Slave Life in Virginia and

Kentucky;

or, Fifty Years of Slavery in

the Southern States of America:

Electronic Edition.

Fedric, Francis

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Sarah Reuning

Images scanned by

Chris Hill

Text encoded by

Chris Hill and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 200K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Call number (T) E444 .F29 (Treasure Room Collection, James E. Shepard Library, North Carolina Central University)

The electronic edition

is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American

South.

All footnotes are

moved to the end of paragraphs in which the reference occurs.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as

--

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

- LC Subject Headings:

- Fedric, Francis.

- African Americans -- Virginia -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Kentucky -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Virginia -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Kentucky -- Biography.

- Fugitive slaves -- Virginia -- Biography.

- Fugitive slaves -- Kentucky -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Virginia -- Social conditions.

- Slaves -- Kentucky -- Social conditions.

- Slavery -- Virginia -- History -- 19th century.

- Slavery -- Kentucky -- History -- 19th century.

- Plantation life -- Virginia -- History -- 19th century.

- Plantation life -- Virginia -- History -- 19th century.

- Slaves' writings, American -- Virginia.

- Slaves' writings, American -- Kentucky.

- 2000-03-28,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-09-13,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-08-29,

Chris Hill

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-08-09,

Sarah Reuning

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

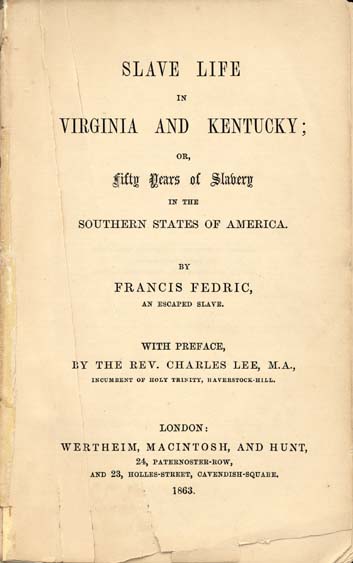

SLAVE LIFE

IN

VIRGINIA AND KENTUCKY;

OR,

Fifty Years of Slavery

IN THE

SOUTHERN STATES OF AMERICA.

BY

FRANCIS FEDRIC,

AN ESCAPED SLAVE.

WITH PREFACE,

BY THE REV. CHARLES LEE, M. A.,

INCUMBENT OF HOLY TRINITY, HAVERSTOCK-HILL.

LONDON:

WERTHEIM, MACINTOSH, AND HUNT,

24, PATERNOSTER-ROW,

AND 23, HOLLES-STREET, CAVENDISH-SQUARE.

1863

Page verso

LONDON:

WERTHEIM, MACINTOSH, AND HUNT,

24, PATERNOSTER-ROW,

AND 23, HOLLES-STREET, CAVENDISH-SQUARE.

Page iii

PREFACE.

THE Memoir contained in the following pages may, I believe, be thoroughly relied on as both genuine and authentic. The Author, Francis Fedric, came to me well recommended; and, since he has been in London, has been continually under my notice. I have every reason to regard him (as his many friends represent him) as an honest man, and a good Christian. His testimonials are signed, amongst others, by the well-known names of Dr. Guthrie, Dr. Alexander, and Dr. Johnston, of Edinburgh; by Samuel Gurney, Esq., of London; and by the Revs. C. J. Goodhart and Gerald Blunt, of Chelsea. His references also to ministers of religion, and others, by whom he was employed in Toronto, to look after escaped slaves, are completely satisfactory.

The narrative itself will sufficiently disclose the

Page iv

sad tale of bondage and brutality, to which, for fifty years of his life, poor Fedric was an unfortunate victim. Escaped from slavery, and finding his way to our own country, the encouragement and assistance of sympathizing friends enabled him to establish a lodging-house in Manchester. That blight of slavery, however, which had fallen so heavily on his previous life, still seemed to pursue him--originating the war between the North and the South (whether directly or indirectly need not now be discussed). This was immediately followed by the Manchester distress, and Fedric at once lost the scanty subsistence he had relied on. Being paralyzed in his hands by exposure in the swamps, he is altogether unable to follow handiwork of any kind. He is, however, a very effective lecturer, and is fully capable of riveting the attention of an audience by the romantic details of his very interesting life. To help him a little to thus obtaining a livelihood, and hoping that, before long, by the aid of whatever funds he may realize, he will be able to re-establish himself in some kind of business, I have induced a gentleman of this neighbourhood to take down from his lips the memoir now given to the public. It presents no one-sided view of slavery;

Page v

but the sunny side (if bondage has any bright side), as well as its darker and more hateful tints, are all fairly and truthfully depicted. When we think of quadroons, and the detestable secrets with which their career is shockingly and shamefully associated--when we think of the enforced separation of the poor slave from his wife, and of children from their parents, notwithstanding all that can possibly be said of kind and humane masters--when we add the liability of being sold at any time into the hands of some hard-hearted man, it is impossible not to shudder at so accursed a system, and to pray God, in His own good time, and best way, to smite off every fetter and set the captives free.

CHARLES LEE, M.A.,

Incumbent of Holy Trinity, Haverstock-hill.

Feb. 16, 1863.

Page vii

CONTENTS.

- CHAPTER 1.

Birth-place--Earliest Recollections--Slave Girl Flogged --Fear of a Slaveholder during a Thunderstorm-- Father and Mother--Piety of Grandmother, a Native African--Systematic Degradation of Slave Children--Grandmother the first Person I saw Flogged--Feeding of Slaves--Grandmother's Happy Death--Cunning of Slaves . . . . . 1 - CHAPTER II.

Scene on Leaving Virginia for Kentucky--Cross the Alleghany Mountains--Arrive at my Master's New Plantation in Mason County--Become a House Slave--Difficulties of Training me--A Burglar Encountered--Social Affections of Slaves--A Sunday at Chapel--Christmas, how spent by the Slaves--Slave Patrols--Brutalizing Effect of Slavery upon the Ladies-- Consequences to the Slaves of Resisting Tyranny . . . . . 14 - CHAPTER III.

Negroes' Wedding--Vanity Exposed--Love of Long Words--Death of my old Master--Cruelly treated by my dissipated young Master--Slaves sold to pay my Master's Gambling Debts-- Slaveholder's own Children sold to Infamy . . . . . 32 - CHAPTER VI.

Corn Songs in Harvest-time--Conversion . . . . . 47

Page viii - CHAPTER V.

Superstition of the Slaveholders--Slaves' Party-- Reckoning-up the White Folks . . . . . 56 - CHAPTER VI.

Labour of any kind Despised--Slaves the Badge of Distinction among White Folks--Impudence of the Ladies . . . . . 73 - CHAPTER VII.

First Attempt to Escape--Pursued by Bloodhounds-- Reach Bear's Wallow, a dismal Swamp--Conceal myself in a Cavern--Driven by Hunger, give myself up to my Master--Receive 107 lashes--Brutally treated afterwards by my Master . . . . . 75 - CHAPTER VIII.

Produce of Kentucky--Climate of Kentucky--How the Kentuckians spend the Winter--Fevers rage in Summer--Slaveholders frequently administer Medicine to Slaves--Anecdote--The Domestic Animals --The Birds--Change of Property, how it affects the Slaves--Resignation of a Female Slave . . . . . 87 - CHAPTER IX.

Cruelty to Slaves concealed from Strangers--Slaveholders traduce the English--Slaves' opinions of the English--Slaves always anxious to be Free . . . . . 98 - CHAPTER X.

An Abolitionist Planter contrives my Escape--My Escape by the "Underground Railway"--Land in Canada--Employed by the Anti-Slavery Society-- Marry--Arrive in England--Conclusion . . . . . 101

Page 1

SLAVE LIFE IN VIRGINIA AND KENTUCKY.

CHAPTER I.

Birth-place--Earliest Recollections--Slave Girl Flogged --Fear of a Slaveholder during a Thunderstorm-- Father and Mother--Piety of Grandmother, a Native African--Systematic Degradation of Slave Children--Grandmother the first Person I saw Flogged--Feeding of Slaves--Grandmother's Happy Death--Cunning of Slaves.

