Life and Opinions of Julius Melbourn;

with Sketches of the Lives and

Characters of

Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, John Randolph, and

Several Other Eminent American Statesmen:

Electronic Edition.

Hammond, Jabez D. (Jabez Delano), 1778-1855, ed.

Melbourn, Julius, b. 1790.

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Lee Ann Morawski

Text encoded by

Lee Ann Morawski and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2000

ca. 450K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) Life and Opinions of Julius Melbourn; with Sketches of the Lives and

Characters of Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, John Randolph, and Several Other Eminent

American Statesmen

A Late Member of Congress

239 p., ill.

SYRACUSE:

PUBLISHED BY HALL & DICKSON. NEW YORK:--A. S. BARNES & CO.

1847.

Call number VC326.92 M51 (North Carolina Collection, University of

North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the

American South.

The text has been

encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar,

punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved.

All footnotes are

inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as

--

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and

Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- Melbourn, Julius, b. 1790.

- African Americans -- North Carolina -- Raleigh -- Biography.

- Slaves -- North Carolina -- Raleigh -- Biography.

- Free African Americans -- North Carolina -- Raleigh -- Biography.

- Slavery -- North Carolina -- Raleigh.

- United States -- Description and travel.

- United States -- Politics and government -- 1815-1861.

- Slaves' writings, American.

Revision History:

- 2001-01-22,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-09-07,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-09-01,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-08-27,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

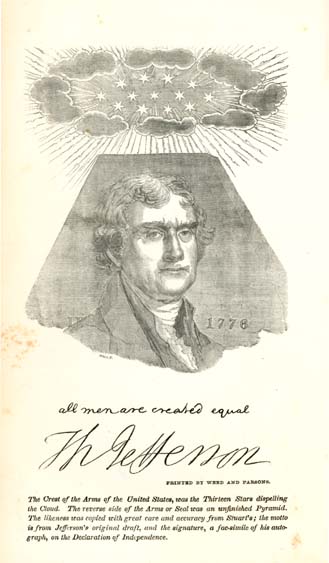

all men are created equal

Th Jefferson

PRINTED BY WEED AND PARSONS.

The Crest of the Arms of the United States, was the Thirteen Stars dispelling the Cloud.

The reverse side of the Arms or Seal was an unfinished Pyramid. The likeness was copied with great care and

accuracy from Stuart's; the motto is from Jefferson's original draft, and the signature,

a fac-simile of his autograph, on the Declaration of Independence.

[Frontispiece Image]

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

LIFE AND OPINIONS

OF

JULIUS MELBOURN;

WITH

SKETCHES OF THE LIVES AND CHARACTERS

OF

THOMAS JEFFERSON, JOHN QUINCY ADAMS,

JOHN RANDOLPH,

AND SEVERAL OTHER EMINENT AMERICAN STATESMEN.

EDITED BY

A LATE MEMBER OF CONGRESS.

SYRACUSE:

PUBLISHED BY HALL & DICKSON.

NEW YORK:

--A. S. BARNES & CO.

1847.

Page verso

Entered, according to an Act of Congress, in the year 1847,

BY HALL & DICKSON,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Northern

District of New York.

Page 3

PREFACE

BY THE EDITOR.

INDEPENDENT of the merits or demerits of the style of the following work, or the talents or defect of talents which the writer may have displayed, the publishers may with great propriety ask themselves who they can reasonably hope will patronise this book?

It is quite certain they cannot expect the approbation of either of the two great political parties in the nation; for the errors and faults of both parties in the course of the work are pointed out without reserve and animadverted upon with freedom. Nor can the publishers hope for the general support of the people inhabiting any particular part of the United States; because the author upbraids the northern and western sections of the Union with pursuing a cold and selfish policy from mercenary motives, and with a political subserviency to the South caused by a love of office and its emoluments; while at the same time he charges the slaveholding states with sustaining unjust and tyrannical laws, and grossly violating human rights. Even the Christian Church in America, and its clergy, with some honorable exceptions, the author does not hesitate to accuse of pursuing the expedient rather than the right course, and of being greatly influenced by sinister motives. But as a very slight examination of the book will show that the author is opposed to slavery in all its forms, may not the publishers, it will be asked, flatter themselves that it will receive the support and patronage of the Abolition party? Alas for the Trade! they must not lay even "this flattering unction to their souls," for the author charges the Abolitionists with narrow and selfish views; and as a

Page 4

party, he disapproves of many of their schemes and condemns their policy.

This view of the general tenor of the book and of the state of public feeling, it must be confessed, presents an unpromising and cheerless prospect to the publishers. But are there not many individuals in all the various sects in religion, and in all the political parties, who will read with patience and consider with candor, facts and arguments, notwithstanding those facts and arguments may militate against their own particular sect or party? It is believed there are, and that they are considerable in numbers, and we know that many of them are highly and deservedly distinguished for their merits, their talents, and their patriotism. It is to that portion of the American public that we appeal.

It may be said, and said truly, that in the story of Mr. Melbourn, as related by himself, there is nothing mysterious or remarkable, inasmuch as all the incidents which happened to him, though they may not all have occurred to one man alone, have frequently occurred, some to one and some to another individual. But conceding that Mr. Melbourn's narrative may not gratify curiosity or afford amusement, because it contains nothing mysterious or improbable, it is, in the opinion of the editor, for that very reason the more interesting. Have the events recorded in Mr. Melbourn's autobiography frequently occurred, and are they still daily occurring in our country--a country which boasts of its zeal for freedom and its devotion to civil liberty--a country whose political parties proudly inscribe on their banners "EQUAL RIGHTS" as their motto--and shall not the occurrence of such events "excite our special wonder?"

The remarks and reflections of Mr. Melbourn during the space of twenty years, the greater part of which he spent in the northern cities of the Union, are, it is true, extremely desultory, and some of the conclusions to which he arrived may be considered by the mere business man, or the busy and zealous politician struggling for place and power, as unjust; but it ought to be remembered that Melbourn belonged neither to the European nor African race; that his African blood excluded him from a familiar intercourse with good society; that he nevertheless possessed a cultivated and highly sensitive mind; that he was independent in his pecuniary circumstances;

Page 5

and yet that in reality he had no associates. His position was like that which it may be supposed would be the position of a being who was a native of one of the planets of the solar system other than the earth, and who should visit this world and remain here for twenty years, and devote his time to making critical observations on what should be passing among its inhabitants.

Thus situated, it is not wonderful that Melbourn should occasionally have taken rather sombre views of men and things around him.

His sketches of the lives and characters of several eminent American statesmen, though very brief, will, it is believed, be found strictly correct. Indeed the accuracy and truthfulness with which he paints, proves that his portraits were drawn from personal knowledge and observation. His account of the proceedings in Congress when the State of Missouri was admitted into the Union, and of the Presidential elections in 1817 and 1824, will be admitted, by many persons now living, to be sober and veritable history.

But it is to be feared that Mr. Melbourn has in one respect, if none other, committed a sin altogether unpardonable. He has dared to applaud Great Britain for its toleration of independent individual opinion, and the free expression and advocacy of them, and also for the stern and unyielding protection its government affords to the personal rights and the personal liberty of each human being who places his foot on British soil.

There is a certain class of American reviewers and editors of newspapers, who seem to regard it as the most conclusive evidence of patriotism to condemn every thing British, and to applaud every thing American. In fact, it cannot be denied that many enlightened, and in other respects liberal-minded men, either from early prejudice or from a secret desire to pander to the morbid appetites of the less-informed portion of the American people, denounce with great severity and bitterness any thing said in favor of the state of society, the institutions, or even of the philanthropic efforts which have been or are being made by either the government or people of England. This habit of thinking and acting is unquestionably wrong. A man or a people of true magnanimity will always do justice even to an enemy. Why, then, should we be unwilling to

Page 6

render justice to a nation with whom we are at peace, with whom we have much intercourse, from whom we derive a large portion of our literature, and from whom we are descended?

