Bertie: or, Life in the Old Field. A Humorous Novel:

Electronic Edition.

Throop, George Higby, 1818-1896

Funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Tampathia Evans

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Meredith Evans, and Jill Kuhn Sexton

First edition, 2001

ca. 380K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

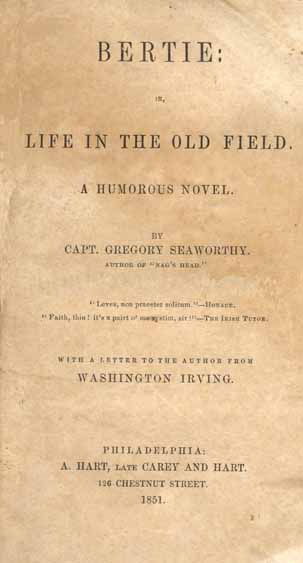

(title page) Bertie: or, Life in the Old Field. A Humorous Novel.

Capt. Gregory Seaworthy (pseud. of George Higby Throop, 1818-1896)

242 p.

Philadelphia

A. Hart, Late Carey and Hart

1851

Call number VC813 T529b (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 24th edition, 2001

Languages Used:

- English

- Latin

- Italian

LC Subject Headings:

- Dialect literature, American.

- North Carolina -- Fiction.

- North Carolina -- Humor.

- Norfolk (Va.) -- Fiction.

- Norfolk (Va.) -- Humor.

- Bertie County (N.C.) -- Fiction.

- Bertie County (N.C.) -- Humor.

Revision History:

- 2002-06-14,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-09-24,

Jill Kuhn Sexton

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-07-31,

Meredith Evans

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-07-16,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

Title Page Image

Title Page Verso Image

BERTIE:

OR,

LIFE IN THE OLD FIELD.

A HUMOROUS NOVEL.

BY

CAPT. GREGORY SEAWORTHY.

AUTHOR OF "NAG'S HEAD."

Leves, non praceter solitum."

HORACE.

"Faith, thin! it's a pairt o' me systim, sir!"

THE IRISH TUTOR.

WITH A LETTER TO THE AUTHOR FROM

WASHINGTON IRVING.

PHILADELPHIA:

A. HART, LATE CAREY AND HART.

126 CHESTNUT STREET.

1851.

Page verso

ENTERED according to the Act of Congress, in the year 1851, by

A. HART,

in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Eastern District of

Pennsylvania.

PHILADELPHIA:

T. K. AND P. G. COLLINS, PRINTERS.

Page iii

TO A. HART, ESQ.

MY DEAR SIR--

To whom so appropriately as to yourself can I dedicate the following pages? Very few things could give me so much pleasure as the knowledge that the volume will seem to you a worthy token of the hearty regard with which

I am

Yours, always,

GREGORY SEAWORTHY.

PHILADELPHIA, Dec. 15, 1850.

Page v

PROLEGOMENA.

TO THE READER.

I.

WISE men are in coveys,

Schoolmasters abroad;

And to hills of science,

Lo! a royal road!

Some are writing folios,

Some are writing odes;

While I worship COMUS,

Only, of the gods.

II.

Some are dropping honey,

Others dropping gall;

I am merely funny--

When I write at all.

Simply to amuse you

Do I choose to write;

All herein that's better

'S accidental--quite.

Page vi

III.

HOLMES was once too funny

For his valet's good;

So, I've been less merry

Than I really could!

Offer to Minerva,

But reserve a part;

COMUS and VACUNA

Both demand A. HART!

Page vii

"INTRODUCTORY WORD TO THE READER."

MY DEAR READER:--

Do you know that publishers still cling, with the tenacity of first love, to the time-honored custom of writing a preface? It is verily so! And even my Prolegomena will not pass muster in this behalf. Wherefore, though you will not read this preface, and do not care a straw why I have written another book, I may as well say, briefly, that I was mainly encouraged so to do by the reception of "NAG'S HEAD," and by kind letters from older brethren, among which is the following:--

"SUNNYSIDE, Sept. 17th, 1850.

"MY DEAR SIR--

"Though I received in due time your letter dated August 11th, your book did not reach me until within a week past. I thank you most heartily for the pleasure afforded me by the perusal. You have depicted scenes, characters, and manners which were in many respects new to me, and full of interest and peculiarity. I allude more especially to the views of Southern life. We do not know sufficiently of the South; which appears to

Page viii

me to abound with materials for a rich, original and varied literature.

"I hope the success of this first production will be such as to encourage you to follow out the vein you have opened, and to give us a new series of scenes of American life both by sea and land.

"With best wishes for your success,

"I remain, very truly,

"Your obliged friend and servant,

"WASHINGTON IRVING."

Page 13

BERTIE.

CHAPTER I.

NORFOLK: "THE BETTY WARREN."

--"A rotten carcass of a boat;

The very rats instinctively had quit it."

THE TEMPEST.

WE were not the only sufferers by the gale. We were fortunate for that matter, in comparison with others, that came straggling in like a covey of partridges, scattered by a sportsman and his well-trained pointer. We had escaped with so small an injury as the springing of the head of our foremast, while one vessel, that anchored near us, had been dismasted. They reminded me, as they flocked to the anchorage, of the frightened landbirds, which one sees flying to a ship's rigging, when blown off shore by a westerly gale. They seemed eager to be once more at rest; and the busy, useful, homely, Lilliputian canal-craft nestled to the wharves as if they did not feel safe, even there, from the fury of the still raging storm.

One of these last lay near us. She was a schooner of--possibly forty-five tons. She was laden scuppers-to, with fish; and the muddy swells gave now and then,

Page 14

as they rose and fell, a glimpse of her name, achieved in no very clerkly characters on the much-battered and time-embrowned stern; reminding one of the mysterious hieroglyphics in the wasteful blazonry of the tea companies' importations. Most persons, however, would have decided that the characters were English--as, indeed, they were; to which assertion I hold myself ready to "qualify." She rode uneasily on the tossing waves, which were most literally casting up mire and dirt; and kept up a fussy, fidgety clatter of ropes, and creaking of booms, and rattle of blocks, and slamming of cabin-doors, as if she longed to hug the dilapidated, rat-haunted old wharf, and thus to feel that she was safe.

She must have been built since the flood.

I have just re-perused the whole of the Scripture History from the first chapter down to the resting of the ark, and I am ready to make affirmation that no such craft existed before the building of that vessel; for, if there had been such a specimen of naval architecture, tradition would never have suffered the moss to grow over its memory. It is more than probable that she had once boasted a coat of paint, of many colors it must have been, for there were not only spots of palpable red, and green, and black, but shades that, I am very sure, were never legitimately begotten of any of the primary seven. There was a streak of red about the hawse-holes, that gave her a rowdyish look of late hours and gin-drinking; and a glimpse of her bottom, as she rolled testily on the soiled swell, exhibited a shocking scarcity of ship-drapery, of both sheathing and copper.

She was, moreover, very manifestly leaky; whether from some "typhoon" on "the raging canawl," or from

Page 15

the more stormy billows of the roadstead above the hospital, I know not. Certain it is that there was a tall cadaverous man, with an antediluvian hat, and a complexion that assured me that he had been shaken well nigh to death with what Shakspeare calls "a burning quotidian tertian, that it is most lamentable to behold"--the ague and fever videlicet--who pumped by the hour. He worked so steadily that I began to think him a part of the machinery of the vessel, until he rose suddenly upright, pulled off the venerable hat, whose years should have prevented the indignity, and, throwing it furiously on the recumbent barrels of shad, exclaimed:--

"Dod dog the leaky old tub! Je-rooz-lum! Ding it all to dingnation! Ain't I ben pumpin' here, I should like to know, for the last three hours? Scuppers tew, when I turned out this mawnin', and she 's making water this blessèd minnit, four hundred strokes a' hour! Laz'rus! You Laz'rus! lay up here and lend a hand to this 'ere bloody old pump! I wish the old Betty Warren was in Davy Jones' locker!"

The smoke curled sluggishly, and in huge volumes, from the dilapidated old galley, and added fresh swarthiness to the dark, smoke-embrowned, water-soaked sails. The tiller stuck fiercely up, at an angle of fifty degrees. It was lashed amid-ships; but the rudder groaned, and squealed, and thumped in the casing as if it would "shake the sticks out of her." This would have been no very difficult matter; for they were of a piece with the hull. The un-tarred, flax-colored shrouds, and fuzzy running-rigging hung down like straggling locks from a head partially bald; and the wind wheezed, and puffed, and

Page 16

whistled, as it tossed them about--as if it were afraid of bringing the entire top-hamper to the deck. Then there were odd ends of rigging (what is it that they call them at sea?) hanging in slatternly profusion all over the vessel. The starboard davit was fished with a billet of wood. The bowsprit stood horizontally and defiantly out; its nose battered out of all its original lines of form. The windlass looked as if it had survived an attack of paralysis; and the cable might, "to all human appearance," have been made in the smithies of Tubal Cain, the "instructor of every artificer in brass and iron."

