Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro:

His Anti-slavery

Labours

in the United States, Canada, & England:

Electronic Edition.

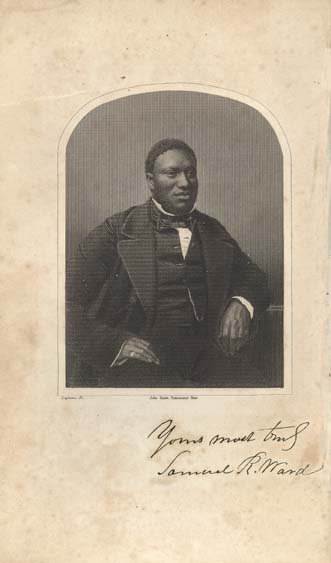

Ward, Samuel Ringgold, b. 1817.

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Bethany Ronnberg and Kevin O'Kelley

Images scanned by

Bethany Ronnberg

Text encoded by

Lee Ann Morawski and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 700K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Call number T E449 .W27 (Treasure Room Collection, James E. Shepard Memorial Library, NCCU)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American

South.

All footnotes are

inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

The publisher's

advertisements following p. 412 have not been included.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as --

Indentation in lines

has not been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

- LC Subject Headings:

- Ward, Samuel Ringgold, b. 1817.

- African Americans -- United States -- Biography.

- African American abolitionists -- United States -- Biography.

- Fugitive slaves -- United States -- Biography.

- Abolitionists -- United States -- Biography.

- Slavery -- United States -- History.

- Antislavery movements -- United States.

- Antislavery movements -- Canada.

- Antislavery movements -- Great Britain.

- Slaves' writings, American.

- 2000-04-04,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-10-14,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-10-01,

Lee Ann Morawski

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-09-19,

Bethany Ronnberg and Kevin O'Kelley

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

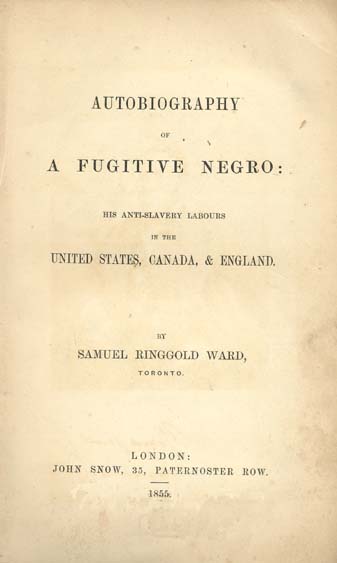

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

OF

A FUGITIVE NEGRO:

HIS ANTI-SLAVERY LABOURS

IN THE

UNITED STATES, CANADA, &

ENGLAND.

by

SAMUEL RINGGOLD WARD,

TORONTO.

LONDON:

JOHN SNOW, 35, PATERNOSTER ROW.

1855.

Page iii

TO HER GRACE

THE DUCHESS OF SUTHERLAND.

MADAM:

The frank and generous sympathy evinced by your Grace in behalf of American slaves has been recognized by all classes, and is gratefully cherished by the Negro's heart.

A kind Providence placed me for a season within the circle of your influence, and made me largely share its beneficent action, in the occasional intercourse of Nobles and Ladies of high rank, who sympathize in your sentiments. I am devoutly thankful to God, the Creator of the Negro, for this gleam of his sunshine, though it should prove but a brief token of his favour; and desire that my oppressed kindred may yet show themselves not unworthy of their cause being advocated by the noblest of all lands, and sustained and promoted by the wise and virtuous of every region.

I cannot address your Grace as an equal; though the generous nobility of your heart would require that I should use no expression inconsistent with the dignity of a man, the creation of God's infinite wisdom and goodness. I cannot give flattering titles, or employ the language of adulation:

Page iv

I should offend your Grace if I did so, and prove myself unworthy of that good opinion which I earnestly covet.

To you, Madam, I am indebted for many instances of spontaneous kindness, and to your influence I owe frequent opportunities of representing the claims of my oppressed race. I should not have felt emboldened to attempt the authorship of this Volume, had it not been for a conviction, sustained by unmistakable tokens, that in all classes, from the prince to the peasant, there is a chord of sympathy which vibrates to the appeals of my suffering people.

Before your Grace can see these lines, I shall be again traversing the great Atlantic. Will you, Madam, pardon this utterance of the deep-felt sentiment of a grateful heart, which can only find indulgence and relief in the humble dedication of this Volume to you, as my honoured patroness, and the generous friend of the Negro people in all lands?

I am not versed in the language of courts or the etiquette of the peerage; but my heart is warm with gratitude, and my pen can but faintly express the sense of obligations I shall long cherish toward your noble House and the illustrious members of your Grace's family, from whom I have received many undeserved kindnesses.

I have the honour to be, Madam,

Your Grace's most obedient and grateful Servant,

SAMUEL RINGGOLD WARD.

LONDON, 31st October, 1855.Page v

PREFACE.

THE idea of writing some account of my travels was first suggested to me by a gentleman who has not a little to do with the bringing out of this work. The Rev. Dr. Campbell also encouraged the suggestion. I then thought that a series of letters in a newspaper would answer the purpose. Circumstances over which I had no control placed it beyond my power to accomplish the design in that form of publication.

A few months ago I was requested to spend an evening with some ardent friends of the Negro race, by the arrangement of Mrs. Massie, at her house, Upper Clapton. Her zeal and constancy in behalf of the American Slave are well known on both sides of the Atlantic. Nor is there, I believe, a more earnest friend of my kindred race than is her husband. With him I have repeatedly taken counsel on the best modes of serving our cause. Late in August last, Dr. Massie urged on me the propriety of preparing a volume which might remain as a parting memorial of my visit to England, and serve to embody and perpetuate the opinions and arguments I had often employed to promote

Page vi

the work of emancipation. Peter Carstairs, Esq., of Madras, being present, cordially and frankly encouraged the project; and other friends, in whose judgment I had confidence, expressed their warmest approval. My publisher has generously given every facility for rendering the proposal practicable. To him I owe my warmest obligations for the promptitude and elegance with which the Volume has been prepared.

I do not think the gentlemen who advised it were quite correct in anticipating that so much would be acceptable, in a Book from me. I should have gone about it with much better courage if I had not felt some fears on this point. However, amidst many apprehensions of imperfection, I place it before the reader, begging him to allow me a word by way of apology. I was obliged to write in the midst of most perplexing, most embarrassing, private business, and had not a solitary book or paper to refer to, for a fact or passage; my brain alone had to supply all I wished to compose or compile. Time, too, was very limited. Under these circumstances, that I should have committed some slight inaccuracies, will not appear very strange, though I trust they are not very great or material. I beg the reader generously to forgive the faults he detects, and to believe that my chief motive in writing is the promotion of that cause in whose service I live. I hope that this Book will not be looked upon as a specimen of what a well educated Negro could do, nor as a fair representation

Page vii

of what Negro talent can produce--knowing that, with better materials, more time, and in more favourable circumstances, even I could have done much better; and knowing also, that my superiors among my own people would have written far more acceptably.

It will be seen that I have freely made remarks upon other things than slavery, and compared my own with those of other peoples. I did the former as a Man, the latter as a Negro. As a Negro, I live and therefore write for my people; as a Man, I freely speak my mind upon whatever concerns me and my fellow men. If any one be disappointed or offended at that, I shall regret it; all the more, as it is impossible for me to say that, in like circumstances, I should not do just the same again.

The reader will not find the dry details of a journal, nor any of my speeches or sermons. I preferred to weave into the Work the themes upon which I have spoken, rather than the speeches themselves. The Work is not a literary one, for it is not written by a literary man; it is no more than its humble title indicates--the Autobiography of a Fugitive Negro. In what sense I am a fugitive, will appear on perusal of my personal and family history.

S. R. W.

RADLEY'S HOTEL, 31st October, 1855.

Page ix

CONTENTS.

- CHAPTER I.

