Narrative of Joanna;

An Emancipated Slave, of Surinam.

(From Stedman's Narrative of a Five Year's Expedition

Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam):

Electronic Edition.

Stedman, Gabriel John, 1744-1797

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Ellen Decker and Natalia Smith

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Lee Ann Morawski and Natalia Smith

First edition, 2001

ca. 95K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2001.

Source Description:

(title page) Narrative of Joanna; An Emancipated Slave, of Surinam.

(From Stedman's Narrative of a Five Year's Expedition Against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam)

64, [8] p., ill.

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY ISAAC KNAPP, 25, Cornhill.

1838

Call number HT869.J62 S73 1838 (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been encoded using the

recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

The publisher's advertisements following p. 65 have been scanned as images.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

Languages Used:

- English

LC Subject Headings:

- Stedman, John Gabriel, 1744-1797.

- Joanna, 18th century.

- Soldiers -- Suriname -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Suriname -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Emancipation -- Suriname.

- Blacks -- Suriname -- Biography.

- Slavery -- Suriname.

- Miscegenation.

Revision History:

- 2003-11-13,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2001-02-25,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2001-02-23,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 2001-01-31,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing and proofing.

JOANNA.

NARRATIVE

OF

JOANNA;

AN EMANCIPATED SLAVE,

OF SURINAM.

[From Stedman's Narrative of a Five Year's Expedition

against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam.]

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY ISAAC KNAPP,

25, Cornhill.

1838.

Page 3

[THE following story is found scattered here and there through the pages of a large and painfully interesting work, called 'Narrative of a Five Years' Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam: By Captain John G. Stedman.'

The author was an Englishman, who partly from a love of seeing new countries, and partly from ambition, entered the Dutch service, and went out to protect the Colony of Surinam from the incursions of what he calls REBEL NEGROES; being in fact an independent republic of colored citizens, daily augmented in numbers by runaway slaves.

He is the hero of his own story; and I leave him to tell it in his own words. Should any fastidious readers be alarmed, I beg leave to assure them that the Abolitionists have no wish to induce any one to marry a mulatto, even should their lives be saved by such an one ten times.--EDITOR.]

Page 5

JOANNA.

'I first saw Joanna at the house of a Mr. Demelly, where I daily breakfasted. She was about fifteen years of age, and a remarkable favorite with his lady. Rather taller than the middle size, she had the most elegant shape nature can exhibit, and moved her well formed limbs with unusual gracefulness. Her face was full of native modesty, and the most distinguished sweetness. Her eyes, as black as ebony, were large, and full of expression, bespeaking the goodness of her heart. A beautiful tinge of vermillion glowed through her dark cheeks, when she was gazed upon. Her nose was perfectly well formed, and rather small. Her lips, a little prominent, discovered, when she spoke, two regular rows of teeth as white as mountain snow. Her hair was dark brown,

Page 6

inclining to black, forming a beautiful globe of small ringlets, ornamented with flowers and gold spangles. Round her neck, arms, and ancles, she wore gold chains, rings and medals. A shawl of India muslin was thrown negligently over her polished shoulders; and a skirt of rich chintz completed her apparel. In her delicate hand she carried a beaver hat, ornamented with a band of silver. The figure and appearance of this charming creature could not but attract my particular attention; as they did, indeed, that of all who beheld her. With much surprise, I inquired of Mrs. Demelly who this girl was, that appeared so much distinguished above others of her color in the colony.

'The lady replied, 'she is, sir, the daughter of a highly respectable gentleman, named Kruythoff. He had five children by a black woman, called Cery, the slave of a Mr. D. B. on his estate Fauconberg.

"'A few years since, Mr. Kruythoff offered more than a thousand pounds sterling to Mr. D. B., to obtain manumission for his offspring. This being inhumanly refused, it had such an effect upon his spirits that he became frantic, and died in that melancholy state soon after; leaving in slavery, at the

Page 7

discretion of a tyrant, two boys, and three fine girls, of which the one before us is the eldest. The gold ornaments which seem to surprise you, are the gift of her faithful mother, who is a most deserving woman, and of some consequence among her caste. She attended Mr. Kruythoff to the last moment, with the most exemplary affection; and she received the gold ornaments in token of gratitude from him, a short time before he expired. Since that time, Mr. D. B. has driven all his best negroes to the woods, by his injustice and severity. He has been obliged to fly the colony, leaving his estate and stock to the disposal of his creditors. One of the slaves, who escaped from him and joined the rebel negroes, has by his industry, been able to protect Cery and her children. He is a samboe,* * A samboe is the offspring of a mulatto and a negro.

and his name is Jolycoeur. He has become the first of Baron's captains; and you may chance to meet him in the rebel camp, breathing revenge against the Christians. Mrs. D. B. is still in Surinam, being arrested for her husband's debts, till Fauconberg shall be sold by execution to pay them. This lady now lodges at my house,

Page 8

attended by the unfortunate Joanna, whom she treats with peculiar tenderness and distinction.'

"The tears glistened in Joanna's eyes, during this recital. Having thanked Mrs. Demelly, I returned to my lodging in a state of sadness and stupefaction. To some people this relation may seem trifling and romantic; it is nevertheless a genuine account; and for that reason I flatter myself that there are some, to whom it will not prove uninteresting.

"When I reflected how continually my ears were stunned with the clang of the whip, and the dismal yell of the wretched negroes, on whom it was exercised from morning till night; when I considered that this might be the fate of the unfortunate mulatto I have been describing, I could not but execrate the barbarity of Mr. D. B. in having withheld her from the protection of an affectionate parent. I became melancholy with these reflections. In order to counter-balance, though in a very small degree, the general calamity of the miserable slaves who surrounded me, I began to take more delight in the prattling of my poor negro boy, Quacco, than in all the fashionable conversation

Page 9

of the polite inhabitants of this colony. But my spirits were depressed; and in the space of twenty-four hours I was very ill indeed; when a cordial, a few preserved tamarinds, and a basket of fine oranges, were sent by an unknown person. This first contributed to my relief; and losing about twelve ounces of blood, I recovered so far, that on the fifth I was able to accompany Capt. Macneyl, who gave me a pressing invitation to his beautiful coffee plantation, on Matapaca Creek.

"On my return, I took an early opportunity to inquire of Mrs. Demelly what was become of the amiable Joanna. She informed me that Mrs. D. B. had escaped to Holland; and that the young mulatto was now at the house of her own annt, a free woman whence she hourly expected to be sent to the estate Fauconberg, friendless, and at the mercy of any unprincipled overseer appointed by the creditors. I flew in search of the poor girl, and found her bathed in tears. When I expressed my compassion, she gave me such a look--ah! such a look! that I determined to protect her from every insult, cost me what it would. Reader, let my youth and extreme sensibility plead my excuse.

Page 10

Yet surely my feelings will be forgiven, except by those few who approve of the prudent conduct of Mr. Inkle toward the unfortunate and much injured Yarico, at Barbadoes.

"I next went to my friend, Mr. Lolkens, who happened to be the administrator of Fauconberg estate, and intimated to him my strange determination of purchasing Joanna, and giving her a good education. Having looked at me in silence, until he recovered from his surprise, he proposed an interview; the beautiful slave, accompanied by a female relation, was accordingly brought trembling into my presence.

"Reader, if the story of Lavinia ever afforded you pleasure, do not reject this account of Joanna with contempt. It now proved to be she who had privately sent me the oranges and cordial, in March, when I was nearly expiring; and she modestly acknowledged that 'it was in token of gratitude for the pity I had expressed concerning her sad situation.' Yet, with singular delicacy, she rejected every proposal of becoming mine upon any terms. She said, that if I soon returned to Europe, she must either be parted from me forever, or accompany me to a land where

Page 11

the inferiority of her condition must prove a great disadvantage to her benefactor and to herself; and in either of these cases, she should be most miserable.

"Joanna returned to her aunt's house, firmly persisting in these sentiments. I could only request Mr. Lolkens to afford her all the protection in his power; and that she might, at least for some time, be allowed to live separate from the other slaves, and remain in Paramaribo. In this request he kindly indulged me.

