Cotton Mill, Commercial Features.

A Text-Book for the Use of Textile Schools and Investors.

With Tables Showing Cost of Machinery and Equipments for

Mills Making Cotton Yarns and Plain Cotton Cloths:

Electronic Edition.

Tompkins, Daniel Augustus, 1851-1914

Funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Tampathia Evans

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Melissa G. Meeks and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2001

ca. 700 K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) Cotton Mill, Commercial Features. A Text-Book for the Use of Textile Schools and Investors. With Tables Showing Cost of Machinery and Equipments for Mills Making Cotton Yarns and Plain Cotton Cloths.

(cover) Cotton Mill, Commercial Features

(spine) Cotton Mill, Commercial Features

(appendix) Appendix. Essays on Domestic Industry, or An Inquiry into the Expediency of Establishing Cotton Manufactures in South Carolina. Written by William Gregg, of Edgefield District, South Carolina in 1845. [p. 203-240]

D. A. Tompkins

viii, 1-240, [6] p. : ill., plates

CHARLOTTE, N. C.

PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR.

1899.

Call number C677 T66co c.2 (North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 24th edition, 2001

Languages Used:

- English

- Cotton manufacture -- Southern States.

- Cotton textile industry -- Southern States.

- Textile factories -- Southern States.

Revision History:

- 2002-08-19,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-10-24,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-05-01,

Melissa Graham

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-04-17,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

[Spine Image]

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

COTTON MILL,

COMMERCIAL FEATURES.

A Text-Book

FOR THE USE OF TEXTILE SCHOOLS AND INVESTORS.

With Tables

SHOWING COST OF MACHINERY AND EQUIPMENTS FOR MILLS MAKING

COTTON YARNS AND PLAIN COTTON CLOTHS.

By

D. A. TOMPKINS.

CHARLOTTE, N. C.

PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR.

1899.

Page verso

COPYRIGHT 1899

BY

D. A. TOMPKINS.

Presses Observer Printing House,

Charlotte, N. C.

Page iii

TO THE MEMORY OF MY FATHER,

DR. D. C. TOMPKINS,

THIS VOLUME IS AFFECTIONATELY DEDICATED.

Page v

Preface.

Before the institution of slavery became fixed as the leading feature of the labor system in the cotton growing area of the United States, the manufacturing interests in this area prospered more than in any other part of the country. As the production of cotton with slave labor was found to be more profitable and attractive, the institution of slavery grew in magnitude and importance, while manufacturing interests were neglected and allowed to languish.

The abolition of slavery, as a result of the Civil War, completely upset the system of labor previously in vogue. The former condition had become a semi-feudal one, with such modifications as modern civilization made necessary.

The abolitionists went far past the point of reasonable good judgment. The slaves were all Africans, or of African descent. Some of the most recently imported ones were trained from a savage condition, and all of them were without education or training, except for work on a plantation. These were at once given the right of suffrage and full rights of citizenship, on terms of equality with their former owners. This brought about a condition of semi-anarchy, in which the energy of the Anglo-Saxon element was sorely taxed to maintain their social supremacy and civilizing influence. Nothing prospered during the quarter of a century through which this lasted. Promptly, however, upon the restoration of stable government, a revival of manufactures commenced, which has grown steadily, and is still growing.

In my work as engineer, I have had so many inquiries from people, living in the cotton growing area, for "full information about the cotton manufacturing business," that I have prepared this book to supply, to some fair extent, the data, and such discussion of the same as, I hope, will give a good general idea of the subject.

D. A. TOMPKINS.

Charlotte, N. C., October 15, 1899.

Page vi

Contents.

- CHAPTER I.

COTTON AS A FACTOR IN PROGRESS.--

The Cotton Gin. Old Gin House. Improved Gin House. Increase in Cotton Planting. Value of seed. - CHAPTER II.

VALUES IN COTTON.--

Cotton Monopoly. Foreign Crops. How to Increase Profits in Cotton Growing. Prosperity of Manufacturing Communities. Overproduction. - CHAPTER III.

ORGANIZATION OF COMPANY.--

Subscription List. By-Laws. Salaries. - CHAPTER IV.

LOCATION AND SURROUNDINGS.--

Water Supply. Raw Material. Labor. - CHAPTER V.

RAISING CAPITAL.--

The Installment Plan. By-Laws. Foreign Capital. - CHAPTER VI.