It may, however, be true, that from the treatment which Mr. Melbourn received in this his native country, when compared with the position in society he and his family were permitted to occupy upon their arrival in England, his mind may have become unreasonably biased and prejudiced against the country of his birth, and in favor of the one he has adopted. It is, therefore, hoped, that the candid reader will make due allowance for the circumstances under which Mr. Melbourn wrote.

Page 7

LIFE OF JULIUS MELBOURN.

I WAS born a slave, on a small plantation about ten miles from Raleigh in North Carolina, on the fourth day of July, 1790. It is probable that the accidental circumstance of my coming into the world on the great day which is the anniversary of American Independence, occasioned the day of my birth to be remembered in my master's family, and the mention of the fact in my presence, after I arrived at a sufficient degree of maturity to understand what was passing, has enabled me to be certain of my age. In this I differed from many, perhaps the majority of field-slaves, who are quite ignorant of their age.

My master, Major Johnson, whose Christian name I am unable to give, I have been told was a sutler in the army when Lord Cornwallis, during the Revolutionary war, over-ran the Southern states; and occasionally performed some service in the quartermaster department in the American army. He saved a considerable sum of money, which he accumulated during the war, and when it terminated, he invested the most of it in public securities of North Carolina and other states, for two shillings and sixpence and three shillings on the pound, which securities, after the adoption of the federal constitution, were funded, and became a part of the national debt. These securities immediately rose to their par value,

Page 8

and shortly afterwards above it, so that what Major Johnson paid two shillings and sixpence for, while in his hands came to be worth twenty shillings, and eventually twenty-two and twenty-four shillings. He claimed that he had been a revolutionary patriot who had fought and bled for his country, and was an ardent lover of liberty, and a great enemy to British tyranny; and, from his real or pretended military services, he was known as Major Johnson. I have, it is true, heard it asserted by those who were politically opposed to him, that he carried on an illicit trade with the enemy during the war, and in return for their favors to him, that he occasionally furnished them with information respecting the movements and strength of the American army, and, that by such means he was enabled to purchase goods, which he sold at a most exorbitant price to his American brethren. But these outgivings were probably slanders emanating from personal envy and party malice; for he obtained a pension under the law of the United States passed during the administration of Mr. Monroe, which he enjoyed till his death.

My mother was the daughter of a slave of Major Johnson, and was born a year or two before the war broke out between Great Britain and her colonies. She was a mulatto, and as her mother was entirely black, her father must of course have been a white man. Major Johnson sold my grandmother before I was born, but kept my mother. I am utterly ignorant of my father, but am certain he was a white man, because, although my mother, as I have stated, was a mulatto, I am as white as most men, and indeed whiter than the Spaniards and Portuguese; and what is remarkable, and almost unaccountable, I have blue eyes, and my complexion is what would generally be denominated light. The only evidence afforded by my appearance that I am allied to the negro race is, my hair is curly, or rather a little woolly, and my nose is more flattened than is generally the case with the nose of a pure-blooded European.

Page 9

It is, however, certain, that I am one quarter African, and although this portion of negro blood has subjected me to much distress and suffering, strange as it may appear, that blood is much dearer to me than all the Saxon blood that runs in my veins. I shall not attempt to account for this in any other way than by referring to the known and acknowledged fact, that mothers always feel the most ardent affection for that child who has been the most unfortunate, and who has given them the greatest pain and anxiety.

My recollection of my mother is very indistinct. She could not have been more than seventeen or eighteen years old when I was born. She was kept by my master as a field-slave, and bearing a child when she was so young, the fatigue incident to her employment, and the scantiness and coarseness of her fare, rendered her so feeble that she was incapable of performing as much field labor as was required of her; for this reason, and as Major Johnson possessed as many house-slaves as he needed, he determined to sell her to a negro-buyer who was purchasing a stock of slaves to send to Georgia, a considerable part of which state was then uncultivated, but which at that time was rapidly settling. This created a great demand for slaves in that quarter, and raised the price of them in the Carolinas, Virginia, and Maryland. The day my mother was separated from me is among my earliest and most painful recollections. I was then about three years old, yet I remember the dreadful sensations I experienced, when she wildly, for the last time, pressed me to her bosom; and can almost now feel her scalding tears as they fell upon my face. In a moment she was forced from me, shrieking and in the madness of her grief tearing her hair; but forthwith her master ordered her manacled. I can never forget the chill of horror that thrilled through my veins when I heard the clink of the hammer used in riveting the rings which enclosed her wrists and fastened them to a bar of iron. My poor mother was soon marched off with a

Page 10

gang of slaves, and I have never seen or heard of her since. Such was the feebleness of her constitution, that I solace myself with the reflection that, in all human probability, she must soon have perished in the damp and chilly rice-fields of Georgia.

I lived in Mr. Johnson's family till I was five years old, when Mrs. Melbourn, a widow lady who resided in Raleigh, purchased me; and to her I am indebted for my education and liberty, and every thing that is valuable in life.

Mrs. Melbourn was the widow of Lieut. Melbourn, of the British navy, who was killed in the great battle between Admiral Graves and Count de Grasse, which occurred shortly after the close of the Revolutionary war. Mrs. Melbourn before her marriage had a small estate, which was secured to her in the English funds, amounting to £3000 sterling; and after her husband's death she received a pension, during her life, of £200. She was an educated woman, and very pious, being a zealous member of the Methodist Society; and there is reason to believe that the illiberal treatment which that sect, in common with other dissenters, received from the government, induced her to turn her attention to America, and produced in her mind a train of reflection upon the civil and religious rights of man. Mrs. Melbourn had but one child, and that was a son, who, at the death of his father, was about seven years old; and she was so pleased with the sentiments put forth on the subject of the rights of man by the American orators and statesmen, at the commencement and during the American revolution, that she determined to remove to America, and educate her son in the United States. She therefore, within a few years after the death of Lieut. Melbourn, made such arrangements of her pecuniary affairs in England, as enabled her to put in execution her scheme. There were few persons in America to whom she was known. She had, however, a slight acquaintance with Mr. Gale, a printer, who emigrated from England, and who then had recently commenced

Page 11

the publication of a newspaper in North Carolina.*

* Joseph Gale, Esq., who has so long, and with such distinguished ability, been the senior editor of the National Intelligencer, is probably the son of this gentleman.--Editor.

This circumstance probably induced her to go to North Carolina, and take up her residence at Raleigh.

On a visit to Mrs. Johnson, when I was, as I have stated, about five years old, Mrs. Melbourn saw me, and was so pleased with me that she purchased me of Major Johnson. Her religious and political principles rendered her zealously opposed to slavery, and she purchased me with the intention of causing me to be educated and giving me my freedom. Under her charge I was well provided for, and received a good English education. She brought with her from England Lieut. Melbourn's private library, which was remarkably well selected. It contained, among other valuable books, all the British classics, an excellent collection of Ancient and Modern History, and the best works of fiction then extant. To this library I had free access, and from it I derived much amusement, and I hope some profit.

When I was ten years old, Mrs. Melbourn sent me to a select school in the vicinity of Raleigh; but, on account of the African blood in my veins, I was not permitted by the managers of the school to remain there long; so that the education I afterwards acquired, was obtained from the instructions of a Methodist preacher, who was an almost constant inmate of our family, and from Lieut. Melbourn's library.

