A Study of Prison Conditions in North Carolina:

Electronic Edition.

North Carolina State Board of Charities and Public Welfare

Funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Don Chalfant

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc. and Melissa Meeks

First edition, 2002

ca. 80K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2002.

Source Description:

(series) Bulletin of the North Carolina State Board of Charities and Public Welfare

(cover) A Study of Prison Conditions in North Carolina

North Carolina State Board of Charities and Public Welfare.

25 p.

RALEIGH, N. C.

North Carolina State Board of Charities and Public Welfare

1923

Call number Cp 365 C58s (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

Appears in Vol. 6, no. 1 (First quarter, Jan.-Mar. 1923)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Prison administration -- North Carolina.

- Prison discipline -- North Carolina.

- Prisons -- North Carolina.

- Prisons -- Government policy -- North Carolina.

- Prisoners -- North Carolina.

- Chain gangs -- North Carolina.

- Prisons -- North Carolina -- Evaluation.

- Prisons -- Law and legislation -- North Carolina.

- Punishment in crime deterrence -- North Carolina.

Revision History:

- 2003-02-28,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2002-11-06,

Melissa Meeks

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2002-04-02,

Don Chalfant

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2002-01-01,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

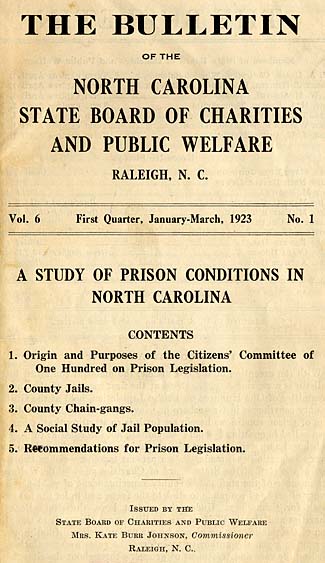

[Cover Page Image]

THE BULLETIN

OF THE

NORTH CAROLINA

STATE BOARD OF CHARITIES

AND PUBLIC WELFARE

RALEIGH, N. C.

Vol. 6 First Quarter, January-March, 1923 No. 1

A STUDY OF PRISON CONDITIONS IN

NORTH CAROLINA

CONTENTS

- 1. Origin and Purposes of the Citizens' Committee of One Hundred on Prison Legislation.

- 2. County Jails.

- 3. County Chain-gangs.

- 4. A Social Study of Jail Population.

- 5. Recommendations for Prison Legislation.

CONTENTS

ISSUED BY THE

STATE BOARD OF CHARITIES AND PUBLIC WELFARE

MRS. KATE BURR JOHNSON, Commissioner

RALEIGH, N. C.

Page 2

THE BULLETIN

- W. A. BLAIRChairman, Winston-Salem. . . . .Term expires April 1, 1923

- CAREY J. HUNTER, Vice-Chairman, Raleigh. . . . .Term expires April 1, 1927

- A. W. MCALISTER, Greensboro. . . . .Term expires April 1, 1923

- REV. M. L. KESLER, Thomasville. . . . .Term expires April 1, 1925

- MRS. THOMAS W. LINGLE, Davidson. . . . .Term expires April 1, 1925

- MRS. WALTER F. WOODARD, Wilson. . . . .Term expires April 1, 1927

- MRS. J. W. PLESS, Marion. . . . .Term expires April 1, 1925

Members of State Board of Charities and Public Welfare

- MRS. KATE BURR JOHNSON. . . . .Commissioner

- MISS NELL BATTLE LEWIS. . . . .Secretary

- ROY M. BROWN. . . . .Field Agent

- MISS MARY G. SHOTWELL. . . . .Bureau of Child Welfare

- MISS M. EMETH TUTTLE. . . . .Bureau of Child Welfare

- HARRY W. CRANE. . . . .Psychopathologist

- HOWARD W. ODUM. . . . .Consulting Expert

- MISS FANNIE DARK. . . . .Chief Clerk

- MISS CLARA HODGES. . . . .Stenographer and Librarian

- MRS. ARTHUR HOLDING. . . . .Stenographer

Executive Staff

January-March, 1923

Admitted to U. S. mails as second-class matter.

INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT

With the exception of the last article, the material contained in this bulletin is a reprint of papers read at the first meeting of the Citizens' Committee of One Hundred on Prison Legislation, held at the Guilford County courthouse in Greensboro on November 24, 1922. The description of prison conditions herein set forth is so startling that it has even been called in question by some individuals, not informed as to the facts, as being the unverified report of a single investigator. This is not true. Every inspection was made by two persons together--either two members of the staff of the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare or one member of the staff and a county superintendent of public welfare. Every effort has been made to stick to the facts, and to let the bare facts speak for themselves. Under the present laws, the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare can do little more than call to the attention of the public existing abuses in our prison system. Shall not some agency be given the authority to enforce the rules and regulations regarding the care and treatment of prisoners throughout the State?

The decision rests with the people of North Carolina.

Page 3

ORIGIN AND PURPOSES OF THE CITIZENS' COMMITTEE

OF ONE HUNDRED ON PRISON LEGISLATION

1. HISTORICAL REVIEW

Many strands have entered into the making of this Citizens' Committee of One Hundred on Prison Legislation. Some go far back into the past history of this State, and it would take us too far afield to trace them out at this time. We can only take time now to call attention to the notable effort made in 1917 to bring about an improvement in the prison system. That movement, which was led by Mr. R. F. Beasley, and ably supported by Dr. J. H. Pratt, both members of our present committee, and other influential citizens, contemplated sweeping changes in the existing statutes, which, if put into effect, would have placed this State far ahead of other southern states in its methods of dealing with crime. But five years ago there was little popular interest in a movement of this kind. The people in general did not rally to the support of the measures submitted to the Legislature, and as a result the bills finally enacted into law were to a large extent modified and shorn of their power.

The World War and the effects following in its train drew attention away from the prison problem. The legislative assemblies of 1919 and 1921 were not confronted with an organized effort to carry to completion the constructive prison movement begun in 1917. But the influence of the work carried on five years ago has not been lost. The interest aroused at that time may have seemed to lie dormant, but in reality it was gathering strength while awaiting this present occasion when representative leaders of the State have come together to think through this problem of dealing with criminals and crime. Without the very definite efforts made to improve our prison system in 1917, this meeting of the Citizens' Committee of One Hundred on Prison Legislation would hardly have been possible.