Attached to the traveler, by a painter, which, for aught I know, may have done duty through Cook's voyages and the Exploring Expedition, was

"A rotten carcass of a boat;"

so old as to afford another argument (if they knew of it) to the people who give a new version of the Mosaic chronology, in favor of the existence of the earth at a period of which garrulous Tradition has not conceived even in his dreams. There was one thwart in it; and a gourd, and a paddle. It nestled touchingly and filially (it was almost full of water) to the parental side, with a look of uncomplaining dejection, approaching to resignation and meekness; as if it had desperately resolved, and expected as a matter of course, to go down to "the ooze and bottom of the sea" with its decrepit mother.

NORFOLK.

"So, this is Norfolk, eh?" I exclaimed, as I ended my examination of the Betty Warren, and looked slowly

Page 17

around me. The water, as far as the eye could reach, was discolored, and filled with veins of mud. On shore, everything looked bleak and deserted--as most things do in the first days of March; and the hospital was a redeeming feature of the scene as it gleamed pleasantly in the beams of the morning sun. The smoke was blown fiercely aside from the chimney-tops, without ever a curl, for all the world like the white locks of Lear, in

"The peltings of the pitiless storm,"

as you see them in pictures; going horizontally off "into thin air;" whirled and twisted, at last, into impalpable shreds by the fury of the gale. Our single anchor began to drag, and we let go our best bower. With two anchors ahead, and a scope of forty fathoms on the smaller, our good schooner then rode more quietly at her moorings.

It was fortunate for our venerable companion, the Betty Warren, that she was well in shore, where the warehouses protected her, in some measure, from the fury of the wind. As it was, she rolled and pitched as if she were wrought into a tearing passion by the obstinate pertinacity of the easterly gale. She threw her nose high in air, now and then, as if she would have said, with her most contemptuous sneer, "I hope you don't call this 'ere little fluster a gale o' wind!"

And then she would bend her head low down, burying her wrinkled and battered cheeks in the muddy swell; shaking her unkempt locks, the unfettered running-rigging and Irish pen'ant's in the wind, like a beggar on a market day in March.

It was Sabbath morning. The church bells were ringing

Page 18

pleasantly their sober peal. Some half-a-dozen young men, with whiskers and gossamer canes, all in clerical black, were lounging under the lee of the warehouses, to enjoy rest and sunshine at the same time. There, too, was the hard-handed laborer, with his neatly-clad little boy; the holiday finery and "shining morning face" pleasantly in tune with the warm sunshine, which was lending a sombre beauty to even a March landscape. The rude wind had kindled a ruddy glow upon the faces of both; and they seemed to be enjoying with hearty zest the free gifts of Heaven's breath and smiles, outside of brick and mortar.

As we could not immediately go on shore, I went into the forecastle. One of the crew was writing a letter; his table being constructed out of a couple of trunks. The labor, I venture to say, was more formidable to him than making up the bunt of a topsail. He bent his head starboard and port, like a polka-dancer; wrinkled and distorted his phiz; thrust his tongue finally between his teeth; stopped now and then, and then went on, as one who takes thought what he shall write. His pen leaned fearfully over, like the masts of a pinkey in ballast; and he crossed the t's and dotted the i's with much the same gravity, and deliberation, and stateliness, with which Burleigh is said to have nodded. When at length he had finished it, he laid the pen, with gingerly circumspection, across the inkstand, leaned back, and rubbed his hands with a look of immense satisfaction, as if he had, unlike Keyser, survived a burning at the stake, and been called a "great doer" by Luther himself. Had he been classic in his readings, he would have broken silence, and said:--

Page 19

"Hic extremus labor; hæc meta viarum!"

As it was, he merely said--

"There, I guess I've got that 'ere bloody thing done up and backed ship-shape!"

Little Frank was snoring lustily in his berth; resting as pleasantly upon his hay-bed, and underneath his rude coverlet (the boat-sails), as if he were reposing upon the down of the cygnets of the Ganges. Commend me to genuine physical toil, and a hay-bed! There is nothing like them in the whole world. And then the conscious mesmerization into the broad, sunlighted land of dreams. Sancho Panza should have ridden out a north-easterly gale in March, on the North American coast, to have uttered, "with due emphasis, and sound discretion," (do I quote it rightly?) his memorable benediction upon "the man who invented sleep." Eight hours in the lee scuppers, for three or four successive nights; a few hours a-day! at the pumps; and his trick at the wheel, during two interminable hours of rain and sleet; and there would have been a ringing, tingling, stirring emphasis in his tones when he said, "Blessings on the man who invented sleep! It covers one all over so--like a garment!"

Anon, the news-collector came off to us. He reported many accidents of the gale; and after some conversation with the captain about our own damages, the propriety of a protest, and a telegraphic dispatch to the owners, very politely offered me a passage to the ferry-wharf. I packed my trunk, and bade my ship-companions goodby. In half an hour I was in snug quarters at my hotel.

Page 20

CHAPTER II.

NORFOLK--A NEW ACQUAINTANCE.

"Urbs ANTIQUA fuit."

"Leave patience to the gods; for I am human!"

RICHELIEU.

BEAUTIFUL, romantic Norfolk! I like Norfolk. I like its staid, quiet, ancient air of Quaker-like garb, and respectability, and neatness, and substance, and comfort. Whole regiments does it muster of fine women and charming girls. For the midshipman, it is Eden; for the epaulette--Elysium. Old ocean has an arm half way around her, in a doting embrace. A little way from the brick and mortar barrenness of the business thoroughfares, you come to the shrubbery and flowers, and roominess of residences. Farther still, neat white cottages, with wealth of rural attractions, peer pleasantly from the evergreen woods; inviting a glance at the vine-covered trellis, or a bright eye beyond it. By moonlight, Norfolk is enchanting; and of a mild summer night, the moon's "golden haziness" falls as beautifully there as at Rio Janeiro, or Naples; on Melrose, or the Rialto.

Such, at least, was my opinion when I was returning, one evening, during my brief sojourn from a walk through the more frequented streets of "The Ancient Borough." All the world was walking by moonlight. Here, a gray-haired old man was leading merry children along the

Page 21

crowded thoroughfare. The pale, thoughtful student sauntered slowly on; busy, apparently, in investigating the mineral properties of the dilapidated pavement beneath his feet; while above, there lay the whole heavens, like a silver sea, with isles of gems. Manhood and beauty went side by side, and over all the throng there was the witching of the soft moonlight, giving to furrowed brows the air of beauty, and to "ruins gray" the charm of proportion. A fair young girl passed me. A profusion of dark curls fell upon her neck and shoulders. Her form was of faultless outline, and her step that of a sylph. Her dark eye glistened, as she leaned lovingly and trustfully towards a young officer, whose uniform glittered in the moonlight as they sauntered along. Ever and anon, the young lover (I was sure he was an accepted suitor) drew his form proudly up to its full princely height with an air of defiance; as if an ungentle look from a passer-by at that fair girl would have provoked him into an "incensement" like that which Viola was taught to expect in the blood-thirsty, fire-eating Sir Andrew Aguecheek: "So implacable that satisfaction could be none, but by pangs of death and sepulchre!"

I caught myself "sighing like a furnace;" and was turning to go to the hotel, when I was somewhat familiarly accosted, in the unmistakable twang of eastern Maine, with

"Haow dew yaou dew?"

I accepted the proffer of a broad, hard hand; and received a shake that would have delighted the sage of Quincy in his most vigorous days.

"I am quite well, I thank you," I replied, a little ceremoniously. "But I--"

Page 22

"O, ya-a-s! Exactly. You don't know me, I guess you was a goin' tu say. No more you don't. I might ha' known it. My name's Professor Matters."

"Professor Matters," said I, a little mystified, "I am happy to make your acquaintance. May I ask what chair you occupy at the present time?"

"Hey?"

"I mean, what college you--"

"O ho! now I understand ye. I don't zactly b'long to no college; but I'm a professor of what minister calls hydrology.'

I was now thoroughly mystified.

"I hope you'll excuse me for takin' so much liberty; but I knowed you was a Yankee, and so I thought I'd speak tew ye. It's a rale satisfaction tu me tu meet a man that walks as if he'd suthin to walk for; and not like these 'ere sleepy Southerners, that walk jest as if they'd had the yaller fever. I won't keep ye, though," added he, seeing that I was getting uneasy; "good night! Maybe we'll see one 'nother ag'in."