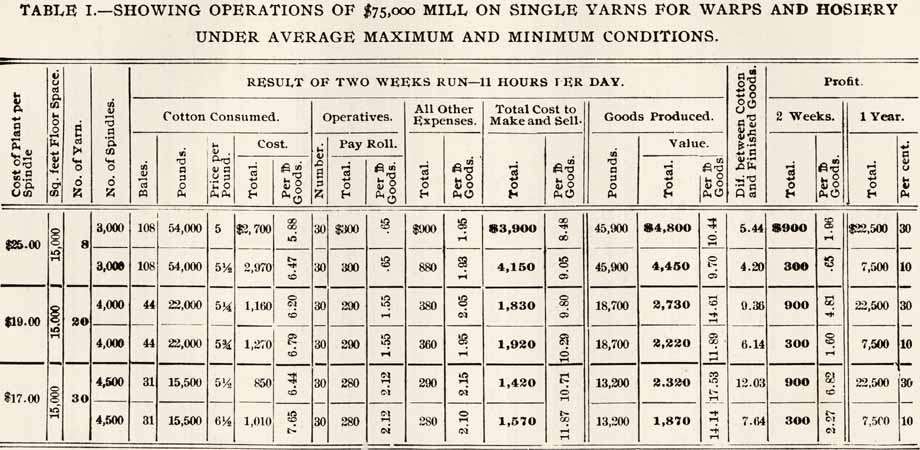

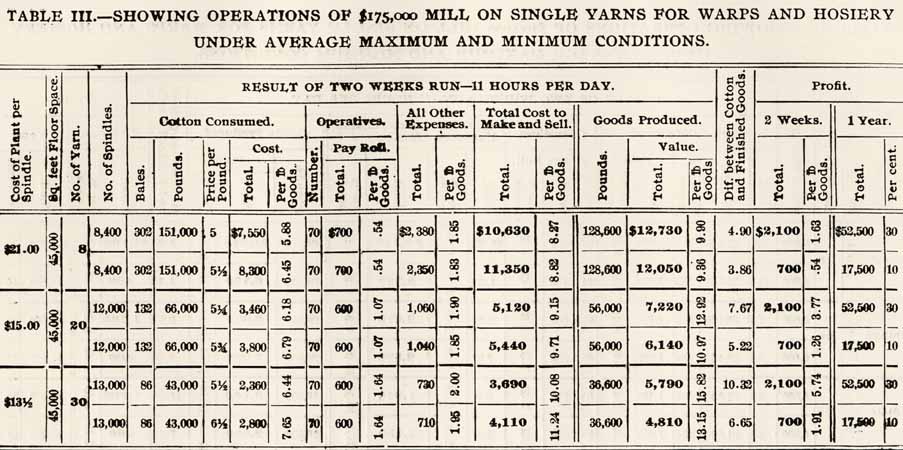

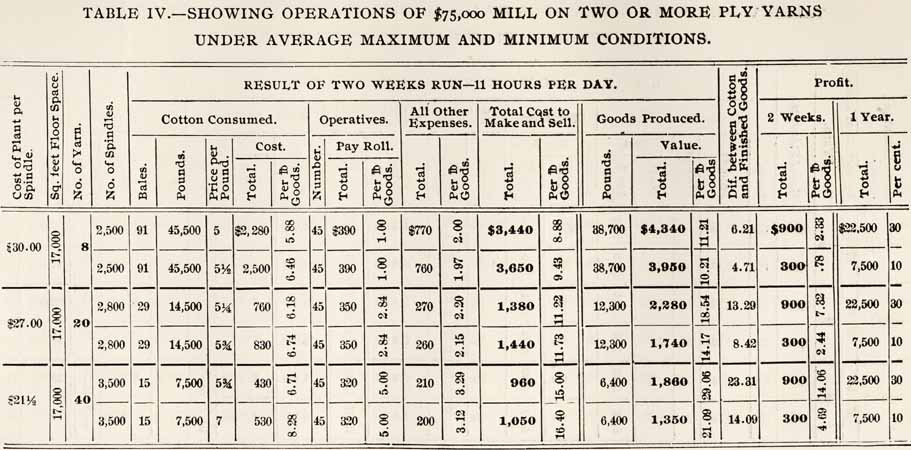

INVESTMENTS, COSTS, PROFITS.--

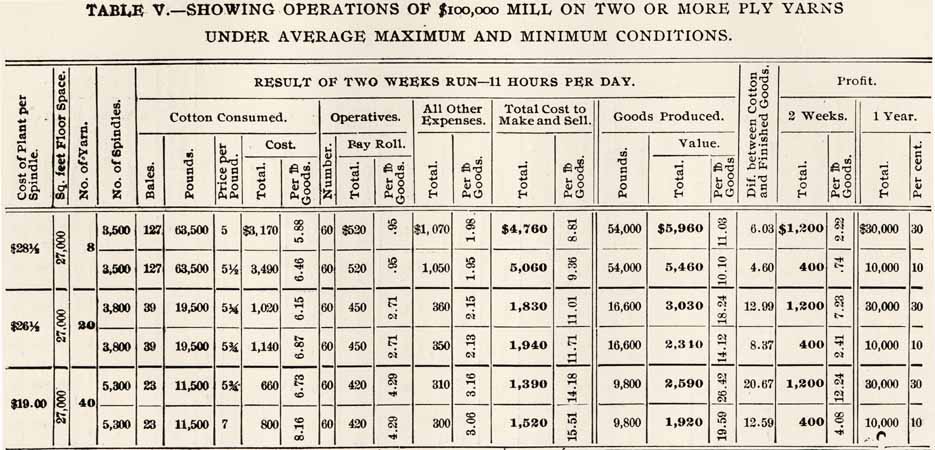

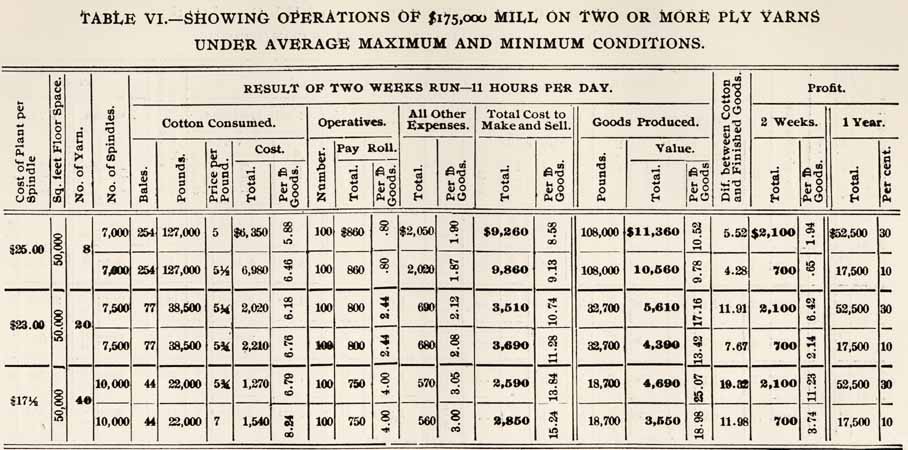

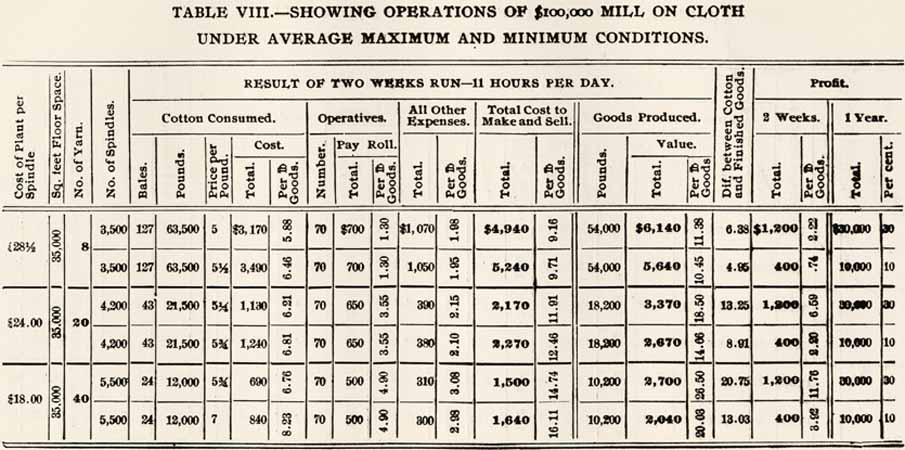

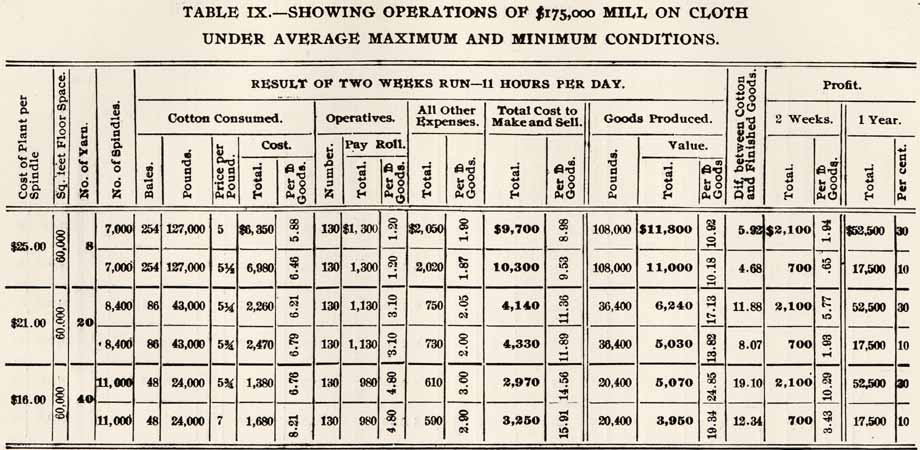

First Cost of Various Size Mills. Cost of Operation. Output. Labor Required. Cotton Consumed. Profits. Tables Showing Result of Operations on Different Kinds of Goods.

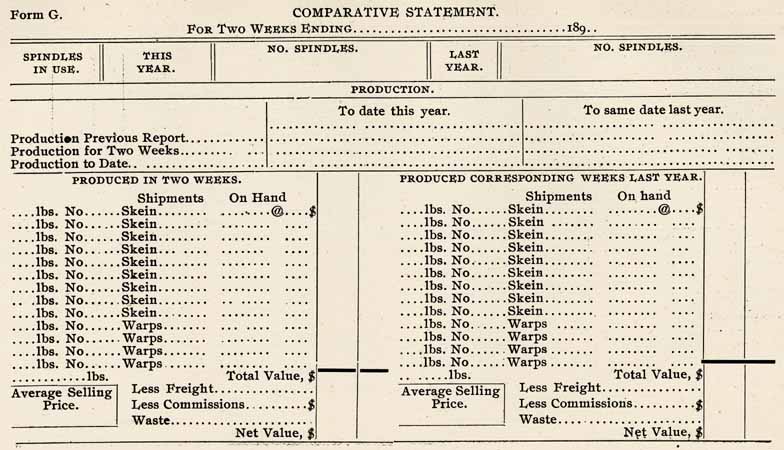

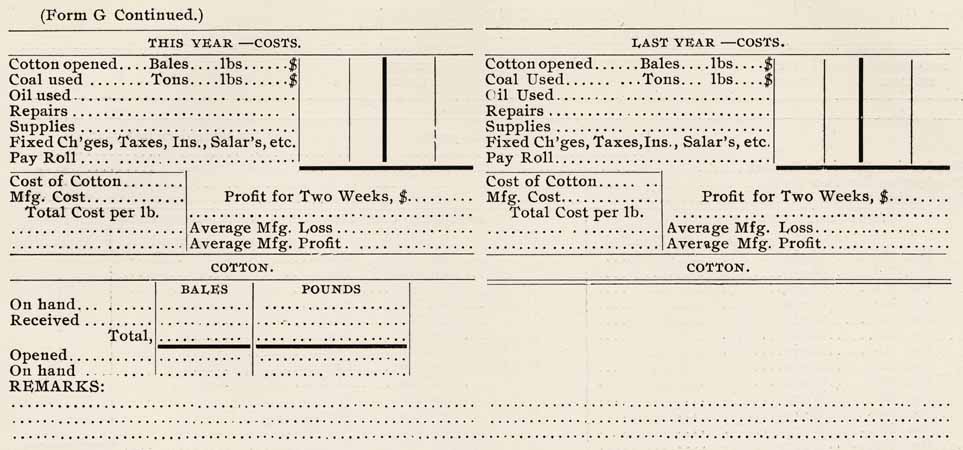

Page vii - CHAPTER VII.

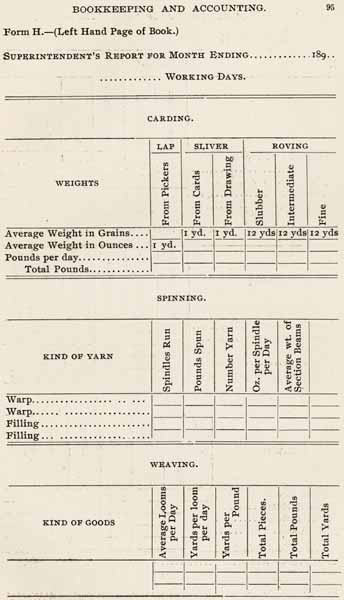

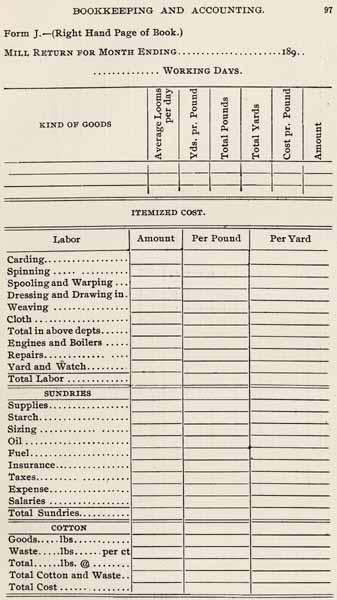

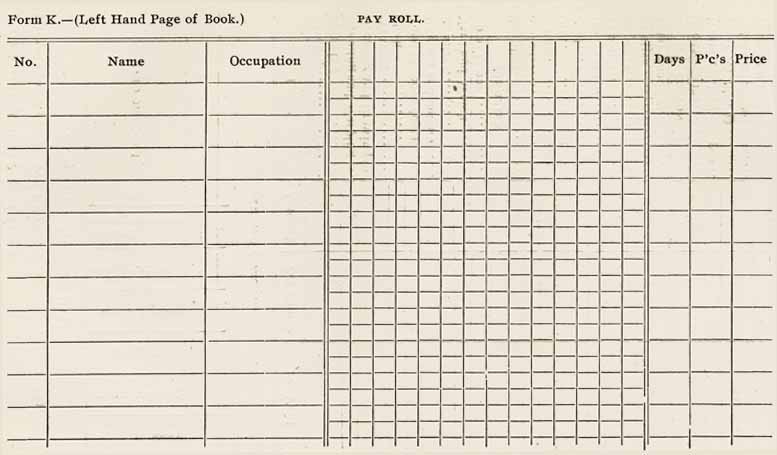

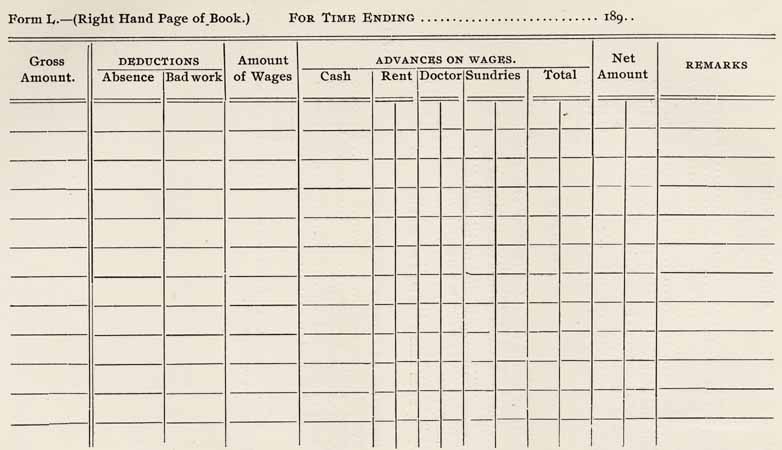

BOOK-KEEPING AND ACCOUNTING.--

Mill Book-Keeping Compared with Mercantile Book-Keeping. Two Different Series of Books. Grouping of Accounts. Mill Reports. Monthly Financial Statements. Annual Statements. Depreciation. Surplus. Blank Forms. - CHAPTER VIII.

LABOR.--

White and Colored Operatives. Labor Laws. Church and School. - CHAPTER IX.

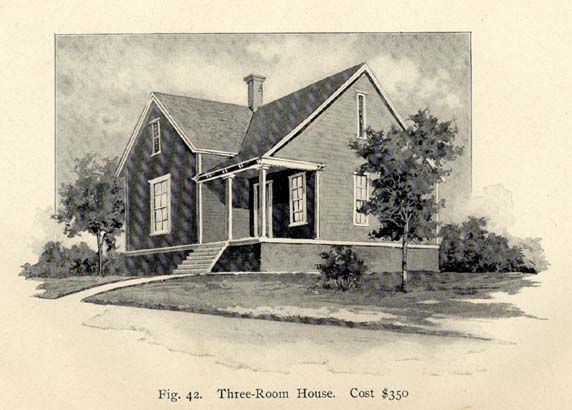

OPERATIVES HOMES.--

New Designs. Specifications for Modern Cottages. - CHAPTER X.

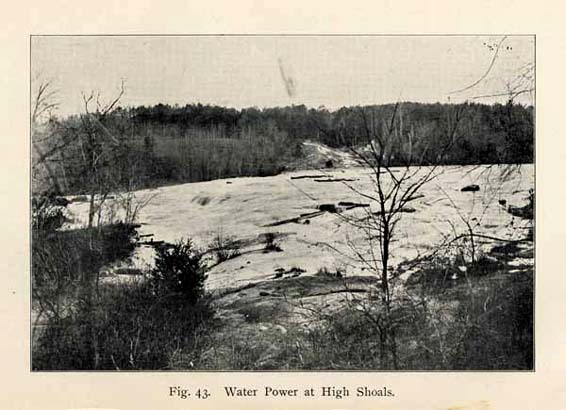

POWER.--

Relative Cost of Steam and Water Power. Water required. Fuel required. Wood Compared with Coal. Electric Transmission of Power. - CHAPTER XI.

SALE OF PRODUCTS.--

Commission Houses. Commissions Discounts. Reclamations. Freight Charges. Blank Forms. - CHAPTER XII.

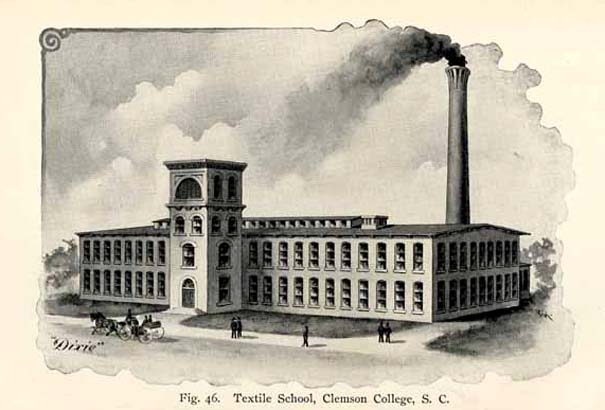

TEXTILE EDUCATION.--

Foreign Methods. Technical Education in Other Lines. Courses of Study.