"Notwithstanding my resolution of living retired, I was again drawn into the vortex of dissipation; and I did not escape without the punishment I deserved. I was suddenly seized with a dreadful fever; and such was its violence, that in a few days I was entirely given over. In this situation, I lay in my hammock until the seventeenth, with only a soldier and my black boy to attend me, and without any other friend. Sickness being universal among the new comers to this country, neglect was an inevitable consequence, even among the nearest acquaintance. The inhabitants of the colony, it is true, not only supply the sick with a variety of cordials at

Page 12

the same time, but they crowd into his apartment, prescribing, insisting, bewailing, and lamenting, friend and stranger, without exception. This continues until the patient becomes delirious and expires. Such must inevitably have been my case, between the two extremes of neglect and importunity, had it not been for the happy intervention of poor Joanna, who one morning entered my apartment, with one of her sisters, to my unspeakable surprise and joy. She told me she had heard of my forlorn situation; and if I still entertained for her the same good opinion I had formerly expressed, her only request was that she might be permitted to wait upon me till I recovered. I gratefully accepted the offer; and by her unwearied care and attention, I had the good fortune to regain my health so far, that in a few days I was able to take an airing in Mr. Kennedy's carriage.

"Till this time, I had been chiefly Joanna's friend; but now I began to feel that I was her captive. I renewed my wild proposals of purchasing, educating, and transporting her to Europe; but though these offers were made with the most perfect sincerity, she once more rejected them, with the following humble declaration:

Page 13

"'I am born a low, contemptible slave. Were you to treat me with too much attention, you must degrade yourself with all your friends and relations. The purchase of my freedom is apparently impossible; it certainly will prove difficult and expensive. Yet though I am a slave, I hope I have a soul not inferior to Europeans. I do not blush to avow the great regard I have for one, who has distinguished me so much above others of my unhappy birth. You have, sir, pitied me; and now, independent of every other thought, I have pride in throwing myself at your feet, till fate shall part us, or my conduct become such as to give you cause to banish me from your presence.'

"She uttered this with a timid, downcast look, and the tears fell fast upon her heaving bosom, while she held her companion by the hand.

"From that moment this excellent creature was mine; nor had I ever any cause to repent of the step I had taken.

"I cannot omit to record, that having purchased for her bridal presents, to the value of twenty guineas, I was greatly astonished to see all my gold returned upon my table. The charming Joanna had carried every article

Page 14

back to the merchants, who had cheerfully restored the money.

"'Your generous intentions toward me are sufficient, sir,' said she; 'allow me to say that I consider any superfluous expense on my account as a diminution of that good opinion, which I hope you now, and ever will, entertain concerning my disinterested disposition.'

"Such was the language of a slave, who had simple nature only for her instructor. The purity of her sentiments requires no comments of mine; I respected them, and resolved to improve them by every care.

"Regard for her superior virtues, gratitude for her particular attention to me, and the pleasure of introducing to the world a character so estimable, rising from a situation usually so hopeless and degraded--these considerations embolden me to risk the censure of my readers, by intruding this subject upon their attention. If my apology be accepted even by a few, I shall not feel inclined to complain.

"In the evening, I visited Mr. Demelly and his lady, who congratulated me on my recovery; and, strange as it may appear to many of my readers, they, with a smile,

Page 15

wished me joy of what they were pleased to call my conquest. One lady assured me that I was censured by some, applauded by many, but she believed in her heart envied by all.

"Many of our respectable friends sanctioned the wedding by their presence; and I was as happy as any bridegroom ever was.

"Thus concludes a chapter, which, methinks I hear many of my readers whisper, had better never had a beginning."

Not long after his marriage, Capt. Stedman was ordered on a distant and hazardous expedition. He commemorates his parting with Joanna in a paraphrase, which does not contrast very favorably with the vigorous simplicity of his prose, or with the spirit and gracefulness of his numerous drawings:

'Now my mulatto cast a mournful look,

Hung on my hand, and then dejected spoke;

Her bosom labor'd with a boding sigh,

And the big tear stood trembling in her eye.'

The affectionate young wife was left under the protection of her mother and aunt, with directions that she should attend school during the absence of her husband.

The campaign was wearisome and fruitless; for the rebel negroes, as cunning as they were courageous, continually eluded pursuit; while the European troops sunk rapidly under manifold sufferings and a burning climate. They were in such a state of starvation, disease and despair, that the slaves (who had been induced, by the offer of freedom, to enlist against their own people) sighed deeply when they looked upon them, and said, 'Oh! poty backera!' 'Oh! poor Europeans!'

Their spirits were sustained by the hopes of being soon recalled. Captain Stedman says:

Page 16

"All seemed to revive when they saw me receive a letter from Colonel Fourgeoud; for we all expected to be relieved from our horrid situation: But what was our surprise and distress, to find that we were ordered to remain on this forlorn station! The men declared they were sacrificed to no manner of purpose. By the distribution of some tamarinds, oranges, lemons, and Madeira wine, sent by my best friend, at Paramaribo, I was enabled to afford them a temporary relief; but the next day we were as much distressed as ever.

"On the ninth, we marched to the port called Devil's Harwar, leaving ten men behind, some with agues, some stung blind, and some with their feet full of the tormenting insects called chigoes. After indescribable sufferings we arrived, covered with mud and blood. I was rejoiced to find Lieutenant Colonel Westerloo had arrived and taken command; I hoped at last to meet with some relief. Having ceded to him my written orders, I plunged into the steam to bathe and swim. I found myself greatly refreshed by this, as well as by receiving a quantity of fine fruit, wine, and sugar, from my Joanna. The surgeons declared that I must soon die,

Page 17

unless I were allowed an opportunity to recruit my health. A consultation was held; and at last, not without great difficulties, a boat was ordered to row me down to Paramaribo. Resting on the shoulder of a negro, I walked to the water-side, followed by my black boy Quacco, and stepping into the boat left the dismal spot where I had buried so many brave fellows.

"At two o'clock in the morning I arrived, extremely ill. Having no house of my own, I was hospitably received by Mr. De la Marre, a merchant, who immediately sent for poor Joanna to come and attend me. I soon found myself in an elegant, well-furnished apartment, encouraged by the physician, caressed by friends, and supported by the care and attention of my incomparable mulatto.

"My linen had been gnawed to dust by the cockroach, called cakreluce in Surinam; but Joanna's industry soon supplied me with a new stock.

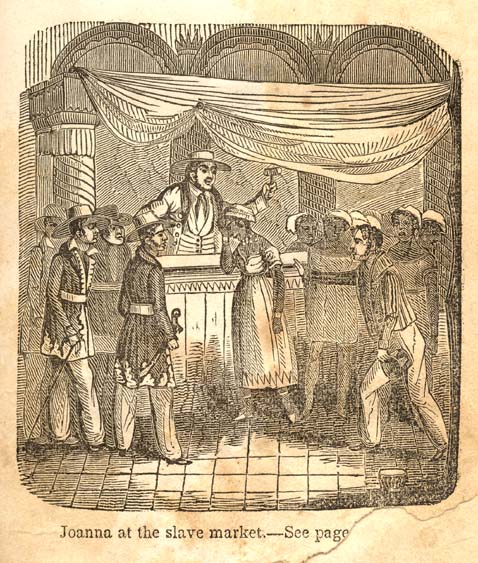

"Before I had entirely recovered from my debilitated condition, I suddenly received the frightful tidings that the estate of Fauconberg, with the whole stock of slaves, was to be sold that very day for the benefit of creditors. I hastened to the slave-market.

Page 18

where I found my poor Joanna. After what I have related concerning the savage treatment universally bestowed upon the slaves, the reader may form some faint idea of my distress. I suffered all the horrors of the damned. Again and again, I bewailed the unworthy fortune that put it out of my power to become her proprietor. I imagined her ensuing dreadful situation. I fancied I saw her insulted, tortured, bowing under the weight of her chains, calling aloud for my assistance, and calling in vain. Misery almost deprived me of my senses. I was restored, in some degree, by the assurances of my friend, Mr. Lolkens, who providentially was appointed to continue administrator of the estate, during the absence of its new possessors, Messrs. Passelage and Son, of Amsterdam. This disinterested and steady friend took Joanna from the auction scene, brought her into my presence, and solemnly pledged himself to protect her and assist me, to the utmost of his power. In this promise he ever after nobly persevered."

