Obstacles to Medical Progress. Annual Address Delivered before

the Medical Society of the State of North Carolina, at Edenton, N.C., April, 1857:

Electronic Edition.

Satchwell, S. S. (Solomon Sampson), 1821-1892

Funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Melissa G. Meeks

Images scanned by

Melissa G. Meeks

Text encoded by

Melissa G. Meeks and Jill Kuhn Sexton

First edition, 2001

ca. 70K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) Obstacles to Medical Progress. Annual Address Delivered before the Medical Society of the State of North Carolina, at Edenton, N.C., April, 1857

S. S. Satchwell, M. D.

26 p.

Wilmington, N. C.

Fulton & Price, Steam Power Press Printers

1857

Published by Order of the Medical Society of the State of North Carolina

Call number Cp610.6 S25o c.2 (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 24th edition, 2001

Languages Used:

- English

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- Medicine -- Practice -- North Carolina.

- Physicians -- North Carolina.

- Medicine.

- Hydrotherapy.

- Homeopathy.

- Quacks and quackery.

- Medical education.

Revision History:

- 2001-12-11,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-08-29,

Jill Kuhn Sexton

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-08-03,

Melissa G. Meeks

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-08-02,

Melissa G. Meeks

finished scanning the text.

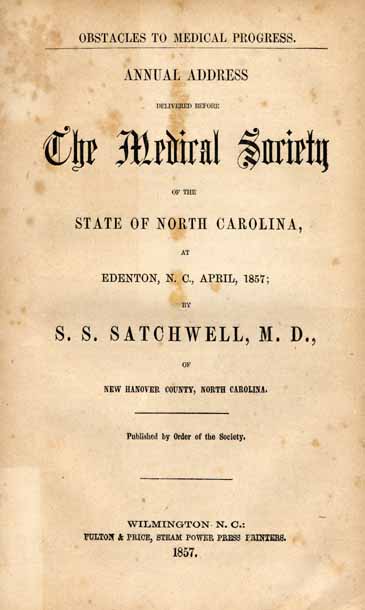

[Title Page Image]

OBSTACLES TO MEDICAL PROGRESS.

ANNUAL ADDRESS

DELIVERED BEFORE

The Medical Society

OF THE

STATE OF NORTH CAROLINA,

AT

EDENTON, N. C., APRIL, 1857;

BY

S. S. SATCHWELL, M. D.,

OF

NEW HANOVER COUNTY, NORTH CAROLINA,

Published by Order of the Society.

WILMINGTON, N. C.:

FULTON & PRICE, STEAM POWER PRESS PRINTERS

1857.

Page 3

ADDRESS.

Mr. President and Gentlemen

of the State Medical Society:

The revolution of another year brings to us the pleasing occasion for social communion and interchange of medical thought. We again meet as voluntary devotees at the altar of science and humanity. We have left for a brief period the anxieties and labors of practice, to mingle in one common brotherhood, mutual feelings of friendship and of professional devotion.

These fraternal gatherings are to the physician what the touch of his mother earth was to the fabled Antæus; they give him new vigor--arm him with new strength in his Herculean difficulties and warfare with disease. Wearied with the duties of an arduous profession, we make these annual pilgrimages with spirits that need the sustaining influences of an intelligent sympathy--such as our society always bestows upon her members. We return to our homes reanimated by recent contact with a body of wise, honorable and refined medical gentlemen; we are better pleased with ourselves, more attached to our profession, and better qualified to discharge its exacting duties. These meetings make us better acquainted, transform formal acquaintances into genial friends, and materially serve to substitute harmony and concert of action among medical gentlemen, in place of that isolation and separation which is so apt to engender feelings that have been too long a reproach to the medical profession.

If aught of a striking or original character is expected of my humble effort on this occasion, I can only assure you that to my own embarrassment will be added your disappointment.

I make no pretensions to literary or professional excellence such as the appointment of your annual speaker presupposes. I feel that the honor your kind partiality has bestowed upon me, results more from a desire to compliment my humble zeal in favor of medical improvement in North Carolina, than from any personal merits or supposed qualifications of my own.--

Page 4

Unaccustomed to public speaking, my time absorbed by the exhausting duties of a laborious country practice, surrounded by none of those circumstances necessary to

The science of medicine is based upon the accumulating light and knowledge of nearly thirty centuries. It has established principles. They rest upon facts and deductions, gathered within this period from the rich fields of observation, experience and experiment, by hosts of men of the most astute intellects, profound learning and exalted moral worth. The science is composed of materials collected from every age and every clinic. No alleged fact has been permanently admitted unless established by truth, for truth alone receives its undivided homage. Each truth has been assigned its relative value, after due investigation and appreciation by the profession. Medical science has ever been comprehensive and liberal in its nature. It is influenced by no predilections nor animosities. It has always availed itself of every circumstance, however humble its origin, that has been, or is, in the least calculated to throw light upon disease, and resorts to every available remedy for its cure, and for mitigating the sorrows and sufferings of mankind. It heeds no authority unless sustained by truth and rejects error, however high and imposing its source. This is seen in the once popular but false and now exploded theories of Stahl, Booerhave, Hoffman, Cullen, Brown, Darwin, Coolie, Push and Broussais. Their doctrines are mostly obsolete whilst the important hints and suggestions they afford, are cherished as of decided value to the practitioner in the discharge of his arduous duties.

This is the spirit of our profession, and this the manner in which its science progresses. And in the present times so teeming with discoveries and experiments, every one, as it presents itself in our profession, is subjected to the same rigid ordeal of our inductive system of medical philosophy, through which its predecessors have passed before receiving the stamp of accepted science.

