Mr. C. erected a steam saw-mill, and has lately been rapidly clearing them, and floating off the sawed timber to market by means of a small stream that runs through the farm.

The low land is much of it drained, underdrains being made of rough boards of any desired width nailed together, so that a section is represented by the inverted letter

. Such covered drains have lasted here twenty years without failing yet, but have only been tried where the flow of water was constant throughout the year.

. Such covered drains have lasted here twenty years without failing yet, but have only been tried where the flow of water was constant throughout the year.

The water collected by the drains can be, much of it, drawn into a reservoir, from which it is forced by a pump, driven by horse-power, to the market-garden, where it is distributed from several fountain-heads, by means of hose, and is found of great value, especially for celery. The celery trenches are arranged in concentric circles, the water-head being in the center. The water-closets and all the drainage of the house are turned to good account in the same way. Mr. C. contemplates extending his water-pipes to some of his meadow lands. Wheat and hay

Page 8

are the chief crops sold off the farm, and the amount of them produced is yearly increasing.

The two most interesting points of husbandry, to me, were the large and profitable use of guano and bones, and the great extent of turnip culture. Crops of one thousand and twelve hundred bushels of ruta baga to the acre have been frequent, and this year the whole crop of the farm is reckoned to be over thirty thousand bushels; all to be fed out to the neat stock between this time and the next pasture season. The soil is generally a red, stiff loam, with an occasional stratum of coarse gravel, and, therefore, not the most favorable for turnip culture. The seed is always imported, Mr. C.'s experience, in this respect, agreeing with my own:--the Ruta baga undoubtedly degenerates in our climate. Bones, guano, and ashes are used in connection with yarddung for manure. The seed is sown from the middle to the last of July in drills, but not in ridges, in the English way. In both these respects, also, Mr. C. confirms the conclusions I have arrived at in the climate of New York; namely, that ridges are best dispensed with, and that it is better to sow in the latter part of July than in June, as has been generally recommended in our books and periodicals. Last year, turnips sown on the 20th July were larger and finer than others, sown on the same ground, on my farm, about the first of the month. This year I sowed in August, and, by forcing with superphosphate--home manufactured--and guano, obtained a fine crop; but the season was unusually favorable.

Mr. C. always secures a supply of turnips that will allow him to give at least one bushel a day to every cow while in winter quarters. The turnips are sliced, slightly salted, and commonly mixed with fodder and meal. Mr. C. finds that salting the

Page 9

sliced turnip, twelve hours before it is fed, effectually prevents its communicating any taste to the milk. This, so far as I know, is an original discovery of his, and is one of great value to dairymen. In certain English dairies the same result is obtained, where the cows are fed on cabbages, by the expensive process of heating the milk to a certain temperature and then adding saltpetre.

The wheat crop of this district has been immensely increased, by the use of guano, during the last four years. On this farm it has been largely used for five years; and land that had not been cultivated for forty years, and which bore only broom-sedge--a thin, worthless grass--by the application of two hundred weight of Peruvian guano, now yields thirty bushels of wheat to an acre.

Mr. C.'s practice of applying guano differs, in some particulars, from that commonly adopted here. After a deep plowing of land intended for wheat, he sows the seed and guano at the same time, and harrows both in. The common custom here is to plow in the guano, six or seven inches deep, in preparing the ground for wheat. I believe Mr. C.'s plan is the best. I have myself used guano on a variety of soils for several years with great success for wheat, and I may mention the practice I have adopted from the outset, and with which I am well satisfied. It strikes between the two systems I have mentioned, and I think is philosophically right. After preparing the ground with plow and harrow, I sow wheat and guano together, and plow them in with a gang-plow which covers to a depth, on an average, of three inches.

Clover seed is sowed in the spring following the wheat-sowing, and the year after the wheat is taken off, this--on the old sterile hills--grows luxuriantly, knee-high. It is left alone for two years, neither mown nor pastured; there it grows and there it

Page 10

lies, keeping the ground moist and shady, and improving it on the Gurney principle.

Mr. C. then manures with dung, bones, and guano, and with another crop of wheat lays this land down to grass. What the ultimate effect of this system will be, it is yet too early to say--but Mr. C. is pursuing it with great confidence.

SLAVE LABOR--FIRST IMPRESSIONS.