Here follows the account of another distressing campaign, which I pass over entirely, because it is unconnected with the subject of the story. Capt. Stedman proceeds as follows:

Joanna at the slave market.--See page

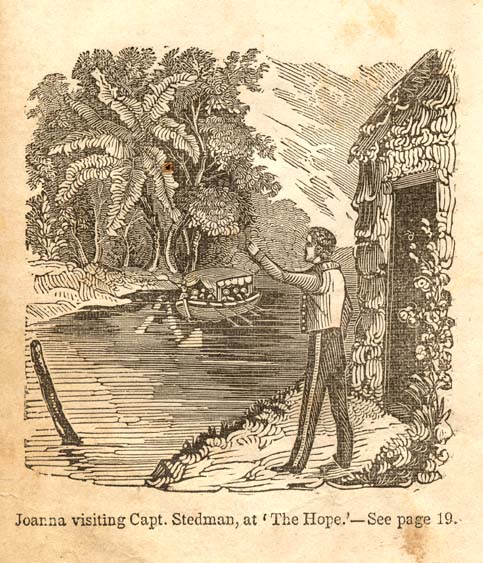

Joanna visiting Capt. Stedman, at 'The Hope.'--See page 19.

Page 19

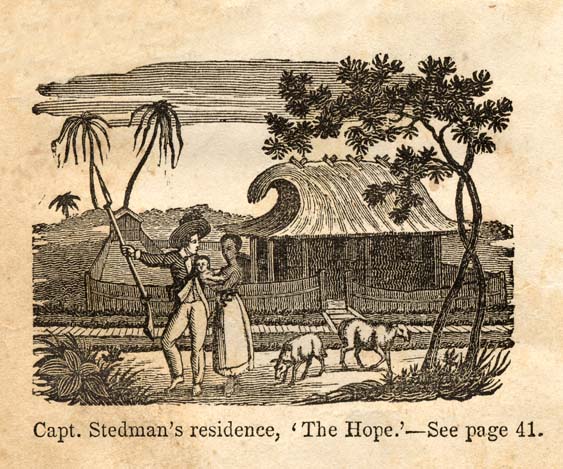

"On the nineteenth, I reached L'Esperance, or The Hope, a valuable sugar plantation, on the beautiful river Comewina. Here the troops were lodged in temporary houses, built with the manicole tree. I became daily more charmed with my situation. I was at liberty to breathe freely; and my prospect of future contentment promised to reward me amply for past hardships and mortifications. The neighboring planters, for whose safety we were stationed at this post, plentifully supplied us with game, fish, fruit and vegetables.

"I had been here but a short time, when I was surprised by the waving of a white handkerchief from a tent-boat, that was rowing up the river; when, to augment my happiness, it unexpectedly proved to be my mulatto, accompanied by her aunt. They now preferred Fauconberg estate, four miles above The Hope, to a residence in town. I immediately accompanied them to that plantation. Here Joanna introduced me to a venerable old slave, her grandfather, who made me a present of half a dozen fowls. He was gray-headed and blind; he had been comfortably supported many years through the kind attention of his numerous offspring. He told

Page 20

me he was born in Africa; where he had once been treated with more respect than any of his Surinam masters ever were in their own country.

"Many of my readers will no doubt be surprised that I so often mention Joanna, and with so much respect. But I cannot speak with indifference of an object so deserving, and whose affectionate attachment to me was more than sufficient to counterbalance all my misfortunes. Her virtue, youth, and beauty, more and more gained my esteem; while the lowness of her origin increased, rather than diminished, my affection. What can I say further upon this subject? I will content myself with the consolation given by Horace to the Roman soldier:

'Let not my Phocius think it shame

For a fair slave to own his flame;

A slave could stern Achilles move,

And bend his haughty soul to love:

Ajax, invincible in arms,

Was captived by his captive's charms.'

"I have already said that I was happy at The Hope; but how was my felicity increased, when Mr. and Mrs. Lolkens came to visit me one evening, and not only gave me the address of Messrs. Passalage and Son, at Amsterdam, but even desired me to take Joanna

Page 21

to live with me at The Hope, where she could be more agreeably situated than cither at Fauconberg or Paramaribo. This arrangement was unquestionably most readily entered into by me. I immediately set the slaves to work to build a house of manicole trees, for the reception of my best friend. In the mean time I wrote to Messrs. Passalage and Son:

'GENTLEMEN,

Being informed by Mr. Lolkens, administrator of the Fauconberg estate, that you are the present proprietors; being under great obligations to one of your slaves, named Joanna, who is the daughter of Mr. Kruythoff; and being grateful to her, particularly for her attendance upon me during dangerous illness, I request your permission to purchase her liberty without delay: which favor shall ever be gratefully acknowledged, and the money for her ransom immediately paid, by

Your most obedient servant,

JOHN GABRIEL STEDMAN,

Capt. in Col. Fourgeoud's Corps ot Marines.

"This letter was accompanied by another from my friend Lolkens, who cheered me with assurances of success.

"In about six days my house was completed. It consisted of a parlor, a bed-chamber, a piazza to sit under before the door, a small kitchen detached from the house, and a poultry house. It was surrounded by a paling to keep off the cattle, and commanded

Page 22

an enchanting prospect on every side. My tables, stools, and benches, were all composed of manicole boards. The doors and windows were guarded by ingenious wooden locks and keys, presented to me by a negro, who made them with his own hands.

"My next care was to lay in a stock of provisions. Flour, salted mackeral, hams, pickled sausages, Boston biscuit, wine, tea, and sugar. "Mr. Kennedy sent me two beautiful foreign sheep and a hog; and Lucretia, my Joanna's aunt, presented two dozen fine fowls and ducks. Vegetables, fish, and venison, came from all quarters, as usual.

"On the first of April, 1774, Joanna came down the river, in the Fauconberg tent-boat, rowed by eight negroes, and arrived at The Hope. I told her of my letter to Holland; and she heard me with that gratitude and modesty in her looks, which spoke more forcibly than any language. I introduced her to her new habitation, where the plantation slaves, in token of respect, immediately brought her presents of cassada, yams, bananas, and plantains. Never were two people more completely happy. Free as the roes in the forest, and disencumbered of all care and

Page 23

ceremony, we breathed the purest air in our walks, and refreshed our limbs in the limped stream. Health and good spirits were again my portion; while my partner flourished in youth and beauty, the envy and admiration of the whole colony.

"On the thirteenth, my worthy friend, Mr. Henneman, arrived from Col. Fourgeoud's camp, with a barge full of men and ammunition. This poor young man was much emaciated with misery and fatigue; I therefore introduced him at his first landing, to Joanna, who was a most incomparable nurse, and under whose care he felt himself extremely happy.

"On the twenty-first several officers came to visit me at The Hope, and I entertained them with a fish dinner. We were very happy, and my guests highly satisfied with their entertainment. But on the morning of the twenty-second, my poor Joanna, who had been our cook, was attacked with a violent fever. She desired to be removed to Fauconberg, where she could be attended by her female relations; and I hastened to comply with her request. On the evening of the twenty-fifth she was extremely ill. I was determined to visit her; but I wished to

Page 24

do it as privately as possible; for I expected Colonel Fourgeoud the next day, and I had no disposition to hear his satirical jokes upon my anxious affection: I likewise knew that the most laudable motives were no protection against his ungovernable temper.

"In order to effect my purpose, I was obliged to pass very near his post; but, however difficult the undertaking, I was resolved, like another Leander, to cross the Hellespont. Having informed my friend Henneman, I set out about eleven at night, in my own barge. I heard Fourgeoud's voice distinctly, as he walked on the beach with some other officers; and immediately the boat was hailed by a sentinel, who ordered us to come ashore. I now thought all was over; but I told the slaves to answer the name of a neighboring plantation, and thus obtained leave to pass unmolested. I arrived safe at Fauconberg, and found my dearest friend much better.