I WAS born in Fauquier County, in Old Virginia. My remembrance, as nearly as I can reckon, extends back to my eighth or ninth year of age. Some little striking incidents occur, now and then to my mind, which happened when I was somewhat younger even than that. My master's house, a frame one, as it is called in America, was situated on a gently rising ground, skirted by a small stream, emptying itself into a deep rivulet, named the Cedar Run. This rivulet was from twenty to

Page 2

thirty yards wide, and during the rainy season dashed along at a headlong pace, carrying with it trees and logs, and overflowing very often large tracts of the surrounding country, which was mostly of a level character. But although near so fine a body of water, unlike most slaves, I never learned to swim, which deficiency, as you will find in the sequel, was one of the greatest misfortunes of my life. Almost the first circumstance which I recollect is this. A Mrs. R----, the wife of a Colonel R----, who had a large plantation near to my master's, possessing four or five hundred slaves, thinking she did not receive as many eggs as she ought to do from the girl who collected them, asked a negro whether she ought to receive an egg from each hen a-day. "It would be a very good hen to lay an egg every day," replied the negro. Mistaking the meaning of the answer, and imagining that she had been cheated, she gave the poor girl a flogging every time she failed to bring the required number, notwithstanding all her protestations of innocence, and frantic entreaties not to be whipped. At last a lady residing near, told Mrs. R---- that it was absurd to expect anything of the kind. Colonel R---- one day sent his servant-man to bring some groceries from the stores; when he returned with the groceries, the Colonel said, "Why did you bring me such inferior sugar as this?" The slave replied that it was the same kind as he always had. The Colonel said it could not be so, as the price

Page 3

was too low, adding, "go and tell Mr. V. at the stores to send me some better at once." The slave went with the message; Mr. V. smiled, and doubled the price on a new bill, and sent the same sugar back. The Colonel looked first at the bill, and then at the sugar. "Aye, this is something like; this is as it ought to be," he said. I merely relate this anecdote to show what kind of persons the slave-owners, in some instances, are, and that the slaves are not always kept in subjection by a consciousness of their master's intellectual superiority, for the slaves often, behind their backs, laugh at their absurdities; but by a brutal system of terrorism practised upon them from their very birth.

A circumstance of a different nature is the next I can call to mind. The weather was warm and sultry, scarcely a breath of air stirred, and clouds of an inky blackness began to rise from the distant uplands. Colonel R---- had just returned from his tobacco-fields; the rain began to fall in large drops. "Bring in the niggers!" shouted Colonel R----. Some fifteen or twenty soon entered his sitting-room, and were arranged around the Colonel, who sat on a chair in the centre of the room. A distant thunder-clap was heard. "Come nearer," he cried "stand close to me." And there sat this master of 500 niggers, cowering and trembling during the whole of the thunderstorm. I was told that this was his invariable custom whenever it thundered or lightened,

Page 4

imagining that the Almighty would not strike the slaves, consequently, being surrounded by them, the Colonel thought he should certainly escape. We slaves often talked together about this cowardice of Colonel R----'s, and attributed it to his fear of God, on account of his sins, although he was not a man remarkable for cruelty. But there is, even in the minds of those most accustomed to slavery, and born and brought up amongst it, a secret misgiving that all is not right; although, when no danger is near at hand, they will not only defend it, but eulogize it and expatiate upon its advantages, even to the negro himself. My mother told me that the Colonel thought the negroes could drive the lightning away. However, whether his conduct arose from this absurd notion or fear, it only proves the weak character of this tyrant over the souls and bodies of men. My father and mother were slaves, and worked for different masters. My mother had nine children, two boys and seven girls. The children are always the property of the mother's master.

Piety of Grandmother, a Native African.

My grandfather and grandmother were stolen from Africa and brought to Maryland, and taken from thence to Virginia. My grandmother was taught by her young mistress to repeat the Prayers and Liturgy of the Protestant Church. My grandmother

Page 5

could not read, yet in spite of every disadvantage, she was very anxious about religion, and always eager to impart any religious knowledge she might have acquired to her children and grandchildren, or, in fact, to any one about her.

Systematic Degradation of Slave Children.

My grandmother showed she was actuated on every occasion by truly Christian principles. She wished very much to teach me the Prayers and Liturgy which she had learnt.

But the conduct of my master caused great perplexity to me, and made me indifferent about any such thing. My master was in the habit of sending for all the slave children from the cabins, then standing on the verandah, he would say, "Look! Do you see those horses?" "Yes, Sir," all replied together. "Do you see the cows?" "Yes, Sir." "Do you see the sheep?" "Yes, Sir." "Do you see the mules?" "Yes, Sir." "Look, you niggers! you have no souls, you are just like those cattle, when you die there is an end of you; there is nothing more for you to think about than living. White people only have souls." My mother, when I was a boy, had no notion of what religion is, and to my good grandmother alone I am indebted for any instruction I at this time received. She was ever, as I have said before, anxious to acquire religious knowledge and to attend prayer-meetings as often as she possibly could; for doing so on one

Page 6

occasion, I witnessed the first flogging I ever saw in my life. But before I describe the flogging, I will explain about the overseers. Many masters possessing large plantations, and some hundreds of slaves, being desirous to divest themselves as much as possible of the cares of managing the estate, hire white men, at a salary of from 1,200 to 1,400 dollars per annum, to look after the whole property. These are the best and most humane overseers. But other slave proprietors, in order to save the cost of an overseer, but chiefly to exact as much work as possible out of the niggers, make a nigger an overseer, who if he does not cruelly work the slaves is threatened with a flogging, which the master cannot give to a white man. In order to save his own back the slave overseer very often behaves in the most brutal manner to the niggers under him. My grandmother's master was one of the hard kind. He had made her son an overseer.

My Grandmother Flogged.

Consequently, my grandmother having committed the crime of attending a prayer-meeting, was ordered to be flogged by her own son. This was done by tying her hands before her with a rope, and then fastening the rope to a peach tree, and laying bare the back. Her own son was then made to give her forty lashes with a thong of a raw cow's-hide, her master standing over her the whole time blaspheming

Page 7

and threatening what he would do if her son did not lay it on.

My master had about 100 slaves, engaged chiefly in the cultivation of tobacco, this and wheat being the staple produce of Virginia at that time. The slaves had to work very hard in digging the ground with what is termed a grub hoe. The slaves leave their huts quite early in the morning, and work until late at night, especially in the spring and fall. I have known them very often, when my master has been away drinking, work all night long, husking Indian corn to put into cribs.

Feeding of Slaves.

Slaves every Monday morning have a certain quantity of Indian corn handed out to them; this they grind with a handmill, and boil or use the meal as they like. The adult slaves have one salt herring allowed for breakfast, during the winter time. The breakfast hour is usually from ten to eleven o'clock. The dinner consists generally of black-eyed peas soup, as it is called. About a quart of peas is boiled in a large pan, and a small piece of meat, just to flavour the soup, is put into the pan. The next day it would be bean soup, and another day it would be Indian meal broth. The dinner hour is about two or three o'clock; the soup being served out to the men and women in bowls; but the children feed like pigs out of troughs,

Page 8

and being supplied sparingly, invariably fight and quarrel with one another over their meals. I remember when a boy I did not care how I was fed, all I was anxious about was to get sufficient. This mode of living is no doubt adopted for the express purpose of brutalizing the slaves as much as possible, and making the utmost difference between them and the white man. Slaves live in huts made of logs of wood covered with wood, the men and women sleeping indiscriminately together in the same room. But English people would be perfectly surprised to see the natural modesty and delicacy of the women thus huddled together; every possible effort being exerted, under such circumstances, to preserve appearances--an unchaste female slave being very rarely found.

As a lad, hearty, and only poorly fed, I was always delighted, if I could get any extra food; and my memory seems to be very tenacious of anything having reference to eating. I remember my mother baking some short cake, and giving a piece to me, and a piece to my cousin, who was a lad of my own age--eight or nine. I quickly dispatched mine; but my cousin danced about before me, with his piece, tantalizingly crying out, "I've got bread, and you've got none! I've got bread, and you've got none!" as rapidly as he could. I snatched the piece out of his hand, and ran away from him, and soon had a portion in my mouth. He threw himself down, and shouted, "I'm dead! I'm dead!