Mr. C. is a large hereditary owner of slaves, which, for ordinary field and stable-work, constitute his laboring force. He has employed several Irishmen for ditching, and for this work, and this alone, he thought he could use them to better advantage than negroes. He would not think of using Irishmen for common farm-labor, and made light of their coming in competition with slaves. Negroes at hoeing and any steady field-work, he assured me, would "do two to their one;" but his main objection to employing Irishmen was derived from his experience of their unfaithfulness--they were dishonest, would not obey explicit directions about their work, and required more personal supervision than negroes. From what he had heard and seen of Germans, he supposed they did better than Irish. He mentioned that there were several Germans who had come here as laboring men, and worked for wages several years, who had now got possession of small farms, and were reputed to be getting rich.*

* "There is a small settlement of Germans, about three miles from me, who, a few years since (with little or nothing beyond their physical abilities to aid them), seated themselves down in a poor, miserable old field, and have, by their industry, and means obtained by working round among the neighbors, effected a change which is really surprising and pleasing to behold, and who will, I have no doubt, become wealthy, provided they remain prudent, as they have hitherto been industrious."--F. A. CLOPPER, (Montgomery Co.), Maryland, in Patent Of. Rept., 1851.

He was disinclined to converse on the topic of slavery, and

Page 11

I, therefore, made no inquiries about the condition and habits of his negroes, or his management of them. They seemed to live in small and rude log-cabins, scattered in different parts of the farm. Those I saw at work appeared to me to move very slowly and awkwardly, as did also those engaged in the stable. These, also, were very stupid and dilatory in executing any orders given to them, so that Mr. C. would frequently take the duty off their hands into his own, rather than wait for them, or make them correct their blunders: they were much, in these respects, like what our farmers call dumb Paddies--that is, Irishmen who do not readily understand the English language, and who are still weak and stiff from the effects of the emigrating voyage. At the entrance-gate was a porter's lodge, and, as I approached, I saw a black face peeping at me from it, but, both when I entered and left, I was obliged to dismount and open the gate myself.

Altogether, it struck me--slaves coming here as they naturally did in direct comparison with free laborers, as commonly employed on my own and my neighbor's farms, in exactly similar duties--that they must be very difficult to direct efficiently, and that it must be very irksome and trying to one's patience, to have to superintend their labor.

MARKET-DAY--NEGROES AND LIVE STOCK.

WASHINGTON, Dec. 16. Visiting the market-place, early on Tuesday morning, I found myself in the midst of a throng of a very different character from any I have ever seen at the North. The majority of the people were negroes, and, taken as a whole, they appeared inferior in the expression of their face and less well-clothed than any collection of negroes I had ever seen before. All the negro characteristics

Page 12

were more clearly marked in each than they often are in any at the North. In their dress, language, manner, motions--all were distinguishable almost as much by their color, from the white people who were distributed among them, and engaged in the same occupations--chiefly selling poultry, vegetables, and small country-produce. The white men were, generally, a mean looking people, and but meanly dressed, but differently so from the negroes.

Most of the produce was in small, rickety carts, drawn by the smallest, ugliest, leanest lot of oxen and horses that I ever saw. There was but one pair of horses in over a hundred that were tolerably good--a remarkable proportion of them were maimed in some way. As for the oxen, I do not believe New England and New York together could produce a single yoke so poor as the best of them.

The very trifling quantity of articles brought in and exposed for sale by most of the market-people was noticeable; a peck of potatoes, three bunches of carrots, two cabbages, six eggs and a chicken, would be about the average stock in trade of all the dealers. Mr. F. said that an old negro woman once came to his door with a single large turkey, which she pressed him to buy. Struck with her fatigued appearance, he made some inquiries of her, and ascertained that she had been several days coming from home, had traveled mainly on foot, and had brought the turkey and nothing else with her. "Ole massa had to raise some money somehow, and he could not sell anything else, so he tole me to catch the big gobbler, and tote um down to Washington and see wot um would fotch."

The prices of garden productions were high, compared even with New York. All the necessaries of life are very expensive in

Page 13

Washington; great complaint is made of exorbitant rents, and building-lots are said to have risen in value several hundred per cent. within five or six years.

The population of the city is now over 50,000, and is increasing rapidly. There seems to be a deficiency of tradespeople, and I have no doubt the profits of retailers are excessive. There is one cotton factory in the District of Columbia, employing one hundred and fifty hands, male and female; a small foundry; a distillery; and two tanneries--all not giving occupation to fifty men; less than two hundred, altogether, out of a resident population of nearly 150,000, being engaged in manufactures. Very few of the remainder are engaged in productive occupations. There is water-power near the city, superior to that of Lowell, of which, at present, I understand that no use at all is made.

LAND AND LABOR IN THE DISTRICT.

