Slavery Illustrated,

in the Histories of Zangara and Maquama,

Two Negroes Stolen From Africa and Sold Into Slavery.

Related by Themselves:

Electronic Edition.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Elizabeth S. Wright

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc. and Elizabeth S. Wright

First edition, 2003

ca. 115K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2003.

Source Description:

(title page) Slavery Illustrated, in the Histories of Zangara and Maquama, Two Negroes Stolen From Africa and Sold Into Slavery. Related by Themselves

(running title) Slavery Illustrated

38 p.

Manchester:

Printed and Published by Wm. Irwin, 39, Oldham-St.

London:

Simpkin, Marshall, and Co.

[1849]

Call number Micro-35 E185 .S37x no. 53 (Kent State University)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

The publisher's advertisement on p. 38 has been transcribed as completely as possible.

This electronic edition has been transcribed from a print-out of the microform held by Kent State University.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Fugitive slaves -- Fiction.

- Slaves -- Fiction.

- Slave trade -- Africa -- Fiction.

- Slavery -- Fiction.

Revision History:

- 2004-03-15,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2003-09-29,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2003-08-28,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2003-08-28,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

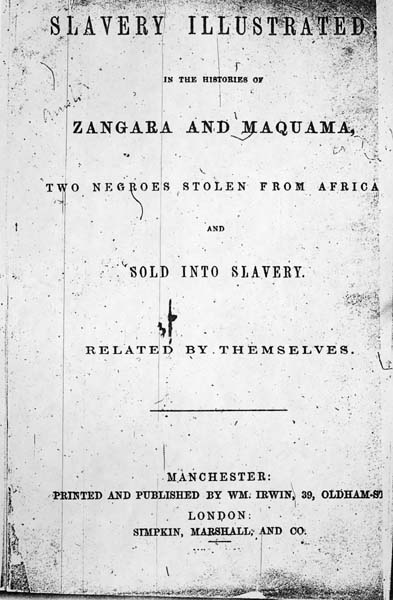

Page i

[Title Page Image]

SLAVERY ILLUSTRATED,

IN THE HISTORIES OF

ZANGARA AND MAQUAMA,

TWO NEGROES STOLEN FROM AFRICA

AND

SOLD INTO SLAVERY.

RELATED BY THEMSELVES.

MANCHESTER:

PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY WM. IRWIN, 39, OLDHAM-ST.

LONDON:

SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, AND CO.

Page ii

STARTLING FACTS! Four Hundred Thousand human beings are annuall [cut off on microfilm] ir homes and friends, to be sold by public auction to the highest bidder into [cut off on microfilm]

[cut off on microfilm] rly Three Hundred Thousand of this mighty host perish by fire and sword i [cut off on microform] or from privation and suffering.

[cut off on microfilm] re are now, in various parts of the world, seven millions of our fellow creature [cut off on microfilm] ry.

"What!--God's own image bought and sold!

And bartered, as the brute, for gold!"

Whittier.

Page iii

INTRODUCTORY REMARKS.

NEGRO SLAVERY is beyond all question the most gigantic system of oppression and iniquity which has ever disgraced our fallen world or degraded our fellow-men;--the most appalling enormity and outrage ever committed under the stimulus of a vicious self-interest. In whatever light we view it, it is entirely at variance with the genius and spirit of Christianity; and it is our duty to expose, by all possible means, a system so contrary to every principle of justice, humanity, and religion.

Whilst millions of our oppressed and manacled brethren are still groaning under its cruelties, and panting for deliverance from its thraldom, I deem no apology requisite in presenting anything which may excite a feeling of sympathy for that portion of suffering humanity whose own voice has but little chance of being heard, and when it has an opportunity of being raised in self-defence, is too often but little regarded.

The purpose of the following pages is to expose some of the evils attendant upon Negro Slavery, in the hope of rousing amongst the friends of justice and humanity a renewed interest in the oppressed, and to promote the early and total abolition of a system involving such complicated distress.

He who can peruse these Narratives without a tearful eye, and without being filled with an abhorrence of Slavery, must have a flinty heart indeed. The reader must not suppose that they are selected as rare specimens of the cruelties or wrongs of Slavery. They do not comprise incidental aggravations, nor casual ills, but such as mingle always and necessarily, more or less, in the lot of every Slave.

One half of the dark deeds of Slavery have not yet been revealed. Fresh evidences of its unequalled atrocities are pouring in upon us from every side. Pennington, Douglass, Brown, Garnett, and others, who have escaped from the horrors of American bondage, are now telling their own tales. May these have the effect, not only of exciting sympathy for the oppressed, but of shaming America out of her adhesion to a system so abhorrent to Christianity and to her republican institutions.

Page iv

Those who have suffered from Slavery are best able to depict its true character, and raise the indignation of free men against it. Surely none can read the realities of such an accursed system, without shuddering with horror. What must it then be to witness them! Its barbarities affright, its pollutions sicken the soul. Very justly has it been called "the world's crowning iniquity;" it is human nature's "broadest, foulest, blot;"--Heaven speed its eternal overthrow!

The following Narratives, though unadorned with fine touches of rhetoric, are deeply affecting. They reveal but a small portion of the evils of Negro Slavery, yet it is hoped their recital may prove serviceable to the cause of bleeding humanity, in raising renewed thoughts of pity towards those who still "drag the chain, and feel the lash," for the "grave offence of having a skin not coloured like our own."

May the sorrows and sufferings here related touch the indifferent with sympathy for their oppressed bondsmen--may they unlock the springs of sensibility which lie concealed in many an unawakened, yet not unfeeling, heart, to gird on the sword of the Spirit, and do battle for the defenceless Negro Slave.

Reader! assist, I implore thee, in the great contest for liberty, that the full blessings of Christianity may be bestowed, and "the dew of kindness distilled, upon the most helpless and injured portion of the human family." "Laurels more fair, victory more glorious, never yet graced the annals of christian warfare, than would be won and worn by thee, if clad in the armour of God, thou wouldst assail the battlements and bulwarks of oppression till they should totter and fall. Proudly as they lift their summits to the skies, exulting in having stood long as conspicuous and lofty as they stand now, yet vain is their glory, deceptive is their strength. The very citadel of Slavery is founded upon 'hay and stubble,' and the frail edifice is no better prepared to resist a steady vigorous charge from a mighty phalanx of united Christians, than is the house of sand which the child erects upon the shore, to withstand the force of the overwhelming billow. Even as the vestiges of that fragile toy are borne away into the sea, so would the onward march of those great conquerors, Religion and Virtue, sweep away every trace of an institution which mars the beauty of God's moral creation, by interrupting the happiness, and defiling the purity of mankind."

Leeds, 11th Month, 1849.

W. A.

Page 1

ZANGARA,

THE NEGRO SLAVE.

BEING stolen away from my dear parents and relations when very young, and after much cruel treatment sent from my native country as a slave to America, I am unable to give a particular account of my early life. A few incidents connected with my happy boyhood, are, however, yet vividly impressed on my memory, which I shall endeavour to narrate as correctly and as concisely as possible.

