Trials and Confessions of Madison Henderson, alias Blanchard, Alfred Amos Warrick, James W. Seward, and Charles Brown, Murderers of Jesse Baker and Jacob Weaver, as Given by Themselves; and a Likeness of Each, Taken in Jail Shortly after Their Arrest:

Electronic Edition.

Henderson, Madison

Warrick, Alfred Amos

Seward, James W.

Brown, Charles

Chambers, A. B., ed. by

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Cornell University

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc. and Elizabeth S. Wright

First edition, 2004

ca. 333K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2004.

Source Description:

(title page) Trials and Confessions of Madison Henderson, alias Blanchard, Alfred Amos Warrick, James W. Seward, and Charles Brown, Murderers of Jesse Baker and Jacob Weaver, as Given by Themselves; and a Likeness of Each, Taken in Jail Shortly after Their Arrest.

Madison Henderson, alias Blanchard

Alfred Amos Warrick

James W. Seward

Charles Brown

A. B. Chambers

[iv], 76 p.

Saint Louis:

Printed by Chambers & Knapp--Republican office.

1841.

Call number Trials K540 .T75 no.25 (Law Library, Cornell University)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

This electronic edition has been transcribed from digital images supplied by Cornell University.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Slaves' writings, American.

- Last words.

- Henderson, Madison, d. 1841 -- Trials, litigation, etc.

- Warrick, Amos Alfred, 1815-1841 -- Trials, litigation, etc.

- Seward, James W., 1813-1841 -- Trials, litigation, etc.

- Brown, Charles, 1814?-1841 -- Trials, litigation, etc.

- African Americans -- Biography.

- African American criminals -- Biography.

- Slaves -- United States -- Biography.

- Murder -- Missouri -- Saint Louis.

- Trials (Murder) -- Missouri -- Saint Louis.

Revision History:

- 2004-09-22,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2004-03-10,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2004-03-03,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2004-03-03,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

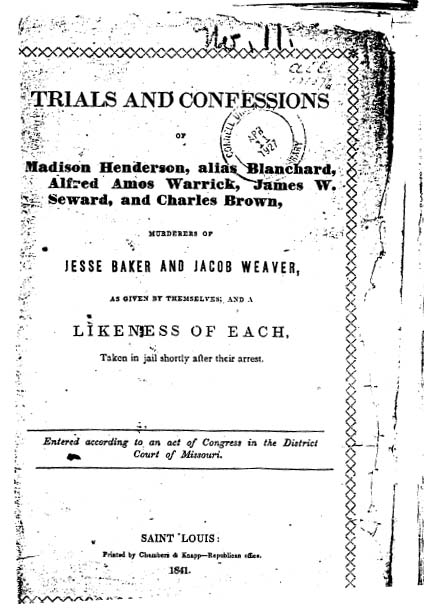

[Title Page Image]

TRIALS AND CONFESSIONS

OF

Madison Henderson, alias Blanchard,

Alfred Amos Warrick, James W.

Seward, and Charles Brown,

MURDERERS OF

JESSE BAKER AND JACOB WEAVER,

AS GIVEN BY THEMSELVES; AND A

LIKENESS OF EACH,

Taken in jail shortly after their arrest.

Entered according to an act of Congress in the District

Court of Missouri.

SAINT LOUIS:

Printed by Chambers & Knapp--Republican office.

1841.

Page [ii]

The writer of the following confessions begs leave to remark, that they were severally given voluntary & without inducement or restraint; & that nothing has been inserted but what was expressed by the convicts. in a cell separate and apart from each other and from all persons. No one prisoner knew what the other had confessed to. This will in some measure account for the discrepancies which appear in the confessions. In all cases it was the purpose of the writer to get the truth, and with that view he, at every sitting not only endeavored to impress upon them the solemnity of their situation, but also the fearful consequences of uttering a falsehood. He further endeavored by repeated questions, by recurring again and again to different and disconnected parts of their narrations, to sift, as far as practicable the correctness of their stories. He cannot say that his efforts have been entirely successful; but wherever he could find anything in their statements or their manner of relating them to justify a belief that they were untrue, he endeavored to exclude them from the confession. His effort has been to take down their confessions as far as practicable in their own words, and with this view he has avoided every thing like embellishment and all attempt to dilate. The opening and conclusions are theirs in sentiment and nearly the only parts in which the writer has assumed any liberty in the employment of language. Desiring that so far as the writer was concerned, the confessions might be faithful narrations of their lives he has been compelled to admit of subjects and expressions which delicacy and his own feelings prompted him to exclude. But being part of their stories, of the truth of which he had no reason to doubt and in some instances too much cause to believe, he did not feel at liberty to omit them. In the names of persons and places many errors have doubtless been committed, as in some cases the pronunciation was such as conveyed no correct idea of the real name.

Each confession has been read several times in the presence of the jailor and other respectable persons, to the prisoner making it, and all corrections made which from time to time the prisoner's recollection suggested, until his full and entire assent was given to every part.

In conclusion the writer begs leave to remark, that in suppressing names as he has, in some cases, he has been actuated by a desire not to injure any one upon the testimony of persons of color and in the condition of these convicts. He does not pretend to endorse the truth of any part of their statements, but only to say, that the foregoing is a true report of their several confessions.

A. B. CHAMBERS.

GEORGE H. C. MELODY, Jailor.

Page [iii]

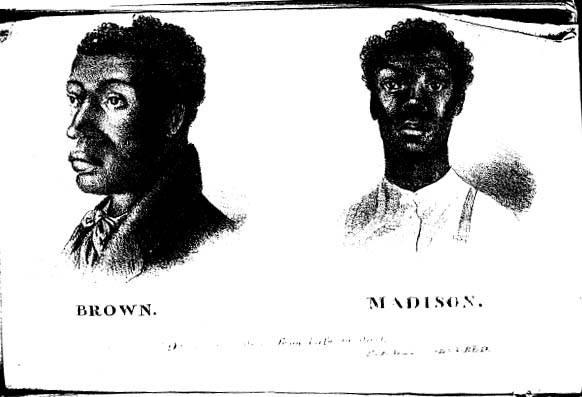

BROWN.

MADISON.

Drawn on Stone from Life in Jail. Copyright Secured.

Page [iv]

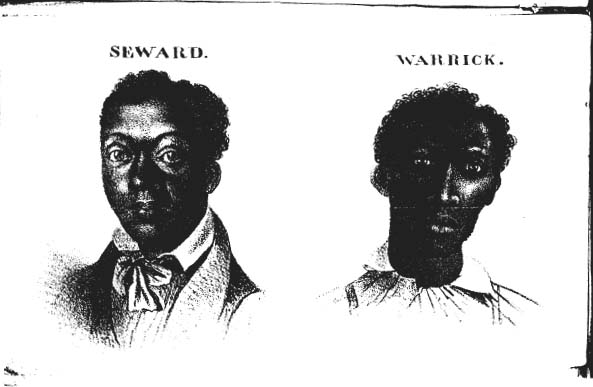

SEWARD.

WARRICK.

Page 1

MURDER, BURGLARY AND ARSON.

From the Missouri Republican of April 19th, 1841.

We have never before had occasion to record such a complication of crimes in a single transaction, as was presented to our appalled citizens on the night of Saturday last. About one o'clock the alarm of fire was given by the flames bursting out of the windows and various parts of the large stone store on the corner of Pine and Water sts.; the front on Water street occupied by Messrs. Simonds & Morrison, and the rear by Mr. Pettus as a banking house, formerly Collier & Pettus. At the time of the discovery, it was evident that the building had been fired in several parts, and the flames had made such progress that it was impossible to save either the house or any of its contents.

That it was the work of an incendiary was soon apparent. Several gentlemen who arrived early, after some difficulty forced open the door of the banking house, and through the smoke discovered a body lying on the floor near the stove. The body was taken out before the flames reached it, and found to be that of Mr. JACOB WEAVER, a young man, a clerk in the store of Messrs. Von Phul & McGill, who usually slept in the room immediately in the rear of Mr. Pettus' banking room, with Mr. JESSE BAKER, the clerk of Messrs. Simonds & Morrison. Mr. Weaver was found in the dress he had worn during the day, but his head dreadfully mangled. He had been shot through the head, the ball entering above the left eye, and so near had the weapon been to him, that his face and left hand were blackened with the powder, and the little finger nearly cut off, apparently by the ball. His head was also cut open in several places, the wounds appearing to have been made with a bowie knife or hatchet.

