Life and Narrative of William J.

Anderson, Twenty-four Years a Slave;

Sold Eight Times! In Jail Sixty Times!! Whipped Three Hundred Times!!!

or The Dark Deeds of American Slavery Revealed.

Containing Scriptural

Views of the Origin of the

Black and of the White Man.

Also, a Simple and Easy Plan to Abolish Slavery in the

United States.

Together with an Account of the Services of Colored Men in the

Revolutionary War--Day and Date, and Interesting Facts:

Electronic Edition.

Anderson, William J., b. 1811

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Text encoded by

Lee Ann Morawski and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2000

ca. 125K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) Life and Narrative of William J. Anderson, Twenty-four Years a Slave;

Sold Eight Times! In Jail Sixty Times!! Whipped Three Hundred Times!!! or The Dark Deeds of American

Slavery Revealed. Containing Scriptural Views of the Origin of the Black and of the White Man. Also,

a Simple and Easy Plan to Abolish Slavery in the United States. Together with an Account of the Services

of Colored Men in the Revolutionary War--Day and Date, and Interesting

Facts

Written by Himself

81 p.

CHICAGO:

DAILY TRIBUNE BOOK AND JOB PRINTING OFFICE.

1857.

This electronic edition has been transcribed from a photocopy supplied by the University

of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the

American South.

The text has been

encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar,

punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved.

This electronic

edition has been transcribed from a photocopy supplied by the University

of Minnesota, Minneapolis.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as

--

Indentation

in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft

Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- African American clergy -- Biography.

- African American Methodists -- Clergy -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Religion.

- African Methodist Episcopal Church -- Clergy -- Biography.

- Anderson, William J., b. 1811.

- Fugitive slaves -- Biography.

- Plantation life -- Southern States -- History --19th century.

- Slavery -- United States -- History -- 19th century.

- Slaves -- United States -- Biography.

- Slaves' writings, American.

- United States -- History -- Revolution, 1775-1783 -- Participation, African American.

Revision History:

- 2001-09-26,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-09-15,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-08-08,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-07-21,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

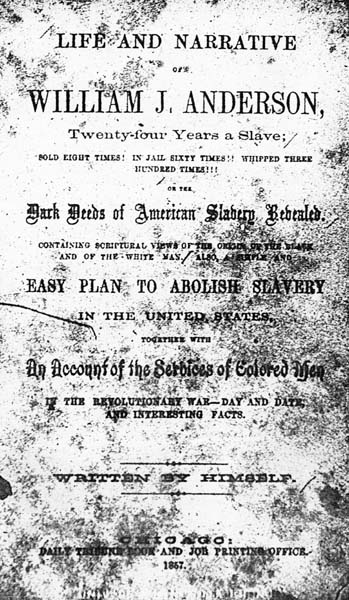

[Title Page Image]

LIFE AND NARRATIVE

OF

WILLIAM J. ANDERSON,

Twenty-four Years a Slave;

SOLD EIGHT TIMES! IN JAIL SIXTY TIMES!! WHIPPED THREE

HUNDRED TIMES!!!

OR THE

Dark Deeds of American Slavery Revealed.

CONTAINING SCRIPTURAL VIEWS OF THE ORIGIN OF THE BLACK

AND OF THE WHITE MAN. ALSO, A SIMPLE AND

EASY PLAN TO ABOLISH SLAVERY

IN THE UNITED STATES,

TOGETHER WITH

An Account of the Services of Colored Men

IN THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR--DAY AND DATE,

AND INTERESTING FACTS.

WRITTEN BY HIMSELF.

CHICAGO:

DAILY TRIBUNE BOOK AND JOB PRINTING OFFICE.

1857.

Page 3

PREFACE.

After praying to God and asking His blessing to rest upon me and my book, I enter into the task, because I have the blacks and some of the whites to contend with. The blacks I know will be prejudiced against me because I cease to labor as they do, as a general thing--and some few of the prejudiced whites think that all colored men ought to work with the plough and the hoe. But as I know all kinds of wicked lies will be raised by my own race, I have engaged the arm of Almighty God to help me. The truth is, very few ever have been through what I have.

I have been sold, or changed hands about eight or nine times; I have been in jail about sixty times; I had on irons or handcuffs fifty times; I have been whipped about three or four hundred times. Any persons who do not believe what I say, if they are very desirous of knowing the fact, can see the receipts by paying the stipulated sum of five dollars.

Many persons can easily say they do not believe thus and so, but the truth is, few say this that have been through the mill of slavery. I will tell who say a great many things wrong, the slaveholders in heart and dough-faces of the North, where I came expecting to find all free in heart.

Page 5

LIFE AND NARRATIVE

of

WILLIAM J. ANDERSON.

CHAPTER I.

MY BIRTH AND PARENTAGE--SERVITUDE--COMFORTS, ETC.

I was born June 2d, 1811, of a free mother, in Hanover county, Va., her name was Susan. My father's name was Lewis Anderson, who was himself a soldier slave, belonging to a Mr. Shelton. After the war of '76, his master told him to go home--he would do something for him. But he died a slave. My mother, now a widow, and being indigent and needy, bound me out to a Mr. Vance, a slaveholder, some ten miles from where she lived. Being young and inexperienced, poor and penniless, I was thrown among the slaves and had to fare just as hard as they did; under slave influence I had to live and suffer, and was brought up. But the truth is, I had no bringing up; I was whipped up, starved up; kicked up and clubbed up. I had no schooling except what I stole by fire and moon light, with a little Sabbath light.

Page 6

Slaveholders laws are positively opposed to the slave learning anything more than to handle the axe, plough and hoe. Often have I been whipped for trying to learn my book or read my bible; still I was permitted to visit my mother's cabin, and attend preaching meetings sometimes, with a written passport.

So matters and things moved on with me tolerable peaceably. I lived at a place where I could see some of the horrors of slavery exhibited to a great extent; it was a large tavern, situated at the crossing of roads, where hundreds of slaves pass by for the Southern market, chained and handcuffed together by fifties--wives taken from husbands and husbands from wives, never to see each other again--small and large children separated from their parents. They were driven away to Georgia, and Louisiana, and other Southern States, to be disposed of.

O, I have seen them and heard them howl like dogs or wolves, when being under the painful obligation of parting to meet no more. Many of them have to leave their children in the cradle, or ashes, to suffer or die for the want of attentive care or food, or both.

Had I the ability of language and learning, I would try to portray the condition of the slave. To be a slave--a human one of God's creatures--reduced to chattelism--bought and sold like goods or merchandise, oxen or horses! He has nothing he can call his own--not even his wife, or children, or his own body. If the master could take the soul, he would take it; but I believe the lord takes care of that.

The slaves are kept entirely ignorant, cowed down by the lash and hard work, in Virginia, by the legislature and police, or patrol--nothing is neglected that is calculated to keep the slaves cowed down. In this condition I grew up through much trouble.

Page 7

I wish here to remark that there are some exceptions to the general rule of slaveholding--some are more cruelly treated than others. While I lived in old Virginia I fared tolerably well, considering my condition, which was equal to that of a slave. The Sabbath was observed where I lived; but my master was a hard worker and sometimes whipped hard; but my mother thinking all things were right, did not give herself any uneasiness about me, thinking him such a good man, who had promised such righteous and good things for me. But slaveholding is deception any way you take it; it undoubtedly is the greatest evil beneath the sun, moon or stars; intemperance or Indian barbarities do not compare with it, and I think it will be proved, as the sequel will show, that it is the worst institution this side of hell or heaven.

Page 8

CHAPTER II.

MY EARLY STUDIES OF RELIGION AND LEARNING--OPPOSITION, ETC.