My name is Zangara: I was born in a small village in Africa, called Tamata, situated a considerable way up a narrow valley, down which ran a stream into a very large river at the bottom. This river, I have now reason to believe, is the same as Europeans call the Niger. The little valley was well wooded both with underwood and large trees. As to the particular situation of Tamata I know nothing further, than that the sun at noon was always very nearly over our heads, so that we had little shadow; and that it was, in one direction, about twenty days' journey from the sea. My father's house was the largest in the place, and he was considered as the head man, though I cannot remember that he had any particular title, but he was always referred to in any dispute. He had a large piece of ground, enclosed and cultivated. My mother was very fond of me, being her only child; making, indeed, too much a pet of me. This, I rather think, made me a little too full of myself, for I can remember, that even then, I must be at the head of my playfellows. I was, however, tolerably expert at any exercise that I engaged in. Being near so large a river, and the climate so warm, we were almost as much in the water as on land. I cannot at all remember learning to swim; it seems to me that I could always swim, and I learnt to dive by practice, so that I could remain a very long time together under water. This constant exercise seemed to strengthen me very much, and I scarcely then knew

Page 2

what fear was. I was never fond of working in the field, but was never tired of hunting or fishing, in which I was very skilful, as well as at making spears, fishing-tackle, boats, and all sorts of implements. Before I was ten years old I had made, by myself, a fishing boat that would hold three of us very well.

There could not exist on earth a happier society than ours then was. We all lived harmoniously together, having no disputes, that I ever heard of, but what my father could adjust. We were entirely to ourselves: what we had to dispose of, which consisted principally of elephants' teeth, the skins of wild beasts, and some little gold-dust, was taken twice a year, by our trading-men, to a place distant three days journey; and such things as we required were brought back by them in exchange. They were generally absent about seven days, and their return was hailed with delight by the whole village; we generally sat up throughout the night, whenever we thought it probable they might be returning. The rapture with which both old and young crowded about them is inconceivable; while their own delight on again getting home, and exhibiting their precious purchases to their welcoming friends, was little less. Nothing could exceed in loveliness such a scene as our valley exhibited, when their return happened to be in the night near the full moon.

One such occasion I can never forget. The brightness of the African moon, on recollection, appears greatly superior to any I have since seen. The night; with a full moon, is almost as light as day, and the night air is exceedingly pure and delightful. The Jug-jug, a bird peculiar to Africa, was singing on all sides of us. We had made garlands of flowers with which the girls danced. We boys had our spear and club dance, while the older people sung and played on the tom-tom, and other instruments. Our fathers heard us at a distance, and answered our singing by a correspondent song. As soon as we heard them, the rapturous shout that was uttered by every one present, can only be conceived by those who heard it. We soon met, and returned altogether up the banks of the little glittering stream, the happiest party, I will venture to say, on the face of this earth. When we arrived at the village my father ordered all to deposit their burdens, and assemble in silence He then returned thanks to the Gracious Spirit for their success and safe return, after which we all seated ourselves to the meal which had been prepared. This being ended, the examination and admiration of the valuable cargo which our merchant men had brought home, employed and delighted us till daylight.

Page 3

I am persuaded that it is impossible for those who have lived all their life-time in society, such as exists among white men, to conceive the pure and almost unalloyed happiness which is to be found among Negroes, situated as we then were. Sickness was almost unknown among us: we had few wants, and those easily provided for, or rather the providing for them was itself an amusement. The aged enjoyed their rest, and the younger their play. In all exercises I excelled, whether they required strength, or agility, or both, and was therefore generally looked up to as a leader. I was the best climber, the best runner, the best swimmer, the best wrestler, the best fisher, and the best hunter.

Our valley was but little infested with savage beasts. For many years none had been suffered to rest near it: now and then a straggler would find his way to it, and do some mischief, but he was soon either destroyed or driven away. On my excursions with our people, twice a year, about six days' journey towards where the sun rises, in search of elephants' teeth and gold dust, I had opportunities of seeing many of the savage animals, and becoming acquainted with their habits; indeed, we generally brought home a few skins of such as we had killed. I think I was not more than fourteen years old when one of these wild creatures found his way to our valley, and on two successive evenings succeeded each time in carrying off a child,--the children straying fearlessly anywhere by themselves. I was always very fond of children, and one of these, Natee, a girl about five years of age, was a great favourite with me. During two days we sought the savage, but without success; I thought, however, I could discover him. After the family were in bed, I went quietly out unperceived, and climbed into a high plantain tree, where, in the course of two or three hours, I heard a rustling among the bushes, and soon saw the huge brute pass near, with a pretty large animal of some kind in his mouth. I could distinctly enough see the place in which he stopped. I was now determined, if I could, to revenge the death of my favourite little Natee, as well as to prove to the village my courage and prowess. Accordingly, I returned home, and early in the morning, armed myself with a long knife which my father brought me on returning from their last excursion,--a treasure with which I was most highly delighted. This, and my short spear, were all the arms of which I was possessed. I went alone, resolved to share neither the danger nor the glory, but I did not soon succeed in finding the savage, and began to think that I must return unsuccessful, when, in a thick covert, not ten yards from me, I caught the rays of two glaring eyes. I immediately

Page 4

stopped, and grasped my knife in my right hand, and the spear in my left. I soon saw that it was an immense tiger. He eyed me a few moments as he lay, and then crouching, crept to the nearer side of the covert. He slowly raised himself upon his legs; his tail was in quick motion; he fixed his eyes steadily upon me, and I fixed mine as steadily on his. I knew his ways, and had taken my resolution. I advanced within five yards of him, and then stopped. He instantly made his spring--I threw myself on my back, and plunged the knife into his bowels as he leaped over me;--then instantly sprung upon my feet, and taking the spear in my right hand, hasted towards him before he could recover himself. From the wound, and missing his aim, he had fallen, and as he rose with his mouth open, I plunged the spear down his throat. He now rolled over, struggled a few moments, and died.

When I stood and surveyed the enormous yet beautiful beast, as he lay extended before me, though my heart exulted, I could scarcely help shuddering. He was by far the largest animal of the kind I had ever seen; indeed he was declared to be a most noble tiger by all our neighbours. We flayed him, and my father was so pleased, that he declared the skin should never go out of the family. Alas, how short-sighted is man! I now rose very high in the estimation of all my companions, and I am afraid, too much in my own.

It was, I think, about two years after this, that as I was one day strolling along the banks of the Niger, when the river was pretty high and rapid, with my small fishing-net in my hand, I saw something at a distance, floating down the middle of the stream. As it came nearer, I saw that it was a small boat, in which was seated a young woman without either oar or paddle, so that she had no command over it, but drifted at the mercy of the water. She did not appear alarmed, but made signs for me to stop the boat. I was going instantly to throw myself into the river, without anything but my little net to serve as a paddle, when I was struck with horror on beholding one of the largest kind of alligators swimming within ten yards of the little boat, which he could easily have dragged down under the water. I instantly seized my knife, which I had laid down with my other things, and rushing into the water, very soon overtook the frightful monster. The young woman had now discovered him, and screamed loudly for aid. While the alligator was only attentive to the boat, I contrived to throw myself across him, and scrambling forwards till I could reach his head, I plunged my knife first into one eye, and then into the other, in an instant. He immediately

Page 5

sank. I called to the young woman to take hold of the net staff, and putting the net over my head, swam to the shore with all my strength and speed. We reached the shore in safety, where a considerable number of my companions, attracted by the screams, were assembled. They afterwards killed the alligator. The young woman, whose name was Quahama, had been brought down the river nearly half a day's journey, having heedlessly put the boat off the shore, and then lost her paddle. She went with me to my father's, who sent a messenger to inform her friends where she was. They came for her the next day, and I attended them back. Their village was on the other side of the river, and much larger than ours. Her parents were so thankful that they would not let me leave them till the end of several days, and then compelled me to take, as a present to my father, a considerable quantity of gold dust.