"May the gods avert it!" said I, devoutly, as he turned away; and I returned to the hotel with the resolution to leave Norfolk on the following day. I made the proper inquiries of the clerk. There was no vessel, he said, going South, sooner than the day after the morrow.

On the following day, a friend invited me to visit the Pennsylvania. I declined; giving as my excuse the fact that I had often been on board of her.

"But there are some ladies going on board."

"That alters the case."

"You'll go?"

"Yes."

Page 23

"Sharp three, this afternoon."

"Very well."

Accordingly, at three o'clock, I found a gay party in the act of embarkation at Ferry wharf. Two of the Pennsylvania's cutters, with their gay pennants flying, were alongside the wharf; and both were closely stowed with ladies and gentlemen.

"Shove off there, forward," said Lieut. P--; "let fall! give way!" and our neatly dressed boat's crew bent to their oars. We were welcomed by a march from the band, as we reached the accommodation-ladder; and, as we stepped on deck, were most politely and cordially received. The few necessary presentations were got through with the ease and tact belonging always to the well-bred gentlemen of the quarter-deck. There was no parade, no bustle, no fuss.

As the dinner-hour had not yet arrived, we strolled about the decks of the noble ship, and our fair neighbors were initiated (somewhat briefly and imperfectly, if the truth must be said) into the names, uses, and mysteries of divers parts of the armament and rigging. I was in unusually good spirits that day. Chance consigned to my civilities Miss Rosalie D--, a charming young woman, whose acquaintance I remember as one of the pleasantest in my life, and who, alas! has married and gone away to the far South. May she live forever! We had a delightful chat. I had answered her thousand-and-one questions about the ship; and was getting into rather a dangerous habit of looking into her eyes--there was never a finer eye in all the world--when, just as we were coming out of the commodore's cabin, there appeared to me, hat in hand, and with a smile that engulfed

Page 24

all other dimensions in the single one of openness, my friend Professor Matters.

"Human natur!" he exclaimed. "Is this yaou? Why, haow du yu du?"

"I am quite well, I thank you."

"Glad to hear it! How dew yaou dew, ma'am?" added he, turning to my fair companion.

She seemed to get the bearings, if I may use a marine phrase, at once. It was impossible to be angry with the man, and, therefore, I felt a sensation of delighted relief when she replied, easily,

"I thank you; I am in excellent health and spirits. Have I had the pleasure to meet you before to-day?"

"Quite likely, quite likely, ma'am. I'm pretty tol'bly well known here to Norfolk. My name's Professor Matters."

"Professor Matters, I am delighted to make your acquaintance. I hope Mistress Matters and the young Matters are quite well."

"You're aout this time!"

"How?"

"They aint no such Lady as Mrs. Matters."

"I'm delighted to hear it."

"Git aout! I--"

"Excuse me for interrupting you. Here comes my friend Lieutenant P--; and I am going to request him to invite you to dine with us. Lieut. P--, may I beg the privilege of having another plate laid?"

"Most certainly. For whom?"

"Permit me to present you. Professor Matters, allow me to present to you my friend Lieut. P--. Lieut.

Page 25

P--, this is the celebrated Professor Matters, of--what col--?"

"Ah! Steventown, ma'am; State of Maine."

"Of Steventown."

The Lieut. entered into the spirit of the joke, and did the honors with the profoundest gravity. Even Commodore --, who is a bit of a wag, aided in the mystification of the professor, and spun him some yarns of his voyages that caused his listener to open his eyes in wonderment, as he exclaimed, most fervently,

"Git a-o-u-t! SHO! ye don't say so! Commodore, you can take my hat!"

On one of these occasions, he actually offered the venerable hat to the commodore. As he did so, he caught a glimpse of a letter inside.

"I never showed this letter, I b'lieve, commodore," he said, as he looked at the superscription. "That's from my friend Professor Jinkins. You may read it ef yew want tew."

The commodore put on his spectacles and read the superscription--

"PROF. FATTY MATTERS,"

"Norf--"

"Connecticut river! scissors! darnation!" exclaimed the professor. "Didn't I tell him to write it F. MATTERS? I say, commodore, don't tell anybod--."

But it was too late. Lieut. P-- and my fair friend had heard it. The word, in sea-phrase, was "passed along," and then came a smile, a grin, a titter, a choking, a burst of uncontrollable laughter; and this grew

Page 26

to a roar as the professor threw his dilapidated hat furiously down on deck, and himself went off into an Ætnean convulsion of merriment.

"Don't say nothin'!" said he, as the roar subsided. "Don't mention it! I'll stand treat all round!"

Never before or since has the ward-room of the Old Pennsylvania so rung with loud, long, irrepressible laughter. To describe the scene at the dinner-table would be too long a digression. I must defer it for a future day. We returned on shore.

In the evening, as I was chatting with mine host, I heard the bell of a neighboring church.

"Is there a meeting?" I asked.

"Yes; at Mr. A--'s church. Would you like to go?"

"Very much. I have heard something of Mr. A--."

We went to church. The house was thronged with "the beauty and fashion" of the city. Mine host's pew was speedily filled, and the services had already commenced, when, with a look as sanctimonious as that of Joseph Surface, in came my friend the professor. He stopped at the door of mine host's pew (who politely gave him his own seat), nodded familiarly to me, deposited his hat, and, drawing forth an immense bandana, so flourished it as to draw upon him the inquiring gaze of the congregation. He, all-unconscious (apparently so, at least), fastened his eyes upon the preacher.

The hymn was given out. The professor declined the proffer of a hymn-book, and pulled from his pocket a book of his own, which, to judge from its appearance,

Page 27

might have been used in the days of the covenanters. The tune was Old Windham.

O! Handel and Haydn! O! the Boston Academy! O! Spirit of sweet sounds!

With an earnest zeal, not according to knowledge, and an exertion of lungs which sent the blood to his cheeks and forehead, the professor broke ground in the opening notes of Old Windham. Loud, shrill, sharp, fierce, unmitigated, and remorseless, like unto

"The notes that erst blew down

Old Jericho's substantial town,"

partaking the lulling soothingness of complaining saws, in their teething agonies, the softness of the notes of donkeys, and guinea-fowls, and peacocks, intermingled with broken-winded clarionets, tin horns, the voices of belligerent cats, and the breaking of much crockery, was heard the professor's voice. It was all fortissimo; no cadence, but unbroken "monotony of wire;" with now and then a nasal, tremulous shake on some note, a whole measure behind the choir. It met you like a dry north-easter, in turning a corner, on a February day, in the City of Notions. Elderly people looked puzzled--waggish people looked interested--humorous souls were in a state of what is sometimes called intense fructification--the minister rested his head on his hands--the deacons frowned--the girls tittered--while, for myself, I bowed my head to the book-rack, and held my aching sides.

The day is long past; but now and then, as I have done while writing these lines, do I live over again the roar of laughter in which I indulged that night, as I laid my head upon my pillow.

Page 28

Having decided to leave Norfolk in the morning, I went to the clerk, and gave the necessary directions about the disposal of my baggage. I remember the intense satisfaction with which I congratulated myself on the skill with which I should spring the mine on my new and somewhat over-sociable acquaintance. I do not now recollect, however, whether or no I had ever heard of the proverb which recommends people not to shout until they are fairly out of the woods; or of that other which speaks of coming for wool and going home shorn. If I had, I must here confess to the reader that I had either wholly forgotten the same, or else that the seed of wisdom had fallen on stony ground.

I was early astir the next morning. The clock told five as I stepped to the office.

"I hope Mr. Seaworthy has found his stay in Norfolk agreeable," said the polite clerk, as the porter lifted my trunk.

"I thank you. Too agreeable, by far. I should have been away a fortnight ago."

"You take passage in the Betty Warren?"

"Yes."

"I'm afraid you'll find a dull berth of it; and, if it rains, you'll be sorry you didn't wait for a better vessel. There'll be a dozen of them going out in a day or two."

"I thank you; I have a special fancy for the Betty Warren. Good morning."

"Good morning, sir."

"Pleasant passage to you, Mr. Seaworthy."

"Thank you."

Directing the porter to go to the wharf of Hardy and

Page 29

Brothers, I stepped into Barclay's to buy me a map of "The Carolinas"--an indispensable article, let me say, to any one who travels thither. I had opened one of them, and was examining it, when a loud, shrill, ringing, nasal voice at my elbow exclaimed--

"Guess I must hev one o' them 'ere! Scuse me, sir; but 'ud you 'low me to look at that 'ere map?"

