Narrative of William Hayden,

Containing a Faithful Account of His Travels

for a Number of Years, Whilst a Slave, in the South.

Written by Himself:

Electronic Edition.

Hayden, William, b. 1785

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities and The Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Joby Topper and Natalia Smith

Text encoded by

Lee Ann Morawski and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2001

ca. 340K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) Narrative of William Hayden, Containing a Faithful Account of His Travels for

a Number of Years, Whilst a Slave, in the South. Written by Himself

(spine) Life of Hayden

William Hayden

154 p., ill.

Cincinnati, Ohio.

1846.

Call number E444 .H4 1846

(Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Pages 145-146 are missing in the original.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- African Americans -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Religion.

- Free African Americans -- Biography.

- Hayden, William, b. 1785.

- Slavery -- Kentucky -- History.

- Slavery -- Virginia -- History.

- Slaves -- Biography.

- Slaves' writings, American -- Ohio -- Cincinnati.

- United States -- Description and travel.

Revision History:

- 2001-10-15,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-01-11,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-01-09,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-12-21,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Spine Image]

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

NARRATIVE

OF

WILLIAM HAYDEN,

CONTAINING

A FAITHFUL ACCOUNT OF HIS TRAVELS FOR A

NUMBER OF YEARS, WHILST A SLAVE,

IN THE SOUTH.

WRITTEN BY HIMSELF.

"Party intolerance is despicable; the true spirit of Freedom acknowledges

only the supremacy of GOD, and the RIGHTS OF MAN."

Cincinnati, Ohio.

1846.

Page verso

COPY RIGHT SECURED ACCORDING TO LAW,

IN THE CLERK'S OFFICE, OF OHIO.

PUBLISHED FOR THE AUTHOR.

Page 3

DEDICATION.

TO THE FRIENDS OF MY YOUTH,

WHO, WHEN A POOR SLAVE BOY, TAUGHT ME THE FIRST RUDIMENTS

OF AN ENGLISH EDUCATION, AND TO

THE FRIENDS OF THE SLAVE,

THROUGHOUT THE UNIVERSE, TOGETHER WITH ALL

MOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS,

WHO, THROUGH THE WISDOM OF GOD MAY BE SET APART TO RAISE

AND EDUCATE FAMILIES,

THIS NARRATIVE

IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED.

By their humble servant,

THE AUTHOR.

Cincinnati, O.June 1st, 1846.

Page 4

PREFACE.

In appearing before the public with this brief Narrative, it becomes me, as a duty, to place before that public, some of the principal reasons, which induced me to the writing of it. It is a custom, now-a-days, on assuming the station of an author, to make an obeisance to those, whom the individual looks upon as private and personal friends; and acting under this impulse, I respectfully doff the cap to all, and salute them with a few stray leaves from the Diary of my travels through the Southern States, with the Slave Traders.

When first induced to pen this short narrative, I was but a mere boy--a slave--untutored, and alone in the world, save some few friends, who stood by me through "thick and thin." But from my infancy, I have been led on by degrees from step to step, by a supernatural Power--its voice has ever been with me--and each and every promise which has been made by it, has invariably been fulfilled. Many may smile in incredulity at this assertion, and consider it as a hallucination of the brain; or as an evidence of supercilious superstition. Well, let them--but I feel fully convinced and encouraged in that belief, from the blessings and knowledge which I daily see spread before me. Nor am I without precedence. We read in times gone by of the Spirit appearing to many of the believers in God. In the case of Mary the spirit of the Lord made manifest the birth of her son, Jesus--to the shepherds, too, were the same tidings delivered, through the voice of a spirit--the spirit also encouraged and converted Saul of Tarsus, as he wended his way on a crusade against the Christians--and even John was blest with a knowledge of the upper Heavens, through a supernatural spirit. Nor can I believe that those days have forever gone. A supernatural something has always forewarned me of approaching events, and endowed me with a knowledge, which has enabled me to weather the storms of forty years servitude and servile slavery, and to come forth from the trials with honor to myself, and honor to my nation. Nor has that spirit yet forsaken me--although an old man--some sixty years of age--it holds daily communion with me, and urges me on to deeds of sympathy and good will towards all men, whilst its sweet consolations repay

Page 5

me an hundred fold, for all the trials I am doomed to undergo. God's name be praised.

I have said that I was forty years a slave. Yes, forty of the best years of my life, were passed in servile bondage to my fellow men. Yet, during that time, the body alone was prostrated in that degraded situation--the mind--the image and the best gift of God to man, was always elevated--it spurned the shackles, and soared to Heaven, where it revelled in Elysium; in blissful concert with its Creator.

Hard as was my fate, in being cast into a state of bondage, in witnessing the insult, the degradation--the licenstiousness, and the abuse, which the slave-traders heaped upon the unprotected slaves--yet, I stood firm--unshrinking to the commands of mortal--and centred my every thought upon a higher and a holier power. The body may be debased to purposes, at which the brute creation would shudder--it may be made an instrument in the hands of man to prosecute the most damning crimes--but the soul--the immaterial man--the thought--the mind, can never be chained. It belongs to a higher sphere, and ruled by a higher Being, in whose hands are held the whirlwind and the storm,--the existence and non-existence of all the human family. What cause had I then to fear? My heart laved in the waters of Salvation, and my Guardian Spirits stood forth as beacon lights, pointing the road to freedom and to happiness. I felt that this was the case with me, and I determined that "sink or swim," I would persevere in obedience until the goal was won--and the joyful shout of deliverance and bliss, echoed through the valley.

Mankind should ever bow to the power which rules and sustains him. But that power is not vested in mortal hands--it is coeval with Deity itself, and will ever be exercised with rigid justice by an almighty God. Nor will he permit his creatures to suffer--for he has promised that those who put their trust in Him, shall pass the fiery ordeal of the world, unscathed, and unharmed. To Him, then, must I offer up my prayers for my safe deliverance from all the ills which beseige me during my pilgrimage on Earth.

To some, this may seem as a wild and unfeasable theory--void of common sense in a practical point of view, but it is as true, and unchangeable, as that God exists in His might and power, and will one day come to judge the world in righteousness and justice. Why should I not put my trust in God? I am now sixty years of age

Page 6

and by His power alone, I have been sustained and upheld, and by His power alone, I have passed through trials and temptations at which the stoutest heart would quail. He has borne me through them all--He has raised me up friends in every part of the world in which I have sojourned, and He has brought me out purified and sanctified of the sins of the world--and all connexion with the evil one. How, then, can I turn a deaf ear to his commandments--and turn aside from the path which He has pointed out to me, wherein to go? Were an earthly friend to do this--were he to extend over me the arm of his protection, during the reign of trial and vexation--were he to shield and protect me in health and in sickness, what would be thought of me by the world, if I should turn aside, and denounce and condemn him as a vain, inconsistent, and ambitious personage? Would they award to me the feelings of common humanity and respect? or, would they place any confidence in the sincerity of any profession I might thereafter make or endeavor to place before a discriminating public? No--most assuredly they would not. I would be looked upon as an ingrate--a wretch, whose feelings were seared in the heated cauldrons of base inhumanity, and corruption.

If the world would then look upon me thus--would treat me as a desperado of the deepest dye; what should I expect from an almighty parent who had sustained and protected me in every vicissitude of an ill-spent life? who has thrown the shadow of his protecting wings over me in health--and upheld me with His might and goodness when death overshadowed my couch, and laid the cold impress of his rigid seal almost upon my brow? What, I say, should be the feelings of a Righteous God, who had endowed me with talent--with understanding, and with a knowledge of good and evil, were I thus knowingly to transcend His commands--to turn ingrate upon His hands, and to say to Him by my actions,--"I am aware that you have been a kind and indulgent benefactor to me through life--but I feel that I am now beyond the influence of sickness, disease, or want, and I ask not your further aid?" Could I reasonably suppose that he would pass by such actions, and not stretch forth his "red, right arm" of vengeance; and smite His ungrateful and blasphemous creature to the earth? No! His vengeance most assuredly would fall upon me, and with such an effect that language would fail to draw the faintest picture of its direful consequences.