"In the morning, mistaking daylight for moonshine, I overslept myself, and knew not how to return to The Hope; for my barge and negroes could not possibly pass without being recognised by the Colonel. Delay was useless; I therefore set out, trusting entirely to the ingenuity of the slaves, who put

Page 25

me ashore just before we came in sight of head-quarters. One of them escorted me through the woods, and I arrived safe at The Hope. But here my barge soon followed under a guard, with all the poor slaves prisoners. Fourgeoud sent me an order to flog every one of them, as they had been apprehended without a pass, while their excuse was that they had been out fishing for Massera. Their fidelity to me was truly astonishing. They all declared they would have preferred to have been cut in pieces, rather than betray the secrets of so good a master. However, the danger was soon over, for I took all the blame upon myself.

"Colonel Fourgeoud did not visit me on the twenty-seventh; but the next morning Joanna arrived, accompanied by her uncle.

"On the twenty-eighth Fourgeoud came with wrath in his countenance; which alarmed me much. However, I instantly introduced him to my cottage, where he no sooner saw my mate, than the clouds were dispelled from his gloomy forehead, like vapor dispersed by the sun. I confess I never saw him behave with more civility.

'Her heavenly form

Angelic, but more soft and feminine

Page 26

* Milton.

Her graceful innocence, her every air

Of gesture, or least action, overawed

His malice; and with rapine sweet bereaved

His fierceness of the fierce intent it brought.'*

"Having entertained him in the best manner we were able, and confessed the story of the Hellespont, he laughed heartily at the stratagem, and shaking us both by the hand, departed in high good humor.

"This was the golden age of my West Indian expedition. How happy was I at this time, who wanted for nothing, and had such an agreeable partner constantly near me, whose sweet conversation was divine music to my ears, and whose presence banished every feeling of languor or hardship!

"I daily found some new object to describe, and spent the most delightful hours in my walks, constantly accompanied, by my dear mulatto.

"But alas, in the midst of all my hopes, my happiness was blasted by news that Mr. Passalage, to whom I had written for Joanna's manumission, had died suddenly. She was likely soon to become a mother: and this redoubled my distress. The idea that my best friend, and my offspring must be slaves,

Page 27

was insupportable. I was totally distracted--I believe I should have died of grief, if the mildness of her temper had not supported me, by suggesting the flattering hope that Mr. Lolkens would still be able to protect us.

* * * * * * *

"On the twelfth of May, having swum twice across the river Cottica, which is above half a mile broad, I came home in a shiver, and next day had an intermitting fever. By abstaining from animal food, and using plenty of acid with my drink, I had no doubt of getting well in a few days; especially as tamarinds grew here in profusion. Indeed, on the sixteenth, I was almost perfectly recovered, excepting weakness, when, as I was sitting before my cottage with Joanna, I had an unexpected visit from one of our surgeons. Having felt my pulse, and examined my tongue, he declared I should be a dead man before morning, unless I made use of his prescription without delay. Being well aware of the danger of the climate to European constitutions, I instantly swallowed the dose he prepared, although I was not at all in the habit of using medicines. The moment I took it, I dropped down on the ground. In this manner I lay till the twentieth. After

Page 28

four days, I recovered my senses, and found myself stretched on a mattrass, with poor Joanna sitting by me alone, bathed in tears. She begged me to ask no questions then, for fear it would hurt my spirits; but the next day she told me the whole transaction.

"The moment I fell, four strong negroes had taken me up; and by her direction placed me where I now was: The surgeon, having put on several blisters, finally declared I was dead, and suddenly left the plantation. A coffin and grave were prepared for my burial on the seventeenth; but she knelt to implore a little delay; and her tears and entreaties prevailed. Having procured some wine-vinegar and a bottle of old Rhenish, she constantly bathed my temples, wrists, and feet with the former, keeping without intermission five wet handkerchiefs tied around them; while, with a tea-spoon, she found means, from time to time, to make me swallow a few drops of mulled wine. She had attended me day and night, by the help of Quacoo and an old negro, still hoping for my recovery; for which she now thanked her God. To all this, I could only answer with the tears that started to my eyes, and a feeble pressure of her hand.

Page 29

"I had the good fortune to recover; but so slowly, that, notwithstanding the great care taken of me by that excellent woman, it was the fifteenth of June before I was able to walk by myself. Until that time, I was obliged to be carried in a species of sedan chair, supported on poles by two negroes. I was fed like an infant; being so lame and weak, that I could not raise my hand to my mouth. Poor Joanna, who had suffered so much on my account, was, for several days following the twenty-fifth, very ill herself.

"Great was the change from what I had so lately been--the healthiest and happiest of mortals,--now depressed to the lowest ebb in my constitution and spirits. My friend Henneman, who visited me constantly, told me he had discovered that the medicine, which so nearly killed me, was four grains of tartar-emetic with forty grains of ipecacuanha. The surgeon had measured my constitution by my height, which is above six feet.

"Being too weak to perform military duty, I surrendered the command to the officer next in rank, and went to visit a neighboring French planter, who had given me and Joanna a hearty invitation. At this place I was extremely comfortable; and nothing could

Page 30

be better calculated for my speedy recovery than this gentleman's hospitality and good humor. How inconsistent with all this was his severity and injustice to his slaves! Two young negroes, that broke into their master's storehouse, and well deserved a flogging for their robberies, came off with a few lashes; while two old ones, for a trifling dispute, were condemned to receive no less than three hundred. When I asked the cause of this partiality, M. Cachelieu answered, that the young negroes still had a very good skin, and might do much work; whereas the old ones had long been disfigured and worn out, and killing them altogether would be a benefit to the estate.

"After remaining at this plantation nearly two months, we returned to The Hope. Here I found Mr. Henneman, and several others, very ill, without surgeon, medicines, or money. I, however, was so carefully attended by Joanna, that I had little cause to complain, except that my feet were infested with chigoes, a small insect that gets under the skin and occasions intolerable torment.

"Joanna, with her needle, extracted twenty-three of these troublesome insects from under the nails of my left foot. I bore the

Page 31

operation without, flinching, with the resolution of an African.

"I still continued so weak that I almost despaired of recovering perfectly. The depression of my spirits, on account of Joanna's critical and almost hopeless situation, greatly contributed to prevent the restoration of my health. My anxiety was not diminished by hearing that the estate Fauconberg had passed to a new proprietor, a Mr. Lude of Amsterdam, with whom my friend Mr. Lolkens had not the smallest interest; and that there was in town a general report that we had both been poisoned. These tidings were somewhat softened by the kindness of Mrs. Lolkens, who came to insist that my Joanna should accompany her to Paramaribo, where she should have every care and attention her situation required. I thanked her in the best manner I was able, and poor Joanna wept with gratitude. Having accompanied them as far as the estate where they dined, I took my leave of them and Joanna, and bade them all an affectionate farewell for the present.

"On my return to The Hope, I could hardly restrain my indignation at the coarse manner in which my messmates rallied me

Page 32

concerning my anxiety. 'Do as we do, Stedman, said they:

'If our children are slaves, they are provided for; and if they die, what do we care? Keep your sighs in your bosom, and your money in your pocket, my boy.' I repeat this to show how much my feelings must have been hurt and disgusted with similar consolation.

"I wrote to a Mr. Seifke to inquire whether it was not in the power of the Governor and Council to relieve a gentleman's child from bondage, provided the master obtained such ransom as they thought proper to adjudge. I received for answer, that no money or interest could purchase its freedom, unless the proprietor of the mother consented.

"This information completed my misery. I tried to drown reflection in wine; which only raised my spirits for a moment, to make them sink the lower. During this conflict in my feelings, Mr. De Graav kindly invited me to his plantation, and did everything in his power to amuse me; but to no purpose. At last, seeing me seated by myself, on a small bridge that led to an orange-grove, with a settled gloom on my countenance, he took me by the hand, and, to my astonishment, addressed me thus: 'Mr. Lolkens has acquainted

Page 33

me with the cause of your just distress. Heaven never left a good intention unrewarded. I have the pleasure to inform you that Mr. Lude has chosen me his administrator. I shall pride myself upon rendering any service in my power to you and the virtuous Joanna, whose character has attracted the attention of so many people; while your laudable conduct toward her redounds to your lasting honor throughout the colony.'

"No criminal under sentence of death could have received a reprieve with greater joy. I returned to The Hope with the feeling that I might yet be happy.