"Certainly," said I; and I turned to look at my neighbor. He had removed from his head the most dilapidated white hat which I have yet seen on the American continent; deposited the same on the counter, with as careful a solicitude as Brummel would have laid a cravat in the same place; and, without any signs of recognition, drew a pair of rusty spectacles from a greasy case, adjusted them, held the map off at arm's length, and gazed thereon in utter abstraction.

"Um! Ya-a-s!" said he, at length. "Don't seem to be many towns in Ca'lina, anyhow."

I had a moment's leisure to observe him. He was a strongly built man, of--perhaps forty years of age. His features were large and strongly marked, particularly the nose, which was prominent, distinctive, unmistakable, and emphatic. The hair was long, and of raven blackness; and a long, matted lock hung obliquely over a bald spot on the top of his head, the precise locality on which Uncle Ned, immortal in song, had never "a hair of him for memory." His eyes were very dark and piercing, but intelligent and good-humored withal; and his whole cast of features and frame betokened more than ordinary vigor of body and mind. There was a goodly array of wrinkles centering at the outer corner of the eye, which gave a world of emphasis to

Page 30

the genuine twinkles of fun and drollery which occasionally flashed from it. He was looking down intently upon the map, his head bent low over it, when suddenly he seemed to have found what he sought, for he looked up at the bookseller, and said--

"Mister, I'll take this 'ere. Scuse me, sir"--turning to me--"I forgot that I took it from yaou. I--ah!"--here was a start of surprise, which would have made his fortune in a provincial theatre--"how dew yew DEW? Glad to see ye. When d'ye git off?"

"To-day," I replied, in answer to the last question.

"To-day, hey? Why, I'm goin' to-day myself. P'r'aps we'll meet ag'in somewhere or 'nother."

"Very likely."

"Wal, mister, here's the change. Tew shillin's I think you called it?"

"No, sir; three."

"Ah! wal, that's more'n I ever paid afore. Beats all natur how these 'ere South'ners dew stick on the price."

"Kin you tell me"--turning to me--"the best route intew North Ca'lina? I contemplate takin' a tower over there."

"The most direct, perhaps, is the stage route. I'm a stranger here, however; and Mr. Barclay can tell you more accurately."

"Wal, I'll be much obleeged tew him."

"You can go by the railroad, if you choose," said Mr. B--, politely; "or by stage; or by the canal."

"What canal?"

"The Dismal Swamp Canal."

"Git aout! Who'd 'a thought that 'ere canal begun here to Norfolk? P'r'aps yew'll go that way?"

Page 31

"Possibly I may."

"Wal, anyhow, I hope we may run ag'in one 'nother once more. No doubt we shall, somewhere 'nother. Good mornin', gentlemen!"

"Good morning," I replied; and Mr. B. outvied me in the politeness of leave-taking.

I drew a long breath of relief at my escape; paid for my map, and was speedily on board the Betty Warren. I found all hands swaying, with might and main, on a huge cask in the hold. The captain informed me that there had been some mistake in the stowage; and that it was therefore necessary to break out a part of his cargo. He would get away, he thought, about one o'clock. I returned to the hotel; passed the morning with the newspapers; and, on my way to the vessel, between twelve and one o'clock, stepped into Myers' for a lunch. I had finished it, and was paying for it, when, forth from the stall adjoining my own, adorned, as before, with the never-to-be-forgotten white hat, came my friend the professor.

"Ah! Mr. Seaworthy; how are ye now? We manage, somehow 'nother, to git together often."

"We certainly do, sir."

"Mr. Myers, let me introduce my friend Mr. Seaworthy!"

I bowed, of course. Mr. Myers was pleased to say, with a smile and a bow,

"SIR! Mr. Seaworthy, I'm happy of your acquaintance. Sir, you're a gentleman and a scholar!"

I bowed.

"Say you'll git away to-day, Mr. Seaworthy?"

"I think I shall. Good morning, Professor Matters."

Page 32

And I turned from him just as his lips were opening to ask how, when, and where?

"Good mornin' tew ye, Mr. Seaweathery," replied my friend; "p'r'aps we'll meet ag'in somewhere 'nother."

"May it be during the Millennium!" muttered I; and I made my way to the wharf.

Page 33

CHAPTER III.

GETTING UNDER WAY.

"Cras ingens iterabimus æquor."

MUCH to my annoyance, I now found that the schooner would not get away until three in the afternoon; at which time the skipper assured me he should positively get under way. His mate had engaged, he said, to take another passenger; but if he, the passenger, were not on board in time, the vessel would not wait for him.

I will not hazard my reputation for veracity by undertaking to say how often I consulted my watch during the two succeeding hours. At last, at a quarter before three, Captain Ragsdale came puffing along with the last of the stores, and gave orders to get under way.

"B'low there!"

"Hello!"

"Come on deck, now, and let's git the bloody old Betty under way. Bear a hand now, you Laz'rus!"

"Sir."

"Luse that 'ere jib. You Sam Hines, ontie that ar fo'sail!"

"Ay, ay, sir."

"H'ist away now!"

"Laz'rus, luse"--so the skipper said loose--"the

Page 34

mainsail thar! Be on yer pins now! Cast off that ar starn fast! This-a-way now, an' help one h'ist the mainsail!"

"Ain't you goin' to wait for the passenger?" inquired Lazarus.

"No!" shouted Captain Ragsdale. "I wouldn't wait for the Gov'nor! I--"

"Hold on there! Yaou! BOY! I SAY!" shouted somebody, as Lazarus was lifting the bow-fasts.

I looked up. There, wheezing like a victim to the phthisic, his venerable and ubiquitous white hat held firmly in his hand, was--my friend PROFESSOR MATTERS!

"Has the Old Man of the Sea reappeared in the flesh?" was my groaning query to myself.

"Yaou boy, what's yer name?"

"Name Laz'rus."*

* A negro says "Name John;" never "my name is," &c.

"Laz'rus what?"

"Name Laz'rus."

"Wal, jest hold on tew that 'ere rope a minnit till I git my baggage aboard, or by the Great Horn Spoon you'll never see Edentown! Here 'tis naow!"

And he pointed to a truck which had just made its appearance on the wharf. On it were two barrels, and, as I found on a nearer approach, a bald, cadaverous, dejected, superannuated hair trunk. There was a trifling delay in getting the barrels on board, as they proved to be of enormous weight; and the skipper had, it seemed, no other resource than to cut the mousing of the peak halyard, and use it (the halyard) for a fall. At last the baggage was on board. The barrels were stowed amidships, and the trunk was borne to the cabin. I caught

Page 35

a glimpse of the card, as it passed me, on which, in large and somewhat unclerkly capitals, appeared

"PROFESSOR F. MATTERS,

STEVENTOWN, Maine."

"This side up, with great care."

"Cast off that ar bow-fast!"

"Ay, ay, sir."

"H'ist away on yer jib now!"

"Ay, ay, sir."

"Stan' by the peak halyards thar! it's goin' to blow a perfect hurricane!"

Even so. In the hurry of getting under way, none had noticed the threatening cloud; but it was evident that we were about to encounter a severe squall. It was not long in coming; and, fortunately for us, we had neared the opposite shore so as to be well under the lee of the buildings. As it was, the violence of the squall was such as to part the jib-halyard, and down came the sail, shivering and flapping with a fierceness that seemed likely to tear it into shreds.

High uprose the voice of the startled skipper, in notes scarcely less loud than those with which Satan is said to have called to his prostrate legions.

"JE--ROOZ--LUM! Sam, lay out thar on that ar jib-boom, and tie up that ar sail! Dont mind the spatterin'!"--(the water was flying merrily over the bows). "Times like these 'ere, duty must be done!"

"Shall I steer for you?" I asked.

"Can you steer?"

"Try me."

"Wal, if you can, you'll oblige me, for that ar jib 'll go to Davy Jones ef I don't go and 'tend to it myself."

Page 36

He went forward. My friend the professor had been holding on to the low quarter-railing during the squall. He now looked round to me with a ludicrous air of overpowering terror, and asked,

"Do yew think we're in much--in much da--danger?"

"Not the least in the world."

"Wal, I can't help feelin' oneasy. I can't swim, and I don't like the looks o' things nohow. I wish I'd tuck the stage."

"I wish you had!" thought I; but I assured him there was no danger.

"DANGER!" exclaimed the skipper, who had just returned from splicing the halyard and setting the jib; "to be sure there ain't no danger. This 'ere ain't a patch to some gales on the Pasquotank and old Albemarle. I'll show you somethin' when we get off the mouth o' the Chowan.* * Pronounced Cho-awn. "Git aout!" "True, as my name's Jeemes Ragsdale." "SHO!" "Fact." "Couldn't you set me ashore, cap'n?" "Too late. Besides, the squall's over. For'ard thar!" "Sir." "Set the gaff-topsail!" "Ay, ay, sir." We were now passing the Navy Yard, and the Pennsylvania's band was playing.

