THE DURKET SPERRET:

Electronic Edition.

Sarah Barnwell Elliott, 1848-1928

Text scanned (OCR) by Lee Ann Morawski

Images scanned by Lee Ann Morawski

Text encoded by Jill Kuhn

First edition, 1999

ca. 450K

Academic Affairs Library, UNC-CH

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

1999.

Call number PZ 3 .E468D

(Tennessee State Library)

The electronic edition is a part of the UNC-CH digitization project, Documenting the American South.

Any hyphens occurring

in line breaks have been

removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to

the preceding line.

All quotation marks and ampersand have been transcribed as

entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and "

respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and

' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Spell-check and verification made against printed text using

Author/Editor (SoftQuad) and Microsoft Word spell check programs.

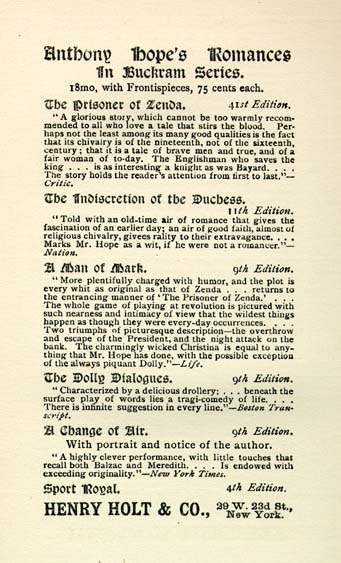

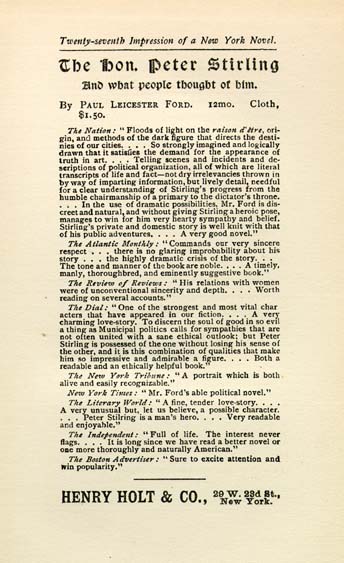

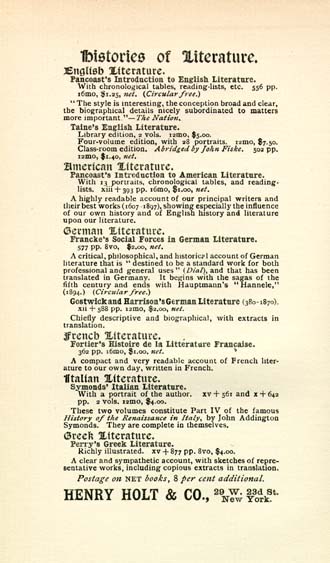

Advertisements that precede and follow the main text have been included as images.

Library of Congress Subject Headings, 21st edition, 1998

- LC Subject Headings:

- Cumberland Mountains -- Social life and customs -- 19th century -- Fiction.

- Cumberland Mountains -- Social conditions -- 19th century -- Fiction.

- Southern States -- Social life and customs -- 19th century -- Fiction.

- Southern States -- Social conditions -- 19th century -- Fiction.

- Mountain whites (Southern States) -- Cumberland Mountains -- Fiction.

- Mountain life -- Cumberland Mountains -- Fiction.

- Women -- Cumberland Mountains -- Fiction.

- Dialect literature, American -- Cumberland Mountains.

- Dialect literature, American -- Southern States.

- 1999-04-21,

- revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

Celine Noel and Sam McRae

-

1999-03-29,

- finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

Jill Kuhn, project manager,

- 1999-03-23,

- finished scanning (OCR) and proofing.

Lee Ann Morawski

THE DURKET SPERRET

A NOVEL

BY

SARAH BARNWELL ELLIOTT

AUTHOR OF "JERRY," "JOHN PAGET," AND "THE FELMERES"

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

1898

Page verso

COPYRIGHT, 1898.

BY

HENRY HOLT & CO.

THE MERSHON COMPANY PRESS,

RAHWAY, N. J.

DEDICATED

TO

MY BROTHER

John Gibbes Barnwell Elliott, M. D.

OF

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA.

Page 1

"THE DURKET SPERRET.'

I

"But when I saw that woman's face,

Its calm simplicity of grace--"

It had been a wild morning up among the Cumberlands. A March morning full of rain, of clouds that veiled the mountains, and of wind that tore the clouds to shreds. But at the turn of the day the wind had fallen: the great masses of trees that purpled the mountain-side from base to apex had ceased their tossing, and stood in dark monotony, save when a gray cliff thrust itself out, or a wild, snow-swollen stream dashed its spray toward the sky as it flung itself down into the valley.

The shadows are gathering early over a little valley known as "Lost Cove." On all sides the mountains rise about it in soft, sweeping curves, until they stand out against the sky a level, unbroken line. There is little of rugged wildness in these old mountains, for no stormy outburst

Page 2

marked their birth. They stand the perfect work of the ages. Their gray old faces looked out across the slow silurian sea, whose wandering waves began the patient work of denudation.

No rugged wildness, but a silent grandeur of repose smoothes every curve of every spur that stretches out across the plain, and a great unspoken dignity lives in the straight sky line that marks the summit.

On three sides the mountains guard Lost Cove, on the fourth the barrier that shuts this basin from the world is lowered. But though lowered, the little stream that through all the years had hollowed out Lost Cove, found here an obstacle that its patient zeal could not remove. It could not rise above it--it could not wear it through, and so it sank, and, burrowing deep among the "hidden bases of the hills," found victory and freedom. From out the black-browed cave it flashed again into the glad sunlight, with a mocking laugh for the barring cliffs that rose two hundred feet above it, to face the eastern sun.

Near the upper end of the Cove, which is nearly a mile long, there stands a house built of squared logs, carefully mortised at the corners, and neatly "chinked" with plaster. Seventy

Page 3

years ago it was built by the first Warren, as a defense as well as a shelter. Three rooms, a lobby, a loft, and two piazzas make the extent of it. A room on either side the lobby that connects the front and back piazzas, and from which a rough stairway leads up to the loft. The third room is made by boarding in the end of the back piazza, and through its single window a modern cooking stove pushes its pipe. The floors look worn with scrubbing, the small, deep-set windows shine like eyes, and the great stone chimneys that grace either end of the house, look as if built for eternity. Around the house there is a rough picket fence; within this inclosure there are some cedar trees, some common rose bushes, some chickens, and some much-scratched grass. Beyond, and rising and falling with the swells of the mountains, is a rail fence which shuts in from the public road the lot where the hogs, and cows, and horses are kept, and where stand the few out-buildings. From the lower end of this outer lot the fields stretch down the Cove to where the stream sinks, and a stately beech grove crowns the rising ground. The public road from across the mountains turns at Mr. Warren's gate, and zigzags along these fields to the beech wood, then it marches over the divide to the far-off valley.

Page 4

A young woman leaned over the outer gate. The rain had ceased, and the wind came softly with a touch of spring. It would be clear on the morrow, the girl thought as she looked up from the shadows of the Cove to where the cloud-broken sunlight flashed and faded on the mountain tops. A clear spring day, and, as the warm wind swept by, her fair cheeks flushed with gladness for the coming spring.

The winter had been hard, and for the first time the Warrens had felt themselves poor. This girl's father had been killed a few months before, and she and her grandparents had had to fight through the cold weather alone. And now, as she waited for the cows, the touch of warmth in the wind brought to her mind a new problem--the planting. Some help would have to be hired, and where was the money? They had bacon, and apples, and potatoes that could be sold--if she could take them to the town on top the mountain. The color flamed into her face; she had never "peddled" in her life! Her grandfather was held fast by rheumatism, and her grandmother would far rather starve than go on such an errand.

Presently a cow-bell clanked, and down the mountain-side, in dignified procession, came the rough, long-legged, patient-eyed cows. The

Page 5

girl roused herself with a sigh, and, holding the big gate open, remembered one more article that could be sold--butter.

She fetched two wooden piggins, white with scouring, and some fodder, then brought the cows in, one at a time, to the inner lot. She moved with the deliberation of age, and milked with patient sedateness. This quietness was a class habit, but increased in this girl's case through her having lived always with old people; and now the heavy responsibilities that crowded upon her seemed to have banished all youthfulness.

The Warrens had always been well-to-do, making at home almost everything they needed. After his sons left him the old man had been quite able to carry on the place, and before his strength failed his eldest son had returned with his motherless baby, Hannah. So there had been little need for money until now, when, her father dead and her grandfather disabled, Hannah needed to hire help. She might have paid in kind, but everybody that she knew made all they needed. The only people she had ever heard of who bought everything and saved nothing, were these new people on the mountain, who were held throughout the country to be strangely "lackin'." Old Mrs. Warren

Page 6

pronouncing them "darn fools, a-settin' round with books in their hands."

