REMINISCENCES

of School Life,

and Hints on

Teaching:

Electronic Edition.

Fanny Jackson-Coppin

Funding from the National

Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Aletha Andrew

Images scanned by

Aletha Andrew

Text encoded by

Bethany Ronnberg and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 350K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Call number 371.3 C795r 1913 (East Carolina College Library, Greenville, N.C.)

The electronic edition

is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American

South.

The transcribed copy

is from the East Carolina College Library, Greenville, N.C.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and '

respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as --

Indentation in lines

has not been

preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor

(SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

LC Subject Headings:

- Coppin, Fanny Jackson.

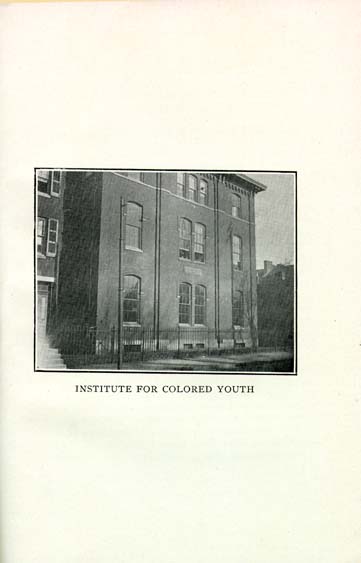

- Institute for Colored Youth (Philadelphia, Pa.) -- History.

- Teaching.

- Education -- Philosophy.

- Afro-Americans teachers -- Pennsylvania -- Philadelphia -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Education -- Pennsylvania -- Philadelphia.

- 1999-07-01,

Celine Noel and Sam McRae

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-05-28,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-05-26,

Bethany Ronnberg

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-04-13,

Aletha Andrew

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

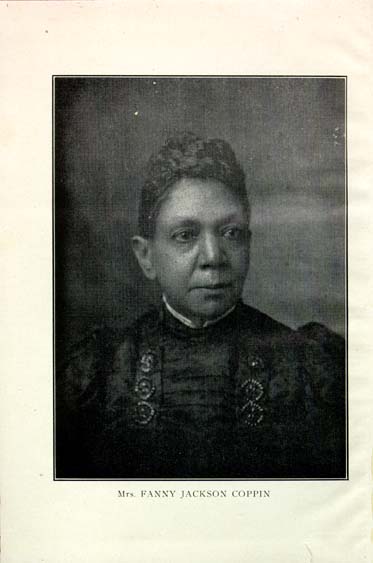

Mrs. FANNY JACKSON COPPIN

REMINISCENCES

of

School Life, and Hints

on Teaching

By

Fanny Jackson-Coppin

Philadelphia, Pa., U. S. A.

Page verso

Coppyright

L. J. Coppin

1913

Philadelphia. Pa.

A. M. E. Book Concern

631 Pine St.

Page 5

INSCRIPTION

THIS

BOOK IS INSCRIBED TO MY BELOVED AUNT

SARAH ORR CLARK

WHO, WORKING AT SIX DOLLARS A MONTH

SAVED ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-FIVE

DOLLARS, AND BOUGHT MY FREEDOM

Page 6

CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION.

- I. AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH . . . . . 9

- II. ELEMENTARY EDUCATION . . . . . 39

- III. METHODS OF INSTRUCTION . . . . . 44

- IV. DIAGNOSIS AND DISCIPLINE . . . . . 51

- V. OBJECT OF PUNISHMENT . . . . . 54

- VI. MORAL INSTRUCTION . . . . . 58

- VII. GOOD MANNERS . . . . . 63

- VIII. HOW TO TEACH READING AND SPELLING . . . . . 65

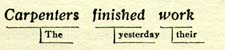

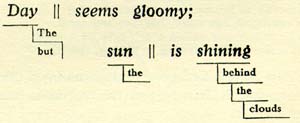

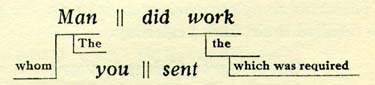

- IX. HOW TO TEACH GRAMMAR . . . . . 79

- X. HOW TO TEACH GEOGRAPHY . . . . . 91

- XI. POINTS IN ARITHMETIC . . . . . 102

- XII. MY VISIT TO ENGLAND . . . . . 115

- XIII. MY VISIT TO SOUTH AFRICA . . . . . 122

PART I.

- INTRODUCTION BY W. C. BOLIVAR . . . . . 137

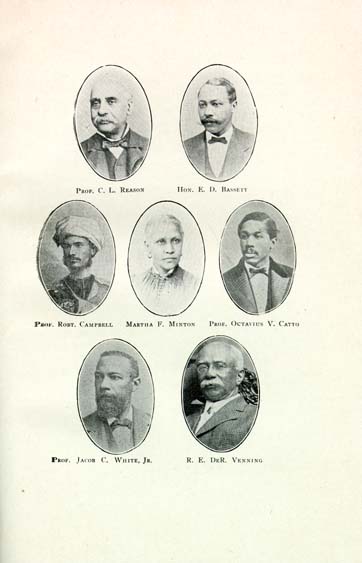

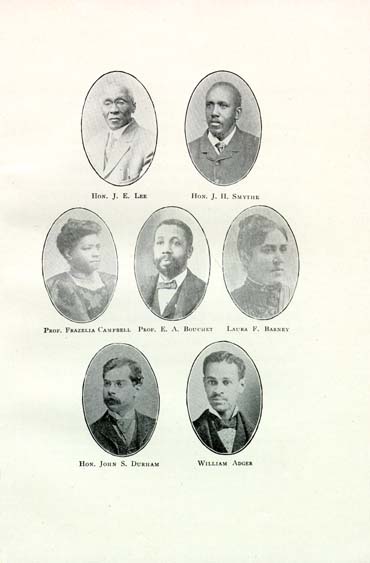

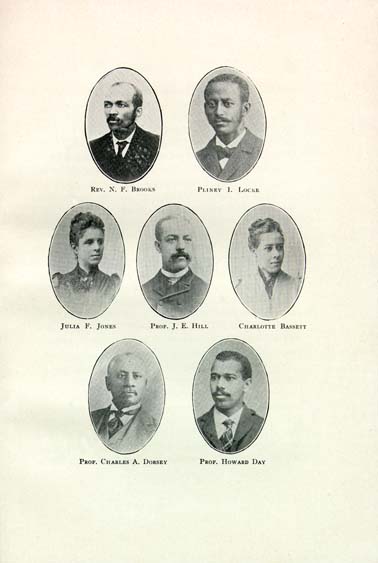

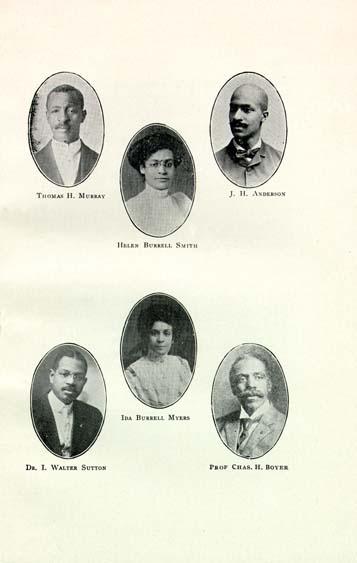

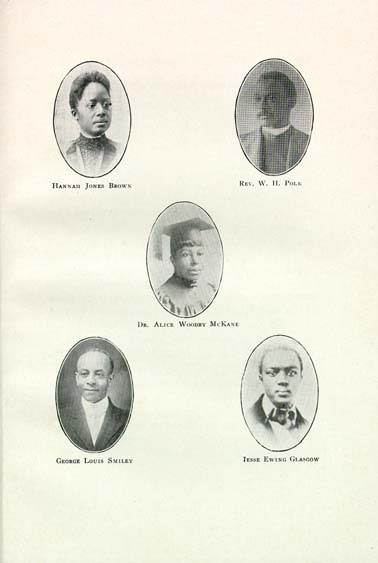

- TEACHERS, GRADUATES AND UNDER- GRADUATES OF THE INSTITUTE FOR COLORED YOUTH. (ILLUSTRATED.) . . . . . 139

Page 7

PART II.

Page 8

PREFACE.