But while this Citizens' Committee has its roots deeply imbedded in the past, its more immediate origin dates from the annual meeting of the North Carolina Conference for Social Service held in Greensboro last March. Or speaking more accurately, one of the chief strands that entered into its making must be traced back to the interest of a church in the welfare of two boys who were inmates of a county convict camp. I refer to the Men's Club of the Church-by-the-Side-of-the-Road, the members of which, in their effort to be a "Friend o' Man," succeeded in having paroled to them these boys who otherwise would have spent a year with hardened prisoners. Out of this experience Mr. A. W. McAlister presented a paper at the last meeting of the State Conference for Social Service in which he urged the need for a wider extension and improvement of the parole system. As a result of the impression made by this paper, the Conference appointed a committee (1) to make a

Page 4

careful study of State, county, and municipal prisons, prison, camps, prison farms, and care of prisoners throughout the State, and (2) to draft a bill or bills to the Legislature during its next session. It is too significant to pass over without comment that this broad undertaking grew out of the awakened conscience of a church interested in putting into practical effect Christ's ideals of service. And our hope for the ultimate success of this movement is strengthened by the fact that the wider church has been quick to catch this same vision, as appears from the wholehearted indorsement of the work of the Citizens' Committee by the various church conferences that have recently met throughout the State.

The committee appointed by the Conference for Social Service met in Raleigh on April 19 with Mrs. Kate Burr Johnson, the State Commissioner of Charities and Public Welfare. At this meeting it was felt that the far-reaching issues involved in the care and treatment of prisoners demanded the combined judgment of a large and influential group of people representing the various sections of the State as well as its chief interests and organizations. Accordingly it was decided to organize a Citizens' Committee of One Hundred on Prison Legislation, whose task it would be to help study this problem and to share the responsibility of determining what changes, if any, are needed in dealing with offenders against the law.

This Citizens' Committee during this past summer was divided into subcommittees for the study of different phases of the prison problem. Today these subcommittees will submit their reports, which will include recommendations as to needed legislative and administrative changes. In order that this committee should be in possession of facts upon which to base their judgments, various members have during the past few months made personal visits to jails and prison camps. In addition, a State-wide study of prison conditions has been carried on by Mr. W. B. Sanders in collaboration with the State Department of Public Welfare. At this meeting the facts secured are to be presented for our information. It will, of course, be impossible in such a brief meeting as this to come to a definite agreement concerning all the recommendations that will be made by the various subcommittees. Enough will be accomplished if we get these reports before us and through discussion bring out the opinions of different members of the Citizens' Committee. It will be possible then to refer these reports to a special committee on policy and program, which can take time to study them thoroughly and draft the legislation that is to be submitted, when finally approved by the Citizens' Committee, to the General Assembly at its meeting in January.

2. STATEMENT OF AIMS AND PRINCIPLES

But however important is the historical and administrative side of the work of the Citizens' Committee, of equal interest is a clear statement of our point of view and our basic principles upon which we can

Page 5

all agree, although there may well be differences of opinion as to methods of procedure. As I conceive it, these may be briefly summed up as follows:

1. Our fundamental interest is the reduction of crime in this State. We are appalled at the apparently increasing disregard of law which results in crimes that are a constant menace to life and property. In order to lessen crime we believe that society must express its disapproval of criminal conduct in unmistakable ways. Crime is a festering sore that cannot be tolerated or ignored. We disclaim all maudlin sympathy for those who cannot or will not obey the law. The administration of justice must be swift and sure, and commensurate with the nature of the crime committed.

2. We insist upon working out methods of punishment that will be effective both in reducing the amount of crime and in restoring to normal life those who have gone wrong. The failure of present methods of dealing with criminals is notorious. In South Carolina we are told that 47 per cent of prisoners in county jails and 40 per cent of the inmates of the State Prison have served time before. In general, this is in accord with the experience of many other states. In our own State of North Carolina, of 162 prisoners recently studied in county jails, 30.2 per cent admitted that they had been in jail before. Any institution that fails in 40 per cent, or even in 30 per cent, of its cases should be called into serious question. Instead of blindly following traditional methods of punishment which are known to be ineffective, we urge that the State make every effort to establish a penal system that will stand the test of efficiency in producing the desired results.

3. We take our stand against methods of treatment of criminals that tend to destroy self-respect, degrade character, and violate all principles of common decency and humanity. Punishment is justified only on the grounds that it protects society and leads to the reformation of the criminal. When punishment includes unnecessarily harsh discipline, inadequate diet, unsanitary living quarters, long-continued idleness, and deprivation of all suitable educational and religious influences, it accomplishes neither purpose, for the offender is turned back to society in a worse state than before his imprisonment. Such punishment is plainly out of touch with Christian faith and practice, and should not be tolerated in a Christian state.

4. We believe that punishment to be effective must be based upon full knowledge of each individual offender. Modern science has given us an understanding of criminal nature and habit never dreamed of in the past. In the light of the scientific progress that has been made, it is as inexcusable to put all criminals through the same prison routine as it would be to administer the same medicine to all the patients in a hospital regardless of the nature of their disease. We see no hope of bringing about the reformation of prisoners until means are provided

Page 6

for their thorough examination, both mental and physical, together with the development of facilities for the separate treatment of different types of offenders.

5. It is our conviction that a problem so complex as the one we are facing can best be met by working out a comprehensive plan for a thoroughly modern penal system which shall serve as a goal toward which we can work over a period of years. For the development of such a plan there will be required patient study and careful investigation of the best systems in operation elsewhere as well as a critical examination of the peculiar needs of our own State. Toward the accomplishment of such a result, our work up to the present has been only a beginning. We believe that an undertaking of this kind might well become a future task of this Citizens' Committee and express the hope that ways and means may be found to carry it out as expeditiously as possible.

Page 7

COUNTY JAILS

The basis of all constructive change is a thorough knowledge of present facts and present conditions. Future laws and future methods must be based upon those of the present, just as those of the present grew out of the past. Any improvement, therefore, which the Citizens' Committee may hope to bring about in prison legislation or prison administration must be based upon an adequate knowledge of the comparative efficiency or inefficiency of our present system of penal treatment. This meeting today is the first attempt ever made in this State to work out an ideal yet practical prison system, based upon a Statewide survey of prison conditions. Before the sixteen special committees offer recommendations for changes in our prison legislation, we should, first of all, have a vivid picture of present prison conditions in North Carolina.

Among other things which we inherited from our English forefathers in colonial days was the common jail. The county jails which sprang up in the American Colonies were exact counterparts of the English jails of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with their reeking filth and vermin-infested cells--veritable breeding places of vice and crime. While other institutions have grown and taken on new life with the introduction of new ideas, the county jail has remained practically unchanged. There is, perhaps, no social institution in our State today which is so generally neglected as this surviving relic of an outgrown past.