- FAMILY HISTORY . . . . .3

- CHAPTER II.

- PERSONAL HISTORY . . . . .14

- CHAPTER III.

- THE FUGITIVES FROM SLAVERY . . . . .21

- CHAPTER IV.

- STRUGGLES AGAINST THE PREJUDICE OF COLOUR . . . . .28

AUTOBIOGRAPHY

- CHAPTER I.

- ANTI-SLAVERY: WHAT? . . . . .37

Page x - CHAPTER II.

- WORK BEGUN . . . . .44

- CHAPTER III.

- THE FIELD OCCUPIED . . . . .52

- CHAPTER IV.

- THE ISSUE CONTEMPLATED . . . . .61

- CHAPTER V.

- THE POLITICAL QUESTION . . . . .73

- CHAPTER VI.

- THE WHITE CHURCH AND COLOURED PASTOR . . . . .79

- CHAPTER VII.

- TERMINUS OF LABOURS IN THE UNITED STATES . . . . .102

ANTI-SLAVERY LABOURS.

PART I.--UNITED STATES.

- CHAPTER I.

- FIRST IMPRESSIONS: REASONS FOR LABOURS . . . . .133

- CHAPTER II.

- RESISTANCE TO SLAVE POLICY . . . . .154

Page xi - CHAPTER III.

- FUGITIVES EVINCE TRUE HEROISM . . . . .169

- CHAPTER IV.

- CANADIAN FREEMAN . . . . .189

PART II.--CANADA.

- CHAPTER I.

- VOYAGE, ARRIVAL, ETC. . . . . .227

- CHAPTER II.

- COMMENCEMENT OF LABOUR IN ENGLAND . . . . .243

- CHAPTER III.

- PRO-SLAVERY MEN IN ENGLAND . . . . .256

- CHAPTER IV.

- BRITISH ABOLITIONISM . . . . .289

- CHAPTER V.

- INCIDENTS, ETC. . . . . .304

Page xii - CHAPTER VI.

- SCOTLAND . . . . .330

- CHAPTER VII.

- IRELAND . . . . .360

- CHAPTER VIII.

- WALES . . . . .385

- CHAPTER IX.

- GRATEFUL REMINISCENCES--CONCLUSION . . . . .398

PART III.--GREAT BRITAIN.

Page 1

AUTOBIOGRAPHY.

Page 3

AUTOBIOGRAPHY.

CHAPTER I.

FAMILY HISTORY.

I WAS born on the 17th October, 1817, in that part of the State of Maryland, U. S., commonly called the Eastern Shore. I regret that I can give no accurate account of the precise location of my birthplace. I may as well state now the reason of my ignorance of this matter. My parents were slaves. I was born a slave. They escaped, and took their then only child with them. I was not then old enough to know anything about my native place; and as I grew up, in the State of New Jersey, where my parents lived till I was nine years old, and in the State of New York subsequently, where we lived for many years, my parents were always in danger of being arrested and re-enslaved. To avoid this, they took every possible caution: among their measures of caution was the keeping of the children quite ignorant of their birthplace, and of their condition, whether free or slave, when born; because children might, by the dropping of a single

Page 4

word, lead to the betrayal of their parents. My brother, however, was born in New Jersey; and my parents, supposing (as is the general presumption) that to be born in a free State is to be born free, readily allowed us to tell where my brother was born; but my birthplace I was neither permitted to tell nor to know. Hence, while the secresy and mystery thrown about the matter led me, most naturally, to suspect that I was born a slave, I never received direct evidence of it, from either of my parents, until I was four-and-twenty years of age; and then my mother informed my wife, in my absence. Generous reader, will you therefore kindly forgive my inability to say exactly where I was born; what gentle stream arose near the humble cottage where I first breathed--how that stream sparkled in the sunlight, as it meandered through green meadows and forests of stately oaks, till it gave its increased self as a contribution to the Chesapeake Bay--if I do not tell you the name of my native town and county, and some interesting details of their geographical, agricultural, geological, and revolutionary history--if I am silent as to just how many miles I was born from Baltimore the metropolis, or Annapolis the capital, of my native State? Fain would I satisfy you in all this; but I cannot, from sheer ignorance. I was born a slave--where? Wherever it was, it was

Page 5

where I dare not be seen or known, lest those who held my parents and ancestors in slavery should make a claim, hereditary or legal, in some form, to the ownership of my body and soul.

My father, from what I can gather, was descended from an African prince. I ask no particular attention to this, as it comes to me simply from tradition--such tradition as poor slaves may maintain. Like the sources of the Nile, my ancestry, I am free to admit, is rather difficult of tracing. My father was a pure-blooded negro, perfectly black, with woolly hair; but, as is frequently true of the purest negroes, of small, handsome features. He was about 5 feet 10 inches in height, of good figure, cheerful disposition, bland manners, slow in deciding, firm when once decided, generous and unselfish to a fault; and one of the most consistent, simple-hearted, straightforward Christians, I ever knew. What I have grouped together here concerning him you would see in your first acquaintance with him, and you would see the same throughout his entire life. Had he been educated, free, and admitted to the social privileges in early life for which nature fitted him, and for which even slavery could not, did not, altogether unfit him, my poor crushed, outraged people would never have had nor needed a better representation of themselves--a better specimen of the black gentleman.

Page 6

Yes: among the heaviest of my maledictions against slavery is that which it deserves for keeping my poor father--and millions like him--in the midnight and dungeon of the grossest ignorance. Cowardly system as it is, it does not dare to allow the slave access to the commonest sources of light and learning.

After his escape, my father learned to read, so that he could enjoy the priceless privilege of searching the Scriptures. Supporting himself by his trade as a house painter, or whatever else offered (as he was a man of untiring industry), he lived in Cumberland County, New Jersey, from 1820 until 1826; in New York city from that year until 1838; and in the city of Newark, New Jersey, from 1838 until May 1851, when he died, at the age of 68.

In April I was summoned to his bedside, where I found him the victim of paralysis. After spending some few days with him, and leaving him very much better, I went to Pennsylvania on business, and returned in about ten days, when he appeared still very comfortable; I then, for a few days, left him. My mother and I knew that another attack was to be feared--another, we knew too well, would prove fatal; but when it would occur was of course beyond our knowledge; but we hoped for the best. My father and I talked very freely of his death. He had always maintained that a Christian ought

Page 7

to have his preparation for his departure made, and completed in Christ, before death, so as when death should come he should have nothing to do BUT TO DIE. "That," said my father, "is enough to do at once: let repenting, believing, everything else, be sought at a proper time; let dying alone be done at the dying time." In my last conversation with him he not only maintained, but he felt, the same. Then, he seemed as if he might live a twelvemonth; but eight-and-forty hours from that time, as I sat in the Rev. A. G. Beeman's pulpit, in New Haven, after the opening services, while singing the hymn which immediately preceded the sermon, a telegraphic despatch was handed me, announcing my father's death. I begged Mr. Beeman to preach; his own feelings were such, that he could not, and I was obliged to make the effort. No effort ever cost me so much. Have I trespassed upon your time too much by these details? Forgive the fondness of the filial, the bereaved, the fatherless.

