The African Preacher.

An Authentic Narrative:

Electronic Edition.

White, William S. (William Spotswood), 1800-1873

Funding from the National

Endowment for the Humanities

supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text scanned (OCR) by

Laura Button and LeeAnn Morawski

Images scanned by

Laura Button and LeeAnn Morawski

Text encoded by

Aletha Andrew and Natalia Smith

First edition, 1999

ca. 200K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Call number PS3179.W48A4 (Davis Library, UNC-CH)

The electronic edition

is a part of the UNC-CH

digitization project, Documenting the American

South.

All footnotes are

moved to the end of a paragraph in which the reference occurs.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks,

em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and

left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and

left quotation marks are encoded as ' and '

respectively.

All em dashes are

encoded as --

Indentation in lines

has not

been preserved.

Running titles have

not been preserved.

Spell-check and

verification made against printed text using Author/Editor

(SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

LC Subject Headings:

- Jack, Uncle, 1746?-1843.

- African American clergy -- Virginia -- Nottoway County -- Biography.

- African Americans -- Virginia -- Nottoway County -- Religion.

- African Americans -- Virginia -- Nottoway County -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Virginia -- Nottoway County -- Biography.

- Slaves -- Religious life -- Virginia -- Nottoway County.

- Jones, James, 1772-1848.

- Slaveholders -- Virginia -- Nottoway County -- Biography.

- 2000-06-05,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

1999-07-21,

Natalia Smith, project manager,

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

1999-07-20,

Aletha Andrew

finished TEI/SGML encoding

- 1999-07-13,

Laura Button and LeeAnn Morawski

finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

THE

AFRICAN PREACHER.

AN AUTHENTIC NARRATIVE.

BY THE

REV. WILLIAM S. WHITE,

Pastor of the Presbyterian Church, Lexington, Virginia.

PHILADELPHIA:

PRESBYTERIAN BOARD OF PUBLICATION,

No. 265 CHESTNUT STREET.

Page verso

Entered according to the Act of Congress in the year

1849, by

A. W. MITCHELL, M.D.,

In the Office of the Clerk of the District Court for the Eastern District

of Pennsylvania.

Stereotyped by Wm. S. SLOTE, No. 19 St. James Street,

Philadelphia.

Page 3

To the Rev. BENJAMIN H. RICE, D. D.,

Pastor of Hampden Sidney Church, Va.:

REV. AND DEAR BROTHER--BY your counsel, my humble labours as a Domestic Missionary were commenced in the county of Nottoway; and to your sympathy and co-operation is to be ascribed a large portion of the little good which may have resulted from those labours. It is, therefore, most reasonable that a narrative resulting, as this does, from that mission, should be inscribed to you.

Accept it, then, as an humble expression of the respect, the gratitude, and the love of

Your Friend and Brother,

WILLIAM S. WHITE.

THE MANSE, Lexington, Va., March 10, 1849.

Page 5

THE AFRICAN PREACHER.

THE prominence given in the Scriptures to the characters and lives of such persons as Ruth, Esther, and Nehemiah, proves, that "God hath chosen the poor of this world, rich in faith, and heirs of the kingdom which he hath promised to them that love him"-- that he hath moreover "chosen the foolish things of the world, to confound the wise, and the weak things of the world, to confound the things that are mighty." Since the days of inspiration ended, the dealings of God's providence and the dispensations of his grace, have beautifully harmonized with the revelations of his word. Hence, in all ages of the world, down to the present hour, many of the loveliest

Page 6

specimens of true piety, have been found in the humblest walks of life. Here, God's wisdom, love, and mercy shine with a lustre all their own; and here, religion displays its richest fruits.

The narrative now to be given is designed to illustrate these remarks. The subject of it was a native of Africa. When about seven years of age, he was kidnapped, brought to this country, and enslaved. He was supposed to belong to one of the last cargoes of this sort, ever landed on the shores of Virginia. He was purchased at Osborne's, on James' river, by a Mr. Stewart, and was subsequently taken to the county of Nottoway, Virginia, where the whole of his long and interesting life was spent.

He grew to manhood, ignorant of letters, and a stranger to God; engaged in the occupations common to those in a state of bondage. The region of

Page 7

country in which he lived, was, at this period, deplorably destitute of the means of grace. The gospel was seldom preached, the Sabbath scarcely known as a "day of sacred rest," and few were found willing to incur the odium of a public profession of religion.

Before we proceed further with our narrative it is important to state, that "Uncle Jack," for so he was universally called, possessed great acuteness of mind, and understood and spoke the English language far better than any native of Africa we have ever known. His pronunciation was not only distinct and accurate, but his style was chaste and forcible. His great superiority in this respect must be ascribed to the following causes:-- First, to his having left his native land at so early an age. Next, to the freedom with which he was permitted and encouraged to mingle in the best society the country afforded;

Page 8

and above all, to the familiar acquaintance he soon formed with the language of the Bible. The reader must not be surprised, therefore, that nothing occurs in what we quote from his own lips, of the jargon peculiar to the African race. Nobody ever heard the good old preacher say massa for master or me for I.

It was during the period of intellectual and moral darkness already referred to, and when he had probably reached the fortieth year of his age, that he became anxious on the subject of religion. The account he gave of his early religious impressions, was very simple. He said nothing of dreams and visions, as is so common with persons of his colour. His attention was first arrested, and his fears excited, by hearing from a white man that the world would probably be destroyed in a few days. On hearing this, he

Page 9

asked his informant what he must do to prepare for an event so awful. He was told to pray. "This," he said, "I knew nothing about. I could not pray." At length he was enabled to recall some portions of the Lord's prayer, which he continued to repeat for a considerable time. But these efforts brought him no relief.

That which thus commenced in mere alarm, soon led to a deep and thorough conviction of his guilt, helplessness, and misery, in the sight of God. He now exerted himself in various ways, and with untiring zeal, to obtain a knowledge of the truth as it is in Jesus. There were literally none in his vicinity, either in the ministry, or among the private members of the church, qualified to teach and to guide an inquiring mind like his. The Presbyterian church, then recently established in Prince Edward, was within

Page 10

thirty miles of his residence. The ministers

of the gospel from that county, made

occasional excursions into Nottoway.

From these he soon obtained the help he

needed. His own statement on this subject

is as follows: "I had a very wicked heart,

and every thing I did, to make it better,

seemed to make it worse. At length a

preacher passed along; they called him Mr.

President Smith.*He turned my

heart inside out. The preacher talked

so directly to me, and about me, that I

thought the whole sermon was meant

for me. I wondered much, who could

have told him what a sinner I was.

But after a while there came along a young

man they called Mr. Hill;** and about the same

time another, with a sweet voice, they called Mr.

* The Rev. John Blair Smith, D. D., then President of

Hampden Sidney College.

** (The Rev. Wm. Hill, D. D., of Winchester, Va.

Page 11

Alexander.* These were powerful preachers too, and told me all about my troubles; and brought me to see, that there was nothing for a poor, helpless sinner to do, but to go to the Lord Jesus Christ, and trust in him alone for salvation. Since that time, I have had many ups and downs; but hitherto the Lord has helped me, and I hope he will help me to the end."

* The Rev. Archibald Alexander, D. D., afterwards Professor of Theology, Princeton, New Jersey.