Mrs. Melbourn's son, whose name was Edward, when I was little more than twelve years old, was sent to finish his education at Princeton College, in New Jersey; and as Mrs. M. kept an English man-servant, I had abundance of leisure to pursue my studies; and the boys of my age declining to associate with me on such terms of equality as I thought I was entitled to, it is probable I spent less time in the pursuit

Page 12

of amusement, and more hours in study, than I should have done had I been treated by those white children of my own age in such a manner as to render my association with them agreeable.

There resided near Raleigh a gentleman by the name of Boyd, then somewhat advanced in years, who was the owner of a considerable estate, and who, during the first part of the existence of the state government, had been an active and influential politician, but had, for several years before the time of which I speak, retired from all public employment.*

* During the revolutionary war he commanded a regiment of militia, and on several occasions distinguished himself for his bravery, and as a judicious military officer.

His wealth, his public services, and, more than all, the excellent qualities of his head and heart, caused him to be universally respected and beloved.

Col. Boyd's wife had died many years before, and had left him an only child, a daughter, who was now about fifteen years of age, and a most lovely girl. I have no talent at describing the persons of individuals; and if I had, beautiful females have been so often described by writers, (and really, as they appear in books, they all seem to me to look very much alike,) that if I could describe well, I would not take up the time of the reader in an attempt to draw the portrait of Laura Boyd. It must suffice to say, that she was beautiful, and that the elegance and purity of her mind increased the interest which was excited in her favor by her personal charms.

Edward Melbourn, when at home during his college vacations, spent much of his time in hunting and fishing with Col. Boyd, and soon became with him a great favorite. The lively conversation and fascinating address of Edward gradually inspired the old gentleman with that fondness for him which is not unfrequently produced in the minds of elderly men for young men who happen to please them. In the

Page 13

mean time an attachment grew up between Edward and Laura Boyd, which resulted in a matrimonial engagement, which Col. Boyd consented should be consummated as soon as Edward should complete his collegiate studies and be admitted to practice in one of the learned professions. In one year from that time he graduated at Princeton College, and was gratified by having conferred on him the highest honors of his class. Upon leaving college he returned to Raleigh, and lingered there nearly the whole of the following year, enjoying the society of his mother and Col. Boyd, and fascinated by the charms of the lovely daughter. Roused, at length, by the consideration that his time was wasting away, and that before he could settle in life he must acquire a knowledge of a profession, he tore himself from these interesting and beloved friends, and went to Charleston in South Carolina, where he commenced the study of law, in the office and under the direction of Mr. Desausseaur, an eminent lawyer, who has since held, with distinguished reputation, a high judicial station in that state.

Young Melbourn remained in Mr. Desausseaur's office until he completed his professional studies; but on the day of his examination, at a convivial dinner-party, an altercation between him and a fellow-student occurred, which resulted in a challenge to a duel, and in the combat which ensued Edward was unfortunately slain. The news of this sad catastrophe reached Mrs. Melbourn on the very day he was expected home.

He had written to his mother that he should arrive at home on the first day of November. The evening of that day Colonel Boyd and his daughter called on Mrs. Melbourn; he was in high spirits, and felicitated himself on the agreeable surprise Edward would experience on seeing the improvements he had made the preceding summer, in his mansion-house, his garden, &c., and the addition he had made to his pack of hounds. Laura was silent, but her fine blue eyes

Page 14

spoke hope and joy. It was one of the fine moonlight evenings of a Southern autumn. I do not believe the celebrated blue skies of Italy excel in beauty that of the Carolinas. Mrs. Melbourn invited her visiters to take a walk on the lawn connected with the garden. She seemed almost gay, and as she viewed the scene before her, she repeated in a low voice to Laura, those beautiful lines of Milton--

"These are thy glorious works, Parent of good! Almighty,

This thine universal frame, thus wondrous fair,

Thyself how wondrous then--unspeakable!"

While the party were thus happy on the green, I heard a knock at the front door, and hastened to open it. A stranger was standing there who inquired for Mrs. Melbourn. I answered she was at home and I would call her. With evident marks of agitation he inquired if she had company. I replied a neighboring gentleman and his daughter were with her. "I pray you," said the stranger, "not to think me impertinent, but for particular reasons beg you to tell me the name of the gentleman." I was surprised at his request, but more at his manner, which was embarrassed and confused. Upon learning that it was Colonel Boyd, he requested that the colonel might be informed a gentleman wished to speak with him. The colonel, on receiving the message, immediately came into the house, and saluted the gentleman, who was still standing at the door. They stepped a few paces aside, and conversed together in a low voice for the space of two or three minutes. Colonel Boyd then turned, with a face pale as death, and I heard him say: "I cannot; upon my soul I cannot tell her this dreadful news." The thought like a flash of lightning came into my mind that Edward was dead. Colonel Boyd, however, in a moment seemed to be more calm and collected, and walked into the garden with the stranger, whom he introduced to Mrs. Melbourn. "Mr. Warren," said he, in a solemn voice, "brings sad news from

Page 15

Edward." "Merciful God!" said my mistress, "what of my son?" The stranger hesitated, and Colonel Boyd stood silent and immoveable as a block of marble. Mrs. Melbourn clasped her hands in deep agony. "He is dead," said she, "and you dare not tell me!" They continued silent. My mistress fell back on a seat which was near her. In the mean time, Laura, of whom no notice had been taken, fell prostrate on the ground; her father sprang to her and raised her up in his arms. She was apparently lifeless. I ran for water and gave it to her father, but it was some time before she manifested any signs of life. My mistress was still seated, but she seemed like a statue; her eyes appeared glazed and immoveable. I knelt before her, took one of her hands, and implored her to speak to me. I reminded her that afflictions were ordered by a kind Providence for wise purposes, and entreated her, in this sudden and unspeakable calamity, to look to Him, who, I had often heard her say, would never leave nor forsake us. A flood of tears came to her relief. I said, "My dear mistress, your grief and the cause of it is great, but do not despair. God is just. There must be consolation, there must be good days yet in store for so good, so benevolent, so holy a being as you are." "Never--never on earth," said she, "my last prop, my only earthly hope is gone, and I must look for quiet in the grave, and comfort only in heaven."

I was myself deeply affected by the distress of this amiable and excellent woman. Besides, the death of Edward was to me like the untimely loss of an elder brother tenderly beloved; and my own private grief was rendered more poignant when I afterwards learned that the cause of the fatal encounter was, that Edward's antagonist reproached him with the conduct of his mother, for bringing me up and educating me as a gentleman, who was born a slave.

Mrs. Melbourn for a long time after the death of her son seemed prostrated by the affliction. Her grief, though silent,

Page 16

was profound, and her health seemed sinking under her distress of mind. I much feared that her corporeal powers were too feeble to resist the shock; indeed I think she would have sunk under it, had it not been for the consolations of religion, and her firm, unshaken faith that her heavenly Father would in the end order all things for the best and for the greatest good. Her faith and resignation to the will of God were greatly assisted by the advice and exhortations of Mr. Smith, a methodist preacher, a native of Virginia, who spent much of his time at our house, and who was not only a zealous Christian but a very judicious and discreet man.

Colonel Boyd felt the death of Edward as an affliction the most painful. This young man had become connected with all his plans for the future enjoyment of life. His untimely death had disconcerted all those schemes, and had left the old veteran depressed with a feeling of utter and gloomy solitude. He often said he felt that he resembled a dry tree standing alone in the field, exposed to be prostrated by every gust of wind. The deep and corroding melancholy of Laura added to the Colonel's depression of spirits, and his anxiety was increased by the apprehension that her constitution was incapable of sustaining her against the sea of troubles with which she was overwhelmed. Laura perceived the anxiety of her father, and became alarmed at his condition. She justly suspected that much of his depression was owing to his solicitude for her, and, with the hope of saving the life of her father, she endeavored to appear to forget the death of her lover. Time and these laudable efforts gradually mellowed the grief of the one, and diminished the gloom and despondency of the other.