With claims thus imposing, resting not alone on venerable antiquity and enlarged views, hallowed by the wisest and best men of all ages and countries, but upon its established power to do vast good to mankind, it is a matter of regret that so much of the former glory of the profession has departed. Instead of the mutual support and noble aspirations and competitions which obtained among medical men in former

Page 5

days, we see too many ignominious means used to supplant each other, and to succeed in the present times, and to make money by prostituting medical art to a mere trade. In the Grecian age, medical practice was hedged in, as it were, by a divinity. A temple was erected at Ephesus to the Goddess Hygeia. But how differently is the profession estimated at the present day! That medicine, as a science, is progressive, none can deny; that its progress is much impeded is equally true. That the profession itself receives acknowledgment of its worth is unquestioned; but I fear its standing has been lowered. The reasons of this depreciation involve the consideration of questions suitable, as I conceive, to the present times. The main subject, then, of this address is the discussion of some of the causes which retard medical progress. I consider this proper from the nature and objects of our Association. It seeks to renovate the profession. The correct starting point to this is the reformation of errors and the correction of abuses. These circumstances are connected with causes within and without the profession. Some of them are to be located at our own doors, and others will be charged to the fault of the public.

An obstacle to the progress of medical science is the false issues that have been made between the regular profession and the pseudo-medical systems of the day under the names of Homoeopathy, Hydropathy, Eclecticism, Thomsonianism, fragments; they are nothing more nor less than mere fractions of the more enlarged and system of legitimate medicine. We have done true medical science injustice in allowing these false issues to be made. And if we would indulge less in invectives towards the practitioners of these fragmentary systems, and bestow more time and attention in enlightening the public as to their true character and relations to regular medicine, we should be more successful in exposing the distortions and misrepresentations to which they resort, in imposing, with more cunning than honesty, upon deceived and misguided communities. Each of these apparently new medical systems is but a fraction of the regular and really Electic School.

Page 6

Take that of Homoeopathy. Its great central doctrine,

It is well known that minute doses of many of the most powerful vegetable narcotics and mineral poisons are the most efficient means in curing many chronic diseases; and it is equally true that Homoeopathy seizes upon them with avidity, and claims them exclusively as its own.

In chronic diseases, constituting by far the greatest amount of practice, it is often necessary to prepare the system for the action of these minute doses of powerful medicines, and this the restricted range of Homoeopathy renders it unable to do.

Akin to these presumptuous claims of an exclusive practice, is that medical system known at different times under the changing names of Thompsonianism, Steam Doctoring, Vegetable Practice, Electicism, and Botanico-Eclecticism.

In our own State the practitioners of Thomsonianism have steamed nearly all vitality out of its system, and over its prostrate remains has arisen, by the transformation of nature, the more refined and captivating name of Electics, and Botanico-Electics They may all be placed nearly in the same category. They are mostly confined to broken-down pedagogues, itinerant quacks, deluded young men, and designing men in the regular ranks, who, sacrificing principle to expediency, are ready to avail themselves of any delusion, in order to make money, even at the sacrifice of science and humanity. They are ignorant of the science of Botany; and not one in fifty of them can tell the distinctions between the systems of Linnæus

Page 7

and Jusseau. With some confused notions of disease, they adopt the erroneous views of the human economy, that life is heat and that cold is death. Without any accuracy of disinclination in the signs of disease and the selection of remedies, they use a number of stimulating vegetables, under all circumstances, and often with the most injurious results. In the. whole list of their remedies, however, they employ none of any value, which they have not ungratefully taken from our own recognized materia medica and perverted to their own ignorant and ignoble purpose.

Hydropathy has succeeded to no inconsiderable extent, in palming the delusion upon the public, that it, too, is a system of practice entirely different from the regular school--that it possesses, in the power of cold water, a panacea for all the ills of mortal nature, and that it alone is entitled to the baptismal rites of its use. Water has ever been a legitimate remedy in the profession. Its use in all modes and forms, and in all temperatures, is an integral part of regular medical practice. But its employment requires the exercise of caution and judgment, resulting alone from experience, varied and extensive medical knowledge, and tact in its administration. In many portions of our country, Hydropathy has erected its hydropathology establishments for the treatment of chronic diseases, mostly by means of cold water. They are generally found in healthy and pleasant places.

he had nothing to testify in relation to his own personal experience in the use of them, as he had neither And so it is with the benefits received at these hydropathic institutions, as well as at most of the noted springs of our country. It is not so much from the use of water, internal or external, that health is improved by visiting such places, as it is by a practical application of the principle of treatment to which I have referred. I am aware, that there are special diseases which are relieved by using the water of certain springs this is admitted by every physician. And while I would not discourage the annual custom of visiting springs and watering places, I would also enforce the truth, that the observance, on such occasions, of hygienic rules and regulations, and not the use of water, constitutes the main instrumentality of good. And, in this connection, I would say to our people who are so fond of going abroad every summer for health, and in this way spending hundreds of thousands annually in enriching other States, that North Carolina has claims upon your State pride and money, while she presents to her fair daughters and sons elysiums of health and pleasure among the delightful sea breezes of her Eastern shore;--earthly paradises among the fragrant hills, flowery vales, gushing water-falls and magnificent scenery of her Western counties. Here, in old North Carolina, you have mineral waters, as well as mineral wealth, fine venison, scuppernong wine, pure mountain air, lovely scenery, and good society--all equal to the like productions of any State, and capable of yielding as good health, if you will remain it home and enjoy them, as you can find anywhere. In regard to the medical systems to which I have alluded, I rejoice that neither these nor any other new-fangled medical doctrines have obtained much of a foothold in North Carolina. They are not indigenous here;--our soil is not suitable to these foreign growths. In our own country they are confined mostly to the North, which is fast becoming a great laboratory for the manufacture of medical as well as political and religious heresies. Those who adhere, in our own State, to such medical delusions, consist, in the main of men and women from the North who have taken up their residence among us.--They are almost the sole patrons of Homoeopathy and Hydropathy. They come to the South with their minds poisoned on medical subjects, and they seek to communicate this poison to our Southern people. Diligent efforts are being made to indoctrinate our people with the unfounded claims of these medical systems,--which it would be mere mockery to designate