When I was a small boy I desired two things; one was to be a good Christian, and the other was to learn my book well. I often stole away in private or secret to pray. I often stole away to prayer meetings and preachings. Early, as in good ground, was the precious seed of grace sown in my heart; but like many others, hard trials, whippings, slavery and bad company drew off considerable from these precious feelings; yet, I thank God that I retained them and thought on them, for they hardly left me night or day, until I arrived in the State of Indiana; there I shortly after made a profession of the love of God being shed abroad in my heart, and joined the church. I think we as a race ought to try and get to Heaven, where there is no slavery, or whipping, or selling for gold. O, that God would keep me faithful till death.

When I got to Mississippi, where they work, curse, swear and dance on Sunday, I felt awfully; no preaching or Bible to read, or anything to give consolation, but the whip and hard work; no one called on God for a blessing, but a curse. But I think God it was no worse with me than it was, for many fared worse than I did.

In getting the learning I obtained, I had to buy my book and keep it very secretly. Though very young, say about eight or nine years old, I often carried my book in my hat or

Page 9

pocket, for fear of detection, and hid it in the leaves or earth for fear of the lash or detection, for it was against all the laws of Virginia for slaves or blacks to be taught to read or write; but by hard study and labor, and much secrecy, and the assistance of some little white boys and girls, I managed to gain some information. While the slave boys would be playing marbles, my attention would be on my book; often, when I would be looking on my book, the approach or sight of a white man made me put it aside. In this situation, how I have mourned for a little instruction.

Finally, after Providence had smiled on me, and I could read a little, I then desired to learn to write. My copies were old scraps of writing that I could pick up at times. Then, after my day's work was over, by fire-light I would practice upon my lessons in writing. In passing on during the day, when I had an opportunity I would stoop down and practice a little in thousand, but when the old slaveholder saw it, he would tell me that I was studying philosophy, and that he would whip it out of me, etc., etc.

Thus, I thank God, I made such advancement that I could read and write considerable. There being many in my condition who wanted to learn very badly, they persuaded me to teach them a little on Sundays; so we went on teaching and learning a few Sundays before the white people found it out, and gave us our orders never to meet for instructions any more, on the peril of the lash; and our little school was broken up forever.

Then I was watched closely the balance of the time I staid in Virginia, so the reader may account for my imperfections in my simple narrative and tale. But here, Christian reader, my heart runs out in thanks to God for his great blessings toward me, who, I must acknowledge, as David said, "The Lord is my sheperd, I shall not want; surely goodness and

Page 10

mercy have followed me all the days of my life and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever." Yes, reader, I can look back and see the goodness of God in all the train of my distress, and if they are faithful, I think many poor slaves will get to Heaven, where there is no slavery, or whipping, or selling Christian slaves for gold.

I have often thought it would be a good and great thing if all the slaves and free persons would unite and pray for deliverance; I believe God would graciously deliver them out of their Southern bondage; I believe the time would shortly come when God would aid them from Heaven. O, when God works, moves, and thunders, and shakes the earth, man trembles, shakes, quakes and fears. As the poet says:

"God moves in a mysterious way,

His wonders to perform;

He plants his footsteps on the sea

And rides upon the storm."

Deep and unfathomable is the power and wisdom of God. O, that we all would trust the Lord for his goodness, which endureth forever.

Page 11

CHAPTER III.

KIDNAPPED--SOLD INTO TENNESSEE--SUFFERING ON THE WAY, ETC.

My master was considered one of those cunning, fox-like slaveholders; his craving for gold was almost insatiable; he kidnapped me by night, when all things were as silent as death, handcuffed and chained me securely, while I was ten miles from my mother, and young and inexperienced, helpless and ignorant of the geography of the country. The horrors of leaving my native land I cannot express. I was hurried off, and not permitted to get my clothes or bid my friends farewell.

We arrived early next day in the city of Richmond, the capital of the State. The slave-market space was very much crowded; so he sold me privately, for three hundred and seventy-five dollars. A southern trader bought me; he asked me if I ever run, I told him I had. He asked me if I could run fast; I told him I could. He asked once more if I ever ran away; as I always stood much upon truth, I told him I had, once only, and stayed away one day. So he put me in jail, there to remain until he made up his drove of slaves, which was a very few days. But I, a free boy, locked up in jail! It was a bad and horrible feeling.

In a few days he made up his drove, to the number of some sixty-five or seventy. Myself and several men, say twenty or more, were chained together, two and two, with a chain

Page 12

between. In this situation we started, on the 6th of Nov., 1826, for East and West Tennessee. Then we sang the song--

"Farewell, ye children of the Lord, &c."

We traveled a few days, and scenes of sadness occurred; the snow and rain came down in torrents, but we had to rest out in the open air every night; sometimes we would have to scrape away the snow, make our pallets on the cold ground, or in the rain, with a bunch of leaves and a chunk of wood for our pillow, and so we would have to rest the best we could, with our chains on. In that awful situation the reader may imagine how we gained any relief from the suffering consequent upon the cruel infliction we had to endure. We were driven with whip and curses through the cold and rain.

One thing in particular attracted my attention on my way to Tennessee; it was the sight of about fifty women working with picks, hoes and shovels, and a large white man cursing and driving them with a ship; all had on hats alike.

Our route was straight up the James River; we passed many towns which it would be useless to mention. In about two months we arrived safely in Nashville, West Tennessee. Our irons were knocked off from our limbs. O, the soreness and awful feelings are inexpressible.

We were here sold and joined with another drove, and awaited the horrors of another journey, or to prepare in one hell for another. But while we were here delayed the slave, women brought forth several illegitimate children, which is very common, as the white gentlemen had been cohabiting with them before and during the journey, which is one of the greatest curses about slavery, as this narrative will show. And here, in Nashville, I saw them bought and sold like cattle, as in old Virginia.

At the raising of the river we were all huddled on the

Page 13

boat, very uncomfortably together, and down the river we went, still grieving, mourning and sorrowing over our fate. About this time a horrible accident happened on a boat; a gang of colored men, chained together, were drowned in the hull of the boat. The cries and wailings of the poor creatures, while struggling with death, were horrifying and frightful in the extreme. No words can describe the dreadful scene.

Page 14

CHAPTER IV.

OUR ARRIVAL AT NATCHEZ--MANAGEMENT, SALES, ETC.

In due time we arrived safely in the slave-pen at Natchez, and here we joined another large crowd of slaves which were already stationed at this place. Here scenes were witnessed which are too wicked to mention. The slaves are made to shave and wash in greasy pot liquor, to make them look sleek and nice; their heads must be combed, and their best clothes put on; and when called out to be examined they are to stand in a row--the women and men apart--then they are picked out and taken into a room, and examined. See a large, rough slaveholder, take a poor female slave into a room, make her strip, then feel of and examine her, as though she were a pig, or a hen, or merchandise. O, how can a poor slave husband or father stand and see his wife, daughters and sons thus treated.

I saw there, after men and women had followed each other, then--too shocking to relate--for the sake of money, they are sold separately, sometimes two hundred miles apart, although their hopes would be to be sold together. Sometimes their little children are torn from them and sent far away to a distant country, never to see them again. O, such crying and weeping when parting from each other! For this demonstration of natural human affection the slaveholder would apply the lash or paddle upon the naked skin. The former was

Page 15

used less frequently than the latter, for fear of making scars or marks on their backs, which are closely looked for by the buyer. I saw one poor woman dragged off and sold from her tender child--which was nearly white--which the seller would not let go with its mother. Although the master of the mother importuned him a long time to let him have it with its mother, with oaths and curses he refused. It was too hard for the mother to bear; she fainted, and was whipped up. It is impossible for me to give more than a faint idea of what was enacted in the town of Natchez, for there were many slave pens there in 1827. For some reason or other, which I never knew, I was sold first. A hellish, rough-looking, hard-hearted, slave-driving slaveholder, by the name of Rocks, bought me from T. L. Pain, Denton & Co. We were delayed a few days before we got a boat for the residence of Mr. Rocks. I had an opportunity of seeing the distress of the poor slaves of Natchez; but in a few years afterwards God visited them with an awful overthrow. A dreadful hurricane destroyed houses and boats of all kinds, and many lives of nobles were lost in oblivion.