My mother was a widow at the time of her marriage with my father, and was ten years his senior. I know little or nothing of her early life: I think she was not a mother by her first marriage. To my father she bore three children, all boys, of whom I am the second. Tradition is my only authority for my maternal ancestry: that authority saith, that on the paternal side my mother

Page 8

descended from Africa. Her mother, however, was a woman of light complexion; her grandmother, a mulattress; her great-grandmother, the daughter of an Irishman, named Martin, one of the largest slaveholders in Maryland--a man whose slaves were so numerous, that he did not know the number of them. My mother was of dark complexion, but straight silklike hair; she was a person of large frame, as tall as my father, of quick discernment, ready decision, great firmness, strong will, ardent temperament, and of deep, devoted, religious character. Though a woman, she was not of so pleasing a countenance as my father, and I am thought strongly to resemble her. Like my father, she was converted in early life, and was a member of the Methodist denomination (though a lover of all Christian denominations) until her death. This event, one of the most afflictive of my life, occurred on the first day of September, 1853, at New York. Since my father's demise I had not seen her for nearly a year; when, being about to sail for England, at the risk of being apprehended by the United States' authorities for a breach of their execrable republican Fugitive Slave Law, I sought my mother, found her, and told her I was about to sail at three p.m., that day (April 20th, 1853), for England. With a calmness and composure which she could always command when emergencies

Page 9

required it, she simply said, in a quiet tone, "To England, my son!" embraced me, commended me to God, and suffered me to depart without a murmur. It was our last meeting. May it be our last parting! For the kind sympathy shown me, upon my reception of the melancholy news of my mother's decease, by many English friends, I shall ever be grateful: the recollection of that event, and the kindness of which it was the occasion, will dwell together in my heart while reason and memory shall endure.

In the midst of that peculiarly bereaved feeling inseparable from realizing the thought that one is both fatherless and motherless, it was a sort of melancholy satisfaction to know that my dear parents were gone beyond the reach of slavery and the Fugitive Law. Endangered as their liberty always was, in the free Northern States of New York and New Jersey--doubly so after the law of 1851--I could but feel a great deal of anxiety concerning them. I knew that there was no living claimant of my parents' bodies and souls; I knew, too, that neither of them would tamely submit to re-enslavement: but I also knew that it was quite possible there should be creditors, or heirs at law; and that there is no State in the American Union wherein there were not free and independent democratic republicans, and soi-disant Christians,

Page 10

"ready, aye ready " to aid in overpowering and capturing a runaway, for pay. But when God was pleased to take my father in 1851, and my mother in 1853, I felt relief from my greatest earthly anxiety. Slavery had denied them education, property, caste, rights, liberty; but it could not deny them the application of Christ's blood, nor an admittance to the rest prepared for the righteous. They could not be buried in the same part of a common graveyard, with whites, in their native country; but they can rise at the sound of the first trump, in the day of resurrection. Yes, reader: we who are slaveborn derive a comfort and solace from the death of those dearest to us, if they have the sad misfortune to be BLACKS and AMERICANS, that you know not. God forbid that you or yours should ever have occasion to know it!

My eldest brother died before my birth: my youngest brother, Isaiah Harper Ward, was born April 5th, 1822, in Cumberland County, New Jersey; and died at New York, April 16th, 1838, in the triumphs of faith. He was a lad partaking largely of my father's qualities, resembling him exceedingly. Being the youngest of the family, we all sought to fit him for usefulness, and to shield him from the thousand snares and the ten thousand forms of cruelty and injustice which the unspeakably cruel prejudice of the whites visits upon the

Page 11

head and the heart of every black young man, in New York. To that end, we secured to him the advantages of the Free School, for coloured youths, in that city-- advantages which, I am happy to say, were neither lost upon him nor unappreciated by him. Upon leaving school he commenced learning the trade of a printer, in the office of Mr. Henry R. Piercy, of New York--a gentleman who, braving the prejudices of his craft and of the community, took the lad upon the same terms as those upon which he took white lads: a fact all the more creditable to Mr. Piercy, as it was in the very teeth of the abominably debased public sentiment of that city (and of the whole country, in fact) on this subject. But ere Isaiah had finished his trade, he suddenly took a severe cold, which resulted in pneumonia, and--in death.

I expressed a doubt, in a preceding page, as to the legal validity of my brother's freedom. True, he was born in the nominally Free State of New Jersey; true, the inhabitants born in Free States are generally free. But according to slave law, "the child follows the condition of the mother, during life." My mother being born of a slave woman, and not being legally freed, those who had a legal claim to her had also a legal claim to her offspring, wherever born, of whatever paternity. Besides, at that time New Jersey had not entirely ceased to be

Page 12

a Slave State. Had my mother been legally freed before his birth, then my brother would have been born free, because born of a free woman. As it was, we were all liable at any time to be captured, enslaved, and re-enslaved--first, because we had been robbed of our liberty; then, because our ancestors had been robbed in like manner; and, thirdly and conclusively, in law, because we were black Americans.

I confess I never felt any personal fear of being retaken--primarily because, as I said before, I knew of no legal claimants; but chiefly because I knew it would be extremely difficult to identify me. I was less than three years old when brought away: to identify me as a man would be no easy matter. Certainly, slaveholders and their more wicked Northern parasites are not very particularly scrupulous about such matters; but still, I never had much fear. My private opinion is, that he who would have enslaved me would have "caught a Tartar": for my peace principles never extended so far as to either seek or accept peace at the expense of liberty--if, indeed, a state of slavery can by any possibility be a state of peace.

I beg to conclude this chapter on my family history by adding, that my father had a cousin, in New Jersey, who had escaped from slavery. In the spring of 1826 he was cutting down a tree, which accidentally fell upon him, breaking both

Page 13

thighs. While suffering from this accident his master came and took him back into Maryland. He continued lame a very great while, without any apparent signs of amendment, until one fine morning he was gone! They never took him again.

Two of my father's nephews, who had escaped to New York, were taken back in the most summary manner, in 1828. I never saw a family thrown into such deep distress by the death of any two of its members, as were our family by the re-enslavement of these two young men. Seven-and-twenty years have past, but we have none of us heard a word concerning them, since their consignment to the living death, the temporal hell, of American slavery.

Some kind persons who may read these pages will accuse me of bitterness towards Americans generally, and slaveholders particularly: indeed, there are many professed abolitionists, on both sides of the Atlantic, who have no idea that a black man should feel towards and speak of his tormenters as a white man would concerning his. But suppose the blacks had treated your family in the manner the Americans have treated mine, for five generations: how would you write about these blacks, and their system of bondage? You would agree with me, that the 109th Psalm, from the 5th to the 21st verses inclusive, was written almost purposely for them.

Page 14

CHAPTER II.

PERSONAL HISTORY.

I HAVE narrated when and where I was born, as far as I know. It seems that when young I was a very weakly child, whose life for the first two years and a half appeared suspended upon the most fragile fibre of the most delicate cord. It is not probable that any organic or constitutional disease was afflicting me, but a general debility, the more remarkable as both my parents were robust, healthy persons. Happily for me, my mother was permitted to "hire her time," as it is called in the South--i.e., she was permitted to do what she pleased, and go where she pleased, provided she paid to the estate a certain sum annually. This she found ample means of doing, by her energy, ingenuity, and economy. My mother was a good financier (O that her mantle had fallen on me!) She paid the yearly hire, and pocketed a surplus, wherewith she did much to add to the comforts of her husband and her sickly child. So long and so hopeless was my illness, that the parties owning us feared I could not

Page 15

be reared for the market--the only use for which, according to their enlightened ideas, a young negro could possibly be born or reared; their only hope was in my mother's tenderness. Yes: the tenderness of a mother, in that intensely FREE Country, is a matter of trade, and my poor mother's tender regard for her offspring had its value in dollars and cents.