THE author of this work was frequently urged by friends to write, for publication, something that would present a view of the writer's early life, as well as give some of her methods of imparting the intellectual and moral instruction that has proved so eminently successful in influencing and moulding so many lives.

After much persuasion, the work was begun, and carried forward to its present stage.

The final work of editing and directing its publication has fallen into other hands, and however inefficiently done, is a loving service, willingly performed, and sent forth with a hope that it may accomplish much good, especially in the way of inspiring those readers who are anxious to make the most of their opportunities.

L. J. COPPIN.

Page 9

PART I

I.

AUTOBIOGRAPHY: A SKETCH.

THERE are some few points in my life which, "some forlorn and shipwrecked brother seeing, may take heart again."

We used to call our grandmother "mammy," and one of my earliest recollections--I must have been about three years old--is, I was sent to keep my mammy company. It was in a little one-room cabin. We used to go up a ladder to the loft where we slept.

Mammy used to make a long prayer every night before going to bed; but not one word of all she said do I remember except the one word "offspring." She would ask God to bless her offspring. This word remained with me, for, I wondered what offspring meant.

Mammy had six children, three boys and three girls. One of these, Lucy, was my mother. Another one of them, Sarah, was purchased by my grandfather, who first saved money and bought himself, then four of his children. Sarah went to work at six dollars a

Page 10

month, saved one hundred and twenty-five dollars, and bought little Frances, having taken a great liking to her, for on account of my birth, my grandfather refused to buy my mother; and so I was left a slave in the District of Columbia, where I was born.

In my childhood, I had two severe burnings. I understand that at my christening the old folks gave a large party, and I was tied in a chair and placed near the stove. At night, when they took off my stocking, the whole skin from the side of the leg next the stove peeled off.

At another time, when mother was out at work for the day, mammy had charge of the baby. When mother returned, mammy exclaimed: "Here, Lucy, take your child, it's the crossest baby I ever saw." When I was undressed at night, it was found that a coal of fire from mammy's pipe had fallen into the baby's bosom, and had burned itself deep into the flesh. There were no Day Nurseries then.

Passing over years, I distinctly remember having chills and fever. Sometimes I would be taken with a shaking ague on the street, and would have to sit down upon a doorstep until I would stop shaking enough to go on my way. Then, I would have to go to bed, as I could not endure the fever and headache that would follow. When my aunt had finally saved up the hundred and twenty-five dollars, she bought me and sent me to New Bedford, Mass., where another aunt lived, who promised to get me a place to work for my board, and get a little education if I could. She put

Page 11

out to work, at a place where I was allowed to go to school when I was not at work. But I could not go on wash day, nor ironing day, nor cleaning day, and this interfered with my progress. There were no Hamptons, and no night schools then.

Finally, I found a chance to go to Newport with Mrs. Elizabeth Orr, an aunt by marriage, who offered me a home with her and a better chance at school. I went with her, but I was not satisfied to be a burden on her small resources. I was now fourteen years old, and felt that I ought to take care of myself. So I found a permanent place in the family of Mr. George H. Calvert, a great grandson of Lord Baltimore, who settled Maryland. His wife was Elizabeth Stuart, a descendant of Mary, Queen of Scots. Here I had one hour every other afternoon in the week to take some private lessons, which I did of Mrs. Little. After that, attended for a few months the public colored school which was taught by Mrs. Gavitt. I thus prepared myself to enter the examination for the Rhode Island State Normal School, under Dana P. Colburn; the school was then located at Bristol, R. I. Here, my eyes were first opened on the subject of teaching. I said to myself, is it possible that teaching can be made so interesting as this! But, having finished the course of study there, I felt that I had just begun to learn; and, hearing of Oberlin College, I made up my mind to try and get there. I had learned a little music while at Newport, and had mastered the elementary studies of the piano and guitar. My aunt in Washington still

Page 12

helped me, and I was able to pay my way to Oberlin, the course of study there being the same as that at Harvard College. Oberlin was then the only College in the United States where colored students were permitted to study.

The faculty did not forbid a woman to take the gentleman's course, but they did not advise it. There was plenty of Latin and Greek in it, and as much mathematics as one could shoulder. Now, I took a long breath and prepared for a delightful contest. All went smoothly until I was in the junior year in College. Then, one day, the Faculty sent for me--ominous request--and I was not slow in obeying it. It was a custom in Oberlin that forty students from the junior and senior classes were employed to teach the preparatory classes. As it was now time for the juniors to begin their work, the Faculty informed me that it was their purpose to give me a class, but I was to distinctly understand that if the pupils rebelled against my teaching, they did not intend to force it. Fortunately for my training at the normal school, and my own dear love of teaching, tho there was a little surprise on the faces of some when they came into the class, and saw the teacher, there were no signs of rebellion. The class went on increasing in numbers until it had to be divided, and I was given both divisions. One of the divisions ran up again, but the Faculty decided that I had as much as I could do, and it would not allow me to take any more work.

Page 13

When I was within a year of graduation, an application came from a Friends' school in Philadelphia for a colored woman who could teach Greek, Latin, and higher mathematics. The answer returned was: "We have the woman, but you must wait a year for her."

Then began a correspondence with Alfred Cope, a saintly character, who, having found out what my work in college was, teaching my classes in college, besides sixteen private music scholars, and keeping up my work in the senior class, immediately sent me a check for eighty dollars, which wonderfully lightened my burden as a poor student.

I shall never forget my obligation to Bishop Daniel A. Payne, of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, who gave me a scholarship of nine dollars a year upon entering Oberlin.

My obligation to the dear people of Oberlin can never be measured in words. When President Finney met a new student, his first words were: "Are you a Christian? and if not, why not?" He would follow you up with an intelligent persistence that could not be resisted, until the question was settled.

When I first went to Oberlin I boarded in what was known as the Ladies' Hall, and altho the food was good, yet, I think, that for lack of variety I began to run down in health. About this time I was invited to spend a few weeks in the family of Professor H. E. Peck, which ended in my staying a few years, until the independence of the Republic of Hayti was recognized,

Page 14

under President Lincoln, and Professor Peck was sent as the first U. S. Minister to that interesting country; then the family was broken up, and I was invited by Professor and Mrs. Charles H. Churchill to spend the remainder of my time, about six months, in their family. The influence upon my life in these two Christian homes, where I was regarded as an honored member of the family circle, was a potent factor in forming the character which was to stand the test of the new and strange conditions of my life in Philadelphia. I had been so long in Oberlin that I had forgotten about my color, but I was sharply reminded of it when, in a storm of rain, a Philadelphia street car conductor forbid my entering a car that did not have on it "for colored people," so I had to wait in the storm until one came in which colored people could ride. This was my first unpleasant experience in Philadelphia. Visiting Oberlin not long after my work began in Philadelphia, President Finney asked me how I was growing in grace; I told him that I was growing as fast as the American people would let me. When told of some of the conditions which were meeting me, he seemed to think it unspeakable.

At one time, at Mrs. Peck's, when we girls were sitting on the floor getting out our Greek, Miss Sutherland, from Maine, suddenly stopped, and, looking at me, said: "Fanny Jackson, were you ever a slave?" I said yes; and she burst into tears. Not another word was spoken by us. But those tears seemed to wipe out a little of what was wrong.

Page 15

I never rose to recite in my classes at Oberlin but I felt that I had the honor of the whole African race upon my shoulders. I felt that, should I fail, it would be ascribed to the fact that I was colored. At one time, when I had quite a signal triumph in Greek, the Professor of Greek concluded to visit the class in mathematics and see how we were getting along. I was particularly anxious to show him that I was as safe in mathematics as in Greek.

I, indeed, was more anxious, for I had always heard that my race was good in the languages, but stumbled when they came to mathematics. Now, I was always fond of a demonstration, and happened to get in the examination the very proposition that I was well acquainted with; and so went that day out of the class with flying colors.

I was elected class poet for the Class Day exercises, and have the kindest remembrance of the dear ones who were my classmates. I never can forget the courtesies of the three Wright brothers; of Professor Pond, of Dr. Lucien C. Warner, of Doctor Kincaid, the Chamberland girls, and others, who seemed determined that I should carry away from Oberlin nothing but most pleasant memories of my life there.

Recurring to my tendency to have shaking agues every fall and spring in Washington, I often used to tell my aunt that if she bought me according to my weight, she certainly had made a very poor bargain. For I was not only as slim as a match, but, as the Irishman said, I was as slim as two matches.