Page 16

CHAPTER V.

ARRIVING ON THE COTTON FARM--RUNNING AWAY--GETTING INTO JAIL--AWFUL WHIPPING--LABOR, FOOD, CLOTHING--HARD TIMES.

When I arrived on the farm, and beheld the way they were fed, worked, clothed, whipped and driven, my poor heart faltered within me, to see men and women reduced to the hardships of cattleism. Yes, yes! I sat down by the Mississippi River and wept. O, I wept when I saw the holy Sabbath desecrated. The only money I possessed was one dollar. With this I purchased a Bible, but it was taken from me and torn up, and I was whipped for reading it. We had no preaching or meeting at all--nothing but whipping and driving both night and day--sometimes nearly all day Sunday.

Possibly the reader may imagine my feeling, I cannot describe them, when I remembered old Virginia, the place of my birth, my mother's house, the cabin, the grove, the spring, the associates, the Sabbath enjoyments. I felt that I was like the children of Israel when they were taken down into Babylonian captivity. They desired of me an old Virginia song, but how could I sing a song in a strange land. O, I would sit alone and weep, cry, mourn and pray. Far, far away, I was once free--now kidnapped and sold into a strange

Page 17

land, and never expecting to be released until death should set me free again.

I made up my mind to run away, and set about making preparations. My plan was to steal a skiff, as I lived twenty miles above Vicksburg, on the west bank of the Mississippi river, which was deep, wide and rapid, and make off down the river until I got to Vicksburg, or get on a steamboat going up the river. But, being ignorant of important facts, my plan did not work at all, for I did not get as far as Vicksburg before a parcel of "Northern men with Southern principles" assisted me to town and put me in jail; they were Indianians.

In a few days my master came down, put irons on my hands and feet, and laughed in anger at my calamity. He took me back upon the cotton farm, where he with three or four others, stripped me stark naked, or divested me of all my apparel, drove down four stakes, about nine feet apart, then (after I was tied hard and fast to the cold ground) with a large ox whip, laid on me (he said) five hundred lashes, till the blood ran freely upon the cold ground and mother earth drank it freely in. I begged, mourned, and cried, and prayed; but all my lamentations were only sport for him; he was a stranger to mercy. My pen would fail here to describe my agonizing feeelings and I must leave the reader again to imagine my suffering condition. At the close of this brutal punishment he called for some salt brine, of the strongest kind, and had me washed down in it. O, that, with the whipping, was another hell to undergo. He at last let me up in my chains, and put me to work at hard labor, on corn and water.

Now, hear what our food was. We were called up on Sunday evenings, and had a peck of corn measured to us, shelled, or enough corn to make a good peck, two or three

Page 18

pounds of pork or beef. This was our allowance for a week; but to continue the punishment for my running away he would not allow me any meat for several weeks, and kept me in chains some two months, this was to cow me down in degradation like the rest of the slaves, which was hard to do.

On this farm they had a large coffee mill on which we might grind our corn, or beat, boil or parch it. This had to be done between two days, or we must go without eating the next day. Here I wish to remark; that I worked hard on my allowance of corn or dry bread for several weeks. There being a large lot of chickens on the farm, I determined to kill and cook one, to eat with my bread and make it go down better. I had eaten only a part of the fowl when my master was told by some of the other servants that I was "eating up all the chickens on the place!" My master seized me and dragged me out of the cabin, tied me down to the same stakes which had witnessed my agony on a former occasion, and gave me one hundred lashes--he said. I have no recollection of eating any more chickens while I lived in the State of Mississippi. But my appetite for such food was not destroyed by my master's cruelty to me, and I have enjoyed many a meal of such innocent fowls since I left there.

It should be remembered that slaves are sometimes great enemies to each other, telling tales, lying, catching fugitives, and the like. All this is perpetuated by ignorance, oppression and degradation.

We were obliged to work exceedingly hard, and were not permitted to talk or laugh with each other while working in the field. We were not allowed to speak to a neighbor slave who chanced to pass along the road. I have often been whipped for leaving patches of grass, and not working fast, or for even looking at my master. How great my sufferings were the reader cannot conceive. I was frequently knocked

Page 19

down, and then whipped up, and made to work on in the midst of my cries, tears and prayers. It did appear as if the man had no heart at all. My sufferings while obliged to pursue. my labor, picking cotton, were too intense for my poor brain to describe, and no one can realize such bodily anguish except one who has passed through the like. I was whipped if I did not pick enough, or if there was trash found in it. The most of slaveholders are very intemperate indeed. My master often went to the house, got drunk, and then came out to the field to whip, cut, slash, curse, swear, beat and knock down several, for the smallest offence, or nothing at all.

He divested a poor female slave of all wearing apparel, tied her down to stakes, and whipped her with a handsaw until he broke it over her naked body. In process of time he ravished her person, and became the father of a child by her. Besides, he always kept a colored Miss in the house with him. This is another curse of Slavery--concubinage and illegitimate connections--which is carried on to an alarming extent in the far South. A poor slave man who lives close by his wife, is permitted to visit her but very seldom, and other men, both white and colored, cohabit with her. It is undoubtedly the worst place of incest and bigamy in the world. A white man thinks nothing of putting a colored man out to carry the fore row, and carry on the same sport with the colored man's wife at the same time.

I know these facts will seem too awful to relate, but I am constrained to write of such revolting deeds, as they are some of the real "dark deeds of American Slavery." Then, kind reader, pursue my narrative, remembering that I give no fiction in my details of horrid scenes. Nay, believe, with me, that the half can never be told of the misery the poor slaves are still suffering in this so-called land of freedom.

Page 20

CHAPTER VI.

RUNNING AWAY TO NEW ORLEANS--CAPTIVITY SCENES--WORK, WHIPPING--

RETURNED IN CHAINS, ETC.

Some three or four years had now elapsed, and I had become a man in age, and was nearly or entirely acclimated to the country. I concocted another scheme for running away; for the spirit of freedom still burned within me. My plan at this time was to write myself a pass down to New Orleans, and when I got there, to take a ship to New York or Boston. This would have been very good had I succeeded; but it did not work well, as the sequel will show. I made all my arrangements secretly. My bread, clothes, and small draft being ready, and the night, with the appointed hour, having arrived, with a heavy heart and bewildered mind I stepped into my boat and left this gentleman slaveholder the second time. I wrote a pass to New Orleans, but I fell in with a white man on my journey who promised me his assistance. But there are too many white men in that country who are deceivers--instead of helping me he put me in jail; then went up the river, let my master know of my capture, and got the reward--some hundred or more dollars.

While on my journey down, and at New Orleans, I saw scenes indescribable. I could hear the whip long before day and long after dark, on the backs of the poor slaves. It seemed to me that I came out of the frying pan into the

Page 21

fire, for here I saw them driven and whipped, nearly naked, with a little rice and molasses for their food--no meat except they stole or took it--and very little time to eat it. Some say the slaves steal, but I do not consider it stealing when a person eats, where he labors without compensation both night and day. I was thrown into the calaboose to suffer; I was put on the streets to labor with hundreds of others, with a chain locked to my leg. Here I saw about three hundred colored men in chains or in like situation with myself. These men had been employed on ships, schooners, steam and flat boats by white men from Boston, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Louisiana, Wisconsin, Illinois and Michigan; but when they got to New Orleans they were imprisoned in chains, whipped, starved and driven like oxen, because the Lord had made them black. While this was going on among the men, I saw many likely women wearing hobbles and an iron collar around the neck, with long horns of iron attached to the same. O! the horrors of Slavery. The reader may imagine how I felt about this time, confined every night, awaiting the arrival of my master.