Near to him, in the same room, was found the hat and handkerchief of Mr. Baker, but no trace of his body could be discovered. It is conjectured that he had been killed either in the bed room or some other part of the store, and that his body lies buried in the ruins.

In the banking house there was a large fire proof vault, in which there is at all times a large sum of money, and it is supposed that the murder was committed with a view of entering that vault. Of the manner, however, there is nothing but conjecture. Mr. Baker left his boarding house about nine o'clock for the store, and has not been seen since. Mr. Weaver was in company with a number of young gentlemen at a ten-pin-alley, until about 11 o'clock, when he went to the store, and about the time he arrived, the report of two pistols or guns were heard in that direction by the people in the vicinity, but from the reprehensible frequency of such reports, excited no attention. Some suppose the murderers had concealed themselves in the store, and had previously despatched Baker, and killed Weaver when he entered. Our own belief, from all the circumstances, is, that they entered with Weaver, and that the struggle and death of both followed immediately. After the murder, they doubtless fired the house in several places with the hopes of consuming the bodies, and in the expectation that their crime would not be discovered.

So far as there has been any means of judging, it is believed that the murderers failed in their principal purpose, that of entering the vault. Owing to the heat, up to a late hour yesterday, the door could not be approached, but when it was, it was found to be locked,

Page 2

and could not be unlocked. The safe of Messrs. Simonds & Morrison, in which there was some money, was undisturbed, and it was therefore probable that but little booty was obtained.

The loss by the fire has been very great. Mr. Pettus lost all his books and the books of Collier & Pettus.--He, however, after three attempts, at great personal risk, succeeded in getting out a drawer under the counter, in which were all his bills receivable, amounting to near $200,000, the papers being very little injured. Most of the books and papers of the late firm of Hempstead & Beebe were destroyed, and Mr. Hempstead's desk.

Messrs. Simonds & Morrison lost their journal and ledger, but saved several other books. Their safe was dragged out, and the papers in it preserved with little damage. Their entire stock of goods, however, was consumed. Their loss, including their own stock and the goods on storage and commission, is estimated at about $30,000, which is probably below the amount. They were covered by insurance to the extent of their own stock. The whole loss, including the goods and the building, may be set down at from 40 to $50,000.

From the house of Simonds & Morrison the fire extended south to the adjoining building, occupied by Messrs. Kennett, White & Co., the roof of which was partially consumed, and for a long time, we thought it impossible to save the building or the row; but the firemen of St. Louis are indomitable, and by an exertion, demanding of all the highest praise, the house of Messrs. Kennett, White & Co., was saved with the loss of the roof only. The goods in the store, however, were greatly damaged by the water, and the stock was very large. The amount of damage is variously estimated at from 10 to $15,000--fully covered by insurance.

The wind, setting in a southwest direction, carried the embers in great quantities over the buildings south of the fire, and nothing but the saturated conditions of the roofs by the previous rains and the exertions of the firemen saved the row.

The store of Mr. Bernard Pratte, on the opposite side of Pine street, was several times on fire, and some of the window frames were considerably burned, but by the exertions of those from within, and the aid of the engines, no injury was done the building, although Mr. Pratte's goods suffered considerable injury from the water.

We would rejoice to pause here in this sad recital, but there is yet a tale of woe to be told. About the break of day, the interior of the first building having all fallen in, Mr. ANSEL S. KIMBALL, first engineer of the Union Fire Company, was standing on the side walk on Pine street playing on the fire through a window, when the wall suddenly gave way and fell outwards into the street. A gentleman with him made his escape, but Kimball was caught and crushed beneath the falling mass. His remains in a few minutes were disinterred from the ruins, but the vital spark had fled.

Mr. KIMBALL was one of our interprising citizens, a carpenter by profession, and was one of the contractors in the erection of the Second Presbyterian church. He was of irreproachable character. He was born in Concord, N. H., and came to this city from Boston in the fall of 1836, and has carried on his trade under the firm of Kimball & Webster. His circumstances were moderate, in fact, embarrassed in the general embarrassment of the times. He has left a young and amiable wife to mourn his loss, a loss to her which no sympathy can repair, but for whose future comfort it is now the duty of our community to make a liberal provision. He, upon whom she lent for support and protection, has been cut down without a moment's warning and when laboring for the preservation of his neighbor's goods.

Mr. WEAVER was a young man, about 22 years of age, of excellent character and had the entire confidence of his employers and the esteem of all his

Page 3

acquaintances. His parents reside in the city, his father carries on the business of house painting, and is one of our most respectable and worthy citizens. He removed to this city about three years ago from Washington City, and doubtless prided himself on the promise of usefulness which his son gave, but the icy hand of death has destroyed the flower and crushed the parent's fond hopes.

Mr. BAKER was a young gentleman of about 22 years of age, the son of a respectable family, residing in Worcester county, Md, and a nephew of Mr. Jesse Lindell, of this city. For steadiness and propriety of conduct, he was a pattern, and it is nothing more than justice, to say, that there was not a worthier young man in our community. He has lived here a number of years, and from all with whom he became acquainted, won the applause due to rectitude and worth. He and Mr. Weaver were members of the St. Louis Fire Company.

It would be impossible to describe the intense feeling, which pervaded the community during the night and ensuing morning, and in fact, the whole day. Every one was shocked at the enormity and boldness of the deed, and felt, that whilst such crimes could be committed in our midst and the guilty escape detection, there was no security to any one. We live, indeed, in dangerous times when such damning crimes can be committed in the very heart of the city and the brutal authors go unhung and unwhipt of justice.

At an early hour in the morning without any previous call, a large number of the citizens assembled at the Old Market House, when the Mayor, John D. Daggett was called to the chair, and Geo. K. Budd, Esq, appointed Secretary, when the following proceedings were had:

WHEREAS, a foul and inhuman murder--together with arson--was perpetrated in our city last evening, by some person or persons unknown; and whereas, the perpetration of this-horrible outrage calls for the most prompt and efficient measures on the part of the citizens. Therefore, Resolved, That the Mayor be and he is hereby authorized and requested, without delay, to offer a reward in the sum of FIVE THOUSAND DOLLARS, for the detection and conviction of the perpetrators of the crime aforesaid.

Resolved, That a committee of twelve from each Ward, be appointed by the chair, to immediately take such measures as to them shall be deemed ex pedient to ferret out the murderer or murderers.

Resolved, That the corporation of the city of St. Louis be and is hereby requested to appropriate the amount of the aforesaid reward of $5000 to be paid on the arrest and conviction of the perpetrator or perpetrators of this horrible outrage and murder.

After the adjournment of the meeting the Mayor offered a reward of $5000 for the detection of the perpetrators and the St. Louis Fire Company offered a further reward of $300.

The city and country was patrolled during yesterday and last night, and the citizens generally are using all the means in their power to detect the guilty.

From the Republican of May 6th.

TWO OF THE MURDERERS

CAPTURED.

On Tuesday night, Messrs. John Atkinson and R. B. McDowell, who had gone up the Missouri in the Col. Woods in pursuit of Warrick, one of the murderers and incendiaries of the 17th u'lt., arrived at our wharf in the Omega, with the object of their pursuit, at about 12 o'clock. Warrick had left here in the Omega, and the Col. Woods met near Arrow Rock, where, being hailed from the Col. Woods she rounded to, and the boats came together. Messrs. McDowell and Atkinson immediately went on board the Omega, found their chap, promptly secured him, and then transferred their baggage to the Omega, and returned with their prisoner.

Page 4

He professed utter innocence in the whole matter, asserting that all his information was derived from Brown, one of the desperadoes yet at large. In other respects, his narration was pretty much the same as that given by Ennis, published in this paper a few days ago. He also stated that Madison and Brown were the burners of the Branch Bank at Galena. He gives his name as Alpheus Warrick.