Land may be purchased, within twenty miles of Washington, at from ten to twenty dollars an acre. Most of it has been once in cultivation, and, having been exhausted in raising tobacco, has been, for many years, abandoned, and is now covered by a forest growth. Several New Yorkers have lately speculated in the purchase of this sort of land, and, as there is a good market for wood, and the soil, by the decay of leaves upon it, and other natural causes, has been restored to moderate fertility, have made money by clearing and improving it. By deep plowing and limeing, and the judicious use of manures, it is made very productive; and, as equally cheap farms can hardly be found in any free State, in such proximity to so high markets for agricultural produce, as those of Washington and Alexandria, there are good inducements for a considerable

Page 14

Northern immigration hither. It may not be long before a majority of the inhabitants will be opposed to Slavery, and desire its abolition within the District. Indeed, when Mr. Seward proposed in the Senate to allow them to decide that matter, the advocates of "popular sovereignty" made haste to vote down the motion.

There are, already, more Irish and German laborers and servants than slaves, and, as many of the objections which free laborers have to going further South, do not operate in Washington, the proportion of white laborers is every year increasing. The majority of servants, however, are now free negroes, which class constitutes one-fifth of the entire population. The slaves are one-fifteenth, but are mostly owned out of the District, and hired annually to those who require their services. In the assessment of taxable property, for 1853, the slaves, owned or hired in the District, were valued at three hundred thousand dollars.

THE NEGROES OF WASHINGTON.

The colored population voluntarily sustain several churches, schools, and mutual assistance and improvement societies, and there are evidently persons among them of no inconsiderable cultivation of mind. Among the Police Reports of the City newspapers, there was lately (April, 1855) an account of the apprehension of twenty-four "genteel colored men" (so they were described), who had been found by a watchman assembling privately in the evening, and been lodged in the watch-house. The object of their meeting appears to have been purely benevolent, and, when they were examined before a magistrate in the morning, no evidence was offered, nor does there seem

Page 15

to have been any suspicion that they had any criminal purpose. On searching their persons, there were found a Bible, a volume of Seneca's Morals; Life in Earnest; the printed Constitution of a Society, the object of which was said to be "to relieve the sick, and bury the dead;" and a subscription paper to purchase the freedom of Eliza Howard, a young woman, whom her owner was willing to sell at $650.

I can think of nothing that would speak higher for the character of a body of poor men, servants and laborers, than to find, by chance, in their pockets, just such things as these. And I cannot value that man as a countryman, who does not feel intense humiliation and indignation, when he learns that such men may not be allowed to meet privately together, with such laudable motives, in the capital city of the United States, without being subject to disgraceful punishment. Washington is, at this time, governed by the Know Nothings, and the magistrate, in disposing of the case, was probably actuated by a well-founded dread of secret conspiracies, inquisitions, and persecutions. One of the prisoners, a slave named Joseph Jones, he ordered to be flogged; four others, called in the papers free men, and named John E. Bennett, Chester Taylor, George Lee, and Aquila Barton, were sent to the Work-house, and the remainder, on paying costs of court, and fines, amounting, in the aggregate, to one hundred and eleven dollars, were permitted to range loose again.

Page 16

CHAPTER II.

VIRGINIA.

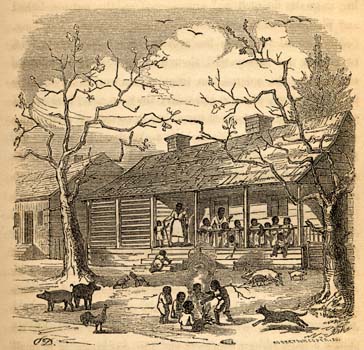

[Illustration.]

GLIMPSES BY RAIL-ROAD.

DEC. 16th. From Washington to Richmond, Virginia, by the regular great southern route--steamboat on the Potomac to Acquia Creek, and thence direct by rail. The boat makes 55 miles in 3½ hours, including two stoppages (12½ miles an hour); fare $2 (3.6 cents a mile). Flat rail; distance, 75 miles; time, 5½ hours (13 miles an hour); fare, $3 50 (4⅔ cents a mile).

Not more than a third of the country, visible on this route,

Page 17

I should say, is cleared; the rest is mainly a pine forest. Of the cleared land, not more than one quarter seems to have been lately in cultivation; the rest is grown over with briars and bushes, and a long, coarse grass of no value. But two crops seem to be grown upon the cultivated land--maize and wheat. The last is frequently sown in narrow beds and carefully surface-drained, and is looking remarkably well.

A good many substantial old plantation mansions are to be seen; generally standing in a grove of white oaks, upon some hill-top. Most of them are constructed of wood, of two stories, painted white, and have, perhaps, a dozen rude-looking little log-cabins scattered around them, for the slaves. Now and then, there is one of more pretension, with a large porch or gallery in front, like that of Mount Vernon. These are generally in a heavy, compact style; less often, perhaps, than similar establishments at the North, in markedly bad, or vulgar taste; but seldom elegant, or even neat, and almost always in sad need of repairs.

