Memoir of Pierre Toussaint,

Born a Slave in St. Domingo:

Electronic Edition.

Lee, Hannah Farnham Sawyer, 1780-1865

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Melissa Meeks and Natalia Smith

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Elizabeth S. Wright, and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2001

ca. 150K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, Born a Slave in St. Domingo

(spine) Pierre Toussaint

Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee, 1780-1865

[2], 124 p., ill.

BOSTON:

CROSBY, NICHOLS, AND COMPANY, 111 WASHINGTON STREET.

1854.

Call number (T) F1914.T6 L43 1854 (James E. Shepard Memorial Library, North Carolina Central University)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

- French

LC Subject Headings:

- Slavery -- Haiti -- History.

- Toussaint, Pierre, 1766-1853?

- Blacks -- Haiti -- Biography.

- African Americans -- New York -- Biography.

- Free African Americans -- New York -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Haiti -- Biography.

- Slaves -- New York -- Biography.

- Hairdressing -- New York -- History.

- Slavery --New York -- History.

- Slave narratives.

Revision History:

- 2003-09-09,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-08-24,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-08-03,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-07-18,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

Page i

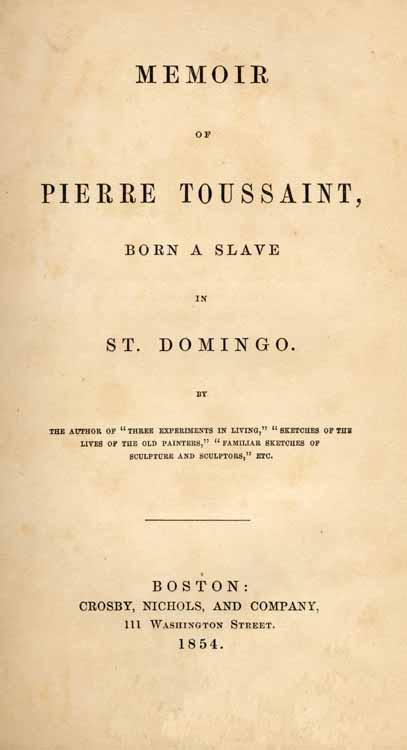

MEMOIR

OF

PIERRE TOUSSAINT,

BORN A SLAVE

IN

ST. DOMINGO.

BY

THE AUTHOR OF "THREE EXPERIMENTS IN LIVING," "SKETCHES OF THE

LIVES OF THE OLD PAINTERS," "FAMILIAR SKETCHES OF

SCULPTURE AND SCULPTORS," ETC.

BOSTON:

CROSBY, NICHOLS, AND COMPANY,

111 WASHINGTON STREET.

1854.

Page verso

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1853, by

CROSBY, NICHOLS, AND COMPANY,

in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

CAMBRIDGE:

METCALF AND COMPANY, STEREOTYPERS AND PRINTERS.

Page 1

PART FIRST.

THE records of distinguished characters are multiplied around us: the statesman who has toiled night and day for his country is held in grateful remembrance;--the hero who has fought for the land of his home and people justly wins the laurels that are showered upon him;--the scholar who devotes his pen to the instruction of his fellow-beings, the poet, and the historian gradually build for themselves monuments. But there is one class whose silent accumulation of good deeds is not computed, but which is daily increasing the amount of human happiness, and whose influence is like that of the crystal stream which wanders through the meadow, adding

Page 2

to its uncounted portion of wild-flowers and verdure. Of such a one we would speak in the simple, unexaggerated language which corresponds to the subject of this memoir.

PIERRE TOUSSAINT was born in the island of St. Domingo, in the town of St. Mark, on the Plantation de Latibonite, which belonged to Monsieur Bérard. The grandmother of Toussaint, Zenobe Julien, was a slave in the family, and selected as a wet-nurse for the oldest son. This maternal office she also performed for his sister.

It was customary in the West Indies for people of fortune to send their children abroad, to secure to them better influences than they could obtain on a plantation. Sometimes, at the age of four and five years, sons and daughters were separated from tender parents, with a degree of heroic sacrifice for which nothing but the importance of the measure could give their parents resolution.

M. Bérard early decided to send his son to Paris to be educated; and to supply, as far as possible, the tenderness of a mother, Zenobe

Page 3

Julien was selected to accompany him, and to remain with him several months. This proof of the father's confidence in the bond-woman sufficiently demonstrates the reliance which both parents placed on her. When she returned to St. Domingo, it was to conduct the two daughters to Paris, who were to be placed at a boarding-school.

On leaving them there, she again returned to St. Mark and resumed her attendance on her mistress. The parents so fully estimated the worth of this faithful domestic, that, as a reward for her fidelity and a proof of their entire confidence, they gave her her freedom. They well knew that her attachment to them formed the strongest bonds. John Bérard constantly wrote to her from Paris, sending her presents, and retaining his early affection.

Zenobe had a daughter whom she called Ursule. As the little girl increased in years, she became more and more useful to Madame Bérard, and was finally adopted as her waiting-maid and femme de chambre.

The subject of our memoir, Pierre Toussaint,

Page 4

was the son of Ursule, and became the pet of the plantation, winning all hearts by his playfulness and gentleness.

His grandmother, Zenobe, was particularly attached to him; yet when Monsieur and Madame Bérard concluded to rejoin their children in France, and called on Zenobe to accompany them, she did not hesitate for a moment, but gave them her free obedience, and cheerfully acceded to their wishes; for they no longer had the right to command. For the fifth time the faithful attendant crossed the ocean,--a more adventurous and lengthened voyage than now,--and after seeing her master and mistress settled in Paris, returned again to St. Mark. Here she had the happiness of passing the evening of her life in the service of her nursling, John Bérard, who came back to reside on his father's plantation after he had completed his studies, leaving his two sisters with his parents.

Pierre Toussaint was born before the elder Bérard quitted the country, and Aurora, his youngest daughter, stood godmother to the

Page 5

infant slave. She was a mere child, and he could have no recollection of the ceremony; but as he grew older, he became more and more devoted to his little godmother, following her footsteps, gathering for her the choicest fruits and flowers, and weaving arbors of palms and magnolias. Toussaint's happiness was much increased by the birth of a sister, who was called Rosalie.

We can scarcely imagine a more beautiful family picture; it was a bond of trust and kindness. Slavery with them was but a name.

About the time of Pierre Toussaint's birth, 1766, and several years later, the island of St. Domingo, or Hayti, as it was usually called, was in its most flourishing state. The French colony was then at the height of its prosperity. The tide of improvement had swept over the land; forests had been cleared, marshes drained, bridges built over rivers, torrents converted into picturesque waterfalls. The harbors were made safe and commodious, so that large vessels could ride at anchor. Beautiful

Page 6

villas and cottages bordered the sea, while palaces and magnificent public buildings adorned the interior. Hospitals were built; fountains refreshed the air. Scarcely could imagination reach the luxury of this island, which seemed to contain in its bosom the choicest treasures of nature. Such an earthly paradise could not fail to attract foreigners. The French were proud of their colony, and it became a fashion with them to emigrate to the island. Some settled as planters, others passed to and fro at their pleasure, promoting commerce, good-will, and the arts of refinement.