Page 7

Why then, should I cast Him aside, after all the blessings which He has bestowed upon me? No, I will not--I cannot let go my hold upon the Saviour, though the Earth should sink, and bury me in its deep and awful chasms of destruction. He has been a friend, when all others have passed me by in silence and in scorn--He has smiled upon me, when every lip has railed out against me in loud and vehement denunciations--and blessed be His name, he has supported me when all would have gloried in my downfall.

Yes, gentle reader, God has sustained me in every vicissitude in which I have been placed, and I feel well assured that He will continue to sustain me, until He gathers me home, to rest with Him in endless happiness. What, but His mighty arm could have shielded me from the many dangers through which I was compelled to pass, when in the possession of wealthy, influential and relentless slave-traders and slave-holders? What but His power could have snatched me from destruction, when angered men raved at me, and stood with fire-arms pointed at my bared bosom? and who but He could have given me power to brave my oppressors, and declare my rights, when the thong and the scourge were about to be applied to me at Natchez? None,--no, I feel that it was He alone, that thwarted them in their proposed cruelty, and saved His weak and dependant creature from their savage and infamous designs. His holy name be praised--for, He has said that throughout all time, He will protect and encourage all his children, if they will but put their trust in Him.

Nor has He alone shielded me from danger and harm. He has, I have reason to believe, endowed me, as I have before stated, with the power and faculty of foreseeing events, which were to take place in my eventful career--and instructed me as to the path in which I should travel, by which to avoid their evil tendencies. This, I have studiously endeavored to do; and if I have, in any instance transcended my instructions, I can confidently assert, that it has been an "error of the head, and not of the heart." My liberation from bondage was promised me by my spiritual guide in the days of my youth, when the chains of slavery were first rivetted upon me--and the means and influences by which this happy event was to be consummated. Yes--even the year in which I was to become a free man, was made manifest to me, whilst toiling in servitude, and abject misery

Page 8

for the malignant gratification of my fellow man--and it was this knowledge which supported me throughout nearly forty years of unjustifiable bondage. My heart was cheered with the blest conviction, that I was, at that period, to become my own master, and acknowledge the right of none to command or drive me in the commission of earthly acts, save the almighty Father of the human family. And my freedom was brought around in the exact manner which the Spirit had set apart for it. The stern, rigid and independent, yet, at the same time, obedient course which as a slave, I pursued towards my masters, was also, persevered in, for the express purpose of fulfilling to the letter, the commands of my Guardian. Never have I knowingly thwarted its wishes, but once--and heavy, indeed was my punishment, in the loss of a portion of my thumb, and uneasiness of mind for a long time thereafter. All its promises to me, have been rigidly fulfilled--and though the clouds of disaffection, and affliction have lowered heavily o'er my domestic concerns--yet, all, I feel assured will again be set aright in obedience with its stern commands. Man--frail, impotent man has no control over them,-- he can neither advance, nor retard them in their nature or their march--and until the hour arrives, in which the spirit is to set matters in their proper light before the world, things must still exist in the uncomfortable way in which they now are.

Reader--this little narrative, which will in its pages show you more conclusively the power which this Spirit has exerted over me during life, and the implicit obedience which I have ever yielded to its dictates--is another object brought forth at its commands. For this purpose I was endowed with an education suitable for the object allotted me--and for this purpose, I have now placed myself before the public as an author of a strange race. You may laugh in incredulity, if you please--you may hoot at the idea of man possessing the power of foretelling events, and you may term me fool, idiot, or what you choose--yet, as I have shown you before that this power was given man in former days--you may rest equally assured, that such power has been endowed me by an allwise God. The work is now before you, and though it springs from a dark and benighted source; yet your humble servant prays you will appreciate its merits in a spirit of kindness and leniency. May God bless you.

Page 9

TO MRS. MARY S. SMITH,

Who for many years was to me a kind Mistress.

Lady,--in childhood, we were wont

To greet each others smile;

Were wont to romp in innocence--

In peace our hours to while,

But since age lower'd on our brow,

He wields his sceptre o'er us now.

The sainted mother blest us then,

And taught us of our God--

She taught our infant minds to bow

To his most righteous rod--

She taught our tongues to lisp his name,

And know He ever is the same.

She loved us both--her kindness seem'd

The love the angels bear--

She guided all our young desires,

Of sin, she said, beware--

And when in after years we stood

Before the world, we nam'd her--good!

Sweet were those hours to you and I,

When kneeling o'er our forms

She raised her hands to heaven, and cried,

Shield them from the storms,

Which rage through life--Great Father, save

Them from sin's dark, polluted grave.

Page 10

The tears then bathed our youthful cheeks,

We knew not why we wept--

But He was o'er us night and day,

And watched us while we slept;

And led us with a parent's hand,

To study well His each command.

Storms since have lower'd o'er our heads--

Life's ills have sought to lure

Our wayward spirits from His charge,

And all His laws abjure.

But like the leaden weights of sin,

Have failed to touch the soul within.

Lady, I love thee, though I claim

No kindred with thy race,

But as the playmate of my youth,

I still can see thy face,

And bless the child of her whom then

I loved to hear--not to condemn.

Thy kindness, too, in after years,

Was shown to me throughout--

Thy love for me through health and strife,

Cast evil spirits out--

And I have blest thy name, and wept,

To think of thee, whilst others slept.

O, may thy life be one of joy;

May care ne'er reach thy mind;

And may the God of Heaven bless

The friend of human kind--

And grant that His sweet counsel may

Enrich thy soul through endless day.

Page 11

Calm be thy pillow when in death,

Thy body shall recline--

When friends shall mourn thy swift decay,

Then tears of grief be mine.

The lowly sod which hides thy face

Shall water'd be by my poor race.

And now farewell! We ne'er may meet,

To join again the hand--

But yet in Heaven we shall join,

In God's ne'er dying band;

And in Love's concert voices swell,

To sing His praise--till then, FAREWELL.

Page 12

RECOMMENDATION:

We, the undersigned, have for many years known Wm. HAYDEN, the author of this work, and believe him to be an honest, upright man,--and withal, a Christian.

Isaac G. Burnet,

Jacob Burnet,

E. A. Sehon,

T. Baker,

John Davison,

J. C. Miller,

Jesse O'Neill,

F. Bodman,

C. Cottman,

C. Woodward,

John E. Williams,

John Griffith,

Mr. Kilbreath.

Page 12a

[Two Illustrations]

Page 13

NARRATIVE

OF

WILLIAM HAYDEN.

THE subject of this narrative was born in the year 1785, at Bell-plains, Stafford county, Virginia. The life of a SLAVE, may be considered by many, as a matter of no curiosity--not even the smallest quota of importance in the great drama of human existence. But when the Divine interposition of Christ interferes with the earthly career of mankind, it is the duty of ALL, to treasure each token, small as it may be, which he, in his gracious providence, may vouchsafe to us, as particles in the great chain of human events, which is to guide us through this "vale of tears," and render us fit to anchor our frail barques on the ever blessed shores of the New Jerusalem.

Hence, it is the object of the writer to relate, and to endeavor in the briefest manner possible, to point out certain matters connected with his history as a man--and as a member of community, to show to his fellow mortals the wonderful means, and the various ways through which God exhibits to us, his wonderful nature. To some, he gives wisdom--to some, wealth--and to others he yields a complication of gifts, such as, wisdom, a foresight

Page 14

of coming events, &c. Hence, the motto, "coming events cast their shadows before."