In the mean while I pursued my studies of general literature; and three years more passed away without the occurrence of any incident worth relating.

In the winter of 1806, the good Mrs. Melbourn procured the consent of the proper authorities, and the deed for my

Page 17

emancipation was duly executed by her. She did this, as I afterwards learned, to guard against any legal objection which might be raised, after her death, against the provisions contained in her will for my emancipation; and because Mr. Smith had suggested to her, that by the law of North Carolina I was, while a slave, personal property--that is to say, a mere thing--and would be adjudged incapable of taking by bequest or devise any property she might think proper to bequeath to me.

During the three years last mentioned, Mrs. Melbourn sent me frequently with messages to Laura Boyd and her father. In the course of these visits I became acquainted with a mulatto girl by the name of Maria, a slave of Colonel Boyd, whom he had given to his daughter as a dressing-maid. Maria was born the property of Colonel Boyd, and in his house. Her mother was a favorite house-slave; she did not live long after the birth of Maria, who was her only child. Maria had been tenderly brought up, and taught to read and write, and the use of the needle.

Her mother, though a slave, was a quadroon, and her father was a white man. Maria therefore was allied to the African race only in the eighth degree. I hardly need mention that the difference in appearance between her and those of pure Saxon blood was so slight as to be almost imperceptible. Indeed it was quite so to an ordinary observer. Yet she was a slave--a thing--an article of merchandise!--by the laws of the free, democratic state of North Carolina!! She was about fifteen years old when I first became acquainted with her.

I am aware that many persons in America, some of whom perhaps may honor me with a perusal of this history of my life, may feel disgusted and indignant at an attempt to describe a female who was tainted with African blood, as beautiful. But nevertheless I am sure there are those, both in England and the United States, who claim to be competent judges, who admit that the most beautiful human forms they ever saw were mulatto

Page 18

girls, and especially those of Richmond, Va. That Maria was one of this description, all who ever saw her admitted. Her tall, erect figure, her sparkling eye, her polished high fore-head, the intellectual, the kind and affectionate expression of her countenance, her graceful movements, and enchanting smile, were to me irresistibly fascinating. I first admired her for the charms of her person, but as my acquaintance and my intimacy with her advanced, I loved her for the qualities of her heart and the superiority of her mind. Maria could not, and indeed did not, have any consciousness of her condition as a slave. She knew, it is true, that she belonged to Laura Boyd, but her situation with that young lady was the precise situation she would have chosen, if the whole world had been open to her choice. She was, practically, as free as the mountain deer. Laura required no more of her than she would have done had her actions depended entirely on her own volition, and indeed she was wholly unconscious of doing any thing or remaining anywhere by compulsion. In the fall of 1807, I communicated my feelings and wishes to Maria, who, being a slave, of course had no acquaintance with educated and well-bred men, and her own education and taste prevented her from the least association with the slaves or the free colored young men in the neighborhood. The manners of this latter class were rude and vulgar, and most of them were licentious and vicious in their habits. I was the only civil male person, except the venerable Colonel Boyd, with whom Maria had ever conversed, and therefore she was pleased with me.

When I made known my attachment to her, she heard me with cordial delight, and confessed her heart had long been mine. She said she would ask her mistress to consent to her marriage with me. "But," said Maria, hesitating, "what if she or my old master should refuse?" A livid paleness overspread her cheek, and apparently, for the first time in her life, poor Maria felt that she was not her own. Now, for the

Page 19

first time, the degradation and misery of slavery presented themselves to her disturbed and agitated mind. After a moment's silence she added, "But they are too good, too kind--I am sure they will not refuse."

In fact, Maria did not over-estimate the kindness of Colonel Boyd and her mistress; they readily granted their consent, but insisted that the marriage should be postponed until I should be twenty-one years of age. This was but reasonable, and, although sorely against my inclination, I was fain to acquiesce in this decision, mainly, I confess, because I saw no way of successfully resisting it. I was then seventeen years old.

From this time I was a frequent visiter at Colonel Boyd's, and I was uniformly kindly received by that gentleman and his amiable daughter, and treated, notwithstanding my African blood, more like a relative of the family than a servant of a neighboring friend. The countenance of Maria always brightened at my approach, and, when with her, I forgot every other human being. Thus passed two of the happiest years of my life. Alas, those blissful days passed rapidly away, to be succeeded by years of suffering and misery. I perceived with deep regret and painful apprehension that the health of Mrs. Melbourn was gradually declining. The fervor of her piety increased, but the wound produced by the death of her son, instead of being healed by time, was cankering and corroding her heart's core. Although endued with holy resignation and heavenly hope, her nervous system was too susceptible to endure the sight of an article of clothing that had been worn by Edward, or even a book which he had been fond of reading.

In the summer of 1809, a young gentleman from Norfolk, Virginia, by the name of Alexander St. John, stopped a few days at Raleigh and paid a visit to Colonel Boyd. His father was a man of wealth and respectability, and, with Colonel Boyd, during the Revolution had served in the army of General Washington,

Page 20

and were both personally known and highly esteemed by that great and good man. After the termination of the Revolution, Colonel Boyd and Major St. John still continued their friendly intercourse, and their friendship increased with their age. This intimacy afforded them the greater pleasure as they belonged to the same political party, both being Federalists of the old school. In the preceding autumn Major St. John had died suddenly, leaving the whole of his large estate to Alexander, his only surviving child.

Colonel Boyd received the visit from the son of his old friend with great pleasure, and at his persuasion, Mr. St. John was induced to remain longer in our neighborhood than he had originally intended. He at times showed some traits of libertinism in his character, and talked more about games and horseracing than was agreeable to Colonel Boyd, who, speaking of him to Laura in my presence, after expressing his dislike to those little foibles, as he called them, said his dislike was perhaps occasioned by the circumstance that he had become old and had lost a relish for pleasures which might have charmed him when young. "That may be so," said Laura, "but I am sure my father was never charmed with vicious pleasures." "I do not think," said her father, more gravely, "that an indulgence in vice, either by young or old, deserves the name of pleasure." "I wish all the world were of your opinion," said Laura. "There is certainly a great difference," continued she, after a short pause, "between Mr. St. John and"--she sighed--"many of our North Carolina young gentlemen."

Alexander St. John had been brought up as a rich man's son, and was in fact a spoiled child. His father had made liberal provision for his education, but he, by one excuse and another, avoided any serious application to study, and like most young men of fortune at that day, in Virginia, had imbibed a hearty contempt for the learned professions, and indeed for all classes of business men. From habit and taste

Page 21

he had become fond of horseracing, gambling, and at times a very free indulgence in drinking. Although he liked rows and was sometimes engaged in brawls, he was considered what was denominated a clever fellow. He was very tenacious of the word called honor, and was ready at all times to gamble, drink, laugh, or fight with you.