The modern reader of history is often horrified at the accounts of living conditions in the English jails of the Middle Ages, where disease was rife, and where the dungeon, the thumb-screw, and the rack were favorite methods of torture. But the reader would be more horrified still if he knew that many of these conditions exist in the county jails of our State today, and these conditions are allowed to exist because the people do not know what is going on behind prison bars.

In a recent study of some thirty county jails in our State four dungeons were found, three of which had been used within the past few weeks. One of these dungeons has concrete walls, concrete ceiling and floor, and a heavy iron door, with no window and no light or ventilation whatsoever, except such as might find its way through the narrow crack under the door. In this concrete vault, 6 × 8 × 10 feet, only a few months ago seventeen negroes were confined at one time by the jailer, according to his own statement. The prisoners were too crowded to sit down, and were compelled to stand. That classic illustration of prison cruelty, the Black Hole of Calcutta, where 123 English prisoners lost their lives through suffocation, had two small windows in it. This dungeon has none. It is still being used as a place of punishment. No bedding is furnished. A prisoner confined in it is usually kept in total

Page 8

darkness for two days at a time with nothing to sleep on but the concrete floor. Please bear in mind that this punishment is not inflicted by a court, but by the jailer, who assumes such authority to himself without any basis in law.

In another county jail an 11-year-old white boy was confined in jail for about six weeks for breaking a window pane and a lamp shade in the county home. Several times this boy was locked up in the jail dungeon in total darkness for three or four hours at a time. With a child's instinctive fear of the darkness, and his vivid imagination, what punishment could have been more severe? The jailer, who, by the way, was a woman, seemed to think she had done nothing out of place, and accepted it in a matter-of-fact way as part of the day's work.

In another jail dungeon, not quite totally dark, a prisoner was confined for four months for fighting another prisoner.

Four other jails among the thirty visited had devices for closing the windows and making the rooms totally dark as a means of punishment. Some of these are used occasionally.

In the State Prison there are five or six dungeons on the basement floor, just below the tier of cells where fourteen prisoners are awaiting execution. These dungeons have solid iron doors, which render the cells totally dark. Prisoners are kept in these dungeons from two to six days at a time as punishment, usually for fighting. Corporal punishment is sometimes used and the superintendent of the State Prison thinks this is a more humane punishment than incarceration in such cells as they have at the State Prison. These conditions are in no wise to be regarded as reflecting on the present management of the State Prison. They are a part of the system which has been handed down from the past. In calling attention to these conditions it would be a great mistake to leave the impression that reform should consist merely in changes in methods of discipline. The real problem goes much deeper, and can be solved only by the introduction of a system of prison industries which would include proper instruction for all inmates capable of receiving it. Thus would be avoided the moral deterioration and the resulting bad conduct on the part of the prisoners, which, under the present system, makes severe discipline necessary.

In at least three county jails prisoners are sometimes whipped as a means of punishment. A few weeks ago a member of the staff of the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare was looking through the jail in one of our southern counties. In the negro women's ward a negro girl about 17 years old was lying in bed with a bloody bandage tied around her head. In the presence of the jailer's wife the girl said that the previous day the jailer had beaten her with his blackjack and had kicked her into a corner "just like she was a dog." The jailer's wife, upon being questioned, admitted that her husband had beaten the girl for cursing her, and when the jailer was questioned a little later, he, too, admitted the beating. Prisoners on the floor below told the visitor

Page 9

the jailer had "beat hell out of her." The sheriff's attention was called to the matter through a letter, whereupon the jailer's wife flatly denied her previous statements to the visitor, and the jailer himself, a large man, weighing well over two hundred pounds, and noted all over the county for his bravery, declared that the girl had attacked him and he had to defend himself. Truly, a brave jailer was that, who armed with pistol and blackjack had to defend himself so vigorously against the alleged attack of a 17-year-old negro girl, whose only weapon was her tongue. I mention this instance of prison cruelty to show that abuses cannot be remedied merely by calling the attention of the county authorities to them. Only by arousing the public sentiment of the entire State can we hope to rid our county jails of such conditions as I have described.

Among other instances of the beating of prisoners by jailers which have come to the attention of the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare is the case of an old white woman, temporarily confined in jail because of drug addiction. It was reported that she was given a severe beating with a strap by the jailer when she became unusually noisy after the drug was taken from her. This old woman is now so feeble she is in the county home. Such treatment is not only a violation of the law, but is an outrage against every principle of justice and humanity. The following ruling by the Attorney-General is unmistakably clear on this point:

MRS. CLARENCE A. JOHNSON,

State Commissioner Public Welfare, Raleigh, N. C.

DEAR MADAM:--You asked this office to state fully whether or not the keeper of a county jail has in any way authority to discipline the prisoners confided to his care. The jailer in North Carolina is simply an employee of the sheriff of the county whose jail he keeps. He is not a public officer, but in all his acts in the scope of his authority represents the sheriff. Our court has held with reference to county convicts sentenced to hard labor upon the public roads that they are not subject to flogging by the officer having them in charge. Section 1361 of Consolidated Statutes authorizes the board of commissioners of a particular county to enact all needful rules and regulations for the successful working of convicts upon the public roads. This, of course, does not confer any authority upon the county commissioners to make rules and regulations for the discipline of prisoners untried and imprisoned in the county jail temporarily until trial on account of their inability to give bond. The sheriff himself has no authority to discipline prisoners of either of the latter classes. It is very clear, then, that when the jailer goes beyond the necessary measures for preventing the escape of prisoners committed to his care, or the necessary precautions for his own safety, he offends against the law. In no sense and in no way has he authority to discipline the prisoners committed to him as an employee of the sheriff for safekeeping.

Yours very truly,

JAMES S. MANNING,

Attorney-General.

Page 10

On the whole the laws upon our statute books regarding the care and treatment of prisoners are humane, but these laws are generally disregarded. In many instances the jailers do not know the laws relating to their duties.

Among some of the most important requirements in regard to county jails are the following:

1. Plans for new jails must be approved by the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare. County commissioners, as a rule, are ignorant of this provision.

2. Every county jail shall be provided with at least five separate apartments for prisoners. Only a few jails have five or more apartments, the majority having only three or four apartments. Two jails recently visited had only one apartment, so that there were no provisions whatever for separation of races or sexes. Some of the jails are badly crowded. In one jail twenty negroes were confined in six cells, while in another jail six negroes were locked up in one cell where there were only four bunks, and one of those broken.

