Swallow Barn, or A Sojourn in the Old Dominion.

In Two Volumes. Vol. I:

Electronic Edition.

Kennedy, John Pendleton, 1795-1870.

Funding from the University of North Carolina Library supported the electronic publication of this title.

Text transcribed by

Apex Data Services, Inc.

Images scanned by

Bond Thompson

Text encoded by

Apex Data Services, Inc., and Sarah Ficke

First edition, 2006

ca. 468K

University Library, UNC-Chapel Hill

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill,

2006.

Source Description:

(title page) Swallow Barn, or A Sojourn in the Old Dominion. In Two Volumes. Vol. I.

[Kennedy, John Pendleton]

x, 312 p.

Philadelphia:

Carey & Lea, Chesnut Street.

1832.

Call number PS2162 .S9 (Rare Book Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

This electronic edition is a part of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill digital library, Documenting the American South.

The text has been entered using double-keying and verified against the original.

The text has been encoded using the recommendations for Level 4 of the TEI in Libraries Guidelines.

Original grammar, punctuation, and spelling have been preserved. Encountered typographical errors have been preserved, and appear in red type.

Any hyphens occurring in line breaks have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line.

All quotation marks, em dashes and ampersand have been transcribed as entity references.

All double right and left quotation marks are encoded as " and " respectively.

All single right and left quotation marks are encoded as ' and ' respectively.

All em dashes are encoded as --

Indentation in lines has not been preserved.

Running titles have not been preserved.

Library of Congress Subject Headings

Languages Used:

- English

- Latin

LC Subject Headings:

Revision History:

- 2006-,

Celine Noel and Wanda Gunther

revised TEIHeader and created catalog record for the electronic edition.

-

2006-06-12,

Sarah Ficke

finished TEI-conformant encoding and final proofing.

-

2005-03-05,

Sarah Ficke

finished TEI/SGML encoding.

- 2004-03-22,

Apex Data Services, Inc.

finished transcribing the text.

[Cover Image]

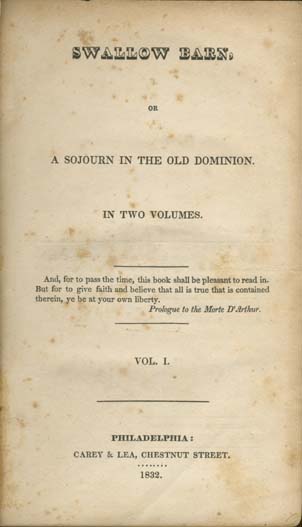

[Title Page Image]

[Title Page Verso Image]

SWALLOW BARN,

OR

A SOJOURN IN THE OLD DOMINION.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

And, for to pass the time, this book shall be pleasant to read in. But for to give faith and believe that all is true that is contained therein, ye be at your own liberty.

Prologue to the Morte D'Arthur.VOL. I.

PHILADELPHIA:

CAREY & LEA, CHESTNUT STREET.

1832.

Page verso

Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1832, by CAREY & LEA, in the Clerk's office of the District Court, for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania.

C. SHERMAN & CO. PRINTERS,

St. James Street, Philadelphia.

Page iii

TO WILLIAM WIRT, ESQ.

DEAR SIR,

I HAVE two reasons for desiring to inscribe this book to you. The first is, that you are likely to be on a much better footing with posterity than may ever be my fortune; seeing that, some years gone by, you carelessly sat down and wrote a little book, which has, doubtless, surprised yourself by the rapidity with which it has risen to be a classic in our country. I have sat down as carelessly, to a like undertaking, but stand sadly in want of the wings that have borne your name to an enviable eminence. It is natural, therefore, that I should desire your good-will with the next generation.

My second reason is, that I have some claim upon your favour in the attempt to sketch the features of the Old Dominion, to whose soil and hearts your fame and feelings are kindred. In these pages you may recognize, perhaps, some old friends, or, at least, some of their customary haunts; and I hope, on that

Page iv

score, to find grace in your eyes, however I may lack it in the eyes of others.

I might add another reason, but that is almost too personal to be mentioned here: It is concerned with an affectionate regard for the purity and worth of your character, with your genius, your valuable attainments, your many excellent actions, and, above all, with your art of embellishing and endearing the relations of private life. These topics are not to be discussed to your ear,--and not, I hope, (to their full extent,) for a long time, to that of the public.

Accept, therefore, this first-fruit of the labours (I ought rather to say, of the idleness) of your trusty friend,

MARK LITTLETON.

April 21, 1832.

Page v

CONTENTS OF VOL. I.

- Introductory Epistle, . . . . . 1

- CHAP. I. Swallow Barn, . . . . . 19

- II. A Country Gentleman, . . . . . 25

- III. Family Portraits, . . . . . 33

- IV. Family Paragons, . . . . . 41

- V. Ned Hazard, . . . . . 51

- VI. Pursuits of a Philosopher, . . . . . 66

- VII. Traces of the Feudal System, . . . . . 74

- VIII. The Brakes, . . . . . 82

- IX. An Eclogue, . . . . . 87

- X. Colloquies, . . . . . 97

- XI. Pranks, . . . . . 105

- XII. An Embarrassed Lover, . . . . . 114

- XIII. A Man of Pretensions, . . . . . 132

- XIV. My Grand Uncle, . . . . . 145

- XV. The Old Mill, . . . . . 154

- XVI. Proceedings at Law, . . . . . 163

- XVII. Strange Symptoms, . . . . . 172

- XVIII. The National Anniversary, . . . . . 178

- XIX. The County Court, . . . . . 189

- XX. Opinions and Sentiments, . . . . . 201

Page vi - CHAP. XXI. Philpot Wart, . . . . . 207

- XXII. The Philosopher Unbent, . . . . . 217

- XXIII. Trial by View, . . . . . 229

- XXIV. Merriment and Sobriety, . . . . . 246

- XXV. The Old School, . . . . . 253

- XXVI. The Raking Hawk, . . . . . 267

- XXVII. The Award, . . . . . 281

- XXVIII. The Goblin Swamp, . . . . . 294

Page vii

PREFACE.

I HAVE had great difficulty to prevent myself from writing a novel. The reader will perceive that the author of these sketches left his home to pass a few weeks in the Old Dominion, having a purpose to portray the impressions which the scenery and the people of that region made upon him, in detached pictures brought together with no other connexion than that of time and place. He soon found himself, however, engaged in the adventures of domestic history, which wrought so pleasantly upon him, and presented such a variety of persons and characters to his notice, that he could not forbear to describe what he saw. His book therefore, in spite of himself, has ended in a vein altogether different from that in which it set out. There is a rivulet of story wandering through a broad meadow of episode. Or, I might truly say, it is a

Page viii

book of episodes, with an occasional digression into the plot. However repugnant this plan of writing may be to the canons of criticism, yet it may, perhaps, amuse the reader even more than one less exceptionable.

The country and the people are at least truly described; although it will be seen that my book has but little philosophy to recommend it, and much less of depth of observation. In truth, I have only perfunctorily skimmed over the surface of a limited society, which was both rich in the qualities that afford delight, and abundant in the materials to compensate the study of its peculiarities. If my book be too much in the mirthful mood, it is because the ordinary actions of men, in their household intercourse, have naturally a humorous or comic character. The passions that are exhibited in such scenes are moderate and amiable; and a true narrative of what is amiable in personal history is apt to be tinctured with the hue of a lurking and subdued humour. The under-currents of country-life are grotesque, peculiar and amusing, and it only requires an attentive observer to make an agreeable book by describing them. I do not think any one will say that my pictures are exaggerated or false in their proportions; because I have not striven to produce effect: they will, doubtless, be found insufficient in many respects, and I may be open

Page ix

to the charge of having made them flat and insipid. I confess the incompetency of my hand to do what, perhaps, my reader has a right to require from one who professes a design to amuse him. Still I may have furnished some entertainment, and that is what I chiefly aimed at, although negligently and unskilfully.