This young man professed a violent attachment to Laura, and solicited the consent of her father to pay his addresses to her. Laura learned the proposal with pain and regret; the more so, because she perceived her father was inclined to favor the wishes of Mr. St. John. She knew he would on no account urge her to do an act entirely contrary to her inclination; his only object was her happiness, and that very knowledge rendered her extremely unwilling to refuse her consent. But in the whole deportment of Mr. St. John she thought she discovered a total disregard to religion and virtue, an air of libertinism, and a careless assurance nearly amounting to impudence, very revolting to her feelings. She confessed these impressions to her father, which he heard with regret. He replied, that she was the only treasure left to him on earth; that on her happiness depended his own; he knew she had once loved an object worthy of her, but he was no more: would it be in accordance with her duty towards society, would it be wise to bury herself at her age? Mr. St. John belonged to a family of great respectability, of unstained honor, and large estate. The latter circumstance he cared little about, as had been proved to Laura on another occasion, but it was a circumstance which ought to have some weight in deciding upon Mr. St. John's proposal, because an increase of wealth would enable them to be more useful to their fellow-beings. "You are already," said he, "near the end of the spring-time of life, and, my dear child, I will confess to you that I am unwilling that my family should end with you and me." Here his voice trembled, and Laura perceived that he had touched a string which vibrated through

Page 22

his heart. She was much distressed, and begged her father not to press her further at that time, but to advise Mr. St. John to return to Virginia, and she would give the subject the consideration which its importance demanded, and which her love and duty to her kind good father required. "Be it so," said he, pressing her hand, "but do not make yourself unhappy to please me."

This last remark sunk deep into the heart of Laura. Could she act contrary to the wishes of her only parent, and that parent so kind, so affectionate? St. John was extremely pressing for a more favorable answer, and not obtaining it, prepared reluctantly to return to Virginia.

Soon after this conversation Mr. St. John made his addresses to Laura, and solicited her hand in marriage. She heard him with deep and painful regret; nevertheless, the ardent solicitude of her father that she should be settled in life finally wrung from her a reluctant consent, but that consent she did not yield until she had consulted Mrs. Melbourn, who earnestly advised her that her duty to society and to her father required her to accede to the proposals of Mr. St. John; and she soon after became his wife.

It was now the latter part of the year 1809; and as the cold weather approached, Mrs. Melbourn, who had been gradually sinking, in consequence of a melancholy which followed the death of her son, and which could not be overcome, was attacked with a cough of a character evidently indicating that her lungs were affected.

It is a singular feature in the disease called consumption, that as the body declines the mind becomes more vigorous, or rather the intellectual vision becomes clearer, and the mental powers glow with greater and greater brilliancy till the lamp of life is extinguished. That was peculiarly the case with Mrs. Melbourn. Indeed, her tone of mind, by which I mean her fortitude, evidently increased as death approached. Although formerly she could not endure the sight of any thing

Page 23

which had belonged to Edward, now she directed his wearing apparel to be brought into her room, and also his letters to be read to her, which she had carefully preserved. She heard them with composure and pleasure. I could see sometimes, when reading those letters which contained ardent expressions of filial affection, a tear start in her eye; but it seemed her main reason for calling for these letters was to prepare her mind for that converse which she hoped soon to enjoy with her beloved child in another world.

One day, and it was less than a week before her death, she called me to her bedside, and motioned to the servants to retire. She said she had but few words to say to me, and these related only to worldly concerns. She wished me to marry Maria, and trusted I would do so. Although both Colonel Boyd and Laura had assured her that Maria should be emancipated at any time when it was thought best, and certainly when she was married to me, the new relations caused by the marriage of Laura to a stranger might produce obstacles not now anticipated, and she had thought it better to provide in her will the means of paying for Maria's freedom, and which Mr. Smith, who was her executor, was authorized to pay to me on my becoming twenty-one years of age. "The principal part of the legacy I intend for you," said she, "is left in the hands of Mr. Smith, as a trustee, until you arrive at the age of twenty-five years."

She died four days after. A great poet has said, that

"The death-bed of the just is yet undrawn

By mortal hand: it merits a divine."

If Mrs. Melbourn in her lifetime exhibited, as in truth she did, the beauties of the Christian religion, her death evidently proved its triumph. She was calm, self-collected, and possessed in full perfection her mental faculties, and her eyes shone with more than usual lustre. In her last moments she took the hand of Mr. Smith; "I knew," said she, "that my

Page 24

Heavenly Father would not forsake me in this hour." Her last words were, "My husband--my Edward--I come!"

"Sweet peace and humble hope and heavenly joy

Divinely beamed on her exalted soul,

And crowned her for the skies with

Incommunicable lustre bright."

After her death and burial Mr. Smith produced her will. She bequeathed an annuity of $100 to each of her English servants. She gave her watch and Bible to Laura; to the Methodist society $1000, to be paid as Mr. Smith should direct; and she bequeathed to me the residue of all her estate, amounting in value, as I afterwards ascertained, to a little more than $20,000. Of this sum Mr. Smith was immediately to pay me $400 to purchase the freedom of Maria, if it should be necessary to pay for her freedom, and a small sum annually for my expenses until I should be twenty-five years old, when the whole amount was to be delivered over to me.

Since the marriage of Mr. St. John with Laura he had claimed the house of Colonel Boyd as his home; and he did, in fact, spend the winter and early part of the spring of 1810 there, but in May he went back to Virginia to superintend, as he said, his estate in the neighborhood of Norfolk. Laura seemed more dejected after her marriage than before; and neither the entreaties of her husband or her father could induce her to mingle in society more than barely to avoid treating with apparent neglect the friends of the family. St. John during the winter had shown some slight indications that he had not abandoned his habits of dissipation, and I thought there appeared a want of cordial good-feeling towards him on the part of Colonel Boyd. When in company with St. John, there was a formality and a constraint in his manner not exactly suited to the relations existing between them. I observed, too, that Maria appeared unhappy, and I sought in vain to learn from her the cause of her uneasiness. I informed

Page 25

Colonel Boyd of Mrs. Melbourn's bequest to purchase her freedom, and wished him to give his consent. He seemed offended at the overture. "He had," he said, "told me she should be free on the day of our marriage, and hoped I did not mean to intimate that I doubted he would perform what he promised." Of course I could not urge him further.

As an excuse for going frequently to the house of Colonel Boyd, I used to carry him his letters regularly from the post-office immediately after the arrival of the mails; and this practice I continued the whole of the autumn of that year. St. John had protracted his stay at Norfolk much longer than was expected. One evening, among the letters, I observed one post-marked Norfolk. Colonel Boyd opened that first: while reading it he appeared greatly agitated, which his daughter perceiving, begged him to acquaint her with the cause. He hesitated a few moments, and then said, "My dear child, I fear we have been deceived in Mr. St. John; at any rate, it appears from this letter, which is from an old friend of mine in Virginia, that his affairs in that state are totally ruined." The letter was brief, but stated in substance, that soon after the death of his father he had indulged quite too freely in dissipation and profuse expenditure; that in less than six months after he came to the possession of his estate, he had mortgaged it for nearly one-third of its value, an act that was for some time kept secret; that during the last summer he had been guilty of gross licentiousness, and had become an associate with the most extravagant and reckless gamblers, who had swindled him out of all his estate, and left him in debt.

Colonel Boyd had the year before been attacked with a slight shock of apoplexy; his daughter was alarmed lest this news would discompose his nerves so as to produce a return of that fearful disease. She therefore said to him cheerfully, "Perhaps it is not so bad as your friend writes; and even if his property is gone, we have enough to live upon. I did not

Page 26

marry Mr. St. John for his money." "No," said her father, "you did not marry him for his money, but you married him because you loved me, and I urged you to it." "Indeed you did not," said she, "you left the matter to my own free will and--" "Mighty God!" said he, heedless of what she said, "that I should urge my dear child to marry a drunkard--a companion of swindlers--" As he said this, he rose suddenly from his seat, clasped his hands, and fell dead on the floor.