When I was about two years old (so my mother told my wife), my father, for some trifling mistake or fault, was stabbed in the fleshy part of his arm, with a penknife: the wound was the entire length of the knife blade. On another occasion he received a severe flogging, which left his back in so wretched a state that my mother was obliged to take peculiar precaution against mortification. This sort of treatment of her husband not being relished by my mother, who felt about the maltreatment of her husband as any Christian woman ought to feel, she put forth her sentiments, in pretty strong language. This was insolent. Insolence in a negress could not be endured--it would breed more and greater mischief of a like kind; then what would become of wholesome discipline? Besides, if so trifling a thing as the mere marriage relation were to interfere with the supreme proprietor's right of a master over his slave, next we should hear that slavery must give way before marriage! Moreover, if a negress may be allowed free speech, touching the flogging of a

Page 16

negro, simply because that negro happened to be her husband, how long would it be before some such claim would be urged in behalf of some other member of a negro family, in unpleasant circumstances? Would this be endurable, in a republican civilised community, A. D. 1819? By no means. It would sap the very foundation of slavery--it would be like "the letting out of water": for let the principle be once established that the negress Anne Ward may speak as she pleases about the flagellation of her husband, the negro William Ward, as a matter of right, and like some alarming and death-dealing infection it would spread from plantation to plantation, until property in husbands and wives would not be worth the having. No, no: marriage must succumb to slavery, slavery must reign supreme over every right and every institution, however venerable or sacred; ergo, this free-speaking Anne Ward must be made to fell the greater rigours of the domestic institution. Should she be flogged? that was questionable. She never had been whipped, except, perhaps, by her parents; she was now three-and-thirty years old--rather late for the commencement of training; she weighed 184 lbs. avoirdupoise; she was strong enough to whip an ordinary-sized man; she had as much strength of will as of mind; and what did not diminish the awkwardness of the case was, she

Page 17

gave most unmistakeable evidences of "rather tall resistance," in case of an attack. Well, then, it were wise not to risk this; but one most convenient course was left to them, and that course they could take with perfect safety to themselves, without yielding one hair's breadth of the rights and powers of slavery, but establishing them--they could sell her, and sell her they would: she was their property, and like any other stock she could be sold, and like any other unruly stock she should be brought to the market.

However, this sickly boy, if practicable, must be raised for the auction mart. Now, to sell his mother immediately, depriving him of her tender care, might endanger his life, and, what was all-important in his life, his saleability. Were it not better to risk a little from the freedom of this woman's tongue, than to jeopardize the sale of this article? Who knows but, judging from the pedigree, it may prove to be a prime lot--rising six feet in length, and weighing two hundred and twenty pounds, more or less, some day? To ask these questions was to answer them; there was no resisting the force of such valuable and logical considerations. Therefore the sale was delayed; the young animal was to run awhile longer with his--(I accommodate myself to the ideas and facts of slavery, and use a corresponding nomenclature)

Page 18

--dam. Thus my illness prevented the separation of my father and my mother from each other, and from their only child. How God sometimes makes the afflictions of His poor, and the very wickedness of their oppressors, the means of blessing them! But how slender the thread that bound my poor parents together! the convalescence of their child, or his death, would in all seeming probability snap it asunder. What depths of anxiety must my mother have endured! How must the reality of his condition have weighed down the fond heart of my father, concerning their child! Could they pray for his continued illness? No; they were parents. Could they petition God for his health? Then they must soon be parted for ever from each other and from him, were that prayer answered. Ye whose children are born free, because you were so born, know but little of what this enslaved pair endured, for weeks and months, at the time to which I allude.

At length a crisis began to appear: the boy grew better. God's blessing upon a mother's tender nursing prevailed over habitual weakness and sickness. The child slept better; he had less fever; his appetite returned; he began to walk without tottering, and seemed to give signs of the cheerfulness he inherited from his father, and the strength of frame (and, to tell truth, of will also)

Page 19

imparted by his mother. Were not the owners right in their "calculations"? Had they not decided and acted wisely, in a business point of view? The dismal prospect before them, connected with the returning health of their child, damped the joy which my parents, in other circumstances, and in a more desirable country, would have felt in seeing their child's improved state. But the more certain these poor slaves became that their child would soon be well, the nearer approached the time of my mother's sale. Motherlike, she pondered all manner of schemes and plans to postpone that dreaded day. She could close her child's eyes in death, she could follow her husband to the grave, if God should so order; but to be sold from them to the far-off State of Georgia, the State to which Maryland members of Churches sold their nominal fellow Christians-- sometimes their own children, and other poor relations--that was more than she could bear. Submission to the will of God was one thing, she was prepared for that, but submission to the machinations of Satan was quite another thing; neither her womanhood nor her theology could be reconciled to the latter. Sometimes pacing the floor half the night with her child in her arms--sometimes kneeling for hours in secret prayer to God for deliverance --sometimes in long earnest consultation with my

Page 20

father as to what must be done in this dreaded emergency--my mother passed days, nights, and weeks of anguish which wellnigh drove her to desperation. But a thought flashed upon her mind: she indulged in it. It was full of danger; it demanded high resolution, great courage, unfailing energy, strong determination; it might fail. But it was only a thought, at most only an indulged thought, perhaps the fruit of her very excited state, and it was not yet a plan; but, for the life of her, she could not shake it off. She kept saying to herself, "supposing I should"--Should what? She scarcely dare say to herself, what. But that thought became familiar, and welcome, and more welcome; it began to take another, a more definite form. Yes; almost ere she knew, it had incorporated itself with her will, and become a resolution, a determination. "William," said she to my father, "we must take this child and run away." She said it with energy; my father felt it. He hesitated; he was not a mother. She was decided; and when decided, she was decided with all consequences, conditions, and contingencies accepted. As is the case in other families where the wife leads, my father followed my mother in her decision, and accompanied her in--I almost said, her hegira.

Page 21

CHAPTER III.

THE FUGITIVES FROM SLAVERY.

WHAT was the precise sensation produced by the departure of my parents, in the minds of their owners--how they bore it, how submissively they spoke of it, how thoughtfully they followed us with their best wishes, and so forth, I have no means of knowing: information on these questionable topics was never conveyed to us in any definite, systematic form. Be this as it may, on a certain evening, without previous notice, my mother took her child in her arms, and stealthily, with palpitating heart, but unfaltering step and undaunted courage, passed the door, the outer gate, the adjoining court, crossed the field, and soon after, followed by my father, left the place of their former abode, bidding it adieu for ever. I know not their route; but in those days the track of the fugitive was neither so accurately scented nor so hotly pursued by human sagacity, or the scent of kindred bloodhounds, as now, nor was slave-catching so complete and regular a system as it is now. Occasionally a slave escaped, but seldom

Page 22

in such numbers as to make it needful either to watch them very closely when at home, or to trace them systematically when gone. Indeed, our slave-catching professionals may thank the slaves for the means by which they earn their dishonourable subsistence; for if the latter had never reduced running away to system, the former had never been needed, and therefore never employed at their present wretched occupation, as a system. " 'Tis an ill wind that blows nobody good."

At the time of my parents' escape it was not always necessary to go to Canada; they therefore did as the few who then escaped mostly did--aim for a Free State, and settle among Quakers. This honoured sect, unlike any other in the world, in this respect, was regarded as the slave's friend. This peculiarity of their religion they not only held, but so practised that it impressed itself on the ready mind of the poor victim of American tyranny. To reach a Free State, and to live among Quakers, were among the highest ideas of these fugitives; accordingly, obtaining the best directions they could, they set out for Cumberland County, in the State of New Jersey, where they had learned slavery did not exist--Quakers lived in numbers, who would afford the escaped any and every protection consistent with their peculiar tenets--and where a number of blacks lived, who in cases of emergency

Page 23

could and would make common cause with and for each other. Then these attractions of Cumberland were sufficient to determine their course.

I do not think the journey could have been a very long one: but it must be travelled on foot, in some peril, and with small, scanty means, next to nothing; and with the burden (though they felt it not) of a child, nearly three years old, both too young and too weakly to perform his own part of the journey. One child they had laid in the grave; now their only one must be rescued from a fate worse than ten thousand deaths. Upon this rescue depended their continued enjoyment of each other's society. The many past evils inseparable from a life of slavery, their recently threatened separation, and the dangers of this exodus, served to heighten that enjoyment, and doubly to endear each to the other; and the thought that they might at length be successful, and as free husband and wife bring up their child in the nurture and admonition of the Lord, according to the best of their ability, stimulated them to fresh courage and renewed endurance. Step by step, day after day, and night after night, with their infant charge passed alternately from the arms of the one to those of the other; they wended on their way, driven by slavery, drawn and stimulated by the hope of freedom, and all the while trusting in and committing themselves to Him who

Page 24

is God of the oppressed. I can just remember one or two incidents of the journey; they now stand before me, associated with my earliest recollections of maternal tenderness and paternal care: and it seems to me, now that they are both gathered with the dead, that I would rather forget any facts of my childhood than those connected with that, to me, in more respects than one, all-important journey.