The milking done, Hannah took the pails into the kitchen. With the same lack of haste she stirred the fire under the kettle, opened the oven to look at the corn bread, strained the milk, then taking up an axe went into the back yard. Her face grew graver as she looked at the wood pile; she would have to go for more to-morrow, and she sighed as she pulled a log into position for cutting.

There was an outlet from all this. She could marry her cousin Si Durket. She would rather cut wood all day! And the axe swung into the air with an ease and swiftness scarcely to be looked for from a woman.

No good would ever come to Si. She rested on the axe as she turned the log with her foot. Peddling would be better than Si; hiring out-- starving--anything would be better. Yet, if something were not done very soon, she would have to marry him, or let the old people want. Mrs. Wilson, from the far side of the Cove, went up to the mountain to peddle--she could go with her. Mrs. Wilson was a creature much scorned by Mrs. Warren, still she knew the ways at the University, and could direct a beginner. It was

Page 7

worth thinking of. Gathering up the wood, she went into the house to her grandmother's room.

It was low, and the walls, finished up to the rafters with wood, were painted gray, spattered with white. A pine bedstead, with tall posts, and piled into a dumpling with feather beds, filled one corner. In another corner there stood a high chest of drawers, above which hung a spotted looking glass and some peacock feathers. A spinning-wheel, a small table full of dusty odds and ends, a large rocking-chair, covered with a patchwork quilt, and a few splint-bottomed chairs, finished the furnishing of the room. In the rocking-chair, close to the great fireplace, sat an old man, and an old woman stood near a window catching the last light on her work.

She had been a handsome woman once, and, like Hannah, was tall; but here the likeness ended. Mrs. Warren's face was sharp and hard, the girl's face was grave and strong; Mrs. Warren's eyes were keen, while Hannah's eyes were thoughtful, almost sad. Further, Mrs. Warren's temper and tongue were famous, while Hannah seemed still and gentle. Perhaps time was needed to reveal Hannah; perhaps the temper of her grandmother had made her esteem

Page 8

peace as the greatest good. Each son had had to take his wife away, and Hannah's father had only come back after his wife's death, when, seeing that his father needed him, he stayed. A gentle, patient man, he could put up with the temper his mother, whose maiden name had been Durket, was proud to call the "Durket sperret." With regard to his child, he knew that no real harm would come to any creature absolutely dependent on his mother. "Her own" meant a great deal to Mrs. Warren. Her sons' wives she had looked on as aliens. The kitchen stove, introduced by one of these unworthies, had caused the final breaking up of the family. The young woman had declared the open fireplace to be old-fashioned, and her husband bought the stove. The "Durket sperret" could not stand this, and the young people had to go, but not the stove; Mrs. Warren kept that, and for the future vented much of her superfluous wrath on it.

As Hannah entered, Mrs. Warren turned sharply:

"I wonder you don't git tired a-playin' nigger, Hannah Warren," was her greeting. The girl put down and arranged the wood before she answered:

"Thar is wuss things," then stood looking down into the fire. Straight as a young poplar,

Page 9

with the grace and roundness of perfect strength and youth in every curve, Hannah, in her scant black frock, was dowered with a beauty rare in any class. A grave, clear-cut face, waving brown hair taken straight back and twisted in a knot, a full throat that showed exquisitely white where the little faded shawl fell away from it, and hands that, if hard and brown, were very shapely.

Her grandmother looked at her intently as she stood there, and grumbled a little under her breath.

"Ain't you none better, Gramper?" Hannah asked pityingly of the old man, bent nearly double in his chair.

"I'm some easier," he answered patiently, "but I'm tore up a-steddyin' 'bout the crap."

"The crap wouldn't count if Hannah had a shavin' o' sense," the old woman struck in sharply.

"Supper's ready, Granny," Hannah said, and left the room.

"You pesters Hannah moren human, Mertildy," the old man suggested mildly; "an' she's a good gal."

"I reckon I knows my own flesh an' blood, John Warren," his wife retorted; " an' but for you, I'd larn her some sense, or know why. Si Durket's my own brether's son, an' as good as

Page 10

Hannah Warren will ever git. He's got a plenty, an' is free-handed an' hearty, an' he'll do to look at too. He's a Durket through an' through."

"All the same, Mertildy, Hannah don't favor Si."

"Don't favor Si! You makes me weak, John Warren! Do a steer favor a yoke? but thet's all a steer or a yoke is made fur. Gals is the same; an' all yokes is jest alike as fur as I kin see."

Mr. Warren shook his head, "You've missed the furrer, Mertildy," he said; " 'tain't the yoke, hit's the tother steer thet's the trouble. The yoke is fur all, one way or anether, an' we gits our necks sorely galded, thet's true; but hit's the tother steer thet mostly gits us, an' Hannah shan't be yoked ginst her will. You worn't, Mertildy."

"I reckon the difference would abeen wore out by now, anyhow," Mrs. Warren answered ungraciously, "an' I'd abeen jest as well pleased"; and she left the room.

For more than a year Si Durket had been courting his cousin Hannah. Hannah's father and grandfather had supported her in saving no, agreeing that a man who could strike his mother and curse his old father, was not to be desired;

Page 11

but Mrs. Warren championed Si vigorously. That a woman lived who could refuse a Durket, she would not believe. A Durket who would be rich when his father died, for there was much land and only two brothers to divide it; further, a Durket who had been to school. Mrs. Warren had a great contempt for education, nevertheless she urged Si's "larnin" as a point in his favor.

Another potent cause for Mrs. Warren's earnestness was that the wife of Si's brother Dave, a young woman from a town, had openly laughed at Si's choice of Hannah, a country girl who had never been out of Lost Cove a half dozen times in her life, and who was poor compared with some girls Si might have won.

These considerations did not sway Si, but he was keen enough to repeat this speech to his Aunt Warren, who in her rage declared that Hannah should marry Si, if only "to down thet sassy hussy, Minervy!" And Si, seeing how work and poverty were pressing the girl, felt his hopes rise.

Mr. Warren was troubled for Hannah in the present crisis, still he felt that any work was better than marrying a man she despised. Hard work made rest sweet, he thought, as he sat by the fire weary and disabled; made any food seem

Page 12

good, and left a peaceful satisfaction when the day was done, when one could smoke one's pipe and think of the long dark furrows, and the well-stacked wood-pile, and the cattle penned from harm, and think that, when the winter came, there would be a plenty and to spare. Ay, work was a good friend. But now his son was gone, and he could do nothing. It was hard on the girl.

"He knocked hisn's mammy--he's hard." The musing ended aloud, and Hannah, coming in with his supper, heard him.

"I'll never tuck him," she said, in her soft slow voice, as she put the cup and plate on a chair near the old man. "Si kin cuss, an' Granny kin blate, I'll tuck hit, but I'll never tuck Si." She kneeled on the hearth with her hands fallen together in front of her. "An' 'bout the crap, Gramper, I 'llows I kin git thet Dock Wilson what's come to the Cove to he'p me do the plowin', an' Granny kin drap, an' I kin kivver."

"Don't say nothin' to Granny 'bout drappin', chile," the old man said, with patient experience in his voice, "hit 'll jest gie her anether handle to grind on."

"Jest so," Hannah responded; "but, Gramper,

Page 13

if Dock's like hisn's stepmammy he'll strike fur high wages."

"Thet's true as true, an' thar ain't no money."

"Thar's things to sell," Hannah suggested; "I could tuck ole Bess, an' pack truck to the 'versity."

"Peddle!" the old man said, in a lowered tone; "a Warren woman peddle?"

"Hit ain't no sin."

"No, but no Warren woman ain't never peddled yit--never yit!"

"You said onest that I could go," the girl persisted; "an' hits peddlin', or hirin out, or marryin' Si, Gramper."

"That's true, gal; but I hates hit."

"No moren I do, Gramper." Then hearing a chair pushed back in the kitchen, she rose. "I'll hev to git wood to-morrow," she added, "but I'll go on Friday. Don't say nothin' to Granny."

Mr. Warren nodded, and Hannah, taking the cup and plate, reached the door just as her grandmother entered.

"The cawfee's 'bout out," she said, "an' the sugar's right low too."

"I knows hit, Granny."

"An' I can't git on 'thout cawfee an' sugar."

Page 14

"I knows thet, too, Granny," and Hannah closed the door.

"An' whar hit's to come from I dunno," Mrs. Warren continued as she filled her pipe.

"I reckon Jack Dunner'll trade her some fur meat," Mr. Warren answered. "Jack knows we's pushed, an' he's mighty 'commydatin'."

"Pushed! Thet is true, John Warren, if you did say hit, but if you hed any grit we'd not be pushed. You keeps on a-stirrin', an' a-stirrin' 'bout Hannah tell nuther one o' you is stiffern hog slops."