The scene was awful. I sprang to the colonel--attempted to raise him--used friction and other means to reanimate him. Alas! it was all in vain: the lamp of life was extinguished forever. Laura was insensible. Maria made every effort to restore her, which in a short time proved successful. What effect was produced upon the tender and affectionate heart of Laura by the sudden death of her only parent, can be better imagined than described. Her grief was silent, but it was most intense. The mind which is capable of overcoming one great misfortune--the heart which has been once lacerated by deep wounds, and whose dearest hopes have been crushed--if capable, by the strength of reason, to triumph and ride out the storm, acquires additional strength to encounter other and equally severe afflictions. The mind, though it may retain its sensibilities, acquires not exactly rigidity, but a tone which increases its capability to resist prostration on account of subsequent disappointments and grief: the flesh that becomes callous after a wound, will be less affected by a blow than that which has never been injured. So it was with Laura: she had survived the destruction of her fondest hopes in the death of her beloved Edward, and that experience encouraged her to hope, that time, and an humble resignation to the dispensations of a Divine Providence, would enable her to outlive the loss of her father.

Colonel Boyd died without a will. From that reluctance

Page 27

which all feel, while in health, to sit in judgment upon their own affairs after death, and make a final disposition of their property, he had from time to time, and from various causes, (most of which were merely pretences, which his unwillingness to engage in the business of making a will had conjured up,) put it off; although, on the very day of his death, he told Laura that he should go to town the next day for the purpose of having his will drawn; that he was admonished by the paralytic shock he experienced about a year before, that he might die suddenly; that he was alarmed at the habits and propensities he discovered in St. John, and that he meant to vest his estate in the hands of trustees for the benefit of his daughter, to be subject to her control. An inscrutable Providence defeated these prudential calculations and arrangements.

A special message was immediately dispatched for Mr. St. John, but he did not arrive at Raleigh until the day after the funeral. He had not been at home many days before he assumed the absolute control of the property of Colonel Boyd, all of which, both real and personal, he claimed in right of his wife as sole heiress. He put on new airs, and, indeed, seemed a different kind of man. He sold a considerable number of the slaves to raise money to pay off the balance of debts still existing against him in Virginia. A great part of his time was spent at political meetings and horse-races, or carousing at a hotel in Raleigh; and when at home, he was ill-natured and cruel to the slaves, and sullen and sulky at his own fireside. Thus it was that Laura, while overwhelmed with grief at her father's death, was distressed with the painful conviction that her husband, in whose absolute power the laws of the land placed her and her great estate--was becoming, if he had not already become, profligate in his principles and habits, and tyrannical and brutal in his character. His treatment of me was haughty and offensive, and he even intimated a wish that I would not visit at

Page 28

his house. Maria seemed more distressed than any other member of the family. Mr. St. John's entrance would constantly throw her into a tremor: the sound of his voice, or even the noise of his steps, would make her bosom throb with fear. As soon as I could speak with her alone, I reminded her of the agitation she had on several occasions manifested in presence of Mr. St. John, and entreated her to inform me of the cause of it,--which she declined doing. I told her that if her situation was in any respect painful, I would have her removed to some other place. "Alas!" said she, "there are two things which render such a step impossible. In the first place, she was the property of Mr. St. John, and therefore could not leave without his consent; and if he would yield such consent, she herself could not leave her mistress in her present condition." I replied that there was money in the hands of Mr. Smith to purchase her freedom, and that, at all events, should be done immediately. "Julius," said she, with a deep sigh, "I fear Mr. St. John will refuse to sell me." Like a flash of light, it came into my mind that St. John cherished improper designs in relation to her. The horrid idea entered my soul like a barbed arrow. I said no more, but hastened to Mr. Smith, and communicated to him my apprehensions, and begged him immediately to apply to St. John for the purchase of Maria. He did so the next morning, and met with a prompt and peremptory refusal to sell her on any terms. In vain Mr. Smith represented the solemn engagement of Colonel Boyd, that he would set her free without money and without price; and that, at a proper time, she was to become my wife. The excuse rendered by Mr. St. John was, that the attendance of Maria on Mrs. St. John was indispensable. Having stated this, he immediately left the room. Mr. Smith then requested to see Mrs. St. John, and explained to her the nature of his business with her husband. Mrs. St. John said it was the intention of her father that Maria should be freed, which perfectly accorded

Page 29

with her own wishes; that she would speak to her husband on the subject, and she did not doubt he would consent that Maria, whenever she chose, should leave the family. The next day, Mr. Smith and myself called, and found Laura indisposed. She appeared to have been weeping. Maria was not in the room. Laura said she had been disappointed: she had been unable to persuade Mr. St. John to liberate Maria; she hoped, however, on reflection, he would be better disposed. St. John was then in the field, and we concluded to wait his return to the house. On his entrance into the room, Mr. Smith immediately rose and said to him, that it gave him great pleasure to learn that Mrs. St. John did not object to the discharge of Maria, which, from what passed yesterday, he trusted would remove the objection of Mr. St. John; and he added, that if the price was any object, he would, on his own responsibility, double the sum left by Mrs. Melbourn for the purchase of the freedom of Maria. St. John's eyes flashed with rage and fury. "Am I," said he, "to sell my slave at the dictation of a fanatical old woman? You and your whole Methodist gang may go to the d--, with this fellow Julius, whom you have pampered to cut our throats. I will not, for all the wealth of your tribe, sell this girl,--by heavens, I will not!" Mr. Smith endeavored to calm him, and finally insisted that St. John was under a moral obligation to carry into effect the intention of Colonel Boyd. This increased his rage. "You scoundrel!" said he, "have I not a right to do what I please with my own property? Rascal! do you claim to direct me what I shall sell, or what I shall keep? There stands my roan mare--perhaps in your next sermon you will exhort me to sell her. Out of my house, and never let me see you here again." We left the house, and the next day I received the following note from Maria:

Page 30

"MY DEAR FRIEND,

"I am very unhappy. I cannot, dare not, explain to you the cause. My poor mistress is very sick. She cannot write; if she could, I would never consent to write what I do now. My mistress says we must be married right away. I hope you will not think me too bold for writing this. I would not for the world have done so had not my kind, good mistress told me I must. She says Mr. St. John is going to the horserace to-morrow, and that you must come and bring with you Mr. Parker, the church minister, as she thinks Mr. St. John will not find so much fault with him for doing it as he would with Mr. Smith, because he is a Methodist and Mr. Parker is a Churchman. I am afraid you will think ill of me for writing this, but then I think there is something in your heart that will make you forgive your own distracted but true-hearted

"MARIA."

I cannot express the joy with which I read over this artless letter. I loved Maria with an affection the most ardent. This passion was not excited by her beauty, but by the purity of her mind, and the strength of her affection for me. It is said that "pity moves the soul to love;" and her unprotected, distressed, and forlorn situation as a slave, and--may I add, without offending the delicacy of the reader?--her taint with despised African blood, increased my sympathy and affection.