As to the events I have recounted, upon what assurance I have given them to the world, how I came to do so, and with what license I have used names to bring them into the public eye, those are matters betwixt me and my friends, concerning which my reader would forget himself if he should be over-curious. His search therein will give him but little content; and if I am driven into straits in that regard, I shelter myself behind the motto on my title-page, the only one I have used in this book. Why should I not have my privilege as well as another?

If this my first venture should do well, my reader shall hear of me anon, and much more, I hope, to his liking: if disaster await it, I am not so bound to its fortunes but that I can still sleep quietly as the best who doze over my pages.

The author of the Seven Champions has forestalled all I have left to say; and I therefore take the freedom to conclude in his words:

"Gentle readers,--in kindness accept of my labours,

Page x

and be not like the chattering cranes nor Momus' mates, that carp at every thing. What the simple say, I care not; what the spightful speak, I pass not: only the censure of the conceited I stand unto; that is the mark I aym at, whose good likings if I obtain, I have won my race."

MARK LITTLETON.

Page 1

INTRODUCTORY EPISTLE.

TO ZACHARY HUDDLESTONE, ESQ.

PRESTON RIDGE, NEW YORK.

DEAR ZACK,

I CAN imagine your surprise upon the receipt of this, when you first discover that I have really reached the Old Dominion. To requite you for my stealing off so quietly, I hold myself bound to an explanation, and, in revenge for your past friendship, to inflict upon you a full, true, and particular account of all my doings, or rather my seeings and thinkings, up to this present writing. You know my cousin Ned Hazard has been often urging it upon me,--so often that he began to grow sick of it,--as a sort of family duty, to come and spend some little fragment of my life amongst my Virginia relations, and I have broken so many promises on that score, that, in truth, I began to grow ashamed of myself.

Upon the first of this month a letter from Ned reached me at Longsides, on the North River, where I then was with my mother and sisters. Ned's usual tone of correspondence is that of easy, confiding intimacy, mixed up, now and then, with a slashing raillery against some imputed foibles, upon

Page 2

which, as they were altogether imaginary, I could afford to take his sarcasm in good part. But in this epistle he assumed a new ground, giving me some home thrusts, chiding me roundly for certain waxing bachelorisms, as he called them, and intimating that a crust was evidently hardening upon me. A plague upon the fellow! You know, Zachary, that neither of us is so many years ahead of him.--My reckoning takes in but five years, eleven months and fifteen days--and certainly, not so much by my looks.--He insinuated that I had arrived at that inveteracy of opinion for which travel was the only cure; and that, in especial, I had fallen into some unseemly prejudices against the Old Dominion which were unbecoming the character of a philosopher, to which, he affirmed, I had set up pretensions; and then came a a most hyperbolical inuendo,--that he had good reason to know that I was revolving the revival of a stale adventure in the war of Cupid, in which I had been aforetime egregiously baffled, "at Rhodes, at Cyprus, and on other grounds." Any reasonable man would say, that was absurd on his own showing. The letter grew more provoking--it flouted my opinions, laughed at my particularity, caricatured and derided my figure for its leanness, set at nought my complexion, satirized my temper, and gave me over corporeally and spiritually to the great bear-herd, as one predestined to all kinds of ill luck with the women, and to be led for ever as an ape. His epistle, however, wound up like a sermon, in a perfect concord of sweet sounds, beseeching me to forego my idle

Page 3

purpose; (Cupid, forsooth!) to weed out all my prejudicate affections, as well touching the Old Dominion as the other conceits of my vain philosophy, and to hie me, with such speed as my convenience might serve withal, to Swallow Barn, where he made bold to pledge me an entertainment worthy of my labour.

It was a brave offer, and discreetly to be perpended. I balanced the matter, in my usual see-saw fashion, for several days. It does mostly fall out, my dear Zack (to speak philosophically), that this machine of man is pulled in such contrary ways, by inclinations and appetites setting diversely, that it shall go well with him if he be not altogether balanced into a pernicious equilibrium of absolute rest. I had a great account to run up against my resolution. Longsides has so many conveniences; and the servants have fallen so well into my habitudes; and my arm-chair had such an essential adaptation to my felicity; and even my razors were on such a stationary foundation--one for every day of the week--as to render it impossible to embark them on a journey; and my laundress had just begun to comprehend, after a severe indoctrination, the precise quantum of starch, and the proper breadth of fold, for my cravat; to say nothing of the letters to write, and the books to read, and all the other little cares that make up the sum of immobility in a man who does not care much about seeing the world; so that, in faith, Zachary, I had a serious matter of it. And then, after all, I was, in fact, plighted to my sister Louisa to go with her up the river, you know where. This,

Page 4

between you and me, was the very thing that brought down the beam. That futile, nonsensical flirtation! But for this fantastic conceit crossing my mind with the bitterness of its folly, I should indubitably have staid at home.

There are some junctures in love and war both, where your lying is your only game; for as to equivocating, or putting the question upon an if or a but, it is a downright confession. If I had refused Ned's summons, not a whole legion of devils could have driven it out of his riveted belief, that I had been kept at home by that maggot of the brain which he called a love affair. And then I should never have heard the end of it!

"I'll set that matter right at least," quoth I, as I folded up his letter. "Ned has reason too," said I, suddenly struck with the novelty of the proposed journey, which began to show in a pleasant light upon my imagination, as things are apt to do, when a man has once relieved his mind from a state of doubt:--"One ought to travel before he makes up his opinion: there are two sides to every question, and the world is right or wrong; I'm sure I don't know which. Your traveller is a man of privileges and authoritative, and looks well in the multitude: a man of mark, and authentic as a witness. And as for the Old Dominion, I'll warrant me it's a right jolly old place, with a good many years on its head yet, or I am mistaken--By cock and pye, I'll go and see it!--What ho! my tablets,"--

Behold me now in the full career of my voyage of

Page 5

discovery, exploring the James River in the steamboat, on a clear, hot fifteenth of June, and looking with a sagacious perspicacity upon the commonest sights of this terra incognita. I gazed upon the receding headlands far sternward, and then upon the sedgy banks where the cattle were standing leg-deep in the water to get rid of the flies: and ever and anon, as we followed the sinuosities of the river, some sweeping eminence came into view, and on the crown thereof was seen a plain, many-windowed edifice of brick, with low wings, old, ample and stately, looking over its wide and sun-burnt domain in solitary silence: and there were the piney promontories, into whose shade we sometimes glided so close that one might have almost jumped on shore, where the wave struck the beach with a sullen plash: and there were the decayed fences jutting beyond the bank into the water, as if they had come down the hill too fast to stop themselves. All these things struck my fancy, as peculiar to the region.

It is wonderful to think how much more distinct are the impressions of a man who travels pen in hand, than those of a mere business voyager. Even the crows, as we sometimes scared them from their banquets with our noisy enginery, seemed to have a more voluble, and, I may say, eloquent caw here in Virginia, than in the dialectic climates of the North. You would have laughed to see into what a state of lady-like rapture I had worked myself, in my eagerness to get a peep at James Town, with all my effervescence of romance kindled up by the renown

Page 6

of the unmatchable Smith. The steward of the boat pointed it out when we had nearly passed it--and lo! there it was--an old steeple, a barren fallow, some melancholy heifers, a blasted pine, and, on its top, a desolate hawk's nest. What a splendid field for the fancy! What a carte blanche for a painter! With how many things might this little spot be filled!

What time bright Phoebus--you see that James Town has made me poetical--had thrown the reins upon his horse's neck, and got down from his chafed saddle in the western country, like a tired mail carrier, our boat was safely moored at Rocket's, and I entered Richmond between hawk and buzzard--the very best hour, I maintain, out of the twenty-four, for a picturesque tourist. At that hour, it may be affirmed generally, that Nature is an absolute liar. The landscape becomes like one of Hubard's cuttings--every thing jet black against a bright horizon: nothing to be seen but profiles, with all the shabby fillings-up kept dark. Shockoe Hill was crested with what seemed palaces embowered in groves and gardens of richest shade; the chimneys numberless, like minarets; and the Parthenon of Virginia, on its appropriate summit, stood in another Acropolis, tracing its broad pediment upon the sky in exaggerated lines. There, too, was the rush of waters tumbling around enchanted islands, and flashing dimly on the sight. The hum of a city fell upon my ear; the streets looked long and the houses high, and every thing brought upon my mind that misty impression

Page 7

which, Burke says, is an ingredient of the sublime, and which, I say, every stranger feels on entering a city at twilight.

