From Captivity to Fame or

The Life of

George Washington Carver:

Electronic Edition.

Merritt, Raleigh H. (Raleigh Howard)

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Lee Ann Morawski

Text encoded by

Lee Ann Morawski and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2000

ca. 360K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) From Captivity to Fame or The Life of George Washington Carver

(spine) From Captivity to Fame

Merritt, Raleigh H.

196 p., ill.

27 Beach Street BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

MEADOR PUBLISHING COMPANY

1929

Call number S417.C3 M4 (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the

American South.

The text has been

encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar,

punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved.

All footnotes are

inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as

--

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad)

and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Carver, George Washington, 1864?-1943.

- African American agriculturists -- Biography.

- African American educators -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Biography.

- Agriculturists -- United States -- Biography.

- Agriculture.

- Cookery, American.

- Tuskegee Institute.

- George Washington Carver Agricultural Experiment Station.

Revision History:

- 2001-01-09,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-09-08,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-09-05,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-07-31,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

FROM CAPTIVITY TO FAME

OR THE LIFE OF

GEORGE

WASHINGTON CARVER

BY

RALEIGH H. MERRITT

MEADOR PUBLISHING COMPANY

27 Beach Street

BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS

Page verso

COPYRIGHT, 1929 BY RALEIGH H. MERRITT

Raleigh Howard Merritt, was given permission

to compile and write this book, of which I

am the subject.

Signed George Washington Carver.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

THE MEADOR PRESS, BOSTON, U. S. A.

Page 5

DEDICATION

To those who have worked so willingly to bring about good will and a better understanding between the races, through co-operation in promoting industry and thrift, this book is dedicated.

R. H. M.

Page 7

PREFACE

The purpose of this book is to record the eminent achievements of a great agricultural chemist, Dr. George Washington Carver, of the Tuskegee Institute; to make known his interesting childhood and youth, his early struggles and later triumphs; and also to accompany him into the great creative stretch of thirty-three years at the Tuskegee Institute, during which time he has accomplished so much for the betterment of mankind.

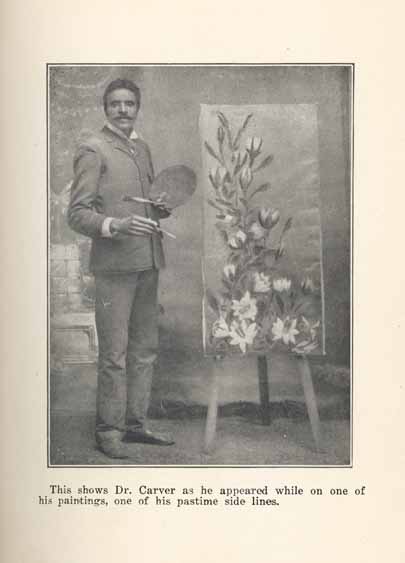

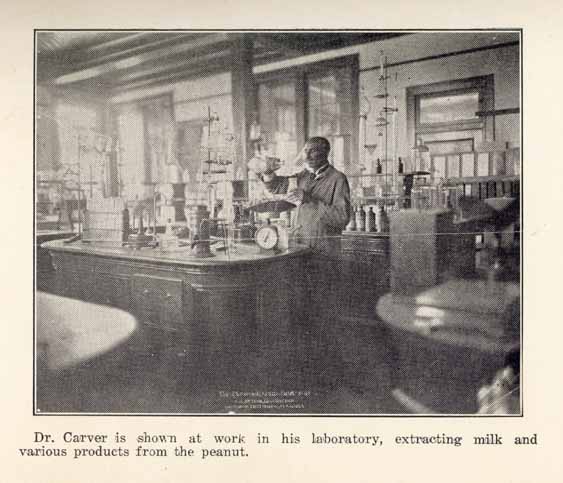

This book shows him deeply plunged into work for which he has always had an indubitable capacity; it reveals the exercise of his unsurpassed ability, his keen reasoning powers, and his 'uncommon' common sense. He is shown at work in his laboratory, reaching out into all regions of science and nature. He is also shown painting flowers, one of his pasttime hobbies.

Finally, he has emerged triumphantly from countless difficulties, bringing with him hundreds of by-products from the peanut, the sweet potato, the pecan; and also paints, stains and dyes from common clays of the South--the fruits of victorious struggles.

The supplementary section of this book is composed of bulletins on food and food subjects etc., issued by Dr. Carver. I should think that a few of them will be of especial value to the house-wife, and also the farmer.

While studying agriculture at Tuskegee, I was brought into somewhat intimate relations with Dr. Carver, and began an acquaintance which has continued to grow. Like all students who come in contact with him, I learned to regard him not only as a kindly and good-natured teacher, but also as one who radiated fatherly love. It occurred to me that some day I should like to put something in book form about his life and his marvelous accomplishments.

I make no attempt, however, to give a complete account

Page 8

of Dr. Carver's life and works. I should think this would not be possible. Only certain incidents can be detailed with accuracy.

Conscious of my limitations as a biographer, I have desired only to make this volume a fair sketch of a remarkable and extraordinary man.

Dr. Carver prefers not to be made the subject of any biography. He has felt, however, that if it is to be written, it is best done by a friend who has known him for several years, and whose judgment and discretion he can trust, and one who, because of his knowledge of the facts, will not misrepresent him.

I wish to express my appreciation and thanks to Professor A. Mack Falkenstein, of the Drexel Institute, for suggestions and assistance he has so willingly given me in the preparation of this volume; and also Mr. Orrin C. Evans, Feature Editor, of the Philadelphia Tribune. I am also most grateful to Mr. R. C. Atkins, Director of the Agricultural Department, of the Tuskegee Institute for several pictures which he so kindly placed at my disposal for this book. I am especially grateful to Dr. Carver, for portraits of himself and other pictures which he allowed me to use, and also for much material he placed at my disposal. I am thankful to Mr. Julius Flood, of Tuskegee Institute, for pictures and other material which he was so generous to send me; I am also deeply appreciative to Miss Abigail Richardson for one cut of Dr. Carver.

I am very grateful to the following for material which was reproduced in this book: J. L. Nichols & Company; the Black Dispatch; The Tuskegee Messenger, by courtesy of Mr. Albon L. Hosley; The Highland Echo, by Mr. Robert T. Dance, of Maryville College, Tenn.

I am very grateful, indeed, to everyone who so generously responded to my request in submitting statements of views and comments on Dr. Carver's Life and Works. It would take up too much space to mention each one by name.

RALEIGH HOWARD MERRITT,

December 31, 1928.Philadelphia, Pa.

Page 9

CONTENTS

- I. Birth and Early Childhood . . . . . 13

- II. Early Schooling and Struggles . . . . .18

- III. Working His Way Through College . . . . .23

- IV. First Twelve Years at Tuskegee . . . . . 27

- V. Discovers Possibilities of Native Products . . . . . 33

- VI. The Tuskegee Farmers' Conference . . . . . 41

- VII. His Creative Ability . . . . .47

- VIII. The Carver School Farm Club . . . . .51

- IX. Still Achieving and Helping People . . . . .54

- X. Views and Comments . . . . .63

- XI. 105 Different Ways to Prepare the Peanut for the Table . . . . .79

- XII. The Sweet Potato and Various Ways to Prepare It . . . . .113

- XIII. How to Make and Save Money on the Farm . . . . .127

- XIV. How to Raise Pigs with Little Money . . . . .145

- XV. Poultry Raising . . . . .147

- XVI. The Tomato . . . . .157

- XVII. The Cow Pea . . . . .162

- XVIII. Three Delicious Meals Every Day . . . . .169

- XIX. 43 Ways to Save the Wild Plum Crop . . . . .173

- XX. Alfalfa . . . . .186

- XXI. The Pickling and Curing of Meat in Hot Weather . . . . .190

SUPPLEMENT

Page 11

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- George Washington Carver . . . . . Frontispiece