"On the fourth of December I received tidings that my Joanna was the mother of a strong, beautiful boy; upon which occasion I roasted a sheep, and entertained all my brother officers. That very morning I wrote to Mr. Lude at Amsterdam, to obtain her manumission; urging despatch, because I was uncertain how much longer our troops would remain in Surinam. In this request I was seconded by my new friend, Mr. De Graav, as I had before been by Mr. Lolkens.

"I was not able to take a trip to Paramaribo until the eighteenth. I found Joanna

Page 34

happy and perfectly recovered; and my boy, according to the practice of the country, bathing in Madeira wine and water, generously given by Mrs. Lolkens. I gave Joanna a gold medal, which my father had presented to my mother on the day of my birth. Having thanked Mrs. Lolkens for her very great kindness, I returned to The Hope on the twenty-second.

"I found that a poor negro, whom I had sent with a letter to Joanna, before I was able to visit her myself, had had his canoe upset by the roughness of the water, in the middle of the river Surinam. He was unable to swim, but had the address to keep himself in an erect posture. By the buoyancy and resistance of the boat he was able to keep his head just above the water, while the weight of his body kept the canoe from sinking. In this precarious situation, he was taken up and put ashore by a man-of-war's boat, who kept the canoe for their pains. He preserved the letter in his mouth, and, being eager to deliver it, accidentally ran into the wrong house; where being taken up for a thief, he was tied up to receive four hundred lashes; he was saved by the intercession

Page 35

of an English merchant, my particular friend. Thus the poor fellow escaped drowning and flogging, either of which he would have undergone, rather than disclose the secrets of his Massera. How many Europeans are possessed of equal fidelity and fortitude?

* * * * * * *

"On the fifteenth of July, 1775, I received letters acquainting me finally, and to my heartfelt satisfaction, that the amiable Joanna and the little boy were at my disposal; but at no less a price than two thousand florins; amounting, with other expenses, to two hundred pounds sterling; a sum which I was totally unable to raise. I already owed fifty pounds to Col. Fourgeoud, that I had borrowed for the redemption of my black servant, Quacco. But Joanna was to me invaluable. Though appraised at one twentieth part the whole estate of Fauconberg, no price would be too dear for one so excellent, provided I could pay it.

"When the letters first arrived, they had a most reviving effect upon me: but when I reflected how impossible it was for me to obtain such a sum,--and while I was employed

Page 36

in making trifling presents to Joanna's relations at Fauconberg, who loaded me with adoration and caresses,--I exclaimed with a bitter sigh, 'Oh, if I could but find money enough to obtain freedom for them all!'

"Being still weak, Mr. Gourlay humanely caused me to be transported to Paramaribo in a tent-barge. I had a relapse of my illness, and arrived just alive on the evening of the nineteenth, having passed the night on the estate called the Jalosee, apparently dead.

"But comfortably lodged in the house of my friend, Mr. de la Marre, and attended by my good Joanna, I recovered apace. On the twenty-fifth, I was able to walk out; but Mr. De Graav was not in town to concert matters relative to the emancipation of my best friend, who had a second time literally saved my life.

"On the third of August Mr. De Graav arrived; and I took the earliest opportunity to beg him to give me credit for the money demanded for my Joanna and her boy. I was determined to save it out of my pay, if I lived merely on bread, and salt, and water; though even then, the debt could not be discharged under two or three years.

Page 37

"However, Providence interfered, and sent my excellent acquaintance, Mrs. Godefroy, to my assistance. As soon as she heard of my difficult and anxious situation, she sent for me to dine with her, and addressed me as follows: 'I know the feelings of your heart, and the incapacity of an officer, from his income only, to accomplish such a purpose as the completion of your wishes. But be assured even in Surinam virtue will meet with friends. Your manly sensibility for that deserving woman and your child must claim the esteem of all rational persons, in spite of malice and folly. So much has your conduct recommended you to my attention, that I beg leave to have a share in your happiness, and the future prospects of your virtuous Joanna, by requesting you to accept from me the sum of two thousand florins. Take the money, Stedman--and go immediately to redeem innocence, good sense, and beauty, from tyranny and insult.'

"Seeing me gaze upon her, utterly stupified with amazement, she smiled and said--'Sailors and soldiers should ever be men of the fewest compliments. All I ask is, that you will say nothing upon the subject.

"Having expressed myself as well as my

Page 38

overflowing heart would permit, and promised to call the next day, I immediately retired. I hastened to acquaint Joanna with what had happened. Bursting into tears, she exclaimed, 'God will bless that woman!' She insisted upon being mortgaged to Mrs. Godefroy, till the utmost farthing was paid. She was indeed most anxious for the emancipation of her child; but till that was done, she absolutely refused to accept her own freedom.

"I will not describe the contest I sustained between affection and duty; but bluntly say that I yielded to the wishes of this charming creature, whose sentiments endeared her to me more and more. I drew up the paper, which bound her to Mrs. Godefroy, until the last farthing of the money should be paid; and the next day with the consent of her relations I conducted her to that lady's house. Joanna threw herself at her feet and presented the paper. Mrs. Godefroy raised her up, saying, 'If you will have it so, Joanna, you shall remain with me: but I accept you as my companion, not as my slave. You shall have a house built for you in the orange garden, and slaves to attend upon you, until Providence shall call

Page 39

me away. You shall then be perfectly free, as indeed you now are, the moment you wish for manumission. Your virtues, and your parentage give you a claim to this.'

"On these terms, I accepted the money; and my friend was transferred from the wretched estate Fauconberg, to the protection of perhaps the best woman in the Dutch West Indies, if not in the world. When I showed Joanna the receipt in full, she thanked me with a look that could only be expressed by the countenance of an angel.

'Mr. De Graav insisted upon having a share in the happy event, by refusing the sum due to him as administrator. 'I am amply paid,' said he, 'in being the instrument to bring about what seems to contribute so much to the enjoyment of two deserving people.'

"Having thanked my disinterested friend, with a cordial shake of the hand, I immediately restored to Mrs. Godefroy the two hundred florins, which she refused.'

* * * * * * *

After describing another tedious and dangerous campaign, during which he was several times very near losing his life, and Joanna and her boy narrowly escaped dying of a fever, Capt. Stedman continues:

"On the third of January, 1776, I arrived

Page 40

once more at Paramaribo, and found my little family perfectly recovered, though they had been blind for more than three weeks. Being invited to take up my abode with them, at the house of my friend Mr. De Graav, I was again completely happy.

"On the twenty-fifth, I was attacked with fever, and made lame by the surgeon, who struck too deep when he blooded me in the foot. On the fourteenth of February, ill as I was, with a lame foot, a sore arm, the prickly heart, and my teeth all loose with the scurvy, I found means to scramble out on crutches, with a thousand florins in my pocket, which I divided between Mrs. Godefroy and Col. Fourgeoud, for the redemption of my mulatto, and the black boy, Quacco. I returned home without a shilling in my purse. Mrs. Godefroy generously renewed her persuasions of carrying Joanna and the boy with me to Holland. But this Joanna nobly and firmly refused. 'Independent of all other considerations,' said she, 'I can never think of sacrificing one benefactor to the interest of another. My own happiness, or that of him who is dearer to me than life, must not be allowed to have any weight, until the price of my liberty is paid to the utmost

Capt. Stedman's residence, 'The Hole.'--See page 41.

Page 41

fraction, by his generosity and my own industry. I do not despair of seeing this completed. If we are separated, I trust it will be only for a time. The greatest proof that Capt. Stedman can give me of real esteem is to undergo this trial like a man, without so much as heaving a sigh in my presence.'

"She spoke this with a smile, embraced her infant, then turned round suddenly and wept bitterly.

"On the fifteenth, news arrived that the orders for return were countermanded, and that we were to remain six months longer in Surinam. All the officers, except myself, were grievously disappointed. I rejoiced in the determination to save all my pay until Joanna's redemption was completed.'

The details of another campaign are given; and, after various adventures, Capt. Stedman returns to The Hope. He says:

"On the eighth of May, Joanna arrived with our boy; and I promised myself a scene of happiness equal to that I had enjoyed in this place in 1774; especially as my family, my sheep, and my poultry were now doubled: besides I had at this time a beautiful garden, and if I could not with

Page 42

propriety be called a planter, I might at least claim with some degree of justice, the name of a small farmer.

