Toussaint L'Ouverture:

A Biography and Autobiography:

Electronic Edition.

Beard, J. R. (John Relly), 1800-1876

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Elizabeth S. Wright

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Elizabeth S. Wright, and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2001

ca. 800K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) Toussaint L'Ouverture: A Biography and Autobiography

(spine) Toussaint L'Ouverture of Hayti

Rev. John R. Feard, D.D.

372 p., 2 ill.

Boston:

JAMES REDPATH, PUBLISHER, 221 WASHINGTON STREET.

1863.

Call number E7272 (Special Collections Library, Duke

University)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- French

LC Subject Headings:

- Generals -- Haiti -- Biography.

- Haiti -- History -- Revolution, 1791-1804.

- Haiti -- History.

- Revolutionaries -- Haiti -- Biography.

- Slavery -- Haiti -- History.

- Toussaint Louverture, 1743?-1803.

Revision History:

- 2001-09-24,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-07-24,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-07-06,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-06-21,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

TOUSSAINT L'OUVERTURE:

A

BIOGRAPHY AND AUTOBIOGRAPHY.

Boston:

JAMES REDPATH, PUBLISHER,

221 WASHINGTON STREET.

1863.

Page verso

Entered according to act of Congress, in the year 1863,

BY JAMES REDPATH,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

GEO. C. RAND & AVERY,

STEREOTYPERS AND PRINTERS.

Page iii

INTRODUCTION.

THIS volume contains two distinct works,--a Biography and an Autobiography.

The Biography was first published in London, ten years since, as "The Life of Toussaint L'Ouverture, the Negro Patriot of Hayti: By the Rev. John R. Beard, D. D., Member of the Historico-Theological Society of Leipsic, etc." It had the following--

PREFACE.

"The life which is described in the following pages has both a permanent interest and a permanent value. But the efforts which are now made to effect the abolition of slavery in the United States of America, seem to render the present moment specially fit for the appearance of a memoir of TOUSSAINT L'OUVERTURE. A hope of affording some aid to the sacred cause of freedom, specially as involved in the extinction of slavery, and in the removal of the prejudices on which servitude mainly depends, has induced the author to prepare the present work for the press. If apology for such a publication was required, it might be found in the fact that no detailed life of TOUSSAINT L'OUVERTURE is accessible to the English reader, for the only memoir of him which exists in our language has long been out of print.

"The sources of information on this subject are found chiefly in the French language. To several of these the author acknowledges deep obligation.

"The tone taken on the subject of negro freedom in Hayti, by recent writers in two French reviews, is partial and unjust.

Page iv

Possibly this may be attributable to a mulatto pen. The blacks have no authors; their cause, consequently, has not yet been pleaded. In the authorities we possess on the subject, either French or mulatto interests, for the most part, predominate. Specially predominant are mulatto interests and prejudices, in the recently published Life of Toussaint L'Ouverture, by SAINT REMY, a mulatto: this writer obviously values his caste more than his country or his kind."

With this work the editor has taken the liberty of making a few verbal and other changes in the text of the opening chapters; of erasing the two elaborated guesses as to Toussaint's Scriptural studies and readings in the Abbé Raynal's philosophy; and of omitting the entire Book IV., which gave a sketch of the history of Hayti from the death of Toussaint to the reign of the late Emperor Soulouque. The alterations in the first chapters referred chiefly to statements respecting modern Hayti, with which the editor's travels and his official relations to its Government had made him more familiar than the author. Book IV. was erased because it was deemed an inadequate presentation of the history of an independent negro nationality,--not unfair, indeed, nor essentially inaccurate, but too meagre for publication in the United States where its statements would necessarily be weighed in the scales of party. It is hoped that a full and impartial history of Hayti will, erelong, be presented to the American people; until then, the sketches in the encyclopedias and the summary of Mr. Elie in "The Guide," must suffice to indicate the governmental changes that have occurred in the island. *

* The few references in the Notes to this book (we may say in passing) will lose every appearance of bad taste or of egotism, when it is stated that it is simply an unpretending collection of facts, to which no claim or pride of authorship can justly attach.

Page v

In the historical record of Dr. Beard, no changes have been made. This fact does not imply a uniform concurrence of judgment. For it is but justice to say, that, although "the blacks have no authors," they have found in Dr. Beard not a friend only, but an able and zealous partisan.

There have been three versions of Haytian history,--the white, the black, and the yellow: the white representing the pro-slavery party, the black that of the negroes, and the yellow that of the mulattoes. The abolitionists of England and America have adopted the negro standard,--refusing equally to pay any homage to Pétion, the idol of the mulatto historians, whom they call the Washington of Hayti, or to regard Toussaint as the bête noir of the revolution, or otherwise than as Hayti's hero,

"Great, ill-requited chief."

This brief statement will show that to have undertaken to present the other sides of the events narrated would have required a volume of notes.

The "Notes and Illustrations" of Dr. Beard, with one exception, have, also, been omitted, and others deemed more interesting and pertinent substituted for them.

It is from the "Mémoires de la Vie de Toussaint L'Ouverture," edited by the M. Saint Remy, whose partisan spirit Dr. Beard reproves, that the Autobiography of the great General and Statesman is taken.

"The existence of these Memoirs," he says, "was first mentioned by the venerable Abbé Grégoire, bishop of Blois, in his curious and entertaining work entitled, 'The Literature of the Negroes.' In 1845, the journal 'La Presse' published fragments of them; and at that time some persons seemed to doubt their authenticity. But, quite recently, through the friendly medium of Mr. Fleutclot, member of

Page vi

the University of France, I was enabled to obtain from General Desfourneaux a copy of these Memoirs which he had in his possession. Still later, after much research, I succeeded in discovering the original manuscript in the General Archives of France. Eagerly, and with scrupulous attention, did I peruse the lengthy pages, all written in the hand of the First of the Blacks. The emotions excited in me by this examination will be better understood than they can be described. The mind is thrown into an abyss of reflections by the memory of so lofty a renown bent under the weight of so much misfortune."

M. Saint Remy adds, that "Toussaint's cast of mind may well be judged from the fact that his own manuscript is entirely at first hand, without an erasure or an insertion."

This interesting paper is now first published in the English language, having been expressly translated for this volume.

"Are the Negroes fit for Soldiers?" Ignorant of the history of Hayti, which forever settled the question, our journalists and public men for many long months disputed it, until the gallant charges on Port Hudson and Fort Wagner put an end to the humiliating debate.

"Are Negroes fit for Officers?" We are entering on that debate now. The Life of Toussaint may help to end it. What Toussaint, Christophe, Dessalines did,--"plantation-hands" and yet able warriors and statesmen, all of them,--some Sambo, Wash, or Jeff, still toiling in the rice-fields or among the sugar-canes, or hoeing his cotton-row in the Southern States, may be meditating to-day and destined to begin tomorrow.

BOSTON, SEPTEMBER, 1863.

Page vii

- FROM THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE STRUGGLE FOR LIBERTY IN HAYTI TO THE FULL ESTABLISHMENT OF TOUSSAINT L'OUVERTURE'S POWER.

- CHAPTER I.

Description of Hayti--Its name, mountains, rivers, climate, productions, and chief cities and towns . . . . . 13 - CHAPTER II.

Columbus discovers Hayti--Under his successors, the Spanish colony extirpate the natives--The Buccaneers lay in the West the basis of the French colony--Its growth and prosperity . . . . . 22 - CHAPTER III.

The diverse elements of the population of Hayti--The blacks, the whites, the mulattoes; immorality and servitude . . . . . 28 - CHAPTER IV.

Family, birth, and education of Toussaint L'Ouverture--His promotions in servitude--His marriage--Reads Raynal, and begins to think himself the providentially-appointed liberator of his oppressed brethren . . . . . 34 - CHAPTER V.

Immediate causes of the rising of the blacks--Dissensions of the planters--Spread of anti-slavery opinions in Europe--The outbreak of the first French Revolution--Mulatto war--Negro insurrection--Toussaint protects his master and mistress, and their property . . . . . 42 - CHAPTER VI.