I had hitherto thought little or nothing of love; now, however, I could think of nothing else. Quahama certainly appeared in my eyes the loveliest creature that I had ever beheld. I could neither think nor dream of anything else; I therefore at length requested my mother to ask my father's consent. She told me that he intended another for my wife, but she acknowledged that they both thought highly of Quahama. To be brief, my father's consent, and that of Quahama, and her parents, was at length obtained. I was then turned sixteen; Quahama more than a year younger. I had, however, before we could be married, a home to build; but this was not a long business, for it had always been the cus tom, on such occasions, for every man, who was able, to assist, and I had, in the course of a short time, a very good house built. Quahama's father was a topping man in the village. My father gave a handsome dowry for her, and they both together contributed to make her the smartest bride that ever came to Tamata.

During the first six years of our marriage I do believe the world did not contain a happier couple. If ever woman was without fault, that woman was Quahama. We had during that period three children; the two oldest, girls; the youngest, then in the arms, a boy. I have since learned that happiness is not the lot of man upon earth. I therefore, now, do not wonder that, after enjoying so much of it in early life, I have since experienced a proportionate degree of misery. Nor do I now repine, for these sufferings of the body have been the means of teaching me that they are good for my soul, and that they are the dispensations of a merciful God. But to proceed with my narrative.

Page 6

I had now been admitted to accompany the merchantmen on several of their trading expeditions; and on the last of the kind, we were induced to extend it full four days' journey beyond what had before ever been taken, being told, that if we did so, we should be able to trade to much greater advantage, as we should then reach the place to which the White Men came. This I much liked, for I had heard talk something about White Men, but considered it only as a fable. Now, however, I learned, not only that there were such, but that I should see them, and my spirits were highly elevated on the occasion, as I had a strong propensity for novelty. We at length arrived at the station, where we found a very large number of Negroes assembled, and were conducted by them to a great building belonging to the white men. I cannot describe my feelings at the first view of these strangers. I found the white men very different from what I had anticipated, being so covered with clothing, that there was hardly any knowing, except by their faces, whether they were black or white. They had a great variety of articles to dispose of, such as I had never seen; the use of many of which I could not comprehend. A Negro, who could speak both their language and ours, told them who we were, and bargained for us with them. It was now that I first saw a gun, heard its report, and witnessed its effects, and I was indeed truly astonished. A watch and a looking-glass greatly excited my wonder. They were, however, things of too much value for our purchasing, The usual necessary and trifling ornaments we certainly got much cheaper than formerly.

My ideas of the powers of the white men were, that they were superhuman; of their humanity I did not think so highly, when I had witnessed a great number of the most wretched Negroes that my eyes ever beheld; indeed, I had never seen wretched ones before. They were fastened together, and appeared so miserable and wearied, that I shuddered to look at them. My father told me (for they did not speak our language), that they were Slaves, bought by the white men, to take to their own country to work for them; and that they were brought by those who had them to sell, from a great distance. This was the first time I had ever heard of Slaves. My father said, that though we had got our goods cheaper, he wished that we had never come. He was sure, he said, that no good would arise from having anything to do with white men. They had been very inquisitive about the place that we came from, and other things, which aroused his suspicions. Youth is not often suspicious, and I had dreamt of no evil.

Page 7

My father's spirits, after this journey, forsook him: he had learned so much respecting the conduct of the white men, that he could not rest. He induced us all to habituate ourselves to act together in self-defence, saying, we might soon have occasion to do so in earnest. Though I could not see the necessity, I was no way indisposed to the preparation. I could use the spear, the knife, and the club, as dexterously and effectually as any one.

It was about three moons after our trading expedition, that, on a fine moonlight night, when, with my wife and my three children, I was fast asleep, I was awakened by a dreadful noise, which I knew at once was caused by the guns of the white men, for I had never heard any other noise at all like it. This was accompanied by continued shouting and screaming. I instantly jumped up, seized my spear and my knife, and telling Quahama to attend to the little ones, I rushed out of the house. The uproar and confusion were horrible, but I had no time to attend to small matters. Half the village was in flames! The roaring and flashing of the guns, with the shouts of the men, and the screams of the women, were truly appalling. I turned towards my father's house; two ruffian white men were dragging him, bleeding, away. I rushed upon them, and (I believe) I slew them both; but, in the instant, I heard the screams of my wife and children; I turned round, and saw two others of the white demons hurrying her with them. She had the infant in her arms; the two girls were endeavouring to get to her. I did not hesitate a moment, but springing upon them, aimed a blow at one with my knife, which must (had it taken effect) have ended his wickedness; but he parried the stroke with his arm, and the infant received it. The scream of my wife still rings in my ears!

Rendered desperate by something like madness, I threw my spear away, and closing with the wretch, heaved him from off his legs, and dashed him to the earth. His sword flew out of his hand; I seized it, and rushing with fury upon the other, I plunged it into his body. I was now, however, seized from behind, and completely overpowered. The tumult began to subside. The whole village appeared to be in flames. It was as light as the day. The firing of guns, with the shouting, had ceased, but the screaming of the women and children in part continued.

All began now to be assembled together. The negro men were fastened two and two. Many of them were severely wounded. The wives and children of those who had any, clung to them. Quahama, with my

Page 8

eldest daughter, Mene, soon found me out. The savages had thrown the infant into the stream;--the younger girl had been trampled to death in the scuffle when I was taken. My father, I believed, had been killed, and my mother had perished in the flames, being unable, on account of her infirmities, to leave the house.

The white kidnappers divided us into three parties, marching them off separately, in different directions. There were at first, in our party, 24 prisoners, men, women, and children. I had received no hurt, so that I was enabled to carry the terrified Mene without much difficulty. Quahama uttered no complaint; on the contrary, she was ready to extend assistance to several who needed it. The kidnappers had brought a number of camels, eight of which we had with us. These carried most of the white men, some of the spoil of the village, and a few of the children, with the badly wounded men and women.

In seven days we reached the place where we had met the white traders, who, I had no doubt, were the cause of our captivity. We were kept at this station two days, to rest, and to make some arrangements for the remainder of the journey. Several of our people were now scarcely able to crawl along: one of the wounded men had died. Poor Quahama was very foot-sore, and almost exhausted. I endeavoured to comfort her as much as I could, though my own spirits began to fail me. During the first days I meditated nothing but escape and revenge; but, by degrees, all hope forsook me, and I became gradually languid, the food which we were allowed being scarcely sufficient to sustain nature, and I contrived to let Quahama and Mene have the most of mine, without their knowing it. I understood that we had still a very long way to march, and what was to become of us in the end I could by no means understand.

It would be useless to describe the sufferings which we endured during twenty days' more travelling, with the exception of two others, on which we rested. Four more of our people died. Quahama became so weak, so ill, and so lame, that if she had not been placed upon one of the camels, she must have died too. For myself, I could still manage to walk. I thought that the head white man let me have more food than any of the rest: nor did I get beaten so much as others. The first, I have since learned, arose from being considered the stoutest, and therefore the most valuable captive; the latter, from my strength enabling me to walk better than the rest. My companion, to whom I was coupled, being much weaker than myself, was so beaten that his back was quite raw. At length those of us who were still alive arrived at the end of our

Page 9

journey. My companion died two days afterwards. Now it was that I first saw anything like European houses and customs, and, what was more surprising to me, a large ship and the sea. My spirits, however, being well nigh broken, I beheld all these wonders with comparative apathy. The present and future sufferings of my wife and child, as well as my own, engrossed almost the whole of my thoughts and attention. We were put here into a large building, till many other slaves were brought in. The language of some I could partly understand; of others, not at all. We were taken out occasionally in parties for air and exercise, and by degrees I recovered my strength considerably. My poor wife seemed scarcely alive, and yet she uttered no complaints. Mene was her constant care. As we were not now always shackled, I should certainly have attempted revenge and escape, if it had not been for my wife and my child; as it was, I determined to share, and, if possible, soften their sufferings.