James W. Seaward, another of the gang, was brought up yesterday morning in the Pre-Emption. He had left this city in the Atlanta; and Mr. Gordon, one of our efficient constables, who had left here in the Tartar, for the apprehension of Madison, on his arrival at Cairo, finding the Atlanta at the wharf, went on board, found Seaward, secured him, and immediately transferred him to the Pre-Emption and brought him up. He gives a similar account of the tragedy with the other two, acknowledging his own guilt, and implicating Ennis. He stated that he left Brown in Cincinnati on Thursday last, the 29th ult., and that the next day after the Atlanta left, he was to leave for New Orleans on another boat. Mr. Gordon engaged persons at Cairo to be upon the look-out for him, and secure him if he should come along. Mr. Gordon again returned yesterday on the Gen. Pratte for New Orleans, unless he should meet with Brown in custody at Cairo, in which case he will probably return with him. Seward lays the whole blame to Madison and Brown, as projectors, leaders, and chief executioners in the tragedy.--He also states that Madison had sworn or declared, that if discovered or informed upon, he would never be taken alive.

Some time ago, a burglary was committed upon the store of Sinclair Taylor & Co; and in possession of Seward was found several articles belonging to one of the firm. He says Madison and Brown committed that act, with an attempt to fire the building at the same time, and that about the same time they committed the burglary upon the store of E. & A. Tracy.

Justice now appears to stand a fair chance of being meted out to these miscreants and desperadoes. We look for the forthcoming of Madison by the return of the Meteor, and if Brown leaves Cincinnati according to intention, he will stand a good chance of making his appearance among us even before Madison. They now, all four, seem destined to pay the high penalty due to the violated laws.

From the Republican of May 10th.

THE APPREHENSION OF MADISON,

THE MURDERER.

The steamboat Eliza, which left New Orleans on the 2d inst., and prior to the arrival of the Oregon or Meteor, arrived at our port during Saturday night about 12 o'clock, having on board the slave of Mr. Blanchard, of New Orleans, called Madison, and who is accused of the Murder of Mr. Baker, in Mr. Pettus' store on the night of the 17th ult.

We are authorized by Capt. Littleton to state the following, viz: the facts of his coming here, and his arrest.

Madison came on board as passenger, with a note from Blanchard, his master, desiring Capt. Littleton to bring him to St. Louis, stating that he (Blanchard) would pay his passage. In a conversation with the Captain, Mr. Blanchard said that he wished to keep his slave out of the way, in consequence of some difficulty which had occurred in New Orleans, and to prevent his being put in prison there.--At Memphis, Capt. Littleton had some intimation that negroes were concerned in the bloody work, but no names were mentioned. On his arrival at Commerce, the particulars were detailed to him, and the fact that Madison was concerned. This information was imparted only to the Clerk, intending to arrest the negro as soon as they arrived in port. Capt. Littleton set a guard to watch the negro--then asleep on the deck--and sent for the Police Officers, by a young man in R. H. Stone's store. Mr. R. Dowling (a deputy marshal) and Mr. John Lux

Page 5

soon appeared; Madison was pointed out to them by the Captain; they tied him and took him to jail.

We are authorized by Mr. Littleton to say, that so far as he is concerned, he declines to receive any reward for this arrest--being abundantly satisfied with the consciousness of having done his duty to society.

From the Republican of May 12.

THE LAST OF THE MURDERERS

TAKEN.

Yesterday morning Mr. Miller of Alton, and Mr. Farish of this city, accompanied by one of the Cincinnati police, arrived on board the steam boat Express with Brown. Notice having previously been given that he was on board the boat, an immense concourse of people collected on the wharf. The officers who had him in charge, managed it so as to get him off and some distance on the way to the jail, before the crowd discovered them. By the time they had arrived at the jail several thousand were present, and although there were many deep murmurs uttered, yet no attempt at violence was offered.

Brown was yesterday brought before the Criminal Court and arraigned on both indictments, to which he plead not guilty. The Court then assigned JOHN F. DARBY, Esq, formerly Mayor of the city, as his counsel, and he was remanded to jail where he was securely ironed and lodged in an apartment separate from the others.

The character and high standing of the counsel whom the court have assingned for the criminals, embracing the head of the profession, and all being gentlemen of distinguished worth as citizens, should be to all a sufficient evidence that the accused will have a fair trial and the full benefit of the law. The testimony will be fairly submitted and passed upon, and it is a matter which should be received as a strong evidence of the moral feeling of this community, that no objections are made to the course which the court has pursued. It is, however, highly desirable that their trial should be had at as early a day as will be compatible with a full and fair investigation. Until this is over, the feverish feeling pervading the community will not subside, accidental or unforeseen causes might call forth that feeling, which is now only repressed by a consciousness that the law will be fully executed.

ST. LOUIS CRIMINAL COURT, May 24th, 1841,

BEFORE JUDGE BOWLIN.

STATE VS. MADISON ALIAS BLANCHARD.

Circuit Attorney John Beat. For the prisoner, Wilson Primm. Esq. The following jury was empannelled and sworn:

JURORS--Daniel D. Page, David Chambers, Joseph Wallon, David Shepherd Ephraim Carter, Martin Wash, Ruberdeau Annan, George W. Berkley, Elisha Patterson, John Stagg, James W. Doughty, John Winright.

Indictment read by Bent, Prosecuting Attorney.--Edward H. Ennis sworn on the part of the State.

All I know of the matter is derived from prisoner and the others. On the night of the 17th April, I had worked at my shop until 10 at night, when shut up shop, went from there to my lodgings at P. Charleville's--he let me in, I went to bed immediately, had been asleep until half past 10 to 11, when defendant came and knocked at door, I got up and let him in, he entered and his first remark was, God d--n the luck--I said why, what's the matter now? he replied he had done more murder that night than he had ever done and had not been paid for it;--I asked where he had been, he said he, Seward, Brown and Warrick had that evening been down at Coller's counting room and that the door was unlocked, that he went in and presented a bank bill to the gentleman who was sitting or standing near the stove, and while he was looking at the bill, he struck him with a bar of iron on the head, as soon as he struck him the other three came in, the blows were followed up until he died, the top of his head was beaten off--after he was dead the body was searched for the keys of the vault, not finding the keys the body was rolled up and laid in bed clothes in bed;--after that they endeavored to open the vault, and continued at it until the other gentleman came. (The man killed was not named by him) He rapped at door and some contention arose as to who should kill the gentleman.--The dispute was ended by M.'s saying that he had done his share by killing one and that he did not intend to kill any more He, Warrick and Seward then secreted themselves, Brown stood behind the door, opened it, and as the gentleman came in struck him, knocked him down and followed up the blows until the gentleman died. Madison left very soon after, did not stay long. When the alarm of fire was given, I got up and went to the fire;--there the general rumor was that Weaver was shot;--I staid at the fire until near 3 o'clock,--when I got home there was a light in Peter's room,--I there saw the crow-bar which Blanchard said he had need that night,--I took it up and threw it in the vault rear of the house,--that night or next morning I asked Madison in regard to two pistols having been fired, he said no pistols had been fired by either of them. The iron bar was a small one about 18 inches long,--I think the bar shown me in court is the one,--I think there was blood on the bar,--Madison boarded at Peter's at that time.

Cross Examined--I was examined at the Mayor's office by the Mayor, who reduced my examination to,

Page 6

writing; I am a barber and have been working with G. Johnson on Market street; Madison is no barber, he and myself boarded and lodged at Peter's house for some considerable time; we slept in the same room and bed; he used to come sometimes to the shop to call me to my meals; we were merely together as boarders and were not in the habit of confiding our secrets to each other, we had none to confide; neither of us married; never confided to each other our courting scrapes; Blanchard was not at my shop during that day; I don't recollect seeing him from breakfast till he came in that night; I was at dinner and supper and did not see Madison; I saw him at breakfast; I don't recollect seeing any person there at supper except Peter's wife; Mary Beaufils was not in the house that I know of.