He now became deeply interested in hearing the Scriptures read. As his knowledge of the Bible increased, he found, to use his own language, "that it knew all that was in his heart." He wondered how "a book should know so much."

He was still unable to read, but now determined to learn. To this end he applied to his master's children for assistance; promising to reward them for

Page 12

their pains with nuts and other fruits, as tuition fees. By the aid of his youthful instructors, his object was soon attained, and he read the word of God with ease. The sacred volume now became the constant companion of his leisure hours. So rapid was his progress in divine knowledge, and such his prudence, good sense, and zeal, that many of the most intelligent and pious people of his neighbourhood expressed the desire to have him duly authorized to preach the gospel. The Baptist church, of which he had become a member, took this matter into serious consideration; and after subjecting him to the trials usually imposed by that denomination, licensed him to labour as a herald of the cross.

Upon the duties of his new and responsible office, he entered with a truly apostolic spirit. He commenced his ministry in a neighbourhood where there

Page 13

were literally none to break statedly to the people the bread of life. His labours were abundant and faithful. He was often called to preach at a distance of more than thirty miles from his home. He was still a slave, and never seemed to think of any better state, until his attention was called to it by others. He belonged to the undivided estate of his original purchaser, who was now dead. Some of the legatees of this estate were willing to emancipate him, but others were not. This, however, constituted no serious obstacle. He had rendered himself so useful, and had gained the confidence and good will of the community to so great an extent, that a sum of money was soon raised by subscription, quite sufficient to satisfy the demands of those who were unwilling to liberate him. Some idea may be formed of the estimation in which he was held, when it is known that many

Page 14

contributed liberally to the fund thus created, who were not professors of religion. Having thus secured his freedom, he settled on a small tract of land, of which he became the proprietor, chiefly through the munificence of others, and lived in a way which satisfied his humble wishes. Here he literally earned his bread with the sweat of his brow, while he faithfully dispensed to others the bread of life, with scarcely any compensation, except the consciousness of doing good.

The late Rev. John H. Rice, D. D., had a brief interview with our preacher, in which he was deeply interested. This occurred during the summer of 1826, when the old man had nearly reached the 80th year of his age, and one year before our acquaintance with him commenced.

Referring to this interview afterwards, Dr. Rice said, "The acquaintance

Page 15

of this African preacher with the Scriptures is wonderful. Many of his interpretations of obscure passages are singularly just and striking. In many respects, indeed, he is one of the most remarkable men I have ever known."

At this period, Dr. Rice was editor of the Virginia Literary and Evangelical Magazine; and entertaining the views expressed above, it is not surprising that the pages of this valuable periodical should contain a brief but interesting memoir of "Uncle Jack." It may be found in the first number of Vol. 10. In this memoir, Dr. Rice expresses himself thus: "There lives in a neighbouring county, an old African, named Jack, whose history is more worthy of record than that of many a man whose name has held a conspicuous place in the annals of the world. There is a book which, I have no doubt, contains the name of Old Jack, but not those,

Page 16

I fear, of many great men and nobles of this world. It is 'the Lamb's book of life.'

"Jack possesses the entire confidence of the whole neighbourhood in which he lives. No man doubts his integrity or the sincerity of his piety. All classes treat him with marked respect. Everybody gives unequivocal testimony to the excellence of his character.

"He possesses a strong mind, and, for a man in his situation, has acquired considerable religious knowledge. His influence among people of his own colour is very extensive and beneficial.

"Old Jack is as entirely free from all bigotry and party spirit, as any Christian I have ever seen. He acknowledges every man to be a brother, whom he believes to be a Christian. A very striking proof of his humble, teachable, catholic spirit, is given in his conduct towards two Presbyterian missionaries,

Page 17

who were successively sent to the part of the country where he resides. On their arrival, he seemed very cautiously to investigate their character. The result was a conviction that they were pious and devoted men; and a hearty recognition of them as ambassadors of Christ. He found, too, that they knew a great deal more than he did, and resolved to employ his influence in bringing the black people in his neighbourhood under their instruction. He also frequently consulted them in regard to matters of difficulty with himself, and used their attainments for the increase of his own knowledge, and for enabling him the better to instruct the numerous blacks who looked up to him as their only teacher.

"It has before been said, that the conduct of this old Christian had secured the respect and confidence of the white people. As evidence of this, some

Page 18

time ago a lawless white man attempted to deprive him of his land, under a plea that his title was not good. As soon as the design was known, a number of the first men in the neighbourhood volunteered to assist him in maintaining his right, and a lawyer of some distinction, not then a believer, rendered gratuitous service on the occasion, because everybody said, Uncle Jack was a good man.

"But while the white people respect, the blacks love, fear, and obey him. His influence among them is unbounded. His authority over the members of his own church is greater than that of the master, or the overseer. And if one of them commits an offence of any magnitude, he never ceases dealing with him, until the offender is brought to repentance, or excluded from the society. The gentlemen of the vicinity freely acknowledge, that this influence is highly

Page 19

beneficial. Accordingly, he has permission to hold meetings on the neighbouring plantations whenever he thinks proper. He often visits the sick of his own colour, and preaches at all the funerals of the blacks who die any where within his reach."

The high source from whence this extract is taken, and the extent to which it must sustain and enforce the subsequent portion of our narrative, is a sufficient excuse for its introduction.

One of the most gifted and honoured sons of old

Virginia,* who resided for more than forty

years within one mile of the subject of this

narrative, who was thoroughly acquainted

with his public and private life, and who even

acknowledged himself under obligations

to this humble preacher of righteousness as

a spiritual instructor, furnished

* Dr. James Jones, of Mountain Hall.--See Appendix.

Page 20

the following just and beautiful delineation of his character.

"I regard this old African as a burning and shining light, raised up by Christian principles alone, to a degree of moral purity seldom equalled, and never exceeded in any country. Think of him as an African boy, kidnapped at seven years of age, torn away from his heathen parents, thrust into a slave-ship among hundreds of the most degraded beings, transported across the Atlantic, landed on our coast, bought by a very obscure planter in what was then the back-woods of Virginia, here kept in bondage at the usual occupation of slaves, under circumstances but little calculated to improve the mind, or mend the heart; without letters, without instruction, until a glimpse of divine truth, caught by hearing the Bible read, arrested his attention. Seizing on the truth thus

Page 21

obtained, and appreciating its excellence, almost without assistance, he soon learns to read the sacred volume. His researches are now pursued with growing zeal, and signal success, until he is enabled to penetrate into some of its most sublime mysteries, to feel the force of its obligations, to enjoy its consolations, and to become an able and successful expounder of its doctrines to others.

"As a preacher of the gospel, he gained the good will and secured the confidence of all who were capable of appreciating true excellence of character, gained admittance into the best families, and was there permitted to enjoy a freedom of intercourse that I never witnessed in any other similar case.

"All these views of this old man's character, have excited in my mind somewhat of an enthusiastic admiration

Page 22

seldom felt by me for any member of the human family, of any rank or station. Such effects under all the circumstances of the case, must be traced up to a cause altogether superhuman, and set the seal to the superlative excellence, the divine authenticity of the Christian system."

A lady, whose rank, intelligence and piety, place her among the first of her sex, and who still lives to bear testimony to the literal truth of this narrative, has kindly furnished the following statement written more than ten years ago.