- The Creamery at Tuskegee . . . . .22

- Dr. Carver Painting . . . . .26

- Dr. Carver at Work in His Laboratory . . . . .28

- Another View of the Laboratory . . . . .30

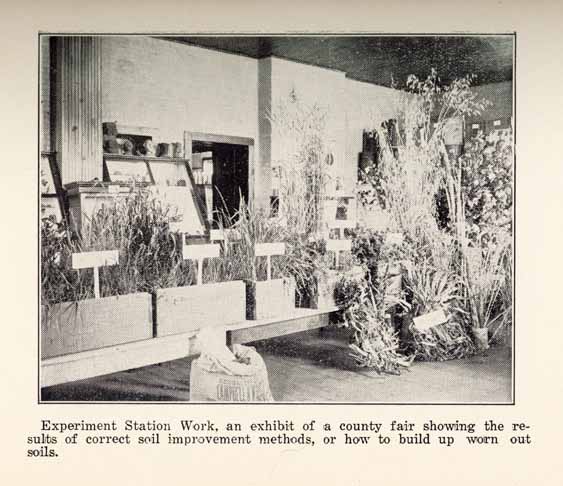

- Experiment Station Work--Results of Soil Improvement . . . . .32

- Exhibit of Milk and Cream Made from Peanuts . . . . .34

- Sketch of Tuskegee Institute Farm . . . . .38

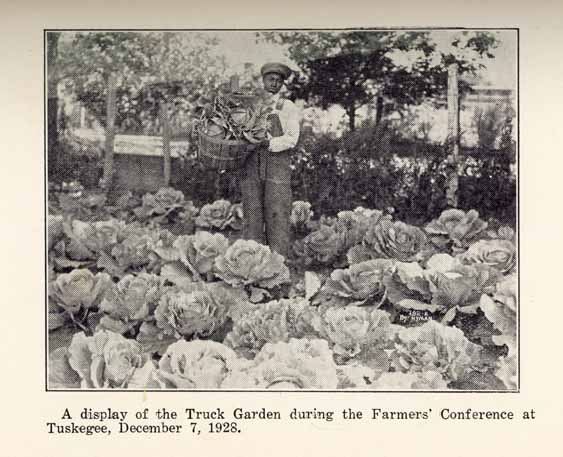

- The Institute Truck Garden Exhibit . . . . .40

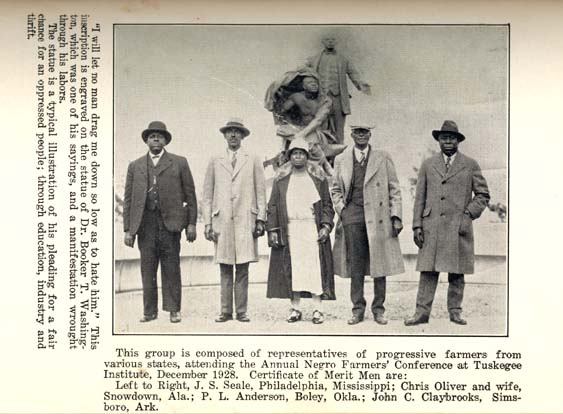

- A Group of Representative Progressive Farmers . . . . .42

- Members of the Carver School Farm Club . . . . .50

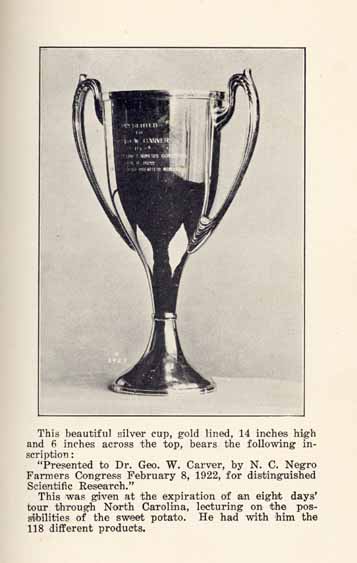

- Silver Cup Presented Dr. Carver by North Carolina Negro Farmers Congress . . . . .54

- Tuskegee Institute Swineherd . . . . .146

Page 13

From Captivity to Fame

CHAPTER I.

BIRTH AND EARLY CHILDHOOD

The romantic rise of George W. Carver, is a marvelous occurrence in the history of great Americans. He was born in a crudely constructed log cabin on the farm of one Moses Carver, (a German) near Diamond Grove, Missouri, during the dark days of emancipation in 1864. Out of poverty and obscurity this little boy was destined to become an outstanding representative of his race; an apostle of good will between the races; a creative genius, and one of the greatest scientists the world has ever known.

The reader will not be burdened with remarks regarding the research of George Carver's ancestry. He knew nothing about his ancestors himself, except what little he heard of his parents. He only knew that they were slaves, and that Moses Carver was the owner of his mother, and a neighboring slave-holder was the owner of his father.

KIDNAPPED.

Probably the first and most spectacular occurrence in the life of this little boy was, when he and his mother were kidnapped by a gang of night-riders, and carried into Kansas. Although he does not remember anything about this, as he was only a baby about six weeks old.

Mr. Carver, his former master, sent out a rescuing party, which recovered him in exchange for a race horse valued at $300 part of the kidnapping force had gone ahead and carried the little boy's mother away. He never knew what became of her. He heard that his father was killed accidentally by an ox team while hauling wood. This is all he ever knew about his parents.

There were faint hopes of raising the babe of six weeks old,

Page 14

because he was very sickly, and had a severe whooping cough. Notwithstanding this, Mr. and Mrs. Carver adopted him into their family where he remained until he was about ten years old.

This little boy got his name in a very unusual way. He was not so fortunate as to inherit a name, but because of his faithful devotion to his work, and also his habitual truthfulness about everything, the Carvers called him George Washington. He got the name Carver from the Carver family. He speaks of Mr. Carver as being a very humane man.

George began to seek knowledge at an early age. During the day he spent almost all of his time roving the woods, and acquainting himself with every queer flower and every peculiar weed. He was also interested in studying the rocks, and different stones, and the birds. He usually played by himself as his playmates were very few.

As the manifestation of his love for the plants grew daily, the boy began to ask questions; "God, why did you make this plant, and for what purpose did you make it?" He felt that it was his duty to find out the use of these plants, which the great Creator placed here for man.

Moving pictures or 'movies' were unknown to George. But he got his share of amusement in listening to the birds sing. In fact, this was a great source of inspiration and encouragement to him. It was his highest ambition to finish his work as quickly as possible each day, so that he could get out into the woods among the things he loved best. Unconsciously he would find himself trying to tone his voice like that of the birds, either by whistling or singing.

One finds in him today countless echoes of the voices that spoke to him amidst the woods and hills of Missouri, during his boyhood days, the foundations of his character date from his earliest childhood. While he seemed just an average boy, yet he showed an unusual interest in the vital things of life.

He was frail and weak, therefore, he couldn't do very heavy work. But he usually made himself useful around the house by getting wood and bringing in chips and seeing to it that the fires were kept going. Occasionally he went to the spring for a pail of water, this being the chief source of water supply

Page 15

for the house, as was common in those days. There was nothing more thrilling and inspiring to George, than listening to the chirping of the birds, the humming of the bees, and the rhythmic echoes of the brooks and rills which seemed to have been repeating the sounding joy of Nature's blessings on a bright and sunny spring day, as he climbed the hills on his homeward journey.

It was during those days that the qualities which are essential to surmount obstacles, were unconsciously woven into the fiber of his character. These characteristics have followed him through life.

Among the things George did around the place was to assist Mrs. Carver prepare meals for the family. He soon learned to be a first class cook. He even learned to sew and mend clothes. After each meal George made himself useful by washing the dishes and getting the kitchen and dining room in order. After finishing his work he would hasten to the woods to play. He busied himself in the woods, gathering bunches of flowers, and sometimes he would fill his pockets with rocks, and sometimes with bugs. He formed such a habit of this that Mrs. Carver used to force him to turn out his pockets before she would allow him to come in the house.