I will now try to describe the scenes in the calaboose whipping room. They have a large, strong ladder, with ropes at each end and one in the middle. The subject to be whipped is divested of wearing apparel, and made to lay down; if he refuses to do so he is knocked down, and by the time he recovers he is stretched out and tied fast to the ladder, with the rope tight across the middle of the body. Then the fourth man lays on with the whip, paddle, or whatever he chooses. In this way perhaps ninety or a hundred are whipped every day, while begging, crying and screaming does no good. A little after daylight the whipping begins, and continues until late in the afternoon. Many of the chain

Page 22

gang are whipped, and many of the citizens send their slaves there to be whipped, and pay for it.

It seemed as though all the beef heads in the city were collected and brought there, boiled and chopped into hash by an old colored man, then dipped out with a ladle and divided among all hands, with a small loaf of bread. The women were stripped and whipped the same as the men, in the same room and by the same men. These are colored men, ordered by white men who stand by to see it well done. If there is anything like a hell on earth, New Orleans must be the place. Filth and vermin were in abundance.

Many white gentlemen--or white fiends in human shape--would send their women and girls here to be whipped because they would not gratify their hellish passions. Many of them; to my knowledge, have been brought here from Kentucky, Virginia and Tennessee, and whipped until they yielded; then by debauchery and incest they have become more loathsome and degraded than the brute creation. I have known men in different parts of the South to make colored men get out of bed and go home, while they take their place and cohabit with their wives. I have often known them to sell their cousins, brothers, sisters, sons and daughters. It is certainly a great sin, and men who will do these things are capable of committing the most atrocious crimes.

Page 23

CHAPTER VII.

MY RETURN FROM NEW ORLEANS--WHIPPING--WORKING--CONDITION OF A SLAVE SOLD--HARD MASTER, ETC.

I remained in New Orleans about three months, when my long-looked-for master arrived. I was very glad of this, for I wished to change my location, let the consequences be what they would. He saw the calaboose was so well arranged for whipping that he paid and had me whipped, in the room and on the ladder where the blood of hundreds had flown like water. O! that whipping. It was equal, in severity, to any I had received in former days. Sore, distressed and in irons, he again brought me home. He would not give me anything to eat on the boat; but, bless the Lord, I fared very well. After arriving home I wore those irons many months, but on taking them off he treated me a little better. In process of time, however, we had many serious difficulties. He whipped me again and again; kept a pair of handcuffs for my poor limbs, which soon became as common as a pair of gloves on a frosty morning. My life, I must truly say, was a terror to me. Many a day have I worked without food enough to sustain my feeble body. I can show scars which cannot fail to convince the most sceptical, of the ill-treatment of the colored man in the South. Finally I was sold by Mr. Rocks to Mr. G. B. Rogers, for seven hundred dollars. He appeared at first to be a kind hearted, friendly and religious man, of the Baptist creed. His wife and her family were

Page 24

Baptists. We moved on smoothly for a short time, then devilment began to show itself in him. He began to whip and drive all around him at a monstrous rate. His good words and deeds all left him; his humane feelings were all absorbed in his avaricious pursuit of wealth. He kept a close watch over his slaves by night to keep them at home. I wished at times to visit other families, and we had a great falling out about that; he jailed me; handcuffed me; whipped and abused me. Surely, he had more regard for the Sabbath than others I had been with; he also gave us better food and more of it at first, but he had some awful bad traits in his character. I have known him to make four men leave their wives for nothing, and would not let them come and see them any more on the peril of being shot down like dogs; he then made the women marry other men against their will. Oh, see what it is to be a slave? A man, like the brute, is driven, whipped, sold, comes and goes at his master's bidding.

After the lapse of about five years this gentleman sold me to Mr. Hudmon for a thousand dollars on credit. He sold me to a Mr. Shephard, who kept me about two months, and then sold me to a Mr. Hamlin. Mr. H. was a great gambler, and I never knew when I was safe. I would often tremble when I laid down, for fear I would have to change in the morning. Sure as I live, one morning when I was called up, I was sold to a young Mr. Hammond. He in turn sold me to a widow lady, Mrs. Hampton. Two or three of these last mentioned men were very good to me; they had nothing for me to do that was very hard. The old widow was the worst old lady I ever saw. She whipped severely, or had it done by her overseer. She worked us very hard, and made him follow us close all day with whip in hand.

Page 25

CHAPTER VIII.

PUNISHMENT, SUFFERINGS AND DEATH OF SLAVES--ADVENTURES, ETC.

I now wish to state some of the dark deeds and wonderful workings of Slavery in the State of Mississippi, which will introduce some important incidents of my past life in a manner which may be found of interest to the reader.

I once knew a colored man by the name of Branum Harris; his wife's name was Amy, and his overseer's name was Showers. Although they came in late at night from their labor, and were of course weary, they had to prepare their provisions for the next day ere they slept, or go without. The overseer was not to furnish them with cabins. One night their child was taken very ill, in consequence of which they were delayed a little after the rest of the hands had gone to work. As they (Harris, his wife and wife's sister) were passing the overseer's house, the overseer said to the women:

"Stop! I will give you two a whipping this morning for being so late."

This was just after daylight.

"O," says Branum, "our child has been sick all night. O, do not whip her this time."

"Stop, sir!" said Mr. Showers, "I will give you a flogging this morning."

He did not stop, and the overseer leveled his gun and shot him down. He then whipped the two women awfully.

This same man run a slave into a gin house full of cotton,

Page 26

which caught on fire and burnt down with the slave in it. This unfortunate victim was buried in the same grave with Branum. This occurred on Dr. Harris's farm, not far from Vicksburg, Mississippi, and this overseer was a Baptist deacon.

Another overseer on the same farm, a religious man, shot a colored man by the name of Enoch because he worked his garden patch on Sunday. This overseer's name was Mr. Knox.

I knew another colored man by the name of Givens, on the same farm, who was shot by a white man.

These acts, heinous as they are in the sight of God and man, were considered right, and therefore nothing was said; not even in the church to which they belonged. It seems, truly, as though there was nothing too bad for some slaveholders to do.

I saw Mr. Hudmon, an overseer, whip a very nice colored man one hundred or more lashes, and until the blood flowed down to the ground; he then asked him if he was mad. He, in pain, was slow to answer. He again commenced, and whipped him until he made him laugh. The reader may imagine what kind of a laugh it was.

Christian reader, I ask you to look at these facts, and answer before God the question of right and wrong. Then, if your conscience tells you that human bondage is a great sin, and I think it must, why will you not turn and plead for the suffering millions of your fellow creatures in the Southern States?

It is almost impossible for slaves to escape from that part of the South, to the Northern States. There are a great many things to encounter in escaping, vis: large and small rivers, lakes, panthers, bears, snakes, alligators, white and black men, blood hounds, guns, and, above all, the dangers of starvation..

Page 27

There was a poor slave by the name of Phill Sharp, who ran away from his master, Mr. Beacher, who resided near Vicksburg. His master had bought him of a trader from Tennessee. Sharp had left a wife there whom he dearly loved. His master continued to flog, drive and starve him, and he made up his mind to escape, and, if possible, see his wife once more in this life. Saturday night, the time he had fixed upon for leaving, arrived, and although the rivers were high and the weather warm, he concluded to travel by night and lay by in the day time, in the swamps, which are very dismal. After swimming rivers and passing through many difficulties, he arrived at a small lake about a quarter of a mile wide. He plunged in, and when nearly across he saw a large panther, on the opposite bank, awaiting his arrival. He paused a moment, but on looking back he saw a large alligator, with his month wide open, pursuing him. Here was a horrid dilemma. What to do he did not know, but there was no time to be lost. He swam on across, for he thought he could do more on land than he could in the water. Just as he got near the shore the panther made a spring at him, but missed his prize and lit on the back of the alligator. "Then," said he, "the two had an awful fight, but I did not wait to see which came off best."