Page 9

I'm dead!" rolling, kicking, and screaming, as rapidly as he could, for full ten or fifteen minutes. His mother gave me a good beating that night. I felt very proud, however, and bragged about what I had done, for some days; but I made a great mistake soon after, which took me down a peg. I was wrestling with one of the children, and threw him, and hurt him, which displeased my grandmother, who said I should get a flogging. I made haste in the evening to get into the straw, and to cover myself with an old rug for the night. I began to snore away, as hard as I could, as if fast asleep; thinking they would not wake me to whip me. When my uncle came in, my grandmother said, she had promised me a good flogging, and she would be as good as her word. My uncle said, "Where is he? I'll give it to him." One of the women said, "There he is, in his bed, asleep." I snored louder and faster. Another woman said, "He is not asleep." "But he is asleep." "He isn't asleep." "But, me tell you, he be asleep." Thus the women disputed. I thought I would help myself a little, and said, "Yes, I be asleep!" I forgot. But my uncle did not forget to take me out of the straw, and to flog me well.

My good grandmother's figure and general appearance will always be indelibly impressed upon my mind. She was above the middle height in England, and had short black hair, inclined to curl, but very sparse upon the head.

Page 10

My grandfather was about six feet in height, a well-proportioned, muscular man; his hair was longer than my grandmother's, and very thick upon the head: from his appearance, I should suppose he was not of the same tribe in Africa as my grandmother.

Grandmother's happy Death.

I never knew any woman so religious as my grandmother; in all her oppressions and trials, her heart was full of the love of God. In looking back now, after so many years, I am filled with admiration of her conduct. When any troubles had come to her, or when she had been whipped, she would speak of her home, far away beyond the clouds, where there would be no whipping, and she would be at rest. This seemed to be her greatest, indeed her sole comfort, in the hour of trial. This would be a source of joy, when seated, on a Sabbath evening, under the shade of the peach trees, she talked to her fellow-slaves, or to those who came from the neighbouring plantations to see her. I was standing by, one Sunday, and heard a woman say to her, "Selling is worse than flogging. My husband was sold six years ago. My heart has bled ever since, and is not well yet. I have been flogged many times, since he was torn from me, but my back has healed in time."

Page 11

My grandfather never was a professing Christian; his greatest stumbling-block was the conduct of the slaveholders, in buying and selling slaves, and then going, after doing so, and perhaps partaking of the Sacrament. "How," he would say, "can Jesus be just, if He will allow such oppression and wrong? Don't the slaveholders justify their conduct by the Bible itself, and say, that it tells them to do so? How can God be just, when He not only permits, but sanctions, such conduct?" My grandmother would reason with him, and endeavour to show him that the slaveholders, at the Last Day, would have to account for their actions, and that we slaves should look to our own conduct. However, no real, abiding change, such as had been produced upon my grandmother, ever was effected upon him.

As the closing scenes of life approached, my grandmother's faith became stronger and stronger. She looked forward to the future, when all would be set right; and delighted to talk about heaven, and to ask those about her to be good, that they might all meet together in the next world. Her illness was short; and ladies came to her bedside, for her good life was a subject of conversation even among them; and many a truthful lesson did they learn from her. She bore everything with Christian fortitude; her sons and daughters stood around her deathbed, receiving her blessing, or listening to her good advice. I was not present when she

Page 12

died, but my mother said, she died gently and happily, as if her last hours were a foretaste of what was in store for her.

A badge of aristocracy among slaveholders is the number of slaves they hold, and white people of equal fortune are not generally allowed to visit slaveholders, who look down upon them with a species of contempt. One remarkable fact which I wish to impress upon my readers is this, that the white men born in those districts in America where slaves are held, are just as capable of bearing the heat as the black men. And the proof is this, that in the harvest-time, when the two are working together in the fields, the white men can actually beat the negroes at the work, and very often the black man has to give up, and is laughed at by the white labourer. They say, "Only give us sufficient wages, and we will work by the side of any nigger alive." It is quite shocking to hear slaveholders distorting even the Bible itself to prove that a negro alone was made for hard work.

Cunning of Slaves.

I remember a slave, who was not treated very well with respect to food and other things, when he had done his work being lectured by his mistress on the duties of a slave, she telling him that in proportion to his obedience and servility as a slave he would be loved by God. One day, on receiving

Page 13

the Bible from his mistress, he began as follows,-- "Give your slaves plenty of bread and meat, and plenty of hot biscuit in a morning, also be sure and give him three horns of whiskey a-day." "Come, come, stop that, Bob," his mistress cried; "none of your nonsense, Bob, there is nothing of that kind there." Bob, throwing down the book, said, "There, there, take it yourself, read it; you says a great deal more than you'll find there." Slaves are all of them full of this sly, artful, indirect way of conveying what they dare not speak out, and their humour is very often the medium of hinting wholesome truths. Is not cunning always the natural consequence of tyranny? One of my master's neighbours had lost two pigs. The overseer was ordered to search the cottages to try to find any portions of the missing pigs. An old woman, who had one of the pigs, seeing the overseer coming to search, and having heard that the person who had stolen them was to receive 200 lashes when discovered, threw the pork, blood and all, into a tub of persimum, which is a kind of beer in America. The overseer, having searched diligently all the nooks and corners of the cabin, even having opened the bed, said, "Well, Molly, I am very glad to find that you have not got the pigs. Now draw me some beer." Molly, with trembling hand, drew a bowl of it. "Why does your hand tremble, Molly?" said the overseer. "Because," said Molly, "old woman has been sick all night."

Page 14

"Very good, this beer," said the overseer; "draw me another." Molly now was frightened that the blood would betray her. She drew another bowl. "This is the very best beer I ever in my life tasted," said the overseer; "here is a shilling for you. I shall be sure and tell your master, Molly, that you have not got the pigs."

CHAPTER II.

Scene on Leaving Virginia for Kentucky--Cross the Alleghany Mountains--Arrive at my Master's New Plantation in Mason County--Become a House Slave--Difficulties of Training me--A Burglar Encountered--Social Affections of Slaves--A Sunday at Chapel--Christmas, how spent by the Slaves--Slave Patrols--Brutalizing Effect of Slavery upon the Ladies-- Consequences to the Slaves of Resisting Tyranny.

I HAD arrived at about my fourteenth year of age, without having been engaged in any definite employment,--running errands, tending the corn-fields, looking after the cattle, in short, doing anything and everything in turns about the plantation. My master had determined to give up his plantation in Virginia, and to go to another in Kentucky. I shall never forget the heart-rending scenes which I witnessed before we started. Men and women

Page 15

down on their knees begging to be purchased to go with their wives or husbands, who worked for my master, children crying and imploring not to have their parents sent away from them; but all their beseeching and tears were of no avail. They were ruthlessly separated, most of them for ever. Still, after so many years, their wailings and lamentations and piercing cries sound in my ears whenever I think of Virginia.

Cross the Alleghany Mountains.

We had to pass over the Alleghany mountains to Wieland, in New Virginia. Wieland lies on the banks of the Ohio. We set out with several waggons and a sorrowful cavalcade on our way to Kentucky. After several days' journey, we saw at a distance the lofty range of the Alleghany mountains. My master, by the use of his glass, had told us two or three days before that the mountains were near. They now became visible, looming in the distance something like blue sky. After a while we approached them, and began to pass over them through what appeared to be a long, winding valley. On every side, huge, blue-looking rocks seemed impending. I thought, if let loose, they would fall upon us and crush us. Our journey was, I may say, almost interrupted every now and then, by immense droves of pigs, which are bred in Kentucky, and were proceeding from thence to Baltimore,

Page 16

and other places in Virginia. These droves contained very often 700 or 800 pigs. When we halted for the night we lit our fires, and baked our Indian meal on griddles; sometimes the cakes were very much burnt, but these, together with salt herrings, were the only food we had. Our drink was water from the surrounding rills running down the mountain-sides. In fact, torrents of water, arising from the ice and melting snow, were rushing down in hundreds of directions. The scenery was what I may term hard and wild, the tops of the mountains being hid by the clouds, in many places rolling far beneath. But my thoughts in passing over these mountains then were rather those of amazement and wonder than those of a curious and inquiring mind, such as now, with some enlightenment, I might have. I only remember large flights of crows, and what are called in America, black birds, which make a loud screaming noise, instead of a beautiful note, like the English bird of this name.