An incident occurred one day which George has never forgotten. Mr. Carver usually went to town twice each year, and George usually went with him on every other trip. The time came for Mr. Carver to go to town, and it happened not to be George's time to accompany him, so he had to remain at home and see that all the livestock were properly cared for and fed that night. It occurred to George, however, that this was the time to play. He seemed to have enjoyed himself as never before. His enjoyment was so great, apparently, that he couldn't concentrate on his duties, so he forgot to feed the stock before night came. After nightfall came, however, he recalled that he hadn't discharged his all-important duty.

Realizing that it was about time for Mr. Carver to return from town, George hastily rushed to accomplish his task and thereby avert a whipping which he knew was the next thing he would get if he had neglected to do his work. By this time it was too dark for him to see without a light. The first thing he thought of was to get the parlor lamp, light and use

Page 16

it, then put it back in its place before Mr. Carver came. But Mr. Carver returned before he had finished feeding the stock, and gave George a whipping for using that most "valuable lamp." The lamp is an old tin frame, round in shape, and has a socket or holder in which a candle was placed. The lamp gave a very dim light, but it didn't fail to furnish plenty of smoke. Such a lamp, however, was very rare and was considered something fine and out of the ordinary, in those days.

Dr. Carver has that old lamp today, and also an old spinning wheel which his mother used to spin flax, during the days of slavery on the plantation. He also has several other collections which he got during his boyhood days.

When I asked Dr. Carver about the date of his birth he said, "I should like to know the exact date of my birth myself, but I do not. As a rule no records of children from slave parents were kept. I suffered from this same custom."

Young Carver used to study an old blue-back speller by the dim light of the burning logs in the fire place. It was in this way that he learned this little book by heart.

He was a boy of quiet temperment, and poor health, and remained very small until he was about twenty years old. He showed no signs of future eminence. But the manifestations of his mental qualities are traceable back to his early boyhood days. No longer than last fall, in an address at Tulsa, he said, "We must disabuse our people of the idea that there is a short cut to achievement. Life requires thorough preparation; veneer isn't worth anything." He lived, as he does now, close to the things which are eternally true. It was in this manner that he learned his greatest lessons--lessons which have followed him through life and enabled him to be the man he is today.

Carver has walked the one straight path from boyhood. He always made it his aim to build on solid logic and facts. He always made every action be directed to some definite object. He was a 'dreamer'--a 'dreamer' who makes dreams become actualities by perseverance and hard work.

At an early age he was religiously inclined. One finds in him today these same inclinations. To him there is no conflict between science and religion.

As George was constantly in poor health, Mr. and Mrs.

Page 17

Carver thought it would be the best thing for him to prepare himself for work which would not require a great deal of physical exertion. They were entirely willing for him to go wherever he could get an education. This was about all the encouragement he got.

He never had the opportunity of attending Sunday school, in fact, he had no schooling, either secular or religious, except that he had learned from the little blue-back speller.

Under all unfavorable circumstances, George never became discouraged. He had a vision and an insight into the need of doing something for human betterment--particularly his race, which needed help and guidance in overcoming a tremendous handicap.

Page 18

CHAPTER II.

EARLY SCHOOLING AND STRUGGLES.

It appears that George had a continuous desire of acquiring knowledge, even though no one encouraged him to enter school, after he had learned to master the blue-back speller by himself. From his limited source of information, however, he was not able to find answers to queries which were constantly pressing upon his mind. Therefore, he became displeased with present conditions.

During this time, he heard of a little school, which was about eight miles away. Finally, George decided to venture upon the journey to this school, although he was only ten years old. Mr. and Mrs[.] Carver had no objection to his leaving, as they wanted him to get an education, even though they gave him no financial assistance.

George set out on his journey to the little school at Neosho, a distance of eight miles of trudging over hills, through swamps and sandy bottoms; as the sun began fading behind the Western horizon he lost no time in trying to make his destination. As night drew near, he heard the whipporwill's cry, which was startling, and made him feel somewhat nervous as he became conscious of the responsibilities which he was assuming.

After arriving to Neosho, young Carver was confronted with countless obstacles and difficulties. In the first place, he was absolutely without financial means, he didn't have so much as a single penny; and in the second place, he didn't know anyone there, therefore, he had no place where he could spend the night.

George spent the first few nights in an old horse barn. After looking around for a short while he succeeded in getting odd jobs here and there for a make-shift livelihood. During the meanwhile he continued to make his stopping place in the old barn. Notwithstanding all of this hardship the boy entered school and continued to stick there.

Page 19

Finally, he made friends with a Mr. and Mrs. Watkins, who adopted him into their family. They allowed him to attend school for what he could do in their home. He said, "Indeed, Mr. and Mrs. Watkins treated me as if I were a member of their family."

The school was taught by one teacher who was very poorly prepared. The school building was an old log cabin, poorly ventilated, and afforded but little protection from the wrath of the weather. The benches were so very high until the pupils' feet wouldn't reach the floor when sitting on them, and besides this, they (the benches) didn't have any backs on which the pupils could rest. School apparatus were unknown there, in fact, every inconvenience that imagination can paint existed.

It was here at this little crudely constructed school, however, that young Carver's ambition was kindled as never before. It was the latent qualities of the boy which were responsive, under the slightest favorable environment. Within a year he had mastered what this school had to offer.

ON TO FORT SCOTT.

After completing the course which he had been studying during the past year, George was anxious to go wherever he could enter school. While wandering along the road, a mule team came along en route to Fort Scott, Kansas. Young Carver asked the people to let him go along with them, and they kindly allowed him to go. As it took several days to make the journey he was almost completely worn out when the team arrived at its destination.

Immediately after arriving to Fort Scott, George began to search for work. It was not very long before he had succeeded in getting a job as kitchen man and dishwasher. In fact, he did all kinds of house work, from cleaning rugs to cooking and house cleaning. The previous training he had gotten while with the Carvers made him efficient to master this new situation.

ENTERS SCHOOL

While in Fort Scott, for a short time, young Carver entered

Page 20

school, although he continued to stick to his work. His stay in Fort Scott was marked with a continuous upward climb through difficulties and obstacles, attending school whenever possible, and in the meanwhile doing some kind of work to make ends meet.

There were no signs that he would merit high honors or future greatness. Obviously, we find qualities of self control, serious attention and concentration to his duties, and that which was eternally essential.

For months at the time, George was not able to buy a one cent postage stamp. Notwithstanding this fact, he never charged very much for his work he made a rule of charging a reasonable price for whatever he did for the people. It mattered not how badly he was in need, he never would accept any financial assistance from anyone. He never desired to make himself an object of pity, he only asked for a square deal in every particular.

After being in Fort Scott about seven years George returned to his old home place, to visit Mr. and Mrs. Carver. Being unusually small for his age he was able to go on half fare; the train conductor hesitated, however, to take him, because he thought that the boy was too small to make the trip alone. He made the trip, however, without any difficulty.

Mr. and Mrs. Carver were very glad to see George, as they had not seen him for several years. It took several days for him to tell them about his journey in Kansas. He told them how he had been struggling to keep in school, and also about his plans to go through college. They seemed to have been interested in everything he had to tell them.

George spent the entire summer with the Carvers. When he returned to Kansas he took with him the old polar lamp, and also an old spinning wheel which his mother used in spinning flax, on the plantation, during the days of slavery. He has both the spinning wheel and the old lamp now, which he values very highly.

After returning to Fort Scott, he set out to get things working. He opened a small laundry. As he knew the art of the business he succeeded in catering to the people in the neighborhood. He always did very fine work, and at reasonable

Page 21

rates. He gained the good will of the people in the community.

George grew with great rapidity during the period of two years. When he was about nineteen years old he was very frail and small, but by the time he was twenty-one he was about six feet tall.

After completing the high school course in Fort Scott, he began to make plans to enter college. He heard of an educational institution in Iowa. After communicating with the school he filed an application and sent it by mail. His application was accepted, he set out for the school soon afterward. After he arrived on the scene, however, the president of the school refused to admit him, because he was a Negro. The boy had spent nearly all the money he had for car fare in getting there.

After being refused admittance to this school, he soon found himself without enough money to get out of the town. He began to seek for a job at once. Finally be succeeded in getting a few carpets to clean, soon afterward, however, he got a job as cook, and he continued at this until he had earned enough money to open a laundry. It was not long before his little business was patronized by students from the school, and also people in the immediate community. He remained there, however, until the following spring. Then he went to Winterset, Iowa, where he served as a first class cook in a large hotel.