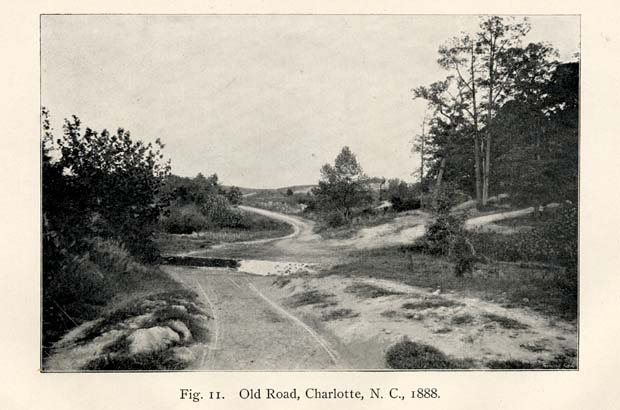

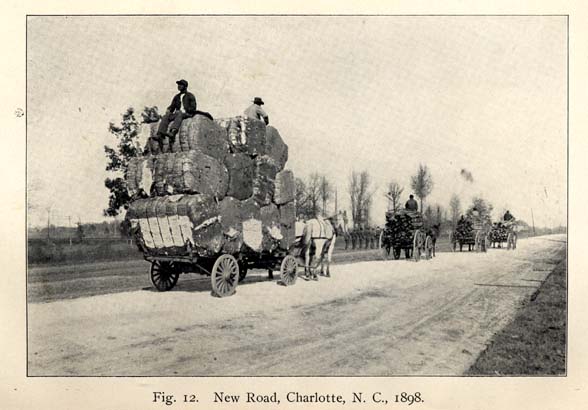

Page viii - CHAPTER XIII.

ROAD BUILDING AND BROAD TIRES.--

Good Roads Follow Mill Building. How to Build Roads. Relation of Vehicle to Road. Roads in Mecklenburg County, N. C. Convict Labor. Cost of Road Building. Cost of Repairs. Government Tests. - CHAPTER XIV.

MISCELLANEOUS.--

Insurance and Fire Protection. Standard Equipments. Mill Construction. Warehouses. Lighting. Heating. Plumbing. Humidifying. Size of Buildings. Horse Power Required. Profits. Mill Management. - CHAPTER XV.

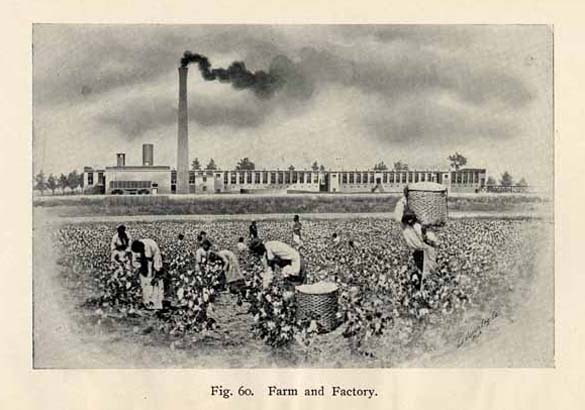

FARM AND FACTORY.--

Cotton Manufacturing as an Aid to Agriculture. Markets Made for Farm Produce by Factory Operatives. Food Crops Made Saleable. Cotton a Surplus Crop. - CHAPTER XVI.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES.-- - CHAPTER XVII.

STATISTICAL TABLES AND NOTES.-- - APPENDIX.

ESSAYS ON DOMESTIC INDUSTRY.--

Written in 1845, by William Gregg, of South Carolina

Page 1

CHAPTER I.

Cotton as a factor in progress.

The development of the production of cotton in the Southern States within a single century, from insignificant proportions to 11,000,000 bales a year, considered in all its relations to our industrial progress, is without a parallel in history. First of all, it is a sufficient answer to the charge so often made against the South that its people are without enterprise or mechanical ingenuity. It may not be going too far to assert that everything the northern part of the Union has accomplished, put together, has not affected the welfare of so many people in the world or reached so far in its effects as the development of this industry in the South.

It may be answered. "The South is the only section of this country adapted to the production of cotton; if it would grow as well in the North, a different showing might have been made by that section." But cotton grows in India, in Egypt, in China, and in South America. Therefore it may be truly said that a people cannot be without enterprise, who, in competition with such a wide-spread cotton area,--in many parts of which the plant has been cultivated for several centuries--in less than one hundred years, are able to show a production far exceeding that of all the rest of the world.

In 1820, the cotton crop of the United States amounted to about 400,000 bales; in 1892, the yield reached nearly 9,000,000 bales. During the greater part of this interval of 72 years, the price has ranged from ten to twelve cents per pound. But sometimes the price has been as low as five cents, and as high as twenty-seven cents, leaving out of account the years of the war (1860 to 1864.) when the South practically ceased cotton production. Estimating 500 pounds to the bale, and the price at ten cents per pound, the crop of 1820 was worth, in round numbers, $20,000,000. On the same basis, the

Page 2

crop of 1892 was worth $450,000,000. This great increase in cotton production has been made in a section to which there has been no such constant tide of immigration as has been experienced by other parts of the United States, and, for this reason alone, the result reflects great credit upon the native population which has accomplished it.

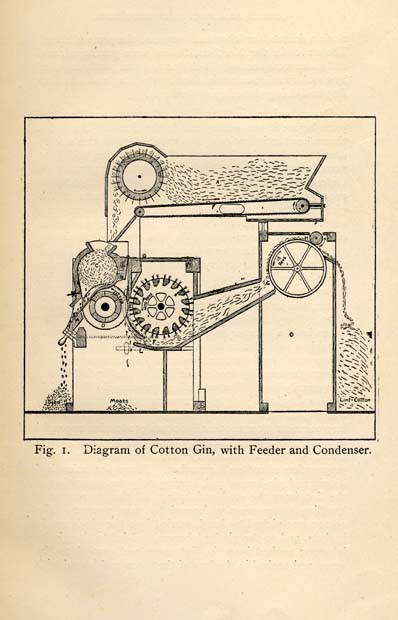

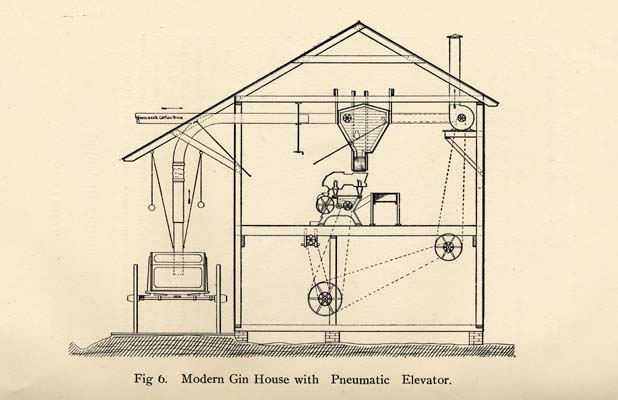

This wonderful achievement is the result of three things combined, namely: (1) the enterprise and energy of the people; (2) the invention of the cotton-gin; and (3) the designing of buildings and mechanical appliances by which the gin may be economically operated.

The Cotton Gin.

It seems to be the generally accepted opinion that the successful production of large cotton crops in the United States is due to the invention of the gin alone. While this has been an essential element in the problem, yet Egypt, India, and South America, which also have the advantages of perfected gins, due to the inventions made in America, produce cotton neither so cheaply nor in such large quantities as it is produced in the Southern States.

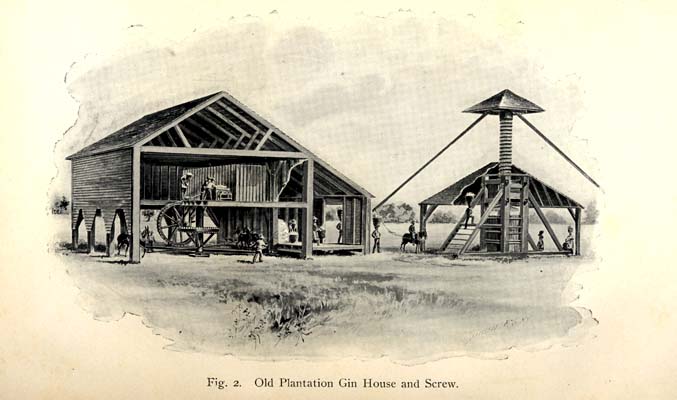

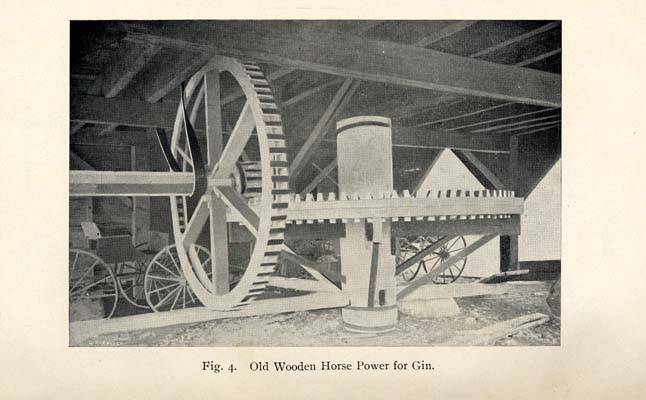

A machine having been invented that would separate the lint from the seed, there was need at once for a suitable house in which to operate it, and some power to drive it. Mule-power was the most available, and wood was the most suitable material, both for the building and for the machinery to be employed in utilizing the power. Therefore, a series of wooden wheels, gears, and levers were devised by someone whose name is now lost. The house was built on posts in such a way that the machinery could be operated by mules underneath it. Considering the limited facilities at hand, this running-gear for the utilization of mule-power exhibited marked mechanical ingenuity and adaptability, the lack of which, in other countries, prevented such results in the production of cotton as were attained here in ante-bellum days.

When the gin, the gin-house with its appliances, and the baling-screw had all been developed to a condition of practical success, the production of cotton then became very profitable. The desire to embark in the business

Page 3

Fig. 1. Diagram of Cotton Gin, with Feeder and Condenser.

Page 4

made a demand for labor and increased the price of slaves. The slaves in the Northern States were purchased, and still more were needed, which demand was partly supplied by the African slave trade, the ships of England and New England doing the carrying business.

Slavery existed in New England about one hundred years before it was widespread in the South. Up to the time when the inventions just described gave such a stimulus to cotton planting, general manufactures had prospered more in the South than in any other part of the Union. As late as 1810, according to the United States census for that year, the manufactured products of Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia exceeded in variety and value those of all New England. While the production of cotton remained profitable, the growth of slavery gradually stifled Southern manufacturing interests. And as another result of slavery no further improvements were made in the appliances and the methods of preparing cotton for market. The standard ante-bellum gin, gin-house, and screw were practically the same in 1860 as in 1820. Many of those of 1860 were larger and finer than those built a quarter of a century earlier, but there was scarcely a new idea in the design. During this period of forty years the inheritor of slaves had become an aristocrat; the cunning mechanical skill of his forefather was temporarily lost. But, while lost temporarily, it lived in the bones of the people, because no sooner had the late war ended, wiping slavery out of existence, than one improvement after another in cotton production appeared in rapid succession. Before the war mule-power, slave-labor, and wooden machinery were in universal use for the preparation of cotton for market. Every plantation had its gin and gin-house, and, barring only the separation of the lint from the seed and baling, all the operations in handling cotton were performed by man power. The cotton was picked by hand, carried into the gin-house in baskets, and to the gin by laborers, and fed to the gin by laborers; pushed into the lint room and carried to the screw and packed in the box of the screw and bound with

Fig. 2. Old Plantation Gin House and Screw.