The more common sort of habitations of the white people are either of logs or loosely-boarded frames, a brick chimney running up outside, at one end: everything very slovenly and dirty about them. Swine, fox-hounds, and black and white children, are commonly lying very promiscuously together, on the ground about the doors.

I am struck with the close co-habitation and association of black and white--negro women are carrying black and white babies together in their arms; black and white children are playing together (not going to school together); black and white faces are constantly thrust together out of the doors, to see the train go by.

Page 18

A fine-looking, well-dressed, and well-behaved colored young man sat, together with a white man, on a seat in the cars. I suppose the man was his master; but he was much the less like a gentleman, of the two. The rail-road company advertise to take colored people only in second class trains; but servants seem to go with their masters everywhere. Once, to-day, seeing a lady entering the car at a way-station, with a family behind her, and that she was looking about to find a place where they could be seated together, I rose, and offered her my seat, which had several vacancies around it. She accepted it, without thanking me, and immediately installed in it a stout negro woman; took the adjoining seat herself, and seated the rest of her party before her. It consisted of a white girl, probably her daughter, and a bright and very pretty mulatto girl. They all talked and laughed together, and the girls munched confectionery out of the same paper, with a familiarity and closeness of intimacy that would have been noticed with astonishment, if not with manifest displeasure, in almost any chance company at the North. When the negro is definitely a slave, it would seem that the alleged natural antipathy of the white race to associate with him is lost.

I am surprised at the number of fine-looking mulattoes, or nearly white colored persons, that I see. The majority of those with whom I have come personally in contact are such. I fancy I see a peculiar expression among these--a contraction of the eyebrows and tightening of the lips--a spying, secretive, and counsel-keeping expression.

But the great mass, as they are seen at work, under overseers, in the fields, appear very dull, idiotic, and brute-like; and it requires an effort to appreciate that they are, very much more

Page 19

than the beasts they drive, our brethren--a part of ourselves. They are very ragged, and the women especially, who work in the field with the men, with no apparent distinction in their labor, disgustingly dirty. They seem to move very awkwardly, slowly, and undecidedly, and almost invariably stop their work while the train is passing.

One tannery and two or three saw-mills afforded the only indications I saw, in seventy-five miles of this old country--settled before any part of Massachusetts--of any industrial occupation other than corn and wheat culture, and fire-wood chopping. At Fredericksburg we passed through the streets of a rather busy, poorly-built town; but, altogether, the country seen from the rail-road, bore less signs of an active and prospering people than any I ever traveled through before, for an equal distance.

RICHMOND, AT A GLANCE.

Richmond, at a glance from adjacent high ground, through a dull cloud of bituminous smoke, upon a lowering winter's day, has a very picturesque appearance, and I was reminded of the sensation produced by a similar

A considerable part of the town, which contains a population

Page 20

of 28,000, is compactly and somewhat substantially built, but is without any pretensions to architectural merit, except in a few modern private mansions. The streets are not paved, and but few of them are provided with side-walks other than of earth or gravel. The town is lighted with gas, and furnished with excellent water by an aqueduct.

THE CAPITOL.

On a closer view of the Capitol, a bold deviation from the Grecian model is very noticeable. The southern portico is sustained upon a very high blank wall, and is as inaccessible from the exterior as if it had been intended to fortify the edifice from all ingress other than by scaling-ladders. On coming round to the west side, however, which is without a colonnade, a grand entrance, reached by a heavy buttress of stone steps, is found. This incongruity diminishes, in some degree, the usual inconvenience of the Greek temple for modern public purposes, for it gives speedy access to a small central rotunda, out of which doors open into the legislative halls and offices.

THE "PUBLIC GUARD," AND WHAT IT MEANS.

If the walling up of the legitimate entrance has caused the impression, in a stranger, that he is being led to a prison or fortress, instead of the place for transacting the public business of a free State by its chosen paid agents, it is not removed when, on approaching this side door, he sees before it an armed sentinel--a meek-looking man in a livery of many colors, embarrassed with a bright bayonetted firelock, which he hugs gently, as though the cold iron, this frosty day, chilled his arm.