"On the ninth we all dined with Mr. De Graav, at his beautiful plantation on Cassawina Creek; where this worthy man had foretold, before the birth of my boy, that both he and his mother would one day be free and happy. We returned in a boat loaded with presents of every kind. The slaves of The Hope and Fauconberg likewise testified their respect for Joanna, by bringing in fowls, fruit, eggs, venison and fish. Everything seemed to contribute to our felicity.

"The Hope was now a truly charming habitation; being perfectly dry; even in spring-tides, and washed by pleasant canals, that let in the fresh water every tide. The hedges were neatly cut, and the garden was filled with fruit and vegetables. Jessamines, pomegranates, and Indian roses flourished in my garden, while beautiful wild red lilies, with leaves of bright and polished green, adorned the banks of my canals.

"Thus situated, we were visited, among others, by a Madame de Q--e, in company with her brother, lately arrived from Holland. This lady was supposed to be the

Page 43

most accomplished woman Europe produced. She spoke several languages, was perfect mistress of music and painting, danced elegantly, and rode extremely well on horseback. She even excelled in shooting and fencing.

"On the twenty-third of June, I received positive orders to prepare and be ready on the fifteenth of July, to leave the Comewina, and row down to Paramaribo, where the transport ships were put in commission to carry us back to Holland. The troops received these tidings with unbounded joy. I alone sighed bitterly. Oh, my Joanna! Oh, my boy! Both were at this time dangerously ill; the one with a fever, the other with convulsions; so that neither were expected to survive. As soon as they were able to be removed, I thought it necessary to send them to Paramaribo, before it was too late.

"On the fourteenth, I removed my flag from The Hope to the barges; and in the evening took my last farewell of Joanna's relations on the Fauconberg estate. They crowded around me, mourning aloud for my departure, and invoking the protection of Heaven for my safe and prosperous voyage to Europe.

Page 44

"At Paramaribo I found, to my great joy, that Joanna and the child were very much recovered. When I offered Mrs. Godefroy 40 pounds more, (being all the money I had) that excellent woman renewed her entreaties that I would carry my boy and his mother with me to Holland. But Joanna was immovable, even to a degree of heroism. No persuasion could make the least impression upon her. We affected to bear our fate with perfect resignation, though what each of us felt may more easily be imagined than described.

"On the very eve of departure, orders again arrived for the troops to remain until reinforcements were sent out from Holland. When these orders were proclaimed, I never saw dejection, disappointment and despair so strongly marked on the countenances of men. I alone was raised from misery to joy.

* * * * * * *

"On the tenth of August, I waited upon Mrs. Godefroy, and told her my earnest wish to see everything arranged with certainty concerning the emancipation of little Johnny Stedman. I requested her to become bail before the Court, for the usual sum of three hundred pounds; assuring her that he should

Page 45

never be any charge to the Colony of Surinam. This she decidedly declined, though it was a mere matter of form. I was at first very much astonished; but I found afterward that she had refused a similar favor to her own son.

"Poor Joanna remained inflexible in her resolution; and on the twenty-fourth, an agreement with Mrs. Godefroy was solemnly ratified in the presence of her mother and all her relations, whereby that lady bound herself never to part with her except to myself alone; and that upon her death, not only her full liberty, but a spot of ground for cultivation, with a neat house built upon it, should be her portion forever, to dispose of as she pleased. After this, she returned my remaining bond of nine hundred florins, and gave Joanna a purse containing near twenty ducats, besides two pieces of East India chintz. At the same time, she advised me to give into the Court a request for little Johnny's immediate manumission. She said it was a necessary form, whether I were able to obtain the bail usually required, or not; and that even if the bail should be ready to appear, nothing could be done if this formality were dispensed with.

Page 46

"Having both of us thanked this most excellent woman, I went to sup with the governor, and gave him my request in full form. He coolly put it in his pocket with one hand, while he gave me a hearty squeeze with the other; and shaking his head, he told me frankly that he was convinced my boy must die a slave, unless I could find the necessary bail; which he was well persuaded few people would wish to appear for. Thus after so much time and labor, besides the expense of more than a hundred guineas, I still had the inexpressible mortification of seeing this dear little fellow in danger of perpetual servitude. As for Joanna, she, to my heartfelt satisfaction, was now perfectly safe."

* * * * * * *

After describing some shocking scenes of cruelty toward the slaves, Capt. Stedman continues:

"Disgusted with the sight of barbarity which I could not prevent, I left the estate Catwyk, determined never more to visit it. I made my retreat to the estate Sgraven Hague; and there I chanced to meet a mulatto youth in chains, whose father I well recollected. The unhappy man had been obliged to leave his son a slave, and was now

Page 47

dead. The thought of my own poor boy gave me horrible sensations.

"I have already stated that I gave in a fruitless request to the Governor for my son's manumission. On the eighth of October I saw with joyful surprise, the following advertisement posted up: 'If any one can give in a lawful objection why John Stedman, a Quadroon infant, son of Captain John Stedman, should not be presented with the blessing of freedom, such person, or persons are requested to appear before January 1st, 1777.' I no sooner read it, than I ran with the good news to my friend, Mr. Palmer, who assured me it was a mere form, put in practice on the supposition of my producing the required bail, which was undoubtedly expected, from my having so boldly given in my request to the Governor of the Colony. Unable to utter a syllable in reply, I retired to the company of Joanna, who with a smile bade me never despair, for Johnny would certainly one day be free. She never failed to give me consolation, even when my prospects were the darkest, and my feelings the most desperate.

* * * * * * *

"Having been some time encamped in the

Page 48

woods, in a paltry hut, beaten by wind and rain, and receiving tidings that we were to remain some time longer, I earnestly set about building me a hut. It was finished on the eighteenth of December, in less than six days, without nail or hammer, though it had two rooms, a piazza with rails, and a small kitchen, besides a garden, in which I sowed, in pepper-cresses, the names of Joanna and John. During this short period of tranquility, I constructed in miniature, my cottage, in which I had enjoyed so much domestic felicity, at The Hope. It was made on an oblong board, of about eighteen inches by twelve, entirely of the manicole tree and its branches, like the original; and was esteemed quite a masterpiece. I sent it as a present to my friend, Mr. De Graav, at Paramaribo, who has since placed it in a cabinet of natural curiosities at Amsterdam.

"Illness soon broke out in the camp, and mortality every day gained ground, under the most loathsame and hideous form; and to complete the distress, a part of the camp took fire.

"My misery, however, received an unexpected termination on the twenty-sixth of January, by Colonel Fourgeoud's giving me,

Page 49

unasked, leave of absence, if I chose to accompany him to Paramaribo. I joyfully accepted the offer. On the way, he informed me of his determination to return to the woods no more, and in a few weeks to draw this long and painful expedition to a conclusion.

"I arrived in fine spirits and perfect health; and was most heartily welcomed by my friends, who rejoiced to see me once more alive. Not wishing to be troublesome to any person, I hired a small neat house by the water-side, where Joanna and I lived almost as happily as we had done at The Hope.

"On the sixteenth of February, being invited to dine with his excellency the Governor, I laid before him my collection of drawings, and my remarks on the Colony of Surinam, which he honored with the highest approbation. Availing myself of his friendship, I ventured, two days after, to give him the following very uncommon request, praying him to lay it before the Court. With a smile on his countenance and a hearty shake of the hand, he promised compliance.

"'I, the undersigned, do pledge my word of honor, (being all I possess in the world, besides my pay,) as bail, that if my late ardent request to the Court, for the emancipation of my dear boy, John Stedman, be granted, the said

Page 50

boy shall never, to the end of his life, become a charge to the Colony of Surinam.

'JOHN G. STEDMAN.

'Paramaribo, Feb. 18, 1777.'"Having now done all that lay in my power, I awaited the result with anxiety. After several days I began to be afraid that I must finally give the sweet little fellow over for lost, or take him with me to Europe, which must have been plunging a dagger in the heart of his mother.

"My uneasiness was not of very long duration. I was one day agreeably surprised by a polite message from the Governor and Court, acquainting me, that 'having taken my former services into consideration, together with my humanity and gallantry in offering my honor as bail, to see my child made a free citizen of the world, they had unanimously agreed, without further ceremony or expense, to present me with a letter containing his emancipation from that day forever after.'