"My acquaintance with the old man commenced about thirty years since, when there was scarcely a vestige of piety, especially among the higher classes in this community. The Baptist church to which he belonged was in this region nearly extinct. The few members who remained, he regularly visited and

Page 23

instructed. His first visit at our house was intended for a Baptist lady who was spending some time with us. In his conversation with this lady, I was surprised at the readiness and propriety with which he quoted the Scriptures; and especially at the sound sense which characterized his practical reflections on the passages quoted. This induced me to seek a more intimate acquaintance with him; and as he found I was interested in his conversation, he often called on me.

"He has been eminently useful to many persons of my acquaintance. When under spiritual concern, they would apply to no other teacher. During the period of dreadful darkness, to which I have already alluded, he went from house to house, doing good. About this time, he became signally instrumental in the conversion of his former master's youngest son. This youth gave

Page 24

abundant evidence of vital piety, both in his life and his death.

"I think the most prominent traits in his character, are meekness, humility and rigid integrity. He possesses naturally a strong mind, a very retentive memory, with the happiest talent for illustrating important truth, by the objects of sense, and the ordinary employments of life. I trust, dear sir, you will be able to furnish the public with an instructive account of this humble and obscure, but interesting and useful old man."

This communication was designed to aid in the preparation of a series of biographical sketches of "The African Preacher," which appeared in the columns of the Watchman of the South in 1839; and was so used. The writer still lives, and would doubtless acknowledge that in her transition from darkness to light, and from the power of

Page 25

Satan unto God, she was mainly indebted, through divine grace, to the visits and the conversations of the good old African, referred to in her letter.

Uncle Jack's views of the fundamental doctrines of the Bible, were thoroughly evangelical. He was particularly fond, to use his own words, of "that preaching which makes God everything, and man nothing." The total depravity of man--the absolute sovereignty of God in electing him to salvation through the imputed righteousness of Christ--the necessity of regeneration by the Spirit, through the belief of the truth--the growth in grace and final salvation of all who truly repent and believe the gospel; these were his favourite themes, both in his sermons and conversation. And these, with all their kindred topics, he could illustrate by allusions to nature and art, with a clearness which left no obscurity

Page 26

about his real sentiments. He was particularly fond of the Epistle to the Romans, and often spoke of it, as containing "the very marrow of the gospel." He often bestowed much time on a single passage. On one occasion, he called our attention to the third verse of the eighth chapter of Romans, saying, "Master C. and I have been studying a great deal over that verse for the last three weeks, and we do not fully understand it yet. Do tell me all about it."

Anxious to know what his own construction was, we insisted that he should give us his opinion, promising to give him ours when he had concluded. With this proposition he was very reluctant to comply, but finally consenting, he proceeded as follows. We give the exposition in his own order, and almost verbatim as he gave it to us. "Well," said he, "I will do

Page 27

the best I can. The verse begins thus: 'For what the law could not do.' And what is it the law can't do? Why, it can't justify us in the sight of God. Why not? Because 'it was weak through the flesh.' There is no weakness in the law. That is as strong as its Author. But the weakness is in man's flesh. Observe, this is a weakness 'through the flesh.' That is, the weakness is in man's corrupt nature. Now, what is to be done for man in his helplessness and guilt? The text tells us plainly, 'God sending his own Son'--for what? Why, to do for ruined man what the law could not do on account of his sinfully weak nature. And when God sent his Son, how did he come? 'In the likeness of sinful flesh.' I suppose that means, he came as a man, though not a sinful man; for he knew no sin. And why did he come? The text answers, 'and for sin, condemned

Page 28

sin in the flesh.' That is, on account of sin in man, he suffered the condemnation due to that sin in his own person. So," says the old African--his dark visage brightening with the emotions within--"what God's law cannot do, his own Son can do. Thanks be to God for his unspeakable gift!"

We could only join in his closing exclamation, assuring him that, according to our best judgment, he had adopted the true interpretation of the passage, and we left him, blessing God, as we shook his hand, for bestowing such grace and knowledge upon one so humble and so unpretending. His knowledge of human nature was profound, because it was derived wholly from the Bible, confirmed by his own observation. Hence his extensive usefulness, not only among those of his own colour, but also in a large circle of whites, embracing many of the most

Page 29

intelligent, wealthy, and refined people of the county.

In the familiar intercourse to which he was admitted by the latter class, he was never known to offend by any thing like forwardness. Says one who knew him well: "His humility has always been of the most rational kind--entirely removed from all cant and grimace. Before he became superannuated, the great field of his operations as a preacher was the funeral sermons called for by the owners of deceased slaves. He was universally employed in this way, with the hearty consent of persons of all descriptions in this community. I have known him to be sent for to a distance of more than thirty miles to attend to a service of this kind. In every instance he would receive the most polite and friendly attentions of the white portion of the family and even by the irreligious, was frequently

Page 30

remunerated in money for his services."

Through life, he manifested a surprising thirst for knowledge. He embraced with avidity every opportunity of getting instruction, both in public and in private. Nothing pleased him more than the opportunity of conversing, with ministers of the gospel. Mountain Hall, the delightful residence of the late Dr. Jones, was a home for Christ's ministering servants as they journeyed through that part of the country. The African Preacher lived at the distance of a mile from this place. He seemed to know, almost by intuition, when a minister called to spend the night with the good doctor and his lady. And however dark or even stormy the night might be, when the bell rang for evening family worship, the good old African would be seen with tremulous steps slowly entering,

Page 31

and with deep solemnity, seating himself in a retired part of the room to attend upon the service. A stranger would not be likely to observe him, unless indeed the person conducting the worship should happen to sing Windham, or Mear, or Old Hundred, to some appropriate psalm or hymn. Then his attention would very probably be arrested by a voice, not remarkable for its melody, nor yet remarkable for its strength--but a voice so solemn, so tremulous with the emotions which seemed to accompany it from the depths of a heart all alive to God's praise, that he could no longer remain unobserved.

When the service closed, he resumed his seat--so modest as never presuming to seek an introduction to the reverend visitor. The polished, but pious inmates of that mansion, were his special patrons and friends, and had given him

Page 32

a prescriptive right to that corner and to that chair. But he was never permitted to remain unnoticed. The visitor was invariably taken to the place where the old man sat, and told, "this is our friend and neighbour, Uncle Jack, who has come to-night expressly to join in our worship, and to make your acquaintance, with a view to his improvement in divine knowledge." Then followed an interview, in which the teacher rarely failed to learn as much as the scholar.

He greatly delighted in hearing the gospel preached by those who were well educated, as well as pious; and never seemed to enjoy a sermon which consisted mainly in empty declamation. We have often heard him say, "I don't like to hear more sound than sense in the pulpit."

He uniformly opposed, both in public and private, every thing like noise and

Page 33

disorder in the house of God. His coloured auditors were very prone to err in this way. But whenever they did, he suspended the exercises until they became silent. On one of these occasions, he rebuked his hearers substantially as follows: "You noisy Christians remind me of the little branches (streams) after a heavy rain. They are soon full, then noisy, and as soon empty. I would much rather see you like the broad, deep river, which is quiet, because it is broad and deep."