"An' if Hannah did tuck Si," Mr. Warren said patiently, "hit'd leave us 'thout no help, Mertildy, fur thet gal is all we hes."

Mrs. Warren laughed. "Thet's easy fixed," she answered; "goin' to Si's is jest a-goin' home to me an' you kin bet youuns hide I'd go."

"Then you'd leave me, Mertildy," and the old man straightened himself. "I couldn't rest under no shed but John Warren's, an' I won't, kase thar ain't no shed big enough for two famblies, nummine if thar's only one apiece in them famblies. Moren thet, thar ain't never been a Warren beholden to nobody fur a shelter yit, an' John Warren ain't gwine to start hit. If you goes, Mertildy, you'll leave ole John to his lone."

Page 15

Mrs. Warren smoked furiously, and, "You're sappy yit," was all the answer she vouchsafed.

Pondering his wife's words, the old man began to see the wisdom of Hannah's plan, while Hannah, at her work, was busy devising ways for the carrying out of this same plan. The coffee and sugar made a good excuse for her journey to this new mountain town, that was a market for all the country. She could arrange her load in an out-house, and leave before the old people were up. When she went for the wood she would stop at the Wilsons' and find out about the people and prices at Sewanee. She had been there as a sightseer, but never to peddle. There were worse things than peddling, however, and Si Durket was one.

Page 16

II

"Ofttimes like children we are led to meet

Our life--or driven like slaves by circumstance.

And suddenly it crowds us down to earth!

And in the thick we have no time to cry,

Only to fight! Then all is still. And through

The deadly calm of peace we moan--'Oh, fool!

Oh, fool! now all thy life is done--is done!'

Yet, still, like children we were led to it;

Or driven like slaves by lashing circumstance,

And knew not of the ambush waiting there."

At the time this story opens, the railway station, known as Sewanee, consisted of a few shops, the post-office, and one or two small houses, built about a barren square. From this a broad road led to the "University," and the other end of Sewanee. Up this road the butcher and shoemaker had planted some locust trees in front of their shops, and beyond them the confectioner had laid a stone pavement for the length of his lot, and planted some maple trees, that, in the autumn, burned like flames of fire. Beyond the confectioner's the road was in the woods for a short space, then more houses. About a half mile from the station this road

Page 17

ended in another road that crossed it at right angles, and up and down this the University town was built.

Between the houses, between the public buildings, wherever any space was left free from carpenters and stone masons, the forest marched up and claimed its own, while the houses looked as if they had been convinced of their obtrusiveness, and had crept as far back as possible, leaving their fences as protection to the forest, and not as the sign of a clearing.

Very still and bare the little place looked on the gray March morning, when, under Mrs. Wilson's guidance, Hannah made her entrance as a peddler. Down the road, beaten hard by the rain, and dotted here and there with clear little pools of water, Hannah led old Bess, bearing the long bags, in the ends of which were bestowed the apples and potatoes, the bucket of butter being fastened to the saddle.

They had not stopped at the station, for Mrs. Wilson said the people in the town paid better prices.

"They don't know no better than to tuck frostbit 'taters," she explained, "an' they'll give most anything fur butter jest now. All the 'versity boys is come back, an' butter's awful sca'ce. To tell the truth," pushing her long bonnet back,

Page 18

"thar ain't much o' anything to eat right now. What with layin' an' scratchin' through the winter fur a livin', the hens is wore out, an' chickens ain't in yit, an' these 'versity women is jest pestered to git sumpen fur the boys."

Hannah listened in silence. She had her own ideas about trading, and besides had very scant respect for Mrs. Wilson, either mentally or morally. She knew that her things were good, but she was determined to ask only a fair price for them. It was bad to cheat people because they were simple or "in a push." She was in a push herself, and felt sorry for them.

"An' ax a leetle moren you 'llows to git," Mrs. Wilson went on, "kase they'll allers tuck some off. Thar air a few that jest pays what you says, or don't tuck none, an' I axes them a fa'r price." They stopped at a gate as she finished, and she directed Hannah to "hitch the nag an' stiffen up."

"I ain't feared," Hannah answered, while she made old Bess fast, "but I ain't usen to peddlin', an' I don't like hit, nuther."

Mrs. Wilson laughed. "Youuns Granny keeps on a-settin' you up till nothin' ain't good enough," she said. "Lots o' folks as good as ary Warren hes been a peddlin' a many a year."

Page 19

"Thet don't make hit no better fur me, Lizer Wilson, an' nothin' ain't agoin' to make hit better; any moren a dog ever likes a hog-waller," and she took down the bucket of butter with a swing that brought her face to face with her companion. One glance at Hannah's eyes, that now looked like her grandmother's, and Mrs. Wilson changed the subject.

"Leave the sacks," she said roughly; "hit'll be time to pack 'em in when they're sold." She led the way in along a graveled walk, Hannah looking about her curiously, and trying to conquer her rather unreasonable anger against Mrs. Wilson, before she should meet the people about whom she had heard such varying reports.

At the front piazza Hannah paused, and Mrs. Wilson laughed exasperatingly.

"Lor, gal!" she said, "these fine folks don't ax folks like weuns in the front do'; weuns ain't nothin' but 'Covites come to peddle'; come to the kitchen."

That people lived who thought themselves better than the Warrens or Durkets was a new sensation to Hannah, and she wondered if her grandmother knew it. Her astonishment stilled her wrath until the thought overwhelmed her, that perhaps these people would look on her and Lizer Wilson as the same! She had followed

Page 20

mechanically, and before she had reached any conclusion they were at the back door.

A negro woman stood wiping a pan, while a lady, holding an open bucket of butter, was talking scoldingly to a woman who, as Hannah saw instantly, looked very different from the lady, and very much like Lizer and herself. There was a moment's silence as the newcomers appeared; then the negress spoke.

"Mornin', Mrs. Wilson," she said familiarly.

"Mornin', Mary," Mrs. Wilson answered, in an oily tone; then to the lady she said: "Mornin', Mrs. Skinner."

"Good-morning, Mrs. Wilson," the lady answered, while the woman she had been scolding turned, and Hannah recognized a person who lived near the Durkets, and who was looked down on by them just as Lizer Wilson was by the Warrens. They did not greet each other, but Hannah felt the woman's stare of wonder, that "John Warren's gal" should peddle with Lizer Wilson! She seemed to hear the story being told to the Durkets, and repeated to her grandmother by Si. Things seemed misty for a moment, then, through the confusion, she heard Lizer's voice. "No, I ain't got nothin' left but a few aigs; but this gal has a few things she'd like to get shed of 'fore we starts home."

Page 21

Hannah listened, wondering, and remembered a saying of her grandmother's, that Lizer could "lie the kick outern a mule."

"What has she?" questioned Mrs. Skinner.

"Taters, an' apples, an' butter," Lizer answered; "nothin' much to pack back if the price ain't a-comin'."

"What is the price of the butter?"

"Thirty cents; I've done sold mine at thet; the taters is a dollar an' a heff a bushel, an' the apples a dollar."

"I have just paid twenty cents for butter; why are your things so high?" was questioned sharply.

"Ourn is extry good," Lizer answered. The negro woman smiled. Hannah's indignation was gathering, but she did not speak. Mrs. Wilson must know the ways of the place--she would wait.

"I'll take the apples," the lady began compromisingly, "but I will not take the butter nor the potatoes. How many apples have you?" to Hannah.

"A bushel," Hannah answered quickly, afraid that Lizer would say a cartload.

Mrs. Skinner looked at her keenly. "I have never seen you before," she said.

"She ain't never peddled befo', an' ain't got

Page 22

no need to come now," Lizer struck in, looking straight at the woman from the other valley. "She jest come along fur comp'ny, an' brung a few things fur balance--she ain't pertickler 'bout sellin'."

The first part of this speech soothed Hannah's feelings somewhat, but the final clause, representing her as coming for the love of Lizer Wilson, was worse than the peddling.

She began to wonder if this woman could tell the truth.

"Run git youuns apples, Honey," were the next astonishing words; Lizer calling her "Honey!" She felt a sudden hatred for the woman. What had happened to her? was she really no better than Lizer? She drew a bitter sigh. Never mind, she would get a dollar for the apples instead of the "six-bits" she had thought to demand, and shouldering the apples she went back. They were carefully examined by the mistress, and generously measured by the servant.

"Hit's a good bushel," Hannah said, astonished that her bushel should be remeasured.

"Three water-buckets with a rise," the lady put in quietly, and the negress piled each bucket carefully. Mrs. Wilson laughed, then stooped to help her, and Hannah watched them with her

Page 23

share of the "Durket sperret" rising within her. A Warren cheat!

"With all youuns risin', Mary, some's left," and Lizer laughed again. Hannah looked down the cavernous bag, where about a dozen apples were huddled into one corner. The color burned in her face, and with a quick movement she emptied them on the floor.

"They wuz in my bushel," she said, "they misewell go in yourn."