3. The races and sexes must be kept separate. In four counties the whites and blacks were actually confined together at the time of the visit. In one instance a white woman was confined in the same cell apartment with an insane negro woman. In another jail when women are confined they must be kept in the jailer's corridor. There are no toilets in the jailer's corridor, so that the women are compelled to use buckets, with no privacy except such as darkness might afford. The judge refuses to send white women to this jail, but negro women are sometimes sent.

4. Every prisoner within forty-eight hours after his admission to any jail must be given a thorough physical examination. Two county physicians in the State claim to be fulfilling the law in this respect. In some counties prisoners are examined for venereal disease within a week or ten days, and if infected with disease, are treated. Several county physicians have stated that they did not know this law was upon the statute books; others explain their neglect by saying this physical examination of prisoners is unnecessary. In most instances the county physicians visit the jail only upon call, after the prisoner has become sick enough to be confined to his bed.

5. Sick and infectious prisoners shall be kept separate from the other prisoners. This law is directly dependent for its enforcement upon the physical examination of prisoners by the county physician, as stated above. Without such examination it is impossible to tell what prisoners are diseased. That the enforcement of this law is extremely important is brought out in the following description of a typical jail in Eastern North Carolina:

"There were twenty negro men in the negro ward. Nine of these negro prisoners were being treated for venereal disease by the county health officer, and one prisoner was diagnosed as a positive tubercular. The diseased men were mingling freely with those not infected, and no attempt at segregation

Page 11

was made. In fact, the jail had no separate ward where the diseased men could be treated. In some of the cells four men were sleeping--the tubercular prisoner along with the rest--thus allowing to each man about 63 cubic feet of air space, an amount far too small when compared with the minimum set by the State Board of Health of 600 cubic feet of air space per prisoner. The window area of the cell compartments, which should have been one-fifth of the total floor area, was only one-nineteenth of the floor area. The cells were in semi-darkness at midday, and such light and ventilation as they had was obstructed by a high board fence. One window was almost totally closed by a mulberry bush growing alongside it. There were two lavatories for the twenty negroes, and no towels except some meal sacks. The diet consisted of soggy rice and baker's bread for breakfast, and cabbage and fat meat for the other meal. The dieting fee was only forty cents a day."

6. Each prisoner shall be provided with a clean mattress or tick, sheets, and blankets or quilts. In six county jails visited recently no mattress of any kind was provided. The majority of the jails use cotton or straw mattresses. A few jails still have canvas hammocks. In only one jail were sheets found. The bed clothing as a rule is indescribably filthy.

7. Each prisoner shall be required to have not less than one general bath every week. Nine county jails recently visited had no bathing facilities whatever; three others had only tin basins or tubs. In some counties where the tubs or showers were located in the jailer's corridor the prisoners complained of not being allowed to take a bath in several weeks. Few jails have arrangements for providing hot water for bathing purposes. In a number of jails the plumbing had been out of order for months, and no attempt made to remedy it. In one case the plumbing had been out of order for several years.

Jails as a rule are miserably kept. The floors are seldom swept and still more rarely scoured. Many are in semi-darkness at midday. Crowded together, as prisoners frequently are, in these dark, dirty cells, with wholly inadequate toilet facilities, compelled always to breathe air laden with the sickening prison odor, and fed upon the cheapest and coarsest food with never a chance to exercise, and constantly exposed to infection from syphilis, gonorrhea, and tuberculosis--it is little wonder that these men come out with a grudge against society and the fixed determination to get even. Most of the prisoners are only awaiting trial. Some of them will be found innocent.

There are a few jails which stand out in striking contrast to this dark picture which has been painted above. The Wake County jail and the Rowan County jail are as clean as a hospital, and have no prison odor about them. The floors of the Rowan County jail are scoured every morning. The State Prison is also scrupulously clean.

In four of the county jails Kangaroo Courts were found. A Kangaroo Court is an organization among the prisoners with three objects in view:

a. To raise money for buying luxuries, such as sugar, cigarettes, safety-razor blades, and playing cards.

Page 12

b. To enforce certain rules in regard to the cleanliness of the jail and the comfort of the prisoners.

c. To furnish amusement and sport.

Each prisoner on admission to jail is assessed a fee of from twenty-five cents to a dollar by the other prisoners. The penalty for refusal or inability to pay, or for violation of the rules of the Kangaroo Court, is from five to one hundred licks with a belt, or from five cents to a dollar. A new prisoner who has the misfortune to be "broke" is held over a barrel or a bunk and strapped. It is a gala day for the other prisoners when a bunch of penniless "hoboes" are brought into jail. Such punishment of prisoners by other prisoners either by fines or by strapping is of course extra-legal, and frequently is subject to cruelty and abuse. In one instance the jailer was reported as being not only in sympathy with it, but was credited with being the head of the Kangaroo Court. In two other instances, the jailers denied all knowledge of the existence of such organizations in their jails. In all four instances the original set of rules and regulations were secured from the "officers" of the Kangaroo Courts.

During the past summer negro men carried the keys to two county jails. In at least one of these jails the negro had free access to all wards, including that for white women. Since that time, however, this negro jailer has been replaced. So far as we know, the other negro still carries the keys to his jail. In many jails there are negro jail helpers. When a negro jailer carries the keys, or when negro helpers have free access to the women's wards, the embarrassing position in which the women may be placed is seen in the following report of conditions as they existed in a county jail last summer:

"There was no privacy for the women prisoners--white or black. When visitor entered the negro women's ward a negro girl was lying half-clothed on a blanket at the far end of the prisoners' corridor within full view of the negro jail helpers. Another negro woman was vainly trying to take a bath in the little privacy she could secure by hanging a blanket across the bars. In the white women's ward several of the women were lying on the blankets on the floor of the prisoners' corridor. One girl was bare almost to the waist when the negro helper brought the food, and she had covered up her face and breast as best she could lying face-forward on the floor. At the first opportunity she ducked for a cell to get more clothing."

Buncombe County has recently adopted a more enlightened method of treating the woman offender, which clearly demonstrates that such conditions as described above need not exist. Four months ago an entirely separate ward for women prisoners was set aside in the Buncombe County jail, with a full-time matron in charge. The women prisoners do their own cooking and housekeeping, and have the freedom of the enclosed yard during the day, being confined in their cells only at night. This ward has none of the atmosphere of the common jail. It is true that the floors of this old section of the jail are in bad condition, the

Page 13

walls need repairing and painting, and a number of window-panes are out; yet somehow the matron, Mrs. Williams, has given a home-like atmosphere to the place. As one sits in the combined kitchen and dining-room and chats with the group he forgets that these are what the world calls bad women. Whatever the offense may be, Mrs. Williams always takes sides with her girls, believes in them, and they in turn confide in her. The girls go out from such an institution with an increased faith in their own ability to succeed and go straight, and many are writing back to the matron that they are making good. Truly this matron has caught the spirit of Christ, who said unto the woman taken in sin: "Neither do I condemn thee; go and sin no more."