Page 5

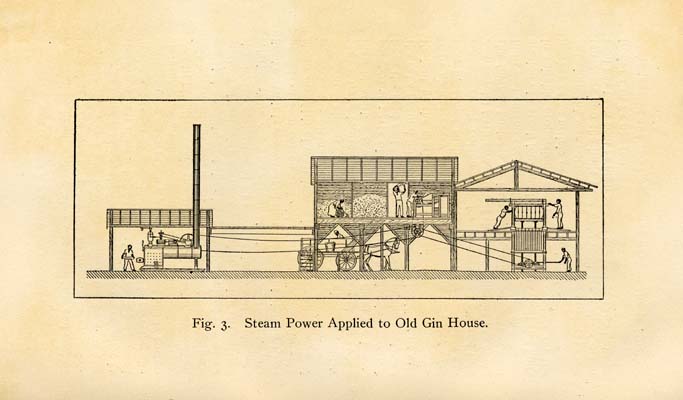

Fig. 3. Steam Power Applied to Old Gin House.

Page 6

ropes, all by hand. Slave-labor was abundant and cost so little that there was no incentive to improvement.

After the war a gin feeder was invented to save the labor of hand feeding; then a condenser, to save labor in the lint room; then a hand-press that could be operated in the lint-room of the gin-house, to save carrying the cotton to the screw; then a power press, and finally cotton elevators, some using spiked belts and some air suction.

Within thirty years the spirit of enterprise, invention, and improvement has again taken possession of the people of the South, and they have revolutionized the whole method of preparing cotton for market, giving their attention to the perfection of all the machinery and appliances relating thereto. The extent of this progress may be realized when it is remembered that the cost of ginning 1,500 pounds of seed cotton and of baling the lint is now only about one-fifth of what it was in 1870. In the march of progress the plantation gin-house and screw have been supplanted almost entirely by the modern ginneries, which are centrally located and are manufacturing plants rather than plantation equipments. Many of them are incorporated as parts of plants in which the lint is separated from the seed and baled, the oil taken from the seed, and the cake ground into meal to be used as fertilizer or cattle-feed, as the markets may demand.

In almost every community in the South there may now be found such manufacturing plants. These gin cotton, crush cotton-seed for cotton-seed oil, and mix commercial fertilizers. Out of this development has come the further business of fattening cattle on cotton-seed hulls and cotton-seed meal at the plants, and the preparation of a stock food made by mixing the meal and hulls in suitable proportions and putting the product on the market as an article of general merchandise.

Before the war cotton seed was a waste product; even ten years ago the hulls were only used for fuel. Cotton seed has sold as high as $20 per ton and the hulls at from $3 to $5 per ton.

At present the most expensive item in the production

Fig. 4. Old Wooden Horse Power for Gin.

Page 7

of cotton is the cost of picking the raw cotton from the stalks in the field. The exercise of ingenuity looking toward lessening this heavy expense has not been neglected. During the last few years, numerous patents have been issued for cotton-harvesters, many of which are absolutely without merit, but some of which are marvelously ingenious. One that seems, so far, to have come nearest to doing commercially successful work is that of Mr. C. T. Mason, of South Carolina. The incentive to the solution of this problem may be seen from the following estimate:

The price now paid for picking raw cotton from the field is from 50 to 75 cents per hundred pounds. About 1,500 pounds of seed cotton are required to make a bale of lint weighing 500 pounds. The cost of gathering 1,500 pounds of cotton at, say 60 cents per hundred, is $9. Therefore to gather ten million bales will cost, at present prices, $90,000,000. It is claimed by the cotton-harvester inventors that a machine can be made which will gather 4,000 pounds of seed cotton per day, with the aid of one laborer and one mule, whereas the gathering of 150 to 200 pounds by hand is now a day's work for one man.

The Growth of the Industry.

The following table will give some idea of the increase, as well as some idea of the increased value of the crop since 1820. Values are all based on the rate of 10 cents per pound, and an average weight per bale of 500 pounds. The estimates are given in round numbers.

| Year. | Production in Bales. | Value at 10 cts per Pound. |

| 1820 | 400,000 | $ 20,000,000 |

| 1840 | 1,600,000 | 80,000,000 |

| 1850 | 2,250,000 | 112,500,000 |

| 1860 | 3,600,000 | 180,000,000 |

| 1870 | 3,000,000 | 150,000,000 |

| 1880 | 6,600,000 | 330,000,000 |

| 1890 | 8,000,000 | 400,000,000 |

As has already been said, cotton seed was formerly a waste product, except where used in the Southeast to a

Page 8

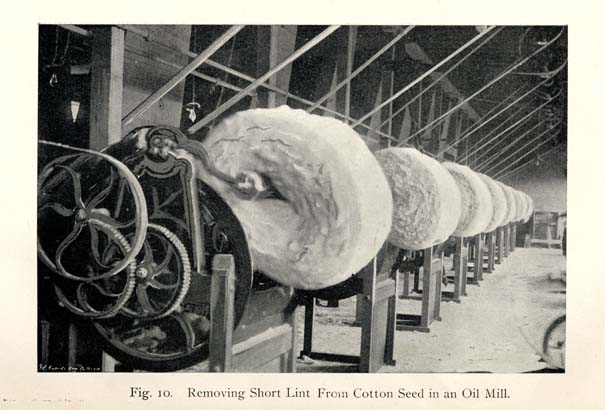

limited extent as a fertilizer. Since the war the cotton seed oil business has been developed to such an extent that in an average season, about 1,500,000 tons of seed will be crushed for oil and other products. Out of these seed will come the following products, against which their values are shown:

| 60,000.000 gallons cotton oil @ $ 0.25 | $15,000,000 |

| 700.000 tons hulls @ 4.00 | 2,800,000 |

| 500,000 tons meal @ 20.00 | 10,000,000 |

| 50,000,000 pounds short lint @ .02 | 1,000,000 |

| Total | $28,800,000 |

This vast sum of money comes out of what was, in the days of slavery, almost entirely wasted.

But it is not alone in the utilization of cotton seed that the revived mechanical genius of the South is being shown, but in the manufacture of cotton into yarns and cloth as well. In a region of country reaching along the foothills of the mountains from Lynchburg in Virginia, to Atlanta, in Georgia, almost every town has one or more cotton factories, all built since the war. Many factories have been built on the water powers in the country, and towns have grown up around them. At first only coarse goods were attempted; then finer and still finer products in succession. While as yet no very fine goods have been produced, enough has been done to prove that, as capital accumulates and the owners acquire an increased knowledge of the business and the operatives improve in skill, there is no more limit to the quality of the goods that may be made about Charlotte, North Carolina, than those that may be made about Lowell, Massachusetts, or Manchester. England.

And there is still another thought suggested by a study of general economic progress. The present industrial development in America, in England, and on the continent had its beginnings in four events, the absence of any one of which would have made present industrial conditions impossible. These were the invention of the power-spindle, the inventon of the power-loom, the invention of the cotton-gin, and the response to these by the southern

Page 9

Fig. 5. Improved Gin House for Steam Power.

Page 10

portion of the United States in the production of the raw material for the utilization of these inventions.

It is not alone of interest that the impetus given to the production of cotton by mechanical inventions has added to the productive capacity of Southern agriculture and increased the wealth of an important section of the United States. Every family in the whole country has been benefitted by the cheapening of clothing and other articles made of cotton, by reason of the marvelous increase in the production of this Southern crop. The manufacturing and commercial interests of New England have been promoted to a remarkable extent by the same cause, to say nothing of the effect upon the cotton manufacturing interests in England and in other parts of the world. The increase in the consumption of cotton goods due to the wonderful cheapening of their cost, is another result of the increased cotton crop of the South, while the benefit to all shipping interests due to the cotton carrying trade is still another result. That cotton, more than any other one item of freight, has been the basis of transatlantic commerce, is well known.

Leaving aside such general benefits, at home and abroad, accruing to the industry and to the commerce, and to the comfort of the human race from the increased cotton production of the South, we may again refer to the importance, to this section of the cotton growing industry. Cotton as a basis of wealth and of productive industry has made possible the growth of prosperous cities and towns where, at least before the development of the mineral resources of the South, nothing of the kind could have existed. The cotton industry has contributed to the success of all transportation systems in our borders. Even the development of Southern coal and iron mines has been hastened by the need of iron by railroad companies for the transportation of the cotton and in the manufacture of cotton machinery, and the need of coal for purposes to which cotton has given rise. The cotton-growing industry, in short, has furnished what opportunity has existed in this large portion of the Union for the employment of engineering and mechanical skill, contributing thus to every branch of material progress.

Page 11

Fig. 6. Modern Gin House with Pneumatic Elevator.

Page 12

CHAPTER II.

Values in Cotton.

A careful study of past events in connection with the development of cotton production, together with a study of the conditions surrounding the present state of the industry, should promote a knowledge of the subject that will be of infinite advantage in showing what is the best course for the American cotton producer to pursue in the future.

It would be of great advantage for the present generation to know in what way the most money can be made out of the cotton crop. Constantly increasing production, constantly lowering prices, increasing cost of labor, doubt as to the extent to which the negro will continue as a valuable laborer on the farm, the extent to which white labor is being attracted from the cultivation of cotton to occupations in its manufacture, markets for increased production of goods, the questionable future of the negro; all these, and other changing conditions, makes it important to review carefully the past, study assiduously the present conditions, and upon the basis of facts determine, with discretion, in what direction to move for the preservation of that practical monopoly in the production of cotton now enjoyed by the United States, for the betterment of the condition of those engaged in it and for the general interests of the people at large.

Commencing in 1790 with a crop of 5,000 bales, the production of cotton has continually increased in the United States, reaching in 1898 more than 10,000,000 bales.

In the same period the price has gone from about 25 cents a pound to about 6 cents a pound.

Fig. 7. Old Slaves and Their Cabin.

Page 13

Cotton Monopoly.

Before the civil war and the abolition of slavery, the monopoly of the production of cotton by the United States for the larger markets was well nigh complete. This statement omits of course consideration of cotton raised in various countries for hand spinning and weaving and other home uses.

Since the civil war in the United States, by which slavery was abolished, India and Egypt, under English direction, have developed a growing interest in the production and export of cotton. A considerable cotton manufacturing interest has also been developed in India, mostly with English capital and under English management.

| *In 1869-'70 the American crop was | 3,122,000 bales. |

| In 1869-'70 the India crop was | 1,985,000 bales. |

| In 1880-'81 the American crop was | 6,605,000 bales. |

| In 1880-'81 the India crop was | 2,093,000 bales. |

| In 1890-'91 the American crop was | 8,650,000 bales. |

| In 1890-'91 the India crop was | 3,225,000 bales. |

* Figures reduced to round numbers are from "The Cotton Plant," published by the United States Government under direction of Chas. Dabney.

Since 1890 the India crop has remained very nearly the same. The check to its continued growth, however, has only been accomplished by an increase of production to ten and eleven million bales in the United States, while at the same time the price has declined to five cents.

It will be observed that the India crop of 1890-'91 is about the same as the American crop was for 1869-'70. It has required constant increase in production, and constant reduction in price, for the production and prices of the United States to check the encroachments of India upon cotton trade formerly controlled almost exclusively by this country.

The conditions brought about by this competition are not satisfactory to the cotton farmer of the United States. Cotton at 5 cents a pound does not bring a satisfactory

Page 14

income. The contemplation of large crops and low prices under average past conditions give scant encouragement to the cotton farmer for the future.

Yet in view of the increasing crops of India and Egypt it is evident that if the world wants more cotton, the demand will be met and without any very great increase in price.

The preceding figures in relation to the American and Indian crop show that, even with present quantities and at present prices prevailing in the United States, India could and would produce more cotton if the crop should be curtailed in this country.

The exports of cotton from Egypt to Europe and the United Kingdom are as follows (round numbers):

- In 1875, 347,000 bales.

- In 1880, 456,000 bales.

- In 1885, 500,000 bales.

- In 1891, 538,000 bales.

- In 1895, 634,000 bales.

From these figures it will be seen that the large production attained and the low prices reached in the United States do not stop the increase of production in Egypt. On the contrary, Egypt has made some headway in shipping cotton into the United States, the extent of which will be shown by the following figures:

- In 1885, 3,815 bales.

- In 1890, 23,790 bales.

- In 1895, 59,418 bales.

In other countries, also, progress is being made. Therefore, it would appear that in time the less enterprising people of the world learn American methods and then apply them where fairly favorable conditions and cheap labor can be found.