Two or three times during the night, when we were encamped and fast asleep, one of the overseers would call our names over, every one being obliged to wake up and answer. My master was afraid of some of us escaping, so uncertain are the owners of the possession of their Slaves. The masters are ever feverishly anxious about the slaves running away, and this being always continued, necessarily produces an irritability characteristic of the slave-holder.

Page 17

The howling of the wolves, and other wild animals, broke the solemn stillness which reigned widely around us. Now and then my master would fire his gun to frighten them away from us, but we never were in any way molested. Perhaps the fires kept them at a distance from us.

Arrive at my Master's new Plantation in Mason County.

From Welland we took boats to Maysville, Kentucky. My master had bought a farm in Mason County, about twenty miles from Maysville. When we arrived there we found a great deal of uncultivated land belonging to the farm. The first thing the negroes did was to clear the land of bush, and then to sow blue grass seed for the cattle to feed upon. They then fenced in the woods for what is called woodland pasture. The neighbouring planters came and showed my master how to manage his new estate. They told the slaves how to tap the sugar-tree to let the liquid out, and to boil it down so as to get the sugar from it. The slaves built a great many log-huts; for my master, at the next slave-market, intended to purchase more slaves.

Become a House-slave.

I was taken into the house to learn to wait at table--a fortunate chance for me, since I had a

Page 18

better opportunity of getting food. I shall never forget my first day in the kitchen. I was delighted to see some bread in the pantry. I took piece after piece to skim the fat from the top of the boiling-pot, overjoyed that I could have sufficient.

Difficulties of Training me.

My mistress took a fancy to me, and began to teach me some English words and phrases, for I only knew how to say "dis" and "dat," "den" and "dere," and a few such monosyllables. It is a saying among the masters, the bigger fool the better nigger. Hence all knowledge, except what pertains to work, is systematically kept from the field-slaves. My mistress made me stand before her to learn from her how I was to take a message. "Now, Francis," she said, "I want to make you quite a ladies' man. You must always be very polite to the ladies. You must say, 'I will go and tell the ladies.'" I repeated some hundreds of times, "I will go and tell the ladies." After some days' training, she thought she had made me sufficiently perfect to deliver a message. "Francis!" "Yes, marm," I said. "Go and tell Mrs.---- that I shall feel obliged by her calling upon me at half-past twelve o'clock to-morrow." "Yes, marm," I said; and she made me repeat the message some dozens of times. When perfect, as she thought, away I went, repeating all the way, "Missis will

Page 19

feel obliged by your calling upon her at half-past twelve; Missis will," &c., until I met a gentleman on the road who had seen and heard me repeating the words over and over again before I saw him. He called out, "Whom are you talking to?" I jumped, and every word jumped out of me, for I forgot it all. I ran back to my mistress and told her I had forgotten it, but did not tell her the reason why. "Just as I thought," she said. The teaching re-commenced, and, after some scores of repetitions of the message, I started again, determined that no one should hear me. I went whispering the words all the way as fast as ever I could, hastened into the lady's house, and hurriedly said the words over two or three times to the lady, and then ran back. Upon one occasion my mistress's sister said that she wanted me to do some washing, and gave me a dress to wash. I picked it up, and put it on the wash-board, and immediately tore it on purpose. She had left the room to fetch some thing for me to wash it with, and, returning in a minute, "Francis," she said, "I hope you have not begun to wash that dress yet?" "Oh, yes, missis, I have," I answered, holding up the torn dress at the same time. "You blockhead!" she said, "I shall never be able to teach you anything; I can never drive anything into your thick skull. I have a good mind to take a stick and kill you, you worthless good-for-nothing." But I was sufficiently cunning by this stratagem to escape what appeared

Page 20

to me the degrading womanly occupation of washing. In the same way I acted when she attempted to teach me to milk the cow. By no possible ingenuity could she, as she thought, make me learn the right side of the cow to milk upon; consequently, the cow invariably kicked when I was on the wrong side, and upset the milk-pail. I saw one day some cotton drying by the fire; I thought I would try whether I could make it blaze, thinking, if it did, I could easily put it out. I lit a stick, and set the cotton on fire. Every one in and about the house rushed to the kitchen to extinguish the flame; after some time they succeeded. I told my mistress that a spark had fallen upon it and made it blaze. This story seemed to satisfy her at the time. Some weeks afterwards my mistress called me into her room, and gave me some treacle and bread, and asked me if it was sweet. "Yers, missis," I said. "We are very good friends now, are we not?" "Yers, missis." She gave me two more pieces. "Now, Francis," she said, "don't friends always tell one another the truth?" "Yers, missis." "Don't friends tell each other every thought?" "Yers, missis." "Now, Francis," she added, fixing her eyes fully upon mine, "did you not set fire to the cotton?" "Ye-ye-yers, missis," I replied. "Now you shall have a good whipping for your lies and for setting fire to the cotton," she said; and sure enough I was flogged right soundly.

My mistress's sister was writing a letter one

Page 21

morning; I looked over her shoulder, and thought what pretty marks she was making. Having half finished one line, she put her pen down and left the room to take her breakfast. I took the pen up, and completed the line with crooks, and commenced another line, and ended just under the part where she had left off. I was examining what I had done, thinking it looked better and more distinct than her's, when in darted my mistress's sister, and began to beat me most unmercifully. "What has he done? what has he done?" cried my uncle, who was cook, and utterly at a loss to know what I had been doing. "The young rascal has been spoiling my writing," she said, laying on all the time, until my back was severely cut. I thought at the time it was cruel. A day or two afterwards my mistress took me into her room and talked to me kindly; she said it was wicked to do such things as those for which I had been flogged. I was surprised at a good deal of what she said, for I did not understand exactly in what the wrong consisted.

I merely mention these three or four little incidents to show how grossly ignorant I was, and that what is known to a child mixing in civilized society is a complete mystery and puzzle even to men working in the fields in a state of slavery. It was found utterly impossible to get on with me in the house unless I was instructed in something. But the most debasing ignorance is systematically kept up amongst the outdoor hands,

Page 22

any one manifesting superior intelligence being weeded out of the working gang, lest he should spoil the other slaves. My mistress was anxious to teach me to pick some wool. "You must pick it very quickly," she said. "Your master's brother will watch you, and tell me if you don't." She placed me in a room where my master's brother's portrait hung on the wall. "There he is," she said, "looking at you. Now, mind, you must pick away as fast as you can. Don't stop, or he will come and tell me." I thought it was my master's brother, and worked as hard as I could until I became very thirsty. I stopped, and looked anxiously at him, went up to him, and, putting my hand to my head, "Please, massa," I said, "may I go and get a drink?" He did not answer. This occurred for several days, until at last I thought I never saw a man who did not wink. I went slowly and cautiously up to the picture, and, after some hesitation, I felt it and turned it over, looked at the back, and, whilst thus engaged, in came my mistress. "What are you doing there," she said, "I will teach you to mind your work;" and she took the horsewhip and gave me a good flogging. She was no doubt annoyed that I had found out she was fooling me. When working within sight of the picture afterwards, I would say, "I's not going to work. You don't know nothing. They don't give us nothing. I's not going to work for nothing." And I did not half

Page 23

work, only just doing a little. A remarkable incident occurred soon after I was in our new house, and it evidently had a great deal to do with making me a favourite amongst them.

A Burglar Encountered.

I was sleeping one night, when my master was from home, on a mat near the foot of my mistress's bed. She called out to me, "Francis, Francis! get up! get up! come here! look!" pointing out of the window, "there is some one trying to break into the house." I saw a man climbing up a ladder, which he had placed against the wall. "Missis, oh, missis!" I said, "I'll put de poker in de fire," and in an instant I thrust the poker into the fire. We stood watching the movements of the man, my mistress trembling and being very frightened. He ascended the ladder, and cautiously opened the window, and put his arm in as if feeling. I seized the poker out of the fire and thrust it up his sleeve. "Oh, Lord!" he cried out, and instantly threw himself down from the top of the ladder and disappeared, no doubt well burnt.