The abuses described above in this report are not confined, as some might think, to a few isolated counties. Some of the worst conditions have been found in the counties usually ranked among the first in the State in wealth, in education, and in general progress. While these counties have not been named in this report, they can be furnished upon request by the State Department of Public Welfare or the Conference for Social Service if there is a legitimate reason for doing so.

Page 14

COUNTY CHAIN-GANGS

Forty-nine of the counties of the State maintain forces of prisoners who work on the public roads, and are usually termed chain-gangs. These forces vary in number from two recently reported from Franklin County to two hundred in Forsyth.

DISCIPLINE

These prisoners are worked under the direction of the board of county commissioners usually, sometimes of the county road commission. In most counties they are under the immediate supervision of an officer known sometimes as supervisor, sometimes as superintendent of the camp. In some counties such immediate supervision is vested in the highway engineer or superintendent of construction and maintenance, who does not live in the camp with the men, and who, in turn, delegates the actual supervision and discipline of the force to the ordinary guards. The senior guard from the point of view of service is the head of the camp.

The most common wage for a guard is around fifty dollars per month. Such a wage, coupled with the class of work that a guard on the typical chain-gang must do, does not often attract the type of man who is fit to have charge of other men. The guard is usually without even an elementary education, often practically illiterate. He is ignorant, of course, of any method of controlling men, except force. The supervisor is often a man who on account of a little superior intelligence, or devotion to duty, or mere length of service, has been promoted from the ranks of the guards.

The majority of prisoners on county chain-gangs are worked in stripes under armed guards. A large percentage are worked in chains; Nearly every camp has a small number of trusties--generally called "trustees" by supervisors and guards--who are not in stripes, are not chained or guarded, and have considerable freedom. The law provides that certain offenders may be worked in stripes and that certain others may not be. Most of the counties report that they obey this law. Some do not. At least one county has a system of its own. Men are put in plain clothes as a reward for good behavior, the supervisor being the judge as to who shall wear stripes.

The methods of discipline most common in chain-gangs are loss of time for bad behavior, confinement and flogging. Of these the most common apparently is flogging. At least two counties, New Hanover and Rockingham, use dark cells--Rockingham exclusively, and New Hanover for first offenses. The dark cell at the Rockingham County camp was seen by two representatives of the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare early in October. It is nineteen inches by nineteen and a half inches by six feet. It is constructed of heavy oak boards and

Page 15

partially lined with sheet-iron. There is an opening in the floor six inches in diameter and several inch auger holes in the top. A man placed in this cell cannot sit down or raise his hands from his sides. The limit of time that a man may be kept in this place is thirty-six hours. The present guards do not remember having kept any one in for more than twelve hours. On the day of the visit a man had been so confined for a half day, and another man had been similarly punished the day before. The offense with which these men were charged was fighting.

Flogging has been abolished as a legal method of prison discipline in every enlightened country in the world except a few of the Southern States. Of these Virginia, Alabama, Tennessee and Texas forbid it. It persists as the usual method in North Carolina. The law provides that the county authorities may make necessary rules for the discipline of prisoners working in chain-gangs. And the Supreme Court has said that unless specific rules have been enacted by the county commissioners, flogging is unlawful. Such rules have been enacted in only two or three counties, so far as the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare has been able to learn. Prisoners are whipped in nearly every county that maintains a chain-gang. They are whipped for trivial offenses. One county commissioner naively boasted a few days ago that swearing is not allowed on the chain-gangs in his county. If a prisoner swears he is whipped. Not only is flogging common throughout the State, but brutal beatings are not uncommon.

The flogging of prisoners in our county road camps has placed North Carolina in a rather unfavorable light among other neighboring states. In a letter dated August 29th, the Secretary of the American Prison Association called to the attention of our State Commissioner of Charities and Public Welfare a particularly brutal beating of a prisoner in a certain county convict camp. In this case the victim, a negro boy seventeen years old, was confined for two weeks after the beating in a hospital in New York City. The boy claims that he was beaten by the guards at this camp on three separate occasions while being held face downward over a barrel by other prisoners, and that afterwards he was strung up by his wrists to a signboard on the road for two or three hours, his feet being lifted so they could scarcely touch the ground. The representative who saw the negro in the hospital writes as follows:

"There is evidence of brutal treatment on his wrists and legs that will remain for all time in the form of scars. On each wrist at the outer base of the thumb, deep holes were worn in the flesh by the handcuffs, as the result of the hanging. The bandages were removed from the right wrist, but there remained a large scar with healthy scab. The left wrist is still bandaged, and the boy says that when let down from the signpost the flesh was entirely worn away and that he could see 'the leaders,' meaning the cords or sinews. By courtesy of the nurse the bandages were removed from the buttocks and revealed two scars that had healed until the contour of the flesh was normal. On each side are great scars, that if round would measure three inches in diameter."

Page 16

The county health officer stated to a representative of the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare that he was away on a vacation at the time of the beating, but when on his return he saw the boy after several beatings all the skin had been removed wherever the strap had struck the boy's body. The excuse given for such brutal treatment was that the boy refused to work. After flogging failed to make the boy work the guard handcuffed his arms around a tree so that he was compelled to stand up until the other prisoners returned to camp at sundown. The boy claims he was sick and unable to work on account of weakness through taking medicine prescribed by the county physician. Whenever a prisoner is flogged in that county today the county health officer must be present to see that the flogging is done according to certain regulations laid down by the county commissioners.

HOUSING

Three types of prison camps are in use for county chain-gangs in the State. The most common perhaps is the steel cage on wheels. This has the advantage of being easily moved from place to place, and of making it unnecessary to chain the men. The only protection against storm, however, is to let down heavy canvas covers over the sides. If they are let down for a storm early in the night, usually no one troubles himself to put them up again in case the storm subsides before morning. In the meantime the eighteen men crowded inside must suffer for want of ventilation. Moreover, the men are often confined in the cages on rainy days and Sundays, without exercise and with scarcely room to do anything except lie in their bunks. Next in number are wooden buildings. These are of various types. Sometimes a house built for some other purpose is adapted to the use of the camp. But whatever the type of building, the interior arrangement is much the same. The men sleep in continuous rows of double bunks. Often they are in two tiers, one above the other. Occasionally tents are used. In both of the last two types of camp the men are chained. An exception is made in the case of a few trusties.

