Autobiography of James L. Smith,

Including, Also,

Reminiscences of Slave Life,

Recollections of the War, Education of

Freedmen,

Causes of the Exodus, etc.:

Electronic Edition.

Smith, James Lindsay

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Chris Hill

Images scanned by

Chris Hill

Text encoded by

Lee Ann Morawski and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2000

ca. 280K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2000.

Source Description:

(title page) Autobiography of James L. Smith, Including, Also,

Reminiscences of Slave Life, Recollections of the War, Education of

Freedmen, Causes of the Exodus, Etc.

(cover) Autobiography of James L. Smith

James L. Smith

150 p., ill. 2

Norwich

Press of the Bulletin Company

1881

Call number 326.92 S651A (Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special

Collections Library, Duke University Libraries)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the

American South.

This electronic

edition has been created by Optical

Character Recognition (OCR). OCR-ed text has been compared against the

original document and corrected. The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar,

punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

All footnotes are

moved

to the end of paragraphs in which the reference

occurs.

All footnotes

are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as

--

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Smith, James Lindsay.

- African Americans -- Virginia -- Biography.

- African American clergy -- Connecticut -- Biography.

- African American Methodists -- Connecticut -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Virginia -- Biography.

- Fugitive slaves -- Connecticut -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Virginia -- Social life and customs -- 19th century.

- Slavery -- Virginia -- History -- 19th century.

- Plantation life -- Virginia -- History -- 19th century.

- Freedmen -- Education.

- United States -- History -- Civil War, 1861-1865 -- African Americans.

- Slaves' writings, American.

Revision History:

- 2000-10-24,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2000-07-11,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2000-07-10,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2000-06-29,

Chris Hill

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

[Cover Image]

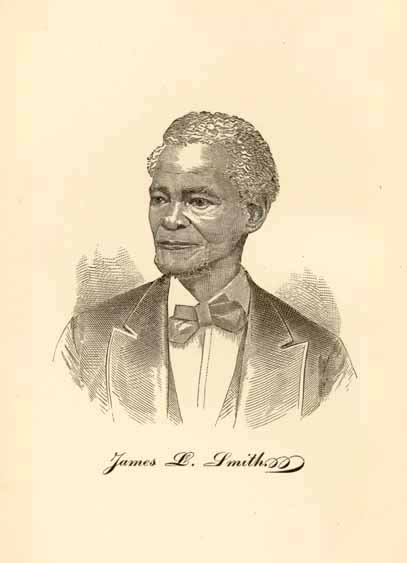

James L. Smith

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF

JAMES L. SMITH,

INCLUDING, ALSO,

REMINISCENCES OF SLAVE LIFE, RECOLLECTIONS

OF THE WAR, EDUCATION OF FREEDMEN,

CAUSES OF THE EXODUS, ETC.

NORWICH:

PRESS OF THE BULLETIN COMPANY.

1881.

Page verso

PRESS OF THE BULLETIN COMPANY.

1881.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1881,

By JAMES L. SMITH,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Page iii

TO THE MEMORY OF

MY FATHER,

CHARLES PAYNE,

WHO LIES IN A NAMELESS,

UNKNOWN GRAVE,

THIS VOLUME

IS DEDICATED.

Page v

PREFACE.

THE writer would bring before the public the narrative of his life while in bondage, which is substantially true in all its details. The painful wrongs inflicted then and now have caused the writer, though many years have passed, to take up the publication of this narrative of himself. There are many incidents and characters described in this narrative personally known to the writer, which make him anxious to put forth some effort, however humble it may be, to ameliorate the condition of his now suffering people, in order that the facts may confirm the truthful saying: "My people will be styled a nation yet, and also claim their nationality." For this they have fought and suffered hundreds of years in servitude and bondage. It is a fact which ought to thrill the heart of every American citizen to see the interest they take in learning; the untiring exertions they make to overcome every obstacle, even death itself to acquire it. It is what God has promised: "To be a God to the faithful and to their seed after them."

The writer hopes not to weary your patience in reviewing his narrative, which is fraught with so many exciting scenes. It is the duty of men to occupy places of power and trust, therefore our rulers, above all others, ought to be holy and devoted men[.] There are, however, some found in every age of the world who believe in freedom of thought and speech; and many who are untiring in their efforts to secure the future well-being of those intrusted to their care; it affords the most powerful argument to influence the

Page vi

minds of some. It is believed that no one who reads attentively, and reflects seriously, will doubt that the time is near at hand, which is spoken of by God: "Ye shall let my people go free." Now the great revolution seems to me to have come; now is the time for us to act in trying to save that which was lost; in stimulating them to education; and in building homes and schoolhouses for their children, that they may become honorable and respectable citizens of the States to which they have acceded. We want earnest laborers amongst us, for those who are instructing my people are few and far between; and we have been deprived of education by the hand of slavery and servitude, which has been brought upon us by the slave-holder. I feel it is the duty of the people to take up our cause, and instruct wherever they can.

Our ignorance, which is often spoken of, and for which we are not to blame, is caused by this ill, slavery; and the whipping post was resorted to if any attempt was made to learn the alphabet. I can say in the fullness of my heart that there is no darkness equal to this, not even the Egyptian darkness which is spoken of by missionaries now laboring in foreign lands. I only pray to hope on, and on, that God may appear in our behalf, and let the sun of civilization and education be extended among my people until it shall reach from sea to sea, and from land to land. Then shall Ethiopia stretch forth her hand unto God and call you blessed. I thank God for what I have seen and experienced so far in regard to the amelioration of our condition as a people. I hardly expect to see the completion of the act of liberty which was commenced by our most earnest friend, Senator Sumner. "See to the Civil Rights Bill; do n't let it fail," were among his last words to his associate who stood beside the dying senator.

This volume speaks of our earnest desire for more liberty and rights as a free people, and that our children may enjoy that of which we have been deprived. Never was the effectiveness of our Christian instrumentalities in other lands more dependent than now upon the vigorous and progressive development of Christian principles at home.

As we are entering upon a new decade our thoughts go back to 1861; and what a period is this to review! Could we have held

Page vii

the glass to our vision and seen what the nation would accomplish in its terrible struggle for existence, who would not have shrunk from the almost miraculous undertaking? But God had the blank years before Him, and as they passed, He proceeded to fill out the record. Nineteen years ago we were rocking in the swell of the gathering storm which was so soon and unexpectedly to break in its fury, and who could tell how many were to perish and go down ere its fury should be spent. In the strike which slavery made for the ascendancy, how little did we know through what terrible revulsions it would pass on its way to destruction. The cry was, "slavery must go down." How many mighty obstacles must fall before the march of the avalanche. How many disputed the question at the time, as to how this should be accomplished. But like the great iceberg when soft winds blow, and gentle rays fall on it, whether God would prostrate it as he does great cities when earthquakes rock them, was the question to be considered. Such was our uncertainty then; but these counsels were made known to us more speedily than we dreamed.

We have seen how the system of slavery was to be destroyed; and there is work for the Christian Church, there are responsibilities on Christian hearts which we did not anticipate nineteen years ago. National politics have brought about many incidental questions; but there is a period of new and aggressive work in which we are led to go forward and possess the land. Such a burden of duty as it bears upon us at this time, to remember that we are hourly approaching opportunities and responsibilities greater than we have hitherto known. In this spirit we have labored for the grand conquests which to-day are calling us onward. In this spirit we must toil now. How much we ask, bringing to you our pressing wants--come over and help us, for my people are in need of instruction, both spiritual and educational; and in thus aiding us you will accomplish a work of far reaching power, of which you have now no comprehension. "If God be for us, who can be against us?"

