Last of the Pioneers:

Or Old Times in East Tenn.;

Being the Life and Reminiscences of Pharaoh Jackson Chesney

(Aged 120 Years):

Electronic Edition.

Chesney, Pharaoh Jackson, b. 1781?

Webster, J.C. (John Coram), b. 1861.

Funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., Matthew Kern and Elizabeth S. Wright

First edition, 2003

ca. 225K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2003.

Source Description:

(title page) Last of the Pioneers, Or Old Times in East Tenn.; Being the Life and Reminiscences of Pharaoh Jackson Chesney (Aged 120 Years).

(cover) Last of the Pioneers.

Chesney, Pharaoh Jackson, b. 1781?

Webster, J. C. (John Coram), b. 1861.

130 p.

Knoxville, Tenn.

S. B. Newman & Co., Printers & Bookbinders

1902.

Linda Brown and Sydney Brown provided their personal copy of the text for

the electronic publication of this title.

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered

typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All footnotes are inserted at the point of reference within paragraphs.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

- African Americans -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Virginia -- Biography.

- Underground railroad.

- Slaves -- Tennessee -- Biography.

- Chesney, Pharaoh Jackson, b. 1781?

- Freedmen -- Tennessee -- Biography.

- Plantation life -- Tennessee -- History -- 18th century.

- Frontier and pioneer life -- Tennessee.

Revision History:

- 2004-02-16,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2003-03-14,

Elizabeth S. Wright

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2002-05-28,

Matthew Kern

finished TEI/SGML encoding.

- 2001-11-20,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

Last of the Pioneers

OR

Old Times in East Tenn.

BEING THE

Life and Reminiscences Of

Pharaoh Jackson Chesney

(Aged 120 Years)

BY

J. C. WEBSTER

KNOXVILLE, TENN.

1902

Page ii

S.B. NEWMAN & CO.

PRINTERS & BOOK BINDERS.

Page iii

CONTENTS.

- A Narrow Escape. . . . .96

- A Remarkable Negress. . . . .18

- A Year with No Summer (1816). . . . .75

- Clarksville--Home of My Childhood. . . . . 23

- Conclusion. . . . . 129

- Early Methods, Manners and Customs. . . . . 43

- Early Roads. . . . . 69

- Harvesting and Threshing. . . . . 57

- Hiding the Knives. . . . . 88

- House Raisings--The Corn Husking--The Quilting Bee, Etc. . . . . .51-53

- Instances of Longevity. . . . . 16

- Introduction. . . . . 7

- John Chesney, Pharaoh's Last Master. . . . . 93

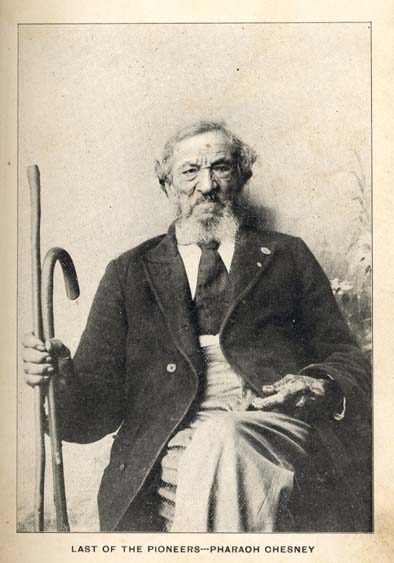

- Last of the Pioneers--Pharaoh Chesney--Illustration.

- Mills. . . . . 61

- Old Time Workings--Fire Hunting. . . . . 49-50

- Pharaoh's Age--Bill of Sale. . . . . 127

- Pharaoh's Master--Practical Jokes--Free Masonry. . . . . 87

- Polk and Jones Debate at Blain's X Roads. . . . . 89

- Preface. . . . . 5

- Railroads. . . . . 74

- Salt. . . . . 64

- Sarah Jenifer, of Washington, D. C.. . . . . 21

- School and Church--Teacher and Preacher. . . . . 55

- Slaves and Slavery. . . . . 97

- Special acknowledgment. . . . . 4

- Superstition. . . . . 116

- The First Steamboat on the Roanoke and Dan. . . . . 27

- The Home of Pharaoh Chesney--Illustration

- The Indians--Traditions--Praraoh's Recollections of Old Toka. . . . . 31-40

- The Old-Time Tavern, or Ordinary. . . . . 72

- The Old Time Wagon--Stage Coach. . . . . 70-71

- The Underground Railroad. . . . . 119

- The Wild Turkeys. . . . . 66

- Trip to the Western District. . . . . 77

Page 4

SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGMENT.

The writer is under special obligation to Mr. Robert Brice for valuable assistance in the publication of this volume. He has been a friend of the enterprise from its inception; and his aid and encouragement have made it possible for the public to have this work.

Mr. Brice is a prosperous, progressive farmer; an enterprising, public-spirited citizen; and, at present, a candidate for Register of Deeds for Knox County. He would honor any position of trust or responsibility to which his fellow citizens might call him.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1902, by

J. C. WEBSTER.

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Page 4a

LAST OF THE PIONEERS--PHARAOH CHESNEY

Page 5

PREFACE.

Dwelling alone, in a cabin of the most primitive description, on the summit of Copper ridge, five miles south of Maynardville, Union county, Tennessee, is unquestionably, one of the most remarkable men in the state of Tennessee, if not in the entire United States. He is remarkable not only on account of the great age to which he has attained, but equally so on account of the wonderful preservation of his bodily and mental powers. While it is impossible to assign the number of his years with absolute certainty, yet we are fully warranted in the assertion that he has undoubtedly passed the one hundred and twentieth mile-stone in his journey of life; and from collateral circumstances, we may infer that he may have reached, or even exceeded, a century and a quarter. The following pages will afford the reader some idea of his mental powers, nearly all of which were narrated by this old man within the present year (1902); and at this great age, he cuts and splits his wood, makes his fires, and does the principal part of his cooking. Besides, he not unfrequently walks a distance of three or four miles and returns within a few hours. He has walked from his cabin to Cedar Ford, a distance of three miles, the voting place of his district, and cast his ballot for every republican candidate for president, from Lincoln to McKinley. He, himself, is at a loss for the cause of his remarkable vitality; as he has been

Page 6

by no means a teetotaler, or strictly temperate in his habits. He laughingly remarks that many of the modern laws of health would have to be reversed in his case. He has been sick only a few times in his life. While it has been his good fortune, under the peculiar regéme of his two masters, to escape much of the drudgery usually falling to the lot of a slave, he has been, nevertheless, a very industrious man, active and energetic. He was fond of most of the old-time sports, and his great strength and activity caused his recognition in games and feats of strength.

Not less wonderful than his physical powers have been the strength and accuracy of his memory. In this respect, he is truly a prodigy. The incidents and occurrences of his past long life are apparently as vivid and clear to his mind as though removed but a few months in time. This fact induces the reflection that had he been reared under unfettered social conditions, and accorded the advantages of an education commensurate with the capacity of such a giant intellect, and with all the resulting powers of a liberal culture, he would easily have been the peer of B. K. Bruce, Fred Douglass, or Booker Washington. Let us fervently hope that history may never so far repeat itself that there may prevail a social condition or institution, that may prove a barrier to the progress of the human race; to quench the light of a glorious mind in the darkness of ignorance; or to prevent a human soul from achieving the destiny intended for it by the Creator.

Page 6a

THE HOME OF PHARAOH CHESNEY

Page 7

INTRODUCTION.