SANITARY CONDITIONS

The beds in the typical camp are dirty. The regulation that prisoners must be furnished night clothes is ignored or obeyed in a most haphazard way. The sanitary conditions about the kitchen are often little better. At a camp in one of the wealthier counties, when visited by a representative of the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare, food was regularly passed out at an open unscreened window of the kitchen over a barrel of slop around which the flies were literally swarming. The following extracts are from reports on county prison camps by various members of the staff of the Commissioner of Public Welfare:

"The screen doors were wide open and the dishes and clothes covered with flies. The cage was indescribably filthy."

Page 17

"Three of these were sick men, another the cook, and the fifth a man assisting around the camp. Two of the sick men were confined in one cage, the third one was in an old house that is used as a bunkhouse at night instead of the cages. The two sick men in the regulation cages have tuberculosis. They have each been in bed a month; one has still ten months to serve, the other eleven. Both of these men have temperatures. No sleeping garments are provided them. They have on the regular convict stripes. The third man has running syphilitic sores on his legs. The tubercular patients have no receptacles to expectorate in, consequently they use the ground, the floor of their cage and anything that is convenient. There are no screens on the cages or in the kitchen to protect the food. Flies are swarming everywhere. The kitchen is only a short distance from the cage where the sick men are confined; and even nearer the cage than the kitchen is a block of wood on which meat is chopped up. When we visited the camp the meat was lying on this block of wood exposed to flies and dust. The filth of the bedding and the sleeping quarters of this camp is indescribable. The sick negroes were asked how frequently they got clean bed clothes. One negro replied that he had been in bed a month and no clean bedding had been given him. From the appearance of the bed I could well believe this to be true. When asked if he had anything to read he showed a Literary Digest that somebody had left at camp."

The sick prisoners referred to in this report were not adequately segregated from the other prisoners.

"The furnishings of the cages are the most meager and the worst I have seen anywhere. The bedding is simply a bundle of filthy rags."

THE ATTITUDE OF THE PUBLIC

"The most hopeless thing about the whole situation is that the public generally accepts such conditions as a matter of course."

Shortly after the report from which the last quotation above is taken was made, the grand jury in that county made the following report:

"We sent a committee of three to inspect the team camp of the convict force and found that the teams were in excellent condition, well sheltered and well cared for. (The men at this camp are not mentioned.) The grand jury visited the convict camp No. 1 and talked with the prisoners, and they said that they were well cared for and had no cause for complaint. The sanitary conditions surrounding the camp were good."

This is the camp in which the bedding is described above as "simply a bundle of filthy rags." Moreover, just before this visit was made two prisoners had been beaten, in violation of law, until their backs were blistered. If the grand jury was composed of men of ordinary intelligence, they knew about that beating. The probability is that they were good men, but that they had always been accustomed to regard brutality as a necessary part of prison routine and filth as inseparable from a prison camp. In this they are not different from the average group in the average county in the State.

Page 18

ALEXANDER AND VANCE POINT THE WAY

Two counties have shown that brutality is not necessary in prison discipline. Up against the Brushy Mountains, Alexander County, for a year or more, has been conducting an interesting experiment in prison discipline. She found herself with a small group of prisoners that she had difficulty in finding a place for in other counties, as had been her custom. It would be expensive for the county to run a chain-gang; but Mr. C. W. Mayberry, chairman of the board of county commissioners, decided that by establishing the proper personal contacts with the men he could work them without guards. He determined to try out his plan. Two men escaped soon after the camp was started. One was recaptured and sent to Rowan County. The other, an old man who was not able to work much, and could not be kept employed, has not been recaptured. Since then there has been no trouble. When seen a few months ago by a representative of the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare Mr. Mayberry expressed the opinion that 75 per cent of the prisoners of his county could be trusted to work without guards, provided he could have half an hour's talk with each before he went out. The results show that Mr. Mayberry was conservative in his estimate. A considerably larger percentage have made good.

When visited in October by two representatives of the State Board, the force now consisting of eight men had been loaned to the State Highway Commission, and was being used by their patrolman to improve a road in use as a detour. The regular superintendent was on a vacation. There were no guards. The patrolman in charge had no gun of any kind, as he stated in the hearing of all his prisoners. The men sleep in a camp at night, but they are not guarded, chained, or locked in. They wear no stripes or other uniform to distinguish them from other working men. They sometimes visit their families on Sunday. They report for work at seven o'clock on Monday morning. The man who has the best chance to escape, the cook, was considered a most difficult man before he was sent to the road. He had escaped once after arrest by throwing the deputy sheriff into a millpond, and had finally been marched into jail between two officers. "You are not going to send him to the camp," exclaimed incredulous citizens when he was sentenced to the road. Mr. Mayberry put the matter squarely up to the man. He has not betrayed the trust.

Vance County has not gone quite so far in some respects as Alexander, but in addition to having perhaps the best kept prison camp from a sanitary point of view in the State, she has gone far enough in the matter of discipline to make a distinct contribution to the prison history of the State. We let Mr. W. H. Johnson, superintendent of the camp, tell the story himself:

"1. All prisoners are required to take a full bath upon being admitted to camp, and given a clean outfit of clothes, consisting of underwear, shoes, socks, blue overalls and shirt.

Page 19

"2. We do not allow cursing or profane or indecent language, or degrading action of any kind. If this rule is broken, the offender is given bread and water for food. This punishment has been used only twice during the past two years.

"3. The same rule concerning profane or rough language applies also to all guards and overseers. If this rule is broken, it means the loss of their jobs. Guards and overseers are required to treat prisoners firmly but kindly at all times. The use of intoxicating drink is not allowed either on or off duty.

"4. We promise our prisoners very little, but always do what we promise.

"5. We allow prisoners all the privileges we can until they disobey. Then we put them under guard and keep them locked up when not on duty. When they are ready to do right, we always give them another chance. If they break faith a second time their privileges are not restored. Our six tractors and five machines are run entirely by trusted prisoners, with the exception of three hired men, who are not guards. The honor system is used as far as possible with all prisoners.

"6. An abundance of well cooked food is served three times a day in a well balanced diet. Vegetables of all kinds are grown at the camp and served every day. Dinner is cooked at the usual time and sent while hot to the prisoners wherever at work at noon. No waste is allowed; all scrap food is fed to the pigs, which supplies a large amount of meat used for the camp prisoners.

"7. The camp is provided with separate shower baths with hot and cold water, for colored and white inmates, and each prisoner is required to take a bath each week in winter and twice a week in summer, and given a clean suit of clothes each Saturday. Many of the prisoners use the bath daily.