The terrible events which followed this flourishing era are too painful to record; yet we can hardly forbear touching upon the history of Toussaint L'Ouverture, though bearing no other connection with the subject of our memoir than accidentally arises from similarity of name, color, country, and being both born in slavery, and on the same river. Toussaint L'Ouverture, so famous in history, was born in 1745, about twelve years before Pierre Toussaint,

Page 7

but had arrived at mature life before he became conspicuous, and was till then only distinguished for his amiable deportment, his humanity, and the purity of his conduct. His discriminating master, Comte de Noé, early perceived the power of his intellect, and had him instructed in reading, writing, and arithmetic; and he allowed him the use of his books, from which he culled a surprising amount of knowledge. It is well known, that, in the insurrection of the negroes, he refused all participation, until he had effected the escape of M. Bayou (to whom he was coachman) and his family to Baltimore, shipping a large quantity of sugar for the supply of his immediate wants.

The subsequent career of Toussaint L'Ouverture was a noble one. His superior capacity gave him complete ascendency over the black chieftains, while his natural endowments of manner and person inspired respect and deference, and enabled him to keep in check their wild and revengeful passions.

In 1797 Toussaint L'Ouverture received a

Page 8

commission from the French government of commander-in-chief over the armies of St. Domingo. From 1798 until 1801 the island continued peaceable and tranquil under his sway. His measures were mild and prudent, but his discipline was strict. In 1801, when the independence of Hayti was proclaimed, he sent his two sons to France for an education.

Bonaparte sent them back some time after, accompanied by Le Clerc, with orders not to give them up, but to retain them as hostages, if Toussaint refused to abandon his countrymen. With a magnanimity that equals the records of ancient history, the father suffered them to return. It is not in accordance with our present plan to trace the dark and treacherous snares which enveloped him. It is well known that, notwithstanding the most solemn assurances of safety, he was seized and conveyed in the night on board a vessel, and transported to Brest. After imprisonment in the Chateau de Joux, he was carried to Besançon, and confined in a subterranean prison, where he languished in cold and darkness through

Page 9

the winter,--he who had been reared under the tropical sun of his beloved island!--and died in 1803.

The treacherous, cruel, and unjust imprisonment of Toussaint drew upon Bonaparte severe and just condemnation. We have only to study the closing days of the conqueror, and to see him "chained like a vulture" on the rock of St. Helena, a spectacle for the world, to turn almost with envy to the dark and dreary winter prison where Toussaint ended his life, heroically and without one complaint;-- * The Castle of Joux in Franche-Comté. ** Rogers's "Italy."

"That dungeon-fortress* never to be named,

Where, like a lion taken in the toils,

Toussaint breathed out his brave and generous spirit.

Ah, little did he think who sent him there,

That he himself, then greatest among men,

Should in like manner be so soon conveyed

Athwart the deep,--and to a rock so small

Amid the countless multitude of waves,

That ships have gone and sought it, and returned,

Saying it was not!"**

Page 10

We quit this melancholy contemplation for the subject of our memoir, and go back to the happiest period of Pierre Toussaint's life. John Bérard successfully cultivated the plantation, treading in his father's footsteps, and with patriarchal care exacting a due proportion of labor, which he rewarded with kindness and protection. Wealth flowed in upon him. He was tenderly attached to his cousin, and finally married her. She had resided much on the plantation, and partook of his attachment to the slaves, particularly to Zenobe and her descendants.

"I remember her," said Toussaint, "when the bridal took place. She was very pale; her health was always delicate, but she looked so lovely, and we were all so happy! and Rosalie and I were never tired of gathering flowers for her, and we used to dance and sing for her amusement." In one year after her marriage she began to droop. "Ah!" said Toussaint, "I can see her as she lay upon the couch, panting for air,--all so beautiful, outside and in; then Rosalie and I would stand

Page 11

at opposite corners of the room and pull the strings of a magnificent fan of peacock's feathers, swaying it to and fro, and we would laugh and be so gay, that she would smile too; but she never grew strong,--she grew weaker."

She expressed a wish to go to Port-au-Prince;--probably her near relations resided there. She took Toussaint and Rosalie with her.

About this time the troubles in St. Domingo began. The revolutionary doctrines of France could not fail to influence her colonies. Hayti looked at the contest for liberty and equality with the keenest interest. The wealthy proprietors joined in the universal cry. But they had no idea of participating these blessings with the free-born colored people; they still meant to keep them in a subordinate state. A large number of wealthy and intelligent merchants, but a shade or two darker than their aristocratical brethren, stoutly contended for an equal share in administering the affairs of the colony, and claimed

Page 12

their right of representation, of sharing in the distribution of offices, and all the immunities of free and independent citizens. This was by no means the idea of the nobility of St. Domingo; and when France subsequently espoused the cause of the mulatto free population, and when the Abbé Grégoire spoke eloquently for them in the National Assembly, the hatred of the whites knew no bounds. As yet only private attempts at annoyance had arisen on both sides; but a dark storm seemed threatening, for the disaffected had talked of offering their colony to the English. No fears were entertained of the slaves; they were considered as machines in the hands of their masters, and, without principles, wills, or opinions of their own, they were neither dreaded nor suspected; and so the contest seemed to be between the nobility and the free people of color.

Monsieur Bérard willingly consented to the change his young wife proposed in going to Port-au-Prince, hoping she might derive benefit from it. But no favorable symptoms occurred;

Page 13

her decline was rapid, and in one short month from her arrival she breathed her last, in her twenty-first year.

Toussaint and Rosalie returned to Latibonite at St. Mark's. It was most touching to listen to Toussaint's description of his young mistress, as he saw her every day declining, yet then unconscious that he should soon see her no more!

The attachment of these two classes, of mistress and slave, might almost reconcile us to domestic slavery, if we only selected particular instances. But without suggesting whether there are few or many such, we may all understand the danger of institutions which leave to ignorant, passionate men the uncontrolled exercise of power. It is not, however, on the ground of individual treatment that the philanthropist, the statesman, and the moralist found their strongest arguments against slavery; it is on the eternal rights of man, on the immutable laws of God; and till it can be proved that the negro has no soul, we cannot plead for him merely on

Page 14

the score of humanity, or place him simply under that code of laws which, imperfectly it is true, protects the noble horse from abuse. It was for his divine right that the Abbé Grégoire spoke so successfully.

We now arrive at what formed the great era of Pierre Toussaint's life. He had hitherto lived in the midst of luxury and splendor; for the apartments of Monsieur Bérard, as he describes them, were furnished in a style of expense that exceeded even modern prodigality. All the utensils of his mistress's chamber were of silver lined with gold; the dinner service was of the same metals. In St. Domingo, the tropical climate yielded its abundant fruits, and the hardships of winter were never known.

Monsieur Bérard married a second wife, and still all was successful and prosperous. But this was not long to last. The troubles had now begun. He earnestly wished to preserve a neutral position; but he found this impossible. His immense property became involved; his perplexities increased in various

Page 15

ways; and he determined to quit the island, and repair to the United States to pass a year, meaning to return when the storm was over and tranquillity restored. He took with him five servants, including Toussaint and his sister Rosalie.

New York was their place of destination. Monsieur Bérard, by the kindness of a friend, found a house ready furnished, of which they took immediate possession. He brought sufficient funds to enable them to live in good style for more than a year. Madame Bérard also brought over her sisters, one of whom had married General Dessource.

They formed at this time a gay and united family, with plenty of society and amusement. "I remember," said a lady who was well acquainted with them, "Toussaint among the slaves, dressed in a red jacket, full of spirits and very fond of dancing and music, and always devoted to his mistress, who was young, gay, and planning future enjoyment."