The ante-bellum planter, with slave labor, did a wonderful work in creating methods and means for producing a raw material that went far to take the place of wool and linen, and at a price to put a good material for clothing within the reach of all humanity.

Fig. 8. Cotton Bales as Brought to the Compress.

Page 15

The post-bellum farmer has done equally well if not better in forging ahead in the production of larger quantities, as the world's demand increased, and at prices sufficiently lower to fairly well preserve the monopoly.

Many factors have entered into the economies from year to year to keep the cost of cotton down below the market price. It formerly cost $5 a bale to gin and bale cotton. By improved methods it now costs less than $1 in most parts of the cotton belt.

The seed was formerly a waste product in some sections, and of but scant value as a fertilizer in other sections. But now cotton seed has become the raw material for a valuable and prosperous industry, cotton seed oil milling.

Factories for the manufacture of commercial fertilizers have been established, by which means very excellent fertilizers at very cheap prices are available wherever they are needed.

States have founded agricultural Colleges, Boards of Agriculture, Inspectors of Fertilizers, Agricultural Experiment Stations, and have in many other ways contributed to the acquisition and distribution of knowledge of better methods and closer economies in producing cotton.

Decreasing Profits in Producing Cotton.

With the advantage of all these, the condition of the cotton farmer is not a satisfactory one. The following figures, showing approximate crops and their values, all in round numbers, will illustrate the disadvantages that changing conditions impose upon the farmer:

- Crop of 1871--4,250,000 bales @ 17c $361,250,000.

- Crop of 1880--5,750,000 bales @ 12c 345,000,000.

- Crop of 1886--6,500,000 bales@ 9½c 308,750,000.

- Crop of 1895--9,500,000 bales @ 6½c 308,750,000.

From the above, it will be seen that the crop of 1895, while about double that of 1871, only yields about the same money. It must not be forgotten, however, that the cost of production has been much decreased in the same time, and that the developing cotton seed oil business

Page 16

has given a value to by products of the crop, and that the value of money is greater now than it was in 1871 because of the lowering of the prices of all other products (or the appreciation of money whichever way it may be called.) The appearance of furnishing twice the cotton therefore for the same value is not correct.

Better knowledge and further economies may of course be introduced. Education may be improved and extended. Fertilizers will be more abundantly made, and sold cheaper. Experiment stations will develop and disseminate a knowledge of better methods. Better and cheaper methods of preparing cotton for the markets will be invented and introduced.

But with all these, the problem is still a serious one. Assume that 5 cents per pound is now the cost of producing cotton. To reduce the cost of production to four cents would be a saving of 20 per cent. But assuming that our schools, experiment stations, fertilizer inspectors and all other co-operating influences be kept at work, a saving of 1 cent per pound, or 20 per cent. of the cost, is going to be hard to reach.

It would seem that the States and the people have been diligent and studious in finding out and applying well developed knowledge and new methods to keep down the cost of cotton production. Statistics from other countries show that without this constant improvement and lowering of prices here, those other countries would have taken a large proportion of the cotton trade which we yet control.

It is evident that all the talk about curtailment of production and increase of price can never lead to any good results. If such a policy could possibly be adopted, the beneficial effects could only be felt during the one or two years in which the advanced price would certainly stimulate, to the normal requirements of the world, the production in other countries, at very little if any better than present prices.

Fig. 9. Combined Cotton Seed Oil Mill, Fertilizer Factory and Ginnery.

Page 17

How to Increase Profits in Cotton Growing.

The future prosperity of the American cotton producer lies in the development of the manufacture of the staple at home. By this means the farmer would not only get a better price for his cotton, but the markets created for other farm products which are not now salable, would go far to make a surplus and profitable cash income without curtailing the production of cotton. It is well known that the average cotton farmer has ample time to spare. With a manufacturing population to take his perishable food crops he could raise as much cotton as usual and sell chickens, eggs, fruits, vegetables, meat, wood, and other things required by factory operatives to an extent to bring as much cash income as the value of his cotton crop, thus doubling his gross income from the same farm. Some more work would be required, but it would be pleasant work. The new income would be one that would extend over the entire year, and would yield most cash in spring and summer when the cotton farmer is needing it the most.

The advantages of home manufacture may be illustrated by figures as follows:

Take an ordinary county producing 10,000 bales of cotton; then

- 10,000 bales sold in bales @ 6c=$300,000.

- 10,000 bales sold as cloth @ 18c=900.000.

This would make a profit of $600.000 to the county.

Assume that this cloth was shipped to China instead of shipping the raw cotton to England and it becomes evident that the English cotton buyer sends here $300,000 while the Chinaman would send $900,000. This $600,000.00 additional would be distributed about as follows in the county.

- To stockholders of the Factories, say . . . . . . $100.000

- To Operatives . . . . . . 300.000

- To Fuel and Supplies . . . . . . 100.000

- To Miscellaneous . . . . . . 100.000

About half the money paid to operatives would go to

Page 18

farmers for foodstuffs. About one third to merchants. Some would be saved.

The above basis of 18c a pound for cloth is fixed upon as a fair average of the selling price for the kinds of cloth now being made in North Carolina.

Finer cloths would show a correspondingly better advantage.

In order to show how this operates, a bolt of cotton cloth--summer dress goods--was taken from the stock of a country merchant and weighed up. According to the price charged per yard--and it was considered cheap--that cotton cloth sold for 50 cents per pound. Another similar bolt sold at the rate of 64 cents per pound. This was in a North Carolina town, the county seat of a county making 10,000 bales of cotton.

It is possible that the cotton from which this very cloth was made, went away from the county at 5c per pound and came back at 50 or 64 cents per pound.

In other words, if a farmer's wife or daughter bought this cloth for a dress, it might easily happen that the farmers crop of ten bales of cotton might have been sold for 300 dollars, and a portion of it bought back by his wife at the rate of $3,000.00 or ten times its original value.

And it is a question whether the labor of turning cotton into cloth was as much as that of producing the cotton. The matter of making the cloth is one of creating the facilities and of knowing how to do it. As a proof that the advantage lies with the manufacturer, it is only necessary to visit a town in the cotton belt having good agricultural surroundings but no manufactures, and then visit a cotton manufacturing centre, in or out of the cotton belt.

Prosperity of Manufacturing Towns.

In the former the conspicuous elements are unpainted houses, idle people on the streets, a want of public improvement, besides many other similar deficiencies. In the latter, the streets are paved, the people are alert, houses are in good repair and painted; and all evidences

Fig. 10. Removing Short Lint From Cotton Seed in an Oil Mill.

Page 19

go to show the value to a people of making cotton worth more than 6c. a pound before sending it away from home.

While the figures show that the manufacture of cotton enriches a country, there is never any certainty that any one person or any one mill will get rich or even make money. With the increased income to a country on manufactured cotton over and above raw cotton, everybody ought to live better, and everybody certainly has the chance to make a better living, and even accumulate property if they work and are thrifty and economical.

The opportunity to accumulate property and get rich is within the reach of all wherever successful manufacturing is done; but it is not the nature of all people to save money, even when they make it.

Property in any community always benefits the whole people as well as those who accumulate property.

The roads are better, public buildings are better, streets and pavements are better, schools, libraries, churches, art galleries and all other things that go to make up human life are better. In peace or in war it is the prosperous country that is most successful and whose people are most independent. The best prosperity in peace and the greatest strength in war belong to the manufacturing people of the world.

As an evidence of the change that the introduction of manufactures makes in a town or city, notice the contrast between the public buildings of Charlotte, N. C., in 1888 and in 1898.

The possibilities for multiplying wealth and keeping money in circulation at home are startling from their very magnitude.

Figuring the American crop at ten million bales, we would have:

- 10,000.000 bales sold as cotton @ 6c $300,000,000.00.

- 10,000,000 bales sold as cloth @ 18c 900,000,000.00.

This would bring to the people of the cotton region in America three times the money now received for the cotton crop. It is not to be assumed that the markets would take the entire crop in the shape of plain, white

Page 20

and colored goods. But, with our increasing trade with other countries requiring plain goods, there would seem to be ample room to extend operations in that direction for some time to come. The following are some figures relating to Chinese trade.

- Imports into China $170,991,384 value.

- Imports from U. S. into China 9,659,440 value.

- Imports Cotton Goods into China 64,028,692 value.

- Imports Cotton Goods U. S. into China 7,438,203 value.

There are other countries more or less similarly situated.

In North Carolina the quantity of cotton manufactured is something over 300,000 bales. The report of the commissioner of labor for the State shows that this requires something over 30,000 operatives in her factories. Thus in making plain goods, white and colored, a factory will consume about ten bales of cotton for each person employed.

At this rate an entire crop of American cotton aggregating 10,000,000 bales could be manufactured into plain goods by 1,000,000 operatives. The population of the American cotton producing area is probably about 20,000,000 people. Those who know the existing conditions will probably not dissent from the opinion that it would be easy to put 1,000,000 people to work manufacturing cotton, and never miss them from present employments.

Estimating 12,000,000 out of the entire population as being white people, even from amongst these, a million could be more than easily spared.

The creation of the means for profitable employment in any community elevates the community and the people also. Districts that are purely agricultural furnish scant encouragement to those who are not situated so they can farm. There is many an instance where a person has lived a humdrum life in an agricultural community, and whose energies were not held in high esteem, but who became of great value in the development of a manufacturing interest.

Figure. 11. Old Road, Charlotte, N. C., 1888.

Figure. 12. New Road, Charlotte, N. C., 1898.

Page 21

The above estimate of the possibilities with present conditions is based to some extent on actual results that have been attained in North Carolina. By the report of the commissioner of labor, the crop of the State is something over 500,000 bales; 500,000 bales @ 6c. would yield $15,000,000; 300,000 bales now manufactured into cloth and yarn actually do yield an average of 18c. or $27,000,000. The value of the remaining 200,000 bales @ 6c. would be $6,000,000. Thus the crop of North Carolina now actually yields in money to her people about $33,000,000 as against $15,000,000 if the whole were still sold in a raw state.

The factory that triples the price of cotton should also triple the value of the neighboring land upon which the cotton is produced. The factory in effect, pays a bounty to the farmer. This bounty is paid as follows:

1. A factory pays an average of ¼ cent more for cotton than is paid for shipment or export. While this is not a voluntary contribution, (the factory pays it to keep the local cotton from going away, thereby avoiding paying freight on other cotton.) It is about one dollar per bale bounty to the farmer nevertheless.

2. A market is created for wood, chickens, eggs, butter, milk, fruit, vegetables, pork, mutton, and every other food stuff for humanity that a farm in the cotton region is capable of raising.

3. There would be from time to time profitable occupation for some members of farmers families in teaching school, working in the factory, clerking, etc., etc. Doctors and store keepers get patronage and trade, and these in turn must have food stuffs.

It is easy to perceive that with ample markets and other advantages, a thrifty farmer could double his income by the sale of stuffs for which, without manufactures, he has no markets, and much of which he now produces and loses.

Some apprehension has been expressed that the factories would injure the farming interests. That the better and more regular wages in factories would attract people

Page 22

from the farms and thus cause their abandonment. As a matter of fact, the tendency is the other way. As factories are established and increased, farming becomes more and more attractive. This is not a matter of opinion or a theory, but the increased value of land and the better condition of the farming interests are conspicuous whereever factories have been established.

If, however, it should become necessary to still further stimulate the farming interests beyond what the factories naturally give, this could be profitably accomplished by paying a direct bounty on every pound of cotton produced. The need for this is a long time off; for reasons have already been given to show that the establishment of factories is calculated to double the income of neighboring farmers. This is the same result as if cotton brought in the market 12 cents instead of 6c. or 10c. in place of 5c.

In the previous discussion, the manufacture of plain white goods and ordinary checks and plaids have been considered. These bring an average price about three times the value of cotton. With increasing knowledge, skill and experience, goods may be made which are worth five times and ten times the value of raw cotton. In order that the greater advantages of these better prices may in future be obtained, it is important to give careful attention to the subject of Textile Education. Assuming that the crop of 10,000,000 bales could be made worth an average of 60c. a pound by manufacture into finer goods at home, we would have:

10,000,000 bales at 6c. yielding now $300,000,000.