Continued collision of the planters, the mulattoes, and the negroes--The planters willing to receive English aid--The negroes espouse the cause of Louis XVI.--Arrival of Commissioners from France--Negotiations--Resumption of hostilities--Toussaint gains influence . . . . . 50 - CHAPTER VII.

France equalizes mulattoes and negroes with the whites--The decapitation of Louis XVI. throws the negroes into the arms of Spain--They are afraid of the Revolutionary Republicans--Strife of French political parties in Hayti--Conflagration of the Cape--Proclamation of liberty for the negroes produces little effect--Toussaint captures Dondon--Commemoration of the fall of the Bastille--Displeasure of the planters--Rigaud . . . . . 60

Page viii - CHAPTER VIII.

Toussaint becomes master of a central post--Is not seduced by offers of negro emancipation, nor of bribes to himself--Repels the English, who invade the island; adds L'Ouverture to his name; abandons the Spaniards, and seeks freedom through French alliance . . . . . 69 - CHAPTER IX.

Toussaint defeats the Spanish partisans--By extraordinary exertions, raises and disciplines troops, forms armies, lays out campaigns, executes the most daring exploits, and defeats the English, who evacuate the island--Toussaint is Commander-in-chief . . . . . 79 - CHAPTER X.

Toussaint L'Ouverture composes agitation, and brings back prosperity--Is opposed by the Commissioner, Hédouville, who flies to France--Appeals, in self-justification, to the Directory in Paris . . . . . 90 - CHAPTER XI.

Civil war in the South between Toussaint L'Ouverture and Rigaud--Siege and Capture of Jacmel . . . . . 102 - CHAPTER XII.

Toussaint endeavors to suppress the slave-trade in Santo-Domingo, and thereby incurs the displeasure of Roume, the representative of France--He overcomes Rigaud--Bonaparte, now First Consul, sends Commissioners to the island--End of the war in the South . . . . . 112 - CHAPTER XIII.

Toussaint L'Ouverture inaugurates a better future--Publishes a general amnesty--Declares his task accomplished in putting an end to civil strife, and establishing peace on a sound basis--Takes possession of Spanish Hayti, and stops the slave-trade--Welcomes back the old colonists--Restores agriculture--Recalls prosperity--Studies personal appearance on public occasions--Simplicity of his life and manners--His audiences and receptions--Is held in general respect . . . . . 121 - CHAPTER XIV.

Toussaint L'Ouverture takes measures for the perpetuation of the happy condition of Hayti, specially by publishing the draft of a Constitution in which he is named governor for life, and the great doctrine of Free-trade is explicitly proclaimed. . . . . . 134

- CHAPTER I.

- FROM THE FITTING OUT OF THE EXPEDITION BY BONAPARTE AGAINST SAINT DOMINGO TO THE SUBMISSION OF TOUSSAINT L'OUVERTURE.

- CHAPTER I.

Peace of Amiens--Bonaparte contemplates the subjugation of Saint Domingo, and the restoration of slavery--Excitement caused by report to that effect in the island--Views of Toussaint L'Ouverture on the point. . . . . . 145

Page ix - CHAPTER II.

Bonaparte cannot be turned from undertaking an expedition against Toussaint--Resolves on the enterprise in order chiefly to get rid of his republican associates in arms--Restores slavery and the slave-trade--Excepts Hayti from the decree--Misleads Toussaint's sons--Despatches an armament under Leclerc . . . . . 152 - CHAPTER III.

Leclerc obtains possession of the chief positions in the island, and yet is not master thereof--By arms and by treachery he establishes himself at the Cape, at Fort Dauphin, at Saint Domingo, and at Port-au-Prince--Toussaint L'Ouverture depends on his mountain strongholds . . . . . 160 - CHAPTER IV.

General Leclerc opens a negotiation with Toussaint L'Ouverture by means of his two sons, Isaac and Placide--The negotiation ends in nothing--The French Commander-in-chief outlaws Toussaint, and prepares for a campaign . . . . . 171 - CHAPTER V.

General Leclerc advances against Toussaint with 25,000 men in three divisions, intending to overwhelm him near Gonaïves--The plan is disconcerted by a check given by Toussaint to General Rochambeau in the Ravine Couleuvre. . . . . . 182 - CHAPTER VI.

Toussaint L'Ouverture prepares Crête-à-Pierrot as a point of resistance against Leclerc, who, mustering his forces, besieges the redoubt, which, after the bravest defence, is evacuated by the blacks . . . . . 190 - CHAPTER VII.

Shattered condition of the French army--Dark prospects of Toussaint--Leclerc opens negotiations for peace--Wins over Christophe and Dessalines--Offers to recognize Toussaint as Governor-General--Receives his submission on condition of preserving universal freedom--L'Ouverture in the quiet of his home . . . . . 200

BOOK II.

- FROM THE RAVAGES OF THE YELLOW FEVER IN HAYTI UNTIL THE DEPOSITION AND DEATH OF ITS LIBERATOR.

- CHAPTER I.

Leclerc's uneasy position in Saint Domingo from insufficiency of food, from the existence in his army of large bodies of blacks, and especially from a most destructive fever . . . . . 217 - CHAPTER II.

Bonaparte and Leclerc conspire to effect the arrest of Toussaint L'Ouverture, who is treacherously seized, sent to France, and confined in the Chateau de Joux; partial risings in consequence. . . . . . 225

Page x - CHAPTER III.

Leclerc tries to rule by creating jealousy and division--Ill-treats the men of color--Disarms the blacks--An insurrection ensues, and gains head, until it wrests from the violent hands of the General nearly all his possessions--Leclerc dies--Bonaparte resolves to send a new army to Saint Domingo . . . . . 243 - CHAPTER IV.

Rochambeau assumes the command--His character--Voluptuousness, tyranny, and cruelty--Receives large reinforcements--Institutes a system of terror--The insurrection becomes general and irresistible--The French are driven out of the island . . . . . 257 - CHAPTER V.

Toussaint L'Ouverture, a prisoner in the Jura Mountains, appeals in vain to the First Consul, who brings about his death by starvation--Outline of his career and character. (The end of Dr. Beard's Biography) . . . . . 276

BOOK III.

- Memoir of the Life of General Toussaint L'Ouverture, written by himself, in the Chateau de Joux, in a letter to Napoleon Bonaparte . . . . . 295

BOOK IV.

- I. Proclamation by King Christophe . . . . . 331

- II. Note by Harriet Martineau, including a description of a visit to the Chateau de Joux, and the Sonnet on Toussaint L'Ouverture by Wordsworth . . . . . 337

- III. A visit to the Chateau de Joux by John Bigelow, containing interesting documentary evidence relative to Toussaint's imprisonment therein . . . . . 347

- IV. The Poem on Toussaint L'Ouverture by John Greenleaf Whittier . . . . . 358

- V. Peroration of Wendell Phillip's Oration on Toussaint L'Ouverture . . . . . 366

NOTES AND TESTIMONIES.

- I. Outline Map of Colonial Hayti

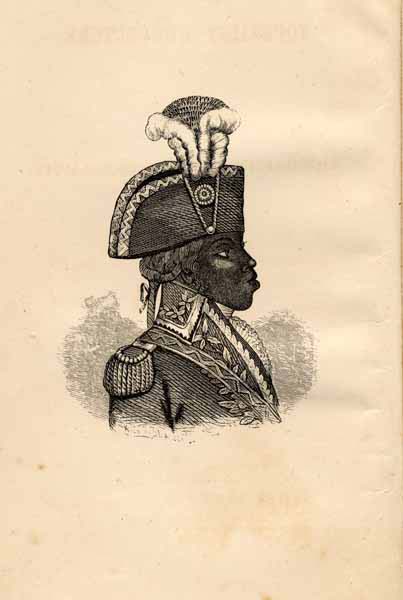

- II. An authentic Portrait of Toussaint L'Ouverture

- III. Autograph of Toussaint L'Ouverture . . . . . 12

ILLUSTRATIONS.