After being there for some time he attended a church, (for white people) one evening. He took a seat in the rear of the building, but when the choir and congregation sang, he found himself taking an active part in singing. He evidently had a beautiful voice, because the soprano soloist of the choir, Mrs. Millholland was very favorably attracted by his voice. Mr. Millholland came to the hotel the next evening and inquired for George, and he invited young Carver to his home to sing for Mrs. Millholland and himself.

After arriving at Mr. and Mrs. Millholland's home George sang while Mrs. Millholland played. She was kind enough to have George come up once each week for vocal instruction.

Mr. and Mrs. Millholland became staunch friends of George. He used to tell them about the many things he had

Page 22

to do during the day, and also about his plans to continue his schooling. They always listened to him with great interest, and encouraged him to go on with his education. They also encouraged him to cultivate his artistic ability. He could paint very well. It is said that one of his paintings at the World Fair at Chicago, was valued at four thousand dollars.

Not long afterwards he made his way to Simpson College, at Indianola, Iowa, where he registered for the regular course, and took music, on the side, and also did some work in art.

When he had paid his entrance fee he had exactly ten cents left. With this small amount he invested it into five cents worth of corn meal and five cents worth of suet, and he lived an entire week on this menu.

Providently, a way was opened by the time his small supply of foods had exhausted. It was not long, however, before another turning point took place. His instructor was profoundly impressed with his talents and his ability. But he frankly told George that there was not much that he could hope for there, in the way of developing his talents.

Young Carver left Simpson College, and made another effort to accumulate something so that he could enter the Iowa State College, at Ames.

I have a letter from Dr. John L. Hillman, President of Simpson College, relative to Dr. Carver's record when he was a student there. Dr. Hillman says: "He was a student at Simpson College for three years. He took his degree in Agriculture at State College at Ames, and gave such promise that he was retained for some time on the faculty there until he was called to Tuskegee Institute.

"When I consider the difficulty with which he had to contend, I am simply amazed at what he has accomplished. His spirit and character are even more wonderful than his accomplishments.

"Our College conferred upon him the honorary degree of Doctor of Science last commencement, June 1928."

This picture shows two students engaged at work in the creamery. This creamery has modern equipment, and the management employs a large force of students, who get practical experience by working, and at the same time earn something to defray expenses while in school.

Tuskegee and the entire community are served with milk from this creamery

every morning, just as people are served in large cities.

Page 23

CHAPTER III.

WORKING HIS WAY THROUGH COLLEGE

By working hard and economizing closely young Carver saved a small sum of money, with which he entered Iowa State College, at Ames, in 1890, where he began the study of agricultural chemistry. Indeed, life at college with him was very much like that of his early boyhood days, in that it was marked with constant struggles in making ends meet. That is, he had to do something for a livelihood while attending school.

After getting to College and qualifying to enter he was soon confronted with the question of finding lodging accommodation on the campus. This embarrassment, however, marked the beginning of a life time friendship between young Carver and Professor James Wilson, then Director of the Agricultural Experiment Station. After hearing about Carver being refused a place to stay, Professor Wilson said, "George may stay in my office." He proved to be a real friend to young Carver and did whatever he could to assist him.

Several years after the occurrence of this incident, when Carver had become Director of Agriculture at the Tuskegee Institute, his old friend, Professor Wilson, was visited to Tuskegee. To both this occasion was an exchange of reminiscence of the past days at the Iowa State College. At this time the former Professor of agriculture had arisen to the Secretaryship of the United States Department of Agriculture, a member of the President's Cabinet.

George did various odd jobs for a livelihood while in College. At times, however, he was without a penny, and for months he was not able to purchase a postage stamp. Notwithstanding this state of affairs he continued in college and applied himself to his studies. He always tried to do common things uncommonly well. He made it a rule to do his work so well that no one could come behind him and improve upon it.

Page 24

One should not imagine that young Carver's life at college was all serious. Obviously he was always on the alert for everything pertaining to the essentials of life. Yet he was as fond of playing as a fellow could possibly be under the circumstances.

Carver took an active part in the various college activities. It is interesting for one to note how he had grown from a sickly boy to be a young man with good health, which made him physically fit as well as intellectually. Spending a great deal of his time outdoors, close to nature, and also throwing himself into various activities are the prime factors which made his success possible. He was not an athlete in the least sense, yet he knew how to make the most of any occasion.

Another thing which was peculiar about Carver, was that he would never accept any financial assistance from anyone, it mattered not how serious conditions got with him. He knew that he should train himself to have self reliance, perseverance, courage and the knack of sticking to a thing to the finish.

Young Carver got a great deal of his education through observation, as well as from the text book. There was hardly anything that escaped his attention. He used to watch the ant and various insects, and made a very close study of them. It was from these insignificent insects that he learned great lessons--lessons which have enabled him to be a great servant for the people.

In applying himself while in college he sought to lay a brick in the foundation of his character each day, by making line upon line, precept upon precept, here a little and there a little, until he had become efficient for future service for human betterment. He followed his Star as was destined by his Great Creator.

While studying agriculture, Carver was placed in charge of the greenhouses. Here he made a close study of plant life, giving special attention to bacterial laboratory work in systematic botany. Young Carver's work was so satisfactory until he won the admiration of all of his teachers. He was often pointed out as a studious young man, with assidious and sterling qualities. Carver earned enough by working in the greenhouses to pay his current expenses.

Another method by which he earned spending 'change' while

Page 25

in college, was that of selling lye hominy. That is, he would take corn and boil it in clear water, adding a little lye, which made the corn soft and also made it so that the outer coat of the corn would peel off after getting to the boiling stage. After this corn had cooked thoroughly and peeled, it was removed and washed thoroughly in clear water. Then it was removed again and seasoned to taste, after which it was fried or prepared in other forms. Young Carver always found a great demand for his lye hominy among the students. The small sums of money realized from the sales of his hominy helped greatly in putting him through college. In another chapter several ways are given for preparing lye hominy.

During the scholastic year of 1893-4 Carver began to look forward to getting himself permanently located for work, as he was to be graduated at the coming commencement. This matter was not worrying him, however, as he had given such promise during the four years there, that it had been intimated to him that he would be retained on the faculty of the State College after graduating. He continued to make the most of his work at the greenhouses.

His artistic ability, which was cultivated to some extent while at Simpson College, was greatly cultivated by practical work and experience while he was in charge of the flowers at the greenhouses. He studied flowers so closely until he learned to paint any design and variety with such touch that one could not distinguish his flowers from real ones, unless they were very closely examined. In another chapter of this book he is shown painting flowers, one of his past-time side lines, during brief periods of a very busy life.

Carver graduated from State College in 1894, receiving his B. S. degree in agriculture. Some time before commencement he was assured that he would be given work, so he began planning to enter upon his new field of labor.

Young Carver continued to pursue an advance course in the science of agriculture, taking this along with the bacterial laboratory work in systematic botany. In 1896 he received M. S. degree in agriculture.

A few days ago I received a letter from the President of Iowa State College and he said "As a College we feel proud

Page 26

of Dr. Carver. Some of the teachers are still here who were here when he was a student."

Carver had never found any work more congenial and within keeping of his calling, than that he had been doing after graduation. He liked to teach because he was very much interested in the work.

His life has been an inspiration and an encouragement to both young and old people--in fact to most people who ever heard about him.

When Carver was going through college, evidently he resolved to apply the words of the great immortal emancipator, Lincoln, that " 'I'll prepare myself and when my time comes I'll be ready.' " Thus it came about in the year 1896, an opportunity for him to work for the betterment of his people in the South, where a man of his talent and ability was so badly needed.

This occurrence took place when Tuskegee's famous founder, the late Dr. Booker T. Washington, was sending out inquiries to various schools and colleges throughout the country for prepared young men and women. George W. Carver, was recommended to Dr. Washington as being a young man who was thoroughly educated in all matters pertaining to agriculture.