All went on pleasantly with them for a

Page 16

year; but intelligence from the island grew more and more alarming, and M. Bérard thought it necessary to return to St. Domingo, to look after his affairs. Previously to his going, he mentioned to Toussaint that he wished him to learn the hair-dressing business, and a Mr. Merchant, who dressed the hair of Madame Bérard, engaged to teach him for fifty dollars. M. Bérard, placing the property he had brought over to this country in the hands of two respectable merchants, took leave of his wife, as he thought for a short season. In the mean time, she remained tranquil and hopeful, talking over her plans of living with Toussaint, telling him her projects for the time to come, and concerting pleasant surprises for her husband when he should arrive. She was much pleased with Pierre's success as a coiffeur, and said how gratified M. Bérard would be to find he had succeeded so well. Those who have known Toussaint in later years will easily comprehend the manner in which he was adopted into the confidence of his employers through life. His

Page 17

simple, modest deportment disarmed all reserve; he was frank, judicious, and unobtrusive. A highly cultivated and elegant woman said, "Some of the pleasantest hours I pass are in conversing with Toussaint while he is dressing my hair. I anticipate it as a daily recreation." The confidence placed in him by his master and mistress he considered a sacred trust.

Melancholy letters arrived from M. Bérard. His property was irreclaimably lost; and he wrote that he must return, and make the most of what he had placed at New York. This letter was soon followed by another, announcing his sudden death by pleurisy.

Madame Bérard had not recovered from this terrible shock, when the failure of the firm in New York to whom her property was intrusted, left her destitute.

"Ah!" said Toussaint, "it was a sad period for my poor mistress; but she believed--we all believed--that she would recover her property in the West Indies. She was rich in her own right, as well as her husband's,

Page 18

and we said, 'O madam! you will have enough.'"

But this present state of depression was hard indeed to one who had always lived in luxury. The constant application for debts unpaid was most distressing to her; but she had no means of paying them, and she could only beg applicants to wait, assuring them that she should eventually have ample means.

Toussaint entered into all her feelings, and shared her perplexities; and though he had scarcely passed boyhood, he began a series of devoted services.

He was one day present when an old friend called on her, and presented an order for forty dollars, thinking her husband had left the money with her, and by no means divining her state of destitution. She assured him he should have the money, and requested him to wait a short time; she considered it peculiarly a debt of honor. When he went away, she said to Toussaint, "Take these jewels and dispose of them for the most you can get."

He took them with an aching heart, contrasting

Page 19

in his own mind her present situation with the affluence to which she had always been accustomed. He had by industry begun to make his own deposit; for, as a slave, he was entitled to make the most of certain portions of his time. In a few days he went to his mistress, and placed in her hands two packets, one containing forty dollars, the other her own valuable jewels, upon which the sum was to have been raised. We may imagine what were her feelings on this occasion!

At another time, the hair-dresser of whom Toussaint had learnt his trade called on Madame Bérard for the stipulated sum. Toussaint heard her reply, with faltering voice, "It was not in her power to pay him; he must wait." Toussaint followed him out, and entered into an engagement to pay the sum himself, by instalments, and at length received an acquittal, which he presented to his mistress. She was at first alarmed, and said, "O Toussaint, where can you have got all this money to pay my debts!" "I have got some customers, Madame," said he; "they

Page 20

are not very fashionable, but Mr. Merchant very good,--he lets me have them; and besides, I have all the money that you give me, my New Year presents,--I have saved it all." She was much surprised, and told him she did not know when she should be able to repay it. He told her it was all hers, that he never wanted that money again; that he had already good customers, and expected every day more and more. "My poor mistress," said Toussaint, "cry very much."

From this time he considered his earnings as belonging to Madame Bérard, except a small deduction, which he regularly set aside, since he had a purpose to execute which he communicated to no one. His industry was unceasing,--every hour of the day was employed; when released, his first thought was his mistress, to hasten home and try to cheer her.

In this way he alleviated the burden of her troubles; his affectionate, loving heart sympathized in all her sorrows. His great object was to serve her. He was perfectly contented

Page 21

with his condition. Though surrounded New York by free men of his own color, said that he was born a slave,--God had thus cast his lot, and there his duty lay.

Two of Madame Bérard's sisters died, and the family was thus broken up. A gentleman from St. Domingo, Monsieur Nicolas, who had left the island about the same time with the Bérard family, cherished the hope, which many entertained for years, of recovering his property. In the mean time, like other unfortunate emigrants, he found himself obliged to convert those accomplishments which had made a part of his education to the means of living. For some time he performed as a musician in the orchestra of the theatre, and gave lessons in music to a number of scholars. He was a constant friend of Madame Bérard, and they at length married. For some time they were sanguine in the hope of returning to the island, and taking possession of their property, but constant disappointment and perpetual frustration of her hopes wore upon Madame Nicolas's naturally delicate frame, and her

Page 22

health became much impaired. Monsieur Nicolas was a kind and tender husband, and did all in his power to alleviate her indisposition, and administer to her comfort.

Toussaint, in the mean time, was industriously pursuing his business as a hair-dresser, and denying himself all but the neat apparel necessary for his occupation, never appropriating the smallest sum of his earnings to his own amusement, though at that season of youth which inclines the heart to gayety and pleasure. Belonging to a race proverbially full of glee, and while on the island, among his sable brethren, first in the dance and song, he now scrupulously rejected all temptation for spending money, and devoted his time to his mistress. We have before alluded to the care with which he hoarded his gains. Besides the pleasure of surprising Madame with little delicacies, he had evidently another object in accumulating, of which he did not speak. He was successful, and took a respectable stand as a hair-dresser. His earnings belonged in part to his mistress; but as she

Page 23

grew more sick, he delighted to add voluntarily the portion which belonged to himself. His sister Rosalie was a constant and faithful attendant, but Toussaint was both a companion and friend. Madame Nicolas had an affection of the throat, and was obliged to write rather than converse; to this faithful friend she used to express her wants on little scraps of paper, and he invariably supplied them, while she consoled herself with the idea that he would be fully indemnified eventually from her own property. He had no such belief; he wished for no return. In later years he said, "I only asked to make her comfortable, and I bless God that she never knew a want."

He strove to supply her with the luxuries of her tropical climate,--grapes, oranges, lemons, and bananas; he regularly procured jellies and ice-creams from the best confectioners, and every morning went to market to obtain what was necessary for her through the day. His business of hair-dressing proved very lucrative, and kept him regularly employed. He attended one lady after another,

Page 24

in constant succession, and when released from his duties hastened to render new services to his invalid mistress. She felt that influence which a strong and virtuous mind imparts, and communicated to him her perplexities. He often read to her, and, adds one of his most cherished and faithful friends,

*

* Mrs. Philip J. Schuyler, whose death took place in 1852, preceding Toussaint's about fifteen months. She was the daughter of Micajah Sawyer, M.D., of Newburyport. To her notes the author of this memorial is principally indebted.

"Perhaps this scene, so touching to his feelings and elevating to his heart, in contemplating a being honored and beloved, gradually wasting away, may have been the foundation of that piety which has sustained him through life, and become deeply seated in his breast. He is a Catholic, full in the faith of his Church, liberal, enlightened, and always acting from the principle that God is our common Father, and mankind our brethren."