BOOK I.

CONTENTS.

Page 11

BOOK I.

FROM THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE STRUGGLE FOR LIBERTY IN HAYTI TO THE FULL ESTABLISHMENT OF TOUSSAINT L'OUVERTURES POWER.

Page 12

[Autograph of Toussaint L'Ouverture]

OUTLINE MAP OF COLONIAL HAYTI OR ST. DOMINGO.

Page 13

CHAPTER I.

Description of Hayti--Its name, mountains, rivers, climate, productions, and chief cities and towns.

I AM about to sketch the history and character of one of those extraordinary men, whom Providence, from time to time, raises up for the accomplishment of great, benign, and far-reaching results. I am about to supply the clearest evidence that there is no insuperable barrier between the light and the dark-colored tribes of our common human species. I am about to exhibit, in a series of indisputable facts, a proof that the much-misunderstood and down-trodden negro race are capable of the loftiest virtues and the most heroic efforts. I am about to present a tacit parallel between white men and dark men, in which the latter will appear to no disadvantage. Neither eulogy, however, nor disparagement is my aim, but the simple love of justice. It is a history, not an argument, that I purpose to set forth. In prosecuting the narrative, I shall have to conduct the reader through scenes of aggression, resistance, outrage, revenge, bloodshed, and cruelty, that grieve and wound the heart, and, exciting the deepest pity for the sufferers, raise irrepressible indignation against ambition, injustice, and tyranny,--the scourges of the world, and specially the sources of complicated and horrible calamities to the natives of Africa.

The western portion of the North Atlantic Ocean is separated from the Caribbean Sea on the south, and the Gulf of Mexico on the north, by a succession of islands which, under the name of the West India Islands, seem to unite, in a broken and waving line, the two great peninsulas of South and North America. Of these islands, which, under the general title of the Antilles, are divided into several groups, the largest and the

Page 14

most important are, Porto Rico on the east, Cuba on the west, and St. Domingo between the two, with Jamaica lying off the western extremity of the latter. Situated between the seventeenth and twentieth degrees of north latitude, and the sixty-eighth and seventy-fifth degrees of west longitude, St. Domingo stretches from east to west about 390 miles, with an average breadth, from north to south, of 100 miles, and comprises about 29,000 square miles, or 18,816,000 square acres; being four times as large as Jamaica, and nearly equal in extent to Ireland. Its original name, and that by which it is now generally known, Hayti,--which, in the Caribbean tongue, signifies a land of mountains,--is truly descriptive of its surface and general appearance. From a central point, which, near the middle of the island, rises to the height of some 6,000 feet above the level of the sea, branches, having parallel ranges on the north and on the south, run through the whole length of the island, giving it somewhat the shape and aspect of a huge tortoise. The mountain ridges for the most part extend to the sea, above which they stand in lofty precipices, forming numerous headlands and promontories, or, retiring before the ocean, give place to ample and commodious bays. Of these bays or harbors, three deserve mention, not only for their extraordinary natural capabilities, but for the frequency with which two of them, at least, will appear in these pages. On the northwest of Hayti, is the Bay of Samana, with its deep recesses and curving shores, terminating in Cape Samana on the north, and Cape Raphael on the south. At the opposite end of the country, is the magnificent harbor called the Bay Port-au-Prince, enclosing the long and rocky isle Gonave,--on the north of which is the Channel St. Marc, and on the south the Channel Gonave. Important as is the part which this harbor sustains in the history of the land, scarcely, if at all, less important is the bay which has Cape François for its western point, and Grange for its eastern, comprising on the latter side the minor but well sheltered Bay of Mancenille, and in the former the large roadstead of Cape François.

Page 15

The mountains running east and west break asunder and sink down so as to form three spacious valleys, which are watered by the three principal rivers. The River Youna, having its sources in Mount La Vega, in the northeast of the island, and receiving many tributaries from the north and the south, issues in the Bay of Samana. The Grand Yaque, rising on the western side of the Watershed,--of which La Vega may be considered as the dividing line,--flows through the lengthened plain of St. Jago, until it reaches the sea in the Bay of Mancenille. The chief river is the Artibonite, on the west, which, having its ultimate springs in the central group of mountains, waters the valleys of St. Thomas, of Banica, of Goave, and, turning suddenly to the north, along the western side of the mountains of Cahos, falls into the ocean a little south of the Bay of Gonaïves, after a long and winding course. While these rivers run from east to west and west to east,, innumerable streams flow in a northern and southern direction, proceeding at right angles from the branches of the great trunk. Hayti is a well-watered land; especially is it so in the west, where several lakes and tarns adorn and enrich the country. The more eastern districts are rugged as well as lofty, but the other parts are beautifully diversified with romantic glens, prolific vales, and rank savannahs. Though so mountainous, the surface is overspread with vegetation, the highest summits being crowned with forests. Placed within the tropics, Hayti has a hot yet humid climate, with a temperature of very great variations; so that while in the deep valleys the sun is almost intolerable, on the loftiest mountains of the interior a fire is often necessary to comfort. The ardor of the sun is on the coast moderated by the sea and land breezes, which blow in succession. Heavy rains fall in the months of May and June. Hurricanes are less frequent in Hayti than the rest of the Antilles. The climate, however, is liable to great and sudden changes, which, bringing storm, tempest, and sunshine, with the intensity of tropical lands, now alarm and now enervate the natives, and often prove very injurious to Europeans. On so rich a soil human life is easily supported,

Page 16

and the inducements to the labors of industry are neither numerous nor strong. Yet, in auspicious periods of its history, Hayti has been made abundantly productive. *

* For more detailed accounts, by various authors, of the geography of Hayti, its productions, soil, minerals, climate, seasons, and temperature, see Book I., chaps. 2-7, inclusive, of the Guide to Hayti.

At the time when the hero and patriot whose career we have to describe first appeared on the scene, the island was divided between two European Powers: the east was possessed by the Spaniards, the west and south by the French. It is with the latter portion that this history is mostly concerned.

Of the Spanish possessions, therefore, it may suffice to direct attention to two principal cities. The oldest European city is Santo Domingo, which had the honor of giving a name to the whole island. It was founded by Bartholomew, the brother of Columbus, who is said to have so called it in honor of his father, who bore that name. Santo Domingo stands in the southeastern part of the island, at the north of the River Ozama. Santiago holds a fine position in the plain of that name, near the northern end of a line passing somewhere about the middle of the island.

The French colony was divided into three Provinces,--that of the North, that of the West, and that of the South. At the beginning of the French Revolution of 1789, these provinces were transformed into three corresponding Departments. The three Provinces, or Departments, were subdivided into twelve Districts, each bearing the name of its chief city. The twelve Districts were,--in the north, the Cape, or Cap-François, Fort Dauphin, Port-de-Paix, Môle Saint Nicholas; in the west, Port-au-Prince, Leogane, Saint Marc, Petit Goave; and in the south, Jérémie, Cape Tiburon, Cayes, and St. Louis. The District of the Cape comprised the Cape, La Plaine-du-Nord, just above the Cape, Limonade, between the two; Acul, west of the Cape, and on the coast, Sainte Suzanne; with Morin, La Grande Rivière, Dondon, Marmelade, Limbé, Port Margot, Plaisance, and Borgne,--thirteen parishes. The District Fort Dauphin,

Page 17

in the east of the Northern Department, comprised Fort Dauphin itself, Ouanaminthe, on the south of it, Vallière, Terrier Rouge, and Trou,--five parishes. The District of Port-de-Paix comprised Port-de-Paix, Petit-Saint-Louis, Jean Rabel, and Gros-Morne,--four parishes. The District of the Môle Saint Nicholas comprised Saint Nicholas and Bombarde,--two parishes. There were thus four-and-twenty parishes in the northern department. The District Port-au-Prince comprised Port-au-Prince, Croix-des-Bosquets, on the north, Arcahaye on the northwest, and Mirebalais on the northeast,--four parishes. The District of Léogane was identical with the parish of the same name. The District of Saint Marc comprised Saint Marc, Petite Rivière, Gonaïves,--three parishes. The district of Petit-Goave comprised Petit-Goave, Grand Goave, Baynet, Jacmel, and Cayes-Jacmel,--five parishes. Fourteen parishes made up the western province. The District Jérémie comprised Jérémie and Cap Dame-Marie,--two parishes. The District of Tiburon comprised Cape Tiburon and Coteaux,--two parishes. The District of Cayes comprised Cayes and Torbeck,--two parishes. The District of Saint Louis comprised Saint Louis, Anse-Veau, Fond-Cavaillon, and Acquin,--five parishes. There were eleven parishes in the South.