The negress laughed. "I'll tek dese, Miss Josie," she said to the lady.

There were two spots of color on Mrs. Skinner's face as she paid Hannah. "I should like some more apples if you can spare them," she said.

Hannah paused, her anger fading before the hope of more money. If she could bring them the next day? But by Sunday the storm about peddling would reach her from the Durkets, and she had no security that she would be allowed to return. "Hit's a fur way to come an' only a dollar at the end," Lizer struck in, mistaking Hannah's hesitation, and Mrs. Skinner answered, "She can bring me two bushels for two dollars and a quarter."

"I can't bring 'em atter to-morrer," Hannah said slowly.

Page 24

"Very well, bring them to-morrow."

When they turned the corner of the house, Mrs. Wilson said:

"Thet wuz a good trade; you'd asold fur nothin'. Miss Harner thar, she hed put her butter at two bits, an' only got twenty cents. These folks beats a pusson down to nothin'."

"She riz on the apples," Hannah answered coldly.

"Riz on the apples," Lizer repeated derisively, while Hannah untied the horse; "she done thet kase you acted so biggity. My soul! but thet'll tickle Si Durket when Jane Harner tells hit."

" 'Pears to me like she done hit kase she lit on a honest pusson," Hannah retorted.

It was Mrs. Wilson's turn to be angry now, but as the Warrens were her rich neighbors, she only comforted herself with a promise to remember, and walked on without giving a hint as to their destination. At the next house she did not wait while Hannah tied the horse, but walked in rapidly, leaving her to come alone. Hannah was glad, for if there was danger of meeting acquaintances, she preferred not to be seen with Lizer. She walked in quite confidently, but when she reached the back door, Lizer had vanished.

Page 25

She paused a moment before several closed doors, some belonging to an out-house, and two to the main house. She knocked at one of the latter. She might be mistaken, but there was no harm in trying. Her knock was answered by a little boy, who asked her business, then called to someone within: "It's a woman with butter." There was an indistinguishable answer; then the child led the way to a small room, where Hannah saw so much china and glass that she wondered if they kept it for sale. She would have liked a longer look at it, and if she had known more she would have waited here, but the child had gone through another door, and she followed.

Once or twice she had heard descriptions of how the people lived in this town, that to the surrounding country was as yet an enigma. Stories of how they had no object in life but "book larnin'," and were little better than "Naytrals." Once her grandfather had said, "God made all the critters, book-larnin' critters, too, an' all hes a right to live." This was the only excuse she had ever heard made for them. But she forgot all she had ever heard when she passed through the second door. It was as strange as a dream. The various kinds of furniture she had never seen before, the covered

Page 26

floors that made no noise, the books, the curtains, the pictures, all were new to her, at least, in this reckless profusion.

"Come near the fire," a voice said, and Hannah caught a glimpse of a fire, but it seemed a long way off, and a young man in the middle distance was an almost impassable barrier. She saw no signs of Lizer, but only the young man, and near the fire a young woman who had spoken. She moved forward slowly. The room seemed so full, and she felt herself so unusually large, that she was afraid of knocking things over. A new and disagreeable sensation, at which she could only wonder as she took her seat carefully, doubtful if the chair the young woman had placed for her would hold her.

"How much butter have you?" the young lady asked.

"Six pounds," Hannah answered, then waited to hear again the voice that was so different from any voice she had ever heard; different even from Mrs. Skinner's, that itself had been strange to her.

"And what do you ask for it?" the voice went on.

"Two bits, an' hit's good."

"That will be one dollar and a half"; then to the child, "call Susan for me."

Page 27

"I've got some taters," Hannah suggested hesitatingly, pushing her bonnet back a little; "taters, a bushel, good measure an' sound, for a dollar."

"I will take them also."

Hannah rose. "If your things are at the front gate, this is your shortest way out," and the young lady opened a door that led into a hall, then opened also what Hannah recognized as the front door, which Lizer had declared was sealed to traders.

"Did you observe how very handsome that girl was?" the young lady asked of her companion when she returned from the hall.

"I did not," he answered, looking contentedly into the face before him.

"Very handsome, and I am sure she will bring the potatoes in here--she seems quite bewildered."

"I thought she seemed quite at home."

"Not at all. Her voice was very soft, too."

"Yes, and her English had about it that sweet simplicity that dispenses with all extra syllables. The way in which she said 'taters' was lovely."

"I am in earnest; her voice is sweet. I have never seen her before; I wonder what Cove she comes from."

Page 28

"Ask her, and ask her to call again."

"I shall." Here the door opened, and Hannah, with the long bag over her shoulder, entered and stood looking from one to the other. Her bonnet had fallen back, letting the light touch the delicately flushed face, and the dark eyes grown wistful in their uncertainty. She was unquestionably handsome. She put the bag down carefully.

"Did I ax you too much?"

"Oh, no!" the young woman exclaimed. "Here, Susan," to a negress who had entered from the back, "empty these things."

Susan raised the bag with some difficulty. "Dat Wilson woman's in de kitchen, Miss Agnes," she said; "she's got aigs."

"You know I never buy from her," the young lady answered.

Hannah listened, and Susan went away chuckling.

Agnes turned to Hannah. "Sit down and take off your bonnet," she said, herself taking a seat. "What Cove do you come from?"

"Lost Cove."

"Where the stream sinks?"

"Thet's hit; hev you seen hit?"

"No, but I wish very much to see it."

"Hit's a smart piece," Hannah went on, looking

Page 29

into the fire as if making calculations, "but you could go it on a nag."

"Where do you live in Lost Cove?" Agnes went on.

"Hit most all b'longs to Gramper. Mrs. Wilson owns a leetle piece--" then her face burned as she remembered what had just been said about Lizer. Agnes remembered too, and asked:

"Is Mrs. Wilson a friend of yours?"

"She is a neighbor," Hannah said; then, after a moment's pause, "she come alonger me this mornin', kase I didn't know the ways ner the folks, but we couldn't 'gree, an' she leff me at youuns gate."

"I am glad of that. If you had come with her I should not have bought your things; she asks two prices."

"She do thet! But she's mighty poor."

A smile flitted across the young man's face as the words reached him, and he wondered what Hannah's idea of wealth was! "Quantity," would have been her answer, for, to her, this was the only difference. In her world the rich demanded no better quality, only a greater quantity, and, after a certain stage of plentifulness was reached, life was taken with folded hands.

Page 30

"You have never been here before?" Agnes asked.

"Not to peddle, I ain't."

"Will you come again soon?" as the servant put the bag and bucket down by Hannah.

"I hes to bring some apples to a woman to-morrer."

"Then you call bring me some--a bushel?"

"I reckon," and Hannah rose, feeling as glad about coming again as about the much-coveted money she was putting into the old deer-skin purse; then Agnes shook hands with the girl over whom she had cast a spell.

"So you sold out at Agnes Welling's front do'," Mrs. Wilson said mockingly, when she met Hannah at the gate.

"I did, an' I'll wait fur you at the sto' "; then Hannah mounted old Bess and rode away. She did not want to talk to Mrs. Wilson just yet.

"And you did not ask her name?" the young man said when Hannah was gone.

"I forgot it; but was she not handsome? I shall go to Lost Cove this summer."

"We will make up a party," the young man suggested.

"No, I will go alone."

"Honest, at least."

Page 31

Agnes laughed softly. "Still, I mean what I say, Mr. Cartright."

"It is too far for you to go alone, your brother will not permit it."

"We will see." Then Cartright went away, slamming the gate sharply, while Agnes laughed.

Page 32

III

"Turn, Fortune, turn thy wheel with smile or frown;

With that wild wheel we go not up or down.

Our hoard is little, but our heart is great."

It had been a successful day, and as Hannah rode through the falling shadows, with Mrs. Wilson mounted behind her, her heart felt light. She had the coffee and the sugar, besides two dollars toward the plowing, and three bushels of apples engaged, making five dollars--to her a fortune, And this success would mitigate the displeasure of her grandmother, unless talk from the Durkets reached her; that would stop everything.

But above all, she had looked into a new world, and her life seemed to have changed. All the fear of Sewanee was gone. The people up there were strange; that is, different from any people she had known, but she liked them. She was anxious to see that "Miss Agnes" again. She would take more potatoes to-morrow, and some meat; there was no telling how much she might make.

Page 33

She began to hum a tune as they jogged along; for, although Mrs. Wilson's feelings permitted her to ride behind Hannah, they still prevented conversation. It was only at the Warrens' gate that Mrs. Wilson vouchsafed a dignified "Far'well, Hannah Warren," and trudged away across the fields.

Hannah was preoccupied and excited. She had been dead, and now, in some strange way, vigorous and uncontrollable life had come to her. Her impulse was to defy her grandmother, but habit bade her avoid any meeting until she had found out from her grandfather the state of things.