M. did not appear to be drunk--there was no light in our room, but the middle door was open and I could see the light from Peter's. P. and wife were in their room in bed, but whether awake or not I cant say. M. had a cap on when he came in, had boots, gray pants and blue box coat. When Peter and I went to the fire we left M. in Peter's room by the fire--he had his boots, coat and cap off--I went to bed and lay awake until the alarm of fire, M. did not go to bed--M. and I did not have a long talk together, cant say the tone of voice in which he spoke when he came in--I wont be positive whether there was the light of a fire or candle in Peter's room. The fuel used was wood. I saw M. with crow-bar when he first came in the house and he then said that he had done the act with it. I am positive there was blood on it. I saw M. in bed when I came home from the fire; I dont know whether he was asleep. I did not caution M. to speak low when he stated these facts to me. I had never had any communication with any of the defendants about any project they may have entertained. I took the crow-bar myself and threw it away when I came from fire--I made the same statement before the mayor. Think I saw M. at breakfast and in the street on Sunday. I had conversation with all of them at Peter's house on Monday.

RE-EXAMINED. The coat produced is the one M had on that night. By juror--I threw the bar away because I was afraid that M. might have communicated the matter and have brought me into difficulty.

Le [illegible] Charleville. I know nothing of this murder; I know the night when fire occured. M. boarded with me, so did Ennis, E. was at my house in bed; he was at supper; M. was not at supper. Ennis came home about 10. I was in bed when he came home, he went to bed directly. M. came home about 11 or 12. I heard him say something when he came in but dont know what.--No light in house; no candle lighted until the cry of fire. Have seen the coat; it is Madison's; night of fire he had coat on; din'nt see him with it on after that night; Mr. Gordon got it from my house; I think there was blood on the skirt of it. Know nothing of bar.

Cross Examined.--Was in bed when Ennis came home. Had'nt much fire that night. Peter blew out the candle when Ennis came. M. woke us up by his knocking at the door. Ennis asked who it was and M. said Blanchard. Madison went to bed with Ennis. I dont think it was light enough for me to see in my room. I dont recollect any long conversation between E. and M. E. and Peter went to fire. M. staid in bed. M. did not go into my room and sit down by the fire. P. came back first--he, Ennis came into my room, pulled off his boots and talked of the fire--he pulled off his clothes in my room; he did'nt remain long, he went into his room and went to bed. I lay awake after that--I heard E. and M. talking but dont know what they said.

M. was at breakfast the next morning, and at dinner, I don't remember whether at supper--M. had a calico shirt, gray pantaloons and a cap--M. and Ennis had no great deal to say to each other--he eat breakfast and dinner at my house on Saturday--he didn't put the coat on Sunday morning--it lay on the bed, it was hanging on the middle door when Mr. Gordon came in--I never saw blood on it until after Gordon left--M. told me to send the coat to Patsey Evans to have it mended--his behaviour at breakfast was as usual, I saw nothing wrong M. left for N. Orleans on the Missouri, on Tuesday or Wednesday.

On Saturday we eat supper before dark, to enable E. to go to work--M. left my house before sundown.

Francis J. Parker. Recollects night of fire, knows Ennis, was at his shop until 10 o'clock, and Ennis was there.

Peter Charleville. Knows E. and M., recollects night of fire--M and E. boarded at my house--M. left my house immediately after supper, and came back between 10 and 11 at night. He didn't eat supper at my house that night--Ennis did, and came back about 10 and went to bed immediately. E. let M. in--heard them talk, but don't know what they said--I went to the fire with Ennis--M. was then in bed, and didn't say any thing about going to the fire. Knows the coat, it is M's--I think he had it on that night--never since. When I heard the cry of fire I said it was a darn'd shame that people's property should be burnt up so. He (M.) answered what the hell is it to you. Have you any property there, or down there? I understood the latter. In the morning M. asked me where the fire was, I said the house of Simonds & Morrison--he asked if it had burnt much--I answered it had burnt that house and all the property in it--then he said it didn't burn down to the old man's house, and I said no--meaning his master's property where Tatum lives. He said it was good for me that I had got caught in the smoke, I had no business there--never saw the bar.

Cross-ex--When M. came home no light in my room, and door shut--and no light in his room. I heard M. come in--I did not get up nor my wife--we staid in bed. I didn't hear him say a word that I could distinguish. I could not have seen any thing on the other side of the room that night--I am positive that M. was not in my room when I started for the fire--he was in bed. I came back first--M. was still in bed--I dont remember E's. coming back. When I left for Cincinnati the coat was on the door.

James Gordon. I took the coat from Leah's house. E. told me that the bar had been thrown by him into the privy, and there I found it.

Carson.--Knew Baker, saw his body after it was taken to Blow's store--the head was nearly all burnt off--lower part of his body was not--except toes and one of his hands, also his breast. His coat and pantaloons burnt--I could recognize them. There was nothing else round him. It was the front part of his head that remained unburnt.

James Sykes.--Examined Baker in Blow's store. Head burnt off except back part.

Two cuts across the breast, as if done by a sharp instrument.

Edward Bredell. Knew Baker, body found in the ruins--saw it taken out on Monday morning.

Mr. Primm on behalf of the prisoner addressed the jury. Mr. Bent followed in reply, when the case was submitted, and after a brief absence the jury returned into court a verdict of "GUILTY OF MURDER IN THE FIRST DEGREE."

ST. LOUIS CRIMINAL COURT, May 25th, 1841

BEFORE JUDGE BOWLIN.

STATE OF MISSOURI vs CHARLES BROWN.

Indictment for Murder. The following jurors were empannelled and sworn, viz:

JURORS--John F. A. Sanford, Joseph H. White, Dalzoll Smith, Samuel Peake, William H. Harshaw, William P. Harrison, George G Presbury, William A. Bransford, Charles Cho [illegible] teau, Edward Xaupi, John M. Massey, Ellis Wainright.

Indictment read by J. Bent, Circuit Attorney.

Edward H. Ennis sworn on the part of the State says, either on Sunday or Monday, but I rather think it

Page 7

was on Monday, after the fire, I saw Brown, Warrick and Madison together; I think they were all together; I think they were at Leah's house if I mistake not; I there had some conversation with them; I think it was in the bed room which was occupied by Blanchard and myself, but I will not say for certain whether it was there or down stairs. I there commenced the conversation about the fire, but I cannot state how. I believe it was in that conversation that I asked Brown, in regard to the pistols having been fired, (the pistols that it was rumored had been used when Mr. Weaver had been shot,) told me there had been no pistols used, same as Madison had done; he said that he himself, when the gentleman rapped at the door, opened the door for him, and as he came in he struck him. I have no recollection of what he said he struck him with, and that the blows were followed up on the gentleman until he was killed; whether he said any of them assisted him or not I can not pretend to say, I do not recollect whether he named the gentleman who was killed or not; I think he said there had been one killed before--killed by Madison. I dont think he mamed either of the gentleman killed. I think he told me they did not stay there long after Mr. Weaver came in, the last gentleman who was killed. He further said that before he left he had fired the house in five different places. Brown said he took away with him when he went a blue cloth cloak and a gold watch. He described the chain to me, but I have forgot the exact description. He then came out and locked the door, went up the alley, north from the store, I suppose it is, and in going up that alley threw away the key of the door. I think that is about all, as far as I can recollect. Brown did not state how long it was before he left the building, or the his accomplices left the building. I can give no description on the watch chain, but I think it was a black guard chain.

The whole of this conversation related to a conversation that I had previously had with Madison, about the commencement of this whole matter, the killing of the two men and the burning of the house. This was the Monday after the fire, and in the forepart of the day. I did not know either of the persons said to be killed. Brown might have said something about using instruments and the manner of killing, but I do not recollect it. Madison said something about the blow being given over the eye; but whether Brown was present or not I do not recollect; can not recollect any thing that was said about the instruments that were used. Brown said he struck him and followed up the blows till he was killed.

Whether Brown knew that Blanchard had told me, or whether I told him that Blanchard had told me, in my introduction of the matter to Brown I will not pretend to say; I rather think I did not tell Brown what Blanchard had told me. I think we were sitting in my room, on the bed in which Madison and I slept; that I commenced the conversation by alluding to the pistols, with Brown. I have as far as I can recollect, stated what I said to Brown, and what Brown's reply to me was.--Madison said that as they were giving the blows, Weaver threw up his hand to his forehead, to shield off the blows, and that it was by that that his finger was nearly cut off. I think Brown was present at this conversation.