Page 21

He belongs to the Public Guard of Virginia, I am told; a company of a hundred men (more or less), enlisted under an Act of the State, passed in 1801, after a rebellion of the colored people, who, under one "General Gabriel," attempted to take the town, in hopes to gain the means of securing their freedom. Having been betrayed by a traitor, as insurgent slaves almost always are, they were met, on their approach, by a large body of well-armed militia, hastily called out by the Governor. For this, being armed only with scythe-blades, they were unprepared, and immediately dispersed. "General Gabriel" and the other leaders, one after another, were captured, tried, and hanged, the militia in strong force guarding them to execution. Since then, a disciplined guard, bearing the warning motto, " *"So ever to tyrants," the motto on the seal of Virginia. The gentleman who gave me the substance of this information, spoke of the Guard with an admiring and gratulatory tone, as "our little army." "But how is that?" I inquired; "does not our federal Constitution require that no State shall keep troops in time of peace? Is not your little army unconstitutional?" I could get no satisfactory reply; I fear it was hardly in good taste, under the circumstances, to make such an inquiry of a Virginia democrat. It was not till I had passed the guard, unchallenged, and stood at the door-way, that I perceived that the imposing edifice, as I had thought it at a distance, was nothing but a cheap

stuccoed building; nor would anything short of test by touch, have convinced me that the great state of Virginia would have been so long content with such a parsimonious pretense of dignity as is found in imitation granite and imitation marble. There is an instance of parsimony, without pretense, in Richmond, which Ruskin, himself, if he were a traveler, could not be expected to applaud. The rail-road company which brings the traveler from Washington, so far from being open to the criticism of having provided edifices of a style of architecture only fitted for palaces, instead of a hall suited to conflicts with hackney-coachmen, actually has no sort of stationary accommodations for them at all, but sets them down, rain or shine, in the middle of one of the main streets. The adjoining hucksteries, barbers'-shops, and bar-rooms, are evidently all the better patronized for this fine simplicity; but I should doubt if the rail-road stock would be much advanced in value by it. In the rotunda of the Capitol stands Houdon's statue of Washington. It was modeled from life, and is said to present the truest similitude of the American Great Man that is retained for posterity. The face has a lofty, serene, slightly saddened expression, as that of a strong, sensible man loaded, but not over-burdened, with cares and anxiety. A self-reliant, brave, able soul, with deep but subdued sympathies, comprehending great duties, calmly and confidently prepared to perform them. There is very little like a king, or a clergyman, or any other professional character-actor in it. In most of the portraits of Washington, he looks as if he were a great tragedian, or a high-priest; but this is a face that would satisfy and encourage

one in the engine-driver of a lightning train, or the officer of the deck in a fog off Cape Race; far-seeing, vigilant and fervid, but composed and perfectly controlled--the face of a man, wherever you found him--as a sailor, or a schoolmaster, or a judge, or a general--that you could depend upon to perform his undertakings conscientiously. The figure is not good; it struts, and has an air of nonchalance and ungentlemanly assumption. This was the fashion of the age, however, and education may have given it to the man, though his character, as seen with certainty in his face, is far superior to it. The grounds about the Capitol are naturally admirable, and have lately been improved with neatness and taste. Their beauty and interest would be greatly increased if more of the fine native trees and shrubs of Virginia, particularly the holly and the evergreen magnolias, were planted in them. I noticed these, as well as the Irish and palmated ivy, growing, with great vigor and beauty, in the private gardens of the town. On some high, sterile lands, of which there are several thousand acres, uninclosed and uncultivated, near the town, I saw a group of exceedingly beautiful trees, having the lively green and all the lightness, gracefulness and beauty of foliage, in the Winter, of the finest deciduous trees. I could not believe, until I came near them, that they were what I found them to be--our common red cedar (Juniperus Virginiana). I have frequently noticed that the beauty of this tree is greatly affected by the soil it stands in; in certain localities, on the Hudson river, for instance, and in the lower part of New Jersey, it grows in a perfectly dense, conical, cypress-like form. These, on the other hand, were square-headed, dense,

flattened at the top, like the cedar of Lebanon, and with a light and slightly drooping spray, deliciously delicate and graceful, where it cut the light. They stood in a soil of small quartz gravel, slightly bound with red clay. In a soil of similar appearance at the North, cedars are usually thin, stiff, shabby, and dull in color. I notice that they are generally finer here, than we often see them under the best of circumstances; and I presume they are better suited in climate. On a Sunday afternoon I met a negro funeral procession, and followed after it to the place of burial. There was a decent hearse, of the usual style, drawn by two horses; six hackney coaches followed it, and six well-dressed men, mounted on handsome saddle-horses, and riding them well, rode in the rear of these. Twenty or thirty men and women were also walking together with the procession, on the side-walk. Among all there was not a white person. Passing out into the country, a little beyond the principal cemetery of the city (a neat, rural ground, well filled with monuments and evergreens), the hearse halted at a desolate place, where a dozen colored people were already engaged heaping the earth over the grave of a child, and singing a wild kind of chant. Another grave was already dug, immediately adjoining that of the child, both being near the foot of a hill, in a crumbling bank--the ground below being already occupied, and the graves advancing in irregular terraces up the hill-side--an arrangement which facilitated labor. The new comers, setting the coffin--which was neatly made of stained pine--upon the ground, joined in the labor and the singing,