Toussaint seemed to understand the constitution of Madame Nicolas's mind; he reflected that she had always been accustomed to

Page 25

society, and that the excitement of it was necessary for her. "I knew her," said he, "full of life and gayety, richly dressed, and entering into amusements with animation; now the scene was so changed, and it was so sad to me! Sometimes, when an invitation came, I would succeed in persuading her to accept of it, and I would come in the evening to dress her hair; then I contrived a little surprise for her. When I had finished, I would present her the glass, and say: 'Madame, see how you like it.' O, how pleased she was! I had placed in it some beautiful flower,--perhaps a japonica, perhaps a rose, remarkable for its rare species, which I had purchased at a greenhouse, and concealed till the time arrived." Sometimes, when he saw her much depressed, he would persuade her to invite a few friends for the evening, and let him carry her invitations. When the evening arrived, he was there, dressed in the most neat and proper manner, to attend upon the company; and he was sure to surprise her by adding to her frugal entertainment ice-cream and cakes.

Page 26

It appeared his great study to shield her from despondency,--to supply as far as possible those objects of taste to which she had been accustomed. In this constant and uniform system, there was something far beyond the devotion of an affectionate slave; it seemed to partake of a knowledge of the human mind, an intuitive perception of the wants of the soul, which arose from his own finely organized nature. In endeavoring to procure for her little offerings of taste to which she had been accustomed, he was unwearied: not because they had any specific value for himself, but simply for the pleasure they gave to her. All he could spare from his necessary wants, and from the sum which he was endeavoring to accumulate, and to which we have before alluded, was devoted to his mistress. "Yet one rule," said he, "I made to myself, and I have never departed from it through life,--that of not incurring a debt, and scrupulously paying on the spot for every thing I purchased."

But not all this affectionate solicitude, nor

Page 27

the cares of a kind husband, for such was Monsieur Nicolas, could stay the approach of death. Her strength rapidly declined, and every day Toussaint perceived a change. At length she was confined to her bed. One day she said to him, "My dear Toussaint, I thank you for all you have done for me; I cannot reward you, but God will." He replied, "O Madame! I have only done my duty." "You have done much more," said she; "you have been every thing to me. There is no earthly remuneration for such services."

A few days before her death, she called Toussaint to her bedside, and, giving him her miniature, told him she must execute a paper that would secure to him his freedom. Monsieur Nicolas, who was present, said, "Save yourself this exertion,--every thing you wish shall be done." She shook her head, and replied, "It must be done now."

Her nurse from infancy, Marie Boucman, had accompanied her mistress to New York. She was aunt to Toussaint. Free papers were given to this faithful domestic by Madame

Page 28

Bérard and her sisters in St. Domingo, in which we find this sentence: "We give her her freedom in recompense for the attachment she has shown us, since the troubles which afflict St. Domingo, and release her from all service due to us."

This woman, whom she tenderly loved, she committed to Toussaint's care in a most touching manner. "As you love my memory," said she, "never forsake her; if you should ever quit the country, let her go with you."

The deed was legally executed which secured to Toussaint his freedom, and which she had strength to sign. She then desired him to bring a priest, made her confession, received her last communion, and died at the age of thirty-two.

She was a most gentle, affectionate woman, and deeply attached to those around her. We think a letter of hers, addressed to her negro nurse, will not be uninteresting in this connection. It appears that Marie, after seeing her mistress safely settled in New York, returned

Page 29

again to see her family, as among Toussaint's papers the following letter is found from Madame Nicolas:--

"New York.

"How, my dear Marie! is this the way you keep your promise? You told me you would write to me as soon as you reached the Cape. Every one has written, but I find no little note from you. Have you forgotten me, my dear Memin? This thought makes me too sad. I was sorry to part with you, but I would not tell you all I felt, lest you should have changed your mind, and passed the cold winter here. So now you are at the Cape.

"I hear you reached there after a voyage of thirty days. Were you ill, my dear Memin? How are you now? I am impatient to hear from you. Tell me news of your children. If it had not been for this last intelligence, we should by this time have been at the Cape; as soon as the French troops arrive, we shall return. If you are not well off, come back to me, and we will all go to St. Domingo together. You know that you are a second

Page 30

mother to me; you have filled the place of one. I shall never forget all you have done for my poor sisters, and if efforts could have saved any one, I should now have them all. But God has so ordered it, and his will be done! Ah, dear Memin, your religion will support you under all your sufferings,--never abandon it!

Adieu! Write me soon, or I shall think you do not love me any longer.

"I am, always, as you used to call me, your

"BONTÉ."

The little fancy names of endearment were peculiar to the West Indian mistresses and slaves. Marie Boucman returned again to New York.

Page 31

PART SECOND.

AFTER the death of Madame Nicolas, Toussaint remained with her husband. M. Nicolas lived on the first floor of a house, with one servant, who was his cook; and Toussaint continued to go to market for him, and to perform many gratuitous services. In this manner they resided together for four years, in Reed Street.

Marie Boucman had also a room on the same floor of the house, and supported herself by her industry.

Rosalie, who was still a slave, was engaged to be married, and Toussaint at once put into execution the project he had long contemplated, and for which he had been accumulating

Page 32

the needful money by degrees. This was the purchase of his sister's freedom. Of his own freedom he never seems to have thought, but it was all-important to him that Rosalie should enter life under the same advantages as her husband and those around her. With a delicacy for which he was always remarkable, he never mentioned this subject to Madame Nicolas, though we cannot but think that she would at once have bestowed it without price. Probably the subject never occurred to her.

Toussaint paid his sister's ransom, and she was soon married. He had now time to think of himself. He had formed an attachment for Juliette Noel, and they were married in 1811, and continued to live in the same house with Monsieur Nicolas, having two rooms in the third story.

At the end of four years M. Nicolas left New York for the South, and a constant interchange of letters and kind offices on Toussaint's part took place, continuing till the death of M. Nicolas. The following

Page 33

extract from a letter of M. Nicolas to Toussaint, written long after, will show how highly this gentleman respected and appreciated him:--

"July, 1829.

"I have received your letter, my dear Toussaint, and share very deeply the sorrow which the loss of your niece must bring upon you. No one knows better than I, how much you were attached to her; however, as you say very truly, we must resign ourselves to the will of God. I am sorry to hear that Juliette has been ill, and hope that your next letter will speak of her reëstablished health. I have not written to you for a long time, my dear Toussaint,--not that I do not think of you, or that I love you less, but I was troubled because I was not able to send you any thing; however, I know your heart, and feel quite sure you will not impute this delay to want of inclination. You have no idea how unhappy I am when I cannot meet little debts. But, my dear Toussaint, I fail every day; I am at least ten years older than when

Page 34

I last saw you. Both courage and strength begin to fail, and add to all this, that I do not hear a word from France about our claims. You can understand my sad situation; but a few years longer will put an end to my misery. However, I do not despair to see you again before I pay the debt to Nature. In the mean time think of me, write to me, and be assured that you will always find me your true friend,

"G. NICOLAS."

A period of prosperity seemed now to have dawned on the faithful Toussaint. He was happy in his conjugal connection. Juliette was of a gay, cheerful disposition, and fully estimated the worth of her husband. Indeed, how could it be otherwise? She saw him universally respected, and treated as a friend by every one. As a hair-dresser for ladies, he was unrivalled: he was the fashionable coiffeur of the day; he had all the custom and patronage of the French families in New York. Many of the most distinguished ladies of the city employed him; we might mention not a few who treated him as a particular friend.