"Wal, if that don't beat all natur," exclaimed the professor; "beats the Steventown band all holler!" "Yes, it's mighty fine!" replied the skipper; "but what's the use on't all? She's a mighty nice vessel, but she costs a blame sight more'n she's worth!" "I used to think so, tew, cap'n," replied the professor; "but the trewth is, that ef the public money didn't go that way, it 'ud go another. Folks will have their 'lowance o' blood, and thunder, and glory; t'ain't no use talkin'. I was out to South Ameriky tew years ago. There was some locations there where the dirty Portygese and Spanishers couldn't git enough to eat; but they must have their glorifications for all that; and them that cussed the government most was al'ays fust to jine in, and shout hooror! The most paradin'est military feller I ever seen was one o' them cholers on the Spanish Main; and he lived in a little doggery of a house, built out o' the ribs of a sulphur-bottom whale. There was Jim Simmons up to Steventown--Stuck, I swow! Cap'n, you're stuck!" We were indeed aground. "Wal, don't you spose I knows it?" replied the skipper, a little nettled at being thus interfered with, in the discharge of his duty. "I never could keep the run o' the bloody channel along here; but anywhere else, I knows it as well as the man 'at dug it out!" "Sartin, cap'n, sartin. I didn't mean no 'fence. Don't get riled. 'Keep your temper' is my rewl. I seen it once over the cap'n's office 'board of a steamboat." We were soon off the bar, and, following the narrow and difficult channel between the low but picturesque shores of the river, we reached the locks just at nightfall.

Why, I've seen worse blows 'n this on the canawl!"

Page 37

Page 38CHAPTER IV.

THE VOYAGE.--THE CANAL.

"Illi robur et æs triplex

Circa pectus erat, qui fragilem truci

Commisit pelago ratem

Primus!"

--HORAT.

THE professor's fears subsided when we had fairly entered the canal. When, however, we had got through the short cut, and re-entered the river, another squall took us on our starboard quarter. Away went the gaff topsail sheet; blocks rattled; the sails flapped with a noise that was almost deafening; the pig, the buckets, and the firewood slid furiously into the lee scuppers, and I fully expected to see our top-hamper go by the board. The professor got hold of the weather tiller-rope, and clung to it with a strain that would have parted any similar piece of rigging of less staunch materials. His whole reliance seemed to be in the skipper. This last functionary was now bareheaded, his long thin locks of uncombed hair blown fiercely back from his weather-browned face; his form erect; his eye flashing, and gleaming at every suspicious point of his marine defences. He had no very great confidence, I was sure, in the qualities of the Betty Warren; but no sailor, however much he abuses the vessel in which he sails, will ever quietly suffer another person to do it.

Page 39

"Blast the bloody old tub!" exclaimed the mate; "I wish she'd go to the bottom!"

"Oh! my dear sir!" groaned the professor, "don't say so. It's fairly flyin' in the face o' Providence. Oh-h-h! Dew yew think she'll tip over, Mr. Seaworthy?"

And, without waiting for my reply, he began to say a line from

"When I can read my title clear,"

when Captain Ragsdale, whose ire had been roused by the mate's disrespectful remark concerning the vessel, broke ground with

"Who the h-- are you, Sam Hines, to be blartin' out sich stuff 'bout this wussul? They ain't 'nother sich a craft on this canawl."

"I don't think they is," muttered the mate.

"What's that? Say that ar agin', and ef I don't send you to plant oysters my name ain't Jeems Ragsdale! You poor corn-chawin' land-lubber! go for'ard thar, and stan' by to take in sail!"

"Ay, ay, sir!" growled the mate, who did not seem anxious to provoke the wrathful skipper to the execution of his ominous threat; and he went forward.

The squall abated, sail was taken in, and we were soon "locked through" into the Dismal Swamp Canal. A little negro stood by a span of mules, ready to tow us. Another span soon came. The drivers sprang upon the backs of two of the mules, and away we went. The professor seemed reserved and thoughtful, and I did not molest him. All was new to me. The drivers kept up a plaintive and monotonous song, improvising in their humble style, and filling the woods, leagues around, with echoes.

Page 40

Why is it that boatmen and sailors are more musical than other laborers? The sailor in the forecastle, and at his work; the gondolier at his oar; (the boatmen on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal call their boats "gundalos!") the ferryman--all are singers. Blacksmiths whistle. Tailors are taciturn. Carpenters are quiet. Shoemakers are merry; but your sailor, or waterman, is almost always a singer. If he be unable to sing, ten to one that he has a rickety old accordeon, violin, or an asthmatic flute, with which he offers whole hecatombs of slaughtered crotchets and quavers upon Apollo's altars. The more deaf the divinity to his importunate prayers, the more numerous the sacrificial offerings. The most persevering votary of the art I ever saw was a mulatto, at sea, upon whose hardened ear fell unheeded the dying groans and complaining sighs of suffering semibreves and minims, whose existence he cut short "aequo pede," with the stride and ruthlessness of the grim reaper who cuts

"The bearded grain at a breath,

And the flowers that grow between."

I suppose it must be motion that provokes this musical development; for your stage-coach driver is always a singer.

The quaint and somewhat mournful strain of the drivers seemed to have awakened a responsive chord in the breast of Captain Ragsdale; for he came pensively down the ladder while I was making some notes of the day's occurrences in my journal, and took in hand with gingerly care an old flute.

"Was I fond of music?" he asked.

"Very."

Page 41

"And so be I," ejaculated the professor.

"Would he disturb me by playing?"

"Not the least in the world."

And without farther parley, he leaned far back in his chair his long, lank, macilent frame, blew into the end of the instrument, snapped the key, and with some such pensiveness as Don Quixote may be supposed to have displayed when he sung

"Love with idleness combined

Will unhinge the tender mind,"

to the enamored Altisidora, he ran his fingers over the holes, as if to quiet and subdue rather than encourage and call forth the elfin medley of startled quavers that came tumbling over each other at the first potent blast of that terrible conjuration. Thirds, fourths, fifths, octaves; intervals before unheard of, and never since spanned by human skill, poured resistlessly forth upon the startled air, and the old canal,

"--unconscious of a flood,

Whose dull, brown Naiads ever sleep in mud,"

seemed to simper its smiling approval by the faint dimple that gathered in its swarthy cheek. The professor was delighted. Strength, and not skill, was evidently his musical standard. Sam Hines and black Lazarus came aft, and sat down near the door. Primus, too, a negro who was at the helm, was evidently beginning to neglect his duty, so absorbed was he by the music. Old Lonzy, a bull-dog, and Jack, a terrier, came to the companion-way and stood looking with canine solemnity at the rapt performer. The former cast some inquiring glances at me, as I sat writing; and I judged, from his

Page 42

puzzled air, that he had failed to satisfy himself what it all meant.

"Dod rot it all, Primus! can't ye keep her off o' the tow-path?" shouted the skipper. "You triflin' feller! you ain't no 'count, nohow, to steer. Laz'rus, take that ar helm!"

"Ay, ay, sir."

The captain now went on deck, and the professor and myself turned in. Just as I was getting drowsy, my companion rose on his elbow and said to me, in a low tone,

"I say, neighbor."

"Well?"

"Yaou remember the dinner 'board the Pennsylvany?"

"Yes."

"'Bout my name?"

"Yes."

"Wal, don't laff 'bout it. It's a serious subject. Now I don't keer to hev it git aout. The trewth is, 'tween you and me, my name's Funnyford. My grand'ther had a pardner o' that name. But I was al'ays rather stocky, and so they got to callin' me Fatty. Professor Jinkins heered some one call me so, and he thought it 'as my name."

"Well, my friend Funnyford, I--"

"I'd a leetle ruther yew'd call me professor, ef its all the same tew ye. Fact is, people 'll call me Funny, sure's ye're born, if they git hold of it."

"Very good, professor; I will try not to betray you."

"Dew, if ye please; and I'll al'ays do the fair thing, and stan' shot till we git to Edentown. Good night!"