On another occasion, when a very large assembly had convened, and when he had reason to suppose there might be a good deal of mere animal excitement, before he sung or prayed, addressing himself to one of his audience by name, he said, "Suppose your master had directed you to go to Petersburg to-morrow; and suppose, on your telling him you knew nothing of the road,

Page 34

and therefore could not go, he should repeat the command, and say, "You shall go, whether, you know the way or not, and shall be severely punished if you fail to go." Now you are in great trouble, and going to look for some one who can tell you the way, you happen to find a good many people together, all of whom say they know the way perfectly. You tell them the trouble you are in, and beg them to tell you the way to Petersburg. Now, there happens to be one in that crowd, older than the rest, and who is thought to know the way rather better than they. So, all wait for him to talk. Now, suppose that, just as this old man begins to tell you about the road--where this fork, and where that is--when you must turn this way, and when that, all his companions commence clapping their hands, groaning and shouting so, that you can't hear

Page 35

distinctly a word the old man says. Could he possibly teach you the road to Petersburg, unless they would keep still? Now, here are a great many sinners, who must find the road to heaven or perish for ever. I am about to tell them, as well as I can, how they may find that road, and escape that destruction, and don't you Christians bother me, and hinder their learning by your noise. Let every mouth be stopped, and let all keep quiet until I am done."

His sentiments and his practice on this subject seem the more remarkable, when it is remembered, that at this time nothing was more common, not only among the blacks, but also among whites, than noise and confusion during public worship. Indeed, they were thought the best Christians who shouted the oftenest and prayed the loudest. This sentiment he literally abhorred, and did his utmost to exterminate.

Page 36

He was particularly fond of a tract published by the American Tract Society, entitled, "The importance of distinguishing between true and false conversions." He often applied for this tract, that he might take it to some white neighbour, who had recently professed conversion; expressing the fear, that the individual for whose benefit he wanted it, was in danger of resting in a groundless hope. With those of his own colour, he talked thus on this subject: "You who can read the Bible, should read it much; and you who cannot, should embrace every opportunity of hearing it read. If you do not, how will you ever know that your religion is such as God will approve? God alone knows, and he alone can tell us, what will satisfy him, and this he has done in his word. Why, persons fond of smoking, can't tell whether their pipe is lighted, if they smoke in the dark;

Page 37

much less can you tell whether your heart is right in the sight of God, unless the light of his word is poured upon your experience."

The reader will be interested also in knowing something of his sentiments in regard to revivals of religion. More mistaken views on this subject could hardly prevail any where, or at any time, than prevailed in the region of country in which the African Preacher lived, and during the time of his ministry. His sentiments may be fairly and fully learned from the following incident.

On a certain occasion, he attended a protracted meeting, conducted by some of the best white preachers in that part of the country; at which "the new measures" were used, and at which there was a great deal of excitement and no little noise. On his return, he called to see me, and, during his visit,

Page 38

gave me the following account of the meeting. "There were a great many people, and a great deal of talking, and singing, and praying. They call it a revival; and if by a revival, they mean a great increase of confusion and noise, they are right. But so it is, I had no enjoyment at the meeting. I heard very little of what I call real preaching. I was constantly thinking, and it may be, this was a temptation of the devil--any how, I was constantly thinking Of what I have sometimes noticed in new grounds. If a man clears up a piece of land in the summer, and has not time to cut down and take away all the trees, but belts a good many, and leaves them standing about in the field, the leaves die, but don't fall. Now, when winter comes, and the wind blows hard, I always noticed that one of these belted trees made more noise in the wind, than a half dozen green, living trees.

Page 39

These noisy Christians look to me so much like belted trees with the leaves on, in a windy day, that I could not enjoy the meeting at all. And yet the fault might have been in me."

Few things delighted him more than to be made acquainted with the views of standard evangelical authors on doctrinal subjects. He was at all times particularly interested in clear and sound expositions of such passages of Scripture as are hard to be understood. A friend says, "After I had read to him, at some length, the opinions of one of our ablest divines on a disputed point in theology, he said, 'Well, I have long wanted to have that matter explained, but all I could gather about it, was like picking up a few scanty crumbs and dry pieces of crust, which could not satisfy my hunger; but now, you have given me a great loaf, that I may eat and be full at once.' "

Page 40

At another time, on having a very difficult text explained to him, he said, "Whenever I came to that text, I was like a little child two or three years old, trying to go from one room of his father's house into another. After trying again and again to reach and raise the latch, but all in vain, his father comes along, and does, without the least difficulty, what the child could not possibly do. Just so with me. You have opened the door, and now I can go on in."

He was a close observer of passing events-- an accurate discerner of the signs of the times. He looked at every thing in its bearing on the cause of Christ. He said to us on one occasion, "Real Christians are the salt of the earth; and I do believe that this world would have been destroyed long ago, but for them. Does not the word of

Page 41

God say, that for the elect's sake those days shall be shortened?"

There were two individuals in the circle of his acquaintance, remarkable, not only for their own destitution of religious principle, but also for doing all they could to suppress it in the large families of which they were the heads. During their lives, no member of either household made any advance towards forming a connection with the church. Soon after their deaths, which happened nearly about the same time, the widow and several of the children of each, became pious, active members of the church. When his attention was called to this fact, he said, "I have often seen a large, spreading oak, standing alone in a field, with nothing growing under it--but only cut that tree down and take it away, and a little culture will make the land very productive."

We have already learned that he was

Page 42

admitted to terms of great familiarity with persons of every grade in society; and yet his deportment never savoured of arrogance or presumption. There was but one class of persons with whom he ever used a freedom which the most fastidious could censure. These were such as scoff at sacred and divine subjects. Persons of this sort would sometimes jeer him about his religion; and endeavour to make Christ and his precious cause subjects of buffoonery and ridicule. The old African was far more jealous of his Master's glory than of his own ease or reputation. On such occasions, his usual diffidence and reserve would give place to a firm but dignified defence of the truth; and most happily could he "answer a fool according to his folly." Nor did one of this fraternity ever encounter him without being seriously worsted.

A man addicted to horse-racing and

Page 43

card-playing, stopped him in the road one day, and addressed him as follows: "Old man, you Christians say a great deal about the way to heaven being very narrow. Now, if this be so, a great many who profess to be travelling it, will not find it half wide enough." "That's very true," said the good African, "of all who merely have a name to live, and of all like you." "Why refer to me?" asked the man; "if the road is wide enough for any, it is for me." "By no means," was the pertinent reply; "when you set out, you will wish to take along a race-horse or two, and a card-table. Now there's no room along this way for such things, and what would you do, even in heaven, without them?"

Another individual of large fortune, who was accustomed to treat the subject of religion rather sportively, and who at the same time prided himself

Page 44

on his morality, said to him, "I think, old man, I am as good as need be. I can't help thinking so, because God blesses me as much as he does you Christians, and I don't know what more I want than he gives me; and yet I never disturb myself about preaching or praying." To this the old preacher replied with great seriousness, "Just so with the hogs. I have often seen them rooting among the leaves in the woods, and finding just as many acorns as they needed, and yet I never saw one of them look up to the tree from which the acorns fell."

He was fond of considering piety, both internal and external, as progressive in its developments. He opposed with the utmost firmness and faithfulness, the idea of one's getting religion, as the phrase is, and then folding his hands in utter idleness. He was fully aware that this error prevailed to a

Page 45

deplorable extent, among those of his own colour, and he spared no pains to resist and eradicate it. He was accustomed to say, "I have no notion of that religion which is better at first than it ever is afterwards. When Christians hear a sermon on the text, "Turn ye, turn ye, for why will ye die?" they are apt to conclude that it don't suit them, because they have turned long ago. Now, the truth is, to be the real children of God, we must continue to turn as long as we live. For my own part, I often feel as if I had as much turning to do now, as I had when I first set out."