About the time the pioneers of Tennessee were having their mightiest struggles in the effort to establish the first republic west of the Alleghanies; about the time that John Sevier was making the supreme effort of his life in behalf of the state of Franklin; and about the time that John Tipton and his followers were making an equally heroic struggle to maintain in the colonies the government of North Carolina, there was born, on the banks of the picturesque Roanoke, at the little village of Clarksville, in Mecklenburg county, Virginia, a yellow lad, who was destined to witness, through a part of three centuries, the process of change and development, at the hands of man, of a wilderness, inhabited by wild and savage beasts, and scarcely less wild and savage men, into a country, blessed with every refinement and convenience of a progressive age. He was destined to live, witness, and realize the most sanguine hopes, and the full fruition of the labors and privations of these sturdy pioneers, who first led the way into the vast trackless wilderness, and bravely met the dangers, and with a fortitude hardly equaled in the experience of mankind, endured the countless hardships incident to the settlement of this fair country of ours. The name of this yellow lad was Pharaoh Jackson. Born within a half dozen years of the signing of the Declaration of Independence, and still remarkably vigorous in mind and body,

Page 8

at the end of the first year of the twentieth century, he has observed the clearing of the forest, the subduing of the savage, the erection of the log-cabin school and church house, the establishment of the simplest forms of government to meet the necessities and requirements of a band of settlers, and all the rude and primitive practices of a helpless and dependent people. Later on he has seen the experiment of more elaborate forms of government made, until, in the fullness of time, he has seen established in our country, one of the best governments on earth, creating and fostering the most benign and glorious institutions ever vouchsafed to a deserving people. He has been a witness to the fact that this noble heritage has not been without the most serious cost to the noble men and women who have bequeathed it to us. Many of our most cherished privileges are the dear purchase of the blood of our fathers. The civil and religious liberties that no one ever thinks of denying to us, and our entire immunities from the dangers of a lurking, savage and treacherous foe, are greatly in contrast with times and conditions within the life and memory of Pharaoh Jackson. Apparently to him as yesterday, it was more the rule than the exception to be rudely awakened from a sweet slumber by the savage howlings of hungry, ferocious wolves, or the blood-curdling war-whoop of the savage Indian. Then scarcely a road deserving the name was to be found within the present state of Tennessee. He has lived to see macadamized turnpikes putting the teamster within easy reach of every center of trade. Then, the only vehicle of travel was the rude, rumbling, rough, home-made wagon. He has lived to see, in all their beauty, convenience, and perfection, our modern

Page 9

wagons, buggies and carriages. He has seen railroads spanning the continent, carrying civilization, art and improvement to the far west. He saw the Indian gliding along the rivers of Old Virginia in his birch-bark canoe, and he saw the first steamboat that ever ascended the Roanoke river. He has picked cotton from the seed many a day, and about a pound of the fiber was the result of his labor, and he has lived to see a machine that would separate a thousand pounds of cotton from the seed in a day. He has lived in a time when it took two days for a letter to go from New York to Philadelphia, now he sees mail delivered to every family, six days in the week. Then the postage on a letter was 40 cents, now it is only 2 cents.

He was a young man when the government was established at Washington, and when the young republic made its first effort at territorial expansion in the acquisition of Louisiana, he was scarcely twenty-five.

He was about twenty when Whitney invented the cotton gin, and remembers the slaves talking of the "Yankee machine" that would do the work of a thousand negroes. When he was about ten years old, a cluster of log huts which had been built in the Ohio valley, was called Cincinnati, and this same pioneer settlement has, during his lifetime, become the metropolis of the great state of Ohio, with a water front of ten miles.

Suppose, for instance, that when he was fifty years of age, his master had taken him to Fort Dearborn, on Lake Michigan. He would have found a little settlement of about a dozen log cabins, which the settlers had named Chicago, (1833). If he had lived there until the present time he

Page 10

would have seen this little mud village become the fourth largest city in the world, with over three and a half millions inhabitants, the greatest railroad center, and the greatest grain and meat market in the world.

Or, suppose he had been born in New York City. When about ten years of age, he would have witnessed the inauguration of Washington, as the first president of the United States (1789). When twenty, he could have witnessed the laying of the corner-stone of the City Hall (1803). At about twenty-two, he could have seen the first free school incorporated in the city (1805). When he was twenty-five, he could have seen Robert Fulton make the trial trip of the Clermont, the first effort at steam navigation in America (1807). In the same year he might have assisted, in some way, in surveying, and officially laying out the city. He might have crossed over to Jersey City when the first steam ferry was established, when about thirty years of age (1812). At the age of forty, he might have joined in the demonstrations in honor of General Lafayette's visit, when he was given the freedom of the city (1824). He might, the next year, have seen lighted the first gas lights used in the city (1825). In the same year, he might have participated in the imposing ceremonies attending the formal opening of the Erie canal, when Governor Dewitt Clinton wedded Lake Erie and the Atlantic ocean by pouring a keg of the lake water into the ocean (1825). He would have been fifty-four when the terrible scourge of Asiatic cholera visited the city; and three years older when the terrible conflagration of 1835, lasting three days, destroying 600 houses and $20,000,000 worth of property.

Page 11

Had he gone to St. Louis when he was thirty-five years old, he could have assisted in erecting the first brick building in the city (1813). When about forty, he could have seen the first bank established (1816). Next year (1817), he could have witnessed the arrival of the first steamboat.

When he was forty-six the city would have received its first charter (1822). He would have witnessed the great prosperity of the city attended by many adversities. In 1785 and 1844 by great floods, occasioned by the swelling of the "Father of Waters;" in 1837 and 1847 by financial distress; in 1832 and 1848 by cholera; and in 1849 by fire.

Baltimore was well started as a town when Pharaoh Jackson was born, but he was nearly eighteen years old when it was made a city and a mayor chosen (1796).

Thus, it may be seen from the mention of these contemporaneous events that the subject of our sketch is older than most of the distinctive features, and the conveniences that belong to the great metropolitan cities in the United States; and, that had he lived in any of these great cities, he would have witnessed the first use of all the great inventions and improvements that have been perfected within the century just completed.

Not only has he been a living witness to the marvelous inventive and constructive genius of the nineteenth century, and the gradual displacement of the primitive methods and customs, by those more modern and effective, but he has also witnessed the introduction of some of the greatest household and economic inventions.

During his life-time have occurred some of most notable events of history. We shall mention only a few, with the

Page 12

remark that the occurrence of these events reached his ears as matters of news, and that at the present writing he remembers with distinctness, the impressions made upon his mind, and describes them with historical accuracy, dates excepted. Adoption of the Constitution (1787), Whitney's cotton gin (1793), Purchase of Louisiana (1802), Duel, in which Aaron Burr killed Alexander Hamilton (1804), Burr's memorable trial at Richmond, before Chief Justice Marshall, for treason (May, 1807), Fulton's steamboat (1807), War of 1812, the Seminole War (1835), as well as all the leading events of more recent times.

While he was yet a young man, assisting his master's other slaves in clearing out the canes in the bottoms of the "Roanoke and Dan," Virginia and all the states south except South Carolina, extended to the Mississippi river. North Carolina included the present state of Tennessee, Virginia included the present state of Kentucky and West Virginia, and Florida belonged to Spain. He has lived to see Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota carved out of the Northwest Territory--as well as the purchase, settlement, and development of all the great empire west of the Mississippi, and has joined in celebrating the addition of thirty-three new stars to the original thirteen on the American flag. He has not only lived to see the formation of this vast republic of ours by the voluntary union of so many independent states, but he witnessed the sanguinary struggle in which the fairest land under the sun was drenched in blood as a result of the dismemberment of this union. He has seen the boys in blue marching under the stars and stripes, and the boys in gray marching under the stars and

Page 13

bars, each fighting for a principle regarded as sacred and precious as life. And after this bloody civil strife, he has seen the white-winged angel of peace hover over this heaven-favored land, and later, when a foreign foe disputed the cherished rights of Americans, has seen these battle-scarred veterans, marching under the same flag, actuated by the same motives, and fighting for a common cause.