Page 35

A pleasant novel, said to be written by a Southern lady, but published in New York, "The Echoes of a Belle," gives a graphic description of Toussaint as a hair-dresser: "He entered with his good tempered face, small ear-rings, and white teeth, a snowy apron attached to his shoulders and enveloping his tall figure."

He went continually from house to house performing the office of hairdresser, and was considered quite as a friend among the fair ladies who employed him. They talked to him of their affairs, and felt the most perfect reliance upon his prudence; and well they might, for never in this large circle was he known to give cause for an unpleasant remark. Once a lady, whose curiosity was stronger than her sense of propriety, closely urged him to make some communication about another person's affairs. "Do tell me, Toussaint," said she, "I am sure you know all about it." "Madam," he replied with dignity, though with the utmost respect, "Toussaint dresses hair, he no news journal."

Page 36

At another time he was requested to carry a disagreeable message. He immediately answered, "I have no memory."

Toussaint had delayed his marriage with Juliette, till he saw his sister Rosalie, as he believed, well settled in life, and mistress of her own freedom; but all his affectionate endeavors could not secure to her the happiness he had so fondly anticipated.

In 1815 Rosalie had a daughter born, but her prospects had been cruelly frustrated; her husband proved idle and dissipated, and Toussaint almost entirely supported her. The little infant was named Euphemia by her uncle, but the mother's health rapidly declined. Dr. Berger was her able and humane physician; he pronounced her in a decline. Juliette took home the infant of six months old, and brought her up by hand. Very soon the mother was removed to Toussaint's roof, and, after lingering a few months, breathed her last. Previously to this event, Marie Boucman had died, carefully watched over by Toussaint,

Page 37

who considered her as a legacy bequeathed to him by his mistress.

Euphemia was a sickly, feeble child. Dr. Berger did not give much encouragement that she would live; but Toussaint, who was always sanguine, fully believed that her life would be granted to them. Both his and Juliette's assiduity was unremitting for her; no parents could have done more. Every day Toussaint took the feeble little creature in his arms, and carried her to the Park, to the Battery, to every airy and pleasant spot where the fresh breezes sent invigorating influence, hoping to strengthen her frame and enable her lungs to gain a freer respiration. The first year of her life was one of constant struggle for existence, but God blessed their untiring efforts, and the frail plant took root and flourished.

An incident occurred in Toussaint's life about this time, which deeply interested him. He was summoned to the City Hotel to dress the hair of a French lady, who was a stranger. She could speak no English, and

Page 38

therefore was very glad to converse with him in her native language. She spoke to him of her lonely feelings, and of her painful separation from a dear friend, who was now in Paris. Toussaint told her there were many agreeable French families in New York. "Yes," she said, "she had letters to a number, but no one could supply the place of her Aurora Bérard."

It was the first time he had heard his godmother's name mentioned for many years. Could it be her of whom the lady spoke? A few inquiries settled the matter; it was indeed the same,--she who in the happy period of his infancy had stood sponsor at the baptismal font, who had sometimes visited his dreams, but of whose very existence he was doubtful. How many touching recollections arose to his mind! Again the palmy groves of his beautiful native isle were before him; again he was gathering fruits and flowers for his little godmother, and performing a thousand antic sports for her amusement. But such delusions are momentary;

Page 39

he was once more Toussaint the hairdresser, and hastened back to communicate this delightful surprise to his faithful Juliette. The lady was soon to leave the city and return to Paris; he wrote to Aurora by her, but from some unfortunate mistake, when he carried his letter she had sailed.

His disappointment was great, but in three months afterwards he received the following letter from Aurora, saying she had heard of him through her friend, and expressing her affection for his grandmother and mother, and her kind interest in him.

"À MONSIEUR TOUSSAINT, Coiffeur.

*

"Paris, November 27, 1815.

* It is but justice to observe, that all the original letters in this volume addressed to Toussaint are translations from the French.

"Madame Brochet, on her return to this city, fifteen days since, has given me intelligence of you, my dear godson. I, as well as my brothers and sisters, am truly grateful for the zeal that you manifested in wishing to learn

Page 40

something of us, and for the attachment which you still feel for us all. After the information that Madame Brochet gave me, I cannot doubt that you will be glad to receive a letter from me. I write to you with pleasure, and I have felt much in learning that you are prosperous in your affairs, and very happy. As to us, my dear Toussaint, we have never quitted Paris. Our situation is not happy. The Revolution deprived us of all our property. My father was one of the victims of that frightful period. After being confined six weeks in prison, and under constant inspection of the government, on their own place, near Paris, both he and my mother died of grief. My brothers and sisters are married, but I am not, and am obliged to make exertions to live which have impaired my health, which is now very poor. Were it not for that, I might be tempted to accomplish the voyage you desire; but I am not the less sensible to the offers you make me, through Madame Brochet, and I thank you sincerely. It is consoling to me to know,

Page 41

amidst all my troubles, that there exists one being who is so much attached to me as you are. I wish we could live in the same town, that I might give you details by word of mouth about my family. [Here follows a short account of her brothers and sisters and their children.]

"Write to me, my dear Toussaint, about your wife; I know you have no children. Do you know any thing relating to St. Domingo? What has become of all our possessions, and our ancient servants? Tell me all you know about them. Have you any of your former companions in your city? My nurse Madelaine and your mother, are they still living? Tell me every thing you know. Adieu, my dear godson. Do not forget to write to me, and depend upon the affection of your godmother, who has never forgotten you, and who loves you more than ever, since she finds you have always preserved your attachment to

"AURORA BÉRARD."

This letter Toussaint immediately answered, and accompanied it by a dozen

Page 42

Madras handkerchiefs. The French ladies highly prized this article, for at that time they were considered a most tasteful and fashionable head-dress. Juliette always wore them, and was often asked to teach ladies to fold them, and give them the graceful and picturesque air which she gave to her own. From this time letters were frequently exchanged between Aurora and her affectionate godson. He sent her Canton crape dresses, and other articles which were of great price in France, and all of the best quality. These presents she gratefully acknowledged, but there is a very natural fear expressed that he has sent too expensive ones. In alluding to the crape dresses, she writes: "To judge from the dearness of the articles here, I fear you may have made some sacrifice to purchase them, and this idea gives me pain."

Soon after the letter sent by Aurora, Toussaint received the following from Monsieur Bérard, the brother of Aurora:--

"Paris, 1815.

"I have learned with pleasure and gratitude,

Page 43

my dear Toussaint, all that you have done for my brother Bérard and his widow, and the attachment you still entertain for our family. Since I have known all this, I have wished to write to you, and express the love and esteem I feel for you. It is from Mesdames D--, R--, and C--, I have received these details. I was so young when I left St. Domingo, that I should certainly not recognize your features, but I am sure my heart would acknowledge you at once, so much am I touched with your noble conduct. All my family share these feelings, but more particularly my sister Aurora. I do not despair of returning to St. Domingo, and of finding you there, or in the United States, if I take that route.

"Adieu, my dear Toussaint. Give me news of yourself, and believe in my sincere friendship.

"BÉRARD DU PITHON."

This renewal of his early intercourse with the Bérard family was a source of great happiness to Toussaint. We regret that none of

Page 44

his letters to his godmother remain; but hers sufficiently prove the affection on both sides. He even proposed removing to Paris with Juliette, and consults her on the eligibility of such a step. Her answer, an extract from which is here given, is most kind, considerate, and disinterested. His wish is evidently to support her, as he had his mistress, by his own industry.