There were now several hundred poor wretches like ourselves assembled, all equally ignorant of the fate which awaited them, but all well assured that it must be misery. The Negro, however, seldom complains, and almost all of us brooded over past happiness and coming affliction. We none of us knew either much of God or religion: but we were all convinced, that after death we should be happy with our friends in regions of bliss. At length the time came that we were taken out in parties. I was one among the first called. We were taken to the seaside, and into that most wonderful thing, the large ship. How much should I have once examined and admired such an astonishing thing, but I was then so bewildered with strange feelings that I could attend to nothing. We were taken down some steps, and made to creep into a large low place between two floors, so near together that I could not by any means sit upright. More and more of the poor trembling wretched Negroes were brought down and crowded in, till we had only just room to lie in rows close to each other. The place was almost dark, and soon became so hot and close that we could scarcely breathe. When our floor was full, we heard them bringing others, to lie in the same way on the floor above us. Sighs and groans were all that were uttered among us, but from above we soon heard the appalling shrieks and cries of women and children. Though I was almost suffocated, I now felt the most for my poor wife and child, whom, I had no doubt, were among the sufferers above. It seemed to me impossible for any human being to exist for a day in such a situation. The stench soon became intolerable, and I

Page 10

could only conceive we were all put in there to die. The horrid screams above even increased. It was evident they were still storing in more stolen Negroes.

At length we heard a very loud talking and shouting of the white men above our heads, and the ship began to heave about in a strange way, so that I was pretty sure that it was moving along. After a while it became quite dark, and the motion of the ship was much more violent. This, with the suffocating stench, made most of us very sick. I fully expected that I was dying; indeed, it now seems wonderful to me that any of us could survive that dreadful night. Most of us, however, did survive it; four were found to be dead, when in the morning, the white men came to examine and bring us something to eat. They were taken away, and we heard them thrown into the sea. For my part, I was so nearly dead that I could eat nothing. After a while, a few of us were taken at a time up the steps on deck, into the open air.

I can never forget the sensation which I experienced on again viewing the sky and breathing the fresh air. We could see no land: nothing but water all around us, the waves tossing themselves and the ship in a strange manner. All about and above me seemed wonderful; but I was still sick, and was soon driven again, with the rest, to experience once more, the dreadful horrors of the preceding night. I would have given my life to know what had become of poor Quahama and Mene. It seemed impossible that, if their sufferings had been anything like mine, they could have survived: indeed, we had in the morning heard so many splashings in the sea, that I could have no doubt of there being many dead besides the four taken out of our chamber.

To describe our dreadful sufferings from day to day, through more of them than I can at all number, is as unnecessary as impossible: they can but be imagined. Our attendant every morning found some one or more of the sufferers, who, by death, escaped from their tormentors; and we began, by degrees, to have room enough to turn ourselves about; our bones, from our getting so thin, and lying so long on the bare boards, being ready to start through the skin; indeed, in many instances they did so. To add to those sufferings, dreadful as they were, the weather now became so intensely hot, that it was at all times unbearable, there not being a breath of air to move the ship, which remained still. This killed many, and brought on a complaint, which produced blindness, both among the white men and the Negroes. When the latter became quite blind, they were taken away and we saw them no more: I have

Page 11

no doubt they were thrown alive into the sea. There were not now half of us left. After about seven or eight of these hot days, the wind all at once began to roar, and the ship to toss in the most violent manner: we were rolled about in all directions, like empty barrels. After a while, by laying hold of each other's hands, we contrived to keep steadier. The second morning of the storm, I thought that the hand which I had hold of was very cold, and soon found that the owner of it was dead. We often heard the screams of the women, mixed with the uproar made by the white men; and my heart sickened, though I could scarcely doubt but that Quahama and Mene were both long since dead. The storm continued very long, and was so violent at times, that the water broke in upon us, and we expected to be drowned.

At length, during the night, a most terrible crash and shock threw us all at once on a heap together at one end of the room. The most dreadful uproar ensued. We could hear the waters rushing in from some quarter. All seemed confusion, the women and children screaming violently. Nobody came near us for many hours. All was bustle and confusion. The ship was tossed about violently. Several of our Negroes were dead, but no man came to take them away. It was the second morning before any white man appeared, to bring us anything to eat, and then but little. During the day, the storm and the bustle began to abate; the dead and the blind, two of the former and four of the latter, were taken away. We were told that we must not have so much to eat and drink as heretofore, as they had thrown most of the casks into the sea. We had, indeed, after this, so little allowed, that we were almost famished, and dying of thirst. More of us daily became blind; at length, when there were not above ten of us left, we were told that we were near the end of our voyage. I then felt quite indifferent about it; a kind of stupor had seized me, and I became almost regardless of every thing. My eyes were only a little affected: but I had perceived, when taken above, that there were not above eight or ten of the white men that could see at all. As to the hundreds of blind Negroes, we saw no more of them, excepting a few that became blind during the four or five last days.

At last, we got to the end of our voyage; the vessel stopped, and in a few hours we were all taken on deck, and presently landed. We were then fastened together, being in all only six that could see, and marched into a large town, the houses in which were very high and grand. While I could see the ship, I kept looking back and perceived both

Page 12

women and children, but could not tell who they were. I walked the first, and as I went on, a fine dressed white man took hold of me, and stopped us. He spoke for a long time to the white man with the whip, who at last came and loosed me from the rest. I then understood that I was to go with the smart white man. I felt glad of it, as he looked less ill-natured than any of the other white men whom I had seen. While he was looking at me, feeling me, and making me walk about, I saw a white man with a whip coming on with the women and children, not more than ten of each. My heart jumped against my side, and I could hardly stand. My new master (for such he was) turned and went to look at them. I, trembling, did the same. I could see neither Quahama nor Mene. My heart died within me. I was turning away, when I heard my name called--it was by a poor emaciated creature. She called again--I knew her voice,--it was Quahama! The child was with her--I flew to them--I hung about them--I cried like an infant. This attracted the notice of my new master. He did not appear at all moved, but he had my wife and child loosed and brought to him; he examined them very carefully: I fell upon my knees to him, to beg of him, as well as I could, to buy them. He understood me, but seemed to take no notice, and continued his examinations. He then talked with the driver, and, in the end, he brought them to me. We all fell on our knees to him, to thank him, with our words and tears, but he seemed to understand neither. He called to a white man with a whip, who gave us to understand that we were to go with him. I took Mene in my arms, kissing the dear altered child with all a father's affection. Poor Quahama, whom I could still scarcely know again, pressed us to her fluttering heart, till a slight touch of the whip reminded us that we were to obey I do not know whether it was happiness or not; but though I continued to weep, as did Quahama, I would not have changed feelings or places with the white man himself.

The whole of our past adventures and sufferings seemed like a dream so different had they been from anything that, waking, we could have conceived. After stopping to have food given us, which tasted delicious, we were marched into the country for about two hours, when we came to a number of small houses, into one of which we were put. We had food given us, and were then left to ourselves.