I was set down at "The Union," where, for the first hour, being intent upon my creature comforts, my time passed well enough. The abrupt transition from long continued motion to a state of rest makes almost every man sad, exactly as sudden speed makes us joyous; and for this reason, I take it, your traveller in a strange place, is, for a space after his halt, a sullen, if not a melancholy animal. The proofs of this were all around me; for here was I--not an unpractised traveller either--at my first resting place after four days of accelerated progression, for the first time in my life in Richmond, in a large hotel, without one cognizable face before me, full of excellent feelings, without a power of utterance. What would I have given for thee, or Jones, or even long Dick Hardesty! In that ludicrous conflict between the social nature of the man and his outward circumstances, which every light-hearted voyager feels in such a situation as mine, I grew desponding. Talk not to me of the comfort of mine own inn! I hold it a thing altogether insufficient. A burlesque solitariness sealed up the fountains of speech, of the crowd who were seated at the supper table; and the same uneasy sensation of pent-up sympathies was to be seen in the groups that peopled the purlieus of the hotel. A square lamp that hung midway over the hall, was just lit up, and a few insulated beings were sauntering backward and forward in its light: some

Page 8

loitered in pairs, in low and reserved conversation; others stalked alone in incommunicable ruminations, with shaded brows, and their hands behind their backs. One or two stood at the door humming familiar catches and old madrigals, in thoughtful medleys, as they gazed up and down the street, now clamorous with the din of carts, and the gossip of serving-maids, discordant apprentice boys, and over-contented blacks. Some sat on the pavement, leaning their chairs against the wall, and puffing segars in imperturbable silence: all composing an orderly and disconsolate little republic of humoursome spirits, most pitifully out of tune.

I was glad to take refuge in an idle occupation; so I strolled about the city. The streets, by degrees, grew less frequented. Family parties were gathered about their doors, to take the evening breeze. The moon shone bright upon some bevies of active children, who played at racing games upon the pavements. On one side of the street, a contumacious clarionet screamed a harsh bravado to a thorough-going violin, that on the opposite side, in an illuminated barber-shop, struggled in the contortions of a Virginia reel. And, at intervals, strutted past a careering, saucy negro, with marvellous lips, whistling to the top of his bent, and throwing into shade halloo of schoolboy, scream of clarionet, and screech of fiddle.--

Towards midnight a thunder gust arose, accompanied with sharp lightning, and the morning broke upon me in all the luxuriance of a cool and delicious atmosphere.

Page 9

You must know that when I left home, my purpose was to make my way direct to Swallow Barn. Now, what think you of my skill as a traveller, when I tell you, that until I woke in Richmond on this enchanting morning, it never once occurred to me to inquire where this same Swallow Barn was! I knew that it was in Virginia, and somewhere about the James River, and therefore I instinctively wandered to Richmond; but now, while making my toilet, my thoughts being naturally bent upon my next movement, it very reasonably occurred to me that I must have passed my proper destination the day before, and, full of this thought, I found myself humming the line from an old song, which runs, "Pray what the devil brings you here!" The communicative and obliging bar-keeper of the Union soon put me right. He knew Ned Hazard as a frequent visiter of Richmond, and his advice was, that I should take the same boat in which I came, and shape my course back as far as City Point, where he assured me that I might find some conveyance to Swallow Barn, which lay still farther down the river, and that, at all events, "go where I would, I could not go wrong in Virginia." What think you of that? Now I hold that to be, upon personal experience, as true a word as ever was set down in a traveller's breviary. There is not a by-path in Virginia that will take a gentleman who has time on his hands, in a wrong direction. This I say in honest compliment to a state that is full to the brim of right good fellows.

The boat was not to return for two days, and I therefore

Page 10

employed the interval in looking about the city. Don't be frightened!--for I neither visited hospitals, nor schools, nor libraries, and therefore will not play the tourist with you: but if you wish to see a beautiful little city, built up of rich and tasteful villas, and embellished with all the varieties of town and country, scattered with a refined and exquisite skill--come and look at Shockoe Hill in the month of June.--You may believe, then, I did not regret my aberration.

At the appointed day I re-embarked, and in due time was put down at City Point. Here some further delay awaited me. This is not the land of hackney coaches, and I found myself somewhat embarrassed in procuring an onward conveyance. At a small house, to which I was conducted, I made my wishes known, and the proprietor kindly volunteered his services to set me forward. It was a matter of some consideration. The day was well advanced, and it was as much as could be done to reach Swallow Barn that night. An equipage, however, was at last procured for me, and off I went. You would have laughed "sans intermission" a good hour, if you had seen me upon the road. I was set up in an old sulky, of a dingy hue, without springs, with its body sunk between a pair of unusually high wheels, that gave it something of a French shrug. It was drawn by an asthmatic, superannuated racer, with a huge Roman nose and a most sorrowful countenance. His sides were piteously scalded with the traces, and his harness, partly of rope and partly of

Page 11

leather thongs, corresponded with the sobriety of his character. He had fine long legs, however, and got over the ground with surprising alacrity. At a respectful distance behind me trotted the most venerable of outriders--an old free negro, formerly a retainer in some of the feudal establishments of the low country. His name was Scipio, and his face, which was principally made up of a pair of lips hanging below a pair of nostrils, was well set off with a head of silver wool that bespoke a volume of gravity. He had, from some aristocratic conceit of elegance, indued himself for my service in a cast-off dragoon cap, stripped of its bear skin; a ragged remnant of a regimental coat, still jagged with some points of tarnished scarlet; and a pair of coarse linen trowsers, barely reaching the ankles, beneath which two bony feet occupied shoes, each of the superficies and figure of a hoe, and on one of these was whimsically buckled a rusty spur. His horse was a short, thickset pony, with an amazingly rough trot, which kept Scipio's legs in a state of constant warfare against the animal's sides, whilst the old fellow bounced up and down in his saddle with the ambitious ostentation of a groom in the vigour of manhood, and proud of his horsemanship.

Scipio frequently succeeded, by dint of hard spurring, to get close enough to me to open a conversation, which he conducted with such a deferential courtesy and formal politeness, as greatly to enhance my opinion of his breeding. His face was lighted up with a lambent smile, and he touched his hat with an antique

Page 12

grace at every accost; the tone of his voice was mild and subdued, and in short, Scipio, though black, had all the unction of an old gentleman. He had a great deal to say of the "palmy days" of Virginia, and the generations that in his time had been broken up, or, what in his conception was equivalent, had gone "over the mountain." He expatiated, with a wonderful relish, upon the splendours of the old fashioned style in that part of the country; and told me very pathetically, how the estates were cut up, and what old people had died of, and how much he felt himself alone in the present times--which particulars he interlarded with sundry sage remarks importing an affectionate attachment to the old school, of which he considered himself no unworthy survivor. He concluded these disquisitions with a reflection that amused me by its profundity--and which doubtless he picked up from some popular orator: "When they change the circumstance, they alter the case." My expression of assent to this aphorism awoke all his vanity,--for, after pondering a moment upon it, he shook his head archly, as he added,--"People think old Scipio a fool, because he's got no sense,"--and, thereupon, the old fellow laughed till the tears came into his eyes.

In this kind of colloquy we made some twenty miles before the shades of evening overtook us, and Scipio now informed me that we might soon expect to reach Swallow Barn. The road was smooth, and canopied with dark foliage, and, as the last blush of twilight faded away, we swept rapidly round the

Page 13

head of a swamp, where a thousand frogs were celebrating their vespers, and soon after reached the gate of the court-yard. Lights were glimmering through different apertures, and several stacks of chimneys were visible above the horizon; the whole mass being magnified into the dimensions of a great castle. Some half dozen dogs bounding to the gate, brought a host of servants to receive me, as I alighted at the door.