My mistress was delighted with my quickness in devising in a moment such a scheme, and always took great pleasure in relating the adventure to any visitors, so that I was looked upon as a faithful and intelligent lad.

Another incident tended also to attach my mistress

Page 24

to me. My grandfather had gone to the mill for some meal. He got drunk, the bag of meal fell from the horse's back, and the pigs devoured the meal whilst my grandfather had gone for some one to help him. When he returned home, my master said, "Will, where is the meal?" My grandfather said, "Don't ask me about the meal; the pigs have eaten it up." My master said, "I will give you a beating." "You had better try it on," said my grandfather. They both began to wrestle with one another. My master tried to get hold of the hair of my grandfather, but, being nearly bald, this was impossible; but my grandfather pulled the hair out of my master's head by handfuls. I danced about in great distraction to see them contending with one another, and ran and got a bowl of water, and threw it on them both, which instantly made them gasp and desist from the struggling. My master fetched the horsewhip, and threatened to kill me for throwing the water, but, at the intercession of my mistress, I escaped. My mistress, the next day, said, "Francis, what made you throw that water on your master and your grandfather?" I said, "Missis, don't you know?" She said, "No." I said, "When ladies and gemmens come to see you and the dogs come wid 'em, dey come in de kitchen, and our dogs jump at 'em, dey get to fighting, den my uncle he throw de cold water on dem, and dat part 'em. Missis, I thought you always know'd dat we parted de dogs in dat way."

Page 25

Social Affections of Slaves.

I went about this time to see several person baptized, all adults, both black and white, and I shall never forget the anxiety displayed by the black men when their wives were being dipped. The black men protested that their wives were held under the water longer than the white women, although there was not a shade of difference in the time of the immersion. The affection of the men for their wives and children would be noticed by any one. The men never, if possible, allow their wives to carry the young ones, but are always delighted to have them in their arms, and to walk by the side of the women.*

*A slave possessing nothing, and rarely hoping to possess anything, except a wife and children, has all his affections concentrated upon them; hence often, when torn from them, he pines away and dies.

The social affections are so strong, that no hard usage can weaken them. Indeed, brutality, on the part of the master, seems to make the slave cling closer and closer; thus intensifying his sufferings, when the "trader" comes to tear him away.

In answer to a question, which has often been put to me, I may here state, that no slave-children are ever christened: a name is agreed upon between the black woman and her mistress, or her mistress's daughters. They take a Bible in their hands, and say, let such be the name.

When I was about fourteen years of age, my mother whipped me, because I had hurt one of my

Page 26

sisters in play. I felt very ill after it, and thought if I feigned to be dead, she would get a whipping. I began to groan out. The women in the spinning-room ran out, thinking I was dying. My mistress's sister, and two young lady visitors, ran into the room; and, feeling I was cold, and noticing that I breathed but slowly--which I was managing, as well as I could, taking a good gasp every time--they turned me over. They also were afraid that I was dying. They began to cry, which brought my mistress into the kitchen. She began to cry, at first; and then, looking stedfastly at me, "Stand by," she said, taking out a pin, unseen by me, she thrust it right into me. I struck out with my feet, and sent a black woman, who had been rubbing me, sprawling on the ground. I holloed out, "Oh! oh! oh!" until they could hear me a mile off. Some ran away instantly, from fear; others burst into loud fits of laughter; my mistress joining in the laugh. "Well," she said, "I never saw such an artful nigger in all my life. He is always up to of his tricks."

I had a tolerably good time of it now, being in the kitchen, helping to cook, or waiting at the table, listening eagerly to any conversation going on; and thus learning many things, of which the field-hands were totally ignorant.

Sunday at Chapel.

On Sundays we were sent to chapel; all the

Page 27

slaves being seated in the galleries, apart from the white people.

Mr. Pain, the minister, was absent from chapel, one Sabbath; but, appearing next Sunday, he explained his absence, by informing his congregation that two of his slaves had run away. Immediately, there was a general lamentation, because brother Pain had lost his slaves; and many calculations were made about their value. The following Sunday, the minister, with a face radiant with joy, announced to his audience, that his slaves had been brought back to him. On hearing this, a hubbub of delight pervaded the chapel; but, when he further informed them, that he had administered to each eighty lashes, in order to teach them their duty, and to deter them and others from running away in future, the audience were overjoyed; one saying to another, "Brother Pain has done perfectly right. He has taught them, and all the slaves who hear, what their duty is, and how they are to be dealt with, if they attempt to run away."

When first I came to England, I was surprised to find every clergyman and Dissenting minister, to a man, denouncing slavery, as contrary to Christianity. But the reverse is the case in the Southern States of America. All the Methodists, Baptists, and Independents--in fact, every minister of religion--uphold slavery, and defend it by passages from the very same Book out of which the clergy, in this country, make quotations to condemn it.

Page 28

I leave the natural inference to be drawn by themselves; merely suggesting, that, perhaps, self-interest may, in other cases also, cause fatal delusions and compliances.

Christmas, how spent by Slaves.

About Christmas, my master would give four or five days' holiday to his slaves; during which time, he supplied them plentifully with new whiskey, which kept them in a continual state of the most beastly intoxication. He often absolutely forced them to drink more, when they had told him they had had enough. He would then call them together, and say, "Now, you slaves, don't you see what bad use you have been making of your liberty? Don't you think you had better have a master, to look after you, and make you work, and keep you from such a brutal state, which is a disgrace to you, and would ultimately be an injury to the community at large?" Some of the slaves, in that whining, cringing manner, which is one of the baneful effects of slavery, would reply, "Yees, Massa; if we go on in dis way, no good at all."

Thus, by an artfully-contrived plan, the slaves themselves are made to put the seal upon their own servitude. The masters, by the system, are rendered as cunning and scheming as the slaves themselves.

"Joe," said a master, "if you will work well for me, you shall be buried in my grave." The slave

Page 29

said nothing, in reply; but thought, Massa is a bad man, and that he would not like to be buried near him. The slave thought he had been too near his master, all his life, and had rather be away from him, when he died. Seeing the slave idling, "Joe," shouted his master, "have you forgotten what I promised you, if you work well?" "No, Massa, me bemember; but me don't want." "What for, Joe?" "Because de debbil might some day come, and steal me away, in mistake for you, Massa." His master was silent on this subject ever afterwards.

Slave Patrols.

On New Year's Day ten white men are chosen, who are called patrols; they are sworn-in at the court-house, and their special duty is to go to the negro cabins for the purpose of searching them to see whether any slaves are there without a pass or permit from their masters. The head of the ten is called Captain. He sends the men into the cabins, waiting outside himself at some distance with the horses, the patrol being a mounted body. If any slaves are found without a pass they are brought out, and being made to strip are flogged, the men receiving ten and the women five lashes each.

Page 30

This is looked upon as great fun by the patrol and the

white people, young ladies and gentlemen from the

verandahs laughing and enjoying the scene. When I have

told of my being flogged, I often hear persons in this

country say, "Oh! but he should not have whipped me in

that manner; I would have resisted, I would have done this,

that, or the other." But, my dear reader, I will tell you a true

story, what I know and saw. Two slaves, who were perhaps not so completely cowed

as the rest, said to my master, who was about to flog them,

"No, massa, we not going to be flogged so much, we won't

submit." "What is that you say?" my master said, starting

back. They repeated, "We are not going to allow you to

beat us as you have done." "How will you prevent it?" he

said. "You'll see, you'll see, massa," speaking half

threateningly. He was evidently afraid of them. When they

went home at night he spoke mildly to them, and told them,

"he only wanted them to do their work, that it would be

better if they could get on in the fields without him. Don't

hurry yourselves, my boys." For two or three days he never

went much among them,

and when he did he spoke in a very quiet, subdued manner.