I communicated the letter to Mr. Smith, who with me called on Mr. Parker, and stated the case fully to him, and he entirely approved of the measure. He went the next afternoon with me to the house, and we found Mrs. St. John on her bed. I lost no time in expressing the deep sense of gratitude I felt for what she had done. She said there was no time for conversation, for Mr. St. John's mare, which he intended for the race, was found that morning to be a little

Page 31

lame, and it was possible, and even probable, that he might return without going to the race-ground. We therefore immediately prepared for the ceremony, but just as Mr. Parker was about to commence, Mr. St. John entered the room. He instantly perceived what was going on, and forbid the marriage; ordered Mr. Parker and me to leave the house, and seized hold of Maria. Involuntarily I laid my hand on my dagger, which I then carried in my bosom. May God forgive me, but at that moment my soul thirsted for blood. At that instant Mrs. St. John rose from her bed; the fire of Colonel Boyd's eye flashed from that of his retiring and mild daughter. "I command you," said she to Mr. Parker, "to proceed. That man has no right to interfere. The girl is mine, and I will dispose of her. What mean you," said she, addressing St. John, "by thus insulting the honor and the memory of my father? My lands and goods you have; I do not complain. Have you the meanness to claim the control of my own maid? You cannot, shall not do it. I will carry out the intention of my father at the sacrifice of my life." St. John was struck dumb with surprise; he had never before seen any thing in his wife but the most quiet submission; for the moment he was overawed. He felt "how awful virtue was," and shrunk from the frown of outraged innocence. She turned to Mr. Parker, and said, with calmness, but with that true dignity which conscious rectitude and the triumph of virtue always inspires, "Proceed, sir, with the ceremony." He did so; but the moment he pronounced us man and wife, Mrs. St. John fell apparently lifeless on the sofa.

She, however, soon recovered, and though she continued ill for several months, the succeeding winter she in a great measure regained her usual state of health, which had never been good since the shock she experienced upon hearing of the death of Edward.

After Maria became my wife, I continually urged her to

Page 32

disclose to me the reason why she for a long time past had been, and still appeared to be distressed in the presence of St. John, and she finally consented to explain the matter to me on the express condition that I would promise not to attempt to avenge any wrongs or injuries to which she had been subjected; and to this condition I consented.

She then related to me, in detail, the persecutions she had suffered from St. John, which commenced soon after his marriage with Laura Boyd; his flatteries, his threats, and finally his attempt at force, when fortunately she was relieved by the accidental and unexpected appearance of Mrs. St. John. Maria concluded by saying, that she wrote me the note requesting me to come and marry her by the express command of her mistress.

While listening to Maria's relation, I became highly indignant, and when she concluded, I trembled with rage. I grasped my dagger, and my first thought was to seek out the monster, and stab him to the heart. Maria checked me. She pointed out the criminality of such an act. She urged the certain ruin to myself as well as her which would inevitably follow, and reminded me of my solemn promise that I would not take revenge;--and her expostulations had the effect she intended.

The condition of the male slave one would suppose was the extreme of wretchedness, but that of the female is still worse. For a female to be the PROPERTY of an unscrupulous, sensual, and profligate man, how horrible! Well might Maria say, as she did say to me on this occasion, "How could the poor slave endure life were it not for her belief in a benevolent and just God, and in 'another and a better world?' "

I went home, and wrote St. John the following note:

SIR--

Maria has told me all, but on the condition that I would promise not to avenge her wrongs. Vile as you are, I shall keep

Page 33

that promise. But remember--ay, REMEMBER--that if you again abuse her with your beastly attempts, as sure as there is a God in heaven, be the consequence to me what it may, you are a dead man.

I am, &c.

JULIUS MELBOURN.

A. ST. JOHN, Esq.

Some persons may think it extraordinary that on the receipt of my letter St. John did not complain to the police officers and cause me to be arrested; but he knew I had powerful friends in Raleigh--he knew I could command money, and he considered that he could not make the complaint without disclosing his own infamy, and drawing down upon himself the vengeance of the friends of his wife. He was alarmed; for from his knowledge of me he was well convinced that if he persisted in his nefarious course, I should execute my threats.

True courage is based upon virtue. The paroxysms of a madman and the blustering of the inebriate have no affinity with real fortitude. Hence the sordid knave and the profligate villain are generally cowards. St. John therefore from that time entirely ceased making those attempts upon Maria, but treated her afterwards in a most inhuman and tyrannical manner. Her body was frequently lacerated by wounds inflicted by the blows of this monster, but this she carefully concealed from me and Mrs. St. John.

The events last related occurred in the autumn of the year 1811, and it will be recollected that I became twenty-one years old on the fourth day of July in that year. During the winter and following summer St. John became more and more dissipated and irregular in his conduct, while his unfortunate wife, feeble in health and depressed in spirits, seemed barely to support a painful existence. Maria was her only companion. St. John was absent most of the time, a considerable part of which he spent in Baltimore and New

Page 34

York. I made several attempts through agents (for I knew a personal application was sure to be refused) to purchase Maria's freedom; but to all such applications he gave a peremptory refusal even to treat on the subject. This state of things produced in my mind extreme pain, which was greatly heightened and rendered almost intolerable by Maria's giving birth to a son, who, according to the laws of North Carolina, was the slave of Alexander St. John. Strange law! I was worth at least $20,000 and yet my innocent child, born in lawful wedlock, was the property, the goods and chattel of my most inveterate enemy, who, if I were to offer him a million of money, would be justified, by the laws of the land, in retaining my child in bondage. And yet North Carolina claims to be a Christian, a democratic state, and inscribes on her banner, Equal Rights, as her favorite motto! I invoke the attention, not of the slaveholder, for he is incorrigibly insensible, but of the civilized world to this great fact, so damning to the reputation of the slaveholding democratic states of the great American Union. There was, however, one consideration which afforded me some hope. St. John was rapidly involving himself in debt, and perhaps the pressure on him for money might before long induce him to sell, for a round sum, I cared not how exorbitant, my wife and child. In the spring of 1814, St. John determined he would spend a part of the ensuing summer at Saratoga Springs, New York. He now found himself sadly pinched for money; his creditors too were very pressing; his debts, which had been chiefly incurred at the gambling table and for bets on horseracing, were of such a character as he was bound to pay promptly, or lose caste among his associates. It therefore became necessary for him to raise by a loan a large sum of money.

There was a man in Raleigh by the name of Return Jonathan Fairport, who was a dealer in money, and generally called a broker, though in truth the appellation of shaver would have been more appropriate for him than the honorable

Page 35

name of broker. Mr. Fairport was a native of Lynn, Massachusetts, and some ten years before had introduced himself at the South as a pedler of wooden clocks and sundry articles of tinware. In that business he was very successful, and in a few years had cleared to himself some four or five thousand dollars in ready cash, with which he commenced operating by purchasing notes and small bonds and mortgages, and by accommodating the young Southern gentlemen with loans in the winter season, to be repaid after the next tobacco harvest, with from 25 to 50 per cent. interest. In this way, by the aid of Mr. Grip, a lawyer in Raleigh, he increased the amount of his funds with astonishing rapidity. During the war with Great Britain the difference in exchange between the South and North became very considerable, and before its close rose to 20 per cent.; and Mr. Fairport having established a credit at Boston, and a pretty good understanding with the managers of the general post-office at Washington, his gains were enormous.

Mr. Fairport was a little under the usual size, miserably emaciated, with a long chin, sharp pointed nose, small gray eyes, sunk very deep into his head, a cadaverous complexion, and a most grave and melancholy countenance. He was a religious man, and a member of the Presbyterian church of his native town, and held strictly to the Saybrook Platform.