Cousins count in Virginia, and have great privileges. Here was I in the midst of a host of them. Frank Meriwether met me as cordially as if we had spent our whole lives together, and my cousin Lucretia, his wife, came up and kissed me in the genuine country fashion:--of course, I repeated the ceremony towards all the female branches that fell in my way, and by the by, the girls are pretty enough to make the ceremony interesting, although I think they consider me somewhat oldish. As to Ned Hazard, I need not tell you he is the quintessence of good humour, and received me with that famous hearty honesty of his, which you would have predicted.

At the moment of my arrival, a part of the family were strewed over the steps of a little porch at the front door, basking in the moonlight; and before them a troop of children, white and black, trundled hoops across the court-yard, followed by a pack of companionable curs, who seemed to have a part of the game; whilst a piano within the house served as an orchestra to the players. My arrival produced a sensation that stopped all this, and I was hurried by a kind of tumultuary welcome into the parlour.

Page 14

If you have the patience to read this long epistle to the end, I would like to give you a picture of the family as it appeared to me that night; but if you are already fatigued with my gossip, as I have good reason to fear, why you may e'en skip this, and go about your more important duties. But it is not often you may meet such scenes, and as they produce some kindly impressions, I think it worth while to note this.

The parlour was one of those specimens of architecture of which there are not many survivors, and in another half century, they will, perhaps, be extinct. The walls were of panelled wood, of a greenish white, with small windows seated in deep embrasures, and the mantel was high, embellished with heavy mouldings that extended up to the cornice of the room, in a figure resembling a square fortified according to Vauban. In one corner stood a tall, triangular cupboard, and opposite to it a clock equally tall, with a healthy, saucy-faced full moon peering above the dial plate. A broad sofa ranged along the wall, and was kept in countenance by a legion of leather-bottomed chairs, which sprawled their bandy-legs to a perilous compass, like a high Dutch skater squaring the yard. A huge table occupied the middle of the room, whereon reposed a service of stately China, and a dozen covers flanking some lodgments of sweetmeats, and divers curiously wrought pyramids of butter tottering on pedestals of ice. In the midst of this array, like a lordly fortress, was placed an immense bowl of milk, surrounded by

Page 15

a circumvallation of silver goblets, reflecting their images on the polished board, as so many El Dorados in a fairy Archipelago. An uncarpeted floor glistened with a dim, but spotless lustre, in token of careful housekeeping: and around the walls were hung, in grotesque frames, some time-worn portraits, protruding their pale faces through thickets of priggish curls.

The sounding of a bell was the signal for our evening repast, and produced an instant movement in the apartment. My cousin Lucretia had already taken the seat of worship behind a steaming urn and a strutting coffee-pot of chased silver, that had the air of a cock about to crow,--it was so erect. A little rosy gentleman, the reverend Mr. Chub, (a tutor in the family,) said a hasty and half-smothered grace, and then we all arranged ourselves at the table. An aged dame in spectacles, with the mannerly silence of a dependant, placed herself in a post at the board, that enabled her to hold in check some little moppets who were perched on high chairs, with bibs under their chins, and two bare-footed boys, who had just burst into the room, overheated with play. A vacant seat remained, that, after a few moments, was occupied by a tall spinster, with a sentimental mien, who glided into the parlour with some stir. She was another cousin, Zachary, according to the Virginia rule of consanguinity, who was introduced to me as Miss Prudence Meriwether;--a sister of Frank's, and as for her age,--that's neither here nor there.

Page 16

The evening went off, as you might guess, with abundance of plain good feeling, and unaffected enjoyment. The ladies soon fell into their domestic occupations, and the parson smoked his pipe in silence at the window. The young progeny teased "uncle Ned" with importunate questions, or played at bo-peep at the parlour door, casting sly looks at me, from whence they slipt off, with a laugh, whenever they caught my eye. At last, growing tired, they rushed with one accord upon Hazard, flinging themselves across his knees, pulling his skirts, or clambering over the back of his chair, until worn out by sport, they dropped successively upon the floor, in such childish slumber, that not even their nurses woke them when they were picked up like sacks, and carried off to bed upon the shoulders.

It was not long before the rest of us followed, and I found myself luxuriating in a comfortable bed that would have accommodated a platoon. Here, listening to the tree frog and the owl, I dropped into a profound slumber, and knew nothing more of this under world, until the sun shining through my window, and the voluble note of the mocking bird, recalled me to the enjoyment of nature and the morning breeze.

And so, Zachary, you have all my adventures up to the moment of my arrival. For the future, do not expect that I mean to make you the victim of my garrulity. I admit there is something tyrannical in these special appeals to the patience of a friend, so I shall henceforth set down, in a random way, all that interests me during my present visit, and when I

Page 17

have made a book of it, my dear friend, you may read it or not, just as you like. It may be sometime before we meet, and till then be assured I wear you in my "heart of hearts."

Yours ever,

MARK LITTLETON.

Swallow Barn, June 20th, 1829.

Page 19

CHAPTER I.

SWALLOW BARN.

SWALLOW BARN is an aristocratical old edifice, that squats, like a brooding hen, on the southern bank of the James River. It is quietly seated, with its vassal out-buildings, in a kind of shady pocket or nook, formed by a sweep of the stream, on a gentle acclivity thinly sprinkled with oaks, whose magnificent branches afford habitation and defence to an antique colony of owls.

This time-honoured mansion was the residence of the family of Hazards; but in the present generation the spells of love and mortgage conspired to translate the possession to Frank Meriwether, who having married Lucretia, the eldest daughter of my late uncle, Walter Hazard, and lifted some gentlemanlike incumbrances that had been silently brooding upon the domain along with the owls, was thus inducted into the proprietory rights. The adjacency of his own estate gave a territorial feature to this alliance, of which the fruits were no less discernible in the multiplication of negroes, cattle and poultry, than in a flourishing clan of Meriwethers.

The buildings illustrate three epochs in the history

Page 20

of the family. The main structure is upwards of a century old; one story high, with thick brick walls, and a double-faced roof, resembling a ship, bottom upwards; this is perforated with small dormant windows, that have some such expression as belongs to a face without eye-brows. To this is added a more modern tenement of wood, which might have had its date about the time of the Revolution: it has shrunk a little at the joints, and left some crannies, through which the winds whisper all night long. The last member of the domicil is an upstart fabric of later times, that seems to be ill at ease in this antiquated society, and awkwardly overlooks the ancestral edifice, with the air of a grenadier recruit posted behind a testy little veteran corporal. The traditions of the house ascribe the existence of this erection to a certain family divan, where--say the chronicles--the salic law was set at nought, and some pungent matters of style were considered. It has an unfinished drawing-room, possessing an ambitious air of fashion, with a marble mantel, high ceilings, and large folding doors; but being yet unplastered, and without paint, it has somewhat of a melancholy aspect, and may be compared to an unlucky bark lifted by an extraordinary tide upon a sand-bank: it is useful as a memento to all aspiring householders against a premature zeal to make a show in the world, and the indiscretion of admitting females into cabinet councils.

These three masses compose an irregular pile, in

Page 21

which the two last described constituents are obsequiously stationed in the rear, like serving-men by the chair of a gouty old gentleman, supporting the squat and frowning little mansion which, but for the family pride, would have been long since given over to the accommodation of the guardian birds of the place.

The great hall door is an ancient piece of walnut work, that has grown too heavy for its hinges, and by its daily travel has furrowed the floor with a deep quadrant, over which it has a very uneasy journey. It is shaded by a narrow porch, with a carved pediment, upheld by massive columns of wood sadly split by the sun. A court-yard, in front of this, of a semi-circular shape, bounded by a white paling, and having a gravel road leading from a large and variously latticed gate-way around a grass plot, is embellished by a superannuated willow that stretches forth its arms, clothed with its pendant drapery, like a reverreverendend priest pronouncing a benediction. A bridle-rack stands on the outer side of the gate, and near it a ragged, horse-eaten plum tree casts its skeleton shadow upon the dust.