May this narrative awaken some to still greater earnestness in working for Christ, and freedom through the land. "Be not weary in well doing, for in due season ye shall reap if ye faint not." It

Page viii

is my privilege to speak about the impoverished people of the South, and those main pillars of our Republic, the Church and the School: thus following up the victories of our arms with the sublimer victories of Christian love. What tremendous agencies God has employed within these few years, and what He has caused to be exerted for all generations to come; and if there is one scripture which is most forcibly illustrated and impressed upon me than any other, it is this: "Whereas ye know not what shall be on the morrow." Who could have foreseen bow much God would bring to pass in these nineteen years? Could the author have held the glass to his vision, and seen what the nation would accomplish in its terrible struggle for existence, he would have despaired; but as the period has arrived, my people are determined to go forward and possess the land which will bring our children within the pale of intellectual training in the institutions of education and religion; for we all know that without this education we must expect to be defrauded of our homes, our earnings, and our lands. Many only make their mark in signing their names, for they cannot read or write.

This is the secret of their not having any thing to-day, and the responsibility rests on you, Christian people of these United States of America; and the cry is for help now. There is not a nation under heaven that needs more sympathy and pity from the people of the United States than my people; for they are maltreated every way in the higher educational schools, while endeavoring to obtain an education.

During the most eventful period in our history, the little stream of light that began to flow in Virginia and the Mississippi Valley has from year to year widened and deepened, and rolled with mighty healing power. It has passed the dividing mountains, and carried a flood of Divine blessings to many of my people. "But blessed are your eyes, for they see, and your ears, for they hear: for verily I say unto you, that many prophets and righteous men have desired to see these things which ye see, and have not seen them, and to hear these things which ye hear, and have not heard them." We still have hope of saving our beloved people, and of seeing prosperity in the future. Many of the colored people deserve

Page ix

much of this country for what they did and suffered in the great national struggle. When the Rebels appeared in their strength, and defeat followed defeat in quick succession, while the government was bleeding at every pore, and there appeared to be no help or power to save the Union, then our colored soldiers came to its timely aid and fought like brave men. The rebellion struck at the very heart of our country. Many of them were ill-treated by the Union soldiers--many a colored soldier was knocked down by them, and maltreated in every way. The treatment the colored soldiers received from the hands of the white soldiers was equal to slavery. All this was because the white soldiers did not want to stand side by side with them--did not want the negro in the ranks. Pen can not begin to describe the extreme sufferings of the colored men in this respect. The Yankee soldiers were eager for glory; the idea of having a colored man in the ranks caused many of them to be angry. "I will never die by the side of a nigger," was uttered from the lips of many.

I hope this work may find its way into the homes and hearts of those who are endeavoring still to help us in our efforts for liberty; if I succeed in this, it is all I desire. That I may have the prayers of all who are interested in my behalf, is the earnest desire of the writer.

In purchasing this narrative you will be assisting one who has been held in the chattels of slavery: who is now broken down by the infirmities of age, and asks your help to aid him in this, his means of support in his declining years.

Page xi

-

CHAPTER I.

BIRTH AND CHILDHOOD.

Birthplace--Parentage--Accident from disobedience--Sickness--Crippled for life--Death of master, and change of situation--Cecilia-- Jealousy, and attempt to take the life of my father by poisoning--Discovery and punishment--Removal to Northern Neck--Mode of living in old Virginia--Experiences of slave life--A cruel mistress--Work on plantation--Feigning sickness--Death of father and mother--Bound out to a trade--A brutal master, . . . . . 1 -

CHAPTER II.

YOUTH AND EARLY MANHOOD.

Cook on board a ship--A heartless master--An unsavory breakfast, and punishment--A difficult voyage--Tired of life, and attempt at suicide--Escape--Life on plantation--A successful ruse-- Removal to Heathsville, . . . . . 16 -

CHAPTER III.

LIFE IN HEATHSVILLE.

Hired out--Religious experience, conversion--Work as an exhorter--A slave prayer meeting--Over worked--A ludicrous accident--Love of dress--Love of freedom--Death of my master--Religious exercises forbidden--A stealthy meeting--The surprise--Fairfield Church--Quarterly meeting-- Nancy Merrill--A religious meeting and a deliverance--Sleeping at my post, . . . . . 25

Page xii -

CHAPTER IV.

ESCAPE FROM SLAVERY.

Change of master--Plans of escape--Fortune telling--Zip-- A lucky nap--Farewell--Beginning of the escape--A prosperous sail--Arrival at Frenchtown--Continuing on foot--Exhausted--Deserted by companions--Hesitating-- Terrible fright--A bold resolve and a hearty breakfast-- Re-union at New Castle--Passage to Philadelphia--A final farewell--Trouble and anxiety--A friend--Passage to New York, Hartford and Springfield--A warm welcome--Dr. Osgood, . . . . . 36 -

CHAPTER V.

LIFE IN FREEDOM.

Employment in a shoe shop--Education at Wilbraham-- Licensed to preach--John M. Brown--Mrs. Cecelia Platt --Elizabeth Osgood--Sabbath and Mission Schools--Return to Springfield--Engagement with Dr. Hudson--Experience at Saybrook--Persecutions of Abolitionists--Lecturing --Courtship and marriage, . . . . . 56 -

CHAPTER VI.

LIFE IN NORWICH, CONN.

Came to Norwich--Started business--Purchase a house-- Persecutions and difficulties--Ministerial labors--Church troubles-- Formation of a new Methodist Church--Retiring from ministerial work-- Amos B. Herring--Mary Humphreys--Sketches of life and customs in Africa, . . . . . 68 -

CHAPTER VII.

THE WAR OF THE REBELLION.

Desire to return to Virginia--Opening of the War--Disdain of the aid of colored men--Defeat--Progress of the War --Employing colored men--Emancipation Proclamation-- Celebration--Patriotism of Colored Soldiers--Bravery at Port Hudson--Close of the War--Death of Lincoln--A tribute to Senator Sumner--Passage of the Civil Rights Bill--Our Standard Bearers, . . . . . 77

Page xiii -

CHAPTER VIII.

AFTER THE WAR.

Fear of capture--A visit to Heathsville--Father Christmas, and a children's festival--Preaching at Washington--My first visit to my old home--Joy and rejoicing--Meeting my old mistress--My old cabin home--The old spring--Change of situations--The old doctor--Improvement in the condition of the colored people--Buying homes--Industry, . . . . . 90 -

CHAPTER IX.

CONCLUSION.

The Fifteenth Amendment Celebration--The parade--Address-- Collation--Charles L. Remond--Closing words, . . . . . 106 -

CHAPTER X.

COLORED MEN DURING THE WAR.

In battle--Kindness to Union men--Devotion to the Union--29th Conn.--Its departure--Return--The noble Kansas troops-- 54th Mass.--Obedience to orders, . . . . . 113 -

CHAPTER XI.

RECOLLECTIONS OF THE WAR.

The spirit of the South--Delaware--Kentucky--Meetings-- Conventions--Gen. Wild's raid--Slave heroism--A reminiscence of 1863--Sherman's march through Georgia--Arming the slave, . . . . . 127 -

CHAPTER XII.

THE EXODUS.

Arrival of negroes in Washington--Hospitality of Washington people-- Suffering and privation--Education of the freedmen--Causes of emigration--Cruelty at the South-- Prejudice at the North--Hopes for the future, . . . . . 140

CONTENTS.

Page xv

- JAMES L. SMITH, . . . . . Frontispiece

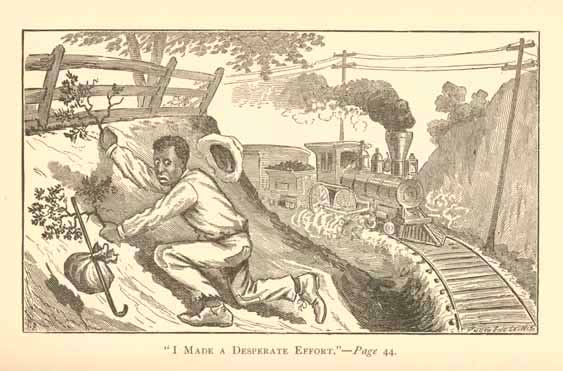

- "I MADE A DESPERATE EFFORT," . . . . . 44

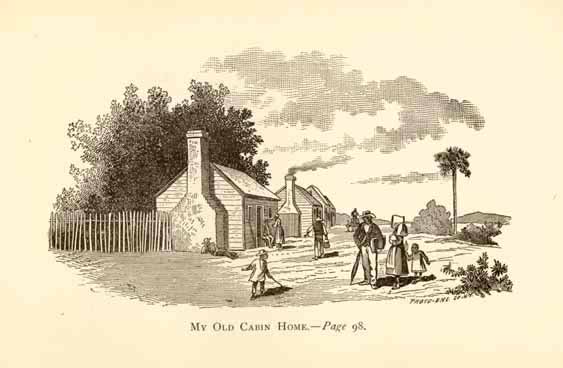

- MY OLD CABIN HOME, . . . . . 98

ILLUSTRATIONS.