by the name of science,--and I have thought it proper to make these few general remarks in reference to them. An exposition by our professional brethren, on suitable occasions, of their mystifications and true relations to medical science proper, will materially enhance its just claims upon public confidence. It is time for intelligent men to entertain a more correct estimate of the medical impositions of the times, and of the fallacious reasoning used to sustain them; it is well for them to remember that medical men are now, and have ever been ready, as read as the votaries of any other science, to welcome any new discovery or invention appertaining to medicine; it is time for the intelligent and influential in the community to wake up to the importance of the fact, that any encouragement, however slight or momentary which they give to the quackery and delusions of the day, is a blow, more or less severe, at regular medical science, and regular practitioners. The real issue is clear and distinct. Every man's influence is thrown into one scale or the other. He who patronizes to-day any new-fangled doctrine or radicalism in medicine, by that act enrolls himself as a patron of the whole system of medical imposture. No new doctrine or remedy should be received until after rigid scrutiny, and a test of careful and extended observation. The sophistries which have become prevalent on this point, both within and without the profession, are a fruitful source of the delusion and quackery in the world. The imperfect preliminary education of practitioners is another obstacle to the progress of medicine. Here I am aware I am on ground familiar to those who are acquainted with the transactions of the American Medical Association. But the subject is worthy the consideration of State medical bodies, as well as our higher national organization and its general importance commends it to the attention of all. Medicine is an elaborate science; or rather it is the science of sciences. It is based on all the natural sciences. Chemistry, botany, physical and mental science, geology and mineralogy, are all laid under contributions by medical science.--Some of the finest illustrations of principles of natural philosophy are seen in the human body. It is well known that to acquire a knowledge of these natural sciences, requires mental culture, logical acumen, capacity to think and to investigate. The mind must be well trained before it can grasp them. And yet, young men plunge into medical science, the most subtle, comprehensive, and complicated of all the sciences, not only without this mental discipline, not only without a knowledge of these natural sciences, but unable to read the Latin of their diplomas, or to write and speak their mother tongue correctly.

Among regularly licensed practitioners, how many are there who know the botany of medicinal plants--those beneficent productions of nature to relieve the ills of life; how many understand the acoustic principles of the I need not say, that tortuous and rugged is the way that leads to a knowledge of medicine. He who would revel in the rich luxuries that lie waiting within her golden temple, must expect to do so, not by the arts of legerdemain, or the tricks of demagogueism, but by long, laborious, mental application,--ardent love of truth--skillful interpretation of the laws of nature, is the price he must pay. The ever-varying phenomena of life, in health and disease, the wide domain and diversified character of remedial agencies, the sound judgment and active sympathies necessary to constitute a successful practice of our heaven-born science, demand a cultivation of the head and heart. The intellect as well as the moral nature and affections must be educated. That these requirements are not observed; that this is not the way doctors are made; that educational deficiencies are a great cause of the overflowing numbers in the profession, in opposition to that maxim of political economy, that the supply should not exceed the demand, are truths, I regret to say, too obvious to be denied. But it is said that all successful and eminent physicians are not thus educated. This is true; but such men are nevertheless educated. They may never have been in an academy, or in a college, but they have been trained in the rigid school of poverty and self-dependence, which may have given them a discipline, a power of thought, and a knowledge of human nature and the world at large, not always to be obtained at universities. They are men of iron will and inflexible determination, which nothing can resist; and the very hardships which they undergo, and the struggles they make to supply early and conscious deficiencies, call into requisition habits of self-reliance and mental effort, constituting an education in the broad sense of the term. There are comparatively few possessed of this indomitable energy; and this fact is the best evidence of the correctness of my position. The cause of this imperfect preliminary education is referrible,

in a great degree, to the medical colleges. The requirements for admission into, and graduation at, nearly all of the thirty odd medical schools of the country, are not only low and imperfect, but mostly nominal, at that. A young man may leave the plough, workshop, or merchant's counter, enter a physician's office for a year or so, attend two courses of medical lectures, and graduate as a peer of the most skillful and thoroughly educated physician in the land. No preparatory education, or even preliminary medical reading is required. The great desideratum with the medical colleges is for him to pay for his tickets for two sessions. The matter of his attendance on the college exercises, and his moral character for honor, truth, and rectitude, weigh but little in the scale of estimate. Thus it is, that swarms of doctors issue annually from the medical schools. They commence practice, most of them ignorant of their profession; and to that extent are really entitled to commiseration. Inflated with the pride and vanity of a diploma and deluded with false hopes of success, the young graduate settles in some town or village, and unfurls his banner to the breeze. Cases soon present themselves, some of them difficult to manage; he has never seen any like them before. His books, for the first time, are at fault. His position is now different from sitting in the lecture rooms of his

Page 8drank of them, nor bathed in them."