Some lombardy poplars, springing above a mass of shrubbery, partially screen various supernumerary buildings around the mansion. Amongst these is to be seen the gable end of a stable, with the date of its erection stiffly emblazoned in black bricks near the upper angle, in figures set in after the fashion of the work in a girl's sampler. In the same quarter a pigeon box, reared on a post, and resembling a huge tee-totum, is visible, and about its several doors and

Page 22

windows, a family of pragmatical pigeons are generally strutting, bridling and bragging at each other from sunrise until dark.

Appendant to this homestead is an extensive tract of land that stretches for some three or four miles along the river, presenting alternately abrupt promontories mantled with pine and dwarf oak, and small inlets terminating in swamps. Some sparse portions of forest vary the landscape, which, for the most part, exhibits a succession of fields clothed with a diminutive growth of Indian corn, patches of cotton or parched tobacco plants, and the occasional varieties of stubble and fallow grounds. These are surrounded with worm fences of shrunken chesnut, where lizards and ground squirrels are perpetually running races along the rails.

At a short distance from the mansion a brook glides at a snail's pace towards the river, holding its course through a wilderness of alder and laurel, and forming little islets covered with a damp moss. Across this stream is thrown a rough bridge, and not far below, an aged sycamore twists its complex roots about a spring, at the point of confluence of which and the brook, a squadron of ducks have a cruising ground, where they may be seen at any time of the day turning up their tails to the skies, like unfortunate gun boats driven by the head in a gale. Immediately on the margin, at this spot, the family linen is usually spread out by some sturdy negro women, who chant shrill ditties over their wash tubs, and keep up a spirited attack, both of tongue and hand,

Page 23

upon sundry little besmirched and bow-legged blacks, that are continually making somersets on the grass, or mischievously waddling across the clothes laid out to bleach.

Beyond the bridge, at some distance, stands a prominent object in this picture--the most time-worn and venerable appendage to the establishment:--a huge, crazy and disjointed barn, with an immense roof hanging in penthouse fashion almost to the ground, and thatched a foot thick, with sun-burnt straw, that reaches below the eaves in ragged flakes, giving it an air of drowsy decrepitude. The rude enclosure surrounding this antiquated magazine is strewed knee-deep with litter, from the midst of which arises a long rack, resembling a chevaux de frise, which is ordinarily filled with fodder. This is the customary lounge of four or five gaunt oxen, who keep up a sort of imperturbable companionship with a sickly-looking wagon that protrudes its parched tongue, and droops its rusty swingle-trees in the hot sunshine, with the air of a dispirited and forlorn invalid awaiting the attack of a tertian ague: While, beneath the sheds, the long face of a plough horse may be seen, peering through the dark window of the stable, with a spectral melancholy; his glassy eye moving silently across the gloom, and the profound stillness of his habitation now and then interrupted only by his sepulchral and hoarse cough. There are also some sociable carts under the same sheds, with their shafts against the wall, which seem to have a free and

Page 24

easy air, like a set of roysters taking their ease in a tavern porch.

Sometimes a clownish colt, with long fetlocks and dishevelled mane, and a thousand burs in his tail, stalks about this region; but as it seems to be forbidden ground to all his tribe, he is likely very soon to encounter his natural enemy in some of the young negroes, upon which event he makes a rapid retreat, not without an uncouth display of his heels in passing; and bounds off towards the brook, where he stops and looks back with a saucy defiance, and, after affecting to drink for a moment, gallops away, with a hideous whinnowing, to the fields.

Page 25

CHAPTER II.

A COUNTRY GENTLEMAN.

FRANK MERIWETHER is now in the meridian of life;--somewhere close upon forty-five. Good cheer and a good temper both tell well upon him. The first has given him a comfortable full figure, and the latter certain easy, contemplative habits, that incline him to be lazy and philosophical. He has the substantial planter look that belongs to a gentleman who lives on his estate, and is not much vexed with the crosses of life.

I think he prides himself on his personal appearance, for he has a handsome face, with a dark blue eye, and a high forehead that is scantily embellished with some silver-tipped locks, that, I observe, he cherishes for their rarity: besides, he is growing manifestly attentive to his dress, and carries himself erect, with some secret consciousness that his person is not bad. It is pleasant to see him when he has ordered his horse for a ride into the neighbourhood, or across to the Court House. On such occasions, he is apt to make his appearance in a coat of blue broadcloth, astonishingly new and glossy, and with a redundant supply of plaited ruffle strutting through the folds of a Marseilles waistcoat: a worshipful

Page 26

finish is given to this costume by a large straw hat, lined with green silk. There is a magisterial fulness in his garments that betokens condition in the world, and a heavy bunch of seals, suspended by a chain of gold, jingles as he moves, pronouncing him a man of superfluities.

It is considered rather extraordinary that he has never set up for Congress: but the truth is, he is an unambitious man, and has a great dislike to currying favour--as he calls it. And, besides, he is thoroughly convinced that there will always be men enough in Virginia willing to serve the people, and therefore does not see why he should trouble his head about it. Some years ago, however, there was really an impression that he meant to come out. By some sudden whim, he took it into his head to visit Washington during the session of Congress, and returned, after a fortnight, very seriously distempered with politics. He told curious anecdotes of certain secret intrigues which had been discovered in the affairs of the capital, gave a pretty clear insight into the views of some deep laid combinations, and became, all at once, painfully florid in his discourse, and dogmatical to a degree that made his wife stare. Fortunately, this orgasm soon subsided, and Frank relapsed into an indolent gentleman of the opposition; but it had the effect to give a much more decided cast to his studies, for he forthwith discarded the Whig, and took to the Enquirer, like a man who was not to be disturbed by doubts; and as it was morally impossible to believe what was written on both sides, to

Page 27

prevent his mind from being abused, he, from this time forward, gave an implicit assent to all the facts that set against Mr. Adams. The consequence of this straight forward and confiding deportment was an unsolicited and complimentary notice of him by the executive of the state. He was put into the commission of the peace, and having thus become a public man against his will, his opinions were observed to undergo some essential changes. He now thinks that a good citizen ought neither to solicit nor decline office; that the magistracy of Virginia is the sturdiest pillar that supports the fabric of the constitution; and that the people, "though in their opinions they may be mistaken, in their sentiments they are never wrong,"--with some other such dogmas, that, a few years ago, he did not hold in very good repute. In this temper, he has of late embarked upon the mill-pond of county affairs, and, notwithstanding his amiable and respectful republicanism, I am told he keeps the peace as if he commanded a garrison, and administers justice like a cadi.

He has some claim to supremacy in this last department; for during three years of his life he smoked segars in a lawyer's office at Richmond; sometimes looked into Blackstone and the Revised Code; was a member of a debating society that ate oysters once a week during the winter; and wore six cravats and a pair of yellow-topped boots as a blood of the metropolis. Having in this way qualified himself for the pursuits of agriculture, he came to his estate a very model of landed gentlemen. Since that time

Page 28

his avocations have had a certain literary tincture; for having settled himself down as a married man, and got rid of his superfluous foppery, he rambled with wonderful assiduity through a wilderness of romances, poems and dissertations, which are now collected in his library, and, with their battered blue covers, present a lively type of an army of continentals at the close of the war, or a hospital of veteran invalids. These have all, at last, given way to the newspapers--a miscellaneous study very enticing to gentlemen in the country--that have rendered Meriwether a most discomfiting antagonist in the way of dates and names.

He has great sauvity of manners, and a genuine benevolence of disposition, that makes him fond of having his friends about him; and it is particularly gratifying to him to pick up any genteel stranger within the purlieus of Swallow Barn, and put him to the proof of a week's hospitality, if it be only for the pleasure of exercising his rhetoric upon him. He is a kind master, and considerate towards his dependants, for which reason, although he owns many slaves, they hold him in profound reverence, and are very happy under his dominion. All these circumstances make Swallow Barn a very agreeable place, and it is accordingly frequented by an extensive range of his acquaintances.