He was espied and chased by dogs a long distance out of his way. One night he discovered a horse at large, and believing it no sin to take such means to escape, captured the beast, made and put on him a bridle of bark, and then took passage on horseback. He proceeded on his way until a very late hour, when he dropped into a sweet sleep. He knew not how long he slept, but when he awoke and became conscious of his situation, judge of his surprise at finding that the wicked old horse had turned around and come back to the same bars that he had taken him from. It being broad day-light

Page 28

and near a small town, he had to make haste to release him. He had to lay all day under some large slabs of bark near by, without food or water. Some huntsmen sat down on the bark to rest, and remarked that the school boys had a very nice little house made of them. He thought they might have heard his heart beat if they had listened. When night came on again he thought he would try his feet, so he traveled on a short distance and stopped at a farm house to get something to eat; being by this time very hungry and much fatigued. It was raining quite hard at the time, and very dark. He called at a place where the house was on a little rise of ground, and had a low fence enclosing the dwelling and kitchen separate. At the door of the kitchen he met the cook--a colored woman--and asked her to give him something to eat; stating at the same time that he was a runaway slave, and most starved. She said she would supply him if he would wait her return. Just as she got to the house she said, "Master, master, here is a runaway at the kitchen." The master sprang up, called his dogs and set them after him. He broke for the woods, but in looking back for the approach of the dogs he forgot the low fence that surrounded the place and run against it, and down it came with a crash. He succeeded in loosing the dogs and made his escape. This is the

Page 29

way the poor colored people are taught to betray each other for a good name, or a little tobacco, or a few pounds of meat. He traveled on that night and was finally successful in obtaining something to eat." A few days previous to his crossing the line into Tennessee, he met two white men, both of whom had loaded guns, and ordered him to stop. He knocked them both down, and proceeded on his way with a trembling heart. Eventually he had the good fortune to see his wife once more, then passed on through Indians into Ohio. This poor man is one that came through safe; but few there are who are so successful.

But to proceed with my narrative. It was as common for the widow Hampton to have her men and women stripped by the overseers before her eyes and whipped naked, as it was to eat. She had eight or ten runaways in the woods constantly. She gave us very little to eat, and we had often to steal or take what we had. We were compelled to work nearly all day every Sunday. A great deal of whipping had to be done on Sunday, for offences committed during the week. She owned hundreds and hundreds of acres of, land, and about one hundred and seventy slaves. She allowed no preaching nor bibles on her plantation, and prohibited all communication between other plantations and her own. She always had her negro cabins well watched, and left nothing undone where devilment was on hand.

I saw that my doom of distress was fixed. My life was indeed a burden to me; I knew not what to do. When I thought of my previous life in old Virginia, my mother and friends, my poor heart would sink within me, and I could but exclaim, with Paul, "O, wretched man that I am; who shall deliver me from this body of death." I have often wept in solitude over my condition, finding no comfort or encouragement save in any pleadings with God. I had a confidence in

Page 30

the Allwise Disposer, but I was prone to inquire of Him why I was thus left to suffer and endure such awful torment.

Every Christian who has passed through affliction, has been inclined, I doubt not, to inquire of his God the reason of all his torments, and I know that some have exclaimed, "O God, why forsakest thou me?"

But there is most precious consolation in the memory of all His blessings and deliverances, and the hope which is built up in our become by His promises. We must remember that

"He doeth all things well."

I again made up my mind to run away, let the consequences be what they would. Patrick Henry's words became my motto, via: "Give me liberty or give me death." I set about making my arrangements for the journey. I was some fifty miles off from the Mississippi river, in a thickly settled country, and surrounded by the worst of white and colored people. My plan was to write, myself a pass, for which I knew I would be often asked. How to do this was the point. I had no pen, ink or paper, and in a place where I dare not ask for it, for fear of detection. No one knew that I could either read or write; this was very fortunate for me.

Page 31

CHAPTER IX.

RUNNING AWAY FROM MRS. HAMPTON--PERIL ON THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER.

Being now fully resolved to put my trust in God, fear no danger, and travel from the South to the North in search of light and liberty, I ventured to ask a house servant by the name of Dick for the necessary material, with which I wrote myself a pass to Vicksburg, where I thought I might obtain a boat. I knew the widow had a number of men in the woods in search of runaways, and she would not make much fuss after me; probably thinking I would come back in due time to receive my whipping and go to work; but she has died much deceived. I was very well known in Vicksburg, for I had been in jail there seven or eight times, and as many knew I could both read and write, my case would be very critical. But as nothing ventured nothing gained, I was determined to try. I also knew that for a colored man to make an application for a passage up the river on a boat without the voice of some white man, would be looked upon with astonishment, and a close examination would follow.

July 2d, 1836, was the day I had appointed, and just before daylight I started. I arrived at the ferry--eight miles from home--passed my examination and went on my way. I met a number of white men, with a trembling heart, who, after examining my false pass, permitted me to go on, although they said they thought it was a forgery. I arrived at the

Page 32

river after seeing several old colored friends. I was asked, by some of the whites, what my business was in those parts. I told them I was a-going to cook a 4th of July dinner. I asked at the boat for a passage up the Mississippi to Louisville, Kentucky. The mate told me to show my pass to the clerk before leaving the port. I told him I would; the reader may imagine my feelings. I never spoke to the clerk, as God would have it. It must have been the wonderful workings of Providence that brought about everything for my good and His own glorification. I saw no one that knew me, although I had resided within three miles of the town for about five years. I saw on the boat about sixty or seventy slaves, who were going up the river with their master to the State of Arkansas, to open a farm. I sat down in their midst; the boat raised steam and pushed out from shore. O, how glad I was to see her fast running out of sight of the town and the old jail that I had often been locked up in. When the old town had been lost in the distance, and the grim shadows of fear had partially vanished, my heart overflowed with joy, that thus far I had proceeded on my journey without molestation. I thus passed on peaceably from day to day.

I had made a confident of the steward, a colored man, who

Page 33

was true to his trust. When the boat had run about eighteen hundred miles up the river, the master with his slaves got off, and I could no longer pass under their protection; but was left to devise and seek some other plan to elude detection by the ever suspicious persons who journeyed with me. My peril began now to be more imminent, but with a heart borne up by the blessed hope of deliverance from cruel, life-torturing bondage, I trusted in the Great Father above, and could but pursue my way.

In two or three days after these slaves had left, the Captain came to me and said he thought I belonged to that gang of slaves. I told him no. He then asked me who I belonged to. I told him I belonged to Mr. Crawford, of Louisville, Kentucky.

"Have you any pass?" said he.

"Yes, sir," I answered.

"Show it to me."

He looked it all over, and throwing it down he said:

"You are a runaway, sir; that pass is forged. Have you any more papers, sir?" says he.

"Yes, sir; I have a letter to my master."

"Go get it, quick, sir."

I handed him the papers, with a trembling heart. He took it and looked it over carefully, then throwing them down, he said:

"You scoundrel! these papers are all forged. How dare you get on my boat?" You are running away, sir. I will put you in jail as soon as I arrive in Louisville."

Think, friendly reader, how I felt about this time. The thoughts of being returned into slavery, with the chains upon my limbs and the whip flourished with mad vengeance over my head--the cries of agony, wrung from tortured victims, ringing in my ears--oh, 'twere worse than death.

Page 34

Two men were placed to watch me night and day. I was not permitted to carry wood as usual from the shore. Thus I traveled on up the Ohio river, trembling and spirit-worn.

The night previous to their landing at Louisville--where I was to be imprisoned and again sent back to slavery--my watchers kept a sharp lookout at every landing, to see that I did not escape. While they watched me, I also kept an eye to business.

I had procured a large knife previous to my starting, knowing it to be an indispensable article to a man in my situation. The captain said to me, several times, that if he thought I had any notion of giving him the slip, he would iron me; but I made all manner of fair promises, and in that way kept my limbs free.