The report which my wife had to give me of her sufferings was very similar to my own. We could not tell what was next to befall us, though we understood that we were to labour in the grounds. Poor little Mene

Page 13

was not so exhausted as we were The next morning we all felt much revived, and little Mene began to play about at the door. We saw many parties of Negroes at work at a distance, and we concluded that we were to do the same. In a little while, the man who brought us our food, came and made signs for me to go with him. Poor Quahama trembled exceedingly; I tried to give her hopes, which I did not feel myself. I was taken to a building at a distance, in which was a fire: two men who were there, laid hold of me, and held my arms back. Reduced as I was, I felt that I could have overpowered them; but, on my wife's account, I thought it better to make no resistance, though, when the man who brought me took a red-hot instrument from the fire, and put it to my breast, I expected that I was to be murdered. The operation pained me exceedingly, but I uttered no cry; a deep mark of the shape of the instrument was left upon my breast; to this the man applied something, for what purpose I could not tell. When this was done, I was taken back, and my wife taken to the same place. During her absence I felt more misery than during my own. When she returned, I found that she had been burned in the same way, but on the left shoulder. The child was not taken at that time, being probably thought too young.

The next morning, the man with the large whip came and took me with him, leaving Quahama and Mene behind. We found several parties, a man with a whip to each, digging the earth. I had one of the digging instruments given to me, and was put to one of the parties, who were all men, to work with them in a row. I had never been used to dig in that way before, besides which, my breast was very stiff and sore where they had burned it with the red-hot iron, that I felt rather awkward; I contrived; however, to keep up with the others, who certainly did not work very hard. The driver, I thought, seemed pleased with me, and never struck me, as he frequently did the others, with his whip. They certainly did not seem disposed to do any more than they could help: in fact, if I had been well, and used to the work, I could, if left to myself, have then done as much as four of them did without at all fatiguing myself, provided that I had been well fed. And this I always found afterwards to be the case. It was the heat that I found the hardest to bear. My wife continued so weak, that she could scarcely walk; it was therefore three or four days before she was set to work. When she was, I thought at night that she would have died, though she only worked half the day. The driver, thinking her idle, or wishing to let her feel what she must expect if she was so, had cut her severely with the whip

Page 14

upon the right shoulder, her left being still very sore with the burning with the red-hot iron. She had never been used to any work of the kind, and was both weak and frightened. It was a long time before she could bear to work the whole day. We did not work less than fourteen hours in the day, and part of the year, in crop time, I had to be up three nights in the week. One day in seven we did not work in the fields, but every man had a small piece of land for himself, on which to grow what he liked for his food. I had a piece given me; and these we dug on the Sunday. On that day too, those who had anything to spare, took it to exchange for something else with other Negroes, who met them at a place called the market, about a quarter of a day's journey off. And some of them used to dance and sing. I could not do either; I was so very sad. I remembered my poor murdered father and mother and two children, with what Quahama and myself had suffered. When I saw how much she was altered, how little chance there was of her living long, and how miserable the rest of our lives must be; and when I reflected on what, in all probability, my poor little Mene had to suffer, I did not feel any disposition either to dance or sing, otherwise, I could have beat them all at either. If I could have but been allowed, any way, to have done my wife's work for her, besides my own, I should have been very glad, and I could have done it with ease, but we were forced to work all together.

I had often had opportunities of witnessing, as well as sometimes feeling, with what severity the driver exercises his power and his whip. It is not always for faults, nor even in anger. Sometimes it is mere wantonness, and, as it were, to exercise himself. Sometimes I have seen him do it to show his dexterity. If a fly happened to alight on the shoulder of one of the Negroes, he would try to kill it with the end of the lash, and at the same time, probably, draw blood from the smarting sufferer, who dared not utter a word; for, if he did, he would, in all probability, have come off much worse. If one of the gang happened, from any cause, to lag behind the others, the lash was sure to help him forwards quickly; or if the driver fancied that any of them did not strike the hoe deep enough, instead of speaking to him, he would give him a smart cut on a particular part. Nay, if any one had given offence to the driver, he was sure to feel the effects of it from the whip, during the whole of the day.

I have often seen both men and women, when they have been too late in coming to work, to start with the rest, taken, by order of the driver,

Page 15

by four Negroes, thrown down, and held by them, with their faces to the ground, while their driver has given them as many lashes as he chose, on their naked bodies; often till the blood has flowed copiously. Nay, I have seen some of the older of the Negroes with the parts so hardened by frequent whipping, as to be there almost without sense of feeling. All of them submit without any resistance; and, if required, would lay themselves down to be flogged without holding. These are every day occurences; but when any more serious crime has been committed, such as theft, or running away, so that it is necessary to inform the overseer, the punishment is often dreadful; nay, this is not unfrequently the case on false accusations. Many such cases I have known, when the innocent sufferer has been almost killed.

In one instance, I was appointed, with several others of the stouter Negroes, to attend a party of whites to take or destroy a number of runaway Negroes, who had formed considerable village in the mountains, many miles from our plantation. They had most of them been there a great many years without being heard of. It was towards evening before we came to the high mountains. I had never seen any like them; they surprised me very much. The passes between some of the rocky ones were so narrow, that we could only go through them one at a time. I did not much like my employment, and had it not been for my wife and child, should have been ready to go over to the side of the Negroes. As it was, I was forced to submit. I was pondering on these things as we marched along, when, all at once, I was startled by the report of four or five muskets almost close by us, followed by a shrill shout. Those who were before me, and had escaped the balls, quickly retreated back; but before they reached me, another discharge was heard, and another shout. We saw no one. Four of the whites and one Negro were shot. We were obliged to leave them to their fate, and make the best of our way to the nearest plantation.

From this place our leader sent back for others to assist us, being determined now, if possible, to extirpate the whole colony. The next day we were joined by about twenty more. We now got a guide, who took us by a more open but more distant road. We had nearly reached the mountain settlement before we were discovered; but it was not long after this that several of our people dropped. The firing came from unseen foes, on all sides. We had nothing for it, but pushing on as fast as we could towards their settlement. Before we came in sight of it, I was surprised to see the land inclosed, and highly cultivated. The village

Page 16

was beautifully situated and well built. We now gave a shout and hastened on, as the land about was pretty open and flat. The men who had been dispersed to oppose us were now coming in, but too late. The women and children were trying to escape, but our balls brought most of them down. We rushed into the houses, all of which were quickly in flames. The men who still opposed us were soon destroyed; a few, however, escaped, with some of the women and children, into the woods.

We had now time to rest, refresh, and look about us. It seemed a most delightful place. The original founders had now lived twelve years in security and peace, and they did not seem to have been idle during the time, for the ground was highly cultivated and productive, the crop on the ground being almost ready, and very abundant. This, however, after due rest, we had orders to destroy; so that we completely laid waste the whole establishment. We had brought a few dogs with us, so the next day was appointed for hunting the fugitives.

It is impossible for me to describe my feelings during all these transactions; but I was constrained to repress them. I took care to hurt no one, but I could do no good. The scene was dreadful, and only surpassed by the destruction of my native village, Tamata. But, perhaps the most horrid part was the next day's work, of hunting and shooting them in the woods, particularly the women and children, some of the latter in the arms; for our people were so exasperated at the resistance and loss which they had encountered, that they spared none. I was not of the party, being left with a few others to collect and bury the dead, of which we found more than thirty, and a very grievous business it was.

Having at length completed the destruction of the place and the people we set out on our return, loaded with a good deal of spoil. We had not however, proceeded far, before one of the dogs began to bark, and hasted up the hill to the mouth of a small cavern. We stopped, assured that we had found something: presently there crawled out a poor old Negro man, who fell on his knees, holding up his hands in supplication; I would have given my own life to have saved his; but it would have been in vain. One of our white men took deliberate aim, and the helpless old creature dropped. The party shouted, and marched off.