His views on this subject were unusually enlarged and scriptural. They reached into eternity. Nothing less than the expectation of an eternal progression, in knowledge, holiness, and usefulness satisfied his desires. Of this, we are furnished with a striking

Page 46

illustration, in the following incident. A pious young man, of considerable intelligence, conversing with him on growth in grace, said, "We should strive to grow until we die." "Yes," replied our preacher, "and hope to grow after we die. I trust in God I shall grow for ever."

Standing one day in sight of a field of tobacco, he said to me, "Some fifty years ago, I expected the time would come, when I should be of some account in the Lord's vineyard. But now, I am very old, and have given up this hope." Then pointing to the tobacco, which grew near us, he said, "That is very promising tobacco, but it must be cut and cured, before it will be of any service to its owner. And so it is with me. All that now comforts me on this subject, is the hope that God will make some good use of me in another and better world. The

Page 47

redeemed of the Lord are said to serve him in heaven. What a service that must be! How unlike any thing seen or known on earth!"

Here let the reader pause and consider, that this old African could barely read, and never learned to write. He was taught in the school of Christ, and only there. We never knew him read, nor do we think he cared to read, any book except the Bible, or something of a kindred character. He was literally taught of God, and thus became wise unto salvation. With the jet black colour, and all the features of the African race fully developed, such were the beauties of his mind and heart, as to render him an object worthy of the highest respect--the most profound veneration. Often have we rejoiced to sit at his feet and learn, and with no little delight do we anticipate the day when we shall walk, side by side,

Page 48

along the banks of the river of life, and partake together of the fruits of that tree, whose leaves are for the healing of the nations.

Another very striking characteristic of the African Preacher was solicitude for the prevalence of pure and undefiled religion He sought, in every legitimate way, the advancement of Christ's cause. Most truly could he say, "If I forget thee, 0 Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning." Perhaps few, if any, have ever lived, who entered more fully into the spirit of the 80th Psalm--or who, with reference to the interests of Zion, could with greater sincerity or deeper earnestness, adopt the beautiful language of one of our hymns:

"If e'er my heart forget

Her welfare or her woe;

Let every joy this heart forsake,

And every grief o'erflow.

Page 49

"For her my tears shall fall

For her, my prayers ascend;

To her my toils and cares be given,

'Till toils and cares shall end."

All who visited him might expect to be questioned on this subject, as closely as good manners would warrant. No one, who made the attempt, ever failed to interest him deeply on the subject of missions. We have often seen the tear roll down his dark and furrowed cheek, as he listened to some thrilling statement respecting the spread of the gospel among the heathen. He fully believed, that "the field is the world"--that the great commission of the ascending Saviour binds the Church to preach the gospel to every creature, and make disciples of all nations. Here his faith and zeal were such as to put to shame many who, with advantages far superior to his, are still strangers to the missionary spirit,

Page 50

which is but another name for the spirit of the Gospel--the spirit of Christ.

When he prayed, as we know he did with unusual faith and fervour, "Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth, as it is in heaven," his far reaching mind and heart extended to every nation and kindred and tribe, upon the whole earth. He had known what it was to live amidst the darkness of heathenism, and what it is to enjoy the genial light of the Sun of righteousness.

On one occasion, after listening with fixed attention and deep feeling to a statement of a discouraging character respecting the state of religion in a neighbouring county, he said, "There seems to be great coldness and deadness on the subject of religion every where. The fire has almost gone out, and nothing is left, but a few smoking chunks lying about in places." How striking is the thought of one's having

Page 51

just religion enough "to smoke," but not enough to burn. No light, no beat--only a little smoke. Who that has the fire of divine love in his heart, can be content to lead such a life? Indeed it is extremely doubtful, whether a principle of such potency can exist, and yet exert no more influence. Let the inactive, useless member of the church, ponder the homely but expressive language of the good old African, and hang his head for shame, that he should hold no higher place, and act no better part in the vineyard of his Master, than that of a "smoking chunk" lying by the way-side.

Speaking of the causes of a low state of piety, he said, "Christians don't love each other enough. They don't keep close enough together. They are too much like fire-coals, scattered over a large hearth. Coals in that condition, you know, soon die out. Only gather

Page 52

them up, and bring them close together, and they soon become bright and warm again. So it is with Christians. They must be often and close together--in the church--at the prayer meeting, and thus help one another along."

His attention was frequently called to the purposes and plans of the American Colonization Society. He always said it would succeed if the natives were duly restrained. Young as he was when taken from that country, he seems to have formed a just estimate of the African character. Comparing their superstitious practices and degraded condition, with the privileges enjoyed under the Christian system, he was often heard to thank God that he had been brought to America. "For," he would say, "coming to the white man's country as a slave, was the means of making me free in Christ Jesus." He remembered very distinctly having often been forced

Page 53

to participate in the idolatrous rites and ceremonies practised by his parents; and he seldom exhibited deeper emotion than when referring to these things. From this subject he seldom passed, without adding, "If I were only young enough, I should rejoice to go back and preach the gospel to my poor countrymen. But," he would say, "it would be a great trial to live where there are no white people."

In every situation, whether of freedom or of bondage, he had found in the white man a friend and a brother. And we scruple not to say, that the black man has no better friend on all this earth, than he finds in the educated, pious son of the good old commonwealth, in which the African Preacher lived, preached and died--respected while he lived, and lamented when he died.

Perhaps no Christian grace shone more brightly in his character, than

Page 54

humility. The attentions bestowed upon him by persons of the highest standing, were remarkable. He was invited into their houses--sat with their families--took part in their social worship, sometimes leading in prayer at the family altar. Many of the most intelligent people attended upon his ministry, and listened to his sermons with great delight. Indeed, previous to the year 1825, he was considered by the best judges the best preacher in that county. His opinions were respected, his advice followed, and yet he never betrayed the least symptom of arrogance or self-conceit. When in the presence of white people, he seldom introduced conversation, and when he did, it was invariably done by modestly asking some very pertinent question on some very important subject. He was perpetually employed either in seeking or communicating information, and when no opportunity

Page 55

presented itself of doing either, he was habitually silent.

His dwelling was a rude log cabin; his apparel of the plainest and even coarsest materials, and yet no one ever heard him utter one "murmuring word." Like the shepherd of Salisbury Plain, his gratitude for what he had, precluded all anxiety for what he had not.

The tones of his voice, the expression of his countenance, together with every word, and every action, proclaimed that, in true lowliness of mind, he esteemed others better than himself.

An illustration of his meekness and humility is furnished by the fact, that when asked his opinion respecting the law, then recently enacted by the State Legislature, prohibiting coloured men from preaching, he very promptly expressed his approbation of the law; adding, "It is altogether wrong for such as

Page 56

have not been taught themselves, to undertake to teach others. As to my preaching, I have long thought it was no better than the ringing of an old cowbell, and ought to be stopped." He accordingly bowed to the authority of this law; and although often told, that the penalty for its violation would not be inflicted on him, he never preached afterwards; but became a constant and devout worshipper in a neighbouring Presbyterian congregation, which had been recently organized, and over which the first pastor of that denomination ever settled in the county of Nottoway, had been recently installed.