Dr. Washington wrote Carver, and asked him to come to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where he (Washington) was scheduled to deliver an address. Carver got ready and set out for Cedar Rapids, immediately. After arriving there it was not long before he met Dr. Washington, and had a conference with him. Carver agreed to go to Tuskegee and do whatever he could to advance the agricultural department of the Tuskegee Institute.

Even though he was very well satisfied with his work at the State College, he was desirous of going to Tuskegee because he thought that he could be of more service to his people. The young professor of agriculture was far-sighted enough to know that before him, at Tuskegee, lay a vast field of possibilities. Having these facts in mind, and a desire of working for the uplift of his people in the South, Carver began to prepare to leave for Tuskegee Institute.

This shows Dr. Carver as he appeared while on one of his paintings, one of his pastime side lines.

Page 27

CHAPTER IV.

FIRST TWELVE YEARS AT TUSKEGEE.

During the year of 1896, Professor Carver entered upon his work at the Tuskegee Institute. After being there for a short time he began to study conditions of the Agricultural Department; and also busied himself in making a general survey of the community. After ascertaining what needed to be done, he organized plans for the purpose of doing effective work.

When Professor Carver entered upon his work at Tuskegee the agricultural department was in its infancy. Funds had not been available to run it on large basis. The old agricultural building was not adequate to accommodate various purposes for which it was used. It was just about as crude in architectural construction as one should have expected, during the yearly years of the school, when it was facing one struggle after another for the lack of funds.

This state of affairs, however, offered no difficulties for Carver to entertain, in fact, he considered disadvantages as stepping stones to accomplish his task. He simply got on the job and made himself busy.

One of the first things he set out doing was that of getting the laboratory in workable condition. Indeed, this was not a small job, because nearly all the necessary equipment was lacking. Here an opportunity came for him to practice a lesson which he learned when a boy, that is, the lesson of carving something out of nothing. Moreover, the lesson of translating opportunity into achievement, and how to triumph over complex problems.

As the apparatus in the laboratory were not sufficient, he sent his students out to the alleys to gather old bottles, broken china, and bits of rubber and wire, out of which he made apparatus. Soon afterwards, however, his temporary fixtures were displaced, gradually, with new equipment.

Page 28

STUDYING AND MAKING USE OF THINGS AT HAND

Dr. Carver began to roam over the fields and the woods, in the community, with the purpose of making a study of different kinds of soils, and various plants etc. He usually took along his botany case to gather specimens which he carried back to make a study of in the laboratory.

The people in the community didn't know what to make of him when he was going through the fields and over the hills with his case, stopping here and there and gathering plants. All of this was strange to them. They thought, however, that he was a "root doctor." Several people came to him for treatment and for medicine.

Professor Carver has always aimed to make complete utilization of the native products, which grow so abundantly in the South. He emphasized the fact, that the farmer should study market conditions, as to supply and demand, co-operative marketing, and also a number of other things pertaining to this phase of the agricultural industry. He says that this is just as important as making a study of "building-up the soil" for greater production.

THE TUSKEGEE EXPERIMENT STATION

The Experiment Station is a plot which contains nineteen acres of land. Throughout the year experiments are made methodically to ascertain the qualities of various kinds of soils and their possibilities of producing crops under certain conditions and adaptations.

The soil is of a very poor quality, ranging from coarse sand to fine sandy loan, and clay loam. If crops are grown successfully there, (and they are) there certainly should not be any doubt about growing good crops in other sections of Alabama, or any parts of the South, where the soil is more fertile.

"Building up" this Experiment Station, and making experiments with rotations of crops has been one of the outstanding phases of Dr. Carver's work during the first twelve years of his work at Tuskegee.

In 1897, his report showed that, with the best methods and

Dr. Carver is shown at work in his laboratory,

extracting milk and various products from the peanut.

Page 29

abundant use of fertilizer, there was a net loss on the operation of $16.25. The next year, however, he worked the soil up to where the operation brought a net gain of $4.00. As he continued to improve the soil, the yield of the crops increased every year. In 1904, he produced eighty bushels of sweet potatoes per acre on a plot of ground, and also grew another crop on the same ground that year. The return was $75.00 per acre. In 1905 he raised a five-hundred-pound bale of cotton on this same soil.

FERTILIZERS--BUILDING UP SOIL

Dr. Carver says the results of twelve years' work on the Experiment Station plots, and in the laboratory prove that we are allowing to go to waste an almost unlimited supply of the very kind of fertilizer the majority of our soils are most deficient in. I mean muck from the swamps and leaves from the forest.

"Three acres of our Experiment Station has had no commercial fertilizers put upon it for twelve years, but the following compost: 2/3 leaves from the woods and muck from the swamp (muck is simply the rich earth from the swamp). 1/3 barnyard manure.

HOW TO MAKE THE COMPOST

"Two loads of leaves and muck are taken, and spread out in a pen. One load of barnyard manure is spread over this. The pen is filled in this way. It is either rounded over like a potato-hill, or a rough shed is put over it to turn the excess of water, so as to prevent the fertilizing constituents from washing out. It is allowed to stand this way until spring.

WHEN TO MAKE THE COMPOST

"Being your compost heap now; do not delay; let every spare moment be put in the woods raking up leaves or in the swamps pilling up muck. Haul, and put in these pens. Do not wait to get the barnyard manure--you can mix it in afterward, or if you cannot get the barnyard manure at all,

Page 30

the leaves and muck will pay you many times in the increase yield of crops.

HOW TO USE.

"Prepare the land deep and through. Throw out furrows with a middle-buster two-horse plow; put in the compost at the rate of 2 tons per acre, 2 1/2, where the land is very poor; plant right on top of this. Handle afterwards the same as if any other fertilizer had been used.

"Save all the wood ashes, waste lime, etc., and mix into this compost.

RESULTS.

"As stated above, three acres of our experimental farm has no commercial fertilizer put upon it for twelve years. The land has been continually cropped, but has increased in fertility every year, both physically, and chemically, on no other fertilizer than muck compost and the proper rotation of crops.

"This year 282 pounds of lint cotton, 45 bushels of corn, and 210 bushels of sweet potatoes were made per acre, with no other fertilizer than above compost.

"Try this; it will take only one or two trials to convince you that many thousands of dollars are being spent every year here in the South for fertilizers that profit the user very little, while Nature's choicest fertilizer is going to waste."

HELPING THE SOUTHERN FARMER.

Professor Carver's primary object has always been that of being the greatest assistance to the Southern Farmers; in helping them have better farms, and happier homes, with plenty of food raised on the farms, and also a surplus to sell. Thus that class of people could soon become property owners, tax payers and independent--a class of people that would be an asset to any state.

Thirty-nine different bulletins have been issued by Professor Carver, on food subjects, and scientific farming.

This picture shows Dr. Carver, actively engaged at work

in his laboratory,

which is one of the best equipped laboratories in

the country.

Page 31

Hundreds of these bulletins have been distributed throughout the South. As a result of this, his bulletins are used extensively in all sections of the country now. He told me that hardly a day passes that he does not get a letter asking for a number of them.

Professor Carver has made many tours through the Southern States, to make demonstrations of various by-products, and to explain their possibilities. He has been doing this, and distributing the bulletins with the sole purpose of answering questions and solving problems for the farmer. In fact, he has sought to give the farmer free information and be of the greatest assistance to him in every possible way.

"During1

(1 Booker T. Washington, Story Of My Life and Work, pg. 213, J. L. Nichols & Company, Naperville, Ill.)

the earlier years of the school we found it difficult to get students to take much interest in our farm work. They wanted to go into the mechanical trades instead.

"After the opening of the new agricultural building and the securing of Mr. Geo. W. Carver, a thoroughly educated man in all matters pertaining to agriculture, the Agricultural Department has been put upon such high plane that the students no longer look upon agriculture as a drudgery, and many of our best students are anxious to enter the Agricultural Department.

"We have demands from all parts of the South for men who have finished our courses in agriculture, dairying, etc., in fact, the demands are far greater than we can supply.

FIRST TWELVE YEARS AT TUSKEGEE.