With an almost bleeding heart I lingered behind, and when they wound out of sight, hasted back to the poor victim. He was not then dead;--It was my father! It would be vain to attempt to describe our feelings, on the discovery of each other. My poor father appeared to be mortally wounded; the ball had broken his arm, and penetrated his side

Page 17

I staunched the bleeding as well as I could, and assisted him into the cave again. He had made himself a bed, and I laid him upon it. It appeared that he and a few others had been so severely wounded, when our village at Tamata was destroyed, that they could not be moved for two or three days. They were then-mounted on camels, and taken to the ship; my father was, however, in a different part from what I was; and when he was landed, he was immediately taken to the hospital till fit to be sold. He had been bought by the owner of a neighbouring plantation to ours, and had only been about two moons with the Negroes in the mountains, with whom he had met accidentally. He had been so reduced by his wounds, his journey, and his sufferings on board the ship, that he could scarely crawl at all: and when he attempted to work, he could not possibly keep up with others. The driver said that he was idle, and he was consequently flogged so often, and so severely, that he found his life such a burden, as that nothing could be worse. He therefore took the resolution to abscond, and one night, after dark, he left the plantation, with such provisions as he had been able to save for the purpose. He had made his remarks on the aspect of the country, and travelled, as well as he could, in the direction of the mountains. He had been three days wandering about them before he discovered the village. Since he had been there, he had recovered much strength, yet he was still so much reduced, that I did not know him, till he called me by my name, and claimed me for his son. It was a melancholy meeting. It was impossible that I could remove him in his then state, and I determined not to leave him while he lived. I had provisions with me for several days; and during two nights and days I watched and tended him. On the third morning he died. In the course of the day I dug his grave, and in the evening buried him.

I immediately set off on my return, for I was fully aware that poor Quahama must conclude that I was killed. I travelled all night, and in the morning, being much tired, was seated eating my breakfast in the shade of some trees, when, happening to raise my eyes. I saw three white men, about a hundred paces from me, with their guns pointed at me. I at once perceived my danger, and therefore did not offer to rise, but merely bowed my head, with my hands across my breast. They hesitated, and after looking carefully on all sides, they very slowly came towards me. I soon saw that they were come in search of me. They refused to listen to anything that I could say, but securing my arms, marched me along as a prisoner.

Page 18

When we got to the plantation I was taken before the overseer. It was in vain that I told the truth; the reward for taking a runaway negro was too tempting, and I was condemned, on their united testimony against me, to receive three hundred lashes, at three times--one hundred of them immediately. I was then taken to a large tree a little way from the overseer's house, and tied by a cord around my left wrist, to one of the lower branches, so that I could only touch the ground with my toes. In this position I received the first hundred lashes. I believe that I never cried out, though the infliction was as severe as could be bestowed, the executioner being one of my accusers. When I had endured about eighty lashes I became senseless. Of what followed, I know nothing, till I came to my recollection, and found myself in my own house, with the doctor standing by me, and Quahama and Mene weeping and kissing me. The doctor had dressed my back, and soon left us.

I could only press, and that slightly, the hands of my dear wife and child. A dangerous fever, which lasted several weeks, was the consequence of my flogging. My back was laid open in many places to the bone, and a mortification was apprehended. Being a stout slave, my death would have been a great loss, so that I had more than usual attention paid to me. Poor Quahama wept very much on hearing of the sufferings of my poor father, though she could not but rejoice at his release from them. Mene, meanwhile, improved very much, and became more and more like what her mother once was. She was now branded with the red-hot iron, the same as we had been, and went out regularly to work.

It was more than a month before I was at all able to work. The rest of my punishment was, however, remitted. When I recovered my strength I did not feel disposed to submit tamely to such manifest cruelty and injustice as I had experienced. I had heard, that a few miles off, there resided a Fiscal, to whom any Negro that had suffered injustice might apply for redress. My case was so clear that I felt no doubt of receiving protection. I therefore, as soon as I could walk so far, set off very early in the morning, and arrived at his house before he was up. On stating my business and case, he wrote something down, and sent the paper out. I was then taken into a dark room, and was told to wait there till I was sent for; indeed, I was forced to do so, as there appeared no way of getting out. In the afternoon I was called upon, and taken before the Fiscal; my accusers were with him. He then read to them what I had told him, and asked them if it was true. They told him that it was all false, and made out a case still more against me than even their first. This

Page 19

they offered to attest on oath, but he did not seem to think that at all necessary. I offered to confirm my statement on oath, but he asked me if I thought the oath of a Negro was to be attended to. He said that he found it was high time to put a stop to all such lying, complaining, black villains, or he might soon have no time to attend to anything else, and that he would take care that I had justice enough. He therefore made an order that I should receive (if it was found that I could bear them) another hundred lashes for making a false charge. This, I felt assured, must be the death of me, and had it not been for my wife and child, I should have been glad of it. The punishment, however, they never thought proper to inflict. I conceive they feared that it would either kill me or drive me away. The drivers, however, who were my accusers, took care from this time not to spare the lash to either myself or wife.

It was, I think, not more than two years after this, that my wife, being about to have an increase of family, and being very weak, was absolutely unable to continue her work upon her legs, so that most of the day she was on her hands and knees. This fatigued her so much, that one morning she could not get out of bed in time to begin with the rest. When at length she had crawled there, the driver ordered her to be thrown, and held down by the hands and feet, while he gave her twenty lashes on her bare body. This brought on premature labour. She was taken back, and was delivered of a dead child. When I was informed of it, and got to her, she seemed very near her end. Poor Mene was almost heart-broken; for myself, though agitated beyond measure, I could scarcely grieve. I saw that her pains and sorrows would soon be over. This was the case. We followed her corpse the next day to the grave.

My dear daughter was now my only remaining earthly comfort; and I had then no solid foundation on which to build any other. I had never named the name of Christ, nor ever heard of it, excepting once at the market, when a white man, whom I have since learned was a Christian missionary, was talking kindly to some of the Negroes; but I afterwards understood that the planters compelled him to leave the country. I could not very well tell what he said, nor did I at all comprehend his meaning, though I repeatedly heard the name of Jesus Christ repeated by him. I often thought of him afterwards, as he was the first white man I had ever then heard speak with kindness to Negroes.

Mene continued to grow still more like her poor mother; and was so attentive, and affectionate, and cheerful, that at times she made me almost forget my afflictions. She was now more than thirteen years of

Page 20

age, when, on returning one day from my work, I found her in the utmost distress. On inquiring into the cause, she told me that young massa had sent to tell her that she was to go to live with him. I was for a moment petrified with horror. We both too well knew what it meant, and too well knew the impossibility of any effective resistance. He was a debauched young man, and this was no uncommon occurrence. I did, indeed, now seem bereaved, and thought that my sorrows could not be aggravated. They, however, were so. In a little while poor Mene became very ill and dejected. Her complaint continually increased: it was the consequence of the young man's villainy, and yet he seemed to care little about it. Mene said that she should soon go to her mother; and she said the truth, for I followed her to the grave in about six moons from her being first taken from me.