Page 16

While I was living with Mrs. Calvert at Newport, R. I., I went with her regularly to bathe in the ocean, and after this I never had any more shakes or chills. It was contrary to law for colored persons to bathe at the regular bathing hour, which was the only safe hour to go into the ocean, but, being in the employ of Mrs. Calvert, and going as her servant, I was not prohibited from taking the baths which proved so beneficial to me. She went and returned in her carriage.

After this I began to grow stronger, and take on flesh. Mrs. Calvert sometimes took me out to drive with her; this also helped me to get stronger.

Being very fond of music, my aunt gave me permission to hire a piano and have it at her house, and I used to go there and take lessons. But, in the course of time, it became noticeable to Mrs. Calvert that I was absent on Wednesdays at a certain hour, and that without permission. So, on one occasion, when I was absent, Mrs. Calvert inquired of the cook as to my whereabouts, and directed her to send me to her upon my return that I might give an explanation. When the cook informed me of what had transpired, I was very much afraid that something quite unpleasant awaited me. Upon being questioned, I told her the whole truth about the matter. I told Mrs. Calvert that I had been taking lessons for some time, and that I had already advanced far enough to play the little organ in the Union Church. Instead of being terribly scolded, as I had feared, Mrs. Calvert said: "Well, Fanny, when people will go ahead, they cannot be kept

Page 17

back; but, if you had asked me, you might have had the piano here." Mrs. Calvert taught me to sew beautifully and to darn, and to take care of laces. My life there was most happy, and I never would have left her, but it was in me to get an education and to teach my people. This idea was deep in my soul. Where it came from I cannot tell, for I had never had any exhortations, nor any lectures which influenced me to take this course. It must have been born in me. At Mrs. Calvert's, I was in contact with people of refinement and education. Mr. Calvert was a perfect gentleman, and a writer of no mean ability. They had no children, and this gave me an opportunity to come very near to Mrs. Calvert, doing for her many things which otherwise a daughter would have done. I loved her and she loved me. When I was about to leave her to go to the Normal School, she said to me: "Fanny, will money keep you?" But that deep-seated purpose to get an education and become a teacher to my people, yielded to no inducement of comfort or temporary gain. During the time that I attended the Normal School in Rhode Island, I got a chance to take some private lessons in French, and eagerly availed myself of the opportunity. French was not in the Oberlin curriculum, but there was a professor there who taught it privately, and I continued my studies under him, and so was able to complete the course and graduate with a French essay. Freedmen now began to pour into Ohio from the South, and some of them settled in the township of Oberlin. During my last year at the college,

Page 18

I formed an evening class for them, where they might be taught to read and write. It was deeply touching to me to see old men painfully following the simple words of spelling; so intensely eager to learn. I felt that for such people to have been kept in the darkness of ignorance was an unpardonable sin, and I rejoiced that even then I could enter measurably upon the course in life which I had long ago chosen. Mr. John M. Langston, who afterwards became Minister to Hayti, was then practicing law at Oberlin. His comfortable home was always open with a warm welcome to colored students, or to any who cared to share his hospitality.

I went to Oberlin in 1860, and was graduated in August, 1865, after having spent five and a half years.

The years 1860 and 1865 were years of unusual historic importance and activity. In '60 the immortal Lincoln was elected, and in '65 the terrible war came to a close, but not until freedom for all the slaves in America had been proclaimed, and that proclamation made valid by the victorious arms of the Union party. In the year 1863 a very bitter feeling was exhibited against the colored people of the country, because they were held responsible for the fratricidal war then going on. The riots in New York especially gave evidence of this ill feeling. It was in this year that the faculty put me to teaching.

Of the thousands then coming to Oberlin for an education, a very few were colored. I knew that, with the exception of one here or there, all my pupils would

Page 19

be white; and so they were. It took a little moral courage on the part of the faculty to put me in my place against the old custom of giving classes only to white students. But, as I have said elsewhere, the matter was soon settled and became an overwhelming success. How well do I remember the delighted look on the face of Principal Fairchild when he came into the room to divide my class, which then numbered over eighty. How easily a colored teacher might be put into some of the public schools. It would only take a little bravery, and might cause a little surprise, but wouldn't be even a nine days' wonder.

And now came the time for me to leave Oberlin, and start in upon my work at Philadelphia.

In the year 1837, the Friends of Philadelphia had established a school for the education of colored youth in higher learning. To make a test whether or not the Negro was capable of acquiring any considerable degree of education. For it was one of the strongest arguments in the defense of slavery, that the Negro was an inferior creation; formed by the Almighty for just the work he was doing. It is said that John C. Calhoun made the remark, that if there could be found a Negro that could conjugate a Greek verb, he would give up all his preconceived ideas of the inferiority of the Negro. Well, let's try him, and see, said the fair-minded Quaker people. And for years this institution, known as the Institute for Colored Youth, was visited by interested persons from different parts of the United States and Europe. Here I was given the delightful

Page 20

task of teaching my own people, and how delighted I was to see them mastering Caesar, Virgil, Cicero, Horace and Xenophon's Anabasis. We also taught New Testament Greek. It was customary to have public examinations once a year, and when the teachers were thru examining their classes, any interested person in the audience was requested to take it up, and ask questions. At one of such examinations, when I asked a titled Englishman to take the class and examine it, he said: "They are more capable of examining me, their proficiency is simply wonderful."

One visiting friend was so pleased with the work of the students in the difficult metres in Horace that he afterwards sent me, as a present, the Horace which he used in college. A learned Friend from Germantown, coming into a class in Greek, the first aorist, passive and middle, being so neatly and correctly written at one board, while I, at the same time, was hearing a class recite, exclaimed: "Fanny, I find thee driving a coach and six." As it is much more difficult to drive a coach and six, than a coach and one, I took it as a compliment. But I was especially glad to know that the students were doing their work so well as to justify Quakers in their fair-minded opinion of them. General O. C. Howard, who was brought in at one time by one of the managers to hear an examination in Virgil, remarked that Negroes in trigonometry and the classics might well share in the triumphs of their brothers on the battlefield.

When I came to the School, the Principal of the

Page 21

Institute was Ebenezer D. Bassett, who for fourteen years had charge of the work. He was a graduate of the State Normal School of Connecticut, and was a man of unusual natural and acquired ability, and an accurate and ripe scholar; and, withal, a man of great modesty of character. Many are the reminiscences he used to give of the visits of interested persons to the school: among these was a man who had written a book to prove that the Negro was not a man. And, having heard of the wonderful achievements of this Negro school, he determined to come and see for himself what was being accomplished. He brought a friend with him, better versed in algebra than himself, and asked Mr. Bassett to bring out his highest class. There was in the class at that time Jesse Glasgow, a very black boy. All he asked was a chance. Just as fast as they gave the problems, Jesse put them on the board with the greatest ease. This decided the fate of the book, then in manuscript form, which, so far as we know, was never published. Jesse Glasgow afterwards found his way to the University of Edinburgh, Scotland.

In the year 1869, Mr. Bassett was appointed United States Minister to Hayti by President Grant; leaving the principalship of the Institute vacant. Now, Octavius V. Catto, a professor in the school, and myself, had an opportunity to keep the school up to the same degree of proficiency that it attained under its former Principal and to carry it forward as much as possible.

Page 22

About this time we were visited by a delegation of school commissioners, seeking teachers for schools in Delaware, Maryland and New Jersey. These teachers were not required to know and teach the classics, but they were expected to come into an examination upon the English branches, and to have at their tongue's end the solution of any abstruse problem in the three R's which their examiners might be inclined to ask them. And now, it seemed best to give up the time spent in teaching Greek and devote it to the English studies.