"Paris, December 1, 1818.

"I have seen Mr. S--to-day. This gentleman appears to be much attached to you, which gives me great pleasure. We talked together of your wish to come to France. If I only consulted my own desire to see you, I should say, come at once; but your happiness, my dear godson, is what I think of above all things, and since every one from New York tells me that you are happy, highly esteemed, and much beloved by most respectable persons there, would you be as well off here? Those who know your resources better than I can, may advise you with more confidence. If I were rich, this would be of little consequence.

Page 45

I should call you near to me, for I should be too happy to have a person to whom I could give all my confidence, and of whose attachment I should feel certain. This would be too desirable for me, not to ask you to come; but my position is a sad one. I could not be useful to you, and I fear you would not be so happy as you deserve. I speak to you like a mother, for be assured that your godmother would be most happy to see you. Although I have not seen you since my childhood, I love you like a second mother, and I can never forget the services you have rendered to my brother and his wife. My brothers and sisters share these feelings, and we never speak of you without emotion."

The following is from another letter of Mademoiselle Bérard, of a little later date:--

"Your friends have not left me ignorant of all the good you do, and that you are the support of the colored women of our plantation. You must induce them to work, for you should not give away all your earnings. You must think of yourself, of your wife, and

Page 46

niece, whom you look upon as a daughter. I hear that Hortense is with you; she belonged to me, and must be young enough to work and support herself. You will do her a service if you induce her to work; tell her so from me. It gives me pain to find that you are still without news of your family; here we know nothing. Let us trust in Providence. Your feelings of piety make me believe that God is also your consolation; you are right, and the assurance that every one expresses of your religious character gives me great pleasure. I feel deeply, my dear godson, all that you tell me of your desire to see me, and to serve me. I understand your noble feelings. Your attachment adds much to my happiness, for there are so few persons in the world who resemble you, that I appreciate you as you deserve."

This pleasant intercourse continued for many years. At length the following letter came:--

"July 28, 1834.

"You are already in sorrow, my dear Toussaint,

Page 47

and the sad news I must announce to you will only augment it. Two months have passed since your beloved godmother was taken from us by sudden death. My heart is so deeply oppressed by this affliction, that I can scarcely write. A few days before her death she spoke of you; she wished to write to you, being very anxious at not having heard from you for a long time. What pleasure she would have experienced in receiving your last letter, which arrived about fifteen days since! The news I send to you will be sad, but you may be assured of the affection that every member of our family feels for you, and myself in particular. My dear Toussaint, it will be a great pleasure to hear from you. I hope that Divine Providence will mitigate the painful remembrance of your adopted niece. Man can offer only words, but God, who sends the affliction, can diffuse into our souls all necessary fortitude. May you have recourse to the throne of grace, and that blessed future life where all our thoughts ought to centre. I hope that

Page 48

your dear godmother now enjoys perfect happiness; since the death of our parents she has suffered much. Indeed, for several years she has experienced the pain of rheumatism in frequent attacks; her patience and resignation to the will of God, and her entire confidence in the Mother of God, will be her propitiation. I love to think that God is good; he knows our hearts, and will judge us."

The letter closes with assurances of the love and gratitude of all the family. It is from Madame de Berty, the sister of Aurora Bérard.

Toussaint's situation was now prosperous in every way; he lived in a pleasant and commodious house, which was arranged with an air of neatness, and even gentility. Juliette was gay and cheerful; she loved her little parties and reunions; they had wealth enough for their own enjoyment, and to impart to those who were in want. They were conscientious Catholics; charity was for them, not only a religious duty, but a spontaneous

Page 49

feeling of the heart. One instance may here be mentioned of the quiet, silent manner in which they bestowed their good deeds. A French gentleman, whom Toussaint had known in affluence, a white man, was reduced to poverty; he was sick and suffering, craving a delicacy of food which he had no means to procure. For several months Toussaint and Juliette sent his dinner, nicely cooked, in such a way that he could not suspect from whom it came. "If he had known," said Toussaint, "he might not have liked it; he might have been proud." "Yes," said Juliette, "when Toussaint called to see him sometimes, he would say, 'O, I am well known! I have good friends; every day somebody sends me a nice dinner, cooked by a French cook'; and then perhaps he would enumerate the different viands. My good husband would come home, and tell me, and we would laugh very much."

When Euphemia was about seven years of age, a friend of Toussaint's proposed her being taught music. Her uncle was

Page 50

wholly opposed to the idea; he thought it would involve much expenditure of time and money, and he saw no advantage to be derived from it. He said the little girl had her own sweet voice, and sang like the birds, yet they were not taught music.

Some time after, a warm and true friend of Toussaint's, who knew his worth, urged him to let her give lessons to Euphemia in music; this was the lovely and amiable Miss Metz.

* * Now Mrs. Moulton, residing in Paris.

She persevered in going to his house, with her notes in her hand. Finally he consented, on her suggesting that it might hereafter become a means of support to his niece. This representation, with her gratuitous instruction, obviated his objections; but then another arose. So tenderly guarded was the little Euphemia, that he never suffered her to go into the streets alone, and he felt that his time could not be spared to attend her. Miss Metz, in her benevolent zeal, beautiful and young as she was, offered to come herself and

Page 51

give the lessons. But Toussaint's never failing sense of propriety would not allow of this arrangement; and Juliette, her good aunt, accompanied her three times a week to her kind young friend, to receive her lesson. This was continued for four years. Toussaint purchased a piano, and she made all the progress that could be expected.

It was obvious, however, that her religious and moral cultivation was the first object with her uncle; his tenderness and judgment were constantly blending their efforts for the improvement of her heart and mind. He was most desirous to make her a being who would be capable of fulfilling her duty towards her Creator and her fellow-beings. No household instruction was omitted. Juliette was an excellent housekeeper, and the little girl was her aunt's assistant. They were constantly inculcating lessons of charity with her pleasures.

Toussaint was much interested in the Catholic Orphan School for white children. "On Euphemia's saint's day," he said, "I

Page 52

always took her with me to the cake shop, and we filled a large basket with buns, jumbles, and gingerbread, which we carried to the Orphan Asylum." I said to him, "You let her give them to the children?" "O no, madam! that would not be proper for the little black girl. I tell her, ask one of the sisters if she will give them to the children. When they were sent for, Euphemia stood on one side with me to see them come in, and when they received the cake they were so glad, and my Euphemia was so happy! One day as we went there, she asked me, 'Uncle, what are orphans?' I answered, they are poor little children that have no father or mother. For a moment she looked very sad; then she brightened up and said, 'But have they no uncle?' O madam! I feel so much, so much then, I thank God with all my heart."

He had the happy art of making every one love him, by his affectionate and gentle manner. His deportment to his wife was worthy of imitation even by white men. She was

Page 53

twenty years younger than he was, and no doubt had a will of her own; but she always yielded it to Toussaint's, because she said she was not obliged to do it. A friend related to me an amusing scene she witnessed. Juliette was about to purchase a mourning shawl, for she had just lost a relative. The shawls were exhibited. "How do you like this for mourning?" said she to Toussaint. "Very pretty," he replied. "I think," said she, "it is handsome enough for church." "O yes! very good for that." "Don't you think it will do to wear if it rains?" "O, certainly!" "I think it will do sometimes to wear to market, don't you?" "Very nice," he replied; "pray take it, Juliette; it is good for mourning, for church, for rain, and for market; it is a very nice shawl." Juliette secured it, much satisfied with her bargain.