10,000,000 bales at 60c. yielding then $3,000,000,000.

Organdies in any dry goods store sell every day at the rate of 60 cents per pound. Finely made and well finished cotton goods of many kinds sell as high as $2.00 per pound, and even higher.

We all know that the cheapest and best raw material in the world for plain clothing (cotton) is available here in great quantity. That the market for the product is the whole world. That there is a large idle population

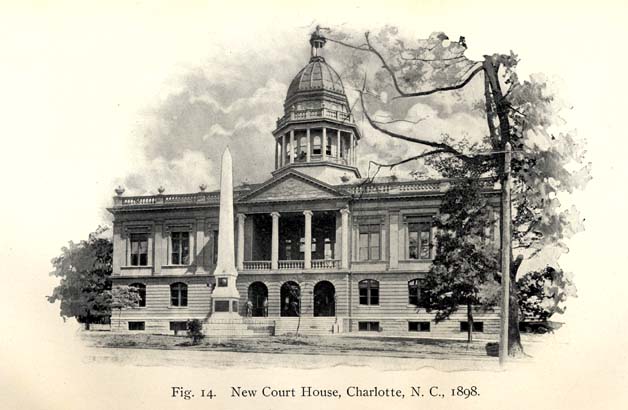

Figure. 13. Old Court House, Charlotte, N. C., 1888.

Figure. 14. New Court House, Charlotte, N. C., 1898.

Page 23

capable of making good operatives and needing employment. It has already been proven that manufacturing can be successfully carried on in the cotton growing area of the United States. We need fostering laws, the confidence of home capital, education and training in textile work.

Overproduction.

The question of overproduction would seem to be dependent on the development of foreign trade to take the goods. The cotton crop is now about ten million bales. About one quarter of this crop is manufactured in the United States. The remaining seven and a half million bales are sent abroad to be manufactured. If our export trade facilities should be made equal to those of England and Germany, then the subject would be reduced to one of our ability to compete. In plain white goods we are now competing in the Chinese, and some other markets, against the manufacturers of the world.

England and Germany and other countries are willing enough to send subsidized ships here to take away our raw cotton at 5 cents per pound. They would soon tire of taking away our manufactured goods at 15 cents per pound and upward. We must have our own national shipping facilities and our banking houses in the foreign countries.

With these advantages, there is no good reason why the American manufacturer cannot make cotton goods as economically as any other country, and extend his trade over the entire world. If this be done then the construction of new factories may continue until the entire cotton crop is manufactured at home. Without a growing export trade, there are now mills enough to supply the entire home markets. The American export trade is now growing rapidly, and seems fair to continue to do so. As long as this continues there is no immediate danger of overproduction.

If the cotton is manufactured at home, it is not only important, but essential, to have shipping facilities to distribute the manufactured products over the world.

Page 24

Our shipping interest is in exceedingly bad condition. In truth, excepting only in coastwise or domestic trade, we have very little shipping interest. While our future prosperity is dependent upon manufactures, the manufacturing interest, in turn, is dependent on the development and maintainance of a merchant marine which will distribute our goods over the world. Every cotton manufacturer and cotton farmer should aid in every way possible the development of our shipping interests.

We have more railroads than all the rest of the world combined. With these our domestic transportation facilities are the finest in the world, and our domestic freight rates are exceedingly low. Yet the ocean traffic under the American flag is insignificant.

The English travel in their own ships, as we travel in our own railway trains, but the Americans have neglected to provide facilities for foreign trade.

Much has been said about competition between the North and South in cotton manufacture. This talk seems to be without good reason. The cotton manufacturers of the United States, North and South alike, are together in competition with those of Germany and England. Conditions that will make prosperity in the South will also make prosperity in the North. It is important that the people of both sections work together to create proper shipping facilities for the export of our products and that we co-operate to bring about national laws to develop and foster our export trade in manufactured cotton goods.

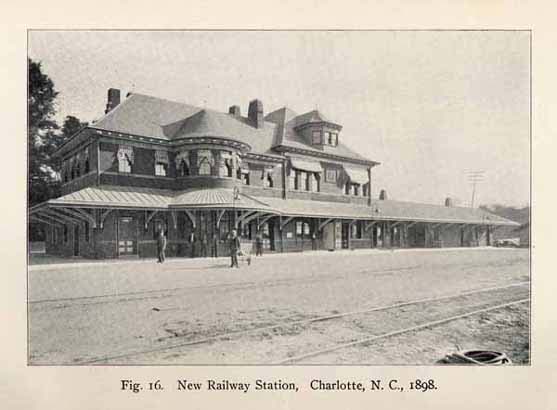

Fig. 15. Old Railway Station, Charlotte, N. C. 1888.

Fig. 16. New Railway Station, Charlotte, N. C. 1898.

Page 25

CHAPTER III.

Organization of Company.

The first move in the organization of a company is the subscription list. This is generally very simple, as follows:

"We, the undersigned, hereby subscribe the sums set opposite our names to the capital stock of a company to be formed for the purpose of building a cotton mill at or near ...... Edgefield, S. C.......Shares $100 each.

| Name. | No. Shares. | Amount. |

| .......... | ..... | ..... |

| .......... | ..... | ..... |

| .......... | ..... | ..... |

| .......... | ..... | ..... |

Another form, with conditions, would be as follows:

"We, the undersigned, hereby subscribe the sums set opposite our names to the capital stock of a company to be formed for the purpose of building a cotton mill at or near ...... Canton, Miss.......Shares $100 each.

When $65,000 is subscribed, the company may be organized and proceed to build a mill.

Additional subscriptions may be obtained up to $200,000.00.

| Name. | No. Shares. | Amount. |

| .......... | ..... | ..... |

| .......... | ..... | ..... |

| .......... | ..... | ..... |

| .......... | ..... | ..... |

Next after the subscription list comes the charter. The laws in different States vary so greatly, as to method of obtaining charters, that no suggestion can be made here as to charter except that a lawyer should be employed to obtain one. The charter ought to be as liberal as possible

Page 26

as to the limits of capital. It should permit starting business on a low minimum capital subscribed, and should permit continued subscriptions to a fairly high figure. If it is contemplated to raise $100,000.00 more or less, then the charter should make $75,000 the capital necessary before organizing and $250,000 the limit on the high side. Of course even this could be increased at a future time by amending the charter.

After the charter, comes a meeting of the stockholders to elect directors. At this meeting the By Laws should be ready and should be adopted.

The directors elect the officers. They should be authorized to call in the capital stock as needed. It might be better to fix the calls as for example 10 per cent. per month until the stock was paid to par value.

The By Laws for a cotton mill company are usually about as follows:

By-Laws.

Section 1. Members of this corporation shall be persons of the age of twenty-one (21) years and upwards. Minors may hold stock by trustees, but not otherwise.

Section 2. Each stockholder will be held bound to pay his assessments and faithfully observe and fulfill all the requirements of the Charter and By-Laws.

Section 3. Annual meetings shall be held second Wednesday of April of each year for the purpose of electing Directors and receiving the reports of officers, and for the transaction of any other business that may properly come up for consideration.

Section 4. At the annual meeting the President, Vice-President and Treasurer shall make their annual report.

Section 5. At all regular and special meetings of the stockholders a majority of the stock shall constitute a quorum for the transaction of business.

Section 6. The President and Directors or a majority of the Board may call a special meeting of the stockholders at any time on mailing written notice or publishing ten (10) days' notice thereof in a newspaper published in the city of--Charlotte.

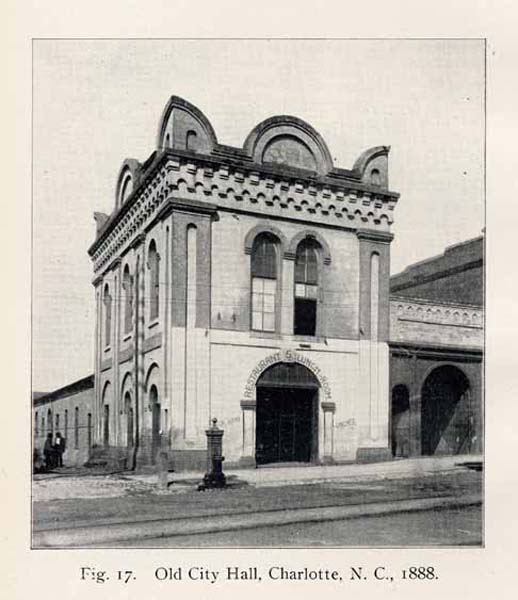

Fig. 17. Old City Hall, Charlotte, N. C., 1888.

Fig. 18. Old City Hall, Charlotte, N. C., 1898.

Page 27

Section 7. None but stockholders shall be eligible to the office of Director, and whenever any vacancy shall occur in the Board of Directors it shall be the duty of the Board to fill such vacancy until the next meeting of the stockholders.

Section 8. A majority of the Board of Directors shall constitute a quorum. In the absence of the President, the Vice President will perform the duties of the President.

Section 9. The Board of Directors shall meet from time to time and on such day as they may deem best for the interest of the Corporation; they shall constitute the Council of Administration, and it shall be their duty to manage the business affairs of the Corporation, to examine regularly the books and accounts of the Treasurer, and they may appoint from their own members, such committees as may be necessary, except as provided in section 17 of the By-Laws.

Section 10. The President shall have charge of all the property and affairs of the Corporation. He shall preside at the meetings of the Board of Directors, appoint committees and make all contracts for the Company, and the duties of all the officers shall be done subject to his direction and approval. He shall take into his keeping the bonds of the other officers of the Company, cause the Charter and By-Laws to be enforced, and cause the books and vouchers of the Company to be audited at regular intervals not exceeding six months. He shall be elected by the Board of Directors for one year, or until his successor is elected.

Section 11. The 2nd Vice President and Secretary shall keep the stock book and seal of the Company. He shall with the advice and approval of the President, purchase the cotton, supplies, etc., sell the goods and conduct the general business of the Corporation, all of which shall be subject to the approval of the Board of Directors. He shall be elected by the Board of Directors for one year or until his successor is elected. He shall keep a record of the Company's meetings and of the meetings of the

Page 28

Board of Directors. His compensation shall be fixed by the Board of Directors.

Section 12. The duties of the Treasurer shall be as follows: Keep an accurate set of books of all transactions of the Company, and make and submit to the other officers and the Board of Directors, a balance sheet each month, giving such analysis of the books as shall enable the officers to fully understand the profits, losses or other facts of importance relating to the conduct of the business.

He shall furnish, as often as required, vouchers for a proper audit of the Company's books and accounts.

He shall sign all checks, drafts and notes, provided that notes shall also always be signed by the President or second Vice President. The President or second Vice President may also countersign checks or drafts. In the absence of the Treasurer, the President or second Vice President shall sign checks, drafts and notes.

The Board of Directors shall fix his compensation.

He shall give bond in an approved Security Company for an amount to be fixed by the Board of Directors, but for no less than $10,000.

The fee for bond to be paid by the Company.

Section 13. It shall be the duty of the Board of Directors at least five days previous to every annual election for Directors, to appoint from the stockholders two competent persons to investigate the affairs of said corporation, and to make report thereof, which report shall be recorded in a book kept for that purpose, which shall always be open to the inspection of any Stockholder.

Section 14. Any officer of the Corporation may be removed or suspended for neglect of duty, breach of trust or other sufficient causes, by the Board of Directors.

Section 15. All assignments and transfers of stock must be made upon the books of the Corporation at least ten (10) days before each annual meeting, in order to entitle the assignee to all the rights and privileges of the original Shareholder at each annual meeting.

Section 16. Any person desiring to subscribe for stock at any time after the organization of the Corporation,

Page 29

may become a shareholder on such terms and conditions as the Board of Directors may prescribe.

Section 17. The President, except as otherwise provided for, shall appoint such officers and employees of the Corporation as may be required from time to time for the prosecution of its business, and fix the amount of compensation to be paid them.