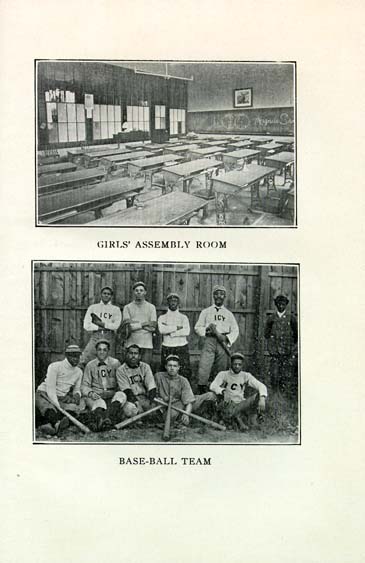

As our young people were now about to find a ready field in teaching, it was thought well to introduce some text books on school management, and methods of teaching, and thoroughly prepare our students for normal work. At this time our faculty was increased by the addition of Richard T. Greener, a graduate of Harvard College, who took charge of the English Department, and Edward Bouchet, a graduate of Yale College, and also of the Sheffield Scientific School, who took charge of the scientific department. Both of these young men were admirably fitted for their work. And, with Octavius V. Catto in charge of the boys' department, and myself in charge of the girls--in connection with the principalship of the school--we had a strong working force.

I now instituted a course in normal training, which at first consisted only of a review of English studies, with the theory of teaching, school management and methods. But the inadequacy of this course was so

Page 23

apparent that when it became necessary to reorganize the Preparatory Departments, it was decided to put this work into the hands of the normal students, who would thus have ample practice in teaching and governing under daily direction and correction. These students became so efficient in their work that they were sought for and engaged to teach long before they finished their course of study.

Richard Humphreys, the Friend--Quaker--who gave the first endowment with which to found the school, stipulated that it should not only teach higher literary studies, but that a Mechanical and Industrial Department, including Agriculture, should come within the scope of its work. The wisdom of this thoughtful and far-seeing founder has since been amply demonstrated. At the Centennial Exhibition in 1876, the foreign exhibits of work done in trade schools opened the eyes of the directors of public education in America as to the great lack existing in our own system of education. If this deficiency was apparent as it related to the white youth of the country, it was far more so as it related to the colored.

In Philadelphia, the only place at the time where a colored boy could learn a trade, was in the House of Refuge, or the Penitentiary!

And now began an eager and intensely earnest crusade to supply this deficiency in the work of the Institute for Colored Youth.

The teachers of the Institute now vigorously applied their energies in collecting funds for the establishment

Page 24

of an Industrial Department, and in this work they had the encouragement of the managers of the school, who were as anxious as we that the greatly needed department should be established.

In instituting this department, a temporary organization was formed, with Mr. Theodore Starr as President, Miss Anna Hallowell as Treasurer, and myself as Field Agent.

The Academic Department of the Institute had been so splendidly successful in proving that the Negro youth was equally capable as others in mastering a higher education, that no argument was necessary to establish its need, but the broad ground of education by which the masses must become self-supporting was, to me, a matter of painful anxiety. Frederick Douglass once said, it was easier to get a colored boy into a lawyer's office than into a blacksmith shop; and on account of the inflexibility of the Trades Unions, this condition of affairs still continues, making it necessary for us to have our own "blacksmith shop."

The minds of our people had to be enlightened upon the necessity of industrial education.

Before all the literary societies and churches where they would hear me; in Philadelphia and the suburban towns; in New York, Washington and everywhere, when invited to speak, I made that one subject my theme. To equip an industrial plant is an expensive thing, and knowing that much money would be needed, I made it a rule to take up a collection wheresoever I spoke. But I did not urge anyone to give more than

Page 25

a dollar, for the reason I wanted the masses to have an opportunity to contribute their small offerings, before going to those who were able to give larger sums. Never shall I forget the encouragement given me when a colored man, whom I did not know, met me and said: "I have heard of your Industrial School project, come to me for twenty-five dollars. That man was Walter P. Hall; all honor to him.

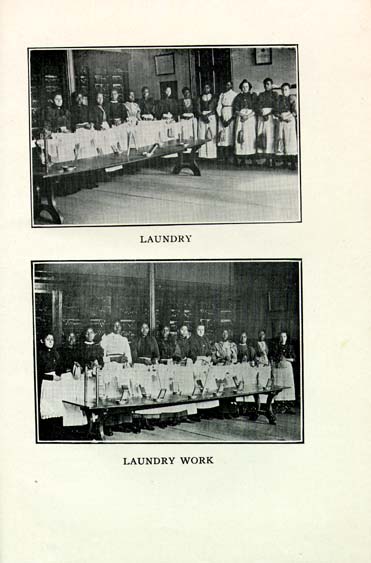

In preparing for the industrial needs of the boys, the girls were not neglected. It was not difficult to find competent teachers of sewing and cooking for the girls.

Dressmaking on the Taylor system was introduced with great success, and cooking was taught by the most improved methods.

As the work advanced, other trades were added, and those already undertaken were expanded and perfected.

When the Industrial Department was fully established, the following trades were being taught: For boys: bricklaying, plastering, carpentry, shoemaking, printing and tailoring. For the girls: dressmaking, millinery, typewriting, stenography and classes in cooking, including both boys and girls. Stenography and typewriting were also taught the boys, as well as the girls.

Having taught certain trades, it was now necessary to find work for those who had learned them, which proved to be no easy task.

It was decided to put on exhibition, in one of the

Page 26

rooms of the dormitory, specimens of the work of our girls in any trade in which they had become proficient, and we thus started an Industrial Exchange for their work. Those specimens consisted of work from the sewing, millinery and cooking departments.

In order to get the work of the Exchange more prominently before our people, I asked and obtained permission to hold some public exhibitions of it in the lecture rooms of the churches.

Those who sent their work to the Exchange were asked to send articles that would be salable.

Our white friends were invited to come and inspect the work of the Exchange. Some of the exhibits were found to be highly creditable, and many encouraging words were given to those who prepared them. There is one class of women, for whom no trades are provided, but who are expected to do their work without any special preparation; and these are the women in domestic service. I have always felt a deep sympathy with such persons, for I believe that they are capable of making a most honorable record. I therefore conceived a pan of holding some receptions for them, where the honorableness of their work and the necessity of doing it well might be discussed. I earnestly hoped that no one should be ashamed of the word servant, but should learn what great opportunity for doing good there is for those who serve others.

There is, and always must be, a large number of people who must depend upon this class of employment for a living, and there is every reason, therefore,

Page 27

why they should be especially prepared for it. A woman should not only know how to cook in an ordinary way, but she should have some idea of the chemical properties of the food she cooks. The health of those whom she serves depends much upon the nutritive qualities of the food which she prepares. It is possible to burn all the best out of a beefsteak, and leave a pork chop with those elements which should have been neutralized by thorough cooking.

A housemaid should know enough about sanitation to appreciate the difference between well ventilated sleeping rooms and those where impure air prevails.

I have often thought, as I sat in churches, that janitors should be better prepared for their work by being taught the difference between pure air and air with a strong infusion of coal gas.

Then, besides the mere knowledge of how to do things, morality and Christian courtesy are valuable assets for those who serve others. Thoughtful kindness for those we serve is always in place.

As a means of preparation for this work, which I may call an Industrial Crusade, I studied Political Economy for two years under Dr. William Elder, who was a disciple of Mr. Henry C. Carey, the eminent writer on the doctrine of Protective Tariff.

In the year 1879 the Board of Education of Philadelphia, instructed and admonished by the exhibit of work done in the schools of Europe, as exhibited in the Centennial exhibition of '76, began to consider what

Page 28

they were doing to train their young people in the industrial arts and trades. The comparison was not very gratifying. The old apprenticeship system had silently glided away, and merchants declared that under the pressure of competition they were not able to compete with other merchants, nor were they able to stand the waste made by those who did not know how to handle the new material economically. At a meeting of some of the public school directors and heads of some of the educational institutions, I was asked to tell what was being done in Philadelphia for the industrial education of the colored youth. It may well be understood I had a tale to tell. And I told them the only places in the city where a colored boy could learn a trade was in the House of Refuge or the Penitentiary, and the sooner he became incorrigible and got into the Refuge, or committed a crime and got into the Penitentiary, the more promising it would be for his industrial training. It was to me a serious occasion. I so expressed myself. As I saw building after building going up in this city, and not a single colored hand employed in the constructions, it made the occasion a very serious one to me. Nor could I be comforted by what the Irishman said, that all he had to do was to put some bricks into a hod and carry them up on the building, and there sat a gentleman who did all the work. The arguments which I then gave were chiefly those which I afterwards repeated in my appeal to the citizens of Philadelphia, and which I elsewhere reproduce.