"8. Separate sleeping quarters are provided for the races and separate food service also.

"9. No vermin of any kind is allowed in camp. Bed sheets and all clothes are laundered weekly. A separate hospital is provided so that any sick prisoner is at once removed from the others. Sick prisoners are attended by county health physician.

"10. Religious services are held every Sunday afternoon, conducted usually by the superintendent. These services are largely attended by families and friends of the prisoners. An effort is made at all times in the treatment of the prisoners to give them individual interest, to teach them a high standard of living and to return them as better citizens to the community."

"I would have Mr. Johnson add," writes Mrs. W. B. Waddill, county superintendent of public welfare, "that whipping of prisoners is not allowed."

Page 20

A SOCIAL STUDY OF JAIL POPULATION

If as a result of this present survey of the conditions that affect the care and treatment of prisoners throughout the State, all existing abuses should be remedied, and the physical standards should be so raised that we should have model jails and model prison camps--if such institutions can ever exist--our problem still would be only half solved. More fundamental than any improvement in physical equipment or standards of treatment is a study of the causes of crime. Emphasis in the past has been placed largely on methods of punishment, and great care has been taken to make the punishment proportionate to the crime committed. In the criminology of the future the major emphasis is going to be placed on the study of the criminal as a person. Already some progress has been made in studying the mental and physical equipment of offenders against the law, but almost nothing has been done toward studying the social equipment of the criminal. We still have far to go in exploring the social attitudes of the law-breaker, his status in the social groups to which he belongs, and in unraveling those subtle processes of human association and interaction by which one individual grows up into a social Ishmaelite, with his hand against every one and every one's hand against him, while another individual is socialized into a citizen, who is an integral part of the social group.

Whatever else may be the cause of crime, I am convinced it is not always due to moral turpitude on the part of the individual delinquent. People do not usually commit crimes deliberately through love of wrongdoing. While the individual factor is always present in crime, we have not yet estimated the part that is played in crime by inequalities of opportunity in our social and economic system. Economic pressure and lack of education and training are powerful incentives to crime. In the old days we confined our activities largely to punishing the criminal; in the future we shall direct our activities not only to educating the criminal for citizenship, but to a readjustment of our social and economic conditions that are conducive to crime. We have tried in the past to adjust human nature to our social order, with the result that crime increases with increase in civilization. I sometimes wonder what would be the result if we turned our attention a little more toward adjusting our social order to meet the demands of human nature--not the human nature of the rich and powerful only, but the human nature of all the people.

A criminal act cannot be rightly understood apart from the personality of the individual who commits the act. If we would understand a crime, therefore, we must know the person responsible for the crime. We must know the criminal in his relations to his family, in his relations to his business associates, and the community at large. We must know his hopes and ambitions, his prejudices, and the subtle workings of his mind. We can learn about him, not through accumulation of

Page 21

statistical data alone, but through a careful case study of a large number of offenders against the law. We must be able to get the point of view of the wrongdoer. Sometimes the criminal's explanation of his acts seems sound enough in principle to convince even a judge. Let me illustrate:

Several weeks ago I was talking with a prisoner confined in a jail in a rural county, serving a sentence for transporting whiskey. He was a farm tenant fifty-five years old with a wife and ten children, six of whom are dependent upon him for a living. He is barely able to support this large family, and a debt of only a few dollars is a formidable obstacle to overcome. Two winters ago his wife and several of the children were stricken down with influenza, and in order to tide them safely through this sickness he had to borrow about one hundred dollars from a relative. He expected to pay this debt back when he harvested his next crop. His crop was a failure, and the relative needed the borrowed money. The old man considered the payment of this debt a matter of honor, and in this sparsely settled rural county it seemed to him that the only way to make some ready money was to make blockade whiskey. He took his chance and was caught. While he is now a "trusty" prisoner in the jail his wife and children at home on the farm are running deeper still into debt. I wonder if the old man was not about right when he said he had never fooled with whiskey except when he had to.

Such cases as that recited above show that we need not so much a study of crimes as we need to know the social facts about the persons responsible for the crimes. During the month of October, 1922, a preliminary social study was made of one hundred and sixty-two prisoners found in a score of county jails in North Carolina. There are two weak points in the study which should prevent us from drawing any sweeping conclusions from it. The first objection is that the total number studied is too small, and the second objection is that the information was not verified except in case of the charges which were verified from the jailers' books. In only a few instances did we find that the prisoners gave false information as to the charges for which they were committed. In the other cases we took the word of the prisoner as correct without verification, since it was almost a hopeless task to verify all the information given by the prisoners with the limited time and means at our disposal. There are two reasons that lead us to think that the information given by the prisoners is at least as correct as that given by the United States Census--which is not verified--and that is the large number of prisoners who admitted they were guilty of the charge for which they were committed, and the number who admitted they had been in jail previously--both facts which would make against the prisoners at their trials and which we should expect them to try to conceal.

This preliminary study should be taken as suggestive, not conclusive. It has been offered solely in the hope that it might lead to a more

Page 22

exhaustive study of the criminal as a person, a more intensive survey of the social causes of crime, and a more sympathetic insight into all the conditioning factors, hereditary, environmental, and social, which produce, or make possible, any form of anti-social behavior. The social facts of county prisoners as given by themselves are listed below:

| No. | Per Ct. | |

| White, males | 86 | 53. |

| White, females | 8 | 4.9 |

| Negro, males | 63 | 38.8 |

| Negro, females | 5 | 3.3 |

| Under 20 years of age | 36 | 22.2 |

| From 20 to 29, inclusive | 73 | 45 |

| From 30 to 39, inclusive | 14 | 8.6 |

| From 40 to 49, inclusive | 20 | 12.3 |

| Fifty years or over | 19 | 11.9 |

| Married | 72 | 44.4 |

| Single | 72 | 44.4 |

| Separated | 9 | 5.5 |

| Widowed | 6 | 3.7 |

| Divorced | 2 | 1.2 |

| Unknown | 1 | .8 |

| Violation of the prohibition law | 39 | 24.1 |

| Sex crimes | 15 | 9.3 |

| Larceny, housebreaking, theft | 41 | 25.3 |

| Assault and fighting | 17 | 10.4 |

| Insane and idiotic | 14 | 8.6 |

| Murder | 9 | 5.6 |

| Forgery | 9 | 5.6 |

| Miscellaneous | 18 | 11.1 |

| Awaiting trial | 102 | 62.9 |

| Serving sentence | 33 | 20.3 |

| Tried, but awaiting sentence | 9 | 5.6 |

| Insane, usually awaiting hospital | 14 | 8.6 |

| Juvenile court cases | 4 | 2.6 |

An endeavor was made to get the viewpoint of the prisoner as to how he happened to get into trouble, the underlying cause of his criminal act. It is impossible to group these various reasons given, except as regards guilt or innocence, obtained from the prisoners' own statements.