Another incident, illustrating his humble and contented disposition, must not be omitted Previous to the cessation of his public ministry, a pious and wealthy lady, feeling grieved to see him so rudely clad, presented him with a well made suit of black cloth. This

Page 57

suit, he wore but once, and then returned it to his kind friend, begging that she would not be displeased at his doing so, and justified his conduct thus: "These clothes are a great deal better than are generally worn by people of my colour. And besides, if I wear them, I find I shall be obliged to think about them even at meeting."

We have already spoken of the polite attentions he received at the hands of white people. In truth, Uncle Jack was always a welcome guest. In warm weather, he always insisted on sitting in the portico, or on the steps leading into the house, as a place better suited to his rank and character, than the parlour. Whenever he took this humble position, the whole family would soon gather around him, and hang upon his words, as long as he could be induced to remain. We have known the whole of a large and fashionable dining party,

Page 58

leave the gay attractions of the parlour, and repair to the porch, or to the shade of some venerable tree, under which he had taken his position, each saying as they went, "Uncle Jack has come, let's go and hear him." On such occasions, he displayed great prudence and wisdom in the topics introduced. He seemed fully to realize the importance of not repelling or disgusting the young and irreligious, by pressing religious truth upon their consideration, any further than they were disposed to give him their serious attention. The skill with which he could "rightly divide the word of truth, and give to each his portion in due season," might well rebuke some far better educated, and more distinguished ministers than he.

He never seemed to suppose for a moment, that the attentions shown him, were the result of any personal merit of his own. He considered them all as

Page 59

flowing directly from a regard to his Master, and his Master's cause. Nor was he led by such attentions to consider himself above those of his own colour. Most meekly and humbly did he "condescend to men of low estate." Most tenderly did he love, fervently did he pray, and faithfully did he labour, for his "brethren, his kinsmen according to the flesh." He sought their society, and mingled with them in their cabins, with the utmost familiarity. The respect shown him by the whites, united with the vast superiority of his intellectual and moral attainments over theirs, rendered him the object of suspicion and jealousy with the more ignorant, and vicious of this class. He was, moreover, a rigid disciplinarian. He was the relentless enemy of all pretended sanctity. Every departure from what he deemed an orthodox creed, or a consistently pious life, was sure to

Page 60

meet with his most decided opposition. Hence, all feared, and some really hated him. He was no stranger to persecution for righteousness' sake.

A gentleman of our acquaintance detected one of his servants, who belonged to Uncle Jack's pastoral charge, in some petty theft. The master merely admonished the offender, and dismissed him, saying, "I shall content myself with laying this matter before your preacher." He retired, but soon returned, and with the deepest concern depicted in his countenance, said, "Master, I have come back to say to you, that if you think I deserve punishment for what I have done, I would much rather you would punish me at once, as you think I deserve, than to tell Uncle Jack about it." The gentleman very wisely concluded not to comply With this strange request, and the servant was commended to the moral discipline

Page 61

of the good old pastor, which resulted very favourably.

It is somewhat remarkable, that just about the time that Alexander Campbell, of Bethany, commenced the propagation of his peculiar sentiments, which so seriously disturbed and divided the Baptist churches in the west, a coloured preacher whose name was Campbell, entered upon the work of "reformation" among the Baptists of his own colour in south-eastern Virginia. This man, however, struck out a course of his own--in some respects the reverse of the system adopted by his more learned namesake, but possessing equal, if not superior claims to originality. It will be quite sufficient for our present purpose, to mention two articles in the new creed of this sable reformer. One of these may be expressed thus: Inasmuch as very few of the blacks are able read, they should no longer rely

Page 62

upon, or be directed in their faith or practice by, the written word of God, but depend entirely upon the teachings of the Holy Spirit. The other was, that the old Jewish law, forbidding the use of swine's flesh, was still in force, and hence it was a great sin to eat pork or bacon.

Our Mr. Campbell could read, but, he said, God had shown to him in a dream the great impropriety of his doing so, as so many of his people were deprived of this privilege. He accordingly called a number of his congregation together, told them his dream, and gave them the interpretation thereof--said it was very wrong for the preacher to be above the people, and then, with great affected solemnity, threw his Bible into the fire and burned it to ashes. The success of this fanatic was considerable; so much so, as to awaken no little alarm among the owners of slaves in that section

Page 63

of the country. As soon as tidings of these things reached our old African, true to his principles, and faithful to the cause of truth and righteousness, he determined to make an effort to check the evil. Accordingly, he set out on a visit to the "reformer," and on reaching the neighbourhood in which he lived, called on several gentlemen whose servants had become his "disciples"--stated the object of his visit, and desired that a meeting might be held for the purpose of checking, if possible, these new and strange doctrines. His approach was hailed by these gentlemen, as if he bad been a second Luther, come to withstand another Tetzel. The meeting was held.

Mr. Campbell commenced, with all the self-importance so common to self-constituted, and self-styled reformers--pouring forth torrents of "great swelling words of vanity." The people

Page 64

sympathized with their leader, and joined warmly in the clamour. The African Preacher maintained the utmost silence for a considerable time, but at length arose with great solemnity and said, "My Bible teaches me, in all my ways to acknowledge God, and never to lean to my own understanding. Hence, I can go no further in this business until we have prayed for God's guidance and blessing." This proposition was evidently unexpected, and to many very unacceptable. But the dignified and solemn manner in which it was made, awed them into momentary silence, and kneeling, he prayed with strong faith and deep feeling, that God would be pleased to direct and bless them in their efforts to learn and do his will. The impression made by this prayer was eminently salutary. Finding that the people had become silent and more respectful, our good preacher proposed to

Page 65

this "setter forth of strange" doctrines, to state and prove his creed. He commenced with an attempt to sustain his positions by quotations from the Bible. To this, Uncle Jack objected, on the ground, that he had burned his Bible, and accordingly had no right to the use of any thing it contained. This was extremely embarrassing. But the prohibition was very properly enforced with the utmost firmness. An appeal to the audience as to the propriety of this course, met with so much favour, that Campbell, finding the current beginning to turn against him, became very angry, and resorted to personal abuse of the good old African. Upon this, the latter arose and with a good deal of biting sarcasm--a weapon he knew quite well when and how to use, said to the people My friends, you all see that what this man says about doing without the Bible, and depending on

Page 66

the Spirit, cannot be true; for he was not able to talk at all, when I told him he had no right to quote a book he had burned. And you can all see, by his getting so angry, that if any spirit came to his help, it was not the Holy Spirit. And as to that notion of his about the sin of eating hog-meat, if the half of what I hear about him and a great many of his members be true, the white people ought to do all they call to encourage that belief, as it will make the raising of hogs down this way, much easier and more certain than it is now." With this he took his leave., and with this, coloured Campbellism died entirely.

The life of the African Preacher was one of no little toil and suffering. Perhaps the most imprudent step he ever took, was marrying a woman who was in no respect "a help meet for him." Without mental culture, without religion, encumbered with a large family

Page 67

of children, the fruits of a former marriage, and surrounded by an extensive circle of other relatives, she only served to burden him with domestic cares, sufficient to have crushed the spirit of any ordinary man. These people were idle and profligate; he, industrious and economical. They hung, around and imposed upon him in the most shameful manner. Often would they filch from him the products of his own daily labour, and then add insult to injury, by the grossest personal unkindness, and even cruelty. But all this only served to give additional brightness and purity to his piety. Some metals become the more brilliant on being rubbed, and some flowers are all the more fragrant when trodden upon. So with pure and undefiled religion, and so it was with this good old African Preacher.