The study of the map will show that these, the districts under the dominion of France, covered only the west of the island. As, however, they contained the chief centres of civilization, and the chief places which occur in this history, our end is answered by the geographical details now given.

The appearance of the island from the ocean is thus described by an eye-witness: "The bold outlines of the mountains, which in many places approached to within twenty miles of the shore, and the numerous stupendous cliffs which beetled over it, casting their shadows to a great distance in the deep,--the dark retreating bays, particularly that of Samana,--and extensive plains opening inland between the lofty cloud-covered hills, or running for uncounted leagues by the sea-side, covered with trees and bushes, but affording no glimpse of a human

Page 18

habitation,--presented a picture of gloom and grandeur, calculated deeply to impress the mind; such a picture as dense solitude, unenlivened by a single trace of civilization, is ever apt to produce. Where, we inquired of ourselves, are the people of this country? Where its cultivation? Are the ancient Indian possessors of the soil all extinct, and their cruel conquerors and successors entombed with them in a common grave? For hundreds of miles, as we swept along its shores, we saw no living thing, but now and then a mariner in a solitary skiff, or birds of the land and ocean sailing in the air, as if to show us that nature had not wholly lost its animation, and sunk into the sleep of death." *

* "Brief Notices of Hayti," by John Candler. London, 1842.

The interior of Hayti, however, lacks neither inhabitants nor natural beauty. The mountains rise in bold and varying outline against the brilliant skies, and in almost every part form a background of great and impressive effect. Broken by deep ravines, and appearing in bare and rugged precipices, they present a continued variety of imposing objects which sometimes rise into the sublime. The valleys and plains are rich at once in verdure and beauty, while from elevated spots you may enjoy the sight of the great centres of civilization, Cap-Francais, Port-de-Paix, Saint-Marc, Port-au-Prince, &c., busy in the various pursuits of city and commercial life.

The wealth of Hayti comes from its soil. It is an essentially agricultural country. Cereal products are not cultivated; but maize or Indian corn grows there; and rice flourishes in the savannas. The negro lives on the natural fruits of the island chiefly, and obtains fish, breadstuffs, and other merchandise from the United States. Plantation tillage is the chief occupation. This culture embraces sugar-cane (which is manufactured chiefly into syrup and rum), coffee, cocoa, and cotton. In 1789, the French portion of the island contained 793 sugar plantations, 3,117 coffee plantations, 789 cotton plantations, and 182 establishments for making rum, besides other minor factories and workshops. In 1791, very large capitals were employed in

Page 19

carrying on these cultivations; the capitals were sunk partly in slaves and partly in implements of husbandry; in the cultivation of sugar there was employed a capital of above fifty millions of livres;

*

* A livre, or franc, is worth about twenty cents of our money.

forty-six millions in coffee, and twenty-one millions in cotton; and in 1776, there was employed a capital of sixty-three millions in the cultivation of indigo.

The total value of the plantations was immense, as may be learnt from the fact, that the value of the products of the French portion was estimated--

- In 1767 at 75,000,000 francs

- In 1774 at 82,000,000 francs

- In 1776 at 95,148,500 francs

- In 1799 at 175,990,000 francs

The last value is the highest. The sum represents the supreme pressure of servitude, and is consequently a measure of the injury done to the black dwellers in Saint Domingo. Already, in 1801, the value fell to 65,352,039; in other words, the slave-masters were, at the end of two years, punished for their injustice and tyranny by the immediate loss of nearly two-thirds of their property; so uncertain is the tenure of illgotten gain. Among the territorial riches of Hayti, its beasts of burden and oxen must take a high position. In 1789, the soil supported 57,782 horses, 48,823 mules, and 247,612 horned cattle.

Hayti possesses an abundant source of opulence in its numerous forests, which produce various kinds of precious wood employed in making and decorating furniture and articles of taste.

In the year 1791, goods were exported from Hayti to France to the value of 133,534,423 francs,--that is, about $27,000,000. The entire value of the territorial riches of the chief plantations, including slaves, amounted to no less a sum than 991,893,334 francs. Curious is it, in the statistical table issued by authority, whence we learn these particulars, to see "negroes

Page 20

and animals employed in husbandry" put into the same class. Observe, too, the items. The value of the "negroes old and new, large and small," is set down at 758,333,334 francs, while the other animals are worth only 5,226,667 francs. We thus learn, that three-fourths of the wealth of the planters consisted in their slaves. Such was the stake which was at issue in the struggle for freedom of which we are about to speak.

The population of Hayti was, in the year 1824, accounted to amount to 935,335 individuals.

* * This census was purposely falsified. I made very careful inquiries respecting the population of Hayti at different periods, and concluded that at no time since its independence has Hayti proper--the French part--had more than from 500,000 to 600,000 inhabitants. See the Guide, p. 137.--ED.

This is not a large number for so fertile a land. But it has been questioned whether more than 700,000 dwelt on the soil. Doubtless, the wars which have successively agitated the country for more than half a century have greatly thinned the population. There has, however, been a constant immigration into Hayti from neighboring islands, and even from the continent of America. Of the total number of inhabitants just given, there were, in 1824,--

| In the Kingdom of Henry I. (Christophe) | 367,721 |

| In the Republic, under Pétion | 506,146 |

| In the old Spanish District | 61,468 |

| 935,335 |

This mass, viewed in regard to origin, was divided thus:--

| Negroes | 819,000 |

| Men of mixed blood | 105,000 |

| Red Indians | 1,500 |

| Whites | 500 |

| Foreigners | 10,000 |

| 936,000 |

The small number of whites was occasioned by the strict enforcement of the law which declared, "No white man, whatever be his nationality, shall be permitted to land on the Haytian territory, with the title of master or proprietor; nor shall

Page 21

he be able, in future, to acquire there, either real estate or the rights of a Haytian."

The language prevalent in the west and north is the French; that generally used in the east is the Spanish. Neither is spoken in purity. Not only has the French the ordinary grammatical faults which belong to the uneducated, but out of the peculiar formation of the negro organs of speech, the peculiar relations in which they have stood in social and political life, as as well as the nature of the climate and the products of the soil, a Haytian patois has been formed which can scarcely be understood by Frenchmen exclusively accustomed to their pure mother tongue. And while the educated classes speak and write what in courtesy may be called classic French, the few authors whom the island has produced do not appear capable of imitating, if they are capable of appreciating, the purity, ease, point, and flow which characterize the best French prose writers.

The religion of Hayti is the Roman Catholic. This form of religion is established by law. Under all Governments Protestantism has been protected. The religion of Rome exists among the people in a corrupt state, nor are the highest functionaries free from a gross superstition, which takes much of its force from old African traditions and observances, as well as from the peculiar susceptibilities of the negro temperament. As soon as the native chiefs began to obtain political power in their struggle for freedom, they practically recognized the importance of general education, well knowing that only by raising the slaves into men could they accomplish their task and perpetuate their power. Accordingly educational institutions have, from time to time, been set up in different parts of the island. These establishments have received favor and encouragement according to the spirit of the Government of the day. *

* The editor has made some changes both of omission and commission in the text of this chapter,--as some remarks in its derogatory to the Government applied with justice to Soulouque but not to Geffrard. The paragraph on the language of Hayti is not quite just; but the subject is treated at some length in the Guide, where specimens of the Haytian patois are given.