Page 29

The next day Mrs. Elizabeth Whitney, the wife of one of the school directors, drove up to my school and said: Mrs. Coppin, I was there last night and heard what you had to say about the limitations of the colored youth, and I am here to say, if the colored people will go ahead and start a school for the purpose of having the colored youth taught this greatly needed education, you will find plenty of friends to help you. Here are fifty dollars to get you started, and you will find as much behind it as you need.

We only needed a feather's weight of encouragement to take up the burden. We started out at once. A temporary organization was formed, with Anna Hallowell as treasurer and Mr. Theodore Starr as president. I was unwilling to be the custodian of any large amount of money which might be begged from the poor colored people, and so myself and those who helped me asked each one to give only one dollar. I cannot mention the incidents which arose during this struggle and endeavor to supply this greatly needed want. We carried on an industrial crusade which never ended until we saw a building devoted to the purpose of teaching trades. For the managers of the Institute, seeing the need of the work, threw themselves into this new business, after their thirty previous years working for the colored youth. Our money in the end amounted to nearly three thousand dollars, and of this we have always been justly very glad. We could have had twenty times as much more, except for my backwardness and unwillingness to press poor

Page 30

people beyond what I thought they could give. Three thousand dollars was a mere drop in the bucket, but it was a great deal to us, who had seen it collected in small sums--quarters, dollars, etc. It was a delightful scene to us to pass thru that school where ten trades were being taught, altho in primitive fashion, the limited means of the Institute precluding the use of machinery. The managers always refused to take any money from the State, altho it was frequently offered.

Many were the ejaculations of satisfaction at this busy hive of industry. "Ah," said some, "this is the way the school should have begun, the good Quaker people began at the wrong end." Not so, for when they began this school, the whole South was a great industrial plant where the fathers taught the sons and the mothers taught the daughters, but the mind was left in darkness. That is the reason that John C. Calhoun is said to have remarked: "If you will show me a Negro who can conjugate a Greek verb, I will give up all my preconceived ideas of him." So that the managers had builded wiser than many persons knew.

In the fall of the same year, namely, in November, '79, as a means of bringing the idea of industrial education and self help practically before the colored people of the United States, I undertook the work of helping an enterprise, namely, The Christian Recorder, edited and published by colored men at 631 Pine street, Philadelphia. I here reproduce the plea made thirty-four years ago:

The Publication Department of The Christian Recorder

Page 31

is weighed down by a comparatively small debt, which cripples its usefulness and thus threatens its existence. This paper finds its way into many a dark hamlet in the South, where no one ever heard of the Philadelphia Bulletin or the New York Tribune. A persistent vitality has kept this paper alive thru a good deal of thick and thin since 1852. In helping to pay this debt we shall also help to keep open an honorable vocation to colored men who, if they will be printers, must "shinny on their own side." Knowing the conditions of the masses of our people, no large sums were asked for; the people were requested to club together and send on a number of little gifts, which might be at a stated time exhibited and sold at a fair. And thus the debt liquidated by a co-operative effort would be an instructive lesson of how light a burden becomes when borne by the many instead of the few. "Send something which you yourself have made or produced," we said. "Let what you send be made valuable by your artistic skill, your invention, and your industry." It was hinted that an exhibition of this sort might be greatly useful and creditable to us as a people, and that anything, from a potato to a picture, would be accepted. The result has been such as to gratify the highest expectations. Responses by donations of articles or money have been received from the following States: Michigan, Wisconsin, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Arkansas, Kansas, Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, New Jersey, New

Page 32

York, Rhode Island, Florida, Massachusetts, Virginia, Pennsylvania, Indian Territory and the District of Columbia. About two-thirds of the things at this fair were sent from the South, from Texas and some other distant parts, where the expressage on a box would have been large--our sugar cane cost our Florida friends $7 to express--from these points the people sent money; more than $80.00 thus contributed was spent to buy things on commission to help out. It seemed due to the people of the South and West who have so generously sent their little gifts to help keep alive a printing establishment in this city, from which there is no hope of their receiving any pecuniary benefit, it seemed due to them, I repeat, that we should not diminish the profits arising from the sale of these things by the purchase of gaudy and artistic flummery to dress the hall; so those who come to visit us will not , we hope, expect too much. The poor people who have sent us these things have shown a spirit of self-denial and of generous zeal which borders on heroism. All classes, including old people and young children, have vied with each other in sending some little article for the fair. If we had dared last year to predict these wonderful results it would have been set down as transcendental bosh, but we would have spoken "but the words of truth and soberness." The different kinds of needlework, crochet work and worsted work are very creditable; as also is the model of a church in Providence, Rhode Island, sent by a little boy; two ships, full rigged, and especially the decorated plates,

Page 33

and the pictures, "A Rocky Coast," the "Coast of Maine," and the "Wreck at Cape May" last summer, by H. O. Tanner, son of the editor of The Christian Recorder. The last contributors are colored lads, and I venture nothing in saying that their work would be creditable to any exhibition. The well-known artists, Robert Douglass and Wm. H. Dorsey, have many fine paintings on exhibition, especially an oil painting of Mr. Fred Douglass. The agricultural products could have been far larger than they are but for two reasons; first, it was especially understood in the beginning that this exhibition was to show, not what the few can do when they do a great deal, but what the many can do when each does a little; secondly, we were not able to pay the cost of expressage. I mean no reflection in any quarter when I ask thoughtful people if an exhibition of this kind, and for this cause, is not almost as important as holding a convention and reading a lot of "papers." The great lesson to be taught by this fair is the value of co-operative effort to make our cents dollars, and to show us what help there is for ourselves in ourselves. That the colored people of this country have enough money to materially alter their financial condition, was clearly demonstrated by the millions of dollars deposited in the Freedmen's Bank, that they have the good sense, and the unanimity to use this power is now proven by this industrial exhibition and fair. It strikes me that much of the talk about the exodus has proceeded upon the high-handed assumption that, owing largely to the credit system

Page 34

of the South, the colored people there are forced to the alternative to "curse God, and die," or else "go West." Not a bit of it. The people of the South, it is true, cannot produce hundreds of dollars, but they have millions of pennies; and millions of pennies make tens of thousands of dollars. By clubbing together and lumping their pennies, a fund might be raised in the cities of the South that the poorer classes might fall back upon while their crops are growing, or else by the opening of co-operative stores become their own creditors and so effectually rid themselves of their merciless extortioners. "O, they won't do anything; you can't get them united on anything!" The best way for a man to prove that he can do a thing is to do it, and that is what we have done. This fair, participated in by twenty-four States in the Union, and got up for a purpose which is of no pecuniary benefit to those concerned in it, effectually silences all slanders about "we won't or we can't do," and teaches its own instructive and greatly needed lessons of self-help, the best help that any man can have, next to God's.

Those who have this matter in charge have studiously avoided preceding it with noisy and demonstrative babblings, which are so often the vapid precursors of promises as empty as themselves; therefore in some quarters our fair has been overlooked. It is not, we think, a presumptuous interpretation of this great movement, to say that the voice of God now seems to utter, "Speak to the people that they go forward." "Go forward" in what respect? Teach the millions of poor

Page 35

colored laborers of the South how much power they have in themselves, by co-operation of effort, and by a combination of their small means to change the despairing poverty which now drives them from their homes, and makes them a millstone around the neck of any community, South or West. Secondly, that we shall go forward in asking to enter the same employments which other people enter. Within the past ten years we have made almost no advance in getting our youth into industrial and business occupations. It is just as hard to get a boy into a printing office now as it was ten years ago. It is simply astonishing when we consider how many of the common vocations of life colored people are shut out of. Colored men are not admitted to the Printers' Trade Union, nor, with very rare exceptions, are they employed in any city of the United States in a paid capacity as printers or writers, one of the rare exceptions being the employment of H. Price Williams, on the Sunday Press of this city. We are not employed as salesmen, or pharmacists, or saleswomen, or bank clerks, or merchants' clerks, or tradesmen, or mechanics, or telegraph operators, or to any degree as State or Government officials, and I could keep on with the string of "ors" until tomorrow morning, but the patience of a reader has its limit.