"No man could be more suddenly transported from anxiety to joy, than I was at that moment; while his poor mother shed tears of delight and gratitude; the more so, as we had almost lost our hopes. More than forty beautiful boys and girls, the children of

Page 51

my acquaintance, were left in perpetual slavery, without being so much as inquired after. A few approved highly of my conduct; while many not only blamed, but publicly derided me, for what they termed a ridiculous weakness. But so extravagant was my joy on this day, at having acted a part the reverse of Inkle to Yarico, that I was half frantic with pleasure. I made my will in favor of my boy, and appointed two of my friends his guardians during my absence; leaving all my papers sealed with them, in case of my death. I ordered all my sheep and poultry, which had prodigiously increased, to be put under their care, for his use; and I waited on a clergyman to appoint a day for his baptism. To my great surprise, the Reverend gentleman refused to christen the boy; alleging that as I was going to Europe, I could not answer for his Christian education. I replied that the child was under the care of two very proper guardians; but he was deaf to my arguments; and I left him, saying, I preferred my boy should die a heathen, rather than be baptised by such a blockhead.

"The day of our departure now drew so near, that I was obliged to give up my house. At Mrs. Godefroy's pressing invitation, I

Page 52

spent the few remaining days with Joanna, in the dwelling she had so generously prepared for her reception, under the shade of tamarind and orange trees. The house was furnished with everything that could be desired; and a negro woman and girl were appointed to attend upon her. Thus situated, how blessed could I have been to the end of my days! But fate ordered it otherwise.

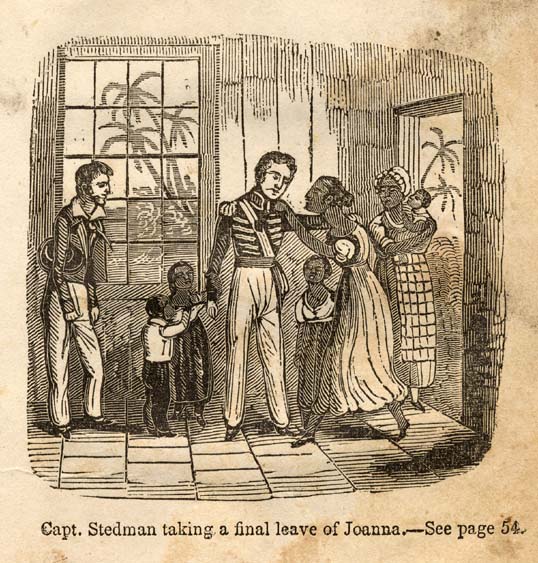

"On the evening of the twenty-sixth, I took leave of the numerous friends, who had treated me with so much kindness, since I had been in the Colony; but my soul was too full of a friend dearer than all, to feel what I should have felt at parting under other circumstances.

"While I gave the most impetuous vent to my feelings, not the smallest expression of grief, or even of dejection, escaped Joanna's lips. Her good sense, her fortitude, and her affection for me, restrained the tears in my presence. I once more earnestly entreated her to accompany me; and I was seconded by Mrs. Godefroy and all her friends; but she remained firm. Her answer was, that 'dreadful as this fatal separation appeared--perhaps never more to meet,--she felt that it was her duty to remain in Surinam. First,

Page 53

from a consciousness that she had no right to dispose of herself; secondly, because she had rather be among the first of her own class in America, than a disgrace to me in Europe; and lastly, because she was aware that she must be a burthen to me, unless my circumstances became more independent.'

"As she said this, she showed great emotion, but immediately retired to weep in private. What could I say, or do? Not knowing how to admire sufficiently her fortitude and resignation, I resolved if possible to imitate her example. I calmly resigned myself to my fate, and prepared for the painful moment, when my heart forbode me we were to separate forever.

* * * * * * *

"On the twenty-ninth of March, at midnight, the signal gun was fired. The ships got under weigh, and dropped down before the fortress of New Amsterdam, where they once more came to an anchor.

"Here my friends Gordon and Gourlay, the guardians of my boy, came to insist upon my going back with them to Paramaribo. My soul could not resist the hope of once more seeing what was so dear to me. I went--and found Joanna, who had displayed so

Page 54

much fortitude in my presence, now bathed in tears, and scarcely alive--so much was she become the victim of melancholy and despair. She had not partaken of food or sleep since my departure--nor spoken to any living creature--nor stirred from the spot where I had left her on the morning of the twenty-seventh. She seemed cheered by the prospect of my staying on shore a little longer. But, alas! we paid too dear for this short reprieve! Only a few hours had elapsed, when a sailor came in, saying the ship's boat lay in waiting at that moment to carry me on board. Oh, who can describe my feelings at that instant! Joanna's mother took the infant from her arms, while her brothers and sisters hung around me, crying, and invoking Heaven aloud for my safety. The unfortunate Joanna, now only nineteen, clung to my arm and gazed upon me without the power to utter one word. We exchanged ringlets of hair--I pressed her and my child fondly to my bosom. My heart invoked for them the protection of Providence--but I could not speak. Joanna closed her beautiful eyes--her lips became pale as death--and she sunk lifeless into the arms of her adopted mother. Rousing all my remaining

Page 55

fortitude, I rushed from the house bidding God bless them."

* * * * * * *

Here follows an account of Capt. Stedman's voyage, his promotion in the army, and his reception in Holland and England. His black boy Quacco, whose freedom he had purchased, accompanied him to Amsterdam, and became butler to the Countess of Rosendaal. He mentions a pleasing anecdote concerning the attachment of this boy. Having found a crown piece more than he expected in his purse, he questioned Quacco; who replied, 'I was afraid you might be short of cash, where people seem so fond of it; and I put my five shilling piece into your pocket.' This was the more generous, being the only crown poor Quacco possessed in the world.

No further mention is made of Joanna, until near the close of the volume. It is as follows:

"In August, 1783, I received the melancholy tidings from Mr. Gourlay, that Joanna was no more. She had died on the fifth of November preceding. Some suspected she was poisoned by the hand of jealousy and envy, on account of her prosperity, and the marks of distinction which her superior character so justly attracted from the most respectable people in the Colony. Mrs. Godefroy wept for her with sincere affection, and ordered her beautiful body to be buried with every mark of respect, under the orange grove where she had lived. Her lovely boy was sent to me, with nearly two hundred

Page 56

pounds, which he received by inheritance from his mother. This charming youth made a most commendable progress in his education at Devon; went two West India voyages, with the highest character as a sailor; served with honor as midshipman on board his Majesty's ships Southampton and Lizard, ever ready to engage in any service for the benefit of his king and country; and finally perished at sea, off the island of Jamaica."

'Yet one small comfort soothes, (while doomed to part,

Dear, gallant youth!) thy parent's breaking heart.

No more thy tender frame, thy blooming age,

Shall be the sport of Ocean's stormy rage;

No more thy olive beauty, on the waves,

Shall be the sport of some European slaves.

Soar now, my angel, to thy Maker's shrine,

And reap reward due to such worth as thine.

Fly, gentle shade--fly to that blest abode,

There view thy mother, and adore thy God;

There, oh, my boy!--on that celestial shore,

Oh, may we gladly meet--and part no more.'

Such is Capt. Stedman's own account of the beautiful and excellent Joanna. In reading it, we cannot but feel that he might have paid Mrs. Godefroy, and sent for his wife to England, long before 1783. His marriage was unquestionably a sincere tribute of respect to the delicacy and natural refinement of Joanna's character. Yet we find him often apologizing for feelings and conduct, which are more truly creditable to him than any of his exploits in Surinam; and he never calls her his wife. Perhaps Joanna, with the quick discernment of strong affection, perceived that he would be ashamed of her in Europe, and therefore heroically sacrificed her own happiness. If he had any reluctance to

Page 57

acknowledge his love, his admiration and his gratitude in England, he is at least manly enough to be ashamed of confessing it.