Page 22

CHAPTER II.

Columbus discovers Hayti--Under his successors, the Spanish colony extirpate the natives--The Buccaneers lay in the West the basis of the French colony--Its growth and prosperity.

WE owe the discovery of Hayti to Columbus. When, on his first voyage, he had left the Leucayan Islands, he, on the fifth of December, 1492, came in sight of Hayti, which at first he regarded as the continent. Having, under the shelter of a bay, cast anchor at the western extremity of the island, and named the spot Saint Nicholas, in honor of the saint of the day, he sent men to explore the country. These, on their return, made to Columbus a report, which was the more attractive, because they had found in the new country resemblances to their native land. A similar impression having been made on Columbus, especially by the songs which he heard in the air, and by fishes which had been caught on the coast, he named the island Espagnola, (Hispaniola,) or Little Spain. Forthwith, on his arrival, Columbus began to inquire for gold; the answers which he received induced him to direct his course toward the south. On his way, he entered a port which he called Valparaiso, now Port-de-Paix; and in this and a second visit occupied and named other spots, taking possession of the country on behalf of his patrons, Ferdinand and Isabella, sovereigns of Spain. The return of Columbus to Europe, after his first voyage, was accompanied by triumphs and marvels which directed the attention of the civilized world to the newly-discovered countries; and, exciting ambition and cupidity, originated the movement which precipitated Europeans on the American shores, and not only occasioned there oppression and cruelty, but introduced with African blood worse than African slavery, big with evils the most multiform and the most terrible.

Page 23

At the time of its discovery, Hayti was occupied by--if we may trust the reports--a million of inhabitants, of the Caribbean race. They were dark in color, short and small in person, and simple in their modes of life. Amid the abundance of nature, they easily gained a subsistence, and passed their many leisure hours either in unthinking repose, or in dances, enlivened by drums, and varied with songs. Polygamy was not only practised but sanctioned. A petty sovereign is said to have had a harem of two-and-thirty wives. Standing but a few degrees above barbarism, the natives were under the dominion of five petty kings or chiefs, called Caciques, who possessed absolute power; and were subject to the yet more rigorous sway of priests or Butios, to whom superstition lent an influence which was the greater because it included the resources of the physician as well as those of the enchanter. Under a repulsive exterior, the Haytians, however, acknowledged a supreme power,--the Author of all things, and entertained a dim idea of a future life, involving rewards and punishments correspondent to their low moral condition and gross conceptions.

On the arrival of Columbus, the natives, alarmed, withdrew into their dense forests. Gradually won back, they became familiarized with the new-comers, of whose ulterior designs they were utterly ignorant. With their assistance, Columbus erected, near Cap-François, a small fortress which he designated Navidad (nativity), from the day of the nativity (December 25th) on which it was completed. In this, the first edifice built by Europeans on the Western Hemisphere, he placed a garrison of eight-and-thirty men. When (on the 27th of October, 1493) he returned, he found the settlement in ruins, and learned that his men, impelled by the thirst for gold, had made their way to the mountains of Cibao, reported to contain mineral treasures. He erected another stronghold on the east of Cape Monte Christo. There, under the name of Isabella, arose the first city founded by the Spaniards, who thence went forth in quest of the much-coveted precious ore. Meanwhile the new

Page 24

colony had serious difficulties to struggle with. Barely were they saved from the devastations of a famine. Their acts of injustice drove the natives into open assault, which it required the skill and bravery of Columbus to overcome. His recall to Europe set all things in confusion. Restrained in some degree by his moderation and humanity, the natives on his departure rose against his brother and representative, Bartholomew; and, receiving support from another of his officers, namely, Rolando Ximenes, they aspired to recover the dominion of the island. They failed in their undertaking, the rather that Bartholomew knew how to gain for himself the advantage of a judicious and benevolent course. The love of a young Spaniard, named Diaz, for the daughter of a native chief, led Bartholomew to the mouth of the river Ozama. Finding the locality very superior, he built a citadel and founded a city there, which, under the name of Santo Domingo, he made his headquarters, intending it to be the capital of the country. Meanwhile, Ximenes, at Fort Isabella, carried on his opposition to the Government. Columbus's return to the island, in 1498, did not bring back the traitor to his duty. Meanwhile, in Spain, a storm had broken forth against Columbus, which occasioned his recall in 1499. The discoverer of the New World was put in chains and thrown into prison by his successor, Bovadillo. With the departure of Columbus, the spirit of the Spanish rule underwent a total change. The natives, whom he and his brother had treated as subjects, were by Bovadillo treated as slaves. Thousands of their best men were sent to extract gold from the mines, and when they rapidly perished in labors too severe for them, the loss was constantly made up by new supplies. In 1501, Bovadillo was recalled. His successor, Ovando, was equally unmerciful. On the death of Queen Isabella and Columbus, the Haytians lost the only persons who cared to mitigate their lot. Then all consideration toward them disappeared. They were employed in the most exhausting toil, they were misused in every manner; torn from the bosom of their families, they were driven into the remotest parts of the island,

Page 25

unprovided with even the bare necessaries of life. In 1506, a royal decree consigned the remainder as slaves to the adventurers, and Ovando failed not to carry the unchristian and inhuman ordinance into full effect, especially in regard to those who were at work in the mines, four of which were very productive. A rising, which took place in 1502, had no other result than to rivet the chains under which the natives groaned and perished. Another, in 1503, brought Anacoana, a native queen, to the scaffold. In 1507, the number of the Haytians had, by toil, hunger, and the sword, been reduced from a million down to sixty thousand persons. Of little service was it that, about this time, Pedro d'Atenza introduced the sugar-cane from the Canaries, or that Gonzalez, having set up the first sugar-mill, gave an impulse to agriculture; there were no hands to carry on the works, for the master labored not, and the slave was beneath the sod. Ovando made an effort to procure laborers from the Leucayan Isles. Forty thousand of these victims were transported to Hayti; they also sank under the labor. In 1511, there were only fourteen thousand red men left on the island; and they disappeared more and more in spite of the exertions for their preservation made by the noble Las Casas. In 1519, a young Cacique put himself at the head of the few remaining Haytians, and, after a bloody war of thirteen years' duration, extorted for himself and followers a small territory on the northeast of Saint Domingo, where their descendants are said to remain to the present day.

Greatly did the island suffer by the loss of its native population; the working of the gold mines ceased, or was carried on to a small extent, and with inconsiderable results; agriculture proceeded only here and there, and with tardy steps; the colony declined constantly more and more on every side. The metropolis alone withstood the prevalent causes of decay, for it had become a commercial entrepôt between the Old World and the New. Its prosperity, however, was, in 1586, seriously shaken by the English commander, Francis Blake, who, having seized the city, laid one-half in ruins. A still greater calamity impended.

Page 26

The reputed riches of the New World, and the wide spaces of open sea which its discovery made known, invited thither maritime adventurers from the coasts of Europe. Men of degraded character and boundless daring, finding it difficult to procure a subsistence by piracy and contraband trade in their old eastern haunts, now, from the newly-awakened spirit of maritime enterprise, frequented, if not scoured, by the vessels of England, Holland, and France, hurried away with fresh hopes into the western ocean, and swarmed wherever plunder seemed likely to reward their reckless hardihood.

Of these, known in history as the buccaneers, a party took possession (1630) of the isle of Tortuga, which lies off the northwest of Hayti. With this as a centre of operation, they carried on ceaseless depredations against Hayti, the coasts of which they disturbed and plundered, putting an end to its trade, and occupying its capital. The court of Madrid, being roused in self-defence, sent a fleet to Tortuga, who, taking possession of the island, destroyed whatever of the buccaneers they could find; but the success only made the pirates more wary and more enterprising. When the fleet had quitted Tortuga, they again, in 1638, made themselves masters there, and, after fortifying the island and establishing a sort of constitution, made it a centre of piratical resources and aggressions, whence they at their pleasure sallied forth to plunder and destroy ships of all nations, wreaking their vengeance chiefly on such as came from Spain. In time, however, these corsairs met with due punishment at the hands of civilized nations.