The latter was the means which Jehovah has employed with the subject of these few but serious reflections, and historical crumbs; and though they may appear as irrelevant, and non apropos, yet, ere they are finished, and perused by the kind reader to whose indulgence they are given, I feel fully confident that by a critical view of the same, he or she may be led to a full knowledge of God's means; of his supernatural agency in leading all to him, and which is considered by the world, or worldly portion of Creation, as superstition, and unworthy of aught save the contumely heaped upon the ignorant of the present day, and a comparison with the dark ages which have long since elapsed and passed from earth.

But this is all wrong. God works his wonders, not in one man--nor in any particular set of men--but in ALL, unobservant of clime and color. He has, in his wisdom, apportioned us as the beneficaries of his Divine precepts and gifts. None escape--the high and low--the rich and poor--all alike feel His wisdom, and acknowledge his goodness. It would be unjust, therefore in man to contend with Deity upon the principle of worldly elevation. The mighty in thought, are generally the very poorest in this world's gear. "All is not gold that glitters"--nor, yet is all unholy, which wears the semblance of the world, or pertains to the machinations of selfish and corrupt man. As an evidence of this, I have but to offer to the reader the case of the Apostle Paul. When worn down with disease; when racked with afflictions in both mind and body; famished and languid; dragged from a prison cell; emaciated, and almost disgusting to the sight of humanity--so cursed was

Page 15

he with vermin and the filth of a prison house, he presented a poor, and I might say, a pitiful contrast, when confronted with the royal Agrippa; the tyrant Felix; the vain-glorious, and coquettish Felicia, who had met to pass judgment upon him. Yet the spirit of the Lord was there--his powerful hand upheld his servant through his trials, and supported him through his afflictions,--it pointed out to him the road he was to travel, and the means he was to employ, in order to overcome the temptation and snares of the wicked, and reach the haven he desired. Rags could not disguise the MAN--the prison habits could not cover him from the admiration of all. Even regal authority, surrounded by its slaves, its worshippers, and its proselytes, was not able to withstand the power, in the hands of God's most humble, abject, and comparatively inefficient agent. The glance and glare of royalty vanished--a kingdom became paralyzed; and the highest power in Christendom, robed with the authority of the land; entrusted with the treasure of the kingdom, surrounded with wealth, wisdom and greatness, quailed before the eyes of Paul; quaked at his words, as they fell trembling from his lips, and the poor, royal trio, quivering in agony, made known their effect through Agrippa, by the fearful assertion: "Thou almost persuadest me to be a Christian." Such was the effect of God's words upon the world's great men, when delivered even by his abject and imprisoned servant; and at this more enlightened age, what may be the result of these few stray leaves, Time, and God's ways alone will determine.

Until I was about five years old, I was permitted to live with my mother, who was the property of Mr. Ware, of Bell-plains, and who resided on the banks of the Potomac

Page 16

creek. When quite an infant, not more than two or three years of age, I was known to crawl to the door of the cabin, and watch the rising of the sun. The Day God as he peered from the chambers of the east, and cast his reflection from the clear bosom of the Potomac, appeared to my infantile mind like two suns--the one in the heavens, and the other in the body of the waters; and every morning, it was my desire, and indeed, my first employment, to repair to the door and witness the rising of the two suns. How anxiously my mother, (fond and endearing as she was,) gazed upon me, as I was engaged in witnessing with joy, the beauties of Heaven, and Heaven's goodness.

This act was considered as remarkable in one so young as me, and many were the predictions, from men of influence and extensive learning, that in me, the slave would find a determined and consistent friend, whilst my race and my color would find a representative of their rights through the means of Christ, of which they should not be ashamed. At this age, too, the Spirit of the Lord was at work in my heart--my path of duty was pointed out--my many vicisitudes were before me--the acknowledged divinity of God was building up in my heart a throne, upon which to receive the offerings of many to a new knowledge of his grace--and through me, his humble agent, to lay down to my fellow creatures a new path--a new belief--a belief, unlike the Egyptian idols, but founded upon the uncontrovertable and inscrutable ways with which man is brought by a supernatural agency, to yield himself to Divine decrees, and throw off the yoke which Satan and the world has placed upon him;

"To be a man --a meek and lowly worm,

A firm despiser of all worldly scorn."

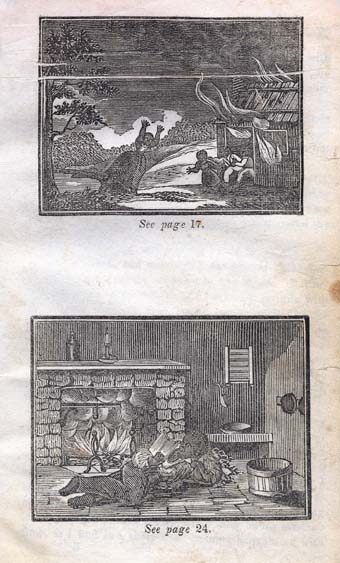

Page 17

Nor was this infantile practice--this pleasure of gazing upon the beauties of Heaven's goodness without its benign effects. One morning, on rising from my straw pallet, to seek the door of the cabin, the bed was discovered to be on fire. A sense of danger was even then apparent to my young mind, and through exertions and persuasions, I was enabled to be the instrument of God's holy wisdom, to save the lives of my sister and brother who slept in the same room. That sister now resides in Cincinnati, and can be seen at my house; having removed with my mother and me from Virginia, when our parent was freed. God's beauties were before my mind; his hand was over me, and leading me on; he made my soul, even at that early age acquainted with the fact, that I was to become an instrument in his hand, to work out in my feeble capacity, a portion of his divine work.

But to my Narrative:

At the age of five years, I was taken from my mother, who, for the preceding four years, had a presentiment, that she was not the one designed by Providence to rear me. The man to whom I was sold in the capacity of a slave, was named John Ware, and resided at Swan's Point, on the Potomac, and from that time until I was seven years old, I was engaged in travelling through various parts of the State, as a nurse. And I must be permitted to say for myself, that those children, who are yet permitted to exist, and whom I had the privilege of nursing, can still bear testimony of the affection I bore them, and which I had every reason to believe was reciprocal upon their parts.

But a change soon came over my master's affairs. He was a gambler and a horse-racer, and becoming involved

Page 18

in debt, he was necessitated to sell me. To some, this change might have appeared as an affliction of the deepest caste. But to me, although satisfied with my situation, is was a change for the better. My heart yearned for my mother, whose cabin I had left, and I hoped through God's goodness, to be enabled to procure a purchaser who resided somewhere in her neighborhood.

But a trial ensued. The nature of a master whose deception causes him to fawn upon, and flatter a slave, worked upon my youthful imagination, as it generally works upon the imaginations of all such, and was attended by a like result. A short period previous to my being sent off for sale, my master and mistress left home without taking me with them as a waiter. This, they had never before done, and I was at a loss to account for the change which had been wrought in their conduct. Previously, I had been a favorite, and having excited thereby the jealousy of my fellow slaves, I soon found that the absence of my master and mistress was attended with any thing but good results. The colored people of the household proved ungrateful, and by them, I was used with extreme harshness; hence, my strong affection for my mother, and the strong desire to be near her proved too much, and in my unguarded moments I caught one of my master's horses, and started on my journey. Herein, then, the reader will see the baneful influence of deception and ill usage towards a growing child. But being young, and unaccustomed to the treatment of a horse, I soon rendered him unfit for service, and was necessarily necessitated to perform the balance of the journey on foot. Hence, turning the horse loose, and tying the bridle around me, I made the best of my way towards my mother's cabin. And now, permit me to

Page 19

relate the consequences of deception. Being conversant with it in my master's family, it was an easy matter for me to coin a palpable lie--so, whenever I was asked where I was going, and what my business was, (as was often the case) my invariable answer was, that I was looking for a stray horse which had broken from my master's fields. My youth, and the fact of my having the bridle with me, proved a sufficient shield, and I was permitted to pass unmolested; and having often travelled the road near where my mother resided, I soon found the place, where I arrived in safety, after having travelled for upwards of a whole day.