Cross-Ex.--I saw Brown first, here in the city of St. Louis. The first time I saw him was about three months back from this time--he came to the house (Leah's house) to see Madison, was where I first become acquainted with him. Some time in the winter, I am not certain about time, I became acquainted with him by seeing him at the house where I boarded, with Madison. Madison did not introduce me to him; he came to the house some three or four times before I become acquainted with his name at all. I have been here off and on since 1833. I have no license to stay here from the county court. I was taken up before you (the Mayor,) last summer and ordered to go away. I was fined last summer and went away, and came back last fall to attend court; Mr. Nabb took an appeal from the Mayor's court for me and wrote on to Maryland to get some documents from there. I am a Barber by trade, and have followed that trade in this town at the shop of George Johnson, on Market street, opposite the National Hotel. I do not know of any trade that Brown followed--I know nothing of his trade at all. Brown staid at Leah's a few days, and where else, I do not know. He told me he generally followed the river, a steam boat man Brown came to the room occupied by me and Madison in the upper part of Leah's house, and could not get into her house without coming through that room. Our meeting at Leah's house on Monday morning was accidental, and without concert--whether they went there first, or whether I met them there at breakfast, I cannot state. I cannot state whether that was the first time I had seen Brown after the fire or not; I might have seen him on the street, or somewhere else; it was the first time as far as I can recollect. Brown was not at Leah's on Saturday night, to my knowledge he was not there at supper. Brown had boarded there a few days, but had left some time previous to that--I think it was on Monday morning I saw Brown. Madison told me of the burning and death on Saturday night--I did not go to see Brown about it.

I think it was up stairs in Leah's house, that I had this conversation with Brown. I cannot state that I had any other conversation with Brown after that, I might, and I might not have recollected the conversation. Brown said he threw the cloak away; he did not say where he threw it. He said he threw it away for fear it might be seen or known. I think he told me two different stories about the watch--in the first, whether he said he himself had mashed up the watch or had given it to Warrick to mash up. I cannot pretend to be positive; I rather think that he had given up to Warrick. The other story was, that he had thrown it away. I never saw the watch to my knowledge. He said it was a gold watch. Brown said that he went and stood behind the door and knocked the second gentleman down as he came. No recollection of what he said he knocked him down with. He said nothing about any apprehension of his being taken up at the time; and did not enjoin secrecy on me. I think I commenced the conversation with Brown about the murder--I do not know how I commenced the subject; or how it was broached--cant say that Brown was agitated or was not. I expressed some apprehension to Butcher from associating with such folks. I conversed with Butcher on the following Friday; as to the course I should take--and it was on the conversation which I had with Brown at Leah's house, that he gave me the confirmation of what I had heard from Madison. He mentioned nothing about any instrument used, in killing Mr. Weaver; and told me he had followed up the blows until Mr. Weaver was killed. Never had been intimate with Brown. Three of them, Madison, Brown and Sewall, were there on Monday, at Leah's house, Peter was not there that I knew of Leah was in her room. He told me he stood behind the door, and knocked the young man down as he came in, and followed up the blows until he was dead.

I cannot say the month or time when Brown went away; I believe he was absent; Brown did not tell him he was going away; I saw Brown there at Leah[']s house, after the conversation I had with him on Monday, and saw him in the street after that; I do not know whether I had any conversation with Brown after that or not; Brown told me he was going away, and was going to Cincinnati to see his family; he stayed here two or three days after the burning of the house; Brown had not communicated any of his affairs to me; I did not mention the fact to Brown of my having thrown the crow-bar into the pit; Leah could not have heard our conversation, I think, as the door was shut.

Nancy McKee.--Lawful age, being duly sworn on her oath, states that the key here now shown to her, was found by her in the alley east of Pine street house, on Sunday evening after dinner.

Augustin Kennerly states that this key was handed to him by Mrs. McKee, on Sunday evening, after

Page 8

the fire, saying she had found it in the alley east of Pine street, and had given it to Mr. Pettus the same evening, near the corner of Pine and Main streets.

William Anderson states that the key now shown here to him was the key of the counting house of Collier and Pettus, and he has carried it a many a time; and there was another key just like it; no other keys about the house more like it.

Thomas Ellsworth states that he knew Jacob Weaver, and he helped carry him home on Sunday morning; he went to open the Sunday school on Sunday morning in the Unitarian church, and saw them carrying him home and went up with them; he saw Mr. Weaver in at Mr. Blow's; he did not examine him as particularly as he did at his father's house, after he was laid out. He says two wounds on this side of the centre of his head, and he could not say but what there was a ball. He could not say that the scull was broken, in the blow across the top of his head; there was another wound across the back of his head, which was the largest wound there was, there was another wound over the right eye, splitting the bone over the eyebrow.

George Collier says he knew Jacob Weaver was killed in his house; at the time of the fire and soon after getting on the ground, I saw them bringing out a body, from the store and take it up the hill and received into Mr. Blow's store, which body he examined and found it to be Mr. Weaver's. Had not seen Mr. Weaver for several days; before that he had been absent; I examined the wounds; they appeared to be scratches; there was a large wound on the back of the head; one in the eye, which I look to be a pistol shot.

William Morrison says he knew Jacob Weaver, and had seen him two days before that.

For the Prisoner.--John B. Meacham sworn.--Does not know the prisoner.

Robert Wilkinson; I have known Brown, for two for three years, had known him on a boat, on the river; Brown passed up up Vine Street, about the last of February of first of March; have not seen him since the last of March.

Jerimah Burros--Says he knew Brown the prisoner, at a shop, kept by Alford, where he shaved; the shop was on the corner of Tenth street and Franklin Avenue; the building belonged to deponent; Alford rented the shop of him; a German lived in the same house at the time, adjoining the shop, and lives now in O'Fallon's addition; I shaved on Sunday, in Alford's shop, after the fire; it was between nine and ten o'clock, I did not see Brown there to my knowledge.

Cross Examined.--I heard some one say that Alford was concerned in the affair, since the secret came out; he has shaved me twice since.

Leah--Says Brown was at her house twice after the fire; he was there on Sunday morning and asked for Blanchard, I told him Blanchard was in the house and he called him out; Brown was at my house on Monday morning; on Monday, when they were there they were all in the same room together; some two or three of them. Leah spoke to Brown on Sunday morning and asked him if it was not dreadful destruction, and he said it was. Never saw Brown until late this spring in her life, and then he came to her house; went up the river with Madison.. He did not board at her house at the time of the fire; they were talking in the room on Monday morning, they were talking in a low tone of voice, and the door was shut.

Cross Examined--Brown and Madison started and went to Bucher's from her house.

Philip Claus.--I see him every time in the Barber shop. He does not know any thing of him, except that he saw him in the Barber shop; but what his business was or where he was from he does not know. He lived adjoining the Barber shop; Barbershop is on Tenth street in this city, on or near Mr. Burros' lot. He lived at this house on the 17th April 1841 at the time of the fire at Collier & Pettus' store. He saw the negro between four and five o'clock on Sunday at the Barber shop. He did not see him on Saturday; he was out at work and did not see him there or any place else. There is about a four inch wall between the room he occupied and the Barber shop.

Edmond--I knew nothing of the fire and the murders that were committed here, on the 17th April. I left New Orleans on the 14th April, with Capt. Stiles. I did confess that I was one of the men who had been in the scrape here, but I was forced to do so, by being taken into a private room, in New Orleans.

John Bent, Circuit Attorney, then opened the case to the Jury.

J. F. Dathy addressed the Jury in behalf of the defendant; when Mr. Bent concluded the case.

The Jury retired for about five minutes, and brought in a verdict of GUILTY of murder in the first degree.

STATE vs. JAMES SEWARD, MAY 26th, 1841.

BEFORE JUDGE BOWLIN.