But the triumphs of war have been no less great and remarkable than have those of peace. Inventive and constructive genius in the palmy, quiet days of peace, have made conquests of far greater consequences to mankind than have been the victories gained on fields of battle. The little narrow creek meadow cut with an old Dutch scythe when Pharaoh Jackson was a full grown man, has been lengthened and widened until it has grown from one acre to fifty on account of the invention of the mowing machine. Instead of the reap-hook to cut the grain, and a wooden flail to beat it out of the straw, the great wheat ranches of the west have machines to cut, thresh, clean, and sack the grain. Equally great changes, improvements and revolutions have taken place in every branch of human industry. Since the boyhood of our sketch, great and mighty changes have swept the face of our great country. Progress in the arts and sciences has brought about so many and such varied improvements, and has occasioned such diversified industries in order to keep pace with human needs and ambitions, that in the space of this remarkable life-time, the face of nature has undergone a transformation as sweeping and wonderful as that of the reputed wizard with his magic wand.

The miserable wigwam of the savage Indian gave way

Page 14

to the unpretentious but comfortable hut of the settler. This, in turn, as ambition prompted and prosperity permitted, was transformed into the old colonial mansion, the only evidence of which, enduring to the present, is a heap of stones, and fragments of decayed timbers, scored in a primitive forest a hundred years ago. Beside these ruins, rendered sacred by time, tradition, and association, stands today the stately mansion, the acme of architectural design and mechanical execution.

The forest, no longer affording a refuge and shelter for the skulking savage lying in wait for his pale face brother, or the natural home of the bear, the deer, or the turkey--the hunter's paradise--has been leveled by the woodman's axe, and has become the fertile field, teeming with plentiful harvests of golden grain, or carpeted with luxuriant herbage where flocks and herds roam at will. The splashing water-fall, beside which, perhaps the tired hunter sat and rested, or perchance the Indian warrior seated by the side of its sparkling waters, and gazing into its clear, limpid depths, wooed his dusky mate, is directed by the hand of the artisan in an artificial channel, and made to turn the wheels of such machinery as contribute to the wants of an ambitious and a progressive people. The howl of the wolf, the scream of the panther, or the war-whoop of the savage no longer echo upon our hillsides or in our valleys. Such sounds were once the common but unpleasant music that greeted the ears of our forefathers. Old Uncle Pharaoh has heard all that in his time, and has been permitted to live to see a time when humanity may, after the day's toil, retire in peace and security, and in sweet repose, await the coming of the dawn. The

Page 15

summons for him to answer the roll-call on the other shore has been delayed until the mighty struggles for independence are over, and all the garments once dyed in blood have changed to mantles of ministering charity, and the white-winged angel of peace has hovered over our country. Like good old Simeon, he is ready, and exclaims, "Lord, let thy servant depart in peace; for mine eyes have seen thy salvation."

But the point sought to be made by these observations and illustrations, is that our country has not only passed through all these changes, but has done so within the space of a human life. This life, prolonged to a remarkable length, through the mercy and wisdom of Him "who doeth all things well," is perhaps the most wonderful survival of three centuries. This life has witnessed the beginning of what has culminated through the genius of man, aided by the forces of nature, in achievements that are today the wonders of the age. His eyes have followed each step from the uncertain experiment through each round of improvement in the ladder of perfection, until the topmost round is reached; and as genius pauses and surveys below him the century's conquest, and just as he shades his eyes in the effort to penetrate the invisible realms of the spirit world, a voice echoes, "Thus far and no farther."

But the mighty pendulum of time has not yet reached the limit of its ever-widening arc; time is yet swinging around the mighty circle of the ages; history must go on repeating itself; the lost arts must be restored to the world; and the changes to come will be more momentous than those of the past. Following in the track of the mighty march of

Page 16

time, nations and people yet unborn will view with silent wonder wrecks of today's greatness outgrown and superseded by achievements yet to be.

INSTANCES OF GREAT LONGEVITY.

The feature of this work which will no doubt carry with it the greatest weight of interest is the fact of the great longevity of the principal narrator. And while such instances are rare and isolated, yet history abounds in many examples of persons who have attained to a remarkable old age. A table was prepared by Mr. Easton, of Salisbury, England, giving some of the most noted names on record, of Europeans and Asiatics.

| Date | Aged | |

| Appollonius of Tyana | 99 | 130 |

| St. Patrick | 491 | 122 |

| Attilia | 500 | 124 |

| Leywarch Hêw | 500 | 150 |

| St. Coemgene | 618 | 120 |

| Piastus, King of Poland | 861 | 120 |

| Thomas Parr | 1635 | 152 |

| Henry Jenkins | 1670 | 169 |

| Countess of Desmond | 1612 | 145 |

| Thomas Damme | 1648 | 154 |

| Peter Torton | 1724 | 185 |

| Margaret Patters | 1739 | 137 |

| John Rovin and wife | 1741 | 172 & 164 |

| St. Mougah or Kentigern | 1781 | 185 |

Facts prove that, in circumstances favorable to extreme longevity, the Europeans, the most polished communities, have no pre-eminence over the tribes of Africa, the least

Page 17

advanced in the social scale. Doctor Pritchard, from various sources, collected a variety of remarkable instances of negro longevity, of which the two following are samples:

December 5, 1830, died at St. Andrews, Jamaica, the property of Sir Edward Hyde East, Robert Lynch, a negro slave in comfortable circumstances, who perfectly recollected the great earthquake of 1692, and further recollected the person and equipages of the lieutenant-governor, Sir Henry Morgan, whose third and last governorship commenced in 1680, viz., one hundred and fifty years before. Allowing for this early recollection the age of ten years, this negro must have died at the age of one hundred and sixty years.* *Sear's Wonders of the World, pp. 31-32.

Died, February 17, 1823, in the bay of St. Johns, Antigua, a black woman named Statira. She was a slave, and was hired as a day laborer during the building of the jail, and was present at the laying of the corner-stone, which ceremony took place one hundred and sixteen years ago (1823). She also stated that she was a young woman grown when President Sharp assumed the administration of the island which was in 1706. Allowing her to be fourteen years old at that time, we must conclude her age to have been upwards of one hundred and thirty years.* *Sear's Wonders of the World, pp. 31-32.

The same historical source from which the above instances were derived, furnish many more similar examples. These facts and illustrations are sufficient to show that there is no physical law forbidding the negro from attaining a longevity equal to that of the European in circumstances friendly to it; while

Page 18

placing the European in subjection to the same amount of toil in the West Indies, or planting him amid the swamps, the luxuriant vegetation, the inundation, and heat of Western Africa, and his term of life would not, in general, come up to the negro standard.

It was a well known fact among the early settlers that some of the Indians attained to a very old age, and were represented by members of their tribe to be much over one hundred years.

Humboldt, speaking of the native Americans, says, "It is by no means uncommon to see at Mexico, in the temperate zone, half way up the Cordillera, natives, and especially women, reach a hundred years of age. This old age is generally comfortable; for the Mexican and Peruvian Indians preserve their strength to the last. While I was at Lima, the Indian, Hilario Sari, died at the village of Chiguata, four leagues distant from the town of Arequipa, at the age of one hundred and forty-three. She had been united in marriage for ninety years to an Indian by the name of Andrea Alea Zar, who attained to the age of one hundred and seventeen. This old Peruvian went, at the age of one hundred and thirty years, a distance of from three to four leagues daily on foot."

A REMARKABLE NEGRESS.