Page 9

Page 10

Page 11alma mater, listening to lectures on health, and disease, and remedies. Defeat and mortification meet him on all sides. A gathering storm destroys the flattering hopes of his bright medical fancy. He begins to lose confidence in himself; he begins to find that he has not science to sustain him. He blunders along in the dark. Disappointment follows disappointment. He finds himself casting about upon the stormy sea of uncertainty, with no safe guides to keep his frail bark from perishing. He sees no means of securing a fair name, and of earning an honest living. The consequence is, that he is either obliged to commence anew some other more suitable occupation, or resort to every species of empiricism to get a living. A large majority of the quacks of the land are graduates of what are called regular medical colleges. Rushing into these colleges without adequate preparation, spending their time and money at them to little advantage, unwilling to make up for early insufficiencies by protracted mental labor and self-denial, they find that they have reckoned without their hosts;--that they have mistaken their calling;--that they are mere cyphers in the most difficult and laborious of professions. Such men are to be pitied. Those who have been mainly instrumental in placing them in this unfortunate condition, who have, with great eclat, crowned them with the highest

Page 12

honors of a medical college,--are the very first to neglect them, and to sneer at them in their pitiable condition. Such young men, while too late in discovering their error, in their hearts censure their alma mater for their misfortunes. They know, as we all know, that it is "the ambitious struggles of competition--the love of fame, money and numbers" that causes these institutions to disregard the claims of humanity and science, in the motives which actuate them in these matters.

But the colleges reply that they operate on the imperfect materials furnished them by the profession; that it is with the profession the reform must commence. This plea of theirs is not a sufficient excuse for the error of graduating young men as they do. They could and should place themselves on high and elevated grounds in this important matter; and the profession would then rise to a corresponding level. Nevertheless, a wrong is often committed by physicians, in taking incompetent men into their offices to study medicine. It seems to me, that many of us commit an error in recommending young men to engage in the profession, without this preparation of which I have spoken. Let physicians maintain a firm and elevated position in this respect; let them, on all occasions, dissuade young men from engaging in the practice of medicine, on their own responsibility, until they have become well grounded in its principles, and have seen and studied for themselves, thoroughly, the varied phenomena of disease, and its treatment; and we shall thus discharge a duty we owe to them, to ourselves, to our profession, and to the community.

Another circumstance militating against the progress of medical science is the want of protection to the profession by legal statute. Any one who chooses, can now practice medicine and surgery, and thereby misrepresent the profession and bring discredit upon it. It is said that medicine ought to protect itself; but this is at variance with the doctrines of political economy that have been recognized in state and national legislation, ever since the science of political economy had an existence. And such is the nature of medical science, that the world at large finds it difficult to discriminate between it and empiricism. A large portion, learned as well as unlearned, often find it difficult to make a correct estimate of the qualifications of professional men. Perhaps in no profession are there so many successful means of deluding and imposing upon mankind as there are in the medical. Hence it is, that medical science and the public safety, present imposing claims upon legislators, to institute such laws as are most likely to meet these claims. The moral force of associated medical effort has done much, and is destined to do a vast deal

Page 13

more, for the profession and the public good; but it is important and right to add legal suasion, to aid in suppressing the medical delusions and

I am aware that a small but respectable number of practitioners are opposed to the establishment of these medical boards; but in the main, they are either those who have some direct personal interest in a medical college, or those laggards in the profession who are unwilling to measure their

I regret that in this matter our own Legislature has exhibited such determined resistance to the pleadings of humanity and science. A bill aiming at the appointment, on proper principles, of a medical board, was rejected at the last session. For several Sessions past, the Legislature has refused to legislate on the subject. The national government will not allow any one to practice medicine and surgery in the army and navy without an endorsement of qualifications by a competent medical tribunal. The State will not allow any one to plead your cause in a court of justice without authority from the Supreme Court. She will not allow her free school teachers to teach your children without permission from boards of examiners. And yet, so cheap is her estimate of human life, that she opens the doors wide, to any and all who will; to traffic in the health and lives of her citizens.

I am informed by a physician, that there were some twelve or fifteen physicians who occupied seats with him in the House of Commons of the last Legislature. That very few of them were in favor of any project for a medical board; and when the decisive vote was taken on the medical bill; only three or four of them voted for it. Several legal gentlemen not only voted for, but ably advocated, its passage, and for one, I return them, on this occasion, my thanks for this independent advocacy of the best interests of the Commonwealth.

The Journals of the last Legislature will show, when published, the proceedings and votes on this bill. Not one physician, so far as I can learn, was heard to raise his voice in

Page 14

the last Legislature in behalf of the rights of his profession, and of the public good, in this relation. So far from this, is not the conclusion inevitable, that the course which these physicians pursued towards this medical bill caused its defeat?--Why did so many of them endeavor to raise a panic among the members, that the bill was unpopular with the people--that if they passed such a bill it would be the death knell of their political hopes for the future? It would not have been legislating for the medical profession, any more than for the welfare and safety of their constituency, for the members of the Legislature to have passed this just and reasonable bill.--The true statesman will breast the storm of popular clamor, in order to do good service to his State, and is willing to work on and wait for time to vindicate the correctness of his course; but the political tradesman chooses to float smoothly along upon the bosom of the popular current, even if he knows it to be freighted with destruction to the best interests of the people. The fate of this bill is additional evidence of the fact, that medical science need not look to the tricky domain of political life, or among those who work the wires that control legislative action, for her most reliable friends.

But I do not despair. Rather am I disposed to appeal from the decision of the Legislature, to the virtue and intelligence of the people, and to utter my belief that those who opposed this bill from selfish motives of popularity, have mistaken public sentiment. At any rate, when the subject is more generally and correctly understood, the voice of the people will demand that the Legislature shall no longer continue to place scientific practitioners on an equality with the ignorant and prowling quacks of the land. I need not enlarge on the subject of a medical board. It was well presented in the eloquent address delivered before the society last year by Dr. Edward Warren of this town. If those legislators who have heretofore opposed, in this way, the claims of humanity and science, should continue their opposition, then may others, influenced by better counsels and more comprehensive liberality, be elevated to the positions heretofore occupied by the time-serving and narrow-minded.