Page 1

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF

JAMES L. SMITH.

CHAPTER I.

BIRTH AND CHILDHOOD.

Birthplace--Parentage--Accident from disobedience--Sickness--Crippled for life--Death of master, and change of situation--Cecilia--Jealousy, and attempt to take the life of my father by poisoning--Discovery and punishment--Removal to Northern Neck--Mode of living in old Virginia--Experiences of slave life--A cruel mistress--Work on plantation--Feigning sickness [--]Death of father and mother--Bound out to a trade--A brutal master.

MY birthplace was in Northern Neck, Northumberland County, Virginia. My mother's name was Rachel, and my father's was Charles. Our cabin home was just across the creek. This creek formed the head of the Wycomco River. Thomas Langsdon, my master, lived on one side of the creek, and my mother's family-- which was very large--on the opposite side. Every year a new comer was added to our humble cabin home, till she gave birth to the eleventh child. My mother had just so much cotton to spin every day as her stint. I lived here till I was quite a lad.

Page 2

There was a man who lived near us whose name was Haney, a coach maker by trade. He always had his timber brought up to the creek. One day he ordered one of his slave women to go down and bring up some of the timber. She took with her a small lad, about my size, to assist her. She came along by our cabin, as it was near the place where the timber was, and asked me to go along with her to help her. I asked mother if I could go. She decidedly said "No!" As my mother was sick, and confined to her bed at that time, I took this opportunity to steal away, unknown to her. We endeavored, at first, to carry a large piece of timber--the woman holding one end, I the other, and the boy in the middle. Before we had gone far her foot struck something that caused her to fall, so that it jarred my end, causing it to drop on my knee. The boy being in the middle, the full weight of the timber fell on his foot, crushing and mangling it in a most shocking manner. After this accident, the woman and boy started for home, carrying some smaller pieces of timber with them.

After a few days of painful sickness, mortification took place in the little boy's foot, and death claimed him for his own. My grandmother hearing my voice of distress came after me and brought me home. At the time she did not think I was hurt very seriously. My mother called me to her bedside and punished me for disobeying her. After a day or two my knee began to contract, to shrink. This caused my mother to feel that there was something very serious about it, and as soon as she was able to get around, she went to the "great house," the home of Thos. Langsdon, and told

Page 3

him that I was badly hurt, and that something must be done for me. He asked her what was the matter. She told him what had happened to me, and how seriously I was hurt with the timber. After hearing this sad news, he said he had niggers enough without me; I was not worth much any how, and he did not care if I did die. He positively declared that he should not employ a physician for me. As there was no medical remedy applied to my knee, it grew worse and worse until I could not touch my foot to the ground without the most intense pain. There was a doctor in the neighborhood at this time, and mother knowing it sent me to see him, unknowingly to my master. He examined my knee and said, as it had been out of joint so long it would be a difficult matter to break it over again and then set it. He told my mother to take me home and bathe it in cold spring water to prevent it from ulcerating, for if it should it would kill me.

When I was able to walk around with my lameness, Thomas Langsdon took me across the creek to his house to do chores. I was then quite a boy. After a while my leg commenced swelling, and after that ulcerating. It broke in seven places. I was flat on my back for seven or eight weeks before I could raise myself without help. I suffered every thing but death itself, and would have died if it had not been for Miss Ayers, who was house-keeper in the "great house." She came into the kitchen every day to dress my knee, till I could get around. Not having any shoes, and being exposed to the weather, I took a heavy cold which caused my knee to ulcerate. When I was able to get

Page 4

around, the father of my young master was taken sick, and was confined to his bed for months. I, with another boy about my size and age--six or seven years-- sat by his bedside. We took our turns alternately, the boy so many hours and I so many, to keep the flies off from him. After a while the old man died, then I was relieved from fighting or contending with flies.

After this I went across the creek to help my mother, as I was not large enough to be of any service on the plantation. In the course of time my young master died, also his wife, leaving two sons, Thomas and John Langsdon. My young master chose for us (slaves) a guardian, who hired us all out. As my mother gave birth to so many children, it made her not very profitable as a servant, and instead of being let out to the highest bidder, was let out to the lowest one that would support her for the least money. Hence my father, though a slave, agreed to take her and the children, and support them for so much money[.]

My father's master had a brother by the name of Thad. Guttridge, who lived in Lancaster County, who died, leaving his plantation to his brother, (my father's master). My father was then sent to take charge of this new plantation, and moved my mother and the children with him into the "great house;" my mother as mistress of the house.

This Thad. Guttridge had a woman by the name of Cecilia, or Cella, as she was called, whom he kept as house-keeper and mistress, by whom he had one child, a beautiful girl almost white. After this new arrangement was made for my father to take charge of the new plantation, this woman Cella, was turned out of

Page 5

her position as house-keeper to a field hand, to work on the plantation in exchange with my mother.

This was not very agreeable to Cella, so she sought or contrived some plan to avenge herself. So one Saturday night Cella went off, and did not return till Sunday night. When she did return she brought with her some whisky, in two bottles. She asked father if he would like to take a dram; and, not thinking there would be any trouble resulting from it, he replied: "Yes." Giving him the bottle, he took a drink. She then gave the other bottle to my mother, and she took a drink. Afterwards, Cella gave us children some out of the same bottle that my mother drank from. Father went to bed that night, complaining of not feeling very well. The next morning he was worse, and continued to grow worse until he was very low. His master was immediately sent for, who came in great haste. On his arrival he found father very low, not able to speak aloud. My master, seeing in what a critical condition he was, sent for a white doctor, who came, and gave father some medicine. He grew worse every time he took the medicine. There was an old colored doctor who lived some ten miles off. Some one told Bill Guttridge that he had better see him, and, perhaps he could tell what was the matter with my father. Bill Guttridge went to see this colored doctor.

The doctor looked at his cards, and told him that his Charles was poisoned, and even told him who did it, and her motive for doing it. Her intention was to get father and mother out of their place, so that she could get back again. Little did she think that the course she took would prove a failure. The doctor gave

Page 6

Guttridge a bottle of medicine, and told him to return in haste, and give father a dose of it. He did so. I saw him coming down the lane towards the house, at full speed. He jumped off his horse, took his saddle-bags and ran into the house. He called my mother to give him a cup, so he could pour out some of the medicine. He then raised my father up, and gave him some of it out of the cup. After he had laid him down, and replaced the covering over him again, he took his hickory cane and went out into the kitchen--Cella sat here with her work--with an oath told her: "You have poisoned my Charles." He had no sooner uttered these words, when he flew at her with his cane. As he was very much enraged, he commenced beating her over the head and shoulders till he had worn the cane out. After he had stopped beating her in this brutal manner her head was swollen or puffed to such size that it was impossible to recognize who she was; she did not look like the same woman. Not being satisfied with this punishment, he told her that he intended repeating it in the morning. In the morning, when he went to look for her, she was gone. He stayed with father till he was able to sit up. When he returned home--which was about ten miles--he left word with father that if Cella came home, to bind her and send her down to him.