A remnant of the buccaneers, of French extraction, effected a settlement on the southwestern shores of Hayti, the possession of which they successfully maintained against Spain, the then recognized mistress of the island. In their new possessions they applied to the tillage of the land; but, becoming aware of the difficulty of maintaining their hold without assistance, they applied to France. Their claim was heard. In 1661, Dageron was sent to Hayti, with authority to take its government into his hands, and accordingly effected there, in 1665, a regularly

Page 27

constituted settlement. At this time the Spanish colony, which was scattered over the east of the island, consisted only of fourteen thousand free men, white and black, with the same number of slaves; two thousand maroons, moreover, prowled about the interior, and were in constant hostility with the colonists.

As yet, the French colony in the West was very weak. Its chief centre was in Tortuga. It had other settlements at Port de Paix, Port Margot, and Léogane. When Dageron came to Hayti, with the title of Governor, the Spaniards became more attentive to what went on in the west of the island. They proceeded to attack the French settlements, but with results so unsatisfactory that the new French Governor, Pouancey, drove them from all their positions in the West. His successor, Cussy, who took the helm in 1685, was less successful. The Spaniards made head against him, and the French power was nearly annihilated. In 1691, France made another effort. The new Governor, Ducasse, restored her dominion, and in the peace of Ryswick, Spain found itself obliged to cede to France the western half of Hayti. With characteristic enterprise and application, the French soon caused their colony to surpass the Spanish portion in the elements of social well-being; and in the long peace which followed the wars of the Spanish succession, Saint-Domingue (so the French called their part of the island) became the most important colony which France possessed in the West Indies. It suffered, indeed, from Law's swindling operations, and from other causes; but on the whole, it made great and rapid progress until the outbreak of the first revolutionary troubles in the mother country.

Side by side with the advance of agriculture, opulence spread on all sides, and poured untold treasures into France. In a similar proportion the population expanded, so that in 1790 there were in the western half of the island 555,825 inhabitants, of whom only 27,717 were white men, and 21,800 free men of color, while the slaves amounted to 495,528.

Page 28

CHAPTER III.

The diverse elements of the population of Hayti--The blacks, the whites, the mulattoes; immorality and servitude.

THE large black population of Hayti was of African origin. Stolen from their native land, they were transplanted in the island to become beasts of burden. The slave-trade was then at its height. Nations and individuals who stood at the head of the civilized world, and prided themselves in the name of Christian, were not ashamed to traffic in the bodies and souls of their fellow-men. Three hundred vessels, employed every year in that detestable traffic, spread robbery, conflagration, and carnage over the coasts and the lands of Africa. Eighty thousand men, women, and children, torn from their homes, were loaded with chains, and thrown into the holds of ships, a prey to desolation and despair. In vain had the laws and usages of Africa, less unjust than those of Christian countries, forbidden the sale of men born in slavery, permitting the outrage only in the case of persons taken in war, or such as had lost their liberty by death or crime. Cupidity created an ever-growing demand; the price of human flesh rose in the market; the required supply followed. The African princes, smitten with the love of lucre, disregarded the established limitations, and for their own bad purposes multiplied the causes which entailed the loss of liberty. Proceeding from a less to a greater wrong, they undertook wars expressly for the purpose of gaining captives for the slave mart; and when still the demand went on increasing, they became wholesale robbers of men, and seized a village, or scoured a district. From the coasts the devastation spread into the interior. A regularly organized system came into operation, which constantly sent to the sea-shore thousands of innocent

Page 29

and unfortunate creatures to whom death would have been a happy lot. In the year 1778, not fewer than one hundred thousand of its black inhabitants were forcibly and cruelly carried away from Africa.

Driven on board the ships which waited their arrival, these poor wretches, who had been accustomed to live in freedom, and roam at large, were thrust into a space scarcely large enough to receive their coffin. If a storm arose, the ports were closed as a measure of safety. The precaution shut out light and air. Then, who can say what torments the negroes underwent? Thousands perished by suffocation,--happily, even at the cost of life, delivered from their frightful agonies. Death, however, brought loss to their masters, and therefore it was warded off, when possible, by inflictions, which, in stimulating the frame, kept the vital energy in action. And when it was found that grief and degradation proved almost as deadly as bad air, and no air at all, the victims were forced to dance, and were insulted with music. If, on the ceasing of the tempest and the temporary disappearance of the plague, things resumed their ordinary course, lust and brutality outraged mothers and daughters unscrupulously, preferring as victims the young and innocent. When any were overcome by incurable disease, they were thrown into the ocean while yet alive, as worthless and unsalable articles. In shipwreck, the living cargo of human beings was ruthlessly abandoned. Fifteen thousand, it has been calculated,--fifteen thousand corpses every year scattered in the ocean, the greater part of which were thrown on the shores of the two hemispheres, marked the bloody and deadly track of the hateful slave-trade.

Hayti every year opened its markets to twenty thousand slaves. A degradation awaited them on the threshold of servitude. With a burning-iron they stamped on the breast of each slave, women as well as men, the name of their master, and that of the plantation where they were to toil. There the new-comer found everything strange,--the skies, the country, the language, the labor, the mode of life, the visage of his master,--all

Page 30

was strange. Taking their place among their companions in misfortune, they heard them speak only of what they endured, and saw the marks of the punishments they had received. Among the "old hands," few had reached advanced years; and of the new ones, many died of grief. The high spirit of the men was bowed down. For the two first years the women were not seldom struck with sterility. In earlier times, the proprietors had not wanted humanity; but riches had corrupted their hearts now; and giving themselves up to ease and voluptuousness, they thought of their slaves only as sources of income, whence the utmost was to be drawn.

The evils consequent on slavery are not lessened by the incoming of one or two stray rays of light. If the slave becomes conscious of his condition, and aware of the injustice under which he suffers, if he obtains but a faint idea of these things; and if the master learns that a desire for liberty has arisen in the slave's mind, or that free men are asserting anti-slavery doctrines, then a new element of evil is added to those which before were only too powerful. Hope on one side, and distrust and fear on the other, create uneasiness and disturbance, which may end in commotion, convulsion, cruelty, and blood. In the agitation of the public mind of the world, which preceded the first French Revolution, such feelings could not be excluded from any community on earth. They entered the plantations of Hayti, and they aided in preparing the terrific struggle, which, through alarm, agitation, and slaughter, issued in the independence of the island.

The white population was made up of diverse, and in a measure conflicting elements. There were first, the colonists or planters. Of these, some lived in the colony, others lived in France. The former, either by themselves or by means of stewards, superintended the plantations, and consumed the produce in sensual gratifications; the latter, deriving immense revenues directly or indirectly from their colonial estates, squandered their princely fortunes in the pleasures and vices of the less moral society of Paris. Possessed of opulence, these men generally

Page 31

were agitated with ambition, and sought office and titles as the only good things on earth left them to pursue. If debarred from entering the ranks of the French nobility, they could aspire to official distinction in Hayti, and in reality held the government of the colony very much in their own hands, partly in virtue of their property, partly in virtue of their influence with the French court.

There were other men of European origin in the island. Some were servants of the Government; others members of the army; both lived estranged from the population which they combined to oppress. Below these were les petits blancs (the small whites), men of inferior station, who conducted various kinds of business in the towns, and who, despised by white men more elevated in station, repaid themselves by contemning the black population, on the sweat of whose brows they depended for a livelihood. Contempt is always most intense and baleful between classes that are nearest each other.

From the mixture of black blood and white blood arose a new class, designated men of color. On the part of the planters, passion and lust were subject to no outward restraint, and rarely owned any strong inward control. From the blood sprung from this mixed and impure source came the chief cause of the troubles and ruin of the planters.