Evil, wide spread evil, is the result of this want of legal recognition of the claims of medical science, and of this ease of access to the profession. It diminishes public respect for the profession as a body; and tends to discourage the talented and educated young men of the country from engaging in a calling where diplomatic ignorance is placed on an equality with modest merit and knowledge. It encumbers our ranks with mere drones--with routine practitioners--with men who

Page 15

are too indolent to read, too obstinate to learn. It encourages that spirit of professional demagogueism, which, I regret to have to acknowledge, seems on the increase in the profession. Men who have too little learning and intellect to succeed in other pursuits, often obtain success in medicine, by the mere authority of a diploma. They frequently use the most unworthy means to obtain practice and gain popularity. Unstained by science, they strive to make up the deficiency by seizing upon that inability of a great many to distinguish rational medicine from blustering empiricism. They hide their ignorance in mystic clouds of their own creation; deceive by the narration of marvellous cures never performed, heroic achievements never accomplished; and relate them with unblushing impudence in public as well as in private--at the domestic fireside as well as at the corners of streets, and market places, and country church-yards. There are always dupes enough to believe them; for it is strange that testimony which the common sense of mankind rejects, when appertaining to all other subjects, receives credence in matters of medicine. Such men practice medicine altogether as a trade. They constitute the main portion of those medical demagogues, who without merit or knowledge to sustain them, succeed by obsequious manners, and sycophancy to the wealthy and influential around them. They have their "runners" or "strikers" to aid them in blowing their own trumpets, or in insidious efforts to injure some rival practitioner. They will meet an honorable competitor with a smiling countenance and warm greeting, and perhaps whisper in his ear flattery and professions of friendship. The next day they will be relating "in confidence," to a select circle, some "lie" affecting his moral or professional character. Bring them to an accountability, and they will manage, like the eel, to slip out of it, saving their bodies from harm, but leaving their offensive slime behind. The cowardly assassin, who, in the hour of midnight, thrusts his stiletto in the heart of his unsuspecting victim, is not more mean and murderous in intention than these men, who, with deceitful and treacherous hearts, base innuendoes and a hypocritical shrugging up of the shoulders, would advance themselves by injuring the personal or professional character of some worthy, and high-minded rival,--it may be some poor and deserving young physician, just starting out in life. If there be any class of demagogues who deserve to be stretched high upon the gallows of public condemnation, such medical malefactors are the men. I fear there are many of them in North Carolina, with nicely framed diplomas hanging up in their offices. They are loud in professions of regular practice,

Page 16

and in a strict observance of ethical rules; but "by their works ye shall know them." They are generally found to be members of that political party and of that religious sect which has the most influence in their respective places of practice. By such a course of hypocritical cant and fawning upon power and wealth--flattery of old maids and young maids--sly and underhanded attacks upon those supposed to be in their way, such men make money, and often fortunes, while, perhaps, penury and want is the lot of some rival vastly their superior in all respects, but who scorns such a sacrifice of principle and honor, and who despises such contemptible means of obtaining practice. Under the name of regular practice, some of the most despicable empiricism in the land is practiced upon the public. We talk about the outside impositions of charlatans; but the profession has more to apprehend from the empiricism of some of its own recognized regulars, than from any other class of medical impostors. We talk about the evils to the public, of patent medicines; but they are not surpassed by the

Is it not the duty of every honorable medical gentleman to array himself against all such empiricism and demagogueism, so withering in its influences upon all that is beautiful and noble in the profession? It should be branded wherever it is seen. To resist such influences the more effectually, there must be union among those who are really entitled to be called medical gentlemen. The "good men and true" in the profession must themselves be united and harmonious. Nothing is more deplorable in the profession, than to see such men disunited or at war one with another. It ought to be printed in letters of gold on every diploma, that honor, truth, justice and concord is the spirit of medical science; and under this should follow the inscription, that he who degrades an honorable rival, degrades himself and his profession.

Before leaving this topic of medical wrongs, I deem it in place to make an allusion to the neglect shown to medical science, in the increasing disposition of practitioners to become absorbed in the distractions of politics. The excitements and corruptions of political life are at variance with the gentle, benevolent, elevating tendencies of legitimate medical pursuits. He who practices medicine and surgery has need to keep his head cool, and his feelings tranquil and liberal. The practitioner who launches his bark upon the stormy sea of

Page 17

party politics, necessarily surrenders, in a great measure, that professional devotion and serenity, so necessary to the physician. The independent right of suffrage none will deny; the duty of every patriot to inform himself of the history of his country, of the nature of government, and of the political progress of the times, is everywhere admitted; but this does not imply that it is proper for every practitioner to plunge himself, mind, soul and body, into every political campaign that annually arises to inflame the passions and prejudices of the multitude. The physician who becomes a heated actor upon the dirty arena of political life, is unfitting himself for the needed composure of the sick room, and for the responsibilities of his profession. The science and benevolence of the profession is not homogeneous with the tumults, selfish movements, and ambitious schemes of politicians. Medicine wins her triumphs in a different manner, and upon a different theatre. She secures them, not alone in correct interpretations of nature, abstractions of reason, and wise adaptation of remedies, but in the genial temper of charity and kindness, which should mark the ministrations of her votaries at the bedside. The physician should not only have the knowledge and skill to know and to prescribe, but the feeling heart that prompts the soothing hand and the tender words. His heart should beat in sympathetic unison with the efforts of his intellect. There should be mutual confidence and regard between him and his patient. It renders the treatment more effectual. The patient may have confidence in his physician's skill,--

"But simple kindness, kneeling by the bed,

To shift the pillow for the sick man's head,

Give the fresh draught to cool the lips that burn,

Fan the hot brow, the weary frame to turn

Kindness, untutored by our grave M. D.'s,

But nature's graduate whom she schools to please,

Wins back more sufferers with her voice and smile

Than all the trumpery in the druggist's pile.