This was in the fall of the year. Some months passed before we saw Cella again. The following spring, while the men were cleaning up the new land, Cella came to them; they took and brought her to the house. Father was then able to walk about the house, but was unable to work much. He had her tied, and

Page 7

put behind a man on horseback and carried down to his master, who took her and put her on board a vessel to be sent to Norfolk. He sold her to some one there. This was the last time we ever saw, or heard from her.

We lived here quite a number of years on Lancaster plantation. Finally my father's master sold it, and also his brother's daughter, Cella's child. We then returned from Lancaster plantation to Northern Neck, Va., and lived nearly in the same place, called Hog Point; we lived here quite a number of years. Mr. Dick Mitchell, my master's guardian, took me away from my mother to Lancaster County, on his plantation, where I lived about six months. I used to do chores about the house, and card rolls for the women. Being lame unfitted me for a field hand, so I had to do work about the house, to help the women.

Our dress was made of tow cloth; for the children, nothing was furnished them but a shirt; for the older ones, a pair of pantaloons or a gown, in addition, according to the sex. Besides these, in the winter season an overcoat, or a round jacket; a wool hat once in two or three years for the men, and a pair of coarse, brogan shoes once a year. We dwelt in log cabins, and on the bare ground. Wooden floors were an unknown luxury to the slave. There were neither furniture nor bedsteads of any description; our beds were collections of straw and old rags, thrown down in the corners; some were boxed in with boards, while others were old ticks filled with straw. All ideas of decency and refinement were, of course, out of the question.

Our mode of living in Virginia was not unlike all

Page 8

other slave states. At night, each slept rolled up in a coarse blanket; one partition, which was an old quilt or blanket, or something else that answered the purpose, was extended across the hut; wood partitions were unknown to the doomed slave. A water pail, a boiling pot, and a few gourds made up the furniture. When the corn had been ground in a hand-mill, and then boiled, the pot was swung from the fire and the children squatted around it, with oyster shells for spoons. Sweet potatoes, oysters and crabs varied the diet. Early in the morning the mothers went off to the fields in companies, while some women too old to do anything but wield a stick were left in charge of the strangely silent and quiet babies. The field hands having no time to prepare any thing for their morning meals, took up hastily a piece of hoe-cake and bacon, or any thing that was near at hand, and then, with rakes or hoes in the hand, hurried off to the fields at early dawn, for the loud horn called them to their labors. Heavy were their hearts as they daily traversed the long cotton rows. The overseer's whip took no note of aching hearts.

The allowance for the slave men for the week was a peck-and-a-half of corn meal, and two pounds of bacon. The women's allowance was a peck of meal, and from one pound-and-a-half to two pounds of bacon; and so much for each child, varying from one-half to a peck a week, and of bacon, from one-half to a pound a week. In order to make our allowance hold out, we went crabbing or fishing. In the winter season we used to go hunting nights, catching oysters, coons and possums. When I was home, the slaves

Page 9

used to bake their hoe-cakes on hoes; these hoes were larger than those used in the northern states. Another way for cooking them was to rake the ashes and then put the meal cake between the ashes and the fire--this was called ash pone; and still another way was to bake the bare cake in a Dutch oven, heated for the purpose--that was called oven pone. This latter way of baking them was much practiced, or customary at the home of the slave-holders.

The "great house," so called by the plantation hands, was the home where the master and his family lived. The kitchen was an apartment by itself in the yard, a little distance from the "great house," so as to face the front part of the house; others were built in the back yard. The kitchens had one bed-room attached to them.

One night I went crabbing, and was up most all night; a boy accompanied me. We caught a large mess of crabs, and took them home with us. The next day I had to card for one of the women to spin, and, being up all night, I could hardly keep my eyes open; every once in a while I would fall asleep. Mrs. Mitchell could look through her window into the kitchen, it being in front of the "great house." She placed herself in the portico, to see that I worked. When I fell into a quiet slumber she would halloo out and threaten to cowhide me; but, for all that, I could not keep awake. Seeing that I did not heed her threatenings, she took her rawhide and sewing and seated herself close by me, saying she would see if she could keep me awake. She asked me what was the matter; I told her I felt sick. (I was a great hand to

Page 10

feign sickness). She asked me what kind of sickness; I told her I had the stomach ache and could not work. Thinking that something did ail me, she sent Alfred, the slave boy, into the house after her medicine chest; she also told him to bring her the decanter of whisky. She then poured out a tumbler most full of whisky and then made me drink all of it. After drinking it I was worse than I was before, for I was so drunk I could not see what I was doing. Every once in a while when I fell asleep she would give me a cut with the rawhide. At last, night came and I was relieved from working so steady. When I was not carding I was obliged to knit; I disliked it very much; I was very slow; it used to take me two or three weeks to knit one stocking, and when I had finished it you could not tell what the color was.

I had also to drive the calves for the milk-woman to milk. One afternoon, towards night, I stopped my other work to hunt up the calves and have them at the cow-pen by the time the milk-woman came, with the cows; I went in one of the quarters, and being tired, I sat down on a bench, and before I knew it I fell asleep and slept till after dark. The milk-woman came with the cows, but there were no calves there. She hallooed for me, but I was not within hearing. As the cow-pen was not far from the "great house" the mistress heard her. At last the milk-woman came to the "great house" to see what had become of me, but no Lindsey could be found. She went to the kitchen where the milk pails were kept, took them, and then drove the calves up herself and went to milking. Before she had finished, I awoke and started for the kitchen for the

Page 11

pails. When I got there, Mrs. Mitchell was standing up in the middle of the kitchen floor. She asked me where I had been; I told her I fell asleep in the quarters' and forgot myself. She said she would learn me how to attend to my business, so she told Alfred to go into the "great house" and bring her the rawhide. I stood there trembling about mid-way of the floor. Taking the cow-hide, and lifting her large arms as high as she could, applied it to my back. The sharp twang of the rawhide, as it struck my shoulders, raised me from the floor.

Jinny (the cook) told me afterwards, that when Mrs. Mitchell struck me I jumped about four feet, and did not touch the floor again till I was out doors. She followed me to the door and just had time to see me turn the corner of the "great house." I then ran down towards the cow-pen. The cook told me the way I was running as I turned the corner, that she did not believe that there was a dog or horse on the plantation that could have caught me. I went to the cow-pen and helped the woman to finish milking, and stayed around till I thought that Mrs. Mitchell had gone into the "great house." But to my astonishment when I went to the kitchen again, behold, there she was still waiting for me. She asked me why I ran from her; I told her that it hurt me so bad when she struck me, that I did not know that I was running. She said the next time she whipped me that she would have me tied, then she guessed I would not run. She let me off that night by promising her that I would do better, and never run from her again.

Mrs. Mitchell was a very cruel woman; I have seen

Page 12

her whip Jinny in a very brutal manner. There was a large shade tree that stood in the yard; she would make Jinny come out under this tree, and strip her shoulders all bare; then she would apply the rawhide to her bare back until she had exhausted her own strength, and was obliged to call some of the house servants to bring her a chair. While she was resting, she would keep Jinny still standing. After resting her weary arms, she commenced again. Thus she whipped and rested, till she had applied fifty blows upon her suffering back. There was not a spot upon her naked back to lay a finger but there would be a gash, gushing forth the blood; every cut of the rawhide forced an extraordinary groan from the suffering victim; she then sent her back to the kitchen, with her back sore and bleeding, to her work. We slaves often talked the matter over amongst ourselves, and wondered why God suffered such a cruel woman to live. One night, as we were talking the matter over, Jinny exclaimed: "De Lord bless me, chile, I do not believe dat dat devil will ever die, but live to torment us."

After a while I left there for Hog Point, to live with my mother. In the course of a year or two old Mrs. Mitchell sickened, and died.

After she died, I went down to see the folks on the plantation. After my arrival, they told me that just before she breathed her last, she sent for Jinny to come to her bedroom. As she entered, she looked up and said: "Jinny, I am going to die, and I suppose you are glad of it." Jinny replied: "No, I am not." After pretending to cry, she came back to the kitchen and exclaimed: "Dat old devil is going to die, and I

Page 13

am glad of it." When her mistress died her poor back had a brief respite for a while. I do not know what took place upon the plantation after this.