| No. | Per Ct. | |

| Those claiming to be innocent | 67 | 41.3 |

| Those who admit guilt | 58 | 35.8 |

| Those giving no reason | 23 | 14.3 |

| Insane and idiotic | 14 | 8.6 |

Page 23

| Totally illiterate | 22 | 13.58 |

| Barely read and write | 42 | 25.92 |

| 64 | 39.50 |

| Second grade through fifth grade | 42 | 25.92 |

| Sixth grade or over | 42 | 25.92 |

| Insane or idiotic | 14 | 8.66 |

| Prisoners claiming venereal disease at present | 22 | 13.6 |

| Prisoners claiming former venereal infection | 13 | 8.0 |

| Prisoners in jail once before | 35 | 21.6 |

| Prisoners in jail twice before | 7 | 4.3 |

| Prisoners in jail over three times | 7 | 4.3 |

| Total number repeaters | 30.2 |

| Prisoners claiming relatives who were in jail | 37 | 22.8 |

| Prisoners claiming to belong to some club or secret society were | 25 | 15.4 |

| Farmers | 38 | 27.1 |

| Tenant farmers | 15 | 9.2 |

| Common laborers | 49 | 30.2 |

| Machinists | 8 | |

| No occupation | 8 | |

| Miscellaneous | 44 | |

| Total | 162 |

| No. | Per Ct. | |

| Prisoners claiming to belong to the church, not including the insane prisoners | 70 | 47.3 |

| Prisoners claiming to belong to church, including the insane prisoners | 75 | 48.7 |

NOTE.--Of the 14 insane or idiotic prisoners, 5 claimed church membership, 2 claimed they did not belong, while the church membership of 7 was not known. The unknown cases are not included in the total for the percentage of church membership.

| No. | Per Ct. | |

| Prisoners claiming never to have belonged to church, including the insane | 79 | 51.3 |

Page 24

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR PRISON LEGISLATION AS

FORMULATED BY THE COMMITTEE ON

POLICY AND PROGRAM

The first meeting of the Committee on Policy and Program of the Citizen's Committee of One Hundred on Prison Legislation was held in the office of the State Commissioner of Public Welfare in Raleigh on the afternoon of December 20, for the purpose of drawing up recommendations for prison legislation. The entire committee was present, as follows: Dr. J. F. Steiner, Mr. A. M. Scales, Dr. J. H. Pratt, Mrs. Kate Burr Johnson, and Mrs. T. W. Bickett. In addition to the committee, Mr. Roy M. Brown and Mr. W. B. Sanders were also present upon invitation.

The recommendations for prison legislation, as formulated by the Committee on Policy and Program, are as follows:

1. That at the session of the General Assembly for 1923 the secretary of the State Board of Health and the State Commissioner of Public Welfare be made ex officio members of the board of directors of the State Prison, thus increasing the membership of said board from five to seven, and that at the expiration of the term of the present board of directors of the State Prison, there shall be elected by the General Assembly, upon the recommendation of the Governor, five persons, who, with the two ex officio members mentioned above, shall constitute the board of directors of the State Prison. At the 1925 session of the General Assembly all five of these members shall be elected, two for a term of two years, two for a term of four years, and one for a term of six years; and thereafter the term shall be six years for all: Provided, that the minority party and that both sexes shall always be represented among the appointive members; elections to be by concurrent vote of the General Assembly.

2. That the State Prison be supported from State funds as other State institutions are supported, and that the proceeds from the State Prison and State Prison Farm be turned back into the State Treasury.

3. The abolition of the State Hospital for the Dangerous Insane, now located in the State Prison, under the direction of the board of directors of the State Prison, and the removal of all inmates now confined in said Hospital for the Dangerous Insane to other State Hospitals for the Insane, or to the Caswell Training School, after a careful examination of all inmates by a commission of mental experts.

4. The establishment on the State Prison Farm of a Colony for Tubercular Prisoners, sufficient to care for all tubercular prisoners, both State and county.

5. The establishment in the State Prison of an adequate system of prison industries, which would provide vocational training for such prisoners as are capable of receiving it, the products of such industries

Page 25

to be marketed at the discretion of the board of directors of the State Prison.

6. The establishment on the State Prison Farm of a Colony for Women Offenders, to which all women offenders under sentence shall be sent, except from such counties as have built Homes for Fallen Women in accordance with section 7344 of Consolidated Statutes; and except such as may be admitted to Samarcand.

7. That all prisoners sentenced for a longer term than 3 months by any court shall be sent to the State Prison, the necessary expenses of such transfer to be paid from State funds.

8. That section 7703, Consolidated Statutes, be amended to read as follows:

"The board of directors are authorized to employ such managers, wardens, physicians, psychiatrists, supervisors, overseers, and other servants or agents as they may deem necessary for the management of the affairs of the State's Prison, and for the examination, classification, health, safekeeping, and employment of the prisoners therein confined. They shall fix the compensation of such agents or servants, prescribe their duties by proper rules and regulations, and may discharge them at will."

9. Compulsory education for the prisoners in the State Prison, and the employment of teachers and instructors for same; said instruction to be during the regular work hours.

10. That section 7749 be so amended that the advisory board of parole shall be composed of the following: The State Commissioner of Public Welfare, the Superintendent of the State Prison, and the head of the Bureau of Parole of the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare, the last to be a full-time paid officer.

11. That flogging and confinement in inhuman dark cells and dungeons as a method of discipline for prisoners shall be prohibited in all prisons, chain-gangs, prison camps, or workhouses in the State. That the board of directors of the State Prison shall make rules and regulations for the discipline and care of State and county prisoners.

12. That the same standards of health and sanitation be maintained in city prisons as is required in county jails.

13. That the State Board of Charities and Public Welfare, in addition to its powers of investigating and supervising the whole system of charitable and penal institutions of the State, shall be given power to enforce the rules and regulations in regard to the care and treatment of county prisoners, and to maintain prescribed standards for county jails and convict camps. (C. S., 5006.)

14. That a matron shall be in charge of the women's wards of all county and city jails; in larger jails for full time, in smaller jails for part time.

15. Abolition of the convict lease system. (C. S., 7758-7763, 1356.)

Return to Menu Page for A Study of Prison Conditions in North Carolina by North Carolina State Board of Charities and Public Welfare

Return to The North Carolina Experience Home Page

Return to Documenting the American South Home Page