JURORS--Nathaniel Allison, Henry Pilkinton John Torode, E. C. White, Samuel Wiggins, George Henderson Laurison Riggs, D. M. Hammond, John Pritchett, James Waugh, Robert Depew, E. C. Carlton.

James Gordon. I arrested prisoner at the mouth of Ohio, and brought him up. He stated to me on our way up that Brown, Madison, and Warrick were the party when the murders were committed at Collier's house. He named persons killed, but I don't know that he said he knew them before. He named Baker and Weaver as the persons killed. He said that Brown had three days before the occurrence first made the proposition to him; afterwards he said they were all four together and arranged the plan how it was to be done--he said he was opposed to the killing or burning, but that Brown and Madson overruled him--and that on the night of the murder the four went to the place together--Madison went in alone and killed the first young man, whether he then named the name of Baker I dont remember--he said that Brown then went in with Madson--after some length of time he was walking up and down the street and walked at one time half way up the block on Front street, with the intention to go home, but recollecting that Warrick had the key he returned--when he came back he didn't see Warrick--suposed he was in some of the alleys--when he got near the house he saw a couple of young men coming down from Main street--before the young men got down opposite Mr. Collier's door one started across the street and the other kept down the street--the one who kept down the street passed right by him, the other went to the door of Mr. Collier's, pushed open the door and stepped in--as the young man stepped in he heard a blow given and the young man fell. The prisoner has since the first conversation I had with him told me that I mistook him in his first statement of his position--his first statement to me as I understood him, was that he was at the corner of the house opposite Mr. Collier's and at the alley--his second was that he was at the corner below--of Pine and Front streets. He said he was not any time in the house, and that shortly after the last young man went in he left the place & went home; he said that he was watching outside; the proposition to him by Brown was three days before the act. I dont remember where he said the plan was laid; did not know Weaver. His confession was made to me on the boat between here and the mouth of Ohio.

Cross examined--I started for New Orleans after Madison at the month of Ohio, finding I was on a slow boat, I determined to leave her and take the first fast boat that came down; soon after I stopped the Atalanta, came down and I went on board to learn where Seward had left her, as I had heard that he went away on board of her, inquired of the clerk if such a boy had left St. Louis on her, and he said there had, and that he was still on board. I found him and arrested him immediately; he was engaged in some

Page 9

capacity on board; was in the pantry when arrested. When I arrested him he did not appear to be cowed, but rather surprised; don't think I told him the cause for which I arrested him. I took him up to a public house at the mouth and confined him. We remained there about three or four hours. He was arrested about 9 o'clock in the evening, and we left about 1 or 2 in the morning. Left him in charge of two young men; while gone made confession; one of the young men from the boat, but neither from this place. The Missouri came into sight; they told him I had gone on her to catch Madison, said he would confess and hang the ballance. Seward was alarmed and wanted me called back, but they said I had gone too far; they told him it would do as well if told to any body. When I returned, I told him if he had any thing to say, to say it. He inquired if he told, if it would save him. I told him I could make no promise; what he told, must be voluntary. Was in my custody. When I went to eat, the captain and clerk watched him; lay in the Social Hall. The conversations were at different times, and at no one time were all the facts detailed. He appeared quite backward after he desired the conversation. In the first place I told him when he felt like conversation to let me know. Can't say whether the first was that night or next morning. Asked some questions. Appeared as if deceived when I returned. Think I mentioned to him if he hadn't told the other young men; he made no reply. He might have supposed I knew what he had told the young men. The conversation to me the same and the story told the young men. I had informed him that the matter was understood at home. Was steady in the denial of his being in Collier's house. Don't think he said the particular parts each one were to perform; said Brown was the head man in planning, and Madison chief in executing.--Stated it was Brown that killed Weaver. Understand that he didn't see it, but so stated the fact. Stated he was in the habit of sleeping in Warrick's shop.--Returned to get the key. Understood that he came immediately back after having gone half up the square and came up to the alley, was after the key. Don't think the killing had reference to any particular person, except the person in charge of the house. Am certain that he was anxious by exposing all to save himself. Didn't mention the names of the two young men as if he knew them. Didn't stay long after Weaver was killed. Stated nothing of any participation in any subsequent act. Think the last conversation in reference to this was on the morning before we arrived here. Can't say the precise language used, but it was such as to say plainly that his purpose was to watch and give the alarm if necessary.

George Collier gave the same testimony as in the case of Brown.

Edward H. Ennis. Think on the Monday after the fire that Seward was at Leah's house with B. and Mad. Think I was making some further enquiries of Brown about the murder. Dont recollect of Seward saying any thing about it. Dont recollect of Seward's name having ever been mentioned when he was present. Dont know that I ever had any conversation with Seward.

Mr. Gamble, on behalf of the prisoner, addresed the Jury, and urged that the confession had not been made without improper inducements, and therefore, the jury ought to disregard it. Mr. Bent replied and the case was submitted. The jury after an absence of about 10 minutes, returned into court a verdict of "GUILTY OF MURDER IN THE FIRST DEGREE; AS PRINCIPAL IN THE SECOND DEGREE."

CRIMINAL COURT, MAY 27th, 1841.

BEFORE JUDGE BOWLIN.

STATE, vs. ALFRED, alias, ALPHEUS WARRICK.

Indictment, as accessary to the murder of Jesse Baker.

The following jury was empannelled and sworn:

Hiram Cordell, Wm. Hare, A. W. Lockwood, John M. Arnest, Willis P. Coleman, Hosea Blossom, George Mead, Luther Cummings, Strother M. Burton, John S. Pearce, William Shrier, Henry Holmes.

Robert B. McDowell.--Knows the prisoner; it was 3d May, went up Missouri and took prisoner just below Arrow Rock; went up in pursuit of him; after he was taken there was nothing said to him for some time; he then commenced telling his becoming acquainted with Madison, Brown and Sewell; he had been more intimate with Madison and Brown than with Sewell; he commenced telling that he was at Burlington, and Madison and Brown were where he was, working at the Burlington House, being flush with money, having made a raise at Galena; he then came from Burlington and opened a Barber's shop in St. Louis. In the spring Brown and Madison returned also, and perhaps Sewell but don't recollect as to Sewell. They were in company three or four days before the fire at Collier's. He stated that at the night the deed was committed, they all four went on board the Missouri steamboat; when they came off from the boat they stopped at the corner of the store of Collier & Pettus in consultation, Brown, Sewell and Warrick were together at the corner of the street at about 9 o'clock. He then (at first conversation stated that he went away; Madison observed previous to that, they were going to make a big raise that night. Witness then asked him what weapons they used; he stated it was an iron bar. Witness asked him to describe it, and he did so; showing the length with his hands about 16 inches. Witness asked him if he (Warrick) was in the store of Collier & Pettus; he (Warrick) never having till then admitted that he had been in the house. He stated that he had not been in the house, but was on the look out. He then commenced stating to witness what Madison had told him. During the conversation he used the expression, "we were all there together, we were all in the house together." The next evening the Iatan came up, and witness got the Republican from her, and then told prisoner that there was a rumor in the paper relating to the matter, and at prisoner's request, witness read the piece in the paper to prisoner; and after he had concluded reading it, prisoner said every word of it was true. The conversation after that amounted to the same thing, breaking off, and conversing again at different places. On his way home on the night of fire, (prisoner stated to witness,) he stopped at Dr. Knox's and was with his colored people till between 11 and 12 o'clock; and then went to a widow lady that lives in one of Mr. Barrows' houses and borrowed a watch, that after he had got home, Brown and Sewell came and slept with him that night; that the next morning they all went down town; he said Madison killed Jesse Baker; and that he was not there in the house, but was out by the door; he said "we were all in," but not that he was; he did not say when the plan was arranged; but that they had been in company a few days previous. Madison observed to him when they were all together, that they would make a big raise that night. He stated there was another man (a white man,) present, but that he did not know his name; he did not say the white man had any thing to do with the plot.