As my young master became of age about this time, Mr. Mitchell gave the guardianship to him. During this time my mother died; then I was bound out to his uncle, John Langsdon, to learn the shoe-maker's trade. John Langsdon was a very kind man, and struck me but once the whole time I was with him in Fairfield, and then it was my own fault. One day, while I was at work in the shop, I put my work down and went out; while I was out, I stepped into the "great house." His two sons were in the house shelling corn; some words passed between his eldest son and me, which resulted in a fight. Mr. Langsdon was looking out of the shop window and saw us fighting; so he caught up a stick and struck me three or four times, and then drove me off to the shop to my work. I took hold of shoe-making very readily; I had not been there a great while when I could make a shoe, or a boot--this I acquired by untiring industry. He used to give me my stint, a pair, of shoes a day. I remained with him four years.

The first cruel act of my master, as soon as he became of age, and took his slaves home, was to sell one of my mother's children, whose name was Cella, who was carried off by a trader. We never saw or heard from her again. Oh! how it rent my mother's heart; although her heart was almost broken by grief and despair, she bore this shock in silent but bitter agony. Her countenance exhibited an anxious and sorrowful expression, and her manner gave evidence of a deep

Page 14

settled melancholy. This, and other troubles which she was compelled to pass through, and constant toil and exposure so shattered her physical frame that disease soon preyed upon her, that hastened her to the grave. Ah! I saw not the death-angel, as with white wings he approached. When the hour came for her departure from earth there was but a slight struggle, a faint gasp, and the freed spirit went to its final home. Gone where there were neither bonds nor tortures, sorrow and weeping are unknown.

My mother was buried in a field where there was no other dead deposited; no stone marks her resting place; no fragrant flowers adorn the sod that covers her silent house.

My father soon followed my mother to the grave; then we children were left fatherless and motherless in the cold world. My father's death was very much felt as a good servant, being quick and energetic, rendered him a favorite with his master. When my father was about to die, he called his children, those who were at home around him, as no medicine could now retard the steady approach of the death-angel. When we assembled about him he bade us all farewell, saying, there was but one thing that troubled him, and that was, not one of us professed religion. When I heard that, and saw his sunken eye and hollow cheek, my heart sank within me. Oh! how those words did cut me, like a two-edged sword. From that day I commenced to seek the Lord with all my heart, and never stopped till I found Him. After my father's death, my eldest sister took charge of the younger children, until her master took her home.

Page 15

One cold morning, while I lived at Hog Point, we looked out and saw three men coming towards the house. One was Mr. Haney, the other one was one of his neighbors, and the last one was his slave. Near our cabin home was a large oak tree; they took this doomed slave down to this tree, and stripped him entirely naked; then they threw a rope across a limb and tied him by his wrists, and drew him up so that his feet cleared the ground. They then applied the lash to his bare back till the blood streamed and reddened the ground underneath where he hung. After whipping him to their satisfaction, they took him down, and led him bound through our yard. I looked at him as he passed, and saw the great ridges in his back as the blood was pouring out of them, and it was as a dagger to my heart. They took him and forced him to work, with his back sore and bleeding. He came to our cabin, a night or two afterwards; my mother asked him what Mr. Haney beat him for; he said it was for nothing only because he did not work enough for him; he did all he could, but the unreasonable master demanded more. I never saw him any more, for shortly after this we moved away.

Page 16

CHAPTER II.

YOUTH AND EARLY MANHOOD.

Cook on board a ship--A heartless master--An unsavory breakfast, and punishment--A difficult voyage--Tired of life, and attempt at suicide--Escape--Life on plantation--A successful ruse-- Removal to Heathsville.

WHEN I lived at Mrs. Mitchell's there was a man who owned a vessel, who came there and took our grain. He told Mr. Mitchell he would like to take me and make a sailor of me. He liked the looks of my countenance very much, so they struck a bargain. The captain took me on board his vessel and made a cook of me. I stayed with him about two years, and most of the time he treated me very cruelly. He used to strip and whip me with the cat-o'-nine-tails. [This cat-o'-nine-tails was a rope having nine long ends and at each end a hard knot.]

One day as we lay at the dock in Richmond, Va., he rose very early one morning, and told me that he was going up town, advising me to have breakfast ready by the time he arrived. The weather was very cold. As it stormed that morning very hard, I asked him if I could cook down in the cabin. His reply was "No," and that I must cook in the caboose.

Page 17

[This caboose was a large black kettle set on the deck, all open to the weather, to make fire in, and supported by bricks to prevent it burning the deck.] Seeing I had to be reconciled to my situation, I made my fire the best I could. The rain and wind extinguished the fire, so that I could not fry the fish; hence I could not turn them, for they cleaved to the frying pan; so I thought I would stir them up in a mess and make poached fish of them; I then poured them out into a dish, and placed them on the table.

Very soon the captain came aboard drunk, and asked me if breakfast was ready; I told him: "Yes." When he went down into the cabin and sat at the table, I crept off and peeped through the cabin window, to see what effect the breakfast would have upon him. While he sat there, I beheld that he looked at the poached fish with a great deal of dissatisfaction and disgust. He called me "doctor," and commanded me to come down into the cabin. I replied promptly. When I got there, he pointed to the fish, and asked me if I could tell which parts of those fish belonged to each other; I told him I could not tell. As the cooking devolved on me that morning, I tried to justify myself by telling him that the rain and wind cooled my pan so that I could not fry the fish, and that I had done the best I could.

After hearing this, he told me to strip myself, and then go and stand on deck till he had eaten his breakfast. I suffered intensely with the cold. Some of the people on the dock laughed at me, while others pitied me. There I was, divested of my clothing! He turned his fiery eyes on me when he came on deck;

Page 18

and, with a look of fierce decision on his face, (for now all the fierceness of his nature was roused), he took a rope's end and applied it vigorously to my naked back until he deemed that I had atoned for my offence. The blows fell hard and fast, raising the skin at every stroke; by the time he was through whipping me I was warm enough. I then went down into the cabin to remove the breakfast things. I did not eat anything, for I had lost all appetite for food. In the course of the day we got under way, and started for home.

We then proceeded down the James River, and thence to a place called Carter's Creek. Here we took in a haul of oysters, and then started for Alexandria. The wind headed us off for several days, and the weather was very cold. At last the wind favored us, enabling us to continue our voyage till we arrived at Chesapeake Bay; just at this time the wind came in contact with our vessel and headed us off again. It was now in the stillness of the night (midnight) when the mate in the cabin was far under the influence of liquor; he was so beastly drunk that he could not get out to give any assistance whatever. Hence I had to manage the sails the best I could, while the captain stood at the helm. We strove all night endeavoring to get up the bay. About two o'clock in the morning the captain told me to bring up the jug of whisky to him. Just at this time the vessel sprung a leak. I did all I could to stop the leakage: the captain told me to go to the pump and do the best I could till morning. Both of us tried to get the mate out, but did not succeed. We then turned the vessel around and put back, reaching about day the place from whence we first

Page 19

started. By this time the mate was nearly over his drunken spell and was somewhat more sober, seeing what peril we were in, went with us to the pump to free the vessel. On account of the cold weather, we lay in Carter's Creek several days; our oysters spoiled and we were obliged to throw them overboard. We then took in a freight of merchandise and started for Fredericksburg; here we discharged our freight and returned, going down the Rappahannock we stopped to take in a freight of corn for Fredericksburg. One morning the captain and mate went ashore after a load of corn, leaving me on board to get breakfast and to have it ready by the time they returned. I had it ready as he requested. When they had nearly finished their meal the captain asked me for more tea; I told him it was all out; he wanted to know why I did not make more tea; I told him I thought there was a plenty, it was as much as I generally made. He challenged me for daring to think; he told me to go forward and divest myself of every article of clothing, and wait till he came. When he did come he put my head between his legs, and while I was in this position I thought my last days had come; I thought while he was using the cat-o'-nine-tails to my naked back, and hearing the whizzing of the rope, that if ever I got away I would throw myself overboard and put an end to my life. The captain had punished me so much that I was tired of life, for it became a burden to me.