Slavery made us poor, and its gloomy, malicious shadow tends to keep us so. I beg to say, kind reader, that this is not spoken in a spirit of recrimination; we have no quarrel with our fate, and we leave your

Page 36

Christianity to yourself. Our faith is firmly fixed in that "Eternal Providence," that in its own good time will "justify the ways of God to man." But, believing that to get the right men into the right places is a "consummation most devoutly to be wished," it is a matter of serious concern to us to see our youth, with just as decided diversity of talent as any other people, all herded together into three or four occupations. It is cruel to make a teacher or a preacher of a man who ought to be a printer or a blacksmith, and that is exactly what we are now obliged to do. The most advance that has been made since the war has been done by political parties, and it is precisely into political positions that we think it least desirable that our youth should enter. We have our choice of the professions, but, as we have not been endowed with a monopoly of brains, it is not probable that we can contribute to the bar a great lawyer, except once in a great while. The same may be said of medicine; nor are we able to tide over the "starving time," between the reception of a diploma and the time that a man's profession becomes a paying one.

Being determined to know whether this industrial and business ostracism was "in ourselves or in our stars," we have from time to time, knocked, shaken and kicked at these closed doors of work. A cold, metallic voice from within replies, "We do not employ colored people." Ours not to make reply, ours not to question why. Thank heaven, we are not

Page 37

obliged to do and die, having the preference to do or die, we naturally prefer to do. But we can not help wondering if some ignorant or faithless steward of God's work and God's money hasn't blundered. It seems necessary that we should make known to the good men and women who are so solicitous about our souls and our minds that we haven't quite got rid of our bodies yet, and until we do we must feed and clothe them; and this thing of keeping us out of work forces us back upon charity. That distinguished thinker, Mr. Henry C. Carey, in his valuable works on Political Economy, has shown by the truthful and irresistible logic of history that the elevation of all peoples to a higher moral and intellectual plane, and to a fuller investiture of their civil rights has always steadily kept pace with the improvements in their physical condition. Therefore we feel that resolutely and in unmistakable language, yet in the dignity of moderation, we should strive to make known to all men the justice of our claims to the same employments as other men under the same conditions. We do not ask that any one of our people shall be put into a position because he is a colored person, but we do most emphatically ask that he shall not be kept out of a position because he is a colored person. "An open field and no favors" is all that is requested. The time was when to put a colored boy or girl behind a counter would have been to decrease custom; it would have been a tax upon the employer, and a charity that we were too proud to

Page 38

accept; but public sentiment has changed. I am satisfied that the employment of a colored clerk or a colored saleswoman wouldn't even be a "nine days' wonder." It is easy of accomplishment, and yet it is not done. To thoughtless and headstrong people who meet duty with impertinent dictation I do not now address myself; but to those who wish the most gracious of all blessings, a fuller enlightenment as to their duty, to those I beg to say, think of what is said in this appeal.

We do not ask our white friends to come out and make this fair a success. If the word "grand" was not so abominably ill used, I would say that we have already made it a grand success; come and help us make it a greater one. For ten days the colored citizens have crowded this fair. They have bought more than half our contributions. From the ministers of the churches, irrespective of denomination, to the ladies who are attending tables, and the United Order of Masons who rented us the hall, all have shown a generosity, devotion and a warmth of public spirit worthy of the highest praise.

Believing that all efforts at self-help are worthy of respect, and when a man is using every effort in his power to help himself he may with propriety call upon his friends for encouragement, I now respectfully submit this matter to the citizens of Philadelphia and cordially invite them to visit us. As those of us who have charge of the fair are working-women, we do not open it until five o'clock in the afternoon. It is held in Masonic Hall, on Eleventh street, between Pine and Lombard, and will continue all this week.

Page 39

II.

ELEMENTARY EDUCATION.

MY DEEP interest centers in elementary education for several reasons; first, because it is at this period of the child's life that habits are formed and tastes cultivated which may guide him in the pursuit of knowledge and happiness in after life, and which by the alchemy of experience are to change the elements of what he has learned into wisdom for his highest happiness. All higher learning is but a combination of a few simple elements, and when these are well taught, it clears away the difficulty of future acquisitions, and nature can spread her beauty before eyes that can see and teach the marvelous precision of her laws, to ears that can hear. I call this opening the doors upward and outward, whereas a different way of instruction is like going out of a room backward.

Again, we want to lift education out of the slough of the passive voice. Little Mary goes to school to be educated, and her brother John goes to the high school for the same purpose. It is too often the case that the passive voice has the right of way, whereas in the very beginning we should call into active service all the

Page 40

faculties of mind and body. Unfortunately book learning is so respectable, and there is so much of it all about us, that it is apt to crowd out the prosy process of thinking, comparing, reasoning, to which our wisest efforts should be directed.

Now, when we consider how much is lost by those who lose the benefit of the elementary development, and are therefore unable to pursue the higher branches with any degree of success or comfort to themselves or others, it is evident that this subject is worthy of a wise investigation and we must ask ourselves, how far are we responsible for this condition of affairs? I fear that the reason that so many are unable to keep up when they begin the higher studies is because they never mastered the elementary principles.

If a pupil is absent review day, or demonstration day, he is sure to feel the loss keenly in further pursuit of his studies. Growth in learning and acquisition proceeds slowly and by steps, and we must follow nature's direction.

To be at our business punctually and promptly every day is positively necessary for success, and no trifling excuse ought to be sufficient to keep us from our duty. You know what Uncle Dread said: "Scuses, scuses, the world is built on scuses." A habit of always being on hand in time will save the child from much loss in its after life.

I think a very profitable way to help those who have been absent to make up for what they have lost, while at the same time they are getting the work better

Page 41

understood, is to have daily reviews of at least one half of the lesson; part oral and a part written. Such a course will be beneficial even to those who were not absent. It will be found very profitable always to have two or three divisions of the class. The divisions can be based upon ability to do the work rapidly or slowly. For where a person who is very quick gets beside a person who is very slow, he feels that he is wasting his time and becomes very impatient. And now is the time for the exercise of that Christian courtesy which will help us all the way through life.

Never let the word "dumb" be used in your class, or anything said disrespectful of parents or guardians who may have helped the child. If the teacher has the questions or the review well selected, they can be quickly given out and no one division has to wait for the other. When the teacher has given all the time possible to certain work, the divisions can be stopped, arranged in order and the pupils will profit by the criticisms of one another, the teacher making no corrections that can possibly be made by the class; thus inviting and stimulating the critical knowledge or judgment of all; whether in punctuation, spelling, subject matter, or the appearance of the work; the advanced lesson already having been heard by the teacher.

Blackboards are of great use in schools, and are a mercy to the eyes of the pupils that are thus released from the printed page; or if we can't have blackboards, then we can use brown paper, saved up from bundles containing articles, etc.

Page 42

I do not see how a teacher can succeed well without ingenuity, because ways of finding means to an end must often be discovered by the teacher. It has been said that not only from the elementary classes, but also from the higher classes, those that drop out do so from the want of better elementary training.

I should like to ask why some of the axioms that might be so helpful are not brought to bear much earlier in the course of instruction. For instance the square of the sum, the square of the difference, and the rectangle of the sum and difference, as (5+3)X(5+3), (5-3)X(5-3) and(5+3)X(5-3)

To do this work and then show by inspection that the first contains

- 1. Square of the sum.

- 2. Square of the difference.

- 3. Rectangle of the sum and difference.

The multiplication table offers a fruitful field for study, developing the tables of 2's, 3's and 4's etc., and picking out cubes and squares in each one.

I've often had teachers say to me, Oh, that was learned long ago.

The numerical cube is the product of a number taken twice as a factor or multiplied into itself once:

The geometrical square is an equilateral rectangle:

The numerical cube is the product of a number taken three times as a factor or multiplied into itself twice.

Page 43

The geometrical cube is a solid bounded by six equal squares.

One of the most useful operations is, having a fractional part of a number, to find it; as, 30 is 5/7 of what number? We shall meet this operation often, even in higher arithmetic, and it can be easily taught when teaching the multiplication table.

Of course, when pupils are just beginning they cannot be left so much to themselves, for everything must be carefully done.

Page 44

III.

METHODS OF INSTRUCTION.

I AM always sorry to hear that such and such a person is going to school to be educated.

This is a great mistake. If the person is to get the benefit of what we call education, he must educate himself, under the direction of the teacher.