The Pennsylvania Inquirer, of July 15, 1835, contained this notice: Curiosity--The citizens of Philadelphia and its vicinity have an opportunity of witnessing at the Masonic Hall, one of the greatest natural curiosities ever witnessed, viz.: Joice Heth, a negress, aged, one hundred and sixty-one

Page 19

years, who formerly belonged to the father of George Washington. She has been a member of the Baptist church for one hundred and sixteen years, and can rehearse many hymns, and sing them according to former custom. She was born near the old Potomac river, in Virginia, and has, for ninety or one hundred years, lived in Paris, Kentucky, with the Bowling family.

All who have seen this extraordinary woman are satisfied of the truth of the account of her age. The evidence of the Bowling family, which is respectable, is strong, but the original bill of sale of Augustine Washington, in his own hand-writing, and other evidences, which the proprietor has in his possession, will satisfy even the most incredulous.

A lady will attend at the hall during the afternoon and evening for the accommodation of those ladies who may call."

A Mr. Lindsay was then exhibiting this aged negress at Philadelphia. Mr. Barnum, the great showman, was then on the lookout for some great curiosity, and went to Philadelphia to endeavor to purchase this novel exhibition. The first price put on the old woman was three thousand dollars, which Barnum declined to pay. He offered one thousand, which was finally accepted, and he exhibited her to immense throngs of people in all the large cities of the United States, until the following February, when old Joice Heth died, literally of old age.

The best description of this old negress is given by Mr. Barnum himself. "Joice Heth was certainly a remarkable curiosity, and she looked as if she might have been far older than her age as advertised. She was apparently in good

Page 20

health and spirits, but from age or disease, or both, she was unable to change her position; she could move one arm at will, but her lower limbs could not be straightened; her left arm lay across her breast, and she could not remove it; the fingers of her left hand were drawn down so as to nearly close it, and were fixed; the nails on that hand were nearly four inches long, and extended above her wrist; the nails on her large toes had grown to the thickness of nearly a quarter of an inch; her head was covered with a thick bush of grey hair; but she was toothless and totally blind, and her eyes had sunk so deeply in their sockets as to have disappeared altogether.

Nevertheless, she was pert and sociable, and would talk as long as people would converse with her. She was quite garrulous about her protege "dear little George," at whose birth she declared she was present, having been at the time a slave of Elizabeth Atwood, a half sister of Augustine Washington, father of George Washington. As a nurse, she put the first clothes on the infant, and she claimed to have "raised him." She professed to be a member of the Baptist church, talking much in her way on religious subjects, and she sang a variety of ancient hymns. In proof of her extra-ordinary age and pretensions, Mr. Lindsay exhibited a bill of sale, dated February 5, 1727, from Augustine Washington, county of Westmoreland, Virginia, to Elizabeth Atwood, a half sister and neighbor of Augustine Washington, conveying 'one negro woman named Joice Heth, aged fifty-four years, for and in consideration of the sum of thirty-three pounds, lawful money of Virginia.' "*

* Life of P. T. Barnum, pp. 57, 58.

Page 21

SARAH JENIFER, OF WASHINGTON, D. C.

Apropos to the foregoing, we clip from the National Tribune of October 1, 1885, the following notice of an aged negress of that city:

"Remarkable instances of longevity are sometimes found among the colored people. Sarah Jenifer, who was known to be one hundred and twenty years old, died in this city last week. Her eyesight, and indeed most of her physical and mental faculities, showed slight impairment until within a year past. She reared nineteen children, many of whom were similarly prolific, and, as may be imagined, she left a family of grandchildren down to the fourth and fifth generations, numbered by hundreds. Three of her surviving children are past ninety."

Page 23

CLARKSVILLE, HOME OF MY CHILDHOOD.

I was born and reared in the town of Clarksville, Mecklenburg county, in Old Virginia, and this is why I always speak of Clarksville as my childhood home. This beautiful town, built on a lovely strip of level bottom land, was at first laid out on the south side of the river, just below where the Roanoke and Dan come together. The river still goes on to the ocean under the name of the Roanoke, but we all got used to calling the name of both rivers. There was, from my earliest recollection, a considerable settlement on the other side of the river, called Klipper's Landing, but after the steamboats began making regular trips to the town and above, quite a town sprung up across the river; and so, we might say, that Clarksville is situated on both sides of the river. Old Master Jackson had a large plantation and a magnificent home just below town, but almost joining it. Old Master Johnathan Jackson did a great deal of business in town, while young master, Corbin Jackson, was a stock dealer, and often took me on his buying trips to assist him in bringing back the stock he would buy. It was on one of these long trips buying up droves of cattle and sheep, that he came down into Tennessee, as far down as Surgoinsville, Hawkins county, that he became so favorably impressed with East Tennessee, that he was determined to one day

Page 24

make his home somewhere along Clinch mountain, in the beautiful valley. Speaking of Clarksville, I do not believe the Creator ever made a place more fit for a life of pleasure and happiness than this town and country. The land was everywhere rich; there was plenty of fine timber and good water; the forest abounded in all kinds of game, from a ground squirrel to a bear; and every stream was full of fish, that could be caught without difficulty. Almost every old settler lived on his own large plantation, in a fine mansion, owned a number of slaves, and had become rich during the few years since the settlement of the country. These settlers, most of whom were old men when I was a mere boy, had turned their attention toward the raising of such products as commanded a ready market, either at home or abroad. Boats were built at Clarksville and at many other points, which were loaded with all kinds of produce, and taken down through North Carolina to the ocean, where it was loaded on ships. Tobacco was one of the principal shipping crops, and many large plantations were devoted almost entirely to raising it. Back farther in the hills and mountains, there were not as large plantations and as fine mansions as were found in the valleys and along the rivers. There were not so many slaves, but what few there were seemed contented and happy. The people lived equally as well, and had plenty to sell. Every Saturday wagons would come in from the hills and mountains to Clarksville, bring in loads of fruit, fur skins, chickens, butter, eggs, maple sugar, feathers, pine tar, ginseng, and often deer and bear meat. These articles they produced in great abundance, and usually bore a fair price. It was sold to the stores or to the shippers, or exchanged

Page 25

for salt, thread, indigo, nails, powder, lead, and such manufactured articles as the merchants kept for sale. There was not much money in circulation, neither did the people need or want it. I sometimes yet wonder how and why the world ever took such a notion for money. I can remember when bartering was all the go, and everybody did it. A bushel of corn or potatoes, or five pounds of meat for a day's work. So many pounds of feathers, tobacco, maple sugar, or butter for a yard of cloth, etc. Everybody understood what the custom of the country was, and very few buyers or sellers would undertake to make a bargain that was different from the regular custom. I have watched this old custom gradually give way, and money to come into use, and my opinion is that the old style of trading was simpler, more easily understood, and was much fairer to the seller than to have a money value attached to every article. Very few persons ever raised just enough of everything they wanted for their own use. Of some things they raised more, and of other things they produced less than they needed; and so this was remedied by an exchange of articles, this deal being called bartering.

I remember my first bartering. As I have told you, the streams abounded in fish, which were easily caught. The merchants kept salt-fish in the stores to sell, but some of their customers preferred fresh fish. So the merchants were glad to exchange the salt-fish for the fresh ones, and as this just suited me, I made many trades with them. The salt-fish would keep for any length of time, while the fresh ones had to be used at once.