And last, not least, in each perplexing case,

Learn the sweet magic of a cheerful face,

Not always smiling, but at least serene,

When grief and anguish cloud the anxious scene

Each look, each movement, every word and tone,

Should tell your patient you are all his own

Not the mere artist, purchased to attend,

But the warm, ready, self-forgetting friend,

Whose genial visit in itself combines

The best of cordials, tonics, anodynes."

The defects and errors to which I have alluded, are not the only obstacles to medical progress. In spite of these opposing

Page 18

circumstances, the march of medical science is onward; hosts of able and true-hearted explorers and practitioners are daily enlarging its boundaries, and giving to it more certainty and usefulness. This day, the medical profession, as a body, presents more imposing claims upon public confidence than at any former period. This confidence is inadequately bestowed. There is too much depreciation of medical science proper, and of the medical profession as a body; and herein consists the discouragements to the honest and competent practitioner, to which I shall now allude.

One of these discouragements is the disposition in the public to reject true medical practice, in the eager desire to swallow patent medicines, and to adopt new-fangled medical practice. Thousands upon thousands, in our own State, are daily denouncing medical science, and at the same time administering to themselves and families the most powerful remedies in the shape of nostrums. They refuse the "mineral medicines," as they call them, of regular physicians, but are ready to follow the prescriptions of corrosive sublimate and arsenic, of itinerant wart and cancer doctors. They "have no confidence in medicine," as they often say, and yet are the best patrons of nostrum venders. A neighbor of mine, who is an honest, clever man, but noted for his want of confidence in physicians, recently paid a traveling quack one hundred dollars for a vial of drops, and the application of some mysterious mesmeric passes to one of his children, for the cure of epilepsy. The quack continued on his journey; the patient is not relieved; and the deluded father is left to lament his folly.

A distinguished writer in the Dublin University Magazine remarks as follows:--

"Admitted to the fullest confidence of the world, yet, by a strange perversion, while medical men are the depositories of secrets that hold together the whole fabric of society, our influence is neither fully recognized, nor our power acknowledged. While ministering to the body, we are enabled to explore the mind, and, by watching the secret workings of human passion, can trace the progress of mankind in virtue and vice; and yet, scarcely is the hour of danger passed, scarcely is the shadow of fear dissipated, when we fall back to our humble position in life, bearing with us but little gratitude, and, strange to say, no fear! The world expects the physician to be learned, well-bred, kind and attentive, patient to their querulousness, and enduring under their caprice; and after all this the preposterous absurdities, the charlatanisms of the day, especially if they are of foreign. extract, will find more

Page 19

favor in their sight than the highest order of ability, accompanied by great natural advantages. Who has not seen, over and over again, physicians of the first eminence put aside, that the nostrum of some ignorant pretender, or the suggestive twaddling old woman, should be tried, as it is termed. No one is too stupid, no one too old, no one too ignorant, too obstinate or too silly, not to be superior to Brodie and Chambers, Crampton. and Marsh; and where science with anxious eye, and cautious hand, would scarcely venture to interfere, heroic ignorance would dash boldly forward and cut the gordian difficulty by snapping the thread of life."

"Fools rush in where angels fear to tread."

Perhaps no feature of this want of proper appreciation of medical science is more mortifying to the practitioner than the general reluctance manifested in the payment of his fees. Here is a profession, which, in antiquity, learning and benevolence, yields pre-eminence to none--a profession distinguished above all others for its disregard of danger, in its laborious duties by day, and its ceaseless vigilance by night, in ministering to the relief of suffering humanity; and yet, when the physician presents his bill , reasonable and just, for settlement, it is, as a general rule, paid with reluctance, and sometimes by the force of the law. It is remarkable that a man will willingly pay his lawyer a hundred dollars to secure his property, but most unwillingly pays his physician half that amount for saving his life. It is, indeed, a wonderful peculiarity of the world, that men will run almost any risk for money--will sacrifice comfort, health and happiness, to almost any extent, to secure it; and to have health, on which so much depends, restored, and themselves snatched from the brink of the grave, under providential favor, by our divine art, they are, in a large majority of cases, indisposed to make just recompense to their restorer. There is no profession so laborious and self-sacrificing as ours, and none so poorly rewarded. It is well known that physicians, obliged to rely upon their practice for a living, are generally poor; and it is equally true, that the main cause of this is, that patients, not when languishing on beds of sickness, but after their restoration to health, become wonderfully oblivious of their duty to pay them their just reward.

The physician who has spent his means, and years of study amid trials and dangers, to qualify himself, and whose delight it is to give his time, attention and talents, to the study and practice of his calling, has a right to claim that society shall keep him from the anxieties and depressions of pecuniary

Page 20

want, by a fair remuneration of his services. If he be depressed by pecuniary want, he is unable to give that devotion to his professional duties which a liberal appreciation of his labors will always enable him to give.

Physicians who love their profession are generally poor collectors; as a class, they are proverbial for bad financiering; they are too much disposed to yield to the disposition of the public to pay every one else before the doctor; the mechanic, the merchant, the lawyer, all, must be paid before the doctor; he comes in last, when he should be the first to be paid.

It is high time that the tone of public sentiment in relation to this subject had improved. I am contending not for exorbitant or unjust fees, but for a fair, reasonable, prompt, willing remuneration to physicians for professional services. That is all we should desire, or do desire; nothing more--nothing less.

Some physicians allow patients to pay them what they (the patients) please, and when they please, from an idea that a different course will injure their practice and popularity; but this is a very erroneous notion, and, when analyzed will be found to convey, not a compliment, but rather a reflection upon the personal worth and skill of the physician. No man, it seems to me, should employ a physician unless he has confidence in his character as a gentleman, and his skill as a practitioner; and then he should be willing to reward him properly for his services. Physicians should regard it as an object of more importance to be firm and united in charging, and not only in charging, but in collecting reasonable fees from those who are able to pay; reserving their gratuitous services for the poor alone. We owe this to ourselves, to those who may come after us, and to the truth, dignity and usefulness of the profession. And whenever we see a physician endeavoring to advance his popularity and increase his practice, by purposely adopting a system of prices, that aims at undercharging the regular and the reasonable fees of some rival practitioner, it should be regarded as an evidence of incompetency, and of a disposition to succeed by means so disreputable as to deserve the condemnation of all good men.