with the preceding party, until a small mound of earth was made over the grave of the child. When this was completed, one of those who had been handling a spade, sighed deeply and said, "Lord Jesus have marcy on us--now! you Jim--you! see yar; you jes lay dat yar shovel cross dat grave--so fash--dah--yes, dat's right." A shovel and a hoe-handle having been laid across the unfilled grave, the coffin was brought and laid upon them, as on a trestle; after which, lines were passed under it, by which it was lowered to the bottom. Most of the company were of a very poor appearance, rude and unintelligent, but there were several neatly-dressed and very good-looking men. One of these now stepped to the head of the grave, and, after a few sentences of prayer, held a handkerchief before him as if it were a book, and pronounced a short exhortation, as if he were reading from it. His manner was earnest, and the tone of his voice solemn and impressive, except that, occasionally, it would break into a shout or kind of howl at the close of a long sentence. I noticed several women near him, weeping, and one sobbing intensely. I was deeply influenced myself by the unaffected feeling, in connection with the simplicity, natural, rude truthfulness, and absence of all attempt at formal decorum in the crowd. I never in my life, however, heard such ludicrous language as was sometimes uttered by the speaker. Frequently I could not guess the idea he was intending to express. Sometimes it was evident that he was trying to repeat phrases that he had heard used before, on similar occasions, but which he made absurd by some interpolation or distortion of a word;

thus, "We do not see the end here! oh no, my friends! there will be a putrification of this body!" the context failing to indicate whether he meant purification or putrefaction, and leaving it doubtful if he attached any definite meaning to the word himself. He quoted from the Bible several times, several times from hymns, always introducing the latter with "in the words of the poet, my brethren;" he once used the same form, before a verse from the New Testament, and once qualified his citation by saying, "I believe the Bible says that;" in which he was right, having repeated words of Job. He concluded by throwing a handful of earth on the coffin, repeating the usual words, slightly disarranged, and then took a shovel, and, with the aid of six or seven others, proceeded very rapidly to fill the grave. Another man had, in the mean time, stepped into the place he had first occupied at the head of the grave; an old negro, with a very singularly distorted face, who raised a hymn, which soon became a confused chant--the leader singing a few words alone, and the company then either repeating them after him or making a response to them, in the manner of sailors heaving at the windlass. I could understand but very few of the words. The music was wild and barbarous, but not without a plaintive melody. A new leader took the place of the old man, when his breath gave out (he had sung very hard, with much bending of the body and gesticulation), and continued until the grave was filled, and a mound raised over it. A man had, in the mean time, gone into a ravine near by, and now returned with two small branches, hung with withered leaves, that he had broken off a beech tree; these were placed upright, one at the head, the other at the foot

of the grave. A few sentences of prayer were then repeated in a low voice by one of the company, and all dispersed. No one seemed to notice my presence at all. There were about fifty colored people in the assembly, and but one other white man besides myself. This man lounged against the fence, outside the crowd, an apparently indifferent spectator, and I judged he was a police officer, or some one procured to witness the funeral, in compliance with the law which requires that a white man shall always be present at any meeting, for religious exercises, of the negroes, to destroy the opportunity of their conspiring to gain their freedom. The greater part of the colored people, on Sunday, seemed to be dressed in the cast-off fine clothes of the white people, received, I suppose, as presents, or purchased of the Jews, whose shops show that there must be considerable importation of such articles, probably from the North, as there is from England into Ireland. Indeed, the lowest class, especially among the younger, remind me much, by their dress, of the "lads" of Donnybrook; and when the funeral procession came to its destination, there was a scene precisely like that you may see every day in Sackville-street, Dublin,--a dozen boys in ragged clothes, originally made for tall men, and rather folded round their bodies than worn, striving who should hold the horses of the gentlemen when they dismounted to attend the interment of the body. Many, who had probably come in from the farms near the town, wore clothing of coarse gray "negro-cloth," that appeared as if made by contract, without regard to the size of the particular individual to whom it had been allotted, like penitentiary uniforms. A few had a better suit

of coarse blue cloth, expressly made for them evidently, for "Sunday clothes." Some were dressed with laughably foppish extravagance, and a great many in clothing of the most expensive materials, and in the latest style of fashion. In what I suppose to be the fashionable streets, there were many more well-dressed and highly-dressed colored people than white, and among this dark gentry the finest French cloths, embroidered waistcoats, patent-leather shoes, resplendent brooches, silk hats, kid gloves, and There was no indication of their belonging to a subject race, but that they invariably gave the way to the white people they met. Once, when two of them, engaged in conversation and