In addition to this being a land of plenty to eat, and of

Page 26

peace and prosperity, there was, also, plenty of amusements of all kinds to keep up a fellow's spirits. No use of dying of the "blues" on a plantation of darkeys. These were generally allowed liberty to go where they pleased on the plantation, and, just so a man did a good day's work, and the feeding and wood-chopping besides, he was allowed to enjoy himself in any reasonable way, so no harm or damage was done. As for myself, I would have been content to spend all my days, as I once did, at my old childhood home. It was all the freedom my heart could ever wish, and if I had had my choice I would never have left there. But the saddest day in all my life came to me when I was told that my beloved wife and children must be taken one way, and that I must go another. A more cruel blow could not have been given to me. I could not have felt worse if I had been told that we were all to be killed. It seemed to almost break my poor wife's heart; and the sad thought has always been with me, whether the poor creature ever lived after our separation. Our four children were grown, and one of them married to a man by the name of Jones, who were both sold and taken to Lexington, Kentucky. Of the other three I have never seen nor heard of since we were separated. During the many years since all of us that were living became free. I have contemplated making a search--like a mother partridge for her scattered brood-- for them; but this life, though long, has been so full of all kinds of cares and duties that this supreme desire of my heart must go unsatisfied. My day of life, I fully realize, is too far spent, and the shades of its evening are closing too close around me to permit the faintest prospect of my ever again seeing the home of my childhood's

Page 27

happy days, which I learn is all changed, save in name and location; much less to ever behold, on the shores of time, the faces of my loved ones, so cruelly taken from me. But the solace of my declining days has been, that as my feeble, tottering frame approaches nearer and nearer to the silence of the grave, my faith grows stronger, and the way becomes brighter as visions of blissful immortality greet my disconsolate mind. I feel that I have now nothing to live for, and am simply waiting for my Master's call; and when that summons shall come, that same sustaining faith whispers to me, that perchance some of those loved ones have already gone on before me, and may be the first to greet me over there. That ever-abiding faith in my Creator's power and wisdom also assures me that though my bones are not buried at my old Virginia home--as my most cherished wish has been--that when the great roll-call of heaven is made, that here in Sunny Tennessee, my grave will be found by Him, and I shall awake and come forth and enter upon that new life, which shall know neither decay nor death, and where severed ties and dismembered families will enter upon a perpetual union, "Where the wicked cease from troubling and the weary be at rest."

THE FIRST STEAMBOAT ON THE ROANOKE AND

DAN.

I remember as well as if it occurred but a month ago the occasion of the coming of the first steamboat up the Roanoke to Clarksville. We had all heard of steamboats, but there was not a half dozen people in all that country

Page 28

that had ever seen one, and but few, I think, had any correct idea of how one would look. I remember we darkies, after we heard that on a certain day a steamboat was coming to our town, would sit around and exchange ideas and notions as to how it would look. After seeing one we had many hearty laughs about how different it proved to be from what we imagined. For my part the strangest thing to me was how there could be enough iron about it and yet it not sink. About as silly was our wonder, when railroads were first talked of, how they could carry anything else after carrying enough sand to keep the wheels from slipping! One darkey being called upon for his opinion, said that the thing could not be; that no power in or on the boat could possibly move the boat; that it would be just like a man trying to lift himself over the fence by pulling up on his boot straps. About the funniest idea I heard given was by a numb-skull who said that the boat would have to stop running when the steam was used to whistle! But we all had to give it up, in spite of our logic, when the boat steamed into Clarksville.

The news had been circulated far and wide that a steamboat would come up to Clarksville from Weldon on a certain day. This was the occasion of a general holiday among all classes. Horses and mules were taken from the plow and hitched to all sorts of conveyances, and men, women and children came from all parts of the country, and collected on each side of the river. Seats were put up on the banks for the women and children; some of the men sat on their horses in order to see over the heads of the crowd, and many of the men and boys climbed into trees in order to be the first to see. Just below town the river makes a bend,

Page 29

and every eye was turned in that direction. Soon a shout went up from those in the trees saying that they saw the smoke and that she was coming. Then there was such a scramble as I have never seen since in order to get nearer the landing. Soon the black curling smoke could be seen by all, and in a moment more, the tall black smoke-stack loomed up just at the bend a short distance below us. Then the scramble for places was renewed, and shouts, and yells, and screams went up from the crowd lining each bank. As there was a large crowd on both sides of the river, there was much doubt and anxiety as to which the boat would land. The pilot, evidently considering ours as the largest crowd, began turning her prow toward our side, and just then the whistle began blowing, and the crowd on shore created such a scene as I have never before or since witnessed in my life. The shouts were deafening; women screamed and fainted, and children were frantic with the excitement. With mighty puffs and heaves, with the foam leaping and the waves dashing against the shore, the boat neared the bank. Two broad, thick planks were laid out upon which persons on the boat could come ashore. As soon as these had stepped on land, several of the crowd began crowding on the gang plank to go in and see the inside of the boat. About the time both planks were full the steam blew off with such force and noise that a regular panic ensued. In their fright several of those on the planks fell head long into the mud and water; again the women and children screamed, this time in fright; the small and weak in the crowd along the bank were run over, knocked down, and trampled upon in the wild, mad rush to get away from the escaping steam.

Page 30

Most of the crowd thought that the thing had exploded, and it was some time before the captain could restore order by the assurance that there was no harm. He took pains to explain all about how the safety-valve would let off the surplus steam, and prevent the boiler from bursting.

But I have not told you the worst. The horses had their nerves strung up to a high pitch already at the noise of the boat, and the tumult of the crowd. In their haste to get a position on the bank, many had alighted from their vehicles, and had left the horses unhitched. These, when the steam blew off, could stand it no longer, and broke away without driver, and went dashing and clattering pell-mell, helter-skelter in several directions, upsetting wagons and buggies, tearing down posts and fences, and pursued by dozens of yelping dogs, left the scene in the wildest confusion. Many people were run over and hurt, and several horses were crippled in the stampede. The crowd across the river, that had been disappointed in the boat's not landing on their side, now took in the situation, and set up the most tumultuous laughing, shouting, and clapping of hands that I ever heard. They enjoyed our discomfiture immensely.

After the panic was over, and order restored, speeches were made, wine and cider was passed around, and the captain spoke glowingly of the great advantages and possibilities of the steamboat, and what a great blessing it would prove to the world. If any one of that great crowd besides me is still living, he will join me in saying that that was the greatest day Clarksville ever had. Soon, this boat made regular trips to our town, and before we left that beloved place to come to Tennessee, other boats made regular trips

Page 31

up the Roanoke and Dan. They usually came steaming up after dark, beautifully lighted up, and the bands playing. Oh! we never grew tired of the glorious sight; it seemed to thrill us with new life. And though my ears are getting deaf, and my old eyes growing weak, I pine once again to hear the shrill steamboat whistle, and to see the beautiful lights and the streaming banners once more on the lovely river of my boyhood days. Truly, there is no time like the old time, and it will never come to us again.

[In spirit, if not in words, Uncle Pharaoh constantly reechoes the sentiment of the poet, in the following lines:]

"There are no days like the good old days,

The days when we were youthful;

When humankind were pure of mind,

And speech and deed were truthful;

Before a love for sordid gold

Became man's ruling passion,

And before each dame and maid became

Slaves to the tyrant's fashion."

THE INDIANS.