In 1853 the city of New Orleans instituted a commission of six medical gentlemen to engage in sanitary labors, and to make such recommendations as would be most likely to conduce to the health of the citizens, and to ward off epidemics of yellow fever that have so sadly devastated that city in the past. They all entered heartily upon their labors--neglecting their practice--braving every danger, and making great and protracted labors and sacrifices of time, thought and money,

Page 21

in order to do good to the health of the city. Their labors have been productive of incalculable advantage to New Orleans, whose authorities employed them; and the voluminous report of the chairman, Dr. E. H. Barton, is a rich addition to the science and medical literature of the country. For their services they charged the very reasonable and modest sum of fifteen thousand dollars. And yet, up to a recent period, the rich city of New Orleans has allowed these gentlemen to remain unpaid; year after year her authorities have refused or neglected to pay them; so that, after waiting so long in vain endeavors to obtain this well-earned amount, they have resorted to a court of justice to recover what is so justly due them. In the language of another physician:--"It is high time that the public services of our profession should be suitably estimated--since those in private life are too generally undervalued. Legal advice, often given with infinitely less amount of mental and physical labor, is at once fully and fairly remunerated--as, indeed, it should be. Are the services of the physician of less value in preserving public health, than the counsellor's, in maintaining public rights, or preserving public property? We trust that the issue of the pending suit will establish a precedent which, though it point to a blot on the Southern City's escutcheon, will be a guide in all future similar emergencies, and assure to professional labors a proper estimate and a just remuneration."

Additional evidence of this in appreciation of scientific practitioners, is the under-estimate placed upon their gratuitous services to the poor. It is the glory of the profession that it dispenses its blessings alike to the rich and the poor--the learned and the unlearned--the just and the unjust. In its dispensations it recognizes no distinctions of class, sect, party, race or clime. Wherever there is pain, or disease, or distress, there the physician finds a legitimate theatre for the exercise of his skill and benevolence. His familiarity with suffering and death begets a philanthropic zeal, a glowing enthusiasm, to relieve sickness wherever he finds it. The charge sometimes made, that this familiarity with suffering and distress hardens the heart of the physician, is a slander upon the profession.--The reverse is true. It refines the sensibilities, softens the heart, and makes the medical man more charitable to the frailties of humanity. Hence, it has always been a custom with the profession to attend the poor gratis. The physician is under no obligation, really, to do it, any more than the farmer is to give away his corn, or the merchant his coffee. It is from charity, and charity alone, that he gives his time, medicine and attendance. A large portion of the community act upon

Page 22

the assumption that the physician is bound, morally and legally compelled, to make such contributions. Who in this way contributes so much in dollars and cents to the community as the physician? I venture the remark, that in proportion to its pecuniary means, the medical profession contributes more to the relief of suffering and distress than all the other professions and occupations combined. An estimate has been recently made by Dr. C. H. Spillman, President of the Kentucky State Medical Society, of the amount contributed in this way by the physicians of Kentucky. The result of the investigation is, that each practitioner of that State, gives three hundred dollars annually to the community, in his services to the sick poor. Surely North Carolina is not behind any State in the benevolence of her medical men; and according to this estimate, the medical profession of our State contributes every year the sum of forty thousand dollars, at least, in relieving sickness and distress. Society does not expect, nor, as a general thing, receive, such contributions of benevolence from the lawyer, the mechanic, the merchant or the farmer; but it seems to demand them as a right from the physician.

But notwithstanding these discouragements to the physician and the numerous impediments to medical progress, the science of medicine is continually progressive, and is more able than ever to relieve pain and disease. The range of usefulness of the physician is becoming more and more varied and extensive. The statesman, as he threads the labyrinth of human progress; the philanthropist, as his genial love to brother man prompts him to deeds of benevolence and mercy; the scholar, as he would give to his expanding mind its highest the people's health constitutes the people's safety.

If scientific medicine is thus promotive of the public good, how important that public sentiment should foster, by every

Page 23

fair means, competent and moral physicians; and how unjust that the Legislature should treat them with such cold neglect, as to place them on an equality with ignorant medical pretenders.

In what relation of society is the scientific physician not of great value? In important monied suits of higher courts, involving questions of mental competency to dispose of property, his opinion is invoked as an indispensable element in the decision. In criminal trials, the evidence furnished by the knife, or the microscope, or the crucible--instruments which the physician alone can use--often saves the innocent from the hangman's rope, or executes the vengeance of the law upon the guilty murderer, when the testimony of human fallibility, prejudice, or revenge, would have hanged the former and spared the latter.

His worth is evidenced in those outbursts of popular impulse that supervene when the community is panic-stricken with the fear of some desolating epidemic. It is on such occasions, when there is no real cause for alarm, that the physician pours oil upon the troubled waters, restores quiet and social order, and gives to crippled commerce its former activity and usefulness. But when fear yields to sad reality, and the dismal cloud of woe and death hovers around, to whom do the people fly for preservation? The physician. He, it is, who now regards the post of danger as the station of honor and duty. He rises with the importance of the occasion. He presents, by his labors, scenes of heroism and sublimity unequalled in the annals of bravery and noble deeds. He responds alike to the calls of poverty and wealth. He consults no considerations of gain or distinctions of society; he needs no other incentive than the wants of the stricken and afflicted. Vigilant by day and by night, he heeds not freezing cold nor lurid heat, nor pestilential vapor, nor self-preservation, until too often the shaft, which his own skill has frequently averted from others, is turned with unerring fatality to his own heart, and he falls a martyr to science and humanity. This heroic character of the profession is illustrated in every plague which has scourged mankind, and every epidemic that has depopulated cities.