Captain Stedman appears to have been extremely kind-hearted, and strongly prepossessed in favor of the African character. He was often made ill and wretched by the cruelties he witnessed;--(cruelties, which the imagination of the most 'fanatical' Abolitionist could never have conceived;) he saved a negro slave from a dreadful whipping by restoring a dozen of china, which she had accidentally broken;--while fighting to support the tyranny of slave owners, he mourned over the horrors of slavery, and left a share of his own provisions, by stealth, in the woods, where he had seen a poor rebel, half starved negro concealed;--he was even unhappy for days, because he could not forget the reproachful look of a dying monkey, which he had shot in order to release the poor animal from lingering torments. Yet he conjured the English Abolitionists not to oppose the continuance of the Slave-trade; lest Holland should make more money than England! Alas, for the inconsistency and selfishness of man!

Page 59

A NEGRO MOTHER'S APPEAL

WHITE Lady, happy, proud and free!

Lend, awhile, thine ear to me;

Let the Negro Mother's wail

Turn thy pale cheek yet more pale.

Yes, thy varying cheek can show

Feelings none save mothers know;

My sable bosom does but hide

Strong affection's rushing tide.

Joy, fair lady, with the name

Of Mother, for thy first-born came,

Joy unmingled with the fear

Which dwells, alas! for ever here.

Can the Negro Mother joy

Over this, her captive boy,

Who, in bondage, and in tears,

For a life of woe she rears?

Though she bears a mother's name,

A mother's rights she may not claim,

For the white man's will can part

Her darling from her bursting heart.

Safe within thy circling arms,

Thou mayst watch the opening charms

Of the babe who sinks to rest

Cradled on thy snowy breast;

Confiding in thy right divine,

Press his rosy lips to thine;

By no force, nor fraud, can he

Snatched from thy embraces be.

Gently nurtured shall he grow;

Bitter toil shall never know;

Page 60

Never feel the gnawing pain.

Of the captive's hopeless chain.

And thou wilt bid him fix his eye

On a bright home in the sky;

And teach him how to lift his prayer

To a gracious Father there.

I hear, too, of that God above,

Some tell me that his name is Love;

That all his children, dark or fair,

Alike his pitying favor share.

They tell me that our Father bade

All love the creatures he has made;

That none should ever dare oppress,

But seek each other's happiness.

Yet I see the white man gain

His riches by the Negro's pain;

See him close his eyes and ears

To his brother's cries and tears.

But, Lady, when thy look, so mild,

Rests upon thine own fair child,

Think, then, of one less fair, indeed,

But one for whom thy heart should bleed.

Born to his parents' wretched fate,

Him no smiling hours await:

Toil, and scourge, and chain, his doom,

From the cradle to the tomb.

When bow'd beneath his earthly woes,

His fainting heart would seek repose,

And listen to the holy call,

Which bids him trust the Lord of all;

When he in lowly prayer would bend

Before an everlasting Friend;

Page 61

Learn how to reach those mansions blest

Where even he at length may rest;

By a stern master's jealous pride

This blessing, too, may be denied;

He may forbid his care-worn slave

To look for hope beyond the grave.

Oh! if that blessed law be true,

They tell me Jesus preach'd to you,

'Tis well, perhaps, to veil its light,

From the poor bondsman's aching sight.

Lest too clearly he might trace

The records of a Father's grace;

Read his own wrongs in words of flame,

And his lost birthright proudly claim.

Yet, white men, fear not; even we,

Despised, degraded, though we be,

Have hearts to feel, to understand,

And keep your Master's great command.

That faith, your kinder brethren bring,

Like Angels on their healing wing,

To cheer us in the hour of gloom,

With glimpses of a brighter home;

That faith, beneath whose hallow'd name,

Ye work the deeds of sin and shame,

Which bids the sinner turn and live,

Can teach the Negro to forgive.

For all the gems of Afric's coast,

And fruits her palmy forests boast;

I would not harm that boy of thine,

Nor bid him groan and toil for mine.

I would but, on my bended knee,

Beseech that mine might be as free;

Page 62

Child of the same indulgent Heaven,

Might share the common blessings given.

I would but, when the lisping tone

Of thy sweet infant mocks thine own,

That thou shouldst teach his earliest thought

To spurn the wealth by slavery bought.

I would but, when thy babe is prest

With transports to a father's breast,

Thy gentle voice should plead the cause

Of Nature and her outrag'd laws;

Should bid that father break the chain

In which he holds our wretched train,

And by the love to thee he bears,

Dispel the Negro Mother's fears.

By thy pure, maternal joy,

Bid him spare my helpless boy;

And thus a blessing on his own

Seek from his Maker's righteous throne.

Page 63

THE SLAVE-DEALER.

[From Pringle's African Sketches.]

From ocean's wave a wanderer came,

With visage tanned and dun:

His mother when he told his name,

Scarce knew her long lost son;

So altered was his face and frame

By the ill course he had run.

There was hot fever in his blood,

And dark thoughts in his brain;

And oh! to turn his heart to good,

That mother strove in vain,

For fierce and fearful was his mood,

Racked by remorse and pain.

And if, at times, a gleam more mild

Would o'er his features stray,

When knelt the widow near her child,

And he tried with her to pray;

It lasted not--for visions wild

Still scared good thoughts away.

'There's blood upon my hands!' he said,

'Which water cannot wash;

It was not shed where warriors bled--

It dropped from the gory lash,

As I whirled it o'er and o'er my head,

And with each stroke I left a gash.

'With every stroke I left a gash,

While negro blood sprang high;

And now all ocean cannot wash

My soul from murder's dye;

Nor e'en thy prayer, dear mother, quash

That woman's wild death cry!

Page 64

'Her cry is ever in my ear,

And it will not let me pray;

Her look I see--her voice I hear--

And when in death she lay,

And said, 'With me thou must appear

On God's great judgment-day!'

'Now, Christ, from frenzy keep my son!'

The woful widow cried;

'Such murder foul thou ne'er hast done--

Some fiend thy soul belied!.'--

'Nay, mother! the Avenging one

Was witness when she died!

* Long after the sketch entitled 'The Slave Dealer' was written, I found the following account of a case remarkably similar to the supposed one, related by the Rev. T. R. England at an anti-slavery meeting at Cork, in September, 1829: 'One day I was sent for to visit a sailor who was approaching fast to his eternal account. On my speaking to him of repentance, he looked sullen and turned from me in the bed; of a great God, he was silent; of the mercy of that God, he burst into tears. 'Oh!' said he, 'I can never expect mercy from God. I was ten years on board a slave ship, and then superintended the cruel death of many a slave. Many a time, amid the screams of kindred, has the sick mother, father and new-born babe, been wound up in canvass and remorselessly thrown overboard. Now their screams haunt me night and day, and I have no peace, and expect no mercy!'--African sketches, page 526.

'The writhing wretch with furious heel

I crushed--no mortal nigh;

But that same hour her dread appeal

Was registered on high;

And now with God I have to deal,

And dare not meet his eye!'*

Page 65

STANDARD

ANTI-SLAVERY WORKS,

FOR SALE BY

ISAAC KNAPP,

At the Depository, No. 25, Cornhill, Boston.

JAY'S INQUIRY: 206 pp. 12 mo. cloth. 37 1-2 cts.

An inquiry into the character and tendency of the American Colonization and American Anti-Slavery Societies. By William Jay, of Bedford, New York, son of the celebrated John Jay, first Chief Justice of the United States.--This book is in two parts. The first contains copious extracts from the slave laws, besides being the best Manual, which is now for sale, exhibiting the odious and repulsive character of Colonization. The second part unfolds the principles of anti-slavery societies, answers objections to them, and, by historical facts and unanswerable arguments, shows their adaptation to the end in view, and the glorious consequences which must follow from their adoption. It gives much useful information, respecting St. Domingo, and the working of the British Emancipation Act.

MRS. CHILD'S APPEAL. 216 pp. 12 mo. cloth. 37 1-2 cts.

An Appeal in favor of that class of Americans called Africans. By Mrs. Child, Author of the Mother's Book, Frugal Housewife, &c. With two engravings. Second edition, revised by the author.

Page 66

Page 67

Page 68

Page 69

Page 70

Page 71

Page 72

Return to Menu Page for Narrative of Joanna; An Emancipated Slave, of Surinam... by John Gabriel Stedman

Return to North American Slave Narratives Home Page

Return to Documenting the American South Home Page