Struggling against many obstacles, and by God's help surmounting them, they made good progress until they had got a little more than midway their journey, when they were overtaken and ordered back by a young man on horseback, who, it seems, lived in the neighbourhood of my father's master. The youth had a whip, and some other insignia of slaveholding authority; and knowing that these slaves had been accustomed from childhood to obey the commanding voice of the white man, young or old, he foolishly fancied that my parents would give up the pursuit of freedom for themselves and their child at his bidding. They thought otherwise; and when he dismounted, for the purpose of enforcing authority and compelling obedience by the use of the whip, he received so severe a flogging at the hands of my parents as sent him home nearly a cripple. He conveyed word as to our flight, but prudently said he received his hurts by

Page 25

his horse plunging, and throwing him suddenly against a large tree. Through this young man our owners got at the bottom of their loss. There was the loss of the price of my mother, the loss of my present and prospective self, and, what they had had no reason before to suspect, the loss of my father! Some say it was the commencement of a series of adversities from which neither the estate nor the owners ever afterwards recovered. I confess to sufficient selfishness never to have shed a tear, either upon hearing this or in subsequent reflections upon it.

After this nothing serious befell our party, and they safely arrived at Greenwich, Cumberland County, early in the year 1820. They found, as they had been told, that at Springtown, and Bridgetown, and other places, there were numerous coloured people; that the Quakers in that region were truly, practically friendly, "not loving in word and tongue," but in deed and truth; and that there were no slaveholders in that part of the State, and when slave-catchers came prowling about the Quakers threw all manner of peaceful obstacles in their way, while the Negroes made it a little too hot for their comfort.

We lived several years at Waldron's Landing, in the neighbourhood of the Reeves, Woods, Bacons, and Lippineutts, who were among my father's very

Page 26

best friends, and whose children were among my schoolfellows. However, in the spring and summer of 1826, so numerous and alarming were the depredations of kidnapping and slave-catching in the neighbourhood, that my parents, after keeping the house armed night after night, determined to remove to a place of greater distance and greater safety. Being accommodated with horses and a waggon by kind friends, they set out with my brother in their arms for New York City, where they arrived on the 3rd day of August, 1826, and lodged the first night with relations, the parents of the Rev. H. H. Garnett, now of Westmoreland, Jamaica. Here we found some 20,000 coloured people. The State had just emancipated all its slaves--viz., on the fourth day of the preceding month--and it was deemed safer to live in such a city than in a more open country place, such as we had just left. Subsequent events, such as the ease with which my two relatives were taken back in 1828--the truckling of the mercantile and the political classes to the slave system--the large amount of slaveholding property owned by residents of New York--and, worst, basest, most diabolical of all, the cringing, canting, hypocritical friendship and subserviency of the religious classes to slavery--have entirely dissipated that idea.

I look upon Greenwich, New Jersey, the place

Page 27

of my earliest recollections, very much as most persons remember their native place. There I followed my dear father up and down his garden, with fond childish delight; the plants, shrubs, flowers, &c., I looked upon as of his creation. There he first taught me some valuable lessons--the use of the hoe, to spell in three syllables, and to read the first chapter of John's Gospel, and my figures; then, having exhausted his literary stock upon me, he sent me to school. There I first read the Bible to my beloved mother, and read in her countenance (what I then could not read in the book) what that Bible was to her. Were my native country free, I could part with any possession to become the owner of that, to me, most sacred spot of earth, my father's old garden. Had I clung to the use of the hoe, instead of aspiring to a love of books, I might by this time have been somebody, and the reader of this volume would not have been solicited by this means to consider the lot of the oppressed American Negro.

Page 28

CHAPTER IV.

STRUGGLES AGAINST THE PREJUDICE OF COLOUR.

I GREW up in the city of New York as do the children of poor parents in large cities too frequently. I was placed at a public school in Mulberry Street, taught by Mr. C. C. Andrew, and subsequently by Mr. Adams, a Quaker gentleman, from both of whom I received great kindness. Dr. A. Libolt, my last preceptor in that school, placed me under lasting obligations. Poverty compelled me to work, but inclination led me to study; hence I was enabled, in spite of poverty, to make some progress in necessary learning. Added to poverty, however, in the case of a black lad in that city, is the ever-present, ever-crushing Negro-hate, which hedges up his path, discourages his efforts, damps his ardour, blasts his hopes, and embitters his spirits.

Some white persons wonder at and condemn the tone in which some of us blacks speak of our oppressors. Such persons talk as if they knew but little of human nature, and less of Negro

Page 29

character, else they would wonder rather that, what with slavery and Negro-hate, the mass of us are not either depressed into idiocy or excited into demons. What class of whites, except the Quakers, ever spoke of their oppressors or wrongdoers as mildly as we do? This peculiarly American spirit (which Englishmen easily enough imbibe, after they have resided a few days in the United States) was ever at my elbow. As a servant, it denied me a seat at the table with my white fellow servants; in the sports of childhood and youth, it was ever disparagingly reminding me of my colour and origin; along the streets it ever pursued, ever ridiculed, ever abused me. If I sought redress, the very complexion I wore was pointed out as the best reason for my seeking it in vain; if I desired to turn to account a little learning, in the way of earning a living by it, the idea of employing a black clerk was preposterous--too absurd to be seriously entertained. I never knew but one coloured clerk in a mercantile house. Mr. W. L. Jeffers was lowest clerk in a house well known in Broad Street, New York; but he never was advanced a single grade, while numerous white lads have since passed up by him, and over him, to be members of the firm. Poor Jeffers, till the day of his death, was but one remove above the porter. So, if I sought a trade, white apprentices would

Page 30

leave if I were admitted; and when I went to the house of God, as it was called, I found all the Negro-hating usages and sentiments of general society there encouraged and embodied in the Negro pew, and in the disallowing Negroes to commune until all the whites, however poor, low, and degraded, had done. I know of more than one coloured person driven to the total denial of all religion, by the religious barbarism of white New Yorkers and other Northern champions of the slaveholder.

However, at the age of sixteen I found a friend in George Atkinson Ward, Esq., from whom I received encouragement to persevere, in spite of Negro-hate. In 1833 I became a clerk of Thomas L. Jennings, Esq., one of the most worthy of the coloured race; subsequently my brother and I served David Ruggles, Esq., then of New York, late of Northampton, Massachusetts, now no more.

In 1833 it pleased God to answer the prayers of my parents, in my conversion. My attention being turned to the ministry, I was advised and recommended by the late Rev. G. Hogarth, of Brooklyn, to the teachership of a school for coloured children, established by the munificence of the late Peter Remsen, Esq., of New Town, N.Y. The most distinctive thing I can say of myself, in this my first attempt at the profession of a pedagogue, is

Page 31

that I succeeded Mr., now the Rev. Dr., Pennington. I afterwards taught for two-and-a-half years in Newark, New Jersey, where I was living in January 1838, when I was married to Miss Reynolds, of New York; and in October 1838 Samuel Ringgold Ward the younger was born, and I became, "to all intents, constructions, and purposes whatsoever," a family man, aged twenty-one years and twelve days.