But mounted negroes were sent with letters to all the

plantations around. The slaves had been sent to a species of

barn where they shell the Indian corn. Suddenly above a

hundred slaveholders, armed with revolvers, marched from

different points, and at one time, evidently agreed upon,

surrounded the place where the negroes were. All the

slaves were ordered out, and the two who had refused to

be flogged were made to strip, and my master first had one

tied up, and flogged him as hard as he could for some time,

the poor slave calling out, "Oh, pray, massa! Oh, pray,

massa!" My master, pausing to take breath, one of the

slaveholders said, "I would not flog him in that way, I would

put him on a blacksmith's fire, and have the slaves to hold

him until I blew the bellows to roast him alive." Then my

master started again and flogged until the poor fellow was

one mass of blood and raw flesh. The other was tied up and

served in a similar manner, one of the slaveholders saying he

ought to be tied to a tree and burnt alive. And now I would

ask, How can an unarmed, an unorganized, degraded,

cowed set of negroes prevent this treatment? The

slaveholders can and do flog them to death, and nothing

more is thought of it than of a dog being killed, and not so

much.

Negroes' Wedding--Vanity Exposed--Love of Long Words--Death of my old Master--Cruelly treated by my dissipated young Master--Slaves sold to pay my Master's Gambling Debts--

Slaveholder's own Children sold to Infamy.Brutalizing Effect of Slavery upon the Ladies.

Consequences to the Slaves of Resisting Tyranny.

Page 31

Page 32CHAPTER III.

THE first wedding which I remember being at certainly afforded a good deal of amusement to me and others who were present. I will, therefore, endeavour to describe it as well as I can. The black man was named Jerry, and his intended, Fanny. Jerry went to learn from Fanny's master and mistress whether they would allow him to take her for his wife. Fanny's mistress said, "Jerry, do you love her?" He said, "Yers, marm." "How do you know?" she said. "Because me lub ebery ting on de plantation since me lub Fanny,--de hosses, and all de tings on de plantation seems better dan anybody else's. It seems to me Fanny got de best missis in de country; me give most anyting if me could fall into dis family," said Jerry. Mr. Ord, Fanny's master, said, "Come, Elizabeth, you must let him have her." She said, "Well, Jerry, you can have her, but we don't whip Fanny, and you must not whip her." Jerry bowing low, said, "No, missis, if she never get a whipping till me gives it to her, she'll neber get one, cause me lub

Page 33

her too well to whip her." Fanny's mistress said, "Because I know if you were to whip her, she would not deserve it, and I should never let you come on the premises again." Jerry replied, "By de time me have had her one year me know you'll give me as good name as Fanny, for Fanny's mistress shall be my mistress, and Fanny's master shall be my master." "Well, Jerry," said Fanny's mistress, "you must bring January's Tom or Morton's Gilbert to marry you, two weeks from this night, if your master and mistress consent, and tell your master and mistress that we have agreed to give Fanny a supper, and we shall be very glad to see them, since we are going to have a great many ladies and gentlemen come to see the wedding." Jerry in ecstasy answered, "Yers, marm; thank you thousand and thousand times, missis."

On the Saturday night appointed, Jerry went with January's Tom to Fanny's master's. Jerry had a pair of black trousers of his master's on, a little too large in the leg, and a coat fitting very well, except that the tails were too long; some one had given him a white waistcoat and a white cravat, which was only a little less stiff than its wearer, and a pair of white gloves, contrasting very much with the coal black of Jerry's shining face. Fanny's mistress had dressed her in a white muslin gown and very nice light shoes, her head being decked with white and red artificials, made from goose's down, which accorded well with her woolly

Page 34

hair. Her bridesmaid was attired somewhat similarly, only with not quite so many artificials. The happy pair were seated in the middle of a large kitchen; Fanny had a very pleasant countenance, a tawny complexion, and was admired very much by her mistress and her friends, but most of all by Jerry. He was asked if he would have her. "Yers, indeed me will," he said. Fanny was very bashful, and spoke very low, and bowed. "Come, where is the parson?" said her mistress, "it is time for him to be marrying them." "Parson!" some of the ladies called out, "Parson!" At the sound of this dignified title, bolt upright jumped January's Tom. "Marm, yers, marm." "It is time for you to marry them." "Yers, marm, yers, marm!" said Tom.

Now, January's Tom not being able to read, had listened to his master's grandson reciting the marriage service until he had it by heart, and as luck or mischief would have it, the Prayer-book was laid upside down. Tom now commenced, with the book in this position, to read the service, amidst the infinite mirth of the ladies, who every now and then glanced over his shoulder at the inverted book. Tom, however, thinking all the laughter was at the happy couple, persevered in the most solemn manner. Having finished repeating the marriage service to the satisfaction of all, Fanny's mistress said, "Parson, make him salute his wife." Now, Jerry being a field hand, knew nothing about this grammar word "salute." "What! do what?"

Page 35

he said. "Salute your bride," said the parson. "Wh-a-t! do what?" said Jerry, as much puzzled as if it had been a Chinese word. Perceiving the perplexity, Fanny's mistress said, "Parson, tell him to kiss his wife." The parson said, "Kiss your wife." Jerry said, "Do you mean me to 'bus' her? What for you not tell me afore?" and instantly seizing Fanny round the neck, he made the room resound with the smacks, amidst the roars of laughter of all, until Fanny's mistress told him that would do, when, reluctantly, he desisted. Fanny's master then wished Jerry to tell the company how he got his wife. He said, "Ladies and gemmen, me will tell you how me come to see Fanny. Me went to see Mr. Marshall's Charlotte for two years, she promised to hab me. Me promised to bring her a straw bonnet, but de grubs had eaten all on my truck-patch (the piece of ground allotted by some good masters for the slave to cultivate for his own benefit). Me went to see Charlotte on de Sunday, and she asked me to sit down in de kitchen, and she say, 'Where de bonnet?' Me told her de reason me didn't get it. And she said, 'You worthless nigger, you can't hab me,' and she run de fork into my arm, and me run home and say, 'De debble must be in dat gal.' Me went, to see good many gals after dat; me see good many like Charlotte, but me wouldn't stop, me leave, till me come to see Fanny. She seem to be good natured gal, but she hab me come to see her good

Page 36

while afore she say she hab me. Me tell her dat me lub her better dan all de people in de world. She say, 'if she could believe dat, she would hab me.' Me said me would treat her kind, and treat our chilun kind; but when me say dis about de chilun, she ran out of de house, and me didn't see her of three or four weeks apter dat. Me den see her, but me didn't tink dat she would run de fork in my arm, as Charlotte did. Fanny ask me 'if me rebberence her.' Me say, 'Fanny, don't know what you mean.' She say, 'Massa rebberence Missis, and you must rebberence me.' Me say, 'Oh, yes, to be sure; and you be good to me?' She say, 'If you be kind to me, I be kind to you.' And dat made me feel happy."

Thus ended Jerry's interesting account of his courtship.

Then about 300 slaves, friends of the happy couple, sat down to a good supper. Fanny being a house-servant, presided, with considerable tact, at the head of the table, and Jerry at the opposite end, in rather a confused and awkward, but good-humoured manner. A bottle of whiskey was on the table, and Jerry was called upon to give a toast. "Me don't know what you mean by de toast," said Jerry. Fanny's mistress said, "We'll tell you." He said, "Me can't talk, but me do as well as me can. Dis is my heart dat will be talking to you. Me hope Fanny's massa and missis neber will come to want, and me hope all de family, when dey die,

Page 37

may go to heben, and me hope dat Fanny and myself neber will be parted from each other, nor our chilun." At the last word all laughed heartily.

During twenty years after their wedding, I knew this happy pair, with a dutiful family of sons and daughters around them. A kind Providence had granted poor Jerry's prayer; a good master and an indulgent mistress were vouchsafed to them, on the same plantation their children were, some of them working, and the little ones playing about; and my sincere wish is, that no change of their master's fortune may send the "dealer" to tear asunder those whom affection of the purest kind had so firmly cemented together.

Vanity Exposed.