The medical profession is not surpassed by any other in its taste, learning and public spirit. The members of no profession have been more noted for exhibitions of the highest powers of the mind and the noblest affections of the heart. The annals of philanthropy combine with the voice of genius and letters, in all ages, in attestation of this truth. Who have always manifested the greatest sympathy for suffering humanity?

Page 24

Who have been foremost in erecting hospitals for the sick, asylums for the deaf, dumb and insane,--poor houses for the outcasts of poverty? Who are the leading spirits in the great moral reforms of the age? Who are among the foremost in founding schools and colleges, libraries and museums, and erecting houses of public worship? Who, with the panoply of science and philosophy, co-operates most effectually, in modern times, with the statesman in his warfare with the fanaticism, ignorance and prejudice that has threatened to destroy our glorious Union? Who goes with the missionary on his sublime errand to the heathen, to aid him to cleanse the leper, heal the sick, open the eyes of the blind, and unseal the ears of the deaf, to the end that the hearts and minds of the benighted may glow with the light and warmth of the glorious Gospel? History, with her thousand tongues answers-- Physicians.

Surely such a profession presents most imposing claims upon public favor, as well as upon the attachment of its legitimate members. That it has defects and discouragements I have endeavored to show. But after all, for one, I would not exchange the pleasures of its pursuits for all the applause which admiring Senates or fickle multitudes have bestowed upon the most gifted statesman; or for all the laurel wreaths of victory that ever decked the brow of the most illustrious military chieftain. Its importance is second only to the mission of Him who holds the lamp of that glorious Revelation that teaches man his duty on earth, and points his pathway to Heaven.

When the walls of Jerusalem were to be rebuilt, it was a law that each citizen should repair the breach opposite his own dwelling. So likewise with the broken entrenchments of the medical profession, if each member would repair the breach that covers his own ground, a wall would be erected that would shield it from encroachments without and dangers within. Then would the escutcheon of medical science shine with resplendent lustre, and the profession be advanced to a position of honor, confidence and usefulness that would forever silence the croakings of its adversaries. Then would those petty jealousies and interferences, so disgraceful to the profession, be displaced by a spirit of peace, concord and brotherly love, so ennobling to the mind and elevating to the heart of the medical man.

These ruptured defences have injured medical science and the character of the profession in the old North State. To repair them is the great object of the State Medical Society. It seeks to accomplish the work by the moral power of voluntary associated medical effort. The society has been in existence

Page 25

eight years. It has struggled on amid many obstacles; it has had to contend with the timid fears of friends, as well as with the secret wiles and open opposition of enemies. It has, however, gradually increased in numbers and influence, and the vast good it has already accomplished is everywhere acknowledged. It has annually garnered a valuable fund of medical knowledge from the abundant fields of observation and experience of its members; and this stock of knowledge is for the common good of the whole profession. It stands forth as the representative of the profession of the State, and therefore is regarded at home and abroad as an embodiment of the dignity and usefulness of medicine in North Carolina. It claims the right, therefore, to appeal through you, Mr. President, to the regular physicians of the State to attend its meetings, and to unite with us heart to heart and shoulder to shoulder, in the great work in which we are engaged. State pride, suffering humanity, science contending with impudent hosts of medical imposters,--all call upon the true medical men of North Carolina to give their names and influence to the Society in her laudable efforts to relieve human misery, and to elevate the profession. "No time to leave home and patients" will not do as a plea for absence from year to year, in face of the fact that our most faithful attendants are those of the largest practice, who make the greatest sacrifices at home, in order to attend the meetings. The Society is everywhere receiving the encouragement of public approval, and the wonder and regret is that more do not apply for admission. It excites more and more astonishment among the intelligent and prominent members of the community, when it is known that any physician in the State, who has the proper sort of attachment for his profession, has not applied for membership in the society. The motives which instituted it, the exalted objects aimed at its harmonious deliberations and operations from the first, render the prediction reasonable, that the time is not distant when its certificate of membership will be a more reliable evidence of medical merit, and a better passport to public favor, than is guarantied by a diploma from very many of the medical colleges of the country.

The Society presents her claims in no temper of arrogance or selfishness. She has no aims that are not for the equal good of the whole profession. She seeks no exclusive privileges, no advancement of any member, or set of members, in preference to others, but her honors and benefits are alike open to all whose bosoms are the abodes of justice and honor, and whose minds are illumined by science. Her schemes of power are the triumph of truth over error, light over darkness,

Page 26

health over disease; her schemes of wealth are the accumulation of the rich ores of science, from the inexhaustible mines of nature, observation and research.

Let us, fellow-members, renew our vows, that it shall receive the sustaining power of our best exertions--that its course shall be onward and upward. In its progress thus far, we are striving to erect a medical fabric that shall rest, broad and secure, upon the eternal foundations of truth and medical philosophy. Let us enlarge its dimensions by annual offerings of materials from the luxuriant fields of our own medical experience. Let us raise its summit higher and higher, until its radiant beams of knowledge shall dispel the darkness of medical ignorance and delusion, and re-animate the profession from the seaboard to the mountains. So that, hereafter, when, in the course of time, our places shall be filled by others, they may view the work we have accomplished, with a grateful admiration, which will impart a glowing inspiration to their energies, and encourage them to strike with strong arms and stout hearts, in the great cause of Medical Progress.

Return to Menu Page for Obstacles to Medical Progress... by S. S. Satchwell

Return to The North Carolina Experience Home Page

Return to Documenting the American South Home Page