To go into the school and take one's seat is not a favorable sign for the work that is going to be done; the very first thing to do is to get our pupils into an orderly arrangement for working. The teacher probably has two or three divisions; one set will be employed at the blackboard, and one will recite to the teacher the lesson of the day. The work at the blackboard is review work. And just here is a very important step.

What shall the review consist of? I would say let one-half or three-fourths of the lesson be the review, and spend the rest of the time on the advanced lesson; that is, the lesson for the day. In order that no time may be lost in giving out the review, the teacher will have all the points selected for review written off, and some member of the class may pass

Page 45

these papers round to the division that has the review, and each one as he takes his paper goes to the board to do his work; or, if he has no board, then he must have the paper to write on, but let us hope that a very few will have to use paper, for the eye needs rest from the small writing with the pencil, and the eye of the teacher is also benefited by not having to scrutinize small letters, whereas the chalk on the blackboard sets off the words and is a great relief to the eye.

When the teacher has given as much time as he can with the work on the board, he stops the class that has been reciting to him and both divisions undertake the corrections of the board work; this must be done in a systematic manner.

Where shall we begin?

I should say to begin with what appears to be the poorest work on the board, in order that the most corrections may be made, and now the teacher must show great skill in keeping the attention of the class fixed upon one matter, for when they are enthusiastic, all will want to speak at once, or some will want to make remarks, or to jump from one point to another before the first is completely done.

Those who have been absent from time to time will find the reviews a great benefit to them, for when there is a distinct failure, we often hear the person say, I was absent when that lesson was given, for I don't remember it at all. How, then, could these children

Page 46

go on with the advanced lesson with any degree of understanding or profit?

Trial examinations upon simple principles that have been given for some time will oftentimes be of great profit to the class.

The teacher is not supposed to be talking or looking out of the window while the examination goes on, but is passing quietly from seat to seat looking at each person's work, so that when the time is up he is quite well informed as to how each person has succeeded in the work required of him, and what the principal errors are.

The vital errors are errors in the principles used. The misspelled words, grammatical errors, and anything else wrong comes in for its share of correction.

This correction by the teacher, coming immediately after the work is done, is very helpful to those being examined, and saves the teacher from carrying the work home and having to go over it all by himself, and besides, the pupils get far more benefit from this co-operative correction, as it may be called.

In order that the teacher may do his best work while his class is with him, it is necessary that he should have his work all arranged in his own mind before he meets the class. If the teacher is ingenious and he cannot be a good teacher without ingenuity, he can think out many helpful ways to occupy his pupils to the best advantage while he is with them. The lowest classes, as well as the highest, will reap

Page 47

great benefit from this skillful arrangement of their work by their teacher. I have before spoken of division of classes into two or three sections, but the teacher who makes the division must be very careful not to say of number one, this is the slowest division; or of another, this one can go more rapidly.

The teacher knows upon what principle to form his division, but if he begins to state his reasons to the class he will find it like throwing down the apple of discord: there will be no end to the exclamations of those who are in number two, who say that they could go on with number three, and those in number one will declare they can work just as fast as number two.

It is enough for the teacher to say that the classes can be managed and can do far more work when the teacher handles them in smaller numbers, so that one division can be writing while another is reciting, and all are kept busy as bees. The whole class should be working under the eye of the teacher. It ought not be necessary for the teacher to turn around to see if those who are at the board or those who are doing the work in their seats are in good order and not disturbing one another. A skillful arrangement on the part of the teacher can bring the whole under his own supervision. But the teacher should by no means take up a position as if watching the pupils. Put their conduct on high ground at the very beginning, and when they disappoint you by doing what the teacher would object to, we must let them know how disappointed

Page 48

we are by such a betrayal of trust, and they may start the next day to do better; and so, little by little, these young people will acquire the habit of doing what they know is right, whether the teacher sees them or not.

I have before spoken of talking in classes, because it disturbs the teacher and disturbs the class, but I have often heard them say, suppose I only whisper, would that disturb the class? As far as my experience goes, there can be no compromise with talking or whispering while the work is going on. The habit of self control is not easily acquired, but when the pupil has his tongue under control St. James says, "He is able also to bridle the whole body." I believe that many a dreadful result has followed a too free use of the tongue, for it is well said, one word always brings on another and before we know it we are in the midst of a hot dispute over something. Not only the children, but the teacher may have too nimble a tongue, and may use it, not to explain what is difficult to the pupils, but to discuss why they are so stupid as to need any explanation.

Sometimes the teachers make uncomplimentary remarks about those who need to have the matter explained, saying, anybody could see that. I heard of a little boy once whose father had worked out some examples for him in arithmetic. The teacher should have known that the child did not do the work, and should have been careful about speaking of that work.

Page 49

"Why, that's a very old-fashioned way of doing that work; we don't do that way now," and other things were said even more uncomplimentary of the person who did the work for the child. Here, again, is a case where the teacher needs to be corrected. It may as well be understood that all remarks which are disrespectful to the parents or guardian ought never to be indulged in by the teacher. Calling names, the words stupid, or dunce, or dumb, serves only to make the pupil angry or to discourage him. Here, again, the teacher ought to think of himself when he was taking his first lessons. Whenever a pupil has spoken disrespectfully to a teacher and the teacher can say with truth, do I not always speak kindly and politely to you? the case is won without any more argument. I have never known this to fail. I have often seen a tear steal down the face of a child, and then I neither asked for an apology nor forced one, but of the child's own volition it came at once.

How can we get the child trained to do what he dislikes to do and to obey our laws without corporal punishment? If the parent begins early enough, there is every hope of success, but, unfortunately, it is thought the child isn't old enough to understand what we wish him to do. For instance, a mother sees her little boy going around the room with a hammer, and of course looking for something to hit with it. She repeatedly tells him to bring the hammer to mamma, but he pays no attention to it. And, waiting a little while, she goes to him and takes the hammer away

Page 50

from him. He struggles with all his little might to keep it.

The mother should know it will not be very long before that little fellow will be strong enough, not only to keep the hammer, but to do with it as he will. Then was the time, when he paid no attention, for her to have taught that child to obey her and bring her the hammer of his own will. A little battle like that lost or won means victory or defeat for that child's future character.

To learn to give up his own will to that of his parents or teacher, as we must to the Great Teacher of all, will surely make us happy in this life and in the life to come. Happy is the child who has wise parents and guardians, and whose training is continued when he enters the school room. Whereas when a child has had little training in obedience at home it is not long before he gets into trouble in the school room, for there he finds himself surrounded by laws which he must obey if he makes the progress in his studies and in his character which he ought to make, which will give him an honored place in the school and out of it.

Page 51

IV.

DIAGNOSIS AND DISCIPLINE.

IT IS possible for the teacher to notice who those are in the class who do not care for learning what we have to give them; and the question to ask ourselves is, Why? Are the lessons too hard? or are they too long? Is the child well? Above all, does he seem to pass from one to another part of study with ease and comfort to himself, or is he troubled and uncertain? Does he often give excuses for staying away, and does he fail to get the meaning of what we are trying to teach him? When he fails in his lessons, does the teacher let the parent or guardian know, and how is this information supposed to be received at his home?

I have heard of a case where whenever the child failed in his lessons, word was sent to his father, who gave him no dinner and locked him up in the cellar. Would this punishment incline the child to love his studies or to get them any better? On the contrary, would he not hate them and be glad when he is through with them? We should remember that punishments

Page 52

that do not correct, harden. For this reason we should try to find out what the real trouble is, and then what will best make up for it.

Examinations privately conducted without letting the person know what you are looking for may give the true source of the trouble. And we may discover why the work we have given is not done. For instance, at one time being accused of having promoted a scholar to a higher class who could not multiply, I replied, "I know he can multiply." "Try him yourself," said the teacher. And I did try him myself, and found that when the multiplier and the multiplicand were separated as in long division the child did not know at what end to begin to multiply. As soon as I let in light on this point he went ahead like everything. Sometimes I've said to myself as I've watched the way that a pupil worked, you say you cannot get this example; no, and you never would have gotten it if you had kept on that way. All learning proceeds by steps. And the absences of pupils may be illustrated by a ladder with a rung out here and there. So that instead of the person going up easily and smoothly, he is every now and then distracted by the difficulty of the step. Let the pupils make a ladder, and show these parts out. Every succeeding lesson is carefully planned by a preceding demonstration or piece of instruction, and when a pupil is absent on one of these days it is very difficult to make up for it. We ought to be very careful about apportioning

Page 53

any severe punishment, and it would be well to sleep over it before we decide.