It grew late; the cocks began to crow at the approach of morn. Indiana was on one side and Kentucky on the other. Here was freedom, and the time had come that to get free, as I wanted to, I would have to make another bold strike. How to manage it successfully was a question hard for me to solve. The Ohio river was quite high, the night dark, and the boat running at her highest speed. How I was to get to the shore of Indiana had been my daily study for several days. I could not swim, neither could I fly, nor walk on the water. O, what shall I do? was the constant, unanswered query of my poor heart. A thousand thoughts would flash across my mind in a moment, for my time was now getting very short.

I have, in my lectures, of late years, asked a thousand people at once how I got off that boat, or watery prison, but none could tell me. Now, gentle reader, I will tell you how I got off. Just before day, the mate--one of the noble watch men--came to the after part of the boat and said:

"Where is that runaway?"

Then I snored as loud as a hog in frosty weather. In a

Page 35

moment he turned and went toward the bow or fore part of the boat, when I quickly threw my little bundle of clothing into the yawl boat, and jumped after them. With my knife I cut the rope that secured the yawl, and as quick as thought I was fast gliding astern. The boat continued on her course, while I, unobserved, turned my craft for the Indiana shore, where I landed in about ten minutes from the time I left the old floating prison house. The splendid boats which navigate that beautiful river are often styled "floating palaces," but this, to me, was more like a dungeon:

O, then I had a time of rejoicing. I laughed and cried. I tried to pray and return thanks to the Lord for His goodness to poor me. I am not able to express my feelings then or now. When I remembered that just a few days ago I was down in a slave state, under the lash; that only a few moments ago I was a slave on yonder boat, but now free! free forever! O, I was like the Indian who went out and painted himself, and, returning to camp, his own dog bit him; he said, "Sure this is not me." Those were my feelings, truly. O, reader, I can never forget that morning.

I took up my little bundle of clothing and traveled on. In the State of Indiana I felt light and comfortable; the small obstacles I had to encounter I did not fear.

I arrived in Madison City, Indiana, on the 15th of July, 1836, weary in mind and body, but joying in my escape from tyranny and persecution. My funds in pocket amounted to one dollar, which I advanced for my board. I sought employment immediately, and soon engaged to work for Messrs. F. Thompson and E. D. Luck, carrying the hod for a dollar a day. This, of course, was new and rather severe labor for me at this time; but it was far better than toiling in the cotton or corn field, for a reward of a scanty meal of corn and the lash. My freed spirit could now sing a new song,

Page 36

where there were no wailings nor cries of anguish. I could go and come as I chose. Blessing my Maker for this dear gift of liberty and release from cruel torture, I began the laborious occupation of lifting mortar and brick.

At first I was very awkward, and became the butt of considerable ridicule among my colored companions. But my determination to persevere and earn my money by diligence, helped me through the initiation with wonderful success. In a few weeks I had gained the confidence and esteem of my employers, and was otherwise rewarded. My wages were better than those of other laboring men in the town. Among both white and colored citizens my credit was in fair repute, and my honesty and steadiness of purpose were acknowledged.

There were two things which I desired, namely: Knowledge of books, and the truths of Christianity. Reading I attended to assiduously, and made some progress in the hitherto hidden paths of learning. The word of the Lord was daily searched, and His mighty truths awoke a new ardor in my soul. I hungered and thirsted after righteousness.

In the fall of this year, duty prompted me to unite with the Methodist Episcopal Church. The society worshipped in an old log tenement in the northern part of the town. The members numbered only eight or nine. One day we needed some candles to light our primitive meeting house. My first impulse was to purchase the articles with my own money. I had but a solitary dime. I remembered the promise of the Saviour, "He who giveth to the poor lendeth to the Lord," and determined to test it. With that only dime I bought candles for the meeting, and awaited the result. I was most pleasantly surprised, the following day, by liberal donations of dimes from sympathetic brethren. I even found money while digging, and by the following night I had the nice little sum of seven dollars in small money.

Page 37

Ever since that memorable event I have felt a most hearty willingness to trust in the Lord. To-day the faith lives within my breast as brightly as ever, while I wait upon His blessed word. The poet eloquently expresses my impressions in the hymn beginning--

"God moves in a mysterious way,

His wonders to perform;

He plants his footsteps in the sea

And rides upon the storm."

My brethren and sisters in the church began early to manifest their regard for my good endeavors, and I hoped to soon become influential in the service of Christ.

The next year, 1837, I was married to Miss Sidney, of Pennsylvania. She was a worthy, industrious and estimable woman. Although her health was poor, and she suffered much, she was ever faithful in her duty to her husband. She was a member of the Baptist denomination at the time of our marriage, but soon after united with the Methodists, and went down to the grave hoping in the resurrection. She left this weary world forever on the 9th day of January, 1849.

While she lived we labored together, and prospered. We felt that our efforts to do good had not been in vain or unrewarded. So it must be with those who seek after the blessings of true religion, take up their cross and follow the meek and lowly Jesus.

There was unity of spirit in our little church, and each sought to assist a neighbor. Through industry and diligence we were enabled to build a small frame building for our church edifice, on Walnut street. In this I bore a fair and rather conspicuous part. I was favored both temporally and spiritually. I was enabled to build a house in town, and also purchased a small farm in the country. A year after, I bought another farm--and my possessions were estimated at

Page 38

nearly two thousand dollars. Even a third farm was soon added to my estate, which I improved and cultivated.

Thus I prospered most wonderfully in earthly acquirements, and while favors were heaped upon me in my temporal affairs, I felt that my spiritual progress was onward and upward. I was promoted to the office of class-leader in the church, and head steward. Two years after this, I procured a license to exhort, and in two years more I had permission to preach the gospel of Christ. On all occasions I betook myself to prayer and diligent study of the Scriptures. Fifty dollars was invested in valuable works on the Bible, which made my library superior to any that belonged to my classmates. In two years more I was duly elected to the charge of the Walnut Street Church in our town, which I endeavored to serve with Christian fear, always keeping in view the glory of God, and Christ, my guiding star.

Those who favored the "peculiar institution" sought to make me promise to assist no more fugitives in their flight, as they should chance to pass that way. But their attempts were vain, for how could I do this and be a consistent follower of the instructions found in my Bible? In the good book we are commanded to feed the hungry and clothe the naked, and no mention is made of color or condition. Besides, I had learned by sad experience how the poor hound-driven slave pants for freedom from such inhuman bondage--how the heart is made to leap with joy when a friend indeed offers the protection sought. No, my whole duty must include this kindness to my unfortunate fellow beings. And while I live I hope to work in the glorious cause of charity and beneficence toward God's afflicted children.

My two wagons, and carriage, and five horses were always at the command of the liberty-seeking fugitive. Many times have my teams conveyed loads of fugitive slaves away while

Page 39

the hunters were close upon their track. I have carried them away in broad daylight, and in the grim shades of night. I have scouted through the woods with the fleeing slave while the barbarous hunters pursued as if chasing wolves, panthers or bears.

That old town has known many a bloodthirsty chase, and has been the home of numerous negro-catchers, both white and black. But many of them have gone to their long home--the "bourne from whence no traveler returns." I knew them well, and their names I might disclose; but I forbear. Surely they will all meet their reward in the great day.

Fifteen years ago some men in Kentucky had a great desire to catch me within the limits of their State, as they averred that I had been guilty of assisting negroes to escape from their masters. But I kept out of their way until December 12th, 1856.

For the information of certain people who may feel interested, I will here state, that although I have assisted a hundred colored people within the State of Indiana, I have never helped one to get across the Ohio river from Kentucky. They have only been aided by me when they were in Indiana, and in such manner as giving them food and instruction in the course to pursue, &c.

I am sorry to state that now the colored people are rewarding me by evil treatment, discrediting my statements and persecuting me in various ways. I could inform the reader of several instances of persecution while pursuing my good intentions, but fear I may be deemed guilty of a bad return myself.