General Jackson used to say that the only good Indian was a dead Indian. He said that little Indians made big Indians, and that big Indians were always bad Indians; and in his battles with these savages, he told his soldiers to kill all of them, big and little. This made it pretty hard on the old squaws, but I know, from a long acquaintance with the Indians, that the women were generally as big liars and

Page 32

rogues as the men, and when they would be torturing a white person, that the women would often think of more cruel things to do than the men. Sometimes when a crowd of Indians would come to a settler's cabin to beg, the women would slip around the house and steal everything loose, while the men would keep the attention of the white people. You could never tell much about what an Indian was going to do. He might have come to kill you, and he would come up smiling in such a way as to make you believe he was the most friendly Indian in the world. An Indian could deceive a fellow about as well as some white folks can. I always knew that we colored people came from Africa, and that always satisfied me, but I always had a great desire to know where the Indians came from. I tried hard to find out all I could from the oldest Indians, but they had a great, long story about descending from some great, powerful tribe--something that had been told to them by the old men (tradition). But I never thought they knew anything certain about it themselves. They could not tell me anything about who made the mounds of earth to be found in many parts of Tennessee. We always called them Indian mounds, and supposed the Indians made them, but for what purpose, or when, they themselves seemed to know as little about it as we did. One thing only we do know--they were here when the white men first came, and that is all. Another thing, some of the Indians did not seem to know much about the flints or arrow-heads which can be picked up almost every-where. They could be picked up just the same when I was a boy in Old Virginia, and I never saw but a few Indians that could make them. The ones I saw them make were rough

Page 33

and ugly. They did not use the bow and arrow very much for they nearly all had guns, and had learned how to use them from the white people. But every Indian boy had to learn how to use the bow and arrow, and so well did they learn it that they seldom ever missed anything they ever shot at. Birds and animals which they shot were often not killed at once, but were so badly crippled by the rough flints on the arrows, that the Indians soon caught up with them and finished killing them. It was a funny sight to see them splashing in the creek after a wounded fish, bursting through the brush after a crippled turkey, or chasing through the woods after a wounded deer. But they were generally successful, and seldom failed to bring home the game.

But while the women were as bad as the men in some respects, in others they were very much better. They did not keep themselves much cleaner than the men, and neither gave themselves much concern on this score. But they were not half as lazy as were the men. In the chase or on the warpath the men were active and sprightly enough, but when about the lodge or wigwam, the lazy, good-for-nothing fellows would not do a lick of work in the way of preparing food or fuel, and all of the work now considered as belonging to men, was performed by the women. The animals brought in as game were skinned, cut up, and prepared into food by the women, and often the greedy hunters would turn in for dinner before it was half done, and devour all of it, before the women could get a share. The seed-corn had to be kept hidden from the men for when they would come in tired and hungry, they would eat up everything in sight. When the season came for planting, the women prepared

Page 34

the ground for the seed, planted the grain, and gave it such little cultivation as it ever received. The corn was most always planted in a rich, moist spot of ground, and did not require much work except to keep the weeds pulled out. They also planted beans, and raised abundant crops of them. They boiled beans and green corn together and made succotash which was very good. The Indians taught the white settlers how to raise corn. The Indians showed them how to deaden the timber by building fires at the roots of the trees, or by cutting a ring around the tree while the sap is flowing. They also showed them that where the land was not rich, if they would dig a hole and put into it a good sized fish, and then plant the corn in the hole with the fish, that they would always raise a big hill of corn, no difference how poor the land was. Speaking of corn I am sure that the Indians could never have existed without it. The land was rich, and it did not require much labor; when ripe it did not require to be gathered before winter, as it would stand all through the winter, and be sound in the spring. There was no other grain or vegetable that was so easily raised, that produced such great quantities, and took care of itself. The Indian might have subsisted on fruits, berries and game during the summer, but they really could never have lived and kept their horses alive through the winter without corn.

But raising the corn was not the hardest work that the Indian woman had to do. Whenever game became scarce in any locality, or the grass gave out, then the men would go to another place and decided on a location. When the time came to move the women had to carry all the luggage and the cooking utensils. The load one could carry was simply

Page 35

astonishing. The Indian men seemed to think it beneath the dignity of a hunter or a warrior to engage in any kind of manual labor.

But while the Indian was cruel, revengeful, deceptive, and indolent, still he had some redeeming traits of character. You have heard it said that he never forgave an enemy nor forgot a friend. Well, that was just about the case exactly. In all my dealings with these savage people, I have never observed much exception to that rule. For if you ever did one a kind act, he would never forget you, but we have often wished that they would sometimes forget. They would be very much like the old darkey was by his master. One day the old darkey's master gave him a chew of tobacco. The next day the old darkey come back and said, "Massa, don't one good turn deserve another?" Of course his master said "Yes." Then the old negro said, "You gave me a chew of tobacco yesterday, so that deserves another." So it was with the Indian. He would never forget you, and would always be coming back for something else; and if he didn't get what he wanted, he would conclude that you was not a friend to him, even though you had given him a dozen things. They would just hang around and beg and steal, or starve if you once began to give to them. So, many of the early settlers decided that it was best to let them be enemies and watch them than to feed and clothe them. For whenever you got on friendly terms with a lot of Indians, they would always be prowling around, day and night, and, as I said, if you denied them what they wanted, it would be sure to make them mad. They have been known to give

Page 36

up even hunting and fishing to live off a few settlers that wanted to keep friendly with them.

But if you had ever befriended one, especially if you had fed him well when he was very hungry, he would never forget your face, nor the favor, and if you ever got into trouble, he would do everything in his power for you, even at the risk of his life.

I once knew a hunter in Old Virginia, who went out one day in search of game. The whole country was a wilderness, and no roads, except here and there an Indian trail. He went so far out into the forest that he finally became lost, and when, at last, he decided to return home, he knew not what direction to take. He would occasionally cross an Indian trail but was afraid to follow it, fearing that he might come up with Indians who would, as he thought, most surely kill him. Or, one of the trails, if followed, would certainly lead him to one of their villages, where he would be captured and perhaps tortured. So, this man wandered about through the woods all day, with no thought of game, but only of reaching his cabin. Night finally came on, and weary and discouraged, he climbed up into a tree, taking his gun up with him. He climbed the tree in order to be out of the reach of bears or wolves that would soon be prowling around in search of food. He sat up in the tree and nodded, being so sleepy that he could scarcely hold on to the limbs. But about midnight his desire for sleep was taken away, when he heard, not far from the tree where he was, the solitary howl of a wolf. This was almost immediately answered by that of another, on the top of a ridge not

Page 37

far away. Soon the howls were coming from all directions. As they came nearer their blood-curdling yells almost chilled the blood in his veins. The moon was shining dimly, and by straining his eyes, he could see coming toward him a long, slim, dog-like animal. It came on up and began howling, jumping, scratching, and gnawing at the tree. In a few minutes other wolves were coming to the tree from all directions. Soon there must have been as many as fifty of these hungry creatures, howling, and gnawing at the tree. He is sure that they would have gnawed down the tree before morning, but as soon as they would begin to gnaw at the tree, they would begin to fight, which would be kept up for several minutes. Then, as soon as the fighting was over, they would come back to the tree. He sat in the tree and watched these savage brutes until daylight, when, one by one, they would look up at him and show their ugly teeth, and slink away. When the sun was fairly up they were all gone. But still he stayed in the tree until he was sure they had gone away a long distance, when he slid down from the tree, and started on, he knew not where. All day long, he wandered, tired and hungry, crossing logs and creeks, and climbing hills in hope of getting a glimpse of the settlement where his cabin was. He traveled on until it was nearly dark again, and he was so tired that he could scarcely walk and carry his gun. He was just thinking of looking out for a suitable tree in which to spend another night with the wolves, when he came to an Indian trail. He stopped in the trail to look each way (as a white man always did when crossing an Indian trail) and his heart almost sank within him at what he saw. Coming toward him, not a hundred yards away,

Page 38

was a band of about twenty Indians. When they saw him, they uttered a hideous yell, and made a rush for him. He stood perfectly still, and when they came up, they seized him, and handled him very roughly, and taking away his gun, pointed with angry and threatening gestures for him to move ahead in front of them. The trail led over hills and ridges for several miles to their village. They had just returned from a hunt, and had killed a deer, which they threw down to the women when they reached the huts, and each of the men immediately threw himself upon the ground and were soon asleep. Almost as soon as they arrived with the prisoner, they placed a guard of young men about him. They kept a very close watch over him all the while. After a little while, the deer was prepared, after their usual fashion, for being eaten, and the sleepers were aroused. They all went in a rush for the dinner, and none of them, except one, seemed to pay any attention to the captive. One of them came to where he was guarded and motioned for him to come. By the time they had reached the food, the greedy hunters had taken all of it but one piece, which was large enough for two persons. This piece the Indian seized, and gave nearly all of it to the white man, keeping only a small piece for himself. This meat satisfied his hunger, and he was taken back, and the guard again placed round him as before. The Indians, now rested and refreshed, seemed to be consulting as to what should be the fate of the prisoner. All except the one who had given him the meat seemed to be in a very ugly humor, and he felt sure that it all meant no good for him, though he could not understand a word they were saying. Once in a while he could catch a word or two of broken

Page 39

English from the friendly Indian, which gave him hope that this Indian, having been with the white people long enough to learn some of their words, would have some friendly feeling for him, and would in some way prevent his being killed.