When I arrived at my mother's, I was in such a state of nudity, and so apparently altered that she did not recognize me. I remained with her about a week, when the master whom I had formerly served, sent me home, writing at the same time to my tnen master, requesting him not to punish me, and as I was a great favorite, his request was complied with; but shortly after, I was sent to my mistress's brother, who resided and kept a store near Port Royal. This was in consequence of my master being in debt to him for goods, &c., and though gentle reader, you may think it strange, yet it is nevertheless true, that human flesh and blood--the living image of Jehovah himself, was pledged as an old Jack-knife is now-a-days, to the Shylock money-lenders in payment, until my master could attain the means wherewith to redeem me. To this event I looked forward with hope, but the time passed, and, not being able to obtain the money for my redemption, I was sent to Ashton's Gap, a place on the mountain, where an auction for the sale of slaves was generally held; and in company with five other lads, was doomed to undergo the ordeal of the flesh-barterer's

Page 20

hammer. And what think ye was the sum to be raised from the sale of six human beings? The mean and pitiful sum of $50. Here I remained three or four weeks, but time, which brings about all things, finally brought around the fatal day on which the traffic of flesh and blood was to take place. I have before remarked that from my infancy I was admired for my sprightliness, and whether this was the cause or not, I was the first one brought under the hammer, and strange to say brought the full amount of my master's delinquency. A further sale was deemed unnecessary, and the remainder of the boys were prepared to be returned home. During the day we had feats of wrestling, leaping, &c., at all of which exercises, I came off victorious. My young heart was elated with joy at my success, but when the moment came in which I was to be severed from my young companions, and when running to the carriage which was to convey them to their homes, their mothers, and all they held dear on earth, I was informed that I was doomed to remain, and seek a home with a strange master, my heart swelled within me and a flood of tears was the only balm left the benighted and sorely aggrieved slave. No mother's smiles were decreed to welcome me--no maternal words to soothe my pains, no kind and long known home to yield me sustenance and repose--naught but the clanking chains of slavery--the roof of a stranger, and my own sad reflections were meted out to me. Is it a wonder then, that tears gushed forth, or that the mind bent as a reed shaken by tempestuous blasts. Those who know the endearments of home, can duly appreciate my situation.

The master, whose property I became by this sale, lived in Lincoln county, Kentucky, and although he was deputized

Page 21

by his brother to purchase a slave for him, he having advanced him the money for that purpose, he saw fit to send me to his brother, as being small, and purchased a larger, though a sickly looking youth, whom he kept for himself.

On leaving with my master, we went to Farquar county, and there staid until fall, near Smith's Mills; and here permit me to relate an anecdote of our travels. In returning to the house of my new master, I was compelled to travel on foot, except when going down hill on the mountain. In those days, locks were almost unknown, as used for locking the wheels of the wagons which travelled the roads, and small trees were fastened to them to act as holds back. On these trees would I climb, and for the purpose of displaying my agility, seek the very highest limb; and many a severe fall have I received in being thrown from them to the distance of many yards in front of my high seat of honor, so many, that in fact I began truly to conclude that "they that stand high, have many blasts to shake them, and if they fall, they dash themselves to pieces," insomuch that I concluded to abandon my sport, and take the more modest and unassuming mode of travelling, to wit: "Shank's mare."

Some time after I was sent to my master's brother, whose slave I then became, my purchaser came to pay a visit to my master. He was accompanied with several gentlemen, who were aware of his trick in foisting me upon his brother, and when they saw me, so surprised were they, in comparing me with the one which he had kept, that in their teasing and jeering him on his "profitable trade," they let the "cat out of the bag," telling him that appearances were generally deceitful, if not

Page 22

totally opposite to the world's generally received opinions.

My master's name was Frederick Burdet, who resided near Georgetown, Ky. He was married to a Miss Cave, of whom I shall speak hereafter, as she proved to the friendless slave a mother and a guardian, when no relative was near to cheer his servile hours. Mr. Burdet was poor, owning naught of this world's gear, save me; but his wife was seised of three other slaves, and a small tract of land. But soon misfortune and disease visited the abode of my master. The fell Destroyer laid his chilly hand upon the latch, and bore hence to an unknown world the head of that much loved family. After his death, the Court decreed me to his unborn child.

As my master had raised me in a pious manner, and had intended setting me free, after he should have set before me the evils of the world, it became, as a matter of course, the duty of his wife to carry out his pious intentions. Being young, I generally repaired to a spring close to the house, and watching the sun as he rose, and cast his reflections upon the bosom of the spring, would often weep bitterly. In this I was indulged by my master, but after his death, following the same course, my mistress one day spoke to me, thus: William, if you be a good boy, and cry no more, I will be to you a mother; and placing one hand upon my head, and wiping the tears from her eyes, she raised them to Heaven, and supplicated God that he would enable her to fulfil her promise, and thanked him that he had placed some object in her way, to fill the vacuum occasioned by the death of her husband. To this I consented, but felt loath to abandon the spring, although she strictly fulfilled her promise. But from the spring I sought the chimney

Page 23

corner, where I first held communion with the Spirit, which seems to be my guardian angel to the present day.

When, however, it was known that I had only commanded $50, the neighborhood was greatly surprised, and many a dealer in human flesh, would have been anxious to have purchased me; but my good mistress loved me for her dear husband's sake, and not all the wealth of Mexico could have then induced her to part with me.

Shortly after my master's death, I was received into the house as the servant of my mistress, and when my young mistress was born, was initiated as her nurse, with the assurance, that if I took good care of her, I should be free as soon as Miss Polly arrived at marriageable age. This raised my spirits to a high degree, and I became still more attentive to my duties, determining to deserve, if it were really in my power, my freedom from bondage. It was, too, a matter of surprise and astonishment to witness the difference in my actions. Naught but the thought of being a FREE MAN filled my mind from morning until night, and I felt as if I loved my mistress with a ten-fold ardor, whilst it seemed to me that the Lord was watching over the destinies of the poor, friendless colored boy, who was far beyond the reach of parents and relatives. These thoughts inspired me to good actions; but sorry was I, when my young mistress was about two years of age, to witness the lowering of my first cloud of sorrow. It loomed dark and heavy upon me, and has continued to grow darker and darker around me until the present day. At that time my mistress, needing no doubt the proceeds of my labor, as I was large enough to plough with a shovel-plough, hired me out to a man named Henry Barlow. To him I proved useful, and as I was always brisk in

Page 24

running errands, and doing chores, I was universally liked and admired by both black and white.

I remained, however, but one year with Mr. Barlow, when my mistress's brother, Mr. Henry Cave, without her consent, hired me out for six years to a Mr. Elijah Craig, a rope-maker in Georgetown, and it was in this place that the Almighty, in his wisdom saw fit to reveal to His humble creature, the future destiny of his days--to open to him the various paths in which he was to tread, and to point out to him the straight and surest way by which to arrive at the goal of happiness for which his stricken soul panted. Blessed be his holy name. He has upheld me through good and through evil report, and placing all confidence in his supreme power, I feel that he will continue to watch over and bless his sorrowing creature.