Section 18. All election of officers shall be held by ballot.

Section 19. Certificates of stock shall be issued when Stockholders shall have paid their assessments in full. All certificates of stock shall be signed by the President and Secretary of the Company, with the seal of the Corporation affixed thereto.

Order of Business--Stockholders' Meeting.

1. Appointment of committee of two to ascertain the amount of stock represented in person and by proxy.

2. Reading of minutes of last annual and any intervening meetings.

3. Report of President with accompanying reports of officers.

4. New business, motions, resolutions, etc.

5. Election of Directors.

6. Adjournment.

Number of Directors.

In introducing manufactures into new territory, the companies are necessarily, in most cases, made up of many small subscribers. This generally changes as manufacturing grows. After manufactures are well established a new factory is generally organized by a small coterie of business friends. Sometimes three to five men will arrange to build a mill and then let in a few personal friends for reasonable amounts, if the friends desire to get in.

Even when the number of stockholders is large, it is not considered desirable to have large directories. Five directors is generally considered enough. Seven is not

Page 30

objectionable or uncommon. Harmony in the board is the important element. A mill might of course have 15 directors and have an efficient and harmonious board. The chances are, however, that with 15 members on a board they would either neglect their duties or wrangle and finally quarrel. This would mean the breaking up of the mill. Nothing will more certainly break a cotton mill company than a quarrel in the board of directors or amongst the stockholders. The officers should be of a kind that could occupy their positions one year after another without interruption.

One of the objections to a large list of stockholders is that there is liable to be some obstructive man who is purposely making trouble for the executive officers. It may be a man who wants to buy cotton for the mill, or do the law business for the mill or be treasurer, or it may be one who simply delights in making trouble.

Sometimes when a company has many stockholders a small coterie of these get enough stock to control the company and then these determine in a conference what is to be done and what not done. Then when the stockholders meet, the dissentious element can do little harm.

In most companies the minority stock tends to scatter. It is bought by individuals for investment, and the known strength of the controlling majority is a point in favor of the stock rather than against it.

Salaries.

The personnel of the organization varies so much that there is no standard method of organizing or of fixing salaries. It is entirely unlike the political organization of a State, having a governorship with a fixed salary and well defined duties, and other official positions having fixed salaries and well defined duties.

When manufactures have become well established, a new mill is sometimes organized by a number of men who perceive that some one man is a promising manufacturer. So much stress is laid on the qualities of the man that investors will raise money to be put in the hands of the good manufacturer. In such case this man would be apt

Page 31

to be made President and Treasurer and be allowed to select his own bookkeeper who would be made secretary.

If this is a young man he might have been receiving in his old place $1,200, $1,500, $1,800, $2,500 or even $3,000 per year salary, according to size of mill. In the new place, he might get $1,500, $2,000, $2,500, $3,000 at the start of the new enterprise, with the understanding that he is to receive better pay when the new property is made a success.

For a mill of 10,000 spindles and 320 looms, the salary list might be as follows.

| President and Treasurer | $2,500.00 |

| Secretary | 1,200.00 |

| Superintendent | 1,500.00 |

or it might be with an entirely different set of people as follows:

| President | $ 600.00 |

| Secretary and Treasurer | 2,000.00 |

| Superintendent | 1,800.00 |

In the former case the President and Treasurer would be the man to give his entire time and attention to the business.

In the latter case, the Secretary and Treasurer would be the active man of affairs, the President probably making the financial arrangements and exercising very general supervision.

In a mill having 50 to 100 thousand spindles the President and Treasurer, when the active man would receive a salary of $8,000 to $12,000. The Secretary would get about $2,000 and the Superintendent $4,000.

In a mill of 75,000 spindles, the salary list might run as follows:

| President and Treasurer | $10,000 |

| Secretary | 2,500 |

| Superintendent | 5,000 |

| Bookkeeper | 1,500 |

| Shipping Clerk | 1,000 |

| Cotton Buyer | 2,000 |

| Total | $22,000 |

Page 32

It might be said that the salary list varies from 2 to 3 per cent. of the capital stock, but this is no rule. Sometimes it is more and sometimes less. The desire of the stockholders is always to get a man who can make good profits and the man who can do this can command a salary that bears no relation to anything else except the profits he makes.

Experience shows that the man who knows his business well and can handle his labor well is cheap at any price.

It has been fairly well demonstrated that small mills pay about as well as large ones where proper attention is given to keeping down fixed changes. A small and comparatively poor town should not expect to be able to build a large factory. But it may build a small one, and by hard work and careful management develop it into a large one.

The history of all people and of every nation is that there is always room for people of moderate means to start business in a small way and make it successful. Whenever this becomes otherwise in any country, then civilization has reached its maximum and that country will not long survive.

Cotton mills have been started with 25 to 30 thousand dollars and made successful, even by people not very familiar with the business.

In Philadelphia many a good weaver has saved money enough to buy one or two dozen looms and started business in some rented loft, renting power also and buying yarn. Such a business has been started with as little capital as $2,000 or $3,000 and ultimately developed into a large manufacturing establishment.

There would, therefore, seem to be neither a high nor low limit of capital necessary for the construction of a cotton mill for those who are experts in the process.

For those not familiar with the processes, a mill of sufficient size must be built to warrant the employment of a skilled Supt. The business can always be done by home people. It would seem as if about $65,000 to $75,000 is the low limit of capital that ought to be subscribed

Page 33

for a cotton mill in a new section. With this sum, a mill of 2,500 to 3,000 spindles and 80 to 100 looms can be erected, including operative's houses, but no surplus or working capital.

It is best of course for a cotton mill to have 10 to 20 per cent. of its capital stock as working capital.

The older mills in the South generally arrange this out of their surplus.

As a matter of fact, however, most of the new mills start without working capital. Money for cotton is borrowed from home banks, and the product is either sold or consigned to a commission house and drawn against for 75 to 90 per cent. of its value.

The most ordinary plan is to borrow money at home for cotton, and then sell the product as fast as made.

In some cases the banks will lend money to a mill on its own note, holding a claim on cotton purchased, as additional security. Sometimes the bank also wants the indorsement of the President or Treasurer, or both. In a few cases the entire Board of Directors indorses the paper to raise working capital for the mill. This latter is rarely done except when the cost of the mill exceeds the capital stock, thereby leaving the mill in debt on its construction account as well as for the working capital.

Page 34

CHAPTER IV.

Location and Surroundings.

The conditions to be examined into preliminary to the establishment of a cotton manufacturing plant may be enumerated as follows: location, water supply, freight rates, raw material.

Location.

The location should be healthful above all other considerations. Factory operatives cannot do good work except in good health.

The character of the ground should at a reasonable depth furnish good foundations.

The factory and the houses should be above overflow level from any adjacent stream or otherwise.

There should be ample room for operatives houses and if possible space should be allowed with each house for a garden. Half acre for each house is desirable if it can be obtained at reasonable price. For a ten thousand spindle mill, 5 to 10 acres for the mill lot and 40 acres for operatives houses would be desirable.

In organizing a new company, the people who subscribe to the stock, often do so not only as an investment but as a help to the town in which they live. In pursuance of this thought, they frequently argue for locating the mill within the incorporate limits of the town or city.

On the whole, it may be considered good advice for a new mill not to locate within the limits of a city or town. If the matter of building up a town is to be considered, a mill located just outside the incorporate limits will escape city taxation and other disadvantages, and at the same time contribute to the city's trade. Small country stores are likely to spring up in the vicinity of the mill and absorb some of the trade; but a similar condition would also divide the trade if the mill was in the city.

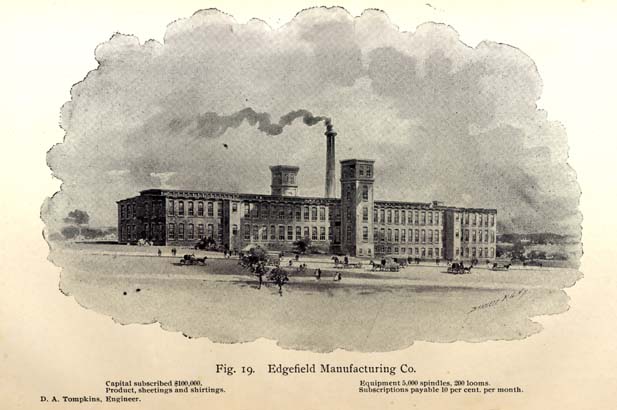

Fig. 19. Edgefield Manufacturing Co.

Capital subscribed $100,000.

Product, sheetings and shirtings.

D. A. Tompkins, Engineer.

Equipment 5,000 spindles, 200 looms.

Subscriptions payable 10 per cent. per month.

Page 35

If building up the trade of a city has no influence in the locating, the mill may be located to advantage in the remote country, where the full benefit of mercantile features may be enjoyed by the mill company.

There are advantages and disadvantages in locating in a city. There are also advantages and disadvantages in locating in the country.

The employees generally prefer to live in a city. Therefore a city mill gets some preference as to employees. In most cases city taxes must be paid, which is a disadvantage. The proximity of lawyers also promotes law suits both in the business of the mill and for operatives that may be hurt in the mill in any accidental way. The mercantile business necessarily goes to the people of the city or town, whereas a mill in the country can operate its own store and thereby get back in mercantile profit much of the money paid for wages.

An important advantage of locating in the country is that employees go to bed at a reasonable hour and are therefore in better condition to work in day time.

Water Supply.

It is very important that a good water supply be obtainable, both for drinking purposes and for power and other general purposes.

For power purposes, where the power is steam, the water needed for a non-condensing engine should be at least 5 gallons per horse power per hour. For fire protection, scouring, &c., &c., another five gallons per horse power would not be amiss.

It is better still to have practically unlimited water so that a condensing engine can be operated without the need of the cooling tower.

Where the surface water supply becomes inadequate, as happens sometimes in extension of the mill, or otherwise, it frequently happens that an underground supply can be found by a suitable sub-surface survey. This would consist of a series of drillings and careful observations of the geological conditions by an expert.

Page 36

Freight Rates.

There is no point in the cotton growing area where freight rates would prohibit the manufacture of cotton. There are points where coal would be somewhat expensive, but wherever the rates on goods would be high, the rates on cotton would also be high, and the local price of cotton would be correspondingly low. The freight on machinery and supplies would of course count for something, but this is mostly on the first cost of the plant. If possible, it is better to locate where two different systems of railway can be reached. This is not because rates would be made less, but for the advantages of small accomodations from the local agents who will if necessary, compete to some extent within the limits of the agreements of the companies or general officers.

Raw Material--Cotton.

The question of raw material is one of the first matters to claim attention in locating most manufacturing plants. But in the cotton producing region, it is of less importance than any other one element. Cotton may always be procured under as favorable conditions and prices as competing factories. If there should appear to be a difference one way or another, it is usually offset by other advantages or disadvantages.

General Conditions.

In some States new factories are relieved by law from taxation for a period of years, generally ten years.

There is an impression that the mills operated by water power have been more profitable than those operated by steam. The water power mill is almost always in the country and generally operates its own store. The mercantile business gives some advantage but a steam mill under the same conditions would get the same advantage, and on an average would do as well.

Steam is, in fact, the power of the world. Omitting home made or hand made products perhaps 95 per cent. of the goods of the world are made with steam power.

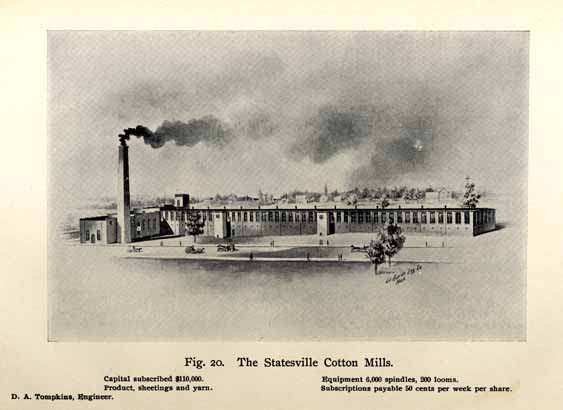

Fig. 20. The Statesville Cotton Mills.