Having been made cook, I got on for some time tolerably well, sending up the dinners in first-rate style, exerting myself to the utmost, for I had a favour to ask, and I knew the best way to get at the hearts of my master and mistress was through their stomachs. I had noticed three or four watches hanging about the house, and one very old-fashioned, and evidently not of much value; I thought I should like to have it to wear on a Sunday at chapel. I asked my mistress, who was friendly towards me, to intercede with my master for the loan of it. "Yes, Francis," she said; "be a good fellow; manage the dinners well." "Yers, missis," I said, "I am sure

Page 38

to do that." And, sure enough, all was dished up carefully. In the course of a short time the watch was given to me, and off I went to the chapel, having made myself as spruce as possible. On my way, every time I passed any one I pulled my watch out to display it. I walked up into the gallery of the chapel and looked down upon my fellow-negroes without watches as ten degrees beneath me in point of dignity. During the sermon I pulled out the watch several times, catching the eye of the preacher. At last he paused, and, looking at me, he said, "Ah! that must be a very good negro, a very good negro indeed; I see he has got a watch. Pray (looking stedfastly at me) can you tell me what o'clock it is?" I looked hastily at my watch, and replied, "Five o'clock." Instantly there was a loud laugh through the chapel, for it was only half-past twelve. My mistress ridiculed me afterwards, and said she could teach me nothing, and all my fellow-negroes made me a perpetual butt for their jokes. The fact was, I knew no more about the watch than the watch, knew about me.

Love of Long Words.

I one day overheard a young lady who was visiting at our house say to my mistress, "My intended will be here in a few days, I wish you would have everything put right." I thought, "When he comes, I'll hear what he has to say to you, and then

Page 39

I shall know how to court the black girls when I go out." Two or three days afterwards the young gentleman arrived, and I was on the alert to hear what he had to say to the young lady. I thought I heard him say, "Miss, I do admire your beauty, I respect your ingenuity, and I adore your virtue; I do love you, because I cannot help it." I was listening like a cat watching for a mouse. I repeated what I had heard over and over again until I got it perfect, and I then felt proud, because I thought I should have something superior to say when I went among the girls. But the next time I listened I made a great mistake. I heard a gentleman who was talking to some young ladies say, "I learnt my grammar well when I went to school." In a few minutes afterwards I heard him make use of the word characteristic. I thought he said, "cutting up sticks." I was delighted, and went on repeating "cutting up sticks." I thought it was a nice grammar word to speak when I should go among the black girls. The first time when I went among some who were having a little spree, a black man was seated by a very nice girl I knew; I said to her, "I can speak grammar;" she said, "You can? what is it?" I said, "It is cutting up sticks." She gave the black man a blow with her elbow and said, "Go away; I am going over to sit with our friend; he can speak grammar; it's cutting up sticks." It was sometime before I found out my mistake. I knew I could not learn anything

Page 40

from the slaves, and I was, therefore, constantly listening to the gentlemen and ladies, and endeavouring to learn as many words as possible from them. Many times I was mistaken, but, right or wrong, I could march into a room with full-blown importance, and cut out a dozen men by bumptiously repeating anything which I had overheard. The black girls always like something which is a little better than common conversation.

The Death of my old Master.

I was about twenty-eight or thirty years of age when my old master was seized with a fever. He was upwards of seventy years of age, and, prior to this, had been a healthy man. No change whatever of a serious nature had taken place in his conduct or conversation; indeed, a few days before the fever, he had been cursing and blaspheming at a slave-woman. When he was taken ill, the family wished to send for a doctor. "No," he said, "I know it is of no use; I shall die." However, one was sent for. Some of the planters, his neighbours, came, to be with him, and, as the fever increased, he began to rave and cry out, "Oh, take it away! take it away!" One of the slaveholders was very much frightened, for he also thought that he saw something. In a few days my master died, but he never made any sign that he had any hope for the future. His will had been recently made, his slaves

Page 41

were apportioned to his four children, and his son said that his father had never wished them to free the slaves.

Cruelly treated by my dissipated young Master.

My young master now was about twenty-four or twenty-five years of age; he did not seem to mourn much for his lost father, but said, "You slaves have been living upon white bread, but I will soon teach you something different from that. You shall now have the treatment proper for niggers. I have been wishing for some time to tan your hides for you." Of course his discourse was interlarded with oaths and curses, with which I cannot pollute my page. I soon began to wish that I was a field-hand, for day by day he was drunk and hanging about the kitchen.

I began to have a terrible life of it. A few years before his father's death, he had led a riotous, dissipated life, losing money by gambling, and then borrowing. All his neighbours were astonished at the amount of his debts, for the sheriff's officers were constantly on the premises. No doubt the state of his circumstances made him drink more.

Slaves Sold to pay my Master's Gambling Debts.

The slaves are in general the first property parted with, a dozen likely niggers bringing in a tolerably

Page 42

round sum. Aunt Aggy was the first slave sold; she had a little boy eight or nine years of age, and when she was driven to the chained gang on the road he ran after her, crying, "Mother--mother; oh my mother." My master ordered one of the slaves to fetch him the waggon whip. He took it and lashed the poor little fellow, round the neck and legs until he fell down, then he flogged him until he got up again, and still my master cut at him until the boy shrieked out dreadfully, writhing in agony, the blood streaming down his little legs. His mother was driven off with the gang, and her little boy never saw her more. In three or four weeks after this, a "trader" was seen talking to my master. The slaves were in a state of consternation, saying, "Is it me? Is it me? Who'll go next?" One of the slaves said, "See, they are selling the pigs to go to Virginia. They don't seem to care, but we can't be like pigs, we can't help thinking about our wives and children."

The slaves were all taking their dinners in their cabins about two o'clock. My master, the "trader," and three other white men walked up to the cabins, and entered one of them. My master pointed first to one, and then to another, and three were immediately handcuffed, and made to stand out in the yard. One of the slaves sold had a wife and five children on another plantation; another slave had a wife and three children; and the other had a wife and one child. My master, the dealer, and

Page 43

the others then went into another large cabin, where there were eight or nine women feeding the children with Indian-meal-broth. My master said, "Take your pick of the women." The poor things were ready to drop down. The "trader" said, "I'll give you 800 dollars for that one." My master said, "I'll take it." The "trader," touching her with a long cane he had in his hand, said, "Walk yourself out here, and stand with those men." She jumped up and laid her child out of her arms in an old board-cradle, and walked to the chained men. My master said, "Take your pick of the rest." The "trader" looked round and said, "I'll give you 750 dollars for that one." "I'll not take it," my master replied. "What will you take?" said the "trader;" "what is the least you'll take?" My master answered, "Not a dollar less than I took for the other." The "trader" paused a minute or two, surveying her, and then said, "I'll give it." Then, holding his cane out, said, sternly, "Walk out of this, and stand with those men." She laid her child in one of the women's arms, and speaking low, said, "Take care of my child, if you please." The women were so terrified that they dared not say a word, for three or four weeks before this time this very "trader" had given 1,000 dollars for a slave to a Mr. W., a neighbouring planter. The slave had said it was hard for him to be carried away from his wife and children, the "trader" instantly beat him so unmercifully, that Mr. W. thought

Page 44

the poor slave would be killed, and said, "You are not going to throw away your money in that way, are you ?" "I don't care," said the "trader," "I have bought him, he is mine, and for one cent. I would kill him. I never allow a slave to talk back to me after I have bought him." He had beaten the poor fellow so severely that he could not walk. The "trader" said to Mr. W. he should be passing that way again in about a month, and if they would take care of the slave and cure him, he would pay the damage, and either call or send for him. The three men and two women were driven out to the gang on the highway, and chained together, two and two. We never heard of them again. One of the wives left behind was nearly driven mad, she took it so to heart. No doubt those sent away were quickly used up in the sugar plantations and rice swamps of the South. But the masters soon replace the dead ones with others. There is an abundant supply in the markets of the breeding States, of all kinds, field and house hands, some bringing long prices, so that a slaveowner finds the sale of them the readiest mode of extricating himself from any pecuniary difficulty.

Slaveholders' own Children Sold to Infamy.