His thoughts, his affections, his aims, were all lifted so far above the din of

Page 68

domestic strife, that it seldom or never disturbed his equanimity even for a moment. The dreariness of his home on earth only served to make him sigh more deeply for "that house not made with hands, eternal in the heavens." He rarely alluded to these things, and whenever he did, he never failed to say all he could in extenuation of the guilt of those who had injured him. To the writer, he never alluded to these trials but once, and then he said, "I am such a hard-headed, disobedient child, that I need a whipping every day." At another time, referring to his poverty, and also to the fact that he had no descendants, he said, "I left nothing in Africa, and I brought nothing to this country. When I die, I shall leave nothing behind me, and shall carry nothing with me, but the merits of my Saviour's obedience and death."

The simplicity of faith, and the self-application

Page 69

with which our good preacher was accustomed to attend upon the ministrations of the sanctuary, were truly remarkable. "A day in thy courts is better than a thousand," was not only the language of his lips, but of his heart and of his life. When more than ninety years of age, we have known him to walk two, and sometimes four miles to reach the house of God. And this he would sometimes do in very inclement weather. Nor was he a forgetful hearer, but a doer of the word. We have often been surprised at the accuracy with which he could give the outlines of a sermon many days, and even weeks, after he had heard it. Under faithful and pungent exhibitions of the truth, he was often very deeply affected. After hearing a very lucid and impressive sermon on the resurrection of the dead, we found him, when the service had ended, in the rear of the church,

Page 70

leaning against the side of the house, bathed in tears. On asking him why he wept, he replied, "I am afraid, sir, that after all, I shall never realize what that young preacher talked about today. The glories of the resurrection unto life are too high for me." He was reminded of what the preacher had said about the changes which annually occur in nature, as to some extent illustrative of the resurrection. He was told to recollect the astonishing difference in the appearance of the trees in winter and spring; and was then asked, if the God who caused this difference, who, in the spring thus adorned the forest, could not, with perfect ease, beautify and adorn his body in an infinitely higher degree. To this he said, "I do not doubt the power or the love of God; but that which troubles me is this. If the tree has not a good root, God will never make it bloom. And so it is with

Page 71

me. If I have not the root of the matter in me, I shall never know any thing of the resurrection unto life."

On another occasion, we found him in no little distress of mind; and on asking the cause, were answered substantially as follows: "About a week ago, I heard a sermon on the text, "Turn ye, turn ye, for why will ye die?" The preacher, who came from the school up here in Prince Edward, took more pains than common to tell us what was meant by turning. He made the gate appear so strait, and the way so narrow, that he soon made me fear I had never turned at all. He certainly convinced me that I had still a great deal of turning to do, and that this turning must be the great business of the Christian's whole life." This was a very favourite thought with him. In strict conformity with his views on this

Page 72

subject, he preferred the term converting to converted.

In the course of a sermon on regeneration, he once introduced the following illustration to enforce the duty of growing in grace: "If a farmer," said he, "in clearing and preparing a piece of ground for cultivation, should do no more than to cut down the trees, and remove the bodies and branches of those trees, whilst all the stumps were left undisturbed, he would very soon find that around every one of those stumps, a considerable number of sprouts, of the very nature of the old tree, had put up, and he would have even more clearing to do than he had at first. Now, to get his land in a proper condition, he must not only cut down the trees, but he must grub up the stumps. Yes, he must continue to grub as long as any part of the root is left. Just so

Page 73

with sin in man's heart and life. He must not only forsake open sin, he must look to the heart, where the roots of this open sin are, and these roots must be grubbed up. And this grubbing he must keep at, as long as life lasts, or he will never bring forth the peaceable fruits of righteousness to the praise of God's free grace."

Our good preacher was much opposed to the hasty admission of members into the Church. He was accustomed to say, "It is much easier and safer, to keep unworthy persons out of the Church, than to get them out, after they have been once received." And again he would say, "The Church will not suffer half as much, by keeping a dozen worthy members out, a little too long, as she will by admitting one individual too soon. If you adopt this method of admitting members you must see to it, that your back door is as wide as the

Page 74

front. You must prepare for dropping them, as readily as you took them up."

It should be remembered, that these views were entertained and expressed, by a native of Africa, at different periods, between the years 1828 and 1836. Every one, at all acquainted with the history of the Presbyterian Church during those eight years, will be struck with the difference between the sentiments of this sable son of a Pagan continent, and some who stood high, as learned doctors of divinity, and even professors in Theological Seminaries, in these enlightened ends of the earth. And we presume there are few or none now in our communion, who would hesitate to say, that the Church would have fared much better, had she asked counsel of the African Preacher, instead of following the advice of some of her "most enlightened and pious divines." Had this been done, our motto would

Page 75

have been, a pure church, or no church. It is true, the course recommended by the African, would not have emblazoned our church registers with so long and imposing an array of names; but the purity, and by consequence the moral power of the Church, would have been far greater. The efficiency of an army depends upon the patriotism, the courage, and the activity of each soldier, more than it does upon the gorgeous uniform, the graceful movements, or even the imposing numbers of those who fill its ranks. So every one destitute of the essential qualities of "the good soldier of Jesus Christ," hinders the progress, and detracts from the efficiency, of "the sacramental host of God's elect." Such views as these led the good African Preacher to make the Saviour's rule his, and they should lead us to make it ours. It is the only reliable rule: "By their fruits ye shall

Page 76

know them." And the application of this rule in any given case, requires more than a day, a week, or a month.

The next thing deserving of consideration in the character of this excellent old man, was his method of dealing with persons awakened to a sense of their sinfulness in the sight of God. He was very often consulted by persons in this state of mind, of every grade in society; as also by those who, having hope in Christ, were asking what step they should take next, to honour Christ and do good. Here, as in other matters, his course was characterized by good sense and discretion.

On one occasion, a lady of great respectability told him that she considered herself a Christian, but at the same time avowed the purpose of not making a profession of religion by connecting herself with the Church. At this he expressed great surprise--

Page 77

reminded her of what our Saviour said of those who "confessed," and of those who "denied" him, and then added, "Mistress, if you should suddenly come in possession of a large sum of money, would you lock it up in your house, and try to keep it a great secret? It would neither do you nor any body else much good, to take that course with it."

At another time, one gave him a long account of a remarkable dream she had had, and desired his opinion on the subject. To this he replied, "The Scriptures do tell us something about dreams, but no where that I remember, of any one converted by a dream or converted when he was asleep. I can understand people a great deal better when they tell me of what they say and do when they are awake, and when they talk about a work of grace in their hearts."