There is one quality in Frank that stands above the rest. He is a thorough-bred Virginian, and consequently does not travel much from home, except to make an excursion to Richmond, which he considers

Page 29

emphatically as the centre of civilization. Now and then, he has gone beyond the mountain, but the upper country is not much to his taste, and in his estimation only to be resorted to when the fever makes it imprudent to remain upon the tide. He thinks lightly of the mercantile interest, and in fact undervalues the manners of the cities generally;--he believes that their inhabitants are all hollow hearted and insincere, and altogether wanting in that substantial intelligence and honesty that he affirms to be characteristic of the country. He is a great admirer of the genius of Virginia, and is frequent in his commendation of a toast in which the state is compared to the mother of the Gracchi:--indeed, it is a familiar thing with him to speak of the aristocracy of talent as only inferior to that of the landed interest,--the idea of a freeholder inferring to his mind a certain constitutional pre-eminence in all the virtues of citizenship, as a matter of course.

The solitary elevation of a country gentleman, well to do in the world, begets some magnificent notions. He becomes as infallible as the Pope; gradually acquires a habit of making long speeches; is apt to be impatient of contradiction, and is always very touchy on the point of honour. There is nothing more conclusive than a rich man's logic any where, but in the country, amongst his dependants, it flows with the smooth and unresisted course of a gentle stream irrigating a verdant meadow, and depositing its mud in fertilizing luxuriance. Meriwether's sayings, about Swallow Barn, import absolute

Page 30

verity--but I have discovered that they are not so current out of his jurisdiction. Indeed, every now and then, we have some obstinate discussions when any of the neighbouring potentates, who stand in the same sphere with Frank, come to the house; for these worthies have opinions of their own, and nothing can be more dogged than the conflict between them. They sometimes fire away at each other with a most amiable and unconvinceable hardihood for a whole evening, bandying interjections, and making bows, and saying shrewd things with all the courtesy imaginable: but for unextinguishable pertinacity in argument, and utter impregnability of belief, there is no disputant like your country gentleman who reads the newspapers. When one of these discussions fairly gets under weigh, it never comes to an anchor again of its own accord--it is either blown out so far to sea as to be given up for lost, or puts into port in distress for want of documents,--or is upset by a call for the boot-jack and slippers--which is something like the previous question in Congress.

If my worthy cousin be somewhat over-argumentative as a politician, he restores the equilibrium of his character by a considerate coolness in religious matters. He piques himself upon being a high-churchman, but he is only a rare frequenter of places of worship, and very seldom permits himself to get into a dispute upon points of faith. If Mr. Chub, the Presbyterian tutor in the family, ever succeeds in drawing him into this field, as he occasionally has the address to do, Meriwether is sure to fly the

Page 31

course:--he gets puzzled with scripture names, and makes some odd mistakes between Peter and Paul, and then generally turns the parson over to his wife, who, he says, has an astonishing memory.

Meriwether is a great breeder of blooded horses; and, ever since the celebrated race between Eclipse and Henry, he has taken to this occupation with a renewed zeal, as a matter affecting the reputation of the state. It is delightful to hear him expatiate upon the value, importance, and patriotic bearing of this employment, and to listen to all his technical lore touching the mystery of horse-craft. He has some fine colts in training, that are committed to the care of a pragmatical old negro, named Carey, who, in his reverence for the occupation, is the perfect shadow of his master. He and Frank hold grave and momentous consultations upon the affairs of the stable, in such a sagacious strain of equal debate, that it would puzzle a spectator to tell which was the leading member in the council. Carey thinks he knows a great deal more upon the subject than his master, and their frequent intercourse has begot a familiarity in the old negro that is almost fatal to Meriwether's supremacy. The old man feels himself authorized to maintain his positions according to the freest parliamentary form, and sometimes with a violence of asseveration that compels his master to abandon his ground, purely out of faint-heartedness. Meriwether gets a little nettled by Carey's doggedness, but generally turns it off in a laugh. I was in the stable with him, a few mornings after my arrival, when he

Page 32

ventured to expostulate with the venerable groom upon a professional point, but the controversy terminated in its customary way. "Who sot you up, Master Frank, to tell me how to fodder that 'ere cretur, when I as good as nursed you on my knee?" "Well, tie up your tongue, you old mastiff," replied Frank, as he walked out of the stable, "and cease growling, since you will have it your own way;"--and then, as we left the old man's presence, he added, with an affectionate chuckle--"a faithful old cur, too, that licks my hand out of pure honesty; he has not many years left, and it does no harm to humour him!"

Page 33

CHAPTER III.

FAMILY PORTRAITS.

WHILST Frank Meriwether amuses himself with his quiddities, and floats through life upon the current of his humour, his dame, my excellent cousin Lucretia, takes charge of the household affairs, as one who has a reputation to stake upon her administration. She has made it a perfect science, and great is her fame in the dispensation thereof!

They who have visited Swallow Barn will long remember the morning stir, of which the murmurs arose even unto the chambers, and fell upon the ears of the sleepers;--the dry-rubbing of floors, and even the waxing of the same until they were like ice;-- and the grinding of coffee mills;--and the gibber of ducks, and chickens, and turkeys; and all the multitudinous concert of homely sounds. And then, her breakfasts! I do not wish to be counted extravagant, but a small regiment might march in upon her without disappointment; and I would put them for excellence and variety against any thing that ever was served upon platter. Moreover, all things go like clock-work. She rises with the lark, and infuses an early vigour into the whole household. And yet she

Page 34

is a thin woman to look upon, and a feeble; with a sallow complexion, and a pair of animated black eyes that impart a portion of fire to a countenance otherwise demure from the paths worn across it, in the frequent travel of a low country ague. But, although her life has been somewhat saddened by such visitations, my cousin is too spirited a woman to give up to them; for she is therapeutical in her constitution, and considers herself a full match for any reasonable tertian in the world. Indeed, I have sometimes thought that she took more pride in her leech-craft than becomes a Christian woman: she is even a little vain-glorious. For, to say nothing of her skill in compounding simples, she has occasionally brought down upon her head the sober remonstrances of her husband, by her pertinacious faith in the efficacy of certain spells in cases of intermittent. But there is no reasoning against her experience. She can enumerate the cases--"and men may say what they choose about its being contrary to reason, and all that:--it is their way! But seeing is believing--nine scoops of water in the hollow of the hand, from the sycamore spring, for three mornings, before sunrise, and a cup of strong coffee with lemon juice, will break an ague, try it when you will." In short, as Frank says, "Lucretia will die in that creed."

I am occasionally up early enough to be witness to her morning regimen, which, to my mind, is rather tyrannically enforced against the youngsters of her numerous family, both white and black. She is in the habit of preparing some death-routing decoction

Page 35

for them, in a small pitcher, and administering it to the whole squadron in succession, who severally swallow the dose with a most ineffectual effort at repudiation, and gallop off, with faces all rue and wormwood.

Every thing at Swallow Barn, that falls within the superintendence of my cousin Lucretia, is a pattern of industry. In fact, I consider her the very priestess of the American system, for, with her, the protection of manufactures is even more of a passion than a principle. Every here and there, over the estate, may be seen rising in humble guise above the shrubbery, the rude chimney of a log cabin, where all the livelong day the plaintive moaning of the spinning-wheel rises fitfully upon the breeze, like the fancied notes of a hobgoblin, as they are sometimes imitated in the stories with which we frighten children. In these laboratories the negro women are employed in preparing yarn for the loom, from which is produced not only a comfortable supply of winter clothing for the working people, but some excellent carpets for the house.

It is refreshing to behold how affectionately vain our good hostess is of Frank, and what deference she shows to his judgment in all matters, except those that belong to the home department;--for there she is, confessedly and without appeal, the paramount power. It seems to be a dogma with her, that he is the very "first man in Virginia," an expression that in this region has grown into an emphatic provincialism. Frank, in return, is a devout admirer of

Page 36

her accomplishments, and although he does not pretend to an ear for music, he is in raptures at her skill on the harpsichord, when she plays at night for the children to dance; and he sometimes sets her to singing 'The Twins of Latona,' and 'Old Towler,' and 'The Rose Tree in Full Bearing' (she does not study the modern music), for the entertainment of his company. On these occasions he stands by the instrument, and nods his head, as if he comprehended the airs.