She hung the bag containing her purchases across the fence, and unsaddled the horse. In the kitchen she went through the evening's routine with forced quietness, and ran upstairs for the fodder with a lightness and haste hitherto unknown, laughing softly as, opening the end window farthest from her grandmother's room she tossed the binds out. This would let her carry the milk pails out when she went down, and lessen, by one journey into the house, the danger of meeting Mrs. Warren.

She leaned on the gate as on the afternoon when she decided to peddle; but how different was everything. She felt that she controlled her

Page 34

own fate now; that she could resist her mother and defy Si Durket. In short, she was free, and with the rare joy of having realized her bondage and freedom in the same moment. She might have gone on forever in the old dull path, but for the necessity that drove her to peddling. The fruits of the earth and the beasts of the field had become her protectors against Si Durket. She would never tire of work again. A shadow fell on the joy, and she leaned her head on the gate. "Poor Daddy! If he hed downfaced Granny, an' peddled stiddy, an' not jest traded what happed over, Granny couldn't hev jawed him the way she did, kase he'd hev hed as much as the Durkets. Poor Daddy!" And she recalled the silent, sad-eyed man who had thought himself a failure. The tears rose to her eyes, but did not quench the anger that burned in her heart against her grandmother. "An' I'd abeen jest like him but fur peddlin'."

The clank of the cow-bells broke on her musings, and at the sound happiness brimmed up again. "Does you feel well, cows?" she said. "Si Durket kin say farwell now"; and, holding open the gate, she patted the animals as they came in. This elation lasted until she had to carry wood into her grandmother's room, then unexpectedly her heart failed her.

Page 35

"All she kin do is to kill me," she thought, with an incredulous smile, "an' thet's heap bettern marryin' Si."

"Hardy, Gramper!" she said as she opened the door, and there was such a cheery ring to her voice that Mrs. Warren put her great silver-rimmed spectacles in place to look at her. "How'd you git on 'thout me?" she went on, smiling reassuringly into the old man's eyes as she put down the wood.

"Hit's been some lonesome," he answered; "hit's never been afore thet I've set all day an' never hearn a holler, ner a whistle, ner a step 'bout the ole house thet kin 'member so many a stomp. My Par, an' my brethers, an' my boys, all gone--all gone. But I kin 'member how ever one sot hisn heel to the flo'. I don't see how I'll ever spar' you to go clean away, Hannah,"

"You'll never need to see hit," Hannah answered. "Supper's ready, Granny," she went on, and turned to the door.

Mrs. Warren rose slowly. "You gits meallyer ever day, John Warren," she said, pushing the odd needle through her knitting.

"Thet's right, Mertildy, a good, ripe apple is allers meally."

Page 36

"An' gits rotten-meally--mebbe you knows thet."

"An' you speaks thet to me thet hes been youuns man fur moren fifty yeer, Mertildy?"

"Yes, I do say hit 'bout Hannah," she answered. "Did I think I'd live to see a Warren gal a-tradin' taters like any trash? She'll be a-peddlin' next; an' mebbe you'll marry her to Dock Wilson, jest to hev her a-nigh you."

"Hit mout all come true, Mertildy," and the old man's gentle eyes flashed; "fur peddlin' ain't no sin, an' Dock Wilson ain't never knocked a woman yit."

A dull color came into Mrs. Warren's face. "Si were wrong," she admitted; "but thar's one thing a Durket can't stand, an' thet's bein' jawed by a fool, and Si's Mar were a p'in-blank fool." At the door she met Hannah. It looked almost as if she had been waiting there, in spite of the cold wind that was sweeping through the lobby.

And now the happiness that had left her at the wood-pile came back, as, kneeling in front of the fire, Hannah drew the two silver dollars from her pocket.

"Didn't you git no cawfee an' sugar?" Mrs. Warren asked.

"I did thet, an' brung home this fur the

Page 37

plowin'," and she shook the money triumphantly. Then she told her story, impressing on the old man that she had gone to the shop with money. But she lowered her voice as she told of her meeting Mrs. Harner, and of her engagement for the next day. Mr. Warren, eating slowly, made no comment until she came to the description of her being received in the Wellings' parlor, while a servant emptied her things, and Lizer waited in the kitchen.

"Thet'll tickle Mertildy," he said with a chuckle; "but if you 'lows to go ag'in to-morrer, you must git off 'fore youuns Granny hes time to hender you."

"She can't hold me all day, Gramper, an' she can't tie me."

Mr. Warren regarded his granddaughter curiously. "Granny's ole now, chile," he said, "an' don't you go to makin' her wuss mad 'an is needful. You ain't never seen her rayly mad. I ain't never seen hit but onest, but thet's enough," rubbing one hand slowly round on his bald head. " 'Fair-an'-easy' is a good horse, Hannah, but 'Don't keer' is a galding nag. Thar's no use a-flyin' in Granny's face 'thout thar's a needcessity."

Hannah felt her independence slipping away, and she asked, "What hev you told Granny?"

Page 38

"Thet you hed gone to trade fur cawfee an' sugar, an' I ain't a-goin' to tell her nothing mo' tell I'm obleeged to. She's been worrited an' onsettled all day, mad 'bout Lizer a-goin. Lizer ain't to say a clean-tongued woman."

"Mrs. Wilson's feared o' me," Hannah said contemptuously. Then told again of emptying the apples, and the snubbing she had given Lizer at the gate.

"Thet's what Granny 'll call the 'Durket sperret,' " and the old man smiled as if at the vagaries of a child. "But she sets a heap o' store by you, Hannah."

"She's too hard, Gramper," the girl said coldly. "She stomps youuns feelin's dead, an' then she ain't sati'fy, kase then you've got to feel her way," and the girl's eyes filled with tears. "If I coulder lied or stole, or if I coulder left you an' Daddy, she'd hev druv me to hit long ago. Poor Daddy!" But she dashed the tears away, for, without warning, Mrs. Warren entered. She looked at them sharply, then seated herself near the fire with her knitting. Hannah did not move; she would do nothing that looked like retreat.

"An' what's you been a-cryin' 'bout, Hannah; is you sick?"

"We's been a-talkin', Mertildy," Mr. Warren

Page 39

answered, " 'bout you, and me, an' Joshaway, an' Hannah."

Mrs. Warren was silent, for, unknown to anyone, her heart was sore about her son Joshua. Her last words to him haunted her. She had abused him in the presence of his child. When she ceased, he had shouldered his axe and had gone into the woods, and in the evening had been brought home dead, his life crushed out by a falling tree. Her grief for his death had been unfeigned, and she had spent all she could lay her hands on for his funeral; but she had never said that she was sorry for any of the hard things she had dealt to him throughout his life, and Hannah's young heart had grown hard toward her. But Mrs. Warren remembered, and any mention of his name was a keen pain.

"Youuns daddy were a good son, boy and man," Mr. Warren went on. "He never tole a lie as I kin 'member, an' he never done nothin' he were tole not to do, nur he never hurt nothin' if he knowed hit; an' when youuns Granny were ailin', thar worn't no woman more soffly than Joshaway. An' from the time he were born he hed them kind o' askin' eyes like the critters thet can't say what they wants. An' hit allers hurt me, Joshaway's eyes did, an' when he were leetle

Page 40

I were allers a-givin' him ever'thing he looked at; but all the same hisn's eyes kept on askin' an' askin' to the last."

There was a dead silence in the room save for the click of Mrs. Warren's needles, and the whispering of the fire. Presently Mr. Warren spoke again. "I reckon hisn eyes is satisfy now. I reckon so. An' weuns never hed no words, me an' Joshaway; but I've been right sharp on Pete, an' Dave, an' John; but Joshaway never hurt nobody, an' nobody never hed no 'casion to hurt Joshaway. An' now he's gone afore me. But I reckon hisn eyes is satisfy--I reckon so."

Hannah rose, she could not listen any longer; she would cry out against the hard old woman sitting there with that immovable face. Her taste of freedom that day had unfitted her for the stolid submission of the past. She could not bear it, and she left the room. It scarcely seemed fair that her father should be brought back from his grave to blunt her grandmother's temper. She might be mistaken, and the words have been only loving recollections.

"Ole folks don't hev nothin' to do but 'member things," she whispered, wiping her eyes with the corner of her little shawl, as she stole away to the loft where the apples were stored. She put down the sacks and the measure carefully,

Page 41

and, hanging the lantern on a nail in the low rafters, kneeled down cautiously. "An' Daddy would a-been willin' to be spoke 'bout to save me," the whisper went on, as she carefully picked out the apples and laid them in the measure. The fall of one might call her grandmother up to investigate, and prohibit. When the sacks were filled she lowered them from the window with a rope. It took a long time, and she was shivering uncontrollably when she took the lantern from the nail and crept downstairs.

The meat and the potatoes were easily arranged, for they were in an out-house. In the piazza she piled wood for the morning, and laid the kitchen fire ready for lighting. Her grandmother should have no extra work to complain of.