Soon dark came on, and the hunters who had captured him all went to sleep except one who would be left to guard him. One would only guard for a short time when another would be awakened, and this one would fall asleep. By and by, about midnight, it came the turn of the friendly Indian to guard, which he did until all the rest were sound asleep. Then the Indian arose very softly, and motioned for the white man to follow him. He did so, and after going a short distance from the camp, they came to a stump behind which was sitting the gun which had been taken from him, and upon the stump was a large piece of well-cooked meat. The Indian bade the white man take these, and then the Indian led the way by a different trail from that by which they had come. All the time after they left the stump, there was not a word said by either of them until they must have traveled several miles. Finally, the Indian stopped, and turning to the man said, "I have saved your life at the risk of losing my own. They had decided to put you to death, and if it should be found out that I have aided you in getting away, I would have a close call for my own life. I will no doubt be put to death in your place. But I came to your cabin a long time ago, hungry, tired, and pursued by my enemies who were seeking my life. If they had caught me, they would have killed me; but while I was in your cabin, and you were giving me food and shelter, they passed by, and you saved my life. Now I have saved yours. Keep

Page 40

this trail for a short distance further, and it will take you to the white settlements." So saying, the Indian turned quickly, and in a minute was speeding his way back to the Indian camp.

All the time the Indian was talking, the white man was trying to remember where he had seen the face that seemed to have something familiar about it. At last, he remembered that when the Cherokees and Chickasaws were making war on each other, that an Indian, that appeared to be in great distress and very much frightened, came to his cabin and begged for food and water. He would not stay outside to eat it, and while in the cabin a number of Indians passed by. He then recognized this friendly Indian as the one.

INDIAN TRADITIONS. UNCLE PHARAOH'S

RECOLLECTIONS OF OLD TOKA.

Much of the Indian character, their modes of life, and warfare, their manners and customs, and many of their traditions, I learned from an old Chickasaw chief, named Toka, who resided at the Chickasaw Old Fields, near the Muscle Shoals, until his tribe was overpowered and driven out by the hostile Creeks and Cherokees. He then moved up nearer to the Cumberland settlements, and was one of the two Chickasaw guides employed by Col. James Robertson in his memorable Coldwater expedition against the Creeks occupying the old Chickasaw hunting grounds. Much of the success of this expedition was due to the knowledge of the country, and the fidelity of this old chief. It was he who informed Robertson and others of the Cumberland settlers

Page 41

that the Spanish traders were offering a regular bounty for the scalps of the white settlers, and were furnishing the Indians with guns and ammunition in consideration of their services in committing depredations on the whites. He still had the gun and blanket, and often spoke of the horse presented him as his share of the spoils, and in consideration of his services. Later, sad, dejected, and disspirited at the loss of their valued hunting grounds, and the dispersion of his tribe, he passed up the Tennessee river, his identity concealed, dwelling for a time, among the various tribes through which he passed, finally making his way to the extreme north-eastern part of the state, and becoming absorbed in name, with a tribe of Cherokees dwelling on the border line, secretly bewailing the fate of the nation of which he was once so proud to be a descendant. I was with him much, as he often came to Clarksville, and as always a great favorite with the whites. But I never knew what finally became of him.

He took great pleasure in relating the tradition as to the origin of the Chickasaws east of the Mississippi river. He said their ancient home was in Arkansas and to the westward; and, that when they decided to migrate across the Great Father of Waters, they took with them a pole, which was to serve them as a guide as to the direction they should taking each morning. When night came on, they encamped, and when halted for the purpose, they would set the pole upright in the ground, and next morning they would see which way it leaned, and would judge that the Great Spirit had caused it to point in the direction he designed them to

Page 42

take. They also took along a very large dog, that would serve them as a guard, by barking and warning them of the presence of their enemies. With their guard and guide, they journeyed on toward the great river; but before reaching it, they passed by a great sink-hole, and here was the last they ever saw of their dog. At night, they fancied they heard his piteous howls, and so long as the distance was not too great, when they took any scalps in their battles with their enemies, they would send them back and throw them into the sink-hole to the dog.

After crossing the Mississippi, they continued their journey until they reached the present site of Huntsville in Alabama. Here, they were in great doubt and uncertainty as to what direction to take, as the pole was in an unsettled condition for several days. This was considered as a bad omen, and many of the tribe passed on toward the east, into the Carolinas; but the others waited for the pole to become settled, which it did after a time, and pointed in a north-west direction. Each night the pole was planted, and each morning it pointed in the same direction, until they had crossed the Tennessee river, just above the Muscle Shoals. The first morning after crossing the river the pole stood perfectly upright, leaning in no direction. They waited for several days, but neither wind nor weather had the effect to change its position, and, as the country was all that their hearts could wish, they decided that this was truly the "promised land," and here they made their home until the culmination of their sad and melancholy fate at the hands of superior tribes, and the intrigues of their pale-face brother.

Page 43

EARLY METHODS, MANNERS, AND CUSTOMS.

People who have grown up within the last thirty years can have but a very faint idea of the methods employed by our forefathers in nearly everything pertaining to domestic economy. Our grandmothers planted the cotton, gathered the fiber from the bowls when ripened, picked out the seeds by hand, carded the cotton with hand-cards into rolls, spun these rolls on a home-made spinning wheel into thread, colored this thread with home-made dyes, and wove it into cloth on a home-made loom. This cloth, coarse and strong, was cut out and made into garments of the most simple patterns, and worn with the same pride and satisfaction that the people now wear the ready-made fabrics with costly trimmings. No regard, whatever was paid to any dictates of fashion, and if some one wished to vary some old shape or form in a garment to suit themselves, they felt perfectly at liberty to do so, without any fear that they would become a laughing stock for being "out of style."

Woolen clothes, of course, were provided for winter wear, and the carding, spinning, and weaving were performed much in the same way as the cotton. Hemp shirts were frequently made for the slave boys and girls. These shirts could be cut, but not torn. Many a time, in crossing a fence, I have caught my shirt on a knot or splinter, and in jumping to the ground, have thrown my whole weight on my shirt, and have found myself hanging up against the fence, and my feet off the ground. Often in climbing saplings, I have hung myself on a knot by my tow shirt, but it never tore. The flax was prepared in a different way from

Page 44

the cotton and wool. The flax stalks were cut at a proper time and tied in bundles. These bundles were then placed in water so as to loosen the bark from the stalks. The bark was the part from which the thread was made. After the bark had become loosened, it was taken to a "break" which broke up the stems so that the bark, or fiber could be easily separated from the broken stems by drawing it repeatedly through the "hackle"--a board with a great number of sharp spikes driven through it. After other processes of preparation, it was ready to be spun into thread. But the spinning of flax thread required a different kind of wheel from the cotton or wool, and was called a "flax wheel." On account of the time and labor involved in the making of flax thread, not a great deal of it was made; but long after they ceased weaving the tow cloth, much thread was made for sewing leather, and for other purposes.