The cat-o'-nine-tails had no rest, for so dearly did he love its music that a day seldom passed on which he could find no occasion for its use. On the impulse of the moment, I gave a sudden spring, and struck

Page 20

the water some distance from the vessel, and as I could not swim I began to sink. I found that unless I was helped soon I would drown. I began to repent of what I had done, and wished that I had not committed such a rash act. When I attempted to bring myself up to the surface of the water with success, I looked towards the vessel to see if the captain was coming to help me, and at this moment of my peril, instead of rendering any assistance he sat perfectly at ease, or composed on the deck looking at me, but making no effort to help me. I said to myself, I wonder if that old devil intends to let me drown, and not try to save me. All that I could do I was not able to keep myself on the surface of the water. Before I was out of reach and began to sink for the last time, I felt something grasp me; I found that it was the captain, who finally consented to draw me up to the surface of the water and throw me in the boat. I was so exhausted that I could neither stand up or sit down, but was obliged to lay on the bottom of the boat. While I was lying down he commenced beating me with the cat-o'nine-tails very unmercifully; the more he beat me, the more the water poured out of my mouth. The mate told me afterwards that the water flowing out of my mouth reminded him of a whale spouting water.

We then pursued our course to Fredericksburg; when reaching there we discharged our merchandise--the vessel made water very fast, so we returned to Carter's Creek to undergo repairs. Here it lay for a number of days, for the ship-carpenters were not ready to take care of her: hence I had to stay by the vessel while the captain and mate went home. After I had

Page 21

been there a few weeks, I sought an opportunity to run away. I saw a vessel one day going to my former home, Mr. Dick. Mitchell's, I got on board this vessel for home, having been gone for two years. I remained at this home about a year and did chores about the house while I did stay, and during the cotton season I had just so much cotton to pick out during the day,

One spring Mr. Mitchell put me in the field to attend to the crows, to prevent them pulling up the corn. This was three or four years before Mrs. Mitchell's death. This exercise did very well during the week days, but when the Sabbath day came I desired a respite from this monotonous work. The Sabbath day was a lonesome day to me, because the field hands were away that day; the boys would be away frolicking at some place they had chosen. I resolved that I would break up, or put an end to my Sunday employment; so I studied a plan, while I sat down in the field one Sabbath, how I should accomplish it. First, I thought I would feign sickness; then I said to myself, that will not do, for they will give me something that will physic me to death. My next contrivance was that I would pretend that I had the stomach ache; then, I said again, that will not do either, for then my mistress will make me drunk with whisky, as she had done before by her repeated doses. I devised another scheme, I thought the best of all, and that was to pretend that I had broken my leg again. As this plan was satisfactory to my mind, I arose from where I was sitting and resumed my work. Monday morning I turned to the field, as usual.

All at once I intentionally struck my foot against a

Page 22

stone. I made out that I had broken my leg again. When I came to the house, Jinny, the cook, saw me; her first exclamation was: "Why, chile, what is de matter?" In reply, I only gave a deep, mournful sound, and made a dreadful time about my leg, how it pained me, and so on. The cook, after looking pitifully at me, took my hand and helped me into the kitchen; while there I gave a sad account about my leg; I complained of feeling faint, and desired something to drink that I might feel better. She took a blanket into the adjoining room, and invited me to lie down on the floor. [This adjoining room was a little bedroom attached to the kitchen]. Every effort I made towards lying down I would groan piteously, and whimper as though it hurt me dreadfully. While I was on the floor Mr. Mitchell and the family were at breakfast in the "great house."

Alfred, the servant boy, carried the news to the family that I had broken my leg. As soon as Mr. Mitchell heard of this, he said, with an oath, that he would tend to it when he had eaten his breakfast. It was not long before I heard his speedy steps, as he was coming towards me; just this moment, I said to myself; this day it is either victory or death.

As he stepped into the kitchen he called out to Jinny, the cook, "Where is that one-legged son of a b--?" She replied that I was in the adjoining room, very badly hurt. He, with an awful oath, said that he would break my other leg. When he came into the bedroom where I was he sang out with a loud voice, and, with a dreadful oath, commanding me to rise, or else he would take every inch of skin off from my

Page 23

back. I told him that I was so much hurt that I could not get up. My complaints only vexed him the more, so much so that he told Alfred to go into the house and bring him the rawhide, and said that he would raise me.

By the time the boy had returned, I was up on one leg choking down the sobs now and then. Mr. Mitchell told me to take some corn and replant those hills I had allowed the crows to pull up. I took the corn and started to do my work, groaning and crying at every step; I did not get far before he called me back and asked me if I had eaten my breakfast; I told him I had not. As his passions had subsided, he told me to get my breakfast and then go out and plant the corn. I first went into the kitchen, and then to my room to lie down on the floor. Jinny came to me and asked me if I would have something to eat; I told her I was in too much pain to eat. (Just that moment I was so hungry that I could have eaten the flesh of a dead horse.) After Mrs. Mitchell had removed the breakfast things she came into the kitchen to see how I was, and found me groaning at a great rate, as if in great distress. She put her arm under my head to raise me, for I pretended that I was in so much pain that I could not raise myself.

Mrs. Mitchell was a very tyrannical woman, but notwithstanding her many failings she occasionally manifested a little kindness. She rolled up my pantaloons and commenced bathing my knee with opodeldoc (a saponaceous camphorated liniment) that she used for such purposes; after which she bound it up nicely and then laid me down again. Mr. Mitchell never came after me any more. Mrs. Mitchell rebuked her husband

Page 24

by telling him that he had no business to send me out in the field among the stumps to attend to the crows, for I was not able to be there.

I lay on the floor in my room about two weeks. In the course of the afternoon Jinny came into my room and asked me if I would have something to eat; I told her I would try and eat a little something, (just then I was hungry enough to eat a peck). When she returned with some bacon and corn-cake, (meal cake) I did not dare to eat much for fear that the rest of the family would mistrust that I was not sick. At the end of two weeks I asked one of the field hands if the crows had stopped coming to trouble the corn, his reply was, "yes, it was so, for the cherries were getting ripe and they were eating them instead." After hearing this joyful news I began to grow better very fast. The first day I sat up nearly all day; the next day I was able to go out some. When Saturday came I could walk quite a distance to see my mother, who lived some ten miles off.

Being lame, I was not very profitable on the plantation, so I went back to live with my mother till she died. At this time my eldest sister kept house for my father till the younger children were old enough to be hired out. My young master had become of age, and had his slaves divided between himself and his brother, each taking his half. It was at this time that my young master took me and put me in charge, or intrusted me to the care of his uncle, in Fairfield, to learn the shoe-maker's trade. I served four years, during which time my father died. After I had learned my trade, my master took me home and opened a shop in Heathsville, Va., placing me in it.

Page 25

CHAPTER III.

LIFE IN HEATHSVILLE.

Hired out--Religious experience, conversion--Work as an exhorter-- A slave prayer meeting--Over worked--A ludicrous accident--Love of dress--Love of freedom--Death of my master--Religious exercises forbidden--A stealthy meeting--The surprise--Fairfield Church--Quarterly meeting-- Nancy Merrill--A religious meeting and a deliverance--Sleeping at my post.