She took the milk pails and the kettle into her own room, for all must be done before day. And in after-years it seemed to her that her life dated from that cold, dark March morning. She milked, with the lantern casting weird shadows about her, refusing to listen to the strange noises of the wind, and trembled like a thief when she took off her shoes and stole into the kitchen with the milk. She was glad now that the wind was wild and high; she could hear the branch of a tree her father had planted close to the house,

Page 42

scraping against her grandmother's window, and drowning any little noise that she might make.

She drank a bowl of milk, and put a piece of cold corn-bread into her pocket, to serve until she came back, and, as the first light broke in the east, and flashed a crimson flame from point to point of the low-flying clouds, Hannah closed the gate softly and rode away.

The shadows were still black in the woods, and the wind that came tearing down the mountain seemed to wrap round her, and to bend the trees down as if to bar her from this journey. Never before had the sunrise affected her as it did now, and realizing dimly a change in herself, she wondered a little, stopping to look down over the wild, mist-draped scene.

"Everything seems purtier now," she murmured.

A thread of blue smoke rose from among the trees below; she started, gathering up the reins; she knew where that came from.

"An' now poor Gramper's a-steddyin' what to say!" and she urged old Bess forward as if her grandmother might yet sally forth and stop her.

Page 43

IV

"But my being is confused with new experience,

And changed to something other than it was."

"Where are you off to, Max?" The young man addressed was adjusting a shabby gown with much precision.

"To Miss Welling's," Max answered, as with the same care he put on his square cap.

"If I had such a fossil gown," his companion went on from the bed where, though the day was young, he was lounging with a cigarette between his lips, "and such a crummy mortar-board, I'd not put them on with such solemnity and jurisdiction.' "

"If you could show such a cap and gown, Melville, you'd not be a 'Squab' "; and taking up some books, Max left the room.

It was early, but formal visiting hours were ignored in the village of Sewanee, and people kept open house, and "dropped in" on each other when they liked. So Max dropped in and found Miss Welling sewing.

"I have brought the book I spoke of," he

Page 44

began, without further greeting. "This poet ought to capture you, to convert you to himself, for he makes one long to live bravely."

"Or die bravely," Agnes suggested.

"To live is harder. Death cannot be dodged, so there is no use in being afraid; but many things in life can be dodged. I often wonder if education makes any difference in the way one meets death. Is it easier for these country people to let life go than for us?"

"They live like moles," Agnes said, "in comparison we are squirrels; and I think they take a pride in dying. I think the ignorant die calmly because they do not know, and the educated because they do know."

"What?"

"What? why--why, everything; which comprehensive everything is, after all, very limited. Still I believe in education. I know that educated people are happier and better."

"Whew!" and Max pulled his mustache slowly. "If I were sure of that, I should this day begin a crusade with a 'blue-backed' spelling-book as my banner. And you," leaning forward a little, "your duty is to begin at once to teach. If once we realize what is best to be done for our fellows, we must do it."

The door opened and Hannah stood before

Page 45

them with a sack of apples across one shoulder. "Hardy," she said, her face lighting up as she caught sight of Agnes; "har's youuns apples."

"I am glad to see you," and Agnes held out her hand. Max looked from one to the other curiously, then placed a chair near the fire for Hannah. "It is cold," he said. Hannah looked at him a moment, then taking off her long bonnet, sat down on the edge of the chair.

"Yes, and she has come a long way," Agnes answered for her, then turned away to call the servant. Max took up the bag and followed Agnes into the next room, and she going still further, he returned to his place. Hannah watched him until he came back, then looked at the fire, and Max watched her. It was a beautiful face as he saw it now with the firelight on it, and he spoke to her.

"What Cove do you come from?" he asked.

"Lost Cove."

"Then you must be connected with Mr. John Warren, and with his son?"

"He's my Gramper," she answered, in a surprised voice; "and hisn's son, Joshaway?"

"Yes; I met them out hunting last October."

"Joshaway were my Par"--the voice faltered, and the eyes sought the fire. "He were killed in November."

Page 46

"Yes, I heard that. What is your name?"

"Hannah," watching Agnes as she returned.

"And is your grandfather quite well?" Max went on in a quiet way, that put Hannah at her ease and surprised Agnes.

"No, he ain't; he can't stir fur the rheumatiz, an' he ain't done a hand's turn sence hog-killin', jest atter Daddy died, an' I'll hev to hire Dock Wilson to help me plow."

"You plow?"

"Yes, sir."

"Can you read?"

"Some; Mammy hed schoolin', an' she larned dad, an' he larned me. But I don't hev no time, what with the cows, an' the hogs, an' the wood, an' the cookin', an' washin'; an' Granny says book-larnin' is foolishness."

"You must have too much to do; though work is a good friend."

"Thet's what Gramper says. He says work b'ars no gredges an' tells no lies; good work stan's up an' says 'good,' an' bad work stan's up an' says 'bad,' an' thar's no hushin' them, an' hit's true"; then rising, she took up the bag the servant had brought, and held out her hand to Agnes.

"Farwell," she said, "weuns'd be rale proud to see you down home."

Page 47

"Thank you," Agnes said, smiling as Hannah, instead of shaking her hand, turned it over and looked at it curiously. Then she turned to Max. "You must come, too, an' what name shell I name to Gramper?"

"Max Dudley," shaking hands in his turn; "we camped together one night. I was lost and came on his camp. I will bring Miss Welling down"; then he opened the door for Hannah.

Page 48

V

"And answered with such craft as women use,

Guilty or guiltless, to stave off a chance--

That breaks upon them perilously."

Successful as before, Hannah was happy, for, besides a little bag of flour, she had more money than she intended to show even to Mr. Warren. If he knew of this surplus he might reveal it in order to save her from hard words; and if Mrs. Warren knew, it would be stored away and she be left as helpless as before. She had made a long détour to reach the Wilsons' and engage Dock to plow, as she had the money to pay him. She would say four dollars, the rest she must save for other purposes.

Once more on the main road, she urged old Bess on. There was much excitement in her position, and she was anxious yet afraid. How would it be possible to see Mr. Warren alone first? She stopped the horse. "If I keeps on bein' afeard o' Granny," she said aloud, "I'll do sumpen rale mean some day." Old Bess was urged on again. "I'll go right in an' face her, crooked chance or straight chance." She

Page 49

dropped the reins on the horse's neck, and took the old deer-skin purse from her pocket. It was quite full with her two days' gains, and she drew a long sigh. She took out all the money save the four dollars intended for Dock's wages, and tying it up in her glove, hid it in her bosom, then put the purse back in her pocket.

"Hit looks right sneakin', but I must save hit 'ginst Si."

Reaching the gate, she unsaddled the horse with unusual celerity, and shouldering the saddle and the little bag of flour, went quickly into the house.

It had been a long and weary day to the old man. Hannah's errand was a bitter pill to Mrs. Warren. She had never done such a thing in her life, nor was it customary with women of her station. In those early days, "the man who would let his women-folks peddle was a poor sort of man." But the concealment of the expedition had wounded Mrs. Warren also.

Often she had complained that she did not understand Hannah, for though she usually held herself very much aloof, Hannah would yet do work and associate with people that shocked Mrs. Warren, and the irritation caused by what she deemed the girl's peculiarities was a very constant thing.

Page 50

"A goat raised a pup once, Mertildy," her husband had often said to her, "but she never could larn thet pup to butt; an' you'll never larn Hannah youuns ways."

All this ground, and the grievance about Si, had been gone over many times during the day. Mrs. Warren felt herself outwitted, for she was sure the difficulty of plowing had been solved. Her sequence had been--no man to plow--no money to pay a man--no crop, then want, or Si Durket.

"An' why not?" she had asked; "he's well-lookin' --he's well off--he's a man. He cusses some; he gits drunk some, and when he's mad, he is mad. But all the Durkets hes sperret, an' Si ain't none o' your soft-walkin'--still-tongued folks like the Warrens; an' when he walks, he stomps!"

Mr. Warren had told her of Hannah's first venture, how she had sat in the parlor, leaving Lizer in the kitchen--how she showed the "Durket sperret" about the apples, and how, after her purchases, Hannah had two dollars left.

These things had mollified her, until she remembered that they had been concealed from her: and when Hannah entered she turned her face away.

Page 51

"Is you done dinner?" Hannah asked, then looked at her grandmother's averted face.

"Yes, Honey," Mr. Warren answered, twitching her dress furtively; "an' was the woman glad to see you?"

"Yes, and I had a rale nice time. Thar wuz a young man to Miss Agnes Wellin's that knowed you an' Daddy. Says he stayed all night to youuns camp. He's coming to see you, an' Miss Agnes is a-comin' too."

"That's right," Mr. Warren answered heartily; "I 'members that feller, he's named Dudley, and he's rale well-spoken."