Since I began this memoir, I have learned that Toussaint purchased Juliette's freedom before he married her. To this circumstance he did not allude in the history of his early life; probably from that sense of delicacy for

Page 54

which he was so remarkable. He went immediately after the ceremony to the City Hall to have the papers ratified.

Euphemia was taught reading, writing, and all pursuits adapted to her age. When she was five or six years old, she was a most engaging child; her manners were strikingly gentle, her countenance and expression pleasant, and her behavior excellent, modelled upon her uncle's ideas of obedience and deference, which he had always practised himself. He often contrived to throw in a word of admonition to the children round him; to one little girl where he visited he said, "Miss Regina, your mother very good; obey her now, you will be happy when you are older." This lesson years after she gratefully mentioned.

How devotedly he loved his little niece, many will yet remember. She seemed fully to understand his affection, and clung to him as the vine clings to its support. She was delicately formed, and her figure slight; he would put his arm around her, and say, "My

Page 55

Euphemia," with a tenderness that was affecting; there appeared something sacred in his love, as if he felt that God had intrusted her to his protection, and, by depriving her of all other earthly support, had made him responsible for her future welfare.

When she was about twelve years old, Toussaint procured her a French teacher. French was his own and his wife's language, of course that of his family; but he wished her to speak it grammatically. He also let apartments in his house to a respectable white woman, a widow, who taught Euphemia English, and who after a while collected a small school of young children.

It was a striking trait in his character, that every thing in which he engaged was thoroughly done; there was a completeness in his plans, and their execution, which commanded confidence, and which perhaps was one of the causes of the respect which he inspired. This sometimes led ladies to say, that Toussaint "was a finished gentleman." His moral qualities, however, gave him this distinction; for with

Page 56

the most perfect modesty he knew exactly what was due to others and to himself, while his heart overflowed with that Christian kindness which far surpasses mere worldly politeness. He was observant of all the forms of the Roman Catholic Church; through winter and summer he missed no matin prayers, but his heart was never narrowed by any feeling as to sect or color. He never felt degraded by being a black man, or even a slave; for he considered himself as much the object of Divine protection as any other human being. He understood the responsibility, the greatness, of the part allotted him; that he was to serve God and his fellow-men, and so fulfil the duties of the situation in which he was placed. There was something truly noble and great in the view that he took of his own nature and responsibility. No failure on the part of the master could in his opinion absolve a slave from his duty. His own path was marked out; he considered it a straight one and easy to follow, and he followed it through life. He was born and brought up

Page 57

in St. Domingo at a period which can never return. In the large circle around him there were no speculations upon freedom or human liberty, and on those subjects his mind appears to have been perfectly at rest. When he resided in New York, he still preserved the same tranquil, contented state of mind, yet that he considered emancipation a blessing, he proved, by gradually accumulating a sum sufficient to purchase his sister's freedom. It was not his own ransom for which he toiled, but Rosalie's, as has been previously said, for he wished that she might take her station as a matron among the free women of New York. But he does not appear to have entertained any inordinate desire for his own freedom. He was fulfilling his duty in the situation in which his Heavenly Father chose to place him, and that idea gave him peace and serenity. When his mistress on her death-bed presented him his liberty, he most gratefully received it; and we fully believe he would not have suffered any earthly power to wrest it from him.

Page 58

There are many in the present day who will view this state of mind as degrading, who consider the slave absolved, by his great primary wrong of bondage, from all obligation to the slaveholder. Not such was Toussaint's idea. He did not ask, like Darwin's African slave, "Am I not a man and a brother?" but he felt that he was a man and a brother. It was the high conception of his own nature, as derived from eternal justice, that made him serene and self-possessed. He was deeply impressed with the character of Christ; he heard a sermon from Dr. Channing, which he often quoted. "My friends," said Channing, "Jesus can give you nothing so precious as himself, as his own mind. May this mind be in you. Do not think that any faith in him can do you good, if you do not try to be pure and true like him." We trust many will recognize the teachings of the Saviour in Toussaint's character.

Madame Toussaint loved Euphemia with the same affection that she would have bestowed on her own children, had she possessed

Page 59

any. She was an excellent wife, and respected her husband's feelings in all things. She was gay and good-humored, had a most pleasant, cordial laugh, and a ladylike deportment. Her figure and features were fully developed, and much more African than Toussaint's, though she was several shades lighter. Their house was the abode of hospitality, and many pale faces visited them.

At the age of fourteen, Euphemia seemed to have attained firmness and strength, and we can hardly imagine more domestic happiness, or a picture of more innocent enjoyment, than Toussaint's household afforded. His peculiar devotedness and tenderness towards Euphemia seemed to be richly rewarded. He had no idea of making her a being that would be incapable of fulfilling the daily avocations of life. She was carefully taught all domestic duties; it was her great pleasure to aid her aunt, and she was never happier than when she was allowed to assist in the work of the family. When she grew old enough to make her uncle's coffee, it

Page 60

would be difficult to say which received most pleasure, the uncle or the niece, the first time she brought it to him, and said, "I made it all myself."

Toussaint's friends knew well they could afford him no higher gratification than by bestowing kind attentions upon this child of his adoption and darling of his heart. Many and constant were the little presents she received. Toys, dolls, and bonbons were the early gifts; afterwards books, and those things suitable to her increasing years. He always spoke of the kindness and solicitude of his beloved friend, Mrs. Peter Cruger, originally Miss Church, for his Euphemia, with a gratitude that could hardly be expressed. He had another devoted friend, to whom his heart was bound by the strongest ties of reverence and affection,--the one to whom we have before alluded. One has long since passed away, the other but yet a little while was with us. They both loved and cherished the little girl for her uncle's sake, and she seemed to be daily fulfilling his fond wishes.

Page 61

She was carefully educated in the forms of the Catholic Church, and no lesson of love, charity, or kindness was forgotten, that might soften and penetrate her youthful heart. What delight to Toussaint to return to his happy home after the fatigues of the day, and meet this young creature of his affections, who enlivened him with her music, cheered him by her smiles, and interested him by relating all her little pursuits since they had separated! Perhaps she would repeat to him some story she had read during his absence, and she would say, "It is a true story, I read it in a book."

Her exercises in writing were very regular; every week two little notes in French and English were handed to Toussaint from his niece. We have many of them before us; we insert a few, which are about equal to those of white children at her age.

"New York, February 23, 1827.

"DEAR UNCLE:--

"O, how sorry I am that you was not there to see Miss Metz married; she looked so sweet and beautiful; she looked like an

Page 62

angel; but what I think was so good in her, that she should come and kiss my aunt and me, before all the company. I believe nobody would do it but her. It will come quite difficult to me to call her Mrs. Moulton. I have made one mistake already.

"Adieu, dear uncle.

"EUPHEMIA TOUSSAINT."

"DEAR UNCLE:--

"What bad weather we have now! I hope it will not last long, for it is very disagreeable for you, who have to run all over the town, and everywhere; but God knows better than we do; he does every thing for the best, and it is so singular that we cannot be contented. Dear uncle, I will be very much obliged to you if you will give me one shilling to buy cotton to finish my frock; now I have begun it I want to finish it very much, and after that I want to embroider a vandyke. I have not seen Mrs. Cruger a long time; I wish to see her very much.

"Adieu, dear uncle.

"EUPHEMIA TOUSSAINT."