In May, 1839, I was licensed to preach the gospel by the New York Congregational Association, assembled at Poughkeepsie. In November of the same year, I became the travelling agent of first the American and afterwards the New York Anti-slavery Society; in April, 1841, I accepted the unanimous invitation of the Congregational Church of South Butler, Wayne Co., N.Y., to be their pastor; and in September of that year I was publicly ordained and inducted as minister of that Church. I look back to my settlement among that dear people with peculiar feelings. It was my first charge: I there first administered the ordinances of baptism and the Lord's supper, and there I first laid hands upon and set apart a deacon; there God honoured my ministry, in the conversion of many and in the trebling the number of the members of the Church, most of whom, I am delighted to know, are still walking in the light of

Page 32

God. The manly courage they showed, in calling and sustaining and honouring as their pastor a black man, in that day, in spite of the too general Negro-hate everywhere rife (and as professedly pious as rife) around them, exposing them as it did to the taunts, scoffs, jeers, and abuse of too many who wore the cloak of Christianity--entitled them to what they will ever receive, my warmest thanks and kindest love. But one circumstance do I regret, in connection with the two-and-a-half years I spent among them--that was, not the poverty against which I was struggling during the time, nor the demise of the darling child I buried among them: it was my exceeding great inefficiency, of which they seemed to be quite unconscious. Pouring my tears into their bosoms, I ask of them and of God forgiveness. I was their first pastor, they my first charge. Distance of both time and space has not yet divided us, and I trust will ever leave us one in heart and mind.

Having contracted a disease of the uvula and tonsils, which threatened to destroy my usefulness as a speaker, with great reluctance I relinquished that beloved charge in 1843, and in December of that year removed to Geneva, where I commenced the study of medicine with Doctors Williams and Bell. The skill of my preceptors, with God's blessing, prevailing over my disorder, I was enabled to

Page 33

speak occasionally to a small Church in Geneva, while residing there; and finally to resume public and continuous anti-slavery labours, in connection with the Liberty Party, in 1844. In 1846 I became pastor of the Congregational Church in Cortland Village, New York, where some of the most laborious of my services were rendered, and where I saw more of the foolishness, wickedness, and at the same time the invincibility, of American Negro-hate, than I ever saw elsewhere. Would that I had been more worthy of the kindness of those who invited me to that place--of those friends whom I had the good fortune to win while I lived there--especially of those who showed me the most fraternal kindness during the worst, longest illness I have suffered throughout life, and while passing through severe pecuniary troubles. My youngest son, William Reynolds Ward, is buried there; and there were born two of my daughters, Emily and Alice, the former deceased, the latter still living.

From Cortland we removed to Syracuse in 1851, whence, on account of my participating in the "Jerry rescue case," on the first day of October in that year, it became quite expedient to remove in some haste to Canada, in November. During the last few years of my residence in the United States I was editor and proprietor of two newspapers, both of which I survive, and in both of which

Page 34

I sunk every shred of my property. While at this business, it seemed necessary that I should know something of law. For this purpose, I commenced the reading of it: but I beg to say, that after smattering away, or teaching, law, medicine, divinity, and public lecturing, I am neither lawyer, doctor, teacher, divine, nor lecturer; and at the age of eight-and-thirty I am glad to hasten back to what my father first taught me, and from what I never should have departed--the tilling of the soil, the use of the hoe.

I beg to conclude this chapter by offering to all young men three items of advice, which my own experience has taught me:--

- 1. FIND YOUR OWN APPROPRIATE PLACE OF DUTY.

- 2. WHEN YOU HAVE FOUND IT, BY ALL MEANS KEEP IT.

- 3. IF EVER TEMPTED TO DEPART FROM IT, RETURN TO IT AS SPEEDILY AS POSSIBLE.

Page 35

ANTI-SLAVERY LABOURS, &c.

PART I.

UNITED STATES.

Page 37

ANTI-SLAVERY LABOURS, &c.

CHAPTER I.

ANTI-SLAVERY: WHAT?

IT may be thought that the biographical portion of this volume is brief and summary; but it will be seen, as we proceed, that some points, deserving more attention, belong more properly to other parts of the work. In proceeding to write about my anti-slavery labours, I may be allowed to give my own definition of them. I regard all the upright demeanour, gentlemanly bearing, Christian character, social progress, and material prosperity, of every coloured man, especially if he be a native of the United States, as, in its kind, anti-slavery labour. The enemies of the Negro deny his capacity for improvement or progress; they say he is deficient in morals, manners, intellect, and character. Upon that assertion they base the American doctrine, proclaimed with all effrontery, that the Negro is neither fit for nor entitled to the rights, immunities and privileges, which the same parties say belong naturally to all men; indeed, some of them go

Page 38

so far as to deny that the Negro belongs to the human family. In May, 1851, Dr. Grant, of New York, argued to this effect, to the manifest delight of one of the largest audiences ever assembled in Broadway Tabernacle. True, two coloured gentleman, one of whom was Frederic Douglass, Esq., refuted the abominable theory; but Dr. Grant left, it is to be feared, his impression upon the minds of too many, some of whom wished to believe him. A very learned divine in New Haven, Connecticut, declared, to the face of my honoured friend, Rev. S. E. Cornish, that "neither wealth nor education nor RELIGION could fit the Negro to live upon terms of equality with the white man." Another Congregational clergyman of Connecticut told the Writer, in the presence of the Rev. A. G. Beeman, that in his opinion, were Christ living in a house capable of holding two families, he would object to a black family in the adjoining apartments. Mr. Cunard objected to my taking a passage on any other terms--in a British steamer, be it remembered; and Mr. Cunard is an Englishman--than that I should not offend Americans by presenting myself at the cabin table d'hôte. I could number six Americans who left Radley's Hotel, while I was boarding there, because I was expected to eat in the same coffee-room with them, at a separate table, twenty feet distant from them, being ignorant

Page 39

of their presence. In but five of the American States are coloured persons allowed to vote on equal terms with whites. From social and business circles the Negro is entirely excluded--no, not that; he is not admitted--as a rule.

Now, surely, all this is not attributable to the fact that the Americans hold slaves, for the very worst of these things are done by non-slaveholders, in non-slaveholding States; and Englishmen, Irishmen, and Scotchmen, generally become the bitterest of Negro-haters, within fifteen days of their naturalization--some not waiting so long. Besides, in other slaveholding countries--Dutch Guiana, Brazil, Cuba, &c.--free Negroes are not treated thus, irrespective of character or condition. It is quite true that, as a rule, American slaveholders are the worst and the most cruel, both to their own mulatto children and to other slaves; it is quite true, that nowhere in the world has the Negro so bitter, so relentless enemies, as are the Americans; but it is not because of the existence of slavery, nor of the evil character or the lack of capacity on the part of the Negro. But, whatever is or is not the cause of it, there stands the fact; and this feeling is so universal that one almost regards 'American' and 'Negro-hater' as synonymous terms.

My opinion is, that much of this difference between the Anglo-Saxon on the one and his brother

Page 40

Anglo-Saxon on the other side of the Atlantic is to be accounted for in the very low origin of early American settlers, and the very deficient cultivation as compared with other nations, to which they have not attained. I venture this opinion upon the following considerations. The early settlers in many parts of America were the very lowest of the English population: the same class will abuse a Negro in England or Ireland now. The New England States were settled by a better class. In those States the Negro is best treated, excepting always the State of Connecticut. The very lowest of all the early settlers of America were the Dutch. These very same Dutch, as you find them now in the States of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania, out-American all Americans, save those of Connecticut, in their maltreatment of the free Negro. The middling and better classes of all Europe treat a black gentleman as a gentleman. Then step into the British American colonies, and you will find the lowest classes and those who have but recently arisen therefrom, just what the mass of Yankees are on this matter. Also, the best friends the Negro has in America are persons generally of the superior classes, and of the best origin. These are facts. The conclusion I draw from them may be erroneous, but it is submitted that it may be examined.