She is a fruitful vessel, and seldom fails in her annual tribute to the honours of the family; and, sooth to say, Frank is reputed to be somewhat restiff under these multiplying blessings. They have two lovely girls, just verging towards womanhood, who attract a supreme regard in the household, and to whom Frank is perfectly devoted. Next to these is a boy,--a shrewd, mischievous imp, that curvets about the house, 'a chartered libertine.' He is a little wiry fellow near thirteen, that is known altogether by the nick-name of Rip, and has a scapegrace countenance, full of freckles and deviltry: the eyes are somewhat greenish, and the mouth opens alarmingly wide upon a tumultuous array of discoloured teeth. His whole air is that of an untrimmed colt, torn down and disorderly; and I most usually find him with the bosom of his shirt bagged out, so as to form a great pocket, where he carries apples or green walnuts, and sometimes pebbles, with which he is famous for pelting the fowls.

I must digress, to say a word about Rip's headgear

Page 37

He wears a non-descript skull-cap, which, I conjecture from some equivocal signs, had once been a fur hat, but which must have taken a degree in fifty other callings; for I see it daily employed in the most foreign services. Sometimes it is a drinking-vessel, and then Rip pinches it up like a cocked hat; sometimes it is devoted to push-pin, and then it is cuffed cruelly on both sides; and sometimes it is turned into a basket, to carry eggs from the hen-roosts. It finds hard service at hat-ball, where, like a plastic statesman, it is popular for its pliability. It is tossed in the air on all occasions of rejoicing; and now and then serves for a gauntlet--and is flung with energy upon the ground, on the eve of a battle: And it is kicked occasionally through the school yard, after the fashion of a bladder. It wears a singular exterior, having a row of holes cut below the crown, or rather the apex, (for it is pyramidal in shape,) to make it cool, as Rip explains it, in hot weather. The only rest that it enjoys through the day, as far as I have been able to perceive, is during school hours, and then it is thrust between a desk and a bulk-head, three inches apart, where it generally envelopes in its folds a handful of hickory-nuts or marbles. This covering falls down--for it has no lining--like an extinguisher over Rip's head, which is uncommonly small and round, and garnished with a tangled mop of hair. To prevent the frequent recurrence of this accident, Rip has pursed it up with a hat-band of twine.

Page 38

From Rip the rest of the progeny descend on the scale, in regular gradations, like the keys of a Pandean pipe, and with the same variety of intonations, until the series is terminated in a chubby, dough-faced infant, not above three months old.

This little infantry is under the care of mistress Barbara Winkle, an antique retainer of the family, who attends them at bed and board,--and every morning takes the whole bevy, one by one, and plunges them into a large tub of cold water; after which, they are laid out on the floor to dry, like young frogs on the margin of a pool; and then she dresses and combs them with a scrupulous rigour, they making, all the while, terribly wry faces. The faithful dame, as she turns them on her knee, sings some approved lullabies in a querulous tone of voice, accompanied by a soothing recitative, which, I have occasionally observed, is apt to be chanted in rather an angry and shrill key.

This mistress Barbara is a functionary of high rank in the family, and of great privileges, from having exercised her office through a preceding generation at Swallow Barn. She is particularly important when there are any festive preparations on foot; and there is then evidently an enhancement of her official gravity. She glides up and down stairs with surprising alacrity, amidst an exceeding din of keys; and may be found one moment whipping cream, and another, whipping some unlucky scullion boy; clattering eggs in a bowl, scolding servants, and screaming

Page 39

at Rip, who is perpetually in her way, amongst the sweetmeats: All of which matters, though enacted with a vinegar aspect, it is easy to see are very agreeable to her self-love.

She is truly what may be termed a bustling old lady, and has a most despotic rule over all the subordinates of the family. There is no reverence like that of children for potentates of this description. Her very glance has in it something disconcerting to the young fry; and they will twist their dumpling faces into every conceivable expression of grief, before they will dare to squall out in her presence. Even Rip is afraid of her. "When the old woman's mad, she is a horse to whip!" he told Ned and myself one morning, upon our questioning him as to the particulars of an uproar in which he had been the principal actor. These exercises on the part of the old lady are neither rare nor unwholesome, and are winked at by the higher authorities.

Mrs. Winkle's complexion is the true parchment, and her voice is somewhat cracked. She takes Scotch snuff from a silver box, and wears a pair of horn spectacles, which give effect to the peculiar peakedness of her nose. On days of state she appears in all the rich coxcombry of the olden time; her gown being of an obsolete fashion, sprinkled with roses and sun-flowers, and her lizard arms encased in tight sleeves as far as the elbow, where they are met by silken gloves without fingers. A starched tucker is pinned,

Page 40

with a pedantic precision, across her breast; and a prim cap of muslin, puckered into a point with a grotesque conceit, adorns her head.--Take her altogether, she looks very stately and bitter. Then, when she walks, it is inconceivable how aristocratically she rustles,--especially on a Sunday.

Page 41

CHAPTER IV.

FAMILY PARAGONS.

MY picture of the family would be incomplete if I did not give a conspicuous place to my two young cousins Lucy and Victorine. It is true, they are cousins only in the second remove, but I have become sufficiently naturalized to this soil to perceive the full value of the relation; and as they acknowledge it very affectionately to me--for I was promoted to "cousin Mark" almost in the first hour after my arrival,--I should be unreasonably reluctant not to assert the full right of blood. Lucy tells me she is only fifteen, and is careful to add that she is one year and one month older than Vic, "for all that Vic is taller than she." Now Lucy is a little fairy in shape, with blue eyes and light hair, and partially freckled and sunburnt,--being a very pretty likeness of Rip, who I have said is an imp of homeliness,--a fact which all experience shows is quite consistent with the highest beauty. Victorine is almost a head taller, and possesses a stronger frame. She differs, too, from her sister by her jet black eyes and dark hair;--though they resemble each other in the wholesome tan which exposure to the atmosphere has spread alike over the cheeks of both.

Page 42

These two girls have been educated at home, and have grown up together with an almost inseparable instinct. Their parents, according to the common notions of such indulgences, have done every thing to spoil them, but, as yet, completely without effect. I cannot, however, help thinking, that it is a popular errour to believe that freedom is not fully compatible with the finest nurture of the affections. A kindly nature will most generally expand in the direction of the charities, and its currents will flow in a channel of virtue unless solicited out of their track by evil enticements. Though the vigilance which is necessary to separate the young mind from what is likely to deceive it, does necessarily contract the theatre upon which the propensities of the pupil are allowed to range, it is not in any degree restrictive of her freedom whilst she is ignorant that there is any thing forbidden. The opportunity which is afforded by a country life of maintaining this unconscious restraint, constitutes its principal preference over the city, in the education of a young female. There is nothing more lovely to my imagination than the picture of an artless girl, tranquilly gliding onwards to womanhood in the seclusion of the parent bower; invigorated in the affections by the ceaseless caresses of her nearest kindred, and her taste receiving its daily hue from the fresh and exquisite colours of nature, as she sees them in the grove and fountain and varying skies, remote from the tawdry artifices of a compact and crowded society: Her first lessons of love imbued from the lips of a mother; her only lore taught her

Page 43

at that fire-side which has been from infancy her citadel of happiness; her emotions allowed to pursue their unchecked wanderings through all her world, bounded, as she believes it to be, by the objects with which she has always been familiar; and her rambles limited to "her ancient neighbourhood," like the flights of a dove in its native valley.

Lucy and Victorine present a beautiful archetype of this picture. Meriwether has the tenderest fondness for them; and my cousin Lucretia has cherished in them that kind of intimacy with their parents that has more of the intercourse of equals than the subordination of children. Towards each other these two girls manifest a gentleness that is the perfection of harmony;

-- Where e'er they went, like Juno's swans,

Still they went coupled and inseparable.

Their tempers, nevertheless, are somewhat in contrast. Lucy is rather meditative for her age,--calm and almost matronly. Thought seems to repose like sleep upon her countenance, except when it is warmed by the lively play of feelings that flicker across it, like breezes upon the surface of a lake. She is attached to books, and, following the instinct of her peculiar temperament, her mind has early wandered through the mysterious marvels of fiction, which have impressed a certain trace of superstition upon her infant character. Victorine is more intrepid than her elder sister, and attracts a universal regard, by that buoyant jollity of disposition which, in a young girl, is the index both of innocence and affection.