Even his own child, by a black woman or a mulatto, when the child is called a quadroon, and is very often as white as any English child, is frequently

Page 45

sold to degradation. I knew a ---- S----, Esq., he sold his own daughter, a quadroon, to a gentleman of New Orleans for 1,500 dollars, who said "he only wanted her to be housekeeper for him, and to be mistress over the other niggers, and to do just as he wanted her, for he had no wife." This startled the poor girl, who said she would not have cared if she had been going to marry him. She took it very much to heart, and so did her unhappy mother, especially when she heard her child say, "Oh, mother, I hope there will come a day when those left behind will not be forced as I shall be." And surely that day is being heralded in now, amidst the flaming homesteads and the slaughter of the sons and dishonour of the daughters of these heartless oppressors of their fellow-man, aye, of their own flesh and blood. There are thousands upon thousands of mulattoes and quadroons, all children of slaveholders, in a state of slavery. Slavery is bad enough for the black, but it is worse, if worse can be, for the mulatto or the quadroon to be subjected to the utmost degradation and hardship, and to know that it is their own fathers who are treating them as brutes, especially when they contrast their usage with the pampered luxury in which they see his lawful children revel, who are not whiter, and very often not so good-looking as the quadroon.

I remember, one bright moonlight night, a fine young man, a quadroon, striping his shirt off, and

Page 46

showing me his lacerated back. He cried, and I cried too, to see him in such a state. He said the next time his father attempted to flog him, he would run a dirk-knife through him. He produced the dirk, and said he had bought it on purpose. I begged of him not to think of such a thing. He swore he would; and the next time his master was going to whip him, he pulled out the dirk, and ran through the house. His father sold him soon after this. I saw him afterwards. He had been sold to a hatter, and a smarter or more gentlemanly-looking young fellow I have rarely seen. He said, "Oh, Francis, I am so glad that you persuaded me not to kill my master. I have got a good master now, and, if not sold, I shall be happy." That which in my own case weighed most heavily upon my mind was the thought that all my work was for another; and that even the flesh and blood, the bone and sinew, which God had given me, I could not call my own. I never had parted with them, but another called them his. Heaven will, no doubt, in its own good time, redress this shameless, cruel, infamous wrong.

Page 47

CHAPTER IV.

Corn Songs in Harvest-time--Conversion.

IN harvest-time, thirty or forty years ago, it was customary to give the slaves a good deal of grog, the masters thinking that the slaves could not do the hard work without the spirits. A great change has taken place now in this respect; many of the planters during harvest give their slaves sixpence a-day instead of the whiskey. The consequence is there is not a fifth of the sickness there was some years ago. The country is intensely hot in the harvest-time, and those who drank grog would then want water; and, having got water, they would want grog again; consequently, they soon either were sick or drunk. All round where I dwelt the sixpence was generally substituted for the spirits; the slaves are looking better, and there are fewer outbreaks in the fields. In the autumn, about the 1st of November, the slaves commence gathering the Indian-corn, pulling it off the stalk, and throwing it into heaps. Then it is carted home, and thrown into heaps sixty or seventy yards long, seven or eight feet high, and about six or seven feet wide. Some of the masters make their slaves shuck the corn. All the slaves stand on one side of the heap, and throw the ears over, which

Page 48

are then cribbed. This is the time when the whole country far and wide resounds with the corn-songs. When they commence shucking the corn, the master will say, "Ain't you going to sing any to-night?" The slaves say, "Yers, Sir." One slave will begin:--

"Fare you well, Miss Lucy.

ALL. John come down de hollow."

The next song will be:--

"Fare you well, fare you well.

ALL. Weell ho. Weell ho.

CAPTAIN. Fare you well, young ladies all.

ALL. Weell. ho. Weell ho.

CAPTAIN. Fare you well, I'm going away.

ALL. Weell ho. Weell ho.

CAPTAIN. I'm going away to Canada.

ALL. Weell ho. Weell ho."

One night Mr. Taylor, a large planter, had a corn shucking, a Bee it is called. The corn pile was 180 yards long. He sent his slaves on horseback with letters to the other planters around to ask them to allow their slaves to come and help. On a Thursday night, about 8 o'clock, the slaves were heard coming, the corn-songs ringing through the plantations. "Oh, they are coming, they are coming!" exclaimed Mr. Taylor, who had been anxiously listening some time for the songs. The slaves marched up in companies, headed by captains, who had in the crowns of their hats a short stick,

Page 49

with feathers tied to it, like a cockade. I myself was in one of the companies. Mr. Taylor shook hands with each captain as the companies arrived, and said the men were to have some brandy if they wished, a large jug of which was ready for them. Mr. Taylor ordered the corn-pile to be divided into two by a large pole laid across. Two men were chosen as captains; and the men, to the number of 300 or 400, were told off to each captain. One of the captains got Mr. Taylor on his side, who said he should not like his party to be beaten. "Don't throw the corn too far. Let some of it drop just over, and we'll shingle some, and get done first. I can make my slaves shuck what we shingle tomorrow," said Mr. Taylor, "for I hate to be beaten."

The corn-songs now rang out merrily; all working willingly and gaily. Just before they had finished the heaps, Mr. Taylor went away into the house; then the slaves, on Mr. Taylor's side, by shingling, beat the other side; and his Captain, and all his men, rallied around the others, and took their hats in their hands, and cried out, "Oh, oh! fie! for shame!"

It was two o'clock in the morning now, and they marched to Mr. Taylor's house; the Captain hollowing out, "Oh, where's Mr. Taylor? Oh, where's Mr. Taylor?" all the men answering, "Oh, oh, oh!"

Page 50

Mr. Taylor walked, with all his family, on the verandah; and the Captain sang,

"I've just come to let you know.

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. The upper end has beat.

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. But isn't they sorry fellows?

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. But isn't they sorry fellows?

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. But I'm going back again,

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. But I'm going back again.

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. And where's Mr. Taylor?

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. And where's Mr. Taylor?

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. And where's Mrs. Taylor?

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. I'll bid you, fare you well,

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. For I'm going back again.

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

CAPTAIN. I'll bid you, fare you well,

And a long fare you well.

MEN. Oh, oh, oh!

They marched back, and finished the pile. All then went to enjoy a good supper, provided by Mr. Taylor; it being usual to kill an ox, on such an occasion; Mr., Mrs., and the Misses Taylor, waiting

Page 51

upon the slaves, at supper. What I have written cannot convey a tenth part of the spirit, humour, and mirth of the company; all joyous--singing, coming and going. But, within one short fortnight, at least thirty of this happy hand were sold, many of them down South, to unutterable horrors, soon to be used up. Reuben, the merry Captain of the band, a fine, spirited fellow, who sang, "Where's Mr. Taylor?" was one of those, dragged from his family. My heart is full when I think of his sad lot.

Conversion.

One day, when I was between twenty-five and thirty years of age, an elderly lady, who was on a visit to my mistress, came into the kitchen, and, after speaking to me about things in general, for a short time, she took a Bible out of her pocket, and said, "Would you like to hear me read something about our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ?" I said, "Please, marm." She said, "If your mistress should get to know that I have been reading to you, she would be very angry, and drive me from the house." She then read that portion of Scripture, where it says, "All that forget God shall be turned into hell." There was such an evident sincerity about the good old lady, and her manner was so kind, that every word which she either read or spoke to me went to my heart. Here was truth

Page 52

presented to me, by one whose only possible object could be to do me good.

I listened eagerly to every word which fell from her lips. She told me, if I believed on the Lord Jesus Christ, I should be saved; that God was no respecter of persons; that He loved all His people, black as well as white. She told me, if I loved God, and showed it by my conduct, He would love me, and at last take me to heaven, to live with Him; that the Gospel was commanded, by our Saviour, to be preached to all people; and that He died for the sins of all men, that they, through Him, might be saved. And many such encouraging passages, she either quoted, or gave me the substance of. She promised, that, when she came again, she would give me a spelling-book.

She said, "I know you are allowed to go to the chapel, but there the preachers only preach what will be agreeable to your masters. The real naked truth of the Gospel, the glad tidings that were intended to comfort all hearts, you never hear."

All this conversation was carried on in a secret manner, lest my master or mistress should have the slightest hint of any such thing.

At night, I turned over in my mind every word which had been said; and I resolved, from that time forward, to put my trust in God, and get to know as much as I possibly could about Jesus Christ.