Any process that does not get the best possible results is wasteful to the degree that it falls short of perfection. Fertilizer could not be used with slave labor, as its use required care and judgment, and even whipping did not instill this common sense of reason into slaves. Therefore, under slave conditions land could be used for only a few crops, then it must be left to grow up in weeds and grass. This system of agriculture was very wasteful.

"In view of this situation it is safe to affirm that under such a system of agriculture the available cotton land would some

Page 32

time or other come to an end. What then? Would the South find new occupation for the slaves? There was no chance of this."

Tuskegee Institute has been a great factor in solving this problem. The primary object of its founder was not only for the betterment of his people, but for the uplifting of the entire South.

Not less interest has been manifested by Dr. Carver in this most worthy cause.

Experiment Station Work, an exhibit of a county fair

showing the results of correct soil improvement methods, or how to

build up worn out soils.

Page 33

CHAPTER V.

DISCOVERS POSSIBILITIES OF NATIVE PRODUCTS.

Prior to the coming of the boll wevil, cotton was considered as being the chief money crop of the South. Even the smaller farmer depended on his cotton crop, from which he expected to realize some cash money in the fall. But as soon as the boll weevil began invading the cotton regions of the South, and almost completely destroying promising crops of cotton, (estimated to be worth thousands of dollars) the farmer was placed in an intricate position. That is, he was faced with the problems of destroying the weevil, if possible, or that of substituting a native crop, for which he could find a demand in the markets throughout the year.

To discover such a product as this simply meant that a great deal of investigation and research work had to be carried on. During this time Dr. Carver was constantly working on the common peanut, to see what possibilities were tied up in it. He had already extracted a variety of products from it.

In fact, Dr. Carver had already found that the peanut contained prime qualities of importance in a balanced diet, and essential for the proper nutrition of man and other animals.

To date he has extracted 202 different products from the peanut, yet he says that its possibilities are not exhausted by any means.

In another chapter 105 different ways are given to prepare the peanut for the table, according to Dr. Carver's recipes. This is from a household point of view, however, and has no bearing on the 202 different products which he extracted from the peanut.

A PARTIAL LIST OF THE 202 PRODUCTS FROM THE

PEANUT

Salted peanuts, mixed pickles, soap and soap-sticks, face powder, face bleach, washing powder, milk, as good as or

Page 34

better than cow's milk, several kinds of wood stains and dyes, an assortment of cheese, chocolate bars, instant coffee, breakfast food, caramels, butter, flour, meal, lard, axle grease, stock food, brittle, Scotch butter, wafers, kisses, bisque, sprouts, relishes, cheese filler, slave, tan remover, shampoo lotion and printer's ink.

MAKING USE OF THE PEANUT

The peanut has been used extensively throughout the South, particularly so during the World War. As the people become more acquainted with its various uses the demand will probably exceed all previous records. Thus, the farmer can figure on a fair price for his crop. This will mean a great step in forwarding the agricultural industry of the South.

During the fall of 1917, it was interesting for one to have seen farmers coming to Tuskegee with wagons loaded with peanuts; nearly every farmer who lived in the adjacent districts to Tuskegee was growing peanuts. They found a ready market for their product at the Tuskegee Institute, even though several acres of peanuts were grown on the farms of the School. Oils and a variety of other articles were extracted from these peanuts under the direction of Professor Carver.

I recall an incident which occurred during this unusual period of the "rising tide" of the lowly "goober." It happened in connection with a car load of peanuts which was shipped to Tuskegee. Somehow the door of the car had been ripped open, and several bushels of peanuts poured out on the ground. Soon afterwards, however, it occurred that a force of officers were detailed from the Commandant's office, only to discover bags of peanuts in the boys' rooms. Meanwhile, however, Professor Carver was still bent on carving upwards of 176 different by-products from the peanuts which had not been devoured.

THE SWEET POTATO.

It appears that the sweet potato comes second on Professor Carver's list. He has extracted a variety of 178 different

Yes, this is milk and cream, and it is as good or

better than cow's milk.

This is the result of one of Dr. Carver's

extractions from the common peanut.

Page 35

articles from this common product. The sweet potato is universally recognized as an important product, its possibilities, however, are too little known.

Throughout the South the sweet potato is grown more or less on large scales. Professor Carver has worked day after day, and sometimes at night, to unravel mysteries which this common product contains. In view of the fact, that sweet potatoes are very easily grown, and require but little outlay in cash to put on the market, its possibilities as a commercial product is not to be questioned.

"A theory is a theory because it lacks facts," Professor Carver, avers. To utilize the common things at hand has always been his aim. In his work he has always sought to produce something which would be of practical use to the people.

SWEET POTATO BREAD

Sweet potato bread is made for the students and teachers at Tuskegee, from Professor Carver's recipes. I had the opportunity of trying that bread for some time, and I found it to be the best I have ever eaten. Everybody says this about the sweet potato bread. It has become famous for its pleasing taste; it's somewhat spungy, soft and just a trifle sweet. Anyone desiring to try Professor Carver's recipes for making this bread may see chapter on Sweet Potatoes. How to make sweet potato flour, starch, sugar bread and mock cocoanut are also listed.

A PARTIAL LIST OF BY-PRODUCTS FROM THE

SWEET POTATO.

The following is a partial list of the 178 different by-products which Dr. Carver extracts from the common sweet potato: Flour, meal, starch, library paste, mock cocoanut, breakfast foods, preserved ginger, vinegar, ink, shoe blacking, coffee, chocolate compound, bisque powder, dyes, candies, rubber compound, stock food, molasses, wood fillers, carmels etc.

Page 36

MISCELLANEOUS PRODUCTS

Dr. Carver has extracted paints, stains and dyes from common clays of Alabama and Georgia. He has also gotten stains and dyes from scuppernongs.

The pecan has also yielded a number of different products. Anyone desiring information about these products may write to the Research and Experiment Station, Tuskegee Institute, Alabama.

IMPORTANCE OF THE AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY

Dr. Carver has always emphasized the importance of the great agricultural industry, from which the food supply of the Nation comes; he has spared no efforts in trying to help educate the people to appreciate this fact.

Probably one of the greatest problems which is now before the United States Congress is the "farm relief bills." This, at least, is evident of the fact that agriculture as a profession and as a science has received the attention which it merits, as the greatest and most important industry of the country.

"Burn down the cities and leave the farms and the cities will spring up again as if by magic; but destroy the farms and leave the cities and grass will grow in the streets of every city in this country," said William Jennings Bryan.

REFUSES TO COMMERCIALIZE.

One of the most outstanding peculiarities of Dr. Carver is, that he refuses to commercialize on his work. One need not think that Dr. Carver is doing this for a name. In fact, he has a habit of depreciating himself, and that of underestimating the regard in which others hold him. He has never sought for popularity, even though he has merited international fame by his marvelous achievements for mankind.

THE BOOKER T. WASHINGTON SCHOOL ON WHEELS

"The Booker T. Washington School on Wheels" is composed of a group of teachers (four or five) and a very large truck

Page 37

which is well equipped with apparatus which the teachers use in demonstrating scientific farming; methods of improving the home, and most of all the teacher of domestic science and a trained nurse play a very important part on the program of this work.

This group of teachers travel throughout the rural districts of South and Southwest Alabama; going from one community to another with the purpose of assisting the Farmer. As a result of this work farm life in these districts has become happier and more cheerful. It appears that the isoation which formerly existed has been greatly broken.

Dr. Carver has taken a very active part in this great movement of "The Booker T. Washington School On Wheels," which is under the direction of the Tuskegee Institute. Various products which he has extracted from the peanut and the sweet potato, and also from other native products, have been exhibited on the tours through these districts. Hence, the farmers in that section of the State have been fortunate in getting first hand information as to the possibilities of the common products. There is no telling just how far reaching this movement may become.

APPEARS BEFORE UNITED STATES CONGRESS.

After appearing before the Ways and Means Committee. Dr. Carver was allowed fifteen minutes to speak to the members of the Congress, and explain the possibilities of the peanut and the sweet potato. It is said that some of the wisest Congressmen thought that the subject which Dr. Carver was about to present could very easily be examined and explained completely within fifteen minutes.