Page 78

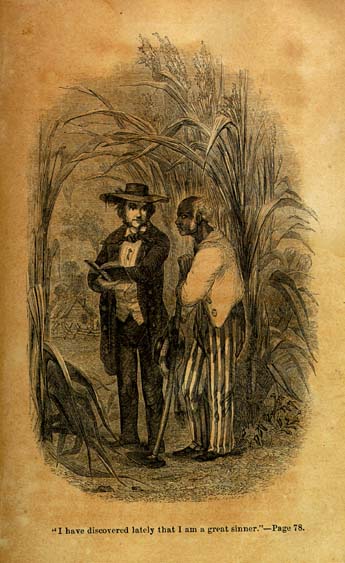

There lived in his immediate vicinity, a very respectable man who had become interested on the subject of religion, and who, with some earnestness, had begun to "search the Scriptures." He had been thus employed but a short time when he became greatly perplexed with some of those passages which even an inspired apostle has said, are "hard to be understood." In this state of mind he repaired to our preacher for instruction, and found him at noon, on a sultry day in summer, occupied in his field, hoeing corn. As the man approached, the preacher saluted him with his accustomed politeness; and then with patriarchal simplicity, leaning upon the handle of his hoe, listened to his story. "Uncle Jack," said he, "I have discovered lately that I am a great sinner, and I have commenced reading the Bible that I may learn

"I have discovered lately that I am a great sinner."--Page 78.

Page 79

what I must do to be saved. But I have met with a passage here," holding up his Bible, "which I cannot understand, and which greatly perplexes me. It is this, 'God, will have mercy on whom he will have mercy, and whom he will he hardeneth;' what does this mean?" A short pause intervened, and the old African answered as follows: "Master, if I have been rightly informed, it has only been a short time since you commenced reading the Bible, and I think the passage you have just read is in the Epistle to the Romans. Long before you get to that, at the very beginning of the gospel it is said, 'Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.' Now, have you done with that? The truth is, you read entirely too fast. You must begin again, and learn the lesson as God has been pleased to give it to you. When you have done what you are told to do in Matthew, come to

Page 80

see me, and we will talk about that passage in Romans." Having thus answered, he resumed his work, and left the visitor to his own reflections.

Who does not admire the simplicity and good sense displayed in thus dealing with a person of this description ? Could the most learned polemic more effectually have met and disposed of such a difficulty? The gentleman particularly interested in this incident gave the foregoing account of it to the writer, and, if he still lives, will joyfully say now, as he did when he first spoke of it, "It convinced me fully of the mistake into which I had fallen. I took the old man's advice, soon saw its propriety and wisdom, and hope to bless God for ever for sending me to him." The consequence was, that he soon became an intelligent, consistent Christian, connected himself with the Church, and contributed in no small degree to

Page 81

the promotion of a cause he had once hated and opposed.

Our preacher was not only skilful in imparting instruction, but patient and submissive in the endurance of evil. We have already seen with what meekness he bore the domestic trials which befell him. He sometimes suffered abroad as well as at home. But his Christian submission was every where and at all times conspicuous. When reviled, he reviled not again. He rejoiced in being counted worthy to suffer shame for the name of Christ. We know of but one instance in which he was threatened with personal violence. A party of such as the Apostle Paul denominates "lewd fellows of the baser sort," on one occasion interrupted him while preaching, and took him into custody. After reviling him a good deal, they avowed the horrid purpose of punishing, him with stripes, and asked him,

Page 82

tauntingly, what he had to say in his own defence. "I wish to know," said the good old man, "why you intend to punish me. If it is for preaching the gospel, I have not a word to say." "Why," asked one of the party, "you are not willing to be whipped, are you?" "Perfectly willing," was the emphatic answer, "perfectly willing ; and I will tell you why I am. I can read the Bible a little; and in reading it, hardly any thing surprises and grieves me more than to find that such a man as the Apostle Paul, 'five times received forty stripes save one,' for preaching this same gospel. Now, when I remember this, and then remember that an old sinner, such as I am, should have been preaching, or trying to preach this gospel for more than forty years, and never yet had one lick for it, I am perfectly willing to be whipped."

This reply wholly disarmed his

Page 83

adversaries. They were literally silenced. With a moral courage which was fully equal to his humility, he resolved to improve the advantage he had thus gained. The whole of his audience, frightened by the brutal assault of these wicked men, "forsook him and fled." He stood alone, in the midst of his enemies, with no eye to pity, and no hand to help. But He who said, "I will never leave thee nor forsake thee," fulfilled his gracious promise. Thus sustained, thus cheered, he addressed his persecutors in language so pungent, and yet so tender, that one by one, they walked quietly away, leaving him in the undisturbed possession of the ground. The leader of this party, who gave us this story, and who subsequently became a pious man, was often heard to say, "the impression made on my mind and heart by that incident, was never effaced."

Knowing that the African Preacher

Page 84

was now very old, and evidently near the end of his earthly pilgrimage and our personal intercourse with him having for several years ceased, we addressed a letter, early in the winter of 1838, to our best earthly friend and his, Dr. James Jones, asking for information of his state, now that the shadows were lengthening, and his end supposed to be near. To this letter, the good Doctor promptly sent us the following reply:

"MOUNTAIN HALL, Nottoway, Dec. 31,1838.

"My Dear Sir--There are very few persons either among the living or the dead, with whom I have had so long personal intercourse, as with Uncle Jack. I found him among my nearest neighbours, when I first settled at my present residence. His deportment, under all circumstances, has never varied; always modest, unassuming and humble. His serene and placid countenance is seldom without a smile, if engaged in

Page 85

conversation, or great gravity, if disengaged. Ever prone to enter into conversation, where he thinks it not disagreeable, he scarcely ever fails to make religion the topic before it ends. He visits my family with the utmost freedom, on all sorts of business and occasions which are legitimate, and I think I cannot be mistaken in the assertion just made. His visits are now, perhaps, more frequent than ever; and seem to be made almost exclusively for the purpose of getting information on some text or parable or narrative in the Bible. When this is his object, he announces it immediately on his arrival, asks to have it read from the Bible, and frequently inquires what our commentators say on the subject.

"It is proper here to state, that while his memory is greatly impaired on all matters of secular concern, it is retentive and ready on every thing relating

Page 86

to the Scriptures, in connection with his own experience of the influence of divine truth. On propounding his questions for information, he invariably quotes, most accurately, the chapter and verse; not unfrequently, the words themselves. Very frequently he will refer to the occasion on which he first heard it read or spoken of; perhaps thirty or forty years ago, in some sermon or private conversation.

"Both his physical and mental powers are evidently on the wane. He exhibits no little debility by his unsteady gait, his head inclining forwards, so that his chin almost rests upon his breast; and he complains much of rheumatism. Still, he manifests great reluctance to confinement, so long as he can use the organs of motion. He gives his personal attention to every branch of business on his little establishment, and is, at this time,

Page 87

in a most comfortable situation, as respects his supplies of the necessaries of life. I perceive no alteration at all in the temper and disposition of his mind The same equanimity which has so long distinguished him, still prevails; and so remarkable has his character been, in this respect, that I have never yet seen an individual who has known him to be put out of temper, or to show any thing like petulance, or irritation, or resentment, on any occasion whatever, throughout his whole life.

"Weak and feeble as he is at this time, he seems to have been most highly excited, both in mind and body, by the revival of religion which has been for some time past in progress in the churches around him. He is unable to attend distant meetings, but frequently walks to those near at hand. He takes special care, however, to get to very many of the families in which

Page 88

conversions have been reported, let them be far or near. I am often surprised to hear from him an account of what passed between him and certain families, in recent conversations. Upon inquiry, I find he has walked all the way expressly to see them. He would say, 'I could not resist. I was obliged to try and get to them, that I might tell them all I knew to help them on their way.'

"I can only add the assurance of the undiminished esteem and affection of

Yours truly,

JAMES JONES."