Page 43

"Good night, professor;" and I slept. The moon was well nigh at the full, and I did not rest well. One sleeps more soundly, I fancy, in a dark night. Be that as it may, I could hear, in my half-waking repose, the monotonous song of the drivers; their emphatic blows on the "unfed sides" of the jaded mules, and their chirrupping, intermingled with divers epithets and persuasives not proper to be set forth in this history, to quicken the cattle's motion. Captain Ragsdale conjured forth the crickets with his orchestral snore, and the smoke-browned little cabin rung with their song. The rats were performing

"Lavoltas high and swift corantos"

behind the bulkhead; the tow-rope rustled over the low shrubbery on the bank; the rudder squeaked, and the water curled and eddied in a low musical ripple beneath the counter. Ever and anon, the professor would start feverishly from his troubled slumber, with a hysteric, "Oh! O dear! O cap'n!" manifestly dreaming of the ballad-famous catastrophe,

"Then three times round went our gallant ship,

Then three times round went she;

Then three times round went our gallant ship,

And she sunk to the bottom of the sea!"

At last, I sank into a profound sleep, and when I awoke it was day.

"Morning in the Old Dominion," I said to myself as I stepped on deck. We were passing a hamlet on the canal, called, if I remember well, Deep Creek. The spring birds were singing; the sun shone gloriously; the air was fresh and bracing; all was quiet and all was

Page 44

beautiful. So far, the Dismal Swamp had been anything but dismal. The drivers were lying athwart the backs of their cattle, which (I long to call them who) plodded sorrowfully along, with heads downcast, as if life had lost for them its tinge of romance; and they were thinking of other and younger days, when, peradventure, their hearts had been left "fracted and corroborated" by some coquettish jilt of a bright-eyed filly.

The morning wore pleasantly away. The professor busied himself by some abstruse calculations with pencil and paper. I wrote a letter and a page in my journal. A negress, of more than ordinary comeliness and intelligence, accompanied by a very pretty child, took passage with us. I heard her say, in reply to some questioner on the tow-path, that she was "guoin to North Ca'lina visitin'." Her husband came on board soon after, but, poor fellow! he had forgotten his "pass," and was obliged to go back for it. We could not wait for him, and he had a long walk of it to overtake us. Lonzy, the dog, came ever and anon to the companion-way, and looked in upon us with an air of one who is endeavoring to fathom a mystery. He would look, now at the professor's cabalistic formulas, now at the motions of my pen; and then, after a brief consultation with the shaggy little terrier, both the dogs put their paws on the highest step of the ladder, and gravely observed our motions.

We had been hoping for a pleasant day. As the morning wore away, however, we saw some most unmistakable signs of rain. It grew sultry. The cattle trod drowsily along, and the drivers walked silently beside them. The dogs stretched themselves at full length

Page 45

upon deck. The professor turned in for a nap. As I went on deck at noon, we were passing the hotel, not far, if I mistake not, from Lake Drummond. The stage-coach drove up. There were two or three gentlemen inside, who seemed quite too languid to get out; and I caught a glimpse of a fair girl in a mourning-dress, whose head was bound tightly with a handkerchief. Light as was the load, the horses--three leaders abreast and two wheel-horses--ambled slowly and wearily along, oppressed, like ourselves, by the sultriness of the weather.

At length, as we were finishing our dinner, down came the rain. It began with a thin and almost impalpable drizzle.

"I'm mighty 'fraid we're guoin to hev a wet time on't," said the captain, as he donned an oil-cloth jacket and sou'wester. "What do you think, professor?"

"I think we're goin' to hev an etarnal drizzle, an' no mistake!"

He was not far wrong. The rain came faster and faster; the tow-path was speedily a mass of mud; the mules and their drivers, as well as the man at the helm, were dripping with water; the dogs looked wistfully into the cabin; and the captain came below, and sat moodily down, with his head on his hands, evidently anticipating "a wet time on't;" and knowing full well, by sore experience, the sad import of the expression. We discovered, to our great disappointment, that the cabin leaked. But one single corner was there where the drops did not ooze through the deck. Thence it trickled along the carlines down upon our heads. As fortune

Page 46

would have it, the corner in which Professor Matters and myself were sitting proved to be passably dry.

Night came on; and, after a late supper, we endeavored to contrive some plan for a night's rest. To sleep in the berths was out of the question; for the rain was dropping merrily into them, and we had been obliged before nightfall to roll up the bedding, and stow it away in a locker. We spread a matress upon the cabin floor, shut the doors, and betook ourselves to repose. I believe some grammarians reckon repose among the active verbs. I beg leave to say that I favor that classification. Never, to the best of my knowledge and belief, have I so vigorously endeavored to sleep. I counted whole thousands; I listened to the pattering of the rain; I held my eyelids firmly together, and resolutely ignored the fact that the professor was beginning a snore, which, if I might judge ex pede Herculem, would prove a perfect typhoon when the drowsy god should fairly encompass his plethoric proportions in the emphatic hug of the "wee sma' hours." I groaned aloud at the very thought of it.

"What's the matter, neighbor?" asked the professor, in a sympathetic tone.

"Nothing at all, I thank you, professor; but would you oblige me by turning upon your side?"

"Which side?"

"It is immaterial; say the left side."

"The left side it is. Good night!"

"Good night, professor."

"Pleasant dreams to ye!"

"Thank you."

Vain is the help of man. Blessed is he that expecteth

Page 47

nothing. Forth from the professor's nostril, ab imis sedibus, come forth the clarion notes, now in a strain which might relatively be musically denominated pianissimo, now in a crescendo movement; it swelled like the north wind in a Carolina forest of pines, to forte and fortissimo; now plaintive,

"As when Scotchmen grind undying notes upon hand-organs,"

now sharp, short, decisive; stirring one's blood like the shriek of a bagpipe in extremis; now long drawn, sustained, like a colonel's shout to distant squadrons; now crisp, abrupt, emphatic, startling; now--but will the reader pardon the futile effort to describe it? He has but to take down Horseshoe Robinson from the shelf (if it were at hand I would copy the extract), and read how that hero snored, on a certain night when the heroism of a girl saved both himself and Butler from threatened peril. The "grunt" and "snort" of Galbraith, on that occasion, might possibly aid the imagination of the reader in forming some faint conception of the manner in which the professor made night hideous to me. We made but little progress. The cattle were jaded, and they crept wearily along in the mud, possibly two and a half miles the hour. Once, too, in passing another boat, we got aground; and it was a long time before we got under way again. The captain came below and kindled a small fire; but the wood was wet, and it hissed and sung, and smouldered, and flickered, until he gave up the attempt.

I had risen upon my elbow to witness his exertions, and I maintained the same attitude after he stepped out upon deck and closed the cabin-doors. Old "Lonzy"

Page 48

crept in unperceived, dripping all over with the rain; and, setting his feet broad apart on the cabin-floor, he gave himself so vigorous a shake that his ears and tail were for the moment invisible. The weight of the showe fell upon the upturned countenance of my happy fellow-lodger! He rallied a little, and drew the sleeve of his coat (neither of us had undressed) across his lips, and rolled over. It would seem that the captain had not fastened the cabin-door; for I heard the terrier scratching for admittance. In a moment more he succeeded in effecting an entrance, just in time to escape a wrathful kick from Lazarus. That worthy was at the helm, and the blow he meant for the terrier fell harmlessly (to all save himself) upon the cabin-door. I could hear him groan a moment after,

"Ah--h--h! Cricky! Plague take de feller! I bin broke my toe, sartin! Dod dog de luck! Gwine to rain for eber, I b'lieve!"

All unconscious, however, of the perils he had escaped, the dripping terrier, whose every particular hair looked as if it were conscious of the apostolic injunction to "come out and be separate," paused in precisely the same place where "Lonzy" had paused a few minutes before, and again the rains descended, and the floods came in a blinding shower upon the face of the snoring professor.

"Connecticut RIVER! Scissors! H--l!" roared the professor, "who done that 'ere?"

And so saying, his eye fell upon the poor terrier, who was now getting into the proper attitude for the second shake. In the dim light of the smouldering fire, he seized upon the nearest object (it chanced to be one of

Page 49

his own boots) for the infliction of due chastisement. Had the blow reached the poor terrier, there is no telling how soon the author of these pages might have had occasion to write his epitaph--

"Multis ille bonis flebilis occidit."

He had the discretion to vanish--and he survived. The blow, however, upset the oil-can, and left it, bottom upward, in the capacious leg of the professor's remaining boot. I feigned a sound sleep. It was not until he had felt for a long time, on a table and in the locker, that he found the lamp. This, after much asthmatic expenditure of breath, he lighted, and took a deliberate survey of the cabin.

"Je-rew-sa-lem," exclaimed he, as he partially opened the cabin-door. "How like all natur it does rain! Sleeps like a top, that 'ere feller!" (looking at me). "Darn that 'ere tarrier! Hello! Hel-lo! HEL-LO! Here's a go now! What's this 'ere in my bute? Lamp ile, by gravy! Childern of Isril! It's eenamost half full. Wal, Fatty, I should like to know ef you don't estimate that this 'ere's rather a pleasant night on't! Wal, keep your temper, Fatty. I guess you might 'bout as well lay down and git another nap."