I RAN the shop for one year, during which time my young master became jealous of me. He thought I was making more money for myself than for him; it was not so, he was mistaken about it. What little I did earn for myself was justly my own. While I was away enjoying myself one Christmas day, he took an ox-cart with my brother, for Heathsville. The driving devolved on my brother. My master carried off my tools and every thing that was in the shop; he hired me out to a man who was considered by every one to be the worst one in Heathsville, whose name was Mr. Lacky, advising him "to keep me very strict, for I was knowing most too much." I lived with him three years, and managed so as to escape the cowhide all the time I was there, saving once. I strove by my prudence and correctness of demeanor

Page 26

to avoid exciting his evil passions. While learning the shoemaker's trade, I was about eighteen years old. At this time I became deeply interested in my soul's salvation; the white people held a prayer meeting in Fairfield one evening in a private house; I attended the meeting that evening, but was not permitted to go in the same room, but only allowed to go in an adjoining room. While there I found peace in believing, and in this happy state of mind I went home rejoicing and praising the Lord for what he had done for me. A few Sabbath's following, I united with the Church in Fairfield. Soon after I was converted I commenced holding meetings among the people, and it was not long before my fame began to spread as an exhorter. I was very zealous, so much so that I used to hold meetings all night, especially if there were any concerned about their immortal soul.

I remember in one instance that having quit work about sundown on a Saturday evening, I prepared to go ten miles to hold a prayer meeting at Sister Gould's. Quite a number assembled in the little cabin, and we continued to sing and pray till daybreak, when it broke. All went to their homes, and I got about an hour's rest while Sister Gould was preparing breakfast. Having partaken of the meal, she, her daughter and myself set out to hold another meeting two miles further; this lasted till about five o'clock, when we returned. Then I had to walk back ten miles to my home, making in all twenty-four miles that day. How I ever did it, lame as I was, I cannot tell, but I was so zealous in the work that I did not mind going any distance to attend a prayer meeting. I actually walked

Page 27

a greater part of the distance fast asleep; I knew the road pretty well. There used to be a great many run-aways in that section, and they would hide away in the woods and swamps, and if they found a person alone as I was, they would spring out at them and rob them. As this thought came into my head during my lonely walk, thinks I, it won't do for me to go to sleep, and I began to look about me for some weapon of defence; I took my jackknife from my pocket and opened it; now I am ready to stab the first one that tackles me, I said; but try as I would, I commenced to nod, nod, till I was fast asleep again. The long walk and the exertion of carrying on the meeting had nearly used me up.

The way in which we worshiped is almost indescribable. The singing was accompanied by a certain ecstasy of motion, clapping of hands, tossing of heads, which would continue without cessation about half an hour; one would lead off in a kind of recitative style, others joining in the chorus. The old house partook of the ecstasy; it rang with their jubilant shouts, and shook in all its joints. It is not to be wondered at that I fell asleep, for when I awoke I found I had lost my knife, and the fact that I would now have to depend on my own muscle, kept me awake till I had reached the neighborhood of my home. There was a lane about half a mile from the house, on each side of which was a ditch to drain the road, and was nearly half full of water; as I neared this lane I fell asleep again, as the first thing I knew I was in the ditch; I had walked right off into it, best clothes and all. Such a paddling to get out you never saw. I was wide

Page 28

awake enough now you may rest assured, and went into the house sick enough; my feet were all swollen, and I was laid up for two or three clays. My mistress came in to see me, and said I must have medicine. I had to bear it, and she dosed me well.

As soon as I was able, I went to work. I had a shop all to myself. My master lived five miles away, but would come once a week and take all the earnings; some weeks I would make a great deal, then I would keep some back for myself, as I had worked for it. In this way I saved at one time fifteen dollars; I went to the store, bought a piece of cloth, carried it to the tailor and had a suit made--I had already bought a watch, and had a chain and seal. You can imagine how I looked the following Sunday; I was very proud and loved to dress well, and all the young people used to make a great time over me; it was Brother Payne here, and Brother Payne there; in fact, I was nearly everywhere.

The other slaves were obliged to be on the plantation when the horn blew, at daybreak, but sometimes I did not get home till twelve o'clock; sometimes it would be night, and I always escaped a whipping. The first Sunday that I was arrayed in my new suit, I was passing the court house bounds, when I saw my master and a man named Betts standing near by. Betts caught sight of me; says he: "Lindsey, come here." Not knowing what he wanted, I went to him; whereupon he commenced looking first at me, then at my master; then at my master, then at me; finally he said: "Who is master; Lindsey or you, for he dresses better than you do? Does he own you, or do you own him?"

Page 29

From a child I had always felt that I wanted to be free. I could not bear the thought of belonging to any one, and so when I ran away, my mind was made up all in a sudden. My master came as far as Philadelphia to look for me; and, my brother says, when he came back without me, he became a very demon on the plantation, cutting and slashing, cursing and swearing at the slaves till there was no living with him. He seemed to be out of his head; and for hours would set looking straight into the fire; when spoken to, he would say: "I can't think what made Lindsey leave me."

One day he ordered my brother and a man named Daniel to move the barn from where it set further out to one side. So my brother went to work, with two or three others, and had raised it about three or four feet, when something gave way; and, as they were under the barn, they all ran out. My master seeing this became furious. "How dare you to run? You shall stay under there, if you get crushed to pieces!" So saying, he went into the house and got the rawhide. "Now," says he, "the first one who runs, I'll cut to pieces." He then took his place inside the barn, and commanded them to go on with their work, while he looked on.

They began to turn the screw, when some timber from above fell right across the door, completely blockading it. Master was shut up in the barn, and it was impossible for him to get out. Why he did not jump out, when the creaking sound gave him warning, no one can tell; he seemed to sit back there, in a dazed sort of a way. There was a rush to rescue him, and he

Page 30

was found all mangled and bruised, with the rawhide grasped tightly in his hand. My brother says he only gasped once or twice after he was brought out.

When Nat. Turner's insurrection broke out, the colored people were forbidden to hold meetings among themselves. Nat. Turner was one of the slaves who had quite a large army; he was the captain to free his race. Notwithstanding our difficulties, we used to steal away to some of the quarters to have our meetings. One Sabbath I went on a plantation about five miles off, where a slave woman had lost a child the day before, and as it was to be buried that day, we went to the "great house" to get permission from the master if we could have the funeral then. He sent back word for us to bury the child without any funeral services. The child was deposited in the ground, and that night we went off nearly a mile to a lonely cabin on Griffin Furshee's plantation, where we assembled about fifty or seventy of us in number; we were so happy that we had to give vent to the feelings of our hearts, and were making more noise than we realized. The master, whose name was Griffin Furshee, had gone to bed, and being awakened by the noise, took his cane and his servant boy and came where the sound directed him. While I was exhorting, all at once the door opened and behold there he stood, with his white face looking in upon us. As soon as I saw the face I stopped suddenly, without even waiting to say amen.

The people were very much frightened; with throbbing hearts some of them went up the log chimney, others broke out through the back door, while a few, who were more self-composed, stood their ground.

Page 31

When the master came in, he wanted to know what we were doing there, and asked me if I knew that it was against the law for niggers to hold meetings. I expected every moment that he would fly at me with his cane; he did not, but only threatened to report me to my master. He soon left us to ourselves, and this was the last time be disturbed us in our meetings. His object in interrupting us was to find out whether we were plotting some scheme to raise an insurrection among the people. Before this, the white people held a quarterly meeting in the Fairfield Church, commencing Saturday, and continuing eight days and nights without cessation.

The religious excitement that existed at that time was so great that the people did not leave the church for their meals, but had them brought to them. There were many souls converted. The colored people attended every night. The white people occupied the part next to the altar, while the colored people took the part assigned them next to the door, where they held a protracted meeting among themselves. Sometimes, while we were praying, the white people would be singing, and when we were singing they would be praying; each gave full vent to their feelings, yet there was no discord or interruption with the two services. On Wednesday night, the fourth day from the commencement of the meeting, a colored woman by the name of Nancy Merrill, was converted, and when she experienced a change of heart she shouted aloud, rejoicing in the richness of her new found hope. Thursday night, the next evening, the meeting still continued.

By this time the excitement was on the increase

Page 32

among both parties, and it bid fair to hold eight days longer; but right in the midst of the excitement some one came to the door of the church and nodded to the sexton to come to the door; as soon as he did go to the door some one there told him to speak to Nancy Merrill, the new convert, and tell her to come to the door, for he wanted to speak to her. She went, and, behold it was a slave trader, who had bought her during the day from her mistress! As soon as she went to the door, he seized and bound her, and then took her off to her cabin home to get her two boys he had bought also. The sexton came back and reported to us what had taken place.