Much of the wool was used by being spun into yarn for knitting into stockings and gloves for the family. While the children would gather around the wide fire-place and pick cotton from the seeds; the mother or eldest daughter would be spinning thread; some one would be carding rolls; the father, apt as not, would be making a pair of shoes; a split basket, or "bottoming" a chair with splits. Sometimes the mother's "evening job" would be knitting, and when she would pay her neighbor a visit, she would invariably take her knitting along, and, during her stay, would frequently knit "the old man," as the husband was called, a pair of socks. But each member of the family, unless it was the baby, had some kind of work, and no one left the circle until one of the parents called out "bed-time." There were no

Page 45

lamps, and as a rule, the room was lighted by huge pine knots brought from a neighboring ridge. Often, however, home-made candles were used. These were made by pouring melted beef tallow into moulds in which a wick had been suspended. When these were cooled, the moulds were slightly heated, which loosened the candles. Mutton tallow was never used for this purpose, it being mixed with rosin and balm-of-gilead buds to form a very useful salve for cuts, sores, and burns.

The skins of the animals killed for meats, such as the cow and sheep, were tanned at home. The hides were soaked in a strong solution of lime and water, and the hair was removed. The surplus flesh still adhering to the hide, was then all scraped off, and finally the hide was soaked in a strong tan-ooze made from the bark of the chestnut oak, until experience taught the tanner that it was nowfit for leather. Generally, each neighborhood contained a professional cobbler who went from house to house, and cut out and lasted the shoes for winter wear, as few used them in the summer season. After the shoe had been "lasted," that is, the eye-seams sewed, and fitted and pegged to the last, it required very little skill to peg on the bottoms and heels, which the farmer usually did himself on wet days. The last and pegs were home-made, and comfort and durability, and not beauty, were the prime considerations. In those days we never heard of corns on the toes--nature's penalty for pride. A pair of shoes were supposed to last a person for a whole year, and they were not put to any unnecessary use. It was a custom to go bare-footed--both men and women--to almost the church, when they would sit down and put them

Page 46

on. At a short distance from the church on returning home, they were taken off.

There was a great demand for the labor of every person who possessed the slightest mechanical genius. The man who could make split baskets, bottom chairs, make scrub brooms, and the various necessary household contrivances was considered a very useful person, and usually got plenty of work to do, and made a respectable living by doing such work. The baskets were carefully made of selected white oak splits, of different sizes and shapes, and for different purposes. The common farm basket was made strong, and in sizes to hold a peck, half-bushel, three pecks, and a bushel; and each readily sold for its fill of corn or wheat, or an equivalent in some other kind of produce. Other kinds of baskets were made for the housewife for holding her clothes, and household articles.

The chair seats were made of the best quality of hickory and white oak splits, and woven in fancy and difficult designs, and with ordinary use would last twenty years.

The chair maker was a man of more mechanical skill than the last referred to. He turned his posts out of good hickory, only partially seasoned. The rounds were of seasoned locust, turned with a shallow groove in the end that was driven into the post. The post then seasoning and shrinking down on these rounds, would render it impossible for them to ever become loose. Chairs made by "Uncle James Webster" in Knox county, over a half a century ago, are as strong and intact now as when first made by him.

The chair maker, having a turning lathe, and being usually a mechanic of sufficient skill, would generally also

Page 47

make the spinning wheels. These had to be made and balanced in the most accurate manner, or else they would be continually "throwing the band," which was most provoking to the spinster. The reel was considered the work of a great genius, and it is to be regretted that the inventor's name is lost in the dim and distant past. It consists of a very clever arrangement of interworking cog wheels, so that in turning the large wheel upon which is wound the thread, a sharp "click" indicates that a "cut" of thread has been wound. As services for spinning and weaving were charged for, as so much the "cut," it is difficult to see how the reel could have been dispensed with.

The main working parts of the loom could be made by almost any ordinary mechanic, but the "slays" were exceedingly tedious and difficult to make; and this gave rise to a new industry, and furnished employment to a "slay maker," who enjoyed quite a monopoly of his line, as he had few competitors. Old ones were continually giving out, and as these had to be mended, or replaced by new ones, he found plenty of work to do, and his services were in constant demand.

There was also the cooper whose trade was a very important one in the early settlements. He made the buckets, churns, lard stands, pails, barrels, and kegs. As these articles were in constant use, he was kept quite busy until the families were all supplied. The smaller vessels were made mostly of red cedar, and would last a life-time. The barrels and lard stands were made of good white oak, and were likewise very durable. Vessels made by these old-time coopers may be found at the present time, as sound and

Page 48

serviceable as they were half a century ago, but considered somewhat out of date.

But perhaps the most useful of all the mechanics in the early settlements was the blacksmith. His work covered a wider range of useful articles than any of the other mechanics. It is easy to see how in cases of emergency, the articles made by the other artisans mentioned, could have been substituted for; but it does not appear how a community could have existed without the services of a blacksmith. He made the plows, hoes, mattocks, wagons, and chains for the farmer; the augers, planes, nails, hammers, and chisels for the carpenter; the shovel, tongs, hooks, and andirons for the fireside; all the nails, hooks, staples, rings, bands, rods, and every kind of tool used by everybody. His iron came to him, not as it reaches the blacksmiths of today, in convenient sizes and shapes, as rods and band iron, but in large bars, several inches broad, and several inches thick, which had to be forged out and hammered down to the required sizes. These huge bars of iron were heated in a fire made of charcoal, burnt of pine or chestnut wood, often in a pit in the shop yard. While the blacksmith was burning his coal-pit, or using the light, sparkling fuel on his heavy bars of iron, the people of Virginia and Pennsylvania were bursting up, and building roads with the very things that revolutionized blacksmithing--stone coal-- and did not know its value. It is amusing to one who remembers the introduction of stone coal into the old-time blacksmith shop. There was almost as much prejudice evidenced by the people generally as by the blacksmith. Some said that it would burn and scorch the iron so that it would be brittle. In many agreements between

Page 49

the customer and smith for work, it was stipulated that the iron work was not to be done with stone coal. But, like all other improvements, it came into use gradually, and its superiority over charcoal for a high, quick heat, had to be established by experience. Another fact, equally patent, is, that no mechanic or artisan has been so completely put out of business, or his trade rendered almost next to useless by the invention of machinery as the blacksmith. Once, the most indispensable, now perhaps, his entire disappearance from the mechanical trades of the country, would produce the least inconvenience of any. Every article that the blacksmith was once looked to to make, is now produced by machinery, and can be bought much cheaper than it could be made by him.

OLD TIME WORKINGS.

The most distinguishing feature or characteristic of early pioneer days was the many social gatherings of neighbors for mutual assistance in the performance of labor too heavy for a single individual. The land was grown over with heavy timber and it all had to be cleared and fenced. One man could not manage the heavy logs alone, and so the neighbors would be informed that on a certain day they were to meet at this man's "new ground," and participate in a log-rolling and rail-splitting. Accordingly they all came with their axes and mauls. Some would be put to chopping down the trees, some to chopping off the cuts, some to splitting rails, and some to rolling together into large heaps such logs as would not split into rails. The boys would also come to pile, in

Page 50

large heaps, the brush and small limbs. These same brush heaps would, during the winter, become the roosting places of thousands of small birds, the killing of which, after dark, would afford a fine, but a very cruel sport for these same boys.

FIRE HUNTING.