But after he began opening up his bags, and bringing out one thing after another, and meanwhile explaining in detail, he had grasped the Senators' attention and was arousing their interest. Realizing, however, that his allotted time of fifteen minutes was about out. Dr. Carver began to bring his subject to a close, only to be hurled at with shouts of amazements and hurrahs to, "Carry on, go on, don't stop." As Tuskegee's wizard continued to develop his theme, he had completely gripped his hearers spell-bound. But the continuity

Page 38

of his discourse was frequently broken by recurring applauses. After Dr. Carver had finished he looked at the clock only to find that he had occupied the floor one hour and forty-five minutes, before that great august body.

Dr. Carver's demonstration was unanimously approved, and also attracted wide attention throughout the country. He was heralded as a creative genius, as never before.

Dr. Moton said, "Professor George W. Carver, of the Tuskegee Experiment Station has made some very valuable contributions to the food propaganda. At the request of Dr. Davis Fairchild, of the United States Department of Agriculture, Professor Carver went to Washington and presented to a number of officials of the department, some demonstrations in his experiments with sweet potatoes, and as a result of this and other activities here at the Institute, Professor Carver's work has become widely known. He has distributed by request, hundreds of bulletins on food subjects; has spoken at various places in the South, and has contributed to many publications, especially on the subjects of food substitutes."

EDISON MAKES AN OFFER TO HIM.

Thomas Edison, the world's great inventor, sent his personal representative to Tuskegee for the purpose of making Dr. Carver an offer to join his mighty forces as an assistance in his laboratories at Orange Grove, New Jersey.

When questioned about this offer, Dr. Carver said, there was not much information to be had, concerning the conference between Edison's representative and himself. He said, "You see, Mr. Washington placed me here nearly twenty-five years ago, and told me to let 'down my bucket,' so I have always tried to do that, and it has never failed to come up full of sparkling water." And he continued, "Mr. Washington is not with us any more in person, and I would not be true to this great cause if I should leave here."

Dr. Carver felt that his work at Tuskegee was so far from being complete so he humbly refused to accept Edison's offer. He felt highly honored, but he said that he didn't "feel worthy of the offer."

A small sketch of the

Tuskegee Institute Farm,

and also the pasture on which the dairy cows

are grazing.

Page 39

HIS PERSONALITY.

The average person would probably not be impressed with Dr. Carver, on first sight, as being a man of unusual ability and talents. I recall an incident of significance which occurred some years ago. Dr. Carver had been invited to speak and demonstrate his products in a meeting at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. I prepared for him as he was to spend some time with me.

My landlady became somewhat nervous as she said, "That big man" was going to stop at her home. Early in the morning, about three o'clock, a friend of mine accompanied me to the station to meet Dr. Carver. After getting back to the house we retired until late that morning.

After getting breakfast ready, however, I rushed upstairs to have him come to breakfast, as she nervously poised to see a great giant with a stiff neck and high collar, and with a walking cane, who would come striding downstairs as a mighty oak, with an imposing spirit of self-importance. But she was very much surprised when she saw that unassuming, unselfish, and God-fearing man of three score years, upon whose countenance radiated the spirit of friendliness, peace and good will to all mankind. After meeting Dr. Carver she soon felt perfectly comfortable again. All of that nervousness disappeared.

She found Dr. Carver very interesting, so much until this breakfast resulted almost into a conference, we spent at least two hours at the table. He made an impression upon her which will probably linger forever. She often relates that story now to her friends. This is not the only occasion which Dr. Carver has made lasting friends in almost this same way.

A few years ago Dr. Carver was invited to speak and make a display of his products in a certain city in Texas. The people who made this invitation to Dr. Carver, had made an agreement with the manager of a large theatre to have Dr. Carver speak there, but the manager's wife informed them that she wouldn't permit a Negro to appear in that building. Finally, however, she was persuaded to allow the meeting to be held there. After Dr. Carver had finished making his demonstration of the various products, and also the impressive

Page 40

explanations of it, the manager and his wife were very much pleased and were profoundly impressed in every way. She asked Dr. Carver to be sure to come again and make a complete display of all of his products.

Dr. Carver has lectured to students and teachers of various institutions and colleges throughout the South and parts of the North, both to colored and white people. This takes somewhat an interracial aspect, as his tours have resulted in better understanding between the races. Although he never talks on the so-called "race problem. Dr. Carver always confines his efforts on his work.

A display of the Truck Garden during the Farmers'

Conference at Tuskegee, December 7, 1928.

Page 41

CHAPTER VI.

THE TUSKEGEE FARMERS' CONFERENCE

Dr. Carver's exhibits have been looked upon as one of the outstanding phases of the Tuskegee Negro Farmers' Conference, during the past thirty years.

The primary object of this conference is that of assisting the farmers in that section, or throughout the South, in every possible way. Dr. Carver has always been a factor in carrying out this plan of the late Dr. Washington.

1"From the time I first began working at Tuskegee, I began to study closely not only the young people, but the condition, the weak points and the strong points, of the older people. I was very often surprised to see how much common sense and wisdom these older people possessed, notwithstanding they were wholly ignorant as far as the letter of the book was concerned.

"About the first of January, 1892, I sent out invitations to about seventy-five of the common, hard-working farmers, as well as to mechanics, ministers and teachers, asking them to assemble at Tuskegee on the 23rd of February and spend the day in talking over their present condition, their help and their hinderances, and to see if it were possible to suggest any means by which the rank and file of the people might be able to benefit themselves.

"In the Conference, two ends will be kept in view, first, to find out the actual industrial, moral and educational condition of the masses; second, to get as much light as possible on what is the most effective way for the young men and women whom the Tuskegee Institute and other institutions are educating, to use their education in helping the masses of the colored people to lift themselves up.

"In this connection, it may be said that, in general, a very large majority of the colored people in the Black Belt cotton district are in debt for supplies secured through the 'mortgage

Page 42

system', rent the land on which they live, and dwell in one-room log cabins. The schools are in session in the country districts not often longer than three months, and are taught in most cases in churches or log cabins with almost no apparatus or school furniture.

"The poverty and ignorance of the Negro which show themselves by his being compelled to 'mortgage his crops,' go in debt for the food and clothes on which to live from day to day, are not only a terrible drawback to the Negro himself but a severe drain on the resources of the white man. Say what he will, the fact remains, that in the presence of the poverty and ignorance of the millions of Negroes in the Black Belt, the material, moral and educational interests of both races are making but slow headway.

"In answering to this invitation we were surprised to find that nearly four hundred men and women of all kinds and conditions came. In my opening address I impressed upon them the fact that we wanted to spend the first part of the day in having them state plainly and simply just what their conditions were. I told them that we wanted no exaggeration, and did not want any cut-and-dried or prepared speeches, we simply wanted each person to speak in a plain, simple manner, very much as he would if he were about his own family fireside, speaking to the members of his own family. I also insisted that we confine our discussion to such matters as we ourselves could remedy, rather than in spending the time in complaining or fault finding about those things which we could not directly reach. At the first meeting of this Conference we also adopted the plan of having these common people themselves speak, and refused to allow people who were far above them in education and surroundings take up the time in merely giving advice to these representatives of the masses.

"Very early in the history of these Conferences I found that it meant a great deal more to the people to have one individual who had succeeded in getting out of debt, ceasing to mortgage his crop, and who had bought a home and was living well, occupy the time in telling the remainder of his fellows how he had succeeded, than in having some one who was entirely out of the atmosphere of the average farmer occupy the time in merely lecturing to them.

"I will let no man drag me down so low as to hate him." This inscription is engraved on the statue of Dr. Booker T. Washington, which was one of his sayings, and a manifestation wrought through his labors.

The statue is a typical illustration of his pleading for a fair chance for an oppressed people; through education, industry and thrift.

This group is composed of representatives of

progressive farmers from various states,

attending the Annual Negro

Farmers' Conference at Tuskegee Institute, December 1928. Certificate of

Merit Men are:

Left to Right, J. S.