looking at each other, had not noticed his approach, I saw a Virginia gentleman lift his cane and push a woman aside with it. In the evening I saw three rowdies, arm-in-arm, taking the whole of the sidewalk, hustle a black man off it, giving him a blow, as they passed, that sent him staggering into the middle of the street. As he recovered himself he began to call out to, and threaten them. Perhaps he saw me stop, and thought I should support him, as I was certainly inclined to: "can't you find anything else to do than to be knockin' quiet people round! You jus' come back here, will you? Here, you! don't care if you is white. You jus' come back here and I'll teach you how to behave--knockin' people round!--don't care if I does hab to go to der watch-house." They passed on without noticing him further, only laughing jeeringly--and he continued: "You come back here and I'll make you laugh; you is jus' three white nigger cowards, dat's what you be." I observe, in the newspapers, complaints of growing insolence and insubordination among the negroes, arising, it is thought, from too many privileges being permitted them by their masters, and from too merciful administration of the police laws with regard to them. Except in this instance, however, I have seen not the slightest evidence of any independent manliness on the part of the negroes towards the whites. As far as I have yet observed, they are treated very kindly and even generously as servants, but their manner to white people is invariably either sullen, jocose, or fawning. The pronunciation and dialect of the negroes, here, is generally much more idiomatic and peculiar than with us. As I write, I hear a man shouting, slowly and deliberately, meaning to say there: dah! dah! DAH!

Yesterday morning, during a cold, sleety storm, against which I was struggling, with my umbrella, to the post office, I met a comfortably-dressed negro leading three others by a rope; the first was a middle-aged man; the second a girl of, perhaps, twenty; and the last a boy, considerably younger. The arms of all three were secured before them with hand-cuffs, and the rope by which they were led passed from one to another; being made fast at each pair of hand-cuffs. They were thinly clad, the girl especially so, having only an old ragged handkerchief around her neck, over a common calico dress, and another handkerchief twisted around her head. They were dripping wet, and icicles were forming, at the time, on the awning bars. The boy looked most dolefully, and the girl was turning around, with a very angry face, and shouting, "O pshaw! Shut up!" "What are they?" said I, to a white man, who had also stopped, for a moment, to look at them. "What's he going to do with them?" "Come in a canal boat, I reckon: sent down here to be sold. --That ar's a likely gall." Our ways lay together, and I asked further explanation. He informed me that the negro-dealers had confidential servants always in attendance, on the arrival of the rail-road trains and canal packets, to take any negroes, that might have come, consigned to them, and bring them to their marts. Nearly opposite the post office, was another singular group of negroes. They were all men and boys, and each carried a coarse, white blanket, drawn together at the corners so as to hold some articles; probably, extra clothes. They stood in a

row, in lounging attitudes, and some of them, again, were quarreling, or reproving one another. A villainous-looking white man stood in front of them. Presently, a stout, respectable man, dressed in black according to the custom, and without any overcoat or umbrella, but with a large, golden-headed walking-stick, came out of the door of an office, and, without saying a word, walked briskly up the street; the negroes immediately followed, in file; the other white man bringing up the rear. They were slaves that had been sent into the town to be hired out as servants or factory hands. The gentleman in black was, probably, the broker in the business. Near the post office, opposite a large livery and sale stable, I turned into a short, broad street, in which were a number of establishments, the signs on which indicated that they were occupied by "Slave Dealers," and that "Slaves, for Sale or to Hire," were to be found within them. They were much like Intelligence Offices, being large rooms partly occupied by ranges of forms, on which sat a few comfortably and neatly clad negroes, who appeared perfectly cheerful; each grinning obsequiously, but with a manifest interest or anxiety, when I fixed my eye on them for a moment. In Chambers' Journal for October, 1853, there is an account of the Richmond slave marts, and the manner of conducting business in them, so graphic and evidently truthful that I omit any further narration of my own observations, to make room for it. I do this, notwithstanding its length, because I did not happen to witness, during fourteen months that I spent in the Slave States, any sale of negroes by auction. This must not be taken as an indication that negro auctions are not of frequent occurrence (I did not, so far as I now

recollect, witness the sale of anything else, at auction, at the South). I saw negroes advertised to be sold at auction, very frequently.