Soon after I came to reside with Mr. Craig, I was placed by him in the rope-walk, for the purpose of learning the rope-making business, and being very attentive, and quick of apprehension, I became a favorite with my employer, and set to work at spinning much sooner than is customary with the generality of boys; but being naturally good humored and quick on foot, I was frequently called from my work to run errands, and it appeared to me as if the fates were arrayed against me, for as soon as one "chore" was done--another stood ready waiting for my attendance. But this state of things was soon brought to an end, for it was soon discovered that I lacked but strength to be a first rate workman, and was accordingly sent with some others to Frankfort, Kentucky, to work in a "walk" of Mr. Craig's, under the management of a Mr. James Davis, with whom I had been but a short time, before I became a general favorite with my employer. And here I must digress for a brief time to return to my mistress.

See page 17.

See page 24.

Page 25

When I parted with her at Georgetown, it was with tears, in which, kind woman, she, as well as myself, indulged freely. At parting she made, I well remember this remark:

"William, if you are ever whipped by any to whom you are hired, remember, I charge you, to return home immedately, for I can permit no one to correct you but myself."

When, then, I had been some time with Mr. Davis, for some trivial offence I was whipped, and remembering my mistress's words, I returned to her. But what was my surprise on hearing her exclaim, when I had narrated the circumstance to her:

"Go back, my boy, and stay till I send for you."

I was shocked, and although I was several times flogged thereafter, I never returned to her again. But my ruling star was uppermost, and I became a favorite with Mr. Davis's children, who taught me to spell, and for this act of kindness, I was always ready to accommodate them in any way I could. Unlike a majority of slaveholder's children, they were not above teaching the poor colored boy to spell and read, but seemed to pride in my rapid progress, which has endeared them to me through this cold and inhospitable world.

But as youths generally like a little spending money with which to enjoy themselves, I soon cast about me for a means of obtaining it. An opportunity soon presented itself, and as we lived near the Kentucky river, I applied myself during my leisure moments to fishing, at which I was generally successful. These fish I conveyed to market, and obtained a considerable sum of spending money, without, in the least, encroaching on my master's time, as I had in a short time became acquainted with

Page 26

all the inn-keepers, who did not hesitate to purchase my "FINNY TRIBE."

This success was followed immediately by another. Having become intimate in my fish speculation with the principal inn-keeper in Frankfort, I made arrangements with him to work for him on holidays and Sundays, cleaning boots, washing dishes, &c.; and in this capacity was my leisure moments employed, during my whole sojourn at Frankfort.

About six months, however, before my time expired with Mr. Craig, my mistress had me a new suit of clothes made and sent, with directions to Mr. Craig to purchase me shoes, stockings, and other necessary "FIXINS," and charge the same to her: so, that for the first time in my life, I had a suit of Sunday clothes.

I here, about this time too, met with a still greater success, by becoming acquainted with Miss Martha Johnson, who lived near Mr. Toleman's, and to whom, through the interposition of Divine Providence, I am indebted for the completion of my limited education. And now, with the permission of the reader, I will commence giving data of my future events. Previous to this, my memory has failed me, and as it was the events of, I might almost say, my infancy, they have passed to the bourne of things forgotten.

About the year 1802, all the hands hired by the year in the rope-walk at Frankfort, were sent home again; but as my contract was for six years, I was compelled to stay six months longer. In the spring of this year I again went to Georgetown. On arriving there, my mistress did not recognize me, so greatly had I grown, and in fact since I had left Georgetown so great had been the improvement both in growth and mental endowments

Page 27

with my YOUNG mistress, that I was at a loss to recognize her. During my absence, however, my mistress, had taken unto herself a second husband, which so much grieved me, on account of the love I bore her dear departed help-mate, that I felt very loath to return home. But as I had not seen any of them for many years, and as they were all anxious for me to return, I was soon compelled to forego my objections, and seek a home again, under the roof of my mistress.

Whilst I was in Georgetown, a new building, which had been reared during my absence, attracted my attention. On a flag stone in front, I discovered some marks which appeared to me as unintelligible as the hyeroglyphics of the Chinese. But I was determined to ascertain their purport, and accordingly asked a gentleman who was passing, the meaning thereof. He informed me that it was the year in which the building was erected; and from this I was aware that the succeeding year would be 1803. This inspired me with a love of figures, and so intently did I set myself about it, that I was soon a tolerable hand at calculation.

At the end of the year I again left Georgetown, and was hired to a man by the name of Peter January, sr., in Lexington, Ky., who owned a rope-walk there. Here I first saw Mr. Clay, who was then engaged in ornamenting his present residence at Ashland. With this gentleman, I became acquainted through the recommendations given him of me by his children, whose acquaintance, I had made previously, and with him I afterwards became a great favorite.

This gentleman and his lady were set apart by my guardian Spirit as my benefactors in time to come. Mrs. Clay

Page 28

has already proved such to me, having used me with the tenderness and sympathy of an indulgent parent.

Before the year was out, too, it was discovered that I was so good a hand in the rope-walk, and so attentive to all the duties assigned me, that all the factors in the place were anxious to obtain me, so that a choice of homes was thus unexpectedly held out to me, of which I was exceedingly glad.

Casting among these people, then, it was my good fortune to accept the proposals of Mr. J. Ware, who had formed a friendship for me, and with whom I resided eight years.

In 1804, I went to board with a wagon-maker, by the name of Edward Howe, who generally employed a great many workmen. For these, I performed all the little offices they asked of me, insomuch that they were so well pleased with me, that they all agreed to teach me my lessons in reading, in order that I might become more perfect. To induce me, however, to devote some portion of my time to pleasure and amusement, for so studious had I become that they feared for my health, they would persuade me to play marbles with them, agreeing to learn me so many lessons, for so many games, so that in a short time, I began to like the amusement, and even progressed farther in my studies.

Soon after I went to board with Mr. Howe, it was my good fortune to meet with Miss Johnson, my former instructress. She was at this time teaching school, which was composed of the first families of the place, and having no one to cut wood, or run errands for her, I made an arrangement with her to do her "chores," provided she would teach me at nights, and on the Sabbaths. This she accordingly did, and she often unconsciously

Page 29

filled me with joy, by remarking, that in the little time I had, I made more rapid progress in learning than many of the white boys with all their boasted privileges, and assiduity.

In the same fall, (1804) I became acquainted with Mr. Postlewate, a tavern-keeper, and went with him to clean boots, &c., as I had previously done in Frankfort.--During this time, I did not charge Miss Johnson any thing for the services which I rendered her, as I considered that the learning which she gave me, more than cancelled the obligation. But as I had now become, as I thought too large for a servile occupation, I began to be ashamed of cleaning boots, and consequently, obtaining an old axe, and putting it through the grinding operation, I concluded to make a good living by chopping wood. Through the influence of Miss Johnson, I obtained the work of all the parents of her scholars, so that I had now as much as I could possibly do.

Shortly after this, some of Miss Johnson's relatives came to Lexington. They were players, and engaged in the theatre in that place, and as they went to house-keeping immediately on their arrival, I soon became their "man of all work," so that I felt myself at home, either at their house or that of Miss Johnson. But in 1805, I again went to rope-spinning, and was soon acknowledged to be the best spinner in the country, so that again a choice of homes was again held out to me. This good fortune induced me to tell Mr. Ware, that I would not stay any longer with him, unless he would advance my wages. This, at first, he refused to do, but at last consented to raise them to $6 per year. At that period, twine was worth more at the South, than it ever has been since, bringing from 75 cents to $1 per pound. My task at

Page 30

spinning was forty-eight pounds--and this was considered a good day's work for two men. This task I generally accomplished--gaining two days in every week, exclusive of the Sabbath. The proceeds of these two days amounted to three dollars, which it was optional with me to make, or devote my time to pleasure, if I saw fit so to do.