"That's hit," Hannah assented, "an' I said as you and Granny would be proud to see 'em if they'd come, an' they said they'd come sure. An' Miss Agnes said I must come again." Then, more slowly, "Them folks at Sewanee is good folks, Gramper, an' the lies Mrs. Wilson tells 'em, an' tells 'bout 'em, is scan'alous! But they knows Lizer."

"And was you all the time a-doin' that?" Mrs. Warren asked curtly.

"No, I stopped a piece at Mrs. Skinner's and at the sto'. Aigs is awful sca'ce; Mrs. Skinner says she'll gimme twenty cents a dozen."

"Thet's a good price, sure," Mr. Warren said. "Did you promise any?"

Page 52

"You said not to say I'd go again," Hannah answered.

"When you is done rubbin' 'gainst the pot, thar ain't no use a-fearing smut," Mrs. Warren put in sharply. "Hannah Warren is done knowed fur a peddler alonger Lizer Wilson an' sich, an' she misewell sell the aigs."

"If you sesso, Granny, I'm surely willin'," and Hannah did not give a sign of the surprise she felt. "An' Dock Wilson says he'll come a-Monday, Gramper."

Mrs. Warren looked up quickly. She saw some of her suspicions being made facts, and realized that Hannah was escaping her. "An' who's to pay?"

"I've got the money," Hannah answered. Then she went her way to the kitchen, where she stood still and drew a long breath of relief.

Page 53

VI

Is she wronged? To the rescue of her honor,

My heart!

Is she poor?--What costs it to become a donor?

Merely an earth to cleave--a sea to part.

But that fortune should have thrust all this upon her!

"Dock Wilson!" Mrs. Wilson stood in the open door of her small log-house. Dock turned and looked from where he sat on the wood-pile whittling, but did not answer, and she raised her voice, "Dinner's done, an' I wish you'd come!"

Dock went on with the whittling, whistling softly. He was tall and fair, with a grave, kind face and his eyes were true. His stepmother, Lizer Wilson, ruled him "to the last notch," people said, but Dock had his own code and went his quiet way, with few words or friends. He had not been in the Cove long. When old man Wilson was dying, he sent for this son; and since his father's death Dock had worked faithfully for his stepmother and her two boys.

In Mrs. Warren's eyes he was contemptible. "Any man that kin stan' Lizer Wilson must hev cotton insides," she would say conclusively, and Hannah began to think of Dock with sympathy.

Page 54

Just now he took his own time about obeying Mrs. Wilson's call. He was in deep thought that he seemed to work into the butter-paddle he was fashioning, whistling softly. He regarded it with some satisfaction, as he shut his knife and dropped it into his cavernous pocket.

"A piece o' glass 'll make hit smooth." He put it away in the hollow of a tree near by, and went into the house.

"Pears like you ain't much honggry," was Mrs. Wilson's greeting.

"I dunno," Dock answered, "I'll try an' see." For a few moments there was silence; then, eying Dock closely, Mrs. Wilson asked:

"What did Hannah Warren want?"

"She wanted to hire some plowin'."

Mrs. Wilson grunted. "Hiren plowin' an' been up twicest this week a-peddlin'. She to set up to run the place on hired han's; she'd better tuck Si Durket an' be done."

Dock shook his broad shoulders a little.

"Is you a-goin' to plow?"

"I am."

"An' I bet you ain't made no trade, jest said you'd do hit."

"Jest so."

"An' what kinder trade is you a-goin' to make?"

Page 55

"If Hannah Warren hes to peddle to pay me, she kin pay what she hes a mind to pay, Hannah is a Sunday gal!"

"An' me an' the boys 'thout rags to ourn backs," rising, as if to keep up her voice; "an' you eatin' like a horse! I ain't a-goin' to stand hit, Dock Wilson, I tell you I ain't! An' thet dratted Hannah Warren thinkin' herself too good to go alonger me. You're a fool--a dead-gone fool! I ain't a-goin' to stand hit!"

Dock, rising, drew his shirt-sleeve slowly across his bearded lips as he rose. Mrs. Wilson seized his arm. "Is you deef?" she cried shrilly. Dock looked down on her.

"No," he answered deliberately, "I ain't deef; an' I b'lieve you could raise the dead, Lizer, much less make the deef hear."

The woman swung away from him. "I sw'ar you'll wish yerseff dead if you don't make a good trade," she said; "I sw'ar you will."

"Thet won't be nothin' new." Then Dock went to a little shanty he had built for himself, where Lizer was denied entrance. He pushed up the fire, and, sitting down, lighted his pipe. Hannah Warren! Her worth had dawned on him gradually. He was first struck by the difference between her and the other women he knew. She reminded him of a pool of water

Page 56

deep under the rocks, where there was no sound of trickling stream--no ripple. In the evening, when the sun was setting and all was still, the purple light on the mountain-side seemed like her. He could not put it into words, but, when he saw these things he would whisper, "Hit 'minds me o' her." He did not dream of lifting his eyes to Hannah, he had scarcely ever spoken to her; but this far-off influence had changed his life. Now she had sought him. She had called him, softly, "Dock!" and when he stood beside her horse and looked up, the fair face seemed doubly fair, shining from the depths of her long bonnet. Drive a bargain with Hannah! he would see Lizer dead and buried first. It hurt him to think of her going about Sewanee peddling. It was very well for Lizer and the like, but Hannah was different. He had heard enough to make him sure she was peddling to save herself from Si Durket, and that she peddled against her grandmother's will. He had seen her cutting wood, and hauling it, too. Already he had carried wood there in the night, not enough to attract attention, but enough to help her. He must help her against Si, or he would have to kill Si. A quarrel was "easy picked."

Presently Mrs. Wilson's voice, ordering the

Page 57

boys to bring in wood, reminded him that the more wood he cut to-day, the more time he would have to help Hannah next week. He put down his pipe, and soon the quick, sharp strokes of the axe rang through the stillness, until Hannah could hear them between her own less powerful blows.

She listened, and wondered what wages he would demand. Speaking to him, she had become sure of his goodness, and felt that if he knew how hardly she was bestead, he would not push her.

"But I can't tell him, if his heart is kind."

Si would come over the next day, it being Sunday, and she longed for snow or rain, even to the detriment of the plowing, to keep him at home. But before evening the clouds were swept away before a stinging northwest wind, and the morning dawned brilliantly clear.

"You'll hev a good week a-plowin'," Mr. Warren said, as he ate his breakfast.

"But we'll hev Si to-day," Hannah answered, "an' Granny will r'ar an' pitch if he riles her 'bout the peddlin'."

"Mebbe he won't say nothin', an' you kin keep him pleased."

Hannah looked up quickly. "If I makes b'lieve to favor him, I kin," she said; "but that's

Page 58

a big lie, Gramper, an' surely you don't mean hit, kase if you goes against me I'll go and hire out."

"Lord! youuns Granny'll die!"

"Well, she'll hev to die 'fore I'll tuck Si." She felt strong now that she had a little money laid by; nevertheless her heart quailed a little when she saw Si dismount at the gate. She heard him come into her grandfather's room, and she longed to run away; instead, she emptied the water from the buckets, and, when the dishes were put away, sat with buckets on either side and her bonnet on. Presently a chair was moved, and Hannah was gone. Si found the kitchen empty. But, lengthen it as she would, the work was done at last, and when Mrs. Warren called her she had to go. She took her seat close to her grandfather, who laid his hand on hers, that rested on the arm of his chair.

Si was giving a grand description of a visit he had made lately to Chattanooga. It was something to have traveled on the railway, but a visit to Chattanooga was a thing to date from. He had brought back some "seegyars," one of which he now smoked with much ostentation.

Mrs. Warren looked and listened to her nephew with undisguised admiration, every now and then putting in an encouraging exclamation.

Page 59

This great man was a Durket--the Warrens could not have produced him. She had tried her best to make her boys Durkets. She had showed them the "Durket sperret" faithfully; but each son, as he married, chose the quietest woman he could find. And now her granddaughter, who had this golden opportunity of mating with the flower of the Durkets, refused--and stood to her refusal with a strength in which Mrs. Warren might have seen a strain of "Durket sperret," if she had not been convinced that it was Warren obstinacy.

Presently Hannah was sent to see after dinner, then Si said: "We'll walk a piece after grub, Hannah."

"I dunno--"

"Yes, you do!" Mrs. Warren struck in; "I'll clean up--go 'long."

Hannah was tempted to hide, but the storm would then fall on her grandfather, who was bound to his chair, and always at the mercy of that merciless tongue. She must go with Si, and if there was a battle to be fought she must fight it.

"If there's a bad place in the road, pick up youuns foot an' cross it quick," she said to herself as she put the dinner on table--"thar' ain't no use in doubtin'--git over." Then she helped

Page 60

her grandfather, and went back into the room as Mrs. Warren and Si left it.

She found that as yet nothing had been said about the peddling, and Si seemed in a good humor.

"But he hes hearn," Hannah thought, and took as long as she could to eat her own dinner.