Page 44

They both, however, pursue the same studies;--and I often see them sitting together at their common tasks, poring upon the same book, with their arms around each other's waists. Almost every evening--and often without any others of the family--they walk out for exercise along the by-paths upon the river bank. In these excursions they are attended by two large white pointers, that gambol around them in all manner of fantastic play, soliciting the applause of their pretty mistresses by the gallant assiduities that belong to the race of these noble animals.

Meriwether is accustomed to have the girls read to him some portion of every day, and by this requisition, which he puts upon the ground of a personal favour, has beguiled them into graver studies than are generally appropriated to the sex. It is delightful to observe what an unwearying devotion they bestow upon a labour which they think gives pleasure to the father. He, of course, looks upon them as the most gifted creatures in existence; and, truly, I am almost a convert to his opinion!

A window in the upper story of one of the wings of the building, overlooks a flower garden; and around this window grows a profusion of creeping vine, which is trained to diffuse itself with an architectural precision along the wall towards the roof; and it is evident that the disciplined plant dares not throw out a leaf or a tendril awry. It is a prim, pedantic, virgin plant, with icy leaves of perdurable green without a flower to give variety to its trimmed

Page 45

complexion, except where here and there the parasite rose has surreptitiously stolen in amongst its plexures, and peeps forth from beneath its sober tapestry. In this window, about noon-tide, may be daily seen, just visible from within the chamber, the profuse tresses of a head of sandy hair, scrupulously adjusted in glossy volume; and ever and anon, as it moves to some slow impulse, is disclosed a studious brow of fairest white. And sometimes, more fully revealed, may be seen the entire head of a 'lady bright,' as she seems intent upon a book. The lady Prudence sits in her bower, and thoughtfully pursues some theme of romance in the delicious realm of poesy,--or, with pencil and brush, shapes and gilds the gaudy wings of her painted butterflies, or, peradventure, enricheth her album with dainty sonnets. And sometimes, in listless musing, she rests her chin upon her gem-bedizened hand, and fixes her soft blue eye upon the flower beds, where the humming bird is poised before the honeysuckle, or the finical wren prates lovingly to his dame. But, howsoever engaged, it is a dedicated hour, and 'the ladie' is in her secret bower. I have said profanely, once before, that 'a tall spinster' sat at the family board--and now, here she sits in her morning guise, silent and alone, pondering over uncreated things, and turning up her imaginative eye to the cerulean deeps.

Prudence is the only sister of Frank Meriwether, and, like most only sisters, holds a sort of consecrated

Page 46

place amongst the household idols. But time, which notches his eras upon mortal forms, with as little mercy as if they were mere sticks, has calendared the stages of his journey in some delicate touches, even upon this goodly page, and has published the fact, that Prudence Meriwether has now arrived at that isthmus of life, in which her pretensions to count with old or young are equally doubtful. It is settled, however, she has reached all the discretion she will ever possess. What boots it that she is arrayed in an urgent vivacity of manner, and an air of thoughtless joy? Is it not manifestly overdone? and are there not, as plain as the veteran of the scythe could draw them, certain sober lines, creeping from the mouth cheek-ward, that betoken sedate rumination? and will not every astute, good-humoured bachelor see that she has come to that mellow time, when a woman is especially captivating to him, because she is more complaisant, and bears her virtues more meekly? For myself, I speak experimentally in behalf of the brotherhood, and declare it is even so.

The lady in question has undoubtedly thought very gravely over the important concerns that belong to her estate, and is fast coming to the conclusion, that her destiny hereafter is likely to be exercised in the cares of a single and unlorded dowry. She has given several indications of this. I find that of late she talks peremptorily of her decided preference for the maiden state, and has taken up some newfangled notions of the unworthiness of the male sex. She

Page 47

hints, now and then, at some cast-off flirtations of hers, in which she had the credit, a few years ago, of disconcerting some spruce gallants of the country. But all this I consider a mere feint, like that of a politic commander, who, having made a disastrous campaign, puts his reputation in repair by the fame of his early conquests.

There are other fearful prognostics of this temper dawning upon her manners. She has grown inveterately charitable, and addicts herself to matters that, but a short time ago, were clean out of sight. Her views have gradually become more comprehensive; and her pursuits have something of the diffusiveness of a public functionary. For example, she is known to be the principal founder of three Sunday Schools in the neighbourhood; is supposed to have pensioned out several poor families; besides being a stirring advocate of the scheme for colonizing the negroes, and a patroness of sundry Tract Societies;--to say nothing of even a supererogatory zeal for the suppression of intemperance in the lower sections of Virginia. These acts cause her to be regarded as a very model of piety; and I have heard it whispered, that the flattery she has received from divers young ministers on this score, has actually set her to writing a book in imitation of mistress Hannah More,--which, however, I set down for pure scandal.

One thing is certain,--Prudence is more romantic than she used to be;--for about sun-set, she often wanders forth alone, to a sequestered part of the

Page 48

grove, and stalks with a stately and philosophic pace amongst the old oaks, unbonneted, in a rapturous contemplation of the radiant tints of evening; and then, in her boudoir may be found exquisite sketches from her pencil, of forms of love and beauty--gallant knights, and old castles, and pensive ladies,--madonnas and cloistered nuns,--the teeming offspring of an imagination heated with romance and devotion. Her attire is sometimes plain, and even negligent, to a studied degree;--but this does not last long; for Prudence, in spite of her discipline, does not underrate her personal advantages, and it is not unusual for her to break out almost into a riotous vivacity, especially when she is brought into communion with a flaunting, mad-cap belle, that is carrying all before her:--She then, like 'a pelting river,' overbears 'her continents,' and, in the matter of dress and manners, becomes almost as flaunting a mad-cap as the other.

Her person is very good, although I think it unnecessarily erect; and a hypercritical observer might say her air was rather formal; but that would depend very much upon the time when he saw her;--for if it should happen to be just before dinner, in the drawing-room, he would be ready to acknowledge that she only wanted a pastoral crook, to make an Arcadian of her.

If Prudence has a fault, it is in setting down the domestic virtues at too high a value;--by which virtues I mean those undisturbed humours that quiet

Page 49

life inspires, and which are mistaken for personal properties,--the sleep of the passions, and not the subjugation of them, which the good people of the country are fond of praising, as much as if it were a matter they could help. This point of character is manifested by our lady in a habitual exaggeration of the benefits of solitude and self constraint, and has rendered her, to an undue degree, merciless towards the pretensions of those whose misfortune it is to live in a busier sphere than herself. To my mind, she is too rigid in her requisitions upon society. This, however, is a very slight blemish, and amply compensated by the many pleasant variations in her composition. She talks with great ease upon every subject; and is even, now and then, a little too high-flown in her diction. Her manner, at times, might be called oratorical, more particularly when she bewails the departure of the golden age, or declaims upon the prospect of its revival amongst the rejuvenescent glories of the Old Dominion. She has awful ideas of personal decorum and the splendour of her lineage, but these are almost the only points upon which I know her to be touchy. Apart from such defects, which appear upon her character like fleecy clouds upon a summer sky, or mites upon a snow-drift, she is a captivating specimen of a ripened lady just standing on that sunshiny verge from which the prospect below presents a sedate, autumnal landscape, gently subsiding into a distant, undistinguishable and misty confusion of tree and field, arrayed in sober brown. It is no wonder, therefore, that with

Page 50

her varied perfections and the advantages of her position, the world--by which I mean that scattered population which inhabits the banks of the James River, extending inland some ten miles on either side--should, by degrees, and almost insensibly, have propagated the opinion that Prudence Meriwether is a prodigy.

Page 51

CHAPTER V.

NEW HAZARD.

NED HAZARD has of late become my inseparable companion. He has a fine, flowing stream of good spirits, which is sometimes interrupted by a slight under-current of sadness; it is even a ludicrous pensiveness, that derives its comic quality from Ned's constitutional merriment.