Some of the men of color were proprietors of rich possessions; but neither their wealth, nor the virtues by which they had acquired it, could procure for them social estimation. Their prosperity excited the envy of the whites in the lower classes. Though emancipated by law from the domination of individuals, the free men of color were considered as a sort of public property, and, as such, were exposed to the caprices of all the whites. Even before the law they stood on unequal ground. At the age of thirty, they were compelled to serve three years in a militia instituted against the Maroon negroes; they were subject to a special impost for the reparation of the roads; they were expressly shut out from all public offices, and from the more honorable professions and pursuits of private life.

Page 32

When they arrived at the gate of a city, they were required to alight from their horse; they were disqualified for sitting at a white man's table, for frequenting the same school, for occupying the same place at church, for having the same name, for being interred in the same cemetery, for receiving the succession of his property. Thus the son was unable to take his food at his father's board, kneel beside his father in his devotions, bear his father's name, lie in his father's tomb, succeed to his father's property,--to such an extent were the rights and affections of nature reversed and confounded. The disqualification pursued its victims until during six consecutive generations the white blood had become purified from its original stain.

Among the men of color existed every various shade. Some had as fair a complexion as ordinary Europeans; with others, the hue was nearly as sable as that of the pure negro blood. The mulatto, offspring of a white man and a negress, formed the first degree of color. The child of a white man by a mulatto woman was called a quarteroon,--the second degree; from a white father and a quarteroon mother was born the male tierceroon,--the third degree; the union of a white man with a female tierceroon produced the metif,--the fourth degree of color. The remaining varieties, if named, are barely distinguishable.

Lamentable is it to think that the troubles we are about to describe, and which might be designated the war of the skin, should have flowed from diversities so slight, variable, evanescent, and every way so inconsiderable. It would almost seem as if human passions only needed an excuse, and as if the slightest excuse would serve as a pretext and a cover for their riotous excesses.

On their side, the men of color, laboring under the sense of their personal and social injuries, tolerated, if they did not encourage in themselves, low and vindictive passions. Their pride of blood was the more intense the less they possessed of the coveted and privileged color. Haughty and disdainful toward the blacks, whom they despised, they were scornful

Page 33

toward the petits blancs, whom they hated, and jealous and turbulent toward the planters, whom they feared. With blood white enough to make them hopeful and aspiring, they possessed riches and social influence enough to make them formidable. By their alliance with their fathers they were tempted to seek for everything which was denied them in consequence of the hue and condition of their mothers. The mulattoes, therefore, were a hot-bed of dissatisfaction, and a furnace of turbulence. Aware by their education of the new ideas which were fermenting in Europe and in the United States, they were also ever on the watch to seize opportunities to avenge their wrongs, and to turn every incident to account for improving their social condition. Unable to endure the dominion of their white parents, they were indignant at the bare thought of the ascendency of the negroes; and while they plotted against the former, were the open, bitter, and irreconcilable foes of the latter. If the planters repelled the claims of the negroes' friends, least of all could emancipation be obtained by or with the aid of the mulattoes.

Such in general was the condition of society in Hayti, when the first movements of the great conflict began. On that land of servitude there were on all sides masters living in pleasure and luxury, women skilled in the arts of seduction, children abandoned by their fathers, or becoming their cruellest enemies, slaves, worn down by toil, sorrow, and regrets, or lacerated and mangled by punishments. Suicide, abortion, poisoning, revolts, and conflagration--all the vices and crimes which slavery engenders--became more and more frequent. Thirty slaves freed themselves together from their wretchedness the same day and the same hour; meanwhile, thirty thousand whites, freemen, lived in the midst of twenty thousand emancipated men of color and five hundred thousand slaves. Thus the advantage of numbers and of physical strength was on the side of the oppressed.

Page 34

CHAPTER IV.

Family, birth, and education of Toussaint L'Ouverture--His promotions in servitude--His marriage--Reads Raynal, and begins to think himself the providentially-appointed liberator of his oppressed brethren.

IN the midst of these conflicting passions and threatening disorders, there was a character quietly forming, which was to do more than all others, first to gain the mastery of them, and then to conduct them to issues of a favorable nature. This superior mind gathered its strength and matured its purposes in a class of Haytian society where least of all ordinary men would have looked for it. Who could suppose that the liberator of the slaves of Hayti, and the great type and pattern of negro excellence, existed and toiled in one of the despised gangs that pined away on the plantations of the island?

The appearance of a hero of negro blood was ardently to be wished, as affording the best proof of negro capability. By what other than a negro hand could it be expected that the blow would be struck which should show to the world that Africans could not only enjoy but gain personal and social freedom? To the more deep-sighted, the progress of events and the inevitable tendencies of society had darkly indicated the coming of a negro liberator. The presentiment found expression in the works of the Abbé Raynal, who predicted that a vindicator of negro wrongs would erelong arise out of the bosom of the negro race. That prediction had its fulfilment in Toussaint L'Ouverture.

Toussaint was a negro. We wish emphatically to mark the fact that he was wholly without white blood. Whatever he was, and whatever he did, he achieved all in virtue of qualities which in kind are common to the African race. Though of

Page 35

negro extraction, Toussaint, if we may believe family traditions, was not of common origin. His great grandfather is reported to have been an African king of the Arradas tribe.

The Arradas were a powerful tribe of negroes, eminent for mental resources, and of an indomitable will, who occupied a part of Western Africa. In a plundering expedition undertaken by a neighboring tribe, a son of the chief of the Arradas was made captive. His name was Gaou-Guinou. Sold to slave dealers, he was conveyed to Hayti, and became the property of the Count de Breda, who owned a sugar manufactory some two miles from Cap François. More fortunate than most of his race in their servitude, he found among his fellow-slaves countrymen by whom he was recognized, and from whom he received tokens of the respect which they judged due to his rank. The Count de Breda was a humane man, and intrusted his slaves to none but humane superintendents. At the time the plantation of the Count de Breda was directed by M. Bayou de Libertas, a Frenchman of mild character, who, contrary to the general practice, studied his employer's interests, without overloading his hands with immoderate labor.

Under him Gaou-Guinou was less unhappy than his companions in misfortune. It is not known that his master was aware of his superior position in his native country; but facts stated by Isaac, one of Toussaint L'Ouverture's sons, make the supposition not improbable. His grandfather, he reports, enjoyed full liberty on the estates of his master. He was also allowed to employ five slaves to cultivate a portion of land which had been assigned to him. He became a member of the Catholic Church, the religion of the rulers of Western Hayti, and married a woman, who was not only virtuous but beautiful. The husband and the wife died at nearly the same time, leaving five male children and three female. The eldest of his sons was Toussaint L'Ouverture.

These particulars, illustrative of the superiority of Toussaint's family, are neither without interest nor without importance. If, strictly speaking, virtues are not transmissible, virtuous tendencies,

Page 36

and certainly intellectual aptitudes, may pass from parents to children. And the facts now narrated may serve to show how it was that Toussaint was not sunk in that mental stagnation and moral depravity of which slavery is commonly the parent.

The exact day and year of Toussaint's birth are not known. It is said to have been the 20th of May, 1743.

* * It is not improbable that Toussaint was born on All Saints' Day, and derived his name from that fact.--ED.

What is of more importance is that he lived fifty years of his life in slavery before he became prominent as the vindicator of his brethren's rights. In that long space he had full time to become acquainted with their sufferings as well as their capabilities, and to form such deliberate resolutions as, when the time for action came, should not be likely to fail of effect. Yet does it seem a late period in a man's life for so great an undertaking; nor could any one endowed with inferior powers have approached to the accomplishment of the task.

Throughout his arduous and perilous career, Toussaint L'Ouverture found great support himself, and exerted great influence over others, in virtue of his deep and pervading sense of religion. We might almost declare that from that source he derived more power than from all others. The foundation of his religious sentiments was laid in his childhood.