I will still put my trust in God, nor allow the threats and wicked acts of my fellow men to deter me from deeds of virtue. For if God be for me who can be against me?

Page 40

I could mention many instances of narrow risks of life and limb which I have run, with names of persons and places, but I know I should not be deemed a forgiving creature.

With much praying and faithfulness I continued the allotted time to discharge my duty to the best of my ability, at the Walnut street church. My successor was Rev. B. Mark Smith.

My time was now pretty fully employed in drawing wood with two teams, besides other services of a like character; and these furnished a fair amount of money necessary for the maintenance of our family. My credit had grown to a most gratifying condition, the bankers being ready and willing at any time to lend me money.

At length I came to the conclusion to withdraw from the Methodist Episcopal Society of whites, and join what is now the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The charge of a circuit was immediately given me, and I again went forward in the work of the ministry. My labors seemed to be blessed of the Lord, for many were added to the church and many induced to follow the meek and lowly Jesus. Great happiness was my portion; my heart would leap with joy, and ofttimes have I been ready to exclaim, Glory to God as I thought on His goodness and loving kindness.

I arranged and directed Sabbath Schools, as they were appointed, and the fruits of my labors were made apparent in the good conduct of the precious pupils who listened to and honored me. The support afforded me through my circuit was meagre, though the range was quite extensive.

I labored diligently, nor spared any trouble, as I sought to benefit immortal souls.

A camp meeting, at which I officiated, was held at Vernon, Indiana, and was the closing scene of this eventful year.

Page 41

Since then I have not had charge of any congregation, though I have not neglected to serve that being who giveth every good and perfect gift.

Mine has been a changeable life--a pilgrimage of suffering, now and then brightened by a ray of joy and earthly happiness, but generally clouded with terrible feelings. But you shall know more of scenes in my pathway.

Page 42

CHAPTER X.

BUILDING CHURCHES, ETC.

At the time I became connected with the A. M. E. Church, the congregation had a church building of their own to worship in. I had built a parsonage house for the Walnut Street Church with my own means, and I now decided to erect a building for this society to worship in, and rent it to them. The object was easily accomplished. The congregation made many efforts to build a church for themselves, but failed. At last they agreed to accept my direction in the matter, and the house was soon erected, which is now the Fifth Street, or the Brick Church. The building was not entirely completed until during the administration of Rev. E. Weaver.

At the close of the term of my ministry, I determined to give up farming and to turn my attention to the business of grocery keeping, huckstering, &c., in which I engaged for a time. But this soon proved a ruinous move for me. My native benevolence would not permit me to treat my customers as if there was a possibility of their cheating me out of my dues, and I was always too willing to trust to their honesty. Patrons were not few, and I served them readily, until there was a necessity for collecting the straggling debts among the numerous delinquents. This proved to be the

Page 43

most difficult part of my business, for, while some had already left the town for parts to me unknown, many still remained who pleaded poverty and inability to pay. I am sorry that I am obliged to record dishonesty of my brethren, but certain it is that their acts convicted many of violating the laws of duty. I was obliged to yield to the necessity of closing up my trading business. Some of those who had been only too glad to be served with things for the household, and allowed to wait until. I was nearly involved in debt, were the most unkind to me when the time came for settlement. There were debts of fifty to seventy dollars, the demand for the payment of which was the cause of many hard words from the debtors, who would often even manifest a disposition to fight me.

I am well aware that during those trials I was guilty of some evil thoughts and misdeeds, and for which I have been truly repentant since. But it was a severe struggle to overcome the excitement caused by such treatment and ill success. I hope that I may be forgiven, at least by my Heavenly Father, if not by my fellow men.

When I review the scenes of my life, and bring to mind the services I have rendered my colored brethren--even risked my life for them--the remembrance of their unmanly treatment of me, stirs up the sorrow of my heart. O God, wilt thou instruct and lead them from the evil of their ways, and keep me still within thy arms?

I eventually removed to Indianapolis, Indiana, where I engaged in business for a time. An agency was entrusted to me here to raise money for building a church in Louisville, Kentucky. When one hundred dollars had been obtained and handed over I found that the demand was too great for me to supply, and declined the agency. Since that experience I have been simply agent for myself, and found ample

Page 44

employment for labor and money. My trade now was in books, to some extent, and very successful too.

For about fifteen years I have preached and lectured, and I can but acknowledge the goodness of the Great Shepherd to-day--that He is with me still. As I pen these lines the day is breaking. O that God would cause the daylight of religion to break upon many souls. I feel that I am too much like Peter, who chose to follow his Lord afar off. But still I can say, with the Psalmist,

"The Lord is my Shepherd, I shall not want; He maketh me to lie down in green pastures; He leadeth me beside still waters. Yes, He restoreth my soul; He leadeth me in the paths of righteousness, for His own name's sake. Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I shall fear no evil, for thou art with me; thy rod and thy staff they comfort me. Yes, thou anointeth my head with oil; thou spreadeth a table before me, in the presence of mine enemies. Surely goodness and mercy have followed me all the days of my life, and I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever. I once was young, but now I am old, and I never have seen the righteous forsaken nor his seed begging bread. The earth is the Lord's and the fullness thereof."

Therefore I will trust in Him, as did Job, Peter, Paul and all the Apostles of old. O, like Jonah, I can almost say "I have cried to God out of the belly of hell," for some of these jails resemble a hell, and I have been in many of them in the United States; for where the slaveholders did not put me in, these mean Northerners or Free State men, both black and white, would concoct plans to imprison me. But, bless the Lord, the old man Anderson still lives, while many of them are falling to rise no more. Yes, glory to God, I expect to shout Victory when the world is on fire.

When I look back upon my past life I can see where I

Page 45

could have lived a better man, and it grieves me to think that I am not a better man than I am to-day; but I glorify and bless God it is no worse with me than it is. Yes, I feel happy to-day that my face is Zionward, and that my treasures are laid up in heaven. I can cheerfully pray for my persecutors, and thereby do good for evil. Yes, my soul feels happy to-day. Often when I think what I have passed through, and how I now enjoy myself, I can truly sing--

"How happy are they

Who their Saviour obey,

And have laid up their treasures above.

Tongue cannot express

The sweet comfort and peace

Of a soul in its earliest love."

Or this--

"God moves in a mysterious way,

His wonders to perform;

He plants His footsteps in the sea,

And rides upon the storm."

Yes, bless the Lord, He has always stood by poor, unworthy me in all my distress. After I found that everybody appeared to be inclined to cheat me out of what I was worth, I concluded to travel over the Northern States and sell books. It would undoubtedly be astonishing to the reader to hear how many places I have preached and lectured--frequently to very large crowds. I have spoken some one thousand times. So I assure the reader I am not just scared up like a rabbit

Page 46

CHAPTER XI.

MORE SCENES OF SUFFERING AND TORTURE.

I may again ask the reader to listen to sorrowful tales, and notes of scenes which have been only too familiar to my own eyes. Some sketches I give from persons are reliable, and the sympathetic or the horror-stricken may not turn away disgusted and doubting the truth of the narrative.

I once knew a man in old Virginia by the name of Thornton, who had an old pious slave. I knew them both. This wicked tyrant practiced his cruelty in various ways. Sometimes he would strip the old slave, turn him loose in his barn and train him with a whip as if he were a dog. He would order him in words like these:

"Pass by me, you d--d rascal!"

Then as the poor slave obeyed him, Thornton lashed his naked body with the hickories. Thus he would continue his hellish sport till the poor creature had received as many as three hundred cuts.

Sam, the pious old slave, was one of the most obedient, ignorant creatures, and there was no necessity for such inhuman treatment. But, tortured thus till despair seized him, he sometimes ran away. But after he had been missing two or three days, his master would go to the edge of the woods and, with vengeance in his tone, bawl out--

"You, Sam!"

Page 47

Poor Sam, frightened into obedience, would yield, answer, and then return to the clutches of his wrathful master.