And now comes a question which many of my readers may smile at, as deriving its existence from Superstition. Meeting one day with Miss Johnston, I inquired of her, if she had ever known any one who could foretell what was to happen in after days. She replied that she had heard of people who had foretold things, and wished to know why I had proposed the question to her. My eyes brightened--my heart beat with a nervous anxiety, and I informed her that I could foresee the day when I was to become a FREE MAN; and that although I had been torn from my parents in my infancy, the day was in prospective, on which I should again meet with them.

The reason of my making this inquiry, was simply this--I had been for several weeks engaged in burying the chips which fell from the logs which I was chopping, on the lot where the house stood. This act I had been commanded, by the Spirit to do; and that, if I strictly fulfilled its mandates, the house should be removed, and no one should occupy the lot, until I had written a Narrative of my Life. Many years have since elapsed--and yet, the lot is vacant, and none seem disposed to occupy it. When, however, I told Miss Johnson this, she smiled, and doubted the virtue of the Spirit--to which I replied that, in four years from that time, we should meet for the last time upon earth, and part, with many tears. This, in the year 1807, was literally fulfilled--and my

Page 31

prediction, so strangely verified, seemed to remove all doubts of my future destiny from her mind. God bless her--for she was to me, a friend indeed.

And here, gentle reader, permit me to give you a brief outline of my progress, and the means by which my limited education was acquired. The only book which I could command, was composed of the leaves of an old Spelling Book, which I had picked up, and sewed together, and from this I gleaned such instruction, that I was soon enabled to read the Testament with ease. From that--I attempted writing; which at first, was a difficult task for my friends to persuade me to undertake, as I was then under the impression that it was without the pale of a colored man's nature, to ever be able to write. The substance of this I remarked, to a friend who worked with me in the rope walk, and who after calling me a fool, informed me that he would guaranty to teach me how to write in a short time. He then got a small stick and pointing it, stooped down and wrote "W. HAYDEN," in the sand. After a long time, I was persuaded to make the attempt of copying it. The trial proved successful, and so great was my joy, that tears of pleasure trickled down my face. After this, I would go round the Court House, and picking up all the fragments of paper, I could find, would bring them home. I was afraid however, to attempt reading them, as my playmates informed me that if the white people, caught me reading or writing they would hang me. Whether this assertion was made in ignorance, or through envy, I never ascertained, but certain it is, that it had the desired effect; and consequently I was compelled to get some of the "walk hands" to read them for me, and when I got by myself, I would, with a stump of a pen which I had picked up, endeavor

Page 32

to copy them. My ink, I made by boiling walnut bark and coperas, and having obtained some paper, abandoned my copies in the sand, and took to pen, ink and paper. In this manner, I succeeded in writing a tolerably legible hand, of which I was extremely proud, and would often reason with myself in this wise: "Yonder is a WHITE man--he has seen the frosts of sixty winters, and during that long period, has never been able to learn to read the word of God, or transmit by writing one solitary thought to his distant relatives and friends; whilst I, a poor, friendless colored boy,--a slave--can read the consolations held forth in the Scriptures, and inform my distant friends of my progress through life. O, the difference! I would not part with my little knowledge, for all the wealth of your illiterate dealer in flesh and blood!"

In the year 1807, there was a school started for some colored children, whose fate it had been to be bound out; and as their masters did not want them taught by a white man, they engaged a colored one, belonging to Dr. Downey, to instruct them in spelling and reading. This man was known among us as "Ned,"--what his surname was, I never ascertained. As there were not enough FREE children to make up the school, notice was given, that any one wishing their servants taught, (if they were willing to entrust them with Ned,) should be permitted to send them to school. On hearing this, I applied to Mr. Ware, and having obtained his consent, started, with three others, from the same factory.

The school was composed of about thirty scholars, and considering myself and my companions, as naught but rope hands, we were for a time reckoned as fit butts for all jeering and jesting. This, however, we heeded not, but attended to our books, and by close attention, I

Page 33

was soon at the head of the first spelling class in the school, They were not aware that I had been to school before, and remembering their former conduct, I cared not to inform them of the fact. Ned, too, raised upon my shoulders, for it was generally considered that it was by his exertions that I made such rapid progress; and as a reward for my diligence he made me sub-teacher, and gave to me the charge of the younger children. Previous to this, however, Ned, rather offended not only myself, but all who were connected with the affairs of the school. Being "Principal," and striving to gain favor with some, he paid strict attention to the free children, and would sometimes neglect hearing us our lessons, for upwards of a day, in order to facilitate them. To this I objected, backed by Mr. Duke, and others. At last broaching the subject, (and merely because I spoke my mind freely,) I was deserted by my backing, and was finally expelled from the school. Sore as this occcurrence was to me, the Spirit upheld me, and I was finally rewarded for my obedience to its dictates.

"-- He stood,

The proud monument of flesh! Yet still,

The softest whisper of the Word Unchangeable,

The Spirit, and the Lord,--bade all return;

And mortal schemes were lost!"

The Trustees of this School, allowed the citizens to have a Night session, if they could procure a teacher. After looking around, they procured not only a teacher, but a room from Mr. Benj. Duke, or, as many called him Mr. Benjamin Almond; an individual of high standing, having a house of his own, in which he, every Sabbath, and often during the week, held Divine service. At a meeting of the Trustees, he and his brother, who were,

Page 34

great friends of mine, recommended me, and agreed to vouch for my abilities and good conduct. This act of kindness they performed, without my knowledge. When, therefore, in a few days, I was called on by Mr. Duke and his lady, and informed of my nomination and election as teacher, I was greatly surprised, and not knowing what answer to return, I informed them of my total incapacity to teach, and of my want of means to rent a room. But Mrs. Duke overruled these objections, informing me that Mr. Duke had prepared his basement story for me, and that she would see I had no difficulty with the children as she would make them behave. Still diffident, to take charge of a school, I told her that I had no place to sleep. This she also overruled, telling me she had a cot at home, and that I might sleep there: so that I was compelled to reward their kindness by an acceptance of their offer. My closet at this time in which I kept my wardrobe was an old flour barrel, and this I conveyed one dark night to my school room.

Mr. W. W. Watson, and Mr. Henry Blue, who were then youths with myself, will no doubt recollect these occurrences, and testify to their truth. They are both, now, worthy and respectable citizens of Cincinnati.

The news of a school being about to commence, spread like wild fire, and when the children came to the house, inquiring for the master, so abashed was I that for a time I hesitated to say I am he. But this bashfulness soon passed away, and I commenced operations by drawing up and laying down a code of rules, by which my school was to be regulated.

The principal rule was, That there was to be no talking or whispering in school during school hours, which were from seven to ten o'clock, P. M. That this rule

Page 35

applied to both old and young, regardless of merit or standing, and that any disobeying, or knowingly violating the rules laid down should be punished, by being turned out, regardless of the weather--if this appeared too hard, they had better withdraw, as their names should not be enrolled. I informed them, too, that I had been elected their teacher by a board of Trustees, that I knew but little, but what I did know, I was determined to teach to the best of my abilities, and that it was as much to their advantage as it was gain to me, to comply with the rules of the school. This brief code offended many, and the consequence was, that they left the school; but on informing their masters of the cause, so pleased were they, that they induced many gentlemen to send, who would not otherwise have done so, not knowing who or what I was. At length my duties commenced, and I soon gained the respect of my scholars to such a degree, that upon their representations, their masters authorized them to invite me to their houses on the Sabbaths, in order that they might see me. They did so--and when their masters became acquainted with me, they appeared surprised that a slave negro, should be so superior in learning to the free negroes, and declared that a person of my information should be immediately set free.

This was in the latter part of the year 1807, the same in which I had commenced my career as wood-chopper. But now, that I was installed as a school-master, my vanity was touched, and I began to consider myself above my old playmates; (O, the follies of youth!) and having the confidence of both my colored and white friends, among the latter of whom was a lady, whom I called "mother," from the kind treatment which I experienced at her hands; things went on right smoothly.