Mr. St. John had for some time been in the practice of borrowing small sums of money of Return Jonathan Fairport. On the present occasion he called upon him and told him he wanted to borrow a large sum. "Lack-a-day," said Jonathan, "I am just at this time hard up. I have not one hundred dollars at command. Where in the world can I get a thousand dollars? I am this moment racking my brains to meet a draft from Boston of $500." "Pooh!" said St. John, "I understand your tricks, brother Jonathan; you need not attempt to play them on me. I know you can command any sum you choose. Don't talk to me of one thousand dollars,

Page 36

I want at least fifteen thousand!" Fairport raised his hands and gazed at St. John with astonishment. "Fifteen thousand," said he, "I could not, to save the nation, raise five thousand." "D--n it," said St. John, "let me hear no more of this; you know that I know what you say is false." "What has Major St. John seen of me," replied Fairport, meekly, "which causes him to charge me with falsehood? truly he knows I am a conscientious man." "Ay, that I do, and that you are a pious go-to-meeting man; but," said St. John, in a low voice, "give me $15,000, and I will give you my bond for $18,000, payable next new-year's day, with interest; what say you to that St. Jonathan?" Mr. Fairport looked intently on a mortgage that lay before him for a moment, then clapping his hand on his forehead, said: "A thought has struck me, which may perhaps lead to your accommodation. There is no man in the state I would sooner oblige than yourself. You must need the money very much, or you would not make so liberal an offer: now a friend of mine in Salem, in the old Bay State, writes me to invest some money for him, and has authorized me to draw on him for a considerable amount. I will venture to make the loan on these conditions: you shall pay 15 per cent., which is the usual price for a draft on Boston, and give me a judgment bond to secure the payment of the money. If the money was mine, I know your standing so well, and have such confidence in your honor, that I would not of course ask any security, but my friend positively forbids my lending his money without security." "Have you the impudence to ask security of me, Mr. Fairport? I will pay the premium for the draft, and give you my bond for the money; but as for giving you a judgment as security, you may go to h-- for it." "Very well, as you please, Major; I must follow my instructions." St. John left the office in a great rage; but, as Fairport evidently foresaw, in a few minutes he came back and agreed to give the judgment. They went out immediately

Page 37

to Mr. Grip's office, where the bond and warrant of attorney was executed, and the money paid. St. John left Raleigh about the middle of June, in the southern flash style of that day: he took with him two slaves, an elegant pair of bay horses, which he drove tandem, and a splendid gig, manufactured in Boston, and which he had purchased at an exorbitant price of Fairport. To Maria and myself, and indeed I may say to his own wife, his departure afforded sincere pleasure. Every thing at the old mansion of Colonel Boyd was now quiet and peaceful; even the countenance of the field-slave was lighted up with animation and joy. But alas! the physical powers of Laura were fatally impaired: nothing could revive her, or restore to her eye its lustre or the bloom to her cheek. In vain did she try to enliven her spirits by conversation with Maria, or amuse herself with the infantile developments of her child. Her mind as well as her corporeal powers continued, in spite of all the efforts of my wife, myself, and all her domestic servants, to be more and more oppressed.

In the month of August Mr. Smith received a letter from the treasurer of Princeton College, stating that upon examining the accounts of that institution, a charge had been found against Edward Melbourn for one quarter's board and incidentals, which by mistake had not been settled when he left that Institution: the treasurer therefore requested Mr. Smith's attention to the claim. Mr. Smith consulted with me about it; and as we doubted whether the accountant of the College had not himself committed an error, knowing as we did the extreme accuracy with which Edward transacted all his pecuniary affairs, and as it was difficult at that time to transmit with safety drafts for money from one part of the country to another, it was concluded that I should make a journey to Princeton and settle the claim. I therefore lost no time in preparing for the journey, and anticipated much pleasure in viewing Philadelphia and New York, those great cities of

Page 38

which I had heard so much, as well as that ancient and venerable seat of science, Princeton College. For this reason I made preparations for the journey with the ardor and vivacity of a boy; but when the morning arrived on which I was to leave home, and was about to bid farewell to my wife and child, a melancholy presentiment suddenly oppressed my mind; and as I held them to my heart, a chill of horror seized me, which was then as now, to me unaccountable. I felt that I was bidding farewell, perhaps a last farewell, to all that was dear to me on earth. There are probably few persons who have not some time in their lives experienced similar sensations; and the kind of sensations which are remembered, generally prove to be presages of evil. It may be that we remember only those evil forebodings which happen afterwards to be realized; or it may be "there is a divinity that stirs within us," which warns us of approaching suffering and danger. I am neither a believer in witchcraft nor prodigies, yet with the scholar Horatio I do believe "there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in our philosophy." Maria perceived the depression of my spirits, and endeavored to cheer me; but notwithstanding the lively airs which she assumed, I saw that something lay heavy at her heart. After leaving the door she called me back to repeat to me that she should expect me in three weeks at farthest. But my absence was prolonged; for on arriving at Princeton, the treasurer was gone on a journey to Massachusetts, and I was obliged to wait his return.

On the evening that my business was closed with the treasurer of the college, a servant at the hotel brought me a letter which by the superscription I knew to be from Maria, and hastily opening it, read the following words, which were written in so much haste that they were scarcely legible.

Page 39

"September 1.

"DEAR HUSBAND,

"Come home immediately; my dear mistress is dead; I am sold, and to-morrow shall be carried to New Orleans. Mr. Parker will tell you where our little Edward is; I dare not write about it. This letter may be broken open, and may never reach you. I shall never see you more, but I can die contented if Edward gets into your hands. Adieu, forever! May our Heavenly Father take care of you.

"MARIA MELBOURN."

While reading these lines my brain seemed to whirl like a top: for a moment my sight failed. I knew not what I did. I called for the landlord, and told him he must send me to Philadelphia that night; but while yet speaking with him, the mail-stage came to the door. I instantly paid my bill, mounted on the driver's seat, and urged him to drive with all possible speed. I stopped neither to sleep nor eat until after my arrival in Raleigh. I heard vague rumors, on the way, of the failure of Mr. St. John, of the sale of his property, and the death of his wife. On arriving at Raleigh, I immediately ran to the Rev. Mr. Parker, because Maria had referred me to him, and Mr. Smith was then absent on a mission in the State of Missouri, having left home four or five weeks before, and was not expected to return until the next December. Mr. Parker was fortunately in his study, and he immediately informed me of the distressing events which had occurred in my absence.

About the 20th of August, a few days after my departure for the North, Mr. Fairport received news from a Boston correspondent, then at Saratoga, that St. John, upon arriving at Saratoga Springs, had set up a style of living most profusely expensive; that he spent both his days and nights in the wildest scenes of dissipation; and that finally he had fallen in with a gang of notorious swindlers,

Page 40

who at the gaming-table had robbed him of all his money, amounting, as was understood, to several thousand dollars; and that, with a view to retrieve his losses, he had staked his horses, equipage, servants, and even his watch and wearing apparel, and lost all. Upon receiving this intelligence, Fairport lost no time in suing out an execution against St. John, and directed the sheriff to levy and sell all his household furniture, slaves, and other personal property. The sheriff thereupon entered the house, lately the property of Colonel Boyd, and without much ceremony proceeded to seize and make an inventory of every thing he could find there. Mrs. St. John, whose spirits were already crushed by disappointments and grief, enfeebled and worn out with sickness, upon learning that the property of her father was all to be seized and sold for the debts of her unfeeling and worthless husband, sunk under the blow. She was seized with convulsions and died in two days. Maria never left the room of her beloved mistress, but continued with her to the last, and followed her remains to the grave. A few moments before Laura expired, her senses returned; she called Maria to her, took her hand--"My dear friend," said she, "I am going to join my father and mother;" and she faintly added, "My dear Edward;--do not grieve for me, my only distress is for you. I see nothing but misery before you in this world. I know what they intend to do with you. My last recollections are, a conversation I overheard about you. Oh! these wicked laws of my native State! There is no help--you must seek for comfort in another world--write to your husband--tell him to come quick." She could not finish the sentence, but shortly after breathed a prayer for Maria, and her pure soul took its flight. After the funeral service, which was performed by Mr. Parker, Maria informed him of her situation, and begged his advice and assistance, which he readily promised. She told him that herself and child had been seized by the sheriff, and were to be sold in two days,

Page 41