Josiah: The Maimed Fugitive.

A True Tale:

Electronic Edition.

Bleby, Henry, 1809-1882

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Elizabeth S. Wright

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc. and Elizabeth S. Wright

First edition, 2003

ca. 250K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2003.

Source Description:

(title page) Josiah: The Maimed Fugitive. A True Tale

(cover) Josiah: The Maimed Fugitive

(spine) Josiah: The Maimed Fugitive

Bleby, Henry, 1809-1882

[iii], 187, [1] p., ill.

London:

Sold at the Wesleyan Conference Office, 2, Castle-St., City [ink stain] ad; and at 66 Paternoster-Row

1873.

Call number x, Special Collection Elbert (Wellesley College Library)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

This electronic edition has been transcribed from the book provided by Wellesley College.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- African American clergy -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Biography.

- Fugitive slaves -- Canada -- Biography.

- Fugitive slaves -- Maryland -- Biography.

- Henson, Josiah, 1789-1883.

- Plantation life -- Maryland -- History -- 18th century.

- Plantation life -- Maryland -- History -- 19th century.

- Slavery -- Maryland -- History -- 18th century.

- Slavery -- Maryland -- History -- 19th century.

- Slaves -- Maryland -- Biography.

- Uncle Tom (Fictitious character)

- Underground railroad.

Revision History:

- 2004-06-14,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2003-10-07,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2003-08-28,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2003-08-28,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

[Spine Image]

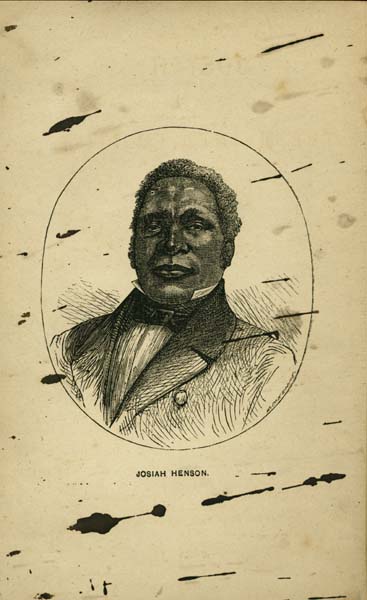

JOSIAH HENSON.

[Frontispiece Image]

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

JOSIAH:

THE MAIMED FUGITIVE.

A true Tale.

BY

HENRY BLEBY,

AUTHOR OF DEATH STRUGGLES OF SLAVERY; SCENES IN THE CARIBBEAN; THE REIGN OF TERROR; ROMANCE WITHOUT FICTION; THE STOLEN CHILDREN; APOSTLES AND FALSE APOSTLES; JEHOVAH'S DECREE OF PREDESTINATION, ETC., ETC.

LONDON:

SOLD AT THE WESLEYAN CONFERENCE OFFICE,

2, CASTLE-ST., CITY-ROAD

AND AT 66, PATERNOSTER-ROW.

1873.

Page ii

LONDON:

PRINTED BY WILLIAM NICHOLS,

46, HOXTON SQUARE.

Page 1

[First page of Chapter i]

JOSIAH:

THE MAIMED FUGITIVE.

Chapter i.

THE AUTHOR'S FIRST ACQUAINTANCE WITH THE SUBJECT OF THIS SKETCH.

BOSTON, in the State of Massachusetts, is, in a literary sense, the Athens of the United States of America, and a city of historical importance; for there commenced that series of events which produced the revolution of 1768, and gave birth to one of the greatest and most powerful nations in the world.

Having assisted in the Sabbath services on the preceding day, I was invited by one of the ministers of the Methodist Episcopal Church in the city to accompany him, on Monday forenoon, to the

Page 2

"Preachers' Meeting." This I found to be a weekly gathering of the ministers of the denomination resident in the city and its vicinity, originally convened for conversation on Church matters; but in course of time it had swept into a broader range, and took up the discussion of all subjects of thought in theology and ethics.

It was a beautiful morning in the July of 1858. Having accepted the courteous invitation, I accompanied my friend, at the appointed hour, to the Methodist book-store in Cornhill. Passing through the well-stocked store, after being presented to the gentleman in charge of the "Concern," we ascended a narrow, winding, iron staircase, which conducted us to a room of not very large dimensions, where I found assembled not less than forty or fifty gentlemen of various ages, just rising from their knees after the preliminary devotional exercises. A venerable-looking gentleman in clerical black and white cravat occupied the presidential chair, to whom, addressing him as "Father Merrill," my friend presented me as a missionary from the West Indies, in connexion with the British Conference. Extending to me a courteous welcome, Father Merrill invited me to take a seat near himself, observing that when the proper time arrived he would have the pleasure of introducing me to the meeting.

Page 3

Taking the seat allotted to me, I listened with interest to "the order of the day," which I found to be a discussion on "the identity of the resurrection body." This was carried on with much animation, the rules of debate being strictly observed. While the argument was proceeding, I looked around upon the group of persons assembled, all of whom seemed to be profoundly interested in the discussion. The place I occupied was favourable to observation. I could see every person in the room, several of whom attracted my particular attention. Near to me, and taking a leading and able part in the debate, was a fine, muscular-looking man, in the full vigour of early manhood; whom, from his dress, I should not, had I met him elsewhere, have taken to be a clergyman, as he was clothed in an entire suit of light grey tweed, with a black neck-tie. This was, as I afterwards learned, the Rev. Gilbert Haven, then in charge of one of the suburban churches, and afterwards to become the able editor of "Sion's Herald," the leading Methodist paper of New England; and, ultimately, one of the bishops of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Near to him, and occasionally interposing some caustic or humorous observation, was a man far advanced in life, whose large, lively, expressive countenance, full of deep furrows, seemed to mark him out as no ordinary man. And, indeed, he was not an ordinary

Page 4

man; but one who possessed the true nobility of genius, and stood out prominently among the celebrities of the age in which he lived. I knew him not by name, as I listened to the striking and beautiful words that occasionally dropped from his lips, and admired the brilliant light that flashed from his eyes, while his glasses were pushed up upon the broad and wrinkled brow. But afterwards I was introduced to him as "Father Taylor," the seamen's apostle, and the pastor of the Sailors' Home in Boston; a man of whom Harriet Martineau, J. Silk Buckingham, Charles Dickens, Miss Bremer, John Ross Dix, Miss Sedgwick, and Mrs. Jameson, have all written in terms of glowing eulogy, as an original genius, and one of the most celebrated of American preachers. All classes flocked to the humble seamen's church, where Father Taylor's eccentric eloquence and wit delighted, amused, and thrilled the multitude, and the preaching became, on a large scale, the power of God unto salvation to the blue jackets, who, in every port in the world, heard of the sailor preacher, and bent their footsteps to the Mariners' Church whenever they found themselves in the Boston harbour.*

* In "The Liberal Christian," the Rev. Dr. Bellows sketched the following portrait:--"Thirty years ago there was no pulpit in Boston around which the lovers of genius and eloquence gathered so often, or from such different quarters, as that in the Bethel at the remote North End, where Father Taylor preached. A square, firm-knit man, below the middle height, with sailor written in every look and motion; his face weather-beaten with outward and inward storms; pale, intense, nervous, with the most extraordinary dramatic play of features; eyes on fire, often quenched in tears; mouth contending between laughter and sobs; brow wrinkled, and working like a flapping foresail--he gave forth those wholly exceptional utterances, half prose and half poetry, in which sense and rhapsody, piety and wit, imagination and humour, shrewdness and passion, were blended in something never heard before, and certain never to be heard again. It is difficult to say how far the charm of his speech was due to his uneducated diction and a method that drew nothing from the schools. He broke in upon the prim propriety of an ethical era, and a formal style of preaching, with a passionate fervour that gave wholly new sensations to a generation that had successfully expelled all strong emotions from public speech. He roared like a lion, and cooed like a dove, and scolded and caressed, and brought forth laughter and tears. In truth, he was a dramatic genius, and equally great in the conception and the personation of his parts. With much original force of understanding, increased by contact with the rough world in many countries, he possessed an imagination which was almost Shakespearian in its vigour and flash. It quickened all the raw material of his mind into living things. His ideas came forth with hands and feet, and took hold of the earth and the heavens. He had a heart as tender as his mind was strong, and his imagination Protean; and this gave such a sympathetic quality to his voice and his whole manner, that, more than any speaker of power we ever knew, he was the master of pathos. Who can forget how rough sailors, and beautiful and cultivated Boston girls, and men like Webster and Emerson, and shop-boys and Cambridge students, and Jenny Lind and Miss Bremer and Harriet Martineau, and everybody of taste or curiosity who visited Boston, were seen weeping together with Father Taylor, himself almost afloat again in his own tears, as he described some tender incident in the forecastle, some sailor's death-bed, some recent shipwreck, or sent his life-boat to the rescue of some drowning soul. Unique, a man of genius, a great nature, a whole soul, wonderful in conversation, tremendous in off-hand speeches, greatest of all in the pulpit, he was, perhaps, the most original preacher, and one of the most effective pulpit and platform orators America has produced. And, alas! nothing remains of him but his memory and his influence. He will be an incredible myth in another generation. Let us who knew him well keep his true image before us as long as we can."

Page 5

At the end of the room, most distant from where I was sitting, there was another individual who at

Page 6

once attracted my attention, and whose presence in such an assembly awakened in me a feeling of surprise and curiosity. I knew how strong was the prejudice concerning colour in the Northern Free States, and that even in Methodist churches there was to be found the Negro pew in some corner of the gallery, to keep the despised ones entirely apart from their fellow worshippers. But there, in that grave assembly of divines, to my great surprise, I saw an unmistakable scion of the Negro race;

Page 7

taking no part in the discussion, it is true, but manifestly regarded by those who sat near him as "a man and a brother." He exhibited a person of the middle size, firm and well knit; his skin was of the true African jet; and clothed in a new glossy suit of clerical broad cloth, he was all over black, except the spotless cravat and a set of pearly white teeth, that might have been made of the finest ivory Africa can produce, so brightly did they glitter, when some flash of oratory in the debate, or some sally of Father Taylor's sparkling wit, caused the broad African features to expand into a smile, or provoked a hearty laugh. And this was very often the case. Again and again, as I sat and looked upon him, did laughter spread itself over all the lines of his countenance, and tell of a rollicking, fun-loving spirit, that could not often, or for long together, be clouded with gloom.

After I had addressed the meeting at the invitation of the chairman, and replied to many questions concerning the results of emancipation in the West Indies,--the slavery question being the all-absorbing topic of the day, I was introduced to Mr. Haven, Father Taylor, Dr. Whedon, who like myself was a visitor, and many others; among them the coloured gentleman whom I had regarded with such lively curiosity. "This," said Mr. Merrill, "is Father Henson, the original of Mrs. Stowe's famous Uncle

Page 8

Tom. He was a slave in the Southern States, but escaped to Canada; where he has founded a large settlement of fugitives, and lives among them as a patriarch and a preacher of the Gospel." On looking at him more closely as he stood before me, holding a glossy white beaver hat in one hand, while he extended to me the other in friendly salutation, I observed that both his arms were crippled, so that he could by no means use them freely. "Our friend Henson, you see," remarked Mr. Haven, "has had his share of suffering, and slavery has left its mark upon him." The injury referred to, as I afterwards learned from himself, had been inflicted by the cruelty of an overseer in the slave land, from which he had happily made his escape. Such was my first introduction to Josiah Henson, the maimed fugitive slave preacher. A few evenings later I met him by invitation at the house of a friend; and frequently afterwards I was favoured with his company in walking home to my lodgings, after I had addressed congregations in the city churches on the emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies,--a subject in which he felt and manifested a deep and lively interest. Wherever I spoke on this subject, in or near the city, I was sure to see the dark, bright countenance of "Father Henson" upturned in the congregation; and he often waited at the door to join me in my

Page 9

homeward walk. On these occasions, in answer to my inquiries, he entered in his own lively and animated style into details of his past history; which I found to be interspersed with scenes and adventures more thrilling than those which are pictured in the pages of many a novel. Kindly assisted by Mrs. Harriet B. Stowe, he had written and published a history of his life, and of the numerous journeys he had made into the slave land, after his own escape from slavery, for the purpose of assisting others to gain their liberty. A copy of this publication I obtained from himself. I was so much interested in my sable friend that I made notes of the conversations I had with him from time to time. From the materials thus obtained I have been enabled to sketch the following narrative; marking, as I proceed, the vicissitudes of a somewhat extraordinary career, not likely to be repeated in actual life, now that American slavery, with its sanginuary oppressions, the underground railway with its mysteries, and the daring adventures of fugitives to escape to a free land, are numbered with the things of the past.

Page 10

[First page of Chapter ii]

Chapter ii.

BORN TO AN INHERITANCE OF EVIL AND SUFFERING.

HOW fearfully blinded by prejudice and interest must those ministers of the Gospel have been, who once stood boldly forth to advocate the Divine right of the slaveholder! A more fearful wrong could not be done to human beings than that which was inflicted upon the millions who were born to an inheritance of slavery in the Southern States of the American Union. Brought into the world by a slave mother, the poor slave child, before he could possibly be guilty of any offence to incur such a penalty,--before he could inhale the vital air,--was plundered of all the rights of humanity and doomed to be a chattel,--doomed body and soul to be the property of another; deprived of the right to dispose of his own time, to enjoy the fruit of his own labour, to have his own wife, and to dispose of and control

Page 11

his own children! Such was the patrimony of the subject of this sketch.

He was born in June, 1789, in Charles County, State of Maryland, on a farm belonging to a Mr. Francis Newman, situated about a mile from Port Tobacco. His mother was hired out to work on this farm, being the slave of a Dr. Josiah M'Pherson, and here it was that she met with and was married to the father of Josiah. The slave in America, as elsewhere, followed the fortunes of the mother, and Josiah's mother being the property of M'Pherson, her child likewise became his slave. M'Pherson was one of a class by no means uncommon amongst slaveholders. A man of good generous impulses, liberal, jovial, and hearty, he was far more kind to his slaves than the planters generally were, never suffering them to be punished or struck by any one. No degree of arbitrary power could ever lead him to forget, like others, the claims of humanity, and exercise cruelty towards his dependents. As the first Negro child ever born to him, Josiah became his pet. He gave him his own Christian name, and added to it the name of Henson, after an uncle of his, whose memory he revered, and who was an officer in the Revolutionary war.

Josiah knew very little concerning his father; and that little was of a tragical character, forming

Page 12

an episode in his own history that remained, all through life, a dark spot upon his memory. This, he observed, was the only incident concerning his mother's husband which, in after years, he could call to mind. One day his father appeared among his fellow slaves with his head all bloody, his back fearfully lacerated, and almost beside himself with mingled rage and suffering. Child as he was, no explanation was given to Josiah concerning the cruel punishment to which his father had been subjected; but, shrewd and intelligent beyond his years, he picked up from the conversation of others an outline of the facts, which made an indelible impression upon his memory, and as he grew older he clearly understood it all.

While he was at work in the field, Josiah's father heard screams arising from a retired spot near at hand, which he recognised as coming from his own wife. He threw down his hoe, and hastened to the place whence the screams proceeded. Maddened by a brutal outrage which had been inflicted upon his wife by the overseer, an outrage common enough in the slave land, he flew like a tiger upon the aggressor.

He was a man of great muscular power, and in the full vigour of his manhood. The cowardly, trembling overseer had no chance with his assailant. In a moment he was down, and there and

Page 13

then his wicked life would have been brought to a sudden end by the furious husband, had not the wife interposed to prevent such a catastrophe. The humbled caitiff was allowed to rise and depart, promising, in the most abject manner, that nothing more should ever be said concerning the punishment he had justly received. The promise was kept--like most promises of the cowardly and debased--only as long as the danger lasted.

The laws of the slave states provided ample means and opportunities for ruffianly revenge to such aggressors as this overseer. "A nigger had struck a white man!" That was enough to set a whole county on fire. No question was asked about the provocation: that was a matter of indifference. The fact, that the hand of a Negro had been raised against the sacred person of a white man, was a crime so terrible in the eyes of slaveholders that nothing could possibly excuse it, no provocation whatsoever could justify it. The authorities were speedily in pursuit of the daring offender, and he must be brought to condign punishment. For awhile he kept out of the way, hiding in the woods, venturing only at night into some cabin in search of food. But this could not continue long. A watch so strict was set that all supplies were cut off, and, starved out, he was compelled at length to surrender, and give himself up to the tender mercies of his foes.

Page 14

The penalty pronounced for this offence, of defending his wife from outrage, was a hundred lashes on the bare back, and to have the right ear nailed to the whipping post, and then severed from the head. This reminds us of the days when Englishmen groaned under the rule of the Stuarts, and, for trivial offences against the majesty of feudal tyrants, were subjected to similar treatment,--mutilation, and the pillory. The day for the execution of the sentence arrived. From all the surrounding plantations the Negroes were summoned, for their moral improvement, to witness the edifying scene; and the planters from all around assembled to revel in an enjoyment so congenial to their tastes. A powerful blacksmith, named Hewes, whose brawny arm, with its muscles fully developed by years of toil, qualified him well for the task, laid on the stripes. Fifty were given with all the power of the inflicter, during which the sufferer's cries might be heard a mile away; and then a pause ensued. True, he had struck a white man: but he is valuable property, and must not be so damaged as to be disabled for work. Experienced men feel his pulse. It is not, as yet, very much lowered: he can stand the whole. Again and again the cruel thong falls upon the lacerated, gory back, the cries grow fainter and fainter, until a feeble groan is the only response yielded to the

Page 15

final stripes. His head, now that the flogging is over, is rudely thrust against the post to which he is tied, and the right ear fastened to it with a nail. A swift pass of a knife, and the bleeding member is left sticking where it has been nailed. Then comes a loud hurrah from the whites crowding around, as one of them exclaims, "That's what he got for striking a white man!" A few of the spectators frowned upon the deed of blood, and said, "It is a shame!" But the majority approved and applauded the whole proceeding as a proper tribute to the white man's offended dignity. A blow at one white man was looked upon as a blow levelled at the whole community of slaveowners. It was felt to be as the muttering and upheaving of volcanic fires underlying and threatening to burst forth and utterly consume the whole social fabric. Chronic fear of insurrection was the condition in which the whites lived; and terror is the fiercest nurse of cruelty, as was fearfully manifested in the Jamaica panic of 1865, when so many lives were sacrificed through the utterly groundless fright, which rendered the local authorities incapable of the exercise of anything like sound judgment and discretion.

Previous to this occurrence, Josiah's father had been one of the most light-hearted and good-tempered men in the neighbourhood, and a ring-leader

Page 16

in all the fun and jollity that marked the corn-huskings and the Christmas buffooneries of the slaves. His banjo was often in requisition, and he was the life of the farm; often playing all night at a merrymaking while the other Negroes danced. But from the hour that he passed through this cruel punishment he became utterly changed. The milk of human kindness in his heart was turned into gall. He brooded over his wrongs, and became sullen, morose, and dogged. All the elasticity of his nature seemed to have departed utterly, and he became so intractable and ferocious that nothing could be done with him. No fear or threats of being sold to the far South--the greatest of all terrors to the slaves in the border states--could produce any effect upon him, or make him the buoyant, tractable slave he had been before. No amount of punishment could subdue or break his spirit. So he was sent off to Alabama, and Josiah saw his father never more. "What was his after fate," said Josiah, "neither I nor my mother have ever learned; the great day will reveal all." Thus husband and wife were parted, and father and child were severed, to meet no more until the great day, when the wrong-doer and his victim shall stand before the righteous Judge of quick and dead, and "every one shall give account of himself to God."

Page 17

After the sale of this poor fellow to the South, M'Pherson, the owner of Josiah's mother, would no longer hire out the injured wife to Newman; for he was amongst those who looked with abhorrence upon the cruelty that had been practised towards the husband. She accordingly returned to the farm of her owner, a widowed wife. Treated with indulgence, and petted by his master, Josiah felt little of the bitterness of slavery; but one of those changes was at hand, which often brought a dark cloud over the condition and prospects of kindly treated slaves, and sadly changed the whole current of their existence. M'Pherson was not exempt from that failing which too often besets and ensnares persons of easy temper and disposition in a drinking, dissipated community. Although he was esteemed as a man possessing much goodness of heart, kind and benevolent to all around him, he could not restrain his convivial propensities. The fiend of intemperance laid his iron grasp upon him, and he became utterly incapable of resisting the habit that steadily grew upon and enthralled him. This, as in a multitude of other cases, brought him to a premature grave. Two of the Negroes of the plantation found him one morning lying dead in a narrow stream of water, not a foot in depth. He had been away from home on the previous night at a drinking party, and when

Page 18

returning home had fallen from his horse. Too much intoxicated to help himself out of the shallow stream into which he fell, he had lain there and perished. Josiah could well remember, though he was but a child when the event occurred, the scene of the accident, as pointed out to him in these words, "That's the place where Massa got drownded at."

Page 19

[First page of Chapter iii]

Chapter iii.

VICISSITUDES OF CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH.

IT is a blessing unspeakably great in any condition of life, to have a pious mother! How largely does the destiny of the child in most cases depend on the mother! And how many owe all their success in life, and all their hope of heaven, to the loving counsels, care, and prayers of godly mothers! Who does not remember how all that was good and great in Doddridge, and Curran, and the Wesleys, was attributable, under God, to the influence shed upon them in early life by their mothers? In his lowly and almost hopeless condition, Josiah was favoured with this inestimable advantage--a pious, praying mother, watching over and tending his infant and childish days. How or where she acquired her knowledge of God, and her acquaintance with the

Page 20

Lord's Prayer, Josiah never knew: but, he said, "She was a good mother to us, anxious above all things to touch her children's hearts with a sense of religion, and bring them up in the ways of the Lord. She frequently taught us to repeat the beautiful words of the Lord's Prayer, and I remember seeing her often on her knees in our little cabin trying to express her thoughts and petitions in prayers appropriate to her situation and wants. They amounted to little more than constant fervent ejaculations, and the repetition of short familiar phrases; but they were the utterances of a devout and humble mind, offered up in all faith and sincerity; and doubtless had power to prevail with God. They made a deep impression on my infant mind, and have remained in my memory to this hour."

The death of Dr. M'Pherson was a most painful event to his friends, but it was a far greater calamity to his unfortunate slaves. For two or three years after her husband was sold and sent South, Josiah's mother and her six children had resided in comfort on her master's plantation; and they had been happy together. Now, alas! their term of happy union as one family must come to an end. The death of the owner of slaves was often the occasion of wide-spread grief and woe amongst his dependents, causing as it did their

Page 21

sale and scattering; the dearest ties being recklessly rent asunder, and families often broken up and parted, never to see, or even hear of, each other again. So it was to be with the family of which Josiah was one of the child members. M'Pherson's estate and slaves had to be sold, and the proceeds divided among the heirs; and they were regarded only in the light of property, not as a tender mother and the children which God had given her.

Common as slave auctions were in the Southern States, and naturally as a slave might look forward to the time when he would be put up on the block, the full misery of the event, the anguish and suffering which precede and follow the slave auction, could only be understood when the actual experience came. The first sad announcement that the sale was to be; the knowledge that all ties of the past were to be sundered; the frantic terror at the idea of being sent "down South;" the almost certainty that one member of the family would be torn from another; the anxious scanning of purchasers' faces; the agony of parting for ever with husband, wife, child--these must be seen and felt to be fully understood. "Young as I was then," said Josiah, "the iron entered into my soul. The remembrance of the breaking up of M'Pherson's estate is stamped in its minutest features upon my mind. The crowd collected around the stand; the

Page 22

huddling group of terrified Negroes; the examination of muscle, teeth, and limbs, and the exhibition of agility; the look of the auctioneer; the agony of my mother! I can never forget them! I shut my eyes, and I see them all."

Josiah was the youngest; and the elder children were bid off first, one by one, while the mother, paralysed with grief, held him by the hand. Her turn came, and she was bought by a man named Isaac Riley, of Montgomery county. Then little Josiah was offered to the assembled purchasers. The loving mother, half distracted with the thought of parting for ever with all her children, pushed through the crowd, while the bidding for Josiah was going on, to the spot where Riley, her new owner, was standing. She fell at his feet, and embraced his knees, entreating him in tones which only a mother could command, and with many tears, to buy her "baby" as well as herself, and spare to her one at least of her little ones. It can scarcely be believed, yet it is true, that this man, thus appealed to, not only turned a deaf ear to the agonized suppliant, but disengaged himself from her with curses and blows and kicks, and sent her creeping out of his reach with the groan of bodily suffering mingling with the sob of a breaking heart. "I must have been then," said Josiah, "between five and six years old. I seem to see and hear my poor

Page 23

weeping mother now. This was one of my earliest observations of men, but an experience which I only shared with thousands of my race, the bitterness of which to any individual who suffers it cannot be diminished by the frequency of its recurrence; while it is dark enough to overshadow the whole after life with something blacker than a funeral pall."

Josiah was bought by a stranger named Robb, "and truly," he said, "a robber he was to me. He took me to his home, about forty miles distant, and put me into his Negro quarters, with about forty or fifty others, of all ages, colours, and conditions, and all strangers to me. Of course nobody cared for me. The slaves were brutalized by their degradation, and could feel no sympathy for the suffering child thus torn from his mother, and thrust in amongst them. I soon fell sick, and lay for some days almost dead upon the ground. Sometimes one of the slaves would give me a piece of corn bread or a bit of herring, but I became so feeble that I could not move. This, however, turned out to be fortunate for me; for in the course of a few weeks Robb met with Riley, who had bought my mother, and offered to sell me to him cheap. Riley said he was afraid the little devil would die, and he did not want to buy a dead nigger! They finally struck a bargain, Riley agreeing to pay a small sum

Page 24

for me in horseshoeing, if I lived, and nothing if I died. Robb was a tavern-keeper, the owner of a line of stages, with the horses belonging to them, and lived near Montgomery court house. Riley carried on a blacksmith business about five miles from that place. After this arrangement was agreed upon, I was soon sent to my mother, and a blessed, grateful change it was to me. I had been lying on a lot of filthy rags thrown upon a dirt floor. All day long I was left alone, crying sometimes for water, sometimes for mother, whose loving care I greatly missed: for the other slaves, who went out to their work at daybreak, gave no attention to me. It mattered nothing to them whether I lived or died. Now I was once more with my best friend on earth, and tenderly cared for with all a mother's love, intensified as it was by the cruel bereavement of all her other children. She was destitute of all means of ministering to my comfort; but, nevertheless, she nursed me into health, and I became vigorous and strong beyond most boys of the same age."

The new master, Riley, into whose hands Josiah fell when he returned to his mother's care, was coarse and vulgar in his habits, profligate, unprincipled, and cruel. He suffered the unfortunate beings who were his slaves to have little opportunity of relaxation from wearying labour, supplying

Page 25

them scantily with necessary food, so that they had often to endure the sharp pangs of hunger, and acted fully on the principle that his slaves possessed "no rights which he was bound to respect." The natural tendency of slavery is to make the master a tyrant, which the nobler dispositions of a few enable them to overcome, and to convert the slaves into the cringing, treacherous, false, and thieving victims of oppression, which many of them became, when not brought under the elevating influences of religion. Riley and his slaves were apt illustrations of this tendency of the system to degrade and brutalize both the master and his dependents.

The earliest employments of the child-chattel, Josiah, were to carry water to the slaves at their work, and to hold a horse plough, used for weeding between the rows of corn. As he grew older and taller he was entrusted with the care of his master's saddle horse, in which occupation he continued for several years, enjoying many a stolen ride. But while quite a stripling a hoe was put into his hands, and he was required to do the work of a man. "It was not long," said Josiah, "before I could do it, at least as well as any of my associates in misery."

The principal food of the slaves on Riley's plantation consisted of a stinted allowance of corn-meal and salt herrings. To this was added, in summer,

Page 26

a little buttermilk and the few vegetables which each might be able to raise on the little piece of ground assigned to him, called a truck patch. In ordinary times they had two meals a day:--breakfast at twelve o'clock, after labouring from daybreak, and supper at night, when the work of the day was over. In harvest they had three meals, the hours of toil being prolonged to the uttermost point of endurance. Their dress was of tow cloth; for the children only a shirt: for the older ones a pair of pantaloons, or a gown, in addition. A woollen hat was given to each once in two or three years, and once a year a coarse pair of shoes. In the winter a jacket or overcoat was added to their equipment.

On Riley's farm anything like comfortable cabins for his slaves was out of the question. They were lodged in log huts, on the bare ground, wooden floors being an unknown luxury. All ideas of refinement or decency were disregarded. In a single room were huddled like cattle ten or a dozen men, women, and children. There were neither bedsteads nor furniture of any description. The beds were collections of old rags and straw, thrown down in the corners, and boxed in with any old boards they could find and appropriate to such a purpose, a single blanket the only covering. The wind whistled, and the rain and snow blew in through the cracks, and the damp earth soaked in the moisture till the

Page 27

floor was miry as a pig-sty. In these wretched hovels were the slaves penned at night and fed by day; here were the children born, and the sick and dying neglected.

Notwithstanding these discomforts and hardships, Josiah, lovingly fostered by his mother, grew to be a robust and vigorous boy, "lively as a young buck," as he described himself, "and running over with animal spirits," so that few could compete with him in work or sport. He could run faster, wrestle better, and jump higher than any about him. All this caused his master and fellow slaves to look upon him as a very smart fellow. His vanity was inflamed, and he fully coincided in their opinion. "Julius Cæsar," he said, "never aspired and plotted for the imperial crown more ambitiously than did I to out-hoe, out-reap, out-husk, out-dance, out-everything, every competitor! and from all I can learn he never enjoyed his triumphs half so much. One word of commendation from the petty despot who ruled over us would set me up for a month. I have no desire to represent the life of slavery as nothing but an experience of misery. God be praised, that however hedged in by unfavouring circumstances the joyful exuberance of youth will bound at times over them all. Ours is a light-hearted race. The sternest and most covetous master cannot frighten or whip the fun

Page 28

quite out of us; certainly old Riley never did out of me. In those days I had many a merry time; and would have had if I had lived with nothing but mocassins and rattlesnakes in Okafenoke swamp. Slavery did its best to make me wretched; but nature, or the blessed God of youth and joy, was mightier than slavery. Along with the memories of miry cabins, frostbitten feet, weary toil under the blazing sun, curses and blows, there flock in others of jolly Christmas times, dances before old massa's door for the first drink of egg-nog, extra meat at holiday times, midnight visits to apple-orchards, broiling stray chickens, and first-rate tricks to dodge work. The God who makes the lamb to gambol, and the kitten play, and the bird sing, and the fish leap, was the Author in me of many a light-hearted hour. True it was, indeed, that the fun and frolic of Christmas, at which time my master relaxed his front, was generally followed by a reaction, under which he drove and cursed worse than ever. Still the fun and the frolic were fixed facts. We had enjoyed them, and he could not help it."

But the exuberance of animal spirits, which characterized the slave boy, was not all expended in useless, selfish frolic. Under the prayerful training of that good slave mother, the thoughtless lad had been taught to cherish a kindly sympathy towards others who had less to make them happy,

Page 29

and more to make them wretched, than he had; and he was often led to exercise the spirit of adventure in which he delighted to soothe and lighten the sorrows of those around him. The miseries which he saw many of the women suffer often filled him with sorrow. Compelled to perform unfit labour, sick, suffering, and bearing the peculiar burdens of their own sex unpitied and unaided, as well as the toils which belong to the other, his enderest sympathies were often aroused in their behalf. "No white knight, rescuing white fair ones from cruel oppression, ever felt the throbbing of a chivalrous heart more intensely than I, a black slave boy, did, in running down a chicken in an out-of-the-way place to hide till dark, and then carry it to some poor, overworked, black fair one, to whom it was at once food, luxury, and medicine. No Scotch borderer, levying black mail, or sweeping off a drove of cattle, ever felt more assured of the justice of his act than I of mine, in driving a mile or two into the woods a pig or a sheep, and slaughtering it for the good of those whom Riley was starving. I love and admire the sentiment of chivalry, with the splendid environment of castles, and tilts, and gallantry, in which poets and romancers have set it forth. And this was all the exercise of chivalry that my circumstances and condition of life permitted, myself the dark-skinned

Page 30

paladin, Dinah or Patsy the outraged maiden, and old Riley as the grim oppressor. However mistaken my views of rectitude may then have been, these deeds of boyish adventure to relieve the sufferers around me were my training in the luxury of doing good, and sprang from a righteous indignation against the cruel and the oppressive."

Page 31

[First page of Chapter iv]

Chapter iv.

BECOMES THE SUBJECT OF A GREAT MORAL CHANGE.

THE mind and heart of Josiah, unconsciously to himself, were influenced largely by the beautiful example, and the prayers and counsels, of his pious mother; and doubtless they thus received from her a tendency in the right direction. By his mother he was led to think much of God. From her he learnt that there was in him an undying soul, and that to save him and all sinners God, the loving Father, sent His own Son into the world to sufter and to die. In that mother, ignorant and enslaved as she was, he saw daily exemplified the beauty and power of religion; and he was, amid all the frivolity which was natural to him in a high degree, often led by her conversation to think deeply concerning God and the things pertaining to the soul and its destiny. He was thus

Page 32

prepared for an event that was to change and mould the whole of his future existence, and bring the grateful answer to his mother's unceasing prayers on his behalf.

At Georgetown, a few miles from Riley's farm, lived a white man whose name was John M'Kenny. His business was that of a baker; his character that of an upright benevolent Christian, who lived the religion that he professed. He was noted for his detestation of slavery; and he resolutely avoided the employment of slave labour in his business. He would not even hire a slave the price of whose labour must be paid to the master, but carried on his business with his own hands and such free labour as he could procure; content with small profits uncontaminated by wrong doing, rather than the increase of wealth he might have commanded had he been less scrupulous and conscientious. This singular abstinence from what no one about him thought wrong, and the probity and excellence of his character, procured for him great respect, and prepared the way for great usefulness to his fellow man. M'Kenny often took upon him the work of preaching the Gospel; for at that period ministers of Christ were rare in the neighbourhood, and the inhabitants had few opportunities of hearing the truth. Thus he was a great light in a dark place, and many through his preaching were led to

Page 33

the sinner's Friend. Not a few crushed and heart-broken slaves received through him those heavenly consolations which were so well suited to their sorrowful condition, and welcome as the water-spring in the desert land.

One Sabbath this good man was to preach at a few miles' distance from Riley's plantation, and Josiah's mother, anxious above all things for the soul of her child, urged him to ask his master's permission to go and hear him. He had often been beaten for making such a request, and assigned this as a reason for refusing to comply with his mother's wishes. She told him, "You will never be a true Christian if you are to be afraid of a beating," and persisted in urging him to make the request, adding, "Like the good Massa, you must take up the cross and bear it." To gratify her, and dry up the tears which his refusal of her wishes called forth, Josiah resolved to try the experiment, and accordingly went and asked Riley's permission to go to the meeting. Somewhat to his surprise, the favour was accorded with less scolding and cursing than he expected, but with a pretty distinct intimation of the evil that would befall him if he did not return immediately after the close of the service.

"I hurried off," said Josiah, "pleased with the opportunity of hearing a preaching, but without

Page 34

any definite expectations of benefit or of the amusement in which I most delighted; for up to this time, and I was then near eighteen years old, I had never heard a sermon, nor any discourse or conversation whatever upon religious topics, except what I had heard from my mother, who carefully taught me the responsibility of all to a Supreme Being. When I arrived at the place of meeting, the services were so far advanced that the speaker was just beginning his discourse from the text, Hebrews ii. 9: "That He, by the grace of God, should taste death for every man." This was the first text of the Bible I had ever listened to, knowing it to be such. I have never forgotten it, and scarcely a day has passed since in which I have not recalled it, and the sermon that was preached from it.

"Who can describe my feelings, and the strange influence that came upon and overwhelmed me, as I listened to those wondrous words? I was at once attracted by the manner and earnestness of the preacher, the loving expression of his countenance, and the light that seemed to gleam from his eyes. And then I became entranced, my whole soul absorbed in the theme upon which he dwelt. He spoke of the Divine character of Jesus Christ, His tender love for mankind, His forgiving spirit, His compassion for the outcast and despised and

Page 35

the guilty, His crucifixion and His glorious resurrection and ascension; and some of these he dwelt upon with great power:--great especially to me, who then heard of these things for the first time in my life. Again and again did the preacher reiterate the words, 'for every man:'--these glad tidings, this great salvation, were not for the benefit of a select few only. They were for the slave as well as the master, the poor as well as the rich, the distressed, the heavy laden, the captive. They were for me--I felt they were for me--among the rest, a poor, despised, abused creature, deemed of others fit for nothing but unrequited toil, and mental and bodily degradation. O, the blessedness and sweetness of the feeling that then came over me! I was LOVED! I could have died that moment with joy for the compassionate Saviour about whom I was hearing. 'He loves me. He looks down from heaven in compassion and forgiveness on me, a great sinner. He died to save my soul. He'll welcome me to the skies,' I kept repeating to myself. I was transported with a delicious joy I had never felt before. I seemed to see a glorious Being in a cloud of splendour smiling down from on high. In sharp contrast with the experience of the contempt and brutality of my earthly master, I seemed to bask in the sunshine of the benignity of this glorious Being! He'll be

Page 36

my dear refuge--He'll wipe away the tears from my eyes! Now I can bear all things. Nothing will seem hard after this! I felt sorry that my master, Riley, did not know this loving Saviour; sorry that he should live such a coarse, wicked, cruel life. Swallowed up in the beauty of the Divine love, I could love my enemies, and prayed for them that did despitefully use and entreat me.

"Revolving the things which I had heard in my mind, and excited as I had never been in my life before, I turned aside from the road on my way home into the woods, and spent some time there in prayer. I prayed as I had never prayed in all my life, pouring out my whole soul to God. I cried unto Him for light and aid with an earnestness which, however unenlightened, was sincere and heartfelt; and I have no doubt it was acceptable to Him who heareth prayer. From this day, so memorable, so important to me--the day of my conversion--I date my awakening to a new life, a consciousness of power and of a destiny superior to anything I had before conceived of. I began now to use every means and opportunity of inquiry into religious matters. Religion became to me, indeed, the great business and concern of my life. So deep was my conviction of its superior importance to everything else; so clear my perception of my own faults, and of the darkness and sin that

Page 37

JOSIAH'S PLACE OF PRAYER.

Page 39

surrounded me, that I could not help talking much on these subjects with those about me; and all took notice of the great change that had come over me, making strangely thoughtful and serious the ever-frolicsome and mischief-loving lad they had always known me to be from a child."

He now began to pray with his fellow-slaves, and converse with them about subjects concerning which most of them were shut up in the grossest darkness; and, as in many other instances, this led him on by degrees to speak to them collectively, and address to them an occasional exhortation. As a fire in his bones was the love of God so unexpectedly shed abroad in his heart, and he felt constrained by a power within him, which he was very far from understanding himself, to impart to the suffering and degraded hordes with whom he was associated those little glimmerings of light which had reached his own eye. And, O! how greatly was the heart of that godly mother rejoiced by these new developments in Josiah! For years she had as it were travailed in birth again for the soul of this only child which the cruelty of men had left her. Profoundly ignorant of all other knowledge, she had been made wise unto salvation, and enjoyed in her own soul the peace and love of God; she knew how to value the soul of her boy, and longed and laboured, under all the disadvantages

Page 40

of her condition as an over-wrought slave, to draw him to Christ. Day and night she had borne him up before God in prayer. To the best of her knowledge and ability she had endeavoured, with loving assiduity, to instil into that bright and active mind the great principles of religious truth. And her labour had not been lost. With many tears she had dropped the good seed into the young heart, and now the Almighty and all-pervading energy of God had caused it to germinate and give the promise of an abundant harvest. During many years of anxious solicitude, which can be felt only by a godly mother for an only child, like the prophet on Carmel, she had laid the fuel in faith that the fire from above would kindle it; and now the spark from heaven, of which M'Kenny was the chosen medium, had fallen. The precious soul of her child, to her own great happiness, was all aglow with the fire of a new and celestial life. Let mothers, more highly favoured with advantages that never came to the lot of this poor enslaved daughter of Africa, pursue the course that her hallowed instincts of affection prompted her to follow concerning the soul of her child, and they will reap the same reward. There is a mighty power in the prayers that are sent to the skies winged with a devoted mother's faith and love.

Page 41

[First page of Chapter v]

Chapter v.

SAD EXPERIENCES IN THE HOUSE OF BONDAGE.

JOSIAH was endowed with more than an ordinary degree of energy. Quick-witted, active, clever, and fruitful in resources, and always ambitious to excel in whatever he put his hand to, he became very valuable to his master. He watched over that master's interests with great fidelity, and exposed the knavery of the overseers, who plundered their employer whenever they found the opportunity. While scarcely out of his boyhood, he had acquired great influence over his fellow-slaves; and being appointed superintendent of the farm, he not only kept the people in better and more cheerful order than they had ever been before, but he obtained from them more willing labour, by exercising only the law of kindness, and doubled the crops, to the

Page 42

great profit of his owner. The pride and ambition that were natural to him had made him strive to be proficient in every department of farm work.

Under a different system this would have brought to him additional emolument and increased worldly comfort. But was not Josiah a slave; body and soul, with all his energies, the absolute property of his master? To him, as he was circumstanced, it brought only an increase of burdens and responsibilities. His master was too much embruted by his association with slavery, and the exercise of irresponsible power over the unfortunate ones under his control, to reward a faithful servant with kindness or decent treatment. Josiah had to care for all the crops of wheat, oats, barley, potatoes, corn, tobacco, &c., which the master left entirely to him; and he was often compelled at midnight to start with the waggon for a distant market, and drive on through mud and rain till morning, sell the produce, and return home hungry and weary, to receive as his reward only oaths and curses and threatenings for not obtaining higher prices. Riley was like most slaveholders of his class, a fearful blasphemer, and seldom opened his lips without giving utterance to profane and violent language.

He was also a drunken profligate, indulging in vile habits which were common enough among the dissipated planters of the neighbourhood.

Page 43

Saturday and Sunday were their usual holidays; and it was their practice to assemble on these days at some low tavern, and devote themselves to gambling, running horses, fighting game-cocks, and discussing politics; indulging in large libations of whiskey and brandy. Well aware that they would be in such a condition as not to be able to find their way home at night, each one would order his groom, or body-servant, to come after him, to take care of him, and see him safe home. Josiah was chosen by his master to perform this office; and many a time he has walked by Riley's horse, holding him in the saddle, which he was too drunk to keep without help, plodding, at or after the midnight hour, through deep darkness and mud some miles from the tavern to the farm. These drunken carousals not unfrequently terminated in brawls and quarrels of the most violent description: glasses and chairs would be thrown, dirks and knives drawn, and pistols fired; some of the ruffianly brawlers sometimes carrying home with them serious wounds; and occasionally a life would be sacrificed before the uproar ceased. On such occasions, when the state of things became dangerous, the slave servants of the rioters were accustomed to rush in and extricate their masters from the fight, and take them home. This was often a perilous service to perform; not only as the slaves were liable to be

Page 44

injured by the weapons called into use, but they occasionally turned against themselves the violence of the drunken masters, whom, for their own safety, they sought to lead or control, or that of the exasperated ruffians to whom they might be opposed. "To tell the truth," says Josiah, "this was a part of my business, for which I felt no reluctance. I was young, remarkably athletic and self-relying; and in such affrays, whenever I had to mingle with them, I carried it with a high hand. I would elbow my way among the whites, whom it would have been almost death for me to strike, seize my master, and drag him out, mount him on his horse, or crowd him into his buggy, with as much ease as I would handle a bag of corn."

In one of these brutal outbursts, Josiah's master became involved in a violent quarrel with a man named Bryce Lytton, who was overseer to his brother, another Riley, who owned a farm in the same neighbourhood. This Lytton was a man of ruffianly character and ferocious habits. How the quarrel originated, or who was right or wrong, Josiah knew not; but all the rest of the drunken set sided with Lytton, and there was a general row. "I was sitting on the steps," said Josiah, "in front of the tavern, when I heard the scuffle, and rushed into to look after my charge. My master was a noted bruiser, and in such a fight could generally

Page 45

hold his own, and clear a handsome space around him; but now he was cornered, and a dozen were striking at him with fists, crockery, chairs, and anything that came handy. The moment he saw me he hallooed, 'That's it, Sie, pitch in! show me fair play!' It was a rough business, and I went in roughly, shoving and tripping, and doing my best to get to the rescue of Riley. With much trouble, and after getting many a bruise on my head and shoulders, I at length got him out of the room, and took him safe home. He was crazy with drink and rage, and struggled hard with me to get back and renew the fight. But I managed to lift him into his waggon, jump in, and drive off.

"By ill luck, during the scuffle, Bryce Lytton got a severe fall. Whether it was the whiskey or a chance shove from me that caused his fall, I cannot say. He, however, attributed it to me, and treasured up his vengeance for the first favourable opportunity. When sought, such an opportunity is readily found.

"About a week afterwards, I was sent by my master to a place a few miles distant, on horseback, with some letters. I took a short cut through a lane, separated by gates from the high road, and enclosed by a fence on either side. This lane passed through part of the farm belonging to my master's brother, and Lytton was in an adjacent field with three

Page 46

Negroes when I was passing by. On my return, half-an-hour afterwards, the overseer was sitting on the fence: but I could see nothing of the Negroes. I rode on quite unsuspicious of any trouble: but as I rode up he jumped off the fence, and at the same moment two of the Negroes sprang from under the bushes, where they had been concealed, and stood with him in front of me, while the other sprang over the fence just behind me. I was thus enclosed between what I could no longer doubt were hostile forces. Lytton seized the bridle, and ordered me to alight, in no gentle terms, oaths and curses flowing from his lips, as was usual with him, with great volubility. I asked what I was to alight for. 'To take such a flogging as you never had in your life, you black scoundrel,' using a variety of expletives which I care not to repeat. 'But what am I to be flogged for, Mr. Lytton?' I asked. 'Not a word,' said he, 'but light at once, and take off your jacket.' I saw there was nothing else to be done, and slipped off the horse on the opposite side from him. 'Now take off your shirt,' cried he; and as I demurred at this, he lifted a stick he had in his hand to strike me, but so suddenly and violently that he frightened the horse, which broke away from him, and galloped off in the direction of his stable. I was thus left without means of escape to sustain the attack of four men as well as I might.

Page 47

In avoiding Mr. Lytton's blow, I had accidentally got into a corner of the snake fence, where I could not be approached except in front. The overseer called upon the Negroes to seize me; but they, knowing something of my muscular power, were slow to obey. At length they did their best, and as they brought themselves within my reach, I knocked them all down in succession, and there they lay sprawling on the ground, in no hurry to get up and renew the attack. One of them trying to trip up my feet when he was down, I gave him a kick with my heavy shoe, which knocked out several of his teeth, and sent him howling away.

"Meanwhile the overseer was playing away upon my head with a stick; not heavy enough, indeed, to knock me down, but drawing blood freely; shouting all the while, 'Won't you give up? Won't you give up, you black -- --?' Exasperated at my defence, he suddenly seized upon one of the heavy fence rails, and rushed at me, to bring the contest to a sudden close. The ponderous blow fell. I lifted my arm to ward it off: the bone cracked like a pipe-stem, and I fell headlong to the ground. Repeated blows then rained upon me till both my shoulder blades were broken, and the blood gushed copiously from my mouth. In vain the Negroes endeavoured to interpose. 'Didn't you see the -- nigger strike me?' This

Page 48

was false; for the lying coward had avoided close quarters, and kept carefully beyond my reach, fighting with his stick alone. His vengeance satisfied, at length he desisted, telling me to learn what it was to strike a white man."

"Meanwhile an alarm had been given at the house by the return of the horse without a rider, and my master started off with a small party in search of me. When he first saw me he was swearing with rage. 'You've been fighting, you -- nigger.' I told him Bryce Lytton had been beating me, because I shoved him the other night at the tavern when there was a row. Seeing how much I was injured, he became more fearfully enraged; and after having me carried home, for I was unable to move, he mounted his horse, and rode over to Montgomery Court House, to enter a complaint. But little came of it. Lytton swore that I was insolent, jumped off my horse, made at him, and would have killed him but for the help of his Negroes. Of course no Negro's testimony could be admitted against a white man, and he was acquitted. My master was obliged to pay all the costs of court; and although he had the satisfaction of denouncing Lytton as a liar and a scoundrel, and giving him a tremendous bruising that sent him to his bed for several days, yet even this was rendered the less gratifying by what followed,

Page 49

which was a suit for damages, and a heavy fine for the assault."

By this brutal treatment poor Josiah was maimed and disabled for life. When I was first introduced to him, I observed that he could not lift his hand to his head; and that when he had to put on or take off his hat he brought his head down to his hand. Both his arms appeared to be shorter than they should have been in proportion to his size, and he was stiff and awkward in the use of them. And this was the cause. Besides the broken arm, and the wounds on his head and other parts of his person, both his shoulder blades were broken, and he could hear and feel the shattered bones grating against each other at every breath he drew. His sufferings, as he described them, were intense. No physician or surgeon was called in to dress his wounds or set the broken bones. It was not the practice on Riley's plantation to spend money upon doctors, and none was ever called in on any occasion whatever. "A nigger will get well any way," was a doctrine recognised and acted upon there. "And facts seemed to justify it," observed Josiah. "The robust, physical health produced by a life of out-door labour made our wounds heal up with as little inflammation as they do in the case of cattle." He was attended by his master's sister, Miss Patty, as she

Page 50

was called upon the farm, who was looked upon as the Æsculapius of the plantation. She was a powerful, big-boned woman, of Amazonian proportions and strength, unencumbered by anything like diffidence, and ready, whenever occasion presented, to wrench out a tooth, set and splinter a broken bone, or take a rifle, as she had been known to do, and shoot a furious ox that the Negroes were in vain attempting to butcher. She set herself to repair, as well as she knew how, the injuries that Josiah had received. "But alas!" said the sufferer, "it was but cobbler's work. From that day to this I have been unable to raise my hands as high as my head. It was five months before I could work at all: and the first time I held the plough, a hard knock of the coulter against a stone shattered my shoulder-blades again, and gave me even greater agony than at first. And so I have gone through life maimed and mutilated. Practice enabled me in time to perform the farm labours with considerable efficiency; but the free, vigorous play of muscle and arm was gone for ever."

Crippled as he was, Josiah was able to save his master the expenditure of a considerable salary to a white overseer. He was made the superintendent of the estate, and gradually came to have the disposal of everything raised on the farm. The wheat, oats, hay, fruit, butter, &c., were confided to

Page 51

him, and he obtained better prices for them than the master could do himself, or any one else was likely to do for him. "I will not deny," he said, "that I used his property more freely than he would have done in supplying his slaves with proper food; but in this I did him no wrong, for it was unequivocally for his own benefit, as the people did better and more cheerful work, and produced more abundant crops. I accounted, with the strictest honesty, for every dollar I received in the sale of the property entrusted to me."

Page 52

[First page of Chapter vi]

Chapter vi.

BECOMES A FUGITIVE FOR HIS MASTER'S OWN PROFIT.

WHEN he was about twenty-two years of age, Josiah took to himself a wife. The object of his choice was a girl who had been well brought up in a neighbouring family, who bore the reputation of being pious, and kind to their slaves. He first met her at some of the religious meetings held in the neighbourhood, and a mutual attachment sprang up between them; and with the consent of all parties she became his wife. "She was the mother of my twelve children," he said to me, "eight of whom still survive, and promise to be the comfort of my declining years."

Things went on with little change for several years, when his master, at the age of forty-five,

Page 53

married a girl of eighteen, who had some little property. She was remarkable for, and practised, a degree of economy in the household which brought no addition to the comfort of the family. She had a younger brother, named Francis, to whom Riley was appointed guardian. "The youth used to complain," Josiah remarked, "not without reason, I am confident, of the meanness of the provision made for the household; and he would often come to me, with tears in his eyes, to tell me he could not get enough to eat. I made him my friend by sympathizing with his grief and satisfying his appetite, sharing with him the food I took care to provide for my own family."

After a while the dissipation of Josiah's master became more than a match for his wife's domestic saving, and he became involved in difficulty and pecuniary embarrassment. This was enhanced by a lawsuit with a brother-in-law, who charged him with dishonesty in the management of property confided to him in trust. The litigation was protracted, and it brought him to ruin.

Harsh and tyrannical as he had often been, Josiah pitied him in his distress. At times he was dreadfully dejected and cast down; at others crazy with drink and rage, swearing and storming at all about him. "Day after day," said his faithful slave, "he would ride over to Montgomery Court

Page 54

House, to look after this troublesome business, and every day his affairs became more desperate. He would come into my cabin, to tell me how the suit was progressing; but spent the time chiefly in lamenting his misfortunes, and cursing his brother-in-law. I tried to comfort him as well as I could. He had confidence in my fidelity and judgment; and partly through a sort of pride or self-complacency I felt in being thus appealed to, but more through the spirit of love I had learned to admire and imitate in the Lord Jesus Christ, I entered with great interest into all his perplexities. The poor, drinking, furious, moaning creature was utterly incapable of managing his affairs. Shiftlessness, licentiousness, and drink, had complicated them quite as much as actual dishonesty."

At length the crisis came. "One night, in the month of January, long after I had fallen asleep, overcome with the fatigues of the day, he came into my cabin and roused me up. I thought it strange: but for a time he said nothing, and sat moodily warming himself by the fire. Then he began to groan and wring his hands. 'Sick, massa?' said I. He made no reply; but kept on moaning. 'Can't I help you any way, massa?' I spoke tenderly; for my heart was full of compassion at his wretched appearance. At last, collecting himself, he cried, 'O, Sie! I'm ruined, ruined,

Page 55

ruined!' 'How so, massa?' 'They've got judgment against me; and in less that two weeks every nigger I've got will be put up and sold.' Then he burst into a storm of curses at his brother-in-law.

"I sat silent, powerless to utter a word. Not only did I pity him, but I was filled with terror at the anticipation of the sad fate which I perceived was now hanging over my own family, and the terrible separation with which we were threatened. So it is. The calamity that falls upon the master often comes with tenfold crushing weight upon his unfortunate slaves.

" 'And now, Sie,' continued Riley, 'there's only one way I can save anything. You can do it: won't you, won't you?' In his great distress he rose, and actually threw his arms around me. Misery had levelled all distinctions. 'If I can do it, Massa, I will. What is it?' Without replying he went on, 'Won't you, won't you? I raised you, Sie; I made you overseer; I know I've often abused you, Sie, but I didn't mean it.' Still he avoided telling me what he wanted. 'Promise me you'll do it, boy!' He seemed resolutely bent on having my promise first, well knowing from past experience that what I agreed to do I should spare no pains or labour to accomplish. Solicited in this way, so urgently, and with tears, by the man whom I had

Page 56

so zealously served for many years, and who now seemed absolutely dependent upon his slave--impelled, too, by the fear which he skilfully awakened that the sheriff would seize every one who belonged to him, and that all would be separated, or perhaps sold to go to Georgia or Louisiana,--a fate greatly dreaded by slaves in the border states,--I consented, and promised to do all I could to save him from the fate impending over him.

"At last the proposition came. 'I want you to run away, Sie, to my brother Amos, in Kentucky, and take all the servants along with you.' I could not have been more startled had he asked me to go to the moon. 'Kentucky, Massa, Kentucky? I don't know the way!' 'O, it's easy enough for a smart fellow like you to find it. I'll give you a pass, and tell you just what to do.' Perceiving that I hesitated, he endeavoured to frighten me by again referring to the terrors of being sold to Georgia.

"For two or three hours he continued to urge me to the undertaking, appealing now to my sympathy and compassion, then to my pride, and again to my fears. At last, appalling as it seemed to me, I yielded, and told him I would do my best. There were eighteen Negroes, besides my wife, two children, and myself, to transport nearly a thousand miles, through a country about which I knew

Page 57

nothing, and in mid-winter; for it was the month of February, 1825. My master proposed to follow me in a few months, and establish himself in Kentucky."

Josiah set himself earnestly about the needful preparations. They were few, and easily made. Fortunately for the success of the questionable undertaking, the Negroes of the plantation fell readily into the scheme. Devotedly attached to him who was to be their leader and guide, because of the many alleviations he had afforded to their miserable condition, the kindly consideration he had always shown to them, and the comforts he had procured them, they readily submitted themselves to his authority. Besides, the dread of being sold away down South, should they remain on the old estate, united them as one man, and kept them patient and alert.

A one-horse waggon was prepared, well stocked with meal and bacon for the support of the party, and oats for the use of the horse. The second night after the scheme was broached they were on their way. They started about eleven o'clock, and made no halt until noon on the following day; for all were anxious to put as great a distance between themselves and the evils that threatened them as possible. The men trudged on foot, the women and children rode in the waggon, and walked alternately,

Page 58

as they were able. On they went through Alexandria, Culpepper, Fanquier, Harper's Ferry, and Cumberland, most of them places rendered familiar by the events of the late civil war, until they arrived at Wheeling. At the taverns along the road they found places prepared for the use of the droves of Negroes that were continually passing along, under the system of the internal slave trade. There they lodged, paying for the accommodation; this being their only expense, as they carried their food with them. When questions were put to them, as was not unfrequently the case, Josiah exhibited the "pass" which his master had given him, authorizing him to conduct his Negroes to Kentucky: his vanity being occasionally gratified when the encomium of "smart nigger" was applied to him.

At the places where they stopped to rest for the night they often met with Negro drivers, and their gangs of slaves, almost uniformly chained to prevent their running away. "Whose niggers are these?" was an inquiry often propounded to Josiah. On being informed, the next inquiry would be, "Where are they going?" "To Kentucky." "Who drives them?" "Well, I have charge of them," was Josiah's reply. "What a smart nigger!" was the usual exclamation, accompanied with an oath. "Will your master sell you? Come in, and stop with us." In this way he was often

Page 59

invited to pass the evening with them inside; their Negroes, meanwhile, lying chained in the pen, while Josiah's party were scattered around at liberty.

Arrived at Wheeling, on the Ohio River, according to the instructions given to him, Josiah sold the horse and waggon, and purchased a large boat, called in that region a yawl, in which he embarked the whole party, and floated down the river. This mode of locomotion was much more agreeable than tramping along, foot-sore, day after day, at the rate they had been limited to ever since leaving home. Very little labour at the oars was necessary, for the current floated them steadily along, and they had ample leisure to rest and recruit their strength.

A great trouble now arose, altogether new and unexpected to Josiah. They were passing along the shore of the State of Ohio, one of the northern free states, and were repeatedly told by persons who entered into conversation with them that they were no longer slaves, but free men, if they chose to be so. At Cincinnati, especially, as soon as they arrived there, crowds of coloured people gathered about them, and almost insisted on the party remaining with them; telling them they were fools to think of going on, and surrendering themselves to a new owner; that now they could be their own masters, and easily put themselves out

Page 60

of reach of pursuit. "It was a great temptation," said Josiah. "I saw the people under me were getting much excited, and signs of insubordination began to manifest themselves. I began, too, to feel my own resolution giving way. Freedom had ever been an object of my ambition, though no other means of obtaining it but purchasing myself had occurred to me. I had never dreamed of running away. I had a sentiment of honour on the subject. The duties of the slave to his master, as appointed over him in the Lord, I had always heard urged by ministers and religious men; it seemed to me like outright stealing to run away. And now I thought the devil was getting the upper hand of me. The idea was very entrancing that the coast was clear for a run for freedom; that I might liberate my companions, carry off my wife and children, and some day possess a house and land, and be no longer despised and abused as a slave. Still my notions of right were against it. I had promised my master to take his property to Kentucky, and commit it to the care of his brother Amos; and how could I break my word? Pride, too, came in to confirm me in my resolution to be faithful to my master's interests. I had undertaken what appeared to me to be a great thing. My vanity had been flattered all along the road by hearing myself

Page 61

praised. I thought it would be a feather in my cap to carry through this expedition successfully; and I had often painted the scene, in my imagination, of the final surrender of my charge to Master Amos, and the immense admiration and respect with which he would regard me.

"Under these impressions, and seeing that the allurements of the crowd were producing a manifest effect on my charge, I sternly assumed the captain, and ordered the boat to be pushed off into the stream. A shower of execrations at my folly followed me from the shore; but the Negroes under me, accustomed to obey, and, alas! too degraded and ignorant of the advantages of liberty to understand what they were forfeiting, offered no resistance to my command.

"Often since that day has my soul been pierced with bitter anguish at the thought of having been thus instrumental in consigning to the infernal bondage of slavery so many of my fellow beings. I have wrestled in prayer with God for forgiveness of this sin. Having experienced myself the sweetness of liberty, and knowing too well the after misery of numbers of them, my infatuation has seemed to me almost unpardonable. But I console myself with the thought that I acted according to my best light, though the light that was in me was darkness. Those were my days of ignorance.

Page 62

I knew not the glory of free manhood. I was ignorant of the fact that the title of the slave-holder is only robbery and outrage."