Capital subscribed $110,000.

Product, sheetings and yarn.

D. A. Tompkins, Engineer.

Equipment 6,000 spindles, 200 looms.

Subscriptions payable 50 cents per week per share.

Page 37

Therefore the prices of products are based upon the cost of steam power.

The relative quantity of steam and water power used will probably be changed by the use of electricity for transmitting water power from points where the water power is located to points where it can be used. Many water powers heretofore unavailable are on this account becoming valuable.

Many mill companies provide school houses and contribute something to the support of schools. It can generally be arranged to get a fair proportion of the public school fund upon condition that the school trustees be allowed to have something to do with selecting the teacher and conducting the school. A few factory companies furnish houses and support schools entirely at the cost of the factory companies.

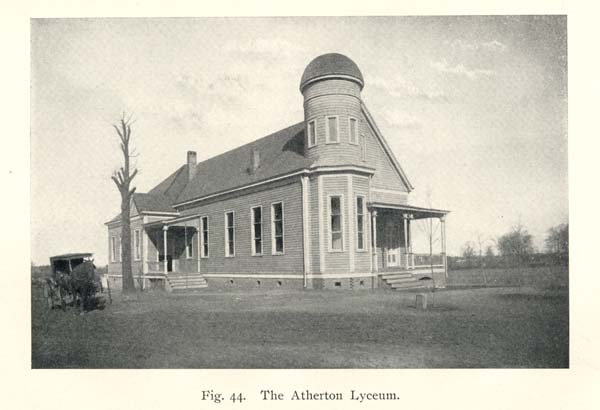

Many factories furnish a house called a Lyceum or Auditorium. This is held for the free use of the operatives for church and Sunday school purposes and for holding proper entertainments or conducting innocent amusement.

A few mills provide and maintain libraries for the free use of the operatives.

Sometimes one building serves as a school, auditorium, library and reading room.

The most successful and intelligent cotton mill managements are giving more and more attention to the subject of improving the condition of factory operatives and promoting the cause of education among them. Motives of philanthropy are partly responsible for this, but the business interest of the mill is another important incentive. Moral influences and education make better work people.

The officers of well managed corporations give full attention to cleanliness and good order inside a mill and also to the general appearance of grounds and surroundings. Every good superintendent has been trained to know that a dirty mill cannot turn out first-class product.

It is less generally recognized, but equally true, that

Page 38

ill kept grounds and surroundings have their ill effect upon the habits of the operatives.

Perhaps the most important element in good management is cleanliness and neatness inside the mill and well kept grounds and surroundings outside. It should be the pride of every president and superintendent to make the company's property conspicuous by its cleanliness, neatness and well kept appearance.

Some cotton mills in the South are operated night and day. This is done with two different sets of operatives, each working about 11 hours per turn. Sometimes the night turn works only 10½ hours. Sometimes only the spinning is operated at night. In this case there would either be looms enough to consume the night and day product of the spindles, or else the product of the night turn would not be woven, but be sold as yarn.

New England mills seldom run at night.

Many people in the South are opposed to night work for women and children.

The large mills of the South do no night work.

In course of time probably none of the mills will be operated at night. The increased demand for labor in the new factories will give everybody a chance to get day light employment, which of course is preferred.

The criticisms made about night work, however, are largely sentimental, and the trouble about it is more in the minds of the critics than with the operatives themselves.

Nevertheless, when factories are only operated in day time, it will be better for the factory and operatives. No legislation is needed to bring about this change, as it will come in the ordinary course of factory evolution.

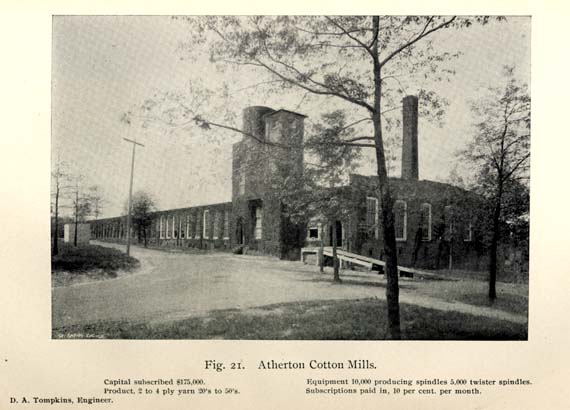

Fig. 21. Atherton Cotton Mills.

Capital subscribed $175,000.

Product, 2 to 4 ply yarn 20's to 50's.

D. A. Tompkins, Engineer.

Equipment 10,000 producing spindles 5,000 twister spindles.

Subscriptions paid in, 10 per cent, per month.

Page 39

CHAPTER V.

Raising Capital.

In most places where a new mill is proposed, an idea is prevalent that if half the money is raised at home, then somebody from somewhere will furnish the other half.

Several years ago the builders of cotton mill machinery took stock in new mills as part payment for the machinery. This brought on numerous complications and trouble, and the practice has now been entirely abandoned.

Commission houses in the North who sell cotton mill products, have often taken stock in new Southern mills. They do this of course mostly for the sake of controlling the sale of the mill's products. For, while Southern mill stocks are always splendid property, there must always be some extra inducement for capital to seek investment in distant localities. A mill, having a large part of its stock owned in this way, is restricted in the sale of its products to one special market, which market might at some time not be the best for that particular kind of product.

All foreign capital is attracted to new enterprises at a distance by some distinct motive and is governed by well defined laws. Large amounts of Northern money have been invested in Southern cotton mills; but they have been influenced by the motive above mentioned, or have been invested in stocks of mills already successful, or with men well known as successful manufacturers. The distant capitalist is attracted by success already accomplished, and is not disposed to risk money to prove whether a new locality and a new people are both adapted to make a success of cotton manufacture. Success in a new mill or town once established often brings foreign capital without the asking.

The home capitalist is influenced largely by the same motive as the foreigner. He prefers for some one else to make the experiment in manufacturing; if it is a failure

Page 40

then he has escaped; if it is a success, then he can go in and buy the stock or start a new similar enterprise.

The average Southern town underestimates its ability to raise capital to build a cotton factory. Cotton mill property, like all other property, is cumulative. No town could raise the money at once to pay for all the property in it.

When the author first went into business in Charlotte. N. C., in 1884, there was but little cotton manufacturing in the South, and in Charlotte but one mill. The author at once formulated a plan for enabling small towns to raise capital for manufacturing.

This plan was published in several periodicals and was reprinted in the form of a pamphlet. As it covers the ground of installment mills so fully, it is reproduced here in full.

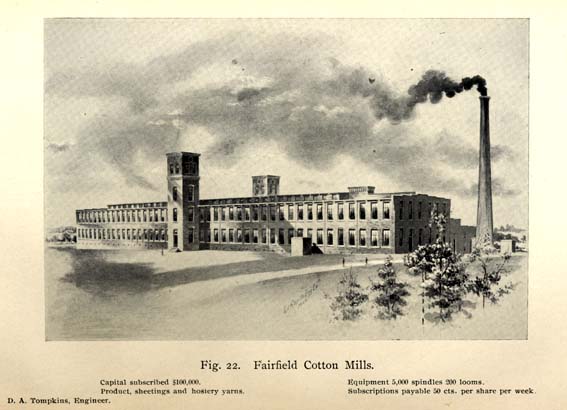

Fig. 22. Fairfield Cotton Mills.

Capital subscribed $100,000.

Product, sheetings and hosiery yarns.

D. A. Tompkins, Engineer.

Equipment 5,000 spindles 200 looms.

Subscriptions payable 50 cts. per share per week.

Page 41

Preface to "A Plan to Raise Capital."

While working as a machinist, and in other capacities, for the Bethlehem Iron Works, Bethlehem, Pa., I always carried some stock in one or more of the local Building and Loan Associations at Bethlehem.

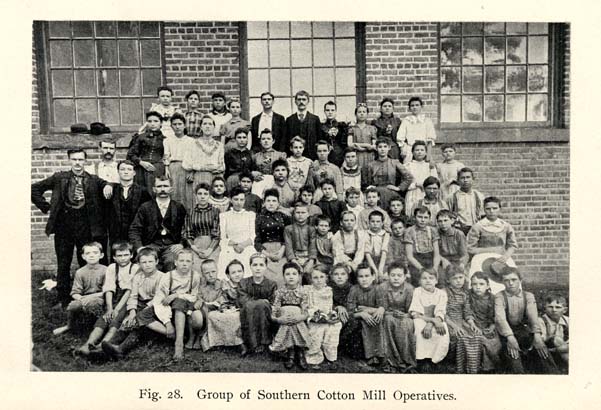

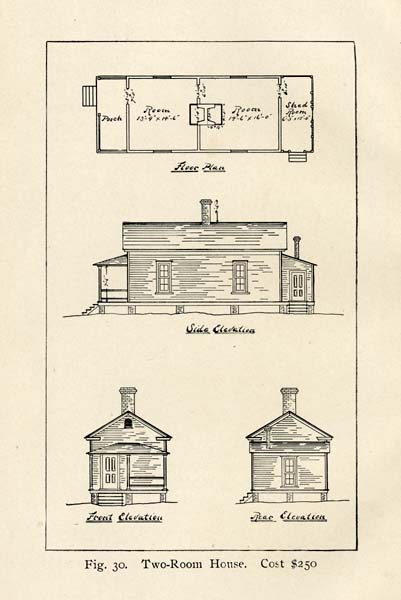

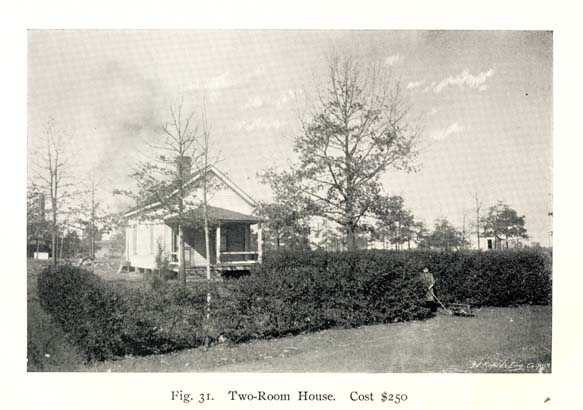

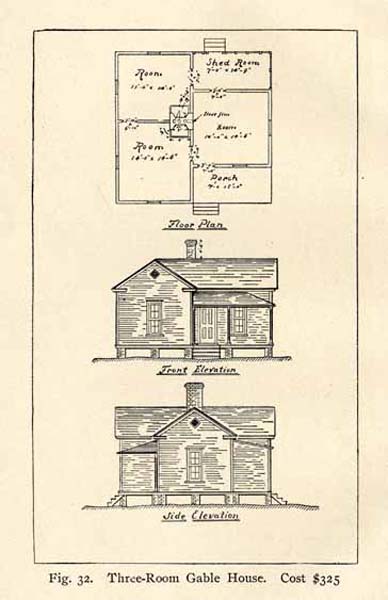

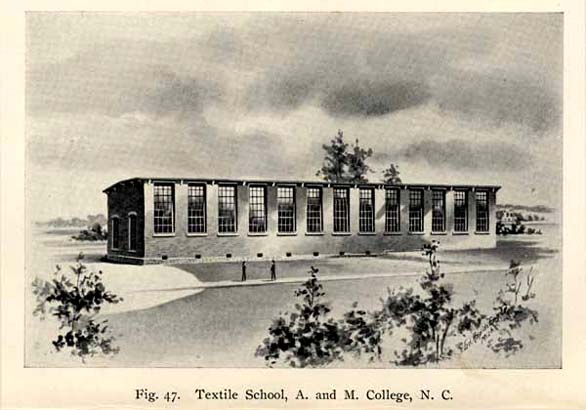

Towards the latter part of my service with that company. I devised plans for the organization of a Savings Fund and Building Association. The plan was that nine of my fellow-workmen with myself should form an association for saving something out of our salaries and wages each month, and, putting these savings together, should use the fund,--not to loan, but to build houses for rent and for holding as investment.