Page 36

Whilst I was teaching, however, there came to me a young girl, who was a great favorite with her master, to learn to read. Her master would not permit her to keep company with colored folks, as he considered her much superior in grace and mental endowments, to the generality of her race, which, in fact, she really was. For me she soon formed an attachment, and from her representations of me to her master, he requested her to invite me to come and dine with her on the following Sabbath. I accordingly went, and so pleased were they with me, that Mr. Yaiser, (the master alluded to) took the trouble to inquire of my friends, if I was honest, as he felt disposed to become my friend.

About this time, my term ended, and as I had quit the wood-chopping business, I was at a loss what to engage in as a means of living. The inquiries of Mr. Yaizer, however, relative to my character, were answered satisfactorily, and he, being a tanner, and wishing to employ a person in whom he could trust, to attend markets and purchase hides, I was engaged. This business was generally performed before day, and delivered at his yard, he paying me a per centage on every hide delivered. My success at this was various; sometimes making as high as $2 50 per day. Here then, I felt again my indebtedness to the Almighty, for his merciful guardianship over me--for as soon as one business afforded me no longer the means of support; another was provided for me. In this way things progressed until 1809.

During all that at time I had not lost the hope of again seeing my parents; and so anxious was I to hear from them, that I inquired of every traveller with whom I met, if they were from the vicinity of Falmouth, Virginia. At last I met with a wagoner, and whilst inquiring from

Page 37

whence he hailed, an old woman who was with him replied that she was from Falmouth. Here my mother had acted in the capacity of midwife, and I concluded that she must know something about her. Whilst revolving in my mind whether to ask her or not, the old lady inquired my name. I told her it was William, and that of my mother was Alcy--and that she belonged to Mr. George Ware, who lived at Bell-plains, Stafford county, Virginia. The old lady eyed me sharply for a few moments, and burst into tears, saying, that I was so much like my poor mother, that she would have known me any where, and informed me that she had just come from where my mother resided, and that she had charged her if she found her son any place in Kentucky, to give him her blessing, and write to her immediately. The old lady could not write,--consequently she got the overseer to write to my mother, the joyful news that the lost was found. I then applied to a friend to indict a letter for me, which I immediately endorsed and despatched to my poor, dear mother; to which, in a few months I received an answer, which filled my heart with unspeakable joy.

In the fall of 1809, I again went to Georgetown, where my old mistress still continued to reside. The young miss who was but two years of age, when I first left Georgetown, had now budded into womanhood, and was upon the eve of marriage. The reader will remember, that after the death of my master, the Court consigned me to her as her property, hence, as she was about taking to herself a husband, it was thought best that I should remain in Georgetown until the event took place; consequently I remained, living mostly at home. But here my pride was aroused--I had travelled considerably,

Page 38

and had resided in large places, and I was illy contented to remain in so small a place as Georgetown; so after a short time, I again went into a rope-walk to work, and notwithstanding there was an experienced white man superintending the business, he could show me nothing that I did not already know; hence I soon became the foreman of the factory. From this time I was treated more as a white man than any thing else, as all were acquainted with my deportment whilst in Lexington; and should this Narrative ever meet the eye of any slaves who can read it, let them take my conduct towards my masters as an example. I can assure them that they will be treated with kindness, and rendered still more happy in the bondage in which Providence has seen fit to cast their lots. Nor did I confine myself exclusively to the rope-spinning business. Whilst I was in Lexington, I had learned to make a good article of blacking, and also a polish for morocco shoes of every color, so that I soon got more work of this kind, than my leisure hours would allow me to perform, from the good citizens of Georgetown.

But the day of my mistress's wedding at length came around, and I was sent for to attend. Previous to this, my old mistress had assured me, that it was her intention, as soon as her daughter became of age, to purchase me for herself, and give me a chance of buying my freedom. Now, that Miss Polly was of age, and about to be married, I considered her promise as about to take effect, and looked forward with pleasure to the brief space of time which was to intervene, and to the day, when I could stand forth as a man, and say to the world, "I AM FREE," "free as the air which scales our hills--or as the streams which leap our rocks." But disappointment is

Page 39

the lot of frail humanity; and on the day of the wedding, all my high hopes of freedom were blasted. Whilst the wedding party were at the table, I unconsciously called the Preacher, who had performed the marriage ceremony, "Old Massa." He demanded of me why I did so; and I informed him, that it was because I had lived in the town with his son-in-law, Mr. Hawkins. He said that he had never seen me there to his recollection, but that he had seen me somewhere else. He then asked my mistress if she had raised me; to which she answered that she had, from the time I was seven years of age. He next inquired of me if I knew where my parents lived, and when I told him, he observed that he had been in search of me for ten years, having known my old master, at whose house he had frequently met with my mother; and that he had at her request sought for me in every gang of boys that he had seen in Kentucky--for when he was in Virginia, he saw my mother, who was well, but much distressed on my account, thinking that when I was taken away, I was too young to be raised, and feared that she would never again have the pleasure of beholding her long lost son. He told her that if he ever found me, he would purchase me, and when I grew up, he would send me to see her. He appeared to be surprised, that he had not before recognized me, as the resemblance to my mother was very striking--so much so, that he assured me he would have known me if he had met me in any State in the Union. In a short time, too, he inquired of my mistress if she would sell me, who informed him that I was the property of her daughter--that I would have to be appraised, and that she intended purchasing me herself if she could, for the purpose of setting me FREE, and asked me how I would like to be a

Page 40

free man, to which I replied, with tears in my eyes--"very much, mistress, God bless you!"

The gentleman then remarked that Mr. Smith, the individual who had married Miss Polly, lived upon his place, and that he had expressed a desire to own it--and that if he was still of the same notion, he would endeavor to give him a trade. Mr. Smith, however, observed that I was spoiled, and that he would be under the necessity of bringing my high notions down a few "button holes," which remark grieved me so much, that I told my old mistress that I would not live with him any length of time. This news seemed to distress her to such a degree that I said no more.

In a short time the day came for the giving up of the estate, and Mr. Smith, knowing my determination of not living with him, set me up for sale to the highest bidder. There were present six gentlemen, who were anxious to purchase me, and I bid fair to command a high price--a price as infamous to the dealer in human flesh, as the thirty pieces of silver, which bought the Son of God, and yielded him up to an ignominious death. Like an ox brought to the shambles for the scrutiny of butchers, I stood before that flesh-buying crowd, awaiting the last stroke of the hammer--the last tone of the crier's voice, which was to consign me to a strange master, and perhaps a stranger land. Can such deeds prosper? Can the Shylock who deals in human flesh, the flesh and blood of his brethren and his sisters, expect to atone for the dark crimes which he is daily committing? Can Salvation reach his guilty soul with the shriek of the murdered slave ringing in his ears, and the phantoms of departed innocence, hovering about his guilty head? The Lord's will be done.

Page 41

Among the individuals anxious to purchase, me, were Major Carneal, who is now residing in the city of Cincinnati, a worthy and respected citizen; Mr. Robert Wickliffe; Thomas W. Hawkins; Mr. Turner Haden and Governor Garrard, the gentleman whom I met with at my young mistress's wedding, and who became my purchaser. He, however, still kept me at work for Mr. Hawkins, to whom he afterwards transferred me, with this understanding:--that at the expiration of five years I was to be set free, and furnished as a freedom gift with a horse, saddle and bridle, and a suit of clothes, worth at least $100, to carry me home to Virginia. Here, then was another prospect of freedom, and my mind was filled with naught else than making money to bear my expenses home. But all earthly calculations, unless predicated upon the word of God, are but vanity and vexation of spirit. I was doomed again to be disappoinned; for, in 1811, Mr. H. became bankrupt, and was compelled to part with his property and me, in order to extricate himself from his difficulties. The purchaser was his brother James, who did not act so kindly toward me as was my desire, and my general usage theretofore.