I had now nobody in the world to care for but myself. I felt in some degree comforted by the reflection. My fears were much lessened, and I was not without hopes that I might not die in slavery. I began pretty fully to comprehend the relative nature and characters of the whites and the blacks. I saw clearly that one were the oppressors and the other the oppressed, without any inherent right to superiority in the one more than in the other. My strength by degrees in a great measure returned, and with it a proportionate degree of spirits. I had cultivated my little piece of land, that I had food enough. It may be supposed that I thirsted for revenge; but the fact is, and I have since been surprised at it, that I had no feelings of the kind. My thoughts were principally occupied in pondering on the subject of escape; at last I resolved to risk the experiment.

In the night preceding the market-day, or Sunday, as it was called, as my absence would not be then so much noticed, I took what provisions I thought necessary, and travelled, with all the despatch I could, towards the sea-coast, and arrived there before night. I remained there about five days without seeing a vessel of any kind, except at a very great distance. I now perceived one much nearer, sailing N.E.--that is leaving the port. The wind, though not high, was directly against her; and, in tacking, she came much nearer the shore than she intended. I could plainly see the men on board. The little wind there was died entirely away, and she lay like a helpless log on the water. I made up my mind at once, to attempt reaching her, and taking my chance of the consequence. There was some difficulty in getting clear of the breakers; but I soon overcame it. I swam till I came near enough to be heard, without having been discovered. I then called aloud. and by means of a rope

Page 21

thrown out for my aid, I was soon on board. I related my situation, and my determination to perish, rather than ever go back again, assuring them I would do all in my power to be useful, if they would take me with them, and give me victuals.

There was a gentleman on board, who knew by my mark to whom I belonged. He made very many particular enquiries of me, and I told him all the truth. He afterwards went with the captain below, and I remained seated on the deck. As soon as he was at liberty to attend to me, he told me that I must make myself as useful as I could, and he would consider what he could do in the case. I was fully aware that it was his intention to take me back again; but I conceived that many things might occur to frustrate that intention.

I was very much surprised and interested with everything I saw around me. I studied all parts of the vessel, and the method of regulating them, according to circumstances; at the same time I made a point of being particularly attentive to every one who gave me any orders, and by degrees I found I was becoming a favourite.

It happened that a lady, with a young child, was a passenger; she was standing with the child in her arms on a fine day, when the wind was rather high, looking down at part of a wreck that was floating past. At that moment a strong blast took off her bonnet; in the unconscious attempt to regain it, the child sprang, and fell from her arms. I was standing at the stern, when her screams and actions explained at once the accident. I instantly threw off my jacket and trowsers, and was in the sea before the child sunk. I saw it; it went down, and I followed it. I soon rose with it, but the vessel had got a considerable distance. The sea was rather rough, but I found no difficulty in keeping the little creature's head generally above water; for myself, I had no fears. I soon saw the boat approaching, and had presently the happiness of seeing the mother again in possession of her child.

As soon as I was dressed again, she came to thank me with tears. I cried too, for I had not been hardened to scenes such as this, as I had to those of misery. Even the little lovely baby appeared afterwards to take a liking to me.

The sailors all seemed willing to teach me anything; and I believe that, after a while, I understood the working of the ship as well as most of them. I was the most astonished with the compass, and felt much curiosity to discover the cause of the needle's always pointing to the north. This led me to wish much to learn to read, because I was told

Page 22

that I then might learn that and many other things. I often saw the captain and others reading; and when I could get hold of a book, I was never tired of examining and admiring it, though I could not conceive how it could possibly tell anything.

The lady whose child I had rescued, understanding my desire to learn to read, prevailed on a passenger, who had formerly been a schoolmaster, to teach me. I determined not to neglect my duty in the ship; but I employed every leisure moment, even to the almost neglect of meals, in studying the lessons and instructions which my teacher gave me. In a fortnight I could read enough to enable me fully to comprehend how books could speak. After that, my difficulties, as far as related to reading, were at an end, and I could very soon read any book, without much difficulty, but not yet with great facility.

Now it was that I was brought to reflect on religious subjects, for the lady had given me a New Testament I only understood that it was a book that was to teach me to do right and to be good. It is impossible to describe the interest which I often felt in reading it, or the feelings that it called forth. I became very inquisitive of the passenger who taught me to read about it, as to the time when these things happened, and if it was in any place, or country, to which we were going. He was a religious character, and gave me what information he could, and always seemed fond of talking on the subject. I was never tired of reading, and hearing, and thinking about it. I often wondered if Negroes were among the people whom Jesus Christ loved, and for whom he died.

We had now arrived nearly at the place of our destination (Liverpool). I will not attempt to describe my astonishment as we sailed up the river, and took our station in the docks, among hundreds of vessels, many of them larger than ours, which I had before considered as the wonder of the world. The immense buildings, and the perpetual bustle, almost bewildered my senses.

I knew not what was intended to be my lot, when almost every one was preparing to leave the ship; but before the lady before mentioned went, she came to me, accompanied by a gentleman who was come for her, the captain also being with them. She told me that it had been the captain's intention to have confined me below during his stay in port, but that she had engaged, in a penalty, for my not leaving the vessel, till I heard either from her or her husband, to whom she was going; that on my promising to do so, I might have my liberty in the vessel. This promise I readily made. The servant brought the child to

Page 23

take leave of me, and I was permitted to kiss it, as well as the lady's hand, which I did in tears.

I now took care to make myself as useful as I could on board, in assisting to unload the ship; and the captain and all the sailors were very kind to me. After a few days, the captain told me, that as he was sure I must want to see such a large and grand town, that I should that morning accompany him to several places to which he had to go. I certainly felt a great wish to do so, since it was probable I might never have another opportunity; but I recollected my promise to the lady, and told the captain that I dare not go. He looked at me attentively, and I thought I saw a tear; at last he condescended, before several of the men, to take my hand. "You are a noble fellow," said he; "you are going into better hands, or I would have provided for you myself." Here, sir," said he to a gentleman whom I had not before noticed, but who had heard what had passed, "take him, sir; I have had an eye to him during the whole voyage; and, if I know anything of mankind, he will be a faithful servant to you." The gentleman now stepped up to me, shook me heartily by the hand, thanked me for saving the life of his child, and for my attention to his wife. He told me that I was then free, as he should send back the price of my freedom by the captain, and, therefore, I might go where I liked; but that, if I would go and live with him, it would give his wife much pleasure, and that he should make it his study to render me comfortable.

It would occupy too much space to enter into any further detail of the history of this faithful Negro, which is so artlessly related by himself. Much as he had suffered, and numerous as were the vicissitudes which he had experienced, he was now only 34 years of age, and his constitution but little impaired, so that, with the good living and kindness he now experienced, his strength and activity had returned to him again. He had brought his New Testament with him from the ship, and always kept it with him. Through the kindness of his master and mistress, he was further instructed in religion; he had also leave to attend an evening school twice a week, and was instructed in writing and accounts. The progress he made satisfied all his friends.

"On the subject of Christianity," continues Zangara, "my heart was engaged, and my understanding convinced; and after becoming a Christian, nothing surprised me more than the lives which the professors of such a holy and pure religion live. I am very sure that my poor heathen brethren are less depraved than many professed Christians; and,

Page 24

were they converted to Christianity, there could be no comparison between them. In fact, I am persuaded that the heart of the poor untutored Negro affords one of the purest pages on which to inscribe the truths of that holy religion, for the reception of which, the hearts of too many Europeans seem to have no clean part. It is the evil lives of those who profess Christianity that is the great obstacle to the general reception of that pure faith by Negroes, wherever it is preached to them.