Cross Examined--Prisoner was steward on board boat, and pouring coffee; witness came and prisoner seemed to suspect and turned away; witness came and took him by the hand, and prisoner asked what he came for; witness took him by the hand and led him to the cabin and tied him; witness did not tell him for what he came; when, 10 o'clock, after he was tied, he asked witness again and witness did not tell him; witness was then going out, when he returned he found prisoner telling what he knew about Madison, &c., to Atkinson, (John) who went up also to take prisoner; witness does not know how he came tell the affair to Atkinson; prisoner never talked to witness but once when there was any body present, and that was the time above mentioned; this immediately after he was taken and tied; witness never held out any inducements to prisoner; witness dont know what his motive was in making these disclosures; never intimated that he expected to gain any benefit

Page 10

from these disclosures; he was much affected when he began and was talking with Atkinson; he was much alarmed when witness took him; witness did not take him roughly, nor did not have to use any force; a little over 24 hours in coming down to St. Louis; witness talked with him not more than 2 or 3 times after he was put in irons, was restless all night; he was put in irons about 12 o'clock at night; no person said any thing to him more that night; the next day, the fore part of the day, witness read the Republican to him.

[Cross examination suspended; suspended to read the paper to him; newspaper shown to witness, who examined the piece.]

Examination in chief again--Says the newspaper shown him is of the same date, and the piece in it is the same read by him to the prisoner, and when witness got through reading it, prisoner said, every word is true. The paper is dated May 1st; the piece is headed, "The Tragedy of the night of the 17th."

Cross examined again as to the piece--Says thinks it is same; thinks he has lost the original paper; has not seen it lately; read the piece twice, once before it was read to the prisoner; was alone with him when he read it to prisoner; witness carried it in his hat, and is pretty positive he has used it up; but has not looked for it, as supposing a copy from the printing office would answer. [Objection made to reading the paper and overruled by the Court, decision of Court excepted to.] Bent, in chief, again reads the paper to the Jury.

Cross examined again--Prisoner, when witness read the paper to him, had been absent some 10 days; prisonor knew nothing of Ennis' disclosures when the paper was read, thinks prisoner was much agitated; but was in his right mind when the paper was read to him; he did not eat any supper that night; prisoner asked for gin several times, and witness gave it; had no conversation with him when paper was read to him; after it was read in his presence made the remark "it was true," and witness went out of the room; dont think that prisoner alluded to piece again, witness told prisoner that Ennis had disclosed at second conversation, and before the paper was read; prisoner swore at Madison when informed that Ennis had told; knows of no threat or inducement to prisoner to make him confess. Prisoner did not hint that he had any motive.

John Atkinson. Witness went up on Col. Woods and met Omega, (Capt. Littleton,) and went on board of her with McDowell, and found Warrick on board. Prisoner was arrested, tied and put in Social Hall; after he was there he asked what he was arrested for, and witness told him; then he wanted to tell about it and witness told him to stop, and would not let him speak about it till he had tied him; at a proper time after he was tied witness told him then to commence and tell what he had to say about it, when he commenced and said Madison, Brown and Sewell had left his house together the day of the fire; that that was the first he knew any thing about the plan, and they agreed to meet at dark on the steam boat Missouri at the foot of Pine street. They met accordingly, the four, at the steam boat, and spent some time in looking at engine and boilers, till between 8 and 9 o'clock; they then came off and stood on Water street, and some white man came there and took Madison out from among the company; he said he did not know the white man; he described him as being a tall young man, very well dressed and good looking; said he thought the white man knew what they were going about or he would not have been there at that time, but that he (prisoner) did not hear the conversation between Madison and the white man; they talked in a low tone. When the young man went away, that they walked up Pine street towards the upper part of the building; that he (Warrick) then thought better of it, and there left them and went home and said nothing further of it. Witness asked him if he knew any thing more about it.--He said he knew nothing but what Brown and Madison told him; that they told him all about it. He then related the minute particulars that occurred in the house from Madison and Brown's statement; that Madison killed Baker, and Brown struck Weaver the first blow though Madison and Sewell both struck afterwards; that after they killed Baker, they tried to get into the vault; that while they were working at vault, they heard some one come whistling down the street, and one of them said the little man was coming. Prisoner said he went home as soon as they come on Pine street, as he got his living honestly and that he went home to his shop, and was not present after Madison went into the house. He said Brown come to his shop about one o'clock and slept with him, and told him what had been done; said Brown was all wet and muddy.

Cross Examined.--This conversation commenced in social hall after he was tied; he said whom Brown was let into his shop, he (Brown) said there was a hell of a fire down town, and that this place would be as bad for fires as New York after a while. Witness helped seize him (Warrick;) witness and McDowell went different ways to the cabin; they both met at cabin door; witness walked forward and took him and did not see McDowell touch him at all till he was tied. Prisoner was in the cabin doing something; witness and McDowell entered cabin about same time; he wanted to commence telling story before he was tied; he was about 10 paces from the door facing entrance of witness; he did not appear to know witness; witness went up & caught hold of him and said he was his prisoner; he asked what for; witness told him he was arrested for murder and burning this house; he wanted to make a reply, and witness would not let him; witness would not let him go on with his tale, till the boats had got under way. When he was arrested he wanted to say something and wit. told him to shut his mouth and not to open it; in about half an hour wit. got some persons to take charge of him till he went to supper, and on his return he commenced telling the story. It commenced by witness saying to him to go on, relate all he knew about it; he was so frightened that he trembled when he was arrested; witness came to him after supper and simply remarked to go on and tell what he knew about the murder; don't know that prisoner was afraid of witness; witness was mild towards him; the boy was submissive as could be and made no resistance whatever; witness had frequent conversations with him on the way down; he always denied having any thing to do with it, except as above; thinks the prisoner was taken from social hall to state room opposite the wheel house before first conversation took place; at first conversation nobody was present except Kinney and perhaps his son; thinks McDowell did not come there before conversation concluded; wit. or McDowell was with him on the way down nearly all the time; sometimes he talked when McDowell and witness were there; expects he knew McDowell; witness was in no office nor McDowell; don't know what McDowell does; he is a wagon maker; no person engaged witness to go; the reward offered induced his going, though he believed he should have gone if none had been offered; some remarks were made as to reward between him and McDowell; neither knew at first what the other was after; nothing was said about it; reward of $5000 had been offered, and thinks it helped to make Mr. McDowell go; witness went on his own motive entirely; don't know that any body employed McDowell; can't say which was most with prisoner in coming down; saw McDowell reading the paper to prisoner; did not stay to hear it read; had himself read the paper before; talked with the prisoner after that once or twice; thinks it was about Boonville McDowell got the paper and read it to him; conversations generally begun by witness asking questions; prisoner got communicative after the first and answered freely; during first conversation witness was in a chair in state room, and Mr Kinney and son staid outside in cabin; witness staid 15 or 20 minutes, and when the conversation was through, witness went into cabin, shut the door and put a chair there and sat down, and remained there for some time, three quarrers of an hour;

Page 11

McDowell came then and said he had got irons ready and they then took the prisoner to a blacksmith's shop and put on hand cuffs, and then brought him up into the social hall and put on his shackles there, and then took him again to the state room; no conversation with him was had during all that time; he was put back into the berth about 11 o'clock; Mr McDowell then shut the door and laid his mattrass down against the door in the cabin; witness staid in the adjoining state room; knew of no other conversation with the prisoner that night and heard none; witness was separated only by their partition; dont know what prisoner's motive was in making these statements; he showed no reluctance; he stuck to it all the time, that he had no part in it; that he thought better of it and went home; has no reason at all to believe that he was under intimidation; witness had seen prisoner before, but was not acquainted with him.

Jeremiah Burros--Knows the prisoner; he lived on the corner of Franklin avenue and Tenth street, in witness' house, and was living there when he went away; he left on Friday or Saturday; witness saw him the last time on Thursday; he went away without giving notice. On the Thursday before the fire he said he would pay the rent, but said nothing about going away; prisoner said he expected to get money on Saturday. Witness shaved there; saw Brown there frequently, and saw two others there frequently; one a large man, the other a bright mulatto with high cheek bones; witness saw them on Sunday after the fire, and saw prisoner and another person come out of prisoner's shop and look at the procession. Found a piece of calico shirt in the cot prisoner slept on; dont know to whom it belonged; has frequently seen him wear calico shirts resembling this one; never heard Warrick say any thing about the shirt; there is an appearance of blood about the shirt; witness found the shirt after the rumor came out. On Friday witness went to get shaved and found that prisoner had gone; and the yellow fellow who was there said he would be back in a week; the yellow fellow took sick and said he would not carry on the shop, and gave key to witness, who found the shirt in the shop under the mattress next to the cot; supposed this yellow journeyman slept in that bed; was not there more than 2 or 3 days, or 3 or 4 days; don't know whether he staid there at all at night; never knew that Alfred bled at the nose.