As some of my readers may doubt the events above mentioned. I would refer them to Mr. Carneal, who gave way to Governor Garrard, through motives of delicacy, at the same time stating, that if I chose HIM, he would take me immediately to Cincinnati, where I would be free as soon as I touched the shores of Ohio. But the Spirit commanded me to make no choice--that it would bring me out of my trials unscathed, and I became the property of Governor Garrard. For Mr. Carneal, however, I have ever entertained the greatest kindness and gratitude, for

Page 42

his sympathy to me on that occasion. May God bless and protect him through life.

Here, then, another crisis was before me. The foreman of the factory, and I, having served our time in the same place, were upon such intimate terms, that he refused to punish me for any of my youthful misdemeanors, hence it was thought advisable to remove me from his supervision. Previous to this, however, I had a long spell of sickness, during which, many thought that I was poisoned; but through God's Divine mercy, at the expiration of six months, I was restored to health. My physician was Dr. W. H. Richardson, of Lexington.--From the rope-walk I was sent immediately to Frankfort, to act in the capacity of house-waiter. But--I have inadvertently got ahead of my Narrative, and with your permission, kind reader, will return, and travel back with you again.

Mr. James Hawkins, was, at the time of purchasing me, engaged to be married to a young lady by the name of Miss Chew, who resided in Jefferson county, near Louisville, and as he desired to visit his intended bride, in a style consistent with that of wealth and aristocracy; and as I had now become the possessor of a horse, saddle and bridle, his conclusion was, that I would be an indispensable appendage, in the capacity of waiter to him, on his journey. This was what I desired, as I wished again to be travelling; therefore, I embraced the opportunity, and having arrived at the top of my trade, I bade farewell for a season, to the rope-walk. Shortly after I accompanied my master, and staying about a month, we returned. On our return, it was found that they could get along without me in the rope-making department, although at first they had conceived it to be a

Page 43

matter of impossibility; consequently I accompanied my master on a journey to Frankfort, at which place he left me. I was now somewhat at the a loss to know what to do, to earn some money, for strange as it may seem, after so many disappointments, I had not lost the hope of becoming at some period, a FREE man. But Providence again pointed out the path in which I was to tread. I performed so miserably in the house that there was much fault found with me, which induced them to desire me to work out of doors; but as I had never worked in the sun, I could not stand it. This was, however, nothing more than contrariness, as I had my mind so fixed on Freedom, that I was not willing to do ANY THING. I was willing, nevertheless, to do one thing, i. e. to hire my own time, and to pay for it at the rate of $10 per month; but this was refused, and I was sent back to the factory to work. Here I did so badly, that they at last agreed to receive the $10, and permit me to have the use of my time. I had at this time $60 in money, deposited in the store of Mr. McGowan, and a horse worth $60. After I left the rope factory, I commenced cleaning clothes, boots, shoes, &c., for such gentlemen as gave me employment; and at nights I was employed at all the parties to play the tamborine--running errands--carrying messages, &c. My friends now advised me to learn to shave, and I concluded that I had better undertake it.

In the Spring of 1811, I packed up, and went back to Frankfort. I left my horse with a friend of mine with directions to sell him, and after paying himself out of the proceeds for his trouble, to remit me the balance wherewith to pay my hire. I then went to the Barber shop of Mr. John S. Gowans, who had formed a friendship for me during my boyhood, when acting in the capacity of a

Page 44

fish-monger, and who felt disposed to aid me all in his power. Hearing that I had come again to Frankfort, he held out the hand of fellowship to me, and that friendship has left its indelible mark upon my heart which can never be erased, until I meet him again in the Land of Spirits, whither he has long since departed.

After telling my friend my circumstances, and my desires, I asked if he would undertake to learn me the trade. After a long parley, during which he gave me little encouragement, he requested me to call again after breakfast, and he would give me a final answer. I did so, and he told me to watch him, whilst he was shaving some of his customers. This request I rigidly obeyed, as also his manoeuvres in cutting hair. After he had finished, he sat down by my side, and conversing long and candidly with me, he gave me a pair of razors to dress. I retired, and in a short time returned, showing him the one on which I had been working. He examined it carefully, and saying that it was as well done as he could do it himself, requested me to undertake the other. I did so, and and having finished it, I again met with a similar praise. The apprentices were rather taken a back, for at first, they had considered it a capital joke, that a factory boy should presume to learn the Tonsorial art; but who, now, no doubt concluded, with Sam Patch, that "some things can be done as well as others." He then advised me to get a cup and box, and having given me a pair of razors and a hone, he told me to take them, with a clean towel, and go the rounds of the town every morning, shaving as many as I could for half price, and that in the course of a few weeks, I would be able to set up shop for myself. Before parting with him, to enter upon the duties of my new occupation, I asked him what he charged for

Page 45

the kindness he had shown me, and the advice and instruction which he had given me? His reply was, "the only recompense I ask, is, that if you ever see any of my children, or grand-children in need, you will aid them as well as you can." To this I gratefully assented.

It was now nearly night; but elated with the prospects before me, I determined to go to Georgetown, and commence business, consequently I started, and reached that place about midnight.

The next morning I visited the inn, then kept by Mr. Leonard George, armed with the implements of my new vocation, and as good luck would have it, there happened to be a stranger present, who had but a few minutes before, been inquiring for a barber, which, previous to my debut, was an article the Georgetownians did not possess. As soon as he saw me enter, he took his seat, and called for a "shave." Now, the idea of "Billy Hayden" turning barber, was a fruitful theme of amusement for many of my friends, who stood around, laughing in their sleeves, and thinking, no doubt, that the whole affair would end as an amusing hoax, at the stranger's expense.

Nothing daunted, however, I put my razors in order; and placing my napkin under the stranger's chin, I proceeded to the task of "mowing" off his beard, as confidently as if I was an old and experienced hand at the business. All were surprised,--and the gentleman, when I had finished, acknowledged that he had never received a more "comfortable shave" in his life. But when he was informed that his face was the first that I had ever touched, he appeared utterly astonished, and predicted for me a high standing in my vocation.

For some time I continued to follow the occupation of "street barber" for the Georgetownians,--and at the end

Page 46

of the first month, was much gratified to find that I had made $8, clear of my expenses. At the end of two months, my friends proposed to build me a shop, if I could, by any means, procure a lot. I immediately spoke to Mr. Hawkins, (my master) who consented to lease me a lot, and receive his pay therefor, as fast as I made it at my occupation. Not wishing to tax my friends, too, Mr. Hawkins subsequently agreed to build me a shop, which he did.

I had at this time, a female friend, whom I proposed to hire from her owners, in order that we might live together, and make money much faster than I could alone. This I accomplished--and an opportunity for speculation soon presented itself. There was a room underneath the Court House, which the jailor agreed to let us have, if we would clean it out. We accordingly did so, and stocking it with cakes, candies, mellons, nuts, &c., we embarked in another business, connected with my Tonsorial practice, and the consequence was, that we were soon enabled to lay by a considerable sum of money.

But my good fortune stopped not here. Shortly after we embarked in the cake-selling line, Mr. Job Stephenson had a lottery, at which a lot of saddlery was to be disposed of. After much persuasion, I was induced to take a ticket, and the result was, that I drew a saddle, worth $30. I now began to think myself a really fortunate man. My next chance of speculation, was a new assortment of confectionaries, and as I had a great many acquaintances in Lexington, and bearing a good character for honesty and industry, I was enabled, through their influence, to dray to any amount that I saw fit. Again I met with tolerable success.

Whilst trading in Lexington, however, I became acquainted

Page 47