Page 63

"DEAR UNCLE:--

"O, I must write to Mrs. Moulton to tell her about your having your miniature taken;

* * The miniature alluded to is the one from which the lithograph has been taken.

I have several things to tell her that will please her very much. Dear uncle will you excuse me for writing so short a letter this week, for I composed it in a great hurry. I know that it will please her, and make her laugh.

"Your EUPHEMIA TOUSSAINT."

The little girl's attachment to this kind friend, Mrs. Moulton, was unceasing through her short life. She often complained of the difficulty of calling her by her married name, and said, the other was much more natural.

It is with grief we see dark clouds gathering over this smiling prospect. The health of Euphemia began to decline, and she was threatened with consumptive complaints. Juliette mentioned her fears to her uncle; he could not believe it, he could not listen to it. But alas! it soon became too evident that the

Page 64

disorder of the mother had sown its hereditary seeds. Then there was no rest for poor Toussaint night or day. He required the unremitting consolations of his friends to soothe and calm his mind. He hung over the darling of his affections with an intensity of feeling which seemed to threaten his own life.

The good Father Powers devoted himself to uncle and niece. It was judged best not to acquaint Euphemia with her situation. It was her delight to rest in her uncle's arms, to tell him how she loved him, and what she would do for him when she got well.

Sometimes when friends called, they would find him seated on her bed, where she lay supported by pillows, her presents strewed around her, for people were untiring in sending her little gifts to interest and amuse her. Her uncle would hand her the articles that lay beyond her reach, and amuse her by recounting her treasures. So many more good things were sent her than she could even taste, that she said playfully, "I make uncle eat all these up, but I keep the flowers to look at."

Page 65

Toussaint felt deeply the proofs of friendship which were daily accumulated in attentions to his darling, and often expressed his unworthiness in the humblest manner, saying, "I thank God for all his goodness."

It was a great consolation to him that Euphemia suffered but little. She gradually wasted away, without any painful struggles. He said one day, "God is good; we know that here on earth, but my Euphemia will know it first there," pointing upwards.

A few months brought the rapid decline to a close; and the loved one who had been so carefully cherished and guarded, and whose slumbers had been watched over from infancy, slept the last sleep of death.

"And what is early death, but sleep

O'er which the angels vigils keep;

Around the white-robed seraphs stand,

To bear the young to the spirit-land."

For a long while Toussaint could only say to those who came to comfort him, "My poor Euphemia is gone"; and as his lips uttered these words, he covered his face with

Page 66

his hands. He grew thin, avoided society, and refused to be comforted. But his mind was too pious and too rational to indulge long this excess of sorrow. He listened to high and holy consolations, and found resignation in the prayers of his Church. Those who witnessed his struggles to command himself at this time, and perform his daily duties, have spoken of him with reverence.

Toussaint received a most consolatory letter from his friend, Mrs. Cruger, who was then in France, soon after the death of his niece. We give the following translation:--

"1829.

"I need not say, my dear Toussaint, how much I sympathize with you; my heart and my soul follow you in your last cares for this cherished child, to whom you have ever been the best, the most tender of fathers. My tears have flowed with yours; but I could not weep for her, I wept for you. When we resign to the Eternal Father a child as pure as the heaven to which she returns, we ought not to weep that an angel has entered into a

Page 67

state of happiness which our feeble conceptions cannot picture, and you, my good Toussaint, who are piety itself, will realize this consoling thought, the only one you can now welcome in this severe affliction. The life of Euphemia has been almost a miracle; she owes her existence to your constant care and watchfulness. Her short life has been full of happiness; she has never known the loss of a mother; far happier than hundreds of others raised in the wealthiest and most elevated classes, the most gentle virtues and affections have surrounded her from her cradle, and she has been taken from a paradise on earth to enter into an eternity of happiness. Could you have secured the future to her? If death had struck you instead of her, to what dangers might she not have been exposed! May the consciousness of the duty you have so faithfully discharged mitigate this bitter sorrow. You have given back to a cherished sister the child of your adoption, before either sin or sorrow had touched her, and they will both wait for you in that mansion

Page 68

reserved for beings as excellent and virtuous as you are."

The effect of Euphemia's death, and the deep affliction it caused Toussaint, seemed eventually to produce a more energetic purpose of usefulness; his earnest desire was to benefit others. To accomplish this object, when funds were wanting, he would use his influence in promoting fairs, and, in individual cases, raffles; disposing of elegant and superfluous articles at a just price, when their owners were reduced by poverty.

His ingenuity in contriving means of assistance to others was remarkable. A French lady, who was much embarrassed in her circumstances by the depreciation of her small property and the failure of her rents, consulted Toussaint on the possibility of doing something for her support. He suggested her teaching French. She said very frankly, that she was inadequate to it, that she had no grammatical knowledge. "Madam," said he, "I am no judge, but I have frequently heard it said that you speak remarkably pure

Page 69

and correct French." This was really the case, for she had been educated in the best society. "That is a very different thing," she replied, "from teaching a language."

Toussaint, after some moments of reflection, said, "Should you be willing to give lessons for conversing in French?" She replied that she should be quite willing.

He at once set about procuring scholars among his English friends, many of whom appreciated the advantage of free and familiar, and at the same time correct conversation, for their children; and thus pupils were not wanting for the lady, and she was able to support her family by these simple means till the sudden rise of her rents relieved her from her embarrassment. This method was quite an original idea of Toussaint's at that time, though it has since been adopted even in our own language.

On occasion of some fair for a charitable purpose, Toussaint would go round to his rich friends and represent the object, and they placed so much confidence in his judgment,

Page 70

that they would often add trifles to swell the list, and always take a number of tickets; and in this way he was able to collect considerable sums for the benefit of the orphan and the widow.

It must not be supposed that Toussaint's charity consisted merely in bestowing money; he felt the moral greatness of doing good, of giving counsel to the weak and courage to the timid, of reclaiming the vicious, and, above all, of comforting the sick and the sorrowful. One of his friends said that "his pity for the suffering seemed to partake of the character of the Saviour's tenderness at the tomb of Lazarus." When he visited his friends in sorrow, his words were few; he felt too deeply to express by language his sympathy. Once he said, "I have been to see poor Madam C--." (She had met with a most heavy bereavement.) "And what did you say to her?" said a friend. "Nothing," he replied, "I could only take her hand and weep with her, and then I went away; there was nothing to be said." He felt that, in the

Page 71

first moment of stunning grief, God alone could speak to her.

When he entered the house of mourning, an air of sympathy pervaded his whole manner, the few words he uttered were those of faith and love, and he was often successful in communicating comfort to the sorrowful.

We must not omit his wonderful capacity in sickness; how often he smoothed the pillow and administered relief to disease. He was constantly summoned as a watcher, and gave his services to the poor without money or price. At a time when the yellow fever prevailed, and the alarm was so great that many were deserted, Toussaint discovered that a man was left wholly alone. He was a stranger, but he took him to his house, nursed him, watched over him, and restored him to health. This stranger was a white man!

Like others, he sometimes met with ingratitude for his services; in one particular instance he persevered through difficulties and discouragements in endeavoring to serve a French family, and succeeded in procuring

Page 72

situations for two of the young men; but as they grew successful, they rather avoided their benefactor. "I am glad," said Toussaint, "they so well off; they want nothing more of me."

Because Pierre Toussaint was an unlettered man, many people who were surprised at his character, and at his numberless good deeds, attributed his excellence wholly to his natural disposition. They said, "He has the best