If the teacher is just as angry as the pupil, which is sometimes the case, he is not apt to do the wisest and kindest thing to bring about a spirit of repentance and a wish to correct what has been wrong. Happy is the teacher who can wait to win his pupil, to what he believes to be right.

I can think of no agency in the formation of a beautiful character that is more powerful than the daily correction and training which we call discipline, and here the teacher is all powerful.

The child can read his books and get much information from them to help him in his education, but he cannot see when he should be corrected, nor how to do so. To be apt in diagnosing a case to find the difficulties that a child labors under, and as apt in the correcting discipline, are valuable qualifications for a teacher. These qualifications cannot be put down in a book to be learned as ordinary lessons. We can only give suggestions, and the teacher must work out his own plans, and acquire the knowledge by actual practice.

Many a child called dull, would advance rapidly under a patient, wise and skillful teacher, and the teacher should be as conscientious in the endeavor to improve himself as he is to improve the child.

Page 54

V.

OBJECT OF PUNISHMENT.

LET us understand that the object of punishment is not to make up for wrongdoing, for that cannot be done; but, to prevent the repetition of the wrong. It should always be administered in a kind spirit, and should be so reasonable, that a child's sense of justice would agree with it. He should see that if he repeated the wrong act it would not be good for him nor for the teacher nor his parents nor the school.

Of course no cruel punishment should ever be allowed, and if whipping is to be done it is far better for the parent to do it, for his hand is restrained by love.

I once heard this story. Two little boys were out selling matches; one having sold out met a comrade who had not sold any. Said the one who had been successful to his comrade, "I will take your matches and give you my money. If I am not sold out when I get home I shall get a whipping like yourself. Your master would whip you, but my father would whip me, but he wouldn't whip so hard nor so long as

Page 55

your master." A page of philosophy could not give us a better understanding of the case, than is given by the incident of these two little match boys.

Habits of obedience can be taught to a child when it is little so that little by little he learns to give up his own will to that of his parents or teacher, which alone can make us happy in this life and the life to come. When spoken to disrespectfully I would say to the child, "Do I not always speak to you kindly and politely?" I never had to make any other argument. I never asked for any apology, and I never failed to get it. Not perhaps at that time, but after it had been thought of. It seems to me that it would be very unwise to send a bad report to the parent concerning the child unless we know the disposition of the parent and his means of correcting. This is very important, for if the child is not corrected of his fault, he is apt to become worse instead of better.

Never be in a hurry about punishing a child. Think well over it first. Always investigate a case thoroughly before you punish a child.

Try never to whip the child yourself; always report the child to the parents when such correction is necessary.

Never deprive a child of all of his recess. He is not a block of wood; he needs fresh air and water and he will not be in a condition to recite unless he has time for that. Some teachers think they haven't

Page 56

punished enough unless they have taken all of his recess. This is a great mistake. To take a child's lunch from him is a great mistake. There is no use in attempting to teach a hungry child.

The ventilation of the school room may be responsible for what we call stupidity on the part of the child.

Let a stream of oxygen pass through the room and what a waking-up there will be! Sometimes if a child is naughty it will do him good to run out in the yard a minute.

Remember all the time you are dealing with a human being, whose needs are like your own.

A child knows well when a teacher is kind and considerate of him.

Never take away a child's occupation as a punishment.

The secret of good government is occupation of the right kind.

Keep your pupils pleasant by occupying them with your work and they will not be apt so to give you trouble. There are a number of devices called "Busy Work for the School Room." These little occupations are suited to every grade, and the teacher should make a study of them and have them at his command. The teacher knows who the restive pupils are, and work for these should be prepared beforehand. A great deal of what we call mischief is animal activity on the part of the child, and we must

Page 57

use that activity to make the child do our work and not his.

There is too much repression and suppression in schools.

Let the child do something of himself and see what he will do. The teacher must prepare for his work before he goes into the school by getting together as much simple apparatus as possible, and finding means of illustration.

There are certain kinds of punishments that should never be resorted to, such as shutting a child up in the school house while you go to your dinner, or shutting him up in a dark closet and keeping him there longer than a half hour, or boxing his ears or hitting him over the head or calling him names.

Try kindness; try to find the wiser way for correcting the wrong.

Be careful of arousing a spirit of revenge in your pupils.

Page 58

VI.

MORAL INSTRUCTION.

WHATEVER we do, the first thing is to have the child know about his Heavenly Father, and that we must all do what will please Him; and no one of us must think of doing the things that He hates. We cannot grow straight and beautiful if we disobey His laws: and so, we must preoccupy the ground very early, for evil is so crafty that even with all our vigilance it will get its work in somewhere. "Didst not thou sow good seed in thy field? whence then hath it tares?"

However brilliant a person may be intellectually, however skillful in the arts and sciences, he must be reliable; he must be trustworthy.

We must know that we can depend upon his word. Obedience, truthfulness, love of right, and sincerity, must be instilled and inculcated by precept and by example, but always in kindness.

Love wins when everything else will fail. You say that your child resists all your efforts to break him of his bad habits and make him become good. Have you tried kindness? Have you tried love?

Page 59

The Commandments in verse are very easily learned; therefore I would have them taught.

Thou should have no other Gods before me.

Before no idol bend thy knee.

Take not the name of God in vain.

Nor dare the Sabbath Day profane.

Give both thy parents honor due.

Take heed that thou no murder do.

Abstain from words and deeds unclean.

Nor steal though thou art poor and mean.

Nor make a willful lie and love it.

What is thy neighbors do not covet.

With all thy heart love God above,

And as thyself thy neighbor love.

The pieces so called which the child learns, will have much to do with forming his mind, and so we pick them out with a great deal of care.

Love to father and mother, sister and brother; love to home and country; love to animals.

In short fill the mind with what we know will keep it pure and beautiful. Above all things see that the child is getting a love to take in and do what is taught him. Scripture that the child can understand will of course be our first ally, as, "Jesus loves me this I know, for the Bible tells me so."

Bands of Hope must be kept in view, for in the very beginning the child must be taught the danger of strong drink. The selection of pieces to sing must be observed with great care. However pretty a tune is, if it doesn't carry beautiful words we should not choose it.

Page 60

The books which our children read should also be carefully looked into. We should do well always in Christmas times and other times to be sure that one of the presents is a book. And the child should be encouraged to make his own little library case by utilizing a starch or soap box. Ingenious young people can soon make a very presentable library case.

Studies in history, American, English, French, etc., natural history and poetry, which children love so much, can also be among the books.

Happy are the children whose parents know the importance of teaching them to love and care for books while they are young. Among the little societies in our school, there was one for charitable purposes and entirely in the hands of the children. Each one was invited, not forced, to give one cent a week. This sum amounted to $75 or $100 a year.

They took charge of small cases of want and destitution until they could report them to the proper societies. And it was a great comfort to me when the time came to make their contributions to various charities, such as the Children's Home; the Aged Home; Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, and other charities; and to see them making out their little checks was also comforting. There was much merriment when we came to this little business, for how to draw up a money order, or how to make out a check and other little matters of bookkeeping had to be taught.

As I have said; nobody was obliged to give the

Page 61

penny a week, but they all were invited to do so. When the young people came home after vacation, they had made sums to help themselves along, and those sums added together varied from $2,000 to $2,500.

Of course the students in the higher classes made most, because they could get more responsible work to do. Very interesting incidents cropped out during these reports, but I can only mention one or two. One of our little girls between eleven years and twelve went along as chore girl. But there was consternation in the household when it was discovered that the cook had disappointed. "But," said the little girl, "I can cook." So it was only necessary to change places. And our little girl found her wages increased from $1 to $3 a week.

Another case of a little girl only about seven years who had saved up a little something during the vacation. "Now what did you do?" said I, "I know you couldn't have worked." "I used to go every Sunday and take a blind lady to church. Then she used to give me fifty cents every time I went and I saved it up."

Many incidents might be told of this kind, but I am warned that printing costs money, but the training which bears fruit in a thoughtful application of what we have learned deserves encouragement.