There lived in the neighborhood of the Gaou-Guinou family a black esteemed for the purity and probity of his character, and who was not devoid of knowledge. His name was Pierre Baptiste. He was acquainted with French, and had a smattering of Latin, as well as some notions of geometry. For his education he was indebted to the goodness of one of those missionaries, who, in preaching the morality of a divine religion, enlighten and enlarge the minds of their disciples. Pierre Baptiste became the godfather of Toussaint, and therefore thought it his duty to communicate to him the instructions and impressions he had received from his own religious teacher. Continuing to speak his native African tongue, which was used in his family,

Page 37

Toussaint acquired from his godfather some acquaintance with the French, and, aided by the services of the Catholic Church, made a few steps in the knowledge of the Latin. With a love of country which ancestral recollections and domestic intimacies cherished, he took pleasure in reverting to the traditional histories of the land of his sires. From these Pierre Baptiste labored to direct his young mind and heart to loftier and purer examples consecrated in the records of the Christian church.

This course of instruction was of greater value than any skill in the outward processes which are too commonly identified with education. The young negro, however, seems to have made some progress in the arts of reading, writing, and drawing. A scholar, in the higher sense of the term, he never became; and, at an advanced period of life, when his knowledge was great and various, he regarded the instruction which he received in boyhood as very inconsiderable. Undoubtedly, in the pure and noble inspirations of his moral nature, Toussaint had instructors far more rich in knowledge and impulse than any pedagogue could have been. Yet in his youth were the foundations laid in external learning of value to the man, the general, and the legislator. It is true, that in the composition of his letters and addresses, he enjoyed the assistance of a cultivated secretary. Nevertheless, if the form was another's, the thought was his own; nor would he allow a document to pass from his hands, until, by repeated perusals, and numerous corrections, he had brought the general tenor, and each particular expression, into conformity with his own thoughts and his own purpose. Nor is there required anything more than an attentive reading of his extant compositions, to be assured of the superior mental powers with which he was endowed.

In his mature years, and in the days of his great conflict, Toussaint possessed an iron frame and a stout arm. Capable of almost any amount of labor and endurance, he was terrible in battle, and rarely struck without deadly effect. Yet in his childhood he was weak and infirm to such a degree, that for a long time his parents doubted of being able to preserve his existence.

Page 38

So delicate was his constitution that he received the descriptive appellation of Fatras-Bâton, which might be rendered in English by Little Lath. But with increase of years the stripling hardened and strengthened his frame by the severest labors and the most violent exercises. At the age of twelve he surpassed all his equals in the plantation in bodily feats.

The duty of the young slaves was definite and uniform. They were intrusted with the care of the flocks and herds. As a solitary and moral occupation, a shepherd's life gives time and opportunity for tranquil meditation. By nature Fatras-Bâton was given to thought. His reflective and taciturn disposition found appropriate nutriment on the rich uplands and under the brilliant skies of the land of his birth. Accustomed to think much more than he spoke, he acquired not only self-control, but also the power of concentrated reflection and concise speech, which, late in life, was one of his most marked and most serviceable characteristics.

Pastoral occupations are favorable to an acquaintance with vegetable products. Toussaint's father, like other Africans, was familiar with the healing virtues of many plants. These the old man explained to his son, whose knowledge expanded in the monotonous routine of his daily task. Thus did he obtain a rude familiarity with simples, of which he afterward made a practical application. In this period, when the youth was passing into the man, and when, as with all thoughtful persons, the mind becomes sensitively alive to things to come as well as to things present, Toussaint may have formed the first dim conception of the misery of servitude, and the need of a liberator. At present he lived with his fellow-sufferers in those narrow, low, and foul huts where regard to decency was impossible; he heard the twang of the driver's whip, and saw the blood streaming from the negro's body; he witnessed the separation of parents and children, and was made aware, by too many proofs, that in slavery neither home nor religion could accomplish its purposes. Not impossibly, then, it was at this time that he first discerned the image of a distant duty rising before his mind's

Page 39

eye; and as the future liberator unquestionably lay in his soul, the latent thought may at times have started forth, and for a moment occupied his consciousness. The means, indeed, do not exist by which we may certainly ascertain when he conceived the idea of becoming the avenger of his people's wrongs; but several intimations point to an early period in his life. His good conduct in his pastoral engagements procured for him an advancement. Bayou de Libertas, convinced of his diligence and fidelity, made him his coachman. This was an office of importance in the eyes of the slaves; certainly it was one which brought some comfort and some means of self-improvement.

Though Toussaint became every day more and more aware that he was a slave, and experienced many of the evils of his condition, yet, with the aid of religion, he avoided a murmuring spirit, and wisely employed his opportunities to make the best of the position in which he had been born, without, however, yielding to the degrading notion that his hardships were irremediable. Sustained by a sense of duty, which was even stronger than his hope of improving his condition, he performed his daily task in a composed if not a contented spirit, and so constantly won the confidence of the overseer. The result was his promotion to a place of trust. He was made steward of the implements employed in sugar-making.

Arrived at adult age, Toussaint began to think of marriage. His race at large he saw living in concubinage. As a religious man, he was forbidden by his conscience to enter into such a relation. As a humane man, he shrunk from the numerous evils which he knew concubinage entailed. Whom should he choose? Already had he risen above the silly preferences of form and feature. Reality he wanted, and the only real good in a wife, he was assured, lay in good sense, good feeling, and good manners. These qualities he found in a widow, well skilled in husbandry, a house-slave in the plantation. The kind-hearted and industrious Suzan became his lawful wife, according to "God's holy ordinance and the law of the land." By a man of color, Suzan had had a son, named Placide. Obeying the generous impulses of his heart, Toussaint adopted the

Page 40

youth, who ever retained the most lively sense of gratitude toward his benefactor.

Toussaint was now a happy man, considering his condition as a slave,--the husband of a slave,--a very happy man. His position gave him privileges, and he had a heart to enjoy them. His leisure hours he employed in cultivating a garden, which he was allowed to call his own. In those pleasing engagements he was not without a companion. "We went," he said to a traveller,--"we went to labor in the fields, my wife and I, hand in hand. Scarcely were we conscious of the fatigues of the day. Heaven always blessed our toil. Not only we swam in abundance, but we had the pleasure of giving food to blacks who needed it. On the Sabbath and on festival days we went to church,--my wife, my parents, and myself. Returning to our cottage, after a pleasant meal, we passed the remainder of the day as a family, and we closed it by prayer, in which all took part." Thus can religion convert a desert into a garden, and make a slave's cabin the abode of the purest happiness on earth.

Bent as Toussaint was on the improvement of his condition, he yet did not employ the personal property which ensued from his own and his wife's thrift, in purchasing his liberty, and elevating himself and family into the higher class of men of color. His reasons for remaining a slave are not recorded. He may have felt no attractions toward a class whose superiority was more nominal than real. He may have resolved to remain in a class whose emancipation he hoped some day to achieve.

The virtues of his character procured for Toussaint universal respect. He was esteemed and loved even by the free blacks. The great planters held him in consideration. His intellectual faculties ripened under the effects of his intercourse with free and white men. As he grew in mind, and became large of heart, he was more and more puzzled and distressed with the institution of slavery; he could in no way understand how the hue of the skin should put so great a social and personal distance between men whom God, he saw, had made essentially the same, and whom he knew to be useful if not indispensable

Page 41

to each other. Naturally he asked himself what others had thought and said of slavery. He had heard passages recited from Raynal. He procured the work. He read therein passages that eloquently told him of his rights, and with fiery zeal denounced his oppressor. He read, and became the vindicator of negro freedom. *

* The Editor has here omitted a long extract from Raynal, illustrative of his style, which, however, loses its interest when we read that "some parts which breathe too much the spirit of revenge have been softened or omitted in the translation." This is the only passage in it that deserves to be retained:--

"The last argument employed to justify slavery says, that 'slavery is the only way of conducting the negroes to eternal blessedness by means of Christian baptism.'