Page 41

We expect, generally, that the progress of Christianity in a country will certainly, however gradually, undermine and overthrow customs and usages, superstitions and prejudices, of an unchristian character. That this contempt of the Negro is unchristian, perhaps I shall be excused from stooping to argue. But, alas! pari passu with the spread of what the pulpit renders current as Christianity in my native country, is the growth, diffusion, and perpetuity of hatred to the Negro; indeed, one might be almost tempted to accredit the words of one of the most eloquent of Englishmen, who, more than twenty years ago, described it in few but forcible terms--"the Negro-hating Christianity." Religion, however, should be substituted for Christianity; for while a religion may be from man, and a religion from such an origin may be capable of hating, Christianity is always from God, and, like him, is love. "He who hateth his brother abideth in darkness." "Love is the fulfilling of the law." Surely it is with no pleasure that I say, from experience, deep-wrought conviction, that the oppression and the maltreatment of the hapless descendant of Africa is not merely an ugly excrescence upon American religion--not a blot upon it, not even an anomaly, a contradiction, and an admitted imperfection, a deplored weakness--a lamented form of indwelling, an easily

Page 42

besetting, sin; no, it is a part and parcel of it, a cardinal principle, a sine quâ non, a cherished defended keystone, a corner-stone, of American faith--all the more so as it enters into the practice, the everyday practice, of an overwhelming majority (equal to ninety-nine hundredths) of its professors, lay and clerical, of all denominations; not excepting, too, many of the Quakers! How these people will get on in Heaven, into which sovereign, abounding, divine mercy admits blacks as well as whites, I know not; but Heaven is not the only place to which either whites or blacks will enter after the judgment!

In view of such a conclusion, what is anti-slavery labour? Manifestly the refutation of all this miserable nonsense and heresy--for it is both. How is this to be done? Not alone by lecturing, holding anti-slavery conventions, distributing anti-slavery tracts, maintaining anti-slavery societies, and editing anti-slavery journals, much less by making a trade of these, for certain especial pets and favourites to profit by and in which to live in luxury; but, in connection with these labours, right and necessary in themselves, effective as they must be when properly pursued, the cultivation of all the upward tendencies of the coloured man. I call the expert black cordwainer, blacksmith, or other mechanic or artisan, the teacher, the lawyer, the

Page 43

doctor, the farmer, or the divine, an anti-slavery labourer; and in his vocation from day to day, with his hoe, hammer, pen, tongue, or lancet, he is living down the base calumnies of his heartless adversaries--he is demonstrating his truth and their falsity: indeed, all the labour which falls short of this--much more, such as does not tend in this direction--must, from the nature of the case and the facts and demands of the cause, be defective, lamentably defective, to use no stronger term. I shall be understood, I hope, then, if I include the chief facts of my life, whether in the editorial chair, in the pulpit, on the platform, pleading for this cause or that, in my anti-slavery labours. God helping me wherever I shall be, at home, abroad, on land or sea, in public or private walks, as a man, a Christian, especially as a black man, my labours must be anti-slavery labours, because mine must be an anti-slavery life.

Page 44

CHAPTER II.

WORK BEGUN.

I SHALL not inflict the dry details of a journal upon my readers. Treating of my labours in the American States, in this part I shall briefly speak of the incidents which in Providence led to my entering upon the lecturing field, those connected with my settlement in the ministry, and some events occurring in the course of both, and the reasons for the termination of those labours.

That the announcement of a meeting for the formation of an anti-slavery society should create a sensation among the coloured people of New York no one will wonder. Having been abused, and befooled, and slandered, disparaged, ridiculed, and traduced, by the Colonizationists, we could not but look on, first, with very great distrust upon any persons stepping forward with schemes professedly for our good. But a young printer had suffered imprisonment in Baltimore, for exposing there what Clarkson had long before exposed in Liverpool--viz., the paraphernalia of a systematic,

Page 45

authorized, lucrative slave trade; and this young man being released through the munificence of one of our then wealthiest Pearl Street merchants, we could not doubt the real motives of either of these. Garrison would not suffer imprisonment in our behalf, insincerely; Arthur Tappan would not liberate Garrison from imprisonment, on such a charge, at the cost of one thousand dollars, insincerely; indeed, we know too well that no white man would suffer for our sakes, without more than ordinary philanthropy. These gentlemen deserved, and they received, our confidence. In 1830 I heard, in New Haven, Connecticut, at the Temple Street Coloured Congregational Church, the Rev. Simeon S. Jocelyn preach. I learned that, when a young man, a bank-note engraver by trade, he studied theology and entered the ministry, on purpose to serve the coloured people. When a lecture was announced to be delivered on the subject of slavery by that gentleman, I was but too glad to hear him. I learned to love him as a child; I now have the honour of his friendship as a man. His was the first anti-slavery lecture I ever heard, and it was delivered in 1834. In the spring of the same year Professor E. Wright, jun., who had been in the enjoyment of a Professorship in a Western College, but relinquished it, and with it surrendered a salary of eleven hundred dollars

Page 46

for one of four hundred, that he might be at liberty to serve the anti-slavery cause, lectured upon the same subject. I was among his many delighted auditors. The same gentleman is now E. Wright, Esq., of Boston, the Douglas Jerrold of America. A lawyer well known to fame, David Paul Brown, Esq., of Philadelphia, was always ready to render his peerless services in defence of any person claimed as a slave. On the fourth day of July, 1834, this gentleman was invited to deliver an anti-slavery oration in Chatham Chapel, and, of course, the coloured people mustered in strong array to hear so well known a champion of freedom; but the meeting was dispersed by a mob, gathered and sustained by the leading commercial and political men and journals of that great city. It was Independence Day--a day, of all days, sacred to freedom. What Mr. Brown came to tell us was, that the principles, enunciated in few words, in the Declaration of Independence--"We hold these truths to be self-evident truths, that all men are created equal, and are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness"--applied as well to black men as to white men. This the aristocracy of New York could not endure; and therefore, just fifty-eight years from the very hour that the Declaration of 1776

Page 47

was made, the mob of the New York merchants broke up this assembly.

On the 7th of the same month the coloured people held a meeting in the same place, to listen to an address from one of the ablest of their number, Benjamin F. Hughes, Esq. That meeting was dispersed by a mob led by a person holding a lucrative political office in the city. This gentleman (I like to indulge in poetry sometimes) thought to do as he pleased with the blacks, kicking them about at will; and while Mr. Hughes was speaking, ordered other parties to come in and occupy the building. Seeing resistance made by some of the coloured people, and fearing he might receive a blow for a kick, he elevated a chair over his head, and stood witnessing the mêlée himself had begun, when Mr. Jinnings knocked him over with a well-aimed missile. Leaving his men to fight or run, as might seem wisest, this general of the mob escaped from a window 22 feet from the ground, injuring himself so as to keep his house for a fortnight--in his own person the leader of the mob and the only man injured in the affray. The blacks were victors; every white man was driven from the place. But while a few of us lingered, a reinforcement of the white belligerents came, and, finding some few lads of us in the place, they drove us out with a rush to the door. Then they

Page 48

commenced beating us in the most cowardly manner. The public watchman arrested the parties beaten instead of those committing the assault, and it was my lot to be among the former number. For the crime of being publicly assaulted by several white persons, I was locked up in the watchhouse throughout the night. Shortly after my imprisonment, four others were brought into the same cell by the officers of peace and justice, for the same crime. In the meantime the mob went to the house of Lewis Tappan, Esq., broke it open, sacked it, and burned the furniture. Mr. Tappan was brother and partner of the gentleman who liberated Garrison; he also believed in the Declaration of Independence; hence the mutilation and burning of his property. My oath of allegiance to the anti-slavery cause was taken in that cell on the 7th of July, 1834. In the morning we were brought before the police magistrate, with other prisoners. Those against whom no one appeared, or whom no one charged with any offence, were discharged. None appeared against us. The watchman who arrested us had no charge to bring: he simply said, in the chaste diction of a New York official, "Thur was a row in Chatham Chapel last night, and these niggers was there." The magistrate, a sample specimen of the New York Dogberry, abused us, and, instead of discharging us according

Page 49

to law and custom, remanded us to Bridewell, to give parties an opportunity of appearing against us. I never knew the same course taken in any other case. To Bridewell we went, and were put into a cell with nineteen others. In a most filthy state was that cell. All the occupants, besides my four companions, were charged with crime--one with killing a man; and though we were searched before we were incarcerated, this man had, and showed us, the knife with which he had inflicted the murder. The murderer, Johnson, had been fettered in the same cell, and we saw the chain by which he had been fastened to the floor. When the prison cup was offered us to drink from, and when the prison food was brought us, feeling our innocence and our dignity (lads of seventeen seldom lack the latter), we refused both. About ten o'clock, my father and G. A. Ward, Esq., procured my liberation, by paying the turnkey. As an innocent subject, unrighteously doomed to a felon's prison, without either accuser or trial, when liberated, I should have gone out free. My fellow prisoners were liberated soon after. That imprisonment initiated me into the anti-slavery fraternity.