But, long ago, Thornton went to his reward in the regions below, and we trust his faithful slave has exchanged this earthly existence for one of bliss, singing praises unceasingly with the host above.

In the family of another well known hard-hearted slave owner, who whipped and drove his slaves like dogs or cattle, for about sixty or seventy years, there lived a colored man by the name of Joe.

One day the master was taken sick and nigh unto death. His preacher or spiritual adviser was sent for, and while attending there the old master died.

The preacher took it upon himself to give Joe some good advice on the occasion.

"Come here, my good boy," said the pious man. Joe obeyed, when his reverence began:

"Your master is dead and gone to heaven. Your mistress is left a widow. Now, Joe, you must stay at home and take care of your mistress. Don't rob the smoke house, nor pig pen, nor hen roost, nor potato patch; and when you die you will go to heaven, where your master is gone."

"Whar?" asked Joe.

"To heaven," replied the minister.

"Aint God dar?"

"Yes, Joe."

"Don't He know ebery ting?"

"Yes, Joe."

"And He gwine to let massa come dar after he been beatin and whippin' me for fifty years? If I go dar, and massa is dar, I'll put on my old hat and come straight out of dar.' I won't stay in no such a heaven, where they let such a man as massa stay dar."

Page 48

So persisted the honest old slave, and rather puzzled the wise head of the reverend adviser.

Another savage specimen of a slaveholder, who drank liquor too freely for his own good, and whipped and drove his poor slaves in a desperate manner, I once knew of in the State of Mississippi. This monster in human shape was an outlaw who feared not God, nor regarded human beings with any degree of kindness.

One of his slaves was in the habit of running away as often as an opportunity was presented. His master tried every stratagem of cruelty to make this poor creature fear him and stay at home, but with poor success. One day the old tyrant took his truant slave to the woods, tied him to a tree, and left him to die by inches. Insects drank his blood, and he yielded at last to this horrid death.

This same fiend of a slaveholder had another slave who loved liberty better than bondage and the lash. His master hunted and caught him with bloodhounds, and allowed the dogs to kill him. Then he cut his body up and fed the fragments to the hounds.

These same dogs once attacked some children returning from school, and killed one or more.

It is no uncommon thing for slaveholders to keep such savage dogs, trained to hunt and follow the track of the poor colored fugitive, day and night, till they catch him. Men who do not own such hunters hire them for the purpose of running down God's unfortunate creatures, whose great sin among the whites is the darkness of their skin I do think that the hearts of the masters must be far blacker than the negro's skin.

Driven to the woods or swamp, the slave is obliged too often to yield and be torn by the savage dogs who gratify the vengeful dispositions of the masters.

Page 49

As I rehearse these soul-torturing, harrowing facts--these scenes of blood and butchery--my heart sickens and my blood runs cold, and I finally drop my pen while the tears of sorrow and sympathy flow. It is surely a hard question to answer--Why does the Lord thus suffer us to be afflicted, beaten, dragged and torn with anguish unspeakable, in this glorious "freo" country? His ways are past finding out.

A man by the name of Paddy, who was once employed as overseer of slaves in the State of Louisiana, related to me some of his experiences--a portion of which story I may here publish. On a sugar plantation, while employed in boiling sugar, he kept an old slave up every night, according to his master's orders, to serve him in the operations. Constant taxing of the old slave's faculties, finally used up his powers of keeping awake, and one night the old man fell asleep and tumbled into the kettle of boiling hot sugar. When found he was cooked through and through--emphatically "done brown."

The master also owned several other slaves, some of whom would escape as they found opportunity to do so. One was caught and brought home to him, when the master took him to a wood pile and chopped off one of the poor slave's legs. A physician was sent for, and the stump of a limb was done up, while the victim of such vengeful deeds was left to suffer.

Another truant slave, when brought home, was forced to have one of his eyes punched out, as a penalty for his misconduct.

Others who dared to use their God-given rights, were branded with hot irons or had their ears cropped.

As for whipping, Mr. Paddy said his employer had so much of it to do that he was forced to leave him. Mr. P. said those slaves were beaten and worked hard, and given poor food and poor clothes. Cattle seldom receive such treatment

Page 50

as did these suffering slaves. Oh, the horrors of American Slavery! I wonder if the devil can fathom the institution.

In my boyish days, in old Virginia, there lived a very rich man by the name of Garland, in Hanover county, the place of my birth. He owned a large number of slaves. His overseer's name was King, who was an awful tyrant--a monster among the negro race--whipping and driving both men and women, and cohabiting among the women, both married and single.

So Mr. King flourished for a time; but his cup of iniquity got full, and one day while he was counting rails in the woods, two brother slaves, named Humphrey and Thornton, knocked him down with their axes and killed him. Just before he expired, some little black thing or devil made his appearance and said, "If he is not dead don't kill him." They did, however, kill him and placed him on the road side. This Mr. King, they supposed, dealt with the devil, and this was his black brother, who came to relieve him. But the slaves were too strong for the devil.

For this deed the slaves were both swung off from one gallows. I saw them myself.

This King would hang his coat up in the field, and tell the slaves he would be back shortly. They would work hard while looking at his coat, although he would sometimes be twelve miles distant.

Now I wish to speak of an awful occurrence that transpired on the Ohio river. It will be remembered by early settlers of Kentucky that one Ned Stone was a great negro trader. His cruel mind did not recognize it as being a horrid crime to separate husband and wife, parents and children, etc.

This Ned Stone, after trading in slaves some fifteen years, making himself rich from the income, undertook to make a large trade in slaves. He bought a lot in Maryland, some in

Page 51

Virginia, some in Kentucky, etc., and stole some, as he usually did. He then proceeded down the river, on two flat boats, with his prizes--men, women and children--amounting to the number of one hundred and seventy-five. He passed Cincinnati; Madison, Indiana; and Louisville, Kentucky. On down he went, treating his slaves in a very cruel manner, until he got opposite Rome, Indiana.

Now I will give the statement of the colored men themselves, for I lived with them five years in slavery and hard servitude. Those colored men said they concocted a plan to murder all the whites, and then leave the boats and pass for free men in Indiana. There were about seventy-five colored men and only five whites, to wit: Ned Stone, a Mr. Davis, a Mr. Cobb, and two others. They murdered all the white men about nine o'clock. The colored men then cut their chains off, put them on the white men and sunk them in the river, and landed in Indiana that same night. In a few days they were nearly all captured and taken over to Kentucky. The white men were dragged from the bottom of the river, and the irons taken off them and again put on the colored men. Five of the blacks, who were deemed most guilty, were hung; the rest were sold for a compensation down in Mississippi.

It seemed that the judgments of God followed those poor; unfortunate creatures.

Of my sufferings in this narrative I have only mentioned one thing out of a thousand, and of the other poor slaves, only one in ten thousand that have come under my own observation. The reader will pardon my short narrative, as my recollection and time will not permit me to extend this little sketch at present. I say again, the half has not been told of my knowledge of Slavery in the United States.

I must now pass over a few years of my life while enjoying comparative peace and some, at least, of the comforts of

Page 52

freedom. The incidents during this period might not prove of interest to the readers of this narrative, and I will not detain them with details of familiar scenes. Suffice it to say, my heart grew not thankless to Him who had been my Preserver, and the blessings of freedom nourished a love for all things good.

Page 53

CHAPTER XII.

MY ARREST AND TRIAL--CHARGED WITH THE CRIME OF ASSISTING SLAVES FROM KENTUCKY.

On the 12th of December, 1856, I was in Jeffersonville, Indiana, and having been absent from home (Madison City) for some time, my heart's desire was to get to my family that night. Fearing the boat, which was at the levee, would not cross the river in its passage, I took passage on the ferry-boat and went on board the steamer Telegraph, bound for Madison. Just as I walked on, Mr. Bly, one of the policemen of Louisville, and others, bawled out and said:

"Here is Mr. Freemont!"