This thrilling and shocking news sent a sharp shiver through every heart; it went through the church like wild-fire; it broke up the meeting entirely among both parties; in less than half an hour every one left the church for home. This woman had a daughter in Fairfield, where I learned my trade, and I hastened home, as soon as possible, to tell the girl what had happened to her mother. She was standing by the fire in the kitchen as I entered--she was the servant girl of John Langsdon, the man who taught me the shoemaker's trade. As soon as I related to her this sad news she fell to the floor as though she had been shot by a pistol; and, as soon as she had recovered a little from the shock we started for her mother's cabin home, reaching there just in time to see her mother and her two brothers take the vessel for Norfolk, to be sold. This was the last time we ever saw her; we heard, sometime afterwards, that a kind master had bought her and that she was doing well.

Page 33

Many thrilling scenes I could relate, if necessary, that makes my blood curdle in my veins while I write. We were treated like cattle, subject to the slave-holders' brutal treatment and law.

The wretched condition of the male slave is bad enough; but that of the woman, driven to unremitting, unrequited toil, suffering, sick, and bearing the peculiar burdens of her own sex, unpitied, not assisted, as well as the toils which belong to another, must arouse the spirit of sympathy in every heart not dead to all feeling. Oh! how many heart-rending prayers I have heard ascend up to the throne of grace for deliverance from such exhibitions of barbarity. How many family ties have been broken by the cruel hand of slavery. The priceless store of pleasures, and the associations connected with home were unknown to the doomed slaves, for in an unlooked for hour they were sold to be separated from father and mother, brothers and sisters. Oh! how many such partings have rent many a heart, causing it to bleed as it were, and crushing out all hope of ever seeing slavery abolished.

Sometime before I left for the north, the land of

freedom, I appointed another meeting in an off house

on a plantation not far from Heathsville, where a number

of us collected together to sing and pray. After I

had given out the hymn, and prayed, I commenced to

exhort the people. While I did so I became very

warm and zealous in the work, and perhaps made more

noise than we were aware of. The patrolers*

*The patrolers were southern spies, sent out, or were wont to roam at night to hunt up runaway slaves, and to investigate other matters.

going along the road, about half a mile off, heard the sound

Page 34

and followed it where we were holding our meeting. They came, armed to the teeth, and surrounded the house. The captain of the company came in, and as soon as we saw him we fell on our knees and prayed that God might deliver us. While we prayed he stood there in the middle of the floor, without saying a word. Pretty soon we saw that his knees began to tremble, for it was too hot for him, so he turned and went out. His comrades asked him if "he was going to make an arrest;" he said "no, it was too hot there for him." They soon left, and that was the last we saw of them.

As God had delivered us in such a powerful manner, we took courage and held our meeting until day-break. Another time I had a meeting appointed at a freedwoman's house, whose name was Sister Gouldman, about five miles in the country. I left home about seven o'clock on Saturday evening, and arrived there about ten; we immediately commenced the meeting and continued it till about daylight. After closing the meeting we slept while Sister Gouldman was preparing the breakfast. After breakfast we went two miles further, and held another meeting till late in the afternoon, then closed and started for home, reaching there some time during the night. I was very much fatigued, and my energies were entirely exhausted, so much so that I was not able to work the next day.

The time when I was eighteen years old, when such a miraculous change had been wrought in my heart, I had had two holidays, and was up all night holding meetings, praying and singing most of the time. Not having any sleep, I could scarcely keep my eyes open when I went to work. While endeavoring to finish a

Page 35

piece of work, Mr. Lacky came and found me asleep while I was on my bench shoe-making. He told me that I had been away enjoying myself for two days, "and if he should come again and find me asleep, he would wake me up." Sure enough, he had no sooner left the shop when I was fast asleep again. As his shop was beneath mine, he could easily hear me when I was at work. He came up again in his stocking-feet, unawares, and the first thing I knew he had the rawhide, applying it vigorously to my flesh in such a manner that did not feel very pleasant to me. After punishing me, he asked me "if I thought I could keep awake after this." I told him "I thought possibly I could," and did, through a great deal of effort till night. I never was satisfied about that whipping.

Page 36

CHAPTER IV.

ESCAPE FROM SLAVERY.

Change of master--Plans of escape--Fortune telling--Zip--A lucky nan--Farewell--Beginning of the escape--A prosperous sail-- Arrival at Frenchtown--Continuing on foot--Exhausted--Deserted by companions--Hesitating-- Terrible fright--A bold resolve and a hearty breakfast--Re-union at New Castle--Passage to Philadelphia--A final farewell--Trouble and anxiety--A friend--Passage to New York, Hartford and Springfield--A warm welcome--Dr. Osgood.

NEAR the end of the third year I went to my young master and told him I did not care about living with Mr. Lacky any longer. He told me that I could choose for myself another man whom I could live with. I concluded to live with one by the name of Bailey, who did not strike me during the year, but threatened to, which made me mad. About the end of this time I thought very strongly in reference to freedom, liberty; the precious goal which I almost grasped. I pursued daily my humble duties, waiting with patience till I could perceive some opening in the dense dark cloud that enveloped my fate in the hidden future. Before I lived with Bailey, I had some thoughts of this. I became acquainted with a man by the name of Zip, who was a sailor; I told him my

Page 37

object in reference to freedom. He told me that he also was intending to make his escape and to have his freedom. This was in the year 1836. We agreed that whenever there was a chance we would come off together. About Christmas, 1837, we made an arrangement to run away. Zip was calculating to take the vessel that the white people had left during their absence. He was left to take care of this vessel till they returned; nevertheless he intended to use it to a good purpose, for he took this opportunity to make his escape. We intended to carry off seventy, but we were disappointed because we could not carry out our arrangements. It was a very cold Christmas Eve, so much so that the river was badly frozen, not making it favorable for us to capture her: hence we gave that project up until the spring of 1838.

On the 6th day of May, 1838, Zip, with another one by the name of Lorenzo and myself, each hired a horse to take a short journey up the country to Lancaster, to see a sick friend of ours, who was very ill, for we did not expect to see him again. His name was Lewis Vollin. We had calculated to make our escape in about two weeks; so we started one Sabbath morning and found our friend quite sick, and was only able to sit up a little while and talk with us. Lewis' doctor was an aged colored man, who was a fortuneteller also, and could unfold the past, present, and future destiny of any one. Our sick friend was at this doctor's home, for the purpose of being cured by him. While there, the doctor asked us to walk out and look at his place; we did so, and after a while we sat down under a large tree. The

Page 38

doctor then asked us if we would like to have our fortune's told; we told him "yes." He sent to the house for his cards, and after receiving them, told each of us to cut them; we did so, then he took my cut and looked it over, saying, "you are going to run away; I see that you will have good luck; you will go clear: you will reach the free country in safety; you will gather many friends around you, both white and colored; you will be worth property, and in the course of time will return back home, and walk over your native land." I asked him "how that could be; was I to be captured and brought back?" He said "no, you will come back because you wish to, and go away again." I told him "that was something that I did not understand." He said, "nevertheless, it is so."

He then told the fortunes of my two companions, Zip and Lorenzo. He examined their cuts, and said they would all go clear; but never said they would return, neither did they, for they died before freedom was proclaimed. Zip died at the West Indies, Lorenzo died on the ship in some port at the time the cholera broke out.

In the afternoon we started for home, reaching there about four o'clock. When we reached Heathsville, the place where we lived, we noticed as we rode up to the stable to put the horses away, (for we were on horse-back) that there were half a dozen or more young men, who appeared to be talking and whittling behind the stable. The stable where I put my horse was on one side of the street, and the stable where Zip was to put his was on the opposite side. Zip went up to the door to put his horse in, but found that it would

Page 39