Seale, Philadelphia, Mississippi; Chris Oliver and

wife, Snowdown, Ala.;

P. L. Anderson, Boley, Okla.; John C. Claybrooks, Simsboro, Ark.

Page 43

"In the morning of the first day of the Conference we had many representatives from various parts as we had time in which to tell of the industrial condition existing in their immediate community. We did not let them generalize or tell what they thought ought to be or was existing in somebody else's community, we held each person down to a statement of the facts regarding his own individual community. For example, we had them state what proportion of the people in their community owned land, what proportion lived in one-room cabins, how many were in debt, the number that mortgage their crops, and what rate of interest they were paying on their indebtedness. Under this head we also discussed the number of acres of land that each individual was cultivating, and whether or not the crop was diversified or merely be confined to the growing of cotton. We also got hold of facts from the representatives of these people concerning their educational progress; that is, we had them state whether or not a school-house existed, what kind of teacher they had and what proportion of the children were attending school. We did not stop with these matters; we took up the moral and religious condition of the communities; had them state to what extent, for example, people had been sent to jail from their communities; how many were habitual drinkers; what kind of minister they had; whether or not he was able to lead the people in morality as well as in spiritual affairs.

"After we had got hold of facts, which enabled us to judge of the actual state of affairs existing, we spent the afternoon of the first day in hearing from the lips of these same people in what way, in their opinion, the present condition of things could be improved, and it was most interesting as well as surprising to see how clearly these people saw into their present condition, and how intelligently they discussed their weak points as well as their strong points. It was generally agreed that the mortgage system, the habit of buying on credit and paying large rates of interest, was at the bottom of much of the evil existing among the people, and the fact that so large a proportion of them lived on rented land also had much to do with keeping them down. The condition of the schools was discussed with equal frankness, and means were suggested for prolonging the school term and building school-houses. Almost

Page 44

without exception they agreed that the fact that so large a proportion of the people lived in one-room cabins, where there was almost no opportunity for privacy or separation of the sexes, was largely responsible for the bad moral condition of many communities.

"When I asked how many in the audience owned their homes, only twenty-three hands went up.

"Aside from the colored people who were present at the Conference who reside in the "Black Belt," there were many prominent white and colored men from various parts of the country, especially representatives of the various religious organizations engaged in educational work in the South, and officers and teachers from several of the larger institutions working in the South. There correspondents present representing such papers as the New York Independent, Evening Post, New York Weekly Witness, New York Tribune, Christian Union, Boston Evening Transcript, Christian Register, The Congregationalist, Chicago Inter-Ocean, Chicago Advance, and many others.

"At the conclusion of the first Conference the following set of declarations was adopted as showing the concensus of opinion of those composing the Conference:

"We, some of the representatives of the colored people, living in the Black Belt, the heart of the South, thinking it might prove of interest and value to our friends throughout the country, as well as beneficial to ourselves, have met together in Conference to present facts and express opinions as to our industrial, moral and educational condition, and to exchange views as to how our own efforts and the kindly helpfulness of our friends may best contribute to our elevation.

"First. Set at liberty with no inheritance but our bodies, without training in self-dependence, and thrown at once into commercial, civil and political relations with our former owners, we consider it a matter of great thankfulness that our condition is as good as it is, and that so large a degree of harmony exist between us and our white neighbors.

"Second. Industrially considered, most of our people are dependent upon agriculture. The majority of them live on rented lands, mortgage their crops for the food on which to live from year to year, and usually at the beginning of each

Page 45

year are more or less in debt for the supplies of the previous year.

"Third. Not only is our own material progress hindered by the mortgage system, but also that of our white friends. It is a system that tempts us to buy much that we would do without if cash was required, and it tends to lead those who advance the provisions and lend the money, to extravagant prices and ruinous rates of interest.

"Fourth. In a moral and religious sense, while we admit there is much laxness in morals and superstition in religion, yet we feel that much progress has been made, that there is a growing public sentiment in favor of purity, and that the people are fast coming to make their religion less of superstition and emotion and more a matter of daily living.

"Fifth. As to our educational condition, it is to be noted that our country schools are in session on an average only three and a half months each year; and Gulf States are as yet unable to provide school-houses, and as a result the schools are held almost out-of-doors or at best in such rude quarters as the poverty of the people is able to provide; the teachers are poorly paid and often very poorly fitted for their work, as a result of which both parents and pupils take but little interest in the schools; often but few children attend, and these with great irregularity.

"Sixth. That in view of our general condition, we would suggest the following remedies: (1) That as far as possible we aim to raise at home our own meat and bread; (2) that as fast as possible buy land, even though a very few acres at a time; (3) that a larger number of our young people be taught trades, and that they be urged to prepare themselves to enter as largely as possible all the various avocations of life; (4) that we especially try to broaden the field of labor for our women; (5) that we make every sacrifice and practice every form of economy that we may purchase land and free ourselves from our burdensome habit of living in debt; (6) that we urge our ministers and teachers to give more attention to the material condition and home life of the people; (7) that we urge that our people do not depend entirely upon the State to provide school-houses and lengthen the time of the schools, but that they take hold of the matter themselves

Page 46

where the State leaves off, and by supplementing the public funds from their own pockets and by building schoolhouses, bringing about the desired results; (8) that we urge patrons to give earnest attention to the mental and moral fitness of those who teach their schools; (9) that we urge the doing away with all sectarian prejudice in the management of the schools.

"Seventh. As the judgement of this Conference we would further declare: That we put on record our deep sense of gratitude to the good people of all sections for their assistance, and that we are glad to recognize a growing interest on the part of the best white people of the South in the education of the Negro.

"Eight. That we appreciate the spirit of friendliness and fairness shown us by the Southern white people in matters of business in all lines of material development.

"Ninth. That we believe our generous friends of the country can best aid in our elevation by continuing to give their help where it will result in producing strong Christian leaders who will live among the masses as object lessons, showing them how to direct their efforts towards the general uplifting of the people.

"Tenth. That we believe we can become prosperous, intelligent and independent where we are, and discourage any efforts at wholesale emigration, recognizing that our home is to be in the South, and we urge that all strive in every way to cultivate the good feeling and friendship of those about us in all that relates to our mutual elevation."

(Booker T. Washington, the Story of My Life and Work, part of Chap. VII, by J. L. Nichols & Company).

Page 47

CHAPTER VII.

HIS CREATIVE ABILITY

Dr. Carver has taken elements from their accustomed associations and brought them into others where they have new and multiplied significance. It is in some such manner as this, that he has been able to accomplish such marvelous results in his scientific investigations. His creative ability has enabled him to dissociate some parts of the sweet potato, the peanut, and other common products, and in his research and experimental work rearranged and reassociated some of the fragments with others. The result is something new, something useful and wholesome for human consumption.

When we speak of Dr. Carver's creative ability we see him as a true pioneer. We see him as a path 'blazer' upon the field of new endeavors, preparing the way for others. We see him as one who creates something tangible and useful.

Dr. Carver has been called a genius, a great scientist, a man with queer ways, and what not, etc. It is probably no more than reasonable for the popular mind to think of him as being an analytic, emotionless person who leads an apparent remote life in seeking remote facts. He takes nothing for granted, however, satisfying himself with only facts and results. His processes art based upon the application of chemical discoveries which lie at the foundation of great enterprises.

Having these facts in view will probably lead the inquiring mind to ask "What manner of man is this?" "He creates what?" "New precedents, new rules or what?" Perhaps, but more important, he makes possible in the future, situations enriched with further possibilities, more comprehensive understanding, broader and fairer relations. Moreover, he is a great factor in the building of a new civilization.

The reasons why agricultural conditions in the South became different from those in the North were at first chiefly due to climate and the conditions of the soil. In the South, with its rich land and long, warm growing season, tobacco

Page 48

proved almost at once to be a money-making crop. Rice and indigo, and later, sugar cane and cotton were found to be exceedingly profitable, especially when cultivated on a large scale. Commercial production of this sort required extensive cultivation, cheap labor, and sufficient capital to carry on operations.