Edward Bredell.--Testimony same as in the trial of Madison.

John Carson.--Knew Jesse Baker, saw his body after it was taken out of the ruins, in Blow's store; it was much burned; the head nearly all gone, the calves of the legs were white, not burned; Baker was in the habit of sleeping in room near counting room of Mr. Pettus, being same burnt down; was very intimate with Baker, and recognized his coat and pantaloons.

After the testimony had been gone through, Mr. Spalding addressed the jury at some length, urging that the contradictory statements of Warrick created a doubt whether he was actually there or not, at the time the murder was committed.

Mr. Bent followed in reply, and the case was submitted.

The jury, after an absence of about thirty minutes, returned into court a verdict of "GUILTY OF MURDER IN THE FIRST DEGREE, AS PRINCIPAL IN THE SECOND DEGREE."

THE CHARGE OF JUDGE BOWLIN

In passing sentence on the four negroes lately tried and convicted of the murders of the 17th April last.

MADISON alias BLANCHARD, CHARLES BROWN, JAMES SEWARD alias SEWELL, and ALFRED alias Alpheus Warrick, you stand convicted of willful, deliberate and premeditated murder: Have you now, or either of you, any thing to say why sentence of death should not be pronounced against you?

The prisoners, with the exception of Madison, who merely said, "Nothing from me, sir," remaining mute, His Honor proceeded--

You have all been severally indicted by a Grand Jury of the County, as follows:--You, Madison, for the murder of JESSE BAKER, and the rest as confederates, aiding and abetting in said murder; and you, Charles Brown, for the murder of JACOB WEAVER, and the rest as confederates, aiding and abetting in said murder.--Upon which charges, so preferred by the Grand Jury, you have been put separately upon your trials, before traverse Juries of the county. Juries selected in each case, with great caution, that they might be above all suspicion of bias or prejudice against you--and where you have been heard by your counsel--counsel amongst the ablest of the bar, in your defence. So that it is not a matter of form to tell you, that you have each had a fair and impartial trial before a Jury of your country, who have in their several verdicts, pronounced each of you guilty of murder in the first degree. You, Madison and Brown, as the persons who inflicted the fatal blows; and you, Seward and Warrick, as being present aiding and abetting in the several murders.

Upon these respective verdicts, it becomes the principal duty of the Court to pronounce the sentence of the law. But before doing so, as you were separately tried, and neither having heard the particular evidence given in the case of the other, it is but proper that there should be laid before you, a history of the case as derived from the testimony.

In doing this, it is not the object to awaken feelings by a recital of the horrid deed, or to bring unnecessarily to your minds painful recollections of the past--but it is solely with a view to place the nature of your crimes in such characters before you as to banish all hope of mercy from your fellow men, whose laws you have so daringly violated; and the more strongly rivet your attention, to that Source, alone, for consolation, where it is never too late to find mercy and forgiveness. The Court would not be discharging its duty to you with fidelity, in this last solemn act between you and it, if it could conceal from your knowledge, any thing of your true situation. To leave you buoyed up with a false hope, would be to deceive you. Hence it is deemed proper, that your crime should be placed before you, as it has made its impress upon the minds of men; that every false beacon of earthly hope may be distroyed, and you the more solemnly urged, to seek for peace and consolation at the Throne of Divine Mercy.

It, then, appears from the testimony in the case, that some three days before the ever-memorable night of the 17th of April, you had planned your scheme of robbing the Store House of Messrs. Collier and Pettus. At which time, it appears, some compunctious visitings of nature operated upon you, and a differance arose about adding the crime of blood, to the other contemplated offence. That the evil demon prevailed, and it was finally settled, that even blood should not arrest you, in the accomplishment of your crime. The next place you are traced, is at a meeting by appointment, in the dusk of the evening of Saturday, the 17th of April, on board the steamer Missouri, under pretence of examining her machinery. This was the meeting preparatory to the accomplishment of the crime. You left the boat, and stood on Front street opposite the house of Collier and Pettus--awaiting the arrival of the proper hour.--That at, or about 9 o'clock, in the evening, when the streets were lined with men, when every body nearly was up, when a person might have well felt the most perfect security in his counting room with open doors, on one of the most populous streets in the city, you entered the counting room, that is, you Madison, first entered, and asked of the young gentleman in charge, Jesse Baker, the validity of a Bank note; and

Page 12

while, in the honesty of his heart, and with that kindness of feeling for which he was conspicuous amongst his fellow man, he was performing an act of kindness for you, by examining the note, and he was thus placed off his guard, you struck the fatal blow which deprived him of life.

At this particular point of time, there is some contrariety in the evidence; but the better opinion is, upon the whole, that the rest of you immediately entered, at the signal of the blow. You searched your victim for the keys; not finding them, you wrapped him in bed clothes and deposited him in bed: and then went to work upon the vault, after perhaps setting one or two sentinels. That you continued to work upon the vault until Jacob Weaver, the bed companion of Baker, arrived, which was about the hour of 11 o'clock. That he knocked at the door, to awaken his friend, little dreaming that he was sleeping the sleep of death; when it appears, a difficulty arose about who should be his murderer. That horrid duty fell upon you, Charles Brown, and the manner of its execution was awfully deliniated in the appearance of the object. You took your station behind the door, the rest concealing themselves, and opened it for him--and as he entered felled him to the floor, repeating the blows until he was dead. Depriving of life in one moment a young man, who never harmed you, who was at once the pride and hope of his friends, and an ornament to society.

It appears, then, that despairing of success in your attempts upon the vault, you fired the building in five places, and left for your respective homes. You, Brown, being the last to leave, after closing the house, and throwing away the key--hoping, doubtless, by this last act, to bury in eternal oblivion all traces of the awful tragedy, and leave the world to hopeless conjecture, as to the fate of its unhappy inmates. In the burning, you succeeded but too well: you destroyed the whole property, but not in time to conceal the traces of your dreadful crime.

During the heart-rending scenes just recounted, the testimony places you, Seward and Warrick, in a variety of positions--sometimes in the house in the midst of the tragic scene, and then again on the look out, as sentinels to avoid surprise. In either situation, the law makes your offence just the same, in depravity and punishment, as though you had stricken the fatal blow. And justly so, for had you refused your co-operation, or had you made a timely retreat from it, the world might have been saved the recital of this awful tragedy and you the consequences resulting from it.

Shortly after, you all must have left the building--at about midnight, when the city was wrapped in profound repose, and men were dreaming in their fancied security--they were startled from their beds, with the terrible cry of fire. The citizens, with their usual alacrity, and with nerves braced for a contest with the devouring element, repaired to the scene--burst open the doors, and almost at the peril of their own lives, rushed in, and dragged forth the yet warm body of young Weaver, bearing upon it undeniable testimonials of the awful crime, that had been committed--a crime which, for daringness of design and boldness of execution, is almost without a parallel in this country. At the awful contemplation of the reality before them, men instinctively shrunk with terror from each other. They thought of the daring boldness of the crime, and of its perpetrators abroad in the land, and an instinctive shudder seized them at the thoughts of their unprotected homes.--Suspicion was abroad--and yet, ordinary perpetrators of crime, passed unscathed by its breath. The daring boldness of its execution, was a shield against suspicion to common offenders. Man knew not how to trust his fellow man. The bonds of society were well nigh sundered when, at a fortunate moment for the peace and security of persons and property and the supremacy of the laws, a conscience overburdened with a catalogue of crime, had to find vent, from the awful goadings of nature, by an open betrayal of the secret. A secret which has since received a mournful, but most undeniable confirmation.