At last the time came, and she passed quickly through the gate that Si held open, and turned into the public road going down the Cove. The bare trees along the mountain-tops seemed to be cut in ebony against the brilliant blue. The buds were swelling--the moss and lichens on the gray bowlders looked a brighter hue, the fields spread brown and ready for work, the birds were flying about busily, and through the stillness came the sound of falling water. The winter was done, and all nature was glad for the warm, soft wind that touched it into life again. The feeling swept over Hannah, too--a thrill of health and strength. The young year called to her youth that sprang forward to meet it. How happy she could have been! Si was still telling of the glories of Chattanooga, and Hannah had begun to hope that the walk would terminate peacefully, when he turned and said:

"Would you like to live to Chattynoogy?"

Page 61

Hannah started, and answered, more sharply than was wise: "No, I wouldn't."

"An' why not?"

"Kase I ain't heard you tell 'bout nothin' thar 'ceppen cussin' an' whisky, an' I hates both."

Si laughed and pulled a flat bottle out of his pocket. "Thet's the best friend in the country," he said, "an' you'd soon larn to like hit-- hit's good. Why, gal, thet cost nigh onter two dollars a gallon! But Si Durket ain't feared o' spendin'."

Hannah was silent, hoping that Si would go on talking as he had done before, but he had other intentions.

"Would you like to live 'cross the mountain?" he asked, stooping to look under her bonnet.

Hannah drew back quickly. "No, I wouldn't"; and the tone of disgust in her voice cut her cousin like a lash.

"Damn it, then, you needn't!" he answered viciously, kicking a stone into the fields that lay below them. "An' peddlin' is what you likes-- peddlin' alonger Lizer Wilson an' Jane Harner an' sich--sittin' round folks' back do's alonger the niggers till the fine ladies come to buy; you likes thet."

Page 62

"Peddlin' is hones'," Hannah answered, and turned toward the house. She was afraid to go farther away with Si in this humor.

"Whar's you a-goin'?"

"To milk the cows!"

"Damn the cows!" but Hannah walked on, and he had to follow her or be left. He made a long step. "Hannah!" and he caught her sleeve. She stopped and looked at him quietly. "Is you a-goin' to marry me?"

Hannah turned her head away and moved forward as if deliberating; but Si held her sleeve.

"Is you?" drawing nearer. Hannah took off her bonnet and turned it about in her hands.

"Weuns don't suit, Si," dropping the bonnet, and Si, stooping for it, let go her sleeve.

"Hit suits me, an' hit suits Aunt Tildy; you is the only one that can't be satisfy."

"Well, I'm the main one," her voice growing firmer, as she caught sight of Dock Wilson in a field near by. But Si went on with a patience that surprised her.

"An' what about me don't please you?" he asked.

Hannah shook her head, "Fire don't suit water," she answered, "An' corn won't grow outer 'tater eyes, but I dunno why."

"An' you won't?"

Page 63

"I can't."

"An' who's a-goin' to run this place an' feed the old folks?"

"I is."

"Peddlin'? Not if I knows hit. None o' my women folks ain't a-goin' to do thet, an' I'll show Aunt Tildy why. I knowed you were up to some trick when I hearn Jane Harner a-tellin', but you'll not go agin. If you do, thar'll be sicher talk raised as'll compel you to tuck anybody that axes you. An' everybody knows thet whoever comes nighst Hannah Warren is got Si Durket to fight."

Hannah walked on, silent.

"Does you onderstan'?" Si repeated, his head seeming to flatten in his anger like the head of a snake.

"I do--an' I tell you right now, Si, thet Hannah Warren 'll stay Hannah Warren furever," her eyes burning ominously into his. "You ner Granny can't skeer me; an' you kin tell all the lies you wants to 'bout me, kase if lies grows fast, truth grows strong."

Si uttered a great oath and raised his arm. Hannah smiled.

"You knocked youun's mammy, but--" then she paused, for at her words a livid hue overspread his face, and his arm dropped. For

Page 64

a moment she watched him, then walked away; and Dock, out in the fields, kept her well in sight.

The cows were gathered round the gate, and, letting them in, she went for the pails and food. Mrs. Warren met her.

"Whar's Si?" she asked. Hannah pointed to an elevated part of the road, where Si could be seen leaning against a tree, and Mrs. Warren let her go. She was trembling with excitement, and longed to warn her grandfather of the gathering storm. She led the cows to a position that her grandfather could see from the window, and Si coming in would not pass near. She heard a cheerful whistle, and saw Dock leaning on the fence, looking over the fields they would plough the next day. She took no notice, but was glad he was near.

Steadily she went on with the milking, wondering why Si did not come. It was possible that he was emptying the bottle he had shown her; if so, anything might happen. At last he came, and passing without a word, went into the house. She saw that he still had her bonnet in his hand; perhaps he was not very drunk, but she shivered a little. She was milking the last cow when voices reached her. Her grandmother's voice, rising higher and higher, and Mr. Warren's

Page 65

weaker tones calling out, "Mertildy! Mertildy!" Dock's whistle rose with the voices, and she saw that he had climbed the fence and was sitting on the wood-pile. He nodded as she looked, and she nodded in return.

"Hannah Warren!" She started--her grandmother was standing in the open lobby. She took up the pails and went in. There was no fear or nervousness in her demeanor, except that her hands trembled a little as she strained the milk; but even that had ceased by the time she washed them, and, pulling down her sleeves, turned to face her grandmother.

Mrs. Warren did not understand the expression on the young face that looked so full in hers; an expression of cold hardness mixed with a little contempt; a look the old woman had never met before. For the moment she was disconcerted and turned toward her room, then, the spell of the look being broken, her voice rose sharp and clear. "This away!" she called; "come right in; I'll hev the truth o' this dratted business or die--come in!" But Hannah felt secure; her grandmother had flinched before her look, and instantly she felt a pity for what was weaker than herself. She would explain and keep the peace if possible, and she took her seat near her grandfather, just opposite Si.

Page 66

"An' now, Hannah Warren, jes say what you mean by a-lyin' 'bout apples as were promised; jest tell the truth if you kin, fur I'll hev it outer you or die!" and Mrs. Warren's voice was rasping in its bitterness as she stood with arms akimbo, glaring at the two who sat so close together.

"Hit worn't no lie; I did tuck up apples I hed promised to Miss Agnes Wellin' and Mrs. Skinner."

"An' the meat an' the taters, whar'd you sell them?" stamping her foot as she came near. A faint color came in Hannah's face, but she answered, quietly still:

"I dunno what thet woman were named."

"No, thet you don't!" coming nearer still, and working herself up to a pitch of anger that would soon be beyond control; "but Si knows, he's 'cute as you, stealin' fust an' lyin' atterwards. How dar' you tuck them things--how dar' you go a-peddlin' 'thout axin' me--how dar' you--how dar' you do hit!"

"I never lied, an' I never stole, Granny," the girl answered, rising to her feet, "an' if you're a-goin' to keep Si Durket to crawl round an' spy on me, I'm a-goin'." She had risen because she expected now, what had always come with any burst of anger, quick, hard blows. And as

Page 67

she finished speaking the brown, sinewy old fist flashed up, but as quickly the girl caught it in her strong young hand--an action that was more to Mrs. Warren than a return blow would have been, for it meant not war, but victory.

"Granny"--the low voice trembled, and the dark eyes flashed--"I've done tuck my last orders, an' I've done tuck my last blow. I'm a woman now, an' you must larn to 'member hit." A silence fell that seemed the silence of death, as the anger on the old face changed to terror, and a gray hue spread from lips to brow --a deadly gray hue as the fierce old eyes grew dim, and a slight foam came on the parched lips. It was an awful change, scarcely realized by the girl until a low cry from her grandfather made her spring forward and catch the reeling figure.

"Help me, Si!" she called, and between them they laid Mrs. Warren on the bed. "Open the winders an' fetch some water--" and while Si, half dazed with liquor, clumsily obeyed, Hannah loosened the old woman's clothes, and Mr. Warren, unable to move, wrung his hands.

"She's hed hit afore!" he wailed, "an' they said not to make her mad no mo'--an' we never did--oh, Lord! hev mussy--hev mussy! I oughter hev tole Hannah, an' I never did. I

Page 68

never hed no 'casion, she were such a peaceable chile--an' now--Lord, hev mussy--hev mussy!"

No, they had never told her. With the old man's words there came to Hannah the memory of the years through which all had bowed to the relentless will of this old woman. She had thought there was some truth in her grandmother's scorn for the weakness of the Warrens that yielded so quietly to the "Durket sperret," and she had determined to vindicate the Warrens --alas! Those strong men submitted because they were strong, and the old woman ruled because she was weak. And now in her pride she had made all those years of sacrifice of no avail! There came a weak sigh. "Hesh, Gramper," she said, softly, to still the old man's wail, and motioned Si from the room. The sight of him would recall too much.