In July, 1837, I was selected to deliver an oration before a Literary Society of which I was a member. It was my first public attempt at public speaking. Among those present was Lewis Tappan, Esq.

Page 50

In August of the same year I was invited to speak in the Broadway Tabernacle. In 1839 I was engaged in Poughkeepsie, as teacher of the Coloured Lancasterian School. Anxious to pursue further studies, I applied to one or two gentlemen for aid. One of them confessed himself but a beginner in one of the branches in which I had made some progress; and he soon after gave me a deeper wound, and more severe discouragement, than any other man ever did. A debate upon the peace question was to occur, in a hall of which this gentleman and I were joint proprietors for the time. I had another engagement to speak, at some distance from home, within a day or two of the time of the debate. This gentleman urged my return in time to participate in the discussion. I complied, went to the hall. A few only attended; and after a little conversation instead of a debate, it was concluded to form a Literary Society. My friend was requested to pass a paper for the names of such persons present as would enter such a society. He did not solicit my name. He came to me after the proceeding had terminated, and said, " Mr. Ward, you must have noticed that I did not hand the paper to you for your signature. I omitted you on purpose, because I saw that if your name was taken several of those present would bolt." Then, thought I, what is the use of my acting uprightly, seeking

Page 51

to win fame, and gaining it, if in this country a professed friend, a man who goes with me to the house of God, hearing me preach, visits my house, after all treads upon me to please his neighbours? My determination was formed to leave the country. I accordingly wrote to Mr. Burnley, of the Trinidad Legislature, a relation of the late Joseph Hume, Esq., M.P., who kindly encouraged my going to that island. I wrote also to Rev. Joshua Leavitt, asking for letters of recommendation. Mr. L. deprecated my leaving America, thinking I might be of some service to the anti-slavery cause. I wrote him again, bitterly stating my utter despair of doing anything for myself or my people amid so many discouragements. The reply I received was an appointment as agent of the American Anti-Slavery Society, to travel and lecture for them. I accepted the appointment, my commission being signed by Henry B. Stanton, Esq., who was then, and Hon. James Gillespie Birney, who yet professes to be, an abolitionist; these gentlemen being secretaries of that Society; in the same capacity they came to London, to attend the World's Anti-Slavery Convention of 1840. Thus was I introduced into the anti-slavery agency.

Page 52

CHAPTER III.

THE FIELD OCCUPIED.

IN November, 1839, I made my début as a lecturer. It cost me a great deal of effort and self-denial. My youthful wife and my infant boy I must leave, to go hundreds of miles, travelling in all weathers, meeting all sorts of people, combatting some of the most deeply seated prejudices, and in the majority of instances denied the ordinary courtesies of civilized life. I suffered more than can be here described. At length I considered that every Christian has not only a cross to bear, but his peculiar cross; and that God, not man, must judge and decide in what shape that cross must come: aye, and he too would give grace to bear it. Thus fortified, I went forth; and from that day to this I have never been able to see this travelling, homeless, wandering part of the work in any other light than a cross. No place can be a substitute for home, though the latter be a hovel, the former a palace. No observer can enter into one's inner feelings, live over again one's life, as does the loving wife. In sickness, in sorrow, to

Page 53

be away from home adds mountain weights to what the wanderer's bosom must bear; and I may as well add, that the poisoned tongue of censure--cool, deliberate, granite-hearted censure--censure from unbridled but professedly Christian tongues, to be found alike on both sides of the Atlantic, even among brethren and others--doth not diminish the rigour of the cross.

Still, with God's blessing I went forth, making my first speech at a private house, and afterwards speaking in public places until I become accustomed somewhat to the sound of my own voice, and a little skilled in the handling of the subject, receiving kind encouragement from one friend and another; until, being transferred to the service of the New York State Society in December 1839, I had the unspeakable pleasure of making the acquaintance of some of its most distinguished members and officers, and, at the same time, of avoiding official connection with the quarrels which divided the Anti-Slavery Society in 1840, and the subsequent dissensions among them.

This same December, 1839, was eventful as the month in which I became personally acquainted with Hon. Gerrit Smith, Rev. Beriah Green, and William Goodell, Esq.--three men whose peers are not to be found in New York or any other State.

Gerrit Smith had not then been sent to Congress,

Page 54

but he had shown himself every way qualified for the highest seat in any legislature, for the highest office in the gift of any people. Not that office would adorn or ennoble him, but that, in office as everywhere else, the majestic dignity of his mien, the easy, graceful perfection of his manners, his highly cultivated intellect, his rich and varied learning, his profoundly instructive conversation, his princely munificence, the natural stream springing in and flowing from a most benevolent heart--and, above all, his sweet, childlike, simple, earnest, constant piety, pervading his whole life and sparkling in all he says or does--these traits would have shed lustre upon any office, and have made their possessor the most admired and most attractive as they make him one of the very best of men. In spite of all that was said of this gentleman by his enemies during his short career in Congress, fourteen years after the time I speak of, the very bitterest of his foes--or, what is tantamount, the falsest of his professed friends--were obliged to acknowledge him to be one of the noblest of earth's noble sons.

Never shall I forget the first time I heard that model man speak. Standing erect, as he could stand no other way, with his large, manly frame, graceful figure and faultless mannerism, richly but plainly dressed, with a broad collar and black ribbon upon his neck (his invariable costume, whatever be

Page 55

the prevailing fashion), his look, with his broad intellectual face and towering forehead, was enough to charm any one not dead to all sense of the beautiful; and then, his rich, deep, flexible, musical voice, as capable of a thunder-tone as of a whisper--a voice to which words were suited, as it was suited to words; but, most of all, the words, thoughts, sentiments, truths and principles, he uttered--rendered me, and thousands more with me, unable to sit or stand in any quietness during his speech. This was in May, 1838. Mr. Smith was speaking against American Negro-hate. He is a descendant of the Dutch, who have distinguished themselves as much for their ill nature towards Negroes as for anything else. He belonged by wealth and position to the very first circles of the old Dutch aristocracy; he was the constant and admired associate of the proudest Negro-haters on the face of the earth; he had for years been a member of that most unscrupulous band of organized, systematic, practical promulgators of Negro-hate, the Colonization Society: and yet, in Broadway Tabernacle, upon an antislavery platform, in the city of New York (the worst city, save Philadelphia, since the days of Sodom, on this subject), Gerrit Smith stood up before four thousand of his countrymen to denounce this their cherished, honoured, they believe Christianized

Page 56

vice. To mortal man it is seldom permitted to behold a sight so full of or so radiant with moral power and beauty. Among the things he said, I may attempt to recall one sentiment--he asserted that, in ordinary circumstances, a person does not and cannot know how or what the Negro, the victim of this fiendish feeling, has to endure. Englishmen coming to America at first look upon it as a species of insanity. We are not all conscious of what we are doing to our poor coloured brother. "The time was, Mr. Chairman," said this prince of orators, "when I did not understand it; but when I came to put myself in my coloured brother's stead--when I imagined myself in his position--when I sought to realize what he feels, and how he feels it--when, in a word, I became a COLOURED MAN--then I understood it, and learned how and why to hate it."

To enforce his personal illustration there was one great fact. Mr. Smith had read of One "who made himself of no reputation," and he chose to imitate Him. Long, long before the anti-slavery question agitated the American mind, Mr. Smith and his excellent lady had concluded that, by whomsoever they might be visited, no coloured person should be slighted or treated with any less respect in their mansion because of his colour. Mr. and Mrs. Smith knew that they were visited by some of the first

Page 57