"My master very often gave me books to read on the subject of Negro Slavery. He was one who was very desirous of the Slaves being set free. Making Slaves of men must be a gross violation of the precepts of Christi anity, which directs us to do to others as we would have them do unto us. It has been at the request of my master and mistress (now that I have been ten years with them) that I have written this short unadorned history of my life.

"I may state, in conclusion, that in the interior of Africa, where the natives are total strangers to Europeans, wars are very rare; nearer the coast, wars may be more frequent, but it is probable that they almost all owe their origin, directly or indirectly, to the Slave Trade. I do not think the Negroes are either a blood-thirsty or a quarrelsome race. Where they have been corrupted by long intercourse with whites, their nature and habits, it is probable, may be greatly changed for the worse, having been taught much that is bad, and nothing that is good.

"Negroes, generally speaking, are easily to be wrought upon by kindness, and are particularly susceptible of gratitude. They certainly are not a blood-thirsty race. Me oppression which they experience, and the evil example of the generality of the Whites they come in contact with, debases and corrupts them. I feel no hesitation in affirming, that under kind and orderly masters, instead of enslavers, they would become the most obedient and mild race of servants that could any where be found together in equal numbers. Christianity, taught and practised among them in anything like purity, would be generally received with avidity. It is in a peculiar manner fitted for their disposition.

"Horrid as are the features of the Slave Trade and of Slavery," adds Zangara, "as pourtrayed in the life here presented to the public, it is by no means, in any one feature, exaggerated or caricatured. On the contrary, they are often more hideous than what has here appeared. It is utterly impossible for any human being, who has not been himself in the situation, to conceive anything like the sufferings experienced by the poor Slaves, on the passage, &c. They may, and no doubt do, vary in degree, but all are horrible."

Page 25

MAQUAMA,

THE DISCARDED NEGRO SLAVE.

SOME years ago, being present at a meeting at Kendal on the subject of Slavery, I accidentally happened to be there at the time, and having a few hours to spare, was induced to attend it. I committed the following account to writing the next day. It may therefore be depended upon as tolerably correct, though I much regretted that I was not at the time prepared to take the Negro's speech in short hand, as I might then have given it precisely in his own interesting language.

I arrived a little after the time appointed for the meeting; but business was not commenced, though I could perceive that some impatience began to be manifested. The Committee were on the platform, and earnestly engaged in conversation for some time, when a gentleman named Smith stepped forward, and thus addressed the meeting:--"Ladies and Gentlemen,--Mr. Rainsworth, who kindly undertook to prepare and read the report, took it with him to Ullesbank last evening. We have been anxiously expecting him this half hour, and are not without fears on his account, as his punctuality is so well known. However, as the time when the chair ought to be taken is expired, I have been requested by the committee to relate to you a circumstance which occurred to myself yesterday, and to introduce the strangers whom I then met with, to occupy your attention till either Mr. Rainsworth, or the messenger who is gone in search of him, shall be here. I am persuaded that your time will not be either misapplied, or seem tedious to you.

"I was walking by the side of Hurtlebeck, along the bottom of Stainfell, when I saw two persons picking their way down that steep and rugged hill-side. I was rather alarmed for them, and therefore stopped to watch their progress. If my attention was at first excited by their seeming peril, it was rivetted by their appearance on their nearer approach. One of them was an aged athletic man, of a commanding appearance: he was blind, and a Negro. The other was a fine boy, about

Page 26

ten years of age; he seemed 'Like Hesper, leading on the train of night.' A more lovely child I certainly never did see: his complexion was fair, but tanned with the weather, and ruddy: his light auburn locks curled, waving in the wind, for he was bare-headed: he carried a Bible under one arm, while the old Negro rested on his other shoulder. With the left hand, the old man supported himself by a staff. He had more of a beard than I ever saw a Negro have before. He had a scrip by his right side, suspended by a strap over his left shoulder. I stopped by the fall, till they had got down to the bottom of the hill. I addressed them; and finding that the aged Negro understood and spoke English well, I entered into conversation with him. As I learnt that they were strangers, I prevailed on them to favour me with their company for the night, and likewise to attend this meeting, as I am certain that the circumstances which Maquama (for such is the original name of my aged visitor) will be able to relate, will prove highly interesting; and perhaps it cannot be at a better time than while we are awaiting the arrival of our friend Mr. Rainsworth.

"I must, however, state, that Maquama has occasionally officiated in Jamaica, as an assistant to the Christian Missionaries. You will, therefore, find him better qualified to address you than you probably might otherwise have expected. With your leave, then, ladies and gentlemen, I will now introduce him. I thought it better, however, thus first to prepare you."

Mr. Smith now stepped into the committee-room, and soon returned, followed by the Negro and his little companion, The sight was exceedingly interesting and affecting, even more so than the relation of Mr. Smith had prepared us to expect. The meeting instinctively stood up in silent admiration; while the sweet little boy led the aged venerable Negro on to the platform. The contrast between the two was complete in every respect. The fine ruddy complexion, sparkling eyes, and artless, smiling, happy countenance of the little elastic-limbed boy, delighted every one; while the manly figure, black complexion, sightless eyes, and solemn countenance and deportment of the aged Negro, inspired us all with a kind of reverential awe. In walking, the old man stooped a good deal: but after Mr. Smith had whispered a few words to him respecting addressing the meeting, who now seated themselves, he raised himself upright, and appeared straight and majestic. He stood a few moments silent, to recollect himself; and then, in an unembarrassed manner, and in language easy to understand, with only sufficient of the Negro accent

Page 27

and peculiarity to render it more interesting, he addressed the meeting in something like the following terms, the utmost silence prevailing:--

"Christian Friends! for such, I am told, are all here present--and though I cannot see you, I can tell that there are many--I thank my God that I have been led to such an assembly. I am a poor old Negro, and have experienced and suffered many afflictions; but if those afflictions had been ten times greater than they have been, my present situation, and the events which have led me to it, together with the prospect which is now afforded me, of comfort to the poor Negro Slaves on earth, and of eternal happiness for myself, infinitely over-pay them all.

"Christian Friends! you are met together to serve the poor Negroes. Oh, may the God of mercies bless you all for so doing! Do not despise the heart-felt thanks of a poor, old, blind, Discarded Negro Slave. If he had more than these, and the tears of his sightless eyes, to give you, you should be welcome to them all. Yes, my Christian friends, I am sure that I can add to them the thanks of this dear fatherless boy, the child of a father, who fell a self-devoted victim to the same cause. We have been long inseparable, and I hope never to part from him till I am called upon to follow his father to the grave." The old man's tears trickled down his cheeks, as he laid his hand upon the head of the interesting boy, whose tears were not the only ones that accompanied those of Maquama.

"My kind friend, Mr. Smith," he continued, "informs me, that you would wish to hear something about Negroes, and the sufferings of Negro Slaves. I can tell you something about myself, which may, perhaps, answer the purpose. I was born in Africa, a very long way from the sea, but how far I cannot tell. The country was called Temaka. It was a very beautiful country, far more so than any that I have ever seen since. You cannot conceive what happy beings Negroes are in such a country, where they are out of the reach of Slave-makers. We there knew nothing of them. There is a liveliness in the Negro character, when unpolluted, that makes them always playful and happy. At least, on recollection, it seems to have been so in my youth. Our village was near the edge of an extensive lake. Around it, the ground was cultivated, beyond which, on one side, was a very large thick forest; on the other, the sandy desert came to within a very few miles. You must not, my Christian white friends, judge of the Negroes by such poor creatures as myself, worn down by Slavery. What would be, may I take the liberty to ask, most of the persons here present, had they been

Page 28