"The exposure of ordinary goods in a store is not more open to the public than are the sales of slaves in Richmond. By consulting the local newspapers, I learned that the sales take place by auction every morning in the offices of certain brokers, who, as I understood by the terms of their advertisements, purchased or received slaves for sale on commission. "Where the street was in which the brokers conducted their business, I did not know; but the discovery was easily made. Rambling down the main street in the city, I found that the subject of my search was a narrow and short thoroughfare, turning off to the left, and terminating in a similar cross thoroughfare. Both streets, lined with brick-houses, were dull and silent. There was not a person to whom I could put a question. Looking about, I observed the office of a commission-agent, and into it I stepped. Conceive the idea of a large shop with two windows, and a door between; no shelving or counters inside; the interior a spacious, dismal apartment, not well swept; the only furniture a desk at one of the windows, and a bench at one side of the shop, three feet high, with two steps to it from the floor. I say, conceive the idea of this dismal-looking place, with nobody in it but three negro children, who, as I entered, were playing at auctioneering each other. An intensely black little negro, of four or five years of age, was standing on the bench, or block, as it is called, with an equally black girl, about a year younger, by his side, whom he was pretending to sell by bids to another black child, who was rolling about the floor. "My appearance did not interrupt the merriment. The little auctioneer continued his mimic play, and appeared to enjoy the joke of selling the girl, who stood demurely by his side. " 'Fifty dolla for de gal--fifty dolla--fifty dolla--I sell dis here fine gal for fifty dolla,' was uttered with extraordinary volubility by the woolly-headed urchin, accompanied with appropriate gestures, in imitation, doubtless of the scenes he had seen enacted daily in the spot. I spoke a few words to the little creatures, but was scarcely understood; and the fun went on as if I had not been present:

so I left them, happy in rehearsing what was likely soon to be their own fate. "At another office of a similar character, on the opposite side of the street, I was more successful. Here, on inquiry, I was respectfully informed, by a person in attendance, that the sale would take place the following morning at half-past nine o'clock. "Next day I set out accordingly, after breakfast, for the scene of operations, in which there was now a little more life. Two or three persons were lounging about, smoking cigars; and, looking along the street, I observed that three red flags were projected from the doors of those offices in which sales were to occur. On each flag was pinned a piece of paper, notifying the articles to be sold. The number of lots was not great. On the first was the following announcement:--'Will be sold this morning, at half-past nine o'clock, a Man and a Boy.' "It was already the appointed hour; but as no company had assembled, I entered and took a seat by the fire. The office, provided with a few deal forms and chairs, a desk at one of the windows, and a block accessible by a few steps, was tenantless, save by a gentleman who was arranging papers at the desk, and to whom I had addressed myself on the previous evening. Minute after minute passed, and still nobody entered. There was clearly no hurry in going to business. I felt almost like an intruder, and had formed the resolution of departing, in order to look into the other offices, when the person referred to left his desk, and came and seated himself opposite to me at the fire. " 'You are an Englishman,' said he, looking me steadily in the face; 'do you want to purchase?' " 'Yes,' I replied, 'I am an Englishman; but I do not intend to purchase. I am traveling about for information, and I shall feel obliged by your letting me know the prices at which negro servants are sold.' " 'I will do so with much pleasure,' was the answer; 'do you mean field-hands or house-servants?' " 'All kinds,' I replied; 'I wish to get all the information I can. "With much politeness, the gentleman stepped to his desk, and began to draw up a note of prices. This, however, seemed to require careful consideration; and while the note was preparing, a lanky person, in a wide-awake hat, and chewing tobacco, entered,

and took the chair just vacated. He had scarcely seated himself, when, on looking towards the door, I observed the subjects of sale--the man and boy indicated by the paper on the red flag--enter together, and quietly walk to a form at the back of the shop, whence, as the day was chilly, they edged themselves towards the fire, in the corner where I was seated. I was now between the two parties--the white man on the right, and the old and young negro on the left--and I waited to see what would take place. "The sight of the negroes at once attracted the attention of Wideawake. Chewing with vigor, he kept keenly eying the pair, as if to see what they were good for. Under this searching gaze, the man and boy were a little abashed, but said nothing. Their appearance had little of the repulsiveness we are apt to associate with the idea of slaves. They were dressed in a gray woolen coat, pants, and waistcoat, colored cotton neckcloths, clean shirts, coarse woolen stockings, and stout shoes. The man wore a black hat; the boy was bareheaded. Moved by a sudden impulse, Wide-awake left his seat, and rounding the back of my chair, began to grasp at the man's arms, as if to feel their muscular capacity. He then examined his hands and fingers; and, last of all, told him to open his mouth and show his teeth, which he did in a submissive manner. Having finished these examinations, Wide-awake resumed his seat, and chewed on in silence as before. "I thought it was but fair that I should now have my turn of investigation, and accordingly asked the elder negro what was his age. He said he did not know. I next inquired how old the boy was. He said he was seven years of age. On asking the man if the boy was his son, he said he was not--he was his cousin. I was going into other particulars, when the office-keeper approached, and handed me the note he had been preparing; at the same time making the observation that the market was dull at present, and that there never could be a more favorable opportunity of buying. I thanked him for the trouble which he had taken; and now submit a copy of his price-current: