Narrative of the Sufferings of Lewis Clarke,

During a Captivity of More Than Twenty-Five Years,

Among the Algerines of Kentucky,

One of the So Called

Christian States of America. Dictated by Himself:

Electronic Edition.

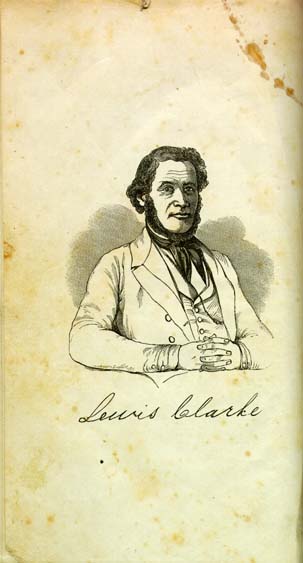

Lewis Garrard Clarke, 1812-1897

Funding from the National

Endowment for the Humanities

supported

the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Chris Hill

Images scanned by

Chris Hill and Kevin O'Kelly

Text encoded by

Kevin O'Kelly and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 200 K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Call number T E444 .C59 (Treasure Room Collection, James E. Shepard Memorial Library, North Carolina Central University)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American

South.

James E. Shepard

Memorial Library, North Carolina Central University,

provided the text for the electronic publication of

this title.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as --

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and

Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

- LC Subject Headings:

- Clarke, Lewis Garrard, 1812-1897.

- African Americans -- Kentucky -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Kentucky -- Biography.

- Fugitive slaves -- Kentucky -- Biography.

- Slavery -- Kentucky -- History -- 19th century.

- Plantation life -- Kentucky -- History -- 19th century.

- Slaves' writings, American -- Kentucky.

- 2000-2-16,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-08-31,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-08-29,

Kevin O'Kelley

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-08-02,

Chris Hill

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

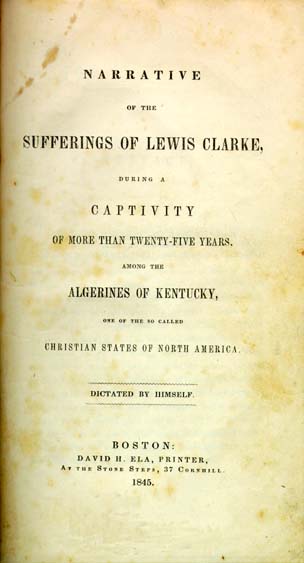

NARRATIVE

OF THE

SUFFERINGS OF LEWIS CLARKE,

DURING A

CAPTIVITY

OF MORE THAN TWENTY-FIVE YEARS,

AMONG THE

ALGERINES OF KENTUCKY,

ONE OF THE SO CALLED

CHRISTIAN STATES OF NORTH AMERICA.

DICTATED BY HIMSELF.

BOSTON:

DAVID H. ELA, PRINTER,

AT THE STONE STEPS, 37 CORNHILL.

1845.

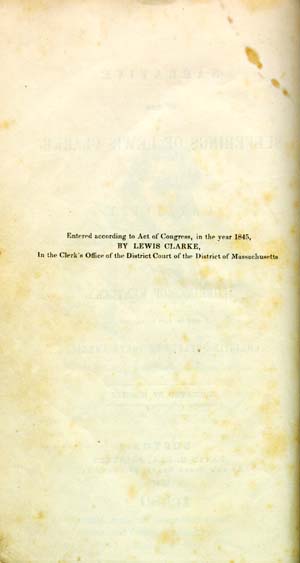

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year

1845,

BY LEWIS CLARKE,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of

Massachusetts.

Page v

PREFACE.

I FIRST became acquainted with LEWIS CLARKE in December, 1842. I well remember the deep impression made upon my mind on hearing his Narrative from his own lips. It gave me a new and more vivid impression of the wrongs of Slavery than I had ever before felt. Evidently a person of good native talents and of deep sensibilities, such a mind had been under the dark cloud of slavery for more than twenty-five years. Letters, reading, all the modes of thought awakened by them, had been utterly hid from his eyes; and yet his mind had evidently been active, and trains of thought were flowing through it, which he was utterly unable to express. I well remember too the wave on wave of deep feeling excited in an audience of more than a thousand persons, at Hallowell, Me., as they listened to his story and looked upon his energetic and manly countenance, and wondered if the dark cloud of slavery could cover up--hide from the world, and degrade to the condition of brutes, such immortal minds. His story, there and wherever since told, has aroused the most utter abhorrence of the Slave System.

Page vi

For the two last years, I have had the most ample opportunity of becoming acquainted with Mr. Clarke. He has made this place his home, when not engaged in giving to public audiences the story of his sufferings, and the sufferings of his fellow slaves. Soon after he came to Ohio, by the faithful instruction of pious friends, he was led, as he believes, to see himself a sinner before God, and to seek pardon and forgiveness through the precious blood of the Lamb. He has ever manifested an ardent thirst for religious, as well as for other kinds of knowledge. In the opinion of all those best acquainted with him, he has maintained the character of a sincere Christian. That he is what he professes to be,--a slave escaped from the grasp of avarice and power,-- there is not the least shadow of doubt. His narrative bears the most conclusive internal evidence of its truth. Persons of discriminating minds have heard it repeatedly, under a great variety of circumstances, and the story, in all substantial respects, has been always the same. He has been repeatedly recognized in the Free States by persons who knew him in Kentucky, when a slave. During the summer of 1844, Cassius M. Clay visited Boston, and on seeing Milton Clarke, recognized him as one of the Clarke family, well known to him in Kentucky. Indeed, nothing can be more surely established than the fact that Lewis and Milton Clarke are no impostors. For three years they have been engaged in telling their story in seven or eight different States, and no one has appeared to make an attempt to contradict them. The capture of Milton in Ohio, by the kidnappers, as a slave, makes assurance doubly strong. Wherever they have told their story, large audiences have collected, and everywhere

Page vii

they have been listened to with great interest and satisfaction.

Cyrus is fully equal to either of the brothers in sprightliness of mind--is withal a great wit, and would make an admirable lecturer, but for an unfortunate impediment in his speech. They all feel deeply the wrongs they have suffered, and are by no means forgetful of their brethren in bonds.When Lewis first came to this place, he was frequently noticed in silent and deep meditation. On being asked what he was thinking of, he would reply, "O, of the poor slaves! Here I am free, and they suffering so much."Bitter tears are often seen coursing down his manly cheeks, as he recurs to the scenes of his early suffering. Many persons, who have heard him lecture, have expressed a strong desire that his story might he recorded in a connected form. He has therefore concluded to have it printed. He was anxious to add facts from other witnesses, and some appeals from other hearts, if by any means he might awaken more hearts to feel for his downtrodden brethren. Nothing seems to grieve him to the heart like finding a minister of the Gospel, or a professed Christian, indifferent to the condition of the slave. As to doing much for the instruction of the minds of the slaves, or for the salvation of their souls, till they are EMANCIPATED, restored to the rights of men, in his opinion it is utterly impossible.

When the master, or his representative, the man who justifies slaveholding, comes with the whip in one hand and the Bible in the other, the slave says, at least in his heart, lay down one or the other. Either make the tree good and the fruit good, or else both corrupt together. Slaves do not believe that THE RELIGION

Page viii

which is from God, bears whips and chains. They ask emphatically concerning their FATHER in Heaven,

"Has HE bid you buy and sell us,

Speaking from his throne, the sky."

For the facts contained in the following Narrative, Mr. Clarke is of course alone responsible. Yet having had the most ample opportunities for testing his accuracy, I do not hesitate to say, that I have not a shadow of doubt, but in all material points every word is true. Much of it is in his own language, and all of it according to his own dictation.

J. C. LOVEJOY.

Cambridgeport, April, 1845.Page 9

NARRATIVE OF LEWIS CLARKE.

I WAS born in March, as near as I can ascertain, in the year 1815, in Madison County, Kentucky, about seven miles from Richmond, upon the plantation of my grandfather, Samuel Campbell. He was considered a very respectable man among his fellow robbers-- the slaveholders. It did not render him less honorable in their eyes, that he took to his bed Mary, his slave, perhaps half white, by whom he had one daughter,-- LETITIA CAMPBELL. This was before his marriage.

My Father was from "beyond the flood"-- from Scotland, and by trade a weaver. He had been married in his own country, and lost his wife, who left to him, as I have been told, two sons. He came to this country in time to be in the earliest scenes of the American Revolution. He was at the Battle of Bunker Hill, and continued in the army to the close of the war. About the year 1800, or before, he came to Kentucky, and married Miss Letitia Campbell, then held as a slave by her dear and affectionate father. My father died, as near as I can recollect, when I was about ten or twelve years of age. He had received a wound in the war which made him lame as

Page 10

long as he lived. I have often heard him tell of Scotland, sing the merry songs of his native land, and long to see its hills once more.

Mr. Campbell promised my father that his daughter Letitia should be made free in his will. It was with this promise that he married her. and I have no doubt that Mr. Campbell was as good as his word, and that by his will, my mother and her nine children were made free. But ten persons in one family, each worth three hundred dollars, are not easily set free among those accustomed to live by continued robbery. We did not, therefore, by an instrument from the hand of the dead, escape the avaricious grab of the slaveholder. It is the common belief that the will was destroyed by the heirs of Mr. Campbell.

The night in which I was born, I have been told, was dark and terrible, black as the night for which Job prayed, when he besought the clouds to pitch their tent round about the place of his birth; and my life of slavery was but too exactly prefigured by the stormy elements that hovered over the first hour of my being. It was with great difficulty that any one could be urged out for a necessary attendant for my mother. At length one of the sons of Mr. Campbell, William, by the promise from his mother of the child that should be born, was induced to make an effort to obtain the necessary assistance. By going five or six miles he obtained a female professor of the couch.

William Campbell, by virtue of this title, always claimed me as his property. And well would it have been for me, if this claim had been regarded. At the age of six or seven years I fell into the hands of his sister, Mrs. Betsey Banton, whose character will be best known

Page 11

when I have told the horrid wrongs which she heaped upon me for ten years. If there are any she spirits that come up from hell, and take possession of one part of mankind, I am sure she is one of that sort. I was consigned to her under the following circumstances: When she was married, there was given her, as part of her dower, as is common among the Algerines of Kentucky, a girl by the name of Ruth, about fourteen or fifteen years old. In a short time Ruth was dejected and injured, by beating and abuse of different kinds, so that she was sold for a half-fool to the more tender mercies of the sugar planter in Louisiana. The amiable Mrs. Betsey obtained then, on loan from her parents, another slave named Phillis. In six months she had suffered so severely under the hand of this monster woman, that she made an attempt to kill herself, and was taken home by the parents of Mrs. Banton. This produced a regular slave-holding family brawl--a regular war of four years, between the mild and peaceable Mrs. B. and her own parents. These wars are very common among the Algerines in Kentucky; indeed, slave-holders have not arrived at that degree of civilization that enables them to live in tolerable peace, though united by the nearest family ties. In them is fulfilled what I have heard read in the Bible: The father is against the son, and the daughter-in-law against the mother-in-law, and their foes are of their own household. Some of the slaveholders may have a wide house; but one of the cat-handed, snake-eyed, brawling women, which slavery produces, can fill it from cellar to garret. I have heard every place I could get into any way, ring with their screech-owl voices. Of all the animals on the face of this earth, I am most afraid of a real mad, passionate,

Page 12

raving, slaveholding woman. Some body told me once, that Edmund Burke declared, that the natives of India fled to the jungles, among tigers and lions, to escape the more barbarous cruelty of Warren Hastings. I am sure I would sooner lie down to sleep by the side of tigers, than near a raging-mad slave woman. But I must go back to sweet Mrs. Banton. I have been describing her in the abstract;--I will give a full-grown portrait of her, right away. For four years after the trouble about Phillis, she never came near her father's house. At the end of this period another of the amiable sisters was to be married, and sister Betsey could not repress the tide of curiosity, urging her to be present at the nuptial ceremonies. Beside, she had another motive. Either shrewdly suspecting that she might deserve less than any member of the family, or that some ungrounded partiality would be manifested toward her sister, she determined at all hazards to be present, and see that the scales which weighed out the children of the plantation should be held with even hand. The wedding day was appointed--the sons and daughters of this joyful occasion were gathered together, and then came also the fair-faced, but black-hearted Mrs. B. Satan among the Sons of God was never less welcome, than this fury among her kindred. They all knew what she came for,--to make mischief if possible. "Well now, if there aint Bets," exclaimed the old lady. The father was moody and silent, knowing that she inherited largely of the disposition of her mother; but he had experienced too many of her retorts of courtesy to say as much, for dear experience had taught him the discretion of silence. The brothers smiled at the prospect of fun and frolick, the sisters trembled for fear, and word flew round among the

Page 13

slaves, "The old she-bear has come home! look out! look out!"

The wedding went forward. Polly, a very good sort of a girl to be raised in that region, was married, and received, as the first installment of her dower, a girl and a boy. Now was the time for Mrs. Banton, sweet good Mrs. Banton. "Poll has a girl and a boy, and I only had that fool of a girl ; I reckon if I go home without a boy too, this house wont be left standing."

This was said, too, while the sugar of the wedding cake was yet melting upon her tongue ; how the bitter words would flow when the guests had retired, all began to imagine. To arrest this whirlwind of rising passion, her mother promised any boy upon the plantation, to be taken home on her return. Now my evil star was right in the top of the sky. Every boy was ordered in, to pass before this female sorceress, that she might select a victim for her unprovoked malice, and on whom to pour the vials of her wrath for years. I was that unlucky fellow. Mr. Campbell, my grandfather, objected, because it would divide a family, and offered her Moses, whose father and mother had been sold South. Mrs. Campbell put in for William's claim, dated ante-natum--before I was born ; but objections and claims of every kind were swept away by the wild passion and shrill-toned voice of Mrs. B. Me she would have, and none else. Mr. Campbell went out to hunt and drive away bad thoughts-- the old lady became quiet, for she was sure none of her blood run in my veins, and if there was any of her husband's there, it was no fault of hers. I was too young, only seven years of age, to understand what was going on. But my poor and affectionate mother understood and appreciated it all. When

Page 14

she left the kitchen of the Mansion House, where she was employed as cook, and came home to her own little cottage, the tear of anguish was in her eye, and the image of sorrow upon every feature of her face. She knew the female Nero, whose rod was now to be over me. That night sleep departed from her eyes; with the youngest child clasped firmly to her bosom, she spent the night in walking the floor, coming ever and anon to lift up the clothes and look at me and my poor brother who lay sleeping together. Sleeping, I said ; brother slept, but not I. I saw my mother when she first came to me; and I could not sleep. The vision of that night, its deep, ineffaceable impression is now before my mind with all the distinctness of yesterday. In the morning I was put into the carriage with Mrs. B. and her children, and my weary pilgrimage of suffering was fairly begun. It was her business on the road for about twenty five or thirty miles to initiate her children into the art of tormenting their new victim. I was seated upon the bottom of the carriage, and these little imps were employed in pinching me, pulling my ears and hair, and they were stirred up by their mother like a litter of young wolves to torment me in every way possible. In the mean time I was compelled by the old she wolf, to call them "Master," "Mistress," and bow to them and obey them at the first call.

During that day, I had indeed no very agreeable foreboding of the torments to come; but sad as were my anticipations, the reality was infinitely beyond them. Infinitely more bitter than death were the cruelties I experienced at the hand of this merciless woman. Save from one or two slaves on the plantation, during my ten years of captivity here, I scarcely heard a kind word, or saw a smile

Page 15

toward me from any living being. And now that I am where people look kind and act kindly toward me, it seems like a dream. I hardly seem to be in the same world that I was then. When I first got into the free States and saw everybody look like they loved one another, sure enough I thought this must be the "Heaven" of LOVE I had heard something about. But I must go back to what I suffered from that wicked woman. It is hard work to keep the mind upon it; I hate to think it over-- but I must tell it-- the world must know what is done in Kentucky. I cannot, however, tell all the ways, by which she tormented me, I can only give a few instances of my suffering as specimens of the whole. A book of a thousand pages would not be large enough to tell of all the tears I shed, and the sufferings endured in THAT TEN YEARS OF PURGATORY.

A very trivial offence was sufficient to call forth a great burst of indignation from this woman of ungoverned passions. In my simplicity, I put my lips to the same vessel and drank out of it from which her children were accustomed to drink. She expressed her utter abhorrence of such an act, by throwing my head violently back, and dashing into my face two dippers of water. The shower of water was followed by a heavier shower of kicks--yes, delicate reader, this lady did not hesitate to kick, as well as cuff in a very plentiful manner-- but the words bitter and cutting that followed were like a storm of hail upon my young heart. "She would teach me better manners than that--she would let me know I was to be brought up to her hand--she would have one slave that knew his place; if I wanted water, go to the spring, and not drink there in the house." This was new times for me-- for

Page 16

some days I was completely benumbed with my sorrow. I could neither eat nor sleep. If there is any human being on earth, who has been so blessed as never to have tasted the cup of sorrow, and therefore is unable to conceive of suffering, if there be one so lost to all feeling as even to say that the slaves do not suffer, when families are separated, let such an one go to the ragged quilt which was my couch and pillow and stand there night after night, for long weary hours, and see the bitter tears streaming down the face of that more than orphan boy, while with half suppressed sighs and sobs, he calls again and again upon his absent mother.

"Say, Mother, wast thou conscious of the tears I shed,--

Hovered thy spirit o'er thy sorrowing son?

Wretch even then! Life's journey just begun."

Let him stand by that couch of bitter sorrow through the

terribly lonely night, and then wring out the wet end of those

rags, and see how many tears yet remain, after the burning

temples had absorbed all they could. He will not doubt, he

cannot doubt but the slave has feeling. But I find myself

running away again from Mrs. Banton--and I don't much

wonder neither.

There were several children in the family, and my first main business was to wait upon them. Another young slave and myself have often been compelled to sit up by turns all night, to rock the cradle of a little, peevish scion of slavery. If the cradle was stopped, the moment they awoke a dolorous cry was sent forth to mother or father, that Lewis had gone to sleep. The reply to this call, would be a direction from the mother, for these petty tyrants to get up and take the whip, and give the good-for-nothing

Page 17

scoundrel a smart whipping. This was the midnight pastime of a child ten or twelve years old. What might you expect of the future man?

There were four house-slaves in this family, including myself, and though we had not, in all respects, so hard work as the field hands, yet in many things our condition was much worse. We were constantly exposed to the whims and passions of every member of the family; from the least to the greatest their anger was wreaked upon us. Nor was our life an easy one, in the hours of our toil or in the amount of labor performed. We were always required to sit up until all the family had retired; then we must be up at early dawn in summer, and before day in winter. If we failed, through weariness or for any other reason, to appear at the first morning summons, we were sure to have our hearing quickened by a severe chastisement. Such horror has seized me, lest I might not hear the first shrill call, that I have often in dreams fancied I heard that unwelcome call, and have leaped from my couch and walked through the house and out of it before I awoke. I have gone and called the other slaves, in my sleep, and asked them if they did not hear master call. Never, while I live, will the remembrance of those long, bitter nights of fear pass from my mind.

But I want to give you a few specimens of the abuse which I received. During the ten years that I lived with Mrs. Banton, I do not think there were as many days, when she was at home, that I, or some other slave, did not receive some kind of beating or abuse at her hands. It seemed as though she could not live nor sleep unless some poor back was smarting, some head beating with pain, or some eye filled with tears, around her. Her tender mercies

Page 18

were indeed cruel. She brought up her children to imitate her example. Two of them manifested some dislike to the cruelties taught them by their mother, but they never stood high in favor with her; indeed, any thing like humanity or kindness to a slave, was looked upon by her as a great offence.

Her instruments of torture were ordinarily the raw hide, or a bunch of hickory-sprouts seasoned in the fire and tied together. But if these were not at hand, nothing came amiss. She could relish a beating with a chair, the broom, tongs, shovel, shears, knife-handle, the heavy heel of her slipper ; her zeal was so active in these barbarous inflictions, that her invention was wonderfully quick, and some way of inflicting the requisite torture was soon found out.

One instrument of torture is worthy of particular description. This was an oak club, a foot and a half in length and an inch and a half square. With this delicate weapon she would beat us upon the hands and upon the feet until they were blistered. This instrument was carefully preserved for a period of four years. Every day, for that time, I was compelled to see that hated tool of cruelty lying in the chair by my side. The least degree of delinquency either in not doing all the appointed work, or in look or behavior, was visited with a beating from this oak club. That club will always be a prominent object in the picture of horrors of my life of more than twenty years of bitter bondage.

When about nine years old I was sent in the evening to catch and kill a turkey. They were securely sleeping in a tree-- their accustomed resting place for the night. I approached as cautiously as possible, selected the victim I was directed to catch, but just as I grasped him in my

Page 19

hand, my foot slipped and he made his escape from the tree and fled beyond my reach. I returned with a heavy heart to my mistress with the story of my misfortune. She was enraged beyond measure. She determined at once that I should have a whipping of the worst kind, and she was bent upon adding all the aggravations possible. Master had gone to bed drunk., and was now as fast asleep as drunkards ever are. At any rate he was filling the house with the noise of his snoring and with the perfume of his breath. I was ordered to go and call him-- wake him up--and ask him to be kind enough to give me fifty good smart lashes. To be whipped is bad enough-- to ask for it is worse-- to ask a drunken man to whip you is too bad. I would sooner have gone to a nest of rattlesnakes, than to the bed of this drunkard. But go I must. Softly I crept along, and gently shaking his arm, said with a trembling voice, "Master, Master, Mistress wants you to wake up." This did not go the extent of her command, and in a great fury she called out--"What, you wont ask him to whip you, will you?" I then added "Mistress wants you to give me fifty lashes." A bear at the smell of a lamb, was never roused quicker. "Yes, yes, that I will; I'll give you such a whipping as you will never want again." And sure enough so he did. He sprang from the bed, seized me by the hair, lashed me with a handful of switches, threw me my whole length upon the floor, beat, kicked and cuffed me worse than he would a dog, and then threw me, with all his strength out of the door more dead than alive. There I lay for a long time scarcely able and not daring to move, till I could hear no sound of the furies within, and then crept to my couch, longing for death to put an end to my misery. I had no friend in the

Page 20

world to whom I could utter one word of complaint, or to whom I could look for protection.

Mr. Banton owned a blacksmith shop in which he spent some of his time, though he was not a very efficient hand at the forge. One day Mistress told me to go over to the shop and let Master give me a flogging. I knew the mode of punishing there too well. I would rather die than go. The poor fellow who worked in the shop, a very skilful workman, neglected one day to pay over a half dollar that he had received of a customer for a job of work. This was quite an unpardonable offence. No right is more strictly maintained by slave holders, than the right they have to every cent of the slave's wages. The slave kept fifty cents of his own wages in his pocket one night. This came to the knowledge of the Master. He called for the money and it was not spent-- it was handed to him; but there was the horrid intention of keeping it. The enraged Master put a handful of nail rods into the fire, and When they were red hot took them out, and cooled one after another of them in the blood and flesh of the poor slave's back. I knew this was the shop mode of punishment; I would not go, and Mr. Banton came home, and his amiable lady told him the story of my refusal ; he broke forth in a great rage, and gave me a most unmerciful beating, adding that if I had come, he would have burned the hot nail rods into my back.

Mrs. Banton, as is common among slave holding women, seemed to hate and abuse me all the more, because I had some of the blood of her father in my veins. There is no slaves that are so badly abused, as those that are related to some of the women--or the children of their own husband; it seems as though they never could hate these quite bad enough. My sisters were as white and good looking

Page 21

as any of the young ladies in Kentucky. It happened once of a time, that a young man called at the house of Mr. Campbell, to see a sister of Mrs. Banton. Seeing one of my sisters in the house and pretty well dressed, with a strong family look, he thought it was Miss Campbell, and with that supposition addressed some conversation to her which he had intended for the private ear of Miss C. The mistake was noised abroad and occasioned some amusement to young people. Mrs. Banton heard, it made her cauldron of wrath sizzling hot-- every thing that diverted and amused other people seemed to enrage her. There are hot springs in Kentucky, she was just like one of them, only chuckfull of boiling poison.

She must wreak her vengeance for this innocent mistake of the young man, upon me. "She would fix me so that nobody should ever think I was white." Accordingly in a burning hot day, she made me take off every rag of clothes, go out into the garden and pick herbs for hours-- in order to burn me black. When I went out she threw cold water on me so that the sun might take effect upon me, when I came in she gave me a severe beating on my blistered back.

After I had lived with Mrs. B. three or four years I was put to spinning hemp, flax and tow, on an old fashioned foot wheel. There were four or five slaves at this business a good part of the time. We were kept at our work from daylight to dark in summer, from long before day to nine or ten o'clock in the evening in winter. Mrs. Banton for the most part was near or kept continually passing in and out to see that each of us performed as much work as she thought we ought to do. Being young and sick at heart all the time, it was very hard work to go

Page 22

through the day and evening and not suffer exceedingly for want of more sleep. Very often too I was compelled to work beyond the ordinary hour to finish the appointed task of the day. Sometimes I found it impossible not to drop asleep at the wheel.

On these occasions Mrs. B. had her peculiar contrivances for keeping us awake. She would sometimes sit by the hour with a dipper of vinegar and salt, and throw it in my eyes to keep them open. My hair was pulled till there was no longer any pain from that source. And I can now suffer myself to be lifted by the hair of the head, without experiencing the least pain.

She very often kept me from getting water to satisfy my thirst, and in one instance kept me for two entire days without a particle of food.

But all my severe labor, bitter and cruel punishments for these ten years of captivity with this worse than Arab family, all these were as nothing to the sufferings experienced by being separated from my mother, brothers and sisters; the same things, with them near to sympathize with me, to hear my story of sorrow, would have been comparatively tolerable.

They were distant only about thirty miles, and yet in ten long, lonely years of childhood, I was only permitted to see them three times.

My mother occasionally found an opportunity to send me some token of remembrance and affection, a sugar plum or an apple, but I scarcely ever ate them-- they were laid up and handled and wept over till they wasted away in my hand.

My thoughts continually by day and my dreams by night were of mother and home, and the horror experienced

Page 23

in the morning, when I awoke and behold it was a dream, is beyond the power of language to describe.

But I am about to leave the den of robbers where I had been so long imprisoned. I cannot however call the reader from his new and pleasant acquaintance with this amiable pair, without giving a few more incidents of their history. When this is done, and I have taken great pains, as I shall do to put a copy of this portrait in the hands of this Mrs. B., I shall bid her farewell. If she sees something awfully hideous in her picture as here presented, she will be constrained to acknowledge it is true to nature-- I have given it from no malice, no feeling of resentment toward her, but that the world may know what is done by slavery, and that slave holders may know, that their crimes will come to light. I hope and pray that Mrs. B. will repent of her many and aggravated sins before it is too late.

The scenes between her and her husband while I was with them strongly illustrate the remark of Jefferson, that slavery fosters the worst passions of the master. Scarcely a day passed in which bitter words were not bandied from one to the other. I have seen Mrs. B. with a large knife drawn in her right hand, the other upon the collar of her husband, swearing and threatening to cut him square in two. They both drank freely, and swore like highwaymen. He was a gambler and a counterfeiter. I have seen and handled his moulds and his false coin. They finally quarrelled openly and separated, and the last I knew of them, he was living a sort of poor vagabond life in his native State, and she was engaged in a protracted law suit with some of her former friends about her father's property.

Of course such habits did not produce great thrift in their worldly condition, and myself and other slaves were

Page 24

mortgaged from time to time to make up the deficiency between their income and expenses. I was transferred at the age of sixteen or seventeen to a Mr. K., whose name I forbear to mention, lest if he or any other man should ever claim property where they never had any, this my own testimony might be brought in to aid their wicked purposes.

In the exchange of masters, my condition was in many respects greatly improved--I was free at any rate from that kind of suffering experienced at the hand of Mrs. B. as though she delighted in cruelty for its own sake. My situation however with Mr. K. was far from enviable. Taken from the work in and around the house, and put at once at that early age to the constant work of a full grown man, I found it not an easy task always to escape the lash of the overseer. In the four or five years that I was with this man, the overseers were often changed. Sometimes we had a man that seemed to have some consideration, some mercy, but generally their eye seemed to be fixed upon one object, and that was to get the greatest possible amount of work out of every slave upon the plantation. When stooping to clear the tobacco plants from the worms which infest them, a work which draws most cruelly upon the back, some of these men would not allow us a moment to rest at the end of the row, but at the crack of the whip we were compelled to jump to our places from row to row for hours; while the poor back was crying out with torture. Any complaint or remonstrance under such circumstances is sure to be answered in no other way than by the lash. As a sheep before her shearers is dumb, so a slave is not permitted to open his mouth.

There were about one hundred and fifty slaves upon

Page 25

this plantation. Generally we had enough in quantity of food. We had however but two meals a day, of corn meal bread, and soup, or meat of the poorest kind. Very often so little care had been taken to cure and preserve the bacon, that when it came to us, though it had been fairly killed once, it was more alive than dead. Occasionally we had some refreshment over and above the two meals, but this was extra, beyond the rules of the plantation. And to balance this gratuity, we were also frequently deprived of our food as a punishment. We suffered greatly, too, for want of water. The slave drivers have the notion that slaves are more healthy if allowed to drink but little, than they are if freely allowed nature's beverage. The slaves quite as confidently cherish the opinion, that if the master would drink less peach brandy and whisky, and give the slave more water, it would be better all round. As it is, the more the master and overseer drink, the less they seem to think the slave needs.

In the winter we took our meals before day in the morning and after work at night. In the summer at about nine o'clock in the morning and at two in the afternoon. When we were cheated out of our two meals a day, either by the cruelty or caprice of the overseer, we always felt it a kind of special duty and privilege to make up in some way the deficiency. To accomplish this we had many devices. And we sometimes resorted to our peculiar methods, when incited only by a desire to taste greater variety than our ordinary bill of fare afforded.

This sometimes lead to very disastrous results. The poor slave, who was caught with a chicken or a pig killed from the plantation, had his back scored most unmercifully. Nevertheless, the pigs would die without being sick or

Page 26

squealing once, and the hens, chickens and turkeys, sometimes disappeared and never stuck up a feather to tell where they were buried. The old goose would sometimes exchange her whole nest of eggs for round pebbles; and patient as that animal is, this quality was exhausted, and she was obliged to leave her nest with no train of offspring behind her.

One old slave woman upon this plantation was altogether too keen and shrewd for the best of them. She would go out to the corn crib, with her basket, watch her opportunity, with one effective blow pop over a little pig, slip him into her basket and put the cobs on top, trudge off to her cabin, and look just as innocent as though she had a right to eat of the work of her own hands. It was a kind of first principle, too, in her code of morals, that they that worked had a right to eat. The moral of all questions in relation to taking food was easily settled by Aunt Peggy. The only question with her was, how and when to do it.

It could not be done openly, that was plain; it must be done, secretly, if not in the day time by all means in the night. With a dead pig in the cabin, and the water all hot for scalding, she was at one time warned by her son that the Philistines were upon her. Her resources were fully equally to the sudden emergency, quick as thought, the pig was thrown into the boiling kettle, a door was put over it, her daughter seated upon it, and with a good thick quilt around her, the overseer found little Phillis taking a steam bath for a terrible cold. The daughter acted well her part, groaned sadly, the mother was very busy in tucking in the quilt, and the overseer was blinded, and went away without seeing a bristle of the pig.

Aunt P. cooked for herself, for another slave named

Page 27

George, and for me. George was very successful in bringing home his share of the plunder. He could capture a pig or a turkey without exciting the least suspicion. The old lady often rallied me for want of courage for such enterprizes. At length, I summoned resolution one rainy night, and determined there should be one from the herd of swine brought home by my hands. I went to the crib of corn, got my ear to shell, and my cart stake to despatch a little roaster. I raised my arm to strike, summoned courage again and again, but to no purpose. The scattered kernels were all picked up and no blow struck. Again I visited the crib, selected my victim, and struck-- the blow glanced upon the side of the head, and instead of falling, he ran off squealing louder than ever I heard a pig squeal before. I ran as fast in an opposite direction, made a large circuit and reached the cabin--emptied the hot water and made for my couch as soon as possible. I escaped detection, and only suffered from the ridicule of old Peggy and young George.

Poor Jess, upon the same plantation, did not so easily escape. More successful in his effort, he killed his pig, but he was found out. He was hung up by the hands, with a rail between his feet, and full three hundred lashes scored in upon his naked back. For a long time his life hung in doubt, and his poor wife, for becoming a partaker after the fact, was most severely beaten.

Another slave, employed as a driver upon the plantation. was compelled to whip his own wife, for a similar offence, so severely that she never recovered from the cruelty. She was literally whipped to death by her own husband.

A slave, called Hall, the hostler on the plantation, made a successful sally one night upon the animals forbidden to

Page 28

the Jews. The next day he went into the barn loft and fell asleep. While sleeping over his abundant supper, and dreaming perhaps of his feast, he heard the shrill voice of his master, crying out "the hogs are at the horse trough--where is Hall." The "hogs and Hall" coupled together, were enough for the poor fellow. He sprung from the hay and made the best of his way off the plantation. He was gone six months, and at the end of this period he procured the intercession of the son-in-law of his master, and returned, escaping the ordinary punishment. But the transgression was laid up. Slave holders seldom forgive, they only postpone the time of revenge. When about to be severely flogged for some pretended offence, he took two of his grandsons and escaped as far towards Canada as Indiana. He was followed, captured, brought back and whipped most horribly. All the old score had been treasured up against him, and his poor back atoned for the whole at once.

On this plantation was a slave named Sam, whose wife lived a few miles distant, and Sam was very seldom permitted to go and see his family. He worked in the blacksmith shop. For a small offence, he was hung up by the hands, a rail between his feet, and whipped in turn by the master, overseer and one of the waiters, till his back was torn all to pieces, and in less than two months Sam was in his grave. His last words were, "Mother, tell master he has killed me at last for nothing, but tell him if God will forgive him, I will."

A very poor white woman lived within about a mile of the plantation house. A female slave named Flora, knowing she was in a very suffering condition, shelled out a peck of corn and carried it to her in the night. Next day

Page 29

the old man found it out, and this deed of charity was atoned for by one hundred and fifty lashes upon the bare back of poor Flora.

The master with whom I now lived, was a very passionate man. At one time he thought the work on the plantation did not go on as it ought. One morning, when he and the overseer waked up from a drunken frolick, they swore the hands should not eat a morsel of any thing, till a field of wheat of some sixty acres was all cradled. There were from thirty to forty hands to do the work. We were driven on to the extent of our strength, and although a brook ran through the field, not one of us was permitted to stop and taste a drop of water. Some of the men were so exhausted, that they reeled for very weakness; two of the women fainted, and one of them was severely whipped to revive her. They were at last carried helpless from the field and thrown down under the shade of a tree. At about five o'clock in the afternoon the wheat was all cut and we were permitted to eat. Our suffering for want of water was excruciating. I trembled all over from the inward gnawing of hunger and from burning thirst.

In view of the sufferings of this day we felt fully justified in making a foraging expedition upon the milk room that night. And when master and overseer and all hands were locked up in sleep, ten or twelve of us went down to the spring house,--a house built over a spring to keep the milk and other things cool. We pressed altogether against the door, and open it came. We found half of a good, baked pig, plenty of cream, milk and other delicacies, and as we felt in some measure delegated to represent all that had been cheated of their meals the day before, we ate plentifully. But after a successful plundering expedition

Page 30

within the gates of the enemy's camp, it is not easy always to cover the retreat. We had a reserve in the pasture for this purpose. We went up to the herd of swine, and with a milk pail in hand, it was easy to persuade them there was more where that came from, and the whole tribe followed readily into the spring house, and we left them there to wash the dishes and wipe up the floor, while we retired to rest. This was not malice in us; we did not love the waste which the hogs made; but we must have something to eat, to pay for the cruel and reluctant fast; and when we had obtained this, we must of course cover up our track. They watch us narrowly; and to take an egg, a pound of meat, or anything else, however hungry we may be, is considered a great crime,--we are compelled therefore, to waste a good deal sometimes, to get a little.

I lived with this Mr. K. about four or five years. I then fell into the hands of his son. He was a drinking, ignorant man, but not so cruel as his father. Of him I hired my time at $12 a month, boarded and clothed myself. To meet my payments, I split rails, burned coal, peddled grass seed, and took hold of whatever I could find to do. This last master, or owner as he would call himself, died about one year before I left Kentucky. By the administrators I was hired out for a time, and at last put up upon the auction block for sale. No bid could be obtained for me. There were two reasons in the way. One was, there were two or three old mortgages which were not settled, and the second reason given by the bidders was, I had had too many privileges--had been permitted to trade for myself and go over the state-- in short, to use their phrase, I was a "spoilt nigger." And sure enough I was, for all their purposes. I had long thought and dreamed of LIBERTY; I

Page 31

was now determined to make an effort to gain it. No tongue can tell the doubt, the perplexities, the anxiety which a slave feels, when making up his mind upon this subject. If he makes an effort and is not successful, he must be laughed at by his fellows ; he will be beaten unmercifully by the master, and then watched and used the harder for it all his life.

And then if he gets away, who, what will he find? He is ignorant of the world. All the white part of mankind, that he has ever seen, are enemies to him and all his kindred. How can he venture where none but white faces shall greet him? The master tells him that abolitionists decoy slaves off into the free states to catch them and sell them to Louisiana or Mississippi; and if he goes to Canada, the British will put him in a mine under ground, with both eyes put out, for life. How does he know what or whom to believe? A horror of great darkness comes upon him, as he thinks over what may befal him. Long, very long time did I think of escaping before I made the effort.

At length the report was started that I was to be sold for Louisiana. Then I thought it was time to act. My mind was made up. This was about two weeks before I started. The first plan was formed between a slave named Isaac and myself. Isaac proposed to take one of the horses of his mistress, and I was to take my pony, and we were to ride off together, I as master and he as slave. We started together and went on five miles. My want of confidence in the plan induced me to turn back. Poor Isaac plead like a good fellow to go forward. I am satisfied from experience and observation that both of us must have been captured and carried back. I did not know enough at that time to travel and manage a waiter. Every thing

Page 32

would have been done in such an awkward manner that a keen eye would have seen through our plot at once. I did not know the roads, and could not have read the guide boards; and ignorant as many people are in Kentucky, they would have thought it strange to see a man with a waiter, who could not read a guide board. I was sorry to leave Isaac, but I am satisfied I could have done him no good in the way proposed.

After this failure I staid about two weeks, and, after having arranged every thing to the best of my knowledge, I saddled my pony, went into the cellar where I kept my grass seed apparatus, put my clothes into a pair of saddlebags, and them into my seed-bag, and thus equipped set sail for the North Star. O what a day was that to me. This was on Saturday, in August, 1841. I wore my common clothes, and was very careful to avoid special suspicion, as I already imagined the administrator was very watchful of me. The place from which I started was about fifty miles from Lexington. The reason why I do not give the name of the place, and a more accurate location, must be obvious to any one who remembers that in the eye of the law I am yet accounted a slave, and no spot in the United States affords an asylum for the wanderer. True, I feel protected in the hearts of the many warm friends of the slave by whom I am surrounded, but this protection does not come from the LAWS of any one of the United States.

But to return. After riding about fifteen miles, a Baptist minister overtook me on the road, saying, "How do you do, boy; are you free? I always thought you were free, till I saw them try to sell you the other day." I then wished him a thousand miles off, preaching, if he would,

Page 33

to the whole plantation, "Servants obey your masters;" but I wanted neither sermons, questions, nor advice from him. At length I mustered resolution to make some kind of a reply.-- What made you think I was free? He replied, that he had noticed I had great privileges, that I did much as I liked, and that I was almost white. O yes, I said, but there are a great many slaves as white as I am. "Yes," he said, and then went on to name several; among others, one who had lately, as he said, run away. This was touching altogether too near upon what I was thinking of. Now, said I, he must know, or at least reckons, what I am at-- running away.

However, I blushed as little as possible, and made strange of the fellow who had lately run away, as though I knew nothing of it. The old fellow looked at me, as it seemed to me, as though he would read my thoughts. I wondered what in the world a slave could run away for, especially if they had such a chance as I had had for the last few years. He said, "I suppose you would not run away on any account, you are so well treated." O, said I, I do very well--very well, Sir. If you should ever hear that I had run away, be certain it must be because there is some great change in my treatment.

He then began to talk with me about the seed in my bag, and said that he should want to buy some. Then, I thought, he means to get at the truth by looking in my seed-bag, where, sure enough, he would not find grass seed, but the seeds of Liberty. However, he dodged off soon, and left me alone. And although I have heard say, poor company is better than none, I felt much better without him than with him.

When I had gone on about twenty-five miles, I went

Page 34

down into a deep valley by the side of the road, and changed my clothes. I reached Lexington about seven o'clock that evening, and put up with brother Cyrus. As I had often been to Lexington before, and stopped with him, it excited no attention from the slave holding gentry. Moreover, I had a pass from the administrator, of whom I had hired my time. I remained over the Sabbath with Cyrus, and we talked over a great many plans for future operations, if my efforts to escape should be successful. Indeed we talked over all sorts of ways for me to proceed. But both of us were very ignorant of the roads, and of the best way to escape suspicion. And I sometimes wonder, that a slave, so ignorant, so timid, as he is, ever makes the attempt to get his freedom. "Without are foes, within are fears."

Monday morning, bright and early, I set my face in good earnest toward the Ohio River, determined to see and tread the north bank of it, or die in the attempt. I said to myself, one of two things, FREEDOM or DEATH. The first night I reached Mayslick, fifty odd miles from Lexington. Just before reaching this village, I stopped to think over my situation, and determine how I would pass that night. On that night hung all my hopes. I was within twenty miles of Ohio. My horse was unable to reach the river that night. And besides, to travel and attempt to cross the river in the night, would excite suspicion. I must spend the night there. But how? At one time, I thought, I will take my pony out into the field ,and give him some corn, and sleep myself on the grass. But then the dogs will be out in the evening, and if caught under such circumstances, they will take me for a thief if not for a runaway. That will not do. So after

Page 35

weighing the matter all over, I made a plunge right into the heart of the village, and put up at the tavern.

After seeing my pony disposed of, I looked into the barroom, and saw some persons that I thought were from my part of the country, and would know me. I shrunk back with horror. What to do I did not know. I looked across the street, and saw the shop of a silversmith. A thought of a pair of spectacles, to hide my face, struck me. I went across the way, and began to barter for a pair of double eyed green spectacles. When I got them on, they blind-folded me, if they did not others. Every thing seemed right up in my eyes. I hobbled back to the tavern, and called for supper. This I did to avoid notice, for I felt like any thing but eating. At tea I had not learned to measure distances with my new eyes, and the first pass I made with my knife and fork at my plate, went right into my cup. This confused me still more, and, after drinking one cup of tea, I left the table, and got off to bed as soon as possible. But not a wink of sleep that night. All was confusion, dreams, anxiety and trembling.

As soon as day dawned, I called for my horse, paid my reckoning, and was on my way, rejoicing that that night was gone, any how. I made all diligence on my way, and was across the Ohio, and in Aberdeen by noon that day!

What my feelings were when I reached the free shore, can be better imagined than described. I trembled all over with deep emotion, and I could feel my hair rise up on my head. I was on what was called a free soil, among a people who had no slaves. I saw white men at work, and no slave smarting beneath the lash. Every thing was indeed new and wonderful. Not knowing

Page 36

where to find a friend, and being ignorant of the country, --unwilling to inquire lest I should betray my ignorance, it was a whole week before I reached Cincinnati. At one place where I put up, I had a great many more questions put to me than I wished to answer. At another place I was very much annoyed by the officiousness of the landlord, who made it a point to supply every guest with newspapers. I took the copy handed me, and turned it over in a somewhat awkward manner, I suppose. He came to me to point out a Veto, or some other very important news. I thought it best to decline his assistance, and gave up the paper, saying my eyes were not in a fit condition to read much.

At another place, the neighbors, on learning that a Kentuckian was at the tavern, came in great earnestness to find out what my business was. Kentuckians sometimes came there to kidnap their citizens--they were in the habit of watching them close. I at length satisfied them, by assuring them that I was not, nor my father before me, any slave holder at all; but, lest their suspicions should be excited in another direction, I added, my grandfather was a slave holder.

At Cincinnati I found some old acquaintances, and spent several days. In passing through some of the streets, I several times saw a great slave dealer from Kentucky, who knew me, and when I approached him, I was very careful to give him a wide berth. The only advice that I here received, was from a man who had once been a slave. He urged me to sell my pony, go up the river to Portsmouth, then take the canal for Cleveland, and cross over to Canada. I acted upon this suggestion, sold my horse for a small sum, as he was pretty well used up, took passage for

Page 37

Portsmouth, and soon found myself on tire canal-boat, headed for Cleveland. On the boat I became acquainted with a Mr. Conoly, from New York. He was very sick with fever and ague, and as he was a stranger and alone, I took the best possible care of him for a time. One day, in conversation with him, he spoke of the slaves in the most harsh and bitter language, and was especially severe on those who attempted to run away. Thinks I, you are not the man for me to have much to do with. I found the spirit of slaveholding was not all South of the Ohio River.

No sooner had I reached Cleveland, than a trouble came upon me from a very unexpected quarter. A rough, swearing reckless creature in the shape of a man, came up to me and declared I had passed a bad five dollar bill upon his wife, in the boat, and he demanded the silver for it. I had never seen him nor his wife before. He pursued me into the tavern, swearing and threatening all the way. The travellers, that had just arrived at the tavern, were asked to give their names to the clerk, that he might enter them upon the book. He called on me for my name, just as this ruffian was in the midst of his assault upon me. On leaving Kentucky I thought it best for my own security to take a new name, and I had been entered on the boat, as Archibald Campbell. I knew, with such a charge as this man was making against me, it would not do to change my name from the boat to the hotel. At the moment, I could not recollect what I had called myself, and for a few minutes, I was in a complete puzzle. The clerk kept calling, and I made believe deaf, till at length the name popped back again, and I was duly enrolled a guest at the tavern in Cleveland. I had heard before of persons being frightened out of their Christian names, but I was fairly scared

Page 38

out of both mine for a while. The landlord soon protected me from the violence of the bad-meaning man, and drove him away from the house.

I was detained at Cleveland several days, not knowing how to get across the Lake into Canada. I went out to the shore of the lake again and again, to try and see the other side, but I could see no hill, mountain, nor city of the asylum I sought. I was afraid to inquire where it was, lest it would betray such a degree of ignorance as to excite suspicion at once. One day I heard a man ask another, employed on board a vessel, "and where does this vessel trade?" Well, I thought, if that is a proper question for you, it is for me. So I passed along and asked of every vessel, "Where does this vessel trade ?" At last the answer came, "over here in Kettle Creek, near Port Stanley." And where is that, said I. "O, right over here in Canada." That was the sound for me, "over here in Canada." The captain asked me if I wanted a passage to Canada. I thought it would not do to be too earnest about it, lest it would betray me. I told him I some thought of going, If I could get a passage cheap. We soon came to terms on this point, and that evening we set sail. After proceeding only nine miles the wind changed, and the captain returned to port again. This I thought was a very bad omen. However, I stuck by, and the next evening at nine o'clock we set sail once more, and at daylight, we were in Canada.

When I stepped ashore here, I said, sure enough I AM FREE. Good heaven! what a sensation, when it first visits the bosom of a full grown man--one, born to bondage--one, who had been taught from early infancy, that this was his inevitable lot for life. Not till then, did I dare to cherish

Page 39

for a moment the feeling that one of the limbs of my body, was my own. The slaves often say, when cut in the hand or foot, "plague on the old foot, or the old hand, it is master's--let him take care of it--Nigger don 't care if he never get well." My hands, my feet, were now my own. But what to do with them was the next question. A strange sky was over me, a new earth under me, strange voices all around--even the animals were such as I had never seen. A flock of prairie hens and some black geese, were entirely new to me. I was entirely alone, no human being that I had ever seen before, where I could speak to him or he to me.

And could I make that country ever seem like home?Some people are very much afraid all the slaves will run up North, if they are ever free. But I can assure them that they will run backagain if they do. If I could have been assured of my freedom in Kentucky then, I would have given any thing in the world for the prospect of spending my life among my old acquaintances, and where I first saw the sky, and the sun rise and go down. It was a long time before I could make the sun work right at all. It would rise in the wrong place, and go down wrong, and finally it behaved so bad, I thought it could not be the same sun.

There was a little something added to this feeling of strangeness. I could not forget all the horrid stories slaveholders tell about Canada. They assure the slave, that when they get hold of slaves in Canada, they make various uses of them. Sometimes they skin the head, and wear the wool on their coat collars--put them into the lead mines with both eyes out--the young slaves they eat--and as for the Red Coats, they are sure death to the slave. However ridiculous to a well informed person such stories

Page 40

may appear, they work powerfully upon the excited imagination of an ignorant slave. With these stories all fresh in mind, when I arrived at St. Thomas, I kept a bright look out for the Red Coats. As I was turning tile corner of one of the streets, sure enough, there stood before me a Red Coat in full uniform, with his tall bear-skin cap a foot and a half high, his gun shouldered, and he standing as erect as a guide-post. Sure enough, that is the fellow that they tell about catching the slave. I turned on my heel and sought another street. On turning another corner, the samesoldier, as I thought, faced me with his black cap and stern look. Sure enough, my time has come now. I was as near scared to death then, as a man can be and breathe. I could not have felt any worse, if he had shot me right through the heart. I made off again as soon as I dared to move. I inquired for a tavern. When I came up to it, there was a great brazen lion sleeping over the door, and although I knew it was not alive, I had been so well frightened, that I was almost afraid to go in. Hunger drove me to it at last, and I asked for something to eat.

On my way to St. Thomas I was also badly frightened. A man asked me who I was. I was afraid to tell him, a runaway slave, lest he should have me to the mines. I was afraid to say, "I am an American," lest he should shoot me, for I knew there had been trouble between the British and Americans. I inquired at length for the place where the greatest number of colored soldiers were. I was told there were a great many at New London; so for New London I started. I got a ride with some country people to the latter place. They asked me who I was, and I told them from Kentucky; and they, in a familiar

Page 41

way, called me "Old Kentuck." I saw some soldiers on the way, and asked the men what they had soldiers for. They said they were kept "to get drunk and be whipt;" that was the chief use they made of them. At last I reached New London, and here I found soldiers in great numbers. I attended at their parade, and saw the guard driving the people back ; but it required no guard to keep me off. I thought, if you will let me alone, I will not trouble you. I was as much afraid of a red coat, as I would have been of a bear. Here I asked again for the colored soldiers. The answer was, "Out at Chatham, about seventy miles distant." I started for Chatham. The first night I stopped at a place called the Indian Settlement. The door was barred at the house where I was, which I did not like so well, as I was yet somewhat afraid of their Canadian tricks. Just before I got to Chatham, I met two colored soldiers, with a white man bound, and driving him along before them. This was something quite new. I thought then, sure enough this is the land for me. I had seen a great many colored people bound, and in the hands of the whites, but this was changing things right about. This removed all my suspicions, and ever after I felt quite easy in Canada. I made diligent inquiry for several slaves that I had known in Kentucky, and at length found one named Henry. He told me of several others with whom I had been acquainted, and from him also I received the first correct information about brother Milton. I knew that he had left Kentucky about a year before I did, and I supposed, until now, that he was in Canada. Henry told me he was at Oberlin, Ohio.

At Chatham I hired myself for a while to recruit my purse a little, as it had become pretty well drained by this

Page 42

time. I had only about sixty-four dollars when I left Kentucky, and I had been living upon it now for about six weeks. Mr. Everett, with whom I worked, treated me kindly, and urged me to stay in Canada, offering me business on his farm. He declared "there was no 'free state" in America, all were slave states--bound to slavery, and the slave could have no asylum in any of them." There is certainly a great deal of truth in this remark. I have felt, wherever I may be in the United States, the kidnappers may be upon me at any moment. If I should creep up to the top of the monument on Bunker's Hill, beneath which my father fought, I should not be safe even there. The slave-mongers have a right, by the laws of the United States, to seek me even upon the top of the monument, whose base rests upon the bones of those who fought for freedom.

I soon after made my way to Sandwich, and crossed over to Detroit, on my way to Ohio, to see Milton. While in Canada I swapped away my pistol, as I thought I should not need it, for an old watch. When I arrived at Detroit, I found my watch was gone. I put my baggage, with nearly every cent of money I had, on board the boat for Cleveland, and went back to Sandwich to search for the old watch. The ferry here was about three-fourths of a mile, and in my zeal for the old watch, I wandered so far that I did not get back in season for the boat, and had the satisfaction of hearing her last bell just as I was about to leave the Canada shore. When I got back to Detroit I was in a fine fix; my money and my clothes gone, and I left to wander about in the streets of Detroit. A man may be a man for all clothes or money, but he don't feel quite so well, any how. What to do now I could hardly

Page 43

tell. It was about the first of November. I wandered about and picked up something very cheap for supper, and paid ninepence for lodging. All the next day no boat for Cleveland. Long days and nights to me. At length another boat was up for Cleveland. I went to the captain to tell him my story; he was very cross and savage--said a man no business from home me without money--that so many told stories about losing money that he did not know what to believe. He finally asked me how much money I had. I told him sixty-two and a half cents. Well, he said, give me that, and pay the balance when you get there. I gave him every cent I had. We were a day and a night on the passage, and I had nothing to eat except some cold potatoes, which I picked from a barrel of fragments, and cold victuals. I went to the steward, or cook, and asked for something to eat, but he told me his orders were strict to give away nothing, and if he should do it, he would lose his place at once.

When the boat came to Cleveland it was in the night, and I thought I would spend the balance of the night in the boat. The steward soon came along, and asked if I did not know that the boat had landed, and the passengers had gone ashore. I told him I knew it, but I had paid the captain all the money I had, and could get no shelter for the night unless I remained in the boat. He was very harsh and unfeeling, and drove me ashore, although it was very cold, and snow on the ground. I walked around awhile, till I saw a light in a small house of entertainment. I called for lodging. In the morning, the Frenchman, who kept it, wanted to know if I would have breakfast. I told him no. He said then I might pay for my lodging. I told him I would do so before I left, and that my outside coat might hang there till I paid him.

Page 44

I was obliged at once to start on an expedition for raising some cash. My resources were not very numerous. I took a hair brush that I had paid three York shillings for, a short time before, and sallied out to make a sale. But the wants of every person I met seemed to be in the same direction with my own; they wanted money more than hair brushes. At last I found a customer who paid me ninepence cash, and a small balance in the shape of something to eat for breakfast. I was started square for that day, and delivered out of my present distress. But hunger will return, and all the quicker when a man don't know how to satisfy it when it does come. I went to a plain boarding house, and told the man just my situation, that I was waiting for the boat to return from Buffalo, hoping to get my baggage and money. He said he would board me two or three days and risk it. I tried to get work, but no one seemed inclined to employ me. At last I gave up in despair, about my luggage, and concluded to start as soon as possible for Oberlin. I sold my great coat for two dollars, paid one for my board, and with the other I was going to pay my fare to Oberlin. That night, after I had made all my arrangements to leave in the morning, the boat came. On hearing the bell of a steam boat, in the night, I jumped up and went to the wharf, and found my baggage; paid a quarter of a dollar for the long journey it had been carried, and glad enough to get it again at that.

The next morning I took the stage for Oberlin; found several abolitionists from that place in the coach. They mentioned a slave named Milton Clarke, who was living there, that he had a brother in Canada, and that he expected him there soon. They spoke in a very friendly manner of Milton, and of the slaves; so after we had had a long

Page 45

conversation, and I perceived they were all friendly, I made myself known to them. To be thus surrounded at once with friends, in a land of strangers, was something quite new to me. The impression made by the kindness of these strangers upon my heart, will never be effaced. I thought there must be some new principle at work here, such as I had not seen much of in Kentucky. That evening I arrived at Oberlin, and found Milton boarding at a Mrs. Cole's. Finding here so many friends, my first impression was that all the abolitionists in the country must live right there together. When Milton spoke of going to Massachusetts, "No" said I, "we better stay here where the abolitionists live." And when they assured me that the friends of the slave were more numerous in Massachusetts than in Ohio, I was greatly surprised.

Milton and I had not seen each other for a year; during that time we had passed through the greatest change in outward condition, that can befal a man in this world. How glad we were to greet each other in what we then thought a free State, may be easily imagined. We little dreamed of the dangers sleeping around us. Brother Milton had not encountered so much danger in getting away as I had. But his time for suffering was soon to come. For several years before his escape, Milton had hired his time of his master, and had been employed as a steward in different steam boats upon the river. He had paid as high as two hundred dollars a year for his time. From his master he bad a written pass, permitting him to go up and down the Mississippi and Ohio rivers when he pleased. He found it easy therefore to land on the north side of the Ohio river, and concluded to take his own time for returning. He had caused a letter to be written to Mr. L., his pretended

Page 46

owner, telling him to give himself no anxiety on his account; that he had found by experience he had wit enough to take care of himself, and he thought the care of his master was not worth the two hundred dollars a year which he had been paying for it for four years; that on the whole, if his master would be quiet and contented, he thought he should do very well. This letter, the escape of two persons belonging to the same family, and from the same region, in one year, waked up the fears and the spite of the slave holders. However, they let us have a little respite, and through the following winter and spring, we were employed in various kinds of work at Oberlin and in the neighborhood.

All this time I was deliberating upon a plan by which to go down and rescue Cyrus, our youngest brother, from bondage. In July 1842, I gathered what little money I had saved, which was not a large sum, and started for Kentucky again. As near as I remember I had about twenty dollars. I did not tell my plan to but one or two at Oberlin, because there were many slaves there, and I did not know but that it might get to Kentucky in some way through them sooner than I should. On my way down through Ohio, I advised with several well known friends of the slave. Most of them pointed out the dangers I should encounter, and urged me not to go. One young man told me to go, and the God of heaven would prosper me. I knew it was dangerous, but I did not then dream of all that I must suffer in body and mind before I was through with it. It is not a very comfortable feeling to be creeping round day and night for nearly two weeks together in a den of lions, where if one of them happens to put his paw on you, it is certain death, or something much worse.

Page 47

At Ripley, I met a man who had lived in Kentucky; he encouraged me to go forward, and directed me about the roads. He told me to keep on a back route not much traveled and I should not be likely to be molested. I crossed the river at Ripley, and when I reached the other side, and was again upon the soil on which I had suffered so much, I trembled, shuddered, at the thoughts of what might happen to me. My fears, my feelings overcame for the moment all my resolution, and I was for a time completely overcome with emotion. Tears flowed like a brook of water. I had just left kind friends; I was now where every man I met would be my enemy. It was a long time before I could summon courage sufficient to proceed. I had with me a rude map made by the Kentuckian whom I saw at Ripley. After examining this as well as I could, I proceeded. In the afternoon of the first day, as I was sitting in a stream to bathe and cool my feet, a man rode up on horseback, and entered into a long conversation with me. He asked me Some questions about my travelling, but none but what I could easily answer. He pointed out to me a house where a white woman lived, who he said had recently suffered terribly from a fright. Eight slaves, that were running away, called for something to eat, and the poor woman was sorely scared by them. For his part, the man said, he hoped they never would find the slaves again. Slavery was the curse of Kentucky. He had been brought up to work and he liked to work, but slavery made it disgraceful for any white man to work .From this conversation I was almost a good mind to trust this man, and tell him my story, but on second thought, I concluded it might be just as safe not to do it. A hundred or two dollars for returning a slave, for a poor man, is a heavy temptation. At night

Page 48

I stopped at the house of a widow woman,--not a tavern exactly, but they often entertained people there. The next day when I got as far as Cynthiana, within about twenty miles of Lexington, I was sore all over and lame from having walked so far. I tried to hire a horse and carriage to help me a few miles. At last I agreed with a man to send me forward to a certain place, which he said was twelve miles, and for which I paid him, in advance, three dollars. It proved to be only seven miles. This was now Sabbath day, as I had selected that as the most suitable day for making my entrance into Lexington. There is much more passing in and out on that day, and I thought I should be much less observed than on any other day.

When I approached the city and met troops of idlers on foot and on horseback, sauntering out of the city, I was very careful to keep my umbrella before my face, as people passed, and kept my eyes right before me. There were many persons in the place, who had known me, and I did not care to be recognized by any of them. Just before entering the city, I turned off to the field, and laid down under a tree and waited for night. When its curtains were fairly over me, I started up, took two pocket handkerchiefs, tied one over my forehead, the other under my chin, and marched forward for the city. It was not then so dark as I wished it was. I met a young slave driving cows. He was quite disposed to condole with me, and said, in a very sympathetic manner, "Massa sick." "Yes, boy," I said, "Massa sick,--drive along your cows." The next colored man I met, I knew him in a moment, but he did not recognize me. I made for the wash-house of the man with whom Cyrus lived. I reached it without attracting any notice, and found there an old slave as true as steel. I

Page 49

inquired for Cyrus, he said he was at home. He very soon recollected me; and while the boy was gone to call Cyrus, he uttered a great many exclamations of wonder to think I should return.