How I survived the convulsion of laughter with which my sides were aching, and how I restrained it, I know not. The professor, however, had not, apparently, discovered that I was awake. He left the lamp burning, stretched his brawny limbs beside me, and was soon asleep. He had left the cabin-door ajar, and presently a goodly stream of water trickled down beneath him;

Page 50

while, from a new leak overhead, the big drops began to fall upon his heaving breast.

The night had become cold, and I suppose I ought, in all charity, to have awakened him. I am ashamed to confess, however, that I beheld the descending current with a feeling something very closely akin to satisfaction. Fatigue and drowsiness at last carried the day. The lamp burned dimly; the fire went out, my eyelids drew drowsily together, my head sank back; "the deep, profound, eternal bass" of the professor's snore fell upon unheeding ears. In vain did Captain Ragsdale startle the dull ear of night (who call's it so?) with the nerve-palsying blast of a tin horn, by way of warning to the lock-keepers. In vain did the rain patter, and trickle, and drop, as if discomfort had dissolved herself, in order to be omnipresent. I slept. How long, I know not. I remember faintly, as if it were all a dream, some low mutterings at my side. When I was fully awake, I saw by the expiring flicker of the lamp that the professor was sitting up in that precise position somewhat vaguely described by the words "on end."

"Children of Isril!" now reached my ear, in a low mutter, like distant thunder, "they ain't a dry rag on me, I du believe. Ugh-h-h-h! By the great horn spoon! how cold it is! Feet wet, tew! Blast the old sieve of a boat! Ef I ever git aboard a canawl boat again, may I--howsomever, Fatty, keep yer temper. They're pumpin' the old thing now. Wonder if they're goin' to pump her all night! Shouldn't be surprised ef she'd sprung a leak. Ugh-h! Je-rew-slum, how cold I be! I say, friend!"

Page 51

I made no reply.

"I say, neighbor. Yaou!"

"Eh? Hello! What is it?" said I, drowsily.

"What IS it, indeed? It's a young deluge, sartin. Did you ever see sich a rain?"

"Well, it really has been raining, professor," said I, in the quietest way in life; "we must have had quite a shower."

"A shaower! a FLOOD, you mean. Look a here! Look at my shirt and weskit! (vest.) Jest look at my trowsis, will ye? Look at that 'ere bute! I shouldn't wonder ef my hat was wet."

He pricked up the wick of the lamp, and, in its momentary gleam, the venerable beaver was found with about a pint of water in it, resting as coolly and quietly as if it belonged there. The professor was not long, as may be readily supposed, in emptying the hat, and then he threw it down upon the cabin floor, with a wrathful vigor that I shall never forget.

"Cuss the rotten old thing! It eenamost makes me swear. I wonder what time it is?"

"Half-past two, professor."

"Half-past tew. I wish it was six. I--"

The professor's eloquence was here cut short by the arrival of Captain Ragsdale, who informed us that, if we would put up with such accommodations, (!) we might go into the hold. A part of it was dry, he said, and we could sleep there better than in the cabin.

"No doubt on't!" responded the professor.

We carried our bedding into the hold, and, to our infinite delight, slept uninterruptedly until seven o'clock.

Page 52

We found ourselves at South End. We were not long in locking through. The poles were now taken in hand, and we were, at an early hour, winding along the countless turns of the Pasquotank. We were so fortunate as to be able to lay our course into Albemarle Sound, and, just at nightfall, we let go our anchor abreast of the pretty village of Edenton. I now flattered myself that I should escape the professor. I took leave of him, and evaded his questions as to my destination. On reaching the hotel, I learned that it was court week; and the obliging landlord was pleased to say that he had but a single vacant room; but that that was at my service. He might be obliged, he added, to give me a fellow-lodger; but would not do so, if he could avoid it.

I then made some inquiries about my uncle's family. He knew Colonel Smallwood very well, he said; and would send me across the Chowan in the morning.

"Could he send me early?" I asked.

"As early as you please."

"Say, at four."

"At four."

"Will you breakfast here?"

"A mere lunch, if you please; toast and coffee."

"Good night, Mr. Seaworthy."

"Good night, Mr. Bond."

I may have been abed an hour. I was just falling, at any rate, into a delightful sleep, when a tap at my door awoke me.

"Who is there?"

"Open the door one moment, if you please, Mr. Seaworthy."

Page 53

I did so. Mine host, for it was he, apologized for disturbing me; but said that he was full, and that they were full at Hathaway's; and that he was, therefore, obliged to ask me to take a bedfellow.

"Was it a gentleman of his acquaintance?" I asked.

"No. A stranger."

"And you have no other bed?"

"Not a bed in the house but what has at least two in it."

"Well, then, it is but for a night. I consent."

Mine host disappeared. A servant soon afterward made his appearance with a venerable trunk which I thought I must have met before, in my travels; and while I was endeavoring to decide the query where it could have been, I heard the step of the owner in the passage. I first saw the top of a white hat (not, as it seemed from a hasty glance, in the best possible state of preservation), as the new-comer stooped to enter the low door. The head was then lifted erectly, and a loud

"HEL-lo! why, how DU you DU?" was a whole book of revelation as to the name of my bed-fellow.

"Why, what's the matter? sick?"

"Yes; I am somewhat indisposed."

"I'm trewly sorry; anything I kin dew for ye?"

"No; I thank you."

"When du yaou git away?"

"It is uncertain."

I now called the servant to me, and asked him to wake me at three. He promised to be punctual, and left us.

"I hope I shan't disturb ye," said the professor, as he drew off his boots. I've ordered a bucket o' hot water. Don't feel very well myself; and so I thought I'd

Page 54

soak my feet. That's a nice trunk o' yourn. Where'd ye git it?"

"I really do not remember."

"It must ha' cost ten or twelve dollars."

"I think it more than likely. Excuse me, if you please, professor; I am sleepy. Good night!"

"Good night, Mr. Seaweather! P'r'aps we'll run ag'in one 'nother ag'in, some time."

"I haven't a doubt of it!" I muttered, and I slept.

The boy called me at three. Dressing in all possible haste, and as silently as I could, I left the professor, as I verily believed, in the arms of sleep. After a hearty breakfast, I embarked. I followed the plan I had previously arranged. I landed at Plymouth; sent my trunk back by the boat to Col. Smallwood's; went to Windsor to transact some business; and, about four o'clock in the afternoon of the following day, set out, on horseback, for the CYPRESS SHORE, the residence of my uncle.

Page 55

CHAPTER V.

"AULD ACQUAINTANCE." -- THE ARRIVAL.

"My home! my home! my happy home!"

SONG.

I HAD sent to Cypress Shore, together with my trunk, a note to my uncle, Col. John Smallwood, apprising him of my arrival, and requesting him to send a horse for me, to Windsor, on the following day. The reader who happens to know the geography of the region of which I am speaking, will perceive that I passed very near (in sight of it, indeed) my uncle's house; for it is not two hundred yards from the head of the sound, between the mouths of the Roanoke and the Chowan. It will quite as easily be seen that I went leagues out of my way. In making this detour, I had several objects in view. One was to avoid my new friend the professor; another, to visit an old friend, Dr. Jeffreys, of whose change of residence I had not heard; and another to execute a commission for a New York merchant to his factor in Bertie.

Not finding Dr. Jeffreys at home (he had recently removed to a plantation near my uncle's, known as "Underwood"), I went directly to Windsor, where I arrived about ten o'clock on the same evening. I have known the time to pass "on angel-wings" there; but the earlier hours of the next day seemed interminable. My horse

Page 56

arrived, at length, and I was speedily in the saddle. With many a silent query as to the possible changes at Cypress Shore (I had been gone three years), and whether Helen Jeffreys was single; and with now and then a laugh at my escape from my friend the professor (which degenerated into a chuckle of exultation when I imagined the surprise with which he would probably awake, and, on finding me absent, exclaim "Hewman natur!") did I steadily travel onward.

In winter, spring, or fall, which is to say in rainy seasons, it is a good three-hours' drive from Windsor to my uncle's residence. Such was the case at the time of which I speak, the twenty-ninth day of March, 1849; and my horse gave some signs of weariness as he "padded the way" in the silent shades and utter loneliness of the giant pines.

O! those Carolina roads! extending leagues on leagues, with never a crook descernible by the eye, flanked by thick-set pines that have been blazed and scarred by surveyors and tar-makers; level as a house floor, and sometimes as hard; musical at times with the hunter's horn, the hounds in full cry, or the notes of a thousand birds, thrown into fine harmonic relief by the low bass of the wind as it sweeps through the lofty pines. O! those Carolina roads! Will any one whose eye shall dwell on this page remember a gallop along their shadowy track, or through the bridle-paths and wood-roads, wherein no Mentor could have saved the bewitched Telemachus? Will any heart, I wonder, feel a throb the quicker or more pleasant at this mention of the stillness, and solitude, and deep shadows of those finest of the world's pathways? "They are always melancholy

Page 57

pleasures, those of memory," saith James; "for they are the rays of a star that has set." Even so. There are few things that waken for me more pleasant, and by'r lady! sadder recollections, than the remembrance of divers walks and rides (not to make the remotest allusion to the person or persons--isn't that lawyer-like?--with whom they were enjoyed) through the magnificent pine-forests of "the good old North State."

I am digressing. I rode but slowly, and it was near nightfall when I reached the post-office, which, I remembered, was about six miles from Colonel Smallwood's. I had passed it, and had just entered the woods again, when I heard the clatter of a cart behind me, and the sharp and somewhat urgent chirruping of the driver. Whoever he was, he was manifestly in a hurry; for I heard now and then a whack of a stout whip somewhat vigorously, not to say devoutly, administered. Thinking it not quite civil to turn my head to witness the approach of the new-comer, I reined my horse out of the road, and made him slacken his pace for the stranger to pass. On he came with a clatter that made my horse somewhat restive, and, as he rode up abreast of me, my ears were greeted with

"Human natur! Is this yaou?"

"I am laboring under the impression that it is," I replied, as coolly as I could say the words.

"Wall, ya-as! I thought it must be yaou; eenamost know'd 'twas yaou. How've you been?"

"Pretty well, I thank you; I hope you are quite well."

"Why ya-as, reasonable, I thank ye; though I had an awful time out to Edentown with the bowel-complaint."

Page 58

"I am sorry to hear it," I replied; though, forgive me, gentle reader! I wished it had been the cholera. "Good evening, sir; it's getting late, and I must ride on."

So saying, I plied my horse with a touch of the spur that nearly cost me my seat, and left my friend the professor at a round gallop. I had ridden possibly a mile at the same rate, when, on reaching the brow of a small hill, I saw my uncle's carriage and grays, and, on a nearer approach, old GRIEF, the coachman.

"Ki! Maussa Greg'ry, for sure!" exclaimed he, as he removed his hat, and gave his knee a curious slap with it.

The colonel's gray head and rosy visage now issued from one door of the carriage, and a bonnet that I was sure I had seen three years before, and which, even then, I considered a venerable relic, betokened the presence of the colonel's maiden sister, my aunt Corny, at the other.

"How you ben, Maussa Greg'ry?" roared Grief.

"Hello! Gregory, my boy! how are you? Glad to see you. Hold up, Grief! where the devil are you driving to?" shouted the colonel.

"Why bless me, Gregory! Why don't you hold the horses, Grief! I do believe they're going to run away! I'm so glad to see you, Gregory! Why didn't you write? Come this side; Molly's dying to see you."

Then followed a general and particular shaking of hands, with the more affectionate greetings to my Aunt Corny and little Molly Smallwood; this last being a curly-headed, rosy-cheeked, bewitching, mischievous, frolicking girl, and an adopted daughter of my uncle.

Page 59

"Let Andrew ride your horse," said the colonel. "Get into the carriage with us."

And Andrew came from his post behind the carriage. He took my horse, and I seated myself beside my Aunt Corny, with Molly on my knee.

"Drive home, Grief," said my uncle.

Grief had driven out of the road for the purpose of turning, and the carriage was standing crosswise in the road, when, at a short distance, I saw Professor Mathers standing upright in his cart, and endeavoring, apparently, to restrain a rickety old skeleton of a horse, then smitten with the marasmus. He had, by some means, persuaded the animal into a gallop.

"Whoa! hold on, yaou darned fool! I do b'lieve yaou'll run intew that 'ere carriage, spite of all I kin dew. Children of Is--"

This last exclamation was cut short, as, apparently, in utter despair, he reined the horse into the ditch by the roadside. Whether such were his design, I know not. He was leaning back, at an angle of forty-five degrees, in the apparent effort to stop the horse; and when the wheel ran into the ditch the cart upset, and the professor leaped from it with an agility which surprised me. He fell headlong, however. We got out of the carriage, and as we approached him, he had one knee tightly against his breast, and his arms around it in a frantic hug.

"O-h-h-h!" groaned the professor.

"Are you much hurt?" asked the colonel.

"Oh-h-h! human natur!" was the sole reply, with a moan that would have justified the administration of

Page 60

extreme unction, and which brought my Aunt Corny, trembling like a leaf, from the carriage.

"I do believe he--he--he is killed!" she exclaimed, gasping for breath. "Andrew, hitch your horse. Molly, my dear, run to the carriage, and get the mug for Andrew, and let him fill it with water. Here, my good man, smell this!" and she applied a phial of harts-horn to the professor's nostril.

"Children of Isril!" roared the injured man; and he leaped to his feet. "Thanky, ma'am; I feel quite relieved. Oh-h-h!" (Here was another groan.) "Will yew let that 'ere darky help me git my cart int' the road?"

"Most certainly," answered the colonel, whose sympathies were somewhat excited; "and, as it is now sunset, you had better drive home with me, and take a bed."

"Thank ye, kindly!" groaned the professor; "but I'm on my way to Colonel Smalley's, or Smallwood's, I b'lieve it is. Kin yaou tell me where 'bouts he ties up tew, Mr. Seaworthy?"

"So! you're acquainted, eh?" said the colonel. "Come--the boys have got your cart into the road, I see. My name is Smallwood, and I am probably the person you wish to see."

The professor accepted the invitation. We reseated ourselves in the carriage, while he mounted his cart; and in less than an hour we were seated by a cheerful fire at the old family mansion. I wish I could present to the reader the scene of that evening, as it now reappears to me. The gray-haired colonel in his huge old-fashioned arm-chair; his rosy visage yet more rosy with the light

Page 61

and heat of the genial fire; his benevolent smile betokening the temporary subjugation of his constitutional irritability. He was the ideal of your testy, choleric, impatient, yet benevolent, warm-hearted, hospitable Southern gentleman of three score. My Aunt Corny, who admitted to me in confidence, three years before, that she was "a little upwards of thirty" (the colonel declared she was forty-five), relaxed somewhat her habitual primness as she conversed with me, casting now and then a somewhat timid, uneasy, inquiring glance at the professor, and knitting away with a spasmodic activity that provoked then, as the recollection of it does now, an irresistible smile.

"You are always busy, I believe, Aunt Corny," I said to her, in one of the pauses of the conversation.

"O yes, Gregory. Since Kate has gone away to school, and Bob to college, I have taken to knitting as a pastime. Indeed, I don't know what I should do without it. Polly Feggins--you remember Polly, don't you?--proves to be such a capital housekeeper, that there is little or nothing else to do."

"What college is yer son gone tu?" inquired the professor.

"Not my son, sir; Robert Smallwood is my nephew. He is at--"

"O ya-as! 'Scuse me, ma'am; I remember now. Yew're a sister of the colonel's?"

"Yes, sir," replied Aunt Corny, nervously.

"What college did you say?"

"I was about to say that he was at Brown University."

Page 62

"And where's Miss--Kate, I think yew called her? She's your niece, I s'pose?"

"Yes, sir; Miss Kate Smallwood is my niece," replied my aunt, a little irritated by so many questions from a stranger; "she is an adopted daughter of my brother, Colonel Smallwood. She is at school at Richmond, sir."

"Oho!" replied the professor, and he relapsed into something very like a brown study. (Does anybody know, by the by, why it came to be called a brown study?) He had probably made up his mind to comply very literally with the colonel's request that he would "consider himself at home;" for he drew his chair nearer the fire, pulled off his boots, and thrust his feet far inside the fender, within a very dangerous proximity to the fire. He then managed, how I know not, to coax Molly to his side, and then to seat her upon his knee, pouring forth, meanwhile, whole encyclopedias of nursery rhymes, which kept her in high glee until bedtime. I could see that my Aunt Corny's heart was warming towards the awkward and uncouth but kind-hearted professor; and I was well nigh ready, on my own part, to forgive the burr-like tenacity with which he had clung to me. Grief, I could see, was delighted with him, even while he grinned at his oddities; and the old colonel's face expanded into a genial smile, far beyond the strict limits of etiquette, as little Molly pulled forth from the professor's vest pocket a huge old-fashioned